Abstract

Photosystem I (PS I) has a symmetric structure with two highly similar branches of pigments at the center that are involved in electron transfer, but shows very different efficiency along the two branches. We have determined the structure of cyanobacterial PS I at room temperature (RT) using femtosecond X-ray pulses from an X-ray free electron laser (XFEL) that shows a clear expansion of the entire protein complex in the direction of the membrane plane, when compared to previous cryogenic structures. This trend was observed by complementary datasets taken at multiple XFEL beamlines. In the RT structure of PS I, we also observe conformational differences between the two branches in the reaction center around the secondary electron acceptors A1A and A1B. The π-stacked Phe residues are rotated with a more parallel orientation in the A-branch and an almost perpendicular confirmation in the B-branch, and the symmetry breaking PsaB-Trp673 is tilted and further away from A1A. These changes increase the asymmetry between the branches and may provide insights into the preferential directionality of electron transfer.

Subject terms: Biochemistry, Structural biology, Bioenergetics, Photosynthesis

Introduction

Photosystem I (PS I) is a large multisubunit pigment-protein complex involved in the light-driven electron transport across the thylakoid membrane that is present in all organisms that perform oxygenic photosynthesis. It consists of two large membrane intrinsic subunits (PsaA and PsaB) with 11 transmembrane helices each, which are surrounded by several smaller membrane intrinsic subunits, namely PsaF, PsaI, PsaJ, PsaK, PsaL, PsaM and PsaX in Thermosynechococcus (T.) elongatus. At the stromal side of the thylakoid membrane, PS I displays three membrane extrinsic subunits (PsaC, PsaD, PsaE) (Fig. 1). For cyanobacterial PS I, the complex usually forms a trimer (Fig. S1) with a total molecular weight of ~ 1 MDa1. The structure for a monomer of cyanobacterial PS I was found to be very similar to the structure of PS I found in higher plants2–4 and algae5, 6 with the important difference that in plant and algae, PS I occurs exclusively in a monomeric form and is surrounded by an array of light-harvesting complexes. Over the last 20 years, several PS I structures have been reported from different organisms at cryogenic temperatures. The first structure was from the cyanobacterium T. elongatus, initially at 6 Å resolution7 with subsequent improvements to 4 Å8, 9, and finally leading to a structure at 2.5 Å resolution1.

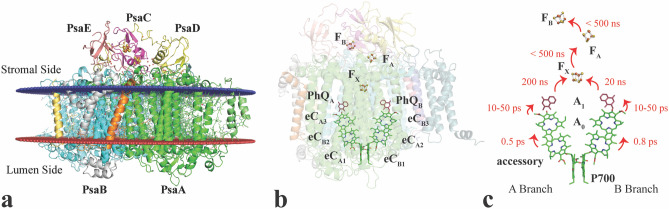

Figure 1.

Overview of PS I. (a) Membrane plane view of one monomer of PS I with multiple subunits represented in different colors. The two main subunits PsaA and PsaB and the three membrane extrinsic subunits PsaD, PsaC, and PsaE are labeled. Many of the trans-membrane helices are visible between the membrane planes (red and blue planes). Membrane orientation generated via the PPM server (https://opm.phar.umich.edu/ppm_server). (b) View of the reaction center part of PS I. The cofactors involved in electron transfer are arranged in two pseudo-symmetrical branches comprised of Chl eCA1, eCB2, eCA3 and PhQA on one side and Chl eCB1, eCA2, eCB3 and PhQB on the other side. Both branches connect at the [4Fe4S] cluster FX at the stromal side, with FA and FB, the two final [4Fe4S] clusters, breaking the symmetry. (c) Electron transfer times along the A and B-branch of the reaction center of PS I. Cofactors are labeled according to their function, with P700 and the accessory Chls forming the primary donor, A0 being the first and A1 the secondary electron acceptor in the electron transfer chain on each branch. Figure generated with Pymol v. 2.4.0a0. https://pymol.org.

The internal antenna system of PS I comprises ~ 90 chlorophyll a (Chl) and 22 β-carotenoids (Car). The central two subunits PsaA and PsaB harbor the cofactors of the transmembrane electron transfer chain in a symmetrical fashion, along two pseudo-symmetrical branches, similar to the arrangement found in the purple bacterial reaction center (PBRC)10. The A branch of PS I contains chlorophylls eCA1, eCB2, eCA3 and phylloquinone PhQA, and the B branch contains chlorophylls eCB1, eCA2, eCB3 and phylloquinone PhQB (Fig. 1b). Upon light absorption, the excitation energy is transferred from the antenna via the connecting chlorophylls towards P700, where charge separation is initiated within ~ 1 ps. The identity of the first donor Chl is still debated11, with P70012 or the accessory Chl13–15 as candidates (eCB2 or eCA2, Fig. 1c). Within 10–50 ps the electron is transferred from the acceptor chlorophyll A0 to A1, a phylloquinone (PhQ) resulting in the formation of the semi phylloquinone PhQ— P700+ pair12–15. Next, the electron is transferred with two distinct phases of 20 and 200 ns to the central [4Fe4S] cluster termed FX, which is located at the interface between the A and B subunits and is coordinated by two Cys residues from each of the two subunits. Finally, the electron is transferred to the two [4Fe4S] clusters in subunit PsaC, termed FA and FB (Fig. 1c, see also e.g. Kurashov et al.16). These can, in turn, donate the electron to the external electron carrier, a ferredoxin. EPR studies on co-crystals of PS I with ferredoxin indicated intermittent binding to the surface of PsaC that is exposed towards the stroma17, and was confirmed in recent structures of ferredoxin bound to PS I18, 19.

The structure of the reaction center found in PS I with the arrangement of the central cofactors in two pseudo-symmetrical branches, both starting at P700 and ending at FX, led to the question of how this electron transfer proceeds (it should be noted that P700 is not a symmetric Chl dimer but one Chl is a Chl a′, an epimer of chlorophyll a). Electron transfer could either proceed along one branch solely, along both branches equally, or along both branches with different ratios. Previous crystal structures of PS I showed that the symmetry of the two branches is broken by the link between the last acceptor FX, and the preceding phylloquinone in the electron transfer chain; with Trp673 present in the B branch, and Glycine in the A branch1. Also, a difference in the nature of lipids located close to PhQA and PhQB was observed, with a negatively charged phospholipid located 10 Å away from PhQB, and an uncharged galactolipid located ~ 11 Å away from PhQA20.

A combination of spectroscopic and mutagenesis studies revealed that both branches are active and that the 200 ns phase is associated with the A branch21. Femtosecond transient absorption spectroscopy further showed that the primary charge separation step can occur on both branches and that they compete with each other14. There are different results regarding the partitioning ratio and ET rates along the two branches22; depending on the species and experimental conditions, branching ratio of 90:10–44:56% (for A and B branches, respectively) have been reported22–25. Kinetic and energetic differences between the two branches have been the topic of numerous studies. However, details of the mechanisms and clear experimental evidence for the various models are presently a subject of contention. Crystallographic data measured at physiological conditions may assist in answering some of the outstanding unknowns regarding electron transfer directionality in this system.

The regulation and fine-tuning of cofactor properties (especially the redox potential) by the interaction with the protein environment are key to direct the flow of electrons in photosynthetic protein assemblies like PS I. Time-resolved crystallography is an ideal tool to study structural changes that underlie and stabilize light-induced charge separation, and can potentially help to better understand the role of the protein environment for determining cofactor properties. With the advent of X-ray free-electron lasers (XFELs) over the last 10 years, serial femtosecond crystallography (SFX) has developed into a powerful tool to obtain structures at room temperature (RT), without accompanying X-ray induced structural changes (“diffraction before destruction”)26–28. The method pioneered by Fromme, Spence, Chapman, Neutze and coworkers using micro crystals of PS I, determined the first RT structure of PS I at ~ 8 Å resolution by recording thousands of individual diffraction patterns, each obtained from a new micro crystal delivered to the X-ray interaction point by a gas-focused liquid jet20. Recently, an SFX crystal structure of PS I was obtained by data collected at the European XFEL29. The 2.9 Å resolution structure demonstrated the proof of concept that data from complex, membrane-bound proteins could be measured using MHz X-ray repetition rates; however, owing to resolution limits, much structural information cannot be interpreted from these maps. Interestingly the authors of this study reported a space group P21 for their PSI microcrystals as opposed to the P63 space group previously reported for the cryogenic data1.

It should be emphasized that changes in temperature can cause important structural differences that could be relevant for enzymatic function, as evidenced in studies by Fraser and van den Bedem et al., comparing traditional cryogenic data collection at 100 K with results from RT measurements30, see also Ref.31 for a recent example of differences observed between XFEL RT and synchrotron cryogenic structures. These studies were mostly focused on soluble proteins, whereas only limited information is available for temperature-dependent structural changes in membrane proteins30, 32. In the recent work by Young et al., it was found that, for the membrane protein complex PS II, a uniform expansion of the entire complex along the membrane plane by about 0.5 Å occurs when comparing the room temperature structure to cryogenic structures32.

In order to allow efficient time-resolved X-ray diffraction studies at XFELs, we recently developed a Drop-on-Tape (DOT) setup33. This DOT setup allows optical pump X-ray probe experiments with delay times ranging from femtoseconds out to seconds, at room temperature, with very high sample hit rates leading to reduced measurement time and sample consumption.

Here, we studied the details of the cofactor–protein interaction in PS I at near-physiological conditions to gain insights into factors that are responsible for fine-tuning the electron transfer pathway in PS I. We utilized microcrystals of PS I from the thermophilic cyanobacterium T. elongatus with our DOT approach and XFEL generated fs X-ray pulses. Clear differences around the PhQ cofactors in both branches A and B, compared to the previously reported cryogenic structures were observed, possibly contributing to the differences in electron transfer rates along the two branches.

Results

Overall structure

In order to obtain an undamaged room temperature structure in the dark state of PS I, we utilized the fs X-ray pulses of the LCLS34 and the SwissFEL35. We used the DOT setup33 installed at the MFX instrument of LCLS36 or at the Bernina instrument at SwissFEL35 to measure X-ray diffraction data from microcrystals (15–25 µm) of trimeric PS I from T. elongatus (Methods, Fig. S2). The resulting data set was processed with the cctbx.xfel software suite37 (see Methods). Bragg spots were observed up to 2.3 Å resolution, with individual data sets evaluated for initial quality to determine merging resolution (Table S1). To improve quality and statistics of the overall data set, data was merged from both instruments to yield a data set to be sufficient for refinement and structure determination up to a resolution of 2.75 Å. Details about the data statistics and processing are given in Tables 1 and 2.

Table 1.

Data processing and merging statistics PDB ID 7M75 7M78 7M76.

| Beamline | LCLS/MFX + SwissFEL/Bernina | SACLA/BL2 | PAL XFEL/NCI |

|---|---|---|---|

| Resolution range refined (Å) | 56.71–2.75 | 31.63–3.00 | 25.23–3.00 |

| Resolution range upper bin (Å) | (2.79–2.75) | (3.05–3.00) | (3.05–3.00) |

| Wavelength (Å) | 1.306 | 1.181 | 1.277 |

| Space group | P63 | P63 | P63 |

| Unit cell parameters (Å) |

a = 285.4 ± 0.3 b = 285.4 ± 0.3 c = 166.5 ± 0.3 |

a = 284.9 ± 1.4 b = 284.9 ± 1.4 c = 166.2 ± 1.4 |

a = 284.3 ± 0.3 b = 284.3 ± 0.3 c = 165.8 ± 0.4 |

| Lattices merged | 143,459 | 22,560 | 5901 |

| Unique reflections | 199,647 | 152,883 | 147,785 |

| (upper bin) | (9949) | (7619) | (7378) |

| Completeness | 99.98% | 99.9% | 100% |

| (upper bin) | (99.88%) | (100%) | (100%) |

| CC1/2 | 99.8% | 89.3% | 90.4% |

| (upper bin) | (13.5%) | (9.8%) | (3.1%) |

| Multiplicity | 506.39 | 282.5 | 32.0 |

| (upper bin) | (9.84) | (62.31) | (12.71) |

| I/σBr19(I)## | 3.6 | 3.2 | 1.3 |

| (upper bin) | (0.2) | (0.9) | (0.3) |

##: as defined in [Brewster 2019]79.

Table 2.

Refinement statistics PDB ID 7M75 7M78 7M76.

| Beamline | LCLS/MFX + SwissFEL/Bernina | SACLA/BL2 | PAL XFEL/NCI |

|---|---|---|---|

| Wilson B-factor | 68.4 | 41.1 | 74.5 |

| R-factor | 26.4% | 33.4% | 26.8% |

| R-free | 27.9% | 34.9% | 27.8% |

| Number of atoms | 48,898 | 48,799 | 48,799 |

| Number non-hydrogen atoms | 24,512 | 24,413 | 24,413 |

| Ligands | 14,127 | 14,127 | 14,127 |

| Waters | 119 | 20 | 20 |

| Protein residues | 2244 | 2244 | 2244 |

| RMS (bonds) | 0.006 | 0.003 | 0.006 |

| RMS (angles) | 0.991 | 0.66 | 1.08 |

| Ramachandran favored | 91.61% | 93.5% | 90.7 |

| Ramachandran outliers | 0.09% | 0.05% | 0.09% |

| Clashscore | 15.5 | 7.5 | 14.8 |

| Average B-factor | 87.3 | 51.7 | 77.2 |

In light of the recent report of an XFEL-based PS I structure from crystals in the space group P2129, instead of the P63 reported for the earlier structures1, we decided to thoroughly investigate the unit cell of our present PS I crystals. We obtained publicly archived raw data from the Coherent X-ray Imaging Database (CXIDB deposit 111) for the monoclinic structure reported by Gisriel et al.29. Ten runs (167–176) were reanalyzed as follows: The archived and our working data sets were compared by indexing runs starting with the lattice parameters of the P21 structure (a = 279.1, b = 164.6, c = 284.1, beta = 119.25). Unit cells were refined on a per-crystal basis and histograms of the refined lattice parameters were constructed. Consistent with the previous report, the combined histograms for the a and c axes for the CXIDB 111 data form a bimodal distribution with maxima at 281.0 and 286.2 Å. In contrast, the corresponding histogram for our present data is unimodal with a maximum at 285.0 Å (Fig. S3). The refined beta angles are centered on 119.3°. for the CXIDB 111 data and on 119.9°. for the present data. Thus, our sample matches the hexagonal isoform in P63 with a symmetric PS I trimer and not the monoclinic isoform in P21. A single particle cryo-EM study38 recently demonstrated the threefold molecular symmetry of our PS I, which is a necessary (but not sufficient) condition for P63 crystallographic symmetry. We conclude that crystallization may occur in a hexagonal isoform with molecular threefold symmetry (Jordan 20011 and present work) or in a monoclinic isoform with molecular pseudo-threefold symmetry (Gisriel 2019)29.

Examples for assessing the quality of our data can be seen in Fig. 2, where the electron density for some selected regions of the protein is shown. The quality is as expected for a data set at 2.75 Å resolution and allows modeling of amino acid side chains and cofactor details. The quality of the electron density map was also of sufficient quality to model 4 additional lipids (e.g. Fig. S5) compared to the cryogenic structure. We modeled all 96 chlorophylls present in the cryogenic structure (1JB0) but we note that the chlorophyll in PsaM was modelled in a slightly different position compared to 1JB0 and has weak density allowing for alternative ligands to be modeled into this site.

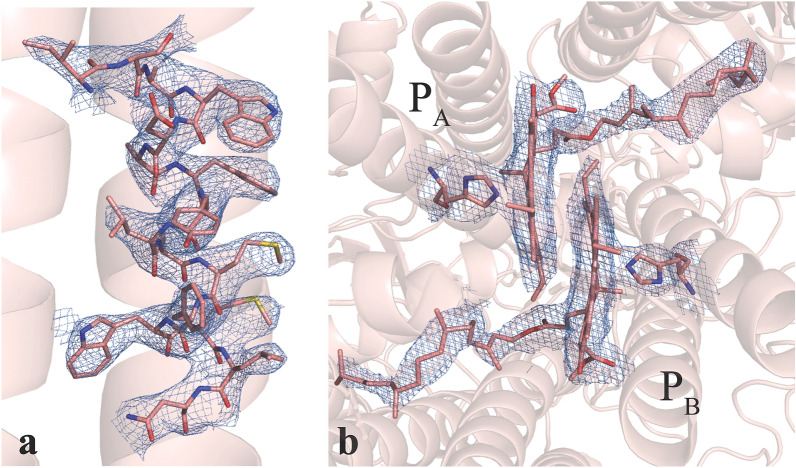

Figure 2.

Electron density of selected regions of the PS I protein complex derived from the 2.75 Å resolution room temperature diffraction data. (a) A portion of a transmembrane alpha-helix (PsaB576–PsaB591) with side chains modeled into 2Fobs − Fcalc electron density contoured to 1.5 . Side chains are clearly visible in this region of the map. (b) Electron density in the region of the special pair P700 formed by a Chl a (labeled PB) and a Chl a’ (labeled PA). Mg2+ coordinating His residues and the Chls are shown as sticks, the 2Fobs − Fcalc electron density is shown as blue mesh contoured at 1.5 . Figure generated with Pymol v. 2.4.0a0, https://pymol.org.

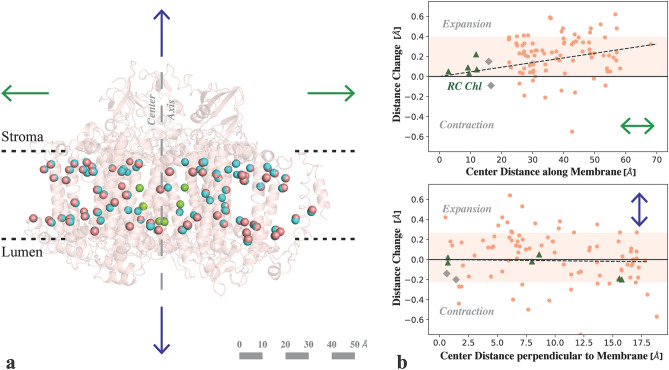

At a first glance the overall structure is very similar to the reported cryogenic structure of PSI reported by Jordan et al.1 (RMSD = 0.488 Å for C-α atoms). Yet upon closer inspection clear differences were observed. A small but reproducible expansion along the membrane plane of the overall structure is visible in the RT structure compared to the cryogenic structure, along with an expanded unit cell (a = 285.3, b = 285.3, c = 166.5). The radius of gyration of the monomer increases from 40.8 Å in the cryo-structure to 41.3 Å in the XFEL structure, and that of the trimer from 68.2 Å (cryo) to 68.7 Å (XFEL) (Fig. S1). The changes in the distance from the chlorophylls to the center between P700 and FX are illustrated in Fig. 3. The average expansion at RT is 0.2 Å along the membrane plane with a gradual increase of about 0.05 Å per 10 Å (Fig. 3b top, dotted line). In contrast, distances perpendicular to the membrane show no average change (Fig. 3b, bottom). The expansion of the protein affects the distances between the antenna chlorophylls, and between the antenna and the core. Interestingly, no clear effect on the proposed connecting Chl (shown in grey in Fig. 3b) is visible. Cofactors involved in the electron transport, which is directed perpendicular to the membrane, are only marginally affected (eCA/B1-3 highlighted in green). Two separate RT data sets of PS I were collected the SACLA XFEL facility in Japan and in the presence of ascorbate at the PAL XFEL facility in Korea, and structural models were refined into these data sets to 3.0 Å resolution (Tables 1 and 2). In these independent experiments the PS I complex showed a similar expansion along the membrane plane when compared to the cryogenic structure (Fig. S4).

Figure 3.

Comparison of Chl positions in PS I between cryogenic and RT structure. (a) A representation of the central Mg2+ (salmon spheres) of all Chls in one monomer of the PS I RT structure (with backbone shown schematically in salmon) overlaid with the Mg2+ positions from the cryogenic structure (blue). View is along the membrane plane with the stromal side on top and lumenal side on bottom. The center axis, passing through FX and P700 is indicated by a long-dashed line. (b) Distance change (RT minus cryo) of the chlorophylls to the center between P700 and FX either along the membrane (top) or perpendicular to it (bottom). Positive values represent expansion, negative contraction at room temperature. The 1-σ region around the average is highlighted. The Chls involved in charge separation are marked as green triangles, the closest two Chls of the antenna as gray diamonds. The room temperature structure shows an average expansion by about 0.2 Å along the membrane plane. The distance change perpendicular to the membrane is distributed symmetrically around the zero line. Figure generated with Pymol v. 2.4.0a0, https://pymol.org, Python v. 3.7.6, Matplotlib 3.2.1, https://matplotlib.org.

The positions of the uncharged glycolipid and negatively charged phospholipid located near the A branch and B branch respectively, closely match what was observed in previous cryogenic structures. The asymmetry these lipids introduce near the reaction center may influence electron transfer rates, however we cannot assign any interpretable changes under physiological conditions at the current resolution.

Cofactor environment

Although most binding pockets for the central cofactors of the electron transfer chain were found to be unchanged by the difference in temperature, upon careful comparison between the cryogenic structure (1JB0)1 and the highest quality 2.7 Å resolution XFEL structure collected at RT, some subtle but distinct differences were noticed. The most prominent differences were seen in the environment of the phylloquinones in both the A and the B branch, that may have implications for the directionality of electron transfer. Residues PsaA-Phe689 and PsaB-Phe669, which are immediately next to the phylloquinones PhQA and PhQB respectively, shift in position along with a twist in the orientation of the phylloquinones, with some atomic positions changing greater than 1.0 Å (Fig. 4).

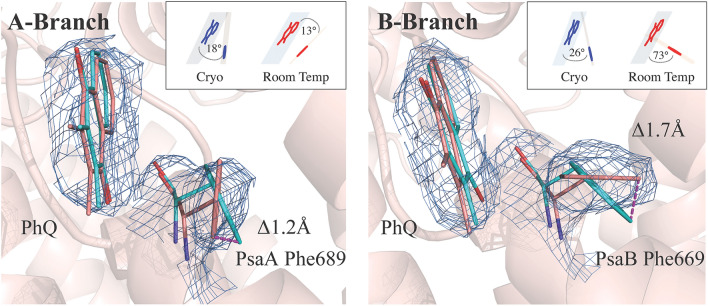

Figure 4.

2Fobs − Fcalc electron density contoured to 1.5 with the modeled phylloquinone in the PsaA and PsaB electron transport pathways. For aromatic residues PsaA-Trp697 and PsaA-Phe689 of PsaA and PsaB-Trp677 and PsaB-Phe669 of PsaB (salmon) the orientation obtained from the cryogenic structure (1JB0) is overlaid in cyan. PsaA-Phe689 is twisted relative to the cryogenic structure to a more parallel orientation with the phylloquinone. The B site reveals PsaB-Phe669 in an orientation more perpendicular to the plane of the phylloquinone. The stick representation of the PsaB-Phe669 and PsaA-Phe689 aromatic ring plane angles to phylloquinone in room temperature structure versus 1JB0 is shown in the inset. Both sites reveal significant shifts of atomic coordinates. Figure generated with Pymol v. 2.4.0a0. https://pymol.org.

In order to exclude modeling errors several controls were performed. These include omit map generation (Fig. S6), repositioning PsaB-Phe669 in the cryogenic position and running systematic refinements of these phenylalanine residues in multiple rotated conformations in Phenix (Fig. S7), and Fobs − Fcalc map inspection. All of these controls indicated that side chain position of PsaB-Phe669 in the 2.75 Å resolution room temperature structure is different from the positions modeled in the cryogenic data.

The angle between the planes of the ring structures of the phenylalanines and the plane of the phylloquinones ring structures changes in the A-branch by 5° and becomes more parallel (13 ± 8° at RT), increasing the off-center π-stacking interaction and the distance to 3.9 Å. In contrast, PsaB-Phe669 rotates out of plane by 47° and becomes more perpendicular in the B branch (73 ± 6° at RT) with the distance reduced to 3.3 Å. The positional precision of these assignments was estimated by perturbation of the structure factors using END/RAPID39. This method allows us to assign coordinate error to individual atoms. In short, we randomly perturbed the structure factors by a factor in the range of ± [Fobs − Fmodel] in 100 trials, and re-refinement was carried out for each perturbed dataset. The standard deviation of aromatic plane angles was obtained from this set of 100 structures, confirming our reported positions (Fig. S8). The two tryptophans PsaA-Trp697 and PsaB-Trp677 similarly pi-stacked to the phylloquinones are unchanged, with a distance of 3 Å and angles of 16° and 13° to the phylloquinones, respectively. Both the tryptophans and the phenylalanines are part of a network of aromatic side chains within π-interacting distance of 3.5–4.5 Å that spans from the antenna chlorophyll (1230, B-branch numbering) and its histidine ligand (PsaB-His718) via the Phe, PhQ Trp, and A0 to PsaB-Tyr676. Typical phenyl–phenyl interaction energies were reported to be in a similar range as H-bonding40.

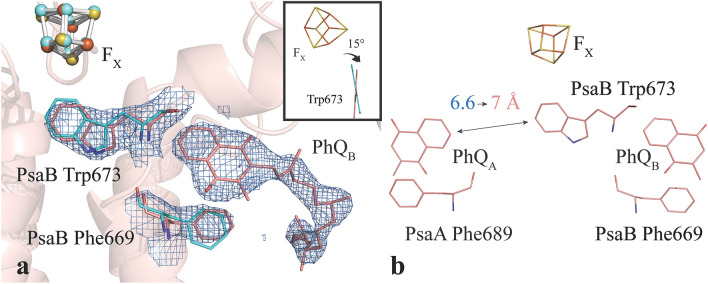

Another difference in the cofactor environment is observed in the B branch between PhQB and FX. The conformation of PsaB-Trp673 is twisted by 15° (Fig. 5a). In this orientation, the angle between the ring planes of Trp and PhQB is 50 ± 2° in the room temperature structure. Also, the distance of the PsaB-Trp673 to PhQA at 7 Å is longer in the room temperature structure (Fig. 5b, 6.6 Å in the cryo structure). Interestingly, this does not alter the distance of either quinone to FX.

Figure 5.

The upper part of the electron transfer chain in PS I. ( a) Upper B branch of the electron transfer pathway modeled into 2Fobs − Fcalc electron density contoured to 2 . Also shown are the aromatic amino acids PsaB-Trp673 and PsaB-Phe669 in proximity to the phylloquinone. The plane of Trp673 has twisted 15° relative to the cryogenic structure (inset). (b) Stick representation of the upper A and B branches of the reaction center including the [4Fe4S] cluster FX and the phylloquinones PhQA and PhQB. The distance of PhQA to the symmetry breaking PsaB-Trp673 is with 7 Å in the room temperature structure longer than the 6.6 Å in the cryo structure. The distance between FX and the quinones is not altered. Figure generated with Pymol v. 2.4.0a0. https://pymol.org.

Examination of the recent 2.9 Å structure of T. elongatus PS I collected at the European XFEL29 did not reveal the same structural changes we observed. This main aim of this study seems to be to demonstrate the feasibility of membrane bound protein data collection at the European XFEL and not much structural refinement of the PS I structure was described in the publication.

In order to lay the groundwork for future illumination driven experiments and probe for structural intermediates in the light-induced electron transfer chain of PS I, we devised a method to measure a PS I structure under conditions that will ensure fast re-reduction of P700 upon illumination. To this end, we treated PS I crystals with ascorbic acid (see Methods) and performed the RT XFEL measurements under dark conditions using the DOT setup installed at the NCI instrument of the PAL-XFEL41, 42. Diffraction data to 2.8 Å resolution were obtained and merged to a resolution of 3.0 Å (“dark/reduced’, see Table 1). This structure exhibited the same general expansion features as the 2.75 Å dark state structure without ascorbic acid present (Fig. S4) and no specific differences due to the ascorbate treatment were found.

Discussion

With the capabilities of XFELs, one can now conduct X-Ray Diffraction (XRD) studies under physiological conditions43, 44. In addition, the time structure of the XFELs allows one to perform time-resolved studies in time scales that are not accessible with other sources45. Recent time-resolved work at LCLS has included the study of many dynamic processes in proteins occur in the sub-ps and ps time scales46–48. A series of recent ~ 2.9 Å resolution SFX structures of a photosynthetic reaction center from B.virdis has revealed conformational response to various ultrafast time points, with positional shifts of up to 0.3 Å reported at the special pair49.

Room temperature XFEL studies have also reported differences in structures of protein complexes compared to data collected at cryogenic temperatures. Young et al. showed at ~ 3 Å resolution, that the dimeric complex in photosystem II is slightly extended (~ 0.5 Å) at room temperature compared to structures at cryogenic temperatures32. This expansion was pronounced along the membrane plane and less so perpendicular to the plane. We observe a similar trend in our room temperature PS I data from data collected at four different beamlines (LCLS, SwissFEL, SACLA, and PAL), on PS I crystals from different preparations, with a clear expansion along the membrane plane (Fig. 3 and S4) and only minimal changes perpendicular to the membrane.

One possible explanation discussed for this anisotropic expansion in our earlier study on PS II was that the lipid molecules that are bound inside the dimeric protein complex show higher mobility at room temperature compared to cryogenic temperatures32. In comparison to PS II the number of lipids located inside the studied PS I complex is smaller (four instead of 25 lipid molecules per monomer) (Fig. S9a). But in addition to the hydrophobic fatty acid tails, other aliphatic chains of molecules bound inside the protein complex should be taken into account. Counting the isoprenoid chains of Chls, pheophytins and quinones, as well as the hydrophobic chains of detergent molecules (which most likely replace native lipids) in addition to the fatty acid chains of lipids, an average of 3–4 chains per transmembrane helix (TMH) is found for both PS I and PS II (Fig. S9b).

When assuming the tilt of the TMH with respect to the membrane normal is not changing with temperature, the dominant factor determining the expansion of the PS I protein complex along the membrane normal is the thermal expansion of the hydrogen bonding interactions within each transmembrane alpha helix, and a thermal expansion coefficient of 2 * 10–4 K−1 was observed for these bonds50. For lipid bilayers, an increase of the area per molecule with increased temperature is commonly observed and this is attributed to the higher mobility of the fatty acid chains at higher temperature (see e.g.51–53). The thermal expansion coefficient of lipids in the lateral direction of the lipid bilayer was found to be about 2 * 10–2 K−153, substantially larger than the thermal expansion observed for H-bonding interactions in α-helices. Assuming that the aliphatic chains behave similarly, we therefore suggest that the thermal mobility of the 3–4 aliphatic units present for each TMH are responsible for the observed preferential thermal expansion of the complex in the membrane plane direction.

Although the resulting changes in Chl distances in PS I at room temperature versus the cryogenic structure are subtle, they should be considered when calculating exciton transfer rates within the antenna system and between the antenna and the RC of PS I at room temperature, because small changes in distances can have a large effect on the electron transfer rates. Importantly, the position of the connecting Chls between the internal antenna system and the reaction center were found to be unaffected by the change in temperature, suggesting that the overall coupling for excitation energy transfer is not strongly influenced by temperature. We also did not observe any changes in the proposed clusters of red-shifted Chls in PS I at room temperature (Fig. S10), indicating that the conclusions regarding the position of long-wavelength absorbing Chl in PS I54, 55 drawn based on the cryogenic structure are still valid at room temperature.

When inspecting individual binding pockets of the electron transfer cofactors in the A and B chains, no structural change around the six central chlorophyll molecules is observed between the cryogenic and the room temperature dark structures. This agrees well with a recent MD simulation predicting a very rigid local protein environment56. A major difference was found around the phylloquinones, which are within π-stacking distance to conserved Trp and Phe side chains in the A and B branches. The Trp side chains are offset-stacked with a distance of 3 Å and an angle of 16 and 13° relative to the quinone planes. When these Trp were mutated to Phe, the kinetics of A1— oxidation slowed down by a factor of 3–5 at the modified branch21. This was attributed to a modified π-stacking and a possible change of the local environment, such as the exposure to solvent. In purely electrostatic calculations the influence of π-stacking on the redox potential of the quinones was small (30 mV)57. In contrast, in a quantum chemical simulation of only the quinone head group and an indole, a larger shift of the quinone redox potential was found (50–150 mV)58. This shift may be overestimated without the dielectric screening effect of the protein environment57. In the quantum chemical study, it was also found that the electro-positive periphery of the tryptophan will try to reorient towards the quinone in its reduced state. If this is prevented by the protein environment, the parallel orientation will destabilize the semiquinone anion.

Here, we report a rotation in the aromatic rings of the phenylalanines PsaA-Phe689 and PsaB-Phe669 (Fig. 4). At a distance of 3.9 Å and 3.3 Å, the rings are within the typical range of interactions. Such a non-parallel orientation is a common observation rather than an exception40. A reorientation of the ring to 73 ± 6° in the B branch exposes the electropositive ring to the quinone ring and likely contributes to stabilizing the semiquinone anion state. Since the aromatic structure of phenylalanine is smaller and the interaction distance to phylloquinone larger than for the tryptophan, however, this semiquinone stabilization effect, and in turn the effect on the redox potential will be relatively small.

Given the expected magnitude and direction of the changes, the likely role of phenylalanine orientation to the redox properties is to compensate for the larger shift induced by more drastic structural differences between two branches. These larger structural changes include differences in the backbone twist, protonation state of residues, and residue identity itself, and are predicted to be responsible for ~ 100 mV difference in the PhQA and PhQB redox potentials59. As a result of these structural changes, the redox potentials of PhQA is positively shifted and is thermodynamically uphill to FX, while PhQB is negatively shifted and is thermodynamically downhill or isoenergetic to FX. Such shifts in redox potentials need to be regulated, however, such that forward electron transfer from A1 to FX is still favorable in both branches over the back reaction processes. Further increase in the PhQA potential induces P700+PhQA– recombination reaction60 and decreasing PhQB potential allows for a competition between A0 to A1 electron transfer and back reaction from A061. The orientation of phenylalanine at room temperature, which would offset the potentials to more negative/positive directions for PhQA/PhQB, respectively, may function as a mechanism to fine tune the redox properties to prevent such over-shifting. The observation presented here suggests that the two branches may be applying different redox tuning to A1 by using a conserved residue with similar backbone orientation.

In a FTIR study, it is also suggested that the redox potential difference between the quinones may stem from a stronger H-bonding of PhQA— vs PhQB—62. The above discussed rotation of PsaB-Phe669 to the reduced state stabilizing T-stacking, may weaken the PhQB H-bond at the opposite side. This is opposed to the parallel π-stacking at the A side where no counterforce to the H-bond will be developed, in line with the FTIR study. Albeit they are strictly conserved (Table S2), the phenylalanines have not been subject to many studies. The point mutation PsaA-Phe689Asn resulted in a ~ 100-fold decrease in the observed rate of PhQA— oxidation63. This extreme slowdown is unlikely to be caused by just a modification of the π-stacking. Instead, it highlights the structural importance of the two phenylalanine aromatic rings, their positioning close to the carbonyl oxygens of the quinones (shielding it from H-bonding with solvent), the binding affinity of phylloquinones and possibly their network of π-interactions including the antenna chlorophylls and A0.

As both PsaA-Phe689 and PsaB-Phe669 assume a more parallel orientation with PhQ in the cryogenic structure, the effect of redox tuning and on H-bonding strength for PhQB is likely diminished at lower temperatures. At cryogenic temperature, electron transfer in PS I becomes highly heterogeneous: a significant fraction of centers is only capable of undertaking incomplete electron transfer to PhQ or FX, and the fractions that achieves electron transfer to terminal acceptors are unable to recombine to the neutral ground state64. The heterogeneous and incomplete electron transfer processes indicate that cofactors and the surrounding environment are not necessarily frozen into the lowest energy configuration, but into multiple local minima that are unfavorable for performing efficient electron transfer (see discussions in65). Given the nature of PS I at different temperatures, the reoriented phenylalanine at cryogenic temperature does not imply that multiple conformers exist at room temperature and freezes into the low temperature structure. Rather, a likely scenario is that the reorientation is part of the structural changes that contribute to heterogeneity and impartial electron transfer. From the kinetic measurement, the rate of electron transfer through PhQB at cryogenic temperature is reported to be relatively temperature independent, but the fractional usage of the B branch is significantly diminished25, 66.

In addition to the phenylalanine, PsaB-Trp673 also rotates by 15° with respect to PhQB and the distance to PhQA is increased to 7 Å without changing the quinone-FX distance significantly (Fig. 5). For the angle between Trp673 and PhQB, an error of only 2.3° was found (Fig. S8). Assuming that the cryo structure is even better defined, a change of relative angle of 15° is clearly beyond this error estimate. A strong effect on the PhQB— reoxidation kinetics was found by time-resolved measurements when a point mutation is introduced to PsaB-Trp67367. This symmetry-breaking PsaB-Trp673 coordinates and separates two water clusters. Electrostatic calculations attributed the kinetic difference of the quinone oxidation to several factors associated with this residue and coordinated water molecules. The A branch counterpart to PsaB-Trp673 is PsaA-Gly693: a significant difference in the headgroup sizes induces a different twist to the backbone of these residues. This difference in twists orients a backbone carbonyl to the quinone in the B branch, and away from the quinone in the A branch. In addition, the water molecules bisected and coordinated by PsaB-Trp673 are within interacting distance with PsaB-Asp575. The carboxyl oxygens of PsaB-Asp575 are 3.3 and 2.8 Å from the closest water oxygen, and a theoretical study has predicted that the protonation state of PsaB-Asp575 influences the redox potential of PhQA by ~ 80 mV59. Recent FTIR studies have also shown that a mutation on PsaB-Trp673 disturbs the water cluster coordination, and results in protonation of phylloquinones68. However, at 2.75 Å resolution electron density may show ambiguity for water positions and highly mobile waters cannot be modelled accurately. Nonetheless, the observed increased distance between PsaB-Trp673 and PhQA will modify water positions in the cavity and the specific coordination of the water clusters on both sides of Trp673 is likely crucial to fine-tuning the redox potentials of the phylloquinones. Indeed, we find that the two water molecules that were involved in H-bonding interaction to the π-electrons of the tryptophan ring in the cryogenic structure are conserved in our RT structure and one of them is involved in the H-bonding network to PsaB-Asp575.

A comparison of structures from higher plant species such as Pisum sativum (pea)4, and cyanobacterial species such as Synechocystis sp PCC680369, and T. elongatus1, 38, all collected under cryogenic conditions, reveal that the positions of PsaA- Phe689, PsaB-Phe669 and PsaB-Trp673 are relatively conserved and slightly different compared to the positions observed in the room temperature structure (Fig. S11). At room temperature, the amino acid side chains might have more flexibility to adapt to a more favorable conformation to facilitate electron transfer across the membrane plane. Such conformational sampling is likely not possible at cryogenic temperatures; thus, the subtle but clear differences observed in proximity to the central cofactor network demonstrate the importance of room temperature measurements to provide a more physiologically relevant view of the reaction center environment.

Additionally, conditions established here describe data collection in the presence of ascorbic acid, which will aid in experiments to study the characteristics of specific reduced or oxidized electron transfer cofactors. Under these conditions the same structural changes at room temperature are found and confirm the above presented observations.

To summarize, the radiation damage-free room-temperature structure of PS I reveals that the overall membrane protein complex is slightly expanded along the membrane plane, compared to previous cryogenic measurements, and that specific differences of the aromatic side chains PsaA-Phe689, PsaB-Phe669, and PsaB-Trp673 exist in the binding pockets of the two phylloquinone electron acceptors in both branches. These structural differences can have direct consequences on the redox properties of these cofactors and could be partly responsible for the observed differences in electron transfer rates along the two branches. A combination of improvements in crystallization and data collection methods has allowed improving the resolution for time-resolved RT measurements of PS II from ~ 6 Å to close to 2.0 Å. This development, together with the already obtained initial data quality that has already been obtained for PS I presented here, is encouraging for future time-resolved studies that will allow us to elucidate the nature of protein-mediated electron transfer in PS I.

Methods

PS I preparation and crystallization

PS I was prepared as described previously70. BN-PAGE and MALDI-TOF revealed that PS I was in its trimeric state and no subunits were lost during the purification. Dynamic light scattering revealed a hydrodynamic radius of 9.4 nm and a polydisperity index of 5%. Crystal growth was analyzed in a range from 7 to 18 mM Na2SO4 (Fig. S12). To ensure high quality of the protein, purified PS I was pre-crystallized in 12 mM Na2SO4, 5 mM MES pH 6.0 and 0.02% dodecyl-β-D-maltoside (DDM), washed and stored in the form of a suspension of microcrystals at 4 °C. On the day of the diffraction measurement the microcrystals were dissolved in the same buffer containing 40 mM Na2SO4 and a final crystallization was performed by diluting the protein to a Chl concentration of 1 mM in 12 mM Na2SO4, 5 mM MES pH 6.0 and 0.02% DDM at room temperature. The crystals grew to a size of 15–25 µm within 15–20 min (Fig. S2). Crystal growth was stopped by tenfold dilution with a salt-free buffer (5 mM MES pH 6, 0.02% DDM). For the measurement at LCLS and SACLA, the crystals were directly used in the sample delivery system. For the measurement at PAL, the crystals were treated with 5 mM ascorbic acid and stored in the dark prior to data collection.

Sample delivery and data collection

SFX data were collected either at the MFX instrument36 of the LCLS facility (SLAC National Accelerator Lab, Menlo Park, CA), at the BERNINA instrument71 of the ARAMIS beamline at the SwissFEL FEL (Paul Scherrer Institut, Villigen, Switzerland)35, or at BL-2 EH3 of the SACLA XFEL facility at Hyogo, Japan72. In addition, data from crystals treated with ascorbic acid were measured at the NCI beamline of the PAL-XFEL facility in Pohang, Korea41. In all cases the suspension of microcrystals was kept in the dark while being delivered to a focusing acoustic transducer to form droplets of 4 nl as previously described33. The droplets were deposited on a kapton tape running at a speed of 300 mm/sec and traveled through a helium enclosure for 0.8 s before being probed by the X-ray pulse. The X-ray beam parameters for all three facilities are given in Table S1. For MFX diffraction data were detected at a rate of 10 Hz on a Rayonix MX 170HS detector with 2 × 2 binning at a distance of 205 mm from the interaction point. At the SwissFEL a 16 Mpixel Jungfrau detector placed at a distance of 163 mm was read out at 25 Hz. At SACLA diffraction data were recorded on an MPCCD octal detector at a rate of 30 Hz and at PAL on a Rayonix MX 225HS with a 3 × 3 binning at 145 mm distance at 15 Hz.

Data processing, model building and map calculation

Data were processed using cctbx.xfel and DIALS73–75. cctbx.xfel74, 76, 77 was custom built for NERSC using instructions here: https://gitlab.com/NERSC/lcls-software/-/tree/beamtime-2020-09/cctbx-production. Note that the branch referenced is specific to this beamtime. The data was batched by timestamp, and joint refinement of the crystal models against the detector position for each batch was performed to account for small time-dependent variations in detector position74. Integrated intensities were corrected for the kapton tape shadow as described in Fuller et al.33. Data from LCLS and SwissFEL were co-scaled and merged using cctbx.xfel.merge with errors determined by the method of Evans as described by Brewster et al.78, 79. https://gitlab.com/NERSC/lcls-software/-/tree/beamtime-2020-09/cctbx-production.

Indexing solutions for serial crystallographic data in the merohedral space group P63 are inherently ambiguous; this ambiguity was resolved by an implementation in the cctbx.xfel.merge processing pipeline of the algorithm of Brehm and Diederichs80, supported by coset decomposition as described by Gildea and Winter81. The full Gildea-Winter algorithm has N2M2 complexity; i.e. correlations are computed between every pair of shots after transforming by every candidate reindexing operator. For 100,000 shots in P63, this requires computing ~ 4 × 1010 correlation coefficients, which is an intractable problem with current technology. We reduced the algorithmic complexity to NM2 by splitting the data into tranches of 200–300 shots for clustering analysis; these tranches were distributed across MPI ranks for multiprocessing; and were constructed with overlapping subsets of shots, so that tranch results could be reconciled at the conclusion. When the computation is performed on 400 tranches of 250 shots, a total of ~ 108 correlation coefficients are needed, a 400 × reduction in the problem size. Merging was performed on several hundred MPI ranks and the total time was typically < 10 min per data set. A full usage guide for this method (implemented as a cctbx.xfel.merge worker) is available. https://github.com/cctbx/cctbx_project/blob/master/xfel/merging/application/modify/README.md.

A multistep approach was used to determine resolution cutoffs82, where for each separate image and lattice, assessment of the outer resolution bin for detectable spot intensities was conducted. Bragg spot intensities I and standard deviations σ(I) for one lattice were obtained using standard 2D summation integration. Final resolution cutoff for the merged data set was quantified using CC1/283, with the resolution limit upper bin being defined by the point where CC1/2 no longer decreases monotonically, indicating no useful information is obtained beyond this point.

Molecular replacement was carried out using Phaser-MR84 within the Phenix package85 using the deposited cryogenic structure 1JB01 as a reference model. Model building was performed in Coot86 with multiple iterations of refinement using phenix.refine85, 87, 88. Waters lacking clear density were removed from the 2.75 Å LCLS/SwissFEL structure, and all waters not coordinated to ions were removed from the lower resolution structures. Restraints were generated using elbow89 within the phenix package with some modifications, and custom restraints were constructed for the special pair chlorophyll designated “chlorophyll a epimer” which is labeled PA in these structures. Fobs − Fobs and Fcalc − Fcalc maps were generated using the isomorphous difference map tool phenix.fobs_minus_fobs_map within the Phenix package. Data statistics can be found in Table 1.

Coordinate error estimation

To estimate the positional precision of individual cofactors and side chains, we used END/RAPID to perturb the structure factors, as previously employed39, 82. The structure factors were adjusted by ± |Fobs − Fmodel| in 100 trials using the END/RAPID command line tools (https://bl831.als.lbl.gov/END/RAPID/end.rapid/Documentation/end.rapid.Manual.htm), adding noise proportional to the error in the model to generate 100 perturbed datasets for each illumination state. We then re-refined the models against each new dataset, kicking the initial atom positions in the model using the sites.shaketool in Phenix before refinement. The mean and standard deviation of selected bond distances and angles were calculated across the re-refined models82.

Supplementary Information

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by the Director, Office of Science, Office of Basic Energy Sciences (OBES), Division of Chemical Sciences, Geosciences, and Biosciences (CSGB) of the Department of Energy (DOE) for Ultrafast XFEL crystallography studies of charge separation in photosynthetic reaction centers (J.K.), and for X-ray spectroscopy and crystallography methodology and instrumentation (J.Y., V.K.Y.). National Institutes of Health (NIH) provides funding through Grants GM126289 (J.K.) and GM110501 (J.Y.) for instrumentation development for XFEL experiments, GM055302 (V.K.Y.) for biochemistry support, and GM117126 (N.K.S.) for development of computational protocols for analyzing XFEL data. Funding from Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft (DFG, German Research Foundation) under Germany´s Excellence Strategy—EXC 2008/1—390540038 (A.Z.), Sfb1078 (Humboldt Universität Berlin) TP A5 (A.Z., M.I., R.H.) is acknowledged. A.K., A.Z. and S.S. gratefully acknowledge the support of this research by the Bundesministerium für Bildung und Forschung (BMBF), Germany, 2020+, projects 031B0557 A+B, and Vetenskapsrådet 2016-05183 (J.M.) is also gratefully acknowledged. XFEL data was collected under proposal PO58 at LCLS/SLAC, Stanford, under proposal 2018B8089 at SACLA, Japan, under proposal 20190996 at SwissFEL, Switzerland, and under proposal 2019-1st-NCI-033 at PAL-XFEL, Korea. This work was supported by the Global Science Experimental Data Hub Center (GSDC) for data computing and the Korea Research Environment Open NETwork (KREONET) for network service provided by the Korea Institute of Science and Technology Information (KISTI). Use of the LCLS, SLAC National Accelerator Laboratory, is supported by the U.S. DOE, Office of Science, OBES under Contract No. DE-AC02-76SF00515. We thank the support staff at LCLS/SLAC, SACLA, SwissFEL and PAL-XFEL.

Author contributions

S.M.K., A.K., P.S.S., R.C., S.K.S., R.H., M.I., I.S.K., I.B., C.C.P., F.D.F., S.G., C.d.L., P.C., M.H.C., J.M., N.K.S., V.K.Y., J.Y., A.Z., J.Kern performed the experiment; A.K., R.C., S.K.S., R.H., M.I., prepared samples; S.M.K., M.D., D.P., L.L., K.D.S., A.B., I.D.Y., J.P.B., A.S.B., N.K.S., processed data; S.M.K., A.K., P.S.S., M.D., H.M., D.P., L.L., N.W.M., N.K.S., J.Kern analyzed data; D.P., A.B., D.O., K.N., A.S.B., N.K.S., contributed new analytical tools; S.P., G.P., J.Kim, S.J.L., J.P., K.T., S.O., M.S.H., A.B., R.O., M.S., S.Z., D.O., K.N., H.L., R.M. operated the beam lines; V.K.Y., J.Y., A.Z., J.Kern designed the experiment; S.M.K., A.K., P.S.S., M.D., H.M., V.K.Y., J.Y., A.Z., JKern wrote the manuscript with input from all authors.

Data availability

Structure coordinates and structure factors for the LCLS/SwissFel, PAL, and SACLA PS I data sets have been deposited in the Protein Data Bank under accession codes 7M75, 7M76 and 7M78 respectively.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher's note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

These authors contributed equally: Stephen M. Keable, Adrian Kölsch and Philipp S. Simon.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1038/s41598-021-00236-3.

References

- 1.Jordan P, et al. Three-dimensional structure of cyanobacterial photosystem I at 2.5 A resolution. Nature. 2001;411:909–917. doi: 10.1038/35082000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ben-Shem A, Frolow F, Nelson N. Crystal structure of plant photosystem I. Nature. 2003;426:630–635. doi: 10.1038/nature02200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Amunts A, Drory O, Nelson N. The structure of a plant photosystem I supercomplex at 3.4 A resolution. Nature. 2007;447:58–63. doi: 10.1038/nature05687. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Mazor Y, Borovikova A, Caspy I, Nelson N. Structure of the plant photosystem I supercomplex at 26 A resolution. Nat. Plants. 2017;3:17014. doi: 10.1038/nplants.2017.14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Antoshvili M, Caspy I, Hippler M, Nelson N. Structure and function of photosystem I in Cyanidioschyzon merolae. Photosynth. Res. 2019;139:499–508. doi: 10.1007/s11120-018-0501-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Su X, et al. Antenna arrangement and energy transfer pathways of a green algal photosystem-I-LHCI supercomplex. Nat. Plants. 2019;5:273–281. doi: 10.1038/s41477-019-0380-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Krauss N, et al. 3-Dimensional structure of system-I of photosynthesis at 6 angstrom resolution. Nature. 1993;361:326–331. doi: 10.1038/361326a0. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Krauss N, et al. Photosystem I at 4 A resolution represents the first structural model of a joint photosynthetic reaction centre and core antenna system. Nat. Struct. Biol. 1996;3:965–973. doi: 10.1038/nsb1196-965. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Schubert WD, et al. Photosystem I of Synechococcus elongatus at 4 A resolution: Comprehensive structure analysis. J. Mol. Biol. 1997;272:741–769. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.1997.1269. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Schubert WD, et al. A common ancestor for oxygenic and anoxygenic photosynthetic systems: A comparison based on the structural model of photosystem I. J. Mol. Biol. 1998;280:297–314. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.1998.1824. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Molotokaite E, et al. Trapping dynamics in photosystem I-light harvesting complex I of higher plants is governed by the competition between excited state diffusion from low energy states and photochemical charge separation. J. Phys. Chem. B. 2017;121:9816–9830. doi: 10.1021/acs.jpcb.7b07064. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Cherepanov DA, et al. Mechanism of adiabatic primary electron transfer in photosystem I: Femtosecond spectroscopy upon excitation of reaction center in the far-red edge of the QY band. Biochim. Biophys. Acta Bioenerg. 1858;895–905:2017. doi: 10.1016/j.bbabio.2017.08.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Muller MG, Slavov C, Luthra R, Redding KE, Holzwarth AR. Independent initiation of primary electron transfer in the two branches of the photosystem I reaction center. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U S A. 2010;107:4123–4128. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0905407107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Di Donato M, Stahl AD, van Stokkum IH, van Grondelle R, Groot ML. Cofactors involved in light-driven charge separation in photosystem I identified by subpicosecond infrared spectroscopy. Biochemistry. 2011;50:480–490. doi: 10.1021/bi101565w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Zamzam N, Kaucikas M, Nürnberg DJ, Rutherford AW, van Thor JJ. Femtosecond infrared spectroscopy of chlorophyll f-containing photosystem I. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 2019;21:1224–1234. doi: 10.1039/c8cp05627g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kurashov V, et al. Critical evaluation of electron transfer kinetics in P700-FA/FB, P700-FX, and P700–A1 photosystem I core complexes in liquid and in trehalose glass. Biochim. Biophys. Acta Bioenerg. 1859;1288–1301:2018. doi: 10.1016/j.bbabio.2018.09.367. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Fromme P, Bottin H, Krauss N, Setif P. Crystallization and electron paramagnetic resonance characterization of the complex of photosystem I with its natural electron acceptor ferredoxin. Biophys. J. 2002;83:1760–1773. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(02)73942-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kubota-Kawai H, et al. X-ray structure of an asymmetrical trimeric ferredoxin-photosystem I complex. Nat. Plants. 2018;4:218–224. doi: 10.1038/s41477-018-0130-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Perez-Boerema A, et al. Structure of a minimal photosystem I from the green alga Dunaliella salina. Nat. Plants. 2020;6:321–327. doi: 10.1038/s41477-020-0611-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Chapman HN, et al. Femtosecond X-ray protein nanocrystallography. Nature. 2011;470:73–77. doi: 10.1038/nature09750. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Guergova-Kuras M, Boudreaux B, Joliot A, Joliot P, Redding K. Evidence for two active branches for electron transfer in photosystem I. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U S A. 2001;98:4437–4442. doi: 10.1073/pnas.081078898. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.McConnell MD, et al. Species-dependent alteration of electron transfer in the early stages of charge stabilization in photosystem I. Biochim. Biophys. Acta. 1847;429–440:2015. doi: 10.1016/j.bbabio.2015.01.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Santabarbara S, et al. Directionality of electron-transfer reactions in photosystem I of prokaryotes: Universality of the bidirectional electron-transfer model. J. Phys. Chem. B. 2010;114:15158–15171. doi: 10.1021/jp1044018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Poluektov OG, Utschig LM. Directionality of electron transfer in type I reaction center proteins: High-frequency EPR study of PS I with removed iron-sulfur centers. J. Phys. Chem. B. 2015;119:13771–13776. doi: 10.1021/acs.jpcb.5b04063. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Makita H, Hastings G. Directionality of electron transfer in cyanobacterial photosystem I at 298 and 77K. FEBS Lett. 2015;589:1412–1417. doi: 10.1016/j.febslet.2015.04.048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Neutze R, Wouts R, van der Spoel D, Weckert E, Hajdu J. Potential for biomolecular imaging with femtosecond X-ray pulses. Nature. 2000;406:752–757. doi: 10.1038/35021099. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Neutze R. Opportunities and challenges for time-resolved studies of protein structural dynamics at X-ray free-electron lasers. Philos. R Trans. Soc. Lond. B Biol. Sci. 2014;369:20130318. doi: 10.1098/rstb.2013.0318. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Schlichting I. Serial femtosecond crystallography: The first five years. IUCrJ. 2015;2:246–255. doi: 10.1107/S205225251402702X. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Gisriel C, et al. Membrane protein megahertz crystallography at the European XFEL. Nat. Commun. 2019;10:5021. doi: 10.1038/s41467-019-12955-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Fraser JS, et al. Accessing protein conformational ensembles using room-temperature X-ray crystallography. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U S A. 2011;108:16247–16252. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1111325108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Park JH, et al. Non-cryogenic structure and dynamics of HIV-1 integrase catalytic core domain by X-ray free-electron lasers. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2019;20:1943. doi: 10.3390/ijms20081943. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Young ID, et al. Structure of photosystem II and substrate binding at room temperature. Nature. 2016;540:453–457. doi: 10.1038/nature20161. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Fuller FD, et al. Drop-on-demand sample delivery for studying biocatalysts in action at X-ray free-electron lasers. Nat. Methods. 2017;14:443–449. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.4195. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Emma P, et al. First lasing and operation of an Ångstrom-wavelength free-electron laser. Nat. Photonics. 2010;4:641–647. doi: 10.1038/nphoton.2010.176. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Prat E, et al. A compact and cost-effective hard X-ray free-electron laser driven by a high-brightness and low-energy electron beam. Nat. Photonics. 2020;14:748–754. doi: 10.1038/s41566-020-00712-8. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Sierra RG, et al. The macromolecular femtosecond crystallography instrument at the linac coherent light source. J. Synchrotron. Radiat. 2019;26:346–357. doi: 10.1107/S1600577519001577. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Sauter NK. XFEL diffraction: Developing processing methods to optimize data quality. J. Synchrotron. Radiat. 2015;22:239–248. doi: 10.1107/S1600577514028203. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Kölsch A, et al. Current limits of structural biology: The transient interaction between cytochrome c6 and photosystem I. Curr. Res. Struct. Biol. 2020;2:171–179. doi: 10.1016/j.crstbi.2020.08.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Lang PT, Holton JM, Fraser JS, Alber T. Protein structural ensembles are revealed by redefining X-ray electron density noise. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U S A. 2014;111:237–242. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1302823110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Hunter CA, Lawson KR, Perkins J, Urch CJ. Aromatic interactions. J. Chem. Soc. Perkin Trans. 2001;2:651–669. doi: 10.1039/B008495F. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Kang HS, et al. Hard X-ray free-electron laser with femtosecond-scale timing jitter. Nat. Photonics. 2017;11:708–713. doi: 10.1038/s41566-017-0029-8. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Park J, Kim S, Nam K-H, Kim B, Ko IS. Current status of the CXI beamline at the PAL-XFEL. J. Korean Phys. Soc. 2016;69:1089–1093. doi: 10.3938/jkps.69.1089. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Keedy DA, et al. Mapping the conformational landscape of a dynamic enzyme by multitemperature and XFEL crystallography. Elife. 2015 doi: 10.7554/eLife.07574. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Kern J, et al. Simultaneous femtosecond X-ray spectroscopy and diffraction of photosystem II at room temperature. Science. 2013;340:491–495. doi: 10.1126/science.1234273. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Arnlund D, et al. Visualizing a protein quake with time-resolved X-ray scattering at a free-electron laser. Nat Methods. 2014;11:923–926. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.3067. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Levantino M, et al. Ultrafast myoglobin structural dynamics observed with an X-ray free-electron laser. Nat. Commun. 2015;6:6772. doi: 10.1038/ncomms7772. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Tenboer J, et al. Time-resolved serial crystallography captures high-resolution intermediates of photoactive yellow protein. Science. 2014;346:1242–1246. doi: 10.1126/science.1259357. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Barends TR, et al. Direct observation of ultrafast collective motions in CO myoglobin upon ligand dissociation. Science. 2015;350:445–450. doi: 10.1126/science.aac5492. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Dods R, et al. Ultrafast structural changes within a photosynthetic reaction centre. Nature. 2021;589:310–314. doi: 10.1038/s41586-020-3000-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Cordier F, Grzesiek S. Temperature-dependence of protein hydrogen bond properties as studied by high-resolution NMR11Edited by P. E. Wright. J. Mol. Biol. 2002;317:739–752. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.2002.5446. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Phillips MC, Graham DE, Hauser H. Lateral compressibility and penetration into phospholipid monolayers and bilayer membranes. Nature. 1975;254:154–156. doi: 10.1038/254154a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Petrache HI, Dodd SW, Brown MF. Area per lipid and acyl length distributions in fluid phosphatidylcholines determined by 2H NMR spectroscopy. Biophys. J. 2000;79:3172–3192. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(00)76551-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Kučerka N, Nieh M-P, Katsaras J. Fluid phase lipid areas and bilayer thicknesses of commonly used phosphatidylcholines as a function of temperature. Biochim. Biophys. Acta (BBA) Biomembr. 1808;2761–2771:2011. doi: 10.1016/j.bbamem.2011.07.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Croce R, van Amerongen H. Light-harvesting in photosystem I. Photosynth. Res. 2013;116:153–166. doi: 10.1007/s11120-013-9838-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Karapetyan NV, et al. Long-wavelength chlorophylls in photosystem I of cyanobacteria: Origin, localization, and functions. Biochem. (Mosc.) 2014;79:213–220. doi: 10.1134/s0006297914030067. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Milanovsky GE, Ptushenko VV, Golbeck JH, Semenov AY, Cherepanov DA. Molecular dynamics study of the primary charge separation reactions in photosystem I: Effect of the replacement of the axial ligands to the electron acceptor A(0) Biochim. Biophys. Acta. 1837;1472–1483:2014. doi: 10.1016/j.bbabio.2014.03.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Ishikita H, Knapp EW. Redox potential of quinones in both electron transfer branches of photosystem I. J. Biol. Chem. 2003;278:52002–52011. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M306434200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Kaupp M. The function of photosystem I. Quantum chemical insight into the role of tryptophan–quinone interactions. Biochemistry. 2002;41:2895–2900. doi: 10.1021/bi0159783. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Kawashima K, Ishikita H. Structural factors that alter the redox potential of quinones in cyanobacterial and plant photosystem I. Biochemistry. 2017;56:3019–3028. doi: 10.1021/acs.biochem.7b00082. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Makita H, Hastings G. Modeling electron transfer in photosystem I. Biochim. Biophys. Acta (BBA) Bioenerg. 2016;1857:723–733. doi: 10.1016/j.bbabio.2016.03.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Pushkar YN, Karyagina I, Stehlik D, Brown S, van der Est A. Recruitment of a foreign quinone into the A1 Site of photosystem I: Consecutive forward electron transfer from A0 to A1 to FX with anthraquinone in the A1 site as studied by transient EPR*. J. Biol. Chem. 2005;280:12382–12390. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M412940200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Makita H, Rohani L, Zhao N, Hastings G. Quinones in the A(1) binding site in photosystem I studied using time-resolved FTIR difference spectroscopy. Biochim. Biophys. Acta Bioenerg. 1858;804–813:2017. doi: 10.1016/j.bbabio.2017.06.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Santabarbara S, Bullock B, Rappaport F, Redding KE. Controlling electron transfer between the two cofactor chains of photosystem I by the redox state of one of their components. Biophys. J. 2015;108:1537–1547. doi: 10.1016/j.bpj.2015.01.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Schlodder E, Falkenberg K, Gergeleit M, Brettel K. Temperature dependence of forward and reverse electron transfer from A1-, the reduced secondary electron acceptor in photosystem I. Biochemistry. 1998;37:9466–9476. doi: 10.1021/bi973182r. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Brettel K. Electron transfer and arrangement of the redox cofactors in photosystem I. Biochim. Biophys. Acta (BBA) Bioenerg. 1997;1318:322–373. doi: 10.1016/S0005-2728(96)00112-0. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Agalarov R, Brettel K. Temperature dependence of biphasic forward electron transfer from the phylloquinone(s) A1 in photosystem I: Only the slower phase is activated. Biochim. Biophys. Acta (BBA) Bioenerg. 2003;1604:7–12. doi: 10.1016/S0005-2728(03)00024-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Ali K, Santabarbara S, Heathcote P, Evans MC, Purton S. Bidirectional electron transfer in photosystem I: Replacement of the symmetry-breaking tryptophan close to the PsaB-bound phylloquinone A1B with a glycine residue alters the redox properties of A1B and blocks forward electron transfer at cryogenic temperatures. Biochim. Biophys. Acta. 2006;1757:1623–1633. doi: 10.1016/j.bbabio.2006.07.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Agarwala N, Makita H, Luo L, Xu W, Hastings G. Reversible inhibition and reactivation of electron transfer in photosystem I. Photosynth. Res. 2020;145:97–109. doi: 10.1007/s11120-020-00760-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Malavath T, Caspy I, Netzer-El SY, Klaiman D, Nelson N. Structure and function of wild-type and subunit-depleted photosystem I in synechocystis. Biochim. Biophys. Acta Bioenerg. 1859;645–654:2018. doi: 10.1016/j.bbabio.2018.02.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Kölsch A, et al. Insights into the binding behavior of native and non-native cytochromes to photosystem I from Thermosynechococcus elongatus. J. Biol. Chem. 2018;293:9090–9100. doi: 10.1074/jbc.RA117.000953. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Ingold G, et al. Experimental station Bernina at SwissFEL: Condensed matter physics on femtosecond time scales investigated by X-ray diffraction and spectroscopic methods. J. Synchrotron Radiat. 2019;26:874–886. doi: 10.1107/S160057751900331X. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Tono K, et al. Beamline, experimental stations and photon beam diagnostics for the hard x-ray free electron laser of SACLA. N. J. Phys. 2013;15:083025. doi: 10.1088/1367-2630/15/8/083035. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Winter G, et al. DIALS: Implementation and evaluation of a new integration package. Acta Crystallogr. D. 2018;74:85–97. doi: 10.1107/s2059798317017235. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Brewster AS, et al. Improving signal strength in serial crystallography with DIALS geometry refinement. Acta Crystallogr. D Struct. Biol. 2018;74:877–894. doi: 10.1107/S2059798318009191. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Brewster AS, Young ID, Lyubimov A, Bhowmick A, Sauter NK. Processing serial crystallpgrahpic data from XFELs or synchrotrons using the cctbx.xfel GUI. Comp. Cryst. Newsl. 2019;10:22–39. [Google Scholar]

- 76.Sauter NK, Hattne J, Grosse-Kunstleve RW, Echols N. New python-based methods for data processing. Acta Crystallogr. D Biol. Crystallogr. 2013;69:1274–1282. doi: 10.1107/S0907444913000863. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Brewster, A. S. Scripts and documentation for Brewster et. al. 2018.https://github.com/phyy-nx/dials_refinement_brewster2018 (2018).

- 78.Evans PR. An introduction to data reduction: Space-group determination, scaling and intensity statistics. Acta Crystallogr. D Biol. Crystallogr. 2011;67:282–292. doi: 10.1107/S090744491003982X. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Brewster AS, et al. SAD phasing of XFEL data depends critically on the error model. Acta Crystallogr. D Struct. Biol. 2019;75:959–968. doi: 10.1107/S2059798319012877. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Brehm W, Diederichs K. Breaking the indexing ambiguity in serial crystallography. Acta Crystallogr. D Biol. Crystallogr. 2014;70:101–109. doi: 10.1107/S1399004713025431. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Gildea RJ, Winter G. Determination of Patterson group symmetry from sparse multi-crystal data sets in the presence of an indexing ambiguity. Acta Crystallogr. D Struct. Biol. 2018;74:405–410. doi: 10.1107/s2059798318002978. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Ibrahim M, et al. Untangling the sequence of events during the S2 → S3 transition in photosystem II and implications for the water oxidation mechanism. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U S A. 2020;117:12624–12635. doi: 10.1073/pnas.2000529117. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Hattne J, et al. Accurate macromolecular structures using minimal measurements from X-ray free-electron lasers. Nat. Methods. 2014;11:545–548. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.2887. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.McCoy AJ, et al. Phaser crystallographic software. J. Appl. Crystallogr. 2007;40:658–674. doi: 10.1107/S0021889807021206. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Liebschner D, et al. Macromolecular structure determination using X-rays, neutrons and electrons: Recent developments in Phenix. Acta Crystallog. D Struct. Biol. 2019;75:861–877. doi: 10.1107/s2059798319011471. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Emsley P, Lohkamp B, Scott WG, Cowtan K. Features and development of Coot. Acta Cryst. D. 2010;66:486–501. doi: 10.1107/S0907444910007493. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Adams PD, et al. PHENIX: A comprehensive Python-based system for macromolecular structure solution. Acta Crystallogr. D. 2010;66:213–221. doi: 10.1107/S0907444909052925. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Afonine PV, et al. Towards automated crystallographic structure refinement with phenix.refine. Acta Crystallogr. D Biol. Crystallogr. 2012;68:352–367. doi: 10.1107/S0907444912001308. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Moriarty NW, Grosse-Kunstleve RW, Adams PD. electronic Ligand Builder and Optimization Workbench (eLBOW): A tool for ligand coordinate and restraint generation. Acta Crystallogr. D Biol. Crystallogr. 2009;65:1074–1080. doi: 10.1107/S0907444909029436. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

Structure coordinates and structure factors for the LCLS/SwissFel, PAL, and SACLA PS I data sets have been deposited in the Protein Data Bank under accession codes 7M75, 7M76 and 7M78 respectively.