Abstract

Background and Aims

Aquilegia produce elongated, three-dimensional petal spurs that fill with nectar to attract pollinators. Previous studies have shown that the diversity of spur length across the Aquilegia genus is a key innovation that is tightly linked with its recent and rapid diversification into new ranges, and that evolution of increased spur lengths is achieved via anisotropic cell elongation. Previous work identified a brassinosteroid response transcription factor as being enriched in the early developing spur cup. Brassinosteroids are known to be important for cell elongation, suggesting that brassinosteroid-mediated response may be an important regulator of spur elongation and potentially a driver of spur length diversity in Aquilegia. In this study, we investigated the role of brassinosteroids in the development of the Aquilegia coerulea petal spur.

Methods

We exogenously applied the biologically active brassinosteroid brassinolide to developing petal spurs to investigate spur growth under high hormone conditions. We used virus-induced gene silencing and gene expression experiments to understand the function of brassinosteroid-related transcription factors in A. coerulea petal spurs.

Key Results

We identified a total of three Aquilegia homologues of the BES1/BZR1 protein family and found that these genes are ubiquitously expressed in all floral tissues during development, yet, consistent with the previous RNAseq study, we found that two of these paralogues are enriched in early developing petals. Exogenously applied brassinosteroid increased petal spur length due to increased anisotropic cell elongation as well as cell division. We found that targeting of the AqBEH genes with virus-induced gene silencing resulted in shortened petals, a phenotype caused in part by a loss of cell anisotropy.

Conclusions

Collectively, our results support a role for brassinosteroids in anisotropic cell expansion in Aquilegia petal spurs and highlight the brassinosteroid pathway as a potential player in the diversification of petal spur length in Aquilegia.

Keywords: Aquilegia, petal spurs, BES1/BZR1, BEH, cell elongation, petal development, brassinosteroid response

INTRODUCTION

Plants generate diverse organ shapes that often lead to adaptive advantages. Understanding how plants sculpt their organs requires an understanding of how these organs are constructed at the cellular level and also the roles of molecular and hormonal control that underlie their development (reviewed in Whitewoods and Coen, 2017). Aquilegia petals offer a promising opportunity to investigate the multiple components of the development and evolution of complex organ shape. Members of the Aquilegia genus produce complex three-dimensional petals that consist of a flat, laminar blade and a hollow tube (spur) with a nectary at the distal end that fills the tube with nectar to attract pollinators (Whittall and Hodges 2007). From Asian origins, the genus has undergone a recent and rapid radiation in North America, during which the length of the petal spur has progressively increased, presumably to adapt to new pollinators with longer tongues. Investigations into Aquilegia petal morphology therefore offer an opportunity to not only understand how a plant builds a complex lateral organ at the cellular, tissue and organ levels, but also how a plant can modify itself at these levels in order to adapt to selective pressures of new habitats.

Previous studies on the Aquilegia petal spur have shown that petal growth can be broadly defined into two phases, which include an early phase of cell proliferation (Phase I) followed by a later phase of cell elongation (Phase II) (Puzey et al., 2012; Yant et al., 2015). Early in Phase I, cell division is widespread through the petal primordium, but it becomes increasingly limited to the incipient nectary zone, which establishes a cup-shaped bulge that will give rise to the spur. Cell divisions cease in a wave that appears to collapse down towards the incipient nectary and by the time the petal spur is 6–10 mm in length cell divisions have largely ceased. Phase II growth involves the switch from cell proliferation to expansion, which consists of highly anisotropic cell elongation. Puzey et al. (2012) measured petal spurs that varied at maturity from 2.4 to 16 cm in final length and found that the duration of Phase II and the degree of cell anisotropy accounted for 99 % of the variation in spur length between the species. In contrast, cell number only varied by ~30 % despite a 16-fold change in length between the shortest and longest lengths. This suggests that the major underlying mechanism driving the increase in spur length during the evolution of Aquilegia appears to be extension in cell length.

Based on this previous work, the goal of this study was to identify candidates that regulate the transition from division to elongation and promote the anisotropic cell elongation that generates long petal spurs. RNA sequencing (RNAseq) of Phase I showed that the expression of two brassinosteroid (BR) pathway genes was strongly enriched in the early developing spur. The first is a homologue of the Arabidopsis thaliana DWARF4 (DWF4), which is a cytochrome P450 important in the BR biosynthesis pathway (Azpiroz et al., 1998; Choe et al., 1998). The second, which is expressed later in development, is an apparent homologue of the two paralogous A. thaliana transcription factors BRI1-EMS-SUPRESSOR1 (BES1) and BRASSINAZOLE-RESISTANT1 (BRZ1) (Wang et al., 2002; Yin et al., 2002). Functional studies in arabidopsis and rice have demonstrated a conserved role for BR in anisotropic cell expansion, although these studies have primarily focused on seedlings and vegetative organs (Zhang et al., 2009; Tong et al., 2014; Yamagami et al., 2017), the one exception being studies of BR’s role in cell elongation in Gerbera petals (Huang et al., 2017; Lin et al., 2021). These findings make BR an interesting candidate for controlling petal spur elongation.

Brassinosteroids are plant hormones with pleiotropic effects on growth and development, ranging from cell elongation and proliferation to response to light and stress response, and to resistance to pathogens (see review by Nolan et al., 2020). Brassinosteroid loss-of-function phenotypes, including mutants in the BR biosynthesis pathway, BR perception or downstream regulation, are typically dwarf plants, with short stems and small round leaves with short petioles (Clouse et al., 1996; Li et al., 1996; Szekeres et al., 1996; Li and Chory, 1997; Wang et al., 2002; Nakaya et al., 2002; Yin et al., 2002; Gonzalez et al., 2010; Sun et al., 2010; Zhiponova et al., 2013, Chen et al., 2019). The BR signalling pathway initiates when BRs are perceived at the plasma membrane by the external domain of the leucine-rich repeat (LRR) receptor kinase BR INSENSITIVE1 (BRI1) (Clouse 1996; Li and Chory, 1997; He et al., 2000; Friedrichsen et al., 2000) and a co-receptor, BRI1-ASSOCIATED RECEPTOR KINASE1 (BAK1) (Li et al., 2002; Nam and Li, 2002; Wang et al., 2008). The activated BRI1 initiates a phosphorylation signalling cascade involving several regulatory proteins that results in the transcription factors BES1/BZR1 being activated and directly regulating the expression of a large network of target genes (He et al., 2002, 2005; Wang et al., 2002; Yin et al., 2002, 2005; Zhao et al., 2002; Guo et al., 2013; Sun et al., 2010). When BR levels are low, a GSK3 kinase, BRASSINOSTEROID INSENSITIVE2 (BIN2), acts to repress the activity of BES1/BRZ1 by phosphorylation (Kim et al., 2009; Hao et al., 2016; Zhu et al., 2017) and inhibits their DNA-binding activity and targets them for degradation (He et al., 2002; Yin et al., 2002; Vert and Chory 2006; Gampala et al., 2007; Ryu et al., 2007). The arabidopsis BES1/BZR1 protein family also includes four similar proteins, BEH1–BEH4, all of which are atypical bHLH transcription factors (Wang et al., 2002; Yin et al., 2002, 2005). Single loss-of-function mutations in BES1 have no change in phenotype compared with wildtype, but BES1 RNAi lines show a weak, semi-dwarf response (Yin et al., 2005). A hextuple mutant deficient in all six genes in the family has the typical dwarf phenotype of the BR biosynthesis or perception mutants (Chen et al., 2019).

Given the importance of localized cell elongation in generating petal spur length in Aquilegia, we investigated the role of BRs in the development of the Aquilegia coerulea petal spur. We used hormone applications in combination with gene expression and functional studies to provide evidence that BR plays a critical role in promoting spur elongation. Taken together, our results highlight the BR pathway as a potential contributor to the morphological diversity of spur length associated with pollinator shifts in Aquilegia. This work provides a better understanding of the development and evolution of Aquilegia spurs, as well as being the first functional BR study outside of the model eudicots and grasses.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Phylogenetic analysis

BZR1/BES1-related genes in the Aquilegia coerulea genome were determined by BLAST searches in Phytozome 12 (http://phytozome.jgi.doe.gov) using the N-terminal domain of the BR-responsive transcription factors BRASSINAZOLE-RESISTANT 1 (BZR1) and BRI1-EMS-SUPPRESSOR 1 (BES1). Homologues from 92 species were aligned using the MUSCLE (multiple sequence comparison by log-expectation) algorithm in Geneious (v9.1.8, http://www.geneious.com) then manually adjusted by hand. Several truncated sequences that only contained the N-terminal domain, as well as sequences whose homology were not confidently predicted from the alignment, were removed. The phylogenetic analysis was run using IQTREE (Trifinopoulos et al., 2016, http://iqtree.cibiv.univie.ac.at) using the default best-fit substitution model and maximum likelihood analysis from 1000 bootstrap replicates. The results were visualized with FigTree (http://tree.bio.ed.ac.uk/software/figtree/) and edited with Adobe Photoshop 2020.

Hormone applications

The active BR hormone brassinolide (BL) (ChemiClones, Waterloo, Ontario, Canada) was applied to the outer surface of spurs close to the nectary tip at 0.5, 1, 3 and 5 μm concentrations. The hormone was dissolved with ethanol for active treatments and ethanol alone was used for mock treatments. The ethanol or ethanol + hormone was mixed with liquid lanolin, cooled and applied to the spur using a glass rod. Three of five petals were treated per flower, with a total of 172 petals treated with the active hormone and 57 petals mock-treated. Petals were treated at ten different spur lengths within early development, which have been grouped as Stages 1–3 (Supplementary Data Table S2), with spurs ranging in length from 0.5 to 5 mm when treated.

Virus-induced gene silencing

All three AqBEH genes were targeted for silencing with a double construct that included a non-conserved region of AqBEH1 and a conserved region between the closely related AqBEH3 and AqBEH4. A 192-bp region in the conserved N-terminal domain was selected to target both AqBEH3 and AqBEH4 (90.7 % identical sites in this region), although this may have also been able to target AqBEH1 (79.6 % identity between the three genes in this region). To ensure silencing of AqBEH1, a 258-bp region in exon 2 of AqBEH1 was also selected (for all primers used see Supplementary Data Table S1). A region of the A. coerulea ANTHOCYCANIDIN SYNTHASE (AqANS) gene was also included as a silencing marker. These regions were amplified and ligated into the TRV2 vector to generate the TRV2-AqBEH1-AqBEH3/4-AqANS construct. A TRV2 construct containing AqANS alone was also used as a control. These constructs were transformed into GV3103 electrocompetent Agrobacterium cells. Infiltrations were carried out following previously published protocols (Gould and Kramer, 2007; Sharma and Kramer, 2013). A total of 392 plants were treated with TRV2-AqBEH1-AqBEH3/4-AqANS and 100 control plants were treated with TRV2-AqANS.

qPCR analysis of gene expression

Wildtype AqBEH expression was quantified in three broadly defined developmental stages: early, middle and late (Supplementary Data Table S3). Early stages include pooled RNA from Stages 1–3, middle stages include pooled RNA from Stages 5 and 7 and late stage includes RNA from Stage 8. Petal expression was quantified in all three stages, whereas sepal, stamen, staminode and carpel expression was quantified in early and late stages only. Virus-induced gene silencing (VIGS) tissue was quantified at late stage only. The following extraction and quantification protocol was used for both experiments. Total RNA was extracted with PureLink Plant RNA Reagent (ThermoFisher Scientific), DNA was removed using Turbo DNase (Ambion), and cDNA was synthesized with an iScript cDNA synthesis kit (Bio-Rad). Quantitative real-time polymerase chain reaction (RT-qPCR) was carried out using 10 ng of cDNA (concentration estimated based on total RNA used in cDNA synthesis) as a template amplified with PerfeCTa SYBR Green FastMix Reaction Mix, Low ROX (Quantabio, Beverly, MA, USA) in the Stratagene Mx3005P QPCR System (Stratagene, La Jolla, CA, USA). Three technical replicates were assayed per tissue type. Primer efficiency was checked with a cDNA serial dilution and efficiency was determined using the slope of the linear regression. Relative expressions of AqBEH genes were calculated using the 2-ΔΔCt method (Livak and Schmittgen, 2001) (for all primers see Supplementary Data Table S1). AqIDI (ISOPENTENYL-DIPHOSPHATE DELTA-ISOMERASE) (Aqcoe2G421100) was used for normalization (Sharma and Kramer, 2013).

Scanning electron microscopy

Petals for scanning electron microscopy (SEM) were fixed in FAA (4 % formalin, 5 % glacial acetic acid, 50 % ethanol), and dehydrated through an ethanol series to 100 % and critical-point dried. Tissue was imaged using a Jeol JSM-6010 LC scanning electron microscope (Jeol USA, Peabody, MA, USA). Cells were measured using FIJI imaging software (Schindelin et al., 2012).

Cell counts and measurements

Hormone- and mock-treated petals were fixed in FAA (4 % formalin, 5 % glacial acetic acid, 50 % ethanol), dehydrated to 70 % and stored at 4 °C. Petals were mounted on glass slides with CytoSeal 60 (Electron Microscopy Sciences) and clamped with a coverslip until sealed. Petals were imaged using an AxioCam 512 camera mounted on a Zeiss AxioImager microscope. Each spur was imaged at ×200 magnification along a continuous transect from the attachment point to the nectary, using DIC illumination. A line of contiguous cells from the attachment point to the nectary was measured for length and width using FIJI (Schindelin et al., 2012). Cell area (A) was calculated as A = lw and cell anisotropy (E) was calculated as E = l/w.

RESULTS

Identification of BEH genes in Aquilegia

A previous transcriptomic study of early spur development in A coerulea identified a homologue of A. thaliana BES1/BZR1 HOMOLOG 4 (BEH4) that is strongly enriched in the 3-mm cup of the developing petal spur (Yant et al., 2015). In A. thaliana, BEH4 is a member of the BES1/BZR1 family of BR response proteins, which have been shown to be transcription factors that regulate the expression of downstream BR response genes, including many related to cell elongation (Wang et al., 2002; Yin et al., 2002; Chen et al., 2019). The enrichment of a BES1/BZR1 homologue suggests a possible role for BRs in the switch from cell division to cell elongation in the Aquilegia petal spur. To identify all members of this gene family in Aquilegia, we used the conserved N-terminus domain of the BES1/BZR1 family (PFAM) to search the Aquilegia genome, which revealed two further BES1/BZR1-related proteins in Aquilegia. To understand the orthologous relationships of these three genes, we used BLAST to search for BES1/BRZ1 homologues in 21 plant genera across 17 families and used the resultant 91 amino acid sequences to generate a maximum likelihood phylogeny (Supplementary Data Fig. S1). Angiosperm BES1/BZR1 proteins fall into two strongly supported clades, one of which includes the A. thaliana BES1, BZR1, BEH1 and BEH2 proteins, and its sister clade, which includes the A. thaliana BEH3 and BEH4 proteins. The previously identified Aquilegia protein AqBEH4 (Aqcoe1G215900) falls as expected in the BEH3 and BEH4 clade, and is sister to another Aquilegia protein, here named AqBEH3 (Aqcoe4G027100), although the AqBEH3 and AqBEH4 loci are equally related to both BEH3 or BEH4. The third Aquilegia protein falls into the BES1/BRZ1 clade and is therefore named AqBEH1 (Aqcoe6G111000).

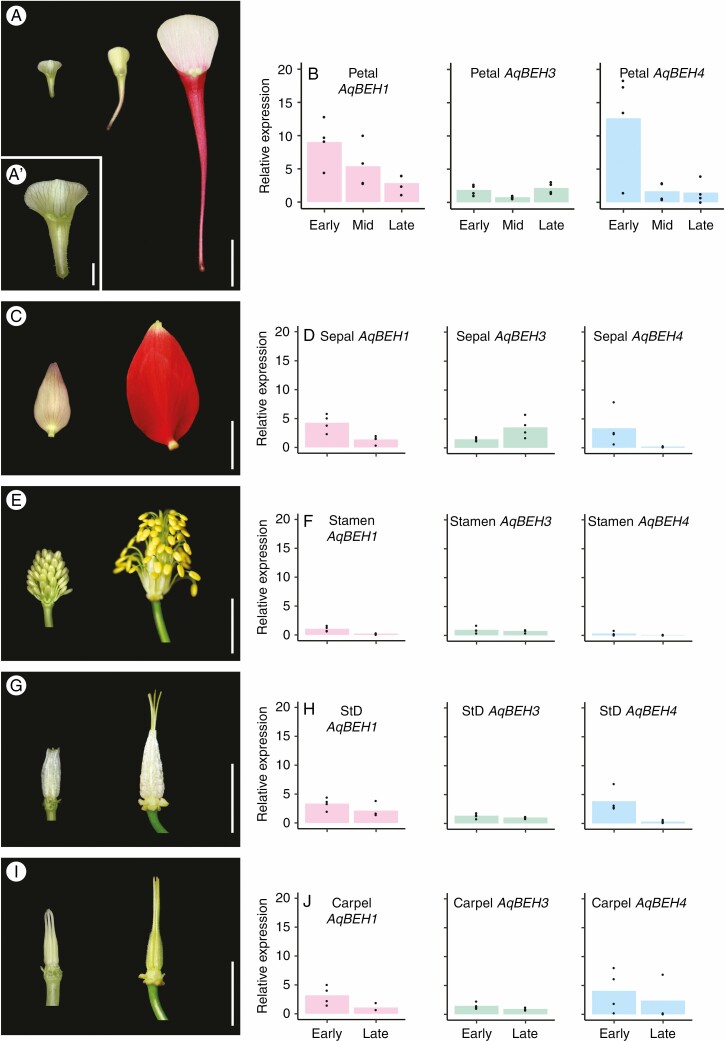

BEH genes are most highly expressed in early stages of petal development

To investigate the possible tissue-specific role of these genes, relative expression was quantified using RT-qPCR across all five floral organs in A coerulea (sepals, petals, stamens, staminodes and carpels). The tissue sampled included three development stages of petals: early, middle and late, as well as the corresponding early and late stages of sepals, stamens, staminodes and carpels (Supplementary Data Table S3). All three Aquilegia BEH genes were expressed in all floral organs throughout the developmental stages examined here (Fig. 1). Notably, in Aquilegia petals the highest expression for AqBEH1 and AqBEH4 was in young petals, in which expression was at least 2-fold higher than in other floral organs at the same stage, or in petals at later stages (Fig. 1B). AqBEH3 expression was relatively low in petals at all stages but slightly increased in late stages (Fig. 1B). As the petals mature, the expression of both AqBEH1 and AqBEH4 decreases, with AqBEH4 dropping rapidly after the early stage, while AqBEH1 tapers off more slowly. In sepals, the pattern is similar, including higher expression of AqBEH1 and AqBEH4 at early stages and a reduction of expression at maturity (Fig. 1D). AqBEH3 expression increases at later stages of sepal growth. In stamens, expression of all three AqBEH genes is low, but is again higher at early stages than at maturity for all three genes (Fig. 1F). Expression in staminodes and carpels is similar: both are relatively low compared with petals, but the expression is higher at early stages and drops at maturity (Fig. 1H, J). In summary, these data show that the AqBEH1 and AqBEH4 genes are highly expressed at early stages of all floral organs, compared with later stages in the same organs, with particularly strong expression in early petals, while AqBEH3 is more weakly expressed.

Fig. 1.

Relative expression patterns of Aquilegia BEH genes in floral organs. (A) Petals representing early, mid and late stages sampled for RT-qPCR. Scale bar = 1 cm. (A′) shows the early petal stage magnified. Scale bar = 1 mm. (C, E, G, I) Sepals, stamens, staminodes and carpels, respectively, each representing early and late stages sampled for RT-qPCR. Scale bars = 1 cm. (B, D, F, H, K) Expression of AqBEH1, AqBEH3 and AqBEH4 in each respective organ [petals, sepals, stamens, staminodes (StD) and carpels].

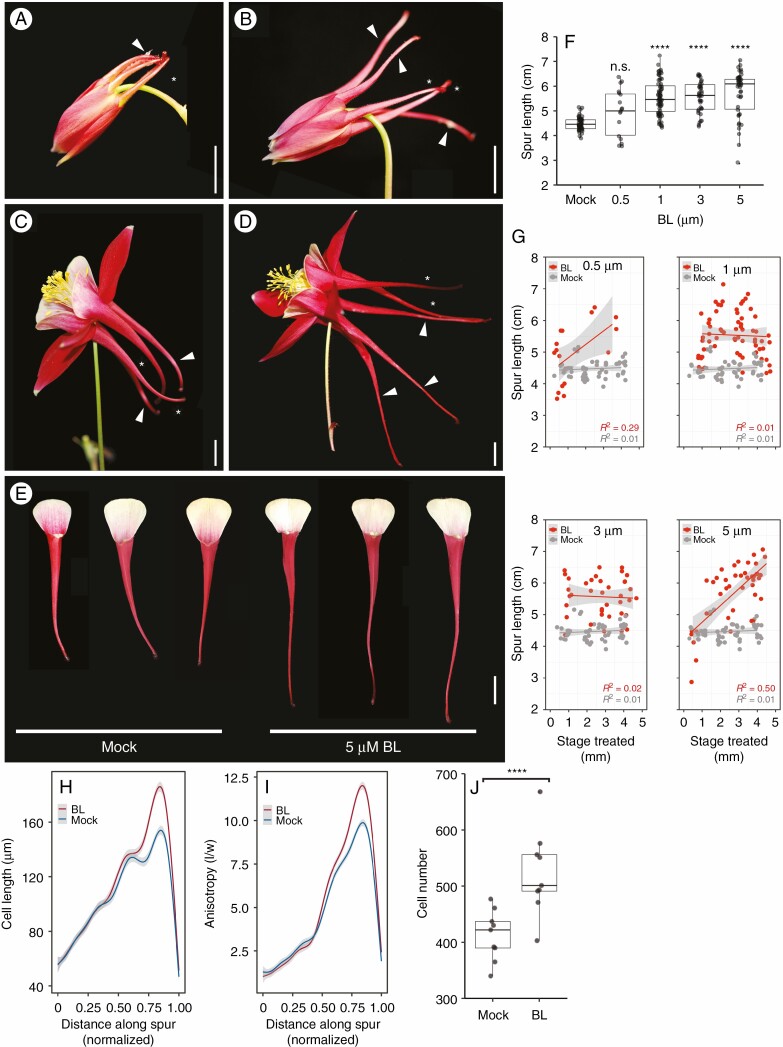

Application of BL increases the average length of the petal spur

Since BR response genes appear to be active in petal development, we set out to investigate the effects of increased BRs on spur development. We exogenously applied BL, the most biologically active form of BR, to the growing tips of Aquilegia spurs. The hormone was applied to a range of early development stages (spur lengths of 0·5–5 mm) and four concentrations (0·5, 1, 3 and 5 μm) as well as a mock treatment (Supplementary Data Table S2). The response to BL treatment was easily observed within 1–2 d of treatment, with petals appearing elongated compared with mock-treated flowers (Fig. 2A, B). At maturity, the average length of BL-treated petals increased by 1–1·5 cm compared with mature mock-treated flowers (average 4.5 cm) (Fig. 2C, F) and wildtype petals (4·4 cm, n = 396, Supplementary Data Fig. S2). On average, the higher the BL concentration, the longer the petal became [5 cm (0·5 μm), 5·5 cm (1 μm), 5·6 cm (3 μm), 5·7 cm (5 μm)] (Fig. 2F). In all concentrations except 0·5 μm, this increase in spur length was significant (Fig. 2F, P < 0·0001). In addition to increased spur length, we observed a few spurs that were actually reduced in length by the hormone application. To investigate if the stage when BRs were applied and/or the hormone concentration affected either the decrease or increase in spur length in treated petals, we compared petal spurs at different concentrations during different stages of spur development. We found that the greatest spur length increase was in the lowest (0·5 μm) and highest (5 μm) treatment concentration groups when treatment occurred after the spur was at least 3 mm in length (Fig. 2G). In contrast, shortened spurs also occurred within these two concentrations but this phenotype occurred only in those petals treated when the spur was ≤1 mm. At moderate concentrations (1 and 3 μm ) the petals were longer regardless of when the hormone was applied. Although no other phenotypic change other than length was observed, the shape of the nectary was distorted in a small proportion of the treated spurs; however, the nectary secreting cells were unaffected and nectar was produced (Supplementary Data Fig. S3A–D), indicating that the increase in hormone did not affect the function of the nectary.

Fig. 2.

Exogenous application of BL increases spur length via increases in cell elongation, anisotropy and cell number. (A) Immature mock-treated control A. coerulea flower 2 d after treatment. Treated petals (arrowhead) are similar to non-treated petals (asterisk). (B) Immature BL-treated flower 2 d after treatment. Treated petals (arrowheads) are longer than non-treated petals (asterisks). (C) Mock-treated control mature flower. Treated petals (arrowheads) are consistent in length with non-treated petals (asterisks). (D) Brassinolide-treated mature flower. Three treated petals (arrowheads) are significantly longer than the two untreated petals (asterisks). (E) Three mock-treated petals compared with three BL (5 μm BL)-treated A. coerulea petals. All petals were treated at 3 mm spur length. (F) Spur length of mock-treated petals (n = 57) and petals treated with BL at 0·5 (n = 17), 1 (n = 69), 3 (n = 44) and 5 μm (n = 42). One-way ANOVA with Tukey HSD, ****P < 0·0001. (G) Scatterplots of spur length versus concentration, plotted by the developmental stage of spur when treated (length in mm). For 0·5 and 5 μm, the spurs are longer when treated at a later stage compared with 1 and 3 μm, where spurs are longer than mock-treated petals regardless of treatment stage. Grey band represents 95 % confidence interval. P values: 0·5 μm BL = 0·00245*, mock = 0·4489; 1 μm BL = 0·7287, mock = 0·4889; 3 μm BL = 0.775, mock = 0·4889; 5 μm BL = 1·923e-07****, mock = 0·4889. (H) Average cell length in mock-treated (n = 9) and BL-treated petals (n = 9). Spur lengths are normalized to 1·0. Grey shading represents 95 % confidence interval. Welch t-test, P < 0·0001. (I) Average cell anisotropy in mock-treated (n = 9) and BL-treated petals (n = 9). Spur lengths are normalized to 1·0. Grey shading represents 95 % confidence interval. Welch t-test, P < 0.02034. (J) Mean cell number per spur between mock-treated (n = 9) and BL-treated spurs (n = 9). Welch t-test, ****P < 0·002215. Scale bars = 1 cm.

Cell number, cell length and cell anisotropy increase with an increase in BR concentration in the Aquilegia petal spur

To determine the cellular mechanism generating the increase in spur length under high BR conditions, we measured the length and width of a contiguous file of cells from the attachment point to the nectary in mock-treated (n = 9) and treated spurs (n = 9). Cells in the BL-treated spurs were significantly longer on average (Fig. 2H; mock = 97·9 μm; BL = 102·4, P < 0.0001) but the increase in cell length did not occur evenly along the length of the spur; in fact, cell length did not increase significantly near the attachment point or near the nectary. Instead, the increase in length occurred in the lower third of the spur only, indicating that the effect of BL on cell elongation was limited to a subset of cells within the spur (Fig. 2H). The effect of BL treatment on cell anisotropy has a similar pattern: BL-treated spurs have increased anisotropic elongation in cells in the lower third of the spur (Fig. 2I; mock = 4·115; BL = 4·3059, P < 0.0001) when compared with mock-treated spurs. Interestingly, under high BL conditions, the mean number of cells in treated spurs also increased compared with mock spurs, with an average cell number of 523 in treated spurs and 413 in control spurs (Fig. 2J; P < 0.0001).

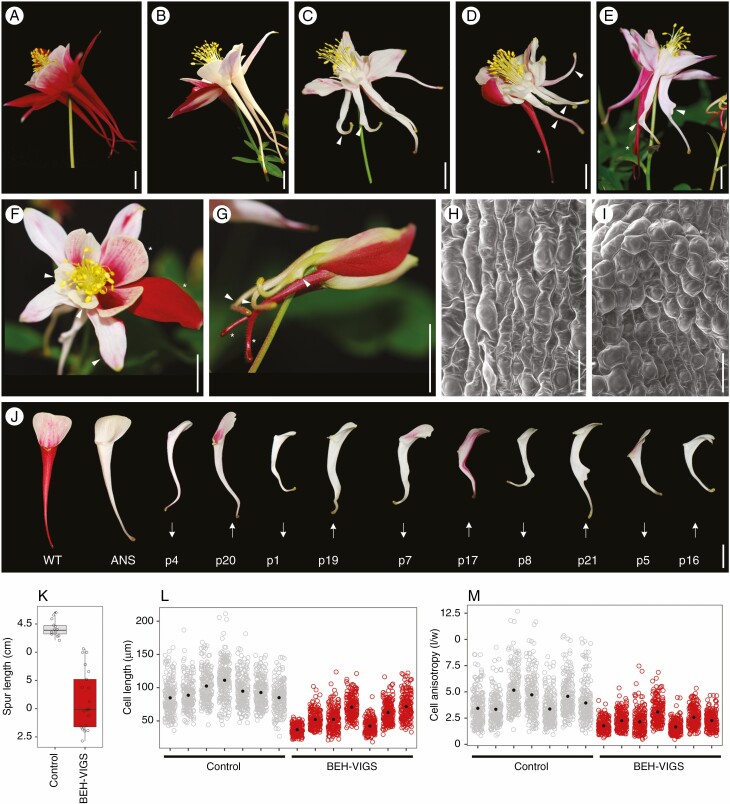

AqBEH genes control spur growth via cell elongation in A. coerulea

In order to understand the function of AqBEH genes in the Aquilegia petal spur, VIGS was used to knock down all three Aquilegia BEH genes, via a double construct that also included a fragment of ANTHOCYANIN SYNTHASE (AqANS) as a silencing marker. Of 392 plants treated, 9 flowers and a total of 21 petals had strong phenotypic modifications compared with ANS control plants (Fig. 2A–G). The petal defects include shortened spurs (Fig. 3D, arrowheads), bends in the lower third of the spur (Fig. 3C, E, G: arrowheads), twists along the lower section of the spur (Fig. 3E, arrowhead) and outgrowths on the abaxial surface (Fig. 3C, E, arrowheads). These defects occurred alone or in combinations, such as bends and outgrowths (Fig. 3C, G), or short and twisted (Fig. 3D). The average lengths of the BEH-VIGS petal spurs were significantly shorter than those of control spurs, having a mean length of 3·14 cm compared with a mean length of 4·42 cm for controls (Fig. 3J, K). Closer examination of the bends and outgrowths using SEM showed that cell files were mis-orientated, with cells often arranged at right angles to the length of the spur (Fig. 3I, Supplementary Data Fig. S4). No change in phenotype was observed in stamens, staminodes or carpels but we observed that the sepals were often smaller in flowers with affected petals (Fig. 3F, Supplementary Data Fig. S5). To understand the cause of shorter petal spurs in the BEH-VIGS-treated plants, cell length and cell anisotropy were measured and compared with ANS control petal spurs. To compare a relatively analogous region of the petals, spurs were divided into four quarters, which included (1) attachment point, (2) mid-spur ‘top’, (3) mid-spur ‘lower’ and (4) nectary quarter. For cell measurements, the mid-spur lower was compared as this corresponds to the previously identified zone of maximum cell elongation. In this area, cells of BEH-VIGS petals were significantly shorter, with a mean length of 55·5 μm compared with 94·2 μm for control petals. (Fig. 3L). Anisotropy was also significantly reduced in BEH-VIGS petal spurs, with a mean of 2·3 compared with 4·1 in control petals (Fig. 3M).

Fig. 3.

Phenotypes of BEH-VIGS; petal spurs are short, twisted or bent. (A) A mature, wildtype A. coerulea flower. (B) A mature, ANS control flower, with three phenotypically normal white petals. (c) Mature BEH-VIGS flower with petals with bends in the lower part of spur and a spur with a 90° bend and abaxial outgrowth (arrowheads). (D) Mature BEH-VIGS flower with three short petal spurs (arrowhead), and one phenotypically normal petal spur (asterisk). (E) Mature BEH-VIGS flower with petal spurs with a twisted petal and abaxial outgrowths (arrowheads), compared with two phenotypically normal spurs (asterisk). (F) Mature BEH-VIGS flower showing phenotypically normal sepals and petal blades (asterisks), compared with small sepals and petal blades (arrowheads). (G) Young BEH-VIGS flower with petal spurs with abaxial outgrowths and 90° bends in the lower spur (arrowheads), compared with two phenotypically normal petal spurs (asterisks). (H) SEM of ANS control lower spur showing anisotropically elongated cell and parallel files of cells in the lower spur. (I) SEM of BEH-VIGS lower spurs showing short, misaligned cells. (J) Comparison of WT, ANS control and BEH-VIGS petals (p). Arrows indicate if a BEH-VIGS petal showed decreased (down) or increased (up) relative expression of AqBEH genes (see Fig. 4). (K) Measurements of petal spur lengths in control (n = 14, mean 4·42 cm) and BEH-VIGS (n = 21, mean 3·14 cm) petals. Welch t-test, P < 0·0001. (L) Cell lengths of ANS control (mean 94·2 μm) and BEH-VIGS petal spurs (mean 55·5 μm). Welch t-test, P < 0·0001. (M) Cell anisotropy of ANS control (mean 4·1) and BEH-VIGS petals spurs (mean 2·3). Welch t-test, P < 0·0001. Scale bars: (A–G, J) = 1 cm; (H–I) = 50 μm.

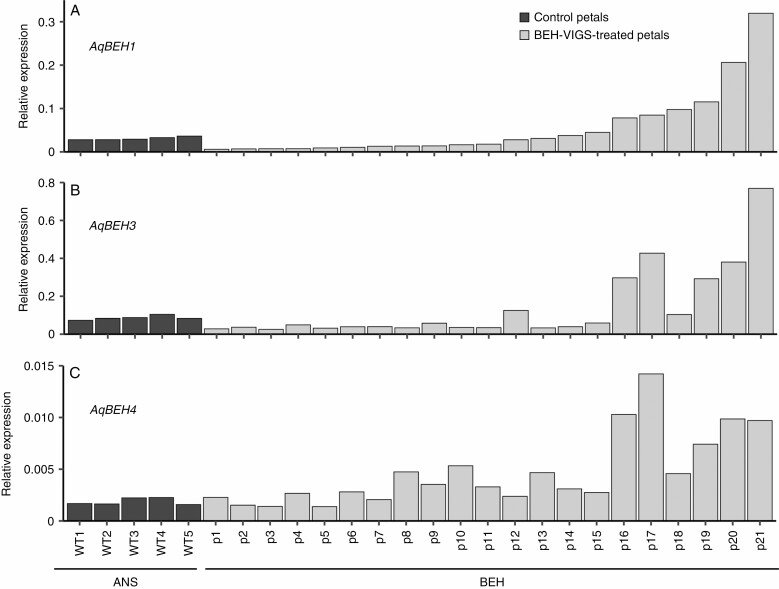

Despite a strong phenotypic response from the BEH-VIGS treatment, the measurement of AqBEH expression in petals showed inconsistent silencing at maturity (Fig. 4). Overall, petals with abnormal phenotypes showed no significant knockdown in the level of AqBEH expression between the triple knockdowns and ANS controls (Supplementary Data Fig. S6d). However, when examined individually, we found that approximately half the petals showed some degree of reduced expression for AqBEH1 and AqBEH3, although the level was not statistically significant. None of the petals showed significant knockdown for AqBEH4. Intriguingly, one-quarter of the petals showed significant overexpression for all three genes (one-way ANOVA, P < 0·00001). Additionally, one quarter of the petals showed no obvious silencing for any of the AqBEH genes. When we attempted to associate a phenotype with the expression levels, we found petals in each phenotypic category with increased, decreased or wildtype expression of AqBEH genes (Fig. 3J, arrowheads showing increased or decreased expression). Interestingly, VIGS sepals showed weak phenotypes (Supplementary Data Fig. S5a–c) but were not significantly knocked down for any gene (Supplementary Data Fig. S6a), yet carpels showed no altered phenotype but AqBEH expression for all three genes was significantly knocked down compared with the control carpels (Supplementary Data Fig. S6c). Similarly, stamens showed no major change in phenotype but were significantly lowered in expression in AqBEH1 and AqBEH4 but not AqBEH3 (Supplementary Data Fig. S6b). Staminodes were not phenotypically altered but were not checked for expression levels due to lack of tissue.

Fig. 4.

Relative expression levels of AqBEH1, AqBEH3 and AqBEH4 in ANS control petals (black) and BEH-VIGS petals (grey). p, silenced petal sample; WT, wildtype.

DISCUSSION

Plants produce complex organs by coordination and organization of cell division and cell expansion (Lyndon, 1990). While cell division is critical to the establishment of an organ, and gives rise to the cells required for growth, the integration of localized and directional expansion is often the major mechanism required to create elaborate organ shapes (reviewed in Facette et al., 2019). Previous studies have shown that species of Aquilegia display remarkable differences in spur length and that this morphological diversity evolved rapidly in association with new pollinators (Whittall and Hodges, 2007). An investigation into spur morphogenesis showed that significant differences in Aquilegia spur length are achieved by variation in highly anisotropic cell elongation (Puzey et al., 2012), yet little is known about the molecular mechanisms controlling the process of anisotropic cell expansion in the developing spur. Intriguingly, transcriptomic experiments detected strong differential expression of genes involved in BR response, known in A. thaliana to regulate the shift from cell division to cell elongation (Yant et al., 2015). Here, we investigated the role of the BR response pathway in regulating spur length and show that BRs are an important regulator of anisotropic cell elongation in A. coerulea.

In the A. coerulea petal spur, highly anisotropic cell elongation increases progressively from the attachment point towards the nectary (Fig. 2I), generating a long, slender tube. Exogenous application of the BR hormone BL increases anisotropic elongation, particularly in the lower half of the spur, leading to a significant increase in spur length. We observed no effect on the gross morphology of the petal or on nectary function, with no effect on cell elongation at or near the nectary, nor in the proximal part of spur near the attachment point. The differential response to BR application along the spur is intriguing since it mirrors the trend observed in control petals, in which cells are longer approaching the nectary. This response pattern could be due to differences in the ability of the cells to respond, or to a gradient of BR concentration from the lanolin applied to the nectary region. The fact that cells closest to the hormone application site, in the nectary itself and immediately adjacent cells, do not show increased length may suggest that this pattern is, at least in part, due to sensitivity and ability to respond. At the same time, it is also clear that the effect of exogenous BR is influenced by hormone concentration, which shows a trend of increased spur length with increased concentration. However, at the highest concentration applied, a small number of spurs were significantly shorter, suggestive of a negative feedback loop that inhibits growth. This type of inhibition by a high concentration of BR has been shown in other model plants, where high levels of exogenous BR have a negative effect on growth in roots and leaves, suggesting that maintaining optimal BR levels is critical for normal growth and development (Szekeres et al., 1996; Clouse and Sasse, 1998, Mussig et al., 2003). In Aquilegia petals, the most severe suppression of growth occurred only in petals treated with high concentration early in development, suggesting that the two distinct developmental phases in the Aquilegia spur (cell division and cell expansion) may be associated with distinct BR response in the Aquilegia petal spur.

Interestingly, cell number also increased in spurs treated with BL (Fig. 2J), indicating that BRs are capable of inducing cell division in the petal spur, but further investigation may reveal if these roles are spatially or temporally restricted. This dual role for BRs is consistent with studies showing that BRs also promote cell division in A. thaliana leaves through regulation of mitosis and cell cycle timing (Nakaya et al., 2002; Gonzales et al., 2010; Oh et al., 2011; Zhiponova et al., 2013). Brassinosteroids are also suggested to regulate the transition from cell proliferation to expansion in A. thaliana leaves (Zhiponova et al., 2013), and the timing of high expression of AqBEH genes in early stages of petal development suggests a similar role for BRs in the A. coerulea petal. This differential control of BR response in different stages of growth suggests a context specific role for BR in both cell proliferation and expansion.

Previous RNAseq data revealed that AqBEH4 expression is enriched in young petal spurs (Yant et al., 2015). Here we show that AqBEH1, AqBEH3 and AqBEH4 genes are expressed in all floral organs throughout development, yet, consistent with previous transcriptomic results, the loci show stage- and organ-specific expression patterns. AqBEH1 and AqBEH4 are both expressed significantly higher in petals than other floral organs and both are more highly expressed in early petal development. These expression patterns are consistent with expression of the six BES1/BZR1 homologues in A. thaliana, which are widely expressed yet also show various differences in expression levels, both developmentally and between organ types (Otani et al., 2020). AqBEH3 and AqBEH4 are very similar at the protein level, likely paralogues due to a recent duplication in Aquilegia, suggesting that AqBEH3 may be acting redundantly with AqBEH4. In A. thaliana, all six proteins in the BES1/BZR1 family are regulated by BR (Yin et al., 2005) and all can act redundantly with each other (Chen et al., 2019). Although the expression patterns in Aquilegia floral tissue suggest some functional differences among AqBEH genes, and perhaps indicate a petal-specific role, in A. thaliana interpretation of expression levels of BES1/BZR1 transcription factors is complicated by the post-translational regulation of BES1/BZR1 (He et al., 2002; Wang et al., 2002; Yin et al., 2002, 2005; Vert and Chory, 2006; Gampala et al., 2007; Shimada et al., 2015; Nolan et al., 2017; Kim et al., 2019). At present it is unknown if this type of regulation also operates in A. coerulea, but we do know that the majority of the BR biosynthesis pathway and signalling cascade factors appear to be conserved across the flowering plants (Ferreira-Guerra et al., 2020) and that all the phosphorylation and dephosphorylation cascade elements from A. thaliana are present in the A. coerulea genome (Filiault et al., 2018).

In A. thaliana, single loss-of-function mutations in either BES1 or BZR1 have no or weak phenotypes; however, a loss-of-function mutant in which all six BES1/BZR1 family members are silenced has the typical BR-insensitive dwarf phenotype (Chen et al., 2019). Therefore, we targeted all three AqBEH genes for silencing in order to determine BR’s role in cell elongation during petal spur development. Based on previous experience with silencing multiple loci simultaneously (Min et al., 2019), we expected a lower success rate, but we were able to recover a number of petals with inhibited growth and defects in the lower spur. Unfortunately, contradictory expression pattern of AqBEH genes in BEH-VIGS petals with strong phenotypes made confirmation of their downregulation challenging. The inconsistent expression pattern may have several possible explanations. First, the relatively low expression of AqBEH genes at organ maturity (Fig. 1B) may have contributed to inaccuracy in the expression analysis. Second, VIGS can result in transient silencing (Lu et al., 2003; Gould and Kramer, 2007), and thus the measurement of expression at organ maturity may not detect silencing that occurred earlier in development. This is further complicated by the probable post-translational regulation of AqBEH genes, which often decouples RNA expression levels from phenotypic effects. Third, some petals experienced upregulation of expression, which is possibly in response to earlier silencing, a phenomenon observed in a number of mutant BES1/BZR1 lines and potentially caused by feedback loops between family members (Wang et al., 2013; Lachowiec et al., 2018; Chen et al., 2019). Supporting this is the fact that petals that did show AqBEH downregulation had strong phenotypic defects similar to those of petals that had wildtype or increased levels of expression (Figs 3J and 4). Also noteworthy is that no phenotypic effect was observed in stamens or carpels although AqBEH genes were downregulated in both organs, suggesting that the observed compensation was specific to organs showing strong dependence on BR function. We should further note that although there is a small family of β-amylase genes in the Aquilegia genome that share some sequence similarity with the BEH family (Filiault et al., 2018), this never rises above 54 % identity in the region of the VIGS fragment, making it extremely unlikely that the phenotypes are due to off-target silencing. Despite the fact that the mechanism regulating the expression and co-ordination of AqBEH genes is not yet known, taken together, we believe that the preponderance of the evidence suggests that petals with strong petal phenotypes did experience AqBEH silencing at critical stages of development.

The consistent phenotype observed across the VIGS petals is a shortening of the spurs, due to reduced anisotropy of cells in the lower spur. Given that exogenous BL application led to an increase in anisotropic elongation and longer spurs, this suggests a tight coupling of BR response and spur length in A. coerulea. This result is consistent with studies in A. thaliana where BRs play critical roles in cell expansion – defects in BR biosynthesis, perception and response all result in dwarf phenotypes due to smaller cell size (Clouse et al., 1996; Szekeres et al., 1996; Li and Chory, 1997; Azpiroz et al., 1998; Choe et al., 1998; Friedrichsen et al., 2000; Li et al., 2001; Wang et al., 2001). The other strong defect observed in some petals was the localized miscoordination of growth in the lower spur in A. coerulea, leading to twists, bends and abaxial outgrowths within the spur tube. This indicates that AqBEH genes act, likely via downstream targets, to maintain synchronously orientated cell elongation as well as appropriately orientated cell division. This would be in line with observed roles for A. thaliana BES1/BZR1 in modulating cell wall organization by promoting cellulose synthesis and microtubule reorganization and orientation to facilitate cell elongation (Tang et al., 2008; Sun et al., 2010; Lanza et al., 2012; Wang et al., 2012; Sánchez-Rodrígues et al., 2017; Liu et al., 2018; Ruan et al., 2018). For example, BZR1 binds directly to the promoter of PCAP1/2, a gene shown to coordinate cortical microtubule organization and regulate directional cell elongation (Tang et al., 2008; Sun et al., 2010). It is also likely that the nature of VIGS silencing contributed to these distortions in spur shape; hormone application is more likely to have an even effect on tissue whereas VIGS silencing can be sectorial, in terms of both its spatial and temporal components (Min et al., 2019).

While BRs are best known for their role in promoting cell elongation, other plant hormones, such as auxin, play a major role in developmental processes important to spur development, including cell orientation and elongation (Gallei et al., 2020; Heisler and Byrne, 2020). Auxin signalling response transcription factors, AUXIN RESPONSE FACTOR6 (ARF6) and AUXIN RESPONSE FACTOR8 (ARF8), have been shown to play an active role in anisotropic cell elongation in A. coerulea petal spurs and silencing of AqARF6/8 also leads to shorter spurs (Zhang et al., 2020). These overlapping roles for BR and auxin in the A. coerulea spur are not surprising given the crosstalk between the auxin and BR pathways (Nemhauser et al., 2004, Vert et al., 2008; Sun et al., 2010; Cho et al., 2014; Oh et al., 2014; Xiong et al., 2021). For example, BZR1 directly interacts with ARF6 and PHYTOCHROME INTERACTING FACTOR4 (PIF4) in order to promote auxin response in cell elongation, and together they co-operatively share promoter sites of many downstream target genes. Identifying downstream AqBEH targets will be an important next step in determining how BR regulates cell elongation in Aquilegia, and a starting point to untangle the synergistic interactions of both hormonal and developmental cues operating in the petal spur.

Integrating our newfound understanding of how BRs promote spur length in A. coerulea has generated a more complete picture of the dynamic interplay of multiple developmental processes that sculpt petal shape in Aquilegia. Early spur growth requires AqPOP in order to promote and maintain cell proliferation (Ballerini et al., 2020); AqTCP4 likely plays a role in repressing cell division at the end of Phase I growth (Yant et al., 2015); and auxin and BR may play coordinated roles in promoting cell expansion and anisotropic elongation in order to generate the final length of the petal spur (Zhang et al., 2020). Our results indicate that, unlike auxin, the BR response in petal spurs is not highly pleiotropic, making BR regulation a good candidate for playing a key role in the evolutionary modification of petal spur length.

SUPPLEMENTARY DATA

Supplementary data are available online at https://academic.oup.com/aob and consist of the following. Figure S1: phylogenetic relationship of BES1/BZR and BEH proteins. Figure S2: spur measurements of wildtype flowers. Figure S3: SEM of nectaries of four BL-treated spurs. Figure S4: SEM of BEH-VIGS petals with bends and outgrowths. Figure S5: sepal phenotypes of BEH-VIGS petals. Figure S6: relative expression levels of AqBEH genes in VIGS tissue. Table S1: list of primers used in this study. Table S2: list of development stages and concentrations used in BR application experiment. Table S3: list of stages used in wildtype BEH expression study.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

We thank Tom Saide, Mary Katherine DeWane and Joanna Ladopoulou for help with tissue collection. We are also thankful to members of the Kramer Lab for helpful comments on the manuscript. Preliminary experiments and planning were performed by C.L.W.C., K.S.B. and E.M.K. C.L.W.C. and K.S.B. conducted the initial identification of Aquilegia coerulea BEH orthologues. Following on from this work, S.J.C. and E.M.K. planned and designed the presented research. S.J.C. performed the research and analysed data. S.J.C. wrote the manuscript with input from E.M.K.

FUNDING

This work was supported by National Science Foundation award IOS-1456217 to E.M.K.

LITERATURE CITED

- Azpiroz R, Wu Y, LoCascio, JC, Feldmann KA. 1998. An arabidopsis brassinosteroid-dependent mutant is blocked in cell elongation. Plant Cell 10: 219–230. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ballerini ES, Min Y, Edwards MB, Kramer EM, Hodges SA. 2020. POPOVICH, encoding a C2H2 zinc-finger transcription factor, plays a central role in the development of a key innovation, floral nectar spurs, in Aquilegia. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the USA 117: 22552–22560. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen L-G, Gao Z, Zhao Z, et al. 2019. BZR1 family transcription factors function redundantly and indispensably in BR signaling but exhibit BRI1-independent function in regulating anther development in arabidopsis. Molecular Plant 12: 1408–1415. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cho H, Ryu H, Rho S, Hill K, Smith S, Audenaert D, et al. 2014. A secreted peptide acts on BIN2-mediated phosphorylation of ARFs to potentiate auxin response during lateral root development. Nature Cell Biology 16: 66–76. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clouse SD. 1996. Molecular genetic studies confirm the role of brassinosteroids in plant growth and development. Plant Journal 10: 1–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clouse SD, Sasse JM. 1998. BRASSINOSTEROIDS: essential regulators of plant growth and development. Annual Review of Plant Physiology and Plant Molecular Biology 49: 427–451. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Facette MR, Rasmussen CG, Van Norman JM. 2019. A plane choice: coordinating timing and orientation of cell division during plant development. Current Opinion in Plant Biology 47: 47–55. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ferreira-Guerra M, Marquès-Bueno M, Mora-García S, Caño-Delgado AI. 2020. Delving into the evolutionary origin of steroid sensing in plants. Current Opinion in Plant Biology 57: 87–95. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Filiault DL, Ballerini ES, Mandáková T, et al. 2018. The Aquilegia genome provides insight into adaptive radiation and reveals an extraordinarily polymorphic chromosome with a unique history. eLife 7. doi: 10.7554/eLife.36426. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Friedrichsen DM, Joazeiro CA, Li J, Hunter T, Chory J. 2000. Brassinosteroid-insensitive-1 is a ubiquitously expressed leucine-rich repeat receptor serine/threonine kinase. Plant Physiology 123: 1247–1256. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gallei M, Luschnig C, Friml J. 2020. Gallei, M., Luschnig, C., & Friml, J. (2020). Auxin signalling in growth: Schrödinger’s cat out of the bag. Current Opinion in Plant Biology, 53, 43–49.. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gampala SS, Kim T-W, He J-X, Tang W, Deng Z, Bai M-Y, et al. 2007. An essential role for 14-3-3 proteins in brassinosteroid signal transduction in Arabidopsis. Developmental Cell 13: 177–189. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gonzalez N, De Bodt S, Sulpice R, et al. 2010. Increased leaf size: different means to an end. Plant Physiology 153: 1261–1279. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gould B, Kramer EM. 2007. Virus-induced gene silencing as a tool for functional analyses in the emerging model plant Aquilegia (columbine, Ranunculaceae). Plant Methods 3: 6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guo H, Li L, Aluru M, Aluru S, Yin Y. 2013. Mechanisms and networks for brassinosteroid regulated gene expression. Current Opinion in Plant Biology 16: 545–553. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gupta A, Singh M, Jones AM, Laxmi A. 2012. Hypocotyl directional growth in arabidopsis: a complex trait. Plant Physiology 159: 1463–1476. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hao Y, Wang H, Qiao S, Leng L, Wang X. 2016. Histone deacetylase HDA6 enhances brassinosteroid signaling by inhibiting the BIN2 kinase. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the USA 113: 10418–10423. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- He J-X, Gendron JM, Yang Y, Li J, Wang Z-Y. 2002. The GSK3-like kinase BIN2 phosphorylates and destabilizes BZR1, a positive regulator of the brassinosteroid signaling pathway in Arabidopsis. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the USA 99: 10185–10190. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- He J-X, Gendron JM, Sun Y, et al. 2005. BZR1 is a transcriptional repressor with dual roles in brassinosteroid homeostasis and growth responses. Science 307: 1634–1638. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- He Z, Wang, ZY, Li J, Zhu Q, Lamb C, Ronald P, Chory J. 2000. Perception of brassinosteroids by the extracellular domain of the receptor kinase BRI1. Science 288: 2360–2363. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heisler, MG, Byrne ME. 2020. Progress in understanding the role of auxin in lateral organ development in plants. Current Opinion in Plant Biology 53: 73–79. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang G, Han M, Yao W, Wang Y. 2017. Transcriptome analysis reveals the regulation of brassinosteroids on petal growth in Gerbera hybrida. PeerJ 5: e3382. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim E-J, Lee S-H, Park C-H, et al. 2019. Plant U-Box40 mediates degradation of the brassinosteroid-responsive transcription factor BZR1 in arabidopsis roots. Plant Cell 31: 791–808. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim T-W, Guan S, Sun Y, et al. 2009. Brassinosteroid signal transduction from cell-surface receptor kinases to nuclear transcription factors. Nature Cell Biology 11: 1254–1260. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lachowiec J, Mason, GA, Schultz K, Queitsch C. 2018. Redundancy, feedback, and robustness in the Arabidopsis thaliana BZR/BEH gene family. Frontiers in Genetics 9. doi: 10.3389/fgene.2018.00523. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lanza M, Garcia-Ponce B, Castrillo G, et al. 2012. Role of actin cytoskeleton in brassinosteroid signaling and in its integration with the auxin response in plants. Developmental Cell 22: 1275–1285. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li J, Chory J. 1997. A putative leucine-rich repeat receptor kinase involved in brassinosteroid signal transduction. Cell 90: 929–938. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li J, Nagpal P, Vitart V, McMorris, TC, Chory J. 1996. A role for brassinosteroids in light-dependent development of arabidopsis. Science 272: 398–401. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li J, Nam, KH, Vafeados D, Chory J. 2001. BIN2, a new brassinosteroid-insensitive locus in arabidopsis. Plant Physiology 127: 14–22. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li J, Wen J, Lease KA, Doke JT, Tax FE, Walker JC. 2002. BAK1, an Arabidopsis LRR receptor-like protein kinase, interacts with BRI1 and modulates brassinosteroid signaling. Cell 110: 213–222. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lin X, Huang S, Huang G, Cheng Y, Wang X. 2021. 14-3-3 proteins are involved in BR-induced ray petal elongation in Gerbera hybrida. Frontiers in Plant Science 12: 718091. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu X, Yang Q, Wang Y, Wang L, Fu Y, Wang X. 2018. Brassinosteroids regulate pavement cell growth by mediating BIN2-induced microtubule stabilization. Journal of Experimental Botany 69: 1037–1049. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Livak KJ, Schmittgen TD. 2001. Analysis of relative gene expression data using real-time quantitative PCR and the 2(-Delta Delta C(T)) method. Methods, 25: 402–408. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lyndon, R. 1990. Plant development: The cellular basis (Topics in plant physiology; 3). London; Boston: Unwin Hyman. [Google Scholar]

- Lu, R. 2003. Virus-induced gene silencing in plants. Methods: 30: 296–303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lyndon RF. 1990. Plant Development. In: Hyman U. ed. Vol. 3. [Google Scholar]

- Min Y, Bunn JI, Kramer EM. 2019. Homologs of the STYLISH gene family control nectary development in Aquilegia. New Phytologist 221: 1090–1100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Müssig C, Shin G-H, Altmann T. 2003. Brassinosteroids promote root growth in Arabidopsis. Plant Physiology 133: 1261–1271. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nakaya M, Tsukaya H, Murakami N, Kato M. 2002. Brassinosteroids control the proliferation of leaf cells of Arabidopsis thaliana. Plant and Cell Physiology 43: 239–244. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nam KH, Li J. 2002. BRI1/BAK1, a receptor kinase pair mediating brassinosteroid signaling. Cell 110: 203–212. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nemhauser JL, Mockler, TC, Chory J. 2004. Interdependency of brassinosteroid and auxin signaling in Arabidopsis. PLoS Biology 2: E258. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nolan TM, Brennan B, Yang M, Chen J, Zhang M, Li Z, et al. 2017. Selective autophagy of BES1 mediated by DSK2 balances plant growth and survival. Developmental Cell 41: 33–46.e7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nolan TM, Vukašinović N, Liu D, Russinova E, Yin Y. 2020. Brassinosteroids: multidimensional regulators of plant growth, development, and stress responses. Plant Cell 32: 295–318. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oh E, Zhu J-Y, Bai M-Y, Arenhart RA, Sun Y, Wang Z-Y. 2014. Cell elongation is regulated through a central circuit of interacting transcription factors in the Arabidopsis hypocotyl. eLife. doi: 10.7554/eLife.03031. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oh M-H, Sun J, Oh DH, Zielinski RE, Clouse SD, Huber SC. 2011. Enhancing arabidopsis leaf growth by engineering the BRASSINOSTEROID INSENSITIVE1 receptor kinase. Plant Physiology 157: 120–131. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Otani Y, Tomonaga Y, Tokushige K, et al. 2020. Expression profiles of four BES1/BZR1 homologous genes encoding bHLH transcription factors in Arabidopsis. Journal of Pesticide Science 45: 95–104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Puzey JR, Gerbode SJ, Hodges SA, Kramer EM, Mahadevan L. 2012. Evolution of spur-length diversity in Aquilegia petals is achieved solely through cell-shape anisotropy. Proceedings of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences 279: 1640–1645. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ruan Y, Halat, LS, Khan D, et al. 2018. The microtubule-associated protein CLASP sustains cell proliferation through a brassinosteroid signaling negative feedback loop. Current Biology 28: 2718–2729.e5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ryu H, Kim K, Cho H, Park J, Choe S, Hwang I. 2007. Nucleocytoplasmic shuttling of BZR1 mediated by phosphorylation is essential in arabidopsis brassinosteroid signaling. Plant Cell 19: 2749–2762. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sánchez-Rodríguez C, Ketelaar K, Schneider R, et al.. 2017. BRASSINOSTEROID INSENSITIVE2 negatively regulates cellulose synthesis in Arabidopsis by phosphorylating cellulose synthase 1. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the USA 114: 3533–3538. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sharma B, Kramer EM, 2013. Virus-induced gene silencing in the rapid cycling Columbine Aquilegia coerulea “Origami.” In Virus-Induced Gene Silencing (Vol. 975, pp. 71–81). Totowa, NJ: Humana Press. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shimada S, Komatsu T, Yamagami A, et al. 2015. Formation and dissociation of the BSS1 protein complex regulates plant development via brassinosteroid signaling. Plant Cell 27: 375–390. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sun Y, Fan X-Y, Cao D-M, et al. 2010. Integration of brassinosteroid signal transduction with the transcription network for plant growth regulation in arabidopsis. Developmental Cell 19: 765–777. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Szekeres M, Németh K, Koncz-Kálmán Z, et al. 1996. Brassinosteroids rescue the deficiency of CYP90, a cytochrome P450, controlling cell elongation and de-etiolation in Arabidopsis. Cell 85: 171–182. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tang W, Deng Z, Oses-Prieto, et al. 2008. Proteomics studies of brassinosteroid signal transduction using prefractionation and two-dimensional DIGE. Molecular & Cellular Proteomics 7: 728–738. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tong H, Xiao Y, Liu D, et al. 2014. Brassinosteroid regulates cell elongation by modulating gibberellin metabolism in rice. Plant Cell 26: 4376–4393. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Trifinopoulos J, Nguyen LT, Haeseler von A, Minh BQ. 2016. W-IQ-TREE: a fast online phylogenetic tool for maximum likelihood analysis. Nucleic Acids Research, 44: W232–5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schindelin J, Arganda-Carreras I, Frise E, et al. 2012. Fiji: an open-source platform for biological-image analysis. Nature Methods, 9: 676–682. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vert G, Chory J. 2006. Downstream nuclear events in brassinosteroid signalling. Nature 441: 96–100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vert G, Walcher CL, Chory J, Nemhauser JL. 2008. Integration of auxin and brassinosteroid pathways by auxin response factor 2. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the USA 105: 9829–9834. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang X, Kota U, He K, et al. 2008. Sequential transphosphorylation of the BRI1/BAK1 receptor kinase complex impacts early events in brassinosteroid signaling. Developmental Cell 15: 220–235. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang X, Zhang J, Yuan M, Ehrhardt DW, Wang Z, Mao T. 2012. Arabidopsis microtubule destabilizing protein40 is involved in brassinosteroid regulation of hypocotyl elongation. Plant Cell 24: 4012–4025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang Y, Sun S, Zhu W, Jia K, Yang H, Wang X. 2013. Strigolactone/MAX2-induced degradation of brassinosteroid transcriptional effector BES1 regulates shoot branching. Developmental Cell 27: 681–688. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang Z-Y, Seto H, Fujioka S, Yoshida S, Chory J. 2001. BRI1 is a critical component of a plasma-membrane receptor for plant steroids. Nature 410: 380–383. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang ZY, Nakano T, Gendron J, et al. 2002. Nuclear-localized BZR1 mediates brassinosteroid-induced growth and feedback suppression of brassinosteroid biosynthesis. Developmental Cell 2: 505–513. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Whitewoods CD, Coen E. 2017. Growth and development of three-dimensional plant form. Current Biology 27: R910–R918. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Whittall JB, Hodges, SA. 2007. Pollinator shifts drive increasingly long nectar spurs in columbine flowers. Nature 447: 706–709. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xiong Y, Wu B, Du F, et al. 2021. A crosstalk between auxin and brassinosteroid regulates leaf shape by modulating growth anisotropy. Molecular Plant 14: 949–962. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yamagami A, Saito C, Nakazawa M, et al. 2017. Evolutionarily conserved BIL4 suppresses the degradation of brassinosteroid receptor BRI1 and regulates cell elongation. Scientific Reports 7: 27. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yant L, Collani S, Puzey J, Levy C, Kramer EM. 2015. Molecular basis for three-dimensional elaboration of the Aquilegia petal spur. Proceedings of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences 282: 20142778. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yin Y, Wang Z-Y, Mora-García S, et al. 2002. BES1 accumulates in the nucleus in response to brassinosteroids to regulate gene expression and promote stem elongation. Cell 109: 181–191. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yin Y, Vafeados D, Tao Y, Yoshida S, Asami T, Chory J. 2005. A new class of transcription factors mediates brassinosteroid-regulated gene expression in arabidopsis. Cell 120: 249–259. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang L-Y, Bai M-Y, Wu J, et al. 2009. Antagonistic HLH/bHLH transcription factors mediate brassinosteroid regulation of cell elongation and plant development in rice and arabidopsis. Plant Cell 21: 3767–3780. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang R, Min Y, Holappa, LD, et al. 2020. A role for the auxin response factors ARF6 and ARF8 homologs in petal spur elongation and nectary maturation in Aquilegia. New Phytologist 227: 1392–1405. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhao J, Peng P, Schmitz RJ, Decker AD, Tax FE, Li J. 2002. Two putative BIN2 substrates are nuclear components of brassinosteroid signaling. Plant Physiology 130: 1221–1229. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhiponova, MK, Vanhoutte I, Boudolf V, et al. 2013. Brassinosteroid production and signaling differentially control cell division and expansion in the leaf. New Phytologist 197: 490–502. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhu J-Y, Li Y, Cao D-M, et al. 2017. The F-box protein KIB1 mediates brassinosteroid-induced inactivation and degradation of GSK3-like kinases in arabidopsis. Molecular Cell 66: 648–657.e4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.