Graphical abstract

Keywords: Artificial neural network, Binary logistic regression, COVID-19, Intensive Care Unit, Laboratory variables, Mortality prediction model

Abstract

Background

Currently, good prognosis and management of critically ill patients with COVID-19 are crucial for developing disease management guidelines and providing a viable healthcare system. We aimed to propose individual outcome prediction models based on binary logistic regression (BLR) and artificial neural network (ANN) analyses of data collected in the first 24 hours of intensive care unit (ICU) admission for patients with COVID-19 infection. We also analysed different variables for ICU patients who survived and those who died.

Methods

Data from 326 critically ill patients with COVID-19 were collected. Data were captured on laboratory variables, demographics, comorbidities, symptoms and hospital stay related information. These data were compared with patient outcomes (survivor and non-survivor patients). BLR was assessed using the Wald Forward Stepwise method, and the ANN model was constructed using multilayer perceptron architecture.

Results

The area under the receiver operating characteristic curve of the ANN model was significantly larger than the BLR model (0.917 vs 0.810; p<0.001) for predicting individual outcomes. In addition, ANN model presented similar negative predictive value than the BLR model (95.9% vs 94.8%).

Variables such as age, pH, potassium ion, partial pressure of oxygen, and chloride were present in both models and they were significant predictors of death in COVID-19 patients.

Conclusions

Our study could provide helpful information for other hospitals to develop their own individual outcome prediction models based, mainly, on laboratory variables. Furthermore, it offers valuable information on which variables could predict a fatal outcome for ICU patients with COVID-19.

1. Introduction

The global Coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic affects millions of people and challenges healthcare systems worldwide. Most people with COVID-19 have mild or moderate respiratory symptoms and do not require hospital admission. However, some patients deteriorate rapidly, develop systemic or severe respiratory symptoms and need hospitalization, requiring invasive ventilation and admission to the intensive care unit (ICU) [1], [2], [3], [4]. During the “first wave” of the pandemic, the ICUs in many hospitals were forced to implement triage strategies for critically ill COVID-19 patients, because of the limited number of beds available [5], [6], [7], [8]. In several cases lacking effective triage tools, the healthcare system required reinforcement measures at national level, highlighting the need for helpful risk/mortality prediction models to enable a viable healthcare system [3], [9], [10]. Nowadays, several models have been proposed to predict the risk/mortality among patients with COVID-19 [9], [10], [11], [12], [13]. Despite this fact, only a limited number of models have been explicitly applied to ICU patients with COVID-19 [14], [15].

In the present study, we aimed to propose individual outcome prediction models for COVID-19 patients based on binary logistic regression (BLR) and artificial neural networks (ANN) that use laboratory routine variables and some clinical data collected within the first day of ICU admission. We also compared the two proposed models' performance and analysed laboratory and clinical variables for ICU patients who survived and those who dead.

2. Patients and methods

2.1. Study population and variables

A single-centre observational study was conducted in a 750-bed tertiary care public hospital for adults in Barcelona, Spain. The Ethics Committee approved the study (approval number PR168/20). Informed consent was waived due to the study’s observational nature, the mandatory isolation measures applied during in-hospital care, and, because the data were anonymised for analysis.

Three hundred and twenty-six patients admitted to the ICU between the first year of the pandemic (from March 15, 2020, to March 15, 2021) were included in this study. Patients aged 18 years old and above and presented severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2). Patients belonged to one of the different epidemic waves in Spain (first 147 [45.1%], second 28 [8.6%], and third 151 [46.3%]). The first wave occurred between March and May 2020, the second wave between June and November 2020, whereas the third wave took place from December 2020 to March 2021. During the first and second waves, the primary COVID-19 variant of concern (VOC) was the “wild-type”, followed by other variants of interest (VIC) as the EU1 (also so-called 20E or B.1.177). In the third wave, the Alpha variant (20I or B.1.1.7) was the main one, followed by the Gamma (20J or P.1) and Beta (20H or B.1.351) variants [16], [17], [18].

All patients were diagnosed by positive real-time polymerase chain reaction (RT-PCR) tests. They were either admitted directly to the ICU from the emergency department or were derived from specific COVID-19 units available in our hospital (conventional or semi-critical COVID-19 units, depending on severity). Patients admitted to the ICU met at least one of the following criteria: (i) patients with non-invasive mechanical ventilation (NIMV) with worsening respiratory conditions; (ii) patients developing respiratory failure requiring invasive mechanical ventilation (IMV); (iii) patients who had other organ failure requiring ICU monitoring. Supplementary material 1 contains additional information about the treatment underwent by COVID-19 patients.

Different patient data were collected on their first day of ICU admission. Demographics, clinical history information (comorbidities and pharmacological treatments), symptoms onset and admission information, as well as routine laboratory variables were included. These data were compared with patient outcomes.

Demographics included age and gender. Comorbidities (cancer, cardiac disease, chronic kidney disease, chronic liver disease, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, diabetes, dyslipidemia, hypertension, obesity, and smoking) were considered dichotomous categorical variables (presence or absence). The pharmacological treatments considered at hospital admission were antihypertensives, anticoagulants, antiaggregants, and immunosuppressive/corticosteroids. Symptoms onset and admission information refers to the number of days between appearance of clinical symptoms and admission to the hospital, the number of days between appearance of clinical symptoms and admission to the ICU, and the number of days from hospital admission to ICU admission.

The laboratory routine variables considered were those biological quantities used for the monitoring of COVID-19 patients based on IFCC recommendations [19]: plasma concentrations of alanine transaminase (ALT), albumin (ALB), aspartate transaminase (AST), bilirubin (BIL), calcium (CA), chloride (CL), creatinine (CREA), C-reactive protein (CRP), D-dimer (DD), ferritin (FERRI), glucose (GLU), interleukin 6 (IL-6), lactate dehydrogenase (LDH), potassium ion (K), procalcitonin (PROCAL), prothrombine time (PT), sodium ion (NA), troponin T (TROP-T), and urea (UREA); Chronic Kidney Disease Epidemiology Collaboration glomerular filtration rate (CKD-EPI); arterial blood partial pressure of carbon dioxide (paCO2), arterial blood partial pressure of oxygen (paO2); pH in arterial blood (apH), arterial blood oxygen saturation (aSatO2), partial pressure of oxygen in arterial blood/fraction of inspired oxygen quotient value (paO2/FiO2); blood count of basophils (#BAS), eosinophils (#EOS), leucocytes (#LEU), lymphocytes (#LYM), monocytes (#MON), neutrophils (#NEU), and platelets (PLT); leucocytes relative differential blood count (%BAS, %EOS, %LYM, %MON, and %NEU); blood count of erythrocytes (ERY), blood concentration of haemoglobin (HGB), haematocrit (HCT), mean cell volume (MCV), mean cell haemoglobin (MCH), mean cell haemoglobin concentration (MCHC), mean platelet volume (MPV), and red blood cells distribution width based on the coefficient of variation (RDW-CV).

Biochemical, haematological, and haemostasiological quantities were measured using Cobas 6000 or Cobas 8000 (Roche Diagnostics, Risch-Rotkreuz, Switzerland), Sysmex XN-2000 (Sysmex, Kobe, Japan), and ACL TOP 500 (Instrumentation Laboratory, Bedford, MA, USA) analyzers, respectively. Values of apH, paCO2, paO2, and aSatO2 have been obtained from GEM Premier 5000 gasometers (Instrumentation Laboratory).

Patients admitted to the ICU who survived and were subsequently discharged from the hospital, and non-survivor patients who dead during their hospital stay were considered outcomes.

2.2. Statistical Analysis

All statistical analysis were performed using the IBM SPSS Statistics 21.0 software (IBM Corp., Chicago, Ill, USA).

Descriptive statistics were presented using frequency rates and percentages for categorical variables, while continuous variables were described as the median and interquartile range (IQR). Comparisons between groups (survivors vs non-survivors) were assessed using the Mann–Whitney U test for continuous variables. Categorical comparisons were performed using the χ2 test or Fisher’s exact test, as appropriate. Also, each variable associated with the odds of COVID-19-related mortality was included.

We constructed and compared two individual outcome prediction models for patients with COVID-19 using data collected within their first day of ICU admission. The first model was based on a BLR approach, and the second on an ANN analysis. Using the 326 patient' data, we generated both models on a shared development dataset (training data) and tested them on a common validation dataset (testing data). The goodness-of-fit of the models was assessed using the Hosmer-Lemeshow C statistic [20]. Furthermore, the discrimination capacity of the models to separate survivors from non-survivors was analysed by calculating the area under the receiver operating characteristic curve (AUROC) and by estimating the post-test probability of an individual taking into account the sensitivity, specificity, positive predictive value (PPV), and negative predictive value (NPV) [21], [22]. To assess the post-test probability that a patient with COVID-19 who is admitted to ICU dies or not, PPV and NPV were calculated applying the Bayes' theorem [23] considering the prevalence of a COVID-19 patient admitted to ICU between March 15, 2020, and March 15, 2021 (16.2%), as well as the probability of death in ICU during the same period mentioned above.

Also, the AUROCs of the two models were compared based on the method described by DeLong et al. [24]. In addition, to verify the correct functioning of the models, a prospective study was carried out using 77 patients admitted to the ICU between April 1, 2021, and August 31, 2021 (patients belonged to the fourth and fifth waves in Spain). During the fourth wave (between April and June 2021), the predominant COVID-19 VOCs were the same variants described for the third wave, whereas, for the fifth wave (from July 2021 to present), the main VOCs were the Delta (21A or B.1.617.2) variant followed by the Beta [16], [17], [18].

2.3. Binary logistic regression model

A multivariable BLR analysis was performed to identify independent predictors that established a multivariable prediction model. The closely correlated variables (e.g., CKD-EPI, which include CREA, age and gender) were excluded before analysis to avoid multicollinearity. So, based on p-value results obtained in the univariate analysis, variables as CKD-EPI, #BAS, %EOS, #LYM, %MON, #NEU, MPV, HCT, HGB, MCV, and MCH were excluded. The Wald Forward Stepwise method was used to select the predictive variables considering a cut-off of 0.5, a maximum number of iterations of 20, and with stepwise probabilities of p<0.05 (for entries) and p<0.10 (for removals). Patient data were first randomly divided into a training dataset of 70% of the cases (n=234) and a test dataset of 30% of the cases (n=92) to construct the BLR model. This data distribution was performed to mimic those distributions obtained by the ANN model.

2.4. Artificial neural network model

The ANN was built using multilayer perceptron architecture. The network comprised an input layer including 75 neuron units based on standardised variables (15 dichotomic factors and 47 covariates), one hidden layer with six neuron units, and an output layer with two neuron units (the outcomes). The dichotomic factors included gender and clinical history information, while the laboratory variables, symptoms, and admission variables were considered covariates. We used the hyperbolic tangent activation function for the hidden layer and the Softmax activation with the Cross-entropy error functions for the output layer. The gradient descent based-method was used for optimising the ANN loss function. The ANN model was validated using a ten-fold cross-validation method using the training/test sample ratio of 7:3 (234:92 patient data).

3. Results

3.1. Descriptive data

The baseline characteristics of the 326 patients are depicted in Table 1 . The results of the univariate analysis showed that patients with older age, cancer, chronic kidney disease, immunosuppressive/corticosteroids treatment at hospital admission and a higher number of days from the appearance of clinical symptoms to admission to the ICU were associated with death in ICU patients (p<0.01). Regarding laboratory variables, higher values of CREA, DD, K, TROP-T, UREA, paCO2, and RDW-CV, as well as lower values of CKD-EPI, paO2, apH, aSatO2, paO2/FiO2, %BAS, %LYM, and MCHC were also associated with greater mortality risk (p<0.05).

Table 1.

Descriptive data for all, survivor and non-survivor ICU patients with COVID-19 infection.

| Variable | All(n=326) | Reference interval * | Survivors(n=156) | Non-Survivors(n=170) | p-value | OR(95% CI) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Demographics | ||||||

| Age; median (IQR) | 64 (55−71) | - | 59 (51−68) | 67 (61−72.5) | <0.001 | n.a. |

| Sex (Male); n (%) | 250 (76.7) | - | 122 (78.2) | 128 (75.3) | 0.535 | 0.849 (0.507−1.423) |

| Comorbidities | ||||||

| Cancer; n (%) | 37 (11.3) | - | 6 (3.8) | 31 (18.2) | <0.001 | 5.576 (2.258−13.77) |

| Cardiac disease; n (%) | 52 (16.0) | - | 20 (12.8) | 32 (18.8) | 0.221 | 1.577 (0.860−2.893) |

| Chronic kidney disease; n (%) | 45 (13.8) | - | 6 (3.8) | 39 (22.9) | <0.001 | 7.443 (3.054−18.14) |

| Chronic liver disease; n (%) | 28 (8.6) | - | 12 (7.7) | 16 (9.4) | 0.580 | 1.247 (0.570−2.726) |

| Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease; n (%) | 53 (16.3) | - | 21 (13.5) | 32 (18.8) | 0.190 | 1.491 (0.819−2.715) |

| Diabetes; n (%) | 93 (28.5) | - | 46 (29.5) | 47 (27.6) | 0.713 | 0.914 (0.565−1.478) |

| Dyslipidemia; n (%) | 160 (49.1) | - | 70 (44.8) | 90 (52.9) | 0.145 | 1.382 (0.894−2.138) |

| Hypertension; n (%) | 173 (53.1) | - | 77 (49.4) | 96 (56.5) | 0.199 | 1.331 (0.860−2.060) |

| Obesity; n (%) | 162 (49.7) | - | 83 (53.2) | 79 (46.5) | 0.224 | 0.764 (0.494−1.180) |

| Smoking; n (%) | 24 (7.4) | - | 8 (5.1) | 16 (9.4) | 0.230 | 1.992 (0.799−4.623) |

| Pharmacological treatment currently administered at hospital admission | ||||||

| Antihypertensive drugs; n (%) | 147 (45.1) | - | 64 (41.0) | 83 (48.8) | 0.158 | 1.371 (0.885−2.126) |

| Anticoagulant drugs; n (%) | 40 (12.3) | - | 14 (9.0) | 26 (15.3) | 0.082 | 1.831 (0.919−3.651) |

| Antiaggregant drugs; n (%) | 52 (16.0) | - | 19 (12.2) | 33 (19.4) | 0.075 | 1.737 (0.942−3.203) |

| Immunosuppressive or corticosteroids drugs; n (%) | 32 (9.8) | - | 7 (4.5) | 25 (14.7) | 0.002 | 3.670 (1.539−8.749) |

| Symptoms onset and admission | ||||||

| Number of days from the appearance of clinical symptoms to admission to the hospital; median (IQR) | 8 (6−11) | - | 8 (6−10) | 8 (6−12) | 0.379 | n.a. |

| Number of days from the appearance of clinical symptoms to admission to the ICU; median (IQR) | 12 (8−16) | - | 11 (8−14.5) | 13 (9−18) | 0.008 | n.a. |

| Number of days from the hospital admission to the ICU; median (IQR) | 2 (0−6) | - | 2 (0−5) | 3 (0−7) | 0.098 | n.a. |

| Biological quantities values obtained within the first day in ICU | ||||||

| ALT, U/L; median (IQR) | 34 (23−56.3) | M: < 41F: < 33 | 37 (25−59.5) | 34 (22−51) | 0.123 | n.a. |

| ALB, g/L; median (IQR) | 31.6 (27.4−35.0) | 35.0−52.0 | 32.0 (27.0−35.0) | 31.2 (28.0−35.0) | 0.848 | n.a. |

| AST, U/L; median (IQR) | 45 (31−64.8) | M: < 40F: < 32 | 45 (31.5−68) | 44 (30−59) | 0.611 | n.a. |

| BIL, μmol/L; median (IQR) | 9.2 (6.5−13.9) | ≤ 18 | 9.5 (6.7−13.0) | 9.0 (6.0−14.8) | 0.489 | n.a. |

| CA, mmol/L; median (IQR) | 2.13 (2.03−2.22) | M: (2.20−2.54)F: (2.15−2.51) | 2.12 (2.03−2.21) | 2.14 (2.04−2.22) | 0.318 | n.a. |

| CKD-EPI, mL/min/1.73 m2; median (IQR) | 85 (58−101) | ≥ 60 | 92 (68.5−105.5) | 80 (52−95.5) | <0.001 | n.a. |

| CL, mmol/L; median (IQR) | 99 (96−102) | 98−116 | 99 (96−102) | 100 (96−103) | 0.169 | n.a. |

| CREA, μmol/L; median (IQR) | 81 (61−114) | M: (59−104)F: (45−84) | 74 (58−100) | 84 (63.5−121.5) | 0.005 | n.a. |

| CRP, mg/L; median (IQR) | 136.1 (52.8−238.3) | ≤ 5.0 | 150.0 (64.7−250.9) | 126.2 (47.3−222.9) | 0.232 | n.a. |

| DD, μg/L; median (IQR) | 879 (454−2862) | < 250 | 772 (416−1745) | 1014 (485−3866) | 0.033 | n.a. |

| FERRI, μg/L; median (IQR) | 1495 (874−2324) | M: (30−400)F:≤50 yo (15−150)>50 yo (30−400) | 1492 (734−2609) | 1495 (898−2025) | 0.381 | n.a. |

| GLU, mmol/L; median (IQR) | 8.20 (6.51−10.7) | 4.10−6.10 | 7.90 (6.46−10.7) | 8.30 (6.90−10.6) | 0.479 | n.a. |

| IL-6, ng/L; median (IQR) | 91.3 (19.5−455.2) | < 7.0 | 80.8 (14.6−173.1) | 101.3 (31.3−609.0) | 0.140 | n.a. |

| LDH, U/L; median (IQR) | 471.5 (367.5−610.8) | M: < 225F: < 214 | 452 (353.5−588.5) | 501 (387−624) | 0.080 | n.a. |

| K, mmol/L; median (IQR) | 4.13 (3.72−4.48) | 3.83−5.10 | 3.97 (3.64−4.40) | 4.27 (3.89−4.57) | 0.001 | n.a. |

| PROCAL, μg/L; median (IQR) | 0.26 (0.13−0.68) | < 0.50 | 0.24 (0.12−0.63) | 0.30 (0.15−0.74) | 0.122 | n.a. |

| PT, 1; median (IQR) | 1.16 (1.08−1.28) | 0.80−1.20 | 1.18 (1.08−1.28) | 1.15 (1.08−1.28) | 0.763 | n.a. |

| NA, mmol/L; median (IQR) | 138 (135−141) | 135−147 | 137 (135−140.5) | 138 (135−141) | 0.583 | n.a. |

| TROP-T, ng/L; median (IQR) | 14.7 (9.4−28.2) | < 14.0 | 13.2 (9.0−25.1) | 17.0 (11.1−40.5) | 0.019 | n.a. |

| UREA, mmo/L; median (IQR) | 7.9 (5.2−11.5) | M: (3.6−8.6)F: (3.3−8.0) | 7.1 (4.8−9.6) | 8.7 (6.4−13.8) | <0.001 | n.a. |

| paCO2, mmHg; median (IQR) | 46.0 (40.0−56.5) | M: (35.0−48.0)F: (32.0−45.0) | 42.0 (38.0−50.0) | 51.0 (42.0−61.0) | <0.001 | n.a. |

| paO2, mmHg; median (IQR) | 96.5 (76.0−125.0) | 83.0−108.0 | 102.0 (85.0−131.5) | 89.0 (74.0−111.5) | 0.003 | n.a. |

| apH, 1; median (IQR) | 7.35 (7.29−7.43) | 7.35−7.45 | 7.39 (7.31−7.45) | 7.33 (7.26−7.38) | <0.001 | n.a. |

| aSatO2, %; median (IQR) | 97.1 (94.5−98.7) | 95.0−98.0 | 97.8 (96.2−99.0) | 96.5 (93.6−98.1) | <0.001 | n.a. |

| paO2/FiO2, mmHg; median (IQR) | 117 (86−166) | 136 (103−180) | 100 (76−150) | <0.001 | n.a. | |

| #BAS, ·109 ent./L; median (IQR) | 0.01 (0.01−0.03) | 0.01−0.09 | 0.02 (0.01−0.03) | 0.01 (0.00−0.02) | 0.302 | n.a. |

| %BAS, %; median (IQR) | 0.20 (0.08−0.30) | 0.20−1.30 | 0.20 (0.10−0.30) | 0.10 (0.00−0.20) | 0.049 | n.a. |

| #EOS, ·109 ent./L; median (IQR) | 0.00 (0.00−0.01) | 0.03−0.39 | 0.00 (0.00−0.01) | 0.00 (0.00−0.01) | 0.402 | n.a. |

| %EOS, %; median (IQR) | 0.00 (0.00−0.20) | 0.40−6.60 | 0.00 (0.00−0.20) | 0.00 (0.00−0.20) | 0.495 | n.a. |

| LEU, ·109 ent./L; median (IQR) | 9.75 (6.80−14.3) | 3.90−9.50 | 9.05 (6.95−12.6) | 10.1 (6.75−16.6) | 0.165 | n.a. |

| #LYM, ·109 ent./L; median (IQR) | 0.64 (0.38−0.96) | 1.30−3.40 | 0.69 (0.50−1.02) | 0.59 (0.36−0.90) | 0.056 | n.a. |

| %LYM, %; median (IQR) | 6.6 (3.6−10.3) | 21.0−50.0 | 7.5 (4.4−10.8) | 5.5 (3.3−9.8) | 0.014 | n.a. |

| #MON, ·109 ent./L; median (IQR) | 0.37 (0.23−0.66) | 0.31−0.92 | 0.35 (0.23−0.61) | 0.40 (0.24−0.69) | 0.470 | n.a. |

| %MON, %; median (IQR) | 4.0 (2.5−6.2) | 5.1−11.2 | 4.0 (2.8−5.9) | 4.0 (2.4−6.4) | 0.943 | n.a. |

| #NEU, ·109 ent./L; median (IQR) | 8.41 (5.72−12.7) | 1.50−5.70 | 8.13 (5.75−11.5) | 9.07 (5.70−14.0) | 0.179 | n.a. |

| %NEU, %; median (IQR) | 88.1 (82.9−92.6) | 37.0−68.0 | 86.8 (82.2−91.6) | 88.7 (83.4−93.7) | 0.084 | n.a. |

| PLT, ·109 ent./L; median (IQR) | 232 (173−303) | M: (149−303)F: (153−368) | 237 (180−300.5) | 229 (169.5−305) | 0.510 | n.a. |

| MPV, fL; median (IQR) | 10.7 (10.1−11.5) | 9.7−13.2 | 10.7 (10.1−11.5) | 10.7 (10.1−11.6) | 0.684 | n.a. |

| ERY, ·1012 ent./L; median (IQR) | 4.42 (4.00−4.90) | M: (4.3−5.6)F: (3.9−5.1) | 4.46 (4.14−4.93) | 4.31 (3.83−4.90) | 0.123 | n.a. |

| HGB, g/L; median (IQR) | 132 (119−145) | M: (130−165)F: (120−147) | 134 (122−146.5) | 130 (114.5−144) | 0.107 | n.a. |

| HCT, %; median (IQR) | 39.8 (36.0−43.0) | M: (40−50)F: (36−45) | 40.0 (37.0−43.6) | 39.5 (35.0−43.0) | 0.207 | n.a. |

| MCV, fL; median (IQR) | 89.8 (86.5−92.5) | 84−97 | 89.2 (86.2−92) | 90 (87−93) | 0.198 | n.a. |

| MCH, pg; median (IQR) | 30 (28.8−31) | 27−32 | 30 (29−31) | 30 (28.7−31) | 0.745 | n.a. |

| MCHC, g/L; median (IQR) | 333 (324−342) | 314−349 | 335.5 (328−343.5) | 332 (322.5−338.5) | 0.010 | n.a. |

| RDW-CV, %; median (IQR) | 13.4 (12.9−14.4) | 12−14 | 13.3 (12.7−14.1) | 13.6 (13.1−14.7) | 0.003 | n.a. |

*Reference intervals established in our hospital.

OR, odds-ratio; ICU, intensive care unit; IQR, interquartilic range; n.a., not applicable; M, male; F, female; ALT, catalytic concentration of alanine transaminase in plasma; ALB, mass concentration of albumin in plasma; AST, catalytic concentration of aspartate transaminase in plasma; BIL, substance concentration of bilirubin in plasma; CA, substance concentration of calcium(II) in plasma; CKD-EPI, Chronic Kidney Disease Epidemiology Collaboration glomerular filtration rate; CL, substance concentration of chloride in plasma; CREA, substance concentration of creatinine; CRP, mass concentration of C-reactive protein in plasma; DD, mass concentration of D-dimer in plasma; FERRI, mass concentration of ferritin in plasma; GLU, substance concentration of glucose in plasma; IL-6, mass concentration of interleukin 6 in plasma; LDH, catalytic concentration of lactate dehydrogenase in plasma obtained within the first admission day; K, substance concentration of potassium ion in plasma; PROCAL, mass concentration of procalcitonin in plasma; PT, relative time of prothrombine in plasma; NA, substance concentration of sodium ion in plasma; TROP-T, mass concentration of troponin T in plasma; UREA, substance concentration of urea in plasma; paCO2, partial pressure of carbon dioxide in arterial blood; paO2, partial pressure of oxygen in arterial blood; apH, pH in arterial blood; aSatO2, substance fraction of oxygen in arterial blood, paO2/FiO2, partial pressure of oxygen in arterial blood/fraction of inspired oxygen quotient value; #BAS, number concentration of basophiles in blood; %BAS, number fraction of basophiles in the leucocytes of the blood; #EOS, number concentration of eosinophils in blood; %EOS, number fraction of eosinophils in the leucocytes of the blood; LEU, number concentration of leucocytes in blood; #LYM, number concentration of lymphocytes in blood; %LYM, number fraction of lymphocytes in the leucocytes of the blood; #MON, number concentration of monocytes in blood obtained; %MON, number fraction of monocytes in the leucocytes of the blood; #NEU, number concentration of neutrophils in blood; %NEU, number fraction of neutrophils in the leucocytes of the blood; PLT, number concentration of platelets in blood; MPV, entitic volum of platelets in blood (mean platelet volume); ERY, number concentration of erythrocytes in blood; HGB, mass concentration of haemoglobin in blood; HCT, volume fraction of erythrocytes in blood (haematocrit); MCV, entitic volum of erythrocytes in blood (mean corpuscular volume); MCH, entitic mass of haemoglobin contained in the erythrocytes of the blood (mean corpuscular haemoglobin); MCHC, mass concentrarion of haemoglobin contained in the erythrocytes of the blood (mean corpuscular haemoglobin concentration); relative distribution width of the erythrocytic volume in the erythrocytes of the blood (red blood cell distribution width).

Numbers in bold indicate a p-value < 0.05.

3.2. Binary logistic regression model

For the BLR model, multivariate analysis using stepwise variable selection based on the Wald Forward method showed that variables such as age, hypertension, chronic kidney disease, K, CL, apO2, and apH, were independent predictors of death in ICU patients with COVID-19 (p<0.001) (see Table 2 ).

Table 2.

Results of multivariate binary logistic regression analysis obtained for ICU patients with COVID-19 infection using the Wald Forward Stepwise method.

| Variable | β | SE | Wald-value | p-Value | OR (eβ)(95% CI) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age | 0.112 | 0.026 | 18.449 | <0.001 | 1.118(1.063−1.177) |

| Hypertension | -1.050 | 0.470 | 4.985 | 0.026 | 0.350(0.139−0.880) |

| Chronic renal disease | 2.537 | 1.100 | 5.315 | 0.021 | 12.64(1.463−109.2) |

| K | 0.945 | 0.422 | 5.008 | 0.025 | 2.572(1.124−5.883) |

| CL | -0.116 | 0.045 | 6.480 | 0.011 | 0.891(0.815−0.974) |

| apO2 | -0.020 | 0.008 | 6.385 | 0.012 | 0.981(0.966−0.996) |

| apH | -9.986 | 2.311 | 18.665 | <0.001 | 1.2·10-4(0.23·10-5−0.004) |

| β0 | 76.481 | 18.520 | 17.054 | <0.001 | - |

β, multivariable logistic regression constants; SE; standard error; OR (eβ), multivariate odds-ratio; ICU, intensive care unit; K, substance concentration of potassium ion in plasma obtained within the first ICU admission day; CL, substance concentration of chloride in plasma obtained within the first ICU admission day; paO2, partial pressure of oxygen in arterial blood obtained within the first ICU admission day; apH, pH in arterial blood obtained within the first ICU admission day; β0, univariate logistic regression constant.

The multivariate logistic regression equation obtained to estimate the percentage probability of death () and probability of survival () for COVID-19 patients based on their first day of ICU admission was:

where is the age (in years); , the dichotomic hypertension value (0 if the patients do not present hypertension, and 1 if they do); , the dichotomic chronic kidney disease value (0 if the patients do not have chronic kidney disease, and 1 if they have it); and , , , , the K, CL, paO2, and pH values obtained from the patients during the first day of their ICU admission.

After the seventh iteration using the Wald Forward Stepwise method, the −2 log(likelihood), the Cox&Snell’s coefficient of determination (r 2), and the Nagelkerke r 2 values obtained were 132.81, 0.382, and 0.503, respectively. The Hosmer and Lemeshow C goodness-of-fit statistic was not significant (α=0.05; p=0.499).

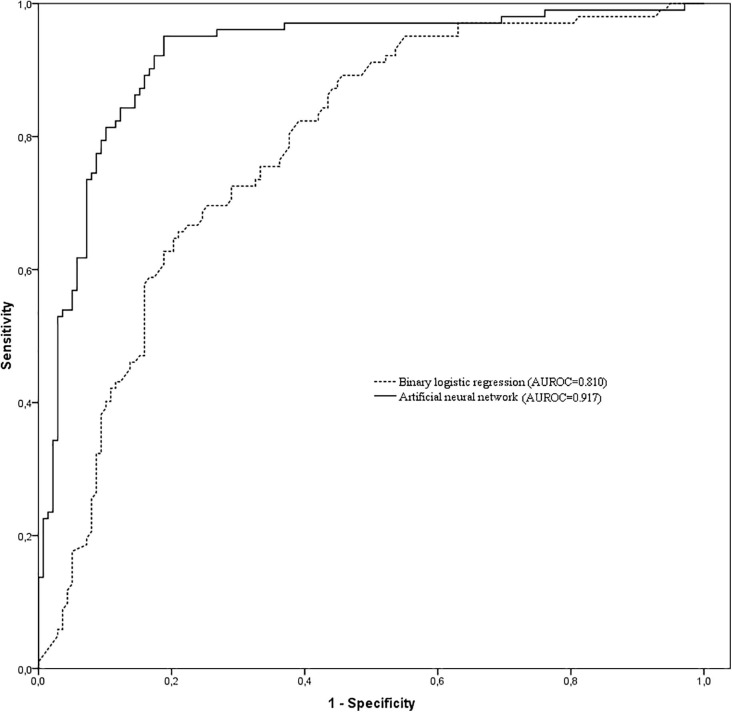

For the training data group, the AUROC, sensitivity, specificity, PPV, and NPV data were 0.810 (95% CI, 0.762−0.858), 78.9%, 74.3%, 37.2%, and 94.8%, respectively (see Fig. 1 ). For the testing data group, these values were 0.789 (95% CI, 0.739−0.839), 77.4%, 75.7%, 38.1%, and 94.5%. A comparison of the AUROCs showed no statistically significant differences between the two groups (p=0.542).

Fig. 1.

Comparison of area under the receiver operating characteristic curves among the binary logistic regression and artificial neural network models to separate survival and non-survival COVID-19 patients within their first day in the ICU admission. AUROC = Area under the receiver operating characteristic curve.

3.3. Artificial neural network model

The Hosmer and Lemeshow C goodness-of-fit statistic for the ANN model was not significant (α=0.05; p=0.843).

For the training data group, the AUROC, sensitivity, specificity, PPV and NPV were 0.917 (95% CI, 0.873−0.961), 80.4%, 89.8%, 60.4%, and 95.9%, respectively (See Fig. 1). Further, for the testing data group, sensitivity, specificity, PPV, and NPV were 84.2%, 87.6%, 56.8%, and 96.6%.

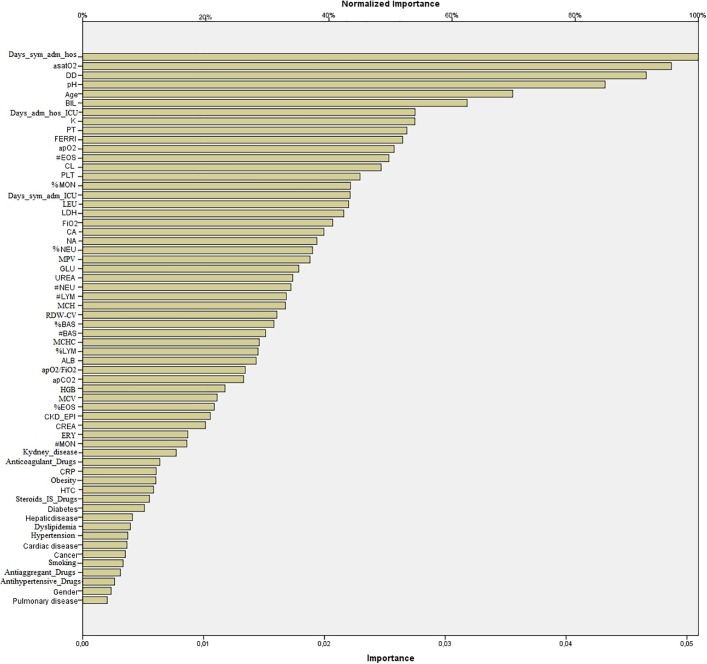

The variance importance matrix plot of variables for ANN is shown in Fig. 2 . The variables “number of days between appearance of clinical symptoms and admission to the hospital”, DD, aSatO2, and pH were ranked first, while variables as chronic pulmonary disease, gender, and the “take of antihypertensive and antiaggregant drugs at hospital admission” were the last.

Fig. 2.

Variance importance matrix plot of variables collected in the first 24 hours of intensive care unit for artificial neural network in patients with COVID-19. ALB, mass concentration of albumin in plasma; BIL, substance concentration of bilirubin in plasma; CA, substance concentration of calcium(II) in plasma; CKD-EPI, Chronic Kidney Disease Epidemiology Collaboration glomerular filtration rate; CL, substance concentration of chloride in plasma; CREA, substance concentration of creatinine; CRP, mass concentration of C-reactive protein in plasma; Days_ adm_hos_ICU, number of days from hospital admission to ICU admission; Days_sym_adm_hos, number of days between appearance of clinical symptoms and admission to the hospital; Days_sym_adm_ICU, number of days between appearance of clinical symptoms and admission to the ICU; DD, mass concentration of D-dimer in plasma; FERRI, mass concentration of ferritin in plasma; GLU, substance concentration of glucose in plasma; LDH, catalytic concentration of lactate dehydrogenase in plasma obtained within the first admission day; K, substance concentration of potassium ion in plasma; PT, relative time of prothrombine in plasma; NA, substance concentration of sodium ion in plasma; TROP-T, mass concentration of troponin T in plasma; UREA, substance concentration of urea in plasma; paCO2, partial pressure of carbon dioxide in arterial blood; paO2, partial pressure of oxygen in arterial blood; apH, pH in arterial blood; aSatO2, substance fraction of oxygen in arterial blood, paO2/FiO2, partial pressure of oxygen in arterial blood/fraction of inspired oxygen quotient value; #BAS, number concentration of basophiles in blood; %BAS, number fraction of basophiles in the leucocytes of the blood; #EOS, number concentration of eosinophils in blood; %EOS, number fraction of eosinophils in the leucocytes of the blood; LEU, number concentration of leucocytes in blood; #LYM, number concentration of lymphocytes in blood; %LYM, number fraction of lymphocytes in the leucocytes of the blood; #MON, number concentration of monocytes in blood obtained; %MON, number fraction of monocytes in the leucocytes of the blood; #NEU, number concentration of neutrophils in blood; %NEU, number fraction of neutrophils in the leucocytes of the blood; PLT, number concentration of platelets in blood; MPV, entitic volum of platelets in blood (mean platelet volume); ERY, number concentration of erythrocytes in blood; HGB, mass concentration of haemoglobin in blood; HCT, volume fraction of erythrocytes in blood (haematocrit); MCV, entitic volum of erythrocytes in blood (mean corpuscular volume); MCH, entitic mass of haemoglobin contained in the erythrocytes of the blood (mean corpuscular haemoglobin); MCHC, mass concentrarion of haemoglobin contained in the erythrocytes of the blood (mean corpuscular haemoglobin concentration); relative distibution width of the erythrocytic volume in the erythrocytes of the blood (red blood cell distribution width).

3.4. Comparison between models

The AUROC of the ANN model was significantly larger than the BLR model (0.917 vs 0.810; p<0.001) for predicting individual outcome in COVID-19 patients using data collected within the first day of ICU admission. Furthermore, the post-test probability showed that PPV was higher for the ANN model than for the BLR model (60.4% vs 37.2%) but similar for the NPV (95.9% vs 94.8%).

3.5. Prospective study

Using the 77 patients admitted to the ICU between April 1, 2021, and August 31, 2021, and applying the BLR model, the sensitivity, specificity, PPV, and NPV obtained were 64.0%, 66.7%, 27.1%, and 90.5%, respectively. Furthermore, considering the ANN model, these values were 76.0%, 81.5%, 44.2%, and 94.6%.

4. Discussion

The present study provides valuable information on which variables from the first day of ICU admission can predict a fatal outcome in ICU patients with COVID-19, and BLR and ANN models to predict the mortality or survival of these patients.

In our univariate analysis of COVID-19 patients who were admitted to the ICU and subsequently died, some of our results were consistent with the literature, and some were not. For instance, Zhao et al. [15] have also shown that advanced age, chronic kidney disease, higher DD and TROP-T values, and lower %LYM and aSatO2 values were associated with higher mortality risk. Additionally, in line with our findings, Chen et al. [25] and Berenger et al. [26] observed that patients with cancer and with higher levels of CREA, UREA, and DD values; and lower %LYM values presented statistically significant mortality. Furthermore, Aksel et al. [27] also showed that variables such as hypertension, diabetes, smoking, and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease were not associated with greater mortality risk. Our study found that CRP, ALT, ALB, LEU, and PLT values were not associated with mortality, which differs from previously published data [15], [25], [26], [27]. We consider that these discrepancies could be explained by both the basal characteristics of the population admitted to the ICU and the fact that data were recollected mainly during the first pandemic wave. Also, the discrepancies could be explained by the fact that patients were admitted to ICU from different units, i.e., they came directly from the emergency department or were already admitted to the hospital and came from other minor severity units (conventional or semi-critical units).

The novelty of our study is that we have jointly included variables such as the primary acid-base equilibrium related-quantities (apH, paCO2, paO2, and aSatO2), renal related-quantities (CREA, CKD-EPI, K and UREA), PROCAL and TROP-T, a complete blood count including red blood cell indices (MCV, MCHC, RDW-CV), as well as dyslipidemia, pharmacological treatments at hospital admission, symptoms onset and admission related information. All these variables were associated with higher mortality risk or present values close to the statistical significance.

Regarding prediction models, at present, different BLR and ANN models have been studied together on a standard dataset applied to COVID-19 patients [12], [14], [15], [28], [29]. However, to our knowledge, no studies have been published predicting mortality/survival of COVID-19 patients based on their first day of ICU admission and considering all the variables shown in Table 1. Thus, it should be noted that we have not compared our results obtained using BLR and ANN models with data previously published in the literature due to a lack of homogeneity of data between studies and to avoid misinterpretation:

-

•

The variables considered to construct the BLR and ANN models and the collection time of patient data are different between studies.

-

•

Different BLR methods and ANN architectures are applied in other studies (e.g., forward and backward strategies in the case of BLR), the multilayer perceptron, radial basis function, and the number of layers for the different neurons units, among others, for the ANN).

-

•

The measuring systems used to determine the biological quantities (laboratory variables) are also different between studies, and they will provide non-comparable results, mainly for those that use immunoassay techniques.

For all these reasons, we believe that comparing our results with those published in the literature might be more confusing than helpful.

In our multivariate BLR analysis, age, hypertension, chronic kidney disease, K, CL, apO2, and apH were independent predictors of death in ICU patients with COVID-19. Also, this model presented acceptable discrimination capacity to separate survivors from non-survivors (AUROC=0.810 and NPV=94.8%). Its usefulness was verified from prospective data (NPV=90.5%). Further, in our ANN model, we obtained significantly higher performance than the BLR model for prediction of survivor patients in terms of AUROC (0.917 vs 0.810) but similar in terms of NPV (95.9% vs 94.8%). In addition, the results of verification of the ANN model from prospective data also showed its usefulness (NPV=94.6%).

Our study found that younger patients, with higher pH, apO2, CL values, and lower K values were significantly more likely to have a favourable outcome. All these variables were present in both models with greater significance, i.e., they were independent predictors of survival in the BLR model and had high relative importance in the ANN model.

Furthermore, considering that we had two different models with an adequate capacity of discrimination [30], another issue that we would like to discuss is which of the models would be more useful in daily clinical practice. Although both models present similar NPV, the ANN model should preferably be used instead of the BLR model, because it presents higher performance for predicting survivor patients (in terms of AUC) and non-survivor patients (in terms of PPV). Nonetheless, the results obtained from ANN models are more difficult to interpret than those obtained from the BLR model and require friendly computer support to facilitate the clinician’s task. Thus, in absence of this computer support, a possible solution could be to employ the ANN prediction model using information-sharing procedures that clinicians are already accustomed to. For example, the results could be included in the laboratory reports as another biological quantity result. An alternative would be to use the BLR model, which clinicians could introduce into commonly used software (e.g., an Excel spreadsheet).

In addition to the generic limitations cited above related to the lack of data homogeneity between studies, our study has other specific limitations:

-

1.

It has been performed using a “small” number of cases, challenging the statistical power for the BLR model and compromising adequate ANN learning.

-

2.

This is an observational study that used data derived from a single centre. So, our findings may not be generalisable to all healthcare institutions worldwide, especially considering the high COVID-19 variability between different countries and populations.

-

3.

A more significant number of patients should have been used in the prospective study in such a way that the robustness would have been unequivocally guaranteed.

-

4.

Additional studies are required to determine how clinicians may respond to risk predictions and whether these predictions can affect patient outcomes equivocally guaranteed.

-

5.

Considering that data were collected as part of usual care and in a “period of chaos”, not all meaningful laboratory data could be collected for most patients. So, consequently, they were not considered and included in the models (e.g., the catalytic concentration of creatine kinase, γ-glutamyl transferase, alkaline phosphatase in plasma; a vitamin profile based on the measurement of the substance concentration of pyridoxal 5'-phosphate, ascorbate, calcidiol, cobalamin, folate, retinol, and thiamine diphosphate in blood or plasma; urinary sediment related-quantities, among others).

Despite all these limitations, we consider that we have obtained promising results that allowed us to meet one of our objectives, i.e., the development of a helpful tool to predict individual outcome for COVID-19 patients based on, mainly, laboratory variables obtained during the first day of ICU admission. Also, considering the results obtained and the verifications assessed, the models could be used in the future, because they seem to be independent of waves of the pandemic or the COVID-19 variants. This fact could be helpful to implement triage policies for critically ill COVID-19 patients with a limited number of beds available.

Finally, considering all the reasons mentioned above, every healthcare institution should develop their own prediction models using all the data they could collect and update their models periodically. An alternative could be to create models containing data collected from various institutions.

5. Conclusions

Accurate individual outcome predictions for COVID-19 patients based on their first day of ICU admission were obtained using BLR and ANN models. Our study could provide helpful information for other healthcare institutions on how to develop their prediction models. In addition, our study provides valuable information as to which clinical and analytical variables obtained on the first day of ICU admission could predict individual outcome for ICU patients with COVID-19. In our opinion, this fact would allow optimize patient’s triage in a saturated health system due to the Covid-19 pandemic.

Funding

None.

7. Declarations of interest

None.

Declaration of competing interest

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

Acknowledgements

We thank the multidisciplinary team working in the Hospital Universitari de Bellvitge for their efforts and support during the COVID-19 pandemic.

References

- 1.Huang C., Wang Y., Li X., Ren L., Zhao J., Hu Y.i., Zhang L.i., Fan G., Xu J., Gu X., Cheng Z., Yu T., Xia J., Wei Y., Wu W., Xie X., Yin W., Li H., Liu M., Xiao Y., Gao H., Guo L.i., Xie J., Wang G., Jiang R., Gao Z., Jin Q.i., Wang J., Cao B. novel coronavirus in Wuhan. China, Lancet. 2020;395(10223):497–506. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30183-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Chen N., Zhou M., Dong X., Qu J., Gong F., Han Y., Qiu Y., Wang J., Liu Y., Wei Y., Xia J., Yu T., Zhang X., Zhang L.i. novel coronavirus pneumonia in Wuhan, China: A descriptive study. Lancet. 2020;395(10223):507–513. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30211-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Wu Z., McGoogan J.M., Characteristics, of, and, important, lessons, from, the, coronavirus, disease, (COVID-19) outbreak in China: Summary of a report of 72314 cases from the Chinese Center for Disease Control and Prevention. JAMA. 2019;323(2020):1239–1242. doi: 10.1001/jama.2020.2648. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Khan M., Khan H., Khan S., M., Nawaz, M, Epidemiological and clinical characteristics of coronavirus disease (COVID-19) cases at a screening clinic during the early outbreak period: a single-centre study. J. Med. Microbiol. 2020;69:1114–1123. doi: 10.1099/jmm.0.001231. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Sprung C.L., Joynt G.M., Christian M.D., Truog R.D., Rello J., Nates J.L., Adult I.C.U., triage, during, the, coronavirus, disease, pandemic: who will live and who will die? Recommendations to improve survival. Crit. Care Med. 2019;48(2020):1196–1202. doi: 10.1097/CCM.0000000000004410. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Leclerc Thomas, Donat Nicolas, Donat Alexis, Pasquier Pierre, Libert Nicolas, Schaeffer Elodie, D’Aranda Erwan, Cotte Jean, Fontaine Bruno, Perrigault Pierre-François, Michel Fabrice, Muller Laurent, Meaudre Eric, Veber Benoît. Prioritisation of ICU treatments for critically ill patients in a COVID-19 pandemic with scarce resources, Anaesth. Crit. Care. Pain Med. 2020;39(3):333–339. doi: 10.1016/j.accpm.2020.05.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Burman R., Cairns R., Canestrini S., Elias R., Metaxa V., Owen G., et al. Making ordinary decisions in extraordinaty times. BMJ. 2020;370 doi: 10.1136/bmj.m3268. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Robert R., Kentish-Barnes N., Boyer A., Laurent A., Azoulay E., J., Reignier, J, Ethical dilemmas due to the Covid-19 pandemic. Ann. Intensive Care. 2020;10:84. doi: 10.1186/s13613-020-00702-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Maves Ryan C., Downar James, Dichter Jeffrey R., Hick John L., Devereaux Asha, Geiling James A., Kissoon Niranjan, Hupert Nathaniel, Niven Alexander S., King Mary A., Rubinson Lewis L., Hanfling Dan, Hodge James G., Marshall Mary Faith, Fischkoff Katherine, Evans Laura E., Tonelli Mark R., Wax Randy S., Seda Gilbert, Parrish John S., Truog Robert D., Sprung Charles L., Christian Michael D. Triage of scarce critical care resources in covid-19 an implementation guide for regional allocation: an expert panel report of the Task Force for Mass Critical Care and the American College of Chest Physicians. Chest. 2020;158(1):212–225. doi: 10.1016/j.chest.2020.03.063. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Zhou Fei, Yu Ting, Du Ronghui, Fan Guohui, Liu Ying, Liu Zhibo, Xiang Jie, Wang Yeming, Song Bin, Gu Xiaoying, Guan Lulu, Wei Yuan, Li Hui, Wu Xudong, Xu Jiuyang, Tu Shengjin, Zhang Yi, Chen Hua, Cao Bin. Clinical course and risk factors for mortality of adult inpatients with COVID-19 in Wuhan, China: a retrospective cohort study. Lancet. 2020;395(10229):1054–1062. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30566-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Xiaojing Zou Shusheng Li Minghao Fang Ming Hu Yi Bian Jianmin Ling Shanshan Yu Liang Jing Donghui Li Jiao Huang 48 8 2020 e657 e665 10.1097/CCM.0000000000004411 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 12.Fang-Yan Liu Xue-Lian Sun Yong Zhang Lin Ge Jing Wang Xiao Liang Jun-Fen Li Chang-Liang Wang Zheng-Tao Xing Jagadish K. Chhetri Peng Sun Piu Chan Evaluation of the risk prediction tools for patients with coronavirus disease 2019 in Wuhan, China: A single-centered, retrospective, observational study 48 11 2020 e1004 e1011 10.1097/CCM.0000000000004549 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 13.Tang Xiao, Du Rong-Hui, Wang Rui, Cao Tan-Ze, Guan Lu-Lu, Yang Cheng-Qing, Zhu Qi, Hu Ming, Li Xu-Yan, Li Ying, Liang Li-Rong, Tong Zhao-Hui, Sun Bing, Peng Peng, Shi Huan-Zhong. Comparison of hospitalized patients with ARDS caused by COVID-19 and H1N1. Chest. 2020;158(1):195–205. doi: 10.1016/j.chest.2020.03.032. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ryan Logan, Lam Carson, Mataraso Samson, Allen Angier, Green-Saxena Abigail, Pellegrini Emily, Hoffman Jana, Barton Christopher, McCoy Andrea, Das Ritankar. Mortality prediction model for the triage of COVID-19, pneumonia, and mechanically ventilated ICU patients: A retrospective study. Ann. Med. Surg. (Lond). 2020;59:207–216. doi: 10.1016/j.amsu.2020.09.044. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Zhao Zirun, Chen Anne, Hou Wei, Graham James M., Li Haifang, Richman Paul S., Thode Henry C., Singer Adam J., Duong Tim Q., Adrish Muhammad. Prediction model and risk scores of ICU admission and mortality in COVID-19. Plos One. 2020;15(7):e0236618. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0236618. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.E.B. Hodcroft, CoVariants: SARS-CoV-2 Mutations and Variants of Interest. https://covariants.org/per-country, 2021 (accessed 06 September 2021).

- 17.SeqCOVID, NextSpain: Spanish site for Nextstrain: Consortium for Genomic Epidemiology of Pathogens, 2021 (accessed 06 September 2021).

- 18.O'Toole Áine, Hill Verity, Pybus Oliver G., Watts Alexander, Bogoch Issac I., Khan Kamran, Messina Jane P., Tegally Houriiyah, Lessells Richard R., Giandhari Jennifer, Pillay Sureshnee, Tumedi Kefentse Arnold, Nyepetsi Gape, Kebabonye Malebogo, Matsheka Maitshwarelo, Mine Madisa, Tokajian Sima, Hassan Hamad, Salloum Tamara, Merhi Georgi, Koweyes Jad, Geoghegan Jemma L., de Ligt Joep, Ren Xiaoyun, Storey Matthew, Freed Nikki E., Pattabiraman Chitra, Prasad Pramada, Desai Anita S., Vasanthapuram Ravi, Schulz Thomas F., Steinbrück Lars, Stadler Tanja, Parisi Antonio, Bianco Angelica, García de Viedma Darío, Buenestado-Serrano Sergio, Borges Vítor, Isidro Joana, Duarte Sílvia, Gomes João Paulo, Zuckerman Neta S., Mandelboim Michal, Mor Orna, Seemann Torsten, Arnott Alicia, Draper Jenny, Gall Mailie, Rawlinson William, Deveson Ira, Schlebusch Sanmarié, McMahon Jamie, Leong Lex, Lim Chuan Kok, Chironna Maria, Loconsole Daniela, Bal Antonin, Josset Laurence, Holmes Edward, St. George Kirsten, Lasek-Nesselquist Erica, Sikkema Reina S., Oude Munnink Bas, Koopmans Marion, Brytting Mia, Sudha rani V., Pavani S., Smura Teemu, Heim Albert, Kurkela Satu, Umair Massab, Salman Muhammad, Bartolini Barbara, Rueca Martina, Drosten Christian, Wolff Thorsten, Silander Olin, Eggink Dirk, Reusken Chantal, Vennema Harry, Park Aekyung, Carrington Christine, Sahadeo Nikita, Carr Michael, Gonzalez Gabo, de Oliveira Tulio, Faria Nuno, Rambaut Andrew, Kraemer Moritz U.G. Tracking the international spread of SARS-CoV-2 lineages B.1.1.7 and B.1.351/501Y-V2 [version 1; peer review: 3 approved] Wellcome Open Res. 2021;6:121. doi: 10.12688/wellcomeopenres10.12688/wellcomeopenres.16661.1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.International Federation of Clinical Chemistry and Laboratory Medicine, Biochemical monitoring of COVID-19 patients. https://www.ifcc.org/resources-downloads/ifcc-information-guide-on-covid-19-introduction/5-biochemical-monitoring-of-covid-19-patients/, 2020 (accessed 18 July 2021).

- 20.Lemeshow S., Hosmer D.W., Jr A review of goodness of fit statistics for use in the development of logistic regression models. Am. J. Epidemiol. 1982;115:92–106. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a113284. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Fawcett Tom. An introduction to ROC analysis. Pattern Recognit. Lett. 2006;27(8):861–874. doi: 10.1016/j.patrec.2005.10.010. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hanley J A, McNeil B J. The meaning and use of the area under a receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curve. Radiology. 1982;143(1):29–36. doi: 10.1148/radiology.143.1.7063747. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Puga Jorge López, Krzywinski Martin, Altman Naomi. Points of significance: Bayes' theorem. Nat. Methods. 2015;12(4):277–278. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.3335. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.DeLong E.R., DeLong D.M., Clarke-Pearson D.L. Comparing the areas under two or more correlated receiver operating characteristic curves: A nonparametric approach. Biometrics. 1988;44:837–845. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Tao Chen Di Wu Huilong Chen Weiming Yan Danlei Yang Guang Chen Ke Ma Dong Xu Haijing Yu Hongwu Wang Tao Wang Wei Guo Jia Chen Chen Ding Xiaoping Zhang Jiaquan Huang Meifang Han Shusheng Li Xiaoping Luo Jianping Zhao Qin Ning Clinical characteristics of 113 deceased patients with coronavirus disease 2019: retrospective study m1091 10.1136/bmj.m1091 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 26.Berenguer Juan, Ryan Pablo, Rodríguez-Baño Jesús, Jarrín Inmaculada, Carratalà Jordi, Pachón Jerónimo, Yllescas María, Arriba José Ramón, Aznar Muñoz Esther, Gil Divasson Pedro, González Muñiz Patricia, Muñoz Aguirre Clara, López Juan Carlos, Ramírez-Schacke Margarita, Gutiérrez Isabel, Tejerina Francisco, Aldámiz-Echevarría Teresa, Díez Cristina, Fanciulli Chiara, Pérez-Latorre Leire, Parras Francisco, Catalán Pilar, García-Leoni María E., Pérez-Tamayo Isabel, Puente Luis, Cedeño Jamil, Berenguer Juan, Díaz Menéndez Marta, de la Calle Prieto Fernando, Arsuaga Vicente Marta, Trigo Esteban Elena, Lago Núñez Mª del Mar, de Miguel Buckley Rosa, Cadiñaños Loidi Julen, Busca Arenzana Carmen, Mican Alfredo, Mora Rillo Marta, Ramos Ramos Juan Carlos, Loeches Yagüe Belén, Bernardino de la Serna José Ignacio, García Rodríguez Julio, Arribas López José Ramón, Such Diaz Ana, Álvaro Alonso Elena, Izquierdo García Elsa, Torres Macho Juan, Cuevas Tascon Guillermo, Troya García Jesús, Mestre Gómez Beatriz, Jiménez González de Buitrago Eva, Fernández Jiménez Inés, Tebar Martínez Ana Josefa, Brañas Baztán Fátima, Valencia de la Rosa Jorge, Pérez Butragueño Mario, Alvarado Blasco Marta, Ryan Pablo, Sepúlveda Berrocal Mª Antonia, Yera Bergua Carmen, Toledano Sierra Pilar, Cano Llorente Verónica, Zafar Iqubal-Mirza Sadaf, Muñiz Gema, Martín Pérez Inmaculada, Mozas Moriñigo Helena, Alguacil Ana, García Butenegro María Paz, Peláez Ballesta Ana Isabel, Morcillo Rodríguez Elena, Goikoetxea Agirre Josune, Blanco Vidal María José, Nieto Arana Javier, del Álamo Martínez de Lagos Mikel, Pérez Hernández Isabel A., Pérez Zapata Inés, Silvariño Fernández Rafael, Ugalde Espiñeira Jon, Asensi Álvarez Víctor, Suárez Pérez Lucia, Suárez Diaz Silvia, Yllera Gutiérrez Carmen, Boix Vicente, Díez Martínez Marcos, Carreres Candela Melissa, Gómez-Ayerbe Cristina, Sánchez-Lora Javier, Velasco Garrido José Luis, López-Jódar María, Santos González Jesús, Ruiz Aragón Jesús, Virto Peña Ianire, Alende Castro Vanessa, Brea Aparicio Ruth, Vega Molpeceres Sonia, Pons Viñas Estel, del Río Pérez Oscar, Valero Rovira Silvia, Villar-García Judit, Gómez-Junyent Joan, Knobel Hernando, Cánepa María Cecilia, Castañeda Espinosa Silvia, Sorli Redò Luisa, Güerri-Fernández Roberto, Milagro Montero María, Horcajada Juan Pablo, García Vázquez Elisa, Moral Escudero Encarnación, Hernández Torres Alicia, García Almodóvar Esther, Sáez Barberá Carmen, Karroud Zineb, Hernández Quero José, Vinuesa García David, García Fogeda José Luis, Peregrina José Antonio, Novella Mena María, Hernández Gutiérrez Cristina, Sanz Moreno José, Pérez Tanoira Ramón, Sierra Rodríguez Rodrigo, Alonso Menchén David, Gutiérrez García Aida, Arranz Caso Alberto, Cuadros González Juan, Álvarez de Mon Soto Melchor, Díaz de Brito Fernández Vicente Ferrer, Sanmarti Vilamala Montserrat, Gabarrell Pascuet Aina, Molina Morant Daniel, España Cueto Sergio, Cámara Fernández Jonathan, Sabater Gil Albert, Muñoz López Laura, Sáez Escolano Paula, Bejarano Tello Esperanza, Sempere Alcocer Marco Antonio, Álvarez Martin Salvador, De los Santos Gil Ignacio, García-Fraile Lucio, Sampedro Núñez Miguel, Barrios Blandino Ana, Rodríguez Franco Carlos, Useros Brañas Daniel, Villa Martí Almudena, Oliver Ortega Javier, Costanza Espiño Álvarez Alexia, Sanz Sanz Jesús, Rexach Fumaña María, Abascal Cambras Ivette, Pérez Jaén Ana del Cielo, Sala Jofre Clara, Casas Rodríguez Susana, Tortajada Alamilla Cecilia, Oltra Carmina, Masiá Canuto Mar, Gutiérrez Rodero Félix, Ferrer Ribera Ana, Bea Serrano Carlos, Pedromingo Kus Miguel, Garcinuño María Ángeles, Fiorante Silvana, Pérez Pinto Sergio, Hernández Machín Pilar, Alastrué Violeta Alba, Fariñas Álvarez María Carmen, González Rico Claudia, Arnaiz de las Revillas Francisco, Calvo Jorge, Gozalo Mónica, Mora Gómez Francisco, Milagro Beamonte Ana, Latorre-Millán Miriam, Rezusta López Antonio, Martínez Sapiña Ana, Meije Yolanda, Duarte Borges Alejandra, Pareja Coca Julia, Clemente Presas Mercedes, Losa García Juan Emilio, Vegas Serrano Ana, Pérez-Rodríguez M. Teresa, Pérez González Alexandre, Belhassen-García Moncef, Rodríguez-Alonso Beatriz, López-Bernus Amparo, Carbonell Cristina, Torres Perea Rafael, Cantón de Seoane Juan, Alonso Blanca, Kamal Sara Lidia, Cajuela Lucia, Roa David, Cervero Miguel, Oreja Alberto, Avilés Juan Pablo, Martín Lidia, Pelegrín Senent Iván, Rouco Esteves Marques Rosana, Parra Ruiz Jorge, Ramos Sesma Violeta, Abadia Otero Jessica, Salillas Hernando Juan, Torres Sánchez del Arco Robert, Torralba González de Suso Miguel, Serrano Martínez Alberto, Gilaberte Reyzábal Sergio, Pacheco Martínez-Atienza Marina, Liébana Gómez Mónica, Fernández Rodríguez Sara, Varela Plaza Álvaro, Calvo Sánchez Henar, Martínez Martín Patricia, González- Ruano Patricia, Malmierca Corral Eduardo, Rábago Lorite Isabel, Pérez-Monte Mínguez Beatriz, García Flores Ángeles, Comas Casanova Pere, Sirisi Merce, Rojas Richard, Díaz de Tuesta del Arco José Luis, Figueroa Cerón Ruth, González Sarria Ander, Alemán Valls Remedios, Alonso Socas María del Mar, Sanz Peláez Oscar, Mohamed Ramírez Karim, Riera Jaume Melchor, Vilchez Helem Haydee, Albertí Francesc, Cañabate Ana Isabel, Moreno Cuerda Víctor J., Álvarez Kaelis Silvia, Álvarez Zapatero Beatriz, García García Alejandro, Isaba Ares Elena, Morcate Fernández Covadonga, Pérez Rodríguez Andrea, Ramos Merino Lucía, Castelo Corral Laura, Rodríguez Mahía María, González Bardanca Mónica, Sánchez Vidal Efrén, Míguez Rey Enrique, De la Torre Lima Javier, García de Lomas Guerrero José Mª, Morte Elena, Loscos Silvia, Camón Ana, Gómez García Lucía, Boix Palop Lucia, Dietl Gómez-Luengo Beatriz, Pedrola Gorrea Iris, Blasco Claramunt Amparo, López Mestanza Cristina, Fraile Villarejo Esther, Tosco Núñez Tomás, Aroca Ferri María, Algado Rabasa José Tomas, Garijo Saiz Ana María, Amador Prous Concepción, Baño Jesús Rodriguez, Retamar Pilar, Valiente Adoración, López-Cortés Luis E., Sojo Jesús, Gutiérrez-Gutiérrez Belén, Bravo-Ferrer José, Salamanca Elena, Palacios Zaira R., Pérez-Palacios Patricia, Peral Enrique, Pérez de León José Antonio, Sánchez-Gómez Jesús, Marín-Barrera Lucía, García-Jiménez Domingo, Carratalà Jordi, Abelenda-Alonso Gabriela, Ardanuy Carmen, Bergas Alba, Cuervo Guillermo, Domínguez María Ángeles, Fernández-Huerta Miguel, Gudiol Carlota, Lorenzo-Esteller Laia, Niubó Jordi, Pérez-Recio Sandra, Podzamczer Daniel, Pujol Miquel, Rombauts Alexander, Trullen Núria, Salavert Lletí Miguel, Castro Hernández Iván, Hernández Belmonte Adriana, Martínez Goñi Raquel, Navarro Vilasaró Marta, Calzado Isbert Sonia, Cervantes García Manuel, Gomila Grange Aina, Gasch Blasi Oriol, Machado Sicilia María Luisa, Van den Eynde Otero Eva, Falgueras López Luis, Navarro Sáez María del Carmen, Martínez Esteban, Marcos Mª Ángeles, Mosquera Mar, Blanco José Luis, Laguno Montserrat, Rojas Jhon, González-Cordón Ana, Inciarte Alexy, Torres Berta, De la Mora Lorena, Soriano Alex, Martínez Macias Olalla, Pérez Doñate Virginia, Cabello Úbeda Alfonso, Carrasco Antón Nerea, Álvarez Álvarez Beatriz, Petkova Saiz Elizabet, Górgolas Hernández-Mora Miguel, Prieto Pérez Laura, Carrillo Acosta Irene, Heili Frades Sara, Villar Álvarez Felipe, Fernández Roblas Ricardo, Milicua Muñoz José María, Fernández Espinilla Virginia, Dueñas Gutiérrez Carlos Jesús, Hernán García Cristina, González-Romo Fernando, Merino Amador Paloma, Rueda López Alba, Martínez Jordán Jorge, Medrano Pardo Sara, Díaz de la Torre Irene, Posada Franco Yolanda, Delgado-Iribarren Alberto, López-Contreras González Joaquín, Pascual Alonso Pablo, Pomar Solchaga Virginia, Rabella García Nuria, Benito Hernández Natividad, Domingo Pedrol Pere, Bonfill Cosp Xavier, Padrós Selma Rafael, Puig Campmany Mireia, Mancebo Cortés Jordi, Gurguí Ferrer Mercè, Íñigo Pestaña Melania, Pérez García Alejandra, Sorní Moreno Patricia, Izko Gartzia Nora, Membrillo de Novales Francisco Javier, Simón Sacristán María, Zamora Cintas Maribel, Martínez Martínez Yolanda, Fernández-González Pablo, Alcántara Nicolás Francisco, Aguirre Vila-Cora Alejandro, López Tizón Elena, Ramírez-Olivencia Germán, Estébanez Muñoz Miriam, Sáez de Adana Arróniz Ester, Portu Zapirain Joseba, Gainzarain Arana Juan Carlos, Ortiz de Zárate Ibarra Zuriñe, Moran Rodríguez Miguel Ángel, Canut Blasco Andrés, Hernáez Crespo Silvia, Balerdi Sarasola Leire, Morales García Cristina, Corral Saracho Miguel, Valcarce González Zeltia, Arenal Andrés Noelia, Rodríguez Tarazona Raquel Elisa, Iglesias Llorente Laura, Loureiro Rodríguez Beatriz, Sánchez Montalvá Adrián, Espinosa Pereiro Juan, Almirante Benito, Miarons Marta, Sellarés Júlia, Larrosa María, García Sonia, Marzo Blanca, Villamarín Miguel, Fernández Nuria, Pérez-Jorge Peremarch Conchita, Resino Foz Elena, Espigares Correa Andrea, Álvarez de Espejo Montiel Teresa, Navas Clemente Iván, Quijano Contreras María Isabel, Nieto Fernández del Campo Luis Alberto, Jiménez Álvarez Guillermo, Guillamón Sánchez Mercedes, García García Josefina, Muñoz Hornero Constanza, Mariño Callejo Ana, Valcarce Pardeiro Nieves, Smithson Amat Alex, Chico Chumillas Cristina, Sánchez Serrano Adriana, García Villalba Eva Pilar, Jiménez Martínez Isabel, Estrada Fernández Guillermo, Lorén Vargas María, Parra Arribas Nuria, Martínez Cilleros Carmen, Villasante de la Puente Aránzazu, García Delange Teresa, Ruiz Rodríguez María José, Robledo del Prado Marta, Abad Almendro Juan Carlos, Muñoz del Rey José Román, Jiménez Álvaro Montaña, Coy Coy Javier, Poquet Catala Inmaculada, Santos Peña Marta, Naranjo Velasco Virginia, Manso Gómez Tamara, Quilez Ágreda Delia, Barbeito Castiñeiras Gema, Domínguez Santalla María Jesús, Mao Martín Laura, Alonso Navarro Rodrigo, Ampuero Martinich Jose David, Barrós González Raquel, Galindo Martín María Aránzazu, Herrera Pacheco Lourdes, Martínez Avilés Rocío, Rodrigo González Sara, Rodríguez Leal Cristóbal Manuel, Romay Lema Eva María, Suárez Gil Roi, Ibarguren Pinilla Maialen, Marimón Ortiz de Zárate José María, Vidaur Tello Loreto, Kortajarena Urkola Xabier, García Gómez Miriam, Aranguren Arostegui Asier, Álvarez de Castro Maria, Martínez Mateu Cintia María, Rodríguez Gómez Francisco, Muñoz Beamud Francisco, Chamarro Martí Elena, Cardona Rivera Merce, Zakariya-Yousef Breval Ismail, Rico Rodríguez Marta, Llenas García Jara, Sánchez Arenas Mª Carmen, Fernández Cruz Ana, Calderón Parra Jorge, López Dosil Marcos, Ramos Martínez Antonio, Múñez Rubio Elena, Callejas Díaz Alejandro, Vázquez Comendador José Manuel, Diego Yagüe Itziar, Expósito Palomo Esther, Anel Pedroche Jorge, Álvarez Franco Raquel, Fernández de Orueta Lucía, Vates Gómez Roberto, Cardona Arias Andrés Felipe, Marguenda Contreras Pablo, Gaspar Alonso-Vega Gabriel, Aranda Rife Elena María, Martínez Cifre Blanca, Roger Zapata Daniel, Martín Rubio Irene, Barbosa Ventura André, Piñero Iván, Bahamonde Carrasco Alberto, Runza Buznego Paula, Talavera García Eva, Lamata Subero Marta, Urrutia Losada Ainhoa, Arteche Eguizabal Lorea, Delgado Sánchez Elisabet, Molina Peinado Virginia, Caro Bragado Sarah, Domínguez de Pablos Gema, Roldán Fontana Carolina, Herrero Rodríguez Carmen, Force Sanmartín Luis, Aranega Raquel, Mera Fidalgo Arantzazu, Toda Savall María Roca, Merchante Gutiérrez Nicolas, León Jiménez Eva María, Del Pozo León José Luís, Serralta Buades Josefa, Cabrera Tejada Ginger Giorgiana, Fernández-Ruiz Mario, Aguado José María, Maestro de la Calle Guillermo, Cisneros José Miguel, Pachón Jerónimo, Aguilar-Guisado Manuela, Aldabó Teresa, Avilés María Dolores, Bueno Claudio, Cordero-Matía Elisa, Escoresca Ana, Gálvez-Benítez Lydia, Infante Carmen, Martín Guillermo, Praena Julia, Roca Cristina, Salamanca Celia, Suárez-Benjumea Alejandro, Vizcarra Pilar, Quereda Carmen, Rodriguez Dominguez Mario José, Gioia Francesca, Norman Francesca, Del Campo Santos, Cantón Moreno Rafael, Oteo Revuelta José Antonio, Santibáñez Sáenz Paula, Cervera Acedo Cristina, Ruiz Martínez Carlos, Blanco Ramos José R., Azcona Gutiérrez José M., García García Concepción, Alba Fernández Jorge, Ibarra Cucalón Valvanera, San Franco Mercedes, Metola Sacristán Luis, Meijide Míguez Héctor, Paulos Viñas Silvia, Menéndez Justo, Villares Fernández Paula, Montes Andújar Lara, Navarro Batet Álvaro, Ferrer Santolaria Anna, Padilla Salazar María de la Luz, Abella Vázquez Lucy, Hayek Peraza Marcelino, García Pardo Antonio, Hernández Carballo Carolina, Ruiz Fernández Andrés Javier, Barrio López Isabel, Martakoush Alí, Rojas-Vieyra Agustín, García Calvo Sonia, Villarreal García-Lomas Mercedes, Vizcaíno Callejón Marta, García García María Pilar, Lérida Urteaga Ana, Carrasco Fons Natalia, María Sanjuan Beatriz, Martín González Lydia, Sanz Zamudio Camilo, Jarrín Inmaculada, Alejos Belén, Moreno Cristina, Rava Marta, Iniesta Carlos, Izquierdo Rebeca, Suárez-García Inés, Díaz Asunción, Ruiz-Alguero Marta, Hernando Victoria. Characteristics and predictors of death among 4035 consecutivelyhospitalized patients with COVID-19 in Spain. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. 2020;26(11):1525–1536. doi: 10.1016/j.cmi.2020.07.024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Aksel Gökhan, İslam Mehmet Muzaffer, Algın Abdullah, Eroğlu Serkan Emre, Yaşar Gökselin Beleli, Ademoğlu Enis, Dölek Ümit Can. Early predictors of mortality for moderate to severely ill patients with Covid-19. Am. J. Emerg. Med. 2021;45:290–296. doi: 10.1016/j.ajem.2020.08.076. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Assaf Dan, Gutman Ya’ara, Neuman Yair, Segal Gad, Amit Sharon, Gefen-Halevi Shiraz, Shilo Noya, Epstein Avi, Mor-Cohen Ronit, Biber Asaf, Rahav Galia, Levy Itzchak, Tirosh Amit. Utilization of Machine-learning models to accurately predict the risk for critical COVID-19, Intern. Emerg. Med. 2020;15(8):1435–1443. doi: 10.1007/s11739-020-02475-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Ashis Kumar Das Shiba Mishra Saji Saraswathy Gopalan Predicting COVID-19 community mortality risk using machine learning and development of an online prognostic tool 8 2020 e10083 10.7717/peerj.10083 10.7717/peerj.10083/fig-1 10.7717/peerj.10083/fig-2 10.7717/peerj.10083/table-1 10.7717/peerj.10083/table-2 10.7717/peerj.10083/supp-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 30.Worster Andrew, Bledsoe R. Daniel, Cleve Paul, Fernandes Christopher M., Upadhye Suneel, Eva Kevin. Reassessing the methods of medical record review studies in emergency medicine research. Ann. Emerg. Med. 2005;45(4):448–451. doi: 10.1016/j.annemergmed.2004.11.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]