Abstract

It is commonly assumed that the horizontal transfer of most bacterial chromosomal genes is limited, in contrast to the frequent transfer observed for typical mobile genetic elements. However, this view has been recently challenged by the discovery of lateral transduction in Staphylococcus aureus, where temperate phages can drive the transfer of large chromosomal regions at extremely high frequencies. Here, we analyse previously published as well as new datasets to compare horizontal gene transfer rates mediated by different mechanisms in S. aureus and Salmonella enterica. We find that the horizontal transfer of core chromosomal genes via lateral transduction can be more efficient than the transfer of classical mobile genetic elements via conjugation or generalized transduction. These results raise questions about our definition of mobile genetic elements, and the potential roles played by lateral transduction in bacterial evolution.

Subject terms: Genome evolution, Mobile elements, Bacterial genetics, Bacteriophages

It is commonly thought that horizontal transfer of most bacterial chromosomal genes is limited, in comparison with the frequent transfer of mobile genetic elements. Humphrey et al. show that, actually, phage-mediated lateral transduction of core chromosomal genes can be more efficient than the transfer of mobile genetic elements via conjugation or generalized transduction.

Introduction

It has been classically assumed that the mobility of the bacterial chromosome is limited, in contraposition to that observed for the different members of the ‘mobilome’. The mobilome is the umbrella term used to group all of the mobile genetic elements (MGEs) contained within a cell, with members typically falling within three main categories: plasmids, phages and phage-like elements, and transposable elements1. Many clinically and environmentally relevant bacteria harbour plasmids, transposable elements, prophages, and phage satellite elements for the efficient shuffling of genetic material between compatible cells. Conjugation is the main process by which plasmids are transferred intercellularly, and all plasmids can be broadly categorised as conjugative, mobilisable or non-transmissible2. Conjugative plasmids encode the mobilisation machinery that is necessary for their transfer to a new recipient cell2. In fact, the conjugative machinery has commonly been held to be the dominant mechanism by which horizontal gene transfer (HGT) is achieved3. Mobilisable plasmids are not capable of initiating conjugation on their own, but they can be mobilised by hijacking the machinery of conjugative plasmids2. Mobilisable and non-transmissible plasmids can be also mobilised in the lab via phage-mediated generalised transduction4,5, although the impact of this in nature remains to be determined. Not just plasmids, but also integrative conjugative elements (ICEs) or conjugative transposons use conjugation for their self-transfer6. Plasmids, ICEs and transposons contribute to bacterial genomic diversity through the carriage of accessory and antibiotic-resistance genes6,7. ICEs and transposons can also affect gene expression through insertional inactivation or by altering promoter activity, depending on the manner in which they insert into the bacterial genome1.

Phages and their counterparts, the phage-inducible chromosomal islands (PICIs)8–10 are also key components of the mobilome and are important mediators of HGT. These elements readily transmit between host bacteria, where they can integrate into the bacterial chromosome and replicate passively during cell division. As new residents of a host cell, they can offer lysogenic immunity against phage superinfection or they can bestow important virulence phenotypes by introducing genes for toxins and colonisation factors11,12. In addition to mobilising their own DNA, phages can also mediate the exchange of bacterial DNA at very low frequencies through the processes of specialised and generalised transduction (ST and GT). Specialised transducing particles transmit restricted parts of the host chromosome, and they are formed by irregular prophage excision events that result in hybrid phage genomes that include bacterial DNA adjacent to phage attachment sites13,14. GT can transmit any bacterial DNA, and it occurs when host DNA is packaged into capsids at the expense of phage DNA to form transducing particles that inject their DNA cargo into a new host cell, where it can recombine into the host chromosome or exist as a plasmid13,15. GT is primarily mediated by pac-type phages, which package DNA by the headful mechanism. DNA packaging into transducing particles is initiated by the phage small terminase (TerS) at pseudo-pac (ppac) sites, which are sequences that resemble phage pac sites. These motifs are scattered throughout bacterial chromosomal and plasmid DNA and are recognised with varying frequencies that reflect their level of homology with bone fide pac sites13.

While the mobilome seemed to be well defined, the broader concept of genetic mobility in bacteria is no longer well defined, as it has recently been upended by the discovery of the third and most powerful mode of phage-mediated DNA transfer: lateral transduction (LT)16. The LT mechanism begins with early in situ prophage replication, which creates multiple integrated prophages for genomic redundancy. Some prophages excise and enter the productive lytic cycle, while others serve as substrates for in situ DNA packaging from their embedded pac sites, which are recognised far more efficiently than ppac sites (used in GT). When the first headful of DNA has been reached, the processive terminase enzyme continues to fill many more capsids with bacterial chromosome, which are subsequently transferred at high frequencies16 (Fig. 1) and can then be integrated into the recipient genome by homologous recombination (HR). We propose here that when the full impact of this mechanism is considered, the classical dichotomy of portable MGEs and immobile chromosomes will no longer hold true because chromosomal genes can be mobilised at frequencies equal to or higher than elements normally regarded as mobile. To explore this idea, we looked to Staphylococcus aureus and Salmonella spp. as our reference organisms because their MGEs have been widely studied and they serve as model organisms for the mechanism of LT. We show that, via phage-mediated lateral transduction, the mobility of core genes in bacterial chromosomes can exceed that of elements classically considered to be mobile.

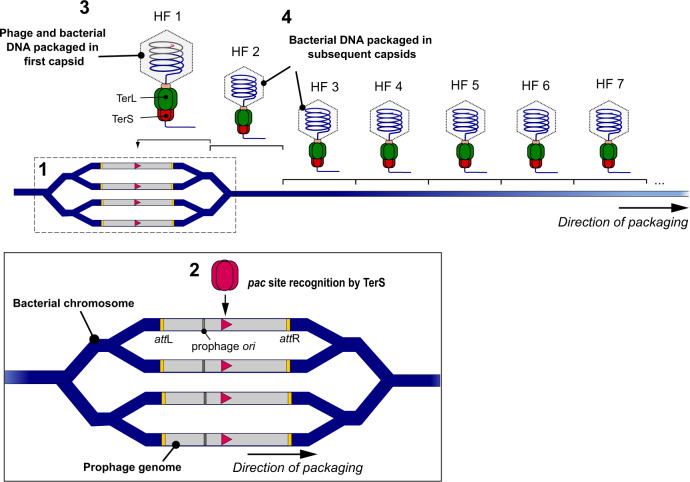

Fig. 1. Lateral transduction of chromosomal DNA.

LT is initiated during the early stages of prophage activation with the prophage remaining integrated in the bacterial chromosome. The mechanism commences with bidirectional in situ replication of the integrated prophage from the phage ori, generating multiple copies of the integrated phage and surrounding bacterial chromosome [1]. Some prophages subsequently excise from the chromosome to generate progeny via the lytic cycle, but in those that remain integrated, the phage small terminase subunit (TerS) recognises the embedded pac site (pink triangle) within the prophage sequence, forming a complex for delivery of the DNA to the large terminase (TerL) subunit [2]. The TerS:DNA complex associates with the large terminase (TerL) subunit, which cleaves and translocates the DNA into available phage capsids until capacity (one headful) is reached, with the initial capsid containing a mixture of phage and chromosomal DNA [3]. When the capsid is filled, the DNA is cleaved once more and the Terminase:DNA complex associates with a new empty capsid to resume the packaging process, generating many processive headfuls containing bacterial chromosomes for subsequent transduction [4].

Results and discussion

Comparison of horizontal transfer rates

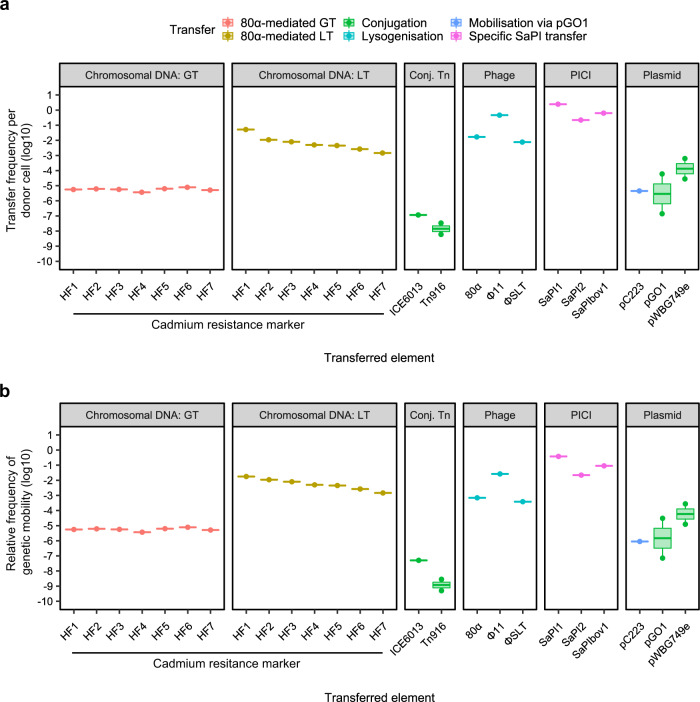

A comparison of the many S. aureus mobilome elements revealed striking differences in their horizontal transfer frequencies. The staphylococcal pathogenicity islands (SaPIs), the prototypical members of the PICI family8–10, mobilised themselves at rates at least 1000-fold higher than any plasmid or transposable element (Fig. 2a, Table 1), showing that PICIs are exquisitely adapted for maximising their own transfer between host cells. Notably, SaPI1 transduced between cells at very high frequency, with the equivalent of at least two successful transfer events (TE) occurring from each bacterial donor cell. Similarly, phage φSLT exhibited an efficient lysogenisation rate (integration into the recipient strain) of approximately 1 lysogen produced from 130 donor cells (Fig. 2a, Table 1). In order to extend our analysis to include more staphylococcal phages, we also tested the transfer rates of phages 80α and ϕ11 (Fig. 2a, Tables 1 and 2), which achieved lysogenisation rates in the range of approximately 1 lysogen from 62 donor cells and 1 lysogen from 2 donor cells, respectively, indicating the efficiency of transfer by these elements and highlighting the role played by phages in generating extensive bacterial diversity in nature. Note that we have compared lysogenisation rates here and not plaque formation because the latter does not provide any extra gene to the recipient cells, which incidentally will die at the end of the infective process. Interestingly, despite variance between the different conjugative and mobilisable plasmids, the transfer frequencies were considerably lower than those of the phages and SaPIs for all of the plasmids analysed but were higher than those of the conjugative transposons (Fig. 2a, Table 1). These data highlight that while all of these elements are considered to be mobile, there can be extreme differences in their relative transfer efficiencies. As expected, based on the classical dichotomy of MGEs vs the immobile chromosome, 80α-mediated GT transferred the chromosomally-encoded cadmium-resistance (CadR) markers at significantly lower frequencies than the transfer of the phage itself. Unexpectedly, the transfer frequencies of the CadR markers by GT were comparable to the range reported for the conjugative plasmids and were higher than those reported for the conjugative transposons, suggesting that DNA mobilisation by GT may not be as rare an event as typically assumed. Furthermore, this observation was reinforced when we compared the transfer rate of the ‘non-mobilisable’ plasmid pJP2511 via 80α or φ11-mediated generalised transduction (Table 2), with pJP2511 GT transfer efficiencies exceeding those reported for the classically mobile conjugative and mobilisable plasmids analysed (Fig. 2a, Table 1), lending weight to the importance of the role of GT in driving lineage diversification via horizontal gene transfer. Critically, 80α-mediated LT transferred the same CadR markers at substantially higher efficiencies than those reported for the other elements (Fig. 2a, Table 1), excepting phage and SaPI transfer, with a transfer efficiency of the first phage headful achieving a similar level of efficiency (5.18 × 10−2 events/donor) to that observed for the phage itself (1.69 × 10−2 events/donor).

Fig. 2. Genetic mobility via different mechanisms in S. aureus.

a Transfer frequencies per donor cell and b relative frequency of genetic mobility (defined as transfer frequency × cargo capacity) of different genetic elements by transfer type. Transfer of chromosomal DNA by phage 80α via generalised (GT) or lateral (LT) transduction of a cadmium resistance marker located at defined distances from the phage attachment site, conjugative transposons (Conj. Tn), phages, PICIs and plasmids. Data were extracted from literature or acquired through experimentation (see Table 1 for details).

Table 1.

Genetic mobility via different mechanisms in S. aureus.

| Accession | DNA transferred | HGT mechanism | Transfer frequency (TE/donor CFU)a | Source for transfer frequency data | Cargo capacity rateb | Relative frequency of genetic mobilityc | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mobilome component | |||||||

| Plasmids | |||||||

| pGO1 | NC_012547 | Plasmid | Conjugation | 6.0 × 10−5 to 1.4 × 10-7 | 42,43 | 0.51 (28/55) | 3.05 × 10−5 to 7.13 × 10-8 |

| pAM387 | Plasmid | Conjugation | 1.1 × 10-6 | 44 | ND | ND | |

| pWBG749e | Plasmid | Conjugation | 6.25 × 10−4 to 2.8 × 10−5 | 45 | 0.44 (23/52) | 2.76 × 10−4 to 1.24 × 10-5 | |

| pC223 | NC_005243 | Plasmid | Mobilisation via pGO1 | 4.5 × 10−6 | 42,46 | 0.20 (1/5) | 9.00 × 10−7 |

| Phage and PICI elements | |||||||

| ϕSLT | AB045978.2 | Phage | Lysogenisation | 7.69 × 10−3 | 47 | 0.05 (3/60) | 3.85 × 10−4 |

| 80α | NC_009526 | Phage | Lysogenisation | 1.69 × 10−2 | This work | 0.04 (3/73) | 6.95 × 10-4 |

| ϕ11 | AF424781 | Phage | Lysogenisation | 4.62 × 10−1 | This work | 0.06 (3/53) | 2.62 × 10-2 |

| SaPI1 | U93688.2 | PICI | Specific SaPI transfer | 2.46 | 26 | 0.15 (4/26) | 3.78 × 10−1 |

| SaPIbov1 | AF217235.1 | PICI | Specific SaPI transfer | 6.31 × 10−1 | 26 | 0.14 (3/21) | 9.01 × 10−2 |

| SaPI2 | EF010993 | PICI | Specific SaPI transfer | 2.20 × 10−1 | 26 | 0.04 (2/24) | 2.20 × 10−2 |

| Transposons—ICEs | |||||||

| ICE6013 | PRJNA360134 (strain DAR6247) | Conjugative Tn | Conjugation | 1.16 × 10−7 | 48 | 0.44 (7/16) | 5.08 × 10−8 |

| Tn916 | U09422 | Conjugative Tn | Conjugation | 6.0 × 10−9 to 3.4 × 10−8 | 49 | 0.08 (2/24) | 5.00 × 10−10 to 6.25 × 10-11 |

| Chromosomal transfer | |||||||

| Generalised transduction | |||||||

| CadR marker HF1d | NC_007795.1 | Chromosomal DNA | 80α-mediated GT | 5.58 × 10−6 | 16 | 1.00 (47/47)e | 5.58 × 10−6 |

| CadR marker HF3 | Chromosomal DNA | 80α-mediated GT | 5.69 × 10−6 | 16 | 1.00 (39/39) | 5.69 × 10−6 | |

| CadR marker HF5 | Chromosomal DNA | 80α-mediated GT | 6.31 × 10−6 | 16 | 1.00 (40/40) | 6.31 × 10−6 | |

| CadR marker HF7 | Chromosomal DNA | 80α-mediated GT | 5.12 × 10−6 | 16 | 1.00 (41.5/41.5) | 5.12 × 10−6 | |

| Lateral transduction | |||||||

| CadR marker HF1 | NC_007795.1 | Chromosomal DNA | 80α-mediated LT | 5.18 × 10−2 | 16 | 0.34 (17.5/51)f | 1.78 × 10−2 |

| CadR marker HF3 | Chromosomal DNA | 80α-mediated LT | 8.00 × 10−3 | 16 | 1.00 (39/39) | 8.00 × 10−3 | |

| CadR marker HF5 | Chromosomal DNA | 80α-mediated LT | 4.51 × 10−3 | 16 | 1.00 (40/40) | 4.51 × 10−3 | |

| CadR marker HF7 | Chromosomal DNA | 80α-mediated LT | 1.45 × 10−3 | 16 | 1.00 (41.5/41.5) | 1.45 × 10−3 | |

ND not determined.

Source data are provided as a Source Data file.

aIn order to enable comparisons between conjugation and the other modes of horizontal gene transfer, transfer frequency of phage- and PICI-mediated DNA transfer was re-analysed as transfer events (TE) per bacterial donor cell at the time of prophage induction: TE per donor cell = Transductant Units (TrU) per ml/6.5 × 107 CFU per ml. TrU per ml data were obtained from the sources indicated. Lysogens were induced at OD540 0.15, which is equivalent to 6.5 × 107 CFU per ml in the donor population.

bCargo capacity rate = number of accessory ORFs utilisable by the host cell (e.g. virulence factors and AMR genes)/total ORFs contained within the mobilised DNA sequence. Bracketed values indicate the number of accessory ORFs/total ORFs for each element where sequence data was available for analysis. For the purposes of this analysis, these staphylococcal phages are proposed to carry three ORFs with lysogenic conversion effects (e.g. toxins or phage-resistance mechanisms), while SaPIs carry 2–4 ORFs conferring enhanced virulence characteristics for the lysogenic host.

cRelative frequency of genetic mobility = transfer frequency × cargo capacity rate.

dHF, phage headful (~45 kb); numbers denote the distance of each cadmium marker from the phage chromosomal attachment site in terms of headful units in the direction of phage packaging.

eEstimation of ORFs packaged in HF1 during generalised transduction if packaging terminates in the same location as for HF1 during lateral transduction. No phage genes are expected to be transduced during generalised transduction of the DNA sequence containing the cadmium resistance marker, so 100% of the transferred sequence is available for recombination and utilisation by the recipient cell.

fThe total number of accessory ORFs utilisable by the recipient host cell is only a proportion of the total sequence transferred by HF1 because part of the phage genome is also packaged in the first headful during lateral transduction.

Table 2.

Transfer rates of phages, plasmids and chromosomal markers.

| Phage titre (PFU per ml) | Phage transfer (lysogenisation) | Chromosome transfer (phage-mediated lateral transduction) | Plasmid pJP2511 transfer (phage-mediated generalised transduction) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Strain | Mean (±SD) | Mean transduction titre (TrU/ml; ±SD) | Transfer frequency (TE/donor)a | Mean transduction titre (TrU/ml; ±SD) | Transfer frequency (TE/donor) | Mean transduction titre (TrU/ml; ±SD) | Transfer frequency (TE/donor) |

| Staphylococcus aureus | |||||||

| JP20844 (φ11) | 6.00 × 108 (±1.83 × 108) | 3.00 × 107 (±2.31 × 107) | 4.62 × 10−1 | 5.00 × 105 (±1.15 × 104) | 7.69 × 10−3 | 2.00 × 105 (±1.15 × 105) | 3.08 × 10−3 |

| JP20846 (80α) | 1.15 × 109 (±7.23 × 108) | 1.10 × 106 (±6.16 × 105) | 1.69 × 10−2 | 3.25 × 105 (±2.63 × 105) | 5.00 × 10−3 | 5.50 × 104 ( ± 5.77 × 103) | 8.46 × 10−4 |

| Salmonella Typhimurium | |||||||

| JP22210 (P22) | 2.03 × 108 (±1.10 × 108) | 1.57 × 108 (±8.33 × 107) | 1.567 | ND | ND | ND | ND |

ND not determined.

Source data are provided as a Source Data file.

Data are the mean values of four (φ11 and 80α) or three (P22) independent experiments.

aTE, transfer events. TE per donor cell = transductant units (TrU) per ml/6.5 × 107 CFU per ml for S. aureus phages, or transductant units (TrU) per ml/1.0 × 108 CFU per ml for S. Typhimurium phage P22.

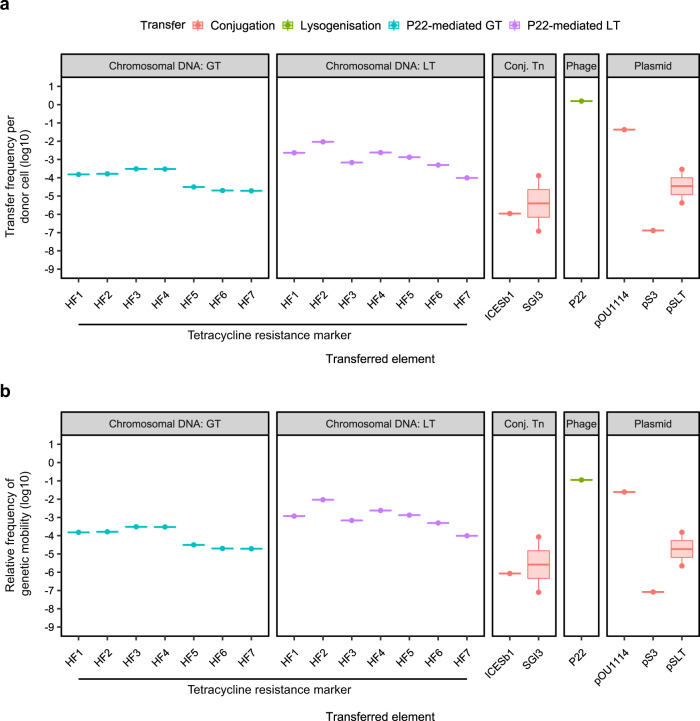

Since the previous results completely challenged our concept of DNA mobility, we decided to include an additional species to validate this paradigm change. A parallel analysis of mobilome components in Salmonella revealed that phage P22 is exquisitely well-adapted for transfer between cells, with approximately 1.57 new lysogens produced for every donor cell-induced (Fig. 3a, Table 3). Interestingly, this analysis also revealed considerably more variation in the transfer frequency rates of Salmonella conjugative plasmids than was observed for their Gram-positive counterparts (Fig. 3a, Table 3). Transfer of the Salmonella conjugative plasmid pOU1114 appeared to be highly efficient, with 1 transconjugant produced from approximately 23 donor cells, making it the second most mobile element examined in the Salmonella panel. In contrast, however, the remaining Salmonella conjugative plasmids had transfer frequencies in the range 10−8–10−4 TE per donor, which was similar to the range of transfer frequencies observed for the two Salmonella ICEs analysed (Fig. 3a, Table 3). Notably, similarly to that observed in S. aureus, P22-mediated GT of chromosomally encoded tetracycline-resistance (tetR) markers had transfer frequencies greater than or equivalent to the range reported for the conjugative plasmids and ICEs, excepting pOU1114. Importantly, the transfer frequency of tetR markers by P22-mediated LT was again higher than that observed for all except one of the classical MGEs analysed (Fig. 3a, Table 3), indicating that LT in this species, and to a lesser extent GT: (i) challenge the concept of what represents an MGE, and (ii) represent important pathways for efficient genetic exchange in both Gram-positive and Gram-negative organisms.

Fig. 3. Genetic mobility via different mechanisms in Salmonella spp.

a Transfer frequencies per donor cell and b relative frequency of genetic mobility (defined as transfer frequency × cargo capacity) of different genetic elements by transfer type. Transfer of chromosomal DNA by phage P22 via generalised (GT) or lateral (LT) transduction of a tetracycline resistance marker located at defined distances from the phage attachment site, conjugative transposons (Conj. Tn), phages and plasmids. Data were extracted from literature or acquired through experimentation (see Table 3 for details).

Table 3.

Genetic mobility via different mechanisms in Salmonella spp.

| Accession | DNA transferred | HGT mechanism | Transfer frequency (TE/donor CFU)a | Source for transfer frequency data | Cargo capacity rateb | Relative frequency of genetic mobilityc | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mobilome component | |||||||

| Plasmids | |||||||

| pSLT | CP001362 | Plasmid | Conjugation | 4.20 × 10−6 to 2.90 × 10-4 | 50 | 0.53 (54/102) | 2.22 × 10−6 to 1.54 × 10−4 |

| pS3 | Plasmid | Conjugation | 1.30 × 10−7 | 51 | 0.63 (52/82) | 8.24 × 10−8 | |

| pOU1114 | DQ115387 | Plasmid | Conjugation | 4.30 × 10−2 | 52 | 0.57 (27/47) | 2.47 × 10−2 |

| pESI | Plasmid | Conjugation | 4.00 × 10−6 | 53 | ND | ND | |

| pWW012 | CP022169 | Plasmid | Conjugation | 1.20 × 10−6 | 54 | ND | ND |

| Phage | |||||||

| P22 | Phage | Lysogenisation | 1.57 | This work | 0.07 (5/70) | 1.12 × 10−1 | |

| Transposable elements—ICEs | |||||||

| ICESb1 | FN298494.1 | Conjugative Tn | Conjugation | 1.10 × 10−6 | 55 | 0.77 (81/105) | 8.49 × 10−7 |

| SGI3 | Conjugative Tn | Conjugation | 1.20 × 10−7 to 1.30 × 10−4 | 56 | 0.66 (57/86) | 7.95 × 10−8 to 8.62 × 10−5 | |

| Chromosomal transfer | |||||||

| Generalised transduction | |||||||

| tetA marker HF1d | AE006468.2 | Chromosomal DNA | P22-mediated GT | 1.52 × 10−4 | 17 | 1.00 (41/41)e | 1.52 × 10−4 |

| tetA marker HF2 | Chromosomal DNA | P22-mediated GT | 1.64 × 10−4 | 17 | 1.00 (33.5/33.5) | 1.64 × 10−4 | |

| tetA marker HF3 | Chromosomal DNA | P22-mediated GT | 3.07 × 10−4 | 17 | 1.00 (44/44) | 3.07 × 10−4 | |

| tetA marker HF4 | Chromosomal DNA | P22-mediated GT | 3.00 × 10−4 | 17 | 1.00 (37/37) | 3.00 × 10−4 | |

| tetA marker HF5 | Chromosomal DNA | P22-mediated GT | 3.13 × 10−5 | 17 | 1.00 (42/42) | 3.13 × 10−5 | |

| tetA marker HF6 | Chromosomal DNA | P22-mediated GT | 2.00 × 10−5 | 17 | 1.00 (43/43) | 2.00 × 10−5 | |

| tetA marker HF7 | Chromosomal DNA | P22-mediated GT | 1.93 × 10−5 | 17 | 1.00 (43/43) | 1.93 × 10−5 | |

| Lateral transduction | |||||||

| tetA marker HF1 | AE006468.2 | Chromosomal DNA | P22-mediated LT | 2.33 × 10−3 | 17 | 0.51 (21.5/42.5) | 1.18 × 10−3 |

| tetA marker HF2 | Chromosomal DNA | P22-mediated LT | 9.27 × 10−3 | 17 | 1.00 (33.5/33.5) | 9.27 × 10−3 | |

| tetA marker HF3 | Chromosomal DNA | P22-mediated LT | 6.83 × 10−4 | 17 | 1.00 (44/44) | 6.83 × 10−4 | |

| tetA marker HF4 | Chromosomal DNA | P22-mediated LT | 2.40 × 10−3 | 17 | 1.00 (37/37) | 2.40 × 10−3 | |

| tetA marker HF5 | Chromosomal DNA | P22-mediated LT | 1.33 × 10−3 | 17 | 1.00 (42/42) | 1.33 × 10−3 | |

| tetA marker HF6 | Chromosomal DNA | P22-mediated LT | 4.97 × 10−4 | 17 | 1.00 (43/43) | 4.97 × 10−4 | |

| tetA marker HF7 | Chromosomal DNA | P22-mediated LT | 9.87 × 10−5 | 17 | 1.00 (43/43) | 9.87 × 10−5 | |

ND not determined.

Source data are provided as a Source Data file.

aIn order to enable comparisons between conjugation and the other modes of horizontal gene transfer, transfer frequency of phage-mediated DNA transfer was analysed as transfer events (TE) per bacterial donor cell at the time of prophage induction: TE per donor cell = Transductant Units (TrU) per ml/1.0 × 108 CFU per ml. TrU per ml data was obtained from the sources indicated. Lysogens were induced at OD600 0.2, which is equivalent to 1.0 × 108 CFU per ml in the donor population.

bCargo capacity rate = Number of accessory ORFs utilisable by the host cell (e.g., virulence factors, AMR genes and HPs)/total ORFs contained within the mobilised DNA sequence. Bracketed values indicate the number of accessories ORFs/total ORFs for each element where sequence data was available for analysis. Phage P22 is proposed to carry five ORFs with lysogenic conversion effects: sieAB and gtrABC.

cRelative frequency of genetic mobility = transfer frequency × cargo capacity rate.

dHF, phage headful (43.8 kb); numbers denote the distance of each tetracycline-resistance marker from the phage chromosomal attachment site in terms of headful units in the direction of phage packaging.

eEstimation of ORFs packaged in HF1 during generalised transduction if packaging terminates in the same location as for HF1 during lateral transduction. No phage genes are expected to be transduced during generalised transduction of the DNA sequence containing the tetracycline-resistance marker, so 100% of the transferred sequence is available for recombination and utilisation by the recipient cell.

fThe total number of accessory ORFs utilisable by the recipient host cell is only a proportion of the total sequence transferred by HF1 because part of the phage genome is also packaged in the first headful during lateral transduction.

Cargo carriage by MGEs: benefit or burden?

Having established that chromosomal genes can be mobilised at higher frequencies than many (if not most) classical MGEs, we then considered the relative contribution of each element to gene exchange in terms of the quantity of potential ‘useful’ DNA transferred (the cargo capacity). Importantly, though phages and SaPIs transduce at extremely high frequencies, they typically carry four or fewer genes of overt benefit to their host bacterium8,12. Plasmids vary widely in terms of size and hence their cargo capacity also varies considerably, and though clearly larger conjugative plasmids have substantially higher potential cargo capacity than that of SaPIs and phages, they are severely limited by having to encode all of the necessary genes for conjugative transfer without exceeding the metabolic capacity of their host cell. Arguably, owing to the fact that LT and GT package chromosomal DNA into empty phage capsids for transfer without requiring any capacity for replicative function, the cargo capacity of LT or GT virions is maximised. Indeed, when the overall genetic mobility rate (transfer frequency × cargo capacity) is compared for each element in S. aureus (Fig. 2b, Table 1), it is striking that in our analysis the efficiency of LT exceeds that of all other elements excepting only the SaPIs and ϕ11, which exhibit incredibly efficient transfer rates of accessory genes between donor and recipient strains despite their relatively low cargo capacities. In Salmonella, the rate of overall genetic mobility for LT exceeded that of the conjugative plasmids pSLT and pS3, and conjugative elements ICESb1 and SGI3 (Fig. 3b, Table 3), indicating that transfer of the chromosome is at least equal to, if not more efficient than, transfer of elements classically considered to be ‘mobile’.

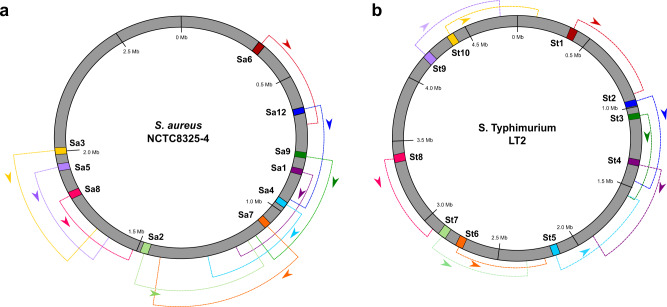

Importantly, in the case of lateral transduction by phage 80α each capsid can accommodate approximately 45–46 kb of chromosomal DNA, with highly efficient packaging of DNA occurring up to seven or more headfuls away from the phage integration site in the direction of packaging, implicating the potential for a single prophage to transfer up to 315 kb of bacterial DNA by LT16. Similarly, P22-mediated lateral transduction has been demonstrated up to 12 headfuls away from the phage integration site17, with each individual P22 capsid being capable of accommodating ~43–44 kb of chromosomal DNA, indicating that P22-mediated LT has the potential to efficiently mobilise at least 516 kb of bacterial DNA from a single prophage. This alone is impressive in its potential for gene exchange, but the prospective magnitude for chromosomal mobilisation is brought sharply into focus when considering the chromosomal architecture of phage attachment sites in S. aureus and S. enterica. The distribution and orientation of ten commonly used attB sites in the S. aureus chromosome are arranged in such a way that a poly-lysogenic strain could potentially mobilise up to 1.7 Mb of DNA (approximately 60% of the S. aureus chromosome) via LT in a single lytic event, presenting an astonishing potential for widespread horizontal gene exchange (Fig. 4a). A similar observation can be made for S. Typhimurium strain LT2, with poly-lysogeny offering the potential for transfer of up to 3.5 Mb of the bacterial chromosome in a single step (Fig. 4b). Together, these results indicate that phages offer highly efficient platforms for the transfer of significant portions of chromosomal DNA at rates higher than those of many other MGEs, indicating that through LT the bacterial chromosome becomes more mobile than many classical MGEs.

Fig. 4. Potential for extensive DNA transfer via lateral transduction is dictated by the distribution of prophage attachment sites in the bacterial chromosome.

Map of the chromosomes of S. aureus NCTC8325-4 (a) and S. Typhimurium LT2 (b) indicating the ten potential chromosomal attachment (attB) sites available for prophage integration. The packaging direction of an integrated prophage from each attB site is indicated by its corresponding colour-coded arrow, with the dashed regions representing a distance of approximately seven headfuls (one headful = ~45 kb for 80α) in S. aureus, or 12 headfuls (one headful = ~43 kb for P22) in S. Typhimurium from the attB site, which is the minimum distance known to be packaged by LT for each phage. a The distribution and directionality of attB sites in the S. aureus NCTC8325-4 chromosome indicates the potential for transfer of the entire region between ~0.31 and 2.0 Mb from a poly-lysogenic background, representing approximately 58% of the bacterial chromosome. Adapted from ref. 4. b The distribution and directionality of attB sites in S. Typhimurium LT2 indicates the potential for transfer of up to 3.5 Mb of chromosomal DNA from a poly-lysogenic background, representing approximately 72% of the bacterial chromosome. Source data are provided as a Source Data file.

Exploring the contribution of LT to virulence evolution

The scope and efficiency conferred by LT for the intercellular transfer of chromosomal genes raise questions over whether the bacterial chromosome itself could qualify as an MGE. MGEs are typically considered to be ‘selfish’ elements, promoting their own dissemination at the expense of other genetic elements in the cell. If we are to assume that parts of the bacterial chromosome itself behave akin to classical MGEs, we must also consider whether certain chromosomal loci also exhibit selfish interests for mediating their intercellular transmission. Classical MGEs are known to carry distinct genetic cargos that are enriched in genes that provide locally adaptive traits like toxin production, resistance, and virulence18,19, relative to the chromosome (as a whole). This is because those genes benefit (selfishly) from being able to move into new genetic backgrounds20,21. If parts of the chromosome are indeed hypermobile, theory suggests they should resemble MGEs in terms of gene content. In such cases, it would be expected that prophage-adjacent regions of the chromosome should indicate some enrichment in genes conferring a competitive advantage to the host cell, such as genes involved in virulence or environmental adaptation, relative to the rest of the chromosome. Examination of the chromosomal architecture of S. aureus and S. Typhimurium provides compelling circumstantial evidence that this may indeed be the case for several pathogenicity-associated genetic regions in each species (Table 4).

Table 4.

Examples of virulence-associated loci compatible with transfer via LT.

| S. aureus | Compatibility with prophage attachment (attB) sites for packaging by LTa | ||||||||||

| Locus | Contribution to virulenceb | Sa1 | Sa2 | Sa3 | Sa4 | Sa5 | Sa6 | Sa7 | Sa8 | Sa9 | Sa12 |

| vSaα | Lpl (induction of host inflammatory response) | HF 3 | |||||||||

| vSaβ | LukD, LukE, hysA (toxins) | HF 5-6 | HF 2-3 | HF 1-2 | |||||||

| vSaγ | Hla (toxin) | HF 7 | HF 4-5 | HF 2 | |||||||

| clfA | ClfA (adhesin) | HF 1 | HF 6 | ||||||||

| map | MHC class II analogue protein (immune evasion) | HF 1 | |||||||||

| SaPI Type I attB | SaPIpT1028, SaPI4 | HF 2 | |||||||||

| SaPI Type II attB | SaPIbov1 (TSST-1, Sel, Sek); SaPIbov2 (Bap); SaPIbov5 (Scin, vWbp) | HF 3 | |||||||||

| SaPI Type III attB |

SaPIm4 (FhuD); SaPImw2 (Ear, Seb, Sel, Sek); SaPI5 (Ear, Sek, Seq) |

HF 1 | HF 6 | ||||||||

| SaPI Type IV attB |

SaPI1 (TSST-1, Ear, Sek, Seq); SaPI3 (Ear, Seb, Sel, Sek); SaPI5 (Ear, Sek, Seq) |

HF 2 | HF 6 | ||||||||

| S. Typhimurium | Compatibility with prophage attachment (attB) sites for packaging by LTa | ||||||||||

| Locus | Contribution to virulence | St1 | St2 | St3 | St4 | St5 | St6 | St7 | St8 | St9 | St10 |

| SPI1 | Invasion of host cells | HF 9-10 | |||||||||

| SPI2 | Intracellular survival in macrophages | HF 9-10 | HF 4-5 | ||||||||

| SPI4 | SiiABCD and SiiE (adhesin) | HF 6-7 | HF 3 | ||||||||

| SPI5 | SopB (host cell cytoskeletal rearrangement), PipB (intramacrophage survival) | HF 6 | HF 3 | ||||||||

| SPI12 | Intracellular survival in macrophages; systemic survival in mice | HF 12 | |||||||||

| SPI16 | Contains three putative ORFs with a putative role in O-antigen glycosylation | HF 7 | |||||||||

| CS54 | Putative island postulated to have a role in adhesion | HF 4-5 | HF 7 | ||||||||

| tnpA_1 | IS200 transposon | HF 2-3 | |||||||||

| tnpA_2 | IS200 transposon | HF 3 | |||||||||

| tnpA_3 | IS200 transposon | HF 8 | |||||||||

| tnpA_4 | IS200 transposon | HF 6 | |||||||||

| tnpA_6 | IS200 transposon | HF8 | HF5 | ||||||||

aHF denotes the expected LT particle headful that the element would be expected to be packaged into by a standard-sized phage (~45 kb for staphylococcal phages, ~43 kb for Salmonella phages).

blpl lipoprotein-like, lukD leukotoxin D, lukE leukotoxin E, hysA hyaluronate lyase, hla α-haemolysin, tst toxic shock syndrome toxin, sel staphylococcal enterotoxin L, sek staphylococcal enterotoxin K, bap biofilm-associated protein, scin staphylococcal complement inhibitor, vWbp von Willebrand binding protein, ear E. coli ampicillin resistance, seq staphylococcal enterotoxin Q, sel staphylococcal enterotoxin L, seb staphylococcal enterotoxin B.

Source data are provided as a Source Data file.

The Staphylococcal genomic islands (GI) νSaα, vSaβ, and vSaγ are pathogenicity islands of DNA located within the S. aureus chromosome that encode a wide variety of genes involved in Staphylococcal virulence, including enterotoxins, serine proteases and leukotoxins22. Carriage of vSaα and vSaβ occurs widely among S. aureus strains23, with many strains also harbouring the third GI, vSaγ24. The absence of vSaγ from some strains strongly suggests that these elements have been obtained by S. aureus via HGT, with vSaγ being the most recent acquisition. Until recently, however, no mechanism had been ascribed that was able to satisfactorily explain how this widely spread TE could occur in nature. We believe that the discovery of LT provides an elegant mechanism explaining how such transfers can be facilitated at high frequency. Our reasoning for this is twofold: firstly, it is striking that each of the GIs is located in the S. aureus chromosome such that it is close to a prophage integration site (attB) in the direction of phage packaging, permitting compatibility with packaging and transfer via phage-mediated LT: vSaα is located downstream of the Sa6 prophage attB, compatible with packaging into HF3; vSaγ is located close (within two headfuls) to Sa7 attB, and is also compatible with packaging from Sa4 (~HF4-5) and Sa1 (~HF7) prophage attachment sites; while vSaβ is located close to attachment sites Sa8 (~HF1-2), Sa5 (~HF2-3), as well as Sa3 (~HF5-6)16. Secondly, two recent studies have demonstrated a role for staphylococcal prophages in the transduction of the GI24,25. Notably, the first of these studies showed transduction of vSaβ mediated by a prophage integrated at the Sa8 attachment site adjacent to the island. In this study, the authors describe phage-mediated transduction of the island via a complex double transduction event, where they speculate that overlapping sections of DNA from multiple transducing particles result in the transfer of vSaβ via HR25. It is interesting, however, that the authors describe transducing particles containing phage-vSaβ hybrid sections of DNA, a feature that is now known to be observed in HF1 of LT particles, suggesting the potential involvement of LT in the process of vSaβ mobilisation. In addition, the authors found a positive correlation between the presence of both vSaβ and a phage localised adjacent to the island among a panel of bovine S. aureus isolates, further suggesting a potential role for phage-mediated LT in the dissemination of this GI.

Similarly, it is interesting to speculate that LT may also have played a role in the evolution of the SaPIs in S. aureus. The organisation of the five SaPI chromosomal attachment sites described for S. aureus are orientated such that they are usually adjacent to a prophage integration site in the direction of phage packaging, permitting SaPI packaging and transfer via phage-mediated LT. Indeed, SaPIs integrated at SaPI Type I and II attachment sites could readily be mobilised via LT within HF2 or HF3, respectively, of a prophage integrated at Sa6 attB. Similarly, SaPI integration at SaPI Type III or IV attB sites would permit packaging of the island within the first (Type III) or second (Type IV) headful of a prophage integrated at Sa9 attB, or even from Sa12 attB (within ~HF6)16. Our analysis has shown that SaPI-specific transfer is highly efficient between cells at the expense of the helper phage, however, this level of transfer is entirely reliant on de-repression of the SaPI by its helper phage, allowing it to replicate and hijack the phage machinery26. In evolutionary terms, insertion of SaPI elements into the chromosome adjacent to phage attachment sites to permit exploitation of LT would provide a further ‘selfish’ mechanism for SaPI transfer by non-helper phages, promoting survival of the elements under non-inducing conditions and providing a mechanism, via recombination in the recipient cell, for the extensive mosaic-like variation observed in the cargo genes of different SaPIs27.

Though the picture is less striking in the case of S. Typhimurium, patterns of virulence-associated genes being located close enough to phage integration sites in the direction of packaging to facilitate their transfer via LT can nevertheless be observed (Table 4). In strain LT2, the 39.7 kb Salmonella Pathogenicity Island (SPI)-2, which encodes the genes necessary for intra-macrophage survival and proliferation28, is located 363.5 and 111.6 kb downstream of prophage attachment sites St3 and St4, respectively, permitting packaging into particles approximately 9–10 (St3) and 4–5 (St4) headfuls from the phage packaging initiation site. SPI-4, encoding the siiE non-fimbrial adhesion factor and the siiABCDF genes encoding the T1SS responsible for the transfer of SiiE into the host cell29, is located approximately 6–7 and 3 HFs downstream of the St9 and St10 attB sites, respectively. Similarly, SPI-5, which encodes effector proteins that contribute to host cell cytoskeletal rearrangement during invasion and intramacrophage survival30, is also orientated downstream of prophage attachment sites St2 and St3, permitting packaging into LT particle HF6 and HF3, respectively. Interestingly, the host cell invasion-associated locus, SPI-1, is positioned in the LT2 chromosome such that it should be compatible with LT originating from a prophage integrated at St8 attB, though admittedly, as it would be expected to be packaged into LT particle headful 9 or 10, its transfer efficiency may be reduced compared to that of other loci via the LT mechanism, suggesting that LT may be only one of the multiple mechanisms involved in mediating the HGT of these genetic elements.

A role for LT in maintaining the core genome

Although LT provides a mechanism for the potential transfer of massive quantities of bacterial chromosomal DNA at high frequencies, this transfer is likely only of benefit to closely related strains as (i) phages are typically considered to have narrow host-ranges, though the silent transfer of DNA by phages and PICIs has been reported between different species and genera31–34, suggesting that host-restriction for many phages is not as stringent as previously thought; and, vitally, (ii) donor and recipient cells must share sufficient DNA sequence homology to support homologous recombination (HR) of the transduced DNA into the chromosome. Such limits pose interesting questions as to the overall function of such widespread gene exchange between closely related bacteria and how it impacts evolution at the species level. While it is certainly possible, and indeed plausible, that LT facilitates the exchange of novel virulence genes between related strains, it may be that under most circumstances it serves a less conspicuous but equally important function: purifying the chromosome of undesirable mutations. The true extent of HR in bacterial lineages is difficult to infer as it is technically challenging to fully assess the frequency of such events between closely related organisms where the vast majority of recombination events would be almost impossible to detect, however evidence from MLST and biosynthetic gene sequencing analyses indicate that bacterial species do engage in frequent HR events35, though this may be to a greater or lesser extent depending on the species36. Despite the evidence that HR occurs regularly in nature, fundamental questions remain unsolved regarding both the mechanism of transfer involved in providing exogenous DNA, as well as the volume of this external DNA that arrives at the recipient cells, particularly in species that have not been demonstrated to be naturally transformable. Given the propensity for poly-lysogeny in many bacteria, coupled with the frequency and magnitude of DNA transfer by LT, we propose here that LT facilitates the continual exchange of core genes between strains. This constant arrival of exogenous DNA can be used to purify the chromosome of undesirable mutations, reducing deleterious genetic drift.

Indeed, there is already evidence in the literature to indicate that incorporation of exogenous DNA via HR can serve as a chromosomal sanitising strategy in some naturally competent species, with Streptococci utilising this mechanism to cure their genomes of parasitic MGEs, including prophages37. Such a scenario sets up an interesting dichotomy for the fate of prophages in cells receiving exogenous chromosomal DNA via LT particles, as there is a possibility that resident prophages could be sanitised from the recipient host chromosome if incoming DNA originated from a donor cell that lacked a prophage at the corresponding chromosomal attachment site. It is likely in this scenario that the role of the prophage in contributing to host niche adaptation has an important part to play in its retention; prophages in Streptococcus pneumoniae typically do not carry accessory genes of apparent benefit to the bacterial host cell37 rendering prophages in this species overt parasites. In contrast, many staphylococcal prophages contribute genes with important virulence traits to their S. aureus hosts38, tipping the selective balance in favour of prophage maintenance by the host cell. Furthermore, it is important to note that despite the presence of competence genes in more than 80 bacterial species39, relatively few bacterial species have been demonstrated to actively engage in natural transformation, so it may be that natural transformation and LT serve parallel functions in different bacterial species depending on their tendency towards or against lysogeny. To date, LT has been described only for phages of S. aureus (80α and φ1116), S. Typhimurium (P22) and Enterococcus faecalis (φp1)17, and thus it is likely that as more bacterial-phage pairs are studied, we will glean more information on the implications of LT-mediated chromosomal curing for prophage distribution in other species.

In addition to providing substrate DNA for curing disadvantageous mutations of the chromosome, it is also possible that LT, with subsequent HR of the transduced DNA, has an additional important role to play in mitigating the effect of clonal interference in polymicrobial communities. HR of exogenous DNA has previously been shown to be important for escaping clonal interference in drug-resistant bacterial populations, whereby HR enables multiple independent advantageous mutations to be transferred from different competing donor organisms and combined into a single recipient, bestowing upon it a competitive advantage over the donor populations carrying the individual mutations40. Given the capacity for large spans of DNA to be transferred at high frequency via LT, it is likely that LT also contributes to genome evolution via this mechanism.

Gene transfer agents: pretenders to the LT throne?

In some species, including Rhodobacter capsulatus, Bartonella spp. and Bacillus spp., horizontal transfer of chromosomal DNA may also be facilitated by small phage-like particles knowns as gene transfer agents (GTAs)41. The exact role of GTAs remains unclear, though these elements do share some similar characteristics with transducing particles, principally in that they package and transfer chromosomal DNA from their donor cell in a tailed, membrane-bound vesicle reminiscent of phage virions, with the tail on the GTA particle likely demanding receptor specificity for the recipient host cell, and they do not readily transfer genes required for their own propagation41. However, GTAs and LT particles also exhibit stark dissimilarities, with implications for their respective putative roles in contributing to bacterial genome evolution via HGT. While GTAs package chromosomal DNA from their donor cell, they do so in an apparently random manner41, which also occurs in GT but is in contrast to the specificity in packaging observed in LT, directed by the prophage integration site. In addition, in situ replication of activated prophages during the early LT process leads to amplification of adjacent chromosomal DNA, resulting in the generation of multiple copies of the chromosomal genes downstream of the prophage16. Such replication ensures that there is an excess of substrate DNA for packaging via the LT mechanism, generating a large pool of LT particles containing similar regions of DNA sequence that may then be transferred to new recipient cells at high frequency, optimising the chances of successful HR occurring. By contrast, to our knowledge, there is currently no available data to suggest that such redundancy in the packaged DNA occurs for GTAs. In addition, GTAs also appear to be limited in terms of their packaging capacity, transferring only ~5–15 kb of DNA per virion particle41, which is significantly lower than the capacity available for transfer via LT particles, which exhibit capacities comparable to that of their facilitating prophage. Taken together, owing to the differences in the magnitude and specificity of DNA transferred by GTAs and LT, it is arguably unlikely that GTAs represent a mechanism for the HGT of DNA with equivalent power to that of LT.

Concluding remarks

In summary, we propose here that the discovery of LT has redefined how we perceive genetic mobility in bacteria. This powerful mechanism of transduction deconstructs the conventional sense of an MGE by uncoupling mobility from the genetic element and imparting it to the bacterial genome, where mobility is designated by coordinates in the chromosome (relative to prophages) and not defined by the carriage of the MGEs themselves. In effect, LT creates highly efficient platforms for chromosomal packaging and transfer that facilitates the exchange of ‘immobile’ core genes at high frequencies that are significantly higher than those of most elements classically considered as mobile. Furthermore, such dramatic exchange of chromosomal DNA not only provides significant opportunities for the rapid acquisition of virulence factors but also offers a plausible mechanism for the delivery of core genetic material between related strains at sufficiently high rates to permit the extensive HR necessary to maintain the species identity. Surprisingly, our analysis indicated that many MGEs are not as mobile as we previously assumed and that despite the existence of strategies to enhance their transmissibility, their transfer is restricted. We recognise that what we propose here is heretical to the accepted paradigm of bacterial genetic mobility, and we would be remiss to ignore the argument that because chromosomal mobility is completely dependent on other members of the mobilome, namely phages, it cannot truly be considered mobile. For that, we would contend that this standpoint is undermined by the broad inclusion of non-conjugative plasmids and transposons as members of the mobilome. Ultimately, the discovery of LT has blurred the lines of what we can consider being mobile, and therefore there is a need for a scientific discussion about whether the bacterial chromosome itself could actually qualify as a mobile element.

Methods

Bacterial strains and plasmids

The bacterial strains and plasmids used in this study are detailed in Table 5. S. aureus strains were grown in tryptic soy broth (TSB) or on tryptic soy agar (TSA) plates supplemented with 1.7 mM sodium citrate. Salmonella enterica serovar Typhimurium was grown in Luria Bertani (LB) broth or on LB agar (LBA) plates. Where appropriate, the following antibiotic concentrations were used for phage, plasmid, or chromosomal marker selection: erythromycin, 10 µg/ml; ampicillin, 100 µg/ml; chloramphenicol, 20 µg/ml; cadmium chloride, 100 µM.

Table 5.

Bacterial strains and plasmids.

| Strain | Description | Reference |

|---|---|---|

| RN4220 | Staphylococcus aureus restriction-defective derivative of RN450 | Lab strain |

| JP6399 | RN450 lysogenic for 80α carrying an erythromycin resistance cassette (80α::ermC) | 16,57 |

| JP6400 | RN451 lysogenic for φ11 carrying an erythromycin resistance cassette (φ11::ermC) | 16,57 |

| JP14277 | RN4220 SAOUHSC_01121::cadCA; cadmium resistance cassette inserted 35 kb downstream of Sa7 attB | 16 |

| JP19145 | RN4220 SAOUHSC_01121::cadCA; cadmium resistance cassette inserted 5 kb downstream Sa5 attB | 16 |

| JP20714 | JP14277 pJP2511 | This work |

| JP20716 | JP19145 pJP2511 | This work |

| JP20844 | JP20714 lysogenic for φ11::ermC | This work |

| JP20846 | JP20716 lysogenic for 80α::ermC | This work |

| JP18938 | Salmonella enterica serovar Typhimurium LT2 ΔFels-1 ΔGifsy-2 ΔGifsy-1 ΔFels-2 | 17 |

| JP18983 | JP18938 lysogenic for P22 | 17 |

| JP22210 | JP18983 lysogenic for P22 sie::cat | This work |

| Plasmid | Description | Reference |

| pKD46 | Thermosensitive plasmid with Red lambda system, ampR | 58 |

| pJP2511 | Gram-positive plasmid containing a chloramphenicol resistance cassette, catR | 59 |

Construction of marked phage P22

Insertion of a chloramphenicol resistance marker into Salmonella phage P22 was performed as previously described7. Briefly, polymerase chain reaction (PCR) amplification of the chloramphenicol resistance marker was performed using oligonucleotides P22-sie-cat-1m (5′-GGCAAAGTACCACACTGTTATCAGCAAACTTAGTGGTATATGAATTACTGGGAATAGGAACTTCATTTAAATGGC) and P22-sie-cat-2c (5′-GCGCACTCATGGGCAATAGTAGATAGTTTGCCATTGAACACGCCTATCACGGCGCGCCTACCTGTGACGG). PCR products were transformed into recipient strain JP18983 harbouring plasmid pKD46, which expresses the λ Red recombinase, facilitating the insertion of the marker into the phage genome. The placement of the marker was subsequently verified by PCR and Sanger sequencing (Eurofins Genomics).

Phage induction

S. aureus strains lysogenic for phages φ11::ermC and 80α::ermC, were grown in TSB to early exponential phase (OD540 ~0.15) at 37 °C and 120 rpm. S. Typhimurium lysogenic for phage P22sie::cat, was grown in LB to early exponential phase (OD600 ~0.20) at 37 °C and 120 rpm. All prophages were induced by the addition of mitomycin C (2 µg/ml), then were incubated for 4–5 h at 30 °C followed by overnight incubation at room temperature to permit full phage lysis, before filtering with a 0.2 µm syringe filter (Sartorius).

Determination of phage lysogenisation rates

To determine the rate of lysogenisation for S. aureus phages 80α and φ11, 100 µl of phage lysate or a dilution of lysate prepared in phage buffer (100 mM NaCl, 50 mM Tris, 10 mM MgSO4, 4 mM CaCl2) was used to infect 1 ml of recipient S. aureus RN4220 cells at OD540 1.4, supplemented with 4.4 mM CaCl2. After static incubation for 20 min at 37 °C, 3 ml TTA (TSA top agar; 3 g/100 ml TSB, Oxoid, plus 0.75 g/100 ml agar, Formedium) was added to each reaction and the entire contents were poured onto a TSA plate supplemented with 1.7 mM sodium citrate +10 µg/ml erythromycin.

The same method was used for determination of the transfer rate of plasmid pJP2511 and CdR chromosomal markers into RN4220 by phage 80α and φ11 transduction, with selection on TSA supplemented with 1.7 mM sodium citrate + 20 µg/ml chloramphenicol (for the plasmid) or 100 µM CdCl2 (for chromosomal markers).

To determine the rate of lysogenisation for S. Typhimurium phage P22, 100 µl of phage lysate or a dilution of lysate prepared in phage buffer was used to infect 1 ml of recipient Salmonella (JP18938) cells at OD600 1.4, supplemented with 4.4 mM CaCl2. After static incubation for 20 min at 37 °C, 3 ml LTA (LB top agar; 2 g/100 ml LB, Oxoid, plus 0.75 g/100 ml agar, Formedium) was added to each reaction and the entire contents were poured onto an LBA plate supplemented with 20 µg/ml chloramphenicol.

In all cases, plates were incubated at 37 °C for 24 h and the number of colonies formed (representing phage particles present in the lysate) was counted and expressed as the colony-forming units (CFU)/ml. Results are reported as the number of lysogens or transductants obtained per donor cell-induced (for S. aureus this is equivalent to 6.5 × 107 donor CFU/ml at OD540 0.15; for Salmonella this is equivalent to 1 × 108 donor CFU/ml at OD600 0.20) and are the mean values of three (P22) or four (80α and φ11) independent experiments.

Analysis of transfer rates

Transfer frequency values for the different elements analysed were obtained from the published literature, with their sources indicated in Tables 1 and 3. In order to enable comparisons between conjugation and the other modes of horizontal gene transfer, the transfer frequency of published phage- and PICI-mediated DNA transfer was re-analysed as TE per bacterial donor cell at the time of prophage induction: TE per donor cell = Lysogenisation or Transductant Units (TrU) per ml/donor CFU per ml at the time of phage induction. For the S. aureus data analysed, lysogens were reportedly induced at OD540 ~0.15, which is equivalent to 6.5 × 107 CFU per ml in the donor population, while for Salmonella, lysogens were induced at OD600 0.2, which is equivalent to 1 × 108 CFU per ml in the donor population.

Estimation of the cargo capacity

SnapGene Viewer version 5.3 (open source software: https://www.snapgene.com/snapgene-viewer/) was used to import and visualise DNA sequences from Genbank for different genetic elements where accession numbers were available, to enable determination of the total number of ORFs and their predicted functions for calculation of estimated ‘cargo capacity’ rates. The accession numbers are provided in the manuscript in Tables 1 and 3. This programme was also used to import and visualise complete chromosomal DNA sequences for S. aureus NCTC8325-4 (accession: NC_007795.1) and S. Typhimurium LT2 (accession: AE006468.2) to enable: (i) mapping of the coordinates of successive lateral transducing particle headfuls from each attB site; (ii) estimation of the number of ORFs contained within each lateral transducing particle headful for calculation of estimated ‘cargo capacity’; (iii) location mapping of loci/genes of interest relative to attB sites on the S. aureus and S. Typhimurium chromosomes.

Reporting summary

Further information on research design is available in the Nature Research Reporting Summary linked to this article.

Supplementary information

Acknowledgements

We thank Jean-Marc Ghigo, Álvaro San-Millán, David W. Holden and Julian Parkhill for comments on this paper. This work was supported by grants MR/M003876/1, MR/V000772/1 and MR/S00940X/1 from the Medical Research Council (UK), BB/N002873/1, BB/V002376/1 and BB/S003835/1 from the Biotechnology and Biological Sciences Research Council (BBSRC, UK), ERC-ADG-2014 Proposal n° 670932 Dut-signal (from EU), to J.R.P; and Wellcome Trust 201531/Z/16/Z to J.R.P.

Source data

Author contributions

S.H. and J.R.P. conceived the study. S.H. performed the data analysis. A.F.S., N.Q.P., R.I.C. and A.H. performed the experiments. S.H., J.C. and J.R.P. wrote the paper. J.R.P. supervised the work.

Data availability

Source data is available in the accompanying excel file. For all data derived from published literature, the source is indicated as a citation in the manuscript. Accession numbers relating to each element analysed are included in the manuscript (Tables 1 and 3), where they were available. Source data are provided with this paper.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Peer review information Nature Communications thanks Breck Duerkop and the other, anonymous, reviewers for their contribution to the peer review of this work. Peer reviewer reports are available.

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1038/s41467-021-26004-5.

References

- 1.Siefert, J. L. Defining the Mobilome. in (eds Gogarten, M. B., Gogarten, J. P. & Olendzenski, L. C.) vol. 532, 13–27 (Humana Press, 2009).

- 2.Smillie C, Garcillán-Barcia MP, Francia MV, Rocha EPC, Cruz FDL. Mobility of plasmids. Microbiol. Mol. Biol. Rev. 2010;74:434–452. doi: 10.1128/MMBR.00020-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Halary S, Leigh JW, Cheaib B, Lopez P, Bapteste E. Network analyses structure genetic diversity in independent genetic worlds. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2010;107:127–132. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0908978107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Fillol-Salom A, et al. Bacteriophages benefit from generalized transduction. PLoS Pathog. 2019;15:e1007888. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1007888. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Chen J, Ram G, Penadés JR, Brown S, Novick RP. Pathogenicity island-directed transfer of unlinked chromosomal virulence genes. Mol. Cell. 2015;57:138–149. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2014.11.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Johnson CM, Grossman AD. Integrative and conjugative elements (ICEs): what they do and how they work. Annu. Rev. Genet. 2015;49:577–601. doi: 10.1146/annurev-genet-112414-055018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Sansevere EA, Robinson DA. Staphylococci on ICE: overlooked agents of horizontal gene transfer. Mob. Genet. Elem. 2017;7:1–10. doi: 10.1080/2159256X.2017.1368433. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Penadés JR, Christie GE. The phage-inducible chromosomal islands: a family of highly evolved molecular parasites. Annu. Rev. Virol. 2015;2:181–201. doi: 10.1146/annurev-virology-031413-085446. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Fillol-Salom A, et al. Phage-inducible chromosomal islands are ubiquitous within the bacterial universe. ISME J. 2018;12:2114–2128. doi: 10.1038/s41396-018-0156-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Martínez-Rubio R, et al. Phage-inducible islands in the Gram-positive cocci. ISME J. 2017;11:1029–1042. doi: 10.1038/ismej.2016.163. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Wagner PL, Waldor MK. Bacteriophage control of bacterial virulence. Infect. Immun. 2002;70:3985–3993. doi: 10.1128/IAI.70.8.3985-3993.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Novick RP, Ram G. Staphylococcal pathogenicity islands-movers and shakers in the genomic firmament. Curr. Opin. Microbiol. 2017 doi: 10.1016/j.mib.2017.08.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Chiang YN, Penadés JR, Chen J. Genetic transduction by phages and chromosomal islands: the new and noncanonical. PLoS Pathog. 2019;15:e1007878. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1007878. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Morse ML, Lederberg EM, LEDERBERG J. Transduction in Escherichia coli K-12. Genetics. 1956;41:142–156. doi: 10.1093/genetics/41.1.142. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.ZINDER ND, LEDERBERG J. Genetic exchange in Salmonella. J. Bacteriol. 1952;64:679–699. doi: 10.1128/jb.64.5.679-699.1952. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Chen J, et al. Genome hypermobility by lateral transduction. Science. 2018;362:207–212. doi: 10.1126/science.aat5867. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Fillol-Salom, A. et al. Lateral transduction is inherent to the life cycle of the archetypical Salmonella phage P22. Nat. Commun.10.1038/s41467-021-26520-4 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 18.Eberhard WG. Why do bacterial plasmids carry some genes and not others? Plasmid. 1989;21:167–174. doi: 10.1016/0147-619x(89)90040-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.DiCenzo GC, Finan TM. The divided bacterial genome: structure, function, and evolution. Microbiol. Mol. Biol. Rev. 2017;81:e00019–17. doi: 10.1128/MMBR.00019-17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Niehus R, Mitri S, Fletcher AG, Foster KR. Migration and horizontal gene transfer divide microbial genomes into multiple niches. Nat. Commun. 2015;6:8924. doi: 10.1038/ncomms9924. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Bergstrom CT, Lipsitch M, Levin BR. Natural selection, infectious transfer and the existence conditions for bacterial plasmids. Genetics. 2000;155:1505–1519. doi: 10.1093/genetics/155.4.1505. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Malachowa N, DeLeo FR. Mobile genetic elements of Staphylococcus aureus. Mol. Life Sci. 2010;67:3057–3071. doi: 10.1007/s00018-010-0389-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Baba T, Bae T, Schneewind O, Takeuchi F, Hiramatsu K. Genome sequence of Staphylococcus aureus strain Newman and comparative analysis of staphylococcal genomes: polymorphism and evolution of two major pathogenicity islands. J. Bacteriol. 2008;190:300–310. doi: 10.1128/JB.01000-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Moon BY, et al. Mobilization of genomic islands of Staphylococcus aureus by temperate bacteriophage. PloS ONE. 2016;11:e0151409. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0151409. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Moon BY, et al. Phage-mediated horizontal transfer of a Staphylococcus aureus virulence-associated genomic island. Sci. Rep. 2015;5:9784. doi: 10.1038/srep09784. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Tormo-Más MÁ, et al. Moonlighting bacteriophage proteins derepress staphylococcal pathogenicity islands. Nature. 2010;465:779–782. doi: 10.1038/nature09065. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Novick RP, Christie GE, Penadés JR. The phage-related chromosomal islands of Gram-positive bacteria. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 2010;8:541–551. doi: 10.1038/nrmicro2393. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Hensel M, et al. Genes encoding putative effector proteins of the type III secretion system of Salmonella pathogenicity island 2 are required for bacterial virulence and proliferation in macrophages. Mol. Microbiol. 1998;30:163–174. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.1998.01047.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kiss T, Morgan E, Nagy G. Contribution of SPI-4 genes to the virulence of Salmonella enterica. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 2007;275:153–159. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-6968.2007.00871.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Knodler LA, et al. Salmonella effectors within a single pathogenicity island are differentially expressed and translocated by separate type III secretion systems. Mol. Microbiol. 2002;43:1089–1103. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.2002.02820.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Chen J, et al. Intra- and inter-generic transfer of pathogenicity island-encoded virulence genes by cos phages. ISME J. 2015;9:1260–1263. doi: 10.1038/ismej.2014.187. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Beumer A, Robinson JB. A broad-host-range, generalized transducing phage (SN-T) acquires 16S rRNA genes from different genera of bacteria. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2005;71:8301–8304. doi: 10.1128/AEM.71.12.8301-8304.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Chen J, Novick RP. Phage-mediated intergeneric transfer of toxin genes. Science. 2009;323:139–141. doi: 10.1126/science.1164783. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Maiques E, et al. Role of staphylococcal phage and SaPI integrase in intra- and interspecies SaPI transfer. J. Bacteriol. 2007;189:5608–5616. doi: 10.1128/JB.00619-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Dykhuizen DE, Green L. Recombination in Escherichia coli and the definition of biological species. J. Bacteriol. 1991;173:7257–7268. doi: 10.1128/jb.173.22.7257-7268.1991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Feil EJ, et al. Recombination within natural populations of pathogenic bacteria: short-term empirical estimates and long-term phylogenetic consequences. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA. 2001;98:182–187. doi: 10.1073/pnas.98.1.182. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Croucher NJ, et al. Horizontal DNA transfer mechanisms of bacteria as weapons of intragenomic conflict. Plos Biol. 2016;14:e1002394. doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.1002394. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Xia G, Wolz C. Phages of Staphylococcus aureus and their impact on host evolution. Infect. Genet. Evol. 2014;21:593–601. doi: 10.1016/j.meegid.2013.04.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Johnston C, Martin B, Fichant G, Polard P, Claverys JP. Bacterial transformation: distribution, shared mechanisms and divergent control. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 2014;12:181–196. doi: 10.1038/nrmicro3199. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Perron GG, Lee AEG, Wang Y, Huang WE, Barraclough TG. Bacterial recombination promotes the evolution of multi-drug-resistance in functionally diverse populations. Proc. R. Soc. B Biol. Sci. 2012;279:1477–1484. doi: 10.1098/rspb.2011.1933. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Lang AS, Zhaxybayeva O, Beatty JT. Gene transfer agents: phage-like elements of genetic exchange. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 2012;10:472–482. doi: 10.1038/nrmicro2802. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Savage VJ, Chopra I, O’Neill AJ. Staphylococcus aureus biofilms promote horizontal transfer of antibiotic resistance. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2013;57:1968–1970. doi: 10.1128/AAC.02008-12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Thomas WD, Archer GL. Identification and cloning of the conjugative transfer region of Staphylococcus aureus plasmid pGO1. J. Bacteriol. 1989;171:684–691. doi: 10.1128/jb.171.2.684-691.1989. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Zhu W, Clark N, Patel JB. pSK41-like plasmid is necessary for Inc18-like vanA plasmid transfer from Enterococcus faecalis to Staphylococcus aureus in vitro. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2013;57:212–219. doi: 10.1128/AAC.01587-12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.O’Brien FG, et al. Origin-of-transfer sequences facilitate mobilisation of non-conjugative antimicrobial-resistance plasmids in Staphylococcus aureus. Nucleic Acids Res. 2015;43:7971–7983. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkv755. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.O’Brien FG, et al. Staphylococcus aureus plasmids without mobilization genes are mobilized by a novel conjugative plasmid from community isolates. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 2015;70:649–652. doi: 10.1093/jac/dku454. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Quiles-Puchalt N, et al. Staphylococcal pathogenicity island DNA packaging system involving cos-site packaging and phage-encoded HNH endonucleases. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA. 2014;111:6016–6021. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1320538111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Sansevere EA, et al. Transposase-mediated excision, conjugative transfer, and diversity of ICE6013 elements in Staphylococcus aureus. J. Bacteriol. 2017;199:e00629–16. doi: 10.1128/JB.00629-16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Jones JM, Yost SC, Pattee PA. Transfer of the conjugal tetracycline resistance transposon Tn916 from Streptococcus faecalis to Staphylococcus aureus and identification of some insertion sites in the staphylococcal chromosome. J. Bacteriol. 1987;169:2121–2131. doi: 10.1128/jb.169.5.2121-2131.1987. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Ahmer BM, Tran M, Heffron F. The virulence plasmid of Salmonella Typhimurium is self-transmissible. J. Bacteriol. 1999;181:1364–1368. doi: 10.1128/jb.181.4.1364-1368.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Anjum MF, et al. Colistin resistance in Salmonella and Escherichia coli isolates from a pig farm in Great Britain. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 2016;71:2306–2313. doi: 10.1093/jac/dkw149. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Chu C, et al. Evolution of genes on the Salmonella virulence plasmid phylogeny revealed from sequencing of the virulence plasmids of S. enterica serotype Dublin and comparative analysis. Genomics. 2008;92:339–343. doi: 10.1016/j.ygeno.2008.07.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Aviv G, et al. A unique megaplasmid contributes to stress tolerance and pathogenicity of an emergent Salmonella enterica serovar Infantis strain. Environ. Microbiol. 2014;16:977–994. doi: 10.1111/1462-2920.12351. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Wang W, et al. Complete complete genomic analysis of a Salmonella enterica serovar Typhimurium isolate cultured from ready-to-eat pork in china carrying one large plasmid containing mcr-1. Front. Microbiol. 2018;9:616. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2018.00616. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Seth-Smith HMB, et al. Structure, diversity, and mobility of the Salmonella pathogenicity island 7 family of integrative and conjugative elements within Enterobacteriaceae. J. Bacteriol. 2012;194:1494–1504. doi: 10.1128/JB.06403-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Arai, N. et al. Salmonella genomic island 3 is an integrative and conjugative element and contributes to copper and arsenic tolerance of Salmonella enterica. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 63, 10.1128/AAC.00429-19 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 57.Quiles-Puchalt N, Martínez-Rubio R, Ram G, Lasa I, Penadés JR. Unravelling bacteriophage ϕ11 requirements for packaging and transfer of mobile genetic elements in Staphylococcus aureus. Mol. Microbiol. 2014;91:423–437. doi: 10.1111/mmi.12445. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Datsenko KA, Wanner BL. One-step inactivation of chromosomal genes in Escherichia coli K-12 using PCR products. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA. 2000;97:6640–6645. doi: 10.1073/pnas.120163297. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Haag AF, et al. A regulatory cascade controls Staphylococcus aureus pathogenicity island activation. Nat. Microbiol. 2021;6:1300–1308. doi: 10.1038/s41564-021-00956-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

Source data is available in the accompanying excel file. For all data derived from published literature, the source is indicated as a citation in the manuscript. Accession numbers relating to each element analysed are included in the manuscript (Tables 1 and 3), where they were available. Source data are provided with this paper.