ABSTRACT

Dengue virus cocirculates globally as four serotypes (DENV1 to −4) that vary up to 40% at the amino acid level. Viral strains within a serotype further cluster into multiple genotypes. Eliciting a protective tetravalent neutralizing antibody response is a major goal of vaccine design, and efforts to characterize epitopes targeted by polyclonal mixtures of antibodies are ongoing. Previously, we identified two E protein residues (126 and 157) that defined the serotype-specific antibody response to DENV1 genotype 4 strain West Pac-74. DENV1 and DENV2 human vaccine sera neutralized DENV1 viruses incorporating these substitutions equivalently. In this study, we explored the contribution of these residues to the neutralization of DENV1 strains representing distinct genotypes. While neutralization of the genotype 1 strain TVP2130 was similarly impacted by mutation at E residues 126 and 157, mutation of these residues in the genotype 2 strain 16007 did not markedly change neutralization sensitivity, indicating the existence of additional DENV1 type-specific antibody targets. The accessibility of antibody epitopes can be strongly influenced by the conformational dynamics of virions and modified allosterically by amino acid variation. We found that changes at E domain II residue 204, shown previously to impact access to a poorly accessible E domain III epitope, impacted sensitivity of DENV1 16007 to neutralization by vaccine immune sera. Our data identify a role for minor sequence variation in changes to the antigenic structure that impacts antibody recognition by polyclonal immune sera. Understanding how the many structures sampled by flaviviruses influence antibody recognition will inform the design and evaluation of DENV immunogens.

IMPORTANCE Dengue virus (DENV) is an important human pathogen that cocirculates globally as four serotypes. Because sequential infection by different DENV serotypes is associated with more severe disease, eliciting a protective neutralizing antibody response against all four serotypes is a major goal of vaccine efforts. Here, we report that neutralization of DENV serotype 1 by polyclonal antibody is impacted by minor sequence variation among virus strains. Our data suggest that mechanisms that control neutralization sensitivity extend beyond variation within antibody epitopes but also include the influence of single amino acids on the ensemble of structural states sampled by structurally dynamic virions. A more detailed understanding of the antibody targets of DENV-specific polyclonal sera and factors that govern their access to antibody has important implications for flavivirus antigen design and evaluation.

KEYWORDS: dengue virus, humoral immunity, neutralizing antibody, polyclonal antibody, structural dynamics, vaccines

INTRODUCTION

Dengue virus (DENV) is a globally important human pathogen responsible for an estimated 105 million infections per year (1). It is predicted that 2.5 billion people live at risk of DENV infection due to the extensive geographical range of the Aedes mosquito vector responsible for virus transmission. While most DENV infections do not cause disease, clinical manifestations arising from infection with one of the four serotypes of DENV range from a mild febrile illness to potentially life-threatening complications, including plasma leakage and shock, severe bleeding, and organ involvement (referred to as severe dengue) (2). Because more severe disease manifestations are most frequently associated with secondary infections by a heterologous DENV serotype (3, 4), vaccine efforts are focused on a tetravalent platform that elicits neutralizing antibodies against all four DENV serotypes. A chimeric yellow fever virus (YFV)-DENV live attenuated tetravalent vaccine developed by Sanofi-Pasteur (CYD-TDV; Dengvaxia) was recently licensed (5). However, unequal protection was observed against the four serotypes in phase III human clinical trials (6–8). This vaccine is not recommended for children under the age of 9 due to evidence that it may predispose younger, seronegative recipients to severe disease upon subsequent DENV infection (7, 9, 10). Thus, the need to control primary DENV infections remains unmet. Two additional tetravalent live-attenuated candidates are currently in phase III clinical trials (NCT02406729 [NIAID] and NCT02747927 [Takeda]).

A member of the genus Flavivirus, DENV has an ∼11-kb single-stranded RNA genome that is translated as a single polyprotein and cleaved into three structural proteins (capsid [C], premembrane [prM], and envelope [E]) and at least seven nonstructural proteins (11). Noninfectious, immature virions bud into the endoplasmic reticulum (ER) and incorporate 180 copies of the E protein, arranged as 60 heterotrimeric spikes associated with an equal number of prM proteins (12, 13). As virus particles traffic through the trans-Golgi network, low-pH-induced structural rearrangements reveal a host-furin protease recognition site in prM, enabling cleavage. A short membrane-bound M protein remains associated with the virus, while the cleaved “pr” portion dissociates at neutral pH upon release from the cell (14, 15). The resulting mature flavivirus virions are smooth, spherical particles incorporating 90 sets of anti-parallel E homodimers arranged in a herringbone pattern (16, 17). Although prM cleavage is a required step in flavivirus maturation (18), the extent of cleavage necessary for the transition from a noninfectious immature virion to infectious virus is unknown (19).

Neutralizing antibodies with the capacity to inhibit DENV infection primarily target the E protein (20). The structure of the flavivirus E ectodomain is composed of three domains (EDI to -III) (21), each containing epitopes recognized by neutralizing antibodies (22, 23). Early studies with mouse-derived monoclonal antibodies (MAbs) identified a class of potent neutralizing antibodies that bind the EDIII lateral ridge epitope (24, 25). However, depletion of EDIII-specific antibodies from human sera revealed a minimal impact on neutralization capacity, indicating that the targets of the neutralizing antibody response likely differ between mice and humans (26, 27). Complex and quaternary epitopes that exist only in the context of the E protein dimer or intact mature virion have been identified (28). E dimer epitope (EDE) antibodies bind quaternary virus surfaces that include contacts on neighboring E proteins displayed on the outside of the virion (29). A growing body of evidence indicates that neutralizing antibodies elicited by humans against multiple flaviviruses, including DENV, YFV, Zika virus (ZIKV), and tick-borne encephalitis virus (TBEV), bind epitopes present only on E dimers, as opposed to monomers (29–33).

Serotype-specific (type-specific [TS]) neutralizing MAbs have been isolated from humans after DENV infection (29, 34–36). Although repertoire studies indicate that these antibodies represent only a minor proportion of the overall humoral response to DENV (29, 35, 36), TS antibodies elicited following primary infection are responsible for the majority of virus neutralization (34). Previously, using a panel of variant DENV1 reporter virus particles (RVPs), we identified two E protein residues (amino acids 126 and 157) that contribute significantly to the TS neutralizing antibody response to DENV1 vaccination (37). Sera from volunteers in monovalent DENV1 and DENV2 vaccine studies neutralized DENV1 variants incorporating E126K/E157K substitutions and DENV2 equivalently, indicating disruption of epitopes targeted by DENV1 TS neutralizing antibodies. Using sera from the same phase I DENV monovalent vaccine studies, a separate group subsequently demonstrated that antibodies responsible for vaccine-elicited TS neutralization target a complex EDI-EDII epitope that overlaps the footprint of the human MAb 1F4, which includes E residue 157 (38). Transplantation of the 1F4 epitope into DENV2 and DENV3 conferred neutralization sensitivity by DENV1 vaccine immune sera against the chimeric recombinant viruses (39).

Prior studies demonstrate that sequence variation among DENV strains impacts recognition by neutralizing antibodies (24, 40–45). Phylogenetic analyses reveal that within each DENV serotype, strains additionally cluster into genotypes that differ by up to 9% at the amino acid level (46). DENV1 strains can be divided into five genotypes that differ by ∼5% in their E protein amino acid sequences (47, 48). In the current study, we explored the contribution of E protein residues 126 and 157, identified as determinants of the TS neutralizing antibody response to DENV1 genotype 4 strain West Pac-74 (37), in the context of the genotype 1 strain TVP2130 and the genotype 2 strain 16007. Using sera from volunteers in a DENV1 monovalent vaccine trial, we found that neutralization of strain TVP2130 was similarly impacted by mutation at E residues 126 and 157, while mutation of these residues in strain 16007 did not markedly change neutralization sensitivity. Instead, we identified a critical contribution of E protein residue 204 to sensitivity to polyclonal vaccine sera. This residue was shown previously to control access to neutralizing antibody epitopes by modulating the ensemble of structures sampled by DENV1 (42) and may significantly impact the epitopes that contribute to TS patterns of neutralization by vaccine-elicited immune responses via an allosteric mechanism. Our results illustrate how minor sequence variation among related DENV strains influences polyclonal antibody recognition by modulating the conformational dynamics of the virus.

RESULTS

Impact of virus genotype on DENV-1 neutralization.

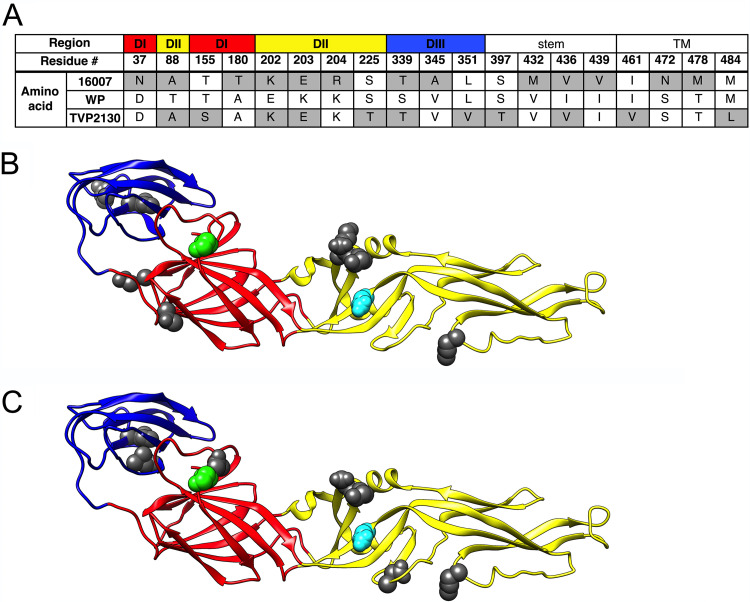

To investigate vaccine-elicited polyclonal antibody recognition of diverse DENV1 genotypes, we generated RVPs encoding the structural genes of the genotype 1 strain TVP2130, genotype 2 strain 16007 (42, 49) and genotype 4 strain West Pac-74 (WP-74) (37, 42, 50). The E proteins of these three strains vary by 2.2 to 2.8% at the amino acid level (WP-74 versus TVP2130, 11 differences; 16007 versus WP-74, 13 differences; 16007 versus TVP2130, 14 differences) (Fig. 1). E protein variation among these strains exists in all three structural domains, as well as the stem and transmembrane regions.

FIG 1.

Amino acid differences in the E proteins of DENV1 strains West Pac-74, 16007, and TVP2130. (A) Amino acids in the E protein of 16007 and TVP2130 that differ from the corresponding West Pac-74 residue are highlighted in gray. Location within the E protein ectodomain (DI, DII, and DIII) or the stem or transmembrane (TM) region is indicated. Numbering is in reference to the full-length 495-amino-acid E protein. (B and C) Ribbon diagrams of the crystal structure of DENV E ectodomain residues 1 to 394 (PDB code 1OAN) colored by domain: red, DI; yellow, DII; blue, DIII. Amino acid differences between (B) West Pac-74 and 16007 or (C) West Pac-74 and TVP2130 are highlighted in dark gray. Additionally, residues E126 and E157, previously identified as important contributors to type-specific (TS) polyclonal antibody recognition of the strain West Pac-74 (37), are highlighted in cyan and green, respectively. Ribbon diagrams were rendered in Chimera. WP, West Pac-74.

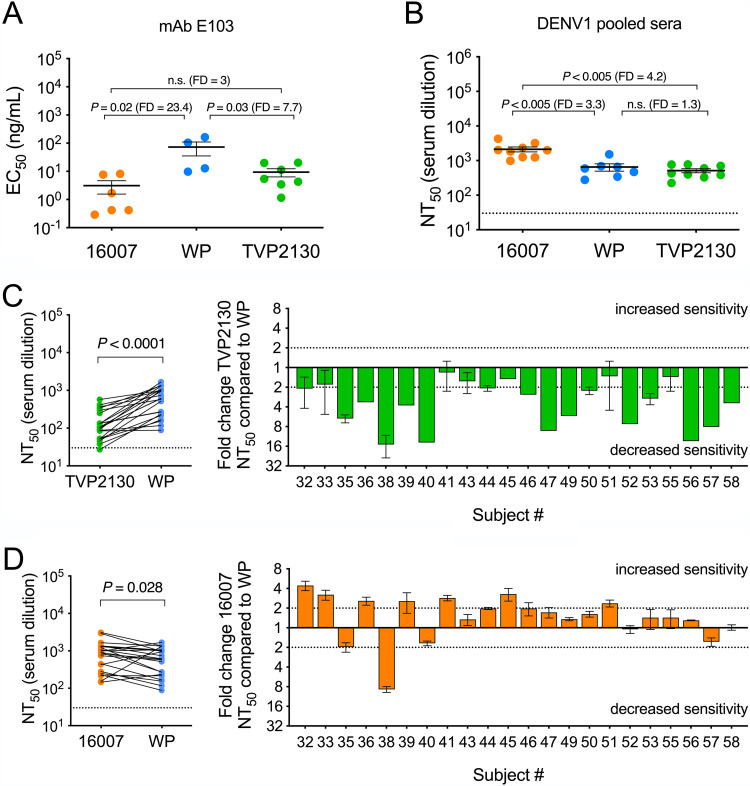

Genotype-dependent patterns of DENV neutralization have been observed previously (24, 41, 43–45). Here, we explored the sensitivity of RVPs produced with DENV1 strains 16007, TVP2130, and WP-74 to neutralization by TS monoclonal and polyclonal antibody (Fig. 2A and B). Experiments with the EDIII TS MAb E103 revealed a hierarchy of neutralization sensitivity wherein DENV1 16007 was most susceptible to inhibition (mean 50% effective concentrations [EC50s] of 3, 73, and 9 ng/ml for 16007, WP-74, and TVP2130, respectively) (Fig. 2A), consistent with a previous study of strains 16007 and WP-74 only (24). Using polyclonal sera pooled from recipients of a DENV1 monovalent vaccine candidate (51, 52), we found that strain 16007 was significantly more susceptible to neutralization than TVP2130 and WP-74 (mean 50% neutralizing titers [NT50s] of 2131, 652, and 512 for strains 16007, WP-74, and TVP2130, respectively) (Fig. 2B). The 3.3-fold increase in 16007 NT50 relative to that of strain WP-74 was a surprising finding, because immunity was elicited by a vaccine encoding a WP-74 E protein antigen. Next, individual serum samples from 22 study subjects, collected 222 days postvaccination, were tested in parallel for an ability to inhibit infectivity of homologous (WP-74) and heterologous (TVP2130 or 16007) strains (Fig. 2C and D) (53). Group mean reciprocal serum NT50s of 977, 695, and 164 were observed for strains 16007, WP-74, and TVP2130, respectively. In agreement with studies of pooled samples, sera from the majority of samples (16 of 22) more efficiently neutralized 16007 than WP-74 (Fig. 2D). All sera exhibited a reduced capacity to neutralize the heterologous strain TVP2130, albeit to differing degrees (Fig. 2C).

FIG 2.

Neutralization potency of DENV1-immune vaccine sera against DENV1 strains TVP2130, 16007, and West Pac-74. The indicated RVPs were tested for neutralization sensitivity by the DENV1 TS MAb E103 (A) or polyclonal DENV-1 immune vaccine sera (B to D). (A) EC50s from 4 to 7 independent experiments per RVP are shown for the E protein-specific MAb E103. (B) NT50s from 7 to 9 independent experiments per RVP are shown for pooled sera collected from recipients of a DENV1 monovalent vaccine candidate. Black horizontal lines and error bars denote means and standard errors, respectively. The dotted line in panel B denotes the limit of detection for serum neutralization, a reciprocal titer of 30. Mean EC50s and NT50s in each panel were compared using a one-way ANOVA, and the multiplicity-adjusted P values are reported. n.s., not significant (P > 0.05). FD, fold difference in mean EC50s or NT50s. (C and D) The ability of serum samples obtained 222 days following monovalent DENV1 West Pac-74 vaccination from 22 volunteers to inhibit infection of the indicated DENV1 RVPs was assessed. Shown are NT50s for each of the 22 serum samples from volunteers against virus strains (C) West Pac-74 and TVP2130 or (D) West Pac-74 and 16007. In the left panels, each data point represents the individual or mean value from 1 to 3 independent pairwise experiments. Solid lines connect NT50s for the same sample measured against the indicated virus strains. The dotted line denotes the limit of detection for the assay, a reciprocal serum titer of 30. NT50s were compared using a Wilcoxon matched-pairs signed-rank test. In the right panels, the fold change in NT50s for each of the 22 serum samples compared to West Pac-74 is shown. Bars denote individual or mean values for each serum sample; error bars represent standard errors of the means. Dotted lines denoting a 2-fold increase and decrease in NT50 are shown as a reference. WP, West Pac-74.

E protein mutations E126K and E157K impact the sensitivity of DENV1 strain TVP2130 but not strain 16007 to neutralization by DENV1 vaccine sera.

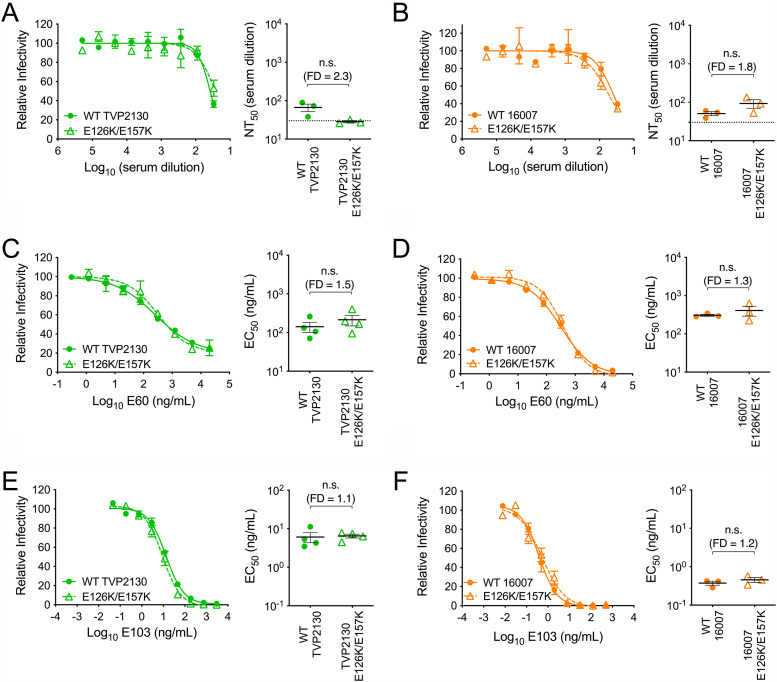

We previously demonstrated that two E protein residues, located at positions 126 and 157, contributed significantly to the binding of TS antibodies elicited by the DENV1 WP-74 monovalent vaccine candidate (Fig. 1B and C) (37). Mutating both residues from glutamic acid (E) to the lysine (K) residues found at the corresponding sites in DENV2 ablated the TS antibody response to DENV1 monovalent vaccine immune sera. E126 and E157 are highly conserved among DENV1 viruses, including strains TVP2130 and 16007 (of 1,688 distinct human-derived DENV1 genomes downloaded from the NCBI Virus Variation resource, only one and three sequences encoded a residue other than E at positions 126 and 157, respectively; none of the alternate residues was a K) (54). To test whether these two residues are important TS antibody targets on other DENV1 genotype strains, we produced E126K/E157K RVP variants of 16007 and TVP2130. To ensure that these mutations did not change the overall antigenicity of the E protein, E126K/E157K variants were characterized for sensitivity to neutralization by a panel of control MAbs and polyclonal sera used in prior studies of WP-74 (Fig. 3) (37). Neutralization sensitivity of the double mutant and the parent was not significantly different when assayed with pooled DENV2-immune vaccine sera, the cross-reactive EDII fusion loop-specific MAb E60, or the DENV1 TS MAb E103. These data indicated that the introduction of these two substitutions into strains TVP2130 or 16007 does not significantly alter the overall antigenicity of the virion.

FIG 3.

Characterization of DENV1 E126K/E157K variants. The neutralization sensitivity of wild-type and E126K/E157K variant strains of TVP2130 and 16007 RVPs to cross-reactive DENV2-immune pooled vaccine sera (A and B), the cross-reactive EDII fusion loop-specific MAb E60 (C and D), and the TS EDIII MAb E103 (E and F) was assessed. Within each panel, representative dose response curves are shown on the left; error bars represent the range for duplicate infections. Mean EC50s or NT50s from 3 or 4 independent experiments are shown on the right; horizontal lines and error bars represent means and standard errors. n.s., not significant (P > 0.05). In the right portions of panels A and B, the dotted line denotes the limit of detection for serum neutralization, a reciprocal serum titer of 30. EC50s and NT50s were compared using a Wilcoxon matched-pairs signed-rank test. FD, fold difference in mean EC50 or NT50s; WT, wild type.

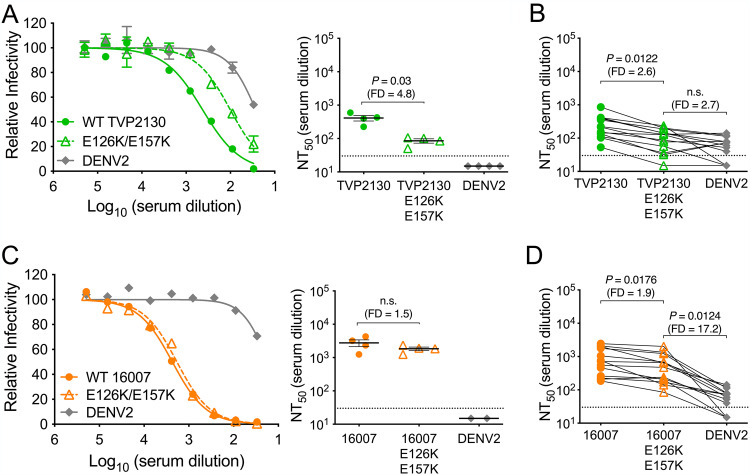

We next performed neutralization studies to assess the sensitivity of TVP2130 or 16007 E126K/E157K variant RVPs to neutralization by pooled and individual monovalent DENV1-immune vaccine sera (Fig. 4). Similar to our previous studies with WP-74 (37), substitutions at E residues 126 and 157 resulted in a reduction of DENV1 TS neutralization by pooled DENV1 sera for strain TVP2130 (4.8-fold difference between wild-type and E126K/E157K NT50s; P = 0.03) (Fig. 4A). Similar patterns were observed when neutralization studies were performed with a panel of 13 individual DENV1 monovalent vaccine serum samples (Fig. 4B). E126K/E157K substitution in TVP2130 decreased neutralization sensitivity to levels similar in magnitude to those of DENV2 (average 2.7-fold difference between paired TVP2130 E126K/E157K and DENV2 NT50s; P > 0.05). In contrast, 16007 wild-type and E126K/E157K RVPs were similarly sensitive to neutralization by the pooled DENV1-immune sera (1.5-fold difference in NT50s; P > 0.05) (Fig. 4C) and by individual DENV-1 monovalent vaccine-immune sera (average 17.2-fold difference between paired 16007 E126K/E157K and DENV2 NT50s; P = 0.0124) (Fig. 4D). Thus, the importance of residues E126 and E157 in defining the TS antibody response does not extend across all DENV1 strains.

FIG 4.

Effect of mutations E126K/E157K on the sensitivity of DENV1 strains TVP2130 and 16007 to neutralization by DENV1-immune sera. Wild-type and E126K/E157K variant RVPs representing DENV1 strains TVP2130 (A and B) and 16007 (C and D) were tested for sensitivity to neutralization by sera pooled (A and C) or from individual recipients (B and D) of a DENV1 monovalent vaccine candidate. DENV2 RVPs were included as a control for the cross-reactive serum component. (A and C) (Left) Representative dose-response curves with pooled vaccine sera; error bars represent the range of duplicate infections. (Right) NT50s from 2 to 4 independent experiments per RVP; the horizontal lines and error bars represent means and standard errors. NT50s were compared using a Wilcoxon matched-pairs signed-rank test. (B and D) The indicated RVPs were tested in parallel for sensitivity to neutralization by sera from 13 volunteers that received a DENV1 strain West Pac-74 monovalent vaccine candidate. NT50 reciprocal serum titers from a single experiment are shown. Solid lines connect titers for the same serum sample against the indicated RVPs. NT50s were compared using a one-way ANOVA with Tukey’s multiple-comparison correction. The dotted line denotes the limit of detection for serum neutralization, a reciprocal serum titer of 30; negative samples were reported as one-half the limit of detection, i.e., a titer of 15. n.s., not significant (P > 0.05). FD, fold difference in mean NT50s (A and C) or the average of the fold difference in NT50s for individual samples (B and D). WT, wild type.

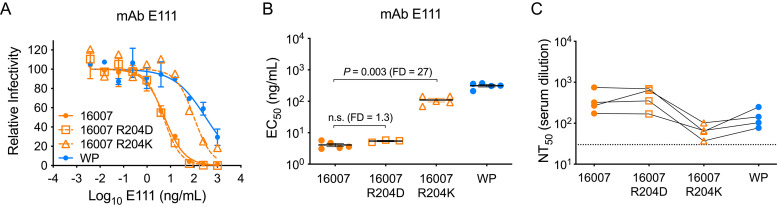

E protein residue 204 impacts the sensitivity of strain 16007 to neutralization by DENV1-immune sera.

Sequence variation among strains has been shown to impact recognition by neutralizing antibodies for all four DENV serotypes (24, 40–45). We have demonstrated that E residues 126 and 157 contribute energetically to the binding of vaccine-elicited TS antibodies against strains WP-74 and TVP2130, but not strain 16007, despite high sequence similarity among these viruses (Fig. 4) (37). Curiously, strain 16007 displayed an unexpectedly greater sensitivity to sera collected following vaccination with the heterologous WP-74 monovalent candidate (Fig. 2B and D). In a prior study comparing strains 16007 and WP-74, natural strain variation had a significant allosteric impact on neutralization by the EDIII-specific MAb E111 (42). An ∼200-fold difference in MAb E111 neutralization sensitivity was mapped to the presence of a lysine (K; WP-74) or arginine (R; 16007) at residue 204 in EDII, located at a substantial distance from the structurally defined epitope of this MAb (24, 40, 42). Taking these data together with time-dependent patterns of neutralization and virion stability data, these studies concluded that residue 204 modulated the structural ensemble sampled by the virus.

Therefore, we explored a role for E residue 204 in the increased sensitivity of 16007 to neutralization by vaccine sera and the E126/E157-independent pattern of TS recognition by this strain. To complement studies with 16007 RVPs incorporating the R204K substitution, we introduced a chemically nonconservative aspartic acid (D) substitution at 16007 E residue 204 expected to disrupt direct antibody-epitope interactions if this residue was directly involved in binding energetics. As a control, we demonstrated that 16007 R204D and wild-type 16007 RVPs were equally sensitive to neutralization by MAb E111 (Fig. 5A and B). We next tested the 16007 R204D and R204K RVP variants for sensitivity to neutralization by four DENV1-immune vaccine sera that neutralized strain 16007 more potently than WP-74 (Fig. 5C). 16007 R204K RVPs were less sensitive to neutralization than 16007 and were inhibited at titers comparable to those of WP-74, which also encodes a K at position 204. In contrast, 16007 R204D RVPs were neutralized at titers equivalent to those of the parental control.

FIG 5.

Impact of E protein residue 204 on neutralization of DENV1 strain 16007. RVPs representing wild-type West Pac-74, wild type 16007, and 16007 variants incorporating E protein substitutions R204D and R204K were assessed for neutralization by the EDIII MAb E111 (A and B) and polyclonal DENV1 vaccine immune sera (C). (A) A representative dose response curve is shown for MAb E111. Error bars represent the range of duplicate infections. (B) EC50s from 3 to 5 independent experiments are shown. Horizontal lines denote means; error bars represent standard errors of the means. EC50s were compared using a one-way ANOVA with Tukey’s multiple comparisons correction. n.s., not significant (P > 0.05). (C) Sera from four DENV1 vaccine recipients were analyzed for neutralization potency against DENV1 strains West Pac-74, 16007, and 16007 variants R204K and R204D. Each dot represents the average NT50 from three independent experiments for an individual serum sample. Solid lines connect titers for the same serum sample against the indicated RVPs. The dotted line denotes the limit of detection for serum neutralization, i.e., a reciprocal serum titer of 30. FD, fold difference in mean EC50s. WP, West Pac-74.

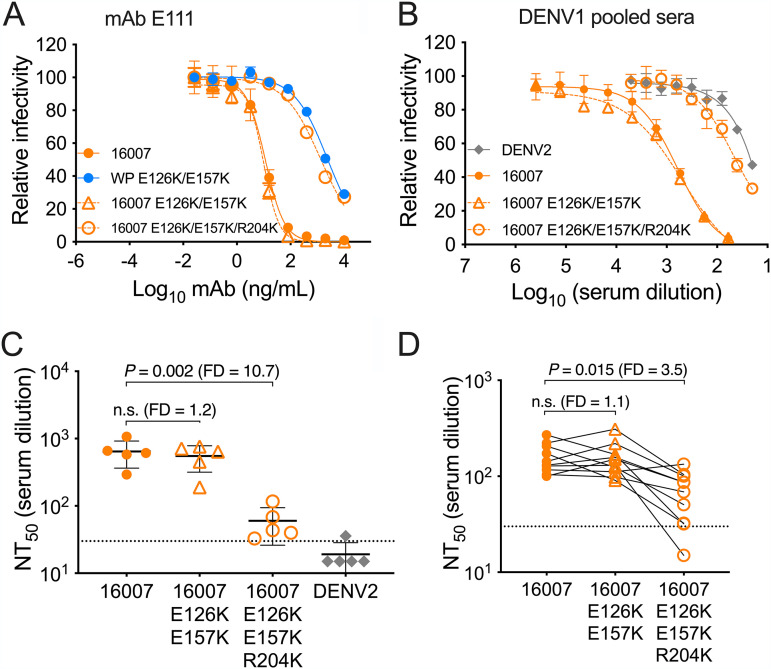

Variation at E residue 204 alters the DENV1 TS response directed at residues E126 and E157.

Our results indicate that mutation of E residue 204 in strain 16007 from R to K changes the structural ensemble of the virus to enable recognition by MAbs and polyclonal sera in a manner similar to that of WP-74 (Fig. 5). Since TS neutralization of DENV1 vaccine sera was minimally impacted by incorporation of E126K/E157K mutations in the context of wild-type 16007 (Fig. 4C and D), we investigated whether the further addition of the R204K substitution (creating 16007 E126K/E157K/R204K RVPs) would reduce TS neutralization in a pattern similar to that observed when the E126K/E157K mutations were incorporated into strains WP-74 and TVP2130 (Fig. 4A and B) (37). Control neutralization experiments revealed that 16007 E126K/E157K/R204K and WP-74 E126K/E157K RVPs were similarly sensitive to MAb E111 (Fig. 6A). Of interest, 16007 E126K/E157K/R204K RVPs were considerably less sensitive to neutralization by pooled DENV1 vaccine sera than wild-type 16007 or the E126K/E157K double mutant (average NT50s of 643, 551 and 60 for 16007 wild type, E126K/E157K, and E126K/E157K/R204K, respectively) (Fig. 6B and C). The similar titers achieved with the triple mutant and DENV2 RVPs revealed that these three residues are sufficient to largely eliminate the TS response to DENV1 vaccine-immune sera. The same pattern was observed when we assessed neutralization of 16007 wild type, E126K/E157K, and E126K/E157K/R204K variants by individual immune serum samples. For this screen, we selected 10 of the 22 serum samples studied in Fig. 3 for which sufficient volumes were available for study (Fig. 6D). These studies revealed a robust TS neutralizing antibody response that was unaffected by the incorporation of the E126K and E157K substitutions alone (average 1.1-fold difference in 16007 E127K/E157K NT50s compared to that of wild-type 16007; P > 0.05). However, in most subjects, further incorporation of R204K resulted in decreased TS neutralization sensitivity (average 3.5-fold difference in 16007 E126K/E157K/R204K NT50 compared to that of wild-type 16007; P = 0.015). These results indicate that the presence of an arginine at E residue 204 in strain 16007 governs the importance of the polyclonal response directed against residues E126 and E157.

FIG 6.

Sensitivity of DENV1 16007 variants to neutralization by DENV1-immune sera. The indicated RVPs were assessed for neutralization by (A) MAb E111 or sera (B to D) that were pooled (B and C) or were from individual recipients of a DENV1 monovalent vaccine candidate (D). (A) Dose-response curves from a single experiment with MAb E111. Error bars represent the range for duplicate infections. (B) Representative dose response curves for pooled DENV1 immune sera against the indicated RVPs. Error bars represent the range for duplicate infections. (C) NT50s from 4 independent experiments with pooled DENV1 immune sera. Horizontal lines denote means; error bars represent standard errors of the means. (D) DENV1 16007 wild-type and variant RVPs were tested in parallel for sensitivity to neutralization by sera from 10 volunteers that received a DENV1 strain West Pac-74 monovalent vaccine candidate. NT50 reciprocal serum titers from a single experiment are shown. Solid lines connect titers for the same serum sample against the indicated RVPs. In panels C and D, NT50s were compared among the 16007 variants using a one-way ANOVA with Tukey’s multiple-comparison correction. n.s., not significant (P > 0.05). The dotted line denotes the limit of detection for serum neutralization, a reciprocal serum titer of 30; negative samples were reported as one-half the limit of detection, i.e., a titer of 15. FD, fold difference in mean NT50s (C), or the average of the fold difference in NT50s for individual samples (D). WP, West Pac-74.

DISCUSSION

MAb epitope mapping studies have extended an understanding of the structural states of infectious flaviviruses. Antibodies may bind epitopes comprising E protein residues contained within a single E protein monomer (28, 55). Complex epitopes composed of the amino acids of adjacent E protein subunits have also been described (28, 29) and shown to contribute significantly to the neutralizing activity of serum antibodies elicited by DENV, YFV, ZIKV, and TBEV infection (29–33). Paradoxically, some neutralizing antibodies engage E protein epitopes predicted to be inaccessible for antibody recognition on the mature virion structure (40, 42, 56–58). How neutralizing antibodies bind poorly accessible epitopes on infectious virions in numbers sufficient to neutralize infection remains incompletely understood. For some antibodies, this structure-function discrepancy can be explained by the retention of prM-E heterotrimers on virus particles due to incomplete virion maturation. Incomplete prM cleavage increases the accessibility of otherwise cryptic E protein epitopes on infectious partially mature virions (49, 59–62). However, prior work has shown that the TS neutralizing activity of the DENV1 monovalent sera studied here is largely insensitive to the maturation state of the virion (37). The conformational dynamics of viral structural proteins (known as “viral breathing”) also provides a mechanism to expose otherwise inaccessible surfaces of virions (63).

The existing high-resolution structures of flaviviruses do not capture the entirety of the virion structural ensemble. For example, the DENV1 TS MAb E111 binds an epitope that is not displayed on the surface of mature or immature forms of the virion, yet it potently neutralized infection in vitro (24, 40, 42) and provided nearly complete protection in vivo when administered to AG129 mice 1 day prior to infection with the DENV1 strain WP-74 (24). Structural studies of some DENV2 strains incubated at physiological temperature revealed more than one structural form of the virion (64, 65). Mutagenesis studies have identified E protein residues hypothesized to influence these structural transitions (66). The existence of an ensemble of structural states at equilibrium is also suggested by time- and temperature-dependent patterns of neutralization observed with most flavivirus antibodies (49, 67). Amino acid changes that alter the ensemble of states sampled by virions may change the antigenic surface of the virion, thereby defining epitope exposure via an allosteric mechanism. In a prior study, the presence of lysine (WP-74) or arginine (16007) at E residue 204 was responsible for large differences in sensitivity to neutralization by antibodies that bind the poorly accessible EDIII CC’ loop, including MAb E111 (40, 42).

Here, we explored the recognition of DENV1 by TS antibodies elicited by a monovalent live-attenuated DENV1 vaccine candidate. We previously identified two amino acids that contributed significantly to the binding of vaccine-elicited DENV1 TS antibodies (37). Substitution of amino acids at E protein residues 126 and 157 of DENV1 WP-74 to the corresponding residues of DENV2 (E to K in both instances) largely eliminated the TS neutralization of WP-74 RVPs by homologous DENV1 vaccine-immune sera. These data suggested a relatively small number of epitopes define TS recognition of DENV1. In agreement, a subsequent study of this vaccine-immune sera found that TS recognition was mediated by neutralizing antibodies targeting a complex epitope in EDI-EDII that includes E residue 157 (38, 39). Genotypic differences have been reported for all four DENV serotypes with the potential to impact antibody recognition (24, 40–45). It remained unclear if E residues 126 and 157 would also contribute energetically to the binding of other DENV1 viruses by neutralizing antibodies in vaccine-immune sera. Introduction of the E126K/E157K mutations into the genotype 1 strain TVP2130 resulted in a similar decrease in TS neutralization by polyclonal vaccine sera, as anticipated from strains with such a high degree of sequence similarity, supporting a role for these amino acids in TS patterns of recognition of DENV1 (37).

Two distinct characteristics of the patterns of genotype 2 strain 16007 neutralization sensitivity were of interest. First, 16007 was considerably more sensitive to neutralization by sera from monovalent DENV1 vaccine recipients than the vaccine-matched strain WP-74, consistent with prior studies using MAbs (24, 40, 42). In addition, the introduction of E126K/E157K substitutions into the 16007 E protein did not reduce sensitivity to neutralization by monovalent vaccine-immune sera, unlike studies with WP-74 or TVP2130. These data suggested the involvement of additional epitopes in 16007 that do not make significant contributions to TS recognition of these other DENV1 strains. Eleven amino acids differ between WP-74 and 16007 DENV1 strains with the potential to contribute to the energetics of antibody binding. Because E residue 204 impacts the antigenic structure of DENV1 allosterically (42), we hypothesized that the structural ensemble associated with an arginine at this position presents new surfaces available for TS recognition of this genotype 2 strain. In support, we discovered that the sensitivity of 16007 to neutralization by DENV1 vaccine-immune sera was impacted by E residue 204; a 16007 R204K variant and wild-type WP-74 were similarly sensitive to neutralization. The introduction of a chemically nonconservative amino acid change (R204D) had no impact on the sensitivity of 16007 to neutralization by polyclonal antibody, suggesting that this residue does not contribute directly to the energetics of TS polyclonal antibody binding. The introduction of the E126K/E157K double mutant into the 16007 R204K backbone reduced TS neutralization by polyclonal vaccine sera, as observed with the WP-74 double mutant.

These studies indicate that the contributions of individual epitopes to neutralization activity in polyclonal sera may be shaped by amino acid variation at sites outside epitope-paratope interactions. Our data identified a single amino acid change (R204K) that toggles the relative importance of two amino acids (E126 and E157) that are critical for TS recognition of DENV1 16007. How a single conservative amino acid substitution changes the antigenic surface of a virion is unknown. Ongoing structural studies may reveal how some substitutions at this residue stabilize a unique antigenic conformation of the E protein herringbone that decorates the surface of the virion.

Our results confirm the importance of a small number of E protein amino acids for TS recognition by vaccine-immune polyclonal antibody and extend prior studies of the molecular basis of TS recognition of DENV1 to other genotypes (37). More importantly, our data highlight the potential for amino acid variation at positions outside known epitopes to define neutralization sensitivity. The 16007 DENV1 strain included in these studies is no longer in circulation and was found to cluster separately from other DENV1 strains in an antigenic cartography study of DENV neutralizing antibody responses, consistent with a distinct structural ensemble (68). Indeed, the presence of a lysine (K) at E residue 204 is overwhelmingly conserved in DENV1 strains (of 1,688 distinct human-derived DENV1 genomes downloaded from the NCBI Virus Variation resource, only three sequences varied at this position, each encoding an R) (54). These three sequences were isolated following travel to Thailand and Venezuela in 2008 (69) and from a dengue outbreak in Key West, FL, in 2010 (70), suggesting that the presence of an R at residue 204 does exist in nature, albeit rarely. Nonetheless, strain 16007 is a commonly used laboratory strain representative of DENV1 and serves as the DENV1 component of a tetravalent vaccine currently undergoing clinical studies (NCT02747927 [Takeda]). Our results underscore the importance of careful study of antigenic variation in both antigen design and the tools used to evaluate vaccine-elicited immune responses for flavivirus vaccines. We hypothesize that many E protein residues may similarly have the potential to influence virion structure. Mutations in the E protein that alter the accessibility of otherwise cryptic antibody epitopes have been identified in other flavivirus contexts (71). Ongoing efforts in our laboratory aim to expand our understanding of how these and other yet-to-be-identified mutations impact virion structure and stability. Understanding how minor sequence variation can impact the antibody response generated during infection and vaccination, as well as in the context of diagnostic assays, will aid in future vaccine design and implementation.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Ethics statement.

Clinical studies were conducted at the Center for Immunization at the Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health under an investigational new drug application reviewed by the United States Food and Drug Administration. The clinical protocol and consent form were reviewed and approved by the NIAID Regulatory Compliance and Human Subjects Protection Branch, the NIAID Data Safety Monitoring Board, the Western Institutional Review Board, and the Johns Hopkins University Institutional Biosafety Committee (ClinicalTrials.gov identifiers NCT00473135 and NCT00920517). Written informed consent was obtained from each participant in accordance with the Code of Federal Regulations (21 CFR 50) and International Conference on Harmonisation guidelines for Good Clinical Practice (ICH E6).

DENV immune sera.

Sera from flavivirus-naive recipients of phase I studies of candidate live attenuated DENV1 or DENV2 monovalent vaccines were obtained for study. Pooled serum samples were from two (DENV1) or three (DENV2) vaccine recipients and were collected 2 to 3 years postvaccination (37, 51, 72). The individual serum samples from 22 recipients of a DENV1 vaccine were collected on day 222 postvaccination (53). The DENV1 and DENV2 vaccines contain the prM-E structural genes from strains West Pac-74 and New Guinea C, respectively.

Cell lines.

Cells were maintained at 37°C and 7% CO2. HEK-293T cells were passaged in complete Dulbecco’s modified Eagle medium (DMEM) containing Glutamax (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA) and supplemented with 7% fetal bovine serum (FBS) (HyClone, Logan, UT) and 100 U/ml penicillin-streptomycin (PS) (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA). Raji cells expressing the flavivirus attachment factor DC-SIGNR (Raji-DCSIGNR) were passaged in RPMI 1640 medium containing Glutamax (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA), and supplemented with 7% FBS and 100 U/ml PS.

DENV1 virus history.

The genotype 1 strain TVP2130 was isolated from an infected patient in Taiwan in 1988 and passaged three times on mosquito cell culture (available from the World Reference Center for Emerging Viruses and Arboviruses). The now extinct genotype 2 strain 16007 was originally recovered from a patient with severe dengue in Thailand in 1964, followed by extensive passage in cell culture (20, 73). The genotype 4 strain West Pac-74 was isolated from a patient with a mild case of dengue fever on Nauru Island in 1974 (74). 16007 and West Pac-74 are the DENV1 components of the Takeda and NIAID tetravalent vaccine candidates currently in phase III clinical trials, respectively.

Plasmids.

Plasmids carrying a West Nile virus (WNV) subgenomic replicon (pWNVII-Rep-GFP/Zeo) and the structural genes of DENV1 genotype 4 strain West Pac-74, DENV1 genotype 2 strain 16007, and DENV2 strain New Guinea C have been described previously (37, 49, 50, 67, 75, 76). For the construction of a plasmid carrying the structural genes of DENV1 genotype 1 strain TVP2130, the structural genes were obtained from virus in the laboratory of Michael Diamond (Washington University School of Medicine, St. Louis, MO) (24) through reverse transcription-PCR (RT-PCR) and cloned into the expression vector pcDNA6.2 (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA). Sequencing results matched the CprME protein sequence of GenBank entry BAN63086.1. CprME variants were produced by site-directed mutagenesis using the QuikChange mutagenesis kit (Agilent Technologies, Santa Clara, CA) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. All plasmids used in this study were propagated in Stbl2 bacteria grown at 30°C (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA) and sequenced before use.

RVP production.

DENV reporter virus particles (RVPs) capable of a single round of infection were produced by complementation of a WNV subgenomic replicon with plasmids encoding the structural genes of DENV as described previously (37, 50, 67). Briefly, preplated HEK-293T cells were transfected with pWNVII-Rep-GFP/Zeo replicon and DENV CprME plasmids in a 1:3 ratio by mass, using Lipofectamine LTX or Lipofectamine 3000 (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA) in accordance with the manufacturer’s instructions. RVPs were produced at 30°C in a low-glucose formulation of DMEM containing 25 mM HEPES (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA), 7% FBS, and 100 U/ml PS. RVP-containing supernatants were collected at 72, 96, 120, or 144 h posttransfection, filtered through a 0.22-μm membrane, and stored at −80°C. The infectious titers of RVPs were determined using Raji-DCSIGNR cells as described previously (50, 77). Raji-DCSIGNR cells were infected with serial dilutions of RVP-containing supernatants, incubated at 37°C for 2 days, and scored for infection as a function of green fluorescent protein (GFP) expression by flow cytometry.

Neutralization assays.

DENV RVP stocks were diluted to ensure antibody excess at informative points of the dose-response curve and incubated with serial dilutions of MAb or heat-inactivated serum for 1 h at room temperature or 37°C prior to the addition of Raji-DCSIGNR cells. Infections were carried out at 37°C for 48 h, and infectivity was scored as the fraction of GFP-expressing cells determined using flow cytometry. Antibody dose-response curves were analyzed using nonlinear regression analysis (with a variable slope) (GraphPad Software, San Diego, CA). Data are expressed as the concentration of antibody (EC50) or reciprocal serum dilution (NT50) required to reduce infection by half.

Statistical analysis.

Statistical analyses were performed using Prism software version 8.0.1 for Mac OS X (GraphPad Software, San Diego, CA). EC50s and NT50s were analyzed using the nonparametric Mann-Whitney or Wilcoxon matched-pairs signed-rank test to compare two groups. One-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) with Tukey’s multiple comparisons correction was used to compare more than two groups. A P value of ≤0.05 was considered statistically significant.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This work was supported by the Intramural Research Program of the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases, NIH. L.A.V. was additionally supported by NIH Institutional Training grant 2T32AI051967-06A1 awarded to the University of Maryland.

We thank members of the Pierson lab for critically reading the manuscript and for helpful discussions.

Contributor Information

Theodore C. Pierson, Email: piersontc@mail.nih.gov.

Kimberly A. Dowd, Email: dowdka@mail.nih.gov.

Mark T. Heise, University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill

REFERENCES

- 1.Cattarino L, Rodriguez-Barraquer I, Imai N, Cummings DAT, Ferguson NM. 2020. Mapping global variation in dengue transmission intensity. Sci Transl Med 12:eaax4144. 10.1126/scitranslmed.aax4144. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.World Health Organization. 2009. Dengue: guidelines for diagnosis, treatment, prevention and control, new edition. World Health Organization, Geneva, Switzerland. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Katzelnick LC, Gresh L, Halloran ME, Mercado JC, Kuan G, Gordon A, Balmaseda A, Harris E. 2017. Antibody-dependent enhancement of severe dengue disease in humans. Science 358:929–932. 10.1126/science.aan6836. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Guzman MG, Alvarez M, Halstead SB. 2013. Secondary infection as a risk factor for dengue hemorrhagic fever/dengue shock syndrome: an historical perspective and role of antibody-dependent enhancement of infection. Arch Virol 158:1445–1459. 10.1007/s00705-013-1645-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Guy B, Noriega F, Ochiai RL, L'Azou M, Delore V, Skipetrova A, Verdier F, Coudeville L, Savarino S, Jackson N. 2017. A recombinant live attenuated tetravalent vaccine for the prevention of dengue. Expert Rev Vaccines 16:1–13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Capeding MR, Tran NH, Hadinegoro SR, Ismail HI, Chotpitayasunondh T, Chua MN, Luong CQ, Rusmil K, Wirawan DN, Nallusamy R, Pitisuttithum P, Thisyakorn U, Yoon IK, van der Vliet D, Langevin E, Laot T, Hutagalung Y, Frago C, Boaz M, Wartel TA, Tornieporth NG, Saville M, Bouckenooghe A, CYD 14 Study Group . 2014. Clinical efficacy and safety of a novel tetravalent dengue vaccine in healthy children in Asia: a phase 3, randomised, observer-masked, placebo-controlled trial. Lancet 384:1358–1365. 10.1016/S0140-6736(14)61060-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hadinegoro SR, Arredondo-Garcia JL, Capeding MR, Deseda C, Chotpitayasunondh T, Dietze R, Muhammad Ismail HI, Reynales H, Limkittikul K, Rivera-Medina DM, Tran HN, Bouckenooghe A, Chansinghakul D, Cortes M, Fanouillere K, Forrat R, Frago C, Gailhardou S, Jackson N, Noriega F, Plennevaux E, Wartel TA, Zambrano B, Saville M, Group C-TDVW . 2015. Efficacy and long-term safety of a dengue vaccine in regions of endemic disease. N Engl J Med 373:1195–1206. 10.1056/NEJMoa1506223. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Villar L, Dayan GH, Arredondo-Garcia JL, Rivera DM, Cunha R, Deseda C, Reynales H, Costa MS, Morales-Ramirez JO, Carrasquilla G, Rey LC, Dietze R, Luz K, Rivas E, Miranda Montoya MC, Cortes Supelano M, Zambrano B, Langevin E, Boaz M, Tornieporth N, Saville M, Noriega F, CYD15 Study Group . 2015. Efficacy of a tetravalent dengue vaccine in children in Latin America. N Engl J Med 372:113–123. 10.1056/NEJMoa1411037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.World Health Organization. 2016. Dengue vaccine: WHO position paper—July 2016. Wkly Epidemiol Rec 91:349–364. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.World Health Organization. 2017. Dengue vaccine: WHO position paper, July 2016 - recommendations. Vaccine 35:1200–1201. 10.1016/j.vaccine.2016.10.070. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Pierson TC, Diamond MS. 2013. Flaviviruses. In Fields BN, Knipe DM, Howley PM (ed), Fields virology, 6th ed. Wolters Kluwer Health/Lippincott Williams & Wilkins, Philadelphia, PA. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kostyuchenko VA, Zhang Q, Tan JL, Ng TS, Lok SM. 2013. Immature and mature dengue serotype 1 virus structures provide insight into the maturation process. J Virol 87:7700–7707. 10.1128/JVI.00197-13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Zhang Y, Corver J, Chipman PR, Zhang W, Pletnev SV, Sedlak D, Baker TS, Strauss JH, Kuhn RJ, Rossmann MG. 2003. Structures of immature flavivirus particles. EMBO J 22:2604–2613. 10.1093/emboj/cdg270. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Li L, Lok SM, Yu IM, Zhang Y, Kuhn RJ, Chen J, Rossmann MG. 2008. The flavivirus precursor membrane-envelope protein complex: structure and maturation. Science 319:1830–1834. 10.1126/science.1153263. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Yu IM, Zhang W, Holdaway HA, Li L, Kostyuchenko VA, Chipman PR, Kuhn RJ, Rossmann MG, Chen J. 2008. Structure of the immature dengue virus at low pH primes proteolytic maturation. Science 319:1834–1837. 10.1126/science.1153264. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Zhang X, Ge P, Yu X, Brannan JM, Bi G, Zhang Q, Schein S, Zhou ZH. 2013. Cryo-EM structure of the mature dengue virus at 3.5-A resolution. Nat Struct Mol Biol 20:105–110. 10.1038/nsmb.2463. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kuhn RJ, Zhang W, Rossmann MG, Pletnev SV, Corver J, Lenches E, Jones CT, Mukhopadhyay S, Chipman PR, Strauss EG, Baker TS, Strauss JH. 2002. Structure of dengue virus: implications for flavivirus organization, maturation, and fusion. Cell 108:717–725. 10.1016/s0092-8674(02)00660-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Elshuber S, Allison SL, Heinz FX, Mandl CW. 2003. Cleavage of protein prM is necessary for infection of BHK-21 cells by tick-borne encephalitis virus. J Gen Virol 84:183–191. 10.1099/vir.0.18723-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Pierson TC, Diamond MS. 2012. Degrees of maturity: the complex structure and biology of flaviviruses. Curr Opin Virol 2:168–175. 10.1016/j.coviro.2012.02.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.de Silva AM, Harris E. 2017. Which dengue vaccine approach is the most promising, and should we be concerned about enhanced disease after vaccination? The path to a dengue vaccine: learning from human natural dengue infection studies and vaccine trials. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Biol 10:a028811. 10.1101/cshperspect.a029371. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Heinz FX, Stiasny K. 2012. Flaviviruses and their antigenic structure. J Clin Virol 55:289–295. 10.1016/j.jcv.2012.08.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Fibriansah G, Lok SM. 2016. The development of therapeutic antibodies against dengue virus. Antiviral Res 128:7–19. 10.1016/j.antiviral.2016.01.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Diamond MS, Pierson TC, Fremont DH. 2008. The structural immunology of antibody protection against West Nile virus. Immunol Rev 225:212–225. 10.1111/j.1600-065X.2008.00676.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Shrestha B, Brien JD, Sukupolvi-Petty S, Austin SK, Edeling MA, Kim T, O'Brien KM, Nelson CA, Johnson S, Fremont DH, Diamond MS. 2010. The development of therapeutic antibodies that neutralize homologous and heterologous genotypes of dengue virus type 1. PLoS Pathog 6:e1000823. 10.1371/journal.ppat.1000823. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Oliphant T, Engle M, Nybakken GE, Doane C, Johnson S, Huang L, Gorlatov S, Mehlhop E, Marri A, Chung KM, Ebel GD, Kramer LD, Fremont DH, Diamond MS. 2005. Development of a humanized monoclonal antibody with therapeutic potential against West Nile virus. Nat Med 11:522–530. 10.1038/nm1240. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Williams KL, Wahala WM, Orozco S, de Silva AM, Harris E. 2012. Antibodies targeting dengue virus envelope domain III are not required for serotype-specific protection or prevention of enhancement in vivo. Virology 429:12–20. 10.1016/j.virol.2012.03.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Wahala WM, Kraus AA, Haymore LB, Accavitti-Loper MA, de Silva AM. 2009. Dengue virus neutralization by human immune sera: role of envelope protein domain III-reactive antibody. Virology 392:103–113. 10.1016/j.virol.2009.06.037. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Rey FA, Stiasny K, Vaney MC, Dellarole M, Heinz FX. 2018. The bright and the dark side of human antibody responses to flaviviruses: lessons for vaccine design. EMBO Rep 19:206–224. 10.15252/embr.201745302. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Dejnirattisai W, Wongwiwat W, Supasa S, Zhang X, Dai X, Rouvinski A, Jumnainsong A, Edwards C, Quyen NTH, Duangchinda T, Grimes JM, Tsai WY, Lai CY, Wang WK, Malasit P, Farrar J, Simmons CP, Zhou ZH, Rey FA, Mongkolsapaya J, Screaton GR. 2015. A new class of highly potent, broadly neutralizing antibodies isolated from viremic patients infected with dengue virus. Nat Immunol 16:170–177. 10.1038/ni.3058. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Vratskikh O, Stiasny K, Zlatkovic J, Tsouchnikas G, Jarmer J, Karrer U, Roggendorf M, Roggendorf H, Allwinn R, Heinz FX. 2013. Dissection of antibody specificities induced by yellow fever vaccination. PLoS Pathog 9:e1003458. 10.1371/journal.ppat.1003458. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Jarmer J, Zlatkovic J, Tsouchnikas G, Vratskikh O, Strauß J, Aberle JH, Chmelik V, Kundi M, Stiasny K, Heinz FX. 2014. Variation of the specificity of the human antibody responses after tick-borne encephalitis virus infection and vaccination. J Virol 88:13845–13857. 10.1128/JVI.02086-14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Rouvinski A, Guardado-Calvo P, Barba-Spaeth G, Duquerroy S, Vaney MC, Kikuti CM, Navarro Sanchez ME, Dejnirattisai W, Wongwiwat W, Haouz A, Girard-Blanc C, Petres S, Shepard WE, Despres P, Arenzana-Seisdedos F, Dussart P, Mongkolsapaya J, Screaton GR, Rey FA. 2015. Recognition determinants of broadly neutralizing human antibodies against dengue viruses. Nature 520:109–113. 10.1038/nature14130. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Collins MH, Tu HA, Gimblet-Ochieng C, Liou GA, Jadi RS, Metz SW, Thomas A, McElvany BD, Davidson E, Doranz BJ, Reyes Y, Bowman NM, Becker-Dreps S, Bucardo F, Lazear HM, Diehl SA, de Silva AM. 2019. Human antibody response to Zika targets type-specific quaternary structure epitopes. JCI Insight 4 10.1172/jci.insight.124588. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.de Alwis R, Beltramello M, Messer WB, Sukupolvi-Petty S, Wahala WMPB, Kraus A, Olivarez NP, Pham Q, Brien JD, Brian J, Tsai W-Y, Wang W-K, Halstead S, Kliks S, Diamond MS, Baric R, Lanzavecchia A, Sallusto F, de Silva AM. 2011. In-depth analysis of the antibody response of individuals exposed to primary dengue virus infection. PLoS Negl Trop Dis 5:e1188. 10.1371/journal.pntd.0001188. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Beltramello M, Williams KL, Simmons CP, Macagno A, Simonelli L, Quyen NT, Sukupolvi-Petty S, Navarro-Sanchez E, Young PR, de Silva AM, Rey FA, Varani L, Whitehead SS, Diamond MS, Harris E, Lanzavecchia A, Sallusto F. 2010. The human immune response to Dengue virus is dominated by highly cross-reactive antibodies endowed with neutralizing and enhancing activity. Cell Host Microbe 8:271–283. 10.1016/j.chom.2010.08.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Smith SA, de Alwis R, Kose N, Durbin AP, Whitehead SS, de Silva AM, Crowe JE, Jr.. 2013. Human monoclonal antibodies derived from memory B cells following live attenuated dengue virus vaccination or natural infection exhibit similar characteristics. J Infect Dis 207:1898–1908. 10.1093/infdis/jit119. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.VanBlargan LA, Mukherjee S, Dowd KA, Durbin AP, Whitehead SS, Pierson TC. 2013. The type-specific neutralizing antibody response elicited by a dengue vaccine candidate is focused on two amino acids of the envelope protein. PLoS Pathog 9:e1003761. 10.1371/journal.ppat.1003761. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.de Alwis R, Smith SA, Olivarez NP, Messer WB, Huynh JP, Wahala WM, White LJ, Diamond MS, Baric RS, Crowe JE, Jr, de Silva AM. 2012. Identification of human neutralizing antibodies that bind to complex epitopes on dengue virions. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 109:7439–7444. 10.1073/pnas.1200566109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Swanstrom JA, Nivarthi UK, Patel B, Delacruz MJ, Yount B, Widman DG, Durbin AP, Whitehead SS, De Silva AM, Baric RS. 2019. Beyond neutralizing antibody levels: the epitope specificity of antibodies induced by National Institutes of Health monovalent dengue virus vaccines. J Infect Dis 220:219–227. 10.1093/infdis/jiz109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Austin SK, Dowd KA, Shrestha B, Nelson CA, Edeling MA, Johnson S, Pierson TC, Diamond MS, Fremont DH. 2012. Structural basis of differential neutralization of DENV-1 genotypes by an antibody that recognizes a cryptic epitope. PLoS Pathog 8:e1002930. 10.1371/journal.ppat.1002930. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Brien JD, Austin SK, Sukupolvi-Petty S, O'Brien KM, Johnson S, Fremont DH, Diamond MS. 2010. Genotype-specific neutralization and protection by antibodies against dengue virus type 3. J Virol 84:10630–10643. 10.1128/JVI.01190-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Dowd KA, DeMaso CR, Pierson TC. 2015. Genotypic differences in dengue virus neutralization are explained by a single amino acid mutation that modulates virus breathing. mBio 6:e01559-15. 10.1128/mBio.01559-15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Sukupolvi-Petty S, Austin SK, Engle M, Brien JD, Dowd KA, Williams KL, Johnson S, Rico-Hesse R, Harris E, Pierson TC, Fremont DH, Diamond MS. 2010. Structure and function analysis of therapeutic monoclonal antibodies against dengue virus type 2. J Virol 84:9227–9239. 10.1128/JVI.01087-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Sukupolvi-Petty S, Brien JD, Austin SK, Shrestha B, Swayne S, Kahle K, Doranz BJ, Johnson S, Pierson TC, Fremont DH, Diamond MS. 2013. Functional analysis of antibodies against dengue virus type 4 reveals strain-dependent epitope exposure that impacts neutralization and protection. J Virol 87:8826–8842. 10.1128/JVI.01314-13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Wahala WM, Donaldson EF, de Alwis R, Accavitti-Loper MA, Baric RS, de Silva AM. 2010. Natural strain variation and antibody neutralization of dengue serotype 3 viruses. PLoS Pathog 6:e1000821. 10.1371/journal.ppat.1000821. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Flipse J, Smit JM. 2015. The complexity of a dengue vaccine: a review of the human antibody response. PLoS Negl Trop Dis 9:e0003749. 10.1371/journal.pntd.0003749. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Goncalvez AP, Escalante AA, Pujol FH, Ludert JE, Tovar D, Salas RA, Liprandi F. 2002. Diversity and evolution of the envelope gene of dengue virus type 1. Virology 303:110–119. 10.1006/viro.2002.1686. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Weaver SC, Vasilakis N. 2009. Molecular evolution of dengue viruses: contributions of phylogenetics to understanding the history and epidemiology of the preeminent arboviral disease. Infect Genet Evol 9:523–540. 10.1016/j.meegid.2009.02.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Dowd KA, Mukherjee S, Kuhn RJ, Pierson TC. 2014. Combined effects of the structural heterogeneity and dynamics of flaviviruses on antibody recognition. J Virol 88:11726–11737. 10.1128/JVI.01140-14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Ansarah-Sobrinho C, Nelson S, Jost CA, Whitehead SS, Pierson TC. 2008. Temperature-dependent production of pseudoinfectious dengue reporter virus particles by complementation. Virology 381:67–74. 10.1016/j.virol.2008.08.021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Durbin AP, McArthur J, Marron JA, Blaney JE, Jr, Thumar B, Wanionek K, Murphy BR, Whitehead SS. 2006. The live attenuated dengue serotype 1 vaccine rDEN1Delta30 is safe and highly immunogenic in healthy adult volunteers. Hum Vaccin 2:167–173. 10.4161/hv.2.4.2944. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Durbin AP, Kirkpatrick BD, Pierce KK, Elwood D, Larsson CJ, Lindow JC, Tibery C, Sabundayo BP, Shaffer D, Talaat KR, Hynes NA, Wanionek K, Carmolli MP, Luke CJ, Murphy BR, Subbarao K, Whitehead SS. 2013. A single dose of any of four different live attenuated tetravalent dengue vaccines is safe and immunogenic in flavivirus-naive adults: a randomized, double-blind clinical trial. J Infect Dis 207:957–965. 10.1093/infdis/jis936. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Durbin AP, Whitehead SS, Shaffer D, Elwood D, Wanionek K, Thumar B, Blaney JE, Murphy BR, Schmidt AC. 2011. A single dose of the DENV-1 candidate vaccine rDEN1Delta30 is strongly immunogenic and induces resistance to a second dose in a randomized trial. PLoS Negl Trop Dis 5:e1267. 10.1371/journal.pntd.0001267. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Hatcher EL, Zhdanov SA, Bao Y, Blinkova O, Nawrocki EP, Ostapchuck Y, Schaffer AA, Brister JR. 2017. Virus variation resource—improved response to emergent viral outbreaks. Nucleic Acids Res 45:D482–D490. 10.1093/nar/gkw1065. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Pierson TC, Fremont DH, Kuhn RJ, Diamond MS. 2008. Structural insights into the mechanisms of antibody-mediated neutralization of flavivirus infection: implications for vaccine development. Cell Host Microbe 4:229–238. 10.1016/j.chom.2008.08.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Lok SM, Kostyuchenko V, Nybakken GE, Holdaway HA, Battisti AJ, Sukupolvi-Petty S, Sedlak D, Fremont DH, Chipman PR, Roehrig JT, Diamond MS, Kuhn RJ, Rossmann MG. 2008. Binding of a neutralizing antibody to dengue virus alters the arrangement of surface glycoproteins. Nat Struct Mol Biol 15:312–317. 10.1038/nsmb.1382. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Oliphant T, Nybakken GE, Engle M, Xu Q, Nelson CA, Sukupolvi-Petty S, Marri A, Lachmi BE, Olshevsky U, Fremont DH, Pierson TC, Diamond MS. 2006. Antibody recognition and neutralization determinants on domains I and II of West Nile Virus envelope protein. J Virol 80:12149–12159. 10.1128/JVI.01732-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Stiasny K, Kiermayr S, Holzmann H, Heinz FX. 2006. Cryptic properties of a cluster of dominant flavivirus cross-reactive antigenic sites. J Virol 80:9557–9568. 10.1128/JVI.00080-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Nelson S, Jost CA, Xu Q, Ess J, Martin JE, Oliphant T, Whitehead SS, Durbin AP, Graham BS, Diamond MS, Pierson TC. 2008. Maturation of West Nile virus modulates sensitivity to antibody-mediated neutralization. PLoS Pathog 4:e1000060. 10.1371/journal.ppat.1000060. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Vogt MR, Dowd KA, Engle M, Tesh RB, Johnson S, Pierson TC, Diamond MS. 2011. Poorly neutralizing cross-reactive antibodies against the fusion loop of West Nile virus envelope protein protect in vivo via Fcgamma receptor and complement-dependent effector mechanisms. J Virol 85:11567–11580. 10.1128/JVI.05859-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Cherrier MV, Kaufmann B, Nybakken GE, Lok SM, Warren JT, Chen BR, Nelson CA, Kostyuchenko VA, Holdaway HA, Chipman PR, Kuhn RJ, Diamond MS, Rossmann MG, Fremont DH. 2009. Structural basis for the preferential recognition of immature flaviviruses by a fusion-loop antibody. EMBO J 28:3269–3276. 10.1038/emboj.2009.245. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Mukherjee S, Dowd KA, Manhart CJ, Ledgerwood JE, Durbin AP, Whitehead SS, Pierson TC. 2014. Mechanism and significance of cell type-dependent neutralization of flaviviruses. J Virol 88:7210–7220. 10.1128/JVI.03690-13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Dowd KA, Pierson TC. 2018. The many faces of a dynamic virion: implications of viral breathing on flavivirus biology and immunogenicity. Annu Rev Virol 5:185–207. 10.1146/annurev-virology-092917-043300. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Fibriansah G, Ng TS, Kostyuchenko VA, Lee J, Lee S, Wang J, Lok SM. 2013. Structural changes in dengue virus when exposed to a temperature of 37 degrees C. J Virol 87:7585–7592. 10.1128/JVI.00757-13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Zhang X, Sheng J, Plevka P, Kuhn RJ, Diamond MS, Rossmann MG. 2013. Dengue structure differs at the temperatures of its human and mosquito hosts. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 110:6795–6799. 10.1073/pnas.1304300110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Lim XN, Shan C, Marzinek JK, Dong H, Ng TS, Ooi JSG, Fibriansah G, Wang J, Verma CS, Bond PJ, Shi PY, Lok SM. 2019. Molecular basis of dengue virus serotype 2 morphological switch from 29°C to 37°C. PLoS Pathog 15:e1007996. 10.1371/journal.ppat.1007996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Dowd KA, Jost CA, Durbin AP, Whitehead SS, Pierson TC. 2011. A dynamic landscape for antibody binding modulates antibody-mediated neutralization of West Nile virus. PLoS Pathog 7:e1002111. 10.1371/journal.ppat.1002111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Katzelnick LC, Fonville JM, Gromowski GD, Bustos Arriaga J, Green A, James SL, Lau L, Montoya M, Wang C, VanBlargan LA, Russell CA, Thu HM, Pierson TC, Buchy P, Aaskov JG, Munoz-Jordan JL, Vasilakis N, Gibbons RV, Tesh RB, Osterhaus AD, Fouchier RA, Durbin A, Simmons CP, Holmes EC, Harris E, Whitehead SS, Smith DJ. 2015. Dengue viruses cluster antigenically but not as discrete serotypes. Science 349:1338–1343. 10.1126/science.aac5017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Shihada S, Emmerich P, Thome-Bolduan C, Jansen S, Gunther S, Frank C, Schmidt-Chanasit J, Cadar D. 2017. Genetic diversity and new lineages of dengue virus serotypes 3 and 4 in returning travelers, Germany, 2006–2015. Emerg Infect Dis 23:272–275. 10.3201/eid2302.160751. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Shin D, Richards SL, Alto BW, Bettinardi DJ, Smartt CT. 2013. Genome sequence analysis of dengue virus 1 isolated in Key West, Florida. PLoS One 8:e74582. 10.1371/journal.pone.0074582. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Goo L, VanBlargan LA, Dowd KA, Diamond MS, Pierson TC. 2017. A single mutation in the envelope protein modulates flavivirus antigenicity, stability, and pathogenesis. PLoS Pathog 13:e1006178. 10.1371/journal.ppat.1006178. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Durbin AP, McArthur JH, Marron JA, Blaney JE, Thumar B, Wanionek K, Murphy BR, Whitehead SS. 2006. rDEN2/4Delta30(ME), a live attenuated chimeric dengue serotype 2 vaccine is safe and highly immunogenic in healthy dengue-naive adults. Hum Vaccin 2:255–260. 10.4161/hv.2.6.3494. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Huang CY, Butrapet S, Pierro DJ, Chang GJ, Hunt AR, Bhamarapravati N, Gubler DJ, Kinney RM. 2000. Chimeric dengue type 2 (vaccine strain PDK-53)/dengue type 1 virus as a potential candidate dengue type 1 virus vaccine. J Virol 74:3020–3028. 10.1128/jvi.74.7.3020-3028.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Puri B, Nelson W, Porter KR, Henchal EA, Hayes CG. 1998. Complete nucleotide sequence analysis of a Western Pacific dengue-1 virus strain. Virus Genes 17:85–88. 10.1023/a:1008009202695. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Pierson TC, Sanchez MD, Puffer BA, Ahmed AA, Geiss BJ, Valentine LE, Altamura LA, Diamond MS, Doms RW. 2006. A rapid and quantitative assay for measuring antibody-mediated neutralization of West Nile virus infection. Virology 346:53–65. 10.1016/j.virol.2005.10.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.VanBlargan LA, Davis KA, Dowd KA, Akey DL, Smith JL, Pierson TC. 2015. Context-dependent cleavage of the capsid protein by the West Nile virus protease modulates the efficiency of virus assembly. J Virol 89:8632–8642. 10.1128/JVI.01253-15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Pierson TC, Xu Q, Nelson S, Oliphant T, Nybakken GE, Fremont DH, Diamond MS. 2007. The stoichiometry of antibody-mediated neutralization and enhancement of West Nile virus infection. Cell Host Microbe 1:135–145. 10.1016/j.chom.2007.03.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]