Abstract

Dental microwear analysis has been employed in studies of a wide range of modern and fossil animals, yielding insights into the biology/ecology of those taxa. Some researchers have suggested that dental microwear patterns ultimately relate back to the material properties of the foods being consumed, whereas others have suggested that, because exogenous grit is harder than organic materials in food, grit should have an overwhelming impact on dental microwear patterns.

To shed light on this issue, laboratory-based feeding experiments were conducted on tufted capuchin monkeys [Sapajus apella] with dental impressions taken before and after consumption of different artificial foods. The foods were (1) brittle custom-made biscuits laced with either of two differently-sized aluminum silicate abrasives, and (2) ductile custom-made “gummies” laced with either of the two same abrasives. In both cases, animals were allowed to feed on the foods for 36 hours before follow-up dental impressions were taken. Resultant casts were analyzed using a scanning electron microscope. We asked five questions: (1) would the animals consume different amounts of each food item, (2) what types of dental microwear would be formed, (3) would rates of dental microwear differ between the consumption of biscuits (i.e., brittle) versus gummies (i.e., ductile), (4) would rates of dental microwear differ between foods including larger- versus smaller-grained abrasives, and (5) would rates of dental microwear differ between molar shearing and crushing facets in the animals in these experiments?

Results indicated that (1) fewer biscuits were consumed when laced with larger-grained abrasives (as opposed to smaller-grained abrasives), but no such difference was observed in the consumption of gummies, (2) in all cases, a variety of dental microwear features was formed, (3) rates of dental microwear were higher when biscuits versus gummies were consumed, (4) biscuits laced with larger-grained abrasives caused a higher percentage of new features per item consumed, and (5) the only difference between facets occurred with the processing of biscuits, where crushing facets showed a faster rate of wear than shearing facets. These findings suggest that the impact of exogenous grit on dental microwear is the result of a dynamic, complex interaction between (at the very least) grit size, food material properties, and time spent feeding - which is further evidence of the multifactorial nature of dental microwear formation.

Keywords: dental impressions, ingestion, mastication, platyrrhine, scanning electron microscopy

1. Introduction

Dental microwear analysis has been employed in studies of a wide range of modern and fossil animals, yielding many insights into the biology and ecology of those taxa (e.g., Purnell et al., 2012; Gill et al., 2014; Estalrrich et al., 2015; Calandra and Merceron, 2016; Schulz-Kornas et al., 2019; Winkler et al., 2019). Paleontological studies have been based on either low- or high-magnification analyses (so-called “mesowear” and “microwear” techniques) and they have produced both expected and unexpected results (e.g., comparisons of South and East African robust australopithecines [Ungar et al., 2008], and documentation of browsing and grazing in extinct giraffids [Solounias et al., 1988; Merceron et al., 2018.]). These findings have often prompted spirited discussion about their implications, both for paleobiology and microwear analyses in general (e.g., Daegling et al., 2013; Strait et al., 2013). One of the reasons for debate is that the etiology and lifespan of microwear features and patterns are still the subject of intensive study.

Some researchers have attempted to better understand microwear formation and turnover using in vitro studies, which have shown that hard and soft materials can mark enamel (Gügel et al., 2001; Borrero-Lopez et al., 2015; Daegling et al., 2016; Karme et al., 2016), and that the physical properties of foods can also impact the effects of abrasives on enamel (Hua et al., 2015, 2020). Others have turned to studies of dental microwear in wild populations to relate microwear patterns to consumed foods or abrasives. In contrast to more traditional studies of teeth from museum collections (e.g., Teaford, 1988; Strait, 1993; Pérez-Pérez et al., 1994; Daegling and Grine, 1999; Semprebon et al., 2004), these studies have aimed for more precise correlations between microwear and diet, either by analyzing skeletal collections from populations that have yielded the dietary information on which the microwear inferences have been based (e.g., Mainland, 2003; Merceron et al., 2004, 2010; Schulz-Kornas et al., 2019; Stuhlträger et al., 2019) or by taking dental impressions directly from the live animals whose feeding has been documented (e.g., Teaford and Glander 1991, 1996; Nystrom et al., 2004; Percher et al., 2018). Finally, a few researchers have conducted longitudinal experiments with laboratory animals to study microwear formation, again using either skeletal collections created from the actual study populations (e.g., Purnell et al., 2006; Schulz et al., 2013; Hoffman et al., 2015; Merceron et al., 2016; Winkler et al., 2019; Ackermans et al., 2020; Gallego-Valle et al., 2020; Schulz-Kornas et al., 2020) or dental impressions taken in vivo during the study (Teaford and Oyen, 1989a; Teaford and Tylenda, 1991; Teaford and Lytle 1996; Romero et al., 2012; Teaford et al., 2017, 2020). Most of the former studies tended to use some form of dental microwear texture analysis to compare summary characterizations of the tooth surfaces of animals fed one diet vs. animals fed another diet (e.g., are tooth surfaces more microscopically “complex” in animals fed hard foods or foods laced with abrasives?). By contrast, the in vivo studies have focused on changes in tooth surfaces between two points in time for the same animal. As a result, they have documented the appearance of new features and/or disappearance of old features (e.g., “scratches” or “pits”) between the start of the experiment and its completion, and they have generally not looked at changes in dental microwear texture through time.

Some researchers have suggested that, because exogenous grit is harder than organic materials in food, grit should have an overwhelming impact on dental microwear patterns (e.g., Lucas et al., 2013; van Casteren et al., 2020). This work has spawned a series of studies showing that, while populations from different ecological settings, with presumably different grit loads/profiles, may still show microwear differences associated with differences in diet (e.g., Ungar et al., 2016), the process of dental microwear formation by exogenous grit is not a straightforward one (e.g., Schulz et al., 2013; Merceron et al., 2016; Sanson et al, 2007, 2017; Aiba et al., 2019; Winkler et al., 2019; van Casteren et al., 2020). In essence, while some primate populations may experience high grit loads on their foods (Daegling and Grine, 1999; van Casteren et al., 2019), the potential impact of those abrasives on dental microwear patterns will depend on a number of factors, including the physical properties of those abrasives (Ungar et al., 1995; Galbany et al., 2014; Lucas et al., 2013, 2014), the precise locations of the foods within the environment (Geissler et al., 2019), and behavioral adaptations to either avoid foods with abrasives (primates: Laird et al., 2019; Venkataraman et al., 2019; other mammals: Gali-Muhtasib and Smith, 1992; Cotterill et al., 2007; Massey et al., 2007; Ackermans et al., 2019), to clean abrasives from the foods (primates; Kawamura, 1959; Visalberghi and Fragaszy 1990; Allritz et al., 2013; Rosien et al., 2019; other mammals: Sommer et al., 2016), or to alter chewing behavior to minimize dental wear (Prinz, 2004).

Moreover, even if there are significant amounts of abrasives in or on foods, those foods will still be processed using precise tooth and jaw movements dictated in part by interactions between dental morphology and the physical and material properties of the foods. Traditionally, these movements have been viewed in terms of basic contrasts between, for example, the processing of hard foods (those that resist deformation) versus the processing of tough foods (those that resist crack growth), with the former requiring greater force concentrations and the latter requiring greater movements between teeth and food as occlusal work (Simpson, 1933, 1936; Gordon, 1984; Ungar and Sponheimer, 2011).

However, more detailed studies of jaw movements and food processing have demonstrated that the relationships between food material properties (FMPs) and jaw movements are complicated; varying across taxa and contexts (Humans: Ahlgren, 1976; Gibbs et al., 1981, 1982; Pröschel & Hofmann, 1988; Takada et al., 1994; Hiiemae et al., 1996; Peyron et al., 1997; Anderson et al., 2002; Foster et al., 2006; Laird, 2017; Non-human primates: Iriarte-Díaz et al., 2011; Reed and Ross, 2010; Laird et al., 2020a; and Bats: Greet & De Vree, 1984;). Thus, while mechanically challenging foods are typically processed using greater muscle activation and presumably higher bite forces (Oron and Crompton 1985; Horio and Kawamura 1989; Hylander and Johnson 1994; Agrawal et al. 1998; Mioche et al. 1999; Peyron et al. 2002; Foster et al. 2006; Woda et al.2006; Laird et al., 2020b), relationships between food properties and jaw movements likely vary within and between taxa, to the point where jaw movements are not consistently associated with a particular FMP’s (Agrawal et al., 2000; Reed and Ross, 2010; Laird, 2017; Laird et al., 2020a). Moreover, variation in ingested FMPs accounts for lower amounts of variation in relative timing of muscle activity, jaw kinematics, and mandibular bone strain than variation occurring across a chewing sequence (Vinyard et al., 2008; Iriarte-Diaz et al., 2011; Ross and Iriarte-Diaz, 2014, 2019; Ross et al., 2016). How variation in jaw kinematics relates to variation in occlusal dynamics and dental microwear patterns remains to be precisely articulated.

Clearly, if we are to really understand the complex process of dental microwear formation, and its interrelationships with FMPs and grit load, we need more experimental work on live animals processing foods of known FMPs and different grit loads. Only with such information will we be able to glean the most insights on diet and tooth use in paleobiology and paleoecology. To shed further light on this issue, three captive capuchin monkeys (Sapajus apella) at the University of Chicago were fed artificial foods that differed in both physical properties and grit load. We asked five questions: (1) would the animals consume different amounts of each food item, (2) what types of dental microwear would be formed, (3) would rates of dental microwear differ between the consumption of biscuits versus the consumption of gummies, (4) would rates of dental microwear differ between foods including larger- versus smaller-grained abrasives, and (5) would rates of dental microwear differ between molar shearing and crushing facets in the animals in these experiments?

2. Materials and methods

2.1. Subjects

Feeding data and dental impressions were collected from three adult female tufted capuchin monkeys Sapajus apella (UC-A, UC-C, and UC-L) housed in the Animal Resources Center at the University of Chicago in early 2019. The subjects were between ages of 7–11 at the time of the experiments, had all of their teeth, and displayed no obvious asymmetries, diseases, or deformities of their craniofacial or dental anatomy. All animals were group housed in standard approved caging, where they had been given ad libitum water and a daily diet including monkey biscuits, as well as various fruits and vegetables before the feeding experiments for this study. During the study, each animal was housed separately and all enrichment items (e.g., toys) were removed from the cages to reduce the likelihood of microwear unrelated to feeding. All procedures were approved by the University of Chicago under Animal Care and Use Protocol (72430) and conformed to the principles outlined in the Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals (NIH Publication 86–23, revised 1985) and the requirements of the Animal Welfare Act.

2.2. Feeding experiments

Two feeding experiments were carried out in this study. Each began with the animal being anesthetized and dental impressions taken of all four quadrants using standard techniques (see sections 2.3–2.4 below). These impressions served as a baseline representation of the microwear caused by their normal laboratory diet prior to the experiments. Based on previous work with these species (Teaford et al., 2017, 2020), and the fact that we were unsure of how much of the experimental foods they would consume, or what the effects of those foods would be (especially the gummies), we chose to allow a significant amount of time between baseline and follow-up in each experiment. Thus, after the baseline impressions were taken, the animals were allowed to feed ad libitum on custom-made biscuits (see section 2.3) plus a liquid nutritional supplement for 36 hours1. The animals were then anesthetized again following an additional ~18 hours without food and a follow-up impression was taken. After that second impression, they were then allowed to feed ad libitum on custom-made gummies (see section 2.3) plus a liquid nutritional supplement for another 36 hours before a final set of impressions was taken, again after 18 hours without additional food. We note that, unlike in our previously-published experimental work (Teaford et al., 2017, 2020), baseline and follow-up impressions were not taken on the same day; rather, in both of the experiments in this study, the animals were allowed to feed on each experimental food for 36 hours.

2.3. Foods

The foods for the two experiments were custom-made biscuits and gummies. Biscuit ingredients included flour, egg, pumpkin, water, maple syrup, peanut butter and trace spices. This mixture was baked (350° for 40 min) to create 27.5 mm diameter circular biscuits (varied by experiment) fed to monkeys. Manufactured gummies (Haribo Gummi Candies) were melted and re-cooled with abrasives suspended as 1.7.5 mm cubes for experiments. Elastic modulus of biscuits was measured in compression (Electropuls e3000, Instron) and averaged 3.5 MPa (SD=2.7, n=5). Biscuit modulus is markedly higher (~50x) than previously measured elastic modulus of gummies (0.07 MPa) (Williams et al., 2005). These two foods were chosen to emphasize the essential material property differences between the brittleness of biscuits compared to the ductility of gummies.

Each food was mixed during preparation with either fine sand (180 microns-μm) aluminum silicate pumice (10% by weight) from Hess Pumice (Hess grade 0-https://pumicestore.com/PDFs/TDS-Grade-0.pdf) or coarse sand (1400 μm) aluminum silicate pumice (10% by weight) from Hess Pumice (Hess grade 3-https://pumicestore.com/PDFs/TDS-Grade-3.pdf). Pumice is a common component in soil and windblown dust, and ongoing work on wild capuchins in Brazil and Suriname (van Casteren, personal communication) suggests that some grit particles on foods exceed 500 microns in diameter. Thus, while the coarse sand may not be the most common particle size encountered by capuchins in the wild, the goal of this experiment was not to try to mimic wild capuchin foods. Instead, the two grit sizes were selected to bracket the extremes of size variation of sand. The concentration of grit within the biscuits and gummies (10% by weight) is based on previous experimental grit studies (e.g., Covert and Kay, 1981). We also did not want to destabilize the recipes or impact taste too much by including an excessive amount of grit. Capuchins UC-A and UC-C were given biscuits and gummies laced with fine sand, and capuchin UC-L was given biscuits and gummies with coarse sand.

2.4. Anesthesia

The animals were not fed for 18 hours before each anesthesia. Impression sessions averaged approximately 45–60 minutes, during which each animal was sedated and monitored (Theriault, Reed, and Niekrasz, 2008). After the molding procedures, animals recovered to the point that they were alert, maintained a normal sitting posture, and readily took food in less than an hour after discontinuing anesthesia. All animals made a full recovery.

2.5. Dental impression protocol

For each experiment, with the animals anesthetized, a small gape block was placed between the upper and lower canines on one side of the mouth to keep the mouth open. As organic films on the teeth are a constant problem in such studies (Teaford et al., 2020), the teeth were cleaned with a toothbrush and (a) dilute (10%) bleach solution, (b) a dilute solution of lime juice (also 10%), and (c) “Colgate” toothpaste. This was followed by 2 minutes of cleaning with a water-pik. The teeth then were dried for 2–3 minutes using an air pump before impressions were taken with Coltene-Whaledent’s “President Jet Regular Body” polyvinylsiloxane. Within two weeks, impressions were gently swabbed with the dilute bleach solution and air-dried for 2 days (to remove any remnants of organic film inside the molds). The molds were then poured with Epotek 301 cold-cure epoxy, and the epoxy was centrifuged into the molds to eliminate bubbles on cusp tips. The filled impressions were left at room temperature for one week to allow the epoxy to fully cure before the casts were removed from the molds, and then attached to standard aluminum pin-type mounts for scanning electron microscopy.

2.6. Scanning electron microscopy and computations of rates of microscopic wear

As with previous analyses of rates of microscopic wear (Janal et al., 2007; Raphael, Marbach, and Teaford, 2003; Romero et al., 2012; Teaford and Glander, 1991, 1996; Teaford and Lytle 1996; Teaford and Oyen, 1989a; Teaford and Tylenda, 1991; Teaford et al., 2017, 2020), epoxy casts of the molars were examined at a magnification of 200X in a scanning electron microscope (a Philips XL30 at the University of California at Davis Biological Electron Microscopy Facility). Given previous difficulties in obtaining clean enamel surfaces (e.g., Teaford et al., 2017, 2020), upper and lower molars were both examined whenever possible, as were the first, second, and third molars, with the goal of obtaining as many usable surfaces as possible from shearing and crushing facets. As with previous studies (Teaford et al., 2017, 2020), strict adherence to 18 hours between feeding and impression sessions left some teeth unusable due to the accumulation of organic films on their surfaces. Thus, we used whichever crushing and shearing surfaces on whichever molars were feasible.

Micrographs of the same areas on the same tooth were taken from baseline and follow-up casts of each animal (see Teaford et al., 2017, 2020 for more detailed description of the methods). The baseline and follow-up images were then imported into Photoshop (Adobe, Inc.), together with an image of a reference grid. The follow-up images and the reference grid were placed in layers on top of the baseline image, so that the follow-up image could be positioned optimally for visual comparison of its microwear features with those in the baseline image (using the reference grid merely as an aid to positioning and to subdivide the total image into a series of smaller squares). The number of features in each square of the follow-up micrograph was counted (including pits and scratches), and the number of “new” features that had appeared as a result of the feeding experiment was noted. Thus, in all cases, the key variable calculated was the percentage of features in the follow-up micrograph caused during that feeding experiment [(# new features in image / total # features in image) × 100]. This percentage of new features was calculated separately for crushing facets and for shearing facets. If calculations were made for more than one tooth for an individual, the total number of new features on images of crushing facets was divided by the total number of features on those same images to yield a summary percentage of new features for the crushing facets of that individual resulting from that feeding experiment. The same calculation was made for shearing facets for each individual.

Two key points need to be emphasized here. First, while the total number of features is always counted in the follow-up micrographs, the bulk of those features are created before the baseline impression was taken. In other words, they can be seen in both the baseline and follow-up micrographs. Thus, the crucial point is not the total number of features present, but instead the number of new features that were created during the feeding experiment. Second, while it would be ideal to compare precisely the same areas between baseline, first experiment, and second experiment (e.g., Figure 3), that is often not possible due to the difficulties of taking impressions from live animals. Thus, the gross number of features per micrograph cannot be usefully compared between micrographs, and it is the proportion of new features that is compared between facets and between experimental groups.

Figure 3.

New features created during the consumption of biscuits (red boxes in “experiment 1” micrograph compared with “baseline” micrograph), and gummies (yellow boxes in “experiment 2” micrograph compared with “experiment 1” micrograph).

As with our previous studies (Teaford et al., 2017, 2020), this admittedly limits the resolution of some interpretations (i.e., we cannot yet provide contrasts between the different molars along the tooth row). However, the method does allow the monitoring of microscopic changes on the tooth surface on a day-to-day basis, and it has been shown to accurately track more traditional macroscopic measures of rates of tooth wear like changes in molar cusp height (Teaford and Oyen, 1989b).

2.7. Preliminary statistical comparisons of rates of microscopic wear

We fit a linear mixed model to initially assess factors potentially impacting microwear formation. We considered percentage of new features as a dependent variable, while facet surface (crushing vs. shearing) and grit (fine vs. coarse) were treated as fixed effects. Individual monkey was included as a random effect and estimates of microwear on each tooth considered as individual data points. We created separate models for biscuits and gummies. Models were generated in R (R Core Team, 2020) using the lme4 package (Bates et al. 2015), where each model could be conceived as:

| (1) |

Subsequent power estimates for fixed effects were simulated in simr (Green and MacLeod, 2016).

3. Results

3.1. Feeding preferences

Animals fed biscuits containing sand-size abrasives (UC-A and UC-C) ate more of those biscuits than did the animal fed biscuits containing the larger-grained abrasives (UC-L) (Table 1). There was no such difference in feeding preference when the animals were fed gummies (Table 1).

Table 1.

Number of Biscuits and Gummies Consumed by Each Monkey

| Monkey | Grit Size | # Biscuits Consumed | # Gummies Consumed |

|---|---|---|---|

| UC-A (“Atropos”) | Small sand (180μ) | 19 | 9 |

| UC-C (“Clotho”) | Small sand (180μ) | 27 | 8 |

| UC-L (“Lachesis”) | Coarse sand (1400 μ) | 2 | 8 |

3.2. Experiment 1

In the first experiment, in which animals were fed biscuits, the rate of microscopic wear showed an association with the number of biscuits consumed, but the few biscuits with the coarse sand abrasives resulted in a disproportionately high rate of microwear in the animal that only consumed two biscuits (Table 2, Figure 1).

Table 2.

Number of Features, Number of New Features, and Percentage of New Features on Molars of Monkeys in Experiment 1 - Biscuits

| Monkey | # Items Consumed | Total # Features | # New Features | % New Features | % of new features per item consumed |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Experiment one - Biscuits | |||||

| UC-A Fine-sand crushing facets | 19 | ||||

| M1 | 478 | 255 | |||

| M2 | 360 | 140 | |||

| M1 | 196 | 56 | |||

| TOTALS | 1034 | 451 | 43.6% | 2.29% | |

| UC-A Fine-sand shearing facets | 19 | ||||

| M1 | 556 | 138 | |||

| M1 | 1054 | 124 | |||

| M2 | 293 | 77 | |||

| TOTALS | 1903 | 339 | 17.8% | 0.94% | |

| UC-C Fine-sand crushing facets | 27 | ||||

| M1 | 82 | 33 | |||

| M2 | 296 | 168 | |||

| M1 | 159 | 69 | |||

| M2 | 154 | 68 | |||

| TOTALS | 691 | 338 | 48.9% | 1.81% | |

| UC-C Fine-sand shearing facets | 27 | ||||

| M1 | 827 | 314 | |||

| M2 | 843 | 353 | |||

| M3 | 285 | 78 | |||

| M1 | 228 | 74 | |||

| M2 | 166 | 101 | |||

| TOTALS | 2349 | 920 | 39.2% | 1.45% | |

| UC-L Coarse-sand crushing facets | 2 | ||||

| M1 | 231 | 49 | |||

| M2 | 218 | 44 | |||

| M1 | 217 | 61 | |||

| M2 | 261 | 29 | |||

| TOTALS | 927 | 183 | 19.7% | 9.85% | |

| UC-L Coarse-sand shearing facets | 2 | ||||

| M1 | 540 | 88 | |||

| M1 | 809 | 123 | |||

| M3 | 371 | 44 | |||

| TOTALS | 1720 | 255 | 14.8% | 7.4% |

Figure 1.

Rates of microscopic wear on the molars of laboratory capuchin monkeys fed biscuits laced with either smaller- (180 μ) or larger-grained (1400 μ) abrasives.

3.3. Experiment 2

In the second experiment, in which animals were fed gummies, the rate of microscopic wear was lower than that for the consumption of biscuits, and it did not seem to relate to the number of gummies consumed; for example, UC-A consumed one more gummy than did UC-C or UC-L, yet UC-A had far more new microwear features than did either of the other monkeys (Table 3, Figure 2).

Table 3.

Number of Features, Number of New Features, and Percentage of New Features on Molars of Monkeys in Experiment 2 - Gummies

| Monkey | # Items Consumed | Total # Features | # New Features | % New Features | % of new features per item consumed |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Experiment 2 - Gummies | |||||

| UC-A Fine-sand crushing facets | 9 | ||||

| M1 | 653 | 248 | |||

| M2 | 182 | 47 | |||

| M1 | 202 | 41 | |||

| TOTALS | 1037 | 336 | 32.4% | 3.6% | |

| UC-A Fine-sand shearing facets | 9 | ||||

| M1 | 807 | 123 | |||

| M2 | 579 | 122 | |||

| M2 | 323 | 14 | |||

| TOTALS | 1709 | 259 | 15.2% | 1.69% | |

| UC-C Fine-sand crushing facets | 8 | ||||

| M1 | 274 | 3 | |||

| M2 | 354 | 42 | |||

| TOTALS | 628 | 45 | 7.2% | 0.9 % | |

| UC-C Fine-sand shearing facets | 8 | ||||

| M1 | 612 | 12 | |||

| M2 | 382 | 7 | |||

| M3 | 182 | 9 | |||

| M1 | 168 | 7 | |||

| TOTALS | 1344 | 35 | 2.6% | 0.325% | |

| UC-L Coarse-sand crushing facets | 8 | ||||

| M1 | 204 | 11 | |||

| TOTALS | 204 | 11 | 5.4% | 0.675% | |

| UC-L Coarse-sand shearing facets | 8 | ||||

| M1 | 561 | 93 | |||

| M2 | 193 | 43 | |||

| TOTALS | 754 | 136 | 18.0% | 2.25% |

Figure 2.

Rates of microscopic wear on the molars of laboratory capuchin monkeys fed gummies laced with either smaller- (180 μ) or larger-grained (1400 μ) abrasives.

3.4. Statistical comparisons between facets and grit sizes.

In Experiment 1, crushing facets exhibited significantly more new features than shearing facets (i.e., when processing biscuits) (t=2.35, df=18, p=0.03), while differences in grit size only approached significance (t=1.83, df=18, p=0.08) in the linear mixed model. Alternatively, in Experiment 2, gummy processing evinced no differences in percentages of new features created on facets (t=1.12, df=11, p=0.29) or with different grit sizes (t=0.18, df=11, p=0.85). It is important to recognize the preliminary nature of these results as power for grit differences was less than 0.2 for biscuits and similarly low (<0.2) for both fixed effects in the gummies model.

3.5. Microwear created in both experiments

Both food items and both grit sizes created a wide range of microwear sizes and shapes (Figure 3). In other words, neither combination of food item and abrasive seemed to cause one specific type of microwear feature. Clearly, further dental microwear texture analyses are needed to better document any potential microwear “texture” changes in these types of experiments.

4. Discussion

These results further demonstrate that feeding on artificial foods laced with abrasives can create dental microwear (Puech and Prone 1979; Peters, 1982; Hua et al., 2015). However, these results also show that the process is complicated.

4.1. Feeding preferences

In experiment one (biscuits laced with different abrasives), far fewer of the biscuits made with the larger-grained abrasives were consumed by the animal to which they were offered. Obviously, given the extremely small sample sizes (i.e., one animal fed larger-grained abrasives, and two animals fed smaller-grained abrasives), these results are only suggestive. For instance, it would be informative to know how each animal would respond if they were each given the chance to feed on foods laced with large- and small-grained abrasives. Even so, this seems to echo recent observations that some animals may tend to avoid food items laced with abrasives, be they exogenous (Ackermans et al., 2019; Laird et al., 2019; Venkataraman et al., 2019) or endogenous (Gali-Muhtasib and Smith, 1992; Cotterill et al., 2007; Massey et al., 2007). The fact that such a distinction was not observed in experiment 2 (the one using gummies laced with different abrasives), suggests that there might be a combination of both a threshold of grit size / concentration and food stiffness below which abrasives are not detected or avoided. However, as the threshold for particle size detection between the teeth is often quoted as between 12 and 14 μm (Prinz, 2004; Enkling et al., 2010), and the smallest abrasive particles used in this study were 180 μm, one might hypothesize that food stiffness played a significant role in grit detection in this study. In other words, in experiment 1, where the animals were fed a stiffer food (biscuits), the animal fed food laced with coarse sand ate far fewer of them than did the animals eating food laced with fine sand. However, in experiment 2, where the animals were fed a more ductile food (gummies), all three animals ate roughly the same number of food items.

4.2. Rates of dental microwear in biscuits laced with abrasives of different sizes

At first glance, the results from experiment one might be used to suggest that rate of dental microscopic wear feature formation is roughly related to the number of biscuits consumed. However, if the percentage of new features for each of the three monkeys is divided by the number of biscuits consumed by each of those monkeys, then the two biscuits with the coarse sand consumed by UC-L had a relatively greater impact on the rate of dental microwear formation (for that individual in that experiment) as compared with the biscuits laced with fine sand consumed by the other two monkeys (see Figure 4 and Table 2). Could this reflect an individual-specific difference in jaw movements and/or applied forces associated with the processing of foods laced with larger-grained abrasives, or is there something about the size/shape/angularity of the larger-grained abrasives that might be facilitating the marking of enamel under these circumstances? Only further work will tell. The fact that all three animals showed faster rates of dental microwear on their crushing facets (as compared with their shearing facets) mirrors results previously obtained for human dental patients and laboratory vervet monkeys (Teaford and Oyen, 1989; Teaford and Tylenda, 1991). It is perhaps not surprising, as one might expect the processing of this stiff, brittle food to involve a fair amount of crushing.

Figure 4.

Relative rates of microscopic wear (i.e., % new features / # items consumed) for laboratory capuchin monkeys fed biscuits laced with either smaller- (180 μ) or larger-grained (1400 μ) abrasives.

4.3. Rates of dental microwear in gummies laced with abrasives of different sizes

The rate of microscopic wear for the consumption of gummies was generally not as high as that for the consumption of biscuits (compare figures 1 and 2). There was also no apparent relation between the number of gummies consumed and the rate of dental microwear. In fact, the contrast in rate of dental microwear for UC-A, on the one hand, and UC-C and UC-L on the other, might suggest that there might be differences in food processing between the animals in this study, with UC-A perhaps using more chews to process each food item than the other two monkeys. Anecdotal evidence indicates that all three animals spent more time processing biscuits than gummies. From that perspective, perhaps it is not surprising that there was relatively little difference in the relative impact (on rates of dental microwear) of gummies laced with larger- versus smaller-grained abrasives (Figure 5). This may reinforce the idea that the oral processing of relatively ductile foods (perhaps through less time spent chewing) minimizes the impact (on rates of dental microwear) of abrasives of different sizes. Of course, it remains to be seen if this can be found for other ductile foods, as any such differences in food processing time could be due to any number of additional related factors – e.g., the adhesiveness or springiness of the food, or the swallowing threshold for the food. Interestingly, while the monkeys fed gummies laced with fine sand showed the same pattern as in experiment one with crushing facets showing a faster rate of microscopic wear than shearing facets, those results were reversed for the monkey fed gummies laced with coarse sand. More feeding episodes from a greater number of animals are clearly needed.

Figure 5.

Relative rates of microscopic wear (i.e., % new features / # items consumed) for laboratory capuchin monkeys fed gummies laced with either smaller- (180 μ) or larger-grained (1400 μ) abrasives.

4.4. Types of microwear created in both experiments

Granted, an obvious sequel to this study would be to include analyses of dental microwear texture before and after each of the feeding experiments. Even so, the range of dental microwear features caused in both experiments suggests that dental microwear patterns caused exclusively by “grit” load will not necessarily be recognizable as something distinctive from those caused by food material properties. Of course, this is also dependent on what type of diet and grit is being orally processed. Based on the results of this study, it remains plausible that food material properties, and their associated differences in feeding behavior, will channel the effects of abrasives in a way that will cause microwear “reflective of diet” (Hedberg and DeSantis, 2017), especially for relatively invariable diets in the wild or diets that involve repeated feedings on the same items for long periods. If this is the case, untangling the independent effects of behavior and FMPs will be challenging and also require additional experimental work on larger samples of individuals.

4.5. Rates of dental microwear in this study and other similar studies of different populations

While recent studies based on similar methods (Teaford et al., 2017, 2020) did not focus on differences between crushing and shearing facets, comparisons of the overall rates of microscopic wear (computed across all teeth analyzed for each animal) provide some additional insights about the impact of abrasives of different sizes, and foods of different properties, on rates of dental microwear. If, as a starting point, we assume that the 36-hour feeding sessions in the present study yield approximately 21.4% of a week’s feeding (i.e., 1.5 days/ 7 days), then we can calculate weekly rates of microscopic wear for feeding on biscuits vs. gummies, on the one hand, and for feeding on foods laced with large-grained vs. small-grained abrasives, on the other. Granted, such calculations, on such small sample sizes, are not without their short-comings. However, a few points still seem worth mentioning.

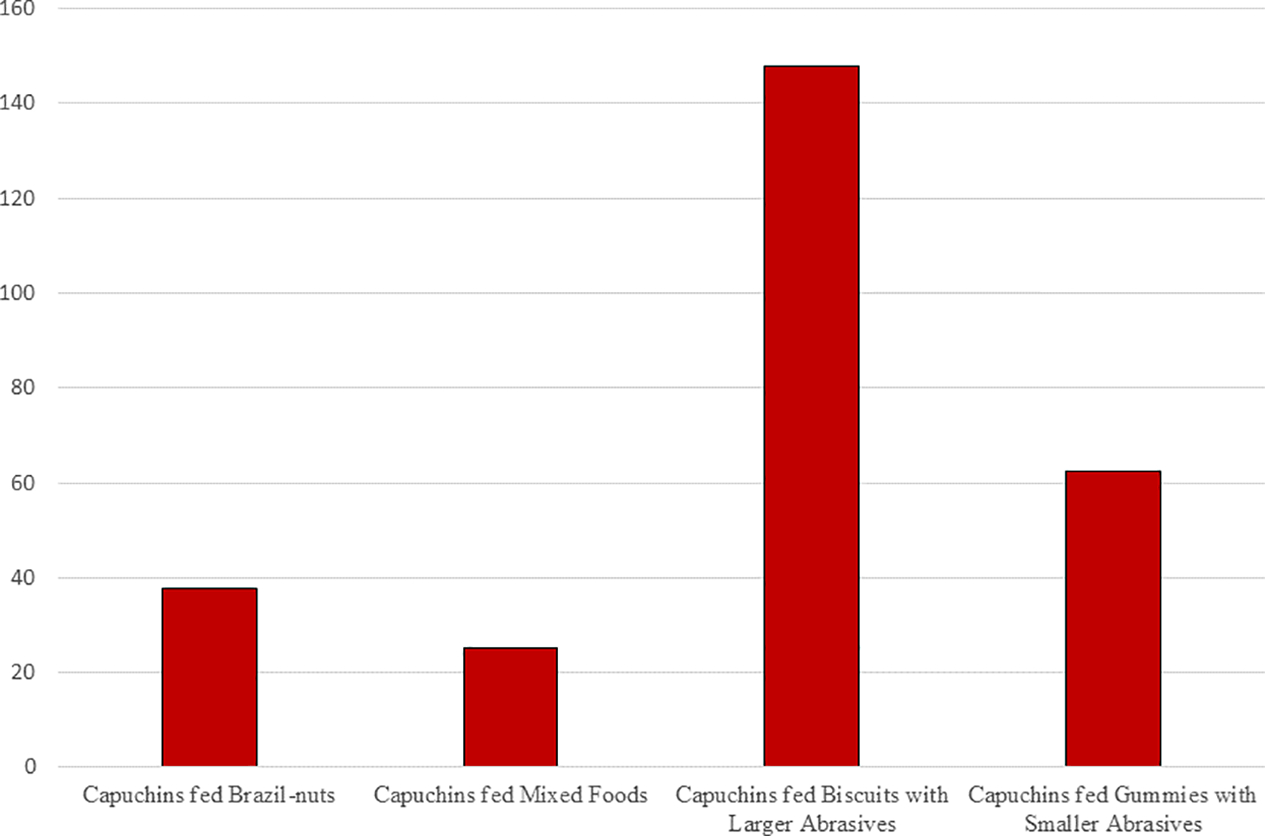

For the consumption of biscuits or gummies in the present study, rates of microscopic wear were faster than those calculated in the previous studies for either the consumption of Brazil nuts or a “mixed” sample of foods (see Figure 6). Also, the rates of microscopic wear for the consumption of biscuits were faster than those calculated for gummies (Figure 6). The former difference is probably just a reaffirmation of previously-published findings that the inclusion of exogenous grit into food can yield rapid rates of enamel wear (e.g., Karme et al., 2016), whereas the difference between biscuits and gummies probably reflects the increased time spent processing the former while also perhaps reinforcing the idea that food material properties can influence the impact of exogenous grit on rates of enamel wear (Hua et al., 2015), e.g., abrasive particles being pushed into the gummies by the forces applied in chewing, but abrasives being pushed into the enamel in the processing of the stiffer biscuits.

Figure 6.

Estimated weekly rates of microscopic wear on the molars of laboratory capuchin monkeys fed either Brazil nuts or Mixed Foods (from Teaford et al., 2017, 2020) and Biscuits or Gummies laced with either smaller- (180 μ) or larger-grained (1400 μ) abrasives (from the present study).

For the consumption of foods laced with large-grained versus smaller-grained abrasives, again, the results show faster rates of microscopic wear than those previously-documented for the consumption of Brazil nuts or a “mixed” sample of foods (Figure 7). However, the faster rate of wear obtained for the consumption of food laced with the smaller-grained abrasives is unexpected and may primarily reflect the fact that the one monkey that was offered foods laced with larger-grained abrasives consumed far fewer biscuits than did the monkeys offered biscuits laced with smaller-grained abrasives. This would imply that the relatively slower rate of microwear for the foods laced with larger-grained abrasives actually reflects significantly less time spent consuming those foods. In support of this interpretation, if the number of new features (caused by foods laced with larger- versus smaller-grained abrasives) is divided by the number of food items consumed, the foods with the large-grained abrasives yielded relatively more new features when compared with the foods with the smaller-grained abrasives (1.78% vs. 0.42%).

Figure 7.

Estimated weekly rates of microscopic wear on the molars of laboratory capuchin monkeys fed either Brazil nuts or Mixed Foods (from Teaford et al., 2017, 2020) and foods laced with either Smaller- (180 μ) or Larger-grained (1400 μ) abrasives (from the present study).

5. Conclusions

While the sample sizes in this study are small enough to yield suggestive results at best, and the foods being processed are certainly not “natural” foods for the animals being investigated, the dental processing of the foods and abrasives in this study still seemed to cause a range of microwear features relatively rapidly. Moreover, the rate of dental microwear formation seems to be dictated by other factors as well, most notably the physical properties of the foods being processed - as harder/stiffer foods (i.e., biscuits) yielded faster rates of microwear formation than did softer/ductile foods (i.e., gummies) - and the number of chewing cycles - as animals seemed to use more chewing cycles in processing the biscuits. Of course, while this study documents differences in the creation of new microwear features on the teeth of monkeys fed different foods and abrasives, it tells us nothing about the impact of the appearance and disappearance of those features on dental microwear textures (i.e., the measurements most commonly-used in analyses of fossil material). Even if the abrasives used in this study cause a faster rate of microscopic wear than the foods tested in previous studies, these results cannot validate or invalidate observations that variation in microwear texture patterns yield useful dietary signals. This study does reinforce the idea that the impact of food and grit on dental microwear is the result of a dynamic, complex interaction among many factors including food material properties, grit load, masticatory morphology, and oral processing. It also highlights the need for longer-term analyses of larger sample sizes, using a wider range of foods and grit, to better document the effects of food and grit combinations on microwear generation. Still, despite its limitations, this study should help to lay the groundwork for further laboratory studies, while also ultimately helping to refine interpretations of fossil material.

Highlights:

Feeding choices made by laboratory monkeys are impacted by a combination of the size of the abrasives in the food and the physical properties of those foods.

The mastication of either hard brittle biscuits or ductile gummies laced with large- or small-grained abrasives led to the formation of a variety of dental microwear features.

Rates of dental microscopic wear were higher when animals consumed biscuits as opposed to gummies.

Rates of dental microscopic wear were highest when animals fed on biscuits laced with large-grained abrasives.

Acknowledgements

This work was funded by the NSF Anthropology, HOMINID, and Major Research Instrumentation programs, including BCS-0552285, BCS 0504685, BCS 0725126, BCS 0725147, BCS 0962682, MRI 1338066, and NIH R01 OD023831-04S1, and an AAPA Cobb Award. Special thanks also go to the University of Chicago Animal Resource Center where all the live animal work was done and the Electron Microscopy Core Laboratory at the UC Davis School of Medicine where the SEM-work was completed. The help of Marek Niekrasz, Alyssa Brown, and Jennifer McGrath is particularly appreciated.

Footnotes

Because all animals were fed ad libitum, we were unable to monitor number of chews or the precise time spent feeding in these experiments.

Declaration of interests

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- Ackermans NL, Martin LF, Hummel J, Müller DWH, Clauss M, Hatt J-M (2019). Feeding selectivity for diet abrasiveness in sheep and goats. Small Rum. Res. 175, 160–164. [Google Scholar]

- Agrawal KR, Lucas PW, Bruce IC, & Prinz JF (1998). Food properties that influence neuromuscular activity during human mastication. J. Dent. Res. 77, 1931–1938. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Agrawal KR, Lucas PW, Bruce IC (2000). The effects of food fragmentation index on mandibular closing angle in human mastication. Arch. Oral Biol. 45, 577–584. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ahlgren J (1976). Masticatory movements in man. In: Mastication, Anderson DJ and Matthews B, eds, Bristol: John Wright and Sons, pp. 119–130. [Google Scholar]

- Aiba K, Miura S, Kubo MO (2019). Dental microwear texture analysis in two ruminants, Japanese serow (Capricornis crispus) and sika deer (Cervus nippon), from central Japan Mammal Study 44, 183–192 DOI: 10.3106/ms2018-0081 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Allritz M, Tennie C, Call J (2013). Food washing and placer mining in captive great apes. Primates 54, 361–370. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Anderson K, Throckmorton GS, Buschang PH, Hayasaki H (2002). The effects of bolus hardness on masticatory kinematics. J. Oral Rehab. 29, 689–696. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bates D, Mächler M, Bolker B, Walker S. (2015). Fitting linear mixed-effects models using lme4. J. Statist. Software 67, 1–48. doi: 10.18637/jss.v067.i01. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Borrero-Lopez O, Pajares A, Constantino PJ, Lawn BR (2015). Mechanics of microwear traces in tooth enamel. Acta Biomat. 14, 146–153. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cotterill JV, Watkins RW, Brennon CB, Cowan DP (2007). Boosting silica levels in wheat leaves reduces grazing by rabbits. Pest. Manag. Sci. 63, 247–253. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Daegling DJ, Grine FE (1999). Terrestrial foraging and dental microwear in Papio ursinus. Primates 40, 559–572. [Google Scholar]

- Daegling DJ, Judex S, Ozcivici E, Ravosa MJ, Taylor AB, Grine FE, Teaford MF, Ungar PS (2013). Feeding mechanics, diet and dietary adaptations in early hominins. Am. J. Phys. Anthropol, 151, 356–371. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Daegling DJ, Hua L-C, Ungar PS (2016). The role of food stiffness in dental microwear feature formation. Arch. Oral Biol. 71, 16–23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Enkling N, Nocilay C, Bayer S, Mericske-Stern R, Utz K-H (2010). Investigating interocclusal perception in tactile teeth sensibility using symmetric and asymmetric analysis. Clin. Oral Invest. 14, 683–690. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Foster KD, Woda A, Peyron MA (2006). Effect of texture of plastic and elastic model foods on the parameters of mastication. J. Neurophys. 95, 3469–3479. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gali-Muhtasib HU, Smith CC (1992). The effect of silica in grasses on the feeding behavior of the prairie vole, Microtus ochrogaster. Ecol. 73, 1724–1729. [Google Scholar]

- Galbany J, Romero A, Mayo-Alesón M, Itsoma F, Gamarra B, Pérez-Pérez A, Willaume E, Kappeler PM, Charpentier MJE (2014). Age-related tooth wear differs between forest and savanna primates. PLoS ONE 9(4): e94938. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0094938 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gallego-Valle A, Colominas L, Burguet-Coca A, Aguilera M, Palet J-M, Tornero C (2020) What is on the menu today? Creating a microwear reference collection through a controlled-food trial to study feeding management systems of ancient agropastoral societies Quat. Int. doi: 10.1016/j.quaint.2020.02.020. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Geissler E, Daegling DJ, McGraw WS (2018). Forest floor leaf cover as a barrier for dust accumulation in Tai National Park: Implications for primate dental wear studies. Int. J. Primtol. 39, 633–645. [Google Scholar]

- Gibbs CH, Lundeen HC, Mahan PE, Fujimoto J (1981). Chewing movements in relation to border movements at the first molar. J. Prosth. Dent. 46, 308–322. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gibbs CH, Wickwire NA, Jacobson AP, Lundeen HC, Mahan PE, Lupkiewicz SM (1982). Comparison of typical chewing patterns in normal children and adults. J. Am. Dent. Assoc. 105, 33–42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gordon KD (1984). Orientation of occlusal contacts in the chimpanzee, Pan troglodytes verus, deduced from scanning electron microscopic analysis of dental microwear patterns. Arch. Oral Bio. 29, 783–787. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Green P, MacLeod CJ (2016). simr: an R package for power analysis of generalised linear mixed models by simulation. Meth. Ecol. Evol. 7, 493–498. doi: 10.1111/2041-210X.12504, https://CRAN.R-project.org/package=simr. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Greet DG, De Vree F (1984). Movements of the mandibles and tongue during mastication and swallowing in Pteropus giganteus (Megachiroptera): A cineradiographical study. J. Morphol. 179, 95–114. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gügel IL, Grupe G, Kunzelmann KH (2001). Simulation of dental microwear: characteristic traces by opal phytoliths give clues to ancient human dietary behavior. Am. J. Phys. Anthropol. 114, 124–138. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hedberg C, DeSantis LRG (2017). Dental microwear texture analysis of extant koalas: clarifying causal agents of microwear. J. Zool. 301, 206–214. [Google Scholar]

- Hiiemae KM, Heath MR, Heath G, Kazazoglu E, Murray J, Sapper D, Hamblett K (1996). Natural bites, food consistency and feeding behaviour in man. Arch. Oral Biol. 41, 175–89. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Horio T, Kawamura Y (1989). Effects of texture of food on chewing patterns in the human subject. J. Oral. Rehab. 16, 177–183. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hua LC, Brandt ET, Meullenet JF, Zhou ZR, Ungar PS (2015). Technical note: An in vitro study of dental microwear formation using the BITE Master II chewing machine. Am. J. Phys. Anthropol. 158, 769–775. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hua LC, Chen J, Ungar PS (2020). Diet reduces the effect of exogenous grit on tooth microwear. Biosurf. & Biotribol. 6, 48–52 [Google Scholar]

- Hylander WL, Johnson KR (1994). Jaw muscle function and wishboning of the mandible during mastication in macaques and baboons. Am. J. Phys. Anthropol. 94, 523–547. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Iriarte-Diaz J, Reed DA, Ross CF (2011). Sources of variance in temporal and spatial aspects of jaw kinematics in two species of primates feeding on foods of different properties. Integr. Comp. Biol. 51, 307–319. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Janal MN, Raphael KG, Klausner J, Teaford MF (2007). The role of tooth-grinding in the maintenance of myofascial face pain: A test of alternate models. Pain Med. 8, 486–496. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Karme A, Rannikko J, Kallonen A, Clauss M, Fortelius M (2016). Mechanical modelling of tooth wear. J. Roy. Soc. Interface 13, 20160399. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kawamura S (1959). The process of sub-culture propogation among Japanese macaques. Primates 2, 43–60. [Google Scholar]

- Covert HH, & Kay RF (1981). Dental microwear and diet: implications for determining the feeding behaviors of extinct primates, with a comment on the dietary pattern of Sivapithecus. Am. J. Phys. Anthropol. 55, 331–336. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Laird MF (2017). Variation in human gape cycle kinematics and occlusal topography. Am. J. Phys. Anthropol. 164, 574–585. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Laird MF, Granatosky MC, Ross CF (2019). The influence of dietary grit on capuchin feeding behavior. Am. J. Phys. Anthropol. 168(S68), 135. [Google Scholar]

- Laird MF, Ross CF, O’Higgins P (2020a). Jaw kinematics and mandibular morphology in humans. J. Hum. Evol. 139, 102639. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Laird MF, Granatosky MC, Taylor AB, Ross CF (2020b). Muscle architecture dynamics modulate performance of the supertficial anterior temporalis muscle during chewing in capuchins. Sci. Rep. 10, 6410 doi.org/ 10.1038/s41598-020-63376-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lucas PW, Omar R, Al-Fadhalah K, Almusallam AS, Henry AG, Michael S, Thai LA, Watzke J, Strait DS, Atkins AG (2013). Mechanisms and causes of wear in tooth enamel: implications for hominin diets. J.Roy. Soc. Interface 10, 20120923. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Massey FP, Ennos AR, Hartley SE (2007). Grasses and the resource availability hypothesis: The importance of silica-based defenses. J. Ecol. 95, 414–424. [Google Scholar]

- Merceron G, Ramdarshan A, Blondel C, Boisserie J-R, Brunetiere N, Francisco A, Gautier D, Milhet X, Novello A, Pret D (2016). Untangling the environmental from the dietary: dust does not matter. Proc. R. Soc. B 283, 20161032. doi: 10.6084/m9.figshare.c.3461769 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Merceron G, Colyn M, Geraads D (2018). Browsing and non-browsing extant and extinct giraffids: Evidence from dental microwear textural analysis. Palaeog., Palaeoclim, Palaeoecol. 505, 128–139. [Google Scholar]

- Mioche L, Bourdiol P, Martin J-F, Noël Y (1999). Variation in human masseter and temporalis muscle activity related to food texture during free and side-imposed mastication. Arch. Oral Biol. 44, 1005–1012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nystrom P, Phillips-Conroy JE, Jolly CJ (2004). Dental microwear in Anubis and hybrid baboons (Papio hamadryas, sensu lato) living in Awash National Park, Ethiopia, Am. J. Phys. Anthropol. 125, 279–291. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oron U, Crompton AW (1985). A cineradiographic and electromyographic study of mastication in Tenrec ecaudatus. J. Morphol. 185, 155–82 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Percher AM, Merceron G, Akoue GN, Galbany J, Romero A, Charpentier MJE (2018). Dental microwear textural analysis as an analytical tool to depict individual traits and reconstruct the diet of a primate. Am. J. Phys. Anthropol. 165,123–138. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peters CR (1982). Electron-optical microscopic study of incipient dental microdamage from experimental seed and bone crushing. Am. J. Phys. Anthropol. 57, 283–301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peyron MA, Maskawi K, Woda A, Tanguay R, Lund JP (1997). Effects of food texture and sample thickness on mandibular movement and hardness assessment during biting in man. J. Dent. Res. 76, 789–95. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peyron MA, Lassauzay C, Woda A (2002). Effects of increased hardness on jaw movement and muscle activity during chewing of visco-elastic model foods. Exp. Brain Res. 142, 41–51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prinz JF (2004). Abrasives in foods and their effect on intra-oral processing: a two-colour chewing gum study. J. Oral Rehab. 31, 968–971. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pröschel P, Hofmann M (1988). Frontal chewing patterns of the incisor point and their dependence on resistance of food and type of occlusion. J. Prosth. Dent. 59, 617–624. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Puech P-F, Prone A (1979). Reproduction expérimentale des processus d’usure dentaire par abrasion: implications paléoécologiques chez l’Homme fossile. C.R. Acad., Sci, Paris 289, 895–898. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- R Core Team (2020). R: A language and environment for statistical computing. Vienna, Austria, R Foundation for Statistical Computing, URL https://www.R-project.org/. [Google Scholar]

- Raphael K, Marbach J, Teaford MF (2003). Is bruxism severity a predictor of oral splint efficacy in patients with myofascial face pain? J. Oral Rehab. 30, 17–29. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reed DA, Ross CF (2010). The influence of food material properties on jaw kinematics in the primate, Cebus. Arch. Oral Biol. 55, 946–962. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Romero A, Galbany J, De Juan J, Pérez-Pérez A (2012). Brief communication: Short- and long-term in vivo human buccal-dental microwear turnover. Am. J. Phys. Anthropol. 148, 467–472. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rosien JE, Dominy NJ, Malaivijitnond S, Tan AWY (2019). Mechanisms for avoiding sandlaiden foods in a population of coastal foraging monkeys (Macaca fascicularis). Am. J. Phys. Anthropol. 168(S68), 208. [Google Scholar]

- Ross CF, Iriarte-Diaz J (2014). What does feeding system morphology tell us about feeding? Evol. Anthropol. 23, 105–120. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ross CF, Iriarte-Diaz J (2019). Evolution, constraint and optimality in primate feeding systems, in: Bels V, Whishaw IQ (Ed.), Feeding In Vertebrates. Springer Nature Switzerland AG, pp. 787–828. [Google Scholar]

- Ross CF, Iriarte-Diaz J, Reed DA, Stewart TA, Taylor AB (2016). In vivo bone strain in the mandibular corpus of Sapajus during a range of oral food processing behaviors. J. Hum. Evol. 98, 36–65. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sanson GD, Kerr SA, Gross KA (2007). Do silica phytoliths really wear mammalian teeth? J. Archaeol. Sci. 34, 526–531. [Google Scholar]

- Sanson GD, Kerr S, Read J (2017). Dietary exogenous and endogenous abrasives and tooth wear in African buffalo. Biosurf. & Biotribol. 3, 211–223 [Google Scholar]

- Schulz E, Piotrowski V, Clauss M, Mau M, Merceron G, Kaiser TM (2013). Dietary abrasiveness is associated with variability of microwear and dental surface texture in rabbits. PLoS ONE 8, e56167. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schulz-Kornas E, Struhlträger J, Clauss M, Wittig RM, Kupczik K (2019). Dust affects chewing efficiency and tooth wear in forest dwelling Western chimpanzees (Pan troglodytes verus). Am. J. Phys. Anthropol. 169, 66–77. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Simpson GG (1933). The” Plagiaulacoid” Type of Mammalian Dentition A Study of Convergence. J. Mammal. 14, 97–107. [Google Scholar]

- Simpson GG (1936). Studies of the earliest mammalian dentitions. Dent. Cosmos, 78, 940–953. [Google Scholar]

- Solounias N, Teaford MF, Walker A (1988). Interpreting the diet of extinct ruminants: the case of a non-browsing giraffid. Paleobiol. 14, 287–300. [Google Scholar]

- Sommer V, Lowe A, Dietrich T (2016). Not eating like a pig: European wild boar wash their food. Anim. Cogn. 19, 245–249. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Strait DS, Constantino P, Lucas PW, Richmond BG, Spencer MA, Dechow PC, Ross CF, Grosse IR, Wright BW, Wood BA, Weber GW, Wang Q, Byron C, Slice DE, Chalk J, Smith AL, Smith LC, Wood S, Berthaume M, Benazzi S, Dzialo C, Tamvada K, Ledogar JA (2013). Diet and dietary adaptations in early hominins: the hard food perspective. Am. J. Phys. Anthropol. 151, 339–355. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stuhlträger J, Schulz-Kornas E, Wittig RM, Kupczik K (2019). Ontogenetic dietary shifts and microscopic tooth wear in western chimpanzees. Front. Ecol. Evol. 7, 298. [Google Scholar]

- Takada K, Miyawaki S, Tatsuta M (1994). The effects of food consistency on jaw movement and posterior temporalis and inferior orbicularis oris muscle activities during chewing in children. Arch. Oral Biol. 39, 793–805. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Teaford MF, Glander KE (1991) Dental microwear in live, wild-trapped Alouatta palliata from Costa Rica. Am. J. Phys. Anthropol. 85, 313–319. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Teaford MF, Glander KE (1996). Dental microwear and diet in a wild population of mantled howling monkeys (Alouatta palliata). In: Adaptive Radiations of Neotropical Primates, Norconk MA, Rosenberger AL, and Garber PA, eds. New York, Plenum Press, pp. 433–49. [Google Scholar]

- Teaford MF, Lytle JD (1996) Diet-induced changes in rates of human tooth microwear: a case study involving stone-ground maize. Am. J. Phys. Anthropol. 100, 143–147. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Teaford MF, Oyen OJ, (1989a) In vivo and in vitro turnover in dental microwear. Am. J. Phys. Anthrop. 80, 447–460. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Teaford MF, Oyen OJ (1989b) Differences in the rate of molar wear between monkeys raised on different diets. J. Dent. Res. 68, 1513–1518. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Teaford MF, Tylenda CA (1991). A new approach to the study of tooth wear. J. Dent. Res. 70, 204–207. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Teaford MF, Ungar PS, Taylor AB, Ross CF, Vinyard CJ (2017) In vivo rates of dental microwear formation in laboratory primates fed different food items. Biosurf. & Biotribol. 3, 166–173. [Google Scholar]

- Teaford MF, Ungar PS, Taylor AB, Ross CF, & Vinyard CJ (2020). The dental microwear of hard-object feeding in laboratory Sapajus apella. Am. J. Phys. Anthropol. 171, 439–455. doi: 10.1002/ajpa.24000 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ungar PS, Sponheimer M (2011). The diets of early hominins, Science 334, 190–193. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ungar PS, Teaford MF, Glander KE, Pastor RF (1995). Dust accumulation in the canopy: a potential cause of dental microwear in primates. Am. J. Phys. Anthropol. 97, 93–99. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ungar PS, Grine FE, Teaford MF (2008). Dental microwear and diet of the Plio-Pleistocene hominin Paranthropus boisei, PLoS ONE 3, e2044. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ungar PS, Scott JR, Steininger CM (2016). Dental microwear differences between eastern and southern African fossil bovids and hominin. S. Af. J. Sci. 112, #2015–0393. [Google Scholar]

- van Casteren A, Fogaça MD, Fragaszy DM, Izar P, Ross CF, Scott RS, Wright BW, Wright KA, Strait DS (2019). Grit in unexpected places: The prevalence of grit in the diets of robust capuchin species. Am. J. Phys. Anthropol. 168(S68), 254–255. [Google Scholar]

- van Casteren A, Strait DS, Swain MV, Michael S, Thai LA, Philip SM, Saji S, Al-Fadhalah K, Almusallam AS, Shekeban A, McGraw WS, Kane EE, Wright BW, Lucas PW (2020). Hard plant tissues do not contribute meaningfully to dental microwear: evolutionary implications. Sci. Rep. 10, 582 doi: 10.1038/s41598-019-57403-w. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Venkataraman VV, Fashing PJ, Nguyen N (2019). The behavioral ecology of grit avoidance in gelada monkeys. Am. J. Phys. Anthropol. 168(S68), 256. [Google Scholar]

- Vinyard CJ, Wall CE, Williams SH, Hylander WL (2008). Patterns of variation across primates in jaw-muscle electromyography during mastication. Integr. Comp. Biol. 48, 294–311. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Visalberghi E, Fragaszy DM (1990). Food-washing behaviour in tufted capuchin monkeys, Cebus apella, and crabeating macaques, Macaca fascicularis. Anim. Behav. 40, 829–836. [Google Scholar]

- Williams SH, Wright BW, Den Truong V, Daubert CR and Vinyard CJ (2005). The mechanical properties of foods used in experimental studies of primate masticatory function. Am. J. Primatol. 67, 329–346. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Winkler DE, Schulz-Kornas E, Kaiser TM, Cuyper A. de, Clauss M, Tütken T (2019). Forage silica and water content control dental surface texture in guinea pigs and provide implications for dietary reconstruction. PNAS 116, 1325–1330. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Woda A, Foster K, Mishellany A, Peyron MA (2006). Adaptation of healthy mastication to factors pertaining to the individual or to the food. Physiol. Behav. 89, 28–35. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]