Abstract

COVID-19 has had a devastating impact on outcomes in lung cancer leading to later stage presentation, less curative treatment and higher mortality. This has amplified the existing problem of late-stage presentation in lung cancer and is a call to arms for a multifaceted strategy to address this, including public awareness campaigns to promote healthcare review in patients with persistent chest symptoms. We report the learning from patient and public insight work from across the North of England exploring the barriers to seeking healthcare review with persistent chest symptoms. Members of the public described how a lack of importance is placed on the common symptoms of lung cancer and a feeling of being unworthy of review by healthcare professionals. They would feel motivated to seek review by dispelling the nihilism of lung cancer and would be able to take action more easily by removing the logistical hassle in the process. We propose a four-pillar framework (validation–endorsement–motivation–action) for developing the content of any public awareness campaigns promoting early diagnosis of lung cancer based on the findings of this comprehensive insight work. All providers and commissioners must work together to overcome the perceived and real barriers to patients with persistent chest symptoms.

Keywords: COVID-19, lung cancer

Lung cancer is the most common cause of cancer death in the UK, responsible for nearly 30 000 deaths every year.1 Less than 40% of patients diagnosed with lung cancer survive for more than 1 year after diagnosis.2 A major cause for these poor outcomes is late presentation with advanced stage disease when curative intent treatment cannot be provided. Greater Manchester, in the North West of England, has a population of over 3 million people with high rates of smoking and socioeconomic deprivation. The age-standardised mortality rate for lung cancer in Greater Manchester is 75.3 per 100 000 population, compared with the England average of 55.9.3

The COVID-19 pandemic has had a devastating impact on the lung cancer community.4 5 In Greater Manchester, suspected lung cancer referrals dropped from approximately 150 per week to less 50 per week in the initial stages of the pandemic. Since then, referrals have only recovered to approximately 75 referrals per week despite all other tumour-type referrals returning to baseline levels or higher (Greater Manchester Cancer Alliance data, not published externally). The number of primary care chest X-rays (CXRs) has also suffered significantly with a reduction from approximately 10 000–15 000 CXRs per month pre-pandemic to approximately 4000–6000 CXRs per month, a number which has still not recovered (Greater Manchester Cancer Alliance data, not published externally). This dramatic reduction in CXRs is likely to be a contributing factor to the increase in late-stage presentation of lung cancer in 2020 compared with 2019 across the UK and the associated reduction in curative treatments and increased mortality.6 This hypothesis is supported by the results of a public awareness campaign in Leeds that increased stage I/II lung cancer diagnoses by 8.8% and reduced stage 4 diagnoses by 9.3% through increasing CXR uptake in symptomatic patients at risk of lung cancer by over 80%.7

There is, therefore, an urgent need to address late stage presentation in lung cancer, which has only been magnified by the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic. Public awareness campaigns encouraging those with symptoms that could be caused by lung cancer to seek an appointment in primary care and increasing CXR uptake should form one part of a multifaceted approach to this strategy. In this article, we report the learning from insight work with members of the public regarding barriers, both before and during the COVID-19 pandemic, to seeking healthcare review with symptoms that could be caused by lung cancer and what the optimal strategy might be for the most impactful public awareness campaigns.

This insight work consisted of four focus groups across Northern England that took place in September 2020. The four groups consisted of: groups 1 and 2: men aged >50 years from the C2DE demographic classification (skilled working class, working class, non-working class), group 3: women aged >50 years from C2DE and group 4: men aged >50 years from the ABC1 demographic classification (upper, middle and lower middle class). This configuration is representative of the higher prevalence of lung cancer in lower socioeconomic groups. Participants were mixed working status (part-time, full-time, retired) and had all previously delayed going to see a general practitioner (GP).

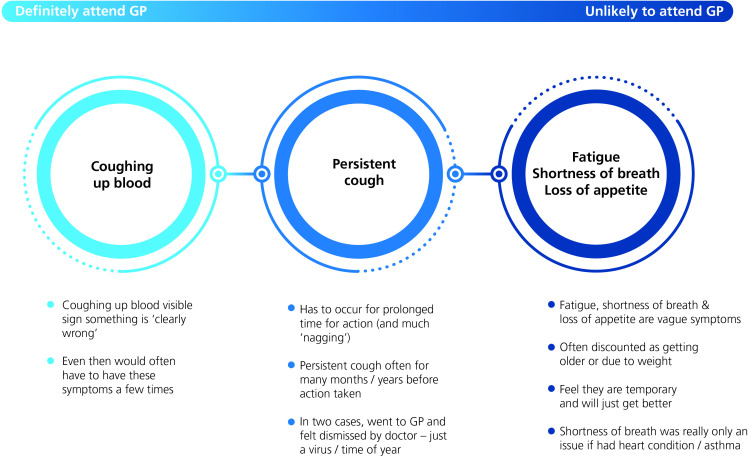

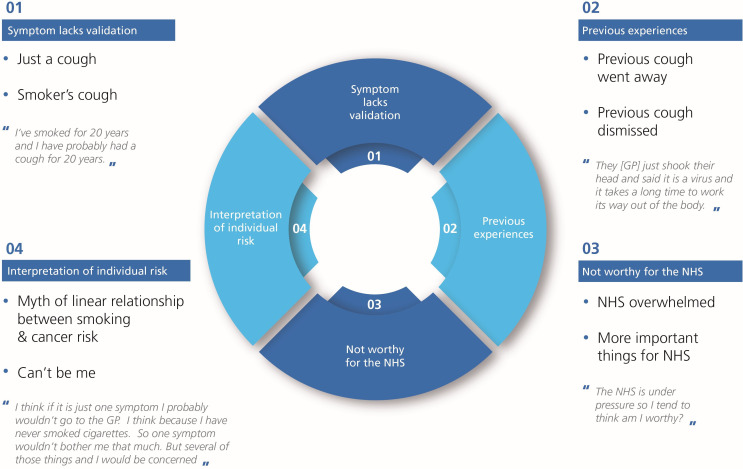

A consistent theme raised by the participants as a barrier to seeking a medical review was the need to feel validated to do so. The participants stated they would need to feel justified in their reasons for review and would seek a form of permission to do so. While the symptom of haemoptysis was generally felt to provide immediate validation and is ‘worthy’ of healthcare review, a persistent cough, breathlessness, fatigue and loss of appetite were felt to lack the same validation (figure 1). This lack of validation and lack of importance placed on the common symptoms of lung cancer is a complex and multilayered behaviour (figure 2). Participants reported previous experiences where they felt these symptoms had been discounted and they feared they would be dismissed if seeking medical review with this again. They thought there were other explanations for a cough, particularly those that could be used as a negative reflection on them, such as smoking tobacco, and that they might interpret their own individual risk of a serious cause for their symptoms as low. These reasons were then used as cumulative reasoning to judge these specific symptoms to be of less importance than the priorities of a busy National Health Service (NHS), a feeling that that was magnified by the COVID-19 pandemic and the repeated terminology of the ‘risk of overwhelming the NHS’. All these factors combined to make the participants feel that persistent non-specific symptoms such as cough, breathlessness, fatigue and loss of appetite were not worthy of medical review and may result in a lack of action.

Figure 1.

Levels of importance placed on the common symptoms of lung cancer by participants in our focus groups. GP, general practitioner.

Figure 2.

Multilayered reasoning for the lack of validation placed on common symptoms of lung cancer. GP, general practitioner; NHS, National Health Service.

Additional reported barriers to seeking medical review were a fear of a diagnosis of lung cancer and interpreted consequences on quality of life as well as the logistical inconvenience of arranging a medical review. One male C2DE participant stated, “I wouldn’t want to go through cancer treatment and lose three fourths of a lung or one lung. When it says survival, I would like to be as fit as I am now after treatment. If I am not, then I might as well go in a hole as get fixed. I wouldn’t want to be half the person I am now.” These comments were reflected by a number of participants suggesting nihilism about the ability to treat lung cancer without causing significant negative impacts on quality of life and with limited success. These comments would be consistent with the findings of the National Lung Cancer Audit spotlight audit on the reasons for early-stage patients with good performance status not receiving radical treatment, which showed that 30% of those who were not treated resulted from patient choice.8 Participants also reported a very low threshold for giving up on seeking a medical review if logistical barriers were faced. These included difficulty in contacting a GP practice on the phone and if seeking medical review was, in their view, deemed as a time-consuming process when measured against other day-to-day priorities.

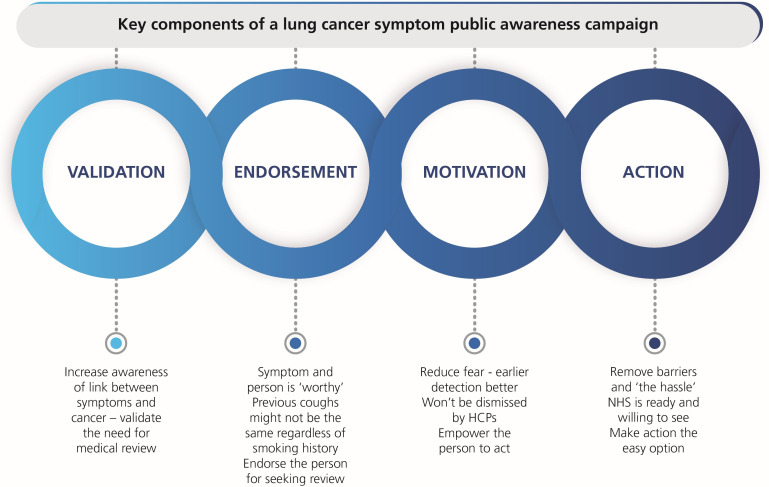

When discussing the content and approach of public awareness campaigns, four key themes were established to ensure the maximal impact of the campaign: validation, endorsement, motivation and action (figure 3). The public must feel validated to seek medical review with symptoms such as cough, breathlessness, fatigue and loss of appetite. Linking these symptoms to lung cancer and increasing the importance placed on them by the medical community will help to validate the reason for seeking medical review. The public must feel an endorsement from the NHS to seek review in the presence of these symptoms through educational messaging. This messaging should include not dismissing the cause of the symptom based on previous experiences, that not all coughs are colds or COVID-19 and that anybody can develop lung cancer regardless of smoking history. The motivation to seek review is centred on dispelling the nihilism in lung cancer and focusing on early diagnosis that improves the chances of curative treatment. Facts describing the difference in outcomes between early-stage lung cancer and late-stage lung cancer may help illustrate this but ensuring the messaging remains upbeat with references to ‘surviving lung cancer’ with good quality of life is critical. Finally, empowering the public to request medical help by removing perceived or real logistical barriers to seeking review would increase the probability of taking action. This might include a very specific, clear and focused instruction to request a CXR if symptoms persist beyond 3 weeks or a direct access CXR scheme whereby the public can directly access this test under certain criteria. Participants strongly supported these messages being delivered by healthcare professionals and patients that have been through successful treatment for lung cancer without significant impact on their quality of life.

Figure 3.

Validation–endorsement–motivation–action framework for public awareness campaigns promoting early diagnosis of lung cancer. HCPs, healthcare professionals; NHS, National Health Service.

The learning and framework produced from this insight work has been used to develop a public awareness campaign called ‘Do It For Yourself’ that has been run across Greater Manchester and other areas of Northern England. This campaign uses a ‘DIY’ theme to link the symptom of cough to lung cancer and endorse the public to seek medical review in the same way the public often report how they would not let a broken washing machine or outstanding DIY job go without action, neither should the symptom of cough go without action. Information on early diagnosis and surviving lung cancer is there to motivate members of the public into a specific and focused action to see their GP. This format and concept tested well with the four focus groups and resulted in over 33 million viewings of the campaign creatives (figure 4). The campaign ran in November and December 2020 and lung cancer referrals reached 67% of pre-pandemic levels in the last week of November, the highest level since the pandemic began.

Figure 4.

Campaign creatives for the ‘Do It For Yourself’ campaign in Northern England (images provided with permission from Merck, Sharpe & Dohme (UK) Limited).

In conclusion, the COVID-19 pandemic has amplified the devastating impact of lung cancer through late-stage presentation. The NHS and cancer alliances must integrate public awareness campaigns that promote early diagnosis through medical review and CXR uptake into their lung cancer and COVID-19 recovery strategies. This work provides a four-pillar framework (validation, endorsement, motivation and action) for public awareness campaigns to maximise their impact based on a comprehensive public insight work representative of the lung cancer community. All healthcare professionals can play their role in the constant validation of symptoms that may be caused by lung cancer, through endorsing patients when they attend for these symptoms even if lung cancer is ultimately excluded, as it will be for the majority, and ensuring the public are made to feel worthy of the attention of the healthcare system. Providers and commissioners should work to reduce perceived and real barriers to patients seeking medical review for such symptoms.

Acknowledgments

The insight work for the ‘Do It For Yourself’ campaign was conducted by Narrative Health and funded by Merck, Sharp & Dohme (UK) Limited. This public awareness campaign was run across Greater Manchester in November 2020 in collaboration with Greater Manchester Cancer Alliance and the Northern Cancer Alliance and funded by Merck, Sharp & Dohme (UK) Limited. The project was the result of a large collaboration including The Roy Castle Lung Cancer Foundation, the UK Lung Cancer Coalition, Lung Cancer Nursing UK, Mesothelioma UK, Greater Manchester Cancer, Northern Cancer Alliance, and Merck, Sharp & Dohme (UK) Limited.

Footnotes

Contributors: All authors were involved in the development and delivery of the ‘Do It For Yourself’ campaign. All authors reviewed the content of the public insight work findings. ME drafted the initial draft of the manuscript and all coauthors reviewed and edited it.

Funding: There was no grant/award related to this work. This work was supported by funding for the public insight work and running the ‘Do It For Yourself’ campaign provided by Merck, Sharp & Dohme (UK) Limited.

Competing interests: None declared.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data availability statement

Not applicable.

Ethics statements

Patient consent for publication

Not required.

References

- 1.National Insititute for Health and Care Excellence . Lung cancer: diagnosis and management. NICE guideline [NG122]. NICE Clinical Guideline, 2019. Available: https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/ng122 [PubMed]

- 2.Royal College of Physicians . National lung cancer audit annual report 2018 (for audit period 2017). London: RCP, 2019. https://www.rcplondon.ac.uk/projects/outputs/nlca-annual-report-2018 [Google Scholar]

- 3.Public Health England . Cancer services, 2021. Available: https://fingertips.phe.org.uk/profile/cancerservices

- 4.Passaro A, Bestvina C, Velez Velez M, et al. Severity of COVID-19 in patients with lung cancer: evidence and challenges. J Immunother Cancer 2021;9:e002266. 10.1136/jitc-2020-002266 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Maringe C, Spicer J, Morris M, et al. The impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on cancer deaths due to delays in diagnosis in England, UK: a national, population-based, modelling study. Lancet Oncol 2020;21:1023–34. 10.1016/S1470-2045(20)30388-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.O’Dowd E, Succony L, Karahacioglu B, et al. Quantifying the impact of Covid-19 on lung cancer: an urgent need for restoration. Lung Cancer 2021;156:S15. 10.1016/S0169-5002(21)00234-8 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kennedy MPT, Cheyne L, Darby M, et al. Lung cancer stage-shift following a symptom awareness campaign. Thorax 2018;73:1128–36. 10.1136/thoraxjnl-2018-211842 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Physicians RCo . National lung cancer audit. spotlight report on curative intent treatment of stage I-IIIA non-small cell lung cancer RCP. London: RCP, 2020. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

Not applicable.