Abstract

Purpose of review

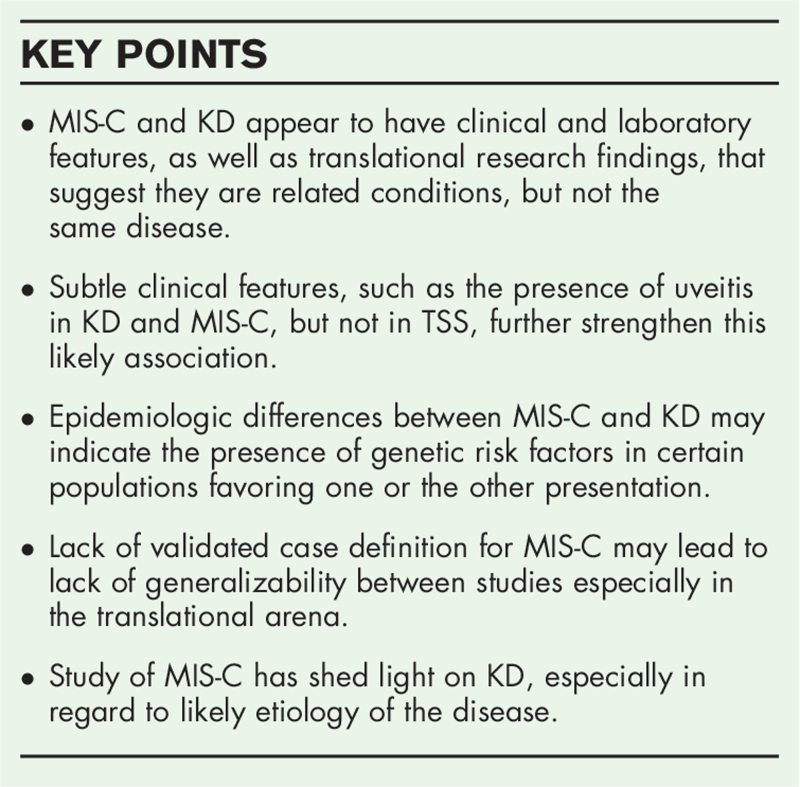

Multisystem Inflammatory Syndrome in Children (MIS-C) is a novel syndrome that has appeared in the wake of the severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus -2 pandemic, with features that overlap with Kawasaki disease (KD). As a result, new interest and focus have arisen in KD, and specifically mechanisms of the disease.

Recent findings

A major question in the literature on the nature of MIS-C is if, and how, it may be related to KD. This has been explored using component analysis type studies, as well as other unsupervised analysis, as well as direct comparisons. At present, the answer to this question remains opaque, and several studies have interpreted their findings in opposing ways. Studies seem to suggest some relationship, but that MIS-C and KD are not the same syndrome.

Summary

Study of MIS-C strengthens the likelihood that KD is a postinfectious immune response, and that perhaps multiple infectious agents or viruses underlie the disease. MIS-C and KD, while not the same disease, could plausibly be sibling disorders that fall under a larger syndrome of postacute autoimmune febrile responses to infection, along with Kawasaki shock syndrome.

Keywords: Kawasaki disease, Multisystem Inflammatory Syndrome in Children, toxic shock syndrome

INTRODUCTION

Multisystem Inflammatory Syndrome in Children (MIS-C) was first described as a ‘Kawasaki like’ illness in children, which occurred in a sudden spike of cases about 4 weeks after a major wave of severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus -2 (SARS-CoV-2) infection had passed through the general population [1]. Cases were initially described in multiple European centers, and following that in North America and internationally, and were then recognized as a distinct syndrome affecting children, temporally associated with SARS-CoV-2 infection [2]. Clinically, MIS-C is an acute febrile illness associated with either an apparent distributive shock, myocardial mechanical dysfunction, or both, as well as several cutaneous features including conjunctivitis, rash, and rash or edema of the distal extremities. The syndrome is also characterized as manifesting in some patients with peritonitis-like abdominal pain features and neurologic complications [2]. Although these presenting signs and symptoms appear nonspecific, MIS-C diagnosis recalls clinical features of Kawasaki disease (KD) when analyzed in comparison with febrile control patients [3–5].

This clinical similarity of MIS-C to KD has inevitably led to questions regarding whether the disease is closely related to KD itself, presenting in this instance as a response to SARS-CoV-2 infection, or whether it represents an entirely separate syndrome [6,7,8▪]. Several studies, which will be described in this review, included KD as a comparator group for study both in the clinical sphere as well as in more translational studies. The studies have in some cases led to novel findings regarding KD itself, as well as intriguing potential conclusions about the mechanisms underlying both diseases and their relationship.

Box 1.

no caption available

EPIDEMIOLOGIC INSIGHTS

MIS-C, unlike KD, has a very low incidence in east Asia. Although in some ways mirroring the SARS-CoV-2 global footprint, there were no reports of MIS-C during the first large wave in Wuhan, China, in which some 80,000 individuals were infected over a short period of time [9]. KD however has a distinctly higher incidence in east Asia as compared to Europe, North America or Africa [10,11]. Moreover, KD in North America maintains a predilection in terms both of severity and likely frequency for individuals of East Asian heritage [12]. MIS-C, conversely, may have increased incidence in black and Hispanic populations [13▪]. These differences in incidence between populations suggest a genetic risk factor may play a role in the pathogenesis of KD, and similarly, a genetic factor may play a role in MIS-C. For KD, several genetic variants, more commonly seen in east Asian populations, have been identified as potential genetic risk factors [14]. However, for MIS-C, as of the time of writing this review, no strong genetic factors have been identified, despite considerable effort of various groups to sequence many of these patients. (Very recent studies suggest a potential link to specific human leukocyte antigen (HLA)-1 subclasses [15▪▪].) Despite this, it is almost assured that as with KD, multiple risk alleles underlie MIS-C. Study of MIS-C however is confounded by the very broad set of clinical criteria and lack of validated case definition. This difficulty in identifying the precise MIS-C phenotype is likely to blame for lack of success in finding risk alleles, as cohorts may contain patients with fever but other diagnoses.

KD has long been known to have incidence affected by seasonality, and also appears to erupt sporadically in large ‘outbreaks’ [16]. Intriguingly, not only does the disease itself have this periodicity, but in addition response to therapy also is affected by season of the year [17,18]. If accepting the hypothesis that there is an underlying link between MIS-C and KD, all of this data together would suggest that KD itself is almost certainly induced by preceding viral infection, as opposed to other causes (such as a primary phenomenon or related to environmental factors [19]) and that these are likely to be multiple different viruses each of which is associated with variations in presentation and response to therapy.

KD is well known to have an increased incidence in children between 6 months and 5–6 years of age [20]. This contrasts significantly with the median age and distribution of MIS-C cases, with a median age of about 9 years, and a lack of peak age incidence [13▪]. This puzzle, at present without any solution, could when solved yield insights into the nature and etiology of KD. One potential consideration is that as they age, children are exposed and develop immunity to a number of viruses that could potentiate KD. By the time they reach preadolescence, they have effectively seen all of these viral agents. On the other hand, SARS-CoV-2 is a novel virus and therefore strikes all ages equally. Going forward, the natural history of SARS-CoV-2 (without a vaccine) could perhaps be primarily that of MIS-C in the younger age range (similar to KD) as opposed to an adult onset infectious syndrome.

CLINICAL SIMILARITIES

Prior to any discussion of the clinical/laboratory features of MIS-C, it is important to stress that no single diagnostic criteria for MIS-C has been defined, and this is a significant problem, because data and descriptive findings may not be generalizable between institutions. Certain groups have included patients without any past evidence of SARS-CoV-2 infection/serology in their patient groups with MIS-C [21▪,22▪▪], and others, using the WHO or CDC guidelines, also include patients neither meeting KD criteria nor having any end cardiac or other organ injury, but only persistent fever (and some of these patients may overlap with patients who do not have SARS-CoV-2 serology positivity) [13▪,21▪]. This may result in a ‘too broad’ catchment of MIS-C patients, and raises potential concerns. In certain series, for instance, laboratory features/cytokine concentrations of patients without positive serology clearly are different from their positive counterparts [22▪▪]. Are these patients without serology evidence of infection and clearly lower cytokine levels [22▪▪] truly MIS-C, or rather contemporaneous febrile controls? Are patients without evidence of mechanical cardiac dysfunction and elevated markers of cardiac stress/damage (ntBNP or troponin) [23▪▪] representative of MIS-C or another syndrome? This is important, because with no evidence of past SARS-CoV-2 infection and/or no evidence of end-organ dysfunction, management should be quite different. On the other hand, a reasonable counter-argument could be that there may be a rate of aneurysm development in ‘MIS-C’ patients not meeting KD criteria and not having acute end-organ damage that is being missed. In short, establishing a robust and validated MIS-C diagnostic criteria which captures true pathology is quite urgent. Once prevalence of SARS-CoV-2 declines, the positive predictive value of criteria with poor specificity will be very low.

Clinically, overlap between KD and MIS-C is such that a significant number of cases of MIS-C meet criteria for KD. In the largest report on these patients, a full 40% of these patients met criteria either for complete or incomplete KD [13▪]. These features however may also overlap with toxic shock syndrome (TSS) [24]. This has raised whether in fact MIS-C is a toxic shock phenomenon, and may be driven by a superantigen like motif that appears to be present on the S protein [25]. Some small clues hint that rather, MIS-C is a sibling disorder of KD, and less likely a TSS, with caveats. KD ocular findings are associated with anterior uveitis – inflammation of the anterior and chambers of the eye in nearly 90% of patients [26]. The same type of anterior uveitis is also seen in MIS-C (and not described as a common feature in TSS), and in one case series, was seen in all patients with MIS-C who had a slit lamp examination [27▪,28]. Findings such as abdominal pain (severe enough to warrant concern for appendicitis) and neurologic features which occur in a portion of patients with MIS-C, are also seen in severe KD and KD shock syndrome (KDSS; albeit also in TSS [24]); in one series, several patients with KD had surgery for presumed appendicitis [29–33]. Unusual features of MIS-C, such as severe cervical lymphadenitis (authors observation) sometimes mistaken for bacterial lymphadenitis or retropharyngeal abscess, have also been described in large series of patients in KD [34]. In short – MIS-C appears to look like KD about 40% of the time, and other symptoms more frequently seen in MIS-C are well described as atypical features of KD. Although there may be some overlap in broad strokes with TSS, detailed consideration of symptoms suggest that a KD like pathophysiology is more likely. Despite this, the caveat is that superantigen mediated disease is complex: guttate psoriasis, a condition that is characterized by focal skin lesions, is augmented by a superantigen process [35]. Thus, it could also be conceivable that a mixed process – both specific antigen mediated immunity and a superantigen process, is at play. A summary of epidemiologic and clinical differences between KD and MIS-C is presented in Table 1.

Table 1.

Epidemiologic and clinical contrasts between KD and MIS-C

| KD | MIS-C | |

| Locations of highest global incidence | Japan, East Asia | Western Europe, North America and South America |

| Racial and ethnic predominance | East Asian heritage | Hispanic and African heritage |

| Median age and age range | Median 3–4 yearsTypical range <6mo-6yExtended range 2mo-15y | Median 8–9 yearsRange 1yo-19yo |

| Typical clinical features | Fever; and including 3–5 of the following: Rash, Conjunctivitis, Mucositis, Extremity swelling/rash, lymphadenopathy | Fever, Shock and one of the following: Rash, abdominal pain, neurologic changes, conjunctivitis, lymphadenopathya |

| Uveitis | Common | Very common and pronouncedb |

| Shock | Rare but can occur in KD shock syndrome (5–10% of all KD) | At least 25–50% of cases |

| Seasonality of disease | Evident but not associated with a single infectious agent | Clear association with SARS-CoV-2 |

KD, Kawasaki disease; MIS-C, Multisystem Inflammatory Syndrome in Children; SARS, Severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus -2.

25–40% of MIS-C meets KD criteria.

Small case series; evidence limited.

LABORATORY DIFFERENCES

Laboratory features of MIS-C have been areas in which differences between KD and MIS-C appear to be laid most bare, but yet at the same time these yield very important clues to these syndromes. In particular, lymphopenia and thrombocytopenia are quite characteristic of essentially all patients with MIS-C (authors observation and [13▪]) and not described in typical KD [20]. Noteworthy here is the high similarity of laboratory features in one series to a comparator group with TSS [21▪]. This lymphopenia and thrombocytopenia may be important clues to the etiology of disease, with platelet consumption suggesting a microthombotic process, whereas lymphocytes may be homing to end organs. In typical KD, the platelet counts are markedly elevated as an acute phase reactant. KDSS, described only in 2009 [36], however, seems to have more closely approximately the findings in MIS-C, with patients in small series described to have lymphopenia and thrombocytopenia much more frequently than patients with KD [37]. KDSS, in the current paradigm of KD, is seen as a rare variation of an already relatively uncommon disease. In depth study of KDSS has not been possible due to its rarity. A recent more comprehensive review and comparison of KDSS and MIS-C shows several similarities, but yet still several differences [38]. Although KDSS is as frequently characterized by lymphopenia and thrombocytopenia than MIS-C, at the same time the degree of these changes are more pronounced in MIS-C, whereas the frequency of aneurysms is much less in MIS-C than in KDSS [38]. The authors conclude that MIS-C and KDSS are not the same entity, which appears to be a reasonable conclusion. What is perhaps also worth asking, based on this approach, is whether KD and KDSS are in fact the same entity – or whether perhaps they too are separate syndromes. Laboratory features are summarized in Table 2.

Table 2.

Laboratory contrasts between KD and MIS-C

| KD | MIS-C | |

| Lymphopenia | Rare unless in very severe cases or with shock (KD shock syndrome) | Essentially universal |

| Thrombocytopenia | Rare unless in very severe cases with shock; thrombocytosis is the rule | Very frequent |

| Abnormal ntBNP and troponin | Troponin very rare; ntBNP can be moderately elevated | Troponin elevations common; Markedly elevated and rapidly progressive ntBNP concentrations very common |

| Decreased Cardiac Mechanical function | Moderate frequency, typically mild | Common, can be severe |

| Hyponatremia | Frequent | Frequent |

| Aneurysms | 25% untreated, 5% in patients after treatment | Unknown frequency but appears to be 8–10% prior to therapy and very infrequent after therapy |

| Resolution of aneurysms | Via remodeling, can occur over 6 months to 1 year | Appears frequent and can resolve within 4–8 weeks |

KD, Kawasaki disease; MIS-C, Multisystem Inflammatory Syndrome in Children.

TRANSLATIONAL RESEARCH

A flurry of translational studies emerged in the months following the emergence of MIS-C, as many institutions and investigator groups sought to tackle the mission of etiology and mechanism of disease. Many of these studies have focused on immunologic phenotyping of cells in the peripheral circulation as a means of understanding the mechanisms of disease.

One of the first studies on this issue demonstrated activated T cells in the peripheral circulation, especially CD8+ non naïve T cells [39▪▪]. These CD8+ T cells also expressed higher levels of CX3CR1, which is a vascular endothelium honing receptor [39▪▪,40]. This finding would be consistent with a hypothesis, developing both from clinical observations and other studies, that injury to vascular endothelium, is a primary driver of the disease, and that CD8 T cells are a major player in pathophysiology. In support of this, elevated soluble C5b-9 was described in the plasma of patients with MIS-C, which is the activation product of the terminal complement cascade [41▪]. Although CX3CR1 upregulation has not been described in KD, it is notable that it has been described in Henoch-Schonlein purpura and granulomatosis with polyangiitis [42,43]. One would expect, as a vasculitis, this finding would likely be evident in KD as well, and perhaps speaks to the vascular inflammatory nature of MIS-C. A second cellular marker of interest was the finding of elevated CD64 on monocytes and neutrophils vs healthy controls which normalized during recovery [22▪▪]. This finding has also been described in KD, when comparing CD64 expression on monocytes and neutrophils to KD patients after intravenous immunoglobulin therapy [44].

In a more direct attempt to analyze the relationship between KD and MIS-C by the Brodin group (Stockholm), it was suggested that the hyperinflammatory state in MIS-C differed qualitatively from KD by principal component analysis of a large group of cytokines and chemokines from these patients [45▪▪]. Perhaps most intriguingly, the same group found a particular auto-antibody to Endoglin in MIS-C patients, a glycoprotein expressed in the endothelium, with a subset of KD patients also expressing this auto-antibody. Plasma Endoglin was also elevated in MIS-C patients, suggesting that the presence of the antibody may not be causal, but rather an effect of vascular damage [45▪▪]. A second group (Bogunovic, New York) performed a differential antibody analysis and found antibodies to anti-La, Anti-Jo-1, which are found in Lupus and Myositis syndromes, as well as a host of antibodies to inflammatory mediators, such as IL-6R. This group also found an IL-17 activation signal for MIS-C [46▪▪], as did a third group of investigators [22▪▪]. Another group described the finding of elevated CXCL-9 in patients with MIS-C [47], but did not perform comparisons to KD, whereas another group found CXCL-9 elevated in MIS-C vs KD [48]. Interferon gamma signal was also seen along with elevated GM-cerebrospinal fluid in MIS-C vs KD patients in another investigation [49]. The apparently contradictory data among groups may be either due to differences in case definition, or perhaps, typical of early laboratory-based investigation in which challenging assays on variable samples requires time to bring out signal from noise. The likely consideration is that both of these factors are playing a role.

Binding of serum antibodies to cardiac endothelial cells in culture was described as well in a recent investigation, however, the authors note that this could be either causal or an effect of vascular damage [50▪▪]. Finally, T cell receptor skewing either suggestive of superantigen [15▪▪,51▪], or perhaps a nonpeptide antigen [52]. This finding is potentially paradigm shifting, and may provide insights into the nature of both KD and MIS-C. Although superantigen as an etiology for KD was debated and finally discarded [53], the question should perhaps be raised again, given the finding that increased skewing was seen with increased severity of MIS-C [15▪▪]. With this, the question becomes whether T-cell skewing (if due to superantigen) was previously not consistently seen in KD because previous studies had variability in severity in their cohorts, and that it may be evident in KDSS. Having said this – the HLA-1 subclass association with MIS-C found by the same authors throws a wrench into the hypothesis, as it also requires a new process of superantigen/major histocompatibility complex (MHC) interaction, as these generally believed to be mediated via MHC-2, and not MHC-1 interactions [15▪▪]. Intriguingly, HLA subclass associations with KD, when described, have also been HLA-1 [54,55]. A non-comprehensive set of translational findings in KD vs MIS-C is described in Table 3.

Table 3.

Translational research findings in MIS-C and KD (all data is generally preliminary for MIS-C)

| KD | MIS-C | |

| Genetic associations | FCGR2A, CASP3, BLK, ITPKC, CD40, ORAI, HLA-B54:01 | HLA-A02, B35, C04 |

| Upregulated CD64 Monocytes/neutrophils | Present | Present |

| Upregulated T cell CX3CR1 | Unknown | Present |

| Cytokines upregulated | IFN-γ, CXCL9, IL-17, GM-CSF are potentially upregulated in MIS-C vs. KD | |

| Autoantibody presence | Variety of auto antibodies | Anti Endoglina |

| Superantigen mediated effect | Investigated but current data suggests no superantigen effect | Preliminary data suggests superantigen effect possible |

CSF, cerebrospinal fluid; HLA, human leukocyte antigen; KD, Kawasaki disease; MIS-C, Multisystem Inflammatory Syndrome in Children.

Single study.

CONCLUSION

MIS-C, since its emergence abruptly a mere 12–14 months ago, has captured the attention of the much of the medical and scientific community along with SARS-CoV-2 infection. With this, the clinical similarity to KD has also allowed investigation into KD an order of magnitude greater than the decades that preceded MIS-C. Clinically, both from an examination and laboratory point of view, and also from a translational research perspective, a relationship with KD seems almost too strong to dismiss. As a result of our experience with MIS-C, we now can say with much greater certainty – (1) that KD is an immunologic response to a preceding infection, likely viral; (2) that several viruses, and not a single virus, may induce this immunologic response; (3) that additional underlying genetic risk factors remain to be discovered for KD; (4) that activated CD8 T cells mediate the pathology of KD and perhaps (5) that KD itself is one of several diseases that would be classified together with MIS-C and KD shock as subtypes of a syndrome. These are all quite significant steps forward for a disease that, prior to 2020, was still regarded as a mystery in terms of etiology, mechanism and even classification within human disease.

Acknowledgements

None.

Financial support and sponsorship

This work was supported by the National Institutes of Health, grant # K-08 HL155033, AAAAI Faculty Development Award.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

REFERENCES AND RECOMMENDED READING

Papers of particular interest, published within the annual period of review, have been highlighted as:

▪ of special interest

▪▪ of outstanding interest

REFERENCES

- 1.Viner RM, Whittaker E. Kawasaki-like disease: emerging complication during the COVID-19 pandemic. Lancet 2020; 395:1741–1743. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bautista-Rodriguez C, Sanchez-de-Toledo J, Clark BC, et al. Multisystem inflammatory syndrome in children: an international survey. Pediatrics 2021; 147:e2020024554. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Carlin RF, Fischer AM, Pitkowsky Z, et al. Discriminating multisystem inflammatory syndrome in children requiring treatment from common febrile conditions in outpatient settings. J Pediatr 2021; 229:26–32 e22. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kelly MS, Fernandes ND, Carr AV, et al. Distinguishing features of patients evaluated for multisystem inflammatory syndrome in children. Pediatr Emerg Care 2021; 37:179–184. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Whittaker E, Bamford A, Kenny J, et al. Clinical characteristics of 58 children with a pediatric inflammatory multisystem syndrome temporally associated with SARS-CoV-2. J Am Med Assoc 2020; 324:259–269. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Rowley AH. Multisystem inflammatory syndrome in children and Kawasaki disease: two different illnesses with overlapping clinical features. J Pediatr 2020; 224:129–132. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.McCrindle BW, Manlhiot C. SARS-CoV-2-related inflammatory multisystem syndrome in children: different or shared etiology and pathophysiology as Kawasaki disease? JAMA 2020; 324:246–248. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8▪.Levin M. childhood multisystem inflammatory syndrome – a new challenge in the pandemic. N Engl J Med 2020; 383:393–395. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; insightful editorial and commentary on MIS-C at early stage of disease emergence

- 9.Xu S, Chen M, Weng J. COVID-19 and Kawasaki disease in children. Pharmacol Res 2020; 159:104951. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lin MT, Wu MH. The global epidemiology of Kawasaki disease: Review and future perspectives. Glob Cardiol Sci Pract 2017; 2017:e201720. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Singh S, Vignesh P, Burgner D. The epidemiology of Kawasaki disease: a global update. Arch Dis Child 2015; 100:1084–1088. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Holman RC, Belay ED, Christensen KY, et al. Hospitalizations for Kawasaki syndrome among children in the United States. Pediatr Infect Dis J 2010; 29:483–488. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13▪.Feldstein LR, Rose EB, Horwitz SM, et al. Multisystem inflammatory syndrome in US Children and Adolescents. N Engl J Med 2020; 383:334–346. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Largest US summary of patient characterisitcs and outcomes from 2020

- 14.Kumrah R, Vignesh P, Rawat A, et al. Immunogenetics of Kawasaki disease. Clin Rev Allergy Immunol 2020; 59:122–139. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15▪▪.Porritt RA, Paschold L, Noval Rivas M, et al. HLA class I-associated expansion of TRBV11-2 T cells in multisystem inflammatory syndrome in children. J Clin Investig 2021; 131:e146614. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; first description of HLA association with MIS-C

- 16.Burns JC, Cayan DR, Tong G, et al. Seasonality and temporal clustering of Kawasaki syndrome. Epidemiology 2005; 16:220–225. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kido S, Ae R, Kosami K, et al. Seasonality of i.v. immunoglobulin responsiveness in Kawasaki disease. Pediatr Int 2019; 61:539–543. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Shimizu D, Hoshina T, Kawamura M, et al. Seasonality in clinical courses of Kawasaki disease. Arch Dis Child 2019; 104:694–696. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ballester J, Borras S, Curcoll R, et al. On the interpretation of the atmospheric mechanism transporting the environmental trigger of Kawasaki Disease. PLoS One 2019; 14:e0226402. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.McCrindle BW, Rowley AH, Newburger JW, et al. Diagnosis, treatment, and long-term management of Kawasaki disease: a scientific statement for health professionals from the American Heart Association. Circulation 2017; 135:e927–e999. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21▪.Whittaker E, Bamford A, Kenny J, et al. Clinical characteristics of 58 children with a pediatric inflammatory multisystem syndrome temporally associated with SARS-CoV-2. JAMA 2020; 324:259–269. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Large study and one of earliest large cohorts of MIS-C from the United Kingdom, detailing multiple patients with aneurysms

- 22▪▪.Carter MJ, Fish M, Jennings A, et al. Peripheral immunophenotypes in children with multisystem inflammatory syndrome associated with SARS-CoV-2 infection. Nat Med 2020; 26:1701–1707. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Immunophenotyping study which proposes dysfunction in antigen presentation as part of the etiology of MIS-C

- 23▪▪.Lee PY, Day-Lewis M, Henderson LA, et al. Distinct clinical and immunological features of SARS-CoV-2-induced multisystem inflammatory syndrome in children. J Clin Investig 2020; 130:5942–5950. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Describes multiple patients from Boston with MIS-C and distinguishes from Kawasaki disease and macrophage activation syndrome

- 24.Tofte RW, Williams DN. Toxic shock syndrome. Evidence of a broad clinical spectrum. JAMA 1981; 246:2163–2167. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Noval Rivas M, Porritt RA, Cheng MH, et al. COVID-19-associated multisystem inflammatory syndrome in children (MIS-C): A novel disease that mimics toxic shock syndrome-the superantigen hypothesis. J Allergy Clin Immunol 2021; 147:57–59. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Burns JC, Joffe L, Sargent RA, et al. Anterior uveitis associated with Kawasaki syndrome. Pediatr Infect Dis 1985; 4:258–261. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27▪.Ozturk C, Yuce Sezen A, Savas Sen Z, et al. Bilateral acute anterior uveitis and corneal punctate epitheliopathy in children diagnosed with multisystem inflammatory syndrome secondary to COVID-19. Ocul Immunol Inflamm 2021; 1–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Case series which notes 5 patients with MIS-C with severe anterior uveitis

- 28.Karthika IK, Gulla KM, John J, et al. COVID-19 related multi-inflammatory syndrome presenting with uveitis – a case report. Indian J Ophthalmol 2021; 69:1319–1321. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Fabi M, Corinaldesi E, Pierantoni L, et al. Gastrointestinal presentation of Kawasaki disease: a red flag for severe disease? PLoS One 2018; 13:e0202658. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Colomba C, La Placa S, Saporito L, et al. Intestinal involvement in Kawasaki disease. J Pediatr 2018; 202:186–193. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Terasawa K, Ichinose E, Matsuishi T, et al. Neurological complications in Kawasaki disease. Brain Dev 1983; 5:371–374. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.McDonald D, Buttery J, Pike M. Neurological complications of Kawasaki disease. Arch Dis Child 1998; 79:200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Liu X, Zhou K, Hua Y, et al. Neurological involvement in Kawasaki disease: a retrospective study. Pediatr Rheumatol Online J 2020; 18:61. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Inagaki K, Blackshear C, Hobbs CV. Deep neck space involvement of Kawasaki disease in the US: a population-based study. J Pediatr 2019; 215:118–122. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Leung DY, Travers JB, Giorno R, et al. Evidence for a streptococcal superantigen-driven process in acute guttate psoriasis. J Clin Investig 1995; 96:2106–2112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Kanegaye JT, Wilder MS, Molkara D, et al. Recognition of a Kawasaki disease shock syndrome. Pediatrics 2009; 123:e783–e789. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Taddio A, Rossi ED, Monasta L, et al. Describing Kawasaki shock syndrome: results from a retrospective study and literature review. Clin Rheumatol 2017; 36:223–228. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Suzuki J, Abe K, Matsui T, et al. Kawasaki disease shock syndrome in japan and comparison with multisystem inflammatory syndrome in children in European countries. Front Pediatr 2021; 9:62545. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39▪▪.Vella LA, Giles JR, Baxter AE, et al. Deep immune profiling of MIS-C demonstrates marked but transient immune activation compared to adult and pediatric COVID-19. Sci Immunol 2021; 6:eabf7570. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Seminal and outstanding study on immune phenotypes with first description of CX3CR1 T cells as playing a role in disease

- 40.Mudd JC, Panigrahi S, Kyi B, et al. Inflammatory function of CX3CR1+ CD8+ T cells in treated HIV infection is modulated by platelet interactions. J Infect Dis 2016; 214:1808–1816. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41▪.Diorio C, Henrickson SE, Vella LA, et al. Multisystem inflammatory syndrome in children and COVID-19 are distinct presentations of SARS-CoV-2. J Clin Investig 2020; 130:5967–5975. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Analsysis of MIS-C vs. acute COVID-19 infection, describes differences between these entities

- 42.Imai T, Nishiyama K, Ueki K, et al. Involvement of activated cytotoxic T lymphocytes and natural killer cells in Henoch-Schonlein purpura nephritis. Clin Transl Immunol 2020; 9:e1212. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Bjerkeli V, Damas JK, Fevang B, et al. Increased expression of fractalkine (CX3CL1) and its receptor, CX3CR1, in Wegener's granulomatosis – possible role in vascular inflammation. Rheumatology 2007; 46:1422–1427. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Hokibara S, Kobayashi N, Kobayashi K, et al. Markedly elevated CD64 expression on neutrophils and monocytes as a biomarker for diagnosis and therapy assessment in Kawasaki disease. Inflamm Res 2016; 65:579–585. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45▪▪.Consiglio CR, Cotugno N, Sardh F, et al. The immunology of multisystem inflammatory syndrome in children with COVID-19. Cell 2020; 183:968–981. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Comprenehsive study on immune phenotypes in MIS-C and antibody responses as well proposals of auto-antibody for MIS-C

- 46▪▪.Gruber CN, Patel RS, Trachtman R, et al. Mapping systemic inflammation and antibody responses in multisystem inflammatory syndrome in children (MIS-C). Cell 2020; 183:982–995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; comprehensive immunologic phenotyping of MIS-C

- 47.Caldarale F, Giacomelli M, Garrafa E, et al. Plasmacytoid dendritic cells depletion and elevation of IFN-gamma dependent chemokines CXCL9 and CXCL10 in children with multisystem inflammatory syndrome. Front Immunol 2021; 12:654587. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Rodriguez-Smith JJ, Verweyen EL, Clay GM, et al. Inflammatory biomarkers in COVID-19-associated multisystem inflammatory syndrome in children, Kawasaki disease, and macrophage activation syndrome: a cohort study. Lancet Rheumatol 2021; [Online ahead of print]. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Esteve-Sole A, Anton J, Pino-Ramirez RM, et al. Similarities and differences between the immunopathogenesis of COVID-19-related pediatric multisystem inflammatory syndrome and Kawasaki disease. J Clin Investig 2021; 131:e144554. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50▪▪.Ramaswamy A, Brodsky NN, Sumida TS, et al. Immune dysregulation and autoreactivity correlate with disease severity in SARS-CoV-2-associated multisystem inflammatory syndrome in children. Immunity 2021; 54:1083–1095.e7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Describes finding of antibody binding to cardiac endothelial cells, enhanced CD8 and NK cell autoreactivity, and confirms TCR skewing.

- 51▪.Cheng MH, Zhang S, Porritt RA, et al. Superantigenic character of an insert unique to SARS-CoV-2 spike supported by skewed TCR repertoire in patients with hyperinflammation. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 2020; 117:25254–25262. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; First description of potential superantigenic character of spike protein and TCR skewing repertoire.

- 52.Guo T, Koo MY, Kagoya Y, et al. A subset of human autoreactive CD1c-restricted T cells preferentially expresses TRBV4-1(+) TCRs. J Immunol 2018; 200:500–511. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Leung DYM, Schlievert PM. Kawasaki syndrome: role of superantigens revisited. FEBS J 2021; 288:1771–1777. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Oh JH, Han JW, Lee SJ, et al. Polymorphisms of human leukocyte antigen genes in Korean children with Kawasaki disease. Pediatr Cardiol 2008; 29:402–408. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Kwon YC, Sim BK, Yu JJ, et al. HLA-B∗54:01 is associated with susceptibility to Kawasaki disease. Circ Genom Precis Med 2019; 12:e002365. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]