Abstract

As blood clots age, many thrombolytic techniques become less effective. In order to fully evaluate these techniques for potential clinical use, a large animal, aged-clot model is needed. Previous minimally invasive attempts to allow clots to age in an in-vivo large animal model were unsuccessful due to the clot clearance associated with relatively high level of cardiac health of readily available research pigs. Prior models have thus subsequently utilized invasive surgical techniques with the associated morbidity, animal stress, and cost. We propose a method for forming sub-acute venous blood clots in an in-vivo porcine model. The age of the clots can be controlled and varied. By using an intravenous scaffold to anchor the clot to the vessel wall during the aging process, we can show that sub-acute clots can consistently be formed with a minimally invasive, percutaneous approach. The clot formed in this study remained intact for at least one week in all subjects. Therefore, we established a new minimally invasive, large animal aged-clot model for evaluation of thrombolytic techniques.

Keywords: Thrombosis, deep vein thrombosis, DVT, clot retraction, sub-acute clot, non-invasive, thrombolysis, in-vivo

Introduction

Venous thromboembolism (VTE), including deep vein thrombosis (DVT) and pulmonary embolism (PE), is a serious public health concern. It is estimated that VTE affects between 1 and 2 people per 1000 of the population in the United States (Beckman et al. 2010), with pulmonary embolism alone accounting for the third most cardiovascular disease related deaths (Goldhaber and Henri 2012). To advance treatments for DVT, it is necessary to develop models to accurately imitate the clinical condition. Thus far, models have been developed and used by multiple groups to emulate freshly formed blood clots in vitro (Maxwell et al. 2009; Zhang et al. 2015), ex vivo (Sutton et al. 2013), and in vivo (Maxwell et al. 2011). However, blood clots naturally mature, which can result in a sub-acute or aged clot that may be more resistant to various thrombolytic techniques compared to freshly formed clots (Sutton et al. 2013). As the clot ages, processes such as retraction can occur, where serum is expelled, and the cells contained within the clot become more densely packed and less porous (Blinc et al. 1992) for thrombolytic drugs to penetrate into the clots. Through conversations with clinical experts in the field, we believe it would not be unusual for a clot to be approximately 5-7 days old when DVT patients seek treatment.

The current standard of care for DVT treatment is anticoagulation. Generally, this treatment consists of intravenous heparin for 5-10 days, followed by oral anticoagulants for a minimum of 3 months (Lensing et al. 1999; Rodriguez et al. 2012). This treatment is non-ideal for multiple reasons, including an increased risk of bleeding (Linkins et al. 2003), and common occurrences of post thrombotic syndrome in these patients (Comerota and Paolini 2007). Alternative treatments include catheter-based thrombolysis and vena cava filters (Wells et al. 2014) as well as mechanical thrombectomy (Frisoli and Sze 2003).

The use of ultrasound as a method to promote thrombolysis is an area of active research (Truebestein et al. 1976; Bader et al. 2016). Previously, ultrasound has been used both as a standalone means to promote thrombolysis and more commonly in combination with a thrombolytic agent in order to improve its efficacy (Bader et al. 2016; Hitchcock et al. 2011; Stone et al. 2007; Tsivgoulis et al. 2010). Clinical studies have also shown ultrasound enhanced thrombolytic techniques to be effective for the treatment of ischemic stroke (Alexandrov et al. 2004; Mahon et al.; Molina et al. 2009; Tsivgoulis et al. 2010). Shear forces and cavitation bubbles generated by high intensity focused ultrasound can increase the permeation of the thrombolytic agents into the clot, increasing efficacy over treatments without ultrasound enhancement (Frenkel et al. 2006; Stone et al. 2007). Many previous studies involving aged, retracted clots have shown sonothrombolytic techniques to be less effective and efficient than similar studies with fresh clots, which is likely due to the decreased permeability and vulnerability of retracted clots to the sonothrombolytic treatment (Mercado-Shekhar et al. 2018; Sutton et al. 2013; Zhang et al. 2016). Histotripsy has been shown to be an effective sonothrombolytic technique, for fresh and retracted clots, without requiring the use of thrombolytic agents (Khokhlova et al. 2016; Shi et al. 2018; Zhang et al. 2016; Zhang et al. 2017).

In vitro aged, retracted clot models have been developed (Hitchcock et al. 2011; Sutton et al. 2013) and used for sonothrombolysis (Bader et al. 2016; Goel et al. 2021) or histotripsy (Bollen et al. 2020; Hendley et al. 2021; Shi et al. 2018; Zhang et al. 2016) studies. Additionally, a method for implanting retracted human clots into a porcine ascending pharyngeal artery has been developed (Kleven et al. 2021). For treatment methods to be evaluated for their efficacy on aged clots in vivo for clinical translation, a large animal model must be developed that allows for clots to be aged. In vivo animal models for aged or sub-acute clots have been limited in development. It is worth mentioning that arterial and venous thrombi differ, but models for each were examined. Venous thrombi typically are seen as red blood cells enmeshed in fibrin, while arterial thrombi show high concentrations of platelets, and lower concentration of red blood cells (Chernysh et al. 2020). While the clot types differ, methods of formation could have similarities, and therefore, larger animal arterial clot models were also examined. In vivo large animal models for aged clots generally have involved surgical ligation of the targeted blood vessel, or the use of metallic coils to promote thrombosis (Michel and Hakim 1985; Fadel et al. 1999). These models are non-ideal for testing the non-invasive ultrasound techniques such as transcutaneous sonothrombolysis or histotripsy, due to the additional disruption (which is not associated with treatment) near the treatment area. Additionally, the use of metal coils could interfere with ultrasound propagation. There is a need for an in vivo large-animal model in order to most accurately approximate a clinical scenario involving a mature, aged DVT that is minimally invasive and does not interfere with ultrasound delivery. This paper describes a robust porcine aged DVT model that will provide an in vivo large animal sub-acute clot model suitable for testing the non-invasive or minimally invasive ultrasound techniques for the treatment of thrombosis.

Materials and Methods

Theory

Venous clot formation is largely dependent on the relationship between three factors: vessel wall injury, a decrease in blood flow rate, and an increase in blood coagulability (Hirsh et al. 1986; Lensing et al. 1999). The method developed in this study takes advantage of all three of these factors in an attempt to create an ideal environment for clot formation. First, via a percutaneous approach, two balloon catheters are inserted into the femoral vein. The process of catheter placement induces vessel wall injury, fulfilling the first factor for thrombus formation. The balloons are inflated, causing complete blood flow stasis in a region of the femoral vein. Additionally, thrombin is injected into the region of vein between the balloons, causing hypercoagulability. In order for the clot to be allowed to age, the animal must be recovered, and the clot must stay in place for up to a week. Due to the young age and good cardiac health of readily available research pigs, the clot is at risk of being cleared before it can fully age if the catheters are removed and the animal is recovered. Because of this, one of the catheters is left in place, within the vein, in order to act as an intravenous scaffold to anchor the clot to the vessel wall during the aging process.

Clot Formation

The protocols described in this article have been approved by the University Committee on Use and Care of Animals at the University of Michigan. Mixed breed pigs weighing between 30 and 40 kilograms were used for this study. The animals used were initially sedated with Telazol (Zoetis, Parsippany-Troy Hills, NJ, USA) combined with Xylazine (generic, purchased from MWI Animal Health, Boise, ID, USA) given intramuscularly. An intravenous catheter (Angiocath 22Gx1”, Becton Dickinson, Franklin Lakes, NJ, USA) was then placed in the auricular ear vein for maintenance fluid infusion during the procedure. Each pig was then intubated and maintained on isoflurane gas throughout the procedure. Sterile lubricant (Puralube Vet Ointment, Dechra, Northwich, United Kingdom) was applied to both eyes, and the pig was placed in dorsal recumbency on a heating pad (HotDog Warming System, HotDog, Eden Prarie, MN, USA). Heart rate, oxygen saturation, respiration rate, and temperature were continuously monitored during the procedure.

The skin over one of the femoral veins was shaved in order to remove hair from the area. The skin was then prepared by alternating betadine scrub with sterile saline for at least three rounds each, and then draped. Two 8-Fr wedge balloon catheters (Arrow Al-07128, Teleflex, Morrisville, NC, USA) were placed percutaneously, via a modified Seldinger technique, in the femoral vein with approximately 3-5 cm between them. First, a 21-gauge introducer needle (G43870, Cook Medical, Bloomington, IN, USA) was used to gain access to the femoral vein. A 0.018 inch wire guide (G43870, Cook Medical, Bloomington, IN, USA) was placed in the vein, and the introducer needle was removed. The wire guide was used to place a sterilized, re-used dilator from a Terumo 10 cm 8 Fr sheath (RSS801, Terumo Medical Corporation, Elkton, MD, USA). The 0.018 inch wire guide was exchanged with a 0.038 inch guide wire (GR3806, Terumo Interventional Systems, Somerset, NJ, USA) through the dilator. Finally, the wedge balloon catheter (Arrow Al-07128, Teleflex, Morrisville, NC, USA) was placed over the 0.038 inch guide wire. This process was completed with both balloon catheters. Additionally, the proximal (in relation to the heart) catheter was tunneled under the skin for approximately 5 cm to allow it to be stably buried before recovery of the animal (can be seen in Figures 1 and 2). Ultrasound (Lumify L12-4, Philips, Amsterdam, Netherlands) guidance was used to confirm the placement of the catheters. 500 units of thrombin (RECOTHROM, ZymoGenetics, Seattle, WA, USA) was then injected through the distal catheter, and the clot was allowed to incubate for 2-3 hours with the balloons inflated. Heparin (generic, purchased from University of Michigan Pharmacy, Ann Arbor, MI, USA) at 200 units/kg was also given in a single bolus at the time of thrombin injection to anticoagulate the blood outside of the ballooned off area. Activated clotting time was measured and confirmed to be greater than 200 seconds after heparin administration.

Figure 1: Diagram:

Diagram showing catheter placement and burying technique. Arrows indicate direction of blood flow in the femoral vein. After the incubation period, the distal catheter is removed, while the proximal catheter is trimmed and buried under the skin.

Figure 2: Catheter Insertion Points:

Image of the catheter insertion points during the clot incubation period. The green arrow represents the venipuncture site, the blue arrow represents the skin exit site after tunneling of the catheter. The red arrow indicates the distal catheter insertion point.

After the incubation period, the balloons were deflated, and the presence of a clot was confirmed via ultrasound imaging. The distal catheter was then removed, and the proximal catheter was allowed to remain in the vessel to serve as an anchor for the clot. To help ensure the remaining catheter did not become dislodged from the vessel, during recovery it was advanced a few centimeters after the balloon was deflated. Because the proximal catheter was running through part of the clot, it served to provide a mechanical block to keep the clot from breaking free of the vessel wall. Additionally, the clot may have been adhered to the catheter itself (because it was formed around the catheter), providing additional resistance to clot movement. The end of the catheter was cut and stapled to prevent bleeding and was buried under the skin. Catheter insertion points were then closed with skin glue (Vetbond, 3M, Maplewood, MN, USA), and the animal was recovered. Anticoagulation was not administered in the days following clot formation. Six of the seven pigs had the proximal catheter removed after one week, and the animal was euthanized. The final pig was put under anesthesia three days after clot formation, had the catheter removed, and was allowed to recover. After an additional four days (7 days total aging), the pig was again anesthetized, the clot was observed via ultrasound imaging, and the animal was euthanized. This additional step was to test the feasibility of removing the catheter a day or more prior to treatment. This may be of importance for testing some thrombolytic techniques where the presence of the catheter may affect results of the treatment.

After acquiring ultrasound images on day 7, image segmentation was performed using the MATLAB image segmentation package (MathWorks, Inc., Natick MA, USA). One image for each clot was segmented into venous lumen, thrombus, and surrounding tissue. This segmentation was then used to calculate percent occlusion of the venous lumen in order to provide an estimate of the size of the remaining clot.

Histological Analysis

After euthanization of the animals, a small block of tissue containing the clot was removed and fixed in 10% phosphate buffered formalin before embedded in paraffin. Tissue blocks were then sectioned and stained with hematoxylin and eosin (H&E) and Martius Scarlet Blue (MSB) and examined under a microscope (BX43, Olympus, Shinjuku, Tokyo, Japan) by a pathologist (JS). Microscopic images were taken using an Olympus DP73 (Shinjuku, Tokyo, Japan) digital camera. Clots were categorized as Phase I-III according to characteristics described in Fineschi et al. (2009). Phase I is characterized as a platelet plug and fibrin deposition with layered growth, and is typical of clots aged 1-7 days. Phase II is characterized by endothelial budding, penetration of fibroblasts, endothelization of free surfaces of thrombi, the presence of nuclear debris from white blood cells, and ribbons of fibrin trapping white blood cells. Phase II is typical of clots aged into the 2nd-8th weeks. Phase III is characterized by completely hyalinized thrombus. Additionally, the thrombus will have central sinuous cavities, and recanalization with flowing blood. Phase III is typical of clots with an age greater than 8 weeks (Fineschi et al. 2009). In this study, Phase II accounted for 50% of the examined clots, while Phase I accounted for 34.29%, and Phase III accounted for 15.71% (Fineschi et al. 2009). Because it was the most common phase, we desired to have our model consistently form Phase II clots. MSB stain was used to highlight fibrin and collagen in the clots.

Clots were also characterized by measuring the percent occlusion of the blood vessel, as seen on each histology slide. The measured percent occlusion should not be seen as a fully accurate representation of the three-dimensional volume of the clot, as fissures can occur during tissue fixation and slide preparation, and the clot may not be uniform over the entire length. Additionally, processing or sampling error could affect results. With these limitations in mind, we believe histological analysis is a reasonable method for providing an estimate of percent occlusion.

Results

In vivo Ultrasound Imaging

One week after clot formation, prior to euthanization and harvest, thrombi were examined via ultrasound imaging. Ultrasound images confirmed the presence of a thrombus in all seven pigs at the site of formation. Example B-mode ultrasound images can be seen in Figures 3 and 4. Both figures 3 and 4 were obtained from different positions of the same clot in the same pig which had the catheter removed after 3 days of aging. Images were acquired after 7 days of total aging, 4 days after the catheter had been removed. B-mode images of the thrombus that had the catheter removed after three days revealed a void within the clot, presumably from where the catheter had been before removal (Figure 4). However, the clot was otherwise intact and was fully occlusive at other points along the length of the clot (Figure 3). B-mode images of the thrombus that had the catheter removed after seven days showed the hyperintense clot occupying the entire vessel lumen (similar to Figure 3). Removal of the catheter, and subsequent recovery of the animal showed the feasibility of catheter removal four days prior to when a potential treatment would occur. B-mode and Doppler ultrasound images showed partial or full occlusion of the femoral vein for all seven pigs (Figures 3-5). Percent occlusion is summarized in Table 1. Due to the imprecise nature of this method (via ultrasound) for estimating percent occlusion (due to variation along the length of the clot, as can be seen in Figure 6), results are rounded to the nearest 25% (0%, 25%, 50%, 75%, or 100%).

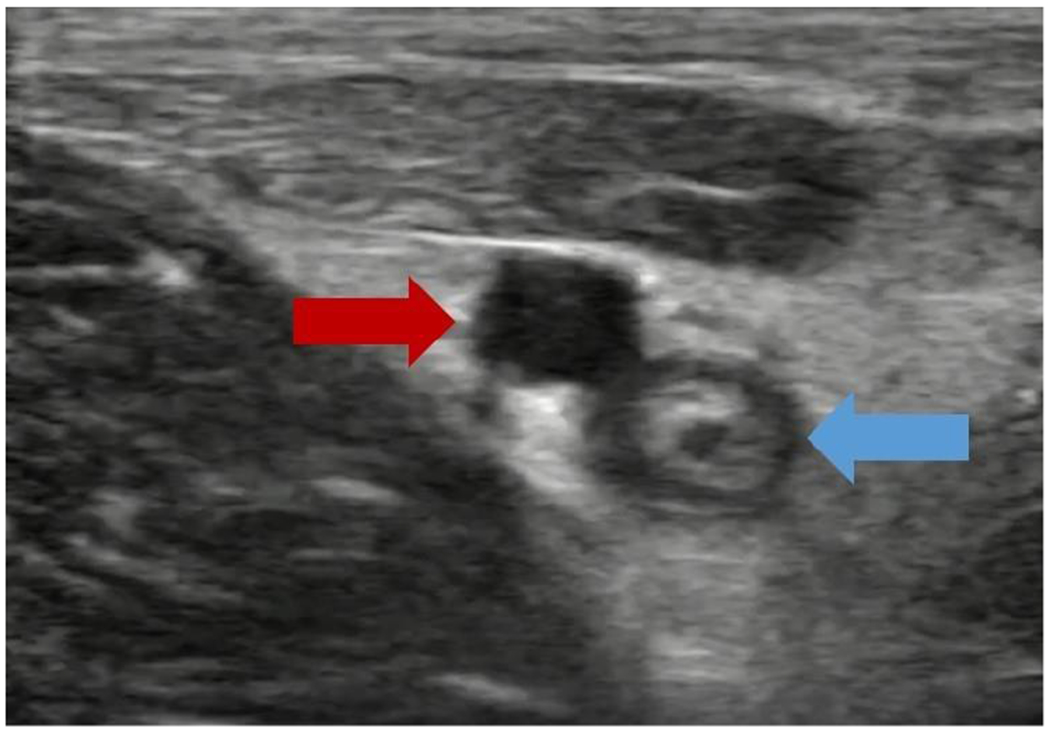

Figure 3: High Occlusion Ultrasound:

An ultrasound image of a one-week-old clot (4 days after catheter removal), exhibiting a high level of occlusion. The red arrow indicates the femoral artery, while the blue arrow indicates the clotted femoral vein.

Figure 4: Catheter Removal Ultrasound:

An image of a one-week-old clot, showing a void in the clot from catheter removal 4 days prior. This image is of the same clot shown in Figure 3, but at a different position, resulting in the void seen here. The red arrow indicates the femoral artery, while the blue arrow indicates the clotted femoral vein.

Figure 5: Doppler Ultrasound After Catheter Removal:

A Doppler image of a one-week-old clot, after catheter removal. The color flow Doppler observed is associated with the formed clot.

Table 1:

Summary of percent vein occlusion, as well as presence of calcification of thrombus and granulation tissue/injury adjacent to vein.

| Subject No. | US Based % Occlusion | Histology Based Average % Occlusion | Calcification of thrombus present | Granulation tissue/injury adjacent to vein |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| P1 | 50% | 65.0% | Yes | Yes |

| P2 | 75% | 56.7% | Yes | Yes |

| P3 | 25% | 66.7% | Yes | Yes, and hemorrhage |

| P4 | 50% | 10.0% | Yes | Yes |

| P5 | 50% | 70.0% | Yes | Yes |

| P6 | 50% | 91.7% | Yes | Yes |

| P7* | 50% | 91.7% | Yes | Yes |

Indicates catheter was removed three days after clot formation, animal was recovered, and the clot was allowed to age further.

Figure 6: Longitudinal Ultrasound of Clot:

A B-mode image of a one-week-old clot, displaying how percent occlusion can vary in different cross-sectional planes of the clot. Blue indicates the location of the vessel walls, with red indicating the approximate boundary of the clot. As can be seen, the clot varies from being non-occlusive to nearly fully occlusive.

Histological Analysis of Thrombi

All femoral veins contained thrombi with various percentages of vein occlusion range from 10% to 95% (Table 1, Figure 7A-B). 2-3 histology slides were examined for each pig. In all seven pigs, calcification was observed in the thrombus (Table 1, Figure 7A-B). The femoral arteries were all unremarkable, without any thrombus or injuries (Figure 7C). However, all animals had injuries and reactive changes to the adjacent soft tissue, mostly characterized by granulation tissues and hemorrhages (Figure 7D, Table 1). On higher magnifications, all thrombi contained characteristic features for phase II (2nd-8th week old) aged thrombi according to the histological age determination method described by Fineschi et al. (2009). These thrombi contained features of organization in aged thrombi that were not observed in the fresh clots generated previously in a porcine DVT model (Maxwell et al. 2011). The features of aged thrombi present in the current model included endothelial budding and penetration of fibroblasts into thrombi (Figure 8A), endothelialization of the free surface of thrombi (Figure 8B), nuclear debris of white blood cells (Figure 8C), and ribbons of fibrin trapping white blood cells (Figure 8D). In addition, MSB stain highlighted fibrin (orange to red) and strings of collagen (blue) intermixed with fibroblasts in the aged clots (Figure 9). In comparison with an acute clot from a previous experiment (formed using a similar procedure, but harvested just after formation, procedure described in Maxwell et al. 2011), none of the features of the aged thrombi was present in a fresh clot shown in Figure 10. There was only fresh clot with red blood cells and fibrin and minimal focal lifting of the intima with a small amount of hemorrhage underneath the intima (Figure 10).

Figure 7: Aged Clot and Adjacent Histology:

Histology of aged-clot and adjacent structures. A, B. Representative pictures of thrombi with calcifications (arrows) in femoral vein. C. Unremarkable adjacent femoral artery (arrow). D. Granulation tissues (black arrow) adjacent to the vein with thrombus (red arrow). Original magnification: 20x.

Figure 8: Aged Clot Histology:

Histology of aged clot. A. Endothelial budding and penetration of fibroblasts into thrombus (arrows). B. Endothelization of the free surface of thrombus (arrow). C. Nuclear debris of white blood cells in fibrin (arrow). D. Ribbons of fibrin trapping white blood cells. Original magnification 40x (A), 200x (B, D), 400x (C).

Figure 9: Aged Clot MSB Histology:

Martius Scarlet Blue (MSB) staining of aged clot. A. Representative image of MSB staining of an aged clot showing fibrin (orange to red, black arrow) and vessel wall with collagen (blue, red arrow). B. Representative image of MSB staining of an aged clot showing strings of collagen (blue, black arrows) intermixed with fibroblasts adjacent to fibrin (red, red arrow). Original magnification: 40x (A), 100x (B)

Figure 10: Fresh Clot Histology:

Comparative histology of a fresh clot sample, formed using a similar protocol in a porcine vein. A. Low power view of a fresh clot in the femoral vein. B. Higher magnification of the area highlighted by the rectangle in A showing fresh clot and focal minimal lifting of the intima with small hemorrhage.

Discussion

The method of clot formation described in this paper has significant advantages over other methods used previously to evaluate ultrasound-based thrombolysis techniques. Most importantly, this model enables researchers to form sub-acute clots in vivo in a large animal model. A large animal model may be essential to some researchers in order to evaluate certain techniques or devices that cannot be fully evaluated in a small animal model. One example could be evaluation of catheter-based devices involving a device too large to be used in a small animal model (Goel et al. 2020; Goel and Jiang 2020; Kim et al. 2017). Similarly, transcutaneous histotripsy thrombolysis techniques may be difficult to assess in a small animal model due to the size of the histotripsy bubble cloud potentially being larger than the size of the blood vessel containing the clot in a small animal model. This could result in significant damage to the tissue surrounding the vessel. Furthermore, the duration of the aging process is variable, and individual investigators will be able to change the duration to determine what is most appropriate for their study. Depending on the length of time an investigator decides to allow the clot to age, this model could be used to form retracted blood clots. Additionally, the catheter can be removed during the aging process, allowing the clot to remain intact without an intravenous scaffold. The in vivo aging process allows for treatment of clots in a more realistic and complete environment than an in vitro or ex vivo method would provide. In addition to assessing the ability of a method to actually recanalize an occluded vessel, in vivo models also help assess other risks, such as the risk of pulmonary embolism, vessel injuries, and post-treatment re-thrombosis associated with a particular thrombolysis technique. The authors see no reason an animal could not be recovered following treatment, allowing for long term observation of the animal’s response to a treatment. This provides a valuable metric in assessing the safety and efficacy of new ultrasound-based thrombolysis techniques, such as histotripsy or ultrasound enhanced rt-PA treatments, in comparison to the more traditionally used anticoagulant treatments.

This method is also minimally invasive, utilizing catheters to form the clot rather than a more invasive surgical technique. This results in an easier recovery for the animal, with limited disturbance to the tissue surrounding the clotted portion of the blood vessel. Additionally, it was shown that catheters could be removed prior to the aging process being completed, allowing researchers to assess potential treatments without the presence of catheters. This could be of importance for some techniques, for which the catheters could have an effect on treatment outcome, such as catheter-based sonothrombolysis techniques.

One concern when developing a thrombosis model for pre-clinical evaluation of thrombolytic techniques is the impact of species on the efficacy of thrombolytics. Specifically, concern has been raised by multiple researchers regarding the use of a porcine model for thrombolytic techniques when using agents such as rt-PA (Flight et al. 2006; Huang et al. 2017). However, due to the similar coagulation cascade and cardiovascular system compared to humans (Siller-Matula et al. 2008), a porcine model is seen as a standard large animal acute clot model for sonothrombolytic techniques, such as histotripsy (Huang et al. 2017; Maxwell et al. 2011; Zhang et al. 2017). Additionally, it was desired to utilize a species with a similar size to humans, as this can affect ultrasound targeting of the vessel, and the ability to use ultrasound devices designed with human anatomy in mind, such as preclinical ultrasound catheter devices (Goel et al. 2020; Goel and Jiang 2020; Kim et al. 2017). For these reasons, a porcine model was chosen for this application, as it was specifically being developed for use with sonothrombolysis. It is possible another species may be a better choice for some studies, where other factors may be of higher importance.

Compared to the fresh clot model we previously described (Maxwell et al. 2011), our current model generated aged thrombi with features of organization and consistent with phase II (2nd-8th week old) aged thrombi, the phase most commonly associated with DVTs analyzed post mortem in the previous study by Fineschi (2009). These features include endothelial budding and penetration of fibroblasts into thrombi, endothelialization of the free surface of thrombi, and ribbons of fibrin trapping nuclear debris of white blood. None of these features are present in fresh clots. Since the age of the clots may impact thrombolytic treatment efficacy, this technique provided a novel minimally invasive method to generate aged thrombi as a useful model for evaluating thrombolytic treatment modalities.

Because the clot is left to mature for a week or longer, additional clotting can occur outside of the intended clot region between the two balloon catheters. This is potentially a problem for two reasons. First, the clot formed may be heterogeneous with different maturity throughout the clot. This, however, may closely mimic the clinical scenario as clot maturation and enlargement can occur in humans as well. This could complicate evaluations of therapies aimed at retracted clots and confirmation will be necessary to determine if the clot treated was truly retracted or a portion of fresh clot. As discussed above, this can be accomplished histologically. In addition to this, there is a lack of clot length control associated with this method. This can cause challenges during certain types of treatment, making recanalizing of the vessel more difficult at times. A decrease in overall clot burden can still be assessed if the length of the clot is prohibitive to recanalization. If additional clotting is seen as detrimental to the usefulness of the model, it may be possible to prevent additional clotting with an anticoagulation dosing scheme in the days following thrombus formation. This, however, could result in less effective retention of the desired, sub-acute clot.

In addition to the lack of clot length control, clots are not necessarily fully occlusive over the entire range of the clot. An example of this can be seen in figure 6. At different cross-sectional positions along the length of the clot, the percent occlusion can vary substantially. While a longitudinal view cannot be used to quantify percent occlusion, figure 6 provides a qualitative view of how occlusion can vary between different planes of the same clot. This variability can also be seen through the difference in percent occlusion results obtained by ultrasound and histological analysis shown in Table 1. Because the percent occlusion results for the two methods were not obtained through the same lateral plane of the vessel, a substantial difference can be seen between the results obtained through the two different methods. In addition to the variability in occlusion over the length of the clot, occlusion is likely secondary to the initial clot formation incubation time. As our goal of developing a sub-acute DVT model was not dependent on consistent, full occlusion, we deemed our results to be successful, however, the model may be conducive for customization (longer incubation time, use of anticoagulants to suppress additional clotting during the aging process, etc.) if 100% occlusion over the length of the clot is desired. Additionally, catheter placement may play a role in the variation of occlusion. Finally, catheter removal can affect occlusion percentage. This can be seen in Figure 4. Due to the (proximal) catheter running through part of the clot, a tunnel can be left through part of the clot if the catheter is removed prior to treatment. It is also worth noting that even if a clot appears to be fully occlusive of the vessel it is formed in, it is possible that vessel collaterals can allow blood flow past the thrombus location. This means that achieving effective 100% occlusion will be difficult to confirm, even if a clot appears to occupy the entire vessel.

Conclusion

In conclusion, the proposed method has been shown to be appropriate for formation of aged thrombi in porcine subjects. This may be applicable to analyze a range of thrombolytic techniques and offers a significant degree of flexibility in how long the clot is allowed to age. Additionally, we can show that it is possible to remove the catheter from the vessel allowing the clot to age further. Thus, this model provides flexibility to investigators studying various components of thrombosis and thrombolytic therapies, particularly ultrasound-based thrombolysis techniques.

Acknowledgements

This work was funded by NIH grant R01HL141967.

JS is supported in part by the National Cancer Institute of the National Institutes of Health under award number K08CA234222.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Conflict of Interest Statement

Paul Dayton is a co-founder of Triangle Biotechnology Inc. and SonoVol, Inc.,. Xiaoning Jiang and Paul Dayton have a financial interest in Sonovascular, Inc. Zhen Xu has financial interest in HistoSonics, Inc.

References

- Alexandrov AV, Molina CA, Grotta JC, Garami Z, Ford SR, Alvarez-Sabin J, Montaner J, Saqqur M, Demchuk AM, Moyé LA, Hill MD, Wojner AW. Ultrasound-Enhanced Systemic Thrombolysis for Acute Ischemic Stroke. N Engl J Med Massachusetts Medical Society, 2004;351:2170–2178. Available from: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/15548777/ [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bader KB, Haworth KJ, Shekhar H, Maxwell AD, Peng T, McPherson DD, Holland CK. Efficacy of histotripsy combined with rt-PA in vitro. Phys Med Biol IOP Publishing, 2016;61:5253–5274. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beckman MG, Hooper WC, Critchley SE, Ortel TL. Venous Thromboembolism. A Public Health Concern. Am. J. Prev. Med. Elsevier, 2010. [cited 2021 Apr 21]. pp. S495–S501. Available from: www.ajpm-online.net [DOI] [PubMed]

- Blinc A, Keber D, Lahajnar G, Zupancic I, Zorec-Karlovsek M, Demsar F. Magnetic resonance imaging of retracted and nonretracted blood clots during fibrinolysis in vitro. Haemostasis Haemostasis, 1992. [cited 2021 Apr 21];22:195–201. Available from: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/1468722/ [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bollen V, Hendley SA, Paul JD, Maxwell AD, Haworth KJ, Holland CK, Bader KB. In Vitro Thrombolytic Efficacy of Single- and Five-Cycle Histotripsy Pulses and rt-PA. Ultrasound Med Biol Elsevier USA, 2020;46:336–349. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chernysh IN, Nagaswami C, Kosolapova S, Peshkova AD, Cuker A, Cines DB, Cambor CL, Litvinov RI, Weisel JW. The distinctive structure and composition of arterial and venous thrombi and pulmonary emboli. Sci Reports 2020 101 Nature Publishing Group, 2020;10:1–12. Available from: https://www.nature.com/articles/s41598-020-59526-x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Comerota AJ, Paolini D. Treatment of Acute Iliofemoral Deep Venous Thrombosis: A Strategy of Thrombus Removal. Eur J Vasc Endovasc Surg Eur J Vasc Endovasc Surg, 2007. [cited 2021 Apr 21];33:351–360. Available from: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/17164092/ [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fadel E, Riou JY, Mazmanian M, Brenot P, Dulmet E, Detruit H, Serraf A, Bacha EA, Herve P, Dartevelle P. Pulmonary thromboendarterectomy for chronic thromboembolic obstruction of the pulmonary artery in piglets. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg Mosby Inc, 1999. [cited 2021 Apr 21];117:787–793. Available from: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/10096975/ [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fineschi V, Turillazzi E, Neri M, Pomara C, Riezzo I. Histological age determination of venous thrombosis: A neglected forensic task in fatal pulmonary thrombo-embolism. Forensic Sci Int Forensic Sci Int, 2009. [cited 2021 Apr 21];186:22–28. Available from: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/19203853/ [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Flight SM, Masci PP, Lavin MF, Gaffney PJ. Resistance of porcine blood clots to lysis relates to poor activation of porcine plasminogen by tissue plasminogen activator. Blood Coagul Fibrinolysis 2006;17:417–420. Available from:https://journals.lww.com/bloodcoagulation/Fulltext/2006/07000/Resistance_of_porcine_blood_clots_to_lysis_relates.13.aspx [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frenkel V, Oberoi J, Stone MJ, Park M, Deng C, Wood BJ, Neeman Z, Horne M, Li KCP. Pulsed high-intensity focused ultrasound enhances thrombolysis in an in vitro model. Radiology NIH Public Access, 2006. [cited 2021 Apr 21];239:86–93. Available from: /pmc/articles/PMC2386885/ [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frisoli JK, Sze D. Mechanical thrombectomy for the treatment of lower extremity deep vein thrombosis. Tech. Vasc. Interv. Radiol W.B. Saunders, 2003. pp. 49–52. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goel L, Jiang X. Advances in Sonothrombolysis Techniques Using Piezoelectric Transducers. Sensors 2020, Vol 20, Page 1288 Multidisciplinary Digital Publishing Institute, 2020;20:1288. Available from: https://www.mdpi.com/1424-8220/20/5/1288/htm [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goel L, Wu H, Kim H, Zhang B, Kim J, Dayton PA, Xu Z, Jiang X. Examining the Influence of Low-Dose Tissue Plasminogen Activator on Microbubble-Mediated Forward-Viewing Intravascular Sonothrombolysis. Ultrasound Med Biol Elsevier, 2020;46:1698–1706. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goel L, Wu H, Zhang B, Kim J, Dayton PA, Xu Z, Jiang X. Nanodroplet-mediated catheter-directed sonothrombolysis of retracted blood clots. Microsystems Nanoeng Springer US, 2021;7. Available from: 10.1038/s41378-020-00228-9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goldhaber SZ, Bounameaux H. Pulmonary embolism and deep vein thrombosis. Lancet Elsevier Ltd, 2012;379:1835–1846. Available from: 10.1016/S0140-6736(11)61904-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hendley SA, Paul JD, Maxwell AD, Haworth KJ, Holland CK, Bader KB. Clot degradation under the action of histotripsy bubble activity and a lytic drug. IEEE Trans Ultrason Ferroelectr Freq Control Institute of Electrical and Electronics Engineers Inc., 2021; [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hirsh J, Hull RD, Raskob GE. Epidemiology and pathogenesis of venous thrombosis. J Am Coll Cardiol J Am Coll Cardiol, 1986. [cited 2021 Apr 21];8:104B–113B. Available from: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/3537063/ [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hitchcock KE, Ivancevich NM, Haworth KJ, Caudell Stamper DN, Vela DC, Sutton JT, Pyne-Geithman GJ, Holland CK. Ultrasound-Enhanced rt-PA Thrombolysis in an ex vivo Porcine Carotid Artery Model. Ultrasound Med Biol Elsevier, 2011;37:1240–1251. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang S, Shekhar H, Holland CK. Comparative lytic efficacy of rt-PA and ultrasound in porcine versus human clots. PLoS One Public Library of Science, 2017;12:e0177786. Available from: 10.1371/journal.pone.0177786 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Khokhlova TD, Monsky WL, Haider YA, Maxwell AD, Wang YN, Matula TJ. Histotripsy liquefaction of large hematomas. Ultrasound Med Biol Elsevier USA, 2016;42:1491–1498. Available from: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/27126244/ [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim J, Lindsey BD, Chang WY, Dai X, Stavas JM, Dayton PA, Jiang X. Intravascular forward-looking ultrasound transducers for microbubble-mediated sonothrombolysis. Sci Rep Springer US, 2017;7:1–10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kleven RT, Karani KB, Hilvert N, Ford SM, Mercado-Shekhar KP, Racadio JM, Rao MB, Abruzzo TA, Holland CK. Accelerated sonothrombolysis with Definity in a xenographic porcine cerebral thromboembolism model. Sci Rep 2021;11. Available from: 10.1038/s41598-021-83442-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lensing AWA, Prandoni P, Prins MH, Büller HR. Deep-vein thrombosis. Lancet. Elsevier B.V., 1999. pp. 479–485. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Linkins LA, Choi PT, Douketis JD. Clinical Impact of Bleeding in Patients Taking Oral Anticoagulant Therapy for Venous Thromboembolism: A Meta-Analysis. Ann Intern Med American College of Physicians, 2003. [cited 2021 Apr 21];139:893–901. Available from: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/14644891/ [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mahon BR, Nesbit GM, Barnwell SL, Clark W, Marotta TR, Weill A, Teal PA, Qureshi AI. North American Clinical Experience with the EKOS MicroLysUS Infusion Catheter for the Treatment of Embolic Stroke. Am Soc Neuroradiol. Available from: http://www.ajnr.org/content/24/3/534.short [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Maxwell AD, Cain CA, Duryea AP, Yuan L, Gurm HS, Xu Z. Noninvasive Thrombolysis Using Pulsed Ultrasound Cavitation Therapy - Histotripsy. Ultrasound Med Biol 2009;35:1982–1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maxwell AD, Owens G, Gurm HS, Ives K, Myers DD, Xu Z. Noninvasive treatment of deep venous thrombosis using pulsed ultrasound cavitation therapy (histotripsy) in a porcine model. J Vasc Interv Radiol 2011;22:369–377. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mercado-Shekhar KP, Kleven RT, Aponte Rivera H, Lewis R, Karani KB, Vos HJ, Abruzzo TA, Haworth KJ, Holland CK. Effect of Clot Stiffness on Recombinant Tissue Plasminogen Activator Lytic Susceptibility in Vitro. Ultrasound Med Biol Elsevier USA, 2018;44:2710–2727. Available from: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/30268531/ [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Michel RP, Hakim TS. Increased resistance in postobstructive pulmonary vasculopathy: Structure-function relationships. J Appl Physiol J Appl Physiol (1985), 1985. [cited 2021 Apr 21];71:601–610. Available from: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/1938734/ [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Molina CA, Barreto AD, Tsivgoulis G, Sierzenski P, Malkoff MD, Rubiera M, Gonzales N, Mikulik R, Pate G, Ostrem J, Singleton W, Manvelian G, Unger EC, Grotta JC, Schellinger PD, Alexandrov A V. Transcranial ultrasound in clinical sonothrombolysis (TUCSON) trial. Ann Neurol Ann Neurol, 2009;66:28–38. Available from: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/19670432/ [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rodriguez AL, Wojcik BM, Wrobleski SK, Myers DD, Wakefield TW, Diaz JA. Statins, inflammation and deep vein thrombosis: A systematic review. J. Thromb. Thrombolysis Springer, 2012. [cited 2021 Apr 21]. pp. 371–382. Available from: 10.1007/s11239-012-0687-9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shi A, Lundt J, Deng Z, Macoskey J, Gurm H, Owens G, Zhang X, Hall TL, Xu Z. Integrated Histotripsy and Bubble Coalescence Transducer for Thrombolysis. Ultrasound Med Biol Elsevier USA, 2018;44:2697–2709. Available from: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/30279032/ [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Siller-Matula JM, Plasenzotti R, Spiel A, Quehenberger P, Jilma B. Interspecies differences in coagulation profile. Thromb Haemost 2008;100:397–404. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stone MJ, Frenkel V, Dromi S, Thomas P, Lewis RP, Li KCP, Horne M, Wood BJ. Pulsed-high intensity focused ultrasound enhanced tPA mediated thrombolysis in a novel in vivo clot model, a pilot study. Thromb Res Thromb Res, 2007. [cited 2021 Apr 21];121:193–202. Available from: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/17481699/ [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sutton JT, Ivancevich NM, Perrin SR, Vela DC, Holland CK. Clot Retraction Affects the Extent of Ultrasound-Enhanced Thrombolysis in an Ex Vivo Porcine Thrombosis Model. Ultrasound Med Biol Elsevier USA, 2013;39:813–824. Available from: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/23453629/ [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Truebestein G, Engel C, Etzel F. Thrombolysis by ultrasound. Clin Sci Mol Med 1976;697–698. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tsivgoulis G, Eggers J, Ribo M, Perren F, Saqqur M, Rubiera M, Sergentanis TN, Vadikolias K, Larrue V, Molina CA, Alexandrov A V. Safety and efficacy of ultrasound-enhanced thrombolysis: A comprehensive review and meta-analysis of randomized and nonrandomized studies. Stroke Stroke, 2010;41:280–287. Available from: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/20044531/ [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wells PS, Forgie MA, Rodger MA. Treatment of venous thromboembolism. JAMA - J. Am. Med. Assoc American Medical Association, 2014. [cited 2021 Apr 21]. pp. 717–728. Available from: https://jamanetwork.com/journals/jama/fullarticle/1829996 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang X, Macoskey JJ, Ives K, Owens GE, Gurm HS, Shi J, Pizzuto M, Cain CA, Xu Z. Non-Invasive Thrombolysis Using Microtripsy in a Porcine Deep Vein Thrombosis Model. Ultrasound Med Biol Elsevier USA, 2017;43:1378–1390. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang X, Owens GE, Cain CA, Gurm HS, Macoskey J, Xu Z. Histotripsy Thrombolysis on Retracted Clots. Ultrasound Med Biol Elsevier USA, 2016;42:1903–1918. Available from: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/27166017/ [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang X, Owens GE, Gurm HS, Ding Y, Cain CA, Xu Z. Noninvasive thrombolysis using histotripsy beyond the intrinsic threshold (microtripsy). IEEE Trans Ultrason Ferroelectr Freq Control Institute of Electrical and Electronics Engineers Inc, 2015. [cited 2021 Apr 21];62:1342–1355. Available from: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/26168180/ [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]