Abstract

The social amoeba Dictyostelium discoideum is a model organism that is used to investigate many cellular processes including chemotaxis, cell motility, cell differentiation, and human disease pathogenesis. While many single-cellular model systems lack homologs of human disease genes, Dictyostelium’s genome encodes for many genes that are implicated in human diseases including neurodegenerative diseases. Due to its short doubling time along with the powerful genetic tools that enable rapid genetic screening, and the ease of creating knockout cell lines, Dictyostelium is an attractive model organism for both interrogating the normal function of genes implicated in neurodegeneration and for determining pathogenic mechanisms that cause disease. Here we review the literature involving the use of Dictyostelium to interrogate genes implicated in neurodegeneration and highlight key questions that can be addressed using Dictyostelium as a model organism.

Keywords: Dictyostelium discoideum, neurodegeneration, model organism, polyglutamine (polyQ) diseases, Alzheimer’s disease, Parkinson’s disease

Introduction – Model Organisms for Neurodegenerative Diseases

As the human population ages, neurodegenerative diseases are becoming increasingly prevalent. Neurodegenerative diseases are characterized by neuronal dysfunction and degeneration. This dysfunction and degeneration can be caused by both sporadic and genetic causes, affect different subsets of neurons, and have varied pathological hallmarks. Neurodegenerative disease progression inevitably leads to disability and death, and for nearly all these diseases there is a lack of curative treatments. Therefore, understanding the molecular mechanisms that drive neurodegenerative diseases is important for developing therapies.

One way to investigate the mechanisms that drive neurodegenerative diseases is by utilizing model organisms. Neurodegenerative diseases have been studied in a wide variety of model systems ranging from yeast to non-human primates. Model organisms like yeast, worms, flies, and zebrafish can be utilized to investigate the basic pathology of neurodegenerative diseases and are useful models that are inexpensive and easy to genetically manipulate (Miller-Fleming et al., 2008; van Ham et al., 2009; Gama Sosa et al., 2012; Andrews et al., 2016; Suresh et al., 2018). These models are advantageous for determining basic pathophysiological mechanisms, but lack key aspects of the higher eukaryotes that can affect disease pathogenesis such as myelination of neurons and immune function; this means that they do not fully recapitulate human diseases (Gama Sosa et al., 2012). Other models include mammalian cell culture including primary neuronal cultures and induced pluripotent stem cell (iPSC)-derived neuronal cultures. Primary neuronal cultures and iPSCs are advantageous because they are more similar to the human brain than non-mammalian models (Lopes et al., 2017; Slanzi et al., 2020). However, these models do have some drawbacks including the fact they are more fetal-like in nature, and thus may not be an ideal model for age-related neurodegenerative diseases (Kumar et al., 2018; Slanzi et al., 2020). More complex model organisms, like rodents and non-human primates, have more similar neuroanatomy and neurophysiology to the human brain, and phenotypes associated with various neurodegenerative diseases can be recapitulated in these models (Emborg, 2017; Dawson et al., 2018; Suresh et al., 2018). In addition, more complex models show disease progression with aging, which is harder to observe in simpler systems with shorter life spans (Emborg, 2017; Dawson et al., 2018). Rodent and primate models are also essential for testing the feasibility and safety of therapeutics prior to clinical trials (Emborg, 2017; Dawson et al., 2018; Suresh et al., 2018). Therefore, each model organism has strengths and weaknesses that must be taken into consideration when investigating neurodegenerative diseases.

One major unanswered question for many neurodegenerative diseases is: What is the normal function of the proteins that cause disease? This is an important question because one possibility is that neurodegenerative diseases are caused by either a loss of or a toxic gain of protein function. One way to delineate the normal function of proteins that cause neurodegenerative diseases is through utilizing non-mammalian model systems. Many non-mammalian model systems have numerous benefits including simpler genomes, decreased genetic redundancy, ease of genetic manipulation, shorter generation times, and scalability for high throughput genetic and pharmacological studies (van Ham et al., 2009; Gama Sosa et al., 2012; Bozarro, 2013; Suresh et al., 2018). These advantages allow for more rapid investigation into mechanisms that cause neurodegeneration that cannot be accomplished as easily in mammalian model systems.

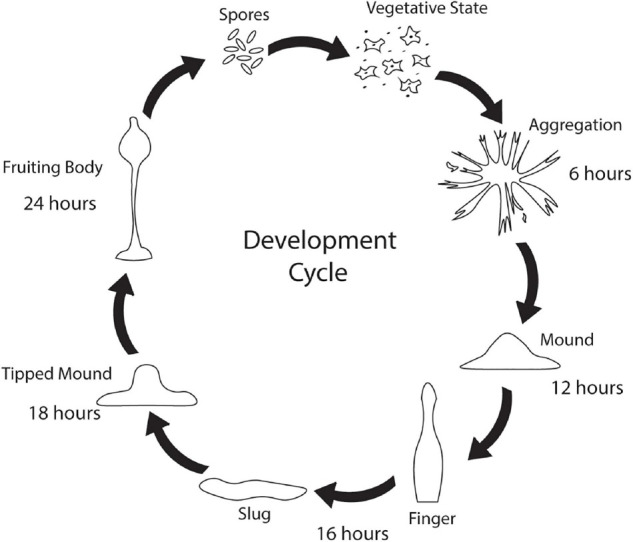

While Saccharomyces cerevisiae, Caenorhabditis elegans, and Drosophila melanogaster are popular non-mammalian systems for neurodegenerative disease research, Dictyostelium discoideum (Dictyostelium) is another simple organism that is useful as a model to investigate mechanisms that cause disease. Dictyostelium is a soil-dwelling amoeba found throughout the world. Dictyostelium consumes bacteria, however, when bacteria are depleted, Dictyostelium undergoes a developmental cycle transitioning from a unicellular amoeba to a multicellular fruiting body (Figure 1). This developmental process makes Dictyostelium an ideal model organism for investigating numerous biological processes including chemotaxis, cell differentiation, and tissue formation. In addition to these cellular processes, Dictyostelium is also a useful model of human diseases, including neurodegenerative diseases. Surprisingly, despite the lack of a nervous system, Dictyostelium’s genome encodes a number of genes that cause neurodegenerative diseases (Table 1). This is a substantial increase in genes that cause neurodegeneration compared to S. cerevisiae, another single-celled organism commonly utilized for genetic screening and elucidation of gene function (Table 2). This makes Dictyostelium a good model organism for identifying the normal function of genes that cause neurodegeneration and for identifying how mutations in these genes may disrupt function.

FIGURE 1.

Dictyostelium’s developmental cycle. Under stress conditions such as starvation, unicellular Dictyostelium emits a cAMP signal causing individual cells to culminate, forming aggregates after 6 h. After 12 h, the aggregates begin to form mounds which turn into finger/slug structures around 16 h. The slug carries the Dictyostelium cells to the top of the forest floor where it forms a tipped mound around 18 h. After 24 h, a fruiting body consisting of a spore filled sorus is hoisted by a stalk. Fruiting bodies are then carried off by wildlife and can germinate and propagate elsewhere.

TABLE 1.

Human neurodegenerative disease proteins and their Dictyostelium homologs.

| Human Protein | Dictyostelium Protein | Neurodegenerative disease | Human Protein | Dictyostelium Protein | Neurodegenerative disease |

| PSEN1 | Q54DE8 | Alzheimer’s disease | HTT | Q76P42 | Huntington’s disease |

| PSEN2 | Q54ET2 | ||||

| ABCA7 | Q8T6J5 | CLN1 | Q54N35 | Neuronal ceroid lipofucinosis/batten disease | |

| PLD3 | Q54SA1 | CLN2 | Q55CT0 | ||

| CD2AP | Q54F41 | CLN3 | Q54F25 | ||

| BIN1 | Q54IA6/Q54NT2 | CLN4 | Q54GP6/Q86KX9 | ||

| INPP5D | Q54W40 | CLN5 | Q553W9 | ||

| CELF1 | Q54EJ3 | CLN7 | Q8T2G9 | ||

| PFK | P90521 | CLN10 | O76856 | ||

| PK | Q54RF5 | ||||

| CLU | O15818 | SACS | Q55EK5/Q55EK4/Q55EK6 | ARSACS | |

| UCHL1 DJ-1 | Q54T48 Q54MG7 | Parkinson’s disease | PEX1 PEX3 | Q54GX5 Q54U86 | Infantile refsum disease |

| ATP13A2 | Q54NW5/Q54 × 63 | PEX6 PEX12 | Q54CS8 Q54N40 | ||

| GIGYF2 | Q54WZ1 | PHYH | Q54BP2 | Refsum disease | |

| VPS35 | Q54C24 | ||||

| EIF4G1 | Q553R3 | PEX7 | Q54WA3 | ||

| PGK1 | Q9GPM4 | ||||

| VPS13C GCH1 | Q55FG3 Q94465 | VPS13a | Q54LB8/Q555C6 | Chorea-acanthocytosis | |

| SOD1 | Q54G70 | Amyotrophic lateral sclerosis | SMPCD1 | Q54C16 | Niemann-Pick disease |

| UBQLN2 | Q9NIF3 | NPC1 | Q551C5/Q9TVK6 | ||

| KIF5A | Q54UC9 | ||||

| CHCHD10 | Q54BU1 | TSEN2 | Q54RX5 | Pontocerebellar hypoplasia | |

| TUBA4A | P32255 | TSEN34 | Q556W4 | ||

| ANXA11 | P24639 | TSEN54 | Q54ND7 | ||

| PGK1 | Q9GPM4 | RARS2 | Q558Z0 | ||

| ATXN2 | Q55DE7 | Spinocerebellar ataxia | PDHA1 | Q54C70 | Pyruvate dehydrogenase deficiency |

| SPTBN2 | Q54DR3 | DLAT | P36413 | ||

| ATXN10 | Q55EI6 | PDHB | Q86HX0 | ||

| PPP2R2B | Q54Q99 | ||||

| ITPR1 | Q9NA13 | HEXB | P13723/Q54SC9 | Sandoff disease | |

| TBP | P26355 | ||||

| EEF2 | P151122/Q54JV1 | HEXA | P13723/Q54SC9 | Tay-Sachs disease | |

| AFGL2 | Q75JS8 | ||||

| ELOVL4 | Q55BY4 | ERCC6 | Q54TY2 | Cockayne syndrome | |

| NOP56 | Q54MT2 | ||||

| AT2B1 | P54678/Q54HG6 | ABCA1 | Q8T5Z7 | Tangier’s disease | |

| VPS13D | Q55FG3 | ||||

| SCYL1 | Q55GS2 | FXN | Q54C45 | Friedreich’s ataxia |

TABLE 2.

Comparison of neurodegenerative disease genes present in Dictyostelium versus S. cerevisiae.

| Neurodegenerative disease | Gene Present in Dictyostelium | Present in S. cerevisiae | Neurodegenerative Disease | Gene Present in Dictyostelium | Present in S. cerevisiae |

| Alzheimer’s disease | ABCA7 | + | ARSACS | SACS | − |

| PLD3 | − | ||||

| PSEN1 | − | Neuronal ceroid lipofucinoses (Batten diseases) | CLN1 | − | |

| PSEN2 | − | TPP (CLN2) | − | ||

| CD2AP | − | CLN3 | + | ||

| BIN1 | − | CLN4 | − | ||

| INPP5D | − | CLN5 | − | ||

| CELF1 | + | CLN7 | − | ||

| CLN10 | + | ||||

| Parkinson’s disease | UCHL1 | + | Infantile osteopetrosis | CLCN7 | − |

| DJ-1 | − | ||||

| ATP13A2 | + | ||||

| GIGYF2 | + | Infantile refsum disease | PEX1 | − | |

| VPS35 | + | PEX3 | + | ||

| EIF4G1 | − | PEX6 | + | ||

| PEX12 | + | ||||

| Amyotrophic lateral sclerosis | SOD1 | + | |||

| KIF5A | − | PHYH | − | ||

| CHCHD10 | + | ||||

| TUBA4A | + | Chorea acanthocytosis | VPS13a | + | |

| ANXA11 | − | Niemann Pick diseases | SMPD1 | − | |

| Huntington’s disease | HTT | − | NPC1 | + | |

| Spinocerebellar ataxia | ATXN2 | − | Pontocerebellar hypoplasia | TSEN2 | − |

| ATXN10 | − | TSEN34 | + | ||

| TBP | + | TSEN54 | − | ||

| PPP2R2B | + | RARS2 | + | ||

| ITPR1 | − | ||||

| AFG3L2 | + | Pyruvate dehydrogenase deficiency | PDHA1 | + | |

| ELOVL4 | + | PDHB | + | ||

| NOP56 | + | DLAT | + | ||

| Spinocerebellar ataxia, X-linked | AT2B1 | + | Sandhoff disease | HEXB | − |

| Spinocerebellar ataxia autosomal recessive | VPS13D | − | Tay-Sachs disease | HEXA | − |

| SCYL1 | + | ||||

| SPTBN2 | − | Cockayne syndrome | ERCC6 | + | |

| EEF2 | + |

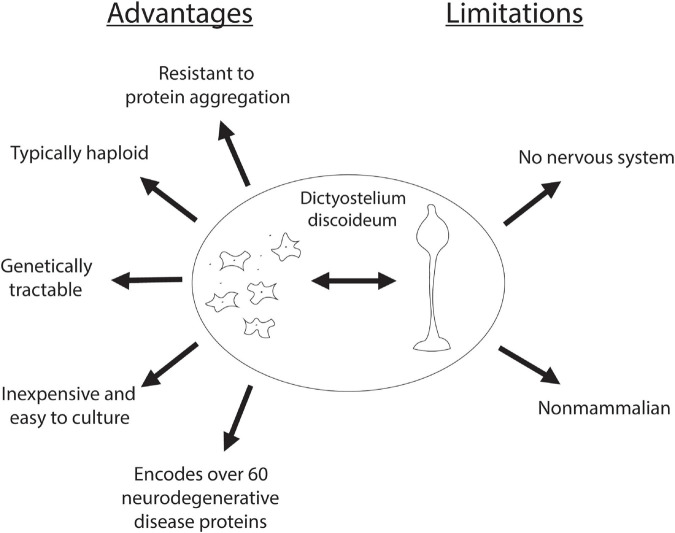

In addition to encoding for genes that cause neurodegeneration, Dictyostelium also has numerous technical advantages that make it an advantageous model system. One of these advantages is that Dictyostelium is typically haploid, simplifying gene disruption, however, it does have both sexual and parasexual cycles, enabling the investigation of gene complementation (Loomis, 1987; Bloomfield et al., 2010; Bozarro, 2013). In addition, Dictyostelium is inexpensive and easy to culture, making it an accessible model organism. Dictyostelium is also advantageous in that as an amoeba it is a single cell type, reducing the complexity associated with multiple cell types commonly found with cultured mammalian neurons. Finally, there are several genetic screening protocols established making Dictyostelium an attractive model organism for the discovery of gene function. In addition to these advantageous properties there are limitations associated with investigating neurodegenerative diseases. Most notably, Dictyostelium lacks a nervous system and thus does not have the complexity found in the human brain. Additionally, neurons are long-lived post-mitotic cells whereas Dictyostelium are rapidly dividing (Figure 2). However, despite these drawbacks, Dictyostelium has proven to be a useful model organism for probing the function and dysfunction of proteins implicated in neurodegenerative diseases.

FIGURE 2.

Advantages and limitations of Dictyostelium as a model organism for neurodegenerative diseases. Advantages of using Dictyostelium as a model for neurodegenerative diseases are listed on the left, and its limitations are listed on the right.

Investigating Neurodegeneration With Dictyostelium

Dictyostelium is a powerful model organism for understanding the underlying function of genes that are implicated in neurodegeneration. Dictyostelium continues to be utilized to interrogate the normal function of genes and to determine how disease-causing mutations alter cellular processes. This information can then be used to validate that these genes disrupt similar pathways in neurons and in the mammalian brain. Here we highlight significant findings in the field of neurodegeneration made in Dictyostelium and discuss opportunities for further utilization of Dictyostelium as a model organism to interrogate neurodegenerative diseases.

Alzheimer’s Disease

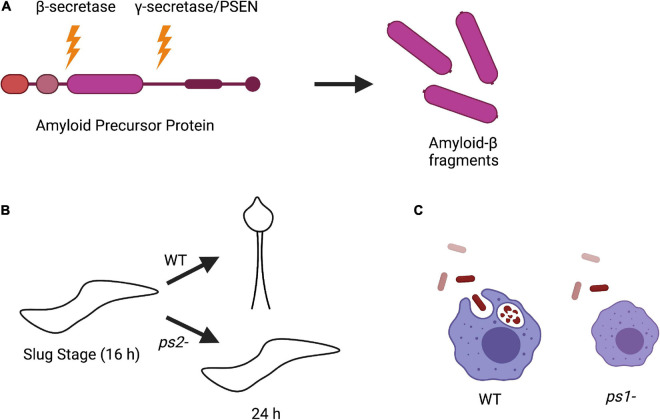

Alzheimer’s disease (AD) is the most common neurodegenerative disease. The pathological hallmarks of AD are the accumulation of extracellular amyloid-β (Aβ) plaques and intracellular tau neurofibrillary tangles. Under normal conditions, the amyloid precursor protein (APP) is processed by β-secretases, such as β-secretase 1 (BACE1), and γ-secretases to yield APP C-terminal fragments of different lengths. BACE1 initially cleaves the N-terminal region of APP, and the γ-secretase complex cleaves the C-terminal region. Presenilin (PSEN) 1 or 2 serves as the catalytic subunit of γ-secretase and is involved in processing APP into Aβ peptides (Figure 3A; De Strooper et al., 1998, 1999; Struhl and Greenwald, 1999; Wolfe et al., 1999; Esler et al., 2000; Li et al., 2000). Under normal conditions, the most abundant Aβ peptide is Aβ40, with very little of the toxic Aβ42 fragment present. However, in AD there is an alteration of APP cleavage leading to an increased Aβ42/Aβ40 ratio. This leads to the formation of Aβ aggregates that are thought to be an initial step in AD pathogenesis. Because the Aβ42/Aβ40 ratio is increased, and over 150 missense mutations in PSEN1/2 have been linked to AD pathogenesis, a large amount of research has investigated the function of the γ-secretase complex in the context of AD (De Strooper et al., 2012; Haass et al., 2012; Mucke, 2012). Therefore, model systems that interrogate the γ-secretase complex and PSENs are useful for understanding the initial steps of AD pathogenesis.

FIGURE 3.

Amyloid precursor protein (APP) processing and phenotypes of Dictyostelium PSEN knockout strains. (A) Processing of APP in human cells begins with initial cleavage by a β-secretase enzyme, followed by cleavage by presenilin in the γ-secretase complex to produce amyloid-β fragments. (B) Knockout of PSEN2 (ps2-) in Dictyostelium causes impaired ability to differentiate into pre-stalk cells during development and are unable to sporulate compared to wild-type (WT) cells. (C) Knockout of PSEN1 (ps1-) in Dictyostelium results in smaller cell size and defective phagocytosis compared to WT.

Interestingly, while Dictyostelium does not encode for a β-secretase or APP, it does express a divergent form of the γ-secretase complex. Homologous genes have been identified in Dictyostelium for all components of the γ-secretase complex including PSEN1 and PSEN2. To investigate the biological function of PSEN1 and PSEN2, knockout strains (ps1– and ps2–, respectively) were developed. ps2– cells had developmental defects, could not differentiate into pre-stalk cells during the slug stage, and were unable to sporulate, suggesting that PSEN2 γ-secretase complex activity is required for cell differentiation (Figure 3B; McMains et al., 2010). This is consistent with the observation that PSEN γ-secretase activity is involved in neuronal differentiation (Baumeister, 1999; McMains et al., 2010; van Tijn et al., 2011). On the other hand, deletion of PSEN1 resulted in a reduced phagocytic ability, consistent with data in mammalian cells that PSENs are present in lysosomal membranes (Figure 3C; McMains et al., 2010; Myre, 2012). The phenotypic differences between ps1- and ps2- Dictyostelium cells also strengthen the hypothesis that there are distinct PSEN γ-secretase complexes that serve different biological functions (Gu et al., 2004; Myre, 2012).

In addition to PSEN1 and 2 regulating phagocytosis and development, respectively, work has also been done to identify functions of additional components of the γ-secretase complex including Aph-1 and nicastrin (Ncstn) (Sharma et al., 2019). It was identified that Dictyostelium cells lacking Aph-1, Ncstn, or both PSEN proteins caused a significant decrease in micropinocytosis, indicating a role for these γ-secretase components in endocytosis. Deletion of Aph-1 or both PSEN proteins also caused a decrease in phagosomal proteolysis, an increase in the rate of autophagosome acidification, a decrease in the number of but increase in the size of Atg8-positive structures, and a severe decrease in autophagic flux. These results suggest that Aph-1 and PSEN1/2 regulate autophagy. Finally, it was observed that the large Atg-8-positive structures in Aph-1 and PSEN knockout cells contained high-molecular-weight ubiquitinated protein, consistent with an impairment in autophagic degradation. These phenotypes were rescued by the overexpression of either Dictyostelium or human catalytically inactive PSEN, consistent with PSENs and the γ-secretase complex playing non-proteolytic roles in both endocytosis and autophagy pathways (Sharma et al., 2019).

In addition to identifying the role of the γ-secretase complex in Dictyostelium biology, it was also found that wild-type Dictyostelium cells expressing human APP process APP in a similar manner as human cells, producing both Aβ40 and Aβ42 fragments. This process is dependent on the γ-secretase complex, as cells lacking components of the γ-secretase complex are unable to process APP (McMains et al., 2010). This is an intriguing observation because Dictyostelium does not encode for a β-secretase to initiate cleavage, raising the question of how Dictyostelium initially processes APP. The absence of a β-secretase should prevent the initial cleavage of APP and halt further processing. This means that Dictyostelium has a way of processing APP either without N-terminal cleavage or by another unknown enzyme that may initiate processing. Identifying how Dictyostelium initiates APP cleavage may provide novel insight into currently unknown roles of the γ-secretase complex in AD. Additionally, due to the ability to perform genetic screens, Dictyostelium may be a powerful model organism for identifying novel modulators of APP processing.

Parkinson’s Disease

Parkinson’s disease (PD) is the second-most prevalent neurodegenerative disease caused by the loss of dopaminergic neurons in the substantia nigra. This occurs, at least in part, due to the formation and accumulation of protein aggregates called Lewy bodies within the neuron’s cytoplasm. In PD, neurons have numerous problems including oxidative stress, mitochondrial dysfunction, synaptic dysfunction, and inhibition of protein quality control pathways (Cook et al., 2012; Picconi et al., 2012; Dias et al., 2013; Park et al., 2018). There are many proteins that have been implicated in PD pathogenesis, but only α-synuclein, DJ-1, and LRRK2 have been investigated in Dictyostelium thus far.

α-Synuclein

The α-synuclein protein is highly expressed in the brain, especially in dopaminergic neurons, and several α-synuclein mutations have been mapped to familial cases of PD (Stefanis, 2012). Although Dictyostelium does not encode a homolog of the α-synuclein gene, one study was performed to determine the effect of exogenous expression of α-synuclein in Dictyostelium. Expression of either wild-type or mutant α-synuclein resulted in impaired phototaxis and thermotaxis, altered fruiting body morphology, and decreased the rate of phagocytosis, consistent with a potential role for α-synuclein in disrupting mitochondrial function in Dictyostelium (Fernando et al., 2020). However, the addition of mutant or wild-type α-synuclein increases some or all aspects of mitochondrial respiration, respectively, which is contrary to the other mitochondrial phenotypes previously observed (Fernando et al., 2020). In the future, additional studies of the effects of α-synuclein expression on mitochondrial function in Dictyostelium may help clarify α-synuclein’s role in mitochondrial biology.

In addition to potentially disrupting mitochondrial function, α-synuclein also affects normal cellular functions of Dictyostelium, suggesting that it may exert some toxicity on Dictyostelium. The cause of this toxicity is unknown and further investigation may shed light on how α-synuclein exerts its toxicity. The phenotypes observed by expressing both wild-type and mutant α-synuclein did encompass some of the phenotypes required for mitochondrial dysfunction, suggesting that Dictyostelium may have mechanisms to suppress α-synuclein-induced toxicity. If so, Dictyostelium could be utilized to identify novel suppressors of mitochondrial dysfunction that could play a protective role in PD.

DJ-1

Another protein implicated in PD pathogenesis is DJ-1, a small, dimeric protein that is most highly expressed in cells with high energy demands, such as neurons. Cells with high energy demand typically have high levels of reactive oxygen species, and one function of DJ-1 is to protect cells from oxidative stress (Wagenfeld et al., 1998; Kinumi et al., 2004; Taira et al., 2004; Kim et al., 2005; Meulener et al., 2005; Wilson, 2011; Jain et al., 2012; Ottolini et al., 2013; Batelli et al., 2015; Chunna and Pu, 2017; Eberhard and Lammert, 2017; Kawate et al., 2017; Kiss et al., 2017; Smith and Wilson, 2017; Catazaro et al., 2018). DJ-1 has also been implicated to act as a chaperone, modulating the toxicity and misfolding of both α-synuclein and mutant huntingtin (Batelli et al., 2008; Wang et al., 2011; Sajjad et al., 2014; Zondler et al., 2014). There have been many DJ-1 mutations identified in PD, some of which have been clearly linked to PD pathogenesis by disrupting DJ-1 dimerization (Wilson et al., 2003; Gorner et al., 2007; Malgieri and Eliezer, 2008; Ramsey and Giasson, 2010). While DJ-1 is highly expressed in astrocytes of the frontal cortex and substantia nigra in both control and PD brains, analysis of PD brains showed decreased levels of both mRNA and protein across the entire brain (Bandopadhyay et al., 2004; Kumaran et al., 2009). Currently, the role of DJ-1 in both healthy and PD cells, as well as how it contributes to PD pathogenesis, is unknown, although it has been proposed to be linked to mitochondrial dysfunction (Repici and Giorgini, 2019).

Dictyostelium’s genome encodes a homolog of DJ-1 that has been utilized to investigate its normal biological role (Chen et al., 2017). In Dictyostelium, DJ-1 is located in the cytoplasm, and deletion of DJ-1 results in growth defects, but not mitochondrial dysfunction (Chen et al., 2017). While deletion of DJ-1 did not result in a mitochondrial phenotype, transient knockdown of DJ-1 slightly increased mitochondrial respiration whereas overexpression of DJ-1 inhibited respiration (Chen et al., 2017). The conflicting results between the DJ-1 knockout and transient knockdown strains could be due to genetic compensation that may occur in the knockout but not in the knockdown (El-Brolosy and Stainier, 2017). The conflicting findings between deletion of DJ-1 versus knockdown of DJ-1 suggest further work is warranted to understand the potential role of DJ-1 in regulating mitochondrial function in Dictyostelium.

A follow-up study decided to investigate the function of DJ-1 under oxidative stress conditions, as it could differ compared to normal cellular conditions (Chen et al., 2021). Oxidative stress on wild-type Dictyostelium cells resulted in inhibition of mitochondrial respiration and impairment of phagocytosis in an AMPK-dependent manner, which worsens during DJ-1 knockdown. Oxidative stress in combination with DJ-1 loss also leads to worsened defects in phototaxis, morphogenesis, and growth, also in an AMPK-dependent manner. These phenotypes all coincide with the Dictyostelium model of mitochondrial dysfunction. These data suggest therefore that the presence of DJ-1 in its oxidized form is protective of effects caused by oxidative stress and AMPK hyperactivity (Chen et al., 2021). Further studies should be performed to better understand the role of DJ-1 in both normal and oxidative conditions. Once the role of DJ-1 is well defined in Dictyostelium, this model system would be a powerful tool to interrogate dysfunction caused by known PD pathways and could increase our understanding of how mutations in DJ-1 result in PD pathology.

Leucine-Rich Repeat Kinase 2

Leucine-rich repeat kinase 2 (LRRK2) is a commonly mutated gene in both sporadic and inherited forms of PD. LRRK2 encodes a large protein with GTPase, kinase, and scaffolding domains (Bosgraaf and van Haastert, 2003). It is a member of the Roco protein family, having Roc (Ras of complex) and COR (C-terminus of Roc) domains, along with a leucine-rich repeat (LRR) at its N-terminus (Rui et al., 2018). LRRK2 is a cytoplasmic protein that associates with intracellular membranes, such as the endoplasmic reticulum, and vesicular structures (Hatano et al., 2007; Alegre-Abarrategui et al., 2009). LRRK2 is expressed in many tissues, but it is highly expressed in dopaminergic neurons of the mammalian brain (Biskup et al., 2006; Galter et al., 2006; Higashi et al., 2007). In PD, LRRK2 kinase activity is often increased, which in turn has many downstream effects including impaired dopamine neurotransmission, dopaminergic neuronal cell death, protein synthesis and degradation defects, increased inflammatory response, and oxidative damage (Liou et al., 2008; Carballo-Carbajal et al., 2010; Chen et al., 2012; Maekawa et al., 2016; Rui et al., 2018). Therefore, understanding the cellular pathways that regulate LRRK2’s kinase activity is warranted.

Roco proteins were originally discovered in Dictyostelium, and eleven Roco proteins have been identified in Dictyostelium, whereas only four have been identified in vertebrates, including humans (Bosgraaf et al., 2002; Bosgraaf and van Haastert, 2003). The Roco4 protein in Dictyostelium has the same domain architecture as LRRK2 (Kortholt et al., 2012). In Dictyostelium, Roco4’s Roc domain is essential for kinase activity, while the COR domain functions for protein dimerization. Point mutations within the Roco4 Roc or kinase domains inactivate it but do not lead to loss of GTP-binding (Kortholt et al., 2012). Furthermore, PD-related mutations in Roco4 revealed correlating decreases in GTPase activity and increasing kinase activity except for L1180T (LRRK2 I2020T), which shows reduced kinase activity like its LRRK2 counterpart (Jaleel et al., 2007; Ohta et al., 2010; Kortholt et al., 2012). Functionally, deletion of Roco4 or LRRK2 or expression of mutant forms of LRRK2 in Dictyostelium and in human macrophages indirectly leads to mitochondrial dysfunction (Rosenbusch et al., 2021). Therefore, Roco4 is an attractive candidate for investigating the role of LRRK2 in normal physiology and in PD. While Roco4 is similar architecturally to LRRK2, it has not been confirmed as a true homolog of LRRK2. Further work must be done to determine if Roco4 and LRRK2 are homologs. One way to do this would be attempting to rescue a Roco4 Dictyostelium knockout with LRRK2. If the knockout phenotypes are alleviated, this would suggest similar cellular roles for both Roco4 and LRRK2.

Huntington’s Disease

Huntington’s disease (HD) is caused by the expansion of a CAG trinucleotide repeat in the coding region of the huntingtin (Htt) gene. This CAG expansion is then translated into a polyglutamine (polyQ) tract in the huntingtin protein. Long polyQ tracts (>35Q) result in the misfolding and aggregation of the huntingtin protein. This aggregation process is thought to be one of the mechanisms that lead to disease pathogenesis. In addition to aggregation, both loss of normal huntingtin function and toxic gain of function have been proposed to contribute to toxicity (Ross, 1995; Perutz, 1999; Imarisio et al., 2008). Therefore, understanding the function of the huntingtin protein is important for understanding how polyQ tract expansion causes defects in huntingtin function resulting in HD pathogenesis. One way the normal function of the huntingtin protein has been investigated is by using model organisms. Htt has homologs in many model systems including mice, zebrafish, Drosophila, and Dictyostelium. Studies in these organisms suggest that huntingtin plays an important role in development (Duyao et al., 1995; Nasir et al., 1995; Zeitlin et al., 1995; Lumsden et al., 2007; Zhang et al., 2009). Therefore, Dictyostelium provides an excellent model organism to interrogate huntingtin function.

In Dictyostelium the huntingtin protein has similar features to that of human huntingtin (Chisholm et al., 2006; Myre, 2012). Interestingly, unlike human huntingtin, Dictyostelium huntingtin does not have a polyQ tract encoded in exon 1. However, it does have a short (∼19Q) polyQ tract further along in its amino acid sequence that is composed of mostly CAA trinucleotide repeats rather than CAG (Insall, 2005; Myre et al., 2011). Because the polyQ tract is not in a similar position as in humans, and because Dictyostelium has a repeat-rich genome/proteome, it is unclear if this polyQ tract plays a similar role to the polyQ tract found in the human huntingtin protein. To elucidate the function of Dictyostelium’s huntingtin protein, Htt- cells were generated. Htt- cells are viable but have many subtle phenotypes, suggesting that huntingtin is involved in multiple cellular processes (Myre et al., 2011). Htt- cells placed in a low ionic strength phosphate buffer became round and lacked membrane extensions due to a reduction in F-actin. This is consistent with mammalian studies showing that huntingtin regulates neurological processes like actin-rich dendritic spine formation and membrane branching and explains defective actin remodeling in HD patient cells (Ferrante et al., 1991; Dent et al., 2011; Munsie et al., 2011; Myre et al., 2011). Htt- cells cultured in the absence of exogenous Ca2+ cannot initiate cAMP-induced Ca2+ transients, thus impairing cAMP relaying and chemotaxis. This suggests a role for huntingtin in Dictyostelium chemotaxis and development (Myre et al., 2011). Htt- cells also failed to populate the pre-spore region of the slug and therefore did not develop into spores, indicating a need for huntingtin to make viable spores, consistent with huntingtin regulating cell fate during development (Myre et al., 2011). This data supports other vertebrate studies where similar cell fate defects have been observed in the absence of huntingtin (Reiner et al., 2001; Henshall et al., 2009). The research performed in Dictyostelium on huntingtin further supports vertebrate research that huntingtin is a multifunctional protein involved in many cellular processes. Because the huntingtin protein in Dictyostelium does not contain a polyglutamine tract it could be an interesting model system to probe the functional role of polyQ. It would be interesting to determine the effects that a normal or expanded polyQ tract in exon 1 of Dictyostelium huntingtin would have in wild-type or Htt- Dictyostelium cells. It would also be interesting to determine if human huntingtin with either a normal or expanded polyQ tract would rescue the phenotypes of Htt- Dictyostelium cells. Future studies such as these could allow us to better understand similarities between huntingtin homologs as well as help delineate differences in huntingtin’s function in its expanded form.

Neuronal Ceroid Lipofuscinosis (Batten Disease)

Neuronal ceroid lipofuscinosis (NCL), or Batten Disease, encompasses a growing class of debilitating neurodegenerative lysosomal storage diseases. NCLs are also the most common neurodegenerative diseases seen in children (Mole and Cotman, 2015). These diseases are caused by the accumulation of ceroid lipopigments in the lysosomes, along with many NCL-associated proteins (Jalanko and Braulke, 2009). There are thirteen ceroid lipofuscinosis neuronal (CLN) genes/proteins implicated in this class of diseases, with mutations in different genes giving way to different NCLs. Despite their role in NCLs, the normal functions of CLN proteins remain unclear.

CLN3

CLN3 is one of 13 proteins that when mutated cause NCL. Mutations in the CLN3 gene cause the most common subclass of NCLs, juvenile NCL (JNCL) (International Batten Disease Consortium, 1995). The CLN3 gene encodes for the CLN3 protein, a transmembrane protein that localizes to lysosomes, endosomes, and potentially other subcellular membranes (Cotman and Staropoli, 2012; Uusi-Rauva et al., 2012; Kollmann et al., 2013). While CLN3’s precise function is unknown it has been implicated in several cellular processes including lysosomal pH homeostasis, endocytic trafficking, and autophagy (Pearce et al., 1999; Holopainen et al., 2001; Gachet et al., 2005; Cao et al., 2006; Getty and Pearce, 2011).

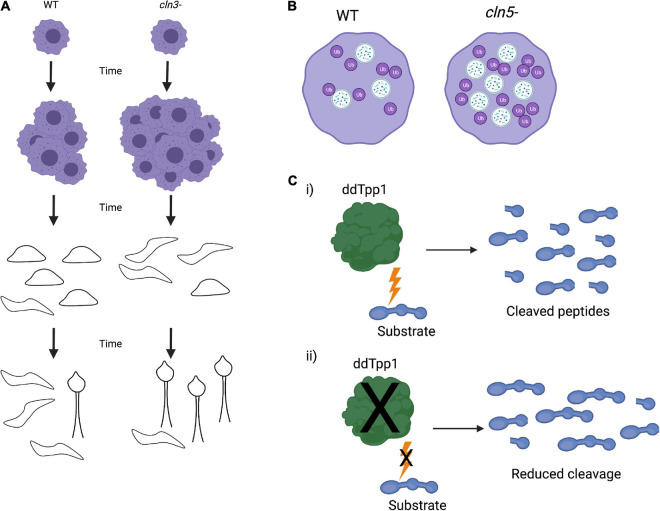

Dictyostelium’s genome has a homolog for CLN3 (Cln3), which was used as a model to understand its normal function (Huber et al., 2014). In Dictyostelium, deletion of Cln3 results in increased proliferation during vegetative growth. This increase in growth is caused by altered levels of secretory proteins that regulate proliferation signaling. RNAseq revealed that Cln3 mRNA levels dramatically increase during mid-development. Consistent with a role for Cln3 at mid-development, cln3– cells showed faster slug formation, increased slug migration, and accelerated fruiting body formation, suggesting that Cln3 plays a role in regulating the speed of development (Figure 4A; Rot et al., 2009; Huber et al., 2014). Ca2+ chelation was found to restore developmental timing to the rate of WT cells and suppresses abnormal slug migration, indicating that Cln3 also regulates Ca2+-dependent developmental events (Huber et al., 2014).

FIGURE 4.

Dictyostelium phenotypes of Cln knockout strains. (A) Knockout of Cln3 (cln3–) in Dictyostelium leads to an increase in vegetative growth as well as faster slug formation, migration, and fruiting body formation. (B) Cln5 knockout (cln5–) results in an increase in autophagosome formation and ubiquitination of proteins, indicating upregulated autophagic activity. (C) Dictyostelium ddTpp1 normally cleaves a synthetic human substrate of human TPP1 (i), but in tpp1- cells, cleavage of the substrate is greatly reduced (ii).

While cln3– cells have accelerated fruiting body formation, cln3– cells also have a delay in streaming and aggregation due to reduced cell-cell adhesion (Huber et al., 2017). Further investigation into this phenotype determined that Cln3 localizes to the contractile vacuole network and colocalizes with the Golgi marker wheat germ agglutinin. This suggests that Cln3 is involved in both conventional and unconventional secretory pathways during development. Mass spectrometry of wild-type versus cln3– Dictyostelium cells revealed that the most affected proteins in cln3– cells were involved in endocytosis, vesicle-mediated transport, proteolysis, and metabolism, supporting the hypothesis that Cln3 plays a role in secretory pathways (Huber, 2017). Cln3 has also been implicated in Dictyostelium’s osmoregulation, and osmoregulatory defects have been observed in mammalian cell models of Batten disease (Stein et al., 2010; Getty et al., 2013; Tecedor et al., 2013; Mathavarajah et al., 2018). Under hypotonic stress, cln3– cells show defects in cytokinesis, have reduced viability and impaired spore integrity. Under hypertonic stress, cln3– cells also have reduced viability and development is inhibited (Mathavarajah et al., 2018). This indicates Cln3 plays an important role in osmoregulation.

Finally, RNAseq analysis of cln3– Dictyostelium cells unveiled over 1,000 genes that are differentially expressed during Dictyostelium starvation, including many homologs of NCL genes. Loss of Cln3 alters the expression and activity of lysosomal enzymes, increases lysosomal pH, and alters nitric oxide homeostasis (Huber and Mathavarajah, 2019). Upregulation of the Dictyostelium homolog of tripeptidyl peptidase 1 (Tpp1) was also observed, in addition to a correlating increase in Tpp1 enzyme activity (Mathavarajah et al., 2018). Autofluorescent storage bodies were observed in starving Dictyostelium cells, which were also found in starving tpp1- cells, linking Cln3 function to Tpp1 activity (Phillips and Gomer, 2015; Huber and Mathavarajah, 2019). Because Cln3 has conserved function in Dictyostelium and human cells, further studies are warranted to fully understand Cln3 function and to determine how mutations in Cln3 result in disease.

CLN5

Another protein implicated in NCLs is CLN5. Mutations in CLN5 have been linked to late infantile, juvenile, and adult NCLs (Pineda-Trujillo et al., 2005; Cannelli et al., 2007; Xin et al., 2010; Mancini et al., 2015; Simonati et al., 2017). CLN5 localizes to the lysosomal matrix and extracellular space and alters numerous processes including neurogenesis, synaptic recycling, and autophagy (Isosomppi et al., 2002; von Schantz et al., 2008; Schmiedt et al., 2012; Larkin et al., 2013; Moharir et al., 2013; Fabritius et al., 2014; Hughes et al., 2014; Cárcel-Trullols et al., 2015; De Silva et al., 2015; Best et al., 2017; Jules et al., 2017; Leinonen et al., 2017; Uusi-Rauva et al., 2017). However, the precise function of CLN5 and its role in NCLs is unknown.

Similar to Cln3, Dictyostelium also expresses a homolog of CLN5 (Cln5). Cln5 localizes to the ER, and both Dictyostelium Cln5 and exogenous human CLN5 have glycoside hydrolase activity in Dictyostelium cells. Immunoprecipitation and mass spectrometry identified numerous Cln5 interactors, many of which are implicated in NCLs. Some of these interactors include cathepsin D, tripeptidyl peptidase 1, and CDC48 (Huber and Mathavarajah, 2018). Further investigation of Cln5 was found that cln5–- cells have reduced cell proliferation, cytokinesis, viability, folic acid-mediated endocytosis, and growth in nutrient-limited media. cln5– cells develop more rapidly than wild-type cells (McLaren et al., 2021). cln5– cells also exhibit impaired spore morphology, germination, and viability. At a cellular level deletion of cln5 results in an increased number of autophagosomes and ubiquitinated proteins, consistent with increased autophagic activity (Figure 4B). Development in the presence of an autophagy inhibitor impaired the formation of developmental structures, including reduction in slug size (McLaren et al., 2021). These data suggest that Cln5 plays a similar role in both Dictyostelium and human biology and may play a role in autophagy. Further work using Cln5 in Dictyostelium, including introducing pathogenic NCL mutations, may contribute to better understanding the native function of CLN5 and NCL pathogenesis. These studies could also be expanded into mammalian systems to confirm the findings in Dictyostelium and facilitate therapeutic avenues for NCLs.

Tripeptidyl Peptidase 1

Another subclass of NCL, late infantile NCL (LINCL), is caused primarily by mutations in tripeptidyl peptidase 1 (TPP1, also known as CLN2), a lysosomal peptidase (Sleat et al., 1997). TPP1 cleaves tripeptides of the N-terminus of proteins with optimal peptidase activity occurring at pH 3.5 (Vines and Warburton, 1998; Sohar et al., 1999). However, its in vivo substrates and physiological function are unknown (Phillips and Gomer, 2015). Studies in LINCL fibroblasts revealed that the lysosomal TPP1’s activity is dramatically reduced compared to fibroblasts from unaffected individuals (Vines and Warburton, 1999). While TPP1 is conserved among vertebrates, there are no homologs of TPP1 found among most invertebrate model organisms such as Drosophila, C. elegans, and S. cerevisiae, limiting the utilization of these model organisms in investigating TPP1 function (Wlodawer et al., 2003; Phillips and Gomer, 2015).

Unlike other lower eukaryotes, Dictyostelium does possess a homolog of TPP1, ddTpp1. Deletion of ddTpp1 results in a reduced, but not a complete loss of, the ability to cleave a synthetic substrate of human TPP1 (Figure 4C). Both ddTpp1 and human TPP1 localize to the lysosome when expressed in Dictyostelium. tpp1- cells display normal vegetative growth but undergo development more rapidly than wild-type cells. Once developed, the fruiting bodies also have a reduced number of spores. Starved tpp1- cells form intracellular auto-fluorescent bodies analogous to those found in patients lacking TPP1, and tpp1- cells starved of amino acids are smaller in size and have reduced viability, indicating defects in autophagy. Finally, in the presence of chloroquine (a lysosome-perturbing compound), tpp1- cells have a highly impaired developmental cycle (Phillips and Gomer, 2015). These data point to ddTpp1 playing roles in both autophagy and Dictyostelium’s developmental cycle. Consistent with this, inhibition of autophagy by treating cells with the target of rapamycin (TOR) complex inhibitor rapamycin or by knocking down the upstream activator of the TOR complex Ras homology enriched in brain (RHEB) results in the same phenotypes observed in tpp1- cells (Smith et al., 2019). Furthermore, overexpression of RHEB rescues these defects, suggesting that TOR signaling could be responsible for tpp1- phenotypes (Smith et al., 2019). It is important to note that knocking out ddTpp1 does not cause a complete loss of substrate cleavage (Phillips and Gomer, 2015). This suggests that there may be other proteases or peptidases present in Dictyostelium that could be substituted for ddTPP1. If so, this could mean there may be compensatory cleavage mechanisms in human cells as well. In the future it would be interesting to identify other proteases that can cleave TPP1 substrates in Dictyostelium. Identification of other proteins that can cleave TPP1 substrates may lead to novel ideas to guide the design of LINCL therapies in the future.

Hirano Bodies

Hirano bodies are cytoplasmic protein aggregates that have crystalloid fine rod structures (Cartier et al., 1985; Hirano, 1994). They contain numerous different proteins such as actin, actin-binding proteins, microtubule-associated proteins, tau, C-terminal fragments of APP, and neurofilaments (Hirano, 1994). These inclusions are seen preferentially in the neuronal processes of patients of many neurodegenerative diseases including AD, parkinsonism-dementia, amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS), Creutzfeldt-Jacob disease, and Pick’s disease (Cartier et al., 1985; Hirano, 1994). However, Hirano bodies have also been found in other cell types such as glia, peripheral nerve axons, and extraocular muscles of the eyes (Tomanaga, 1983). While Hirano bodies are associated with neurodegenerative diseases, Hirano bodies also form as a function of age and can be found in the brain of aged people without neurodegenerative diseases (Gibson and Tomlinson, 1997).

Dictyostelium does not naturally form Hirano bodies, however, it has been used to model them. A model of Hirano bodies was created in Dictyostelium using the Dictyostelium actin crosslinking protein called the 34-kDa protein (Maselli et al., 2002). By expressing the C-terminal fragment of the 34-kDa protein (CT) in Dictyostelium, the formation of para-crystalline inclusions resembling Hirano bodies was observed. These structures contain ordered assemblies of CT, F-actin, myosin II, cofilin, and α-actinin, typical of human Hirano bodies. Developmental studies performed on Dictyostelium expressing CT found that development was delayed by 6 h. In addition to Dictyostelium, expressing CT in multiple mammalian cell systems induced the same F-actin rearrangement and Hirano body formation (Maselli et al., 2002). This indicates that Dictyostelium and mammalian cells use similar pathways to form Hirano bodies. The delay in Dictyostelium development in the presence of CT also suggests that CT causes cellular defects. Further characterization of the Dictyostelium model of Hirano bodies revealed that Hirano bodies can be cleared from the cell through both the autophagy and ubiquitin-proteasome degradation pathways (Kim et al., 2009). Additionally, mass spectrometry performed on partially purified Hirano bodies from Dictyostelium identified numerous proteins involved, including proteins involved with the cytoskeleton (Dong et al., 2016). Of these, four proteins were further investigated in the context of model Hirano bodies: profilin, actin-related protein (Arp) 2/3, vasodilator-stimulated phosphoprotein (VASP), and Wiskott-Aldrich Syndrome protein and scar homolog (WASH). Hirano bodies were unable to form under Arp2/3 inhibition and in cells lacking VASP or HSPC300, a protein involved in the WAVE (Wiskott-Aldrich Syndrome protein family verprolin-homologous protein) complex and activator of Arp2/3. This suggests that Hirano bodies require de novo actin polymerization to form in Dictyostelium (Dong et al., 2016). Because Dictyostelium can be used as an inducible model of Hirano bodies by expression of CT, it can be useful for further characterization of Hirano bodies as well as observation of long-term effects Hirano bodies may have on cellular functions. These studies can also be validated in mammalian systems expressing CT to help us better understand how Hirano bodies form and the effects they have on cellular processes.

Mitochondrial Dysfunction

Mitochondria perform critical functions including metabolism and ATP production, reduction-oxidation control, and free-radical scavenging (Reddy, 2007, 2009). Because the brain has a high energy demand, mitochondrial function is critical to neuronal health (Han et al., 2021). Mitochondrial dysfunction has been observed in many neurodegenerative diseases including AD, PD, and ALS; however, it is unclear if mitochondrial dysfunction is a cause or byproduct of neurodegenerative diseases (Reddy and Beal, 2005; Manczak et al., 2006; Viscomi et al., 2016; Onyango et al., 2017; Pearce et al., 2019). In many familial neurodegenerative disease cases, mutant proteins such as Aβ in AD, parkin, DJ-1, and α-synuclein in PD, huntingtin in HD, and superoxide dismutase 1 (SOD1) in ALS can localize to the mitochondria. This has been suggested to cause a decrease in ATP production as well as an increase in free radical production, leading to degeneration (Beal, 2005; Reddy and Beal, 2008; Reddy, 2009). In PD, there are numerous mitochondrial genes mutated in familial cases that correspond to dysfunction including DJ-1, LRRK2, PRKN, PINK1, and HTRA2 (Kalinderi et al., 2016; Narendra, 2016; Pearce et al., 2019; Han et al., 2021). However, it is still largely unknown if and how mutations in neurodegenerative proteins exert toxicity on mitochondria. Aging also contributes to changes observed in mitochondrial function. Over time, defects in mitochondrial DNA accumulate and results in increased production of reactive oxygen species, which are ultimately involved in late-onset diseases and cell death (Swerdlow and Khan, 2004; Beal, 2005; Lin and Beal, 2006; Reddy, 2008; Reddy and Beal, 2008). However, why some individuals are more susceptible to late-onset neurodegenerative diseases than others is still unknown.

Dictyostelium mitochondrial pathways are similar to those of most eukaryotes and have many homologous proteins to mammalian mitochondrial proteins. Importantly, the oxidative phosphorylation pathway is the same between Dictyostelium and mammalian systems (Pearce et al., 2019). This makes Dictyostelium an attractive model for studying mitochondrial toxicity of proteins implicated in mitochondrial dysfunction in neurodegenerative diseases. Dictyostelium is a well-studied model of mitochondrial dysfunction. In Dictyostelium, mitochondrial dysfunction is defined by specific phenotypes including impaired phototaxis and thermotaxis, growth defects in axenic medium (pinocytosis) and on bacterial lawns (phagocytosis), chronic activation of AMP kinase, shorter and thicker stalks due to increased cell differentiation into pre-stalk cells, and altered ability to transition from growth to development (Bokko et al., 2007; Francione et al., 2011). Dictyostelium can therefore be easily used to investigate neurodegenerative disease proteins in the context of mitochondrial dysfunction. Dictyostelium encodes for many homologs of neurodegenerative disease proteins implicated in mitochondrial dysfunction, meaning they can be easily mutated or deleted to study their effects on mitochondria, such as with DJ-1 (Chen et al., 2017, 2021). However, there are some neurodegenerative disease proteins that do not have homologs in Dictyostelium, in which case these proteins can be introduced into Dictyostelium and their effects observed, such as with α-synuclein (Fernando et al., 2020). Overall, Dictyostelium provides a simple and useful model for studying the effects of neurodegenerative disease proteins on mitochondrial function.

Homologous Neurodegenerative Disease Genes and Proteins Not Yet Studied in Dictyostelium

In addition to the studies discussed above, there are over 50 homologous neurodegenerative disease genes expressed in Dictyostelium (Table 1). Investigation of these genes in Dictyostelium will likely uncover novel aspects of their function. While Dictyostelium does not contain a complex nervous system that will uncover all aspects of their functions, it does have a more simplified genome that may result in decreased layers of genetic redundancy, unveiling novel aspects of gene function that may be missed in more complex organisms. Additionally, due to its larger genome, Dictyostelium expresses approximately 30 more neurodegenerative disease proteins than S. cerevisiae, allowing for investigation of the role of these proteins in a single-celled organism (Table 2).

Of the genes previously mentioned, PSEN1, PSEN2, DJ-1, HTT, CLN3, CLN5, and TPP1 (CLN2) are present in Dictyostelium but not S. cerevisiae. There are also four other AD-related genes, one other PD-related gene, and three other NCL-related genes expressed in Dictyostelium that have yet to be investigated in Dictyostelium. In addition, many other neurodegenerative diseases have the potential to be studied using Dictyostelium as a model organism. For example, Dictyostelium expresses genes implicated in ALS and some spinocerebellar ataxias. Dictyostelium also has homologous genes involved in other rare neurodegenerative diseases including Niemann-Pick, Refsum, and Tay-Sachs diseases, among others (Table 2). Notably, these genes are not expressed in S. cerevisiae, making Dictyostelium an advantageous single-cell model for studying the functions of these proteins. Dictyostelium can be utilized to learn about both normal and mutant functions of these proteins and consequently interrogate the pathways involved in the pathogenesis of their respective diseases.

The Polyglutamine Diseases and Dictyostelium’s Polyglutamine/Asparagine-Rich Proteome

One unique aspect of Dictyostelium’s genome is that it has a remarkably large number of single sequence repeats (SSRs). Interestingly, many of these SSRs are present in protein-coding regions of genes, resulting in Dictyostelium encoding nearly 10,000 homopolymeric amino acid tracts. Surprisingly, there are homopolymeric tracts for every amino acid except tryptophan, with asparagine (N) and glutamine (Q) being the most abundant repeats (Eichinger et al., 2005). This is surprising because polyQ tracts cause a class of nine neurodegenerative diseases and Dictyostelium naturally encodes long polyQ repeats that are well beyond the disease threshold of ∼40 glutamines (Eichinger et al., 2005; Santarriaga et al., 2015). In addition to long polyQ repeats, there are numerous Dictyostelium proteins that have Q/N-rich sequences and are described as prion-like (Malinovska et al., 2015). Prions are proteins that can misfold and subsequently become transmissible. Other cells can then be infected by the transmission of misfolded prions, and this can impress the misfolded conformation on the normal proteins, causing prion diseases (Hope et al., 1986; Come et al., 1993; Cohen et al., 1994; Gajdusek, 1996; Harris, 1999; Bolton and Bendheim, 2007). Yeast has been commonly used as a model to study prion diseases as it expresses several prion proteins that are transmissible after misfolding (Liebman and Chernoff, 2012). The sequences of yeast prion proteins are Q/N-rich, making them more prone to misfolding and aggregation (Balch et al., 2008; Alberti et al., 2009; Halfmann et al., 2010, 2012). Prion-like sequences are also found in some aggregation-prone human neurodegenerative disease proteins (Gitler and Shorter, 2011; King et al., 2012; Kim et al., 2013). Surprisingly, Q/N-rich sequences naturally encoded in Dictyostelium do not aggregate, and it is unknown whether these Dictyostelium proteins share prion biology (Malinovska et al., 2015).

To date, only a few studies have investigated the roles that proteins with long amino acid tracts serve in Dictyostelium biology. Gene ontology annotation of the polyN and polyQ proteins revealed these repeats are enriched in protein kinases, lipid kinases, transcription factors, RNA helicases, and mRNA binding proteins associated with the spliceosome (Eichinger et al., 2005). Further bioinformatic analysis and gene ontology on proteins in Dictyostelium with Q/N-rich, prion-like sequences revealed that these sequences are linked to both proteinase K-like domains and RNA-binding domains (Malinovska et al., 2015). Prion-like domains were also found to be enriched in proteins associated with DNA/RNA interactions, protein modification, and signaling processes. It was concluded that these Q/N-rich sequences are not randomly occurring, but rather are conserved within the same protein families across Dictyostelid species (Malinovska et al., 2015). This suggests that the polyQ/N proteins may serve important biological functions related to DNA replication, transcription, and protein modification. However, research regarding the roles of homopolymeric repeats in Dictyostelium has not been readily pursued and the functions these polyQ/N proteins play are still largely unknown. It is intriguing that these proteins could be functional in Dictyostelium, and therefore future studies should be dedicated to learning more about the purpose of these proteins in Dictyostelium biology.

Dictyostelium is Naturally Resistant to Polyglutamine Aggregation

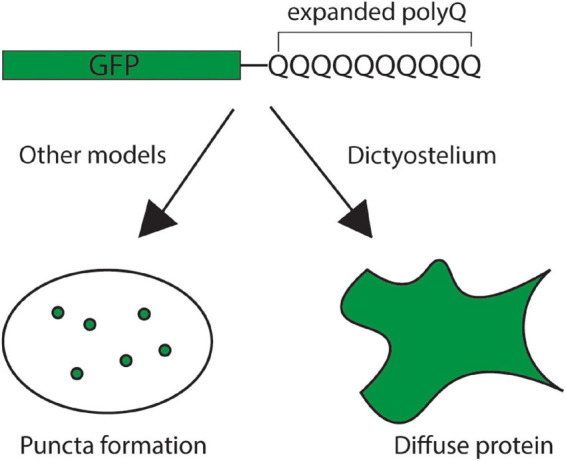

In addition to glutamine-rich regions forming prions, proteins with long polyQ tracts (>35Q) also cause a class of nine neurodegenerative diseases called the polyQ diseases. In these diseases, polyQ tracts within the coding region of specific genes become expanded resulting in aggregation-prone proteins that are neurotoxic. This led to the question: Is Dictyostelium naturally resistant to polyQ aggregation? Interestingly, unlike other model organisms, Dictyostelium is resistant to aggregation of mutant huntingtin exon 1 with 103 glutamines (Figure 5; Malinovska et al., 2015; Santarriaga et al., 2015). This is surprising because this fragment is highly aggregation-prone in other model organisms (DiFiglia et al., 1997; Li and Li, 1998; Krobitsch and Lindquist, 2000; Meriin et al., 2002; Santarriaga et al., 2015). To begin understanding how Dictyostelium resists protein aggregation a restriction enzyme mediated integration (REMI) screen was utilized to identify genes that are necessary for suppressing polyQ aggregation in Dictyostelium. This screen identified one gene that encodes for serine-rich chaperone protein 1 (SRCP1). Interestingly, SRCP1 is both necessary for suppressing polyglutamine aggregation in Dictyostelium and sufficient to suppress polyQ aggregation in other organisms (Santarriaga et al., 2018). One caveat of this screen was that it did not approach genome-wide coverage and additional suppressors of polyQ aggregation in Dictyostelium likely exist. The development of novel screening pipelines will enable genome-wide coverage in future screens, fully elucidating the genes that are essential for suppressing polyQ aggregation in Dictyostelium (Williams et al., 2021).

FIGURE 5.

Dictyostelium is resistant to polyglutamine aggregation. Expression of an exogenous, pathogenic GFP-tagged mutant huntingtin exon 1 protein with an expanded polyglutamine tract yields the formation of polyglutamine puncta in the cells of most model organisms, indicating protein aggregation (left). In Dictyostelium, however, the mutant huntingtin protein remains diffuse throughout the cell, indicating that the protein remains soluble (right).

Dictyostelium’s resistance to polyQ aggregation raises many questions about how protein quality control pathways are regulated in Dictyostelium. In the future, studies investigating Dictyostelium’s response to various stressors are warranted and may identify novel aspects that regulate protein quality control. Initial work has identified heat shock protein 101 (Hsp101) as a key suppressor of polyQ aggregation during heat stress (Malinovska et al., 2015). However, the proteins and pathways that are necessary for suppressing protein aggregation during various states of stress in Dictyostelium are unknown. Identification of novel aspects of Dictyostelium protein quality control may lead to new insights into how Dictyostelium maintains proteostasis of its repeat-rich proteome during cellular stress.

Finally, understanding how Dictyostelium resists polyQ aggregation may lead to the development of novel therapeutics to treat neurodegenerative diseases. Toward this end, it was found that in addition to polyQ, SRCP1 can also suppress aggregation of superoxide dismutase 1 (SOD1) in human cells. Furthermore, SRCP1 was packaged in adeno-associated virus 9 (AAV9) and injected into the cortex of a mouse model of ALS. Expression of SOD1 in this mouse model resulted in decreased SOD1 aggregation in the cortex, however, it did not result in an increase in lifespan (Luecke et al., 2021). In the future, it will be important to deliver SRCP1 directly to affected neuronal populations to determine if SRCP1 provides neuroprotective properties in models of neurodegeneration.

Conclusion

Neurodegenerative diseases are incurable diseases with few treatment options. In many neurodegenerative diseases, the proteins that are mutated or accumulate have unknown functions. Simple model organisms including Dictyostelium discoideum provide a platform to investigate the normal function of these proteins and to perform genetic screens to identify genes that modulate their functions. Because Dictyostelium is a simple model organism with a single cellular stage and encodes for numerous proteins implicated in neurodegenerative diseases, it is useful for understanding the normal function of these proteins and for identifying pathways that are disrupted in disease states. For example, knockout screens can easily be employed to determine the functions of the many homologous neurodegenerative disease proteins expressed in Dictyostelium. Additionally, the introduction of normal and mutant neurodegenerative disease genes not encoded for in Dictyostelium’s genome could also serve to identify protein functions and toxicity as well as cellular pathways affected. Dictyostelium may also be used to identify novel protein interactors with neurodegenerative disease proteins. Another important observation that must be further studied is Dictyostelium’s resistance to protein aggregation. Elucidating Dictyostelium’s proteostatic pathways could allow us to observe how Dictyostelium evolutionarily overcame the obstacle of protein aggregation. In the future, Dictyostelium can continue to serve as a simple, yet powerful, model to investigate neurodegenerative diseases and expand our knowledge to treat these diseases.

Author Contributions

HH wrote the initial draft. HH and KS conceptualized and edited the review, contributed to the article, and approved the submitted version.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher’s Note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Acknowledgments

Figures 3, 4 were created with BioRender.com.

Funding

This work was supported by National Institutes of Health grants NS112191 and GM119544 to KS.

References

- Alberti S., Halfmann R., King O., Kapila A., Lindquist S. (2009). A systematic survey identifies prions and illuminates sequence features of prionogenic proteins. Cell 137 146–158. 10.1016/j.cell.2009.02.044 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alegre-Abarrategui J., Christian H., Lufino M., Mutihac R., Venda L., Ansorge O., et al. (2009). LRRK2 regulates autophagic activity and localizes to specific membrane microdomains in a novel human genomic reporter cellular model. Hum. Mol. Genet. 18 4022–4034. 10.1093/hmg/ddp346 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Andrews B., Boone C., Davis T., Fields F. (2016). Budding Yeast: A Laboratory Manual. New York: Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press. [Google Scholar]

- Balch W., Morimoto R., Dillin A., Kelly J. (2008). Adapting proteostasis for disease intervention. Science 319 916–919. 10.1126/science.1141448 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bandopadhyay R., Kingsbury A., Cookson M., Reid A., Evans I., Hope A., et al. (2004). The expression of DJ-1 (PARK7) in normal human CNS and idiopathic Parkinson’s disease. Brain 127 420–430. 10.1093/brain/awh054 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Batelli S., Albani D., Rametta R., Polito L., Prato F., Pesaresi M., et al. (2008). DJ-1 modulates alpha-synuclein aggregation state in a cellular model of oxidative stress: relevance for Parkinson’s disease and involvement of HSP70. PLoS One 3:e1884. 10.1371/journal.pone.0001884 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar] [Retracted]

- Batelli S., Invernizzi R., Negro A., Calcagno E., Rodilossi S., Forloni G., et al. (2015). The Parkinson’s disease-related protein DJ-1 protects dopaminergic neurons in vivo and cultured cells from alpha-synuclein and 6-hydroxydopamine toxicity. Neurodegen. Dis. 15 13–23. 10.1159/000367993 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baumeister R. (1999). The physiological role of presenilins in cellular differentiation: lessons from model organisms. Eur. Arch. Psychiatry Clin. Neurosci. 249 280–287. 10.1007/s004060050100 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beal M. (2005). Mitochondria take center stage in aging and neurodegeneration. Ann. Neurol. 58 495–505. 10.1002/ana.20624 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Best H., Neverman N., Wicky H., Mitchell N., Leitch B., Hughes S. (2017). Characterisation of early changes in ovine CLN5 and CLN6 Batten disease neural cultures for the rapid screening of therapeutics. Neurobiol. Dis. 100 62–74. 10.1016/j.nbd.2017.01.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Biskup S., Moore D., Celsi F., Higashi S., West A., Andrabi S., et al. (2006). Localization of LRRK2 to membranous and vesicular structures in mammalian brain. Ann. Neurol. 60 557–569. 10.1002/ana.21019 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bloomfield G., Skelton J., Ivens A., Tanaka Y., Kay R. (2010). Sex determination in the social amoeba Dictyostelium discoideum. Science 330 1533–1536. 10.1126/science.1197423 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bokko P., Francione L., Bandala-Sanchez E., Ahmed A., Annesley S., Huang X., et al. (2007). Diverse cytopathologies in mitochondrial disease are caused by AMP-activated protein kinase signaling. Mol. Biol. Cell 18 1874–1886. 10.1091/mbc.e06-09-0881 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bolton D., Bendheim P. (2007). “A modified host protein model of scrapie,” in Ciba Foundation Symposium Novel Infectious Agents and the Central Nervous System, (Chichester: John Wiley & Sons, Ltd; ), 164–181. 10.1002/9780470513613.ch11 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bosgraaf L., Russcher H., Smith J., Wessels D., Soll D., van Haastert P. (2002). A novel cGMP signalling pathway mediating myosin phosphorylation and chemotaxis in Dictyostelium. EMBO J. 21 4560–4570. 10.1093/emboj/cdf438 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bosgraaf L., van Haastert P. (2003). Roc, a Ras/GTPase domain in complex proteins. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1643 5–10. 10.1016/j.bbamcr.2003.08.008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bozarro S. (2013). “The Model Organism Dictyostelium discoideum,” in Dictyostelium discoideum Protocols: Methods in Molecular Biology (Methods and Protocols), eds Eichinger L., Rivero F. (Totowa: Humana Press; ), 17–37. 10.1007/978-1-62703-302-2_2 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Cannelli N., Nardocci N., Cassandrini D., Morbin M., Aiello C., Bugiani M., et al. (2007). Revelation of a novel CLN5 mutation in early juvenile neuronal ceroid lipofuscinosis. Neuropediatrics 38 46–49. 10.1055/s-2007-981449 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cao Y., Espinola J., Fossale E., Massey A., Cuervo A., MacDonald M., et al. (2006). Autophagy is disrupted in a knock-in mouse model of juvenile neuronal ceroid lipofuscinosis. J. Biol. Chem. 281 20483–20493. 10.1074/jbc.M602180200 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carballo-Carbajal I., Weber-Endress S., Rovelli G., Chan D., Wolozin B., Klein C., et al. (2010). Leucine-rich repeat kinase 2 induces α-synuclein expression via the extracellular signal-regulated kinase pathway. Cell. Signal. 22 821–827. 10.1016/j.cellsig.2010.01.006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cárcel-Trullols J., Kovács A., Pearce D. (2015). Cell biology of the NCL proteins: what they do and don’t do. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1852 2242–2255. 10.1016/j.bbadis.2015.04.027 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cartier L., Galvez S., Gajdusek D. (1985). Familial clustering of the ataxic form of Creutzfeldt-Jacob disease with Hirano bodies. J. Neurol. Neurosurg Psychiatry 48 234–238. 10.1136/jnnp.48.3.234 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Catazaro J., Andrews T., Milkovic N., Lin J., Lowe A., Wilson M., et al. (2018). (15)N CEST data and traditional model-free analysis capture fast internal dynamics of DJ-1. Anal. Biochem. 542 24–28. 10.1016/j.ab.2017.11.012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen C., Weng Y., Chien K., Lin K., Yeh T., Cheng Y., et al. (2012). (G2019S) LRRK2 activates MKK4- JNK pathway and causes degeneration of SN dopaminergic neurons in a transgenic mouse model of PD. Cell Death Differ. 19 1623–1633. 10.1038/cdd.2012.42 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen S., Annesley S., Jasim R., Fisher P. (2021). The Parkinson’s Disease-Associated Protein DJ-1 Protects Dictyostelium Cells from AMPK-Dependent Outcomes of Oxidative Stress. Cells 10:1874. 10.3390/cells10081874 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen S., Annesley S., Jasim R., Musco V., Sanislav O., Fisher P. (2017). The Parkinson’s disease-associated protein DJ-1 plays a positive nonmitochondrial role in endocytosis in Dictyostelium cells. Dis. Model. Mech. 10 1261–1271. 10.1242/dmm.028084 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chisholm R., Gaudet P., Just E., Pilcher K., Fey P., Merchant S., et al. (2006). dictyBase, the model organism database for Dictyostelium discoideum. Nucleic Acids Res. 34 D423–D427. 10.1093/nar/gkj090 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chunna A., Pu X. (2017). Role of DJ-1 in Fertilization. Adv. Exp. Med. Biol. 1037 61–66. 10.1007/978-981-10-6583-5_5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cohen F., Pan K., Huang Z., Baldwin M., Fletterick R., Prusiner S. (1994). Structural clues to prion replication. Science 264 530–531. 10.1126/science.7909169 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Come J., Fraser P., Lansbury P., Jr. (1993). A kinetic model for amyloid formation in the prion diseases: importance of seeding. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 90 5959–5963. 10.1073/pnas.90.13.5959 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- International Batten Disease Consortium (1995). Isolation of a novel gene underlying Batten disease, CLN3. Cell 82 949–957. 10.1016/0092-8674(95)90274-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cook C., Stetler C., Petrucelli L. (2012). Disruption of Protein Quality Control in Parkinson’s Disease. Cold Spring Harb. Perspect. Med. 2:a009423. 10.1101/cshperspect.a009423 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cotman S., Staropoli J. (2012). The juvenile Batten disease protein, CLN3, and its role in regulating anterograde and retrograde post-Golgi trafficking. Clin. Lipidol. 7 79–91. 10.2217/clp.11.70 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dawson T., Golde T., Lagier-Tourenne C. (2018). Animal models of neurodegenerative diseases. Nat. Neurosci. 21 1370–1379. 10.1038/s41593-018-0236-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Silva B., Adams J., Lee S. (2015). Proteolytic processing of the neuronal ceroid lipofuscinosis related lysosomal protein CLN5. Exp. Cell Res. 338 45–53. 10.1016/j.yexcr.2015.08.021 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Strooper B., Annaert W., Cupers P., Saftig P., Craessaerts K., Mumm J., et al. (1999). A presenilin-1-dependent g-secretase-like protease mediates release of Notch intracellular domain. Nature 398 518–522. 10.1038/19083 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Strooper B., Iwatsubo T., Wolfe M. (2012). Presenilins and g-Secretase: structure, function, and role in Alzheimer Disease. Cold Spring Harb. Perspect. Med. 2:a006304. 10.1101/cshperspect.a006304 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Strooper B., Saftig P., Craessaerts K., Vanderstichele H., Guhde G., Annaert W., et al. (1998). Deficiency of presenilin-1 inhibits the normal cleavage of amyloid precursor protein. Nature 391 387–390. 10.1038/34910 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dent E., Merriam E., Hu X. (2011). The dynamic cytoskeleton: backbone of dendritic spine plasticity. Curr. Opin. Neurol. 21 175–181. 10.1016/j.conb.2010.08.013 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dias V., Junn E., Maral Mouradian M. (2013). The Role of Oxidative Stress in Parkinson’s Disease. J. Parkinsons Dis. 3 461–491. 10.3233/JPD-130230 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DiFiglia M., Sapp E., Chase K., Davies S., Bates G., Vonsattel J., et al. (1997). Aggregation of huntingtin in neuronal intranuclear inclusions and dystrophic neurites in brain. Science 277 1990–1993. 10.1126/science.277.5334.1990 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dong Y., Shahid-Salles S., Sherling D., Fechheimer N., Iyer N., Wells L., et al. (2016). De novo actin polymerization is required for model Hirano body formation in Dictyostelium. Biol. Open 5 807–818. 10.1242/bio.014944 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Duyao M., Auerback A., Ryan A., Perischetti F., Barnes G., McNeil S., et al. (1995). Inactivation of the mouse Huntington’s disease gene homolog Hdh. Science 269 407–410. 10.1126/science.7618107 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eberhard D., Lammert E. (2017). The Role of the Antioxidant Protein DJ-1 in Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus. Adv. Exp. Med. Biol. 1037 173–186. 10.1007/978-981-10-6583-5_11 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eichinger L., Pachebat J., Glöckner G., Rajandream M., Sucgang R., Berriman M., et al. (2005). The genome of the social amoeba Dictyostelium discoideum. Nature 435 43–57. 10.1038/nature03481 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- El-Brolosy M., Stainier D. (2017). Genetic compensation: a phenomenon in search of mechanisms. PLoS Genet 13:e1006780. 10.1371/journal.pgen.1006780 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Emborg M. (2017). Nonhuman Primate Models of Neurodegenerative Disorders. ILAR J. 58 190–201. 10.1093/ilar/ilx021 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Esler W., Kimberly W., Ostaszewski B., Diehl T., Moore C., Tsai J., et al. (2000). Transition-state analogue inhibitors of g-secretase bind directly to presenilin-1. Nat. Cell Biol. 2 428–434. 10.1038/35017062 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fabritius A., Vesa J., Minye H., Nakano I., Kornblum H., Peltonen L. (2014). Neuronal ceroid lipofuscinosis genes, CLN2, CLN3 and CLN5 are spatially and temporally coexpressed in a developing mouse brain. Exp. Mol. Pathol. 97 484–491. 10.1016/j.yexmp.2014.10.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fernando S., Allan C., Mroczek K., Pearce X., Sanislav O., Fisher P., et al. (2020). Cytotoxicity and Mitochondrial Dysregulation Caused by α-Synuclein in Dictyostelium discoideum. Cells 9:2289. 10.3390/cells9102289 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ferrante R., Kowall N., Richardson E. (1991). Proliferative and degenerative changes in striatal spiny neurons in Huntington’s disease: a combined study using the section-Golgi method and calbindin D28k immunocytochemistry. J. Neurosci. 12 3877–3887. 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.11-12-03877.1991 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Francione L., Annesley S., Carilla-Latorre S., Escalante R., Pr F. (2011). The Dictyostelium model for mitochondrial disease. Semin. Cell Dev. Biol. 22 120–130. 10.1016/j.semcdb.2010.11.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gachet Y., Codlin S., Hyams J., Mole S. (2005). btn1, the Schizosaccharomyces pombe homologue of the human Batten disease gene CLN3, regulates vacuole homeostasis. J. Cell Sci. 118 5525–5536. 10.1242/jcs.02656 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gajdusek D. (1996). “Infectious amyloids: subacute spongiform encephalopathies as transmissible cerebral amyloidoses,” in Fields Virology 3 ed, eds Fields B., Knipe D., Howley P. (Philadephia: Lippincott-Raven Publishers; ), 2851–2900. [Google Scholar]

- Galter D., Westerlund M., Carmine A., Lindqvist E., Sydow O., Olson L. (2006). LRRK2 expression linked to dopamine-innervated areas. Ann. Neurol. 59 714–719. 10.1002/ana.20808 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gama Sosa M., De Gasperi R., Elder G. (2012). Modeling human neurodegenerative diseases in transgenic systems. Hum. Genet. 131 535–563. 10.1007/s00439-011-1119-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Getty A., Kovács A., Lengyel-Nelson T., Cardillo A., Hof C., Chan C.-H., et al. (2013). Osmotic Stress Changes the Expression and Subcellular Localization of the Batten Disease Protein CLN3. PLoS One 8:e66203. 10.1371/journal.pone.0066203 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Getty A., Pearce D. (2011). Interactions of the proteins of neuronal ceroid lipofuscinosis: clues to function. Cell Mol. Life Sci. 68 453–474. 10.1007/s00018-010-0468-6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gibson P., Tomlinson B. (1997). Numbers of Hirano bodies in the hippocampus of normal and demented people with Alzheimer’s disease. J. Neurol. Sci. 33 199–206. 10.1016/0022-510X(77)90193-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gitler A., Shorter J. (2011). RNA-binding proteins with prion-like domains in ALS and FTLD-U. Prion 5 179–187. 10.4161/pri.5.3.17230 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gorner K., Holtorf E., Waak J., Pham T., Vogt-Weisenhorn D., Wurst W., et al. (2007). Structural determinants of the C-terminal helix-kink-helix motif essential for protein stability and survival promoting activity of DJ-1. J. Biol. Chem. 282 13680–13691. 10.1074/jbc.M609821200 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gu Y., Sanjo N., Chen F., Hasegawa H., Petit A., Ruan X., et al. (2004). The presenilin proteins are components of multiple membrane-bound complexes that have different biological activities. J. Biol. Chem. 279 31329–31336. 10.1074/jbc.M401548200 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haass C., Kaether C., Sisodia S., Thinakaran G. (2012). Trafficking and proteolytic processing of APP. Cold Spring Harb. Perspect. Med. 2:a006270. 10.1101/cshperspect.a006270 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Halfmann R., Alberti S., Lindquist S. (2010). Prions, protein homeostasis, and phenotypic diversity. Trends Cell. Biol. 20 125–133. 10.1016/j.tcb.2009.12.003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Halfmann R., Jarosz D., Jones S., Chang A., Lancaster A., Lindquist S. (2012). Prions are a common mechanism for phenotypic inheritance in wild yeasts. Nature 482 363–368. 10.1038/nature10875 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Han R., Liang J., Zhou B. (2021). Glucose Metabolic Dysfunction in Nerodegenerative Diseases - New Mechanistic Insights and the Potential of Hypoxia as a Prospective Therapy Targeting Metabolic Reprogramming. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 22:5887. 10.3390/ijms22115887 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harris D. (1999). Cellular Biology of Prion Diseases. Clin. Microbiol. Rev. 12 429–44 10.1128/CMR.12.3.429 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hatano T., Kubo S., Imai S., Maeda M., Ishikawa K., Mizuno Y., et al. (2007). Leucine-rich repeat kinase 2 associates with lipid rafts. Hum. Mol. Genet. 16 678–690. 10.1093/hmg/ddm013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Henshall T., Tucker B., Lumsden A., Nornes S., Lardelli M. (2009). Selective neuronal requirement for huntingtin in the developing zebrafish. Hum. Mol. Genet. 18 4830–4842. 10.1093/hmg/ddp455 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Higashi S., Biskup S., West A., Trinkaus D., Dawson V., Faull R., et al. (2007). Localization of Parkinson’s disease-associated LRRK2 in normal and pathological human brain. Brain Res. 1155 208–219. 10.1016/j.brainres.2007.04.034 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hirano A. (1994). Hirano bodies and related neuronal inclusions. Neuropathol. Appl. Neurobiol. 20 3–11. 10.1111/j.1365-2990.1994.tb00951.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]