Abstract

A long-standing challenge in cell biology is elucidating the spatial distribution of individual membrane-bound proteins, protein complexes and their interactions in their native environment. Here, we describe a workflow that combines on-grid immunogold labeling, followed by cryo-electron tomography (cryoET) imaging and structural analyses to identify and characterize the structure of photosystem II (PSII) complexes. Using an antibody specific to a core subunit of PSII, the D1 protein (uniquely found in the water splitting complex in all oxygenic photoautotrophs), we identified PSII complexes in biophysically active thylakoid membranes isolated from a model marine diatom Phaeodactylum tricornutum. Subsequent cryoET analyses of these protein complexes resolved two PSII structures: supercomplexes and dimeric cores. Our integrative approach establishes the structural signature of multimeric membrane protein complexes in their native environment and provides a pathway to elucidate their high-resolution structures.

Introduction

In recent decades, cryo-electron tomography (cryoET) has emerged as a cutting-edge imaging modality that enables direct three-dimensional visualization of protein structures and organelles from various organisms in their native states (Dunstone & de Marco, 2017; Hampton et al., 2017; Hu, Lara-Tejero, Kong, Galán, & Liu, 2017; Lin, Okada, Raytchev, Smith, & Nicastro, 2014; Lučić, Rigort, & Baumeister, 2013; McIntosh, Nicastro, & Mastronarde, 2005; Oikonomou & Jensen, 2017). A challenge in in-situ structure determination is identification of target proteins in the crowded cellular background, especially when structural information of the target protein is limited or unknown. Immunogold labeling coupled to conventional TEM is a well-established method to “tag” the protein of interest and elucidate its localization (Agarwal, Ortleb, Sainis, & Melzer, 2009; Flori et al., 2017; Heinz et al., 2016; Pfeiffer & Krupinska, 2005). However, conventional TEM sample preparation requires chemical fixation and dehydration of the specimen, which often introduces artifacts. Therefore, integration of immunogold labeling and cryoET of vitrified samples may be particularly advantageous for studies of protein structure and distribution in native cellular environments (McIntosh et al., 2005; Yi et al., 2015).

CryoET structural studies have greatly contributed to our understanding of oxygenic photosynthesis (Dai et al., 2018; Daum, Nicastro, Austin, McIntosh, & Kühlbrandt, 2010; Davies & Daum, 2013; Engel et al., 2015). This photobiological reaction involves the flow of electrons and protons through four thylakoid-embedded protein complexes to split water into molecular oxygen and form reductants, as well as ATP, used to fix inorganic carbon and power the cell. The protein complex responsible for this water-splitting and the subsequent source of electrons and protons is photosystem II (PSII). A highly-conserved, core protein within PSII is D1, which is especially susceptible to photodamage. Repair of D1 requires efficient repair mechanisms for robust photosynthesis. Previous studies in terrestrial plants suggest that photodamaged D1 may adopt different conformations that spatially segregate PSII complexes in thylakoid membranes prior to repair (Chow & Aro, 2005; Yokthongwattana, Savchenko, Polle, & Melis, 2005). However, it is unclear if spatial segregation of D1 occurs in marine diatoms, which possess thylakoid ultrastructure that markedly differs from that of green algae or terrestrial plants (Bína, Herbstová, Gardian, Vácha, & Litvín, 2016; Falkowski & Raven, 2013).

Here, we describe a streamlined workflow for on-grid immunogold labeling with cryoET imaging of PSII embedded in thylakoid membranes of marine diatom Phaeodactylum tricornutum. The structures of PSII complexes from diatoms were resolved by subtomogram averaging and single particle analysis (Levitan et al., 2019; Pi et al., 2019). These structures provide useful references to demonstrate the applicability and validity of this experimental protocol. This protocol establishes a framework for identification and preliminary structural determination of protein complexes that are previously uncharacterized. The structural signature established following this protocol can be used as a model for future high-resolution structural studies. Furthermore, we also provide strategies to improve sample preservation and antibody labeling on EM grids.

Materials and Methods

1. Sample Preparation

1.1. Thylakoid Membrane Isolation

We grew 10 L batches of P. tricornutum Bohlin (CCAP 1055/1), strain Pt1 8.6, in artificial seawater enriched in nutrients according to the F/2 medium in continuous white LED light (100–120 μmol photon m−2 s−1) at 18 °C (Guillard, 1975; Guillard & Ryther, 1962). Cells were harvested in log phase growth by continuous centrifugation (10,000 g, 4 °C). Thylakoid membranes were isolated as described with slight modification (Kansy, Gurowietz, Wilhelm, & Goss, 2017; Levitan et al., 2019). The pellet was resuspended in 10 mL of Breaking Buffer A [2 mM Na2EDTA,1 mM MgCl2·6H2O, 1 mM MnCl3·4H2O, 50 mM Hepes (adjusted to pH 7.5), and 0.66 M sorbitol in a 50 mL Falcon tube (Corning). All steps after this were performed in the dark. The cells were lysed at 6,000 psi using a French Press (SIM Aminco) pre-chilled at 4 °C. The lysate was then gently loaded onto a continuous sorbitol gradient (2 to 3.3 M) in Breaking Buffer A without sorbitol added, followed by centrifugation in a DuPont HB-6 swing bucket rotor (16,000 g, 30 min, 4 °C). Fraction 1 and the volume above (Fig. 2A), consisting of thylakoid membranes (Fig. 2B), were collected with a transfer pipet and washed with 1:12 (v:v) Washing Buffer B [6 mM Na2EDTA, 5 mM MgCl2·6H2O, 1 mM MnCl3·4H2O, 50 mM Hepes (adjusted to pH 7.5), 10 mM KCl]. The thylakoid membranes were collected and set on ice. The supernatant was also collected, followed by a 1:2 (v:v) dilution with the washing buffer and centrifugation (10,000 g, 10 min, 4 °C) to pellet the remaining membranes. This step was repeated twice. Thylakoid membranes were resuspended in 30 μL of 1X phosphate-buffered saline (PBS, pH 7.4; Sigma) at a chlorophyll a (Chl a) concentration of ~0.67 mg/mL. Chl a quantification was performed according to Jeffrey & Humphrey (1975).

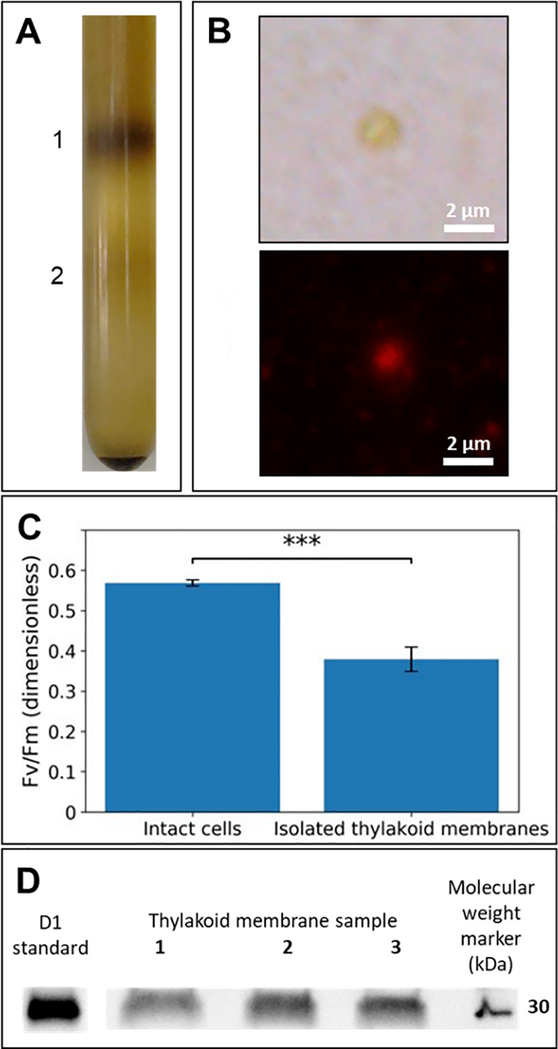

Figure 2. Isolated thylakoid membranes contain functional PSII.

(A) Thylakoid membrane fraction in continuous sorbitol gradient. Thylakoid membranes were isolated and purified from fraction 1. (B) Brightfield (top) and chlorophyll autofluorescence (bottom) images of isolated thylakoid. Both images are from the same section of microscope slide and taken at 600× magnification. (C) Quantum yield of PSII photochemistry (Fv/Fm). Fv/Fm was estimated by FRR Fluorometry (n = 3). Triple asterisks (***) denote a significance level of P < 0.001 at α = 0.05 in Student’s t-test. (D) A western blot of thylakoid membranes isolated from three independent isolations.

1.2. Fast Repetition Rate (FRR) Fluorometry

To assess the biophysical activity of PSII in isolated thylakoid membranes, we measured the quantum yield of PSII photochemistry (Fv/Fm) using a miniaturized FRR fluorometer (Gorbunov & Falkowski, 2020).

1.3. Epifluorescence Microscopy

Isolated thylakoid membranes were visually verified under the brightfield and chlorophyll fluorescence settings at 600x using an Olympus BX53 Epifluorescence microscope with a DP80 Digital camera.

1.4. Protein Analyses

To quantify protein complexes, thylakoid membranes were resuspended in 1X denaturing lithium dodecyl sulfate (LDS) extraction buffer, containing a 1/200 protease inhibitor mixture (Sigma–Aldrich), and lysed in matrix Y with a FastPrep-24 5G Homogenizer (MP Biomedicals). The supernatant was collected after centrifugation (14,000 g, 10 min, 4 °C). The extracted proteins were quantified with DC Protein Assay kit (Bio-Rad) and SpectraMax M3 microplate reader (Molecular Devices) at 750 nm. Bovine serum albumin (BSA; Thermo Fisher Scientific) was used as the reference standard. Gel electrophoresis was performed in precast 4–20% Tris-glycine extended (TGX) gels (Bio-Rad) with 1 μg of extracted protein, followed by transferring the separated proteins to PVDF membranes using a Trans-Blot Turbo Dry Transfer System (Bio-Rad). The presence of the PSII core subunit D1 protein was verified by western blot (Fig. 2D) using a rabbit poly-clonal antibody anti-D1/PsbA at 1:10,000 dilution (Agrisera). An HRP-conjugated chicken anti-rabbit IgG (1:20,000 dilution; Agrisera) was used as the secondary antibody. A D1/PsbA standard (Agrisera) was used as positive control. Amersham ECL Select Detection Reagent (GE Healthcare) was used to develop the PVDF membranes. Images were taken with ChemiDoc MP Imaging System (Bio-Rad). Thylakoid membranes from three independent isolations were used for photochemical and biochemical analyses.

2. Preparation of EM Grids for On-grid Immunogold Labeling

2.1. Cleaning and Glow Discharge

A batch of 200 mesh continuous carbon-coated copper grids (EMS) were washed overnight with acetone to remove residual organics and debris (Passmore & Russo, 2016; Wensel & Gilliam, 2015). Acetone-treated EM grids were then washed with PBS for 10 s and left to air-dry on a clean filter paper with the carbon side up (Fig. 1 inset A). Using a PELCO easiGlow system, the cleaned and dried EM grids were glow-discharged for 30 s to render the carbon film surface more hydrophilic for improved sample adhesion (Cheung et al., 2013; Dubochet, Groom, & Mueller-Neuteboom, 1982; Grassucci, Taylor, & Frank, 2007).

Figure 1. An integrative experimental workflow for on-grid immunogold labeling of thylakoid membrane-embedded PSII and cryoET structural studies.

(1) Isolation of thylakoid membranes from P. tricornutum followed by physiological and protein analyses. (2) Preparation of EM grid for on-grid immunogold labeling. Inset A compares the front side with continuous carbon support film (left) and the back side (right). (3) On-grid immunogold labeling. Inset B shows the setup of MatTek dishes with EM grids for on-grid immunogold labeling. (4) CryoET data acquisition and structural analyses.

2.2. Coating with Poly-L-Lysine

Following glow-discharge, groups of three EM grids were placed on the glass bottom of microwell dishes (MatTek) with no overlap (Fig. 1 inset B). These microwell dishes were arranged in a 150mm x 15mm petri dish (CELLTREAT) and clustered around a central microwell dish containing distilled water to prevent the grids from drying. The grids were coated with 150 μL of 0.01% (w/v) poly-L-lysine solution (Sigma-Aldrich) for 2 h. The poly-L-Lysine solution was removed by pipetting, followed by the addition of 150 μL of PBS. The addition and removal of PBS by pipetting (washing step) was done three times.

3. On-grid Immunogold Labeling of PSII

3.1. Thylakoid Membrane Sample Plating

On-grid immunogold labeling was performed in the dark to avoid photooxidative damage to the isolated thylakoid membranes. 4 μL of isolated thylakoid membranes (ca. 0.67 mg/mL) was applied onto the poly-L-lysine-coated EM grids and incubated at room temperature for 1 h in the dark.

3.2. Blocking

Prior to blocking, 150 μL of PBS was added directly into the microwells to wash off excess thylakoid membranes. This washing step was repeated three times until the washing solution became clear. Next, 150 μL of 0.4% BSA (w/v; AMRESCO), filtered with a 0.22 μm sterile syringe filter (VWR), was applied to the EM grids to prevent nonspecific binding of the antibodies. EM grids were incubated in the blocking buffer at room temperature for 30 min. The blocking reagent was removed by pipetting, followed by five washes with PBS.

3.3. Primary and Secondary Antibody Incubation

EM grids were incubated in 150 μL of freshly diluted (1:25 in PBS) rabbit anti-D1/PsbA primary antibody (Agrisera). As a control for secondary antibody specificity, a set of grids were incubated in 150 μL of PBS in the absence of anti-D1, but otherwise processed identically as the D1-labeled thylakoid membranes. Following an hour of incubation at room temperature, the primary antibody solution was removed, and the grids were washed five times with PBS. For all grids, 8 μL of secondary antibody (goat-anti-rabbit IgG conjugated with 6 nm gold particle conjugates; diluted with PBS at 1:25; EMS) was added directly onto each individual grid and incubated at room temperature for 1 h. The secondary antibody solution was removed, followed by five PBS washes. The grids were incubated in PBS until vitrification. We prepared freshly isolated thylakoid membranes and immediately vitrified on EM grids as a control for the immunogold labeling experiment (see section 3.4).

3.4. Vitrification of EM grids

EM grids were vitrified by plunge-freezing using a Leica EM GP plunger (Leica Microsystems). To avoid excessive drying during blotting, 2.5 μL of PBS was applied to the grids before plunging. The grids were front-blotted in a humidity (95%) and temperature (20 °C) controlled chamber. The plunger was set to a blot force of 225 with a 3 s blot time.

For the control, freshly prepared thylakoid membranes were mixed with 10 nm gold fiducials (EMS) and plunge frozen on glow-charged R 2/1 copper Quantifoil grids (EMS) without undergoing immunogold labeling. Plunge-frozen grids were stored in a liquid nitrogen dewar until imaging.

4. Cryo-electron Tomography

4.1. Image Acquisition and 3D Tomogram Reconstruction

2D projection images and tilt series of immunogold-labeled thylakoid membranes were collected on a Talos Arctica cryo-electron microscope (Thermo Fisher Scientific) equipped with a post-column BioQuantum energy filter (with the slit set to 20 eV) and a K2 direct electron detector (Gatan). Data collection was done using SerialEM software (Mastronarde, 2005). Typically, a tilt series ranges from −60° to 60° at 3° step increments. Imaging settings used were: 49,000× microscope magnification, spot size 8, 100 μm condenser aperture, 100 μm objective aperture, and −4.5 μm nominal defocus. The image pixel size was 2.72 Å/pixel and the accumulated exposure was approximately 80–100 e−/Å2. 2D projection images were collected at the same magnification and imaging configuration at 5–6 e−/Å2. A total of 26 2D projections and 6 tilt series was collected on the control immunogold-labeled thylakoid membranes (i.e., incubated in only secondary antibody) and 43 projection images and 6 tilt series for D1-labeled thylakoid membranes.

Tilt series alignment and reconstruction were performed with IMOD (Kremer, Mastronarde, & McIntosh, 1996), using the 10 nm gold fiducials or the 6 nm gold particles conjugated to the secondary antibody as markers.

4.2. Identification of PSII Structures

Extraction of PSII holocomplex subtomograms was performed on tomograms of D1-labeled thylakoid membranes. We identified protein densities as PSII holocomplexes if they are in membrane regions labeled with gold particles, 15–20 nm in size, exhibit predominant C2 symmetry and are consistent with known morphological features of PSII complexes (Levitan et al., 2019; Pi et al., 2019). These PSII holocomplex densities were included in subsequent 2D structural analysis (see section 4.5).

Since PSII dimeric cores arrange into semicrystalline arrays, patches of arrays in the labeled membranes were extracted using a box size of 1923 and binned by 2 to reduce computational time. The extracted patches using this box size include about 20 dimeric cores and were used for both subtomogram averaging and 2D distribution analyses.

4.3. Antibody Specificity Analysis

To evaluate antibody specificity, we compared the density of gold particles attached to D1-labeled thylakoid membranes to control (thylakoid membranes without primary antibody against D1). The density of gold particles is defined as gold count normalized to membrane area. We did two comparisons: 1) gold density from D1-labeled thylakoid membranes vs. gold density from control thylakoid membranes (without primary antibody) (Fig. 5C); 2) gold density on D1-labeled thylakoid membranes vs. gold density in the background of D1-labeled thylakoid membranes (Fig. 5D). The “background area” refers to a region of the micrograph, taken at 49,000× magnification, that is not occupied by thylakoid membranes (i.e., background area = total area of the image – area of thylakoid membranes).

Figure 5. Quantification of antibody labeling specificity.

(A) An EM image of D1-labeled thylakoid membranes. (B) An EM image of control thylakoid membranes that were incubated in PBS in lieu of anti-D1 primary antibody, followed by incubation with secondary antibody. (C) Gold particle density comparison between D1-labeled thylakoid membranes and control thylakoid membranes. (D) Comparison of density of gold particles attached to D1-labeled thylakoid membranes and in the background. Triple asterisks (***) denote a significance level of P < 0.001 at α = 0.05 in Mann-Whitney U test.

Quantification of gold particles was performed on 2D images of D1-labeled (n = 43) thylakoid membranes and control (n = 26). To detect the 6 nm-sized gold particles in the micrographs, we used imodfindbeads in the IMOD program, which automatically annotates gold particles by cross-correlation. We used a model bead of 6 nm as an initial reference to correlate with the micrograph. The reference is updated with the average of the most strongly-correlating subset to iteratively refine selected gold particles. Positions of these selected densities are saved as a model in IMOD and visualized in 3dmod. False positives, such as ice contaminations and cellular debris, were removed through manual inspection and omitted from the analysis. To quantify gold particles, an area model encompassing thylakoid membrane regions was created using contour line tracing. After drawing boundaries around thylakoid membrane regions, the area of thylakoid membranes enclosed by the closed contour was determined by values obtained from the IMOD contour information. We also performed manual gold particle annotation to verify the cross-correlation based particle counting. Both approaches generated similar quantification results.

To perform statistical analysis of antibody specificity, the density of gold particles in images from control and D1 treatments was plotted and inspected visually to check for normality, followed by Shapiro-Wilk test (scipy.stats.shapiro; SciPy v1.4.1). If normality was confirmed, we proceeded with the Levene test for equal variance (scipy.stats.levene; SciPy v1.4.1). If normality and equal variance were confirmed, independent Student’s t-test was conducted using a Python SciPy Statistical Functions package (scipy.stats.ttest_ind; SciPy v1.4.1) Otherwise, the nonparametric Mann Whitney U test was used (scipy.stats.mannwhitneyu; SciPy v1.4.1) (Virtanen et al., 2020).

4.4. Antibody Sensitivity Analysis

To evaluate antibody sensitivity, we examined the number of immunogold-labeled PSII holocomplexes and PSII cores relative to the total number of recognizable complexes. We manually counted total PSII structures based on their C2 symmetry and structural features by referring to published structures of PSII holocomplexes and arrays (Levitan et al., 2019; Pi et al., 2019). The number of D1-labeled PSII is quantified as the number of gold particles that were associated with the target protein density.

4.5. PSII Structural and Distribution Analyses

Structural analyses were done using the latest EMAN2 tomography workflow (Chen et al., 2019). Contrast transfer function (CTF) was determined for each image in the tilt series (Supplementary Fig. 1). CTF-correction was performed for each particle in sub-tilt images, based on the defocus of the micrograph, tilt geometry and coordinates of the particle. To generate a de novo initial model of the PSII cores, we selected and extracted a subset of 50 subtomograms using a box size of 1923 and binned by 2. Five iterations of the EMAN2 initial model generation routine were performed. The initial model was then used for subsequent subtomogram refinement on a total of 263 particles. A 3D subtomogram average of the PSII array was obtained following the iterative refinement schema until no improvement in structure or resolution can be detected. The resolution of the 3D subtomogram average was 37 Å as determined by Fourier Shell Correlation (FSC) of two independent density maps from two halves of the entire dataset (Supplementary Fig. 2).

For PSII holocomplexes, we extracted 91 PSII holocomplex particles (box size 1923) from D1-labeled thylakoid membrane tomograms. PSII holocomplexes are usually located within thicker, stacked thylakoid membrane regions. Due to the low contrast of the PSII holocomplex subtomograms and the small dataset, only 2D averaging was performed.

For 2D analysis of the single unit in the PSII array, extracted subvolumes were first subjected to a 30 Å low pass filter to remove high frequency noise. The center slab containing the PSII arrays was then used to generate a 2D projection for each subtomogram. The iterative 2D class averaging process was used to generate the average 2D structure. Unit cell annotations for PSII arrays and mapping of the 3D subtomogram average of PSII cores to the original coordinates in the tomogram were performed in EMAN2. UCSF Chimera was used for 3D visualization of the annotated tomogram (Pettersen et al., 2004).

Results and Discussion

Isolated Thylakoid Membranes Retained PSII Activity

To isolate relatively intact and physiologically active thylakoid membranes, we lysed diatom cells and isolated thylakoid membranes in a continuous sorbitol gradient. Visual inspection of the fraction revealed golden-brown thylakoid membranes of ca. 2 μm in diameter which exhibited autofluorescence (Fig. 2A, B). We estimated the PSII quantum yield (Fv/Fm) of these isolated membranes to determine their photobiochemical activity. The isolated thylakoids retained ca. 67% of the PSII photochemistry potential (Fv/Fm of 0.38±0.03) relative to intact diatom cells (Fv/Fm of 0.57±0.01) (Fig. 2C), indicating that the thylakoid membrane samples retained a significant level of physiological activity. The presence of PSII in isolated thylakoid membranes from three independent experiments was confirmed by western blot analysis (Fig. 2D). Taken together, these data indicate that the membrane isolation protocol consistently yielded thylakoid membranes containing highly active PSII reaction centers.

The Structural Integrity of Thylakoid Membranes Was Preserved after Immunogold Labeling

To evaluate the preservation of native thylakoid membrane morphology and associated proteins after on-grid immunogold labeling, we examined 2D projection images and tomogoram reconstructions of D1-labeled thylakoid membranes and compared them with thylakoid membranes that were vitrified immediately after membrane isolation without undergoing immunogold labeling. At 3000× magnification, thylakoid membranes were identified as micron-sized gray granules in both conditions (Fig. 3A, C). The concentration of thylakoid membranes appears higher on immunogold-labeled grids, which is most likely attributed to improved sample adhesion due to poly-L-lysine treatment of immunogold-labeled grids prior to sample application (Fig. 3A, C). Although stacking is less apparent in immunogold-labeled membranes, the overall thylakoid membrane structure and membrane proteins were preserved after the immunogold labeling process (Fig. 3B, D).

Figure 3. Thylakoid membrane integrity was retained after the immunogold labeling experiment.

(A-B) EM images of D1-labeled thylakoid membranes on continuous carbon film EM grids at 3000× (A) and 49,000× (B) magnifications. Electron-dense particles in (B) correspond to 6 nm gold particles conjugated to the secondary antibody. (C-D) EM images of thylakoid membranes on Quantifoil grids without immunogold labeling treatment at 3000× (C) and 49,000× (D) magnifications. Electron-dense particles in (D) correspond to 10 nm gold fiducials.

Antibody Labeling Specificity

Previous studies revealed that PSII in thylakoid membranes of cyanobacteria and terrestrial plants exhibit a conserved core complex with heterogeneous composition of extrinsic subunits or antenna proteins (Hellmich et al., 2014; Tietz et al., 2015). To detect PSII structures of various compositions, we used a polyclonal primary antibody specific to a PSII core subunit, D1 (also known as PsbA). This protein has five transmembrane helices and contains two electron donors and acceptors crucial to the function of PSII. On the stromal side of D1, there is a short N-terminal domain containing Thr 220-Asn 267, which consists of two exposed short helices and loops (Fig. 4; black circle). On the lumenal side, D1 interacts with extrinsic PsbU, PsbV, PsbQ’ and PsbO subunits, forming an opening between PsbV and PsbO subunits that may be accessible to antibody binding (Fig. 4; black circle; yellow region). Given that the antibody used is raised against the C-terminal fragment of the D1 subunit, it can putatively access the protein from both the stromal and/or the lumenal side of the membrane (Flori et al., 2017). This is particularly advantageous because thylakoid membranes applied to EM grids exist in both orientations.

Figure 4. Domain analysis of D1 in the PSII core complex.

D1/PsbA (PsbA; PDB ID: 6JLU) C-terminal and N-terminal domains potentially accessible to antibody labeling are indicated in black circles and a grey circle, respectively. In the top view, the yellow region corresponds to an opening formed by extrinsic units from the lumenal side. D1/PsbA (red), PsbO (gray), PsbQ’ (blue), PsbU (magenta), and PsbV (cyan).

To assess the labeling specificity of the immunogold labeling experiment, we compared the density of gold particles in micrographs of D1-labeled membranes and those without incubation in the primary antibody against D1. We observed a marked difference in the total number of gold particles in 2D projection images of thylakoid membranes labeled with and without anti-D1 (Fig. 5A, B; Movie S1–S2). Labeling thylakoid membranes with anti-D1 resulted in a median gold density of 3.20×10−4 count/nm2 whereas control thylakoid membranes yielded 0.01×10−4 count/nm2 (i.e., a 560-fold difference in gold density; p < 0.001 at α = 0.05 in Mann-Whitney U test; Supplementary Table 1). Overall, the gold particle density in the experimental and immunogold labeling control (without primary antibody) is significantly different (Fig. 5C). The gold density attached to D1-labeled thylakoid membranes (normalized to the area of the membrane; 3.20×10−4 count/nm2) is 2-fold higher than the density observed in the background (normalized to the area of the background; 1.60×10−4 count/nm2) (Fig. 5D; Supplementary Table 2). These findings strongly suggest that the antibody labeling is specific to the D1 protein.

Structural Analysis of D1-labeled PSII

Antibody labeling detected two PSII structures on thylakoid membranes: one as scattered complexes and the other as dimeric cores present in semicrystalline arrays. Subtomogram analysis and 2D averaging of the former structure revealed protein complexes displaying C2 symmetry with the overall size and shape corresponding to the features of diatom PSII holocomplexes (EMD-0539; Levitan et al., 2019) (Fig. 6A, C, D). Due to lower relative abundance of this PSII subpopulation in D1-labeled membranes, we were unable to obtain a reasonable 3D subtomogram average of the PSII holocomplexes.

Figure 6. Structural and distribution analysis of PSII structures in D1-labeled thylakoid membranes.

(A) A slice of a tomogram of immunogold-labeled thylakoid membranes. Green arrows: PSII holocomplexes. (B) A slice of a tomogram of immunogold-labeled thylakoid membranes showing semicrystalline arrays of PSII cores. Box: cluster of PSII array. 3D annotated view of the boxed area is shown in (I). (C) 2D average of PSII holocomplexes from D1-labeled thylakoid membranes. (D) 2D projection of subtomogram average of published PSII holocomplexes (EMD-0539; Levitan et al., 2019). (E) 2D average of immunogold-labeled semicrystalline arrays. (F) Diffraction of the 2D average of PSII cores in arrays. (G) 2D average of published PSII arrays (EMD-0540; Levitan et al., 2019). (H) 3D subtomogram average of PSII cores in arrays. (I) Top view of volume rendering of PSII cores (blue) and gold particles conjugated to secondary antibodies (magenta) mapped to the thylakoid membrane tomogram at their original coordinates. (J) Zoomed-in, tilted view of a D1-labeled PSII array, boxed in (I), annotated with PSII cores (blue) and gold particles conjugated to secondary antibodies (magenta).

The other PSII structure detected forms highly-organized, semicrystalline arrays with each unit measuring 17.8 nm × 10.8 nm (Fig. 6B, E). Diffraction of the PSII array showed regularly-spaced reflections characteristic of a crystal-like arrangement (Fig. 6F). Using particles extracted from immunogold-labeled 2D arrays, we obtained a 37 Å map of the PSII cores by subtomogram averaging (Supplementary Fig. 2). The resolution of our current subtomogram average is limited by overall low contrast due to the carbon support film, the low number of particles in the tomogram and preferred orientation of particles on membranes. However, from the 3D map, it is clear that the PSII structure is dimeric. The overall domain organization of the single unit agrees well with the PSII core complex composed of the four subunits (D1/PsbA, PsbB, PsbC and PsbD, EMD-0540; Levitan et al., 2019; Pi et al., 2019) (Fig. 6E–H). PSII cores in the arrays were mapped back to a D1-labeled thylakoid membrane tomogram at their original orientation (Fig. 6I, J). This PSII array is about 400 nm × 200 nm and composed of approximately 250 PSII cores. Distribution of PSII cores in the arrays confirmed the semicrystalline arrangement observed in the 2D analysis (Fig. 6E).

Our data demonstrate that immunogold labeling reliably detected two PSII subpopulations with different compositions and distribution. These two different structures may represent distinct functional states, and the relative abundance may vary depending on cellular physiological states or preparation protocols (Levitan et al., 2019). In tomograms of D1-labeled thylakoid membranes, the single unit in semicrystalline arrays (n = 263) were more abundant than the holocomplexes (n = 91). Notably, clustering of PSII holocomplexes, a characteristic feature of biochemically active holocomplexes in P. tricornutum, was less frequently observed on immunogold-labeled membranes. The duration of the immunogold labeling may have led to some protein degradation, and thus affecting PSII structural integrity. Reducing time required in the workflow is a key step towards correlating PSII structures with their functional activities.

Antibody Labeling Sensitivity Analysis

To quantify the antibody labeling sensitivity, we calculated the ratio between the number of gold particles that are attached to each PSII subpopulation vs. the total detectable PSII structures from D1-labeled thylakoid membrane tomograms. The overall antibody labeling sensitivity is approximately 22% for PSII holocomplexes and 20% for PSII cores in semicrystalline arrays. This relative low antibody sensitivity may be attributed to the nature of D1 as a transmembrane protein. The D1 antibody used in our study has been shown to be capable of detecting a 24 kDa or a 10 kDa C-terminal fragments of D1 subunit. The C-terminal region primarily consists of transmembrane helices except two domains that are potentially exposed on the outside of the membrane and accessible to antibody labeling (Fig. 4; black circle). In addition, the presence of extrinsic units on the lumenal side may limit the exposure of D1 epitopes and contribute to the low labeling sensitivity.

Optimization of On-grid Immunogold Labeling for CryoET

Efficient immunogold labeling requires access to antigen epitopes in the native 3D structure of the target protein. This requirement posed a major limitation on antibody selection, especially for membrane proteins. To improve PSII labeling, future studies should target PSII core complex subunits with larger exposed domains, including PsbB and PsbC.

Several measures have been taken to further optimize the protocol, namely selection of grid type and sample adhesion to improve labeling efficiency and image quality for subsequent structural analyses. We performed immunogold labeling on copper grids coated with continuous carbon of two different thicknesses: standard (5–6 nm) and ultra-thin (3–4 nm). Due to extensive grid manipulation required throughout the experimental procedure, the ultra-thin grids were mostly broken and unsuitable for meaningful data collection. The standard thickness carbon film provided better support for immunogold labeling and sufficient contrast for cryoET imaging. Additionally, we coated EM grids used for immunogold labeling experiments with poly-L-lysine, which greatly improved sample adhesion and resulted in retention of thylakoid membranes even after extensive washing steps (Barth, 1985). From coating of thylakoid membranes to cryo-preservation of immunogold-labeled membranes on grids, the complete workflow required 11 hours, which may potentially lead to membrane deformation or some level of protein degradation. Therefore, we considered chemically fixing (a 2% formaldehyde-0.25% glutaraldehyde combination fixative) thylakoid membranes prior to immunogold labeling. However, this led to alterations in thylakoid morphology and apparently reduced abundance of photosynthetic protein complexes (Supplementary Fig. 3). Light chemical fixation may compromise the structural integrity of cellular structures (Li et al., 2017).

Conclusion

In summary, we described a workflow that streamlines on-grid identification and structural study by cryoET and subtomogram averaging and analysis. We used PSII from P. tricornutum as the test target protein and demonstrated that this integrated workflow consistently revealed the distribution pattern and overall structure of two PSII subpopulations in thylakoid membranes. By subtomogram averaging of D1-labeled PSII arrays, we obtained a 3D map of the PSII core that agrees well with published structures. Application of this protocol enables identification and preliminary structural determination of membrane proteins, especially those with limited structural information. Structural insights on the protein of interest resolved by this workflow will serve as a valuable model for future higher resolution structural studies.

Supplementary Material

Highlights.

Immunogold labeling coupled with cryoET identifies target proteins for structural analyses

Preliminary structural insights provide a pathway for high-resolution structural studies

Strategies for improved labeling efficiency and preservation of biological samples

Acknowledgements

Tilt series of thylakoid membranes were collected at Rutgers CryoEM & Nanoimaging Facility. We thank Jason T. Kaelber and Emre Firlar for technical support in data collection and Muyuan Chen for assistance with EMAN2 data processing and analysis. Reference thylakoid membrane data collected from Purdue University was supported by the National Institutes of Health Midwest Consortium for High Resolution Cryo-electron Microscopy (U24 GM116789–01A1). This work was partially supported by grants from the Rutgers Busch Biomedical Grant to W.D. and Bennett L. Smith Endowment to P.G.F.

Footnotes

Declaration of interests

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Data availability statement

The subtomogram average of PSII semicrystalline array has been deposited in the EMDataBank under accession code EMD-23791.

References

- Agarwal R, Ortleb S, Sainis JK, & Melzer M (2009). Immunoelectron microscopy for locating Calvin cycle enzymes in the thylakoids of Synechocystis 6803. Molecular Plant, 2(1), 32–42. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barth OM (1985). The use of polylysine during negative staining of viral suspensions. Journal of Virological Methods, 11(1), 23–27. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bína D, Herbstová M, Gardian Z, Vácha F, & Litvín R (2016). Novel structural aspect of the diatom thylakoid membrane: Lateral segregation of photosystem I under red-enhanced illumination. Scientific Reports, 6(February), 1–10. 10.1038/srep25583 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen M, Bell JM, Shi X, Sun SY, Wang Z, & Ludtke SJ (2019). A complete data processing workflow for cryo-ET and subtomogram averaging. Nature Methods, 16(11), 1161–1168. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cheung M, Kajimura N, Makino F, Ashihara M, Miyata T, Kato T, … Blocker AJ (2013). A method to achieve homogeneous dispersion of large transmembrane complexes within the holes of carbon films for electron cryomicroscopy. Journal of Structural Biology, 182(1), 51–56. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chow WS, & Aro E-M (2005). Photoinactivation and mechanisms of recovery. In Photosystem II (pp. 627–648). Springer. [Google Scholar]

- Dai W, Chen M, Myers C, Ludtke SJ, Pettitt BM, King JA, … Chiu W (2018). Visualizing individual RuBisCO and its assembly into carboxysomes in marine cyanobacteria by cryo-electron tomography. Journal of Molecular Biology, 430(21), 4156–4167. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Daum B, Nicastro D, Austin J, McIntosh JR, & Kühlbrandt W (2010). Arrangement of photosystem II and ATP synthase in chloroplast membranes of spinach and pea. The Plant Cell, 22(4), 1299–1312. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davies KM, & Daum B (2013). Role of cryo-ET in membrane bioenergetics research. Portland Press Ltd. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dubochet J, Groom M, & Mueller-Neuteboom S (1982). The mounting of macromolecules for electron microscopy with particular reference to surface phenomena and the treatment of support films by glow discharge. Adv. Opt. Electron Microsc, 8, 107–135. [Google Scholar]

- Dunstone MA, & de Marco A (2017). Cryo-electron tomography: an ideal method to study membrane-associated proteins. Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences, 372(1726), 20160210. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Engel BD, Schaffer M, Cuellar LK, Villa E, Plitzko JM, & Baumeister W (2015). Native architecture of the chlamydomonas chloroplast revealed by in situ cryo-electron tomography. ELife, 2015(4), 1–29. 10.7554/eLife.04889 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Falkowski PG, & Raven JA (2013). An introduction to photosynthesis in aquatic systems. In Falkowski PG & Raven JA (Eds.), Aquatic photosynthesis (pp. 1–43). Princeton University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Flori S, Jouneau PH, Bailleul B, Gallet B, Estrozi LF, Moriscot C, … Finazzi G (2017). Plastid thylakoid architecture optimizes photosynthesis in diatoms. Nature Communications, 8(May). 10.1038/ncomms15885 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gorbunov MY, & Falkowski PG (2020). Using chlorophyll fluorescence kinetics to determine photosynthesis in aquatic ecosystems. Limnology and Oceanography. 10.1002/lno.11581 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Grassucci RA, Taylor DJ, & Frank J (2007). Preparation of macromolecular complexes for cryo-electron microscopy. Nature Protocols, 2(12), 3239. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hampton CM, Strauss JD, Ke Z, Dillard RS, Hammonds JE, Alonas E, … others. (2017). Correlated fluorescence microscopy and cryo-electron tomography of virus-infected or transfected mammalian cells. Nature Protocols, 12(1), 150. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heinz S, Rast A, Shao L, Gutu A, Gügel IL, Heyno E, … others. (2016). Thylakoid membrane architecture in synechocystis depends on CurT, a homolog of the granal CURVATURE THYLAKOID1 proteins. The Plant Cell, 28(9), 2238–2260. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hellmich J, Bommer M, Burkhardt A, Ibrahim M, Kern J, Meents A, … Zouni A (2014). Native-like photosystem II superstructure at 2.44 Åresolution through detergent extraction from the protein crystal. Structure, 22(11), 1607–1615. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hu B, Lara-Tejero M, Kong Q, Galán JE, & Liu J (2017). In situ molecular architecture of the Salmonella type III secretion machine. Cell, 168(6), 1065–1074. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jeffrey SW, & Humphrey GF (1975). New spectrophotometric equations for determining chlorophylls a, b, c1 and c2 in higher plants, algae and natural phytoplankton. Biochemie Und Physiologie Der Pflanzen, 167(2), 191–194. 10.1016/S0015-3796(17)30778-3 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kansy M, Gurowietz A, Wilhelm C, & Goss R (2017). An optimized protocol for the preparation of oxygen-evolving thylakoid membranes from Cyclotella meneghiniana provides a tool for the investigation of diatom plastidic electron transport. BMC Plant Biology, 17(1), 1–14. 10.1186/s12870-017-1154-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kremer JR, Mastronarde DN, & McIntosh JR (1996). Computer visualization of three-dimensional image data using IMOD. Journal of Structural Biology, 116(1), 71–76. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Levitan O, Chen M, Kuang X, Cheong KY, Jiang J, Banal M, … Dai W (2019). Structural and functional analyses of photosystem II in the marine diatom Phaeodactylum tricornutum. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America, 116(35), 17316–17322. 10.1073/pnas.1906726116 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li Y, Almassalha LM, Chandler JE, Zhou X, Stypula-Cyrus YE, Hujsak KA, … Dravid VP (2017). The effects of chemical fixation on the cellular nanostructure. Experimental Cell Research, 358(2), 253–259. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lin J, Okada K, Raytchev M, Smith MC, & Nicastro D (2014). Structural mechanism of the dynein power stroke. Nature Cell Biology, 16(5), 479–485. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lučić V, Rigort A, & Baumeister W (2013). Cryo-electron tomography: the challenge of doing structural biology in situ. Journal of Cell Biology, 202(3), 407–419. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mastronarde DN (2005). Automated electron microscope tomography using robust prediction of specimen movements. Journal of Structural Biology, 152(1), 36–51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McIntosh R, Nicastro D, & Mastronarde D (2005). New views of cells in 3D: an introduction to electron tomography. Trends in Cell Biology, 15(1), 43–51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oikonomou CM, & Jensen GJ (2017). Cellular electron cryotomography: toward structural biology in situ. Annual Review of Biochemistry, 86, 873–896. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Passmore LA, & Russo CJ (2016). Specimen preparation for high-resolution cryo-EM. In Methods in enzymology (Vol. 579, pp. 51–86). Elsevier. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pettersen EF, Goddard TD, Huang CC, Couch GS, Greenblatt DM, Meng EC, & Ferrin TE (2004). UCSF Chimera—a visualization system for exploratory research and analysis. Journal of Computational Chemistry, 25(13), 1605–1612. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pfeiffer S, & Krupinska K (2005). New insights in thylakoid membrane organization. Plant and Cell Physiology, 46(9), 1443–1451. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pi X, Zhao S, Wang W, Liu D, Xu C, Han G, … Shen J-R (2019). The pigment-protein network of a diatom photosystem II--light-harvesting antenna supercomplex. Science, 365(6452). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tietz S, Puthiyaveetil S, Enlow HM, Yarbrough R, Wood M, Semchonok DA, … Kirchhoff H (2015). Functional implications of photosystem II crystal formation in photosynthetic membranes. Journal of Biological Chemistry, 290(22), 14091–14106. 10.1074/jbc.M114.619841 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Virtanen P, Gommers R, Oliphant TE, Haberland M, Reddy T, Cournapeau D, … van der Walt SJ (2020). SciPy 1.0: fundamental algorithms for scientific computing in Python. Nature Methods, 1–12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wensel TG, & Gilliam JC (2015). Three-dimensional architecture of murine rod cilium revealed by cryo-EM. In Rhodopsin (pp. 267–292). Springer. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yi H, Strauss JD, Ke Z, Alonas E, Dillard RS, Hampton CM, … others. (2015). Native immunogold labeling of cell surface proteins and viral glycoproteins for cryo-electron microscopy and cryo-electron tomography applications. Journal of Histochemistry & Cytochemistry, 63(10), 780–792. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yokthongwattana K, Savchenko T, Polle JEW, & Melis A (2005). Isolation and characterization of a xanthophyll-rich fraction from the thylakoid membrane of Dunaliella salina (green algae). Photochemical & Photobiological Sciences, 4(12), 1028–1034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

The subtomogram average of PSII semicrystalline array has been deposited in the EMDataBank under accession code EMD-23791.