Abstract

Background

Sexually Transmitted Infections, including Neisseria gonorrhoeae (NG) and Chlamydia trachomatis (CT), continue to be a global health problem. Increased access to point-of-care-tests (POCTs) could help detect infection and lead to appropriate management of cases and contacts, reducing transmission and development of reproductive health sequelae. Yet diagnostics with good clinical effectiveness evidence can fail to be implemented into routine care. Here we assess values beyond clinical effectiveness for molecular CT/NG POCTs implemented across diverse routine practice settings.

Methods

We conducted a systematic review of peer-reviewed primary research and conference abstract publications in Medline and Embase reporting on molecular CT/NG POCT implementation in routine clinical practice until 16th February 2021. Results were extracted into EndNote software and initially screened by title and abstract by one author according to the inclusion and exclusion criteria. Articles that met the criteria, or were unclear, were included for full-text assessment by all authors. Results were synthesised to assess the tests against guidance criteria and develop a CT/NG POCT value proposition for multiple stakeholders and settings.

Findings

The systematic review search returned 440 articles; 28 were included overall. The Cepheid CT/NG GeneXpert was the only molecular CT/NG POCT implemented and evaluated in routine practice. It did not fulfil all test guidance criteria, however, studies of test implementation showed multiple values for test use across various healthcare settings and locations. Our value proposition highlights that the majority of values are setting-specific. Sexual health services and outreach services have the least overlap, with General Practice and other non-sexual health specialist services serving as a “bridge” between the two.

Conclusions

Those wishing to improve CT/NG diagnosis should be supported to identify the values most relevant to their settings and context, and prioritise implementation of tests that are most closely aligned with those values.

Introduction

It is estimated that there are over 1 million new curable sexually transmitted infections (STI) cases every day; in 2016 there were approximately 376 million new cases of the most common curable STIs: Neisseria gonorrhoeae (NG), Chlamydia trachomatis (CT) Trichomonas vaginalis (TV), and syphilis [1]. If left untreated, these infections can result in serious reproductive health sequelae, such as infertility, chronic pelvic pain, ectopic pregnancy, and pelvic inflammatory disease. CT and NG infections are two key STIs: CT is the most commonly reported STI [2], and treatment of NG is a global public health problem following the emergence of multi-drug resistant strains [3].

Syndromic management (diagnosis and treatment of STIs based on patients’ clinical history and reported and observed symptoms) has been shown to be both poorly sensitive and specific for STI diagnosis [4]. It can result in asymptomatic but infected individuals not being treated, resulting in continued transmission and development of reproductive health sequelae. Conversely, symptomatic patients of unknown aetiology may receive unnecessary, inappropriate and/or sub-optimal treatment, potentially increasing the risk of STI antimicrobial resistance (AMR) emergence [5]. STI diagnosis is therefore ideally informed by diagnostic tests, and there has been a marked move away from syndromic management, wherever possible, in the majority of high-income settings [6]. However, in LMICs, syndromic management is still commonplace. There is little access to large-scale laboratories, as well as a lack of highly skilled healthcare professionals and specialised equipment in clinical settings, which are needed for aetiological diagnosis of STIs [4, 5].

Diagnostics have been hailed as a critical intervention to reduce the global burden of AMR [3], with a growing need for the development of point-of-care tests (POCTs) to combat the global STI health burden [6, 7]. The World Health Organization (WHO) defines POCTs as those that can be used at, or near, the point of patient care [8]. Guidelines and criteria for optimal diagnostics have been published to both guide test development and assess their ability to meet STI control requirements in all settings [9–12]. These include the REASSURED criteria (Affordable, Sensitive, Specific, User‐friendly, Rapid and robust, Equipment‐free and Deliverable to end‐users, recently updated to also include advances in m-health, incorporating both “Real-time connectivity” and “Ease of specimen collection”) [9, 11]. These criteria focus on the needs of LMICs and were developed by WHO’s STD Diagnostics Initiative as a benchmark to determine whether POCTs for community level (level 1 health centres) use meet local requirements for STI prevention, control and management [13]. Furthermore, POCT Target Product Profiles (TPPs) for specific infections have been created by WHO through consultation with experts. These TPPs focus both on LMIC and higher-income country needs, and include multiple minimal and optimal characteristics, from diagnostic accuracy characteristics to cost [12]. TPPs aim to help accelerate and guide future STI POCT development [12].

There are various POCTs for CT and NG diagnosis available [8, 14, 15]. Non-molecular testing for NG includes Gram stain microscopy, which requires specialist equipment and a high-level of training of healthcare professionals within the clinic [16]. For CT, commercial antigen detection lateral flow tests have been developed with the ASSURED criteria in mind: they are low-cost, equipment-free and easy to perform, but offer suboptimal sensitivity for diagnosis [12, 17]. International guidelines stipulate that diagnosis of CT and NG should be based on results from highly-accurate molecular tests wherever possible [18–21]. To date, two highly accurate molecular POCTs for CT and NG have obtained Conformité Européene (CE) marking from the European Union, and United States Food and Drug Association (FDA) regulatory approval, both of which offer CT/NG dual detection: the Cepheid GeneXpert, with a 90-minute time-to-results [22], and the binx health io with a 30-minute time-to-results [23].

However, even diagnostics with excellent clinical trial outcomes face multiple barriers to adoption [24, 25]. Although TPP and REASSURED criteria are useful frameworks for test development and evaluation, different values for adoption, such as clinical, process and financial outcomes, are negotiated during implementation [26]. It is increasingly recognised that the social and structural context of implementing a new technology is as important as evidence for its clinical effectiveness [27–29], and that these should be reviewed from the different perspectives of multiple stakeholders [24, 30, 31]. Stakeholders are defined as any person or organisation contributing to a care pathway, including patients, carers, healthcare professionals, provider organisations, purchasers of healthcare services, policymakers and laboratory medicine specialists [32].

The value of POCTs is likely to differ both within and between different stakeholder groups, who often have varying priorities and objectives [33]. It is important to understand these values to facilitate the integration of POCTs into sexual healthcare. There are many proposed frameworks to measure value [34], one of which is the value proposition of laboratory medicine [35]. It aims to facilitate the implementation of innovations in healthcare by consolidating and making visible the available evidence of the innovations’ costs and benefits to different stakeholders [35]. It also considers values beyond clinical trial data, arguing that in an outcomes-based health system, the value of an innovation to all stakeholders must be measured and communicated [32, 35, 36].

We aimed to develop a value proposition for molecular CT/NG POCTs that is reflective of the needs of different sexual healthcare stakeholders, in order to facilitate decision-making processes for implementation and adoption of CT/NG POCTs into diverse care settings.

Methods

The overall research question was: “What are the outcomes of molecular CT/NG POCTs implementation for patients being tested for CT/NG in different routine practice settings?” To answer this question, we developed three specific objectives: i.) What values are placed on CT/NG POCTs implemented in routine practice in the published literature? ii.) Do molecular CT/NG POCTs implemented in routine practice fulfil the (RE)ASSURED and TPP criteria? iii.) What is the value proposition for molecular CT/NG POCTs by setting, based on the value proposition for laboratory medicine [35]?

To meet our first objective, we conducted a systematic review of the published literature reporting on molecular CT/NG POCT implementation in routine clinical care. To meet the second objective, we reviewed and assessed compliance of the tests identified through the systematic review to REASSURED and TTP criteria for STI POCT development, using data from formal diagnostic evaluations. For the third objective, we developed a CT/NG POCT value proposition based on a synthesis of the wider available evidence. Data from additional studies evaluating NAAT-based test(s) for CT/NG, but that were ineligible for the systematic review (e.g. research-only outcome, such as diagnostic accuracy studies; or not primary research, such as cost-effectiveness modelling), were extracted. These were applied to the value proposition for laboratory medicine framework [35] to develop a value proposition for molecular CT/NG POCTs, by setting type. Data were tabulated to meet each objective, and a narrative synthesis of results (i.e., rather than a metanalysis) was conducted by SSF and EMHE, given the heterogeneity of study designs and settings.

The systematic review was conducted in MEDLINE and Embase (OvidSP interfaces) to include all peer-reviewed primary research and conference abstract publications until 16th February 2021 (S1 and S2 Tables). Both MEDLINE and Embase (OvidSP interfaces) were searched by one researcher (EC) for studies involving human participants using a combination of terms and synonyms based on four key concepts (chlamydia AND gonorrhoea AND point of care tests AND evaluation). For full details of search terms please see S1 Table. We report our review following the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) guidelines [37] (S2 Table).

Results were extracted into EndNote (Clarivate Analytics, Philadelphia, USA), and duplicates removed. Titles and abstracts were screened by EC according to the inclusion and exclusion criteria (Table 1). Articles that met the criteria, or any that were unclear, were included for full text review by all authors independently, with any discrepancies discussed as a group to reach consensus for final inclusion. SSF and EMHE independently extracted data from eligible articles into custom-made Excel (v2019, Microsoft) tables. References of included papers were also hand-searched by EC and new potentially eligible articles full-text screened by all authors before confirming inclusion, with data independently extracted by SSF and EMHE.

Table 1. Inclusion and exclusion criteria.

| Inclusion | Exclusion | |

|---|---|---|

| Population |

|

|

| Intervention |

|

|

| Outcome |

|

|

| Type of study |

|

|

| Date |

|

|

| Language |

|

|

Study quality was assessed by SSF and EMHE, independently, using the Critical Appraisal tools for use in JBI Systematic Reviews where possible ([38] as recommended by [39]; S3–S7 Tables). For studies where the CT/NG POCT was implemented as routine (e.g. service evaluations), we modified the JBI checklist for analytical cross-sectional studies by removing the three questions relating to exposure and confounding, as no JBI checklists were appropriate. For before-after studies, the NHLBI quality assessment tool was used [40]. For questionnaire-based studies, the Center for Evidence-Based Management “Critical appraisal of a survey” checklist was used ([41] as recommended by [42]). Any differences between the two reviewers were reconciled through discussion to provide an overall study quality score calculated as number of questions with a “yes” response divided by the total number of questions. Any questions that were non-applicable were removed from the denominator.

We did not produce a protocol or register this study.

Results

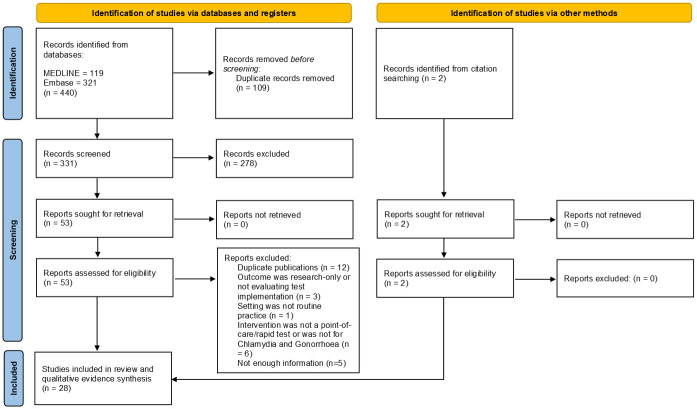

The systematic review search returned 440 articles, of which 26 were included for review. After the references of the 26 included articles were checked to confirm completeness, two further articles were eligible, which led to a final inclusion of 28 articles (Fig 1). Study quality assessment indicated that 5 studies were of low quality (≤50% criteria met), 4 studies were of medium quality (between 50 and 75% of criteria met) and the remaining 19 articles were of high quality (≥75% criteria met) (S3–S9 Tables).

Fig 1. PRISMA flowchart [37].

From: Page MJ, McKenzie JE, Bossuyt PM, Boutron I, Hoffmann TC, Mulrow CD, et al. The PRISMA 2020 statement: an updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. BMJ 2021;372:n71. doi: 10.1136/bmj.n71. For more information, visit: http://www.prisma-statement.org/.

The binx health io CT/NG has been implemented in a small number of clinical settings, however, available reports show the test being implemented in research-use only scenarios in the USA [43, 44] and publications (to-date of this review) reporting implementation in the UK do not report clinical and other health-related outcomes [45]. The Cepheid CT/NG GeneXpert has been implemented and evaluated for multiple outcomes measures in many settings around the world. As such, only the Cepheid GeneXpert platform, using the CT/NG dual diagnostic cartridge, was eligible for assessing compliance with international guidelines for CT/NG POCT development and evaluation, and evaluating the values placed on CT/NG POCTs implemented in routine practice in the published literature.

TPP and REASSURED criteria provide checklists to guide the development and evaluation of STI POCTs. A summary of both these frameworks for CT/NG POCTs is presented below (Table 2); these reflect a summary of published evaluations of the Cepheid CT/NG GeneXpert diagnostic performance.

Table 2. The Cepheid CT/NG GeneXpert fulfilment of TPPs and REASSURED criteria.

| Characteristic* | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Sensitivity/specificity genital samples (a,b) | Sample type | CT % sensitivity / specificity | NG % sensitivity / specificity |

| Male Urine | 97.5 / 99.9 | 98.0 / 99.9 | |

| Female endocervical swab | 97.4 / 99.6 | 100.0 / 100 | |

| Female vaginal swab | 98.7 / 99.4 | 100.0 / 99.9 | |

| Female Urine | 97.6 / 99.8 | 95.6 / 99.9 | |

| Pooled percent agreement extra-genital samples (a,b) | Sample type | CT % agreement positive / negative | NG % agreement positive / negative |

| Rectal | 89.72% / 99.23% | 92.75% / 99.75% | |

| Pharyngeal | 89.96% / 99.62% | 92.51% / 98.56% | |

| Use setting (a,b) | Table-top, not portable | ||

| Level 2 service (district hospital) | |||

| Specimen (a,b) | Female and male urine, endocervical swab, vaginal swab, rectal swab and pharyngeal swab from asymptomatic and symptomatic patients | ||

| Steps; user-friendly (a,b) | ~4; sample preparation automated. Three-step process from sample provision to processing; sealed cartridge system; <1 minute hands-on time | ||

| Time to result (run-time) (a,b) | ~90 mins | ||

| Cold chain; reagent stability (a,b) | No; to be determined | ||

| Power (a,b) | Mains power or solar power | ||

| Training; user-friendly (a,b) | Less than half a day | ||

| Connectivity for monitoring, surveillance & data export (a,b) | Yes; computer/internet required; remote calibration; C360 platform system provides systems and epidemiology monitoring. Connectivity between GeneXpert and electronic patient records used to deliver results in published service evaluation [47]. | ||

| Equipment price (USD); per test price (a,b) | ~17,000 USD (with 4 modules), but could be higher; 16.20 USD (CT/NG) | ||

| Environmentally friendly (a,b) | No: single use cartridge; disposal of used materials via local medical waste regulations | ||

| Environmental tolerance of packaged test kit and operating conditions (robust—tolerance to difficult environmental conditions) (a,b) | Stable temperature and power required but has been used successfully in remote healthcare settings (see Table 3) | ||

| Internal quality control (a) | Yes. Sample Adequacy Control on each cartridge for increased results integrity | ||

| Sample capacity/through-put (a) | Various capacity readers available (single to 80 cartridge units); readers stackable for scale-up | ||

TPP recommendations for CT/NG POCTs

WHO TPP recommendations for CT/NG POCTs include: sensitivity (NG: 90% minimal, 98% optimal; CT: 90% minimal, 100% optimal) and specificity (NG and CT: 98% minimal, 100% optimal); training requirements (<90 minutes minimal, <30 minutes optimal); time-to-results (<60 minutes minimal, <30 minutes optimal) and price per test (<5 USD minimal, <1 USD optimal) [12]. Other considerations include the inclusion of a Global Positioning System (GPS) on the platform reader, and sample capacity/through-put [12]. Operational use prioritisation is suggested to be in the following order: ease of use, training, high tolerance to difficult environmental conditions and long shelf life, self-contained quality control, data capture/connectivity/data export, biosafety and waste disposal [12].

REASSURED criteria

The REASSURED criteria are: Real-time connectivity (feedback for patient treatment and connection to surveillance systems); Ease of specimen collection and Environmentally-friendly (non-invasive specimen collection; use of recyclable materials and reduction of hazardous waste); Affordable (<10.00 USD for a molecular assay); Sensitive (minimising false negatives) and Specific (minimising false positives); User-friendly (2–3 steps and minimal training required); Rapid and robust (15–60 minutes from sample-in to answer-out; withstands various weather and environmental conditions without refrigeration); Equipment-free (or utilises batteries or solar power) and Deliverable to end-users (ensures it reaches LMIC users) [11].

Published diagnostic evaluations show that the Cepheid CT/NG GeneXpert fulfils some, but not all, TPP and REASSURED criteria (Table 2). Minimal sensitivity and specificity requirements are met for genital samples, but not for extra-genital samples for CT. Training may be considered too long at “less than half a day”, compared with the minimal TPP requirement for <90 minutes. The 90-minute time-to-results is longer than the 60-minute minimum of both criteria frameworks, and the cost is higher than the 10 USD recommendation for the REASSURED criteria. In addition, the test is not environmentally friendly, as it uses a single-use cartridge to be disposed of via local medical waste regulations. However, the test can be used with non-invasive specimen types, does feature connectivity for monitoring, surveillance and data export, and is user-friendly with automated sample preparation and a three-step process from sample provision to processing. It also features a sample adequacy control for internal quality control purposes. The REASSURED criteria “deliverable to end-users” can be considered contextually, such as the tests’ compatibility with diagnostics currently in use (e.g. current use of the GeneXpert platform for tuberculosis or TV testing [46]), which relate to potentials to use pre-existing procurement and test supply chains in those settings.

Data from eligible articles were extracted to show the value of implementing the Cepheid CT/NG GeneXpert in three different healthcare service settings (specialist sexual health services, General Practice [GP] and other non-sexual health specialist services, and outreach services), spanning different income settings (Table 3).

Table 3. Routine implementation of the Cepheid CT/NG GeneXpert in different healthcare service settings.

| Care setting | Study design and location | Target population | Test Implementation | Impacts assessed | Results |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sexual health services | GeneXpert test implementation and time to treatment comparison with same target population. San Francisco City STI Clinic, USA. May-Dec 2018. Cohen et al. 2019. | Asymptomatic MSM and transwomen attending follow-up care for HIV PrEP; those who were sexual contacts of someone with CT/NG were excluded | GeneXpert implementation as standard of care among MSM and transwomen |

|

|

| Comparison of standard care with “sample-first” (prior to consultation) pathway and use of in-house GeneXpert testing on patient management. Courtyard Clinic, St George’s University Hospitals NHS Foundation Trust, London UK. Harding-Esch et al. 2017. | Males and females symptomatic for CT/NG infection; sexual contacts of CT/NG positive patients | Standard triage procedure followed by self-collected sample provided by patients prior to clinical consultation. GeneXpert testing, routine culture and microscopy, and non-NAAT POCTs for TV and BV. Results provided to patients in clinical consultation |

|

|

|

| Implementation of GeneXpert in specialist sexual health clinic symptomatic service in London, UK. No dates given. Mandlik et al. 2017. | Subset of 100 symptomatic patients diagnosed with CT/NG | GeneXpert implementation as standard of care |

|

|

|

| Retrospective review of patients’ notes in sexual health clinic after GeneXpert introduction, London, UK. No dates given. Whitlock et al. 2015. | Patients diagnosed with CT/NG | Service redesign involving express screening service, including sexual history on touchscreen computers, self-collected samples, POC testing and automated results management |

|

|

|

| Comparison of data between Dean Street Express (DSE; a walk-in, rapid STI screening service for asymptomatic individuals) and 56 Dean Street (56DS; standard off-site laboratory-based NAAT testing), London, UK, in one-year period from 1 June 2014 to 31 May 2015. Whitlock et al. 2018. | Patients attending DSE and 56DS. Data extracted from patient notes of first 12 patients (MSW, MSM and women) | GeneXpert implementation as standard of care at DSE. Sexual history is provided by patients on a touchscreen computer, which orders the relevant swabs based on self-reported sexual history. Patients self-collect swabs/samples, which are delivered to and processed on-site GeneXpert. Health adviser reviews sexual history, collects blood for off-site syphilis, HIV and/or hepatitis B/C testing (results within 4 hours). Treatment for test-positive patients is provided at 56DS |

|

|

|

| Comparison of standard care and use of in-house GeneXpert testing and results notification pathway. Dean Street Express clinic, Chelsea and Westminster Hospital NHS Foundation Trust, London UK. 19 April 2013–7 January 2014. Wingrove et al. 2014. | Males and females asymptomatic for CT/NG infection | GeneXpert introduced into clinic for on-site testing |

|

|

|

| General Practice and other non-sexual health specialist services | Assessment of introducing newly available STI POCTs and treatment. Alotau, Milne Bay Province, Papua New Guinea. August—December 2014. Badman et al. 2016 | Females ≥18 years attending their first clinic antenatal visit | Face to face interview with nurse: demographic and sexual behaviour data collection. Routine antenatal and provider-initiated HIV (Alere Determine HIV1/2) and syphilis (SD Bioline anti TP 3.0) screening via rapid test; Syphilis rapid test followed by confirmatory laboratory test. Self-collected vaginal swabs with on-site testing for CT/NG and TV (Cepheid GeneXpert) and BV (BV Blue). Positive patients (as needed): same-day antibiotic treatment; risk-reduction counselling; contact tracing |

|

|

| Assessment of introducing GeneXpert into two university hospital family planning clinics: Antoine Béclère Hospital (Clamart, France) and Avicenne Hospital (Bobigny, France), July 2012—Jan 2013. Bourgeois-Nicolaos et al. 2015. | Women presenting to the clinics for induced abortion, intrauterine device insertion as emergency contraception, or signs of STI, were consecutively recruited | Patient samples sent for GeneXpert testing in hospital’s laboratory. Test results reported to clinic by phone and/or fax. Patients with positive results were immediately telephoned and prescription faxed to their closest pharmacy. Prescriptions for partners, or letter to partner’s physician, provided |

|

|

|

| Assessment of GeneXpert implementation in Haitian Study Group for Kaposi’s sarcoma and Opportunistic Infections (GHESKIO) clinics. GHESKIO provides “integrated primary care services, including HIV counselling, AIDS care, antenatal care, and management of tuberculosis and STIs.” Port-au-Prince, Haiti, 26 Oct 2015–14 Jan 2016. Bristow et al. 2017. | Pregnant women ≥18 years attending GHESKIO clinics | Participants self-collected samples, which were tested by GeneXpert as standard of care. Women returned to GHESKIO within 7 days to receive test results and treatment if test-positive |

|

|

|

| Assessment of GeneXpert test implementation in Prince Cyril Zulu Communicable Disease Centre (PCZCDC), a large public healthcare clinic that provides “general primary health care services for adults free of charge” in Durban city centre, KwaZulu-Natal, South Africa, May 2016—Jan 2017. Garrett et al. 2018. | HIV-negative women, at high HIV risk, aged 18–40 years, attending PCZCDC for STI care | Implementation of GeneXpert, Trichomonas vaginalis (TV) (OSOM® Rapid Trichomonas Test), and bacterial vaginosis (BV) (Gram stain microscopy) to evaluate how expedited partner therapy (EPT) introduction could be accelerated through use of POCTs. Results available within 2 hours. Test-positive women were immediately treated and offered EPT packs. STI-positive women invited to participate in focus group discussions on POC testing and EPT. An EPT questionnaire was administered by telephone at one-week follow-up. Women were retested for STIs in the clinic after 6 and 12 weeks. |

|

|

|

| Randomised controlled trial in an urban academic emergency department (ED), USA. April 2015—May 2016. Gaydos et al. 2019. | Women undergoing pelvic examinations and CT/NG testing as part of their ED standard of care | Control: standard-of-care CT/NG NAAT, with 2- to 3-day turnaround time.Intervention: rapid GeneXpert test, in addition to the standard-of-care NAAT. Rapid results immediately provided, and treatment provided to all patients according to providers’ clinical judgment |

|

|

|

| Cross-over cluster randomised controlled trial of routine GeneXpert implementation to improve infection management (intervention; n = 6 health services) compared to standard care (control; n = 6 health services). Primary health services that provide care to Indigenous people in regional or remote locations in Western Australia, Far North Queensland, and South Australia. June 1, 2013—Feb 29, 2016. Guy et al. 2018. | Patients aged 16–29 years attending participating health services in a 12-month period | Health services were provided training for use of the GeneXpert and equipment, supplies for ≤150 GeneXpert tests; participating services were reimbursed for retesting (Further details provided [52]) |

|

|

|

| Randomised controlled trial in an urban ED, Washington DC, USA, Oct 2013—Oct 2014. May et al. 2016. | Symptomatic patients presenting to an urban ED, and where treating provider was ordering diagnostic CT/NG test | Control: standard-of-care CT/NG NAAT, with results available within 1–4 days Intervention: rapid GeneXpert test, with results provided during ED visit. Treatment was provided at ED provider’s discretion. After patient discharge, treating physician filled out a clinician survey |

|

|

|

| Assessment of GeneXpert introduction in antenatal clinic (ANC), Kinshasa, Kisantu health zone, Democratic Republic of Congo. No dates given. Mvumbi et al. 2017. | Pregnant women attending ANC | Trained clinic staff collected observed if women presented with STI symptoms, and collected vaginal swabs. Samples were tested using GeneXpert CT/NG and TV tests |

|

|

|

| Comparison of patients tested with GeneXpert C to a historical control group tested using a traditional NAAT in an urban community teaching hospital ED, Dec 2014–Jan 2015. Rivard et al. 2017. | Patients ≥15 years of age who were tested for NG/CT | GeneXpert implementation as standard of care. Test-positive patients who received results prior to ED discharge were provided with notification, counselling, and treatment on-site. For patients whose results were not available pre-discharge, providers could offer empiric treatment and then follow-up with results post- discharge |

|

200 consecutive patients tested by GeneXpert compared with 200 historical patients tested with traditional NAAT.

|

|

| Assessment of GeneXpert implementation in Princess Marina Hospital ANC (the main government referral hospital for southern Botswana), Gaborone, Botswana, July—October 2015. Wynn et al. 2016. | Women receiving antenatal care at the clinic, who were aged ≥18 years, gestational age <35 weeks, mentally competent and willing to return to clinic for follow-up care | Women self-collected vaginal swabs, which were tested on-site in the ANC vitals room by GeneXpert for CT, NG, and TV. Women received same-day test results notification, in-person or by telephone. Test-positive women received same-day treatment prior was to leaving clinic |

|

|

|

| Assessment of GeneXpert introduction in one main clinic and three sex-on-premises venues (SOPV) where regular outreach HIV/syphilis POC testing had been taking place, within an urban community context, Brisbane, Australia, 3 March 2017–14 June 2018. Bell et al. 2020. | Prospective consecutive sampling of asymptomatic patients (predominantly MSM), ≥16 years, presenting at any of the four included locations. Patients reporting potential HIV exposure within the past 72 hours of attendance were excluded | Pilot of peer-delivered, community-led service providing POC CT/NG testing. GeneXpert implementation as standard of care in included settings. Participants self-collected samples, which were tested by GeneXpert at main clinic. Participants received their CT/NG results by telephone or SMS within 24 h. Test-positive participants referred for treatment, either in-clinic or elsewhere (community-based services, sexual health services, regular GP and non-regular GP). Peer test facilitators conducted follow-up telephone interviews with test-positive participants 2 weeks post-referral for retesting and treatment. Additional online ‘Post-Referral Survey’ for test-positive participants at 2-week post-testing follow-up interview phone call. |

|

|

|

| Outreach services | Assessment of GeneXpert implementation in a mobile healthcare van at an annual community event in a metropolitan area with high STI prevalence. 2012 and 2013, no specific location given. Hesse et al. 2015. | Males and females ≤14 years | All specimens were self-collected in the van. Participants with positive results were notified and prescribed treatment. Questionnaire to assess acceptability of test turnaround times and self-sample collection |

|

|

| Assessment of GeneXpert introduction and same-day CT/NG treatment. May 2017 to June 2019, Los Angeles California and New Orleans Louisiana, USA. Keizur et al. 2020. | Young people ages 12–24 years with high sexual risk behaviours, recruited online and in advertisements in homeless shelters, lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender organizations and community health centres in Los Angeles, California, and New Orleans, Louisiana USA | Every 4 months, within a 24-month enrolment period, participants attended clinic and self-collected pharyngeal, rectal, and urine or vaginal samples for CT/NG testing using GeneXpert. Positive patient management: Before March 2018 in Los Angeles and November 2018 in New Orleans: participants were referred to a local clinic or their primary care doctor for treatment. After March 2018 in Los Angeles and between 12 November 2018 and 28 February 2019 in New Orleans: participants were offered same-day treatment and expedited partner therapy packs by study staff |

|

|

|

| Assessment of GeneXpert implementation in four community-based settings in Harare, Zimbabwe, participating in CHIEDZA trial (Community based interventions to improve HIV outcomes in youth), June 2019—Jan 2020. Martin et al. 2021. | All youth, aged 16–24 years, accessing CHIEDZA services. | GeneXpert testing within 48 hours of first-catch urine sample provision. Participants able to collect test result the following week, with positive-test participants actively followed-up. |

|

|

|

| Assessment of GeneXpert implementation in urban Walk In Ruhr (WIR) inter-institutional care centre, Germany, Dec 2016 –July 2018. Skaletz-Rorowski et al. 2020. | Asymptomatic youth (14–30 years) approached in schools, universities and youth centres attending sexual health education lectures; sample collection took place at WIR inter-institutional care centre | GeneXpert platform implemented within WIR centre. Samples tested by nurses or doctors immediately after collection | Turn around time (TAT) was defined as the interval between when the swabs were provided to the patient to the time communication of the result to the patient.

initiation of test to initiation of therapy was additionally documented. |

272 participants (133 males, 133 females).

within 48 h |

Implementation of the Cepheid CT/NG GeneXpert demonstrated that faster (and appropriate) treatment was achieved in all settings. This was facilitated by reduced time to notification of results, which was a specific outcome for some studies [47, 58, 60, 63, 69] but same-day treatment was hindered by patients not waiting for test results at the point of care [61, 65], and one study specifically reported increased patient waiting time in-clinic [57]. However, implementation of the test was broadly acceptable in all settings reporting this as an outcome [55, 61, 66–68, 72]. In non-sexual health services, introduction of the Cepheid CT/NG GeneXpert enabled detection of STIs, a service which previously had not been available [57, 64, 66, 67, 69]. Additional benefits beyond immediate patient management were also recorded, including improving partner treatment, reducing transmission, and cost-savings [47, 55, 65, 69].

In Table 4, in addition to the Cepheid CT/NG GeneXpert studies included in Table 3, we report on a wider literature of stakeholder values for implementation of POCTs, including reports of the binx health io CT/NG. Studies reporting implementation of the binx CT/NG in a sexual health specialist service and a University student health clinic (outreach service) in the USA were restricted to implementation without results delivery; at the time of the studies the test was not yet FDA approved [43, 44, 73]. Publication of a UK-based project tracing implementation into routine care did not include assessment of clinical outcomes [73]. Nevertheless, the available studies (albeit limited to the USA and UK) have shown implementation processes of this CT/NG POCT to be highly acceptable to patients [43, 44] and healthcare workers [44, 45, 73].

Table 4. Value proposition for molecular CT/NG POCTs by setting type, based on the value proposition for laboratory medicine [35].

| Value proposition | Sexual health services | General Practice and other non-sexual health specialist services | Outreach services |

|---|---|---|---|

|

Healthcare context (Is it a service redesign issue? Is it a quality improvement issue? Are there any potential conflicts of interest between stakeholders, e.g. disinvestment in other stakeholders’ resources, e.g. alternative diagnostic technology?) |

Specialist health service (level 3) Impact on existing resources and contracts must be considered. |

Primary health service (level 1). If added to pre-existing services, impact on existing resources and contracts must be considered. |

Community health service (level 0). If added to pre-existing services, impact on existing resources and contracts must be considered. |

|

Unmet need (Is it a clinical, process, and/or economic problem?) |

Unmet need is likely to be context and stakeholder dependent. Faster results delivery, reduced time to treatment and appropriate patient management (clinical and process). Potential for increased timely access to sexual healthcare. Patient acquisition of results within one visit has potential to improve CT/NG diagnosis process for patients and healthcare professionals (i.e. via reduction of patient recall). |

||

|

Care pathway context (Is it a screening, diagnosis, or monitoring issue?) |

Screening and diagnosis: in general CT/NG tests are used either for diagnostic purposes in individual clinical cases, or for national screening programmes. As these are not chronic conditions repeat performance of tests to monitor CT and NG over time is not needed. However, test of cure is recommended for all patients diagnosed with NG, and for some patients with CT. | ||

|

Test and its utility(ies) (Is it for screening, diagnosis, candidacy for treatment, guiding use of treatment, monitoring efficacy of, and compliance with, treatment?) |

Screening, diagnosis, guiding use of treatment. | Can be used as a screening tool to increase testing opportunistically among asymptomatic patients and enables symptomatic patients access to rapid diagnosis and guides treatment when needed. | Can be used as a screening tool to increase testing among asymptomatic populations with a high prevalence of infection and enables access to rapid diagnosis and guides treatment when needed. |

|

Resource requirement (What will be the cost of the test? Will there be additional resource requirement, or redundancy, in other parts of the organization?) |

Costs of tests is likely to be higher than laboratory tests, though cost savings may be made in reduction of staff costs for patient recall. Reduction of time for healthcare professionals to conduct patient recall. May necessitate changes to clinical pathways / duration of patient visit to accommodate test time to results to enable same-day results delivery and treatment if needed. |

Costs of tests is likely to be higher than laboratory tests, though costs savings may be found in reducing inappropriate antibiotic treatment. May necessitate changes to clinical pathways / duration of patient visit to accommodate test time to results to enable same-day results delivery and treatment if needed. |

Costs of tests is likely to be higher than laboratory tests. Redeployment of healthcare professionals may need to be employed to enable outreach service. Mobile testing van, new or existing community space will be needed to provide testing and treatment. |

|

Benefits of using test (Will it improve diagnosis and treatment, process of care, and/or patient experience? Will it reduce cost of care?) |

Faster time to results improves faster time to treatment where needed which may result in: reduction in inappropriate treatment (reduced syndromic treatment); expedited partner therapy; reduction in onward progression of disease (sequelae). |

Faster time to results improves faster time to treatment where needed, which may result in: avoiding unnecessary treatment; reduction in loss to follow-up and recall efforts; expedited contact tracing; onward progression of disease (sequelae); potential for widening testing and screening coverage. |

Faster time to results improves faster time to treatment where needed, which may also result in: reduction in inappropriate treatment (reduced syndromic treatment); reduction of onward progression of disease (sequelae); expedited access to treatment for contacts; potential for widening testing and screening coverage. |

|

Impact on outcomes (Will it improve patient morbidity and mortality, access to care, and/or efficiency of care? Will it reduce the complications of care?) |

Potential to increase appropriate antibiotic treatment for infections. Potential for reduced time to results and treatment to reduce unnecessary antibiotic use. Reduction in inappropriate treatment (reduced syndromic treatment) may reduce antibiotic resistance. |

Potential to raise awareness among healthcare professionals and thus increase their offer of STI testing to patients. Potential to increase appropriate antibiotic treatment for infections. Potential for reduced time to results and treatment to reduce unnecessary antibiotic use. Improvement in patient access to STI testing enables earlier treatment of previously undiagnosed infections. |

Improvement in patient access to STI testing enables earlier treatment of previously undiagnosed infections. Potential to increase appropriate antibiotic treatment for infections. |

|

Evidence of clinical effectiveness (Is there evidence of improved diagnostic accuracy? Is there is evidence of improved clinical outcome?) |

Evidence of similar accuracy to laboratory-based tests must be established. Improved clinical outcomes including reduction in inappropriate treatment (reduced syndromic treatment); onward progression of disease (sequelae). |

||

|

Evidence of cost effectiveness Is there evidence of cost effectiveness when using the test?) |

May reduce costs to the clinic and reduce healthcare professional time; cost-effectiveness models in higher-income countries show value-for-money when considering transmission and progression of disease. | Cost effectiveness is likely to depend on impact of diagnoses on larger public health outcomes (as per specialist service modelling). | Cost effectiveness is likely to depend on impact of diagnoses on larger public health outcomes (as per specialist service modelling). |

|

Translation challenges (What is the plan for translating the evidence of effectiveness into routine practice?) |

The instrument should be easy to use and allow connectivity to existing clinical recording systems to provide rapid access to results. Guidance for implementation of new tests in services is often lacking; clinical leads are responsible for overseeing clinical pathway changes so implementation is likely to be service-driven and thus inconsistently delivered. |

The instrument should be easy to use and allow connectivity to existing clinical recording systems to provide rapid access to results. Training in equipment may be needed prior to implementation. Training in sexual healthcare provision may be needed for healthcare professionals. |

The instrument should be easy to use and allow connectivity to existing clinical recording systems to provide rapid access to results. Training in equipment may be needed prior to implementation. Training in sexual healthcare provision may be needed for healthcare professionals. |

|

Change in practice (Will there be a revised care guideline, e.g. revised diagnostic pathway) |

Stakeholder engagement is necessary to enable implementation. May necessitate changes to clinical pathways / duration of patient visit to accommodate test time to results to enable same-day results delivery and treatment if needed. |

Stakeholder engagement is necessary to enable implementation. May necessitate changes to clinical pathways / duration of patient visit to accommodate test time to results to enable same-day results delivery and treatment if needed. |

Stakeholder engagement is necessary to enable implementation. Provision of STI / CT/NG screening where previously none present. |

|

Change in process (Will there be rapid access to results, reduction in clinic visit requirement, care provided in different setting?) |

Reduction in time to result. Rapid access to infection-specific treatment (for CT and/or NG positive patients). |

Reduction in time to result. Reduction in follow-up visits for those found positive for infection. |

Provision of STI / CT/NG screening where previously none present. |

|

Change in resource requirement (Will there be reduced use of alternative diagnostic tools, reduced length of stay, reduced need for hospitalization?) |

If time to results cannot be achieved within the standard clinical visit time, patients will have an increased length of stay. The number of patients managed with POCTs may result in the reduction of laboratory-based CT/NG tests conducted. |

If time to results cannot be achieved within the standard clinical visit time, patients will have an increased length of stay. The number of patients managed with POCTs may result in the reduction of laboratory-based CT/NG tests conducted. |

Additional resources may be needed to provide this as a new service. |

|

Implementation metrics (What are the intermediate outcome measures (clinical, process and economic), e.g., HbA1c, new test usage, previous test usage, time to treatment, clinic visits, length of stay, to be employed in performance management of implementation) |

Clinical outcome measures: number of patients appropriately treated; number of partner notifications averted; number of patient follow-up visits averted; number of patients receiving same-day result; numbers of partners appropriately treated. Process outcome measures: Feasibility and acceptability among healthcare professionals and patients; time from sample taking to result to patient; impact on patient waiting times (as compared to standard care). Economic outcome measures: initial costs and ongoing cost of POCT contract, as compared with standard care (laboratory-based testing); clinical pathway change cost comparison, i.e., reduction of treatment, follow up and contact tracing costs, any change to staff time for testing and results delivery (as per specialist services). |

Clinical outcome measures: number of patients appropriately treated; number of patients receiving same-day result; number of partners appropriately treated. Process outcome measures: Feasibility and acceptability among healthcare professionals and patients; time from sample taking to result to patient; impact on patient waiting times (as compared to standard care). Economic outcome measures: initial costs and ongoing cost of POCT contract, as compared with standard care (laboratory-based testing); clinical pathway change cost comparison, i.e., reduction of follow up and contact tracing costs, any change to staff time for testing and results delivery. |

Clinical outcome measures: number of patients appropriately treated; number of patients receiving same-day result; number of partners treated. Process outcome measures: Feasibility and acceptability among healthcare professionals and patients; time from sample taking to result to patient. Economic outcome measures: cost per screening; cost per infection detected; total cost of service. |

|

Accountability (Who will benefit from use of test? Who may experience dis-benefit? Who will manage the implementation?) |

There is potential for benefit to the health system, health care professionals, patients and the population. | ||

| Healthcare professionals will be responsible for performing the tests and managing new patient care pathways. | |||

| Potential disbenefit to population infection surveillance systems. | |||

| The number of patients managed with POCTs may result in the reduction of laboratory-based CT/NG tests conducted. | |||

Some of the values for molecular CT/NG POCTs cross-cut all settings: unmet need, care pathway context, and accountability. However, the majority of values are setting specific. Sexual health services and outreach services have the least overlap in values, whereas GP and other non-sexual health specialist services “bridge” between them. GP and other non-sexual health specialist services and outreach services share the value that the test is most likely to be used as a screening tool to increase testing, rather than the multiple purposes of screening, diagnosis, and guiding use of treatment, as is necessary in sexual health services. Non-specialist settings also have similarities for evidence of cost-effectiveness and translation challenges as this often requires new staff and training [52, 74, 75]. Sexual health services and GP and other non-specialist services overlap most for change in practice and change in resource requirement, and implementation metrics.

Discussion

The Cepheid CT/NG GeneXpert test was the only molecular CT/NG POCT to have been implemented and evaluated as part of routine practice in the published literature. Although it did not meet all TPP or REASSURED criteria, review of its implementation and reported benefits demonstrated this did not preclude it from bringing value to a service or its stakeholders. Of note, although the cost-per-test of the Cepheid CT/NG GeneXpert exceeds the minimum TPP and REASSURED recommendations [49], cost-effectiveness models show relative value-for-money of POCTs when considering onward transmission and progression of disease [50, 75–78]. Thus, it is only when these tools and frameworks are examined within the delivery context that sense-making happens around the adoption and implementation decision-making processes [26, 79]. This was further emphasised when extracting these findings for development of the value proposition, where we found that values differed both within and between healthcare settings.

To our knowledge, this is the first report that systematically reviews the literature on molecular CT/NG POCTs’ implementation in routine practice, to assess the value different stakeholders in different settings place on them. Furthermore, we have synthesised this evidence to develop a value proposition to facilitate decision-making around their integration into sexual healthcare. By reviewing the Cepheid CT/NG GeneXpert’s implementation, we were able to demonstrate the diversity of use in various healthcare settings (specialist, non-specialist, and outreach), and in different areas of the world, allowing a more robust review of the test’s value from multiple stakeholder perspectives.

Of particular interest is the finding that sexual health specialist and outreach services had the least overlap in values. This underlines the need for specific measures of value to be identified by service type: if a service does not already exist (as in outreach), mapping outcome measures such as costs of changes to existing clinical pathways and associated costs of task redeployment are redundant, whereas these are clearly important measures if redesigning an existing sexual health clinic service. Similarly, consideration of existing services provided within specific settings matter: measuring the impact of replacing traditional laboratory CT/NG NAATs with POCTs (including impact on current laboratory contracts) requires different evaluation indicators than does the replacement of syndromic management of possible infections with POCTs. The examples presented here highlight our key finding: the value of novel diagnostic test adoption and implementation is perceived differently depending on your setting and stakeholder role. It is therefore critical for the values for the specific service to be identified before a test and its mode of implementation are chosen.

We did not consider studies that focused solely on test performance, or reports on test implementation in research-use-only environments, as we considered these outside the remit of this report. By limiting ourselves to implementation studies, we may have missed identifying additional values of the test, although we tried to address this by including research study outcomes in the final value proposition (Table 4). We only searched two databases (Medline and Embase), but given the subject area, the inclusion of conference abstracts, and the fact we searched references of included papers, we think all relevant publications have been identified. It is likely, however, that there are other cases of implementation that have not been reported in the literature; publications available will most likely reflect the values of the study authors, and not those of all stakeholders involved. Furthermore, multiple value propositions for POCTs exist [34, 35]; we chose one, based on its relevance to laboratory medicine and inclusion of diversity of stakeholder values.

We found variability between reports of implementation studies and their outcomes, as well as in their study quality. Not all of the studies included reported on clinical pathways (i.e. procedures), which would have outlined how the test was used. As a result, we cannot directly compare the results of each setting, which precluded metanalysis and limits our ability to understand the value of the test to each stakeholder in each of the different contexts. We encourage authors to have clear objectives, to report on outcomes matching these objectives, and to follow the appropriate international standards of reporting for their chosen study design. However, although uniformity would enable better evaluation across different settings, it would unlikely reflect the diversity of outcomes that need to be measured in those different settings; the heterogeneity in study design, test implementation and impacts assessed in the literature in itself demonstrates the variability of values placed on molecular CT/NG POCTs by different stakeholders and in different settings. For example, the inclusion of qualitative studies in the value proposition we propose enabled us to broaden our understanding of the contextual values of these POCTs. We suggest more work be done to understand the values of a wider variety of stakeholders in order to encourage them to be actively involved in study design and implementation, which would lead to reporting of more relevant outcomes of interest. We also encourage reflexive reporting on lessons learned, particularly with regards to study design and outcomes measures; if any data were found to be important when assessing the POCTs for adoption but were not thought to be important when the evaluation was designed, this would be useful to consider in future studies and their design.

Despite the diversity of Cepheid CT/NG GeneXpert implementation mechanisms, there were commonalities among study outcomes to explore. Patient benefit was measured in each, although the indicators that were measured varied, including numbers of patients who received a same-day result, time between clinic visit and/or sample taking and result provision, and patient acceptability. Among CT/NG positive patients, time to treatment, and partner notification/treatment measures were also commonly reported.

Healthcare professionals are a particularly important stakeholder group for implementation and previous research to identify an ideal test has focused on them [80]; clinicians are often responsible for new pathway construction [52, 81], and research has shown that nurses’ inclusion in quality improvement projects may improve job satisfaction and reduce workforce instability [82]. Healthcare providers across the included studies placed value in patient benefits, specifically the reduced time to result notification, and for those patients testing positive, reduced time to treatment. Qualitative studies, in particular those among healthcare professionals participating in the TTANGO studies in Australia, reported high levels of satisfaction with the Cepheid CT/NG GeneXpert, and related this to their belief in the test’s ability to improve patient and public health outcomes, as well as the device’s ease of use [83, 84]. However, in some studies [61, 65], the faster time to results delivery was negatively impacted by patients being unwilling or unable to wait for their results at the point of care; qualitative studies providing insight into the appropriate implementation of CT/NG POCTs into routine healthcare practice may help to mitigate this issue [85].

No test fulfils all the WHO TPP or (RE)ASSURED criteria [9, 11, 12]. However, even less-than-perfect technologies have the potential to improve patient outcomes [86, 87]; waiting for the ideal molecular POCT before implementing tests that are currently available has implications both for individual patients and public health [88, 89]. This research synthesis shows the potential for less-than-perfect CT/NG POCTs to hold value for multiple stakeholders in different healthcare settings. Therefore, we recommend that stakeholders in sexual healthcare explore the potential for existing POCTs to provide value to their services. As more molecular CT/NG POCTs are developed and approved by regulatory bodies, the specific characteristics of each may be more or less suited to particular settings, and the value proposition developed could help decision-makers determine the most important values for them and their stakeholders to guide test choice.

Conclusions

Criteria have been set for the development of ideal CT/NG POCTs. Similarly, guidance has been developed for the adoption of novel diagnostics into health systems. This guidance is necessary to protect patients and direct health systems towards efficient use of resources to meet public health goals, and attempts to cater to a diverse range of stakeholder needs and expectations. The plurality of these needs means that a single test is unlikely to be viewed as a panacea or “magic bullet” for solving the clinical, social and structural issues around provision of CT/NG diagnosis across all settings. Stakeholders wishing to improve their service through the implementation of CT/NG POCTs should be supported to identify the values most relevant to their settings and context rather than waiting for the ideal test to be produced: there is no magic bullet.

Supporting information

(DOCX)

(DOCX)

(DOCX)

(DOCX)

(DOCX)

(DOCX)

(DOCX)

(DOCX)

(DOCX)

Acknowledgments

Special thanks to Professors Christopher Price and Trisha Greenhalgh for organising the Maximising Value from New Diagnostic Tests workshop in 2019, which inspired this publication.

Abbreviations

- CE

Conformité Européene

- CT

Chlamydia trachomatis

- ED

Emergency Department

- FDA

Food and Drug Administration

- GP

General Practice

- GPS

Global Positioning System

- LMICs

Low- and Middle-Income Countries

- NG

Neisseria gonorrhoeae

- POCT

Point-of-Care-Test

- STI

Sexually Transmitted Infection

- TPP

Target Product Profile

- TV

Trichomonas vaginalis

- WHO

World Health Organization

Data Availability

All relevant data are within the manuscript and its Supporting information files.

Funding Statement

The authors received no specific funding for this work.

References

- 1.World Health Organization. Report on global sexually transmitted infection surveillance, 2018. Geneva; 2018. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Rowley J, Vander Hoorn S, Korenromp E, Low N, Unemo M, Abu-Raddad LJ, et al. Chlamydia, gonorrhoea, trichomoniasis and syphilis: Global prevalence and incidence estimates, 2016. Bull World Health Organ. 2019. Aug 1;97(8). doi: 10.2471/BLT.18.228486 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.O’Neill J. Tackling Drug-resistant Infections Globally: Final Report and Reccomendations. [Internet]. 2016. https://amr-review.org/sites/default/files/160525_Finalpaper_with_ cover.pdf

- 4.Wi TEC, Ndowa FJ, Ferreyra C, Kelly-Cirino C, Taylor MM, Toskin I, et al. Diagnosing sexually transmitted infections in resource-constrained settings: challenges and ways forward. Vol. 22, Journal of the International AIDS Society. 2019. doi: 10.1002/jia2.25343 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Unemo M, Bradshaw CS, Hocking JS, de Vries HJC, Francis SC, Mabey D, et al. Sexually transmitted infections: challenges ahead. Vol. 17, The Lancet Infectious Diseases. Lancet Publishing Group; 2017. p. e235–79. doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(17)30310-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Peeling RW, Holmes KK, Mabey D, Ronald A. Rapid tests for sexually transmitted infections (STIs): The way forward. Sex Transm Infect. 2006;82(SUPPL. 5):1–6. doi: 10.1136/sti.2006.024265 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Tuite AR, Gift TL, Chesson HW, Hsu K, Salomon JA, Grad YH. Impact of rapid susceptibility testing and antibiotic selection strategy on the emergence and spread of antibiotic resistance in Gonorrhea. J Infect Dis. 2017;216(9). doi: 10.1093/infdis/jix450 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Murtagh MM, The Murtagh Group L. The Point-of-Care Diagnostic Landscape for SexuallyTransmitted Infections (STIs) [Internet]. 2019 [cited 2020 Mar 10]. https://www.who.int/reproductivehealth/topics/rtis/Diagnostic-Landscape-for-STIs-2019.pdf?ua=1

- 9.Kettler H, White K, Hawkes S. Mapping the landscape of diagnostics for sexually transmitted infections: key findings and recommendations [Internet]. 2003. https://www.who.int/tdr/publications/documents/mapping-landscape-sti.pdf

- 10.Mabey D, Peeling RW, Ustianowski A, Perkins MD. Diagnostics for the developing world. Vol. 2, Nature Reviews Microbiology. 2004. p. 231–40. doi: 10.1038/nrmicro841 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Land KJ, Boeras DI, Chen X-S, Ramsay AR, Peeling RW. REASSURED diagnostics to inform disease control strategies, strengthen health systems and improve patient outcomes. Nat Microbiol [Internet]. 2019. Jan 13 [cited 2019 Aug 28];4(1):46–54. Available from: http://www.nature.com/articles/s41564-018-0295-3 doi: 10.1038/s41564-018-0295-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Toskin I, Murtagh M, Peeling RW, Blondeel K, Cordero J, Kiarie J. Advancing prevention of sexually transmitted infections through point-of-care testing: target product profiles and landscape analysis. Sex Transm Infect. 2017. Dec 1;93(S4):S69–80. doi: 10.1136/sextrans-2016-053071 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Toskin I, Peeling RW, Mabey D, Holmes K, Ballard R, Kiarie J, et al. Point-of-care tests for STIs: the way forward. Vol. 93, Sexually transmitted infections. 2017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Cristillo AD, Bristow CC, Peeling R, Van Der Pol B, De Cortina SH, Dimov IK, et al. Point-of-care sexually transmitted infection diagnostics: Proceedings of the STAR sexually transmitted infection-clinical trial group programmatic meeting. In: Sexually Transmitted Diseases. Lippincott Williams and Wilkins; 2017. p. 211–8. doi: 10.1097/OLQ.0000000000000572 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Herbst De Cortina S, Bristow CC, Joseph Davey D, Klausner JD. A Systematic Review of Point of Care Testing for Chlamydia trachomatis, Neisseria gonorrhoeae, and Trichomonas vaginalis. Vol. 2016, Infectious Diseases in Obstetrics and Gynecology. Hindawi Limited; 2016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Unemo M, Ballard R, Ison C, Lewis D, Ndowa F, Peeling R. Laboratory diagnosis of sexually transmitted infections, including human immunodeficiency virus. World Health Organization. 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kelly H, Coltart CEM, Pant Pai N, Klausner JD, Unemo M, Toskin I, et al. Systematic reviews of point-of-care tests for the diagnosis of urogenital Chlamydia trachomatis infections [Internet]. Vol. 93, Sexually transmitted infections. BMJ Publishing Group Ltd; 2017. [cited 2020 Aug 11]. p. S22–30. https://sti.bmj.com/content/93/S4/S22 doi: 10.1136/sextrans-2016-053067 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Fifer H, Saunders J, Soni S, Sadiq ST, FitzGerald M. 2018 UK national guideline for the management of infection with Neisseria gonorrhoeae. Int J STD AIDS [Internet]. 2020. Jan 1 [cited 2020 May 20];31(1):4–15. Available from: https://www.bashhguidelines.org/media/1238/gc-2018.pdf doi: 10.1177/0956462419886775 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Barrow RY, Ahmed F, Bolan GA, Workowski KA. Recommendations for Providing Quality Sexually Transmitted Diseases Clinical Services, 2020. MMWR Recomm Reports [Internet]. 2020. Jan 3 [cited 2021 Mar 3];68(5):1–20. Available from: http://www.cdc.gov/mmwr/volumes/68/rr/rr6805a1.htm?s_cid=rr6805a1_w doi: 10.15585/mmwr.rr6805a1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Nwokolo NC, Dragovic B, Patel S, Tong CW, Barker G, Radcliffe K. 2015 UK national guideline for the management of infection with Chlamydia trachomatis Introduction and methodology Scope and purpose. [cited 2021 Mar 3]; www.bashh.org/guidelines [DOI] [PubMed]

- 21.Unemo M, Ross J, Serwin AB, Gomberg M, Cusini M, Jensen JS. 2020 European guideline for the diagnosis and treatment of gonorrhoea in adults. Int J STD AIDS [Internet]. 2020. [cited 2021 Mar 3];0(0):1–17. Available from: https://www.who.int/reproductivehealth/ doi: 10.1177/0956462420949126 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Cepheid | Xpert CT/NG [Internet]. [cited 2019 Aug 18]. http://www.cepheid.com/us/cepheid-solutions/clinical-ivd-tests/sexual-health/xpert-ct-ng

- 23.binx health Receives FDA 510(k) Clearance for Rapid Point of Care Platform for Women’s Health [Internet]. [cited 2019 Aug 19]. https://mybinxhealth.com/news/binx-health-receives-fda-510k-clearance-for-rapid-point-of-care-platform-for-womens-health/

- 24.World Health Organization, Priority Medical Devices Project. Barriers to innovation in the field of medical devices [Internet]. 2010. https://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/handle/10665/70457/WHO_HSS_EHT_DIM_10.6_eng.pdf

- 25.Pai NP, Vadnais C, Denkinger C, Engel N, Pai M. Point-of-care testing for infectious diseases: diversity, complexity, and barriers in low- and middle-income countries. PLoS Med. 2012;9(9). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Greenhalgh T. How to implement evidence-based healthcare. Wiley-Blackwell; 2018. doi: 10.1097/XEB.0000000000000147 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Lambert H. Accounting for EBM: Notions of evidence in medicine. Soc Sci Med. 2006. Jun;62(11):2633–45. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2005.11.023 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Goldenberg MJ. On evidence and evidence-based medicine: Lessons from the philosophy of science. Soc Sci Med. 2006. Jun;62(11):2621–32. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2005.11.031 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Fraser A, Baeza JI, Boaz A. ‘Holding the line’: A qualitative study of the role of evidence in early phase decision-making in the reconfiguration of stroke services in London. Heal Res Policy Syst. 2017. Jun 9;15(1). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.John AS, Cullen L, Jülicher P, Price CP. Developing a value proposition for high-sensitivity troponin testing. Clin Chim Acta. 2018. Feb 1;477:154–9. doi: 10.1016/j.cca.2017.12.007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Barnett J, Vasileiou K, Djemil F, Brooks L, Young T. Understanding innovators’ experiences of barriers and facilitators in implementation and diffusion of healthcare service innovations: A qualitative study. BMC Health Serv Res. 2011;11. doi: 10.1186/1472-6963-11-342 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Price CP, John AS, Christenson R, Scharnhorst V, Oellerich M, Jones P, et al. Leveraging the real value of laboratory medicine with the value proposition. Clin Chim Acta. 2016. Nov 1;462:183–6. doi: 10.1016/j.cca.2016.09.006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Deloitte Development LLC. A Framework for Comprehensive Assessment of the Value of Diagnostic Tests. May 2017. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Walter FM, Thompson MJ, Wellwood I, Abel GA, Hamilton W, Johnson M, et al. Evaluating diagnostic strategies for early detection of cancer: The CanTest framework. BMC Cancer. 2019;19(1):1–11. doi: 10.1186/s12885-018-5219-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Price CP, St John A. Anatomy of a value proposition for laboratory medicine. Clin Chim Acta [Internet]. 2014. Sep 25 [cited 2020 Jan 31];436:104–11. Available from: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/24880041 doi: 10.1016/j.cca.2014.05.017 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Price CP, St. John A. Innovation in healthcare. The challenge for laboratory medicine. Vol. 427, Clinica Chimica Acta. 2014. p. 71–8. doi: 10.1016/j.cca.2013.09.043 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Page MJ, McKenzie JE, Bossuyt PM, Boutron I, Hoffmann TC, Mulrow CD, et al. The PRISMA 2020 statement: An updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews [Internet]. Vol. 372, The BMJ. BMJ Publishing Group; 2021. [cited 2021 May 10]. Available from: 10.1136/bmj.n71 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.JBI. Critical appraosal tools [Internet]. https://jbi.global/critical-appraisal-tools

- 39.Ma L-L, Wang Y-Y, Yang Z-H, Huang D, Weng H, Zeng X-T. Methodological quality (risk of bias) assessment tools for primary and secondary medical studies: what are they and which is better? Mil Med Res [Internet]. 2020;7. Available from: https://mmrjournal.biomedcentral.com/articles/10.1186/s40779-020-00238-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.National Heart Lung and Blood Institute. Study Quality Assessment Tools [Internet]. https://www.nhlbi.nih.gov/health-topics/study-quality-assessment-tools

- 41.Center for Evidence-Based Management. Critical Appraisal Questions for a Survey [Internet]. https://www.cebma.org/wp-content/uploads/Critical-Appraisal-Questions-for-a-Survey.pdf

- 42.National Institute for Clinical Excelllence (NICE). Appraisal checklists evidence tables grade and economic profiles [Internet]. https://www.nice.org.uk/process/pmg20/resources/appendix-h-appraisal-checklists-evidence-tables-grade-and-economic-profiles-pdf-8779777885

- 43.Widdice LE, Hsieh Y-H, Silver B, Barnes M, Barnes P, Gaydos CA. Performance of the Atlas Genetics Rapid Test for Chlamydia trachomatis and Women’s Attitudes Toward Point-Of-Care Testing. Sex Transm Dis [Internet]. 2018. Nov 1 [cited 2021 Mar 24];45(11):723–7. Available from: https://journals.lww.com/00007435-201811000-00003 doi: 10.1097/OLQ.0000000000000865 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Gettinger J, Van Wagoner N, Daniels B, Boutwell A, Van Der Pol B. Patients Are Willing to Wait for Rapid Sexually Transmitted Infection Results in a University Student Health Clinic. Sex Transm Dis [Internet]. 2020. Jan 1 [cited 2021 Mar 24];47(1):67–9. Available from: doi: 10.1097/OLQ.0000000000001083 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Pacho A, Heming De-Allie E, Furegato M, Harding-Esch E, Sadiq ST, Fuller S. Identifying key stakeholders and their roles in the integration of POCTs for STIs into clinical services. Sex Transm Infect. 2019;95(Suppl 1):A1–376. [Google Scholar]

- 46.Nicholls JE, Turner KME, North P, Ferguson R, May MT, Gough K, et al. Cross-sectional study to evaluate Trichomonas vaginalis positivity in women tested for Neisseria gonorrhoeae and Chlamydia trachomatis, attending genitourinary medicine and primary care clinics in Bristol, South West England. Sex Transm Infect. 2018. Mar 1;94(2):93–9. doi: 10.1136/sextrans-2016-052942 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Whitlock GG, Gibbons DC, Longford N, Harvey MJ, McOwan A, Adams EJ. Rapid testing and treatment for sexually transmitted infections improve patient care and yield public health benefits. Int J STD AIDS. 2018. Apr 1;29(5):474–82. doi: 10.1177/0956462417736431 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Bristow CC, Morris SR, Little SJ, Mehta SR, Klausner JD. Meta-analysis of the Cepheid Xpert® CT/NG assay for extragenital detection of Chlamydia trachomatis (CT) and Neisseria gonorrhoeae (NG) infections. Vol. 16, Sexual Health. CSIRO; 2019. p. 314–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Jacobsson S, Boiko I, Golparian D, Blondeel K, Kiarie J, Toskin I, et al. WHO laboratory validation of Xpert® CT/NG and Xpert® TV on the GeneXpert system verifies high performances. APMIS. 2018. Dec 1;126(12):907–12. doi: 10.1111/apm.12902 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Huang W, Gaydos CA, Barnes MR, Jett-Goheen M, Blake DR. Comparative effectiveness of a rapid point-of-care test for detection of Chlamydia trachomatis among women in a clinical setting. Sex Transm Infect. 2013. Mar;89(2):108–14. doi: 10.1136/sextrans-2011-050355 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Gaydos CA, Van Der Pol B, Jett-Goheen M, Barnes M, Quinn N, Clark C, et al. Performance of the cepheid CT/NG Xpert rapid PCR test for detection of Chlamydia trachomatis and Neisseria gonorrhoeae. J Clin Microbiol. 2013. Jun;51(6):1666–72. doi: 10.1128/JCM.03461-12 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Guy RJ, Natoli L, Ward J, Causer L, Hengel B, Whiley D, et al. A randomised trial of point-of-care tests for chlamydia and gonorrhoea infections in remote Aboriginal communities: Test, Treat ANd GO- the "TTANGO" trial protocol. BMC Infect Dis [Internet]. 2013. Oct 18 [cited 2019 Aug 29];13(1):485. Available from: doi: 10.1186/1471-2334-13-485 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Gaydos CA, Ako MC, Lewis M, Hsieh YH, Rothman RE, Dugas AF. Use of a Rapid Diagnostic for Chlamydia trachomatis and Neisseria gonorrhoeae for Women in the Emergency Department Can Improve Clinical Management: Report of a Randomized Clinical Trial. Ann Emerg Med [Internet]. 2019. Jul 1 [cited 2021 Mar 24];74(1):36–44. Available from: doi: 10.1016/j.annemergmed.2018.09.012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Garrett NJ, Osman F, Maharaj B, Naicker N, Gibbs A, Norman E, et al. Beyond syndromic management: Opportunities for diagnosis-based treatment of sexually transmitted infections in low- and middle-income countries. Cameron DW, editor. PLoS One [Internet]. 2018. Apr 24 [cited 2021 Mar 24];13(4):e0196209. Available from: doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0196209 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Bristow CC, Mathelier P, Ocheretina O, Benoit D, Pape JW, Wynn A, et al. Chlamydia trachomatis, Neisseria gonorrhoeae, and Trichomonas vaginalis screening and treatment of pregnant women in Port-au-Prince, Haiti. Int J STD AIDS. 2017;28(11):1130–4. doi: 10.1177/0956462416689755 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Bourgeois-Nicolaos N, Jaureguy F, Pozzi-Gaudin S, Masson C, Guillet-Caruba C, Lavisse F, et al. Benefits of Rapid Molecular Diagnosis of Chlamydia Trachomatis and Neisseria Gonorrhoeae Infections in Women Attending Family Planning Clinics. Sex Transm Dis [Internet]. 2015. Nov [cited 2021 Mar 4];42(11):652–3. Available from: https://journals.lww.com/00007435-201511000-00011 doi: 10.1097/OLQ.0000000000000351 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Badman SG, Vallely LM, Toliman P, Kariwiga G, Lote B, Pomat W, et al. A novel point-of-care testing strategy for sexually transmitted infections among pregnant women in high-burden settings: results of a feasibility study in Papua New Guinea. BMC Infect Dis [Internet]. 2016. Dec 6 [cited 2020 Feb 3];16(1):250. Available from: doi: 10.1186/s12879-016-1573-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Wingrove I, McOwan A, Nwokolo N, Whitlock G. Diagnostics within the clinic to test for gonorrhoea and chlamydia reduces the time to treatment: a service evaluation. Sex Transm Infect [Internet]. 2014. Sep 1 [cited 2019 Oct 7];90(6):474. Available from: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/25118322 doi: 10.1136/sextrans-2014-051580 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Whitlock G, Byrne R, Cooper F, McOwan A. A novel model of care incorporating self-directed care and rapid results management successfully reaches high-risk men who have sex with men. Int J STD AIDS. 2015;26(11):88. [Google Scholar]

- 60.Mandlik E, Plaha K, Jones R, Rayment M. P101 Cutting the time to treatment of chlamydia trachomatis (CT) and neisseria gonorrhoeae (NG) with near-patient molecular diagnostics: the utility of the cepheid genexpert system. Sex Transm Infect [Internet]. 2017. Jun 1 [cited 2021 Mar 24];93(Suppl 1):A49.4–A49. Available from: https://sti.bmj.com/content/93/Suppl_1/A49.4 [Google Scholar]

- 61.Harding-Esch EM, Nori A V., Hegazi A, Pond MJ, Okolo O, Nardone A, et al. Impact of deploying multiple point-of-care tests with a sample first’ approach on a sexual health clinical care pathway. A service evaluation. Sex Transm Infect. 2017. Sep 1;93(6):424–9. doi: 10.1136/sextrans-2016-052988 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Cohen S, Kohn R, Bacon O, La Roca RD, Ooms T, Nguyen T, et al. O14.4 Implementation of point of care gonorrhea and chlamydia testing in an STD clinic PrEP program, san francisco, 2017–2018. In: Sexually Transmitted Infections [Internet]. BMJ; 2019. [cited 2021 Jan 26]. p. A71.3–A72. Available from: http://sti.bmj.com/ [Google Scholar]

- 63.Skaletz‐Rorowski A, Potthoff A, Nambiar S, Wach J, Kayser A, Kasper A, et al. Sexual behaviour, STI knowledge and Chlamydia trachomatis (CT) and Neisseria gonorrhoeae (NG) prevalence in an asymptomatic cohort in Ruhr‐area, Germany: PreYoungGo study. J Eur Acad Dermatology Venereol [Internet]. 2021. Jan 29 [cited 2021 Mar 24];35(1):241–6. Available from: https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1111/jdv.16913 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Martin K, Olaru ID, Buwu N, Bandason T, Marks M, Dauya E, et al. Uptake of and factors associated with testing for sexually transmitted infections in community-based settings among youth in Zimbabwe: a mixed-methods study. Lancet Child Adolesc Heal [Internet]. 2021. Feb 1 [cited 2021 Mar 30];5(2):122–32. Available from: www.thelancet.com/child-adolescent [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]