Key Points

Question

Can a novel multifaceted intervention prevent obesity in primary school children?

Findings

In this cluster randomized clinical trial involving 1392 children from 24 primary schools, a multifaceted intervention significantly reduced body mass index compared with the controls (mean between-group difference, −0.46 [calculated as weight in kilograms divided by height in square meters]). The prevalence of obesity decreased by 27% in the intervention group, compared with 6% in the controls.

Meaning

The multifaceted intervention was effective for preventing obesity in primary school children across socioeconomically distinct regions in China.

This cluster randomized clinical trial assesses the effectiveness of a multifaceted intervention for obesity prevention by promoting healthy diet and physical activity and engaging schools and families of primary school children in China.

Abstract

Importance

A rapid nutritional transition has caused greater childhood obesity prevalence in many countries, but the repertoire of effective preventive interventions remains limited.

Objective

To determine the effectiveness of a novel multifaceted intervention for obesity prevention in primary school children.

Design, Setting, and Participants

A cluster randomized clinical trial was conducted during a single school year (from September 11, 2018, to June 30, 2019) across 3 socioeconomically distinct regions in China according to a prespecified trial protocol. Twenty-four schools were randomly allocated (1:1) to the intervention or the control group, with 1392 eligible children aged 8 to 10 years participating. Data from the intent-to-treat population were analyzed from October 1 to December 31, 2019.

Interventions

A multifaceted intervention targeted both children (promoting healthy diet and physical activity) and their environment (engaging schools and families to support children’s behavioral changes). The intervention was novel in its strengthening of family involvement with the assistance of a smartphone app. The control schools engaged in their usual practices.

Main Outcomes and Measures

The primary outcome was the change in body mass index (BMI; calculated as weight in kilograms divided by height in square meters) from baseline to the end of the trial. Secondary outcomes included changes in adiposity outcomes (eg, BMI z score, prevalence of obesity), blood pressure, physical activity and dietary behaviors, obesity-related knowledge, and physical fitness. Generalized linear mixed models were used in the analyses.

Results

Among the 1392 participants (mean [SD] age, 9.6 [0.4] years; 717 boys [51.5%]; mean [SD] BMI, 18.6 [3.7]), 1362 (97.8%) with follow-up data were included in the analyses. From baseline to the end of the trial, the mean BMI decreased in the intervention group, whereas it increased in the control group; the mean between-group difference in BMI change was −0.46 (95% CI, −0.67 to −0.25; P < .001), which showed no evidence of difference across different regions, sexes, maternal education levels, and primary caregivers (parents vs nonparents). The prevalence of obesity decreased by 27.0% of the baseline figure (a relative decrease) in the intervention group, compared with 5.6% in the control group. The intervention also improved other adiposity outcomes, dietary, sedentary, and physical activity behaviors, and obesity-related knowledge, but it did not change moderate- to vigorous-intensity physical activity, physical fitness, or blood pressure. No adverse events were observed during the intervention.

Conclusions and Relevance

The multifaceted intervention effectively reduced the mean BMI and obesity prevalence in primary school children across socioeconomically distinct regions in China, suggesting its potential for national scaling.

Trial Registration

ClinicalTrials.gov Identifier: NCT03665857

Introduction

The global prevalence of obesity among children and adolescents has increased 8-fold in the last 4 decades.1 This prevalence has recently plateaued at a high level in high-income countries, but it continues to accelerate in low- and middle-income countries, including China.1,2 The prevalence of overweight and obesity in Chinese school-aged children increased from 5.3% in 1985 to 20.5% in 2014.2 Childhood obesity can affect a child’s physical and psychological health,3 academic attainment,4 and quality of life.5 In the longer term, it can also increase the risk of cardiometabolic diseases, musculoskeletal problems, and cancers.6,7

A recent review reported that obesity interventions combining diet and physical activity elements had small associations with reducing body mass index (BMI) z scores (−0.05; 95% CI, −0.10 to −0.01) in children aged 6 to 12 years but did not affect BMI (calculated as weight in kilograms divided by height in square meters).8 Most of the studies in this review were from the US or Europe; very few were from low- and middle-income countries, and none were from China.8 Recently, 2 large, rigorously designed cluster randomized clinical trials (RCTs) from the UK9,10 found that school-based interventions did not bring about reductions in BMI or other indices of obesity.

China’s recent economic growth has been accompanied by a rapid increase in overweight and obesity among school-aged children and growing interest in their prevention.2 Earlier obesity intervention studies in Chinese school-aged children were generally poorly evaluated with methodological flaws.11,12 Subsequent school-based obesity prevention studies in China had inconsistent findings.13,14,15,16,17 Although multifaceted interventions have generally shown greater promise than single-intervention approaches,11 there is little clarity regarding the optimal multifaceted approach and how effective it might be.18 Meta-analyses have shown that high levels of family involvement are accompanied by greater reductions in obesity than minimal or no family involvement.19 However, the effect of a multifaceted intervention with high levels of family involvement is unknown, because most obesity intervention studies in China have not evaluated the actual extent of family involvement during the process of intervention implementation.13,14,15,16 Moreover, each of these studies took place in a single developed city (Shanghai,13 Nanjing,14,15 Beijing,16 and Guangzhou17), limiting generalizability.

For these reasons, we developed a novel multifaceted intervention aimed at maintaining a healthy BMI in primary school children by not only promoting healthy diet and physical activity but also engaging schools and families.20 In this report, we present the findings from a cluster RCT in 3 distinct socioeconomic regions of China.

Methods

Study Design and Participants

The Diet, Exercise and Cardiovascular Health–Children (DECIDE-Children) study was a cluster RCT that was prespecified in the previously published study protocol20 (also available in Supplements 1 and 2). We selected 3 socioeconomically distinct regions in China from the eastern (Beijing), central (Changzhi, in Shanxi Province), and western (Urumuqi, in Xinjiang Province) parts of the country. A total of 24 primary schools were selected, with 8 schools in each region (eFigure 1 in Supplement 3). We recruited 1 or 2 grade 4 classes from each school, depending on class size, to ensure that approximately 50 children aged 8 to 10 years were included per school. Written informed consent was obtained from children and their parents and/or guardians. Children were eligible for inclusion in the study if they met health status criteria (eg, no medical history of serious diseases and able to participate in sports; see details in the protocol20). Ethical approval was granted by the Peking University Institutional Review Board. This study followed the Consolidated Standards of Reporting Trials (CONSORT) reporting guideline.

Randomization

After completing baseline assessments, the 24 schools were randomly allocated at a 1:1 ratio to either the intervention or control group, stratified by district within each region (eFigure 1 in Supplement 3). The randomization was centrally performed by a researcher at the Clinical Research Institute of Peking University who was blinded to the schools.

Intervention

After systematic reviews,9,10,11,12,13,14,15,16,17,21 focus group discussions and interviews with key stakeholders, and a pilot study,22 we developed a multifaceted intervention based on the social ecological model23 that included 3 components targeting children to promote a healthy diet and physical activity (health education, reinforcement of physical activity, and BMI monitoring and feedback) and 2 components targeting the children’s environment (engaging schools and families to support children’s behavioral changes). The intervention was novel in that it strengthened family involvement with the assistance of a smartphone app. The intervention was implemented during a single school year (9 months) from September 11, 2018, to June 30, 2019. We briefly describe the 5 components below (see details in eTables 1 and 2 in Supplement 3).

Three Components Targeting Children

Health Education

One teacher per class was trained by the project staff and then delivered 10 sessions to children in their usual health education lessons (once every 2-3 weeks). The following 5 core messages (termed 2 not, 2 less, and 1 more) were systematically delivered to the children in a simple and understandable manner:

not eating excessively;

not drinking sugar-sweetened beverages;

less high-energy food;

less sedentary time; and

more physical activities.

Reinforcement of Physical Activity and BMI Monitoring and Feedback

The physical education teachers instructed the children to perform 1-hour moderate- to vigorous-intensity physical activity per day within school. The trained teachers measured each child’s weight and height every month and then input the data into a software system for a smartphone application (Eat Wisely and Move Happily). The children were told to use the application on their caregivers’ phones to view the feedback, which included the current BMI and category (underweight, normal weight, overweight, or obesity24,25) and changes in BMI from the last month to the present. In addition, the teacher used a weight scale in each class to perform weekly measurements, letting each child know her or his weight without disclosure to the class.

Two Components Targeting Environment

Engaging Schools to Support Children’s Behavioral Changes

At the beginning of the intervention, the project staff provided instruction regarding the intervention to the school principals and grade 4 teachers. Several school policies (ie, not selling, eating, or buying unhealthy snacks or sugar-sweetened beverages within the school) were implemented. Schools also ensured curriculum time for health education and physical education at school.

Engaging Families to Support Children’s Behavioral Changes

The parents received 5 core messages through 3 face-to-face health education sessions at the beginning and middle of the first semester and at the beginning of the second semester. They were encouraged to promote healthy diet and physical activity for their children outside school. They were trained to use the application to track the feedback from their children’s monthly BMI monitoring, help their children to record their behaviors related to “2 not, 2 less, and 1 more” weekly, view autofeedback on behavioral progress and problems, and encourage their children to make behavioral changes. This combination of BMI and behavioral monitoring was an individually tailored component of the intervention that included goal setting, self-monitoring, and problem solving.

Control Group

The 12 control schools continued with their usual health education lessons and physical education sessions. They did not focus on obesity.

Assessments

Baseline assessments were conducted in September 2018 before randomization. Two follow-up assessments were undertaken in January 2019 (middle of trial) and June 2019 (end of trial). Identical procedures were used for all assessments and were performed by trained staff according to a standard protocol. The instruments, methods of assessment, and their associated outcomes are presented in eTable 3 in Supplement 3. Briefly, adiposity outcomes were measured by physical examination, which included height, weight, waist and hip circumference, and body fat percentage; behavioral and knowledge outcomes were assessed by self-reported questionnaires; physical fitness was measured via performance of rope jumps, shuttle run, long standing jump, and sit-ups; and systolic and diastolic blood pressure were assessed. The staff who measured the children’s weight and height were blinded to school allocation.

The primary outcome was the change in BMI from baseline to the end of the trial. The secondary outcomes included changes in adiposity outcomes (eg, BMI z score, prevalence of obesity), physical activity and dietary behaviors, obesity-related knowledge, physical fitness, and blood pressure. Overweight/obesity was defined using age- and sex-specific BMI percentiles according to Chinese reference values24 and BMI z scores above 1 or 2 according to World Health Organization (WHO) reference values.26 Adverse events included injury related to physical activity, body image dissatisfaction, underweight, and reduced growth in height.

Process Evaluation

We used various methods to collect the process data, including dose delivered (eg, frequency and intensity of the actual implementation of intervention components) and dose received (eg, attendance rates of children and parents, frequency of application use by parents). Details are given in eMethods in Supplement 3.

Sample Size Calculation

We assumed an intervention effect size for a BMI of 0.50, an SD of 1.40, an intracluster correlation coefficient of 0.05, and an attrition rate of 10%.11 A total of 1200 children from 24 schools (clusters) with a mean cluster size of 50 children per school was estimated to detect the assumed effect size with 88% power at α = .05.

Statistical Analyses

Data were analyzed from October 1 to December 31, 2019. We conducted the primary outcome analysis with children for whom BMI data at both baseline and the end of the trial were available. Participants without BMI data at the end of the trial (30 [2.2%]) were excluded in the main analysis according to the prespecified protocol (missing rate <5%).20 For sensitivity analysis, we used multiple imputation by chained equations to account for missing BMI values at the end of the trial. To determine the effect size of the intervention, we used generalized linear mixed models that included school-level random intercepts to account for the correlation due to clustering of children within schools, which was the level at which the intervention was assigned. In these models, we adjusted for important factors associated with adiposity, including baseline values of the outcome measures (eg, baseline BMI), age, and sex. We further conducted 5 prespecified subgroup analyses to assess whether the effect differed by region, sex, maternal educational attainment, baseline BMI status, or primary caregiver (parent vs nonparent). We used interaction terms between each subgroup variable and group assignment (intervention or control) to examine whether the intervention effects varied by subgroups. We defined overweight/obesity using the Chinese reference values in the main analyses and the WHO reference values in the sensitivity analyses. To explore whether family involvement influenced the effect size, we analyzed the associations between parental frequency of application use and children’s BMI change in the intervention group (eMethods in Supplement 3). Statistical significance was determined by a 2-sided P < .05. Statistical analyses were performed using SAS, version 9.4 (SAS Institute Inc).

Results

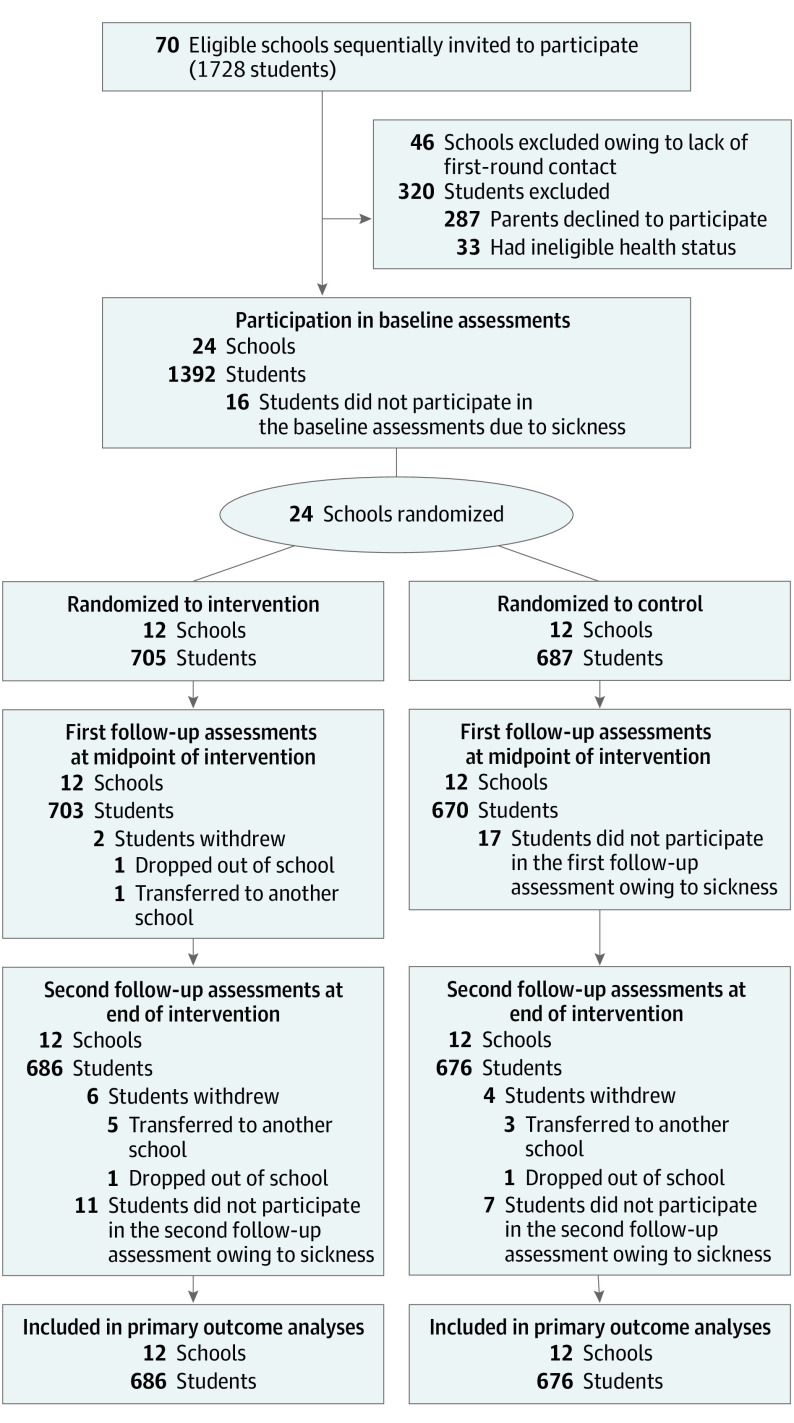

Of the 1728 children in grade 4 in the 24 recruited schools, 1408 (81.5%) were eligible (Figure 1), and 1392 (98.9%) completed the baseline assessments. Thirty of 1392 children (2.2%) were lost to follow-up by the end of the trial. Finally, the primary outcome analysis involved 1362 children (686 in the intervention group and 676 controls). At baseline, 675 (48.5%) of the children were girls and 717 (51.5%) were boys, and the mean (SD) age was 9.6 (0.4) years. The mean (SD) baseline BMI was 18.6 (3.7). The baseline characteristics were similar in the intervention and control groups (Table 1). We compared baseline characteristics of children included in the primary outcome analysis (n = 1362) with those of children lost to follow-up (n = 30) by the end of the trial, and the results showed no evidence of differences between them (eTable 4 in Supplement 3).

Figure 1. Flow Diagram of Study Selection.

Table 1. Baseline Characteristics of Schools and Children.

| Characteristic | Study groupa | |

|---|---|---|

| Intervention | Control | |

| Cluster level | ||

| No. of schools | 12 | 12 |

| No. of children/school, median (range) | 58 (46-75) | 56 (48-69) |

| Individual level | ||

| No. of children | 705 | 687 |

| Region | ||

| Beijing | 260 (36.9) | 232 (33.8) |

| Changzhi, Shanxi Province | 200 (28.4) | 200 (29.1) |

| Urumuqi, Xinjiang Province | 245 (34.8) | 255 (37.1) |

| Sex | ||

| Boys | 353 (50.1) | 364 (53.0) |

| Girls | 352 (49.9) | 323 (47.0) |

| Primary caregiverb | ||

| Parents | 655 (95.1) | 652 (96.2) |

| Nonparents | 34 (4.9) | 26 (3.8) |

| Maternal educational levelc | ||

| High school or below | 277 (40.4) | 272 (42.4) |

| Above high school | 408 (59.6) | 370 (57.6) |

| Mean (SD) | ||

| Age, y | 9.6 (0.4) | 9.6 (0.4) |

| Height, cm | 140.0 (6.6) | 139.8 (6.5) |

| Weight, kg | 36.6 (9.5) | 37.0 (9.5) |

| BMI | 18.5 (3.7) | 18.8 (3.7) |

| BMI z score | 0.7 (1.4) | 0.8 (1.4) |

Abbreviation: BMI, body mass index (calculated as weight in kilograms divided by height in square meters).

Unless otherwise indicated, data are expressed as number (%) of patients. Percentages have been rounded and may not total 100.

Missing values for 25 (1.8%).

Missing values for 65 (4.7%).

Primary Outcome

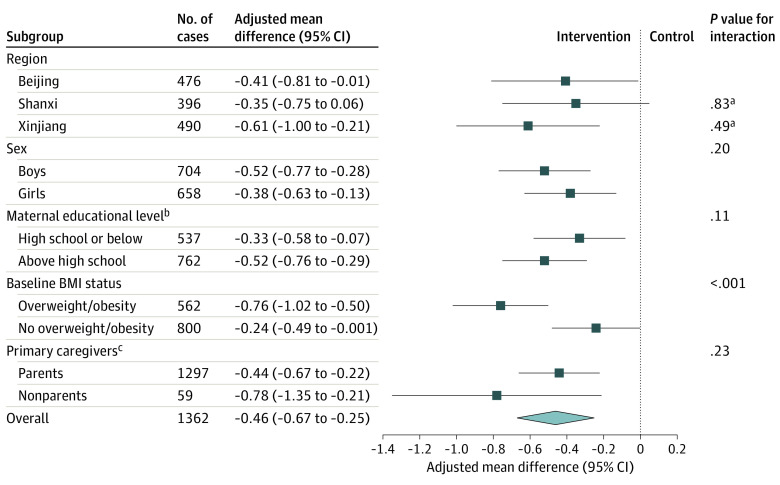

From baseline to the end of the trial, the mean BMI decreased in the intervention group, whereas it increased in the control group (mean between-group difference, −0.46 [95% CI, −0.67 to −0.25]; P < .001) (Table 2). The result remained unchanged when we used multiple imputation to impute 30 missing values for the BMI at the end of the trial (mean between-group difference, −0.46 [95% CI, −0.67 to −0.24]; P < .001). As shown in Figure 2, the effect size did not differ significantly by region, sex, maternal educational attainment, or primary caregiver but was stronger among children who had overweight or obesity at baseline than among those who did not (adjusted mean difference, −0.76 [95% CI, −1.02 to −0.50] vs −0.24 [95% CI, −0.49 to −0.001]; P < .001 for interaction).

Table 2. Intervention Effects on Primary and Secondary Outcomes.

| Outcomes | No. in intervention/control group | Intervention group | Control group | Intervention vs control adjusted mean difference/OR (95% CI)a |

||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Baseline | End of trial | Baseline | End of trial | |||

| Primary outcome | ||||||

| BMI, mean (SD) | 686/676 | 18.5 (3.7) | 18.4 (3.7) | 18.8 (3.7) | 19.0 (4.0) | −0.46 (−0.67 to −0.25) |

| Secondary outcomes | ||||||

| Adiposity | ||||||

| BMI z score, mean (SD) | 686/676 | 0.7 (1.4) | 0.4 (1.4) | 0.8 (1.4) | 0.7 (1.4) | −0.17 (−0.25 to −0.09) |

| Body fat percentage, mean (SD) | 686/676 | 20.69 (10.42) | 18.80 (9.77) | 21.11 (10.48) | 20.22 (10.23) | −1.05 (−1.83 to −0.28) |

| Waist circumference, mean (SD), cm | 686/676 | 65.1 (10.2) | 64.4 (10.6) | 65.7 (11.1) | 66.4 (10.9) | −1.63 (−2.82 to −0.43) |

| Waist-to-hip ratio, mean (SD) | 686/671 | 0.86 (0.06) | 0.84 (0.07) | 0.86 (0.06) | 0.85 (0.07) | −0.01 (−0.02 to 0.01) |

| Obesity (using Chinese reference), No. (%)b | 686/676 | 158 (23.0) | 115 (16.8) | 168 (24.9) | 159 (23.5) | 0.34 (0.18 to 0.64) |

| Obesity (using WHO reference), No. (%)c | 686/676 | 138 (20.1) | 102 (14.9) | 157 (23.2) | 144 (21.3) | 0.40 (0.23 to 0.70) |

| Overweight/obesity (using Chinese reference), No. (%)b | 686/676 | 266 (38.8) | 215 (31.3) | 296 (43.8) | 271 (40.1) | 0.52 (0.31 to 0.85) |

| Overweight/obesity (using WHO reference), No. (%)c | 686/676 | 291 (42.4) | 264 (38.5) | 309 (45.7) | 297 (43.9) | 0.53 (0.32 to 0.87) |

| Physical activity and dietary behaviors | ||||||

| In the action stage of behavior change, No. (%)d | 678/668 | 267 (39.4) | 498 (73.5) | 254 (38.0) | 330 (49.4) | 3.63 (2.28 to 5.76) |

| Not drinking sugar-sweetened beverages, No. (%) | 678/662 | 406 (59.9) | 515 (76.0) | 417 (63.0) | 348 (52.6) | 3.26 (2.00 to 5.33) |

| Not eating fried food, No. (%) | 684/674 | 294 (43.0) | 412 (60.2) | 323 (47.9) | 264 (39.2) | 2.60 (1.78 to 3.79) |

| Not eating Western fast food, No. (%) | 630/622 | 502 (79.7) | 564 (89.5) | 501 (80.5) | 473 (76.0) | 2.79 (1.96 to 3.98) |

| Screen time <2 h/d, No. (%) | 684/667 | 543 (79.4) | 608 (88.9) | 529 (79.3) | 547 (82.0) | 1.83 (1.16 to 2.89) |

| Daily physical activity (together with parents), mean (SD), d/wk | 656/612 | 1.9 (1.6) | 3.2 (2.2) | 2.2 (1.9) | 2.4 (1.8) | 0.92 (0.30 to 1.55) |

| Daily MVPA ≥1 h, mean (SD), d/wk | 627/649 | 2.9 (2.3) | 4.0 (2.5) | 2.9 (2.2) | 3.9 (2.4) | 0.12 (−0.47 to 0.72) |

| Emotional overeating, mean (SD), score point | 633/614 | 7.7 (2.5) | 7.6 (2.6) | 7.9 (2.5) | 8.0 (2.8) | −0.24 (−0.58 to 0.10) |

| Satiety responsiveness, mean (SD), score point | 634/615 | 13.1 (3.3) | 13.0 (3.5) | 13.0 (3.5) | 12.9 (3.3) | −0.15 (−0.50 to 0.20) |

| Obesity-related knowledge | ||||||

| Obesity-related knowledge, mean (SD), score point | 686/675 | 6.8 (1.3) | 7.4 (1.0) | 6.9 (1.2) | 7.1 (1.1) | 0.36 (0.21 to 0.51) |

| Physical fitness, mean (SD) | ||||||

| No. of rope jumps within 1 min | 663/659 | 94.4 (40.1) | 116.1 (35.9) | 91.2 (34.9) | 100.7 (34.7) | 12.55 (3.12 to 21.97) |

| Duration of shuttle run (50 m ×8), s | 648/647 | 130.4 (22.7) | 115.4 (17.1) | 128.1 (21.2) | 123.5 (21.2) | −8.97 (−19.08 to 1.15) |

| Distance of long standing jump, cm | 673/657 | 140.5 (19.5) | 151.3 (19.3) | 142.8 (18.8) | 151.7 (19.8) | 0.68 (−4.94 to 6.29) |

| No. of sit-ups within 1 min | 658/654 | 29.1 (12.4) | 33.3 (9.8) | 28.4 (11.1) | 33.0 (10.9) | −0.21 (−2.99 to 2.56) |

| Blood pressure, mean (SD), mm Hg | ||||||

| SBP | 686/676 | 103.3 (9.9) | 101.9 (8.5) | 103.0 (9.4) | 102.3 (8.8) | −0.60 (−2.76 to 1.56) |

| DBP | 686/674 | 58.6 (6.8) | 56.9 (6.5) | 58.1 (6.7) | 57.2 (6.2) | −0.54 (−2.12 to 1.04) |

Abbreviations: BMI, body mass index (calculated as weight in kilograms divided by height in square meters); DBP, diastolic blood pressure; MVPA, moderate to vigorous physical activity; OR, odds ratio; SBP, systolic blood pressure; WHO, World Health Organization.

Generalized linear mixed models allowing for the school-clustering effect were used to analyze outcomes, with adjustment for baseline values of the outcomes, age, and sex. Mean (SD) data are calculated as mean between-group difference; number (%), as OR.

Defined using age- and sex-specific BMI percentiles according to Chinese reference.

Defined by BMI z score of at least 1 or at least 2 according to WHO reference.

Includes children actually initiating behavioral change, compared with those in the precontemplation (ie, not thinking about becoming engaged in the behavior change) or contemplation (ie, not involved in the behavior change but was considering getting involved in the behavior in the near future) stage.

Figure 2. Subgroup Analyses of Intervention Effects on the Primary Outcome.

BMI indicates body mass index.

aCompared with Beijing.

bMissing 63 values (4.6%).

cMissing 6 values (0.4%).

Secondary Outcomes

The intervention improved the BMI z score (mean between-group difference at midpoint, −0.11 [95% CI, −0.19 to −0.03]; at the end of the trial, −0.17 [95% CI, −0.25 to −0.09]) and other adiposity outcomes such as body fat percentage (mean between-group difference at the end of the trial, −1.05 [95% CI, −1.83 to −0.28]) and waist circumference (mean between-group difference at midpoint, −1.58 [95% CI, −2.78 to −0.38]; at the end of the trial, −1.63 [95% CI, −2.82 to −0.43]) (eTable 5 in Supplement 3 and Table 2). The prevalence of obesity decreased by 27.0% of the baseline figure (a relative decrease) in the intervention group compared with 5.6% in the control group, with an odds ratio of 0.34 (95% CI, 0.18-0.64).

Post hoc analyses showed that the intervention group had a higher remission of obesity than the control group (45 of 158 [28.5%] vs 24 of 168 [14.3%]) (eFigure 2 and eTable 6 in Supplement 3). There was no difference in the incidence of obesity between the 2 groups (2 of 528 [0.4%] vs 15 of 508 [3.0%]) (eFigure 2 and eTable 7 in Supplement 3). Compared with the control group, the right tail of the distribution curve shifted more obviously to the left in the intervention group, consistent with a decreased prevalence of obesity (eFigure 3 in Supplement 3). The sensitivity analyses using the WHO reference showed similar results (Table 2 and eTables 5-7 in Supplement 3).

Table 2 illustrates the behavioral changes in the intervention group compared with the control group. Dietary behaviors (not consuming sugar-sweetened beverages [OR, 3.26; 95% CI, 2.00-5.33], fried food [OR, 2.60; 95% CI, 1.78-3.79], and Western fast food [OR, 2.79; 95% CI, 1.96-3.98]), screen time of less than 2 hours per day (OR, 1.83; 95% CI, 1.16-2.89), physical activity together with parents (adjusted mean difference, 0.92; 95% CI, 0.30-1.55), as well as obesity-related knowledge (adjusted mean difference, 0.36; 95% CI, 0.21-0.51) improved in the intervention group compared with the controls. However, moderate- to vigorous-intensity physical activity (adjusted mean difference, 0.12; 95% CI, −0.47 to 0.72) and physical fitness parameters (eg, adjusted mean difference in distance of long standing jump, 0.68 [95% CI, −4.94 to 6.29] cm) did not differ between the 2 groups, except for rope jumps (adjusted mean difference, 12.55; 95% CI, 3.12 to 21.97). There was no difference between groups in systolic (adjusted mean difference, −0.60; 95% CI, −2.76 to 1.56) or diastolic (adjusted mean difference, −0.54; 95% CI, −2.12 to 1.04) blood pressure (Table 2).

Adverse Events

There were no reports from the children or parents of injuries related to physical activity. Body image dissatisfaction and other indicators of adverse events did not differ between the 2 groups (eTable 8 in Supplement 3).

Process Evaluation

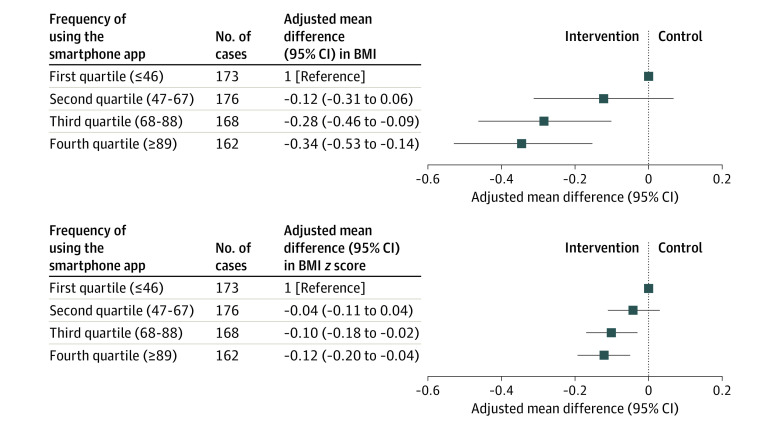

The intervention was implemented at 12 intervention schools with high fidelity to most of the components (>80%), except for reinforcement of physical activity at school (6 of 12 schools, <80%) and outside of school (66% often/ always) (eTable 9 in Supplement 3). The frequency of parental application use was positively associated with changes in BMI: children of parents in the fourth quartile of application use had the greatest reduction in BMI compared with children of parents in the first quartile of application use (adjusted mean difference, −0.34; 95% CI, −0.53 to −0.14) (Figure 3).

Figure 3. Associations Between Parental Frequency of Using the Smartphone Application and Change in Body Mass Index (BMI).

BMI is calculated as weight in kilograms divided by height in square meters. Generalized linear mixed models allowing for the school-clustering effect were used to analyze outcomes, with adjustment for baseline outcome values and age and sex of children.

Discussion

This systematically developed, rigorously designed, multifaceted intervention effectively reduced mean BMI and obesity prevalence in primary school–aged children in China. The effect size showed no evidence of difference across regions, sexes, maternal educational levels, and primary caregivers but was stronger among children who already had overweight or obesity at baseline. The intervention also reduced other adiposity outcomes (eg, BMI z score) and improved dietary, sedentary, and physical activity behaviors and obesity-related knowledge, but it did not change moderate to vigorous physical activity, physical fitness, or blood pressure.

Although the prevalence of obesity in children is rising worldwide, progress in childhood obesity prevention has been slow.18 Previous obesity interventions in children aged 6 to 12 years have had little effect on reducing BMI z scores.8 Family involvement appeared particularly important for children younger than 12 years.27 However, previous school-based obesity interventions have to some extent failed to engage families. For example, 2 well-designed cluster RCTs in the UK9,10 implemented school-based obesity interventions but failed to reduce BMI. The failure of these earlier interventions might be due in part to relatively low family involvement (ie, 59%9,28 or 48%10 of parents not attending the intervention sessions).29 Another Chinese intervention17 reported 88% of family members attending the health education workshops, but family was not engaged in monitoring BMI and behaviors via the mobile health technology. Our study designed a variety of intervention components (health education, BMI monitoring, and app-assisted behavioral monitoring) to facilitate parental engagement, leading to a high level of parental participation rates (87.0%-99.7%) in all these intervention components.

The intervention was also novel in its combination of BMI and behavioral monitoring to improve parental engagement. A recent systematic review30 reported that more than half of children who had overweight were incorrectly perceived by their parents as having normal weight. Parental misperception has been linked to lower motivation to promote a child’s behavioral change.31 In our intervention, the application regularly sent feedback on the child’s BMI and behaviors to the parents, and the frequency of parental application use was positively associated with changes in the child’s BMI, suggesting that this individually tailored intervention was acceptable and useful for most parents, who could promptly understand their child’s progress and problems with BMI and related behaviors and continuously promote behavioral changes.

Based on a recent systematic review of technology-based RCTs,32 our intervention is, to our knowledge, the first RCT to show effective BMI reduction using an app-assisted multifaceted approach that includes both BMI monitoring and family involvement. A recent US study reported that BMI monitoring alone did not reduce adiposity in children and called for more comprehensive interventions using the school as a platform.33 Another recent Chinese obesity intervention that used behavioral recording but not BMI monitoring17 was effective only in girls. Our research team previously conducted a similar multifaceted obesity intervention (ie, no BMI monitoring) and found no effect on BMI.16 These findings suggest that, at least within the context of the educational system and families in China, BMI monitoring is a potentially important component of multifaceted interventions to reduce obesity in children.

The trial’s success carries implications for obesity prevention.34 A modest shift in mean BMI produced a marked reduction in the proportion of cases with obesity at the tail of distribution.35 A reduction in the BMI z score as small as 0.1 U can improve cardiometabolic risk in children who have overweight or obesity.36 Moreover, the intervention may change trajectories toward obesity among children aged 8 to 10 years around the time of the metabolic changes that accompany puberty. Children with an above-average BMI at 7 to 13 years of age had an elevated risk of type 2 diabetes in adulthood,37 but if remission occurred before 13 years, the risk of type 2 diabetes in adulthood decreased to a level similar to that of children who had never had overweight.38 Furthermore, this intervention was effective across socioeconomically distinct regions, suggesting its potential for widespread adoption across the country.

There are reasons to think that our findings may be relevant for policy-making in countries other than China. The intervention was effective for reducing BMI in 3 socioeconomically distinct regions of China, consistent with its utility across different levels of economic development. Moreover, the intervention components were adapted to schools’ usual health education and physical education curricula, thus supporting easy scalability. School-based interventions are becoming more relevant as children spend more time in school, but one challenge remains the greater priority given to academic achievement over physical fitness by both schools and families. In the Chinese educational context of obesity prevention not receiving the same attention given to infectious disease control, an app-assisted approach might be acceptable, timely, and effective in China and elsewhere.

Strengths and Limitations

The main strength of the study intervention lies in its multifaceted nature that targets both children and their environment. To promote a healthy diet and physical activity in children, we improved the children’s knowledge and skills through (1) behavior-change messages delivered by classroom teachers during health education lessons, (2) the promotion of physical activity at schools by physical education teachers, and (3) regular BMI and behavioral monitoring and feedback. At the environment level, the intervention not only engaged schools in implementing supportive policies but also engaged families. The trial was effective across multiple socioeconomically distinct regions in China. Other notable strengths of the study included its sample size, baseline assessments before randomization, blinding of the primary outcome measurements, low attrition, prespecified data analysis plan, and process evaluation.

The study has some limitations. First, information on obesity-related behaviors was reported by the children or parents, raising the possibility of social desirability bias. The study was limited by lack of objectively assessed physical activity data among all participants owing to the limited research fund. The 24-hour dietary recall method tends to be time consuming and resource intensive, limiting its application. However, changes in behavioral measures paralleled the changes in objective measures of adiposity. Second, although the intervention was effective in improving dietary, sedentary, and physical activity behaviors, we observed no improvement in moderate to vigorous physical activity, similar to other reports.39 The WHO has recommended that children engage in no less than 60 min/d of moderate to vigorous physical activity.40 Future studies are needed to develop specific interventions to make children be physically active at a satisfactory intensity. Third, fidelity of implementation for the physical activity component was not optimal. Difficulties in its implementation might be related to prioritizing academic performance over physical activity.

Conclusions

The multifaceted intervention effectively reduced mean BMI and obesity prevalence in primary school children across socioeconomically distinct regions of China. Further studies are needed to assess the generalizability of the intervention in countries other than China.

Trial Protocol

Statistical Analysis Plan

eMethods. Additional Description

eTable 1. Description of the Multifaceted Intervention Components

eTable 2. Outline of the Health Education Activities for Children

eTable 3. Measurements and Their Associated Outcome Variables

eTable 4. Comparison of Children Included in the Primary Outcome Analysis (n=1362) and Those Lost to Follow-up (n=30) by Baseline Characteristics

eTable 5. Intervention Effects on Secondary Outcomes at Middle of Intervention

eTable 6. Intervention Effects on Remission of Overweight/Obesity at Middle and End of the Intervention

eTable 7. Intervention Effects on Incidence of Overweight/Obesity at Middle and End of the Intervention

eTable 8. Outcomes of Adverse Events at the End of the Intervention

eTable 9. Implementation of the Multifaceted Intervention Components

eFigure 1. Random Allocation of Schools to the Intervention or Control Group Within 5 Districts (Strata)

eFigure 2. The Remission and Incidence of Obesity in the Intervention and Control Groups

eFigure 3. The Distribution of BMI z Score at Baseline and End of the Intervention in the Intervention (A) and Control (B) Groups

eReferences

Data Sharing Statement

References

- 1.NCD Risk Factor Collaboration (NCD-RisC) . Worldwide trends in body-mass index, underweight, overweight, and obesity from 1975 to 2016: a pooled analysis of 2416 population-based measurement studies in 128·9 million children, adolescents, and adults. Lancet. 2017;390(10113):2627-2642. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(17)32129-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Dong Y, Jan C, Ma Y, et al. Economic development and the nutritional status of Chinese school-aged children and adolescents from 1995 to 2014: an analysis of five successive national surveys. Lancet Diabetes Endocrinol. 2019;7(4):288-299. doi: 10.1016/S2213-8587(19)30075-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Pulgarón ER. Childhood obesity: a review of increased risk for physical and psychological comorbidities. Clin Ther. 2013;35(1):A18-A32. doi: 10.1016/j.clinthera.2012.12.014 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Booth JN, Tomporowski PD, Boyle JM, et al. Obesity impairs academic attainment in adolescence: findings from ALSPAC, a UK cohort. Int J Obes (Lond). 2014;38(10):1335-1342. doi: 10.1038/ijo.2014.40 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Halasi S, Lepeš J, Đorđić V, et al. Relationship between obesity and health-related quality of life in children aged 7-8 years. Health Qual Life Outcomes. 2018;16(1):149. doi: 10.1186/s12955-018-0974-z [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ward ZJ, Long MW, Resch SC, Giles CM, Cradock AL, Gortmaker SL. Simulation of growth trajectories of childhood obesity into adulthood. N Engl J Med. 2017;377(22):2145-2153. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1703860 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Geng T, Smith CE, Li C, Huang T. Childhood BMI and adult type 2 diabetes, coronary artery disease, chronic kidney disease, and cardiometabolic traits: a mendelian randomization analysis. Diabetes Care. 2018;41(5):1089-1096. doi: 10.2337/dc17-2141 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Brown T, Moore THM, Hooper L, et al. Interventions for preventing obesity in children. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2019;7(7):CD001871.doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD001871.pub4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Adab P, Pallan MJ, Lancashire ER, et al. Effectiveness of a childhood obesity prevention programme delivered through schools, targeting 6 and 7 year olds: cluster randomised controlled trial (WAVES study). BMJ. 2018;360:k211. doi: 10.1136/bmj.k211 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lloyd J, Creanor S, Logan S, et al. Effectiveness of the Healthy Lifestyles Programme (HeLP) to prevent obesity in UK primary-school children: a cluster randomised controlled trial. Lancet Child Adolesc Health. 2018;2(1):35-45. doi: 10.1016/S2352-4642(17)30151-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Feng L, Wei DM, Lin ST, et al. Systematic review and meta-analysis of school-based obesity interventions in mainland China. PLoS One. 2017;12(9):e0184704. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0184704 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Uijtdewilligen L, Waters CN, Müller-Riemenschneider F, Lim YW. Preventing childhood obesity in Asia: an overview of intervention programmes. Obes Rev. 2016;17(11):1103-1115. doi: 10.1111/obr.12435 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Cao ZJ, Wang SM, Chen Y. A randomized trial of multiple interventions for childhood obesity in China. Am J Prev Med. 2015;48(5):552-560. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2014.12.014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Xu F, Ware RS, Leslie E, et al. Effectiveness of a randomized controlled lifestyle intervention to prevent obesity among Chinese primary school students: CLICK-Obesity Study. PLoS One. 2015;10(10):e0141421. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0141421 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Wang Z, Xu F, Ye Q, et al. Childhood obesity prevention through a community-based cluster randomized controlled physical activity intervention among schools in China: the health legacy project of the 2nd World Summer Youth Olympic Games (YOG-Obesity study). Int J Obes (Lond). 2018;42(4):625-633. doi: 10.1038/ijo.2017.243 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Liu Z, Li Q, Maddison R, et al. A school-based comprehensive intervention for childhood obesity in China: a cluster randomized controlled trial. Child Obes. 2019;15(2):105-115. doi: 10.1089/chi.2018.0251 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Li B, Pallan M, Liu WJ, et al. The CHIRPY DRAGON intervention in preventing obesity in Chinese primary-school–aged children: a cluster-randomised controlled trial. PLoS Med. 2019;16(11):e1002971. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.1002971 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.World Health Organization . Report of the Commission on Ending Childhood Obesity. Implementation Plan: Executive Summary. World Health Organization; 2017. Accessed December 20, 2019. http://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/handle/10665/259349/WHO-NMH-PND-ECHO-17.1-eng.pdf?sequence=1&isAllowed=y2017

- 19.Kobes A, Kretschmer T, Timmerman G, Schreuder P. Interventions aimed at preventing and reducing overweight/obesity among children and adolescents: a meta-synthesis. Obes Rev. 2018;19(8):1065-1079. doi: 10.1111/obr.12688 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Liu Z, Wu Y, Niu WY, et al. ; Study Team for the DECIDE-Children Study . A school-based, multi-faceted health promotion programme to prevent obesity among children: protocol of a cluster-randomised controlled trial (the DECIDE-Children study). BMJ Open. 2019;9(11):e027902. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2018-027902 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Liu Z, Xu HM, Wen LM, et al. A systematic review and meta-analysis of the overall effects of school-based obesity prevention interventions and effect differences by intervention components. Int J Behav Nutr Phys Act. 2019;16(1):95. doi: 10.1186/s12966-019-0848-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lin L, Li C, Gao A, et al. Effect of a comprehensive school-based intervention on childhood obesity [in Chinese]. Chinese J School Health. 2018;39(10):1505-1508. doi: 10.16835/j.cnki.1000-9817.2018.10.019 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Sallis J, Owen N, Fisher E. Ecological models of health behavior. In: Glanz K, Rimer B, Viswanath K, ed. Health Behavior and Health Education. Jossey-Bass; 2008:465-485. [Google Scholar]

- 24.National Health Commission of the People's Republic of China . Screening for Overweight and Obesity Among School-Age Children and Adolescents. National Health Commission of the People's Republic of China ; 2018. [Google Scholar]

- 25.National Health Commission of the People's Republic of China . Screening Standard for Malnutrition of School-Age Children and Adolescents. National Health Commission of the People's Republic of China; 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 26.de Onis M, Onyango AW, Borghi E, Siyam A, Nishida C, Siekmann J. Development of a WHO growth reference for school-aged children and adolescents. Bull World Health Organ. 2007;85(9):660-667. doi: 10.2471/BLT.07.043497 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ho M, Garnett SP, Baur L, et al. Effectiveness of lifestyle interventions in child obesity: systematic review with meta-analysis. Pediatrics. 2012;130(6):e1647-e1671. doi: 10.1542/peds.2012-1176 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Griffin TL, Clarke JL, Lancashire ER, Pallan MJ, Adab P; WAVES study trial investigators . Process evaluation results of a cluster randomised controlled childhood obesity prevention trial: the WAVES study. BMC Public Health. 2017;17(1):681. doi: 10.1186/s12889-017-4690-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Okely AD, Hammersley ML. School-home partnerships: the missing piece in obesity prevention? Lancet Child Adolesc Health. 2018;2(1):5-6. doi: 10.1016/S2352-4642(17)30154-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Rietmeijer-Mentink M, Paulis WD, van Middelkoop M, Bindels PJ, van der Wouden JC. Difference between parental perception and actual weight status of children: a systematic review. Matern Child Nutr. 2013;9(1):3-22. doi: 10.1111/j.1740-8709.2012.00462.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Rhee KE, De Lago CW, Arscott-Mills T, Mehta SD, Davis RK. Factors associated with parental readiness to make changes for overweight children. Pediatrics. 2005;116(1):e94-e101. doi: 10.1542/peds.2004-2479 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Fowler LA, Grammer AC, Staiano AE, et al. Harnessing technological solutions for childhood obesity prevention and treatment: a systematic review and meta-analysis of current applications. Int J Obes (Lond). 2021;45(5):957-981. doi: 10.1038/s41366-021-00765-x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Madsen KA, Thompson HR, Linchey J, et al. Effect of school-based body mass index reporting in California public schools: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA Pediatr. 2021;175(3):251-259. doi: 10.1001/jamapediatrics.2020.4768 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Chiolero A, Maximova K, Paradis G. Changes in BMI: an important metric for obesity prevention. Pediatrics. 2008;122(3):683-684. doi: 10.1542/peds.2008-1120 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Rose G, Day S. The population mean predicts the number of deviant individuals. BMJ. 1990;301(6759):1031-1034. doi: 10.1136/bmj.301.6759.1031 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Kolsgaard ML, Joner G, Brunborg C, Anderssen SA, Tonstad S, Andersen LF. Reduction in BMI z-score and improvement in cardiometabolic risk factors in obese children and adolescents: the Oslo Adiposity Intervention Study—a hospital/public health nurse combined treatment. BMC Pediatr. 2011;11:47. doi: 10.1186/1471-2431-11-47 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Zimmermann E, Bjerregaard LG, Gamborg M, Vaag AA, Sørensen TIA, Baker JL. Childhood body mass index and development of type 2 diabetes throughout adult life—a large-scale Danish cohort study. Obesity (Silver Spring). 2017;25(5):965-971. doi: 10.1002/oby.21820 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Bjerregaard LG, Jensen BW, Ängquist L, Osler M, Sørensen TIA, Baker JL. Change in overweight from childhood to early adulthood and risk of type 2 diabetes. N Engl J Med. 2018;378(14):1302-1312. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1713231 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Metcalf B, Henley W, Wilkin T. Effectiveness of intervention on physical activity of children: systematic review and meta-analysis of controlled trials with objectively measured outcomes (EarlyBird 54). BMJ. 2012;345:e5888. doi: 10.1136/bmj.e5888 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Bull FC, Al-Ansari SS, Biddle S, et al. World Health Organization 2020 guidelines on physical activity and sedentary behaviour. Br J Sports Med. 2020;54(24):1451-1462. doi: 10.1136/bjsports-2020-102955 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Trial Protocol

Statistical Analysis Plan

eMethods. Additional Description

eTable 1. Description of the Multifaceted Intervention Components

eTable 2. Outline of the Health Education Activities for Children

eTable 3. Measurements and Their Associated Outcome Variables

eTable 4. Comparison of Children Included in the Primary Outcome Analysis (n=1362) and Those Lost to Follow-up (n=30) by Baseline Characteristics

eTable 5. Intervention Effects on Secondary Outcomes at Middle of Intervention

eTable 6. Intervention Effects on Remission of Overweight/Obesity at Middle and End of the Intervention

eTable 7. Intervention Effects on Incidence of Overweight/Obesity at Middle and End of the Intervention

eTable 8. Outcomes of Adverse Events at the End of the Intervention

eTable 9. Implementation of the Multifaceted Intervention Components

eFigure 1. Random Allocation of Schools to the Intervention or Control Group Within 5 Districts (Strata)

eFigure 2. The Remission and Incidence of Obesity in the Intervention and Control Groups

eFigure 3. The Distribution of BMI z Score at Baseline and End of the Intervention in the Intervention (A) and Control (B) Groups

eReferences

Data Sharing Statement