Abstract

Adult onset leukoencephalopathy with axonal spheroids and pigmented glia (ALSP) is a dementia resulting from dominantly inherited CSF1R inactivating mutations. The Csf1r+/− mouse mimics ALSP symptoms and pathology. Csf1r is mainly expressed in microglia, but also in cortical layer V neurons that are gradually lost in Csf1r+/− mice with age. We therefore examined whether microglial or neuronal Csf1r loss caused neurodegeneration in Csf1r+/− mice. The behavioral deficits, pathologies and elevation of Csf2 expression contributing to disease, previously described in the Csf1r+/− ALSP mouse, were reproduced by microglial deletion (MCsf1rhet mice), but not by neural deletion. Furthermore, increased Csf2 expression by callosal astrocytes, oligodendrocytes, and microglia was observed in Csf1r+/− mice and, in MCsf1rhet mice, the densities of these three cell types were increased in supraventricular patches displaying activated microglia, an early site of disease pathology. These data confirm that ALSP is a primary microgliopathy and inform future therapeutic and experimental approaches.

Keywords: adult onset leukoencephalopathy with axonal spheroids and pigmented glia (ALSP), axonal pathology, colony stimulating factor-1 receptor (CSF-1R), Csf2 expression, demyelination, GM-CSF, microgliopathy

1 |. INTRODUCTION

The colony stimulating factor-1 receptor (CSF-1R) is expressed on microglia (Hao, Guilbert, & Fedoroff, 1990; Raivich, Gehrmann, Moreno-Floros, & Kreutzberg, 1993; Sawada, Suzumura, Yamamoto, & Marunouchi, 1990), neural progenitor cells, and subpopulations of neuronal cells (Clare, Day, Empson, & Hughes, 2018; Luo et al., 2013; Nandi et al., 2012; Wang, Berezovska, & Fedoroff, 1999) (reviewed in (Chitu, Gokhan, Nandi, Mehler, & Stanley, 2016)). Adult leukoencephalopathy with axonal spheroids and pigmented glia (ALSP) is a neurodegenerative disease caused by dominantly inherited mutations in the CSF1R gene (Rademakers et al., 2011) (reviewed in (Konno, Kasanuki, Ikeuchi, Dickson, & Wszolek, 2018)). Previous immunohistochemical studies (Hoffmann et al., 2014; Konno et al., 2014) have shown that microglia in ALSP brains express lower CSF-1R levels than in control brains. In Csf1r+/− mice, that mimic human ALSP patients, cognitive impairment and olfactory deficits are apparent at 7 months, followed by the development of sensorimotor and emotional deficits (Chitu et al., 2015; Chitu et al., 2020). Young, disease-free, Csf1r+/− mice exhibit microgliosis coupled with elevated expression of the microglial mitogen, CSF-2 (Chitu et al., 2015), also known as granulocyte-macrophage CSF and in aged mice, the microgliosis is accompanied by the CSF-2-dependent elevation of microglial markers of oxidative stress and demyelination (Chitu et al., 2020). Furthermore, cerebral CSF-1 is elevated in patients and monoallelic Csf2 deletion in Csf1r+/− mice prevents the development of most symptoms of disease in aged mice (Chitu et al., 2020), suggesting that microglial expansion and activation by CSF-2 plays an important role in disease. However, cortical layer V neurons, a subpopulation of which express the CSF-1R (Chitu et al., 2015; Clare et al., 2018), become significantly reduced in Csf1r+/− mice by 21 months of age, following a transient elevation in number at 3 months (Chitu et al., 2015). Monallelic deletion of Csf2 does not improve this phenotype, suggesting that their loss might be due to a failure of direct regulation of neuronal survival via the CSF-1R. Thus, ALSP could be caused by dysregulation of CSF-1R signaling in the microglial lineage, the neuronal lineage, or both.

To address the contribution of Csf1r heterozygosity in the microglial and neuronal lineages to ALSP development in mice, we have studied disease development in Csf1rfl/+;Cx3cr1Cre/+, and Csf1rfl/+; Nestin-Cre/+ mice, in which one allele of Csf1r is deleted from the microglial and neural lineages, respectively. We show that microglial Csf1r heterozygosity is sufficient to reproduce all aspects of the neurodegenerative disease of the ALSP mouse model. These results encourage the development of novel and effective treatments for ALSP aimed at modulating microglia function or at replacing mutant with wild type microglia. They also prompt investigation of the causal role of microglial activation in other neurodegenerative diseases.

2 |. MATERIALS AND METHODS

2.1 |. Ethics statement

All in vivo experiments were conducted in accordance with the National Institutes of Health regulations on the care and use of experimental animals and approved by the Albert Einstein College of Medicine Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee.

2.2 |. Mouse strains, breeding, and maintenance

The generation, maintenance, and genotyping of Csf1r+/− mice were described previously (Chitu et al., 2015; Dai et al., 2002). Csf1rfl/+ mice (Li, Chen, Zhu, & Pollard, 2006), a gift of Dr J. W. Pollard, College of Medicine and Veterinary Medicine, Queen’s Medical Research Institute, University of Edinburgh, Edinburgh, UK, were genotyped as described. Cx3Cr1Cre/+ mice (Yona et al., 2013) were a gift from Dr Marco Prinz, Institute of Neuropathology, Freiburg University Medical Centre, Freiburg, Germany and genotyped as described (Goldmann et al., 2013). Nestin-Cre/+ mice (Tronche et al., 1999) were purchased from the Jackson Laboratories and genotyped as described. All lines were on or backcrossed for more than 10 generations onto the C57BL6/J background. Cohorts were developed from the progeny of matings of Csf1r+/− to Csf1r+/+ mice, Cx3Cr1Cre/+ to Csf1rfl/+ mice and Nestin-Cre/+ to Csf1rfl/+ mice, randomized with respect to the litter of origin. At 3 months of age, they were transferred from a breeder diet (PicoLab Rodent Diet 20 5058) to a lower fat maintenance diet (PicoLab Rodent Diet 20 5053). This prevented the increase in body weight in Csf1r+/− mice compared with wild-type mice observed in an earlier study (Chitu et al., 2015) and was also associated with delayed onset of several deficits and absence of motor impairment in male Csf1r+/− mice (Chitu et al., 2020). The sex and age of mice used in the experiments is reported in each figure.

2.3 |. Behavioral studies

Mice were assessed for cognition, anxiety, and motor coordination in a longitudinal battery of experiments. The behavioral studies included both females and males and were carried out by blinded experimenters. On each testing day, animals were moved to a behavioral room and allowed to acclimate for 1 hr prior to the start of the experiment. The experiments were conducted during the light cycle. To minimize the confounding effect of other factors, the study was randomized and balanced for time (morning vs. afternoon), and the two genders were tested separately.

2.3.1 |. Cognitive assessment

Y-maze

Mice were tested for spatial short-term memory at the age of 13.5 months in the two-trial test version of the Y-maze (Biundo, Ishiwari, Del Prete, & D’Adamio, 2016). The Y-maze consists of three white plastic arms of equal size (35 cm × 5 cm × 10 cm). The apparatus was placed under a 40 lx-intense light surrounded by distal visual cues. The test consisted of two stages, training and testing. During the training stage, one of the arms (novel) was closed, and each mouse was allowed to explore the remaining two arms (known arms) for 10 min. After an interval of 1 hr, the novel arm was opened, and the same mouse was returned into the apparatus, and was allowed to explore all the three arms for 5 min. The positions of the novel and known arms were counterbalanced within each genotype to reduce confounding preference effects. The number of entries into the arms was recorded by ANY-maze video tracking system (ANY-maze, Stoelting).

Morris water maze

The experimental groups were tested in the Morris water maze (MWM) for spatial learning and reference memory at the age of 14 months. The MWM consists of a circular tank (120 cm of diameter) filled with opaque water (~20°C), and divided in four quadrants (NW, SW, NE, SE). Mice were first tested in the visual task for visual and motor deficits. During this stage, mice were given three daily sessions to locate a visible platform. The platform was placed at the center of a quadrant, and its location was randomly changed between trials to ensure that a proximal cue (a flag attached to the center of the platform) was used to reach the platform.

During the acquisition phase of the MWM, mice received four daily trials to locate a hidden platform submerged 1 cm under the water and placed in one of the quadrants for all the duration of the test. Each mouse was given 60 s to reach the platform. Distal visual cues hung around the tank were provided as referential tools to locate the hidden platform. Two days after the last trial, mice were tested for retention memory in a single trial (probe trial) during which the platform was removed from the tank. The number of crossings into the area where the platform had been located prior to its removal was used as measure of long-term memory. The distance covered to reach the platform and the number of crossings into the platform area were tracked by ANY-maze video tracking system.

Contextual fear conditioning

The contextual fear conditioning (CFC) test was used as test of associative learning and long-term memory (Biundo, Del Prete, Zhang, Arancio, & D’Adamio, 2018). Mice were tested in the CFC at the age of 16 months. The apparatus consists of a conditioning chamber (18 cm × 20 cm × 28 cm) enclosed within a sound-attenuating cubicle (Coulbourn Instruments, Whitehall, PA). The conditioning chamber included a metallic grid floor connected to a shock releaser and to a sound amplifier (Coulbourn Instruments) and equipped with a single house light. On the first day (training), mice were given a single foot shock (0.6 mA, 2 s) coupled with a conditioned stimulus (a tone of 2.8 kHz, 85 dB). One day after (testing), mice were returned to the conditioning chamber and the percentage of freezing was recorded by a tracking software (FreezeFrame 4, Actimetrics).

Behavioral spectrometer

Mice were assessed in the behavioral spectrometer for general locomotion (running, walking, trotting, still), and for other classes of behavior phenotypes including rearing, pain-related behaviors (shimmy and writhe), orientation and risk assessment (Brodkin et al., 2014). The Behavioral Spectrometer (Behavioral Instruments, NJ) consists of a 40 cm by 40 cm square arena enclosed at a height of 45 cm. The apparatus is equipped with a removable floor made of an aluminum honeycomb sheet placed on three vibration sensors. A miniature color CCD camera is mounted in the ceiling above the center of the arena. A row of 32 infrared transmitter and receiver pairs is embedded in the walls at a height of 6.5 cm. Mice were tracked by Viewer Software (BIObserve). The track length in the center of the arena reported in this study was used as a measure inversely related to anxiety.

Elevated zero maze

Mice were tested for anxiety in the elevated zero maze (Stoelting, Wood Dale, IL) at the age of 16 months. The apparatus consisted of a 50 cm-elevated annular maze (diameter 50 cm, width 5 cm) including two opposite open zones, and two opposite closed zones. The closed zones were delimited by two 15-cm-high walls. Each mouse was placed into one of the closed arms and allowed to freely explore the elevated zero maze for 5 min. The time spent in the open zone was recorded by ANY-maze video tracking system (Any-maze, Stoelting), and used as a measure inversely related to anxiety.

Balance beam

Motor coordination was assessed in the balance beam test (Gulinello, Chen, & Dobrenis, 2008). In brief, each mouse was placed at one end of a wooden beam (1.6 cm in diameter, 1 m long) elevated 50 cm above the floor and allowed to reach the other end of the beam. The number of slips made while crossing the beam was recorded by the experimenter and used as measure of locomotor coordination.

2.4 |. Ultrastructural studies

Callosal sections were obtained as described (Chitu et al., 2020). In brief, mice were perfused with 30 ml of cold phosphate buffered saline (PBS) containing 10 U heparin/ml followed by 30 ml of 2% paraformaldehyde (PFA) in PBS. The brain was gently removed from the skull, dissected into 2 mm thick slices, and placed in cacodylate fixation buffer (2% PFA, 2.5% glutaraldehyde in 0.1 M cacodylate buffer, pH 7.4) for 40 min at room temperature. The corpus callosum was dissected, incubated overnight at 4°C in cacodylate fixation buffer, embedded, sectioned, stained, and examined by transmission electron microscopy using a JEOL 1200 EX transmission electron microscope. The G-ratio (ratio between the diameter of an axon and the diameter of a myelinated fiber) of ~100 fibers per mouse (two to three mice/genotype) was calculated using ImageJ software (Schindelin et al., 2012) (imagej.net). Cross sections (15 microscopic fields per mouse including ~3,000 fibers per mouse) were evaluated for the presence of age-related ultrastructural modifications according to the guidelines provided by Peters and Sethares (the fine structure of the aging brain [http://www.bu.edu/agingbrain]).

2.5 |. Immunostaining

Mice were intracardially perfused with 20 ml of a cold PBS solution containing 10 U heparin/ml, followed by 20 ml of cold 4% PFA in PBS. Brains were gently removed from the skulls, postfixed with 20 ml of cold 4% PFA solution overnight at 4°C, and dehydrated in a solution of 20% sucrose in PBS for 24 hr at 4°C. Brains were embedded in an OCT embedding medium (Fisher Scientific) and frozen by immersion in 2-methylbutanol at −40°C. Brain slices (30 μm thick) were obtained at the cryostat and stored at −20°C in cryoprotectant solution (30% ethylene glycol, 30% sucrose, in PBS, pH 7.4). Sections were washed three times for 5 min with 0.05% Triton X-100 in PBS (PBS-T) and incubated with antigen retrieval solution (10 mM sodium citrate, 0.05% Tween 20, pH 6.0) at 80°C for 20 min followed by rapid cooling at −20°C for 20 min. Sections were washed with 0.1% Triton X-100 in PBS and blocked with 10% donkey serum in PBS-T at RT for an hour. Sections were then incubated with primary antibodies overnight at 4°C. These include antibodies to ionized calcium binding adaptor molecule 1 (Iba1) (rabbit IgG; Wako Chemicals, Richmond, VA or goat IgG; Abcam, Cambridge, MA), cystatin F (rabbit IgG; Fisher, Pittsburgh, PA), poly(ADP-ribose) (mouse monoclonal, Millipore, Billerica, MA), NeuN (mouse monoclonal, Millipore, Danvers, MA), PECAM1 (BD Biosciences, San Jose, CA), GFAP (BD Biosciences). Following primary antibody incubation, sections were washed three times with PBS-T and incubated with secondary antibodies conjugated to either Alexa 488, Alexa 594, or Alexa 647, (Life Technologies, Grand Island, NY) for 1 hr at room temperature. Following secondary incubation, sections were washed three times with PBS-T, dried, mounted on SuperFrost Plus slides (Thermofisher) using Prolong antifade mountant with DAPI (Thermofisher). Images were captured using a Nikon Eclipse TE300 fluorescence microscope with NIS Elements D4.10.01 software. Quantification of cell numbers was performed manually. Quantification of fluorescent areas was performed using ImageJ. Images were cropped and adjusted for brightness, contrast and color balance using Adobe Photoshop CC. Fluoromyelin staining was performed according to the manufacturer’s (Molecular Probes, Inc.) instructions.

2.6 |. Microglia morphometry

Morphometrical analysis of microglia was conducted as described by Chitu et al. (2020). Briefly, brain sections were stained with Iba1 for microglia as described in the previous section. Z series stacks were obtained by a Leica SP8 Confocal microscope at ×40 magnification with a 2 μm interval between images. Morphometric analysis of microglia (number of end points and length of microglial processes) was performed on maximum intensity projections of tissue sections from three mice/genotype using FIJI as described (Young & Morrison, 2018).

2.7 |. Single-molecule RNA in situ hybridization

RNA in situ hybridization experiments were performed using the RNAscope technology as previously described (Wang et al., 2012). Paired double-Z oligonucleotide probes were designed against target RNA using custom software (https://acdbio.com/catalog-probes). The RNAscope LS Multiplex Fluorescent Reagent Kit (Advanced Cell Diagnostics, Newark, CA) and RNAscope LS 4-Plex Ancillary Kit (Advanced Cell Diagnostics) were used according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Then, 15-μm thick fresh frozen tissue sections were postfixed for 90 min using 4% PFA at 4°C prior to RNAscope processing. The pretreatment conditions for RNAscope LS were the following: 10 min of ER2 at 95°C and 30 min of protease IV at room temperature. Opal 690, Opal 520, and Opal 570 (Akoya Biosciences, Menlo Park, CA) were used at concentrations of 1:1,500; 1:500; and 1:1,500, respectively. Each sample was controlled for RNA integrity with probes specific to three housekeeping genes (Polr2a, Ppib-C2, Ubc). Negative control background staining was evaluated using a probe specific to the bacterial dapB gene. Brightfield/Fluorescent images were acquired by a Leica SP8 confocal microscope using a ×40 objective. The following RNAscope probes were used:

RNAscope Probe-Mm-Csf2 ACD Cat# 319701.

RNAscope Probe-Mm-Gfap-C2 ACD Cat# 313211-C2.

RNAscope Probe-Mm-Pecam1-C3 ACD Cat# 316721-C3.

RNAscope Probe-Mm-Aif1-C2 ACD Cat# 319141-C2.

RNAscope Probe-Mm-Sox10-C3 ACD Cat # 435931-C3.

RNAscope 3-plex Positive Control Probe- Mm ACD Cat # 320881.

RNAscope 3-plex Negative Control Probe- Mm ACD Cat # 320871.

2.8 |. Csf2 qPCR

RNA was extracted from the anterior motor cortex and corpus callosum of 6-month-old mice as described (Chitu et al., 2015) and Csf2 qRTPCR was carried out utilizing the PrimePCR Csf2 assay qMmuCED0044875 from BIO-RAD.

2.9 |. Statistical analyses

Statistical analysis was conducted using the GraphPad Prism 8 software (GraphPad, La Jolla, CA). Data were analyzed for the identification of outliers using the Grubbs’ method, and for Gaussian distribution by Shapiro–Wilk normality test. The screened data were further analyzed using Student’s t test, the Kruskal–Wallis test or by analysis of variance (ANOVA), when appropriate. When significant effects were detected, single differences between genotypes were analyzed by post hoc multiple comparison tests (Dunnett’s, Bonferroni, Holm-Sidak, and Fisher’s LSD, as indicated in each figure). The level of significance was set at p < .05. For those comparisons in which no statistical significance is indicated in the figure panels, the p value was > .05. Data within each group are presented as mean ± SEM. Sample sizes for each experiment are indicated in the figure legends.

3 |. RESULTS

3.1 |. Behavioral deficits in mouse ALSP are reproduced by microglial, not neuronal, Csf1r heterozygosity

To investigate the effects of microglial deletion of a single Csf1r allele we utilized Csf1rfl/+; Cx3cr1Cre/+ (MCsf1rhet) mice (Goldmann et al., 2013; Li et al., 2006). To study loss of neuronal expression of a single Csf1r allele, we utilized Csf1rfl/+; Nestin-Cre/+ (NCsf1rhet) mice. Although the neural progenitor cell driver, Nestin-Cre (Tronche et al., 1999), drives recombination in all neural lineage cells, in NCsf1rhet mice the targeting is physiologically relevant only in neurons because the CSF-1R is not expressed by astrocytes or oligodendrocytes (Nandi et al., 2012). Behavioral phenotypes previously described (Chitu et al., 2020) in Csf1r+/− mice were examined in MCsf1rhet, NCsf1rhet and control mice.

Assessment of short-term memory in the Y-maze (Figure 1a) revealed that in contrast to control and NCsf1rhet mice, MCsf1rhet mice failed to choose the novel arm over the known arm (right panel). No difference in total number of arm entries was detected (left panel) indicating that the poor performance of the MCsf1rhet mice was not due to reduced exploration. Spatial learning and long-term memory were investigated using the MWM test (Figure 1b). No significant difference in the ability of mice to reach a visible platform was observed indicating absence of visual and motivational deficits in the different genotypes (left panel). Csf1r+/− mice alone covered significantly longer distance in finding the hidden platform during the acquisition phase (middle panel). Long-term memory was assessed as the number of platform area crossings 48 hr after 7 days of training. Csf1r+/− mice exhibited reduced crossings and MCsf1rhet mice also exhibited a strong trend (p = .14), compared with the control and NCsf1rhet mice (right panel). Long-term memory was further evaluated in the fear conditioning paradigm. As the Nestin-Cre transgene alone has previously been shown to affect memory assessed by fear conditioning (Giusti et al., 2014), long-term memory in this paradigm was investigated only in MCsf1rhet mice, which exhibited impaired contextual memory (Figure 1c). Thus, both short- and long-term memory were impaired by microglial monoallelic Csf1r deletion, but not by neuronal deletion.

FIGURE 1.

Deletion of a single Csf1r allele in the microglial lineage reproduces the behavioral deficits of adult onset leukoencephalopathy with axonal spheroids and pigmented glia (ALSP) (Csf1r+/−) mice. The test performed, age and number of mice, and retention interval (RI) are indicated in each panel. (a–c) Cognition: (a) Left: Similar exploratory activity for all genotypes assessed by the number of total entries into the arms of the Y-maze (ANOVA, Dunnett’s). Right: Lack of exploratory preference for the novel arm by MCsf1rhet mice (one-way ANOVA, Bonferroni’s). (b) Morris water maze. Left: No visual or motivational deficit in any genotype assessed by the path length covered to reach the visible platform (two-way ANOVA, Dunnett’s). Center: Csf1r+/− mice exhibit deficits in learning the location of the hidden platform (two-way ANOVA, Dunnett’s). Right: Long-term deficits in Csf1r+/− mice revealed by the number of counter crossings into the platform location (one-way ANOVA, Fisher’s). (c) Fear conditioning: Deficitof long-term associative memory in Csf1r+/− and MCsf1rhet mice assessed by the percentage of freezing during the contextual memory test (one-way ANOVA, Holm-Sidak’s). (d,e) Anxiety: (d) Behavior spectrometer: Reduction of the track length in the central arena of the field reveals an overt anxious phenotype for MCsf1rhet mice (Kruskal–Wallis test, Dunn’s). (e) Elevated zero maze: Older MCsf1rhet mice spend less time in the open zone indicating the persistence of anxiety (Kruskal–Wallis test, Dunn’s). (f) Motor coordination: Increased number of slips on the balance beam in McCsf1rhet mice (Kruskal–Wallis test, Dunn’s). Data are presented as means ± SEM. Only significantly different changes are marked by asterisks. *, p < .05; **, p < .01; ***, p < .001 [Color figure can be viewed at wileyonlinelibrary.com]

In the behavioral spectrometer, the track length in the central arena of the field, was reduced in MCsf1rhet mice compared with control and NCsf1rhet mice (Figure 1d), suggestive of anxiety. Consistent with this, MCsf1rhet mice spent less time in the open zone of the annular apparatus of an elevated zero maze, compared with Csf1rfl/+ or NCsf1rhet mice (Figure 1e). Thus microglial, but not neuronal deletion of a single Csf1r allele, reproduced the anxiety phenotype of Csf1r heterozygous mice.

Assessment of motor coordination on the balance beam identified deficits solely in MCsf1rhet mice, reflected in an increased number of slips made while crossing the beam (Figure 1f). No effect of Cx3cr1 heterozygosity alone was observed in the above tests (Figure S1), indicating that the behavioral deficits of the MCsf1rhet mice were due to the microglial-specific loss of a Csf1r allele.

The results indicate that anxiety-like behavior, cognitive and motor coordination deficits reported for Csf1r+/− mice are reproduced by microglial, but not by neuronal Csf1r heterozygosity.

3.2 |. Csf1r heterozygosity in microglia is sufficient for microgliosis

Increased microglial densities become apparent in brains of Csf1r+/− mice as early as 11-weeks of age (Chitu et al., 2015). Iba1 staining at 16-months of age revealed significant increases in microglial densities in MCsf1rhet mice compared to control mice in the hippocampus, deep cerebellar nuclei, fornix, corpus callosum and cerebellar white matter (Figure 2a–c). Strong trends for increases in the motor (p = .12) and cerebellar (p = .06) cortices were also observed (Figure 2a,c). In contrast, no increase in microglial density was detected in NCsf1rhet mice when compared to Csf1rfl/+ control mice (Figure S2a,b).

FIGURE 2.

Csf1r microglial heterozygosity reproduces the cerebral microgliosis, supraventricular microglial activation and oxidative stress of Csf1r+/− mice (a, b) Iba1+ cell densities (green) in different areas of brains of 18 to 21-month-old Cx3cr1Cre/+ and MCsf1rhet mice. (a) Gray Matter: OB, olfactory bulb; Cx, primary motor cortex; Hp, hippocampus; DCbNu, deep cerebellar nuclei; CbCx, cerebellar cortex; (b) white matter: Fornix; CC, corpus callosum; CbWM, cerebellar white matter; Scale bar, 100 μm applies to all panels. (c) Quantification of data in a,b (4 Cx3cr1Cre/+ and 5 MCsf1rhet mice). (d) Microglial patch located in the supraventricular region of the corpus callosum (arrow). Scale bar, 350 μm applies to both panels. (e) Quantification of the percentage of sections presenting callosal patches of dense microglia (5 mice per genotype). (f,g) Morphology (f) and quantification (g) of the Iba1+ cell ramifications in the supraventricular region of the corpus callosum (three mice per genotype). Scale bar, 50 μm applies to both panels. (h) Expression of Poly(ADP-Ribose) (PAR) in the CC of 18 to 21-month-old Cx3cr1Cre/+ and MCsf1rhet mice. Scale bar, 100 μm, applies to all panels. (i) Quantification of the percentage of PAR+ area in the supraventricular region of the corpus callosum (three mice per genotype). Data, presented as means ± SEM, were analyzed using the Unpaired t test. *, p < .05 [Color figure can be viewed at wileyonlinelibrary.com]

A remarkable feature of Csf1r+/− mice is the presence of patches of high microglial density in the supraventricular area of the corpus callosum (Chitu et al., 2020). Analysis of multiple sagittal sections revealed that the supraventricular microglial patches were more frequently encountered in the white matter of MCsf1rhet mice than of Csf1fl/+ or NCsf1rhet mice (Figures 2d,e and S2c,d). Microglia in these patches in MCsf1rhet brains exhibited an activated morphology, illustrated by decreased dendritic branching and shortening of their processes (Figure 2f,g). Interestingly, compared with Csf1rfl/+ control mice, callosal microglia in NCsf1rhet mice exhibited decreased dendritic branching, but no difference in process length, indicating a partial activation (Figure S2e,f). The microglia located in the supraventricular patches within the corpus callosum of MCsf1rhet mice expressed elevated levels of poly (ADP-ribose) (Figure 2h,i), a marker of oxidative stress previously detected in Csf1r+/− mice (Chitu et al., 2020). Consistent with their partial activation status, microglia from NCsf1rhet mice did not exhibit increased poly (ADP-ribose) staining (Figure S2g,h). These studies demonstrate that decreased CSF-1R expression in microglia is sufficient to increase their densities and activation.

3.3 |. Microglial, but not neuronal loss of a single Csf1r allele is sufficient for demyelination

Microglia in the supraventricular patches of old Csf1r+/− mice express Cystatin F, a marker of ongoing demyelination coupled to remyelination (Chitu et al., 2020). This feature was phenocopied in MCsf1rhet brains (Figure 3a) while no increase in Cystatin F expression was observed in the corpus callosum of NCsf1rhet brains (Figure S3a). Also, reduction of fluoromyelin staining was observed in the corpus callosum and fimbria of MCsf1rhet brains (Figure 3b), while no differences were detected in the NCsf1rhet brains (Figure S3b). To study the lineage-specific contribution of Csf1r heterozygosity to callosal demyelination, we carried out ultrastructural analysis of cross sections of corpus callosum from 12-month-old MCsf1rhet and NCsf1rhet mice and their respective controls. Compared with their controls, G-ratios were increased in axons of mice with microglial, but not neural lineage Csf1r reduction (Figure 3c–h). Analysis of age-related structural modifications in myelin sheaths (Figure 3i) revealed an exacerbation of myelin degeneration within axons in the MCsf1rhet mice. In contrast, there were no significant changes in age-related structural modifications in myelin sheaths of NCsf1rhet mice (Figure 3j). These data indicate that microglial deletion of a single Csf1r allele is sufficient to trigger the loss of myelin previously reported in Csf1r+/− mice (Chitu et al., 2020).

FIGURE 3.

Csf1r microglial heterozygosity phenocopies the callosal demyelination of Csf1r+/− mice (a) Left, expression of Cystatin F in the CC of 18 to 21-month-old Cx3cr1Cre/+ and MCsf1rhet mice. Scale bar, 100 μm, applies to all panels. Right, quantification of the percentage of Cystatin F area in the supraventricular region of CC of Cx3cr1Cre/+ and MCsf1rhet mice (unpaired t test). (b) Fluoromyelin staining and fluorescence quantification in corpus callosum, fimbria and cerebellar white matter (WM) of 18 to 21-month-old Cx3cr1Cre/+ and MCsf1rhet mice. Scale bar, 100 μm, applies to all panels. Data are presented as means ± SEM (5 mice per genotype, unpaired t test). (c) Myelin and axonal ultrastructure in callosal cross sections from 12-month-old mice. Scale bar, 2 μm, applies to all panels. (d–g) Scatter plots of G-ratio distribution where trend line indicates an overt reduction in myelin thickness in MCsf1rhet compared with Cx3cr1Cre/+ mice. (h) Significant G-ratio increases in small and medium diameter neuronal fibers of MCsf1rhet mice (two to three mice per genotype, two-way ANOVA, Dunnett’s multiple comparisons test, p = .07 for the Cx3cr1Cre/+-MCsf1rhet comparison in the 1,001–1,700 nm fiber diameter range). (i,j) Analysis of age-induced myelin pathology in 12-month-old mice: (i) Representative images of abnormalities of myelin sheath structure. Scale bar, 2 μm, applies to all panels. (j) Quantification of myelin abnormalities reveals an increased percentage of axons exhibiting myelin degeneration. Data are presented as means ± SEM (two to three mice per genotype, two-way ANOVA, Dunnett’s multiple comparisons test, *, p < .05; **, p < .01) [Color figure can be viewed at wileyonlinelibrary.com]

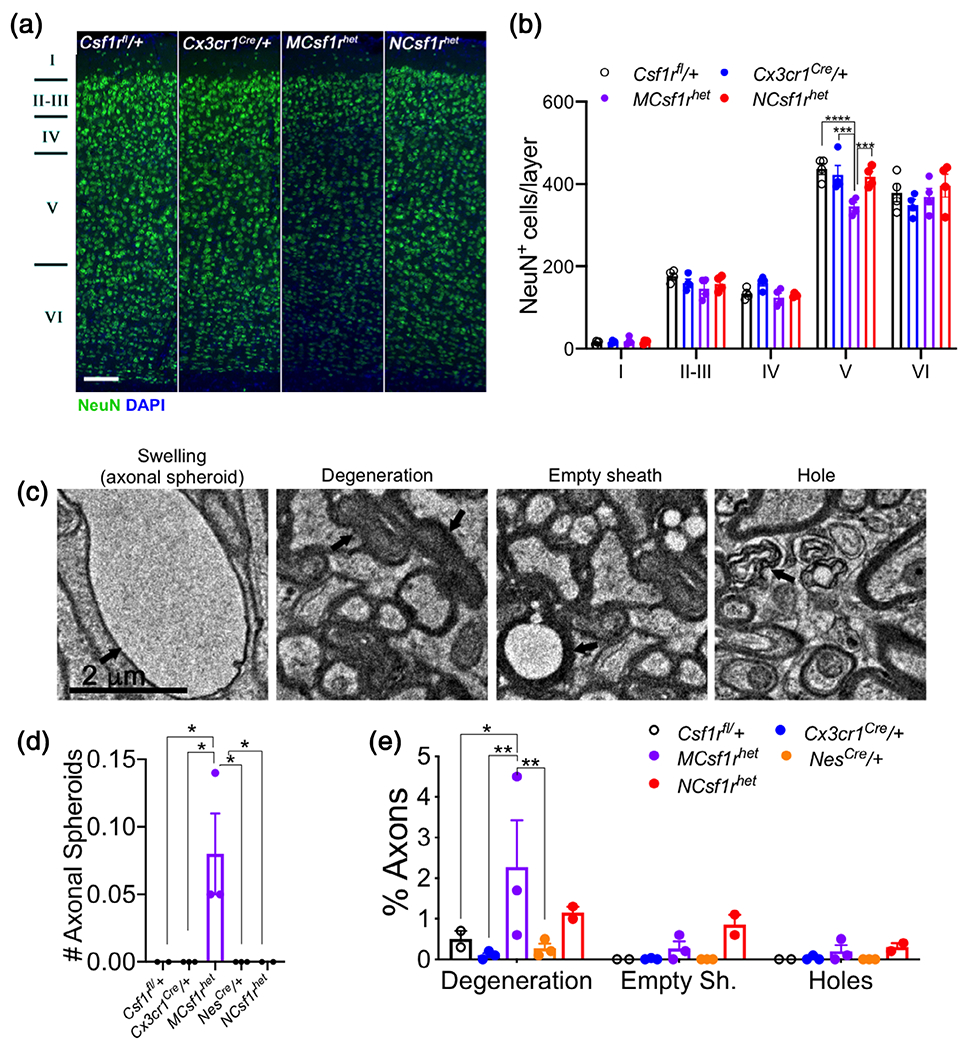

3.4 |. Microglial but not neural lineage Csf1r heterozygosity promotes loss of cortical layer V neurons and neurodegeneration

A characteristic of ALSP mice is that cortical layer V neurons are gradually lost between 3 and 21 months of age (Chitu et al., 2015; Chitu et al., 2020). This could be a consequence of loss of microglial homeostatic functions. However, since previous studies (Luo et al., 2013) reported that CSF-1R signaling mediates neuronal survival cell autonomously and a subpopulation of layer V neurons express Csf1r (Chitu et al., 2015; Clare et al., 2018), it is also possible that the reduced survival of layer V neurons is mediated by loss of direct regulation by the CSF-1R. Analysis of cortical neurons showed that MCsf1rhet, but not NCsf1rhet mice, reproduced the loss in layer V neurons (Figure 4a,b), indicating that these cells are lost due to microglial dysfunction. Consistent with this, axonal degeneration and the presence of axonal spheroids, characteristic of Csf1r+/− mice, were only observed in the MCsf1rhet mice (Figure 4c–e).

FIGURE 4.

Microglial deletion of a single allele of Csf1r phenocopies the neurodegenerative phenotype of Csf1r+/− mice. (a) Loss in cortical layer V neurons in the primary motor cortex of 18 to 21-month-old MCsf1rhet mice. Scale bar, 100 μm, applies to all panels. (b) Quantification of the number of NeuN+ neurons in the layers of the primary motor cortex (data from 5 mice/genotype, two-way ANOVA, Dunnett’s multiple comparisons test). (c) Representative images of age-induced axonal pathologies. Scale bar, 2 μm, applies to all panels. (d) Quantification of age-induced axonal pathologies in Csf1rfl/+, Cx3cr1Cre/+, MCsf1rhet, NesCre/+, NCsf1rhet mice (two to three mice/genotype, >2,000 neurons/genotype, two-way ANOVA, Dunnett’s multiple comparisons test, *, p < .05; **, p < .01) [Color figure can be viewed at wileyonlinelibrary.com]

3.5 |. Microglial Csf1r heterozygosity triggers the expansion of CSF-2-producing neural lineage cells

Our previous study showed that increased CSF-2 expression is a major contributor to the ALSP-like disease phenotype of Csf1r+/− mice (Chitu et al., 2020). CSF-2 has been reported to be expressed by astrocytes (Choi, Lee, Lim, Satoh, & Kim, 2014), oligodendrocytes (Kim et al., 2014), microglia (Lee, Liu, Brosnan, & Dickson, 1994), and endothelial cells (Zsebo et al., 1988). Examination of the expression of Csf2 in these cell types by RNAscope revealed that indeed, in aged Csf1r+/− mice the major contributors to the elevated CSF-2 expression in the corpus callosum are astrocytes, oligodendrocytes and, to a lesser extent, microglia (Figure 5a) while in the cortex the main contribution was from oligodendrocytes (Figure 5b). Cerebral Csf2 expression was also elevated in MCsf1rhet mice (Figure 5c) and the densities of the major cell types that produce CSF-2, astrocytes and oligodendrocytes were also increased in the supraventricular area of the corpus callosum where microgliosis is typically observed (Figure 5d and Figure 2d,e). The results indicate that altered CSF-1R signaling in microglia is sufficient to cause their activation which in turn leads to the expansion of Csf2-producing neural lineage cells.

FIGURE 5.

Neuroglia are the major sources of increased Csf2 expression in Csf1r+/− mice (a,b) Single-molecule RNA in situ hybridization (RNAscope) analysis of Csf2 expression in glia and endothelial cells in the corpus callosum (a) and cerebral cortex (b) of 18-month-old mice, showing Csf2 expression in Gfap+ (astrocytes), Sox10+ (oligodendrocytes), Aif1+ (microglia), and Pecam1+ (endothelial) cells. Scale bar, 10 μm, applies to all panels. Nuclear fragmentation was caused by tissue processing. Quantitation: (a) four mice per genotype for all panels except for the upper and lower panels (three mice per genotype); (b) four mice per genotype for all panels except for the upper panels (three mice per genotype) and lower panels (3 Csf1r+/− mice). Data analyzed by unpaired Student’s t test. (c) Increased expression of Csf2 in 6-month-old MCsf1rhet mice (4 Cx3Cr1Cre/+ and eight MCsf1rhet mice, unpaired t test). (d) Increased densities of astrocytes and oligodendrocytes in supraventricular microglial patches of 18 to 21-month-old MCsf1rhet mice. Quantitation: Left panel, 4 Cx3Cr1Cre/+ and 5 MCsf1rhet mice; middle panel, 5 Cx3Cr1Cre/+ mice and 4 MCsf1rhet mice; right panel, 4 Cx3Cr1Cre/+ and 5 MCsf1rhet mice; unpaired t test. Scale bar, 100 μm, applies to all panels. Data are presented as means ± SEM. *p < .05, **p < .01 [Color figure can be viewed at wileyonlinelibrary.com]

4 |. DISCUSSION

Previous work has shown that Csf1r+/− ALSP mice exhibit behavioral deficits and histological alterations, including an early increase in microglial densities in different regions of the brain, callosal demyelination, axonal pathologies and a reduction in the number of neurons in the layer V of the cerebral cortex (Chitu et al., 2015; Chitu et al., 2020). The early increase in microglial density was accompanied by increased cerebral expression of Csf2 mRNA, encoding a microglial mitogen. The role of CSF-2 as a major mediator of ALSP pathology was recently established by demonstrating that deletion of a single Csf2 allele in ALSP mice prevented development of the behavioral deficits, normalized most pathologies and partially restored the changes in the microglial transcriptome (Chitu et al., 2020). However, since cortical layer V neurons are gradually lost in ALSP mice and a proportion of these neurons express the CSF-1R (Chitu et al., 2015; Clare et al., 2018), we investigated whether decreased CSF-1R expression could affect neuronal survival independently of its effect on microglial functions. While at present it is unclear whether MCsf1rhet microglia are directly responsible for neuron and oligodendrocyte cell death, or whether they start a cascade involving other cell types as effectors of degeneration (see below), the data clearly show that dysregulation of microglia function is necessary and sufficient for the development of the behavioral deficits, microgliosis and the associated demyelination and neurodegeneration characteristic of the Csf1r+/− mouse model of ALSP. In contrast, CSF-1R signaling in the neural lineage was dispensable for neuronal survival and function in aging mice. Indeed, the fact that microglial and not neural Csf1r heterozygosity phenocopies the reduction in layer V neurons indicates that the neurodegeneration is not due to impairment of CSF-1R signaling for survival in neurons. Our studies prompt investigation of the causal role of microglial activation in ALSP.

How might Csf1r+/− microglia mediate the selective loss of layer V neurons? It is unlikely this is due to a decrease in their production of neurotrophic factors since, compared to wild type counterparts, microglial transcripts for several neurotrophic factors, including Neurturin, Neudesin, Midkine, IGF2, and VEGFβ were increased in symptomatic Csf1r+/− mice (Chitu et al., 2020). In fact, the transcriptomic data in the same study suggested that dysregulation of CSF-1R signaling in microglia produces a demyelinating and pro-oxidant phenotype and the induction of markers of demyelination (Cystatin F) and oxidative stress (poly(ADPribose)) has been reproduced in MCsf1rhet mice (Figures 2h,i and 3a). Interestingly, studies in multiple sclerosis have revealed that ongoing demyelination in focal lesions is associated with axonal transport deficits and Wallerian degeneration (Dziedzic et al., 2010). Thus, it is tempting to speculate that in ALSP, microglia cause the loss of callosal white matter and consequent Wallerian degeneration of cortical neurons. Indeed, the cell bodies of callosal projection neurons reside primarily in neocortical layers II/III and V, (Fame, MacDonald, & Macklis, 2011), where we have reproducibly found a tendency for, and statistically significant, neuronal loss, respectively ((Chitu et al., 2020) and Figure 4a,b). Further investigations are needed to establish the relation between callosal demyelination and the loss of cortical neurons.

Irrespective of the mechanisms underlying the neurodegeneration, our data reinforce the concept that ALSP is a primary microgliopathy (Konno et al., 2018) and support therapeutic approaches that aim to limit microglial activation or to replace mutant with wild type microglia. A recent study of a family in which five members possessed an ALSP mutant CSF1R allele indicated that expression of wild-type CSF1R in some cells, achieved by mosaicism or chimerism, conferred benefit and suggested that hematopoietic stem cell transplantation might have a therapeutic role for this disorder (Eichler et al., 2016). Two additional reports of bone marrow transplantation of ALSP patients suggest some stabilization of disease progression at 12–30 months post-transplantation (Gelfand et al., 2020; Mochel et al., 2019). These studies are encouraging, however, given the yolk sac origin of microglia (Ginhoux et al., 2010), their exact replacement presents a therapeutic challenge. Additional experimentation in the mouse model, aimed at establishing conditions that permit efficient colonization of the brain parenchyma and long-term engraftment of precursor cells capable of generating homeostatic microglia-like progeny is warranted.

Consistent with the elevated expression of Csf2 in MCsf1rhet, but not NCsf1rhet mice, RNAscope shows that the major cell types contributing to the Csf2 elevation in Csf1r+/− mice are astrocytes and oligodendrocytes, and both of these cell types expand in white matter areas with patchy microgliosis in MCsf1rhet mice. Thus, CSF-1R heterozygosity in microglia produces an activated microglial state that promotes the expansion of CSF-2 producing neural lineage cells, possibly via paracrine interactions. Indeed, other studies have shown that microglia/astrocyte interaction enhances astrogliosis (Mohri et al., 2006) and oligodendrogliogenesis is positively regulated by microglia (Hagemeyer et al., 2017; Nandi et al., 2012). Elevation of CSF-2, a powerful mitogen, in turn feeds back to increase microglial densities in the Csf1r+/− brain and could also have autocrine effects in the CSF-2 producing cells. It will be important to determine the nature of the signals released by Csf1r+/− microglia that trigger the expansion of these cells. Since the CSF-2 producing cells also express the CSF-2 receptor (Choi et al., 2014; Kim et al., 2014; Lee et al., 1994; Sawada, Itoh, Suzumura, & Marunouchi, 1993), investigation of the role of CSF-2 in coordinating microglial, astrocyte and oligodendrocyte responses to aging and ALSP pathology will be necessary. It is now clear that this effort will require an integration of multiomic microglia, astrocyte, and oligodendrocyte datasets obtained at different stages of disease and under different genetic interventions (Liddelow, Marsh, & Stevens, 2020).

Of particular interest, in terms of understanding the mechanism of ALSP disease development, is the fact that the demyelination is not due to a shortage of oligodendrocytes. Consistent with this, Csf1 deficiency has been reported to disturb CNS white matter remyelination (Wylot, Mieczkowski, Niedziolka, Kaminska, & Zawadzka, 2019). Probing how decreased CSF-1R signaling disrupts the ability of microglia to communicate with, or support the function of, both mature and newly generated oligodendrocytes is essential for understanding ALSP. Overall, our studies provide new avenues for investigation of how disruption of microglial/neuroglial interactions contributes to ALSP.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The authors thank Hillary Guzik, Andrea Briceno and Dr Vera DesMarais of the Einstein Analytical Imaging Facility for help with imaging and histomorphometry. This work was supported by grants from the National Institutes of Health: Grant R01NS091519 (to E. R. S.), NS096144 (to M. F. M.), U54 HD090260 (support for the Rose F. Kennedy IDDRC), and the P30CA013330 NCI Cancer Center Grant. The authors also thank David and Ruth Levine for their support.

Funding information

David and Ruth Levine; National Institutes of Health, Grant/Award Numbers: R01NS096144, P30CA013330, R01NS091519, U54 HD090260

Abbreviations:

- CSF-1 R

colony stimulating factor-1 receptor

- CSF-2

colony stimulating factor-2 (granulocyte-macrophage CSF, GM-CSF)

- ALSP

adult-onset leukoencephalopathy with axonal spheroids and pigmented glia

- MCsf1rhet

Csf1rfl/+

- Cx3cr1Cre/+

NCsf1rhet

- Csf1rfl/+

Nestin-Cre/+

Footnotes

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

SUPPORTING INFORMATION

Additional supporting information may be found online in the Supporting Information section at the end of this article.

DATA AVAILABILITY STATEMENT

Data sharing not applicable to this article as no datasets were generated or analysed during the current study.

REFERENCES

- Biundo F, del Prete D, Zhang H, Arancio O, & D’Adamio L (2018). A role for tau in learning, memory and synaptic plasticity. Scientific Reports, 8(1), 3184. 10.1038/s41598-018-21596-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Biundo F, Ishiwari K, del Prete D, & D’Adamio L (2016). Deletion of the gamma-secretase subunits Aph1B/C impairs memory and worsens the deficits of knock-in mice modeling the Alzheimer-like familial Danish dementia. Oncotarget, 7(11), 11923–11944. 10.18632/oncotarget.7389 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brodkin J, Frank D, Grippo R, Hausfater M, Gulinello M, Achterholt N, & Gutzen C (2014). Validation and implementation of a novel high-throughput behavioral phenotyping instrument for mice. Journal of Neuroscience Methods, 224, 48–57. 10.1016/j.jneumeth.2013.12.010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chitu V, Biundo F, Shlager GGL, Park ES, Wang P, Gulinello ME, … Stanley ER (2020). Microglial homeostasis requires balanced CSF-1/CSF-2 receptor signaling. Cell Reports, 30(9), 3004–3019 e3005. 10.1016/j.celrep.2020.02.028 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chitu V, Gokhan S, Gulinello M, Branch CA, Patil M, Basu R, … Stanley ER (2015). Phenotypic characterization of a Csf1r haploinsufficient mouse model of adult-onset leukodystrophy with axonal spheroids and pigmented glia (ALSP). Neurobiology of Disease, 74, 219–228. 10.1016/j.nbd.2014.12.001 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chitu V, Gokhan S, Nandi S, Mehler MF, & Stanley ER (2016). Emerging roles for CSF-1 receptor and its ligands in the nervous system. Trends in Neurosciences, 39(6), 378–393. 10.1016/j.tins.2016.03.005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Choi SS, Lee HJ, Lim I, Satoh J, & Kim SU (2014). Human astrocytes: Secretome profiles of cytokines and chemokines. PLoS One, 9 (4), e92325. 10.1371/journal.pone.0092325 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clare AJ, Day RC, Empson RM, & Hughes SM (2018). Transcriptome profiling of layer 5 intratelencephalic projection neurons from the mature mouse motor cortex. Frontiers in Molecular Neuroscience, 11,410. 10.3389/fnmol.2018.00410 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dai XM, Ryan GR, Hapel AJ, Dominguez MG, Russell RG, Kapp S, … Stanley ER (2002). Targeted disruption of the mouse colony-stimulating factor 1 receptor gene results in osteopetrosis, mononuclear phagocyte deficiency, increased primitive progenitor cell frequencies, and reproductive defects. Blood, 99(1), 111–120. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dziedzic T, Metz I, Dallenga T, Konig FB, Muller S, Stadelmann C, & Bruck W (2010). Wallerian degeneration: A major component of early axonal pathology in multiple sclerosis. Brain Pathology, 20(5), 976–985. 10.1111/j.1750-3639.2010.00401.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eichler FS, Li J, Guo Y, Caruso PA, Bjonnes AC, Pan J, … Saxena R (2016). CSF1R mosaicism in a family with hereditary diffuse leukoencephalopathy with spheroids. Brain, 139(Pt 6), 1666–1672. 10.1093/brain/aww066 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fame RM, MacDonald JL, & Macklis JD (2011). Development, specification, and diversity of callosal projection neurons. Trends in Neurosciences, 34(1), 41–50. 10.1016/j.tins.2010.10.002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gelfand JM, Greenfield AL, Barkovich M, Mendelsohn BA, van Haren K, Hess CP, & Mannis GN (2020). Allogeneic HSCT for adult-onset leukoencephalopathy with spheroids and pigmented glia. Brain, 143(2), 503–511. 10.1093/brain/awz390 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ginhoux F, Greter M, Leboeuf M, Nandi S, See P, Gokhan S, … Merad M (2010). Fate mapping analysis reveals that adult microglia derive from primitive macrophages. Science, 330(6005), 841–845. 10.1126/science.1194637 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Giusti SA, Vercelli CA, Vogl AM, Kolarz AW, Pino NS, Deussing JM, & Refojo D (2014). Behavioral phenotyping of Nestin-Cre mice: Implications for genetic mouse models of psychiatric disorders. Journal of Psychiatric Research, 55, 87–95. 10.1016/j.jpsychires.2014.04.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goldmann T, Wieghofer P, Muller PF, Wolf Y, Varol D, Yona S, … Prinz M (2013). A new type of microglia gene targeting shows TAK1 to be pivotal in CNS autoimmune inflammation. Nature Neuroscience, 16(11), 1618–1626. 10.1038/nn.3531 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gulinello M, Chen F, & Dobrenis K (2008). Early deficits in motor coordination and cognitive dysfunction in a mouse model of the neurodegenerative lysosomal storage disorder, Sandhoff disease. Behavioural Brain Research, 193(2), 315–319. 10.1016/j.bbr.2008.06.016 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hagemeyer N, Hanft KM, Akriditou MA, Unger N, Park ES, Stanley ER, … Prinz M (2017). Microglia contribute to normal myelinogenesis and to oligodendrocyte progenitor maintenance during adulthood. Acta Neuropathologica, 134(3), 441–458. 10.1007/s00401-017-1747-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hao C, Guilbert LJ, & Fedoroff S (1990). Production of colony-stimulating factor-1 (CSF-1) by mouse astroglia in vitro. Journal of Neuroscience Research, 27(3), 314–323. 10.1002/jnr.490270310 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoffmann S, Murrell J, Harms L, Miller K, Meisel A, Brosch T, … Stenzel W (2014). Enlarging the nosological spectrum of hereditary diffuse leukoencephalopathy with axonal spheroids (HDLS). Brain Pathology, 24(5), 452–458. 10.1111/bpa.12120 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim WK, Kim D, Cui J, Jang HH, Kim KS, Lee HJ, … Ahn SM (2014). Secretome analysis of human oligodendrocytes derived from neural stem cells. PLoS One, 9(1), e84292. 10.1371/journal.pone.0084292 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Konno T, Kasanuki K, Ikeuchi T, Dickson DW, & Wszolek ZK (2018). CSF1R-related leukoencephalopathy: A major player in primary microgliopathies. Neurology, 91(24), 1092–1104. 10.1212/WNL.0000000000006642 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Konno T, Tada M, Koyama A, Nozaki H, Harigaya Y, … Ikeuchi T (2014). Haploinsufficiency of CSF-1R and clinicopathologic characterization in patients with HDLS. Neurology, 82(2), 139–148. 10.1212/WNL.0000000000000046 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee SC, Liu W, Brosnan CF, & Dickson DW (1994). GM-CSF promotes proliferation of human fetal and adult microglia in primary cultures. Glia, 12(4), 309–318. 10.1002/glia.440120407 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li J, Chen K, Zhu L, & Pollard JW (2006). Conditional deletion of the colony stimulating factor-1 receptor (c-fms proto-oncogene) in mice. Genesis, 44(7), 328–335. 10.1002/dvg.20219 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liddelow SA, Marsh SE, & Stevens B (2020). Microglia and astrocytes in disease: Dynamic duo or partners in crime? Trends in Immunology, 41, 820–835. 10.1016/j.it.2020.07.006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luo J, Elwood F, Britschgi M, Villeda S, Zhang H, Ding Z, … Wyss-Coray T (2013). Colony-stimulating factor 1 receptor (CSF1R) signaling in injured neurons facilitates protection and survival. The Journal of Experimental Medicine, 210(1), 157–172. 10.1084/jem.20120412 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mochel F, Delorme C, Czernecki V, Froger J, Cormier F, Ellie E, … Nguyen S (2019). Haematopoietic stem cell transplantation in CSF1R-related adult-onset leukoencephalopathy with axonal spheroids and pigmented glia. Journal of Neurology, Neurosurgery, and Psychiatry, 90(12), 1375–1376. 10.1136/jnnp-2019-320701 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mohri I, Taniike M, Taniguchi H, Kanekiyo T, Aritake K, Inui T, … Urade Y (2006). Prostaglandin D2-mediated microglia/astrocyte interaction enhances astrogliosis and demyelination in twitcher. The Journal of Neuroscience, 26(16), 4383–4393. 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.4531-05.2006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nandi S, Gokhan S, Dai XM, Wei S, Enikolopov G, Lin H, … Stanley ER (2012). The CSF-1 receptor ligands IL-34 and CSF-1 exhibit distinct developmental brain expression patterns and regulate neural progenitor cell maintenance and maturation. Developmental Biology, 367(2), 100–113. 10.1016/j.ydbio.2012.03.026 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rademakers R, Baker M, Nicholson AM, Rutherford NJ, Finch N, Soto-Ortolaza A, … Wszolek ZK (2011). Mutations in the colony stimulating factor 1 receptor (CSF1R) gene cause hereditary diffuse leukoencephalopathy with spheroids. Nature Genetics, 44(2), 200–205. 10.1038/ng.1027 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Raivich G, Gehrmann J, Moreno-Floros M, & Kreutzberg GW (1993). Microglia: Growth factor and mitogen receptors. Clinical Neuropathology, 12(5), 293–295. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sawada M, Itoh Y, Suzumura A, & Marunouchi T (1993). Expression of cytokine receptors in cultured neuronal and glial cells. Neuroscience Letters, 160(2), 131–134. 10.1016/0304-3940(93)90396-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sawada M, Suzumura A, Yamamoto H, & Marunouchi T (1990). Activation and proliferation of the isolated microglia by colony stimulating factor-1 and possible involvement of protein kinase C. Brain Research, 509(1), 119–124. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schindelin J, Arganda-Carreras I, Frise E, Kaynig V, Longair M, Pietzsch T, … Cardona A (2012). Fiji: An open-source platform for biological-image analysis. Nature Methods, 9(7), 676–682. 10.1038/nmeth.2019 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tronche F, Kellendonk C, Kretz O, Gass P, Anlag K, Orban PC, … Schutz G (1999). Disruption of the glucocorticoid receptor gene in the nervous system results in reduced anxiety. Nature Genetics, 23(1), 99–103. 10.1038/12703 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang F, Flanagan J, Su N, Wang LC, Bui S, Nielson A, … Luo Y (2012). RNAscope: A novel in situ RNA analysis platform for formalin-fixed, paraffin-embedded tissues. Journal of Molecular Diagnostics, 14 (1), 22–29. 10.1016/j.jmoldx.2011.08.002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang Y, Berezovska O, & Fedoroff S (1999). Expression of colony stimulating factor-1 receptor (CSF-1R) by CNS neurons in mice. Journal of Neuroscience Research, 57(5), 616–632. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wylot B, Mieczkowski J, Niedziolka S, Kaminska B, & Zawadzka M (2019). Csf1 deficiency dysregulates glial responses to demyelination and disturbs CNS White matter remyelination. Cell, 9(1). 10.3390/cells9010099 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yona S, Kim KW, Wolf Y, Mildner A, Varol D, Breker M, … Jung S (2013). Fate mapping reveals origins and dynamics of monocytes and tissue macrophages under homeostasis. Immunity, 38(1), 79–91. 10.1016/j.immuni.2012.12.001 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Young K, & Morrison H (2018). Quantifying microglia morphology from photomicrographs of immunohistochemistry prepared tissue using ImageJ. Journal of Visualized Experiments, (136). 10.3791/57648 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zsebo KM, Yuschenkoff VN, Schiffer S, Chang D, McCall E, Dinarello CA, … Bagby GCJ (1988). Vascular endothelial cells and granulopoiesis: Interleukin- 1 stimulates release of G-CSF and GM-CSF. Blood, 71, 99–103. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

Data sharing not applicable to this article as no datasets were generated or analysed during the current study.