Abstract

The severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus (SARS-CoV-2) initiated a global viral pandemic since late 2019. Understanding that Coronavirus disease (COVID-19) disproportionately affects men than women results in great challenges. Although there is a growing body of published study on this topic, effective explanations underlying these sex differences and their effects on the infection outcome still remain uncertain. We applied a holistic bioinformatics method to investigate molecular variations of known SARS-CoV-2 interacting human proteins mainly expressed in gonadal tissues (testis and ovary), allowing for the identification of potential genetic targets for this infection. Functional enrichment and interaction network analyses were also performed to better investigate the biological differences between testicular and ovarian responses in the SARS-CoV-2 infection, paying particular attention to genes linked to immune-related pathways, reactions of host cells after intracellular infection, steroid hormone biosynthesis, receptor signaling, and the complement cascade, in order to evaluate their potential association with sexual difference in the likelihood of infection and severity of symptoms. The analysis revealed that within the testis network TMPRSS2, ADAM10, SERPING1, and CCR5 were present, while within the ovary network we found BST2, GATA1, ENPEP, TLR4, TLR7, IRF1, and IRF2. Our findings could provide potential targets for forthcoming experimental investigation related to SARS-CoV-2 treatment.

Subject terms: Computational biology and bioinformatics, Genetics, Immunology

Introduction

In early December 2019, a new transmissible infection spread widely in China1, which caused a respiratory illness termed severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2)2. On March 11th, 2020 the World Health Organization (WHO) declared SARS-CoV-2 a global viral pandemic disease3. The SARS-CoV-2 infection is very heterogeneous disease that has affected millions of people worldwide. It is characterized by a broad clinical spectrum, encompassing asymptomatic infection, mild upper respiratory tract infection, acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS), septic shock, multi-organ failure, and death4. Since COVID-19 is a massive population pathology, the SARS-CoV-2 can be detected in the wastewater5. Therefore, significant number of patients could have digestive tract infection leading to the urinary and genital infections6. Nevertheless, the viremia at the urine infection is detectable in about 10% of the patients. Hence, the majority of the cases the infection is confined to the respiratory tract SARS-CoV-2 viral load results in a worsen prognosis7. COVID-19 virus attacks typically the mucosal membranes of the host through the N-terminal peptidase domain of angiotensin-converting enzyme 2 (ACE2) at the surface of the cell membrane using the S domain8. ACE2 protein is expressed in systemic tissues including lung, heart, stomach, kidney, ileum, colon, thyroid, genitourinary and adipose tissue9. Consequently, any cells expressing ACE2 is likely to SARS-CoV-2 infection. Since ACE2 is also expressed in spermatogonia, Leydig and Sertoli cells, testicular tissue is a target tissue of SARS-CoV-210. After the binding of SARS-CoV-2 to ACE2 and virion membrane fusion, downregulation of ACE2 expression generates an excessive synthesis of angiotensin by the related enzyme11. An augmented replication of coronaviruses downregulates the expression of ACE212. AT2 cells are the principal target cells of SARS-CoV-2. However, the lung expresses moderate levels of ACE2. Additionally, SARS-CoV-2 requires co-receptor or supplementary membrane proteins such as cellular protease transmembrane protease serine-2 (TMPRSS2) to facilitate its infection13. Moreover, Alanyl (membrane) Aminopeptidase (ANPEP), Glutamyl Aminopeptidase (ENPEP) and Dipeptidyl peptidase-4 (DPP4) are additional genes correlated with ACE214. ANPEP is mainly expressed in the colon, ileum, rectum, kidney, liver and skin. ENPEP, a member of the peptidase M1 family, is the mammalian type II integral membrane zinc-containing endopeptidases. ENPEP controls blood pressure regulation and blood vessel development through of the renin-angiotensin system pathway15. The connection between ENPEP and viral infection is still mysterious. Severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 pandemic capacity is derived from the unique structural features on its spike protein: fast viral surfing over the epithelium with flat N‐terminal domain, tight binding to ACE2 entry receptor, and furin protease utilization. In addition, the possible involvement of other components such as lipid rafts, CLRs, and neuropilin is, in combination, mediating the accelerated cell entry and other critical steps in its overwhelming contagious capacity and pandemy. Recently it has been proposed that SARS‐CoV‐2 can move rapidly over the cell surface of the lung epithelium interacting with glycalyx sialic acid through its S protein N terminal domain16. The pandemic capacity of SARS Cov 2 is also caused by the binding to the lectin receptors of type C (CLR) exploiting the viral escape‐based “detour” entry without cleavage by protease and neuropilin 1 (NRP1) avoiding the involvement of ACE2. In addition other proteases S protein interacting through its polybasic S1/S2 with surface sugars and receptors and may in theory be using three or more different pathways for cell entry16. Therefore, these unique interactions of the SARS‐CoV‐2 are believed to be the critical pandemic capacity factors. All these genes encode peptidases, which, for mysterious reasons, are emploied by coronavirus as their receptors. Host immune response is essential in the battle against viruses. Commonly, the infected cells produce interferons to destroy viral activities17. In addition, interferons stimulate neighboring cells to upregulate MHC class I molecules making CD8 + T cells able to detect and remove the viral infection18. To date, two questions remain unresolved, namely low prepuberal mortality rates19 and that COVID-19 disproportionally affects men and women20. Men with COVID-19 show an increased risk of complications compared to women (~ 58% vs 42%)4. It has been reported that male have potential risks infertility due to the mild infections at the testicles21. Moreover, meta-analysis studies reported that an increased proportion of men affected by COVID-19 required hospitalization compared with women22. Therefore, male patients contracting the SarsCov2 virus die at twice the rate of females (Table 1)7,22. But only half of them shows viremia which is present in 13% of the symptomatic but non-hospitalized people7. Despite sexual differences in severity and mortality have been associated with a greater incidence of comorbidities (i.e. chronic lung disease, cardiovascular disease, hypertension and diabetes) and high-risk behaviors comprising smoking and alcohol use in men23. These disproportions persisted even after checking for these potential confounders. Sex differences in the immune response are well-known. Indeed, men and women react in a different way to foreign and self-antigens24. Hospitalized patients with SARS-CoV-2 infection have shown higher levels of chemokines, C-reactive protein (CRP) stimulating “cytokine storm”,characterised by significant production of IL-6, from the ongoing infection in the lungs, with sex differences existing in immune responses7,25. The genital infections is not be the case in all SARS-CoV-2 fatalities7. To date, a number of hypotheses have been proposed to clarify the male susceptibility to severe COVID-19 infection, nevertheless, the basic mechanisms or factors of the noticed sex differences have not been fully explained. Some theories have been postulated, one is the effect of sexual hormones affecting immune responses, therefore estrogen reinforces the immune system and testosterone weaken it13, another is the action of androgen on target tissues, such as the lung26. Moreover, sex differences may occur in ACE 2 receptor and the cellular serine protease TMPRSS2, which are responsible for viral entrance and priming, respectively13. Knowledge of gender differences in terms of disease severity, clinical characteristics and mortality is a key point for better disease management, the unfavourable course of the disease prediction and the intervention strategies for both men and women. In this study, we explored the gender differences in the transcriptional landscape of the host response to SARS-CoV-2. In particular, we investigated the expression of known SARS-CoV-2 interacting human proteins and their interaction in the testicles and ovarian tissues, to provide an immediate understanding of variable incidence to SARS-CoV-2 infection and severity of symptoms in men and women.

Table 1.

Differences of SARS-CoV-2 gender susceptibility in different countries (https://globalhealth5050.org/the-sex-gender-and-covid-19-project/).

| Country | Country | Country | Country | Cases (male) | Cases (female) | Deaths date | Deaths were sex-disaggregated | Deaths (male) | Deaths (female) | Deaths in confirmed cases date | Proportion of deaths in confirmed cases (male) | Proportion of deaths in confirmed cases (female) | Proportion of deaths in confirmed cases (Male:female ratio) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Afghanistan | Yes | 21/09/2021 | 122,400 | 59% | 41% | 21/09/2021 | 3888 | 65% | 35% | 21/09/2021 | 4% | 3% | 1,31 |

| Albania | Yes | 10/09/2021 | 164,276 | 48% | 52% | 10/09/2021 | 2594 | 67% | 33% | 10/09/2021 | 2% | 1% | 2,2 |

| Algeria | Partial | 20/05/2021 | 126,156 | 54% | 46% | ||||||||

| Argentina | Yes | 22/09/2021 | 5,202,330 | 49% | 51% | 21/09/2021 | 112,361 | 58% | 42% | 21/09/2021 | 3% | 2% | 1,42 |

| Australia | Yes | 22/09/2021 | 91,832 | 52% | 48% | 22/09/2021 | 1200 | 51% | 49% | 22/09/2021 | 1% | 1% | 0,96 |

| Austria | Yes | 23/09/2021 | 726,873 | 49% | 51% | 23/09/2021 | 10,716 | 53% | 47% | 23/09/2021 | 2% | 1% | 1,18 |

| Azerbaijan | Partial | 06/09/2021 | 445,278 | 49% | 51% | ||||||||

| Bahrain | Partial | 06/07/2020 | 6081 | 88% | 12% | ||||||||

| Bangladesh | Yes | 21/09/2021 | 1,544,238 | 71% | 29% | 21/09/2021 | 27,251 | 77% | 23% | 21/09/2021 | 2% | 1% | 1,37 |

| Barbados | Yes | 23/09/2021 | 7065 | 50% | 50% | 02/02/2021 | 13 | 62% | 38% | 02/02/2021 | 1% | 1% | 1,12 |

| Belgium | Yes | 20/09/2021 | 1,223,766 | 47% | 53% | 21/09/2021 | 25,499 | 51% | 49% | 21/09/2021 | 2% | 2% | 1,17 |

| Belize | Yes | 20/09/2021 | 18,902 | 51% | 49% | 20/09/2021 | 395 | 64% | 36% | 20/09/2021 | 3% | 2% | 1,7 |

| Bermuda | Yes | 12/08/2021 | 2663 | 45% | 55% | 22/09/2021 | 45 | 56% | 44% | 12/08/2021 | 1% | 1% | 1,38 |

| Bhutan | Yes | 20/09/2021 | 2597 | 61% | 39% | 20/09/2021 | 3 | 67% | 33% | 20/09/2021 | 1,26 | ||

| Bosnia and Herzegovina | Yes | 21/09/2021 | 148,518 | 52% | 48% | 21/09/2021 | 5730 | 61% | 39% | 21/09/2021 | 5% | 3% | 1,46 |

| Botswana | Partial | 17/07/2020 | 48 | 83% | 17% | 28/09/2020 | 15 | 40% | 60% | ||||

| Brazil | Yes | 19/12/2020 | 565,465 | 56% | 44% | 11/09/2021 | 534,119 | 56% | 44% | 19/12/2020 | 33% | 31% | 1,06 |

| Bulgaria | Partial | 25/05/2020 | 2443 | 49% | 51% | ||||||||

| Burkina Faso | Yes | 20/09/2021 | 14,052 | 63% | 37% | 25/08/2020 | 55 | 75% | 25% | 25/08/2020 | 5% | 3% | 1,54 |

| Cabo Verde | Yes | 20/09/2021 | 36,924 | 47% | 53% | 11/07/2021 | 286 | 48% | 52% | 27/12/2020 | 1% | 1% | 1,53 |

| Cambodia | Yes | 03/05/2021 | 15,351 | 43% | 57% | 03/05/2021 | 106 | 57% | 43% | 03/05/2021 | 1% | 1% | 1,76 |

| Canada | Yes | 16/09/2021 | 1,552,308 | 50% | 50% | 16/09/2021 | 27,180 | 51% | 49% | 16/09/2021 | 2% | 2% | 1,03 |

| Cayman Islands | Partial | 16/12/2020 | 302 | 53% | 47% | ||||||||

| Central African Republic | Partial | 16/05/2021 | 7010 | 68% | 32% | ||||||||

| Chad | Yes | 17/07/2021 | 3697 | 69% | 31% | 16/05/2021 | 114 | 79% | 21% | 16/05/2021 | 4% | 3% | 1,4 |

| Chile | Yes | 22/09/2021 | 1,964,150 | 50% | 50% | 07/05/2020 | 294 | 60% | 40% | 07/05/2020 | 1% | 1% | 1,32 |

| China | Yes | 28/02/2020 | 55,924 | 51% | 49% | 28/02/2020 | 2114 | 64% | 36% | 28/02/2020 | 5% | 3% | 1,68 |

| Colombia | Yes | 20/09/2021 | 4,942,249 | 48% | 52% | 20/09/2021 | 125,924 | 61% | 39% | 20/09/2021 | 3% | 2% | 1,73 |

| Congo | Partial | 15/11/2020 | 5632 | 72% | 28% | ||||||||

| Costa Rica | Yes | 21/09/2021 | 521,182 | 50% | 50% | 21/09/2021 | 6098 | 61% | 39% | 21/09/2021 | 1% | 1% | 1,56 |

| Croatia | Partial | 19/09/2021 | 392,248 | 47% | 53% | ||||||||

| Cuba | Partial | 13/12/2020 | 9492 | 53% | 47% | 17/07/2021 | 1906 | 57% | 43% | ||||

| Cyprus | Partial | 21/09/2021 | 117,926 | 50% | 50% | ||||||||

| Czech Republic | Yes | 21/09/2021 | 1,665,737 | 49% | 51% | 15/09/2021 | 30,417 | 57% | 43% | 19/07/2021 | 2% | 2% | 1,43 |

| Denmark | Yes | 21/09/2021 | 355,603 | 50% | 50% | 21/09/2021 | 2633 | 54% | 46% | 21/09/2021 | 1% | 1% | 1,19 |

| Djibouti | Partial | 02/06/2020 | 3779 | 68% | 32% | ||||||||

| Dominican Republic | Yes | 28/08/2020 | 93,732 | 51% | 49% | 30/08/2020 | 1710 | 66% | 34% | 28/08/2020 | 2% | 1% | 1,88 |

| Ecuador | Yes | 25/07/2021 | 474,212 | 51% | 49% | 25/07/2021 | 30,569 | 53% | 47% | 25/07/2021 | 7% | 6% | 1,07 |

| El Salvador | Partial | 22/09/2021 | 102,024 | 50% | 50% | ||||||||

| England | Yes | 23/09/2021 | 6,646,405 | 48% | 52% | 23/09/2021 | 158,152 | 56% | 44% | 23/09/2021 | 3% | 2% | 1,39 |

| Equatorial Guinea | Yes | 15/09/2021 | 11,063 | 58% | 42% | 07/06/2021 | 113 | 67% | 33% | 07/06/2021 | 2% | 1% | 1,47 |

| Estonia | Yes | 20/09/2021 | 149,097 | 46% | 54% | 13/09/2021 | 1313 | 52% | 48% | 14/06/2021 | 1% | 1% | 1,24 |

| Eswatini | Yes | 18/04/2021 | 18,417 | 48% | 52% | 20/04/2021 | 671 | 52% | 48% | 20/04/2021 | 4% | 3% | 1,14 |

| Ethiopia | Partial | 29/06/2020 | 5846 | 61% | 39% | ||||||||

| Faroe Islands | Partial | 21/09/2021 | 944 | 54% | 46% | ||||||||

| Finland | Yes | 21/09/2021 | 137,117 | 53% | 47% | 21/09/2021 | 1059 | 54% | 46% | 21/09/2021 | 1% | 1% | 1,04 |

| France | Yes | 18/09/2021 | 6,737,561 | 47% | 53% | 16/09/2021 | 88,518 | 58% | 42% | 16/09/2021 | 2% | 1% | 1,55 |

| French Polynesia | Partial | 04/10/2020 | 2228 | 49% | 51% | 29/09/2020 | 7 | 43% | 57% | ||||

| Gabon | Partial | 26/08/2020 | 8409 | 40% | 60% | ||||||||

| Gambia | Partial | 19/09/2021 | 9775 | 59% | 41% | ||||||||

| Germany | Yes | 20/09/2021 | 4,126,341 | 49% | 51% | 20/09/2021 | 92,919 | 53% | 47% | 20/09/2021 | 2% | 2% | 1,17 |

| Ghana | Partial | 21/09/2021 | 124,309 | 58% | 42% | ||||||||

| Gibraltar | Partial | 06/01/2021 | 10 | 80% | 20% | ||||||||

| Greece | Yes | 22/09/2021 | 634,298 | 51% | 49% | 22/09/2021 | 14,575 | 57% | 43% | 22/09/2021 | 3% | 2% | 1,27 |

| Guatemala | Yes | 20/09/2021 | 531,650 | 51% | 49% | 20/09/2021 | 13,115 | 66% | 34% | 20/09/2021 | 3% | 2% | 1,88 |

| Guernsey | Partial | 11/05/2020 | 252 | 37% | 63% | 03/02/2021 | 13 | 38% | 62% | ||||

| Guinea | Partial | 23/03/2021 | 20,267 | 66% | 34% | ||||||||

| Guinea-Bissau | Yes | 20/06/2021 | 3825 | 60% | 40% | 20/06/2021 | 69 | 70% | 30% | 20/06/2021 | 2% | 1% | 1,5 |

| Guyana | Partial | 20/09/2021 | 29,647 | 48% | 52% | ||||||||

| Haiti | Yes | 15/09/2021 | 116,433 | 54% | 46% | 12/06/2021 | 361 | 57% | 43% | 12/06/2021 | 2% | 2% | 1,1 |

| Honduras | Partial | 14/09/2020 | 67,789 | 52% | 48% | ||||||||

| Hong Kong | Yes | 20/09/2021 | 12,166 | 48% | 52% | 20/09/2021 | 213 | 59% | 41% | 20/09/2021 | 2% | 1% | 1,57 |

| Iceland | Partial | 21/06/2020 | 1823 | 50% | 50% | ||||||||

| India | Yes | 18/05/2021 | 24,766,088 | 61% | 39% | 21/05/2020 | 3711 | 64% | 36% | 06/04/2020 | 3% | 3% | 0,85 |

| Indonesia | Yes | 21/09/2021 | 4,195,958 | 49% | 51% | 21/09/2021 | 140,805 | 52% | 48% | 21/09/2021 | 4% | 3% | 1,16 |

| Iran | Yes | 17/03/2020 | 14,991 | 57% | 43% | 17/03/2020 | 853 | 59% | 41% | 17/03/2020 | 6% | 5% | 1,09 |

| Iraq | Yes | 20/09/2021 | 1,978,412 | 61% | 39% | 20/09/2021 | 21,869 | 58% | 42% | 20/09/2021 | 1% | 1% | 0,87 |

| Isle of Man | Partial | 20/09/2021 | 7208 | 51% | 49% | ||||||||

| Israel | Yes | 20/09/2021 | 1,219,265 | 48% | 52% | 20/09/2021 | 7555 | 56% | 44% | 20/09/2021 | 1% | 1% | 1,42 |

| Italy | Yes | 15/09/2021 | 4,616,789 | 49% | 51% | 15/09/2021 | 129,558 | 56% | 44% | 15/09/2021 | 3% | 2% | 1,35 |

| Jamaica | Yes | 21/09/2021 | 81,828 | 43% | 57% | 20/09/2021 | 1772 | 52% | 48% | 20/09/2021 | 3% | 2% | 1,42 |

| Japan | Partial | 22/06/2020 | 17,301 | 55% | 45% | 21/09/2021 | 13,522 | 58% | 42% | ||||

| Jersey | Yes | 23/09/2021 | 9885 | 51% | 49% | 23/09/2021 | 78 | 62% | 38% | 23/09/2021 | 1% | 1% | 1,56 |

| Jordan | Yes | 22/09/2021 | 764,998 | 50% | 50% | 22/09/2021 | 10,637 | 60% | 40% | 22/09/2021 | 2% | 1% | 1,52 |

| Kazakhstan | Partial | 08/06/2020 | 9452 | 61% | 39% | ||||||||

| Kenya | Yes | 19/09/2021 | 245,680 | 58% | 42% | 19/09/2021 | 4993 | 65% | 35% | 19/09/2021 | 2% | 2% | 1,32 |

| Kosovo | Yes | 21/09/2021 | 159,488 | 47% | 53% | 21/09/2021 | 2917 | 59% | 41% | 21/09/2021 | 2% | 1% | 1,62 |

| Kyrgyzstan | Yes | 16/07/2020 | 12,498 | 47% | 53% | 16/07/2020 | 155 | 62% | 38% | 16/07/2020 | 2% | 1% | 1,83 |

| Latvia | Yes | 22/09/2021 | 151,917 | 44% | 56% | 22/09/2021 | 2665 | 50% | 50% | 22/09/2021 | 2% | 2% | 1,29 |

| Lebanon | Partial | 15/02/2021 | 339,122 | 54% | 46% | 06/07/2020 | 36 | 31% | 69% | ||||

| Liberia | Yes | 17/07/2021 | 5396 | 65% | 35% | 17/07/2021 | 148 | 66% | 34% | 17/07/2021 | 3% | 3% | 1,04 |

| Liechtenstein | Partial | 20/09/2021 | 3301 | 49% | 51% | ||||||||

| Lithuania | Yes | 21/09/2021 | 314,926 | 44% | 56% | 21/09/2021 | 4830 | 49% | 51% | 21/09/2021 | 2% | 1% | 1,23 |

| Luxembourg | Yes | 22/09/2021 | 77,552 | 50% | 50% | 22/09/2021 | 835 | 55% | 45% | 22/09/2021 | 1% | 1% | 1,22 |

| Malawi | Yes | 07/02/2021 | 27,422 | 59% | 41% | 05/01/2021 | 196 | 76% | 24% | 05/01/2021 | 3% | 2% | 1,5 |

| Maldives | Yes | 21/09/2021 | 83,311 | 59% | 41% | 21/09/2021 | 229 | 60% | 40% | 21/09/2021 | 1,05 | ||

| Mexico | Yes | 22/09/2021 | 3,596,279 | 50% | 50% | 22/09/2021 | 273,377 | 62% | 38% | 22/09/2021 | 9% | 6% | 1,63 |

| Moldova | Yes | 19/09/2021 | 282,650 | 41% | 59% | 19/09/2021 | 6605 | 49% | 51% | 19/09/2021 | 3% | 2% | 1,35 |

| Montenegro | Partial | 21/09/2021 | 126,837 | 49% | 51% | 15/03/2021 | 83,685 | 49% | 51% | ||||

| Morocco | Yes | 18/07/2020 | 17,015 | 53% | 47% | 21/09/2020 | 1855 | 66% | 34% | 18/07/2020 | 3% | 2% | 1,8 |

| Myanmar | Yes | 10/09/2020 | 2265 | 53% | 47% | 28/09/2020 | 226 | 64% | 36% | 01/09/2020 | 1% | 3,84 | |

| Nepal | Yes | 21/09/2021 | 782,180 | 59% | 41% | 06/09/2021 | 10,833 | 66% | 34% | 06/09/2021 | 2% | 1% | 1,32 |

| Netherlands | Yes | 20/09/2021 | 1,987,815 | 48% | 52% | 20/09/2021 | 18,128 | 55% | 45% | 20/09/2021 | 1% | 1% | 1,31 |

| New Zealand | Yes | 22/09/2021 | 4114 | 51% | 49% | 22/09/2021 | 27 | 52% | 48% | 22/09/2021 | 1% | 1% | 1,05 |

| Nigeria | Yes | 08/08/2021 | 160,006 | 60% | 40% | 08/08/2021 | 1569 | 71% | 29% | 08/08/2021 | 1% | 1% | 1,62 |

| North Macedonia | Yes | 22/09/2021 | 187,618 | 50% | 50% | 22/09/2021 | 6509 | 62% | 38% | 22/09/2021 | 4% | 3% | 1,63 |

| Northern Ireland | Yes | 22/09/2021 | 230,382 | 48% | 52% | 23/09/2021 | 2524 | 54% | 46% | 23/09/2021 | 1% | 1% | 1,28 |

| Norway | Yes | 22/09/2021 | 183,808 | 53% | 47% | 22/09/2021 | 850 | 54% | 46% | 22/09/2021 | 1,05 | ||

| Pakistan | Yes | 18/08/2020 | 289,832 | 74% | 26% | 18/08/2020 | 6190 | 74% | 26% | 18/08/2020 | 2% | 2% | 1,01 |

| Panama | Yes | 14/08/2020 | 79,402 | 54% | 46% | 05/06/2020 | 373 | 68% | 32% | 05/06/2020 | 3% | 2% | 1,47 |

| Paraguay | Yes | 14/03/2021 | 180,014 | 48% | 52% | 14/03/2021 | 3476 | 61% | 39% | 14/03/2021 | 2% | 1% | 1,66 |

| Peru | Yes | 20/09/2021 | 2,168,430 | 51% | 49% | 20/09/2021 | 199,226 | 64% | 36% | 20/09/2021 | 11% | 7% | 1,67 |

| Philippines | Yes | 21/09/2021 | 2,401,916 | 51% | 49% | 21/09/2021 | 37,074 | 56% | 44% | 21/09/2021 | 2% | 1% | 1,26 |

| Poland | Partial | 05/02/2021 | 11,451 | 57% | 43% | ||||||||

| Portugal | Yes | 22/09/2021 | 1,063,252 | 46% | 54% | 22/09/2021 | 17,933 | 52% | 48% | 22/09/2021 | 2% | 1% | 1,28 |

| Republic of Ireland | Yes | 18/09/2021 | 375,259 | 49% | 51% | 18/09/2021 | 5193 | 53% | 47% | 18/09/2021 | 1% | 1% | 1,17 |

| Romania | Yes | 19/09/2021 | 1,152,052 | 46% | 54% | 19/09/2021 | 35,592 | 57% | 43% | 19/09/2021 | 4% | 2% | 1,57 |

| Rwanda | Yes | 21/09/2021 | 95,503 | 49% | 51% | 21/09/2021 | 1215 | 55% | 45% | 21/09/2021 | 1% | 1% | 1,28 |

| Saint Lucia | Yes | 17/09/2021 | 10,237 | 45% | 55% | 08/03/2021 | 39 | 87% | 13% | 31/01/2021 | 2% | 6,73 | |

| Scotland | Yes | 19/09/2021 | 535,527 | 48% | 52% | 19/09/2021 | 10,826 | 51% | 49% | 19/09/2021 | 2% | 2% | 1,13 |

| Serbia | Partial | 03/05/2020 | 193 | 62% | 38% | ||||||||

| Sierra Leone | Partial | 21/09/2021 | 6393 | 59% | 41% | ||||||||

| Singapore | Partial | 05/05/2020 | 6530 | 89% | 11% | ||||||||

| Slovakia | Yes | 20/09/2021 | 403,802 | 48% | 52% | 16/07/2021 | 12,455 | 54% | 46% | 15/06/2021 | 4% | 3% | 1,27 |

| Slovenia | Yes | 22/09/2021 | 287,176 | 47% | 53% | 19/09/2021 | 4824 | 49% | 51% | 15/08/2021 | 2% | 2% | 1,07 |

| Somalia | Partial | 22/09/2021 | 19,235 | 71% | 29% | ||||||||

| South Africa | Yes | 22/09/2021 | 2,857,730 | 43% | 57% | 22/09/2021 | 91,959 | 48% | 52% | 22/09/2021 | 4% | 3% | 1,23 |

| South Korea | Yes | 21/09/2021 | 289,263 | 52% | 48% | 21/09/2021 | 2413 | 50% | 50% | 21/09/2021 | 1% | 1% | 0,92 |

| Spain | Yes | 22/09/2021 | 4,932,891 | 48% | 52% | 22/09/2021 | 85,832 | 55% | 45% | 22/09/2021 | 2% | 2% | 1,33 |

| Sweden | Yes | 22/09/2021 | 1,147,876 | 49% | 51% | 23/09/2021 | 14,813 | 55% | 45% | 23/09/2021 | 1% | 1% | 1,25 |

| Switzerland | Yes | 22/09/2021 | 830,013 | 48% | 52% | 22/09/2021 | 10,643 | 54% | 46% | 22/09/2021 | 1% | 1% | 1,26 |

| Taiwan | Yes | 21/09/2021 | 16,152 | 51% | 49% | 20/04/2021 | 11 | 82% | 18% | 20/04/2021 | 2% | 4,27 | |

| Thailand | Yes | 01/11/2020 | 3784 | 56% | 44% | 01/04/2021 | 93 | 75% | 25% | 01/11/2020 | 2% | 1% | 2,49 |

| Tunisia | Yes | 10/01/2021 | 162,350 | 44% | 56% | 10/01/2021 | 5310 | 66% | 34% | 10/01/2021 | 5% | 2% | 2,47 |

| Turkey | Yes | 25/10/2020 | 362,800 | 51% | 49% | 25/10/2020 | 9799 | 62% | 38% | 25/10/2020 | 3% | 2% | 1,56 |

| USA | Yes | 20/09/2021 | 32,683,710 | 48% | 52% | 15/09/2021 | 658,754 | 55% | 45% | 09/09/2021 | 2% | 2% | 0,77 |

| Uganda | Yes | 09/07/2021 | 48,646 | 61% | 39% | 09/07/2021 | 364 | 69% | 31% | 09/07/2021 | 1% | 1% | 1,43 |

| Ukraine | Yes | 24/09/2021 | 2,379,483 | 40% | 60% | 22/09/2021 | 55,424 | 53% | 47% | 22/09/2021 | 3% | 2% | 1,69 |

| Venezuela | Partial | 22/09/2021 | 358,462 | 51% | 49% | ||||||||

| Vietnam | Yes | 12/09/2021 | 475,831 | 48% | 52% | 11/07/2021 | 86 | 43% | 57% | 11/07/2021 | 0,96 | ||

| Wales | Yes | 22/09/2021 | 335,046 | 46% | 54% | 22/09/2021 | 5837 | 56% | 44% | 22/09/2021 | 2% | 1% | 1,48 |

| Yemen | Yes | 20/05/2021 | 6617 | 64% | 36% | 20/05/2021 | 1256 | 70% | 30% | 20/05/2021 | 21% | 16% | 1,31 |

| Zimbabwe | Yes | 12/12/2020 | 11,219 | 55% | 45% | 12/12/2020 | 307 | 62% | 38% | 12/12/2020 | 3% | 2% | 1,33 |

Materials and methods

Ethical compliance

This investigation does not contain any studies with human participants or animals performed by any of the authors, and therefore no ethical compliance is required.

Data selection by SARS-CoV-2 Human protein atlas (HPA) program

The SARS-CoV-2 HPA program (HPA, https://www.proteinatlas.org/humanproteome/sars-cov-2) provides a freely available information source on the tissue and cellular expression patterns of known SARS-CoV-2 interacting human proteins, based on transcriptomics and antibody-based proteomics. Genes associated with inflammatory processes, such as chemokines, cytokines, metalloproteinase, as well as bone marrow stromal antigen 2 or tetherin (BST2), ANPEP, ENPEP, forkhead box P3 (FOXP3), GATA Binding Protein 1 (GATA1), High Mobility Group1 (HMGB1), Interferon Regulatory Factor (IRF1 and 2), and Serine/Cysteine Proteinase Inhibitor Clade G Member 1 (SERPING1), were integrated with the list of SARS-CoV-2 HPA program filtered on the basis of their selective expression on testis and ovary tissue. Moreover, the androgen and estrogen receptors (AR and ER) were also considered.

In silico gene–gene interaction using GeneMANIA

The total list of genes belonging to the testicles or ovaries were given to the GeneMANIA plugin in Cytoscape to evaluate their interactome and possible biological functions. GeneMANIA is a Gene Multiple Association Network Integration Algorithm and tests the weights from data sources based on their predicted value to re-establish the query list. GeneMANIA generates speculation regarding gene function, analyzing gene lists, and prioritizing functional genes for functional evaluation. It then expands the query list with practically identical genes that have common characteristics with the initial query genes and display an interactive, applicable association network, allowing the genes to reveal the relationship between datasets27. Cytoscape (version:3.8.2, http://www.cytoscape.org/) was used to visualize and analyze the protein–protein interaction (PPI) network. This software allows users to construct a composite gene–gene functional interaction network from input lists of genes, taking into account experimental and in silico interactions28. In particular, the GeneMANIA app uses association data, including protein and genetic interactions, pathways, co-expression and co-localization similarity information and protein domain similarity data. In a given network, each gene is represented as a node and the interactions between the nodes are defined as edges. Topological parameters of the networks were analyzed using the Network-Analyzer plugin in Cytoscape. In particular, in this study, we focused on the degree of centrality of a node, representing the number of edges linked to a given node. In this context, nodes having a high degree of centrality represent the network hub genes. Finally, we focused our analysis on the direct interaction between SARS-CoV-2 interacting human proteins, other immune/inflammation-associated candidates and the androgen and estrogen receptors on testis- and ovary-associated networks, respectively.

Functional enrichment analysis

To identify biological process terms that are overrepresented in the list of proteins in both testis- and ovary-associated networks, a Gene Ontology (GO) functional enrichment analysis was performed using the Biological Networks Gene Ontology tool (BiNGO, version 3.0.3) in Cytoscape v.3.8.2 (http://www.cytoscape.org/)29. Significantly enriched GO terms were identified using hypergeometric tests and corrected by Benjamini and Hochberg false discovery rate (FDR) adjustment, and p ≤ 0.05 was applied as a cutoff for statistical significance.

Results

Sex is a discriminating index in human proteins interacting in testicles and ovaries of SARS-CoV-2 patients

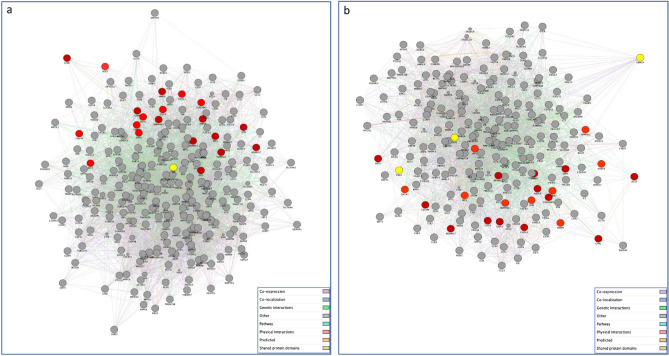

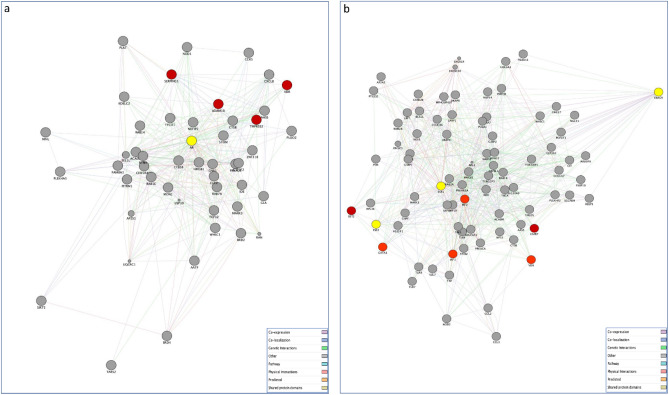

As expected, our analysis highlighted a difference in the number of the SARS-CoV-2 interacting human proteins selectively expressed in gonadal tissue, with a total of 386 protein-encoding genes for testicles and 268 genes for ovaries. This preliminary data show that there are more human proteins interacting with SARS-CoV-2 in the testicles than in the ovaries. We then used the Cytoscape GeneMANIA application to construct gene networks of the proposed SARS-CoV-2 targeted human proteins expressed in both the testis and ovary to investigate their interaction with our genes of interest (Fig. 1a,b) and with the androgen and estrogen receptors, respectively (Fig. 2a,b). The testis-associated PPI network consisted of 267 nodes (proteins) and 5245 edges (interactions). In particular, the majority of connections were co-expression interactions (55.26%), followed by physical interactions (21.45%), 9.67% of predicted protein interactions, 6.28% with co-localisation, 4% with genetic interactions, 2.11% pathway and 1.24% with shared protein domains. Furthermore, the ovary-related network included 223 nodes and 3726 edges. Also in this case, the majority of connections were co-expression interactions (47.79%), followed by physical interactions (30.83%), 8.36% of predicted protein interactions, 6.91% with co-localisation, 3.13% with genetic interactions, 1.57% pathway and 1.41% with shared protein domains. Next, for clarity, we filtered all the testis- and ovary-associated networks focusing our attention on the direct interactions with hormone receptor genes, AR and Estrogen Receptor Binding Site Associated Antigen 9 (EBAG9), ESR1, ESR2, respectively. The resulting networks consisted of 49 nodes (318 edges) for the testis-related network and 82 nodes (634 edges) for the ovary-related network.

Figure 1.

Gene networks of SARS-CoV-2 targeted human proteins expressed in testis (a) and ovary (b) and their interactions with the list of genes of our interest. The PPI network constructed by GeneMANIA shows the relationships for SARS-CoV-2 targeted human proteins expressed in testis (a) and ovary (b) and the genes of interest (nodes) connected (with edges) according to the functional association networks from the databases. Differently colored ‘edges’ indicate the type of evidence supporting each interaction: co-expression (light purple), physical interaction (pink), genetic interaction (green), shared protein domains (golden yellow), pathway (light blue), predicted (orange), and co-localization (blue).

Figure 2.

Gene networks of SARS-CoV-2 targeted human proteins expressed in testis (a) and ovary (b) and their interactions with the list of genes of our interest and gonadal steroid hormones. The PPI network constructed by GeneMANIA shows the interconnection between SARS-CoV-2 targeted human proteins expressed in testis (a) and ovary (b), the genes of interest and androgen and estrogen receptors, respectively. The edges between nodes (proteins) indicate interactions based on the GeneMANIA database information. Differently colored ‘edges’ indicate the type of evidence supporting each interaction: co-expression (light purple), physical interaction (pink), genetic interaction (green), shared protein domains (golden yellow), pathway (light blue), predicted (orange), and co-localization (blue). A detailed view of both (a) and (b) networks for each different interaction type is provided in Supplementary Fig. S1.

Functional enrichment analysis and identification of key genes

To obtain a more in-depth understanding of the biological processes associated with all the PPI networks, GO enrichment analysis was performed using the BINGO plugin in Cytoscape. The over-represented GO terms (adjusted P < 0.05) were mainly associated with the regulation of cell activation, leukocyte activation, peptide transport, and immune response for both ovary and testis-related network (Tables 2 and 3).

Table 2.

GO enrichment analysis Ovary Network.

| GO I.D | Background genes | Genes | Description | FDR value | P-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| GO.0060135 | 60 | 6 | Maternal process involved in female pregnancy | 9.2E−4 | 9.9E−5 |

| GO.0046631 | 60 | 6 | Alpha–beta T cell activation | 9.2E−4 | 9.9E−5 |

| GO.0009755 | 171 | 8 | Hormone-mediated signaling pathway | 0.0064 | 9.9E−4 |

| GO.0002757 | 332 | 15 | Immune response-activating signal transduction | 1.3E−4 | 9.93E−6 |

| GO.0043434 | 362 | 14 | Response to peptide hormone | 9.2E−4 | 9.91E−5 |

| GO.0051259 | 512 | 15 | Protein complex oligomerization | 0.0064 | 9.8E−4 |

| GO.0030155 | 623 | 17 | Regulation of cell adhesion | 0.0064 | 9.8E−4 |

| GO.0002705 | 109 | 10 | Positive regulation of leukocyte mediated immunity | 1.95E−5 | 9.84E−7 |

| GO.0001819 | 390 | 25 | Positive regulation of cytokine production | 1.03E−9 | 9.7E−12 |

| GO.0031347 | 676 | 31 | Regulation of defense response | 7.22E−9 | 9.6E−11 |

Table 3.

GO enrichment analysis testis network.

| GO I.D | Background genes | Genes | Description | FDR value | P-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| GO.0044257 | 562 | 23 | Cellular protein catabolic process | 9.93E−5 | 4.75E−6 |

| GO.0051050 | 892 | 33 | Positive transport regulation | 9.78E−6 | 3.36E−7 |

| GO.0002730 | 4 | 3 | Regulation of dendritic cell cytokine production | 9.6E−4 | 8.11E−5 |

| GO.0007052 | 70 | 7 | Mitotic spindle organization | 9.5E−4 | 7.98E−5 |

| GO.0002702 | 84 | 9 | Positive regulation of production of molecular mediator of immune response | 9.56E−5 | 4.55E−6 |

| GO.0036230 | 502 | 33 | Granulocyte activation | 9.47E−11 | 3.14E−13 |

| GO.0002682 | 1391 | 49 | Regulation of immune system process | 9.46E−8 | 1.45E−9 |

| GO.0006508 | 1203 | 37 | Proteolysis | 9.46E−5 | 4.49E−6 |

| GO.0051704 | 2514 | 77 | Multi-organism process | 9.42E−10 | 6.24E−12 |

| GO.0032722 | 56 | 11 | Positive regulation of chemokine production | 9.35E−8 | 1.41E−9 |

The subsequent network topological analysis identified 4 hub genes common to both networks, highlighted in bold form into Table 4, with radixin (RDX) showing the higher connectivity degrees in both PPI networks (n = 92 in the testis network and n = 80 in the ovary network), followed by HMGB1 (n = 87 in the testis network and n = 72 in the ovary network), RAB5C (n = 81 in the testis network and n = 69 in the ovary network) and IRF2 (n = 81 in the testis network and n = 74 in the ovary network) (Table 4). In addition, among the network-specific hub genes, we identified SERPING1, CC chemokine receptor-5 (CCR5), TMPRSS2, and ADAM10 as the high-degree nodes within the testis-associated network, and BST2, GATA1, ENPEP, TLR4, TLR7, IRF1, and IRF2 within the ovary-related network. Detailed information is provided in Tables S1 and S2 of supplemental materials.

Table 4.

Connectivity degrees in both PPI networks.

| OVARIES | TESTICLES | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Gene name | Degree | Gene | Degree |

| RDX | 80 | RDX | 92 |

| IRF2 | 74 | HMGB1 | 87 |

| HMGB1 | 72 | RAB5C | 81 |

| RAB5C | 69 | IRF2 | 81 |

| RAB2A | 64 | GTF2F2 | 79 |

Discussion

In this study we explored the gender variation in the transcriptional landscape of SARS-CoV-2 infection to provide an immediate understanding of variable susceptibility and COVID-19 manifestations in men and women. In fact, typical gene expression connected with predisposed tissue can claryfy the cellular response to the SARS-CoV-2 infection. In particular, expression of human proteins that interact with SARS-CoV-2 in the testicles and ovarian tissue and the relative interactions were analyzed in order to evaluate their potential association with sexual difference in the likelihood of infection and severity of symptoms. The analysis displayed that some genes expressed in the testis network were not present in the ovarian network and vice versa. Within the testis network we found TMPRSS2, ADAM10, SERPING1, and CCR5, while within the ovary network we found BST2, GATA1, ENPEP, TLR4, TLR7, IRF1, and IRF2 (See Supplementary materials Fig. S1 and Tables S1 and S2).

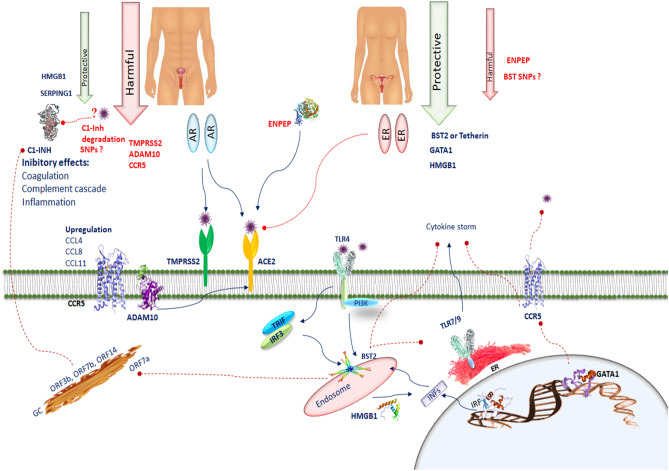

Testicular tissue shows high ACE2 mRNA and protein expression levels9, which act as functional receptors for the coronavirus. In fact, to infect cells the COVID-19 spike adheres to ACE2 cell surface receptor30. Male sex hormones facilitate SARS-CoV-2 access into host cells affecting the ACE-2 pathway31. This priming is also carried out by TMPRSS213. Activation of the androgen receptor increases TMPRSS2 levels through the androgen response element present in its promoter in many tissues. TMPRSS2 expression is greater in male lungs than in female lungs. In our analysis we found that TMPRSS2 was present in the testis. This may be one of the effects that could clarify the prevalence and severity of COVID-19 observed in men32. ACE-2, like TMPRSS2, is regulated by the androgen receptor. Therefore, it is possible that lowering androgen hormones could reduce the transcription of TMPRSS2, probably by decreasing the expression of ACE-233. However, estrogen can contribute to the protection against virus infection, as demonstrated by a previous study exploring the role of sex hormones in the survival rate of SARS‐CoV infected male and female mice34. In this investigation it was observed that ovariectomized female mice had a severe form of the disease compared to controls. Moreover, fulvestrant, an estrogen nuclear receptor antagonist, reduced the survival rate in females. Instead, castrated male mice did not display an increased mortality rate due to SARS‐CoV infection compared to the control group, demonstrating that the predisposition to SARS‐CoV severity could be sex‐related, and estrogen may exet significant role in disease onset35. Therefore, estrogen can play a protective effect against COVID-19. Pre‐treatment with estrogens has a protective action in acute lung injury, as a result of the preventive anti‐inflammatory effects36. 17β‐estradiol modulates ACE2 gene expression levels, further supporting the role of sex hormones in COVID‐1937. Pulmonary NHBE cell line treated with 17β‐estradiol promoted a reduction in ACE2 gene expression. A link between the decrease in viral load and TMPRSS2 expression by estrogen treatment was also demonstrated. Despite the fact that no direct effects of estrogens on SARS‐CoV‐2 before cell infection were demonstrated, these hormones are able to decrease SARS‐CoV‐2 infection in vitro38. Angiotensin 1–7 may prevent ischemic cardiac damage and acute respiratory distress syndrome. In an animal experiment, long-term angiotensin 1–7 infusion resulted in strong antioxidant and vasodilating effects in female rats. But, the positive effect of long-term angiotensin 1–7 infusion in male rats was lacking39. It is likely that estrogen may strengthen the vasodilator and antioxidant properties of angiotensin 1–7. In addition, estrogen enhancement induces ER-α upregulation in T lymphocytes increasing the release of interferon I and III from T lymphocytes which alleviates the COVID-19 infection40 (Fig. 3).

Figure 3.

SERPING1 encodes C1INH, which suppresses complement and coagulation cascades and prevents inflammation. SERPING1 in the testis could prevent thrombotic risk. The interaction of several CoV2 proteins (ORF 3b, ORF7b, ORF14, nsp2ab, nsp13ab, nsp14ab and nsp8ab) with C1-INH can be inhibited during viral infection, leading to a predisposition to activate the complement cascade, the bradykinin pathway and the intrinsic coagulation cascade. The deletion in N-terminal region of SERPING1 by SARS-CoV-2 may block its function and increase inflammatory processes. Deteriorated SERPING1 expression caused by CoV2 interacting proteins could activate the intrinsic coagulation pathway, inducing a pro-coagulant state. CCR5 is involved in the pathology of SARS-CoV-2. In SARS-CoV-2 the chemotactic factors such as CCL4, CCL8, and CCL11 sharing CCR5 as a receptor are upregulated. ADAM10 is correlated with ACE2 cleavage regulation in human airway epithelia. BST2 reduces SARS-CoV-2 RNA replication. BST-2 is strongly induced after exposure to IFN through IRF1. BST2 expression is modulated by the TLR4/PI3K signaling pathway. Activation of TLR4 results in TRIF/IRF3-mediated positive regulation of BST-2. TLR7, TLR8 and TLR9 are predominantly localized in intracellular compartments and form the key gatekeepers in detecting and combating viral infections. In COVID-19 patients, host tetherin-mediated virion endocytosis may control TLR9 recognition to restrain immune cell responses. Several host factors such as the HMGB1 facilitate entry of self-DNA into the endosomes of pDCs, where they trigger TLR9 to induce type 1 IFN responses. GATA-1 is a potent repressor of CCR5 expression. CCR5 inhibition decreases IL-6 and SARS-CoV-2 plasma viremia.

ADAM10, SERPING1 and CCR5 in the testis network

Disintegrin and Metalloproteases (ADAMs) belong to metzincin family of metalloproteases41. ADAMs are proteins ubiquitously expressed and regulate sperm–egg interactions, migration, cell proliferation, and differentiation. ADAM10 is expressed in the brain42 and control Central Nervous System (CNS) processes, such as development, synaptogenesis and axon targeting. At the synapse and in synaptic vesicles it acts as a sheddase of other synaptic proteins43 and regulates axon guidance and synaptic functions by leading the cleavage of synaptic proteins, such as Amyloid Precursor Protein, Neuronal Cell Adhesion Molecule and neuroligins. ADAM10 promotes microglia-mediated synapse removal by cleaving the chemokine fractalkine (CX3CL1), a ligand of CX3C chemokine receptor 1 (CX3CR1)44. In addition, ADAM10 is broadly expressed in intestinal epithelial cells45 and modulates intestinal permeability by repressing the transmembrane Notch proteins46 and E-cadherin which is one of the most important junction molecules involved in the preservation of structural integrity of the intestinal epithelial47. The Notch receptor is a substrate of ADAM10 and controls intestinal homeostasis48. Hence, the ADAM10-mediated shedding of the Notch receptor and E-cadherin downregulates epithelial cell migration and adhesion and protects intestinal barrier. In addition, ADAM10 is connected with ACE2 cleavage regulation in human airway epithelia49. Since ADAM10 regulates proteolytic cleavage of several key proteins acting in synapse formation, axon signaling and cell adhesion and regulating intestinal permeability it could aid in activating key pathways that are altered in COVID-19 pathogenesis.

Our analyses show a selective involvement of SERPING1 belonging to the superfamily of serine proteinase inhibitors, which encodes protein C1 inhibitor (C1INH), in the testis-associated network. SERPING1 was selected as one of the gene targets for analysis in this study since C1INH plays a critical role in stopping the activity of the first component of the complement (C1). Inhibition of C1 prevents the activation of complement components 2 and 4 (C2 and C4) as well as a number of downstream effects on the complement cascade50. Once SARS-CoV-2 infects human host, the complement system is promptly activated in order to restrain the infection. However, as observed for other pathogens, complement activation can be eluded and the infection takes over. The role of the complement system in the SARS-CoV-2 infection can be a double-edged sword. COVID-19 recurrently exhibits a hyper-coagulable inflammatory condition, presenting high levels of inflammatory cytokines, D-dimers51, fibrinogen52 and mild thrombocytopenia53. Post-mortem pathology studies report a high incidence of venous thromboembolism54 and micro vascular thrombi55 in the lungs and kidneys with endothelial swelling, consistent with a thrombotic microangiopathy. In parallel, robust complement activation has been observed in endothelial cells56. The complement and coagulation systems exhibit cross-talk, moreover, some evidence describes a link between the activation of the complement system and thrombosis in COVID-19 patients. In the course of the Sars-CoV2 infection, the complement system can be activated via multiple pathways by the virus itself and by damaged tissues. The generation of C5a, whose levels are highly elevated in symptomatic COVID-19 patients (in combination with a strong expression of C5aR in monocytes and neutrophils), increases tissue factor activity both in circulation57 and on endothelial cells58. The induction of endothelial P-selectin by C5a59 is essential for the enrollment and aggregation of platelets. C5a induces a large production of neutrophil extracellular traps (NET)60, which capture platelets causing platelet aggregation, coagulation and thrombus formation. Patients with severe COVID-19 display elevated serum markers of neutrophil activation and NET formation61. Endothelial cells are stimulated by MAC to produce von Willebrand factor62, which increases prothrombinase activity resulting in fibrin deposition and endothelial injury. It has been shown that MASP-1 and MASP-2 cleave prothrombin58 and activate fibrinogen and factor XIII63. A strong deposition of C4d, MASP-2 and MAC has been found in the lung and in the dermal microvasculature from COVID-19 patients with acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS)64. The interaction between the complement and coagulation systems could promote a inflammatory thrombotic state in COVID-19 patients. Although complement activation is decisive to control infection in asymptomatic or mild cases, intensified activation can produce exacerbations of the disease promoting cytokine storm, tissue damage, thromboembolism and other clinical manifestations of pathological coagulation such as disseminated intravascular coagulation (DIC) seen in patients with severe COVID-1965. C1INH acts in the control of the kinin-bradykinin system, coagulation and thrombolysis. It prevents several other serine proteinases including plasmin, kallikrein, and coagulation factors XIa and XIIa66. Overall, these evidence clearly indicate that the expression of SERPING1 in the testis should have a protective role for thrombotic risk. However, the epidemiological data on gender differential outcomes are against this notion. To explain the increased propensity of thrombosis in men it can be assumed that SARS-CoV2 proteases may have the capability to cleave the N-terminal region of SERPING1. The removal of carbohydrate moieties has perhaps no consequences on the SERPING1 role on kallikrein inhibition67, however, it may inhibit the complex formation with C1s/C1r proteases and the successive clearance of SERPING1-C1s/C1r complexes by rLDL related protein. The deletion of these sites from the SERPING1 molecule may neutralize its function and increase the inflammatory process. Another suggestion that might support the hypothesis on the possible interaction between the proteases of COVID19 and SERPING1 is that patients with SARS-Cov2 could express high cleaved C1INH, such as that was found in the serum of a patient with HIV-168. Indeed, it has been reported that C1-INH is an interactor of 7 different CoV1 proteins and polypeptides, encoded by ORF3b, ORF7b, ORF14, nsp2ab, nsp13ab, nsp14ab and nsp8ab. These CoV1 proteins are comparable to their homologous CoV2 proteins69. C1INH degradation by plasmin may constitute a serious event in the defeat of protease inhibition during inflammation70 through lowering fibrinolysis and increasing thrombus formation. C1-INH is one of the proteins with the highest connectivity in the merged CoV2 interactomes. The interaction of several CoV2 proteins with C1INH showed that it can be repressed during viral infection, leading to a predisposition to trigger the complement cascade, the bradykinin pathway and the intrinsic coagulation cascade71. An impaired SERPING1 expression caused by CoV2 interacting proteins could stimulate the intrinsic coagulation pathway, inducing a pro-coagulant state that can overcome physiological anticoagulant activities (Fig. 3).

In agreement with the observation that host cell resistances to viral infections are based on chemokine and cytokine signals, the testis-related network analysis showed the implication of CCR5. It is a receptor for several CC chemokines that regulate leukocyte migration and activation. In the immune system, CCR5 is mainly expressed on CD4 + effector and memory T cells, natural killer T (NKT) cells, Th17, and macrophages, immature dendritic cells (DCs) and in bone marrow precursor cells during hematopoiesis72. CCR5 may promote inflammation in a wide range of infectious diseases by recruiting leukocytes towards inflammation sites73. In detail, CCR5 is more greatly expressed on interferon-γ (IFNγ)–secreting type 1 (Th1) cells than interleukin 4 (IL-4)–producing type 2 (Th2) cells74. CCR5 is involved in the pathology of SARS-CoV-269. SARS-CoV-2 has a capacity to enter to the cells rapidly. Therefore, in SARS-CoV-2 infection the function of the CD8 T cells that are cleaning the infected cells is very critical. From birth to old age higher numbers of CD4 + T cells and CD4/CD8 T cell ratios are present in females24 Pathologically overproduced chemokines and their own receptors have been found in patients with COVID-19. These different chemotactic receptor expression profiles observed on Th1 and Th2 cells seem to be critical for regulating their migratory inclinations to various sites of inflammation and effect cell-mediated immune responses crucial for the control of the COVID-19 infection. SARS-CoV-2 infected lungs displayed an upregulation of chemotactic factors, including CCL4, CCL8, and CCL11, which all shared CCR5 as their receptor. CCL4 exhibits chemoattractive capacity towards different cell types such as immune cells, and coronary endothelial cells75. CCL5 and its receptor CCR5 are significantly induced in the infarcted myocardium and are associated with a higher risk of stroke and cardiovascular events75. Moreover, CCR5 and CCL5 play important roles in respiratory infections and inflammatory response, which frequently requires the recruitment of immune cells such as activated NK, CD8+ T cells and macrophages76 to remove infectious agents. Differential expression of chemokine receptors and ligands may modulate inflammatory patterns, which in turn may influence the establishment or progression of infections. Nevertheless, an intense increment of plasmatic levels of IL-6 and CCL5 (also known as RANTES), a ligand for CCR5, decreased CD8 + T cell levels, and SARS-CoV-2 plasma viremia in severe COVID-19 patients77. An improved chemotaxis created by unregulated CCL5 and cytokines, such as IL-6 and TNF-α, induces an inflammatory cascade leading to ARDS and multisystem organ failure76.

BST2, GATA1, ENPEP, TLR4, TLR7, IRF1, and IRF2 in the ovary network

In our analysis the bone marrow stromal antigen 2 (BST2; also known as CD317 or tetherin) was found in the ovary-related network. BST2 is a virus restriction factor that has been recognized to be a powerful inhibitor of SARS-CoV-2 replication77. BST2 is circumscribed at the plasma membrane and in endosomes and acts through the ER and Golgi complex. It prevents viral release of numerous enveloped viruses, including human coronavirus and SARS-CoV-1, which bud at the plasma membrane or the ER and Golgi complex by tethering their virions to the cell surface or intracellular membranes78. BST2 prevents viral egress and antagonize the protein accessory SARS-Cov-2 Orf7a for virion release, hence, is responsible for tethering nascent enveloped SARS-CoV-2 virions to infected cell surfaces79. The transmembrane tetherin protein is expressed in bone marrow stromal cells, B-cells, dendritic cells, and other cell types79 and is found predominantly in the cholesterol-rich domains (lipid rafts) of the plasma membrane78. BST-2 is robustly induced on the surface of many types of cells after exposure to IFN through the IRF180 and other proinflammatory cytokines via STAT activation81,82. As a result, BST-2 prevents the release of formed viral particles inside the cell avoiding their spread. IRF1 controls constitutive antiviral gene networks to counterattack viral infections in human respiratory epithelial cells, by regulating early expression of IFNs80. Moreover, it stimulates constitutive expression of the anti-viral genes such as BST2, OAS2, and RNASEL, to preserve an excellent anti-viral state. Specifically, BST2 expression is modulated by the TLR4/PI3K signaling pathway. Activation of TLR4 generates the TRIF/IRF3-mediated positive regulation of BST-2 whereas MYD88/PI3K exerts a negative regulation83. Among the TLR family, TLR3, TLR7, TLR8 and TLR9 are principally localized in intracellular compartments and are specialist in identifying and counteracting viral infections84. TLR9 identifies RNA and DNA motifs enriched in unmethylated Cytosine-phosphate-Guanine (CpG) sequences, which are expressed in the bacterial and viral genome85. Human mitochondrial DNA (mtDNA), evolutionarily derived from endosymbiont bacteria, contains unmethylated CpG-motifs and is a model of a well-known DAMP that initiates inflammatory process directly via TLR9 in the course of injury and infection86. mtDNA, formed from damaged host cells, also modifies self-ligands, called carboxy-alkyl-pyrrole protein adducts (CAPs), which are formed during oxidative stress, contribute to intensify TLR9/MyD88 pathway activation infection86. CAPs promote platelet activation, granule secretion, and aggregation in vitro and thrombosis in vivo87. Since circulating mtDNA levels rise with old age they are a familiar feature contributing to chronic inflammation in elderly (termed “inflamm-aging”)88. In the context of COVID-19, this TLR9 axis of inflamm-aging could have consequence, just because older age is associated with high risk of developing severe complications of COVID-19. In the course of COVID-19, TLRs are essential in the viral battle. Specifically, as regards the role of TLR9 in resistance against SARS-CoV-2 it has been proposed that there is an excessive TLR9 activation in severe COVID-19 pathology. TLR9 is largely expressed in different cell types including epithelial cells in the lungs and nasal mucosa, in muscles and brain, on plasmacytoid dendritic cells and B cells, monocytes, macrophages, neutrophils, T lymphocytes, NK cells, megakaryocytes and platelets89. Regarding TLR9 COVID-19 theory suggests that in particular susceptible patients, the activation of TLR9 could be a soft but powerful force inducing hyperinflammation and thrombotic complications seen in SARS-CoV-2. Hence, the efficacy of TLR9 agonists in defense against SARS-CoV-2 is advisable90. BST2 expression is regulated by inflammatory signals and its stimulatory receptors may control immune functions by interacting with inducible or pathogen-associated ligands. It has been proposed that endocytosis-competent Tetherin may induce the intracellular uptake of virions into endosomes blocking viral release91. TLR9 is located in endosomes. Through the TLR9/MyD88 pathway, can be activated in various cell types such as Th1 and Th17 lymphocytes, B cells, dendritic cells, neutrophils and platelets inducing various inflammatory mediators such as type 1 IFNs, TNFa, IL-6, IL-8, IL-10, and IL-1787 (Fig. 3). All these cell types and intermediaries promotes the cytokine storm and thrombotic complications observed in the multi-organ failure in patients with severe COVID19 infections92. It has been proved that BST2 promotes NK cell, CD4 + T cell and CD8 + T cell response93. Moreover, BST2 modulate IFN responses of human pDC through ILT794. These vigorous cell-mediated immune responses associated with lower infection levels indicate that tethering-mediated retrovirus control activities by modulating adaptive immunity. Tetherin acts on different phases of cell-mediated immunity, but depend on antigen presenting cells for activation. Tetherin + DCs are more vigorously stimulated virus-specific CD4 + T cells compared to Tetherin KO DCs ex vivo even though similar virus infection levels. Tethering-mediated virion aggregation on the cell surface can be a mechanism required to increase NK cell-mediated killing95. Internalization of tethered virions could stimulate viral sensing by endosomal sensors and successive upregulation of cytokines essential for NK cell function such as IL15. Thus, it is coinceivable that specific health conditions of the host tetherin-mediated virion endocytosis may control TLR9 recognition to restrain immune cell responses. This may induce production of cytokines such as type I IFN and IL15, which can both trigger NK cell responses. In mice, Tetherin enhances type I IFN expression in plasmacytoid dendritic cells (pDC), after stimulation with virus in vitro96. The pDC repertoire of PRRs is very specialized and includes mainly TLR7 and TLR9. Endosomes of pDCs trigger TLR9-mediated induction of type 1 IFN responses97. As a result of their higher type I IFN production and nucleic acid-oriented sensing of pathogens through endosomal TLRs, pDCs exhibit vast antiviral functions and are slightly tolerant to viral infections compared to cDCs98. Since that BST2 serves as a physiological ligand for the human pDC-specific receptor ILT7 it may act as a critical link between type I interferons and pDC responses in retrovirus infections. Human pDCs express both inhibitory receptors and stimulatory receptors99. pDC receptors ILT7, BDCA2, high-affinity Fc receptor for IgE, and NKp44 have negative effects on the IFN response of pDC to TLR activation through the ITAM-mediated pathway94. Intracellular TLRs have a partial aptitude to identify host versus foreign nucleic acids100. Numerous host factors, including antimicrobial peptide LL37, anti-DNA antibodies or the nuclear DNA-binding protein HMGB1, alone or in combination, promote entry of self-DNA into the endosomes of pDCs, where they activate TLR9 to induce type 1 IFN responses97. In the same way, autoantibody small nuclear ribonucleoprotein complexes can trigger TLR7 via FcγRII to induce IFN101. BST2 is the first non–MHC class I–type ligand for a member of the ILT receptor family102. pDCs are involved in antiviral innate immune responses by secreting large quantities of IFN-α/β. Nevertheless, type 1 IFN responses immediately after viral infection are short lived. Since BST2 is induced on the surface of many types of cells after exposure to IFN and via STAT activation81, BST2–ILT7 interaction may act as an indispensable negative feedback mechanism for avoiding sustained IFN synthesis after viral infection. Experimental evidence demonstrated that BST2 expression significatively decreased SARS-CoV-2 RNA replication (53% less than control cells) followed by a more effective decline (74%) of viral release92. Additional studies should further explain the role of BST2 in affecting viral pathogenesis and host cell-mediated immune responses.

At first GATA1 was recognized as a trans-acting factor of globin and other erythroid-specific genes. GATA-1 is expressed in CD34 + hematopoietic stem cells (HSCs), erythroblasts, megakaryocytes, and mast cells, basophils and eosinophils, regulating megakaryopoiesis and erythropoiesis103. It is well known the solid link between the GATA-binding protein members and T-cell differentiation. GATA-1 trans-activates CCR5 promoter activity in a transformed T-lymphoid cell line98. CCR5 includes DNA binding sites for GATA TFs104. GATA-1 decreases CCR5 promoter activity and hence is a powerful repressor of CCR5 expression at both protein and transcript levels in human T-cell subsets and DCs104. The suppression of CCR5 in human T cells by GATA-1 further confirm the idea that GATA-1 acts as an efficent and selective transcriptional repressor. Ectopic expression of GATA-1 prevents the expression of CCR5 and other Th1 effector molecules such as IFN-γ and CXCR3 and anti-inflammatory cytokines IL-4, IL-5, IL-13 and chemotactic receptors such as CCR4 and CRTH2105. The non-conserved trans-activation domains of GATA-1 have the function of supplementary protein interaction interfaces106, which could let it to selectively engage repressive cofactors to the IFNγ and CXCR3 promoters. The observation that GATA-1-responsive loci are epigenetically changed during hematopoiesis indicates that, in turn, GATA-1 may epigenetically modify the CCR5 promoter. The result that GATA-1 inhibits effectively CCR5 expression in numerous human cell types 107, strongly suggests that GATA-1 exerts the same repressor function in SARS-COV-2 target cells (Fig. 3). Therefore, GATA-1, which is expressed in HSCs and is silenced during their differentiation to CCR5-expressing DCs107, could influence COVID-19 susceptibility of these cell types during hematopoiesis, as well as mast-cell progenitors, which are all potential targets of viral infection in vivo108. A deeper understanding of the mechanism by which GATA-1 represses CCR5 expression can help unravel the genetic regulation of CCR5 in the target cells of COVID-19 and may be valuable in devising new approaches to antagonize CCR5 in individuals with COVID-19 infection. These observations increase the opportunities to understand the mechanisms by which the GATA-1 intervenes in the suppression of CCR5 in order to identify the therapeutic strategy to make the host cells resistant to the infection of SARS-COV2. Blocking CCR5 should promote rapid decline of IL-6, re-establishment of the CD4/CD8 ratio, and a significant reduction in SARS-CoV-2 plasma viremia.

Conclusion

To date, various data have shown that SARS-CoV-2 needs ACE2 and TMPRSS2 expression for viral activity and that androgens increase ACE2 and TMPRSS2 gene expression, whereas, estrogens reduce ACE2 mRNA expression. Therefore, viral entry seems to be facilitated in man. Nevertheless, the immunomodulatory effects of sex hormones are insufficient to explain the gender difference in susceptibility, severity and mortality to COVID-19.

Our bioinformatic findings about the SARS-CoV-2 effects on gonads demonstrate, for the first time, that in female gonads the gene associated with the host immune response against COVID-19 viral infections are prevalent compared to those found in the male gonads (see supplemental material). In particular, the expression of BST-2 and GATA-1 and their networks strongly suggest that women have stronger cell-dependent and humoral responses to infection, resulting in a more rapid pathogen elimination in females than in males.

On the other hand, the expression of Serping1, observed in male gonads, could be a valuable protective factor against the onset of the cytokine storm. However, obviously, only this factor is not enough to counteract the adverse effects caused by the infection of COVID-19. Mainly genes that promote the susceptibility and strenghthen the severity of SARS-CoV-2 are expressed in male gonads (see supplemental material). Our studies encourage an urgent need to analyze the expression of these particular genes in promoting or suppressing viral load in SARSCoV-2 and the cytokine storm in infected experimental models. For example, it could be interesting to investigate the influence of genetic polymorphism relevant to identify the involvement of several genes especially Serping 1 or BST2 on the severity of COVID-19. Overall, this finding contributes to explain gender difference in susceptibility, severity and mortality to COVID-19 and provide potential diagnostic and therapeutic targets.

Supplementary Information

Acknowledgements

We wish to thank the Scientific Bureau of the University of Catania for language support.

Abbreviations

- ACE 2

Angiotensin-converting enzyme 2

- ADAM10

Disintegrin and metalloproteinase domain-containing protein 10

- ANPEP

Alanyl Aminopeptidase, Membrane

- AR

Androgen receptors

- BST2

Bone marrow stromal antigen 2

- CCL

Chemokine

- CCR5

Chemokine receptor-5

- C1INH

C1 inhibitor

- DPP4

Dipeptidyl peptidase-4

- ENPEP

Glutamyl Aminopeptidase

- ER

Estrogen receptors

- FOXP3

Forkhead box P3

- GATA-1

GATA Binding Protein 1

- HMGB1

High Mobility Group1

- IFN

Interferon

- IL-6

Interleukin-6

- IRF

Interferon Regulatory Factor

- ORF

OPEN READING FRAM

- TLR

Tolk like receptor

- TMPRSS2

Transmembrane Serine Protease 2

Author contributions

C.R. and G.M. equally contributed to this manuscript through data acquisition, performing all the analyses and the methodology. R.M., D.L.F. and S.P.: literature research, validation and revised the manuscript. L.M.: conceptualization, project administration, data interpretation, writing the manuscript and editing. All authors approved the submitted version.

Data availability

Publicly available datasets were analyzed in this study. These data can be found here: https://www.proteinatlas.org/humanproteome/sars-cov-2.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher's note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1038/s41598-021-01131-7.

References

- 1.Huang C, et al. Clinical features of patients infected with 2019 novel coronavirus in Wuhan, China. Lancet. 2020;395(10223):497–506. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30183-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Zhu N, et al. China Novel Coronavirus Investigating and Research Team. A novel coronavirus from patients with pneumonia in China, 2019. N. Engl. J. Med. 2020;382(8):727–733. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa2001017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.World Health Organization. Coronavirus Disease (COVID-19) Outbreak. https://www.who.int/emergencies/diseases/novel-coronavirus-2019/events-as-they-happen.

- 4.Guan WJ, Ni ZY, Hu Y. Clinical characteristics of coronavirus disease 2019 in China. N. Engl. J. Med. 2020;382(18):1708–1720. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa2002032. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kitajima, M. et al. SARS-CoV-2 in wastewater: State of the knowledge and research needs. Sci. Total Environ. 739, 139076 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 6.Saguti, F. et al. Surveillance of wastewater revealed peaks of SARS-CoV-2 preceding those of hospitalized patients with COVID-19. Water Res. 189, 116620. (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 7.Fajnzylber J, et al. SARS-CoV-2 viral load is associated with increased disease severity and mortality. Nat. Commun. 2020;11(1):5493. doi: 10.1038/s41467-020-19057-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Yan R, et al. Structural basis for the recognition of SARS-CoV-2 by full-length human ACE2. Science. 2020;367(6485):1444–1448. doi: 10.1126/science.abb2762. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Khan R, Naseem T, Hussain MJ, Hussain MA, Malik SS. Possible potential outcomes from COVID-19 complications on testes: Lesson from SARS infection. J. Coll. Physicians Surg. Pak. 2020;30(10):118–120. doi: 10.29271/jcpsp.2020.supp2.118. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Wang Z, Xu X. scRNA-seq profiling of human testes reveals the presence of the ACE2 receptor, a target for SARS-CoV-2 infection in spermatogonia Leydig and sertoli cells. Cells. 2020;9(4):920. doi: 10.3390/cells9040920. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Gurwitz D. Angiotensin receptor blockers as tentative SARS-CoV-2 therapeutics. Drug Dev. Res. 2020;81(5):537–540. doi: 10.1002/ddr.21656. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Dijkman R, et al. Replication-dependent downregulation of cellular angiotensin-converting enzyme 2 protein expression by human coronavirus NL63. J. Gen. Virol. 2012;93(Pt 9):1924–1929. doi: 10.1099/vir.0.043919-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hoffmann M, et al. SARS-CoV-2 cell entry depends on ACE2 and TMPRSS2 and is blocked by a clinically proven protease inhibitor. Cell. 2020;181(2):271–280.e8. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2020.02.052. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Qi F, Qian S, Zhang S, Zhang Z. Single cell RNA sequencing of 13 human tissues identify cell types and receptors of human coronaviruses. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2020;526(1):135–140. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2020.03.044. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Holmes RS, Spradling-Reeves KD, Cox LA. Mammalian glutamyl aminopeptidase genes (ENPEP) and proteins: Comparative studies of a major contributor to arterial hypertension. J. Data Min. Genom. Proteom. 2017;8(2):2. doi: 10.4172/2153-0602.1000211. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Seyran M, et al. The structural basis of accelerated host cell entry by SARS-CoV-2. FEBS J. 2021;288(17):5010–5020. doi: 10.1111/febs.15651. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.McNab F, Mayer-Barber K, Sher A, Wack A, O'Garra A. Type I interferons in infectious disease. Nat. Rev.. Immunol. 2015;15(2):87–103. doi: 10.1038/nri3787. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hansen TH, Bouvier M. MHC class I antigen presentation: Learning from viral evasion strategies. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 2009;9(7):503–513. doi: 10.1038/nri2575. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Castagnoli R, et al. Severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) infection in children and adolescents: A systematic review. JAMA Pediatr. 2020;174(9):882–889. doi: 10.1001/jamapediatrics.2020.1467. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Jin JM, et al. Gender differences in patients with COVID-19: Focus on severity and mortality. Front. Public Health. 2020;8:152. doi: 10.3389/fpubh.2020.00152. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Dutta S, Sengupta P. SARS-CoV-2 and male infertility: Possible multifaceted pathology. Reprod. Sci. 2021;28(1):23–26. doi: 10.1007/s43032-020-00261-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Espinosa, O. A. et al. Prevalence of comorbidities in patients and mortality cases affected by SARS-CoV2: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Rev. Inst. Med. Trop. Sao Paulo. 62, e43 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 23.Global Health 50/50. The Sex, Gender and Covid-19 Project. 2020 [cited 3 Oct 2020]. https://globalhealth5050.org/covid19

- 24.Klein SL, Flanagan KL. Sex differences in immune responses. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 2016;16(10):626–638. doi: 10.1038/nri.2016.90. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Takahashi T, et al. Sex differences in immune responses that underlie COVID-19 disease outcomes. Nature. 2020;588(7837):315–320. doi: 10.1038/s41586-020-2700-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Goren A, et al. A preliminary observation: Male pattern hair loss among hospitalized COVID-19 patients in Spain: A potential clue to the role of androgens in COVID-19 severity. J. Cosmet. Dermatol. 2020;19(7):1545–1547. doi: 10.1111/jocd.13443. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Franz M, et al. GeneMANIA update 2018. Nucleic Acids Res. 2018;46(W1):W60–W64. doi: 10.1093/nar/gky311. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Shannon P, et al. Cytoscape: A software environment for integrated models of biomolecular interaction networks. Genome Res. 2003;13(11):2498–2504. doi: 10.1101/gr.1239303. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Maere S, Heymans K, Kuiper M. BiNGO: A Cytoscape plugin to assess overrepresentation of gene ontology categories in biological networks. Bioinformatics. 2005;21(16):3448–3449. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/bti551. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Qiu Y, et al. Predicting the angiotensin converting enzyme 2 (ACE2) utilizing capability as the receptor of SARS-CoV-2. Microbes Infect. 2020;22(4–5):221–225. doi: 10.1016/j.micinf.2020.03.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kyrou I, et al. Polycystic ovary syndrome (PCOS) and COVID-19: An overlooked female patient population at potentially higher risk during the COVID-19 pandemic. BMC Med. 2020;18(1):220. doi: 10.1186/s12916-020-01697-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Stopsack KH, Mucci LA, Antonarakis ES, Nelson PS, Kantoff PW. TMPRSS2 and COVID-19: Serendipity or opportunity for intervention? Cancer Discov. 2020;10(6):779–782. doi: 10.1158/2159-8290.CD-20-0451. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Dalpiaz, P. L. et al. Sex hormones promote opposite effects on ACE and ACE2 activity, hypertrophy and cardiac contractility in spontaneously hypertensive rats. PLoS ONE. 10(5), e0127515 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 34.Roberts, A. et al. A mouse-adapted SARS-coronavirus causes disease and mortality in BALB/c mice. PLoS Pathog.3(1), e5 (2007). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 35.Channappanavar R, et al. Sex-based differences in susceptibility to severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus infection. J. Immunol. 2017;198(10):4046–4053. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1601896. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Fantozzi ET, et al. Estradiol mediates the long-lasting lung inflammation induced by intestinal ischemia and reperfusion. J. Surg. Res. 2018;221:1–7. doi: 10.1016/j.jss.2017.07.038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Stelzig KE, et al. Estrogen regulates the expression of SARS-CoV-2 receptor ACE2 in differentiated airway epithelial cells. Am. J. Physiol. Lung Cell Mol. Physiol. 2020;318(6):L1280–L1281. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.00153.2020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Stilhano RS, et al. SARS-CoV-2 and the possible connection to ERs, ACE2, and RAGE: Focus on susceptibility factors. FASEB J. 2020;34(11):14103–14119. doi: 10.1096/fj.202001394RR. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Cure E, Cumhur Cure M. Angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors and angiotensin receptor blockers may be harmful in patients with diabetes during COVID-19 pandemic. Diabetes Metab. Syndr. 2020;14(4):349–350. doi: 10.1016/j.dsx.2020.04.019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Suba Z. Prevention and therapy of COVID-19 via exogenous estrogen treatment for both male and female patients. J. Pharm. Pharm. Sci. 2020;23(1):75–85. doi: 10.18433/jpps31069. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Edwards DR, Handsley MM, Pennington CJ. The ADAM metalloproteinases. Mol. Aspects Med. 2008;29(5):258–289. doi: 10.1016/j.mam.2008.08.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Sharma K, et al. Cell type- and brain region-resolved mouse brain proteome. Nat. Neurosci. 2015;18(12):1819–1831. doi: 10.1038/nn.4160. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Lundgren JL, et al. ADAM10 and BACE1 are localized to synaptic vesicles. J. Neurochem. 2015;135(3):606–615. doi: 10.1111/jnc.13287. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Gunner G, et al. Sensory lesioning induces microglial synapse elimination via ADAM10 and fractalkine signaling. Nat Neurosci. 2019;22(7):1075–1088. doi: 10.1038/s41593-019-0419-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Dempsey, P. J. Role of ADAM10 in intestinal crypt homeostasis and tumorigenesis. Biochim. Biophys. Acta1864(11 Pt B), 2228–2239 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 46.Ahmed, I. et al. Enteric infection coupled with chronic Notch pathway inhibition alters colonic mucus composition leading to dysbiosis, barrier disruption and colitis. PLoS ONE13(11), e0206701 (2018) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 47.Maretzky T, et al. ADAM10 mediates E-cadherin shedding and regulates epithelial cell-cell adhesion, migration, and beta-catenin translocation. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2005;102(26):9182–9187. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0500918102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Liang SJ, Li XG, Wang XQ. Notch signaling in mammalian intestinal stem cells: Determining cell fate and maintaining homeostasis. Curr. Stem Cell Res. Ther. 2019;14(7):583–590. doi: 10.2174/1574888X14666190429143734. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Jia HP, et al. Ectodomain shedding of angiotensin converting enzyme 2 in human airway epithelia. Am. J. Physiol. 2009;297(1):L84–96. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.00071.2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Germenis AE, Speletas M. Genetics of hereditary angioedema revisited. Clin. Rev. Allergy Immunol. 2016;51(2):170–182. doi: 10.1007/s12016-016-8543-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Demelo-Rodríguez P, et al. Incidence of asymptomatic deep vein thrombosis in patients with COVID-19 pneumonia and elevated D-dimer levels. Thromb. Res. 2020;192:23–26. doi: 10.1016/j.thromres.2020.05.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Panigada M, et al. Hypercoagulability of COVID-19 patients in intensive care unit: A report of thromboelastography findings and other parameters of hemostasis. J. Thromb. Haemost. 2020;18(7):1738–1742. doi: 10.1111/jth.14850. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Lippi G, Sanchis-Gomar F, Henry BM. Coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19): The portrait of a perfect storm. Ann. Transl. Med. 2020;8(7):497. doi: 10.21037/atm.2020.03.157. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Tang N, Li D, Wang X, Sun Z. Abnormal coagulation parameters are associated with poor prognosis in patients with novel coronavirus pneumonia. J. Thromb. Haemost. 2020;18(4):844–847. doi: 10.1111/jth.14768. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Wang T, et al. Attention should be paid to venous thromboembolism prophylaxis in the management of COVID-19. Lancet Haematol. 2020;7(5):e362–e363. doi: 10.1016/S2352-3026(20)30109-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Magro C, et al. Complement associated microvascular injury and thrombosis in the pathogenesis of severe COVID-19 infection: A report of five cases. Transl. Res. 2020;220:1–13. doi: 10.1016/j.trsl.2020.04.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Ritis K, et al. A novel C5a receptor-tissue factor cross-talk in neutrophils links innate immunity to coagulation pathways. J. Immunol. 2006;177(7):4794–4802. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.177.7.4794. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Ikeda K, et al. C5a induces tissue factor activity on endothelial cells. Thromb. Haemost. 1997;77(2):394–398. doi: 10.1055/s-0038-1655974. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Del Conde I, Crúz MA, Zhang H, López JA, Afshar-Kharghan V. Platelet activation leads to activation and propagation of the complement system. J. Exp. Med. 2005;201(6):871–879. doi: 10.1084/jem.20041497. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Guo RF, Ward PA. Role of C5a in inflammatory responses. Annu. Rev. Immunol. 2005;23:821–852. doi: 10.1146/annurev.immunol.23.021704.115835. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Zuo, Y. et al. Neutrophil extracellular traps in COVID-19. JCI Insight5(11), e138999 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]