Abstract

Cleavage and polyadenylation specificity factor 30 (CPSF30) is a ‘zinc finger’ protein that plays a crucial role in the transition of pre-mRNA to RNA. CPSF30 contains five conserved CCCH domains and a CCHC “Zinc Knuckle” domain. CPSF30 activity is critical for pre-mRNA processing. A truncated form of the protein, in which only the CCCH domains are present, has been shown to specifically bind AU-rich pre-mRNA targets; however, the RNA binding and recognition properties of full length CPSF30 are not known. Herein, we report the isolation and biochemical characterization of full length CPSF30. We report that CPSF30 contains one 2Fe-2S cluster in addition to five zinc ions, as measured by ICP-MS, UV-visible and XAS spectroscopies. Utilizing fluorescence anisotropy RNA binding assays, we show that full length CPSF30 has high binding affinity for two types of pre-mRNA targets – AAUAAA and poly U - both of which are conserved sequence motifs present in the majority of pre-mRNAs. Binding to the AAUAAA motif requires that the 5 CCCH domains of CPSF30 be present; whereas, binding to poly U sequences requires the entire, full length CPSF30. These findings implicate the CCHC “Zinc Knuckle” present in the full-length protein as critical for mediating poly U binding. We also report that truncated forms of the protein, containing either just two CCCH domains (ZF2 and ZF3) or the CCHC ‘zinc knuckle’ domain, do not exhibit any RNA binding, indicating that CPSF30/RNA binding requires several ZF (and/or Fe-S cluster) domains working in concert to mediate RNA recognition.

Graphical Abstract

INTRODUCTION

Zinc finger (ZF) proteins are proteins that contain domains with conserved repeats of cysteine and histidine residues. These residues serve as ligands to coordinate zinc, thereby allowing the domain to adopt a folded structure that is functional.1-5 Initially identified as transcription factors, ZFs are now known to facilitate numerous biological processes ranging from signal transduction to membrane association.1-2, 6-9 It has been estimated that 3-10% of all eukaryotic proteins are ZFs, and more recently, a small number of ZFs have been identified in prokaryotes and archaea.10 These estimates for the ubiquity of ZFs come principally from sequence data, and to confirm that proteins annotated as ZFs from proteomics projects are bona fide zinc finger proteins, they must be studied experimentally.11-12

ZFs can be categorized into different classes or families based upon the number of cysteine (C) and histidine (H) residues (e.g. CCHH, CCCH, CCCC etc.) within each ZF domain, as well as the spacing between residues and/or known structures.1, 4, 7, 10, 13-15 One important class is the CCCH class of ZFs. These proteins are often associated with RNA processing events, and the handful that have been characterized biochemically have been shown to be RNA binding proteins, typically targeting adenine/uracil rich RNA sequences.1, 4, 15-17

One member of the CCCH family of ZF proteins that plays a critical biological role is cleavage and polyadenylation specificity factor 30 (CPSF30, also known as CPSF4). CPSF30 is part of a complex of proteins (CPSF160, CPSF100, CPSF30, FIP1, WDR33), collectively referred to as the cleavage and polyadenylation specificity factor (or CPSF). CPSF facilitates the transition of RNA from pre-mRNA to mRNA.2, 18-23 This transition involves the removal of a 3’ poly Uracil (polyU) sequence present in the pre-mRNA strand, after which a 3’ poly Adenine (polyA) sequence is added (Figure 1A). The molecular-level details of how each CPSF protein modulates this important biological transition are not fully known.

Figure 1.

(A) Cartoon diagram of current understanding of CPSF30 function. (B) Diagram of CPSF30 constructs investigated.

Mammalian CPSF30 contains five CCCH domains and one CCHC domain (often referred to as a ‘zinc knuckle’ domain). CPSF30 was initially annotated as a zinc finger protein based upon the presence of the CCCH domains; however, when we isolated a truncated construct of CPSF30, containing just the five CCCH domains (CPSF30-5F, Figure 1B) we discovered that the protein contains a 2Fe-2S cluster in addition to zinc.18 This Fe-S cluster was determined to be coordinated to one of the CCCH ‘zinc finger’ domains. This discovery that an annotated ‘zinc finger’ protein (CPSF30) binds an Fe-S cluster at one of the ‘zinc finger’ domains adds to a growing number of proteins which have been discovered to house Fe-S clusters, despite being annotated as ‘CCCH’ type-zinc fingers. These proteins include Miner, mitoNEET, MiNT and Fep1 underscoring the need to study annotated ZFs experimentally.24-31

We also determined that the truncated CPSF30-5F functions as an RNA binding protein. CCCH type zinc fingers often recognize AU-rich RNA sequences, and we found that the five CCCH domain construct selectively recognizes the polyadenylation signal (PAS, AAUAAA) present in most pre-mRNAs and can be fit to a cooperative binding model (Figure 1A).18 Notably, we discovered that for high affinity RNA binding CPSF30-5F must be loaded with both the 2Fe-2S cluster and zinc, suggesting a role of the 2Fe-2S cluster in RNA recognition.18 Subsequently, two Cryo-EM structures of CPSF30 complexed with other CPSF proteins (CPSF-160, WDR33) along with a short RNA strand containing the PAS (AAUAAA) were reported.32-33 In the structure reported by Sun et al. full length CPSF30 protein was utilized while in the structure reported by Clerici et al., a truncated form containing ZF1-ZF5 (residues 1-178) was utilized. In both structures, only the first three CCCH domains of CPSF30 were visible, and the focus of the work was not on the zinc sites so the zinc atoms were not modeled in with constraints. In addition, in the Cryo-EM structures, there is a singular CPSF30 and a singular RNA strand, suggesting that the cooperativity that we measure for CPSF30-5F/RNA via fluorescence anisotropy binding may reflect sequential domain binding to RNA, rather than dimerization. Nonetheless, these structures provided a snapshot of part of the multi-protein CPSF complex, and revealed that in addition to CPSF30, WDR33 binds RNA, while CPSF-160 is involved in protein-protein interactions with WDR33 and CPSF30. In the Cryo-EM structures, ZF2 and ZF3 from CPSF30 directly bind to RNA suggesting that in the context of the full-length protein, these domains determine RNA recognition. It is not known whether the two CCCH domains alone are sufficient for protein/RNA binding.

CPSF30 also contains a CCHC domain, often called a ‘zinc knuckle’ domain at the 3’ end that is not present in the Cryo-EM structures. The function of this domain has not yet been elucidated. Much like CCCH domain proteins, zinc knuckle domain proteins are often involved in RNA binding, albeit to G/C and U rich targets instead of AU-rich targets.34-37 Most pre-mRNAs contain a conserved U-rich sequence that aids in efficient processing from pre-mRNA to mRNA.38-41 We therefore hypothesized that the CPSF30 ‘zinc knuckle’ domain binds the pre-mRNA U-rich element while the CCCH domains bind to the AU rich PAS signal.

Herein, we tested the hypothesis that the CPSF30 ‘zinc knuckle’ domain binds the pre-mRNA U-rich element by overexpressing and purifying the full length CPSF30 protein and determining its RNA binding properties. We report that full length CPSF30 is isolated and active with one 2Fe-2S cluster and five zinc co-factors. Notably, we show that full length CPSF30 binds to poly uracil RNA with high affinity, in addition to binding to the PAS (AAUAAA) sequence. These results demonstrate, for the first time, that isolated CPSF30 binds to poly uracil sequences. In contrast, CPSF30-5F (which lacks the zinc knuckle domain) does not bind to poly uracil RNA, only binding to the PAS, providing clear evidence that the zinc knuckle domain of CPSF30 is required for poly uracil RNA binding. Additionally, we produced the single zinc knuckle domain of CPSF30 (CPSF30-ZK) and evaluated its ability to bind to poly uracil RNA. No binding to poly uracil RNA was observed for the CPSF30-ZK, revealing that the zinc knuckle domain alone is not sufficient for RNA binding and that other domain elements within CPSF30 are involved in poly uracil RNA binding.

We also sought to characterize the role of ZF2 and ZF3 in binding to the PAS sequence. In the published Cryo-EM structures of CPSF30, the ZF2 and ZF3 domains are in contact with the PAS suggesting that these two domains are critical for RNA binding.32-33 Often proteins with CCCH domains require just two structured domains for high affinity binding to AU-rich RNA targets, as is the case with tristetraprolin; therefore a construct of CPSF30 with just ZF2 and ZF3 has the potential to be sufficient for binding.42-43 We report studies focused on this truncated protein, which reveal that the ZF2 and ZF3 alone are not capable of binding to the PAS hexamer in the absence of the other ZF domains. From these collective data, a mechanism for PAS and polyU RNA binding by CPSF30 that involves multiple ZF domains and specific RNA sequence elements is proposed.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Materials.

ZnCl2, FeCl3, Na2S nonahydrate, ampicillin sodium salt, KCl, Polycytidylic acid, Bovine Serum Albumin, ZnSO4, urea, trifluoracetic acid (TFA) (HPLC grade), Methanol (HPLC grade), SP sepharose resin, glycerol, and RNA (HPLC purified grade) were obtained from Sigma-Aldrich. Isopropyl β-D-1-thiogalactopyranoside (IPTG) was purchased from Research Products International. BL21-DE3 competent cells and amylose resin was acquired from New England Biolabs. Luria Bertani Lennox Broth (LB) and dithiothreitol (DTT) were obtained from American Bio. Glucose was purchased from Calbiochem. Tris base (2-amino-2-(hydroxymethyl)propane-1,3-diol), NaCl, nitric acid (trace metal grade), acetonitrile (HPLC grade), and hydrochloric acid (trace metal grade) were acquired from Fisher Scientific. Iron, zinc, germanium, and scandium ICP-MS standards were obtained from Fluka analytical. Bismuth ICP-MS standard was purchased from Ricca Chemical Company. Rhodium ICP-MS standard was acquired from VWR analytical. ICP-MS tuning solution was obtained from Agilent. MES was acquired from Amresco. TCEP and protease and phosphatase inhibitor tablets were obtained from Thermo Scientific. 4,4’-dithiodipyridine (DTDP) was purchased from Acros Organics. CoCl2 was acquired from Merck.

General considerations.

Extra consideration was taken to ensure that all reagents remained metal free throughout each experiment. Water was purified using a PURELAB flex ultrapure water system and then purified further over chelex resin to ensure the chelation of any contaminating metal ions.

Molecular cloning, expression, and purification of holo-CPSF30-FL.

DNA from the Bos taurus CPSF30 homolog was from Dr. Georges Martin and Dr. Walter Keller (University of Basel, Switzerland). DNA encoding full length CPSF30 was cloned into the pMAL-c5e plasmid (New England Biolabs) utilizing the NdeI and BamHI restriction sites and verified using the University of Maryland Baltimore’s Biopolymer-Genomics core facility.

Full length CPSF30 was cloned into the pMAL-c5e plasmid (holo-CPSF30-FL). BL21-DE3 competent E.coli cells were transformed with holo-CPSF30-FL via heat shock. Transformed cells were incubated for 45 minutes at 37°C. Overnight cultures containing 50 mL of Luria Bertani Lennox Broth (LB Broth (Lennox)) with 100 μg/mL ampicillin were inoculated with 150 μL of transformed BL21-DE3 cells. The next day 10-15 mL of overnight culture were utilized to inoculate 1L of LB Broth (Lennox) containing 100 μg/mL ampicillin and 0.2% glucose (w/v). At an optical density of ~0.3 cultures were supplemented with 0.8 mM ZnCl2 and 0.6 mM FeCl3. Cell cultures were grown at 37°C until an OD600 reached between 0.5-0.6, where protein expression was induced with 1 mM Isopropyl β-D-1-thiogalactopyranoside (IPTG) and media was supplemented with 0.4 mM Na2S • 9H2O. Protein expression was allowed to continue for 3 h at 37 °C, after which, the cells were pelleted at 7,800 x g, 4 °C for 20 min, and stored at −20 °C. Pellets were resuspended in 20 mM Tris, 200 mM NaCl, pH 7.5 with a protease and phosphatase inhibitor tablet (Thermo Scientific). Resuspended pellets were lysed by sonication and centrifuged at 17,710 x g for 20 min at 4°C. Sonicated supernatant was spiked with an additional 300 mM sodium chloride and was loaded onto the amylose column in a final buffer containing 20 mM Tris, 500 mM NaCl, pH 7.5 and incubated at room temperature for 15-20 min with shaking. The supernatant was then allowed to flow through the column. The salt concentration was gradually decreased to a final concentration of 200 mM through subsequent washes. Protein elution was conducted in 20 mM Tris, 200 mM NaCl, 30 mM maltose, pH 7.5. The UV-visible spectrum of the isolated holo-CPSF30-FL protein was measured to ensure purity, after which the protein was concentrated via centrifugation utilizing a 30 kDa molecular weight cutoff spin filter. Protein concentration was determined by utilizing the calculated extinction coefficient, ε, 88200 M−1cm−1 at 278 nm, and the protein purity was verified via SDS-PAGE. CPSF30 was then buffer exchanged into either 20 mM Tris, 100 mM NaCl, pH 8.0 buffer for fluorescence anisotropy studies or 20 mM Tris, 50 mM NaCl, pH 7 for X-ray absorption spectroscopy (XAS) studies utilizing a 30 kDa molecular weight cutoff spin filter. Protein purity and metal loading were verified using SDS-PAGE and ICP-MS respectively.

Molecular cloning, expression, and purification of holo-CPSF30-5F.

holo-CPSF30-5F was cloned, expressed, and purified as previously described by our laboratory with the following exceptions2, 18 During protein expression, 0.8 mM ZnCl2 and 0.6 mM FeCl3 were added to the expression flasks at an OD600 of ~0.3, and 0.4 mM Na2S • 9H2O was added at an OD600 of 0.5-0.6 where the cultures were then induced with the addition of 1 mM IPTG. Protein concentration was determined similarly to holo-CPSF30-FL except a calculated extinction coefficient of 85400 M−1cm−1 at 278 nm was utilized and the protein purity was verified via SDS-PAGE.

Fluorescence Anisotropy (FA) Studies of holo-CPSF30.

CPSF30 binding to RNA was measured using fluorescence anisotropy (FA). Binding studies were performed using an ISS K2 spectrofluorometer configured in the L-format with an excitation wavelength/slit width of 495nm/2mm and an emission wavelength/slit width of 517 nm/1 mm. A 5 mm path quartz fluorometer cuvette containing 500 ul of 5 nM 3’ 6-carboxyfluorescein (6-FAM) fluorescently labeled RNA in 50 mM Tris, 100 mM KCl, 0.3 mg/ml polycytidylic acid, and 0.1 mg/ml bovine serum albumin (BSA) was equilibrated in each cuvette for 5 minutes. The RNA oligomers utilized were purchased from MilliporeSigma at HPLC purified grade. Their sequences are listed in Table 1:

Table 1.

RNA oligomers utilized in this study. The polyadenylation sequence and subsequent mutations are underlined.

| RNA oligomer | RNA sequence (5’-3’) |

|---|---|

| α-syn30 | UCUCACUUUAAUAAUAAAAAUCAUGCUUAU |

| α-syn24 | CACUUUAAUAAUAAAAAUCAUGCU |

| PolyC24 | CACUUUAAUCCCCCCAAUCAUGCU |

| ΔA1,2,4,5 | CACUUUAAUCCUCCAAAUCAUGCU |

| PolyU24 | UUUUUUUUUUUUUUUUUUUUUUUU |

| ARE11 | UUUAUUUAUUU |

| AAU9 | AAUAAUAAU |

| AAU12 | AAUAAUAAUAAU |

| AAU24 | AAUAAUAAUAAUAAUAAUAAUAAU |

For a typical titration, CPSF30 was titrated into the cuvette containing the RNA, and the change in FA was monitored until saturation. After each addition of protein, the sample was allowed to equilibrate for 5 minutes. FA titrations were conducted in triplicate, and each data point comprised of 60 readings taken over 115 s. A single replicate positive control of CPSF30 with the canonical RNA target (α-syn30 or α-syn24) was conducted in tandem with all titrations to ensure that the protein in use was fully active. Prior to data analysis, raw anisotropy values were corrected for changes in quantum yield of the fluorophore using the equation below.18

Where rc is the corrected anisotropy, r is the raw anisotropy, r0 is the anisotropy of the free fluorescently-labeled RNA, and rb is the anisotropy of the RNA-protein complex at saturation. Corrected anisotropy was plotted against protein concentration and analyzed using a cooperative binding model programmed into GraphPad Prism 5:

Where rtc is the total corrected anisotropy, [P] is the protein concentration, [P]1/2 is the protein concentration at which half of the protein ensemble is saturated, and h is the Hill coefficient.

Inductively coupled plasma mass spectrometry (ICP-MS).

ICP-MS was performed as previously described with the following exceptions.2, 18 Protein samples were diluted to 1 μM in 6% trace metal grade nitric acid to a final volume of 2 mL. An internal standard solution of Bi, Ge, Rh, and Sc was run in line through a mixing T to the nebulizer at an inner diameter of 1/10 of the sample line. All samples were run in He mode to avoid interference with argon oxide.

X-ray absorption spectroscopy (XAS).

CPSF30 samples were prepared in a 20 mM Tris, 50 mM NaCl, 30% glycerol, pH 7 buffer, with metal concentrations at ca 0.7 mM Fe and 2.0 mM Zn. Protein samples were loaded into prewrapped 2 mm Leucite XAS cells, flash frozen and then stored in liquid nitrogen until X-ray exposure. Fe and Zn k-edge XAS data were collected at the Stanford Synchrotron Radiation Lightsource (SSRL) on beamline 9-3, equipped with a Si[220] double crystal monochromator with an upstream mirror for X-ray focusing and harmonics rejection. Samples were maintained at 10 K using an Oxford Instruments continuous-flow liquid helium cryostat. Fluorescence spectra were collected using a Canberra 100 element germanium solid state detector. Solar slits and either a 3 μm Mn or 3 μm Cu (for Fe or Zn analysis respectively) were placed between the cryostat and detector to diminish random fluorescence scattering and remove low energy background signals. All XAS spectra were collected in 5 eV increments within the pre-edge region, 0.25 eV increments in the edge region. EXAFS data were collected in 0.05 Å−1 increments, out to k = 14 Å−1, integrated from 1 to 25 s in a k3-weighted manner during data collection. The total XAS scan length was ~40 min. Fe and Zn foil absorption spectra were simultaneously collected with each respective protein spectrum, for spectral calibration and the first inflection points energy was set at 7,111.2 eV for Fe and 9,659 eV for Zn.

XAS spectra were processed and analyzed using the EXAFSPAK program suite written for Macintosh OS-X44. EXAFSPAK is integrated with Feff v8 software45 for theoretical model generation. Normalized X-ray absorption near edge spectral (XANES) data for Fe data were subjected to pre-edge and edge analysis. Iron 1s→3d pre-edge peak analysis was completed following our established protocol46, and pre-edge peak areas were determined over the energy range of 7,110 – 7,116 eV. The iron oxidation state was deduced by comparing first inflection edge energies from Fe protein samples to our Fe(II) and Fe(III) model library47. In the extended X-ray absorption fine structural (EXAFS) region, data collected to k = 14 Å−1 corresponds to a spectral resolution of 0.12 Å−1 for all metal-ligand interactions47. As a result, only independent scattering environments at distances >0.12 Å were considered resolvable during fitting analysis. Data were fit using both single and multiple scattering amplitude and phase model functions to simulate iron and zinc metal-oxygen/nitrogen, -sulfur, and metal-metal interactions. During Fe data simulations, a scale factor (Sc) of 0.95 and threshold shift (ΔE0) values of −10 eV (Fe–O/N/C), −12 eV (Fe–S) and −15 eV (Fe–Fe) were used; for Zn simulations, a Sc of 0.9 and E0 values of −15.25 eV (Zn–O/N/C and Zn–S) were used. These calibration values were obtained from fitting crystallographically characterized small molecule Fe and Zn compounds46, 48, and these values were held constant during spectral simulations. The best-fit EXAFS simulation for each sample was based on the lowest mean square deviation value (F’)49, measured between data and simulated spectra, corrected for the number of degrees of freedom in the simulation, and using an acceptable Debye-Waller value (between 0.0001 and 0.006 Å2) for each ligand environment.48 During simulations, only the bond length and Debye-Waller factor for each ligand environment were allowed to freely vary; coordination numbers were held constant but manually stepped incrementally at half integer values to help identify the optimal spectral simulation parameters.

Purification of apo-CPSF30-ZK.

A peptide corresponding to the c-terminal zinc knuckle domain of CPSF30 was purchased from Bio-Synthesis Incorporated (Lewisville, Texas) at ‘crude’ scale. The peptide sequence was QVTCYKCGEKGHYANRCTKG. This sequence length was modeled after other CCHC domains (nucleocapsid protein (NCp7), T4 gene protein 32, (gp32), and the nucleic acid binding protein encoded by the Drosophila Fw- element).50-53 For a typical experiment, 5 mg of the peptide stock was resuspended in ELGA PURELAB flex purified water and then incubated with 5 mM TCEP at room temperature for one hour. Following incubation, the peptide was purified using reverse-phase high-performance liquid chromatography (RP-HPLC) under non-metallic conditions (Waters 600 assembled with peak tubing and a Symmetry prep C18 7 μm column). A gradient beginning with 90% water containing 0.1% trifluoroacetic acid (TFA) mixed and 10% acetonitrile containing 0.1% TFA was utilized to separate the apo-CPSF30-ZK away from any contaminants, with apo-CPSF30-ZK eluting in a single peak at 80% water/0.1% TFA and 20% acetonitrile/0.1% TFA. Upon collection of apo-CPSF30-ZK, the peptide was transferred to an anaerobic chamber where it was lyophilized and stored in a solid form. Peptide mass was confirmed using MALDI-TOF mass spectrometry. All further peptide manipulations were completed anaerobically. All buffers were thoroughly degassed with argon prior to use. Cuvettes used for UV-visible spectroscopy were designed with screw-capped Teflon sealed lids for anaerobic work.

UV-Visible Co(II) titrations with apo-CPSF30-ZK.

For a typical titration, 100 μM of peptide was used. The titrations involved the addition of cobaltous chloride, in increments determined by molar equivalents. For apo-CPSF30-ZK titrations, CoCl2 additions were as follows: 0.1, 0.2, 0.3, 0.4, 0.5, 0.6, 0.8, 1, 2, 5, 10, and 20 equivalents as each titration point. Each set of titrations was carried out in triplicate. Co(II) coordination resulted in the appearance of d-d transition bands between 500 and 800 nm. The following maximum absorbance peaks were observed for Co(II)-CPSF30-ZK: 608 (shoulder), 645, and 700 nm. The data at 650 nm, where the d-d envelope maximum is observed, was plotted against the concentration of CoCl2 added. The data were then fit to a 1:1 binding equilibrium using Kaleidagraph software (Synergy software) and non-linear least squares analysis.

Where, [P] = apo-protein concentration.

Zinc binding to CPSF30-ZK.

The relative affinity of CPSF30-ZK for Zn(II) was determined by monitoring the displacement of Co(II) by Zn(II) following the method developed by Berg and Merkle.42-43, 54 The data were then fit to a competitive binding equilibrium.

Fluorescence anisotropy studies of Zn(II)-CPSF30-ZK.

The zinc knuckle’s ability to bind U-rich RNA was assessed utilizing a fluorescence anisotropy binding assay. Prior to FA binding studies, the active concentration of peptide was determined utilizing the extinction coefficient of CPSF30-ZK with excess cobalt at 650 nm. Peptide concentrations for FA were corrected for activity and stoichiometric amounts of zinc were added to the apo-peptide (between 100-500 μM) under anaerobic conditions forming the Zn-coordinated peptide. Zn(II)-CPSF30-ZK was titrated into 5 mm fluorometer quartz cuvettes containing 50 mM Tris, 100 mM NaCl, 0.3 mg/ml polycytidylic acid, 0.1 mg/ml BSA, and 5 nM 3’ 6-FAM labeled RNA. Both ARE11 and PolyU24 RNAs were evaluated. During each experiment, the solution was allowed to equilibrate for 5 minutes after titrating in peptide and mixing. FA measurements comprised of 60 readings over a total time of 115 seconds.

Molecular cloning, expression, and purification of CPSF30-F2F3.

A construct for CPSF30, named CPSF30-F2F3, which encodes for the second and third ZF domains of CPSF30, with the sequence of “AISGEKTVVCKHWLRGLCKKGDQCEFLHEYDMTKMPECYFYSKFGEC SNKECPFLHIDPESK” was overexpressed and purified. CPSF30-F2F3 was cloned into the pET-15b expression vector. BL21-DE3 competent E.coli cells (New England Biolabs) were then transformed with CPSF30-F2F3 via heat shock. The cells were grown in Lennox Luria Broth Base (LB) medium with 100 μg/mL ampicillin at 37 °C until mid-log phase (OD600 0.6-0.8) before being induced with 1 mM IPTG (isopropyl β-D-1-thiogalactopyranoside). After cultures were allowed to grow for 4 h post-induction, cells were harvested by centrifugation at 7800 x G for 15 min at 4 °C. Cell pellets were resuspended in 8 M urea, 10 mM MES at pH 5.0 with a Pierce EDTA-free protease and phosphatase inhibitor mini tablet (Thermo Scientific). The cells were lysed by sonication on ice, 1 mM of dithiothreitol (DTT) was added, and cells were centrifuged at 12,100 rpm for 15 min at 4 °C. The resulting supernatant was added to a SP Sepharose gravity column and incubated by rocking for 60 min at room temperature. A NaCl step gradient was used, ranging from 0 to 2 M, in 4 M urea, 10 mM MES at pH 5.0, with each wash containing 10 mM DTT. To prepare for further purification, 25 mM of DTT was added, and the solution was heated in a water bath at 56 °C for 2 h, followed by filtration (Millipore 0.22 μM Steriflip). The supernatant was then applied to a C18-reverse phase HPLC column (Symmetry 300 C18 Prep 5 μm, 19x150 mm Column) on an Agilent Technologies 1200 Series LC system and a water/acetonitrile (H2O/CH3CN, 0.1%trifluoroacetic acid (TFA)) gradient was applied. Purified CPSF30-F2F3 eluted at 28% CH3CN. The protein identity was confirmed via SDS-PAGE and MALDI-TOF mass spectrometry. Further handling of purified CPSF30-F2F3 was done anaerobically in a Coy anaerobic chamber (3% H2, 97% N2).

UV-Visible Co(II) and Zn(II) binding assays for apo-CPSF30-F2F3.

The affinity of CPSF30-F2F3 for cobalt and zinc was determined by spectrophotometrically monitoring the titration of apo-CPSF30-F2F3 with CoCl2 until saturation. The relative affinity for Zn(II) was determined by titrating Co-CPSF30-F2F3 with ZnCl2 and monitoring the displacement of Co(II) spectrophotometrically via the method of Berg and Merkle.54 The experiments were performed in 200 mM HEPES, 100 mM NaCl buffer at pH 7.5. Titrations were performed by titrating 0 to 20 equivalents (eq) of CoCl2 incrementally and then titrating ZnCl2 in a similar fashion.

Fluorescence anisotropy binding assays for CPSF30-F2F3.

Six 3’ 6-carboxyfluorescein (6-FAM)-labeled RNA oligonucleotides purchased from MilliporeSigma (HPLC purified grade) were utilized for these studies (Table 1). FA experiments were performed on an ISS k2 multifrequency phase fluorimeter with excitation wavelength at 495 nm and emission wavelength at 517 nm. The buffer system used was 200 mM HEPES, 50-100 mM NaCl, 0.05 mg/mL bovine serum albumin (BSA), at pH 7.5 and pH 8.0 using 5-10 nM of RNAs ARE11, AAU9, AAU12, AAU24, α-syn24 and α-syn30. Zn(II)-CPSF30-F2F3 was titrated into cuvettes containing the buffer system and the RNA, up to 1.2 μM of protein while the anisotropy was monitored.

Circular Dichroism (CD) studies for CPSF30-F2F3.

Circular Dichroism (CD) was utilized to assess the secondary structure of apo-CPSF30-F2F3 and Zn(II)-CPSF30-F2F3 on Jasco-810 spectropolarimeter. The CD spectra were scanned from 280 to 180 nm at a rate of 50 nm/min, with a bandwidth at 1 nm and sensitivity at 100 mdeg. Each spectrum shown represents an average of three accumulations. A 1 mm path length quartz cuvette was utilized, and the temperature was maintained at 25 °C. A 15.5 μM solution of apo-CPSF30-F2F3, made in 10 mM sodium phosphate buffer at pH 7.5, was scanned first. To the 15.5 μM solution of apo-CPSF30-F2F3, 2.0 equivalents of ZnCl2 was added to the cuvette and the CD spectrum obtained.

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

Full length CPSF30 contains both iron and zinc.

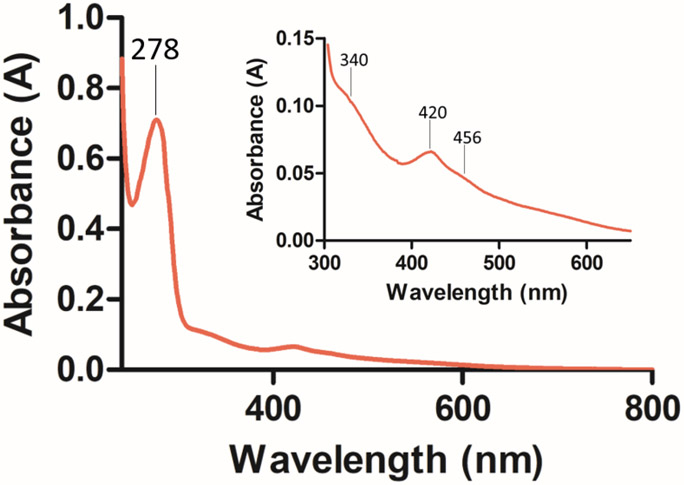

Full length CPSF30 contains a zinc knuckle domain with unknown function, in addition to five CCCH domains that we, and others, have previously shown are involved in binding to the PAS, AAUAAA.2, 18, 20, 32-33, 55 Zinc knuckle domains are often present in RNA binding proteins involved in viral replication (e.g. HIV nucleocapsid protein), and often recognize G/C and U rich sequence elements. 37 In addition to a conserved AAUAAA sequence, most pre-mRNAs contain a conserved poly uracil sequence. To determine the role of the zinc knuckle domain of CPSF30 in RNA binding and delineate whether it binds to poly uracil sequences, full length CPSF30 was over-expressed and purified. Like its five CCCH domain counterpart (CPSF30-5F), full length CPSF30 turned red upon over-expression, suggesting the presence of an iron co-factor.18 The UV-Visible spectrum of CPSF30 exhibits absorbance peaks at 420 and 456 nm, which are indicative of a 2Fe-2S cluster, and match those observed for the CPSF30-5F (Figure 2 (inset)).18 Metal occupancy was confirmed by utilizing inductively coupled plasma mass spectrometry (ICP-MS). The presence of both iron and zinc, ranging from 0.69-1.51 and 3.08-4.69 (min-max) equivalents respectively, suggests that the full-length protein contains a singular 2Fe-2S cluster and 5 zinc sites.

Figure 2.

UV-Vis spectrum of CPSF30-FL in 20 mM Tris, 100 mM NaCl, pH 8 between 240 – 800 nm with the maximum protein peak at 278 nm indicated. (Inset) Close up of spectrum between 300 – 650 nm with peak maxima indicated.

X-ray Absorption Spectroscopy (XAS) of the Iron and Zinc Sites:

XAS was used to characterize the iron-ligand metrical parameters in Fe and Zn-loaded on CPSF30. The iron k-edge XANES spectrum is shown in Figure 3 with an inset that displays the expanded 1s→3d pre-edge spectral signal. XANES data provides direct insight into the metal oxidation state, and the XANES pre-edge region provides insight into the metal-ligand bond symmetry and spin state for iron. The sharp/defined pre-edge spectral feature seen at 7112.8 eV in the Fe-CPSF30 XANES is characteristic of low spin iron existing in a tetrahedral ligand conformation. The pre-edge peak area, determined to be 0.051 eV2, is consistent with values we obtained for Fe-S cluster centers in several proteins.46 The excitation energy of the first inflection point in the Fe XANES, measured at 7122.22 eV, is consistent with an oxidized Fe(III)-S cluster.46 Simulations of the Fe EXAFS for CPSF30 (Figure 4) indicated a Fe-nearest neighbor coordination environment constructed by a 1.5 ± 1 oxygen/nitrogen ligands centered at a distance of 2.01 Å, and a second, more dominate, Fe-ligand environment of 2 ± 1 sulfur atoms centered at 2.27A. The appearance of a distinct Fe•••Fe ligand vector at 2.69 Å is characteristic of scattering observed for Fe-S clusters.46 Long range scattering is also observed for carbon atoms positioned at an average distance of 3.92 Å from the central iron (Table 2).

Figure 3: Normalized XANES spectra Fe/Zn-loaded CPSF30.

Left Panel: Fe-XANES spectrum, with 1s→3d pre-edge inset. Right Panel: Zn-XANES spectrum.

Figure 4. EXAFS and Fourier transforms (FT) of the EXAFS for Fe/Zn-loaded CPSF30.

Iron EXAFS, and FT of the EXAFS, for Fe/Zn-loaded CPSF30 are shown in panels A and B, respectively. Zinc EXAFS, and FT of the EXAFS, for Fe/Zn-loaded CPSF30 are shown in panels C and D, respectively. Best fit spectral simulations are shown in green.

Table 2.

Summary of the Fe and Zn EXAFS simulation results for Fe/Zn-loaded CPSF30.

| Nearest Neighbor Ligands a | Long Range Ligands b | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Metal | Atom c | R (Å)d | C.N e | σ2 f | Atom c | R (Å)d | C.N e | σ2 f | F’ g |

| Fe | O/N | 2.01 | 1.5 | 0.5 | Fe | 2.69 | 0.5 | 2.6 | 1.2 |

| S | 2.27 | 2.0 | 5.1 | C | 3.92 | 2.0 | 1.4 | ||

| Zn | O/N | 2.06 | 1.0 | 5.7 | C | 3.15 | 3.0 | 4.7 | 1.0 |

| S | 2.31 | 3.0 | 3.4 | C | 3.95 | 3.0 | 1.2 | ||

- Independent metal-ligand scattering environment.

- Scattering atoms: N (nitrogen), O (oxygen), C (carbon), S (sulfur).

- Average metal-ligand bond length.

- Average metal-ligand coordination number.

- Average Debye-Waller factor (Å2 x 103).

- Number of degrees of freedom weighted mean square deviation between data and fit.

XAS was further used to characterize the Zn-ligand metrical parameters for the Zn in the Fe/Zn-loaded CPSF30 sample. The first inflection point energy in the Zn XANES occurs at 9663 eV, consistent with Zn(II) metal. The excitation edge shows two distinct features in the peak maximum at 9665.2 eV and 9671.9 eV, characteristic for environments that include independent sulfur and oxygen/nitrogen ligand scattering, environments similar to those previously found in ZnN1S3 peptide XAS.56-57 The Zn EXAFS region was best simulated with 1 ± 1 Zn-O/N ligand at a distance of 2.06Å, and 3 ± 1 Zn-S atoms at an average distance of 2.31 Å. Two long-range carbon ligation environments were also observed at an average distance of 3.15 Å and 3.95 Å, respectively (Table 2). Collectively, the UV-visible, ICP-MS, and XAS data indicate that full length CPSF30 is a ‘zinc finger’ protein with a 2Fe-2S co-factor, with all metal sites binding to a 3Cys/1His ligand set from the protein.

RNA binding: full length CPSF30 binds to both poly uracil sequences and the polyadenylation signal (AAUAAA) in a cooperative manner.

With full length CPSF30 isolated, we sought to determine its RNA binding properties. CCCH domains typically bind to AU-rich RNA targets, and the five CCCH domain construct, CPSF30-5F, binds to the AAUAAA PAS hexamer; whereas, zinc knuckle domains bind to various RNA target sequences, with a preference for G/C and U rich targets.15, 34-37, 42-43 Most pre-mRNAs contain a polyU sequence, and there is some evidence from radiolabeled in vitro translation experiments that CPSF30 interacts with polyU sequences bound to sepharose resin.34 Because CPSF30 contains both CCCH and CCHC domains, we predicted that the protein would recognize both AU-rich and U-rich targets. To investigate this prediction, we determined the interaction of full length CPSF30 with AU-rich RNA and polyU-rich RNA via fluorescence anisotropy (FA). Our initial experiments focused on an AU-rich RNA sequence from alpha-synuclein, α-syn30 and α-syn24 (30 and 24 bases in length) that we had previously reported binds to the five ZF construct of CPSF30, CPSF30-5F.18 The titration of full length CPSF30 with either α-syn30 and α-syn24 resulted in a binding curve that was best fit to a cooperative binding model with a [P]1/2 of 109.5 ± 11.1 nM (Mean ± SEM) and 110.3 ± 14.0 nM and Hill coefficients of 2.3 and 2.1 for the 30 mer and 24 mer respectively. This affinity is slightly tighter than the affinity for the truncated 5 finger CPSF30 construct (CPSF30-5F) to α-syn30 ([P]1/2 of 177.6 ± 23.6 nM Hill coefficient: 1.8) (Figure 5). To determine if the binding observed for CPSF30-FL involves the AU hexamer, CPSF30-FL was titrated with a variant of the α-syn24 sequence in which that AU hexamer was modified to all cytosines (PolyC24) (Figure 5). No binding was observed, indicating that the AU-hexamer is required for binding of full length CPSF30 to pre-mRNA. We note that the same result was observed for the five finger CPSF30 construct, CPSF30-5F, suggesting that the CCCH domains are directly involved in binding to the AU hexamer.18

Figure 5.

(A) Sequences of alpha synuclein 30mer (α-syn30), alpha synuclein 24mer (α-syn24), and PolyC 24mer (PolyC24) RNAs. (B) Fluorescence anisotropy (FA) monitored binding of holo-CPSF30-FL to α-syn30 (orange squares), holo-CPSF30-FL to α-syn24 (purple triangles), holo-CPSF30-5F to α-syn30 (pink circles), and holo-CPSF30-FL to PolyC24 (green triangles). An average of three representative titrations are plotted and error is shown as standard error of the mean (SEM). Data are fit to a cooperative binding model.

We then sought to understand if the full length CPSF30 protein interacts with polyU sequences, via its zinc knuckle domain. In pre-mRNA, a U/GU – rich cis-acting downstream element (DSE) is located 35-45 nucleotides downstream of the PAS, and together, these elements aid in stimulating polyadenylation.58 Therefore a compelling hypothesis is that CPSF30 binds to both the PAS and the polyU sequence via its distinct CCCH and CCHC domains. To determine CPSF30’s RNA binding properties, an FA experiment of full length CPSF30 with a polyU sequence was performed. A titration of CPSF30 with polyU RNA resulted in a clear binding isotherm, with an affinity of 65.0 ± 3.0 nM and a Hill coefficient of 1.5 when fit to a cooperative binding equilibrium (Figure 6). Notably, the CPSF30 construct with only the five CCCH domains does not exhibit any affinity for the polyU sequence, revealing that the CCHC domain is required for this interaction. Together, these data reveal that full length CPSF30 directly binds to polyU RNA.

Figure 6.

(A) Sequences of alpha synuclein 30mer (α-syn30) and PolyU 24mer (PolyU24) RNA’s. (B) FA monitored binding of holo-CPSF30-5F and α-syn30 (blue circles) and holo-CPSF30-5F and PolyU24 (purple squares). (C) FA monitored binding of holo-CPSF30-FL and α-syn30 (blue circles) and holo-CPSF30-FL with PolyU24 (purple squares). An average of three representative titrations are plotted and error is shown as standard error of the mean (SEM). Data are fit to a cooperative binding model.

The zinc knuckle domain, CPSF30-ZK, binds Cobalt and Zinc, but not poly uracil RNA.

Our finding that the 5 CCCH domain construct of CPSF30 (CPSF30-5F) does not bind to poly uracil sequences, while the addition of a zinc knuckle domain (full length CPSF30) promotes high affinity binding to a poly uracil sequence suggested that the zinc knuckle domain itself might be sufficient for poly uracil binding. To test this hypothesis, we first had to obtain a construct of CPSF30 that contains just the zinc knuckle domain and folds around zinc. To this end, a 20 amino acid peptide that contains the CCHC ‘zinc knuckle’ sequence was synthesized and purified in the apo-form via reverse-phase HPLC. To verify that this construct binds zinc, a direct titration with Co(II) – as a spectroscopic probe for the spectroscopically silent (d10) Zn(II) - was performed. The resultant Co(II)-CPSF30-ZK spectrum, shown in Figure 7A, exhibits d-d bands centered at 650 and 700 nm indicative of a CCHC ligand set and closely resembling the cobalt spectra reported for the CCHC domains encoded within the Drosophila melanogaster Fw transposable element.52 An upper limit Kd of 3.08 (± 0.12) x 10−7 M was determined by fitting the data to a 1:1 binding equilibrium (Figure 7B). Typically ZFs have a dissociation constant for Co(II) ions in the low micromolar to high nanomolar regime, therefore the affinity measured here for Co binding to the CPSF30-ZK fits within the values reported for other ZFs.15, 59 The calculated molar absorptivity of apo-CPSF30-ZK for Co(II) was 562 (± 34) M−1 cm−1. ZFs typically have a molar absorptivity of 400-600 M−1 cm−1 for each tetrahedrally coordinated Co(II) center; therefore, the data obtained for the Co(II)-CPSF30-ZK construct is consistent with a tetrahedral site.15, 54, 60-61

Figure 7.

(A) Plot of the change in absorption as apo-CPSF30-ZK is titrated with CoCl2. Experiment was conducted in 200 mM MES buffer at a pH of 6.0. (B) Plot of the change in the absorption spectrum at 650 nm as a function of concentration as Co(II) is added to apo-CPSF30-ZK. The data were fit to yield an upper limit dissociation constant, Kd, of 3.08 (± 0.12) x 10−7 M. The solid line represents a nonlinear least-squares fit to a 1:1 binding model.

A competitive titration with Zn was then performed to verify that Zn(II) binds to CPSF30-ZK and to determine an upper limit Kd for Zn binding. As Zn(II) was titrated with Co(II)-CPSF30-ZK, a loss of the d-d transition bands were observed, due to the displacement of the bound Co(II) ions with Zn(II).54 These data were fit to a competitive binding equilibrium, and an upper limit dissociation constant for Zn(II) coordination to CPSF30-ZK of 9.40 (± 0.17) x 10−14 M was determined (Figure S1). This affinity is consistent with the affinities of zinc for other CCHC domains.51-52

To determine if Zn(II)-CPSF30-ZK binds to poly uracil RNA, Zn(II)-CPSF-ZK was titrated with fluorescently labeled U-rich RNA of lengths varying from 11 to 24 nucleotides, and the fluorescence anisotropy was monitored. No change in anisotropy was observed for any of the RNA strands investigated (Figure S2). Typically, ZFs bind to target RNA or DNA with at least two domains to achieve sub micromolar affinity, therefore it is perhaps not surprising that a single ZF domain does not bind to RNA.62-63 These data, in conjunction with the full length CPSF30 data, reveal that the zinc knuckle domain of CPSF30 is necessary, but not sufficient for binding to the poly U sequence.

Determination of the ZF2 and ZF3 domains in CPSF30/PAS Binding.

CPSF30 contains 5 CCCH domains, and our solution-based RNA binding studies have shown that high affinity binding to the AAUAAA PAS sequence occurs when the 5 CCCH domains are present. However, CCCH ZFs often require only two domains to bind to AU-rich RNA targets. For instance, TTP binds to an AU-rich RNA target with just two CCCH domains.42-43, 62, 64 Additionally, in the reported cryo-EM structures of the CPSF complex (CPSF30, CPSF160, WDR33) with short RNA sequences (AACCUCCAAUAAACAAC and ACAAUAAAGG respectively), the second and third ZF domains interact specifically with A1/A2 and A4/A5 within the AAUAAA PAS sequence.32-33 Collectively, these data suggest that a construct of ZF2 and ZF3 may be sufficient for RNA binding to the PAS sequence and that residues 1, 2, 4, and 5 within the PAS hexamer are critical for RNA binding.

To determine if ZF2 and ZF3 together are sufficient for RNA binding to the PAS, a construct of CPSF30 containing only ZF2 and ZF3 was over-expressed and purified. To verify that the CPSF30-F2F3 construct binds zinc, Co(II) was used as a spectroscopic probe for zinc, as previously reported for other ZFs.1, 63 As shown in Figure 8A, as apo-CPSF30-F2F3 is titrated with Co(II), d-d transition bands centered at 615, 650, and 678 nm appear, indicative of tetrahedral coordination. An upper limit Kd of 2.01 (± 1.08) x 10−6 M was determined by fitting the data to a 1:1 binding model (Figure 8B). The transition bands and dissociation constant for Co(II) ions are consistent with reported values for other CCCH domains.1, 42

Figure 8.

(A) Plot of the change in absorption as apo-CPSF30-F2F3 is titrated with CoCl2. The experiment was performed in 200mM HEPES buffer, 100 mM NaCl at a pH of 7.5. (B) Plot of the change in absorption spectrum at 650 nm as a function of concentration as cobalt(II) is added to apo-CPSF30-F2F3. The data were fit to yield an upper limit dissociation constant, Kd, of 2.01 (± 1.08) x 10−6 M. The solid line represents a nonlinear least-squares fit to a 1:1 binding model.

A competitive titration with zinc was then performed to determine if Zn(II) binds the two finger construct, CPSF30-F2F3. By titrating Co(II)-CPSF30-F2F3 with Zn(II), the Co(II) absorbance peaks decreased, indicating that the bound Co(II) ions were being replaced with Zn(II) (Figure S3A). The data were fit to a competitive binding model, and an upper limit Kd of 3.38 (± 2.49) x 10−13 M was determined for Zn(II)-CPSF30-F2F3 (Figure S3B). This affinity is consistent with the affinities reported for zinc binding to other CCCH domains.1, 42 The CD spectra of apo-CPSF30-F2F3 and Zn(II)-CPSF30-F2F3 were also obtained, Figure S4, and distinct structural changes were observed upon Zn(II) coordination indicating folding. The CD spectrum of Zn(II)-CPSF30-F2F3 is similar to that obtained for Zn(II)-TTP-2D, a CCCH zinc finger that contains two CCCH domains.42

To investigate if Zn(II)-CPSF30-F2F3 is sufficient to bind to the AU-hexamer sequence, Zn(II)-CPSF30-F2F3 was titrated with six fluorescently labeled RNA targets containing AU-hexamer sequences. These RNA oligomers ranged in length from 9-30 bases (Figure S5). To our surprise, none of the six RNAs investigated (AAU9, AAU12, AAU24, ARE11, α-syn24, α-syn30) exhibited any binding to Zn(II)-CPSF30-F2F3, suggesting that the F2F3 construct of CPF30 is not sufficient for RNA binding and other regions of the protein – perhaps other ZF domains or an Fe-S cluster cofactor are required for RNA binding.

Role of the PAS RNA sequence in CPSF30 5 finger and full-length RNA binding.

To determine the effects of residues 1, 2, 4, and 5 within the PAS sequence (AAUAAA) on CPSF30/RNA binding, CPSF30-5F and full length CPSF30 were titrated with an alpha-synuclein pre-mRNA in which the adenines 1, 2, 4, and 5 within the PAS sequence were mutated to cytosines (ΔA1,2,4,5). The prediction was that these adenines are critical for CPSF30/RNA binding, and the mutation would abrogate binding. This prediction was borne out for CPSF30-5F which did not exhibit any binding to the mutated PAS sequence. In contrast, full length CPSF30 still bound to the mutated RNA sequence, albeit with diminished affinity (~2.5 times weaker - [P]1/2 = 275.1 ± 37.3 nM; Hill coefficient =1.4), as shown in Figure 9. The mutated alpha-synuclein pre-mRNA still contains a U-rich sequence at the 5’ end, and therefore because full length can bind to poly U RNA, this result further supports the role of the ZK in polyU binding.

Figure 9.

(A) Sequences of Alpha synuclein 30mer (α-syn30) and quadruple mutant 24mer (ΔA1,2,4,5) RNA’s. (B) FA monitored binding of holo-CPSF30-5F and α-syn30 (blue circles) and holo-CPSF30-5F and ΔA1,2,4,5 (yellow triangles) (C) FA monitored binding of holo-CPSF30-FL and α-syn30 (blue circles) and holo-CPSF30-FL with ΔA1,2,4,5 (yellow triangles). An average of three representative titrations are plotted and error is shown as standard error of the mean (SEM). Data are fit to a cooperative binding model.

CONCLUSIONS

Collectively, these studies reveal that full length CSPF30 is an iron-sulfur and zinc co-factored protein that recognizes two conserved pre-mRNA sequences - AAUAAA (the polyadenylation signal (PAS)) and U-rich RNA – in a metal dependent, cooperative manner. While we do not yet know the order of binding, based upon these results a preliminary mechanism is shown in Figure 10, whereby the CCCH domains recognize the AAUAAA sequence and the CCHC zinc knuckle domain, in conjunction with the CCCH domain, recognize the poly-uracil sequence. Notably, only CPSF30 proteins in higher eukaryotes contain CCHC domains within their sequences, suggesting that CPSF30 may have evolved to recognize two types of RNA targets in higher order eukaryotes by connecting different types of ‘zinc finger’ domains.34, 65 These studies elaborate the role of CPSF30 alone, and contribute to our understanding of the larger CPSF complex, for which RNA binding interactions are not well understood. Studies to structurally characterize the CPSF30/RNA complex to tease out the functional roles of the individual CCCH and CCHC domains are in progress.

Figure 10.

Preliminary RNA binding mechanism of full length CPSF30 binding pre-mRNA.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

SLJM is grateful for the NSF (CHE-1708732) for support of this work, TLM acknowledges the NIH, (DK068139) and JDP acknowledges a CBI training grant (GM066706) and the AFPE for partial support.

Footnotes

Supporting Information

Figures S1-S5 (zinc titration with Co(II)-CPSF30-ZK, FA binding assay of Zn(II)-CPSF30-ZK to RNA, zinc titration of Co(II)-CPSF30-F2F3, FA binding assay of Zn(II)-CPSF30-F2F3 to RNA, CD spectroscopy of CPSF30-F2F3) are available free of charge via the internet at http://pubs.acs.org.

ACCESSION CODES

CPSF30: UniProt- O19137

REFERENCES

- 1.Kluska K, Adamczyk J, Krężel A (2018) Metal binding properties, stability and reactivity of zinc fingers, Coord. Chem. Rev 367, 18–64. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Shimberg GD, Pritts JD, Michel SLJ (2018) Iron-Sulfur Clusters in Zinc Finger Proteins, Methods Enzymol. 599, 101–137. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Jantz D, Amann BT, Gatto GJ, Berg JM (2004) The Design of Functional DNA-Binding Proteins Based on Zinc Finger Domains, Chem. Rev 104, 789–800. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lee SJ, Michel SLJ (2014) Structural Metal Sites in Nonclassical Zinc Finger Proteins Involved in Transcriptional and Translational Regulation, Acc. Chem. Res 47, 2643–2650. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Maret W (2012) New perspectives of zinc coordination environments in proteins, J. Inorg. Biochem 111, 110–116. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Miller J, McLachlan AD, Klug A (1985) Repetitive zinc-binding domains in the protein transcription factor IIIA from Xenopus oocytes, EMBO J. 4, 1609–1614. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Laity JH, Lee BM, Wright PE (2001) Zinc finger proteins: new insights into structural and functional diversity, Curr. Opin. Struct. Biol 11, 39–46. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Searles MA, Lu D, Klug A (2000) The role of the central zinc fingers of transcription factor IIIA in binding to 5 S RNA, J. Mol. Biol 301, 47–60. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Klug A (2010) The Discovery of Zinc Fingers and Their Applications in Gene Regulation and Genome Manipulation, Annu. Rev. Biochem 79, 213–231. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Andreini C, Banci L, Bertini I, Rosato A (2006) Zinc through the Three Domains of Life, J. Proteome Res 5, 3173–3178. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Andreini C, Banci L, Bertini I, Rosato A (2006) Counting the zinc-proteins encoded in the human genome, J. Proteome Res 5, 196–201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Bertini I, Decaria L, Rosato A (2010) The annotation of full zinc proteomes, J. Biol. Inorg. Chem 15, 1071–1078. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Krishna SS, Majumdar I, Grishin NV (2003) Structural classification of zinc fingers, Nucleic Acids Res. 31, 532–550. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Matthews JM, Sunde M (2002) Zinc Fingers--Folds for Many Occasions, IUBMB Life 54, 351–355. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Michalek JL, Besold AN, Michel SL (2011) Cysteine and histidine shuffling: mixing and matching cysteine and histidine residues in zinc finger proteins to afford different folds and function, Dalton Trans. 40, 12619–12632. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Fu M, Blackshear PJ (2017) RNA-binding proteins in immune regulation: a focus on CCCH zinc finger proteins, Nat. Rev. Immunol 17, 130–143. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Maeda K, Akira S (2017) Regulation of mRNA stability by CCCH-type zinc-finger proteins in immune cells, Int. Immunol 29, 149–155. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Shimberg GD, Michalek JL, Oluyadi AA, Rodrigues AV, Zucconi BE, Neu HM, Ghosh S, Sureschandra K, Wilson GM, Stemmler TL, Michel SLJ (2016) Cleavage and polyadenylation specificity factor 30: An RNA-binding zinc-finger protein with an unexpected 2Fe–2S cluster, Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A 113, 4700–4705. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Yang Q, Doublié S (2011) Structural biology of poly(A) site definition, Wiley Interdiscip. Rev.: RNA 2, 732–747. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Chan SL, Huppertz I, Yao C, Weng L, Moresco JJ, Yates JR, Ule J, Manley JL, Shi Y (2014) CPSF30 and Wdr33 directly bind to AAUAAA in mammalian mRNA 3' processing, Genes Dev. 28, 2370–2380. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Proudfoot NJ (2011) Ending the message: poly(A) signals then and now, Genes Dev. 25, 1770–1782. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Chang JW, Yeh HS, Yong J (2017) Alternative Polyadenylation in Human Diseases, Endocrinol. Metab. (Seoul) 32, 413–421. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Thore S, Fribourg S, (2019) Structural insights into the 3'-end mRNA maturation machinery: Snapshot on polyadenylation signal recognition, Biochimie. 164, 105–110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Baxter EL, Jennings PA, Onuchic JN (2012) Strand swapping regulates the iron-sulfur cluster in the diabetes drug target mitoNEET, Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A 109, 1955–1960. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Conlan AR, Axelrod HL, Cohen AE, Abresch EC, Zuris J, Yee D, Nechushtai R, Jennings PA, Paddock ML (2009) Crystal Structure of Miner1: The Redox-active 2Fe-2S Protein Causative in Wolfram Syndrome 2, J. Mol. Biol 392, 143–153. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Tamir S, Paddock ML, Darash-Yahana-Baram M, Holt SH, Sohn YS, Agranat L, Michaeli D, Stofleth JT, Lipper CH, Morcos F, Cabantchik IZ, Onuchic JN, Jennings PA, Mittler R, Nechushtai R (2015) Structure–function analysis of NEET proteins uncovers their role as key regulators of iron and ROS homeostasis in health and disease, Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1853, 1294–1315. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Wiley SE, Paddock ML, Abresch EC, Gross L, van der Geer P, Nechushtai R, Murphy AN, Jennings PA, Dixon JE (2007) The Outer Mitochondrial Membrane Protein mitoNEET Contains a Novel Redox-active 2Fe-2S Cluster, J. Biol. Chem 282, 23745–23749. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Wiley SE, Murphy AN, Ross SA, van der Geer P, Dixon JE (2007) MitoNEET is an iron-containing outer mitochondrial membrane protein that regulates oxidative capacity, Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A 104, 5318–5323. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Lin J, Zhang L, Lai S, Ye K (2011) Structure and molecular evolution of CDGSH iron-sulfur domains, PLoS One 6, e24790. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Lipper CH, Karmi O, Sohn YS, Darash-Yahana M, Lammert H, Song L, Liu A, Mittler R, Nechushtai R, Onuchic JN, Jennings PA (2018) Structure of the human monomeric NEET protein MiNT and its role in regulating iron and reactive oxygen species in cancer cells, Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A 115, 272–277. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Cutone A, Howes BD, Miele AE, Miele R, Giorgi A, Battistoni A, Smulevich G, Musci G, di Patti MC (2016) Pichia pastoris Fep1 is a [2Fe-2S] protein with a Zn finger that displays an unusual oxygen-dependent role in cluster binding, Sci. Rep 6, 31872. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Sun Y, Zhang Y, Hamilton K, Manley JL, Shi Y, Walz T, Tong L (2018) Molecular basis for the recognition of the human AAUAAA polyadenylation signal, Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A 115, E1419–E1428. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Clerici M, Faini M, Muckenfuss LM, Aebersold R, Jinek M (2018) Structural basis of AAUAAA polyadenylation signal recognition by the human CPSF complex, Nat. Struct. Mol. Biol 25, 135–138. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Barabino SM, Hubner W, Jenny A, Minvielle-Sebastia L, Keller W (1997) The 30-kD subunit of mammalian cleavage and polyadenylation specificity factor and its yeast homolog are RNA-binding zinc finger proteins, Genes Dev. 11, 1703–1716. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.D'Souza V, Summers MF (2004) Structural basis for packaging the dimeric genome of Moloney murine leukaemia virus, Nature 431, 586–590. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Benhalevy D, Gupta SK, Danan CH, Ghosal S, Sun HW, Kazemier HG, Paeschke K, Hafner M, Juranek SA (2017) The Human CCHC-type Zinc Finger Nucleic Acid-Binding Protein Binds G-Rich Elements in Target mRNA Coding Sequences and Promotes Translation, Cell Rep. 18, 2979–2990. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Schuler W, Dong C, Wecker K, Roques BP (1999) NMR structure of the complex between the zinc finger protein NCp10 of Moloney murine leukemia virus and the single-stranded pentanucleotide d(ACGCC): comparison with HIV-NCp7 complexes, Biochemistry 38, 12984–12994. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Tian B, Graber JH (2012) Signals for pre-mRNA cleavage and polyadenylation, Wiley Interdiscip. Rev.: RNA 3, 385–396. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.McDevitt MA, Hart RP, Wong WW, Nevins JR (1986) Sequences capable of restoring poly(A) site function define two distinct downstream elements, EMBO J. 5, 2907–2913. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Gil A, Proudfoot NJ (1987) Position-dependent sequence elements downstream of AAUAAA are required for efficient rabbit beta-globin mRNA 3' end formation, Cell 49, 399–406. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Levitt N, Briggs D, Gil A, Proudfoot NJ (1989) Definition of an efficient synthetic poly(A) site, Genes Dev. 3, 1019–1025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.diTargiani RC, Lee SJ, Wassink S, Michel SL (2006) Functional characterization of iron-substituted tristetraprolin-2D (TTP-2D, NUP475-2D): RNA binding affinity and selectivity, Biochemistry 45, 13641–13649. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Shimberg GD, Ok K, Neu HM, Splan KE, Michel SLJ (2017) Cu(I) Disrupts the Structure and Function of the Nonclassical Zinc Finger Protein Tristetraprolin (TTP), Inorg. Chem 56, 6838–6848. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.George GN, George SJ, Bommannavar ASE EXAFSPAK. http://ssrl.slac.stanford.edu/exafspak.html. [Google Scholar]

- 45.Ankudinov AL, Rehr JJ (1997) Relativistic calculations of spin-dependent x-ray-absorption spectra, Phys. Rev. B 56, R1712–R1716. [Google Scholar]

- 46.Cook JD, Kondapalli KC, Rawat S, Childs WC, Murugesan Y, Dancis A, Stemmler TL (2010) Molecular details of the yeast frataxin-Isu1 interaction during mitochondrial Fe-S cluster assembly, Biochemistry 49, 8756–8765. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Bencze K, Kondapalli K, Stemmler T (2007) X-ray absorption spectroscopy, in Applications of Physical Methods to Inorganic and Bioinorganic Chemistry (Scott R, Lukehart C, Ed.), pp 513–528. Wiley, Chichester, UK. [Google Scholar]

- 48.Cotelesage JJ, Pushie MJ, Grochulski P, Pickering IJ, George GN (2012) Metalloprotein active site structure determination: synergy between X-ray absorption spectroscopy and X-ray crystallography, J. Inorg. Biochem 115, 127–137. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Riggs-Gelasco PJ, Stemmler TL, Penner-Hahn JE (1995) XAFS of dinuclear metal sites in proteins and model compounds, Coord. Chem. Rev 144, 245–286. [Google Scholar]

- 50.Mely Y, De Rocquigny H, Morellet N, Roques BP, Gerad D (1996) Zinc binding to the HIV-1 nucleocapsid protein: a thermodynamic investigation by fluorescence spectroscopy, Biochemistry 35, 5175–5182. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Guo J, Giedroc DP (1997) Zinc site redesign in T4 gene 32 protein: structure and stability of cobalt(II) complexes formed by wild-type and metal ligand substitution mutants, Biochemistry 36, 730–742. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Bavoso A, Ostuni A, Battistuzzi G, Menabue L, Saladini M, Sola M (1998) Metal ion binding to a zinc finger peptide containing the Cys-X2-Cys-X4-His-X4-Cys domain of a nucleic acid binding protein encoded by the Drosophila Fw-element, Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun 242, 385–389. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Abbehausen C, Peterson EJ, de Paiva RE, Corbi PP, Formiga AL, Qu Y, Farrell NP (2013) Gold(I)-phosphine-N-heterocycles: biological activity and specific (ligand) interactions on the C-terminal HIVNCp7 zinc finger, Inorg. Chem 52, 11280–11287. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Berg JM, Merkle DL (1989) On the metal ion specificity of zinc finger proteins, J. Am. Chem. Soc 111, 3759–3761. [Google Scholar]

- 55.Clerici M, Faini M, Aebersold R, Jinek M (2017) Structural insights into the assembly and polyA signal recognition mechanism of the human CPSF complex, eLife 6, E33111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Herbst RW, Perovic I, Martin-Diaconescu V, O'Brien K, Chivers PT, Pochapsky SS, Pochapsky TC, Maroney MJ (2010) Communication between the zinc and nickel sites in dimeric HypA: metal recognition and pH sensing, J. Am. Chem. Soc 132, 10338–10351. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Clark-Baldwin K, Tierney DL, Govindaswamy N, Gruff ES, Kim C, Berg J, Koch SA, Penner-Hahn JE (1998) The Limitations of X-ray Absorption Spectroscopy for Determining the Structure of Zinc Sites in Proteins. When Is a Tetrathiolate Not a Tetrathiolate?, J. Am. Chem. Soc 120, 8401–8409. [Google Scholar]

- 58.Hollerer I, Grund K, Hentze MW, Kulozik AE (2014) mRNA 3'end processing: A tale of the tail reaches the clinic, EMBO Mol. Med 6, 16–26. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Magyar JS, Godwin HA (2003) Spectropotentiometric analysis of metal binding to structural zinc-binding sites: accounting quantitatively for pH and metal ion buffering effects, Anal. Biochem 320, 39–54. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.MacColl R, Eisele LE, Stack RF, Hauer C, Vakharia DD, Benno A, Kelly WC, Mizejewski GJ (2001) Interrelationships among biological activity, disulfide bonds, secondary structure, and metal ion binding for a chemically synthesized 34-amino-acid peptide derived from alpha-fetoprotein, Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1528, 127–134. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Krizek BA, Merkle DL, Berg JM (1993) Ligand variation and metal ion binding specificity in zinc finger peptides, Inorg. Chem 32, 937–940. [Google Scholar]

- 62.Lai WS, Carballo E, Strum JR, Kennington EA, Phillips RS, Blackshear PJ (1999) Evidence that tristetraprolin binds to AU-rich elements and promotes the deadenylation and destabilization of tumor necrosis factor alpha mRNA, Mol. Cell Biol 19, 4311–4323. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Michel SL, Guerrerio AL, Berg JM (2003) Selective RNA binding by a single CCCH zinc-binding domain from Nup475 (Tristetraprolin), Biochemistry 42, 4626–4630. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Brewer BY, Malicka J, Blackshear PJ, Wilson GM (2004) RNA sequence elements required for high affinity binding by the zinc finger domain of tristetraprolin: conformational changes coupled to the bipartite nature of Au-rich MRNA-destabilizing motifs, J. Biol. Chem 279, 27870–27877. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Chakrabarti M, Hunt AG (2015) CPSF30 at the Interface of Alternative Polyadenylation and Cellular Signaling in Plants, Biomolecules 5, 1151–1168. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.