Abstract

Background:

Patients with spinal cord injury (SCI) have an increased risk for multidrug-resistant organisms, including carbapenem-resistant Enterobacteriaceae (CRE). Accurate and easily applied definitions are critical to identify CRE. This study describes CRE and associated characteristics in Veterans with SCI per Centers for Disease Control (CDC) and Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) definitions.

Methods:

Retrospective cohort of Veterans with SCI and ≥1 culture with Escherichia coli, Klebsiella, and/or Enterobacter between 2012-2013. Antibiotic susceptibility criteria of pre-2015 (CDC1) and post-2015 (CDC2) CDC definitions and pre-2017 (VA1) and post-2017 (VA2) VA definitions were used to identify CRE. CRE prevalence and facility characteristics are described for isolates meeting each definition, and agreement among definitions was assessed with Cohen’s kappa.

Results:

21,514 isolates cultured from 6,974 Veterans were reviewed; 423 isolates met any CRE definition. Although agreement among definitions was high (κrange=0.82-0.93), definitions including ertapenem resistance led to higher CRE prevalence (VA1=1.7% and CDC2=1.9% vs. VA2=1.4% and CDC1=1.5%). 44/142 VA facilities had ≥1 CRE defined by VA2; 10 facilities accounted for 60% of CRE. Almost all CRE was isolated from high complexity, urban facilities; the South had the greatest proportion of CRE isolates.

Conclusions:

Varying federal definitions give different CRE frequencies among a high-risk population. Definitions including ertapenem resistance resulted in greater CRE prevalence, but may overemphasize less significant non-carbapenemase producing isolates. Thus, both federal definitions now highlight the importance of carbapenemase testing.

Keywords: carbapenem-resistant Enterobacteriaceae, multidrug resistance, spinal cord injury, surveillance

Introduction

The prevalence of infections caused by multidrug-resistant organisms (MDROs) has been steadily increasing in both healthcare and community settings.1 Carbapenem-resistant Enterobacteriaceae (CRE) are among the most difficult to treat MDROs and have been designated by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) at the highest level antibiotic resistance threat due to steadily increasing rates of colonization and infections in healthcare settings every year.2 In 2012, 3.9% of short stay hospitals and 17.8% of long term acute hospitals (LTAC) hospitals reported at least one CRE healthcare-associated infection (HAI), which was significantly higher than in previous years.3 In addition, CRE infections are associated with high morbidity and mortality, longer hospital length of stay, and increased healthcare costs.4,5

Both the Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) and the CDC have established guidelines for CRE surveillance and infection prevention practices within healthcare facilities.6,7 Different CRE definitions have been proposed by CDC and VA, with both organizations having updated their CRE definitions with the publication of their most recent guidelines. Accurate and easily applied definitions are critical to identify MDROs, to conduct local facility and national surveillance, to allocate infection prevention resources, and to implement infection prevention strategies most effectively in the highest risk patient populations.

Patients with spinal cord injury (SCI) represent one such high risk population and have an increased prevalence of many MDROs, including CRE.8–10 This increased prevalence is due to use of indwelling medical devices, high rates of antibiotic use, and frequent hospitalizations, all of which are associated with MDRO colonization and infection.9,11–15 Within VA, patients with SCI are often cared for in specialty care settings, such as specialized SCI units and long-term care facilities (LCTFs). Care in such settings has also been associated with an increased risk for CRE.16 In a high-risk population such as those with SCI, understanding the impact of varying definitions for MDROs can contribute valuable information for targeted surveillance and infection prevention. In this study, we applied the four different federal definitions of CRE to a large population of Veterans with SCI from inpatient, outpatient, and long-term care settings to determine CRE prevalence. We also assessed whether differences in federal definitions impact CRE estimates and identified patient characteristics associated with the various CRE definitions.

Methods

Study setting and design

This was a retrospective cohort study of all adult patients with existing SCI treated at any VA medical center (VAMC) between January 1, 2012 and December 31, 2013. VAMCs are classified into three major complexity levels determined in part by volume, patient characteristics, and research and teaching activities (Levels 1a-c, 2, and 3; with Level 1a being highest). We defined high complexity facilities as Levels 1a-c and low complexity facilities as Levels 2 and 3. VA also uses the Rural-Urban Commuting Areas (RUCA) system to classify VAMCs into urban vs. rural.17 Urban VAMCs are located in census tracts with at least 30% of the population residing in an urbanized area as defined by the U.S. Census Bureau. Rural VAMCs are located in areas not defined as urban. Veterans with multiple sclerosis, amyotrophic lateral sclerosis, and Guillain-Barre syndrome were excluded because the VA SCI system of care focuses on individuals with stable non-progressive spinal cord neurological deficits. The institutional review board at the Edward Hines, Jr. VA Hospital approved this study.

Clinical and microbiology data collection

All bacterial cultures performed for patients with SCI during the study period that grew Escherichia coli, Klebsiella species or Enterobacter species were included. Although other species of Enterobacteriaceae can be carbapenem-resistant, we chose to focus on these species because they are most commonly associated with carbapenem resistance and are the focus of the current VA definition. Cultures could be obtained from any site and performed in any healthcare setting (inpatient, outpatient, rehabilitation, long-term care). Multiple cultures from the same patient within 30 days were removed. National VA clinical and microbiology datasets were used to collect data on patient demographics, modified Charlson comorbidity index, level and extent of SCI, healthcare utilization, microbiologic data, and medication exposures. U.S. Census Bureau categories were used to define geographic regions.

Definitions

CRE was defined using the antibiotic susceptibility criteria of both old and new VA and CDC definitions (Table 1). The first VA definition (VA1) was established in December, 2014 with publication of the 2015 Guideline for Control of Carbapenem-Resistant Enterobacteriaceae (CRE).7 The VA1 definition focused on E. coli, Klebsiella spp., and Enterobacter spp., and included recommendations for confirmation of carbapenemase production using the Modified Hodge Test (MHT). The second VA definition (VA2) was established in February, 2017 when an updated guideline was published: VHA 2017 Guideline for Control of Carbapenemase Producing-Carbapenem Resistant Enterobacteriaceae (CP-CRE).18 Antibiotic susceptibility criteria for VA2 were simplified (Table 1).The VA2 definition focused on E. coli, Klebsiella pneumoniae/oxytoca, Enterobacter cloacae, and other Enterobacter spp., and recommended PCR-based tests to identify carbapenemase production.

Table 1.

Summary of CRE definitions.

| Definition | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| VA1 | VA2 | CDC1 | CDC2 | |

| Organisms |

Escherichia coli Klebsiella spp. Enterobacter spp. |

Escherichia coli K. pneumoniae/oxytoca Enterobacter spp. (especially E. cloacae) |

All Enterobacteriaceae |

All Enterobacteriaceae |

| Carbapenem criteria | Intermediate (“I”) or resistant (“R”) to imipenem, meropenem, and/or doripenem OR Resistant (“R”) to ertapenem AND (see next row) |

Resistant (“R”) to imipenem, meropenem, and/or doripenem | Intermediate (“I”) or resistant (“R”) to imipenem, meropenem, and/or doripenem AND (see next row) |

Resistant (“R”) to any carbapenem |

| Cephalosporin criteria | Resistant (“R”) to any tested 3rd-generation cephalosporin | None | Resistant (“R”) to all the following 3rd-gen cephalosporins that were tested: ceftriaxone, cefotaxime, ceftazidime | None |

| Additional criteria a | Positive Modified Hodge Test | Positive molecular diagnostic test (PCR) | Documented that organism produces a carbapenemase | |

These criteria were not assessed as part of this study

CRE, carbapenem-resistant Enterobacteriaceae; PCR, polymerase chain reaction

The first CDC definition (CDC1) was established in 2012 with publication of the Facility Guidance for Control of Carbapenem-resistant Enterobacteriaceae (CRE): 2012 CRE Toolkit.19 The second CDC definition (CDC2) was established in November 2015 with publication of the 2015 update to the CDC CRE Toolkit.6 Similar to the VA definition, antibiotic susceptibility criteria for CDC2 were simplified (Table 1). CDC2 also emphasizes carbapenemase testing using MHT, Carba NP, PCR, and/or metallo-β-lactamase screens. Neither CDC definition focuses on specific genera or species; rather they include all Enterobacteriaceae.

Statistical analysis:

Each CRE definition (VA1, VA2, CDC1, CDC2) was applied to the cohort to determine how differences among the definitions contributed to differing CRE prevalence in patients with SCI. Agreement among the definitions was assessed using Kappa coefficients. Descriptive statistics were used to summarize patient demographics, clinical and SCI characteristics, and prior healthcare and antibiotic exposures. Bivariate statistics with unadjusted logistic regression were used to compare geographic trends of isolates meeting just the less restrictive definition and isolates meeting both definitions combined. Bonferroni correction for multiple comparisons was applied, with p < 0.025 considered significant. Statistical analyses were carried out using SAS, version 9.4 (SAS Institute) and Stata, version 12.1 (Stata Corp LP).

Results

Figure 1 displays the development of our CRE cohort, starting with data from 19,657 Veterans with SCI and at least one medical encounter at a VAMC during the study period. Overall, 2.6% (179) of patients with cultures positive for target Enterobacteriaceae had CRE by any definition; these patients contributed 423 CRE isolates (Figure 1). Basic demographics and clinical characteristics of the patients with CRE are displayed in Table 2. Consistent with the VA population, most patients were older and male, and most had paraplegia with incomplete SCI. Most patients were receiving care in an acute inpatient setting at the time of positive CRE culture.

Figure 1.

Study cohort with numbers of patients with CRE and CRE isolates included.

Table 2.

Demographics and clinical characteristics of CRE patients in the cohort.

| Definitions | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| VA1 (n=149) | VA2 (n=127) | All VA (n=164) | CDC1 (n=116) | CDC2 (n=174) | All CDC (n=178) | |

| Age, years, mean (SD) | 66.1 (13.2) | 65.5 (13.4) | 65.5 (13.4) | 66.9 (13.0) | 65.5 (13.6) | 65.3 (13.7) |

| Female | 3 (2.0%) | 2 (1.6%) | 4 (2.2%) | 2 (1.7%) | 3 (1.7%) | 4 (2.2%) |

| SCI characteristicsa | ||||||

| Level of injury: | ||||||

| Paraplegia | 75 (50.3%) | 62 (48.8%) | 90 (50.3%) | 57 (49.1%) | 87 (50.0%) | 92 (50.0%) |

| Tetraplegia | 64 (43.0%) | 58 (45.7%) | 77 (43.0%) | 54 (46.6%) | 73 (42.0%) | 78 (42.4%) |

| Extent of injury: | ||||||

| Incomplete | 69 (46.3%) | 62 (48.8%) | 82 (45.8%) | 56 (48.3%) | 82 (47.1%) | 87 (47.3%) |

| Complete | 51 (34.2%) | 39 (30.7%) | 62 (34.6%) | 37 (31.9%) | 58 (33.3%) | 62 (33.7%) |

| Onset of injury: | ||||||

| Non-traumatic | 52 (34.9%) | 36 (28.3%) | 60 (33.5%) | 38 (32.8%) | 57 (32.8%) | 62 (33.7%) |

| Traumatic | 74 (49.7%) | 69 (54.3%) | 91 (50.8%) | 59 (50.9%) | 88 (50.6%) | 93 (50.5%) |

| Duration of injury, years, median (range) | 8 (0 – 62) | 8 (0 – 62) | 8 (0 – 62) | 7 (0 – 62) | 8 (0 – 62) | 8 (0 – 62) |

| Charlson comorbidity index score, median (range) | 2 (0 – 12) | 2 (0 – 10) | 2 (0 – 12) | 2 (0 – 10) | 2 (0 – 12) | 2 (0 – 12) |

| Patient culture location: | ||||||

| Inpatient | 83 (55.7%) | 67 (52.8%) | 98 (54.7%) | 63 (54.3%) | 93 (53.4%) | 96 (52.2%) |

| LTCF | 52 (34.9%) | 47 (37.0%) | 66 (36.9%) | 42 (36.2%) | 65 (37.4%) | 72 (39.1%) |

| Outpatient | 13 (8.7%) | 12 (9.4%) | 14 (7.8%) | 11 (9.5%) | 15 (8.6%) | 15 (8.2%) |

| U.S. Census Region | ||||||

| Northeast | 25 (16.8%) | 27 (21.3%) | 30 (16.8%) | 24 (20.7%) | 34 (19.5%) | 37 (20.1%) |

| Midwest | 23 (15.4%) | 23 (18.1%) | 32 (17.9%) | 19 (16.4%) | 29 (16.7%) | 29 (15.8%) |

| South | 43 (28.9%) | 36 (28.3%) | 51 (28.5%) | 32 (27.6%) | 50 (28.7%) | 53 (28.8%) |

| West | 29 (19.5%) | 15 (11.8%) | 33 (18.4%) | 16 (13.8%) | 31 (17.8%) | 34 (18.5%) |

| Other | 29 (19.5%) | 26 (20.5%) | 33 (18.4%) | 25 (21.6%) | 30 (17.2%) | 31 (16.8%) |

All data expressed as number (%) unless otherwise indicated

SD, standard deviation; SCI, spinal cord injury; CRE, carbapenem-resistant Enterobacteriaceae; LTCF, long-term care facility

Some data missing for this variable

Table 3 shows CRE frequency by isolate and unique patient, bacterial species, and culture sources grouped by CRE definition. Most isolates were obtained from urine, and Klebsiella spp. were isolated most frequently. CRE prevalence by unique patient and isolate was higher with the VA1 definition compared to the VA2 definition; however, the reverse was true for the CDC definitions (Table 3). Agreement between the various definitions was high, with Kappa coefficients all above 0.8. The less restrictive definitions (VA1 and CDC2; κ = 0.91, 95% CI 0.89-0.93) and more restrictive definitions (VA2 and CDC1; κ = 0.93, 95% CI 0.91-0.95) exhibited the highest level of agreement. Among 37 patients with isolates meeting the VA1 definition but not the VA2 definition, the majority met VA1 criteria due to ertapenem resistance in the absence of resistance to other carbapenems (n=32, 86.5%). Likewise, among 62 patients with isolates meeting the CDC2 definition but not the CDC1 definition, the majority met the CDC2 criteria due to isolated ertapenem resistance (n=45, 72.6%).

Table 3.

Characteristics of CRE isolates grouped by CRE definition.

| Definition | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| VA1 | VA2 | CDC1 | CDC2 | |

| No. of CRE isolatesa | 369 (1.7%) | 308 (1.4%) | 316 (1.5%) | 404 (1.9%) |

| No. of unique patientsb | 149 (2.1%) | 127 (1.8%) | 116 (1.7%) | 174 (2.5%) |

| Organism isolated | ||||

| E. coli | 17 (11.4%) | 16 (12.6%) | 8 (6.9%) | 23 (13.2%) |

| Klebsiella spp. | 93 (62.4%) | 88 (69.3%) | 85 (73.3%) | 105 (60.3%) |

| Enterobacter spp. | 39 (26.2%) | 23 (18.1%) | 23 (19.8%) | 46 (26.4%) |

| Culture source | ||||

| Urine | 99 (66.4%) | 87 (68.5%) | 81 (69.8%) | 119 (68.4%) |

| Blood | 11 (7.4%) | 8 (6.3%) | 9 (7.8%) | 12 (6.9%) |

| Sputum | 20 (13.4%) | 14 (11.0%) | 12 (10.3%) | 21 (12.1%) |

| Otherc | 19 (12.8%) | 18 (14.2%) | 14 (12.1%) | 22 (12.6%) |

| No. of CRE isolates by facility complexity and location | ||||

| 1a-1c (High) | 363 (98.4%) | 297 (96.4%) | 309 (97.8%) | 392 (97.0%) |

| 2-3 (Low) | 6 (1.6%) | 11 (3.6%) | 7 (2.2%) | 12 (3.0%) |

| Urban | 368 (99.7%) | 305 (99.0%) | 314 (99.4%) | 401 (99.3%) |

| Rural | 1 (0.3%) | 3 (1.0%) | 2 (0.6%) | 3 (0.7%) |

CRE, carbapenem-resistant Enterobacteriaceae

Out of 21,514 total E. coli, Klebsiella spp., and Enterobacter spp. isolates

Out of 6,974 unique patients with at least one E. coli, Klebsiella spp., and/or Enterobacter spp. isolate

Wound, tissue, and fluid

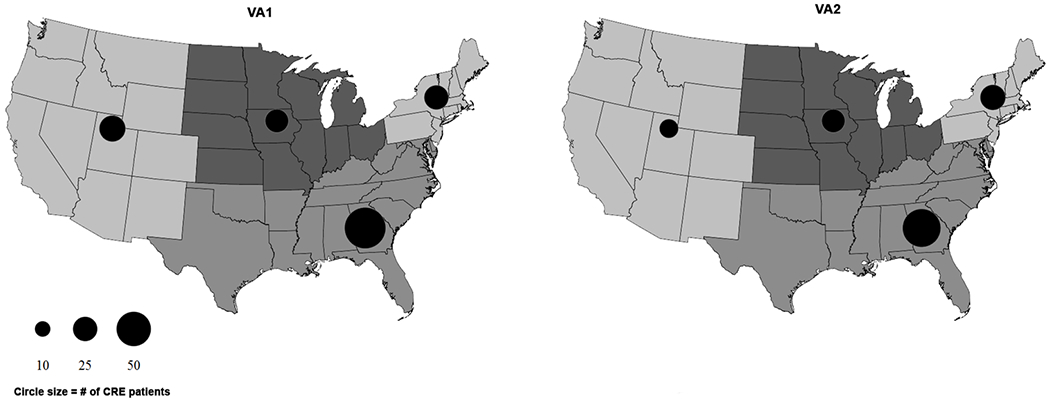

Interesting trends were observed in the geographic distribution of patients with CRE in this study. The 6,974 patients with cultures that grew target Enterobacteriaceae were cared for at 142 different VA medical centers, with 44 (31%) of these medical centers having at least one patient with CRE. The vast majority of CRE isolates were identified in high complexity, urban VAMCs (Table 1). Figure 2 shows the geographic distribution of patients with CRE meeting the old (VA1) and new (VA2) VA definitions. Overall, the South, which included Puerto Rico, had the greatest number of CRE patients (Figure 2). Although most patients with CRE were seen at VA facilities associated with SCI centers (n=91, 81.3% by VA2 definition), there were 23 VA facilities without an SCI center that had at least one patient with CRE. On bivariate analysis, increased odds of meeting only the less restrictive VA definition (VA1) were observed in patients with CRE from the West [odds ratio (OR) 34.0, 95% confidence interval (CI) 4.03-286.83, p<0.01] and South (OR 9.29, 95%CI 1.13-76.51, p=0.016). A similar geographic association was not observed with the CDC definition, although there was a trend toward significance for the West region (OR 2.91, 95% CI 1.05-8.1, p=0.039).

Figure 2.

Geographic distribution of CRE isolates based on VA1 (prior) and VA2 (current) definitions. Circle size corresponds to number of patients with CRE, as indicated in the legend, with smaller circles indicating fewer patients and larger circles indicating more patients. The varying shades of gray represent states in each of the U.S. Census Bureau regions (West, Midwest, Northeast, and South). Puerto Rico was analyzed with the South region.

Discussion

Accurate identification of CRE using validated, standardized laboratory techniques and definitions is a critical first step in preventing spread. Development of a standard definition has been influenced by multiple factors, including the epidemiologic and clinical importance of distinguishing CP-CRE from non-CP-CRE, the availability of laboratory testing, and the complexity of definition implementation. As CRE has increased in prevalence over the past decade, many definitions have been developed, which have included varying bacterial species, antibiotic susceptibility results, and carbapenemase testing. Multiple groups have now focused on simplifying these various definitions to identify CRE in a way that is both accurate and easily implemented for all healthcare facilities. For example, initial CRE definitions developed by both the CDC and VA included 3rd generation cephalosporin susceptibility testing, but proved cumbersome to implement as surveillance definitions and missed some CP-CRE.7,19 They were then simplified with updated definitions that focused solely on carbapenem susceptibility testing with adjunctive laboratory testing for carbapenemase production, if available. Variability in surveillance definitions for MDROs may profoundly impact prevalence and associated risk factors, but this has not been well-described for CRE.

In this study, we compared CRE prevalence associated with surveillance definitions from the VA and CDC among Veterans with SCI, a cohort of patients at elevated risk for MDROs such as CRE.8–10,14,15 We found that CRE prevalence was higher with the earlier VA definition (VA1), mostly due to isolated ertapenem resistance in the absence of resistance to other carbapenems. The exclusion of ertapenem from the updated 2017 VA definition (VA2) simplifies the definition was intended to place greater emphasis on isolates producing carbapenemases. In contrast, the earlier CDC definition (CDC1) did not include resistance to ertapenem, but the later CDC definition (CDC2) does include this. As a result, we found greater CRE prevalence with CDC2 compared to CDC1. Regardless of CRE definition, frequencies were high in this patient population, particularly compared to general population-based CRE incidence rates recently described by the CDC.11 Another important difference between VA and CDC definitions is the focus by VA on specific species within the Enterobacteriaceae family. Focusing on E. coli, Klebsiella spp., and Enterobacter spp. allows a targeted approach to identifying organisms that are most often associated with carbapenem resistance mediated by carbapenemases. Furthermore, this focused approach minimizes confusion related to species with intrinsic imipenem resistance (i.e., Morganella, Proteus, and Providencia). However, such a focused approach must be weighed against the risk of failing to identify CRE within these other species.

Most patients with CRE (~60%) were seen at 10 of the 44 VA facilities who had at least one patient with CRE. Almost all of the VAMCs with CRE were Level 1 and located in urban areas. Such facilities care for more complex and more critically ill patients, who are at higher risk for CRE; they are also more likely to have dedicated SCI centers and, therefore, more likely to care for patients in our cohort. Our prior work has shown increased risk for other MDROs in patients seen at VA facilities with SCI centers, although this association is not maintained after adjustment for confounders such as age, comorbidity, and antibiotic and healthcare exposures.9,15 However, 23 facilities without SCI centers also cared for at least one patient with CRE during our study period, suggesting that CRE may impact VA facilities of varying complexity level, geographic location, and size. Variability in CRE definitions has important implications for effective MDRO identification and surveillance at such facilities. Interestingly, patients with SCI seen at VA facilities in the West and South regions had greater odds of meeting only the less restrictive VA1 definition compared to both VA1 and VA2 definitions combined. The reasons behind this association may relate to local epidemiologic trends in these regions and/or greater presence of non-CP-CRE, which may be more likely to demonstrate isolated ertapenem resistance.

This study had several important limitations. First, we did not distinguish between patients who were infected versus colonized. Differentiation between CRE infection and colonization would be important for a study examining clinical outcomes, but is less critical when assessing the impact of surveillance definitions on CRE prevalence and epidemiologic associations. Second, although we examined data during years which had no major modifications to the Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute breakpoints for our organisms, the identification and reporting of bacterial susceptibilities in individual VA microbiology labs may have changed during our study period. We also did not include information on carbapenemase testing, and relied only on antibiotic susceptibility criteria for the definitions. Given that many microbiology laboratories are not able to routinely identify carbpenemases, the results of our study may be more broadly applicable. Finally, we were not able to include microbiology cultures collected outside the VA.

In conclusion, accurate and timely identification, reporting, and surveillance for CRE is critical to controlling its spread. In our study, applying different federal CRE surveillance definitions lead to variability in CRE prevalence among a cohort of Veterans at elevated risk for MDRO infection and colonization, with isolated resistance to ertapenem contributing to much of the variability. Updated VA and CDC definitions now focus on more simplified antibiotic susceptibility criteria and emphasize the importance of testing for carbapenemase production to confirm CRE diagnosis.

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by funding from the Veterans Health Administration, Office of Research and Development, Rehabilitation Research and Development Service SPIRE Award (B-1583-P), Health Services Research and Development Service Presidential Early Career Award for Scientists and Engineers (USA 12-564) and Post-doctoral Fellowship Award (TPR 42-005). The views expressed in this article are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the position or policy of the Department of Veterans Affairs or the U.S. government. All authors report no conflicts of interest relevant to this article.

Footnotes

This work was presented in part as a poster at the SHEA 2016 Spring Conference.

References

- 1.Weiner LM, Webb AK, Limbago B, et al. Antimicrobial-resistant pathogens associated with healthcare-associated infections: summary of data reported to the National Healthcare Safety Network at the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 2011-2014. Infect. Control Hosp. Epidemiol. 2016;37:1288–1301. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). Antibiotic resistance threats in the United States. April 2013. http://www.cdc.gov/drugresistance/threat-report-2013/index.html. Accessed 1 February 2016.

- 3.Centers for Disease Control, Prevention. Vital signs: carbapenem-resistant Enterobacteriaceae. MMWR Morb. Mortal. Wkly. Rep. 2013;62:165–170. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Xu L, Sun X, Ma X Systematic review and meta-analysis of mortality of patients infected with carbapenem-resistant Klebsiella pneumoniae. Ann. Clin. Microbiol. Antimicrob. 2017;16:18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ny P, Nieberg P, Wong-Beringer A Impact of carbapenem resistance on epidemiology and outcomes of nonbacteremic Klebsiella pneumoniae infections. Am. J. Infect. Control 2015;43:1076–1080. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). Facility Guidance for Control of Carbapenem-resistant Enterobacteriaceae (CRE): November 2015 Update -- CRE Toolkit. 2015. https://www.cdc.gov/hai/pdfs/cre/CRE-guidance-508.pdf. Accessed Nov 1, 2017.

- 7.2015 Guideline for Control of Carbapenem-Resistant Enterobacteriaceae (CRE). Washington, DC: National Infectious Disease Service MDRO Prevention Office, Veterans Health Administration, Department of Veterans Affairs; 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Suda KJ, Patel UC, Sabzwari R, et al. Bacterial susceptibility patterns in patients with spinal cord injury and disorder (SCI/D): an opportunity for customized stewardship tools. Spinal Cord 2016;54:1001–1009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Evans CT, Fitzpatrick MA, Jones MM, et al. Prevalence and factors associated with multidrug-resistant gram- negative organisms in patients with spinal cord injury. Infect. Control Hosp. Epidemiol. 2017;38:1464–1471. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Fitzpatrick MA, Suda KJ, Safdar N, et al. Changes in bacterial epidemiology and antibiotic resistance among veterans with spinal cord injury/disorder over the past 9 years. J. Spinal Cord Med. 2018;41:199–207. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Guh AY, Bulens SN, Mu Y, et al. Epidemiology of Carbapenem-Resistant Enterobacteriaceae in 7 US Communities, 2012-2013. JAMA 2015;314:1479–1487. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.van Loon K, Voor In ‘t Holt AF, Vos MC Clinical epidemiology of carbapenem-resistant Enterobacteriaceae: a systematic review and meta-analyses. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Fitzpatrick MA, Suda KJ, Safdar N, et al. Unique risks and clinical outcomes associated With extended-spectrum beta-lactamase Enterobacteriaceae in Veterans with spinal cord injury or disorder: a case-case-control study. Infect. Control Hosp. Epidemiol. 2016;37:768–776. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kale IO, Fitzpatrick MA, Suda KJ, et al. Risk factors for community-associated multidrug-resistant Pseudomonas aeruginosa in veterans with spinal cord injury and disorder: a retrospective cohort study. Spinal Cord 2017;55:687–691. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ramanathan S, Suda KJ, Fitzpatrick MA, et al. Multidrug-resistant Acinetobacter: Risk factors and outcomes in veterans with spinal cord injuries and disorders. Am. J. Infect. Control 2017;45:1183–1189. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lin MY, Lyles-Banks RD, Lolans K, et al. The importance of long-term acute care hospitals in the regional epidemiology of Klebsiella pneumoniae carbapenemase-producing Enterobacteriaceae. Clin. Infect. Dis. 2013;57:1246–1252. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Department of Veterans Affairs. Office of Rural Health. 2018. www.ruralhealth.va.gov/aboutus/ruralvets.asp. Accessed July 10, 2018.

- 18.2017 Guideline for Control of Carbapenemase-producing Carbapenem-resistant Enterobacteriaceae (CP-CRE). Washington, DC: National Infectious Disease Service MDRO Prevention Office, Veterans Health Administration, Department of Veterans Affairs; 2017. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). Guidance for Control of Carbapenem-resistant Enterobacteriaceae (CRE): 2012 CRE Toolkit. 2012. https://stacks.cdc.gov/view/cdc/13205. Accessed Jan 1, 2017.