Abstract

Cancer survivors’ well-being is threatened by the risk of cancer recurrence and the increased risk of chronic diseases resulting from cancer treatments. Improving lifestyle behaviors attenuates these risks. Traditional approaches to lifestyle modification (i.e., counseling) are expensive, require significant human resources, and are difficult to scale. Mobile health interventions offer a novel alternative to traditional approaches. However, to date, systematic reviews have yet to examine the use of mobile health interventions for lifestyle behavior improvement among cancer survivors. The objectives of this integrative review were to synthesize research findings, critically appraise the scientific literature; examine the use of theory in intervention design; and identify survivors’ preferences in using mobile health interventions for lifestyle improvement. Nineteen articles met eligibility requirements. Only two studies used quantitative methods (no RCTs). Study quality was low and only one study reported the use of theory in app design. Unfortunately, the evidence has not yet sufficiently matured, in quality or in rigor, to make recommendations on how to improve health behaviors or outcomes. However, six themes emerged as important considerations for intervention development for cancer survivors (app features/functionality, social relationships/support, provider relationships/support, app content, app acceptability, and barriers to use). These findings underscored the need for rigorous, efficacy studies before the use of mobile health interventions can be safely recommended for cancer survivors.

Keywords: Review, Cancer Survivors, Healthy Lifestyle, Telemedicine, Mobile Health, mHealth

Introduction

Cancer is the second leading cause of death globally.1 While better treatment and earlier diagnoses are increasing survivors’ lifespans, cancer recurrence and the prevalence of cardiovascular disease resulting from cancer treatments limits life expectancy.2 Improving lifestyle behaviors, such as diet and physical activity, attenuates the risk of both. 3,4 Despite internationally consistent guidelines promoting lifestyle improvement for survivors, the majority fail to meet goals for healthy behaviors. Lack of cost-effective, sustainable interventions further complicates the problem.5 Mobile health (mHealth) interventions may offer an alternative. mHealth may be able to target behaviors that have historically been difficult for clinicians to treat or have remained resistant to traditional clinician-to-patient interventions. mHealth interventions can ameliorate burdens associated with time, workflow,6 and a lack of resources,7 and may increase the reach of lifestyle intervention programs by transcending time and geographical distance. Moreover, mHealth interventions can be tailored to individual patients’ needs, improving the patient experience and thus improving patient engagement.8 However, to date, systematic reviews have yet to examine the effect of mHealth interventions for lifestyle behavior change in cancer survivors.

Preliminary search activity indicated a dearth of quantitative research on mHealth interventions for lifestyle improvement in cancer survivors, rendering a systematic review with meta-analysis infeasible. In fact, no randomized, controlled trials were identified. Therefore, an integrative review was conducted to develop a comprehensive understanding of the state of the science.9 The overall purpose of this review was to synthesize the evidence on the use of mHealth interventions for lifestyle behavior change in cancer survivors. The specific objectives included: (1) identify and synthesize research using mHealth apps for lifestyle behavior modification in cancer survivors; (2) critically appraise the scientific literature; (3) determine the use of theory in mHealth app development and testing; and (4) identify cancer survivors’ prefererred features and functionality when using mHealth apps for lifestyle behavior change.

Methods

Detailed methods for conducting this review have been previously reported (PROSPERO ID: CRD42017077298). Briefly, the review process was guided by Whittemore and Knafl’s framework9 and the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Review and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) guidelines.10 The PICOTS format11,12 – Population, Intervention, Comparator, Outcomes, Timing, and Setting – guided the development of our research questions, goals, search strategies, eligibility criteria, and data extraction elements.

Articles published in English or translated into English, between January 1, 2007 and April 15, 2019 were eligible, as smartphones were not available before 2007.13 Studies integrating 3 domains were included: (1) mHealth, (2) lifestyle behavior change, and (3) cancer survivors. We defined mHealth as health practices supported by mobile devices14 that are active and carried on the person throughout the day.15 Lifestyles of interest included diet, physical activity (PA), tobacco use, stress (including anxiety, distress, and depression), and substance misuse. The term “cancer survivor” referred to anyone who had been diagnosed with cancer, from the time of diagnosis throughout his or her lifespan.16

We searched nine databases and conducted ancestry searches of bibliographies. Key search terms were identified for the three domains. EHealth, telehealth, telemedicine, and mobile phone were also included in the searches, as these constructs are evolving and have been the source of confusion for experts and lay individuals alike.13

Titles, authors, abstracts, and other manuscript details were downloaded into reference management software for analysis. Pairs of authors screened titles and abstracts for eligibility, which was followed by screening of full texts. Authors resolved disagreements through discussion and in consultation with the second author.

Study quality was assessed again by pairs of authors, using tools that were specific to the study design including Cochrane guidelines,17 Effective Public Health Practice Project Quality Assessment Tool (EPHPP),18,19 Joanna Briggs Institute (JBI) quality appraisal tool, CONSORT extension for pilot trials,20 and other feasibility criteria. Final appraisal scores were assessed as strong, moderate, or weak. All eligible articles were included in the review regardless of quality rating.

Pairs of authors independently extracted information using a customized data extraction form previously pilot tested. Authors compared results and discussed findings. To achieve our goal of identifying theoretical underpinnings of the apps (the use of theory to inform variable selection, scientific evaluation, and app development), we extracted data elements based on the theory-use, coding scheme developed and validated by Michie and Prestwich.21

Results

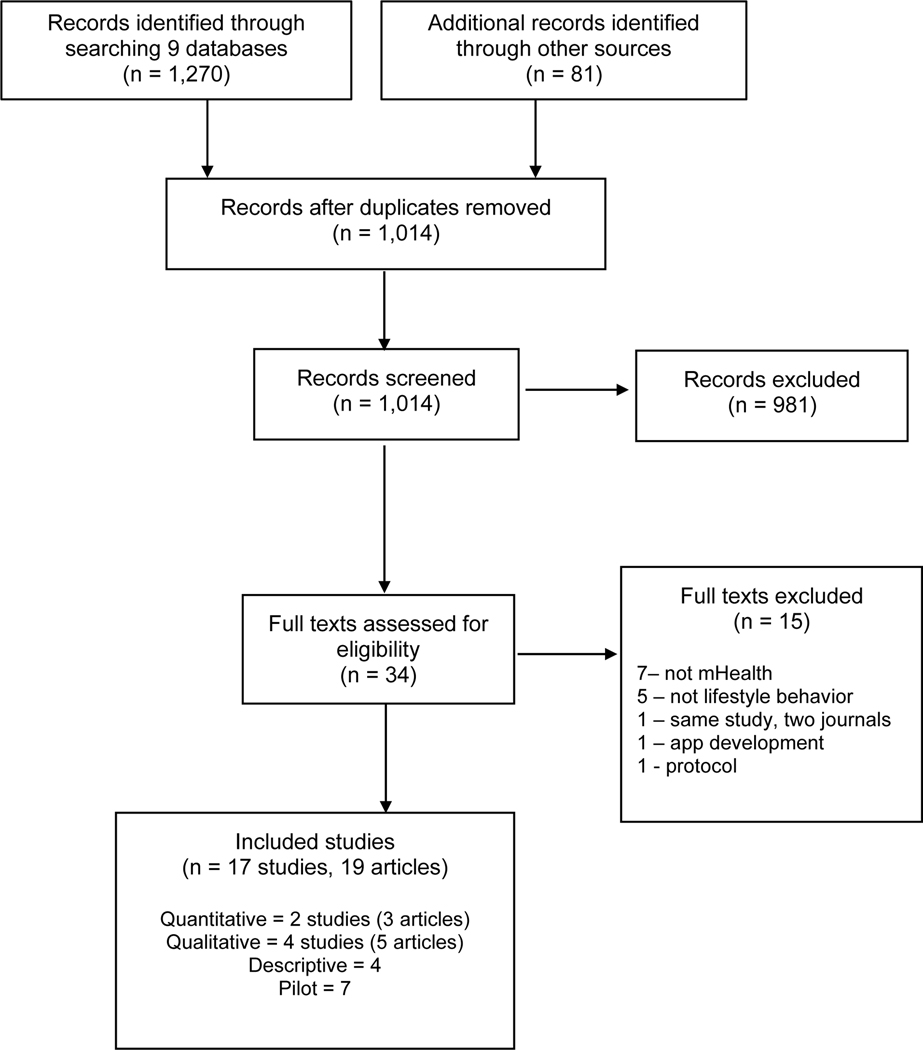

Nineteen articles (17 studies) were included for review (Figure 1).22–40 The quasi-experimental study by Uhm et al.32 and the secondary analysis by Park et al.34 represented results from the same study. Additionally, results from one qualitative study were reported twice 28,35 and were considered together. Articles were published between 2015 and 2019, with the majority (n = 14) published in 2017 or after. The total included 2 quasi-experimental studies,32,34 4 qualitative studies,22,24,37,38 7 pilot studies,25,27,30,31,33,36,39 and 4 descriptive studies.23,26,28,29 See Table, Supplemental Digital Content 1, for detailed sample characteristics.

Figure 1.

PRISMA Flow Diagram

Ten articles reported on the use of mHealth interventions while the remaining nine described mHealth features and functions important to survivors (see Table, Supplemental Digital Content 2 for details of each included article). Seventeen (89%) articles reported on physical activity (PA) or sedentary behavior.22–30,32–35,37–40 However, most focused on a combination of PA with one or more of the following: diet, weight/body mass index (BMI), sleep, mood, well-being, quality of life (QoL), symptoms (e.g., pain, fatigue), smoking, and alcohol use. The two remaining studies included in this review addressed stress.31,36

Patient and Study Characteristics

Seventeen articles reported survivors’ cancer disease type, with breast cancer survivors over-represented in the sample −14 articles (see Table, Supplemental Digital Content 1, Sample Characteristics). Most survivors in these studies were white females with some college education. One thematic analysis included only older prostate cancer survivors (M = 73.5 years old, SD = 8.1),24 and one descriptive study included only teenage and young adult cancer survivors (M = 20 years old, SD = 2.85).29 The age of the survivors in the remaining studies ranged from 45 years old (SD = 9.4)30 to 70 years old (SD = 7.73).34

Critical Appraisal

The overall quality of the studies in this review was assessed as weak, except for three pilot studies (see Table, Supplemental Digital Content 1, Sample Characteristics). Two were appraised as moderate in quality,30,36 and one ranked as strong.33 Generally, the pilot studies examined the feasibility of an intervention, specifically with regard to processes (e.g., recruitment, randomization, and retention), resources (e.g., time and budget), and science (e.g., intervention implementation, dose, and duration). Several informed modifications in study design, methods, or intervention for use in a more robust hypothesis testing study.

Theory Use

This integrative review identified an overall lack of theory-based design, development, and evaluation of mHealth interventions used by cancer survivors to modify lifestyle behaviors. Only one study included in this review reported the use of theory in association with design and testing of the mHealth intervention.33

mHealth Interventions addressing Mental Health in Cancer Survivors

Researchers in two pilot studies included this review delivered stress reduction interventions.31,36 The nature of these pilot studies prevented generalizations about the use of mHealth for stress reduction in cancer patients as these studies were not designed for hypotheses testing nor powered to determine efficacy. Researchers in three other pilot studies delivered interventions focused on PA, diet, and weight loss, in addition to evaluating outcomes associated with stress, anxiety, and depression. 27,30,39 Study feasibility (e.g., recruitment, study uptake, engagement) was the focus of the study outcomes. Survivors’ uptake, adherence, and satisfaction suggested feasibility of larger efficacy studies. The exploratory nature of these pilot studies limited our ability to generalize about the ability of the mHealth intervention to improve cancer survivors mental health; however preliminary efficacy trended in a positive direction.

mHealth Interventions Addressing Physical Activity in Cancer Survivors

Seven intervention studies (5 pilot and 2 quasi-experimental) delivered a PA intervention, either alone25,32,40 or in combination with diet and weight loss.27,30,33,39 Primary outcomes varied based on study design. For example, the pilot studies identified intervention feasibility (e.g., recruitment, adherence, study uptake, engagement) as the primary outcome whereas self-reported physical activitywas the primary outcome in quasi-experimental study (2 manuscripts). All pilot studies reported feasilibty of moving toward a larger efficacy study. Additionally, pilot study authors reported preliminary efficacy in PA, QoL, and weight loss. Four study teams developed their apps specifically for their research,25,32,39,40 while the other investigators used or modified commercially-available apps.

Among this group of studies, heterogeneity in criteria used to measure PA makes generalizations difficult. All PA interventions differed in the type of exercise, dose, duration, frequency, and delivery method. For example, one study included a face-to-face exercise session,32 while others relied on content provided by commercially-available apps.30 As before, these pilot studies were not designed to determine intervention efficacy.

mHealth Interventions Addressing Diet in Cancer Survivors

Only three of the 19 articles included in this review reported including a dietary component in the application. All three were pilot studies and included PA as part of a weight-loss intervention.27,33,39 Two studies used commercially-available apps and one used an app specifically developed for the study. Investigators in one study asked survivors to log diet information into a commercially-available app, limit carbohydrate consumption to 70 grams per day, and increase fiber intake to 30 grams per day.27 Investigators measured macronutrients and calories at baseline and at 1-week intervals over 4 weeks. No dietary differences were noted for any of the macronutrients, or for caloric consumption between baseline and the end of the 4-week study. However, reductions were noted between pre- and post-intervention weight and waist circumference. QoL and weight self-efficacy scores improved.

Ferrante and colleagues33 conducted a 6-month, randomized controlled feasibility trial using a commercially-available app and fitness tracker to improve weight management in African-American breast cancer survivors. Survivors were randomized to an intervention group using a mHealth app and a fitness tracker versus a wait-list tracker only control group. Accrual, retention, adherence, and acceptability outcomes demonstrated the feasibility of a larger trial. Weight and BMI decreased in both groups with no between-group differences. However, intervention participants reduced waist circumference, decreased caloric consumption, and improved healthy eating strategies. Interestingly, the number of days logging food per week was associated with decreased waist circumference. Weight loss was maintained for the 12 months of the study.

In the third dietary pilot study identified in this review, investigators developed a mHealth app to improve accountability and weight control in breast cancer survivors.39 The study investigated feasibility, participant adherence, and usability of the mHealth app. This single-arm trial was conducted over 4 weeks. Researchers oriented survivors to the key features of the app: nutrient intake, physical activity, and well-being. A registered dietitian designed personal goals around nutrient intake and PA, and interacted with the survivors through the app. All data were self-reported. Eighty percent of the survivors met the adherence criteria and usability was deemed to be better-than-acceptable based on the System Usability Scale.41 The exploratory endpoint of weight loss averaged 2 pounds but ranged from a weight gain of 4 pounds to a loss of 10.6 pounds. In addition, survivors interacted with the dietitian, on average, once daily throughout the length of the study. One-third of the interactions were initiated by the survivors and two-thirds by the dietitian. Preliminary results suggested a correlation between weight loss and the average daily use of the mHealth app. The nature of the included pilot studies prevented generalization about study efficacy.

Overall, the heterogeneity of study design, study outcomes, and intervention type of the included pilot studies limited our ability to synthesize the evidence in a meaningful manner. However, all studies demonstrated the feasibility to move to larger hypothesis driven studies.

Qualitative and Descriptive Results

As with the quantitative and pilot studies reviewed, PA (or sedentary behavior) was the focus or a component of the qualitative and descriptive studies in this review.22–24,26,28,29,35,37,38 Overall, these studies described cancer survivors’ information needs, preferences in intervention delivery, and preferences in mHealth app features. Survivors’ perceptions were synthesized into six common themes outlined in Table 1: (1) Preferable App Functionality & Features, (2) Social Relationships & Support, (3) Provider Relationships, Support & Communications, (4) Content, (5) Acceptability, and (6) Barriers to Use. Results from the three mixed-methods pilot studies supported these same themes and noted the importance of incorporating survivors’ perceptions in app redesign.25,30,33 Survivors suggested that apps offer reliable content, individual and cancer type tailoring, visual exercise demonstrations, and a conduit for peer social support. Social Relationships with peers and family and sharing information (including with healthcare providers and healthcare systems) proved to be the most valuable to survivors and was mentioned most often.

Table 1.

Themes of Survivors’ Perceptions

| Themes |

|---|

| 1. App Functionality and Features |

| • Track survivor data and trends |

| • Personalized, customized, tailored, and individualized |

| • Video features |

| • Type of PA or program |

| • Delivery model |

| • Goals |

| • Feedback |

| • Context |

| • Other desired features |

| 2. Social Relationships and Support |

| • Peer support |

| • Family and friends support |

| 3. Provider Relationships, Support, and Communication |

| • Trusted, knowledgeable, caring, safe, and accurate |

| • Tone |

| 4. Content |

| • Trusted and reliable source |

| • Evidence-based and up to date |

| • Engaging, inspirational, and visually appealing |

| • Educational content |

| 5. Acceptability |

| • Type of programs |

| • Technology |

| • Lifestyle behavior of interest |

| 6. Barriers to Use |

| • Survivor-centered barriers, perceived and actual |

| • Systems barriers |

Less consensus existed among survivors about how to deliver social support. Some survivors suggested the integration of social media into their apps, while others wanted limited and controlled sharing (only family and close friends) on a private network. Others were less interested in sharing but wanted to hear success stories from survivors like themselves.. Results from two different studies 22,28 suggested that few survivors desired to participate in competitions (e.g., highest weekly step total) or to share their information to compete.

Survivors’ interest in mHealth lifestyle interventions is increasing. Using data collected in 2010 (only 3 years after the release of the first smartphone and 2 years after the release of the first mHealth app),26 Martin and colleagues26 explored relationships between lifestyles (PA, diet, weight) and intervention delivery modes (smartphone, computer, clinic, telephone). Survivors indicated little or no interest in using smartphones to improve their diet, exercise, or weight (75.5%). However, data from the more recent studies included in this review support increasing interest over time. For example, in 2017, Kessel et al.23 reported that the majority of survivors were interested in using apps for health and symptom tracking. Additionally, in 2017, Philips et al.28 reported that 68% of survivors were interested in using mHealth apps. Most of the survivors (84.6%) were interested in remotely delivered exercise counseling, and 79.5% were interested in remotely delivered exercise interventions. Pugh and colleagues29 reported similar findings with 85% of young cancer survivors (age range 13 to 25 years old) preferring lifestyle behavior advice (PA, diet, smoking, alcohol consumption) delivered online or via mHealth applications.

Discussion

This review examined the evidence surrounding cancer survivors’ use of mHealth interventions for lifestyle modification. Of the studies reviewed, 10 reported on the use of mHealth interventions while the remaining nine described features and functions important to surivors. All but 2 of the quantitative studies were pilot/feasibility studies and no RCTs were identified. Overall, the evidence has not yet sufficiently matured, in quality or in rigor to make generalization or recommendations on how to improve health outcomes, using mHealth interventions, among cancer survivors. However, the feasibility of moving toward larger efficacy trials with some of the mHealth interventions identified is promising.

As with the studies included in this review, mHealth lifestyle interventions often involve multiple components and require substantial iterative development in the usability and feasibility phases of the research trajectory, traditional RCT research designs may need to be adapted. Interventions that are individually customizable to meet the changing needs of patients over time add an increased level of complexity to research study designs. Research methods and designs from engineering and computer science may be able to overcome such challenges, as such methods are uniquely suited to problems of complex systems and decision making in systems that change over time.42 Such methods and designs (e.g., adaptive intervention, dynamical systems, control engineering methods) have begun to be described in the literature for health behavior change.42

Lifestyle Interventions

Survivorship clinical practice guidelines from the National Comprehensive Cancer Network underscore the importance of diet, exercise, and stress reduction for weight management to improve health outcomes among cancer survivors.43 For example, among breast cancer survivors, an increase in weight is associated with increased risk of fatigue,44,45 functional decline,44,45 lymphedema,46 heart disease,47,48 diabetes,48,49 and poorer QoL,44,45 in addition to increase risk of cancer recurrence. Weight reduction through the adoption of a healthy diet and exercise is essential for maintaining health as a cancer survivor.

To address these survivorship needs, researchers in the studies identified for this review delivered multi-component interventions. Seven demonstrated trends in preliminary efficacy in improving PA. Researchers identifying weight loss as an outcome using diet and PA interventions, report mixed results. While some survivors lost weight, between-group differences were not detected and pre- to post-intervention weight loss was not significant. Moreover, in the quasi-experimental study conducted by Lee et al.,34 both control and intervention groups had significant weight gain.

In studying multi-component interventions, difficulty arises in determining the individual effects of the components (e.g., goal setting versus cueing) on health outcomes (e.g., PA level). For example, it is difficult to identify whether the goal setting for PA or the cueing to eat a healthier diet is more significant in helping the patient to lose weight. Additionally, other confounding factors, such as greater interaction with the healthcare system or app functionality, may be responsible for changes (or a lack thereof) in survivors’ health. Innovative methods are needed to rigorously test multi-component mHealth interventions in cancer survivors. In sum, findings from the included studies are promising, but larger, rigorous efficacy trials are needed.

Survivors’ Preferences in Using mHealth

Taken together, the findings of this integrative review suggest the importance of 6 themes in understanding survivors’ preferences in using mHealth interventions: 1) App Functionality, 2) Social Relationships, 3) Provider Relationships and Communications, 4) Content, 5) Acceptability, and 6) Barriers to mHealth Use. Interestingly, two of these six themes have to do with relationships. While these six themes are important to survivors, how to operationalize and test them and how each affects behavior change remains unknown. Equally unknown is the type of engagement, frequency, intensity, and duration needed to improve short- and long-term health outcomes. The techniques and functionalities that are important in helping survivors to initiate healthy behaviors, and the techniques that are essential in maintaining and sustaining healthy behaviors over time are also unknown but remain imperative considerations in developing and evaluating mHealth interventions. More qualitative research is needed, but the themes presented in Table 1 and the accompanying descriptors offer a starting point from the survivors’ perspective. More details about these themes can be found in the Table, Supplemental Digital Content 3, outlining Themes, Categories, Descriptions.

The perspectives of other stakeholders, such as oncology providers (e.g., dieticians, nurse practitioners, physical therapists, physicians) administrators, and healthcare technology experts, should be examined before mHealth apps and other supportive digital technologies or platforms are designed and implemented. Recent work examining oncologists’ perceptions around using a digital tool to initiate lifestyle modification discussions with survivors suggests that oncologists are aware of the importance of helping survivors with lifestyle modification but integrating lifestyle discussions into daily workflow proves excessively difficult.50 Using mHealth and other integrated digital platforms (e.g., wearables, electronic health records) in a collaborative team approach (nurses, nurse practitioners, health coaches, dieticians, physical therapists, behavioralists, and other healthcare providers) may prove to be a more sustainable, patient-centered, and cost-effective approach. Such a comprehensive approach would allow oncologists to address the oncology needs of patients without compromising workflow while maximizing the scope of practice for nurses and other team members.

Study Quality

In the quantitative studies included in this review, heterogeneity among lifestyle behavior intervention components, delivery mode, intervention type, frequency, intensity, dose, and outcomes hindered synthesis and made generalizations about lifestyle interventions difficult. No study included in this review conducted an a priori power analysis to determine sample size to detect between-group differences, and most were focused only on feasibility. Pilot studies included in this review often included qualitative results, but qualitative methods and results were not fully reported. Failing to follow standardized qualitative reporting guidelines such as the Standards for Reporting Qualitative Research (SRQR) or the Consolidated criteria for Reporting Qualitative Research (COREQ) limits trustworthiness and quality of study findings. Additionally, guidance exists for conducting and reporting feasibility or pilot studies. For example, the 26-item checklist from CONSORT on pilot and feasibility trials20 and the CONSORT-EHEALTH statement offer reporting guidance. Overall, study results must be interpreted with caution.

Lack of Theory

Theories are lacking in the development of mHealth interventions for lifestyle behavior change in cancer survivors. This lack of theoretical underpinning represents an important omission and a gap in the scientific knowledge base associated with mHealth interventions for cancer survivors. Research suggests this lack of theoretical underpinning limits intervention effectiveness51 as greater overall effect size has been observed when research made extensive use of theory.52 Developing and testing behavior change theories adapted or created for use in the context of mHealth and lifestyle behavior change constitutes a necessary step to advance mHealth research and intervention effectiveness among cancer survivors.

However, the lack of theory-based mHealth interventions identified in this review is not surprising, given the existence of similar gaps in the science in other non-cancer contexts.15,53–55 For a decade, and almost from the inception of mHealth interventions, researchers have called for the theoretically-driven design and testing of mHealth technologies to enhance intervention effectiveness.54,56 For example, one recent systematic review and meta-analysis evaluated studies that used digital behavior change interventions.57 Researchers included studies that used mHealth technologies, but also those that involved text messaging, email, mobile applications, patient portals, video-conferencing (i.e., Skype, Zoom), social media, and websites.57 Fifteen experimental and pilot trials that were conducted between 2013 and 2016 were included in the analysis—only 3 of these studies involved mHealth (all of which were included in this review).25,27,30 A secondary aim of the review focused on the theoretical underpinnings of the studies.57 Twelve studies mentioned theory, but overall, the authors rated them of low quality with regard to theory use.57 Moreover, the authors noted a high risk of bias in the included studies which reduced confidence in the overall study findings and the meta-analysis.57 These results align with the findings in this review and support the need for theory-based interventions in future mHealth intervention research.

Limitations and Future Research Implications

Several limitations of this review are noteworthy. First, the review was limited by the lack of published scientific evidence secondary to the newness of these types of mHealth interventions. Secondly, this review did not include the gray literature or published theses and dissertations in this field. Similarly, research conducted by commercial or healthcare organizations was not represented in this review and neither was research presented at research conferences (e.g., American Medical Informatics Association). Finally, publication bias may have limited the review results, as positive findings are reported more often than negative results. Despite these limitations, the extensive search strategy over multiple databases and journals, in multiple scientific disciplines, with input from a healthcare research librarian, allowed for the inclusion of 19 articles for review.

Emerging evidence highlighted in this review suggests mHealth interventions hold the potential to improve cancer survivors’ health by providing targeted, patient-centered, cancer-specific care. Survivors identified many mHealth features and functionalities needed in mHealth interventions to help them improve their lifestyles. This review also highlights significant gaps in our scientific understanding and in the current evidence base.

Conclusion

The principal findings of this integrative review demonstrate a scarcity of evidence and a gap in the scientific understanding of mHealth use by cancer survivors to improve their lifestyle behaviors. The findings of this review align with the work of others who have investigated mHealth interventions in non-cancer settings. The findings also underscore the importance of several mHealth features: goal setting, feedback, tailoring, personalization, and evidence-based content. Social support and professional support have also been identified as crucial elements of mHealth interventions for cancer survivors. However, the evidence has not yet sufficiently matured, in quality or in rigor, to meet the demand for such interventions. Perhaps the most urgent need is for theories to advance scientific discovery, to inform the design and testing of mHealth interventions, and to improve overall intervention effectiveness. Theory building is the first step in addressing the unmet needs of mHealth intervention developers and researchers, and most importantly the needs of cancer survivors.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments:

The authors thank Kerry Dhakal, the Nursing Liaison Librarian at Ohio State University, for her assistance in developing the search strategy and pilot testing various approaches and strategies in a variety of databases.

Footnotes

JMIR Preprint: A non-peer reviewed, draft version of this paper is available online as a preprint at JMIR and may be linked to an accepted peer-review version of this manuscript.

Conflicts of Interest and Source of Funding: This project was supported by grant funding from the Virginia Kelley Fund of the American Nurses Foundation, 2018–2019 Nursing Research Grant Award, the Sigma Theta Tau International/Midwest Nursing Research Society, and National Institutes of Health (NIH NCI 1R01CA226078–01, PIs: Foraker and Weaver). The sponsors were not involved in the preparation, review, or approval of this manuscript. The authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

Contributor Information

Marjorie M. Kelley, The Ohio State University, College of Nursing, Columbus, OH, USA.

Jennifer Kue, The Ohio State University, College of Nursing, Columbus, OH, USA.

Lynne Brophy, The Ohio State University Comprehensive Cancer Center, James Cancer Hospital and Solove Research Institute, Columbus, OH, USA..

Andrea L. Peabody, Founder/CEO, EngageHealth, Inc. Columbus, OH, USA.

Randi E. Foraker, Institute for Informatics, Washington University School of Medicine; Washington University, Department of Internal Medicine, St. Louis, MO, USA.

Po-Yin Yen, Institute for Informatics, Washington University School of Medicine; Department of Medicine, Washington University School of Medicine; Goldfarb School of Nursing, Barnes-Jewish College, BJC HealthCare, St. Louis, MO, USA

Sharon Tucker, The Ohio State University, College of Nursing, Columbus, OH, USA..

References

- 1.WHO. Who cancer fact sheet. World Health Organization. https://www.who.int/en/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/cancer. Accessed: 2019–05-12. (Archived by WebCite® at http://www.webcitation.org/78K0amYOl). Published 2017. Accessed June 17, 2017, 2017.

- 2.Institute NC. Late side effects of cancer treatment. NIH NCI. https://www.cancer.gov/about-cancer/coping/survivorship/late-effects. Published 2017. Accessed June 16, 2017, 2017.

- 3.van Zutphen M, Kampman E, Giovannucci EL, van Duijnhoven FJB. Lifestyle after colorectal cancer diagnosis in relation to survival and recurrence: A review of the literature. Curr Colorectal Cancer Rep. 2017;13(5):370–401. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Foraker RE, Abdel-Rasoul M, Kuller LH, et al. Cardiovascular health and incident cardiovascular disease and cancer: The women’s health initiative. Am J Prev Med. 2016;50(2):236–240. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Blanchard C, Courneya K, Stein K. American cancer society’s scs-ii. Cancer survivors’ adherence to lifestyle behavior recommendations and associations with health-related quality of life: Results from the american cancer society’s scs-ii. J Clin Oncol. 2008;26(13):2198–2204. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lobelo F, Kelli HM, Tejedor SC, et al. The wild wild west: A framework to integrate mhealth software applications and wearables to support physical activity assessment, counseling and interventions for cardiovascular disease risk reduction. Prog Cardiovasc Dis. 2016;58(6):584–594. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bonoto BC, de Araujo VE, Godoi IP, et al. Efficacy of mobile apps to support the care of patients with diabetes mellitus: A systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. JMIR Mhealth Uhealth. 2017;5(3):e4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Cheikh-Moussa K, Mira JJ, Orozco-Beltran D. Improving engagement among patients with chronic cardiometabolic conditions using mhealth: Critical review of reviews. JMIR Mhealth Uhealth. 2020;8(4):e15446. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Whittemore R, Knafl K. The integrative review: Updated methodology. J Adv Nurs. 2005;52(5):546–553. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Moher D, Liberati A, Tetzlaff J, Altman DG. Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: The prisma statement. J Clin Epidemiol. 2009;62(10):1006–1012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Counsell C. Formulating questions and locating primary studies for inclusion in systematic reviews. Ann Intern Med. 1997;127(5):380–387. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Haynes B. Forming research questions. In: Haynes RB, Sackett DL, Guyatt GH, Tugwell P, eds. Clinical epidemiology: How to do clinical practice research. 3rd ed. Philadelphia: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Istepanian RS, Woodward B. M-health: Fundamentals and applications. John Wiley & Sons; 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 14.WHO. Mhealth: New horizons for health through mobile technologies. World Health Organization. Global observatory for eHealth series; - Volume 3 Web site. https://www.who.int/goe/publications/goe_mhealth_web.pdf. 2011. Accessed June 12, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Riley WT, Rivera DE, Atienza AA, Nilsen W, Allison SM, Mermelstein R. Health behavior models in the age of mobile interventions: Are our theories up to the task? Transl Behav Med. 2011;1(1):53–71. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Momin B, Neri A, Zhang L, et al. Mixed-methods for comparing tobacco cessation interventions. J Smok Cessat. 2017;12(1):15–21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Higgins J, Altman D, Sterne J. Chapter 8: Assessing risk of bias in included studies. In: Higgins J, Churchill R, Chandler J, Cumpston M, eds. Cochrane handbook for systematic reviews of interventions version 5.2.0. Vol 5.2.0. John Wiley & Sons, Ltd; 2017. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Jackson N, Waters E. Criteria for the systematic review of health promotion and public health interventions. Health Promot Int. 2005;20(4):367–374. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Thomas BH, Ciliska D, Dobbins M, Micucci S. A process for systematically reviewing the literature: Providing the research evidence for public health nursing interventions. Worldviews Evid Based Nurs. 2004;1(3):176–184. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Eldridge SM, Chan CL, Campbell MJ, et al. Consort 2010 statement: Extension to randomised pilot and feasibility trials. Bmj. 2016;355:i5239. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Michie S, Prestwich A. Are interventions theory-based? Development of a theory coding scheme. Health Psychol. 2010;29(1):1–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Robertson MC, Tsai E, Lyons EJ, et al. Mobile health physical activity intervention preferences in cancer survivors: A qualitative study. JMIR Mhealth Uhealth. 2017;5(1):e3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kessel KA, Vogel MM, Kessel C, et al. Mobile health in oncology: A patient survey about app-assisted cancer care. JMIR Mhealth Uhealth. 2017;5(6):e81. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Trinh L, Arbour-Nicitopoulos KP, Sabiston CM, et al. A qualitative study exploring the perceptions of sedentary behavior in prostate cancer survivors receiving androgen-deprivation therapy. Oncol Nurs Forum. 2015;42(4):398–406. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hong YA, Goldberg D, Ory MG, et al. Efficacy of a mobile-enabled web app (icanfit) in promoting physical activity among older cancer survivors: A pilot study. JMIR Cancer. 2015;1(1):e7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Martin EC, Basen-Engquist K, Cox MG, et al. Interest in health behavior intervention delivery modalities among cancer survivors: A cross-sectional study. JMIR Cancer. 2016;2(1):e1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.McCarroll ML, Armbruster S, Pohle-Krauza RJ, et al. Feasibility of a lifestyle intervention for overweight/obese endometrial and breast cancer survivors using an interactive mobile application. Gynecol Oncol. 2015;137(3):508–515. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Phillips SM, Conroy DE, Keadle SK, et al. Breast cancer survivors’ preferences for technology-supported exercise interventions. Support Care Cancer. 2017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Pugh G, Hough RE, Gravestock HL, Jackson SE, Fisher A. The health behavior information needs and preferences of teenage and young adult cancer survivors. J Adolesc Young Adult Oncol. 2017;6(2):318–326. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Puszkiewicz P, Roberts AL, Smith L, Wardle J, Fisher A. Assessment of cancer survivors’ experiences of using a publicly available physical activity mobile application. JMIR Cancer. 2016;2(1):e7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Smith SK, Kuhn E, O’Donnell J, et al. Cancer distress coach: Pilot study of a mobile app for managing posttraumatic stress. Psychooncology. 2016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Uhm KE, Yoo JS, Chung SH, et al. Effects of exercise intervention in breast cancer patients: Is mobile health (mhealth) with pedometer more effective than conventional program using brochure? Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2017;161(3):443–452. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Ferrante JM, Devine KA, Bator A, et al. Feasibility and potential efficacy of commercial mhealth/ehealth tools for weight loss in african american breast cancer survivors: Pilot randomized controlled trial. Transl Behav Med. 2018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Park SW, Lee I, Kim JI, et al. Factors associated with physical activity of breast cancer patients participating in exercise intervention. Support Care Cancer. 2019;27(5):1747–1754. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Lloyd GR, Hoffman SA, Welch WA, et al. Breast cancer survivors’ preferences for social support features in technology-supported physical activity interventions: Findings from a mixed methods evaluation. Transl Behav Med. 2018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Mikolasek M, Witt CM, Barth J. Adherence to a mindfulness and relaxation self-care app for cancer patients: Mixed-methods feasibility study. JMIR Mhealth Uhealth. 2018;6(12):e11271. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Phillips SM, Courneya KS, Welch WA, et al. Breast cancer survivors’ preferences for mhealth physical activity interventions: Findings from a mixed methods study. J Cancer Surviv. 2019;13(2):292–305. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Roberts AL, Potts HW, Koutoukidis DA, Smith L, Fisher A. Breast, prostate, and colorectal cancer survivors’ experiences of using publicly available physical activity mobile apps: Qualitative study. JMIR Mhealth Uhealth. 2019;7(1):e10918. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Stubbins R, He T, Yu X, et al. A behavior-modification, clinical-grade mobile application to improve breast cancer survivors’ accountability and health outcomes. JCO Clin Cancer Inform. 2018;2:1–11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Lee BJ, Park YH, Lee JY, Kim SJ, Jang Y, Lee JI. Smartphone application versus pedometer to promote physical activity in prostate cancer patients. Telemed J E Health. 2019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Brooke J. Sus: A retrospective. Journal of Usability Studies. 2013;8(2):29–40. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Hekler EB, Rivera DE, Martin CA, et al. Tutorial for using control systems engineering to optimize adaptive mobile health interventions. J Med Internet Res. 2018;20(6):e214. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Denlinger CS, Ligibel JA, Are M, et al. Survivorship: Nutrition and weight management, version 2.2014. Clinical practice guidelines in oncology. J Natl Compr Canc Netw. 2014;12(10):1396–1406. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Demark-Wahnefried W, Clipp EC, Lipkus IM, Lobach D, Snyder DC, Sloane R. Main outcomes of the fresh start trial: A sequentially tailored, diet and exercise mailed print intervention among breast and prostate cancer survivors. J Clin Oncol. 2007;25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Vance V, Mourtzakis M, McCargar L, Hanning R. Weight gain in breast cancer survivors: Prevalence, pattern and health consequences. Obesity reviews. 2011;12(4):282–294. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Helyer LK, Varnic M, Le LW, Leong W, McCready D. Obesity is a risk factor for developing postoperative lymphedema in breast cancer patients. The breast journal. 2010;16(1):48–54. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Norman J, Bild D, Lewis C, Liu K, West DS. The impact of weight change on cardiovascular disease risk factors in young black and white adults: The cardia study. International journal of obesity. 2003;27(3):369. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Weaver K, Foraker R, Alfano C, et al. Cardiovascular risk factors among long-term survivors of breast, prostate, colorectal, and gynecologic cancers: A gap in survivorship care? Journal of Cancer Survivorship. 2013;7(2):253–261. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Truesdale KP, Stevens J, Lewis CE, Schreiner PJ, Loria CM, Cai J. Changes in risk factors for cardiovascular disease by baseline weight status in young adults who maintain or gain weight over 15 years: The cardia study. International journal of obesity (2005). 2006;30(9):1397. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Kelley M, Foraker R, Lin E- JD, Kulkarni M, Lustberg M, Weaver KE. Oncologists’ perceptions of a digital tool to improve cancer survivors’ cardiovascular health. ACI Open. 2019;3(02):e78–e87. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Burke LE, Ma J, Azar KM, et al. Current science on consumer use of mobile health for cardiovascular disease prevention. Circulation. 2015:CIR. 0000000000000232. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Bluethmann SM, Bartholomew LK, Murphy CC, Vernon SW. Use of theory in behavior change interventions. Health Educ Behav. 2017;44(2):245–253. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Bender JL, Yue RY, To MJ, Deacken L, Jadad AR. A lot of action, but not in the right direction: Systematic review and content analysis of smartphone applications for the prevention, detection, and management of cancer. J Med Internet Res. 2013;15(12):e287. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Vollmer Dahlke D, Fair K, Hong YA, Beaudoin CE, Pulczinski J, Ory MG. Apps seeking theories: Results of a study on the use of health behavior change theories in cancer survivorship mobile apps. JMIR Mhealth Uhealth. 2015;3(1):e31. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Lunde P, Nilsson BB, Bergland A, Kvaerner KJ, Bye A. The effectiveness of smartphone apps for lifestyle improvement in noncommunicable diseases: Systematic review and meta-analyses. J Med Internet Res. 2018;20(5):e162. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Hekler EB, Michie S, Pavel M, et al. Advancing models and theories for digital behavior change interventions. Am J Prev Med. 2016;51(5):825–832. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Roberts AL, Fisher A, Smith L, Heinrich M, Potts HWW. Digital health behaviour change interventions targeting physical activity and diet in cancer survivors: A systematic review and meta-analysis. J Cancer Surviv. 2017;11(6):704–719. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.