Abstract

Although the seed is a key morphological innovation, its origin remains unknown and molecular data outside angiosperms is still limited. Ginkgo biloba, with a unique place in plant evolution, being one of the first extant gymnosperms where seeds evolved, can testify to the evolution and development of the seed. Initially, to better understand the development of the ovules in Ginkgo biloba ovules, we performed spatio-temporal expression analyses in seeds at early developing stages, of six candidate gene homologues known in angiosperms: WUSCHEL, AINTEGUMENTA, BELL1, KANADI, UNICORN, and C3HDZip. Surprisingly, the expression patterns of most these ovule homologues indicate that they are not wholly conserved between angiosperms and Ginkgo biloba. Consistent with previous studies on early diverging seedless plant lineages, ferns, lycophytes, and bryophytes, many of these candidate genes are mainly expressed in mega- and micro-sporangia. Through in-depth comparative transcriptome analyses of Ginkgo biloba developing ovules, pollen cones, and megagametophytes we have been able to identify novel genes, likely involved in ovule development. Finally, our expression analyses support the synangial or neo-synangial hypotheses for the origin of the seed, where the sporangium developmental network was likely co-opted and restricted during integument evolution.

Subject terms: Developmental biology, Evolution, Plant sciences

Introduction

The seed, critical for the successful evolution and diversification of plants, is the salient synapomorphy of seed plants, but its origin and relationships amongst extant seed plant lineages remains unclear. The seed develops from an ovule that is composed of a megasporangium, conserved in land plants, covered by the integument(s), the defining step in seed evolution1. Historically, the evolution of the integuments, and therefore of the seed, is a subject that has aroused great interest from scientists, which has led to various proposals, including three major hypotheses that remain valid and which all have supporting paleontological and morphological evidence. (1) The “de novo” hypothesis, that states that the integument covering the sporangia appeared as a new structure2,3. (2) The “telome” hypothesis, supported by the fusion of integumentary lobes in the Palaeozoic ovules, suggesting that integuments are the result of the fusion of vegetative structures, telomes, around the sporangium4,5. (3) The “synangial” hypothesis, that proposes that integuments are the result of sterilization of sporangia around the only sporangium that remains functional6–8. Later, following evidence of the vascular traces of the Palaeozoic ovules, the synangial hypothesis was modified9, evidence that led to the ‘neo-synangial” hypothesis. Recent studies on anatomical development of ovules in Cycadales and the fossil record of Genomosperma kidstonii10,11, as well as molecular studies from Arabidopsis thaliana (Arabidopsis12) and Gnetum gnemon (Gnetum13) support the neo-synangial hypothesis.

The molecular mechanisms underlying seed development are widely known in angiosperms but for gymnosperms, data are rather scarce. Comparative molecular analyses of integument development between angiosperms and Ginkgo biloba (Ginkgo), provide essential data to better understand the origin and evolution of the seed. Known as a living fossil, the gymnosperm Ginkgo has remained morphologically unchanged since it evolved nearly 300 mya14 and constitutes one of the first extant plant lineages where seeds evolved14.

In Arabidopsis thaliana, three transcription factors are known to play an essential role in the initiation of the integuments by different mechanisms, AINTEGUMENTA (ANT), WUSCHEL (WUS) and BELL1 (BEL1)15–18. WUS in Arabidopsis, is required for the proper establishment of the chalaza promoting formation of the integuments. In fact, wus mutants do not develop integuments while overexpression of WUS results in supernumerary integuments16,17. Moreover, the expression of WUS in Arabidopsis is restricted to the nucellus activating a downstream signal derived from the nucellus, inducing organ initiation in the adjacent chalaza cells; WUS forms a short-range signaling module repeatedly during plant development16. WUS in Arabidopsis also regulates cell differentiation in anther development, and it is expressed in the pollen19. WUS function in the maintenance of stem cells appears to be conserved in core eudicots but not in monocots where it is essential in axillary meristem initiation20–24.

In angiosperms, ANT homologues act in the development of the two integuments, as well as in the control of leaf size25,26. The ant mutant in Arabidopsis, has smaller leaves, fewer floral organs, lacks integuments and megasporogenesis is blocked15,27–29. These pleiotropic roles of ANT in plant development are the result of its control over cell proliferation15. In angiosperm ovules, BEL1 homologues are restricted to the integument, and this pattern is conserved across angiosperms30,31. In Arabidopsis, this function, seems to be due to the interaction of BEL1 with the carpel identity dimer AGAMOUS-SEPATALLATA3 and to the repression of WUS towards the nucellus24. Another suggested genetic interaction, possibly related to BEL1 function in integument formation, is the repression of SPOROCYTELESS/NOZZLE (SPL/NZZ), a master regulator of nucellus-forming pathways upregulating PIN-FORMED 1 (PIN1) and WUS17,32.

Once integument development has started, multiple transcription factors come into play for the patterning of the integuments including Class III HD-Zips (C3HDZ or C3HD-Zip), KANADIs (KANs), and UNICORN (UCN). There are five Arabidopsis Class III HD–Zip genes: AtHB8, CORONA/AtHB15 (CNA), PHABULOSA (PHB), PHAVOLUTA (PHV), and REVOLUTA (REV)33–35; that are well known for their role in establishing the adaxial side of the leaf35. CNA, PHB, PHV and REV have been reported to be involved in the proper establishment of planar polarity of the integument, where they are expressed adaxially; and CNA, PHB and PHV are restricted to the inner integument17,36–39.

In Arabidopsis, KANs are responsible for specifying the abaxial identity of leaves and integument. KAN1 and KAN2, play a role in abaxial identity of the outer integument40–43. ABERRANT TESTA SHAPE (ATS) also known as KANADI 4 (KAN4), specifies the abaxial identity of the inner integument44. As for integument polarity, their function seems to be conserved across angiosperms as the same patterns are observed in the early diverging angiosperm, Amborella trichopoda45. In Arabidopsis, UCN is involved in the planar identity of the outer integument by controlling cell growth and repressing KAN446.

Phylogenetic analyses in land plants show that each of these genes has undergone multiple independent duplication events47–50. In gymnosperms, these genes have been studied in Gnetum species, GgWUS, is expressed in the nucellus, similarly to angiosperms (Nardmann et al.48). ANT, GneANT, is expressed in the integument as well as in the nucellus; Melbel1, BEL1 homolog in Gnetum is restricted to the nucellus13. Interestingly, the KAN and UCN homologs are mainly restricted to the apical portion of the Gnetum integument13. Our results of spatiotemporal expression analyses for WUS, ANT, BEL1, KANs, Class III HD-Zips, and UCN homologues in Ginkgo show that changes in their expression patterns in seed plants, may be linked to major developmental differences. The transcriptome analyses we performed to identify differentially expressed genes, revealed putative candidate genes for Ginkgo integument development. One of these candidate genes is FANTASTIC FOUR (FAF), a plant-specific gene family, characterized in Arabidopsis for its role in meristem development and its interaction with WUS51. In Ginkgo, expression of FAF is restricted to the integument, suggesting a role in Ginkgo ovule development. Moreover, the results from the expression analyses provide molecular evidence supporting the hypotheses that the ovule evolved from sterilization and fusion of sporangia6,9.

Results

Expression analyses of WUSCHEL homologues in Ginkgo: GbWUS

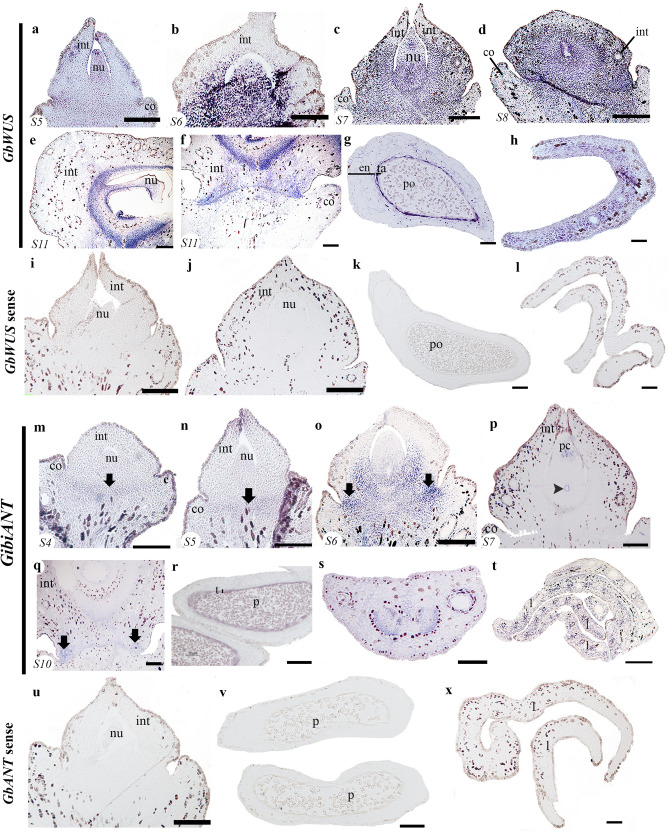

The development of the Ginkgo ovule has been divided into 11 stages (stage = S; Fig. S1)52. When the integument overtops the nucellus (S5), GbWUS is strongly expressed in the nucellus and in a layer of cells known as the abscission zone of the ovule, that is between the ovule base and the collar, a region from which the ovule will detach from the plant when the seed is fully mature (Fig. 1a). Its expression is also detected in the integument, which already covers the nucellus (Fig. 1a). During S6, before the ovule is fertilized, GbWUS is strongly expressed in the nucellus and the base (proximal region) of the integument (known as pachychalazal region) as well as in the abscission zone (Fig. 1b). At pre-pollination S7, GbWUS expression is maintained in the proximal region of the nucellus, and the integument (in the pachychalaza region). No GbWUS expression is detected in the apical region of the integument, which forms the micropyle (Fig. 1c). These expression patterns are maintained as the ovule matures to S8. However, no expression is detected in the collar (Fig. 1d). Later on, in S11, GbWUS expression is detected in the inner side of the integument corresponding to the endotesta, nucellus, jacket cells and in the proximal region of the ovule in the abscission zone (Fig. 1e,f). GbWUS is also expressed in nearly mature pollen grains and the tapetum (Fig. 1g) and also in the young but well-developed leaves (Fig. 1h). No signal was detected with a GbWUS sense probe (Fig. 1i–l).

Figure 1.

Expression of GibiWUS and GibiANT using in situ hybridization. (a–h) GibiWUS expression patterns. (a) Ovule in stage 5 (S5). (b) Ovule in stage 6 (S6). (c) Ovule in stage 7 (S7), pollination stage. (d) Ovule in stage 8 (S8). (e) Ovule in stage 11 (S11). (f) Close-up of the abscission zone of the same ovule at stage 11 (S11). (g) Expression in the pollen cone. (h) Cross section of a leaf. (i–l) GbWUS sense probe. (m–t) GibiANT expression patterns. (m) Ovule in stage 4 (S4). (n) Ovule in stage 5 (S5). (o) Ovule in stage 6 (S6). (p) Ovule in stage 7 (S7). (q) Ovule in stage 10 (S10). (r) Microsporangium. (s) Petiole of the leaf. (t) Cross section of the leaf. (u–x) GbANT sense prone. The corresponding stage (S) is shown at the bottom left of each picture. Black arrows pointing to the abscission zone; black arrowheads pointing to the megaspore mother cell; co collar, en endothelium, int integument, nu nucellus, po pollen, ta tapetum. Scales: 50 μm (a,e–n,q,r); 75 μm (b,k,l,s,t); 100 μm (c,d).

Expression analyses of ANT Ginkgo homologues: GibiANT

GibiANT expression was consistent throughout ovule development. In S4 and S5 of ovule development, the expression of GibiANT is limited to the region which will become the abscission zone of the ovule (Fig. 1m,n). It is also found at the distal end of the integument, which will form the micropyle (Fig. 1n). When the development of the megaspore mother cell begins, at S6, GibiANT is expressed in the chalazal region, and particularly in the abscission zone towards the region close to the collar (Fig. 1o). In S7, once the nucellus and the megaspore mother cell are well formed, the expression of GibiANT is also detected in the jacket cells and in the pollen chamber (Fig. 1p). Later, in S10, GibiANT expression is maintained in the abscission zone laterally, close to the collar (Fig. 1q). GibiANT is expressed in the tapetum of the pollen cone and in the nearly mature pollen grains (Fig. 1r). Furthermore, GibiANT has been found widely expressed in the vegetative tissue, in the petiole of the leaf, the young leaves and the vascular bundles (Fig. 1s,t). No signal was detected with a GibiANT sense probe (Fig. 1u–x).

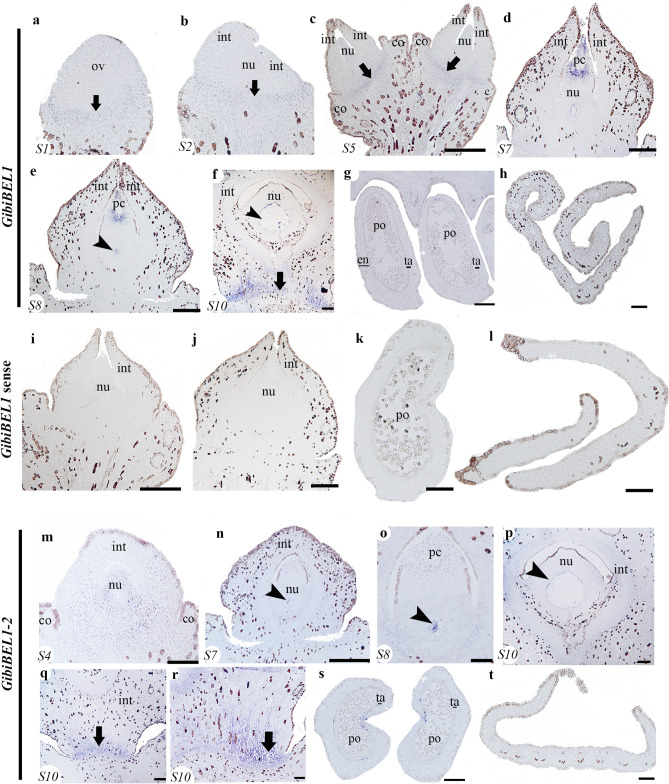

Expression analyses of BELL1 Ginkgo homologues: GibiBEL1 and GibiBEL1-2

Expression analyses of the two BELL1 homologues, GibiBEL1 and GibiBEL1-2, in developing ovules show restricted expression patterns for each copy. At S1 and S2, GibiBEL1 is expressed at the base of the ovule (Fig. 2a,b). At S5, GibiBEL1 is expressed in the abscission zone (Fig. 2c). At S7, when the ovule is competent for fertilization, GibiBEL1 is detected in the pollen chamber (Fig. 2c) and at S8, in the megaspore mother cell and jacket cells once they have formed (Fig. 2d,e). At S10, GibiBEL1 is strongly expressed in the abscission zone, and detected in the nucellus and endotesta cells of the integument (Fig. 2f). No GibiBEL1 expression was found in the young developing pollen cone or in the blade of the young leaf (Fig. 2g,h). No signal was detected with a GibiBEL1 sense probes (Fig. 2i–l).

Figure 2.

Expression of BEL1 homologues using in situ hybridization. (a–h) Expression patterns of GibiBEL1. (a) Ovule in stage 1 (S1). (b) Ovule in stage 2 (S2). (c) Ovule in stage 5 (S5). (d) Ovule in stage 7 (S7). (e) Ovule in stage 8 (S8). (f) Stage 10 (S10), close-up of the abscission zone. (g) Pollen cone. (h) Cross section of the leaf. (i–l) GibiBEL1 sense probe as control. (m–t) Expression patterns of GibiBEL1-2. (m) Ovule in stage 4 (S4). (n) Ovule in stage 7 (S7). (o) Close-up of the nucellus of an ovule in stage 8 (S8). (p) Close-up of the nucellus of an ovule at stage 10 (S10). (q,r) Abscission zone of the ovule in stage 10 (S10). (s) Microsporangia. (t) Cross section of a leaf. The corresponding ovule stage (S) is shown at the bottom left of each picture. Black arrows pointing to the abscission zone; black arrowheads pointing to the megaspore mother cell; co collar, en endothelium, int integument, nu nucellus, po pollen, ta tapetum. Scales: 50 μm (c,d,i,j,l,r,t); 75 μm (e,k,n,o); 100 μm (f–h,p–s).

Unlike GibiBEL1, GibiBEL1-2 is expressed in the nucellus from the early stages of ovule development (S4; Fig. 2m) with this expression restricted to the megaspore mother cell, once it develops (S7–8; Fig. 2n,o). GibiBEL1-2 is also expressed in the jacket cells (S10, Fig. 2p) and in the abscission zone (Fig. 2q,r). No expression was detected in the pollen cones or the leaves (Fig. 2s.t).

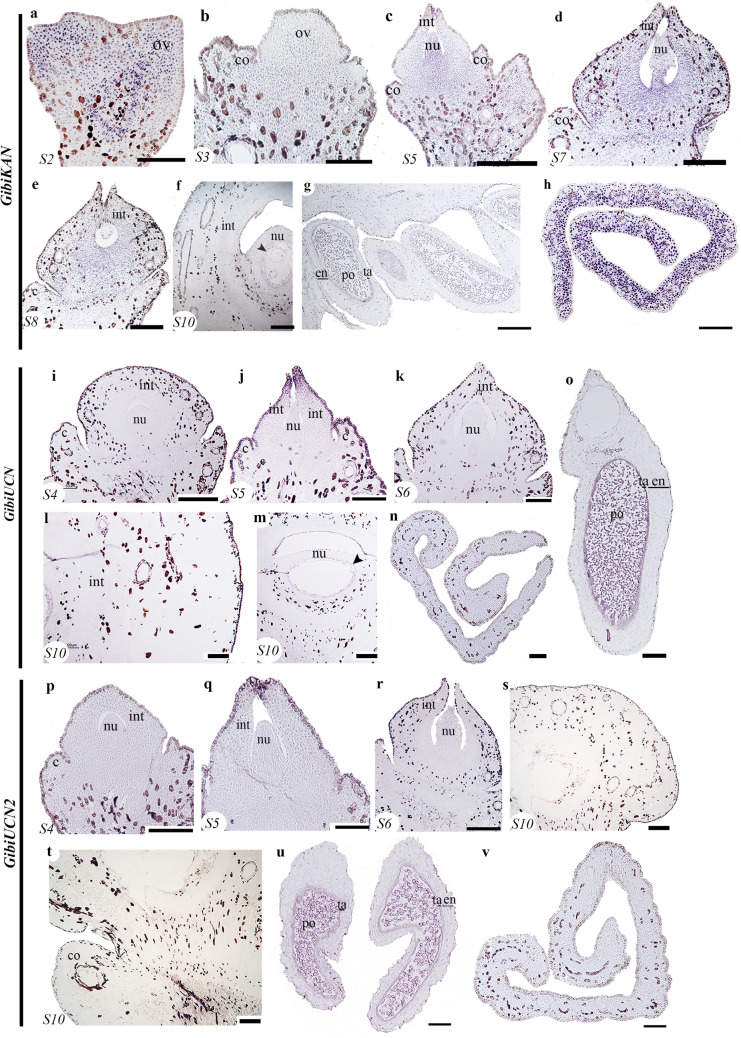

Expression analyses of Ginkgo homologues GibiKAN, GibiUCN, GibiUCN2 and GbC3HDZs

Initially, in S2, GibiKAN is expressed throughout the ovule primordia and the funiculus (Fig. 3a). Later, at S3, GibiKAN is expressed in the region that will become the nucellus (Fig. 3b) and it is maintained as the nucellus develops, 5 (Fig. 3c). At this stage GibiKAN is also expressed in the apical region of the integument (Fig. 3c). In S7 and 8, GibiKAN is also expressed in the integument when the integument begins to close the micropyle (Fig. 3d,e). These expression patterns in the integument and nucellus are maintained, and additional expression is detected in the jacket cells at S10 (Fig. 3f). GibiKAN is also expressed in microspores and pollen grains (Fig. 3g). In vegetative tissues, GibiKAN is highly expressed throughout leaf development and its expression does not appear polar (Fig. 3h). Sense probes show no expression (Fig. S10).

Figure 3.

Expression patterns of GibiKAN, GibiUCN and GibiUCN2 using in situ hybridization. (a–h) GibiKAN expression patterns. (a) Ovule in stage 2 (S2). (b) Ovule in stage 3 (S3). (c) Ovule in stage 5 (S5). (d) Ovule in stage 7 (S7). (e) ovule in stage 8 (S8). (f) Ovule in stage 10 (S10). (g) Pollen cone. (h) Cross section of the leaf. (i–o) GibiUCN expression patterns. (i) Ovule in stage 4 (S4). (j) Ovule in stage 5 (S5). (k) Ovule in stage 6 (S6). (l) Integument of an ovule in stage 10 (S10). (m) Megagametophyte of an ovule in stage 10 (S10). (n) Cross section of a leaf. (o) Microsporangium. (p–v) GibiUCN2 expression patterns. (p) Ovule in stage 4 (S4). (q) Ovule in stage 5 (S5). (r) Ovule in stage 6 (S6). (s,t) Ovule in stage 10 (S10). (u) Microsporangium. (v) Cross section of the leaf. The corresponding ovule stage (S) is shown at the bottom left of each picture. co collar, en endothelium, int integument, nu nucellus, po pollen, ta tapetum. Scales: 50 μm (a,b,f,i,l–n,p,s–v); 75 μm (c–e,q,r); 100 μm (g,j,k,o).

The two UNICORN homologues, GibiUCN and GibiUCN2, show low levels of expression throughout ovule development (Fig. 3i–t). As the integument becomes distinct from the nucellus, GibiUCN is specifically expressed in the apical region of the integument forming the micropyle (Fig. 3j). Both paralogues are strongly expressed in the tapetum and in the nearly mature pollen grains (Fig. 3o–u). We did not detect expression of either homologue in the blade of young leaves (Fig. 3n,v). Sense probes show no expression (Fig. S10).

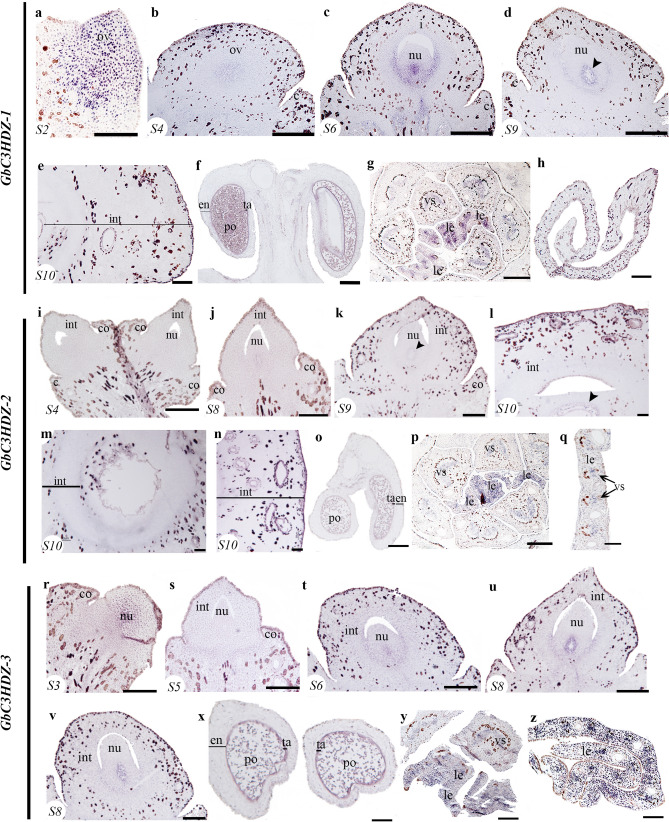

From the five paralogues identified for the C3HDZip genes in Ginkgo, GbC3HDZ1 to 549, we were able to assess the expression of four paralogs GbC3HDZ1 to 4 (Fig. 4, Supplementary Fig. S11). At S2, GbC3HDZ1 is expressed in the ovule primordia (Fig. 5a); and in S4 and S6, in the young developing nucellus (Fig. 4b,c) specifically in the region where the megaspore will develop (Fig. 4c). GbC3HDZ1 is expressed in the adaxial side of the integument, in the region that delimits the integument and nucellus (Fig. 4c). This expression is maintained in the adaxial side of the integument and in the jacket cells, S9 (Fig. 4d). At S10, in the fleshy integument, we did not detect expression of GbC3HDZ1 (Fig. 4e), but it is expressed in the tapetum of the microsporangium and in the nearly mature pollen grains (Fig. 4f). GbC3HDZ1 is detected in the leaf and petiole vasculature and appears adaxial in young developing leaves (Fig. 4g). GbC3HDZ1 is not detected in the blade of well-developed leaves (Fig. 4h). GbC3HDZ1 sense probes show no expression (Fig. S10).

Figure 4.

Expression patterns of three C3HDZs homologues. (a–h) Expression patterns of GbC3HDZ-1. (a) Ovule in stage 2 (S2). (b) Ovule in stage 4 (S4). (c) Ovule in stage 6 (S6). (d) Ovule in stage 9 (S9). (e) Integument of an ovule in stage 10 (S10). (f) Microsporangium, showing expression in the pollen grains and tapetum. (g) Cross section of a short shoot with leaf primordia in the center. (h) Cross section of a well-developed leaf. (i–q) Expression patterns GbC3HDZ-2. (i) Ovules in stage 4 (S4). (j) Ovule in stage 8 (S8). (k) Ovule in stage 9 (S9). (l,m) Ovule in stage 10 (S10). (o) Microsporangia. (p) Cross section of a short shoot with leaf primordia in the center. (q) Cross section of a well-developed leaf. (r–z) Expression patterns GbC3HDZ-3. (r) Ovule in stage 3 (S3). (s) Ovule in stage 5 (S5). (t) Ovule in stage 6 (S6). (u) Ovule in stage 8 (S8). (v) Ovule in stage 9 (S9). (x) Microsporangia. (y) Cross section of a short shoot with leaf primordia in the center. (z) Cross section of a leaf. Black arrowheads pointing to the megaspore mother cell; co collar, en endothelium, int integument, le leaf, nu nucellus, po pollen, ta tapetum, vs vasculature. Scales: 50 μm (a,b,i,j,r–t); 75 μm (c,e–g,k,p,u,v,y); 100 μm (d,h,l–o,q,x,z).

Figure 5.

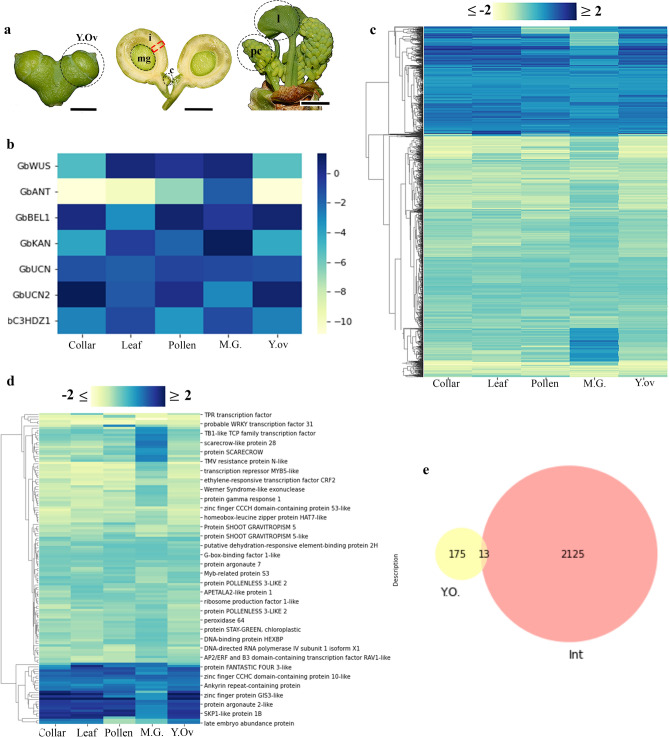

Transcriptome results focused on integument development. (a) Ginkgo samples that were sequenced separately to perform the differential expression analyses. Red square indicates the integument. (b) Heatmap of the genes from the integument developmental network differentially expressed in the integument. (c) Cluster map throughout all the tissues compared to the integument, 2137 Differentially Expressed (DE) genes with a fold expression change between − 2 and 2 and good transcriptional support (TPM ≥ 0.95). Each column of the cluster map indicated the twofold changes of each sample with respect to the integument. (d) 134 DE transcription factors differentially expressed in the integument compared to all the other samples. Two clusters were identified that largely consisted of up-regulated (blue clusters, n = 21) and down-regulated genes (yellow, n = 97). (e) Comparison of the DE genes between the young ovule sample and the integument. (f) Comparison of the DE genes between the megagametophyte and the integument. Blue, upregulated genes and yellow, downregulated genes (b–d).

In ovules at S4, no expression of GbC3HDZ2 was detected (Fig. 4i) but in S8, as soon as the megaspore and the jacket cells start to develop, expression is detected (Fig. 4j). This expression is maintained as the ovule matures, S9 (Fig. 4k). Later, at S10 after pollination, GbC3DZ2 is found expressed in the jacket cells (Fig. 4l,m) and throughout the fleshy seed coat (Fig. 4n). GbC3DZ2 expression is detected in the tapetum and the nearly mature pollen grains (Fig. 4o) and in young developing leaves (Fig. 4p) becoming restricted to the vascular bundles and the adaxial side of the well-developed leaves (Fig. 4q).

GbC3HDZ3 is expressed similarly to GbC3HDZ1 in the young developing nucellus (Fig. 4r), the jacket cells, the tissue that will form the megaspore, the adaxial side of the integument in the region in close contact with the nucellus (Fig. 4t–v), in the tapetum and pollen grains (Fig. 4x), and throughout the vegetative tissue including vascular bundles (Fig. 4y,z). GbC3HDZ4 is expressed at S11 in well-developed ovules in the inner region of the integument, the endotesta (Fig. S11a–e) and the pollen grains (Fig. S11f). No expression of GbC3HDZ4 is detected in the leaf (Fig. S11g).

Transcriptome assembly

A de novo reference transcriptome of Ginkgo was generated from RNAs isolated from young ovule (S4), integument, megagametophyte, collar (dissected from ovules in S9), pollen cone and leaf. Using Trinity software 86,050 transcripts were obtained, with an average GC content of 41.52% and a maximum assembled contig length of 18,726 bases. To improve the quality of the assembly, the contigs were mapped to the initial assembly with ABySS. This gives a final total of 53,970 transcripts (Table 1). Based on read coverage, the E90N50 statistic was ~ 1.8 Kb (Fig. S6), the reference transcriptome contained 86.9% of the conserved Embryophyte genes using BUSCO annotation (Fig. S7).

Table 1.

Statistics for Ginkgo reference transcriptome.

| Parameter | Number |

|---|---|

| Ginkgo reference transcriptome | |

| Total trinity transcripts | 86,050 |

| Total trinity ‘genes’ | 46,636 |

| %GC | 41.52 |

| Longest contig (bp) | 18,726 |

| shortest contig | 201 |

| Number of contigs > 200 bp | 86,050 |

| Number of contigs > 1 Kb | 46,316 |

| Number of contigs > 5 kb | 2488 |

| Number of contigs > 10 Kb | 117 |

| Number of predict ORFs (transdecoder) | 67,040 |

| Stats after re-assembly with AbySS | |

| Total transcripts after re-assembly AbySS | 53,970 |

| Contigs longer than 200 | 36,979 |

| Contigs longer than 1 kb | 14,685 |

| Contigs longer than 5 kb | 364 |

| Contigs longer than 10 kb | 17 |

| Number of predict ORFs (transdecoder) | 36,979 |

The initial assembly was improved with a re-assembly method using AbySS.

Samples were compared with a Principal Component Analysis (PCA), which shows that the integument and the megagametophyte are the most dissimilar samples in the data set in terms of gene expression (Fig. S8a). A hierarchical cluster analysis was performed to better understand the similarities within samples. The resulting dendrogram shows that the integument is the most distinct sample with longer branch distance (Y-axis) but it is more similar to the megagametophyte (Fig. S9). Collar, leaf, pollen cone, and young ovules form another cluster (Fig. S9).

Differentially expressed genes in the integument of Ginkgo

To identify genes that are differentially expressed (DE) in the integument of Ginkgo, transcriptome analyses were performed in different plant tissues (i.e., young ovules, integument, megagametophyte, collar, pollen cone, and leaf; Fig. 5a, Table S1). Differentially expressed genes in the integument were filtered by statistical significance (FDR p ≤ 0.05) and a comparison of all tissues against integument was performed. We found that most of the DE genes, that belong to the ovule genetic network seem to be similarly upregulated in all tissues except for GibiANT (Fig. 5b). Subsequently, to focus on genes with a larger change (log2FC ≤ − 2 and ≥ 2), we added a Fold Change threshold which detected 2137 DE genes (Fig. 5c). None of the genes in the ovule regulatory network passed this filter.

Transcription factors differentially expressed in integument

We focused our transcriptome analyses on transcription factors (TF) which are known to control transcription levels and act as major developmental switches. 134 DE genes were detected as TF and the differential expression of each of these TF within tissues was also compared (Fig. 5d). Of these TFs, compared to other tissues, 21 are found to be largely upregulated in the integument (Table S2) and there are 97 down regulated transcription factors (Table S3). By comparing the results of the samples of young ovules (Fig. S10) and integument, we detected genes that are expressed throughout integument development (from early stages of the ovule to the mature integument) suggesting that there are 13 throughout integument development (Fig. 5e, Table S4).

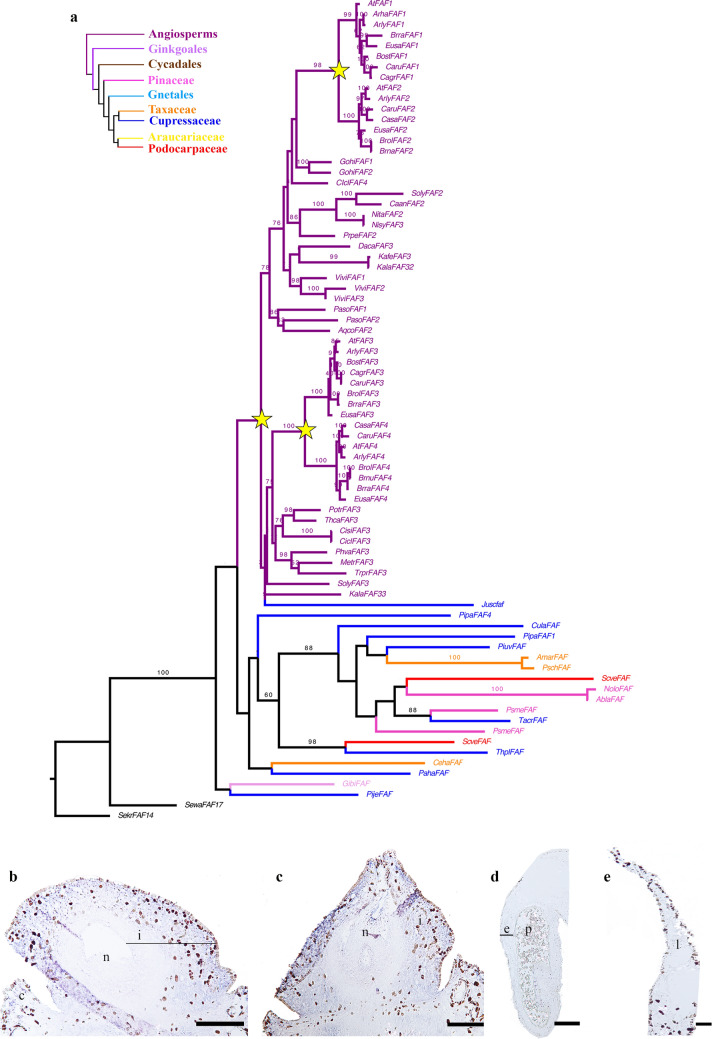

Differentially expressed FANTASTIC FOUR homologues

Among the 21 transcription factors upregulated in the integument, the FANTASTIC FOUR (FAF) gene family stood out as they are known to repress WUSCHEL genes in Arabidopsis45. To understand the relationships among these transcripts, a detailed phylogenetic analysis of this family of transcription factors was performed. We were able to identify one sequence as a FAF homologue, referred herein as GibiFAF (Fig. 6a). We identified a duplication event occurred before the diversification of angiosperms giving rise to clades FAF1/2 and FAF3/4. In addition, two Brassicaceae-specific duplication events were detected in each clade, resulting in the clades FAF1, FAF2, FAF3 and FAF4 respectively (Fig. 6a). With expression studies in Ginkgo, we found that GibiFAF expression is restricted to the integument throughout S4 to S9 of ovule development (Fig. 6b,c). GibiFAF does not appear to be expressed in the pollen cones or leaves (Fig. 6d,e).

Figure 6.

FANTASTIC FOUR gene family evolution and expression in Ginkgo. (a) Maximum Likelihood (ML) analysis for FAF homologues across seed plants. Yellow stars indicate the three large scale duplication events detected. One before the diversification of angiosperms giving rise to the clades FAF1/2 and FAF3/4. And each clade has undergone one more duplication specific to Brassicaceae. (b–e) In situ hybridization for GibiFAF. (d) Pollen cone. (e) Leaf. e endothelium, i integument, l leaf, n nucellus, p, pollen. Scales: 75 μm (a,b); 100 μm (d,e).

Discussion

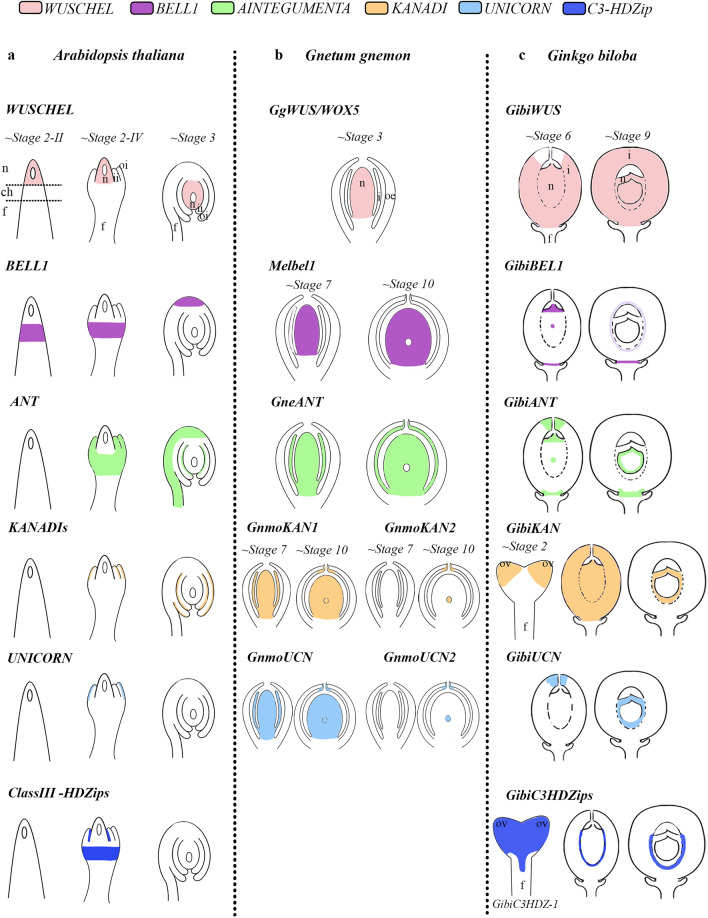

Unlike angiosperms, in Ginkgo, we found that the expression patterns of the WUS homologue is not only in the nucellus but also in the integument, pollen cone, and leaf (Fig. 1a–h). In gymnosperms, the Gnetum homologue (GgWUS/WOX5), exhibits expression patterns like those of monocots, in lateral organ primordia, as well as in the nucellus48. In the fern Ceratopteris richardii, CrWOXB a WUS-RELATED homeobox promotes cell divisions in the gametophytic generation and organ development in the sporophytic generation53. In land plants, all members of WOX gene lineage are mainly known for their function in meristem identity20–22,54. However, GbWUS expression is found in the basal region of the integuments. In Ginkgo ovules, the expression patterns we detected could be associated with the meristematic activity of the pachychalaza region of the ovule (Fig. 1a–f). Shifts in the expression patterns of this gene lineage in seed plants may be linked to major morphological differences or to changes in the cis-regulatory regions, as the protein sequence seems highly conserved in seed plants55.

We did not find GibiANT expression in young developing integuments. However, the expression pattern of ANT varies in ovules of different gymnosperms lineages. In gymnosperms Pinus thumbergii, and Gnetum parvifolium, expression analyses in young developing ovules show expression in the nucellus and integument47. In Gnetum gnemon and Ginkgo (Fig. 1m–t), expression is detected only in the micropyle at a pre-pollination stage (Fig. 1n)13. ANT in the fern Ceratopteris richardii, CerANT, is expressed in the sperm, in the archegonial neck canal just before fertilization (gametophyte structure), and in the fertilized egg, (i.e., the zygote), and in the fiddlehead (sporophyte)56. The expression detected in the pollen grains, suggests that ANT homologues were retained in gymnosperms as key factors in the development of the mega and the microspores, gametophyte development, similar to what is found in ferns (Fig. 1i,n). Overall, the ancestral function of ANT seems to be in cell division as it is present in active cell division regions and in young developing tissue throughout land plants47,56.

In Ginkgo, we found GibiBEL1 and GibiBEL1-2 expressed in megaspore and pollen grains (Fig. 2) similar to expression of the only Gnetum gnemon homologue, Melbel1, detected in the nucellus13. Loss of function of PpBELL1 in Physcomitrella patens moss generates bigger egg cells unable to form embryos, suggesting that BELL1 has been key in facilitating the diversification of land plants (embryophytes57). This suggests that BEL function in the proper formation of the spores, may be conserved in mosses and gymnosperms (Fig. 2)57. Notably, BEL1 in Ginkgo and Gnetum gnemon have distinct expression patterns in the nucellus (Figs. 2b–d, 7)13. These results allow us to infer that the function of BEL1 homologues in the development of the egg cell is probably conserved in early land plants: bryophytes and gymnosperms (Fig. 2)57. However, this function does not seem to be conserved in angiosperms, suggesting major changes in the functional evolution of the BELL1 gene lineage have occurred, following a duplication event before the diversification of angiosperms50. Interestingly, there are complementary expression patterns of GibiBEL1 in the distal region and GibiWUS in the proximal region of the nucellus at S8 (Figs. 1d, 2e).

Figure 7.

Schematic representation of the expression patterns of integument development genes, in three different species. (a) Arabidopsis thaliana (WUS by Grobeta-Hardt16; BELL1 by Robinson-Beers et al.58; ANT by Elliot et al.15; KAN by Leon-Kloosterziel et al.44; Eshed et al.40; UCN by Enuguttii et al.59). (b) Gnetum gnemon previously published (WUS by Nardmannn et al. 2009; Melbel1, GneANT, GnmoKANs and GnmoUCNs by Zumajo-Cardona and Ambrose19). (c) Ginkgo results presented here. (d) Illustration of telome theory, synangial hypothesis and neo-synangial hypothesis for the origin of the seed. Notably, the telome theory indicates the evolution of integuments from sterile structures while both the synangial and neo-synangial hypotheses indicate the evolution of integuments from fertile (sporangia) structures.

We did not find any polar (abaxial) expression of GibiKAN in Ginkgo ovules in particular (Fig. 3a–h). KAN genes are expressed in the micropylar region of the integument in gymnosperms, suggesting differences in the proximal–distal development of these ovules compared to angiosperms (Fig. 3a–h)13. In the lycophyte Selaginella moellendorffii, three KAN specific homologues are expressed throughout sporangium development60. The expression patterns in the megaspore are conserved between S. moellendorffii and gymnosperms. KAN genes are generally known for their function in establishing abaxial organ polarity in land plants37,40–42. This function is likely conserved in ferns60 and in monocot homologues61,62. This allow us to hypothesize that the ancestral function of KAN genes is in the development of the sporangium and that this function is conserved in lycophytes and gymnosperms.

It seems that the abaxial–adaxial polarity function is not conserved in the integument of gymnosperms as UCN homologues are expressed only in the nucellus and apical portion of the integument. Intriguingly, both UCN and KAN homologues in Gnetum gnemon and in Ginkgo, are expressed in the tips of the integuments which suggesting: (1) the interaction between UCN and KAN may be conserved in this region; (2) their function in gymnosperms may be more in establishing the proximal–distal axis; and (3) this indicates major developmental differences between gymnosperm and angiosperms ovules (Fig. 3i–u)13,45.

Interestingly, GbC3HDZ1 and 3 are also expressed in the adaxial side of the integument, likely involved in the separation of the nucellus and integument in the pachychalazal region (Fig. 4, Supplementary Fig. S9). Notably, GbC3HDZ1 and 3 expression is not only adaxial in the integument but also at the base of the ovule. In Ginkgo, previous studies revealed expression in the leaf primordia63 (Fig. 4g,p,y). C3HD-Zip homologues are expressed in the sporangia of the lycophyte Selaginella moellendorffii and the fern Psilotum nudum49. In vascular plants C3HD-Zips are involved in vasculature development, also observed here in the stalk49. However, the ovules of Ginkgo are not vascularized (Fig. 4, Supplmentary Fig. S9). The data available so far suggests that sporangia development could be the ancestral function of this gene lineage49.

The main sources of diversity and changes underlying evolution are alterations in the expression of genes encoding transcriptional regulators64. We focused on differentially expressed (DE) genes annotated as transcription factors (Fig. 5c,d, Tables S3, S4, Fig. S8)65.

We have identified a gene upregulated in the integument transcriptome related to the FANTASTIC FOUR (FAF; Fig. 6a), a plant-specific gene family with four paralogues in Arabidopsis: FAF1 to 451 (Table S2). FAF1 and 2 proteins, are known for their ability to regulate the size of the shoot apical meristem and expression in the embryo (Fig. S12)51; this function in the meristem is linked to its ability to repress WUS51. Our Maximum Likelihood analysis shows that there are three duplication events. One before the diversification of all angiosperms giving rise to two clades: FAF1/2 and FAF3/4 corresponding to a whole genome duplication (WGD) event ε66. In addition, there is a Brassicaceae-specific duplication event in each of these clades that corresponds to the α and β WGD events specific to Brassicales66. Gymnosperms are pre-duplication homologues (Fig. 6a). Our expression analyses in Ginkgo indicate that GibiFAF is expressed at higher levels in the integument (Fig. 6b,c) and neither in the pollen cone nor in the leaf (Fig. 6d,e) corroborating the analysis of DE genes (Fig. 6d). It is not yet clear whether FAF directly represses WUS in Arabidopsis as their expression overlaps, but, GibiFAF and GibiWUS expression only overlap in the integument of Ginkgo (Figs. 1, 6) suggesting that, GibiFAF is likely a novel regulator of integument development in Ginkgo. To determine if this function is conserved in other species, further studies are needed.

Beyond understanding morphological and developmental patterns of Ginkgo ovule, our results also provides molecular evidence on the origin of the seed.

Expression patterns do not appear to be wholly conserved between angiosperms and gymnosperms (Fig. 7), but the main function of the gene(s) may be conserved. The expanded expression of GbWUS, at base of the ovule and in the basal portion of the integument, indicates that this region has persistent meristematic function. GbWUS expression, additionally, provides molecular support for the interpretation of Ginkgo integument as pachychalazal, where the chalaza domain extends upward from base of the ovule. The expression of GbC3HDZ1 in the adaxial basal region of the integument, indicates that its role in repressing the meristematic activity of GbWUS12 may have occurred early during the evolution of the seed.

GibiFAF expression indicates that it is a novel gene involved in pachychalazal and integument development. In Arabidopsis, FAF homologs are expressed in the shoot apical meristem and interact with WUS51. Therefore, GibiFAF and GbWUS in the integument supports this tissue as an expanded meristematic region. Further analyses in Arabidopsis are needed to determine the role, if any, of FAF homologues in Arabidopsis seed development.

A distinct apical-basal expression pattern is present in gymnosperms. In Ginkgo and Gnetum, BEL1 (GibiBEL1, GibiBEL1-2, Melbel1) is restricted to the chalaza, while WUS and C3HDZ1 are in the basal part of the integument; ANT is expressed transiently in the basal portion of integument; and KAN and UCN are restricted to the apical portion of the integuments, unlike what is observed in angiosperms.

Heterochrony may have played a key role in ovule developmental processes (Table S5)67. BEL1 and KAN expression in Ginkgo and Gnetum ovules, are expressed comparably in the nucellus at the sporogenous stage (Fig. 7, Table S5), however, in Gnetum, it occurs prior to pollination, whereas in Ginkgo it occurs during pollination

Molecular analyses available in land plants show that integument genes are expressed during sporangia development (in lycophytes, ferns, Ginkgo and Gnetum) suggesting that the integument developmental network was co-opted from a sporangia development network.

The outcomes of these studies, together with recent molecular studies, provide additional molecular evidence supporting the synagial/neo-synangial hypotheses, by showing the expression patterns of integument genes in both micro- megasporangium and in the apical region of the integument of Gnetum and Ginkgo12,13. Indeed, the data available to date, suggests, that the sporangia development genes were co-opted for the development of the integument and that the integuments have evolved according to the synangial/neo-synangial hypothesis.

It is enticing to speculate that apical-basal expression patterns reflect the integumentary lobes envisioned in the neo-synangial hypothesis. With WUS in the base of the integument and the nucellus, it is not clear what mechanism accounts for the sterile integument. Recent reports suggest this could be due to BEL1 repression of SPL/NZZ12. Future studies of SPL/NZZ homologues in gymnosperms could provide further molecular support for the synangial/neo-synangial origin of the seed.

Methods

Expression analyses by in situ hybridization

The WUSCHEL homologue was previously identified with phylogenetic analysis42 (GenBank accession number: FM882128). Other homologues were identified with a BLAST amino acid search using Arabidopsis sequences as query (Table S6). Ginkgo sequences were identified from the OneKP database (Table S6; https://db.cngb.org/onekp). A BLAST search was performed in the genome as well, but no hits were retrieved (PLAZA database: https://bioinformatics.psb.ugent.be/plaza/versions/gymno-plaza/). The relationships of these sequences were previously shown with maximum likelihood analyses13,50. There are five homologues of Class III HD-Zip (C3HDZ) genes in Ginkgo, which have been previously reported49. However, the synthesis of the probe for one of the paralogues, GbC3HDZ5 was not effective; thus, we will present results for GbC3HDZ1 to 4.

Plant material was collected from the NYBG grounds (Accession number: 1353/97) and immediately fixed in FAA (FAA; 3.7% formaldehyde: 5% glacial acetic acid: 50% ethanol). Our characterization of the expression patterns begins around S4 of ovule development for most of these genes (i.e., GbWUS, GibiANT, GibiBEL1-2, GibiUCN, GibiUCN2, and GbC3HDZ2 and 3). This is because collection of ovules at early stages is highly variable as they are covered by the bracts of the short shoots. Only GibiBEL1, GibiKAN and GbC3HDZ1 were assessed starting at S2. After a 4-h incubation in FAA, samples were dehydrated in a standard ethanol series, then transferred to fresh Paraplast. The samples were sectioned on a Microm HM3555 rotary microtome. DNA templates for RNA probe synthesis were obtained by PCR amplification of 280–480 bp fragments. To ensure specificity, the probe templates were designed outside of conserved domains (Fig. S2, Table S7). Sense probes were used as negative controls. The fragments were cleaned using QIAquick PCR purification Kit (Qiagen, Valencia, CA, USA). Digoxigenin labeled RNA probes were prepared using T7 polymerase (Roche, Switzerland), murine RNAse inhibitor (New England Biolabs, Ipswich, MA, USA) and RNA labeling mix (Roche, Switzerland) according to the protocol of each manufacturer. The RNA in situ hybridization was performed according to Ambrose et al.68. Sections were digitally photographed using a Zeiss Axioplan microscope equipped with a Nikon DXM1200C camera.

Collection of plant material for RNAseq and extraction of total RNA from Ginkgo

A total of six different samples of Ginkgo were collected in liquid nitrogen from the NYBG grounds (Accession number: 1353/97), then processed for sequencing with three biological replicates each; thus, young ovules (ovules at S4), collar, integument, megagametophyte (from ovules at S9), pollen cone and leaf were dissected (total of 18 samples sequenced). The tissues were ground with liquid nitrogen; total RNA from these samples was extracted using QIAGEN RNeasy Kit (QUIAGEN) with a modification using extraction buffer consisting of 2% Polyvinlypolypyrrolidone (PVP, 111.14 g/mol), and 4% β-mecarptoethanol (BME; Wang et al., 2005).

Illumina sequencing and de novo transcriptome assembly

Quality of RNA samples was assessed using Qubit® 2.0 (ThermoFisher Scientific) and Agilent Technologies 2100 Bioanalyzer. Only samples with RNA Integrity Number (RIN) ≥ 8 were used to prepare sequencing libraries. RNA-Seq libraries were prepared using NEBNext Poly(A) mRNA Magnetic Isolation Module Library Prep Kit (New England Biolabs) and the resulting libraries were paired-end (PE) sequenced (2 × 150 bp) using an Illumina HiSeq2000. The average sequencing depth for each sample was ~ 40 million reads (Fig. S3).

Raw data quality was assessed using FastQC (v 0.11.5; Andrews, 2010). Sequence adapters and low-quality reads (Phred score < 5) were removed using Trimmomatic (v 0.36) with all default parameters69. Transcripts were assembled using AbySS (v 2.0.2)70 and the Trinity (v 2.8.4) software pipeline71 for comparison (Fig. S4). Because of better statistics, we continued to work with the Trinity assemblies (Fig. S5). An initial reference transcriptome was assembled de novo from all RNA samples and all contigs ≥ 200 nucleotides length. The quality of the transcriptome assembly was assessed based on the calculated E90N50 contig length (E90N50 ~ 1.8 Kb; Fig. S6). The initial reference transcriptome was annotated using DIAMOND (v 0.9.13)72. To identify possible contaminants, Ginkgo contigs were searched against bacterial and fungal databases mainly associated with soil and plants, sequence databases compiled from UniProt (www.uniport.org). Sequences with an identity ≥ 50% were removed from the reference transcriptome (N = 2656). This initial transcriptome was re-assembled to improve the assembly stats using AbySS70, the quality of the transcriptome was assessed with contig length and BUSCO annotation (Fig. S7)73, the resulting assembly was used for the following steps. Long open reading frames (ORF) were predicted using TransDecoder (v 3.0.0)71. For gene annotation, the contigs of Ginkgo were searched in several databases of sequence coding land plant proteins (Amborella trichopoda: AMTR1.0_13333, Arabidopsis thaliana: TAIR10_3702, Capsicum annuum: ASM51225v2, Ginkgo biloba: NCBI:txid3311, Gnetum montanum: NCBI:txid3381, Oryza sativa: IRGSP-1.0, Picea abies: NCBI:txid3329, Selaginella moellendorfii: v1.0_88036, Vitis vinifera: 12X_29760; available through Ensembl and Plaza for gymnosperms; Table 1).

To interpret the overall structure of these samples in terms of the gene expression, a Principal Component Analysis (PCA) was performed using the normalized TPM values, as it allows to better interpret the variation of high-dimensional interrelated dataset (with high number of variables) and to detect major differences between samples. PCA was performed using the Python packages: sklearn, seaborn, and bioinfokit (v 2.0.2) Thus, to better understand the similarities within samples a dendrogram was obtained by performing a hierarchical clustering of the samples using a ‘complete linkage’ method (Fig. S8). Dendrogram was obtained using the SciPy package on Python (v 1.5.0).

Transcriptome abundance (RSEM) and expression level (EBSeq) analyses

These analyses were carried out following the pipeline previously proposed74. Sequence reads from the different plant tissues were aligned to the reference transcriptome using Bowtie2 (v 2.4.2)75 and RSEM (RNA-Seq by Expectation Maximization; v 1.3.0) was used to obtain estimates of transcripts abundance for all transcripts76. The resulting expression levels are calculated in terms of Transcripts Per Million (TPM). Transcripts were considered to be differentially expressed between integuments and the other tissues, when TPM was ≥ 0.95 for at least a single tissue and the fold change (log2FC) was ≤ − 2 and ≥ 2 with an FDR p ≤ 0.05 (Fold Discovery Rate). To identify the corresponding Gene Ontology (GO) terms, the differentially expressed genes were further analyzed with Blast2GO (v 5.2.5; Fig. S9). Data analyses and results were plotted using Matplotlib v 3.4.2 and Seaborn v 0.8.1 Python libraries (Fig. S4).

Identification of Ginkgo homologues and maximum likelihood analyses for gene lineages of interest.

One of the genes found in the transcriptome analyses to be putatively involved in integument development in Ginkgo is similar to the Arabidopsis gene FANTASTIC FOUR 3 (FAF3; AT5G19260). To reconstruct the evolution of the FANTASTIC FOUR gene family, we used the four Arabidopsis paralogues (AT4G02810, AT1G03170, AT5G19260, AT3G06020) as a query to perform an amino acid BLAST search in seed plants, using the Phytozome and OneKP databases. A total of 88 sequences were compiled and aligned using the online version of MAFFT (v 7)77. Three Selaginella sequences were used as outgroups to root the tree (LGDQ_scaffold_2012011; JKAA_scaffold_2181098; ZFGK_scaffold_2040141).

Phylogenetic analyses using the nucleotide sequences were performed with RaxML-HPC2 BlackBox78. The newly isolated sequence was deposited in GenBank (accession OK255713).

Supplementary Information

Acknowledgements

C.Z-C thanks Dr. Claudia M. Arenas Gomez (Universidad de Antioquia) for her help with the RSEM and EBSeq analyses. Dr. Natalia Pabon-Mora (Universidad de Antioquia) for helpful discussions which improved this manuscript. This work was performed making use of computing time, software and consulting services provided by the National Center for Genome Analysis Support (NCGAS) from Indiana University. This research is based upon work supported by the National Science Foundation under Grant Nos. DBI-1062432 2011, ABI-1458641 2015, and ABI-1759906 2018 to Indiana University and in part by NSF Grants IOS-0421604, IOS-0922738, and EF-0629817 to the New York Botanical Garden. Any opinions, findings, and conclusions or recommendations expressed in this material are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the views of the National Science Foundation, the National Center for Genome Analysis Support, or Indiana University. This research was funded by the Eppley Foundation for Research, Inc. to BAA.

Author contributions

C.Z.-C. planned and designed the research, performed the experiments and wrote the initial version of this manuscript. D.P.L., D.W.S. and B.A.A. mentored and supported the research. B.A.A. acquired funding for the research. All authors analyzed the data, read and approved the manuscript.

Data availability

The data underlying this article are available in the GenBank Nucleotide Database with accessions provided in the methods and supplemental material. Additional data underlying this article is available upon request to the corresponding author.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher's note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1038/s41598-021-01483-0.

References

- 1.Niklas KJ, Kutschera U. The evolution of the land plant life cycle. New Phytol. 2010;185:27–41. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-8137.2009.03054.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Meeuse ADJ. Fundamentals of Phytomorphology. Ronald; 1966. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Mathews S, Kramer EM. The evolution of reproductive structures in seed plants: A re-examination based on insights from developmental genetics. New Phytol. 2012;194:910–923. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-8137.2012.04091.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.de Haan HRM. Contribution to the knowledge of the morphological value and the phylogeny of the ovule and its integuments. Recl. Trav. Bot. Néerl. 1920;17:219–324. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Walton J. The evolution of the ovule in the pteridosperms. Nature. 1953;1:435–436. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Benson M. The origin of flowering plants. New Phytol. 1904;3:49–51. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-8137.1904.tb05840.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Boesewinkel FD, Bouman F. Integument initiation in Juglans and Pterocarya. Acta Bot. Neerlandica. 1967;16:86–101. doi: 10.1111/j.1438-8677.1967.tb00039.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Takhtajan AL. Flowering Plants: Origin and Dispersal. Springer; 1981. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kenrick P, Crane PR. The origin and early evolution of plants on land. Nature. 1997;389:33–39. doi: 10.1038/37918. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Rothwell GW, Scheckler SE. Biology of ancestral gymnosperms. Origin Evol. Gymnosperms. 1988;85(134):8. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Sánchez-Tinoco MY, Engleman EM. Seed coat anatomy of Ceratozamia mexicana (Cycadales) Bot. Rev. 2004;70:24–38. doi: 10.1663/0006-8101(2004)070[0024:SCAOCM]2.0.CO;2. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Yamada T, Sasaki Y, Sakata K, Gasser CS. Possible roles of BELL 1 and class III homeodomain-leucine zipper genes during integument evolution. Int. J. Plant Sci. 2019;180:623–631. doi: 10.1086/703237. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Zumajo-Cardona C, Ambrose BA. Deciphering the evolution of the ovule genetic network through expression analyses in Gnetum gnemon. Ann. Bot. 2021;128:217. doi: 10.1093/aob/mcab059. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Zhou Z-Y. An overview of fossil Ginkgoales. Palaeoworld. 2009;18:1–22. doi: 10.1016/j.palwor.2009.01.001. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Elliott RC, et al. AINTEGUMENTA, an APETALA2-like gene of Arabidopsis with pleiotropic roles in ovule development and floral organ growth. Plant Cell. 1996;8:155–168. doi: 10.1105/tpc.8.2.155. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Grobeta-Hardt R. WUSCHEL signaling functions in interregional communication during Arabidopsis ovule development. Genes Dev. 2002;16:1129–1138. doi: 10.1101/gad.225202. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Sieber P, et al. Pattern formation during early ovule development in Arabidopsis thaliana. Dev. Biol. 2004;273:321–334. doi: 10.1016/j.ydbio.2004.05.037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Brambilla V, et al. Genetic and molecular interactions between BELL1 and MADS box factors support ovule development in Arabidopsis. Plant Cell. 2007;19:2544–2556. doi: 10.1105/tpc.107.051797. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Deyhle F, Sarkar AK, Tucker EJ, Laux T. WUSCHEL regulates cell differentiation during anther development. Dev. Biol. 2007;302:154–159. doi: 10.1016/j.ydbio.2006.09.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Stuurman J. Shoot meristem maintenance is controlled by a GRAS-gene mediated signal from differentiating cells. Genes Dev. 2002;16:2213–2218. doi: 10.1101/gad.230702. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Reinhardt D, Frenz M, Mandel T, Kuhlemeier C. Microsurgical and laser ablation analysis of interactions between the zones and layers of the tomato shoot apical meristem. Development. 2003;130:4073. doi: 10.1242/dev.00596. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kieffer M, et al. Analysis of the transcription factor WUSCHEL and its functional homologue in Antirrhinum reveals a potential mechanism for their roles in meristem maintenance. Plant Cell. 2006;18:560–573. doi: 10.1105/tpc.105.039107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Nardmann J, Werr W. The shoot stem cell niche in angiosperms: expression patterns of WUS orthologues in rice and maize imply major modifications in the course of mono-and dicot evolution. Mol. Biol. Evol. 2006;23:2492–2504. doi: 10.1093/molbev/msl125. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Tanaka W, et al. Axillary meristem formation in rice requires the WUSCHEL ortholog TILLERS ABSENT1. Plant Cell. 2015;27:1173–1184. doi: 10.1105/tpc.15.00074. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Dash M, Malladi A. The AINTEGUMENTA genes, MdANT1 and MdANT2, are associated with the regulation of cell production during fruit growth in apple (Malus × domestica Borkh.) BMC Plant Biol. 2012;12:98. doi: 10.1186/1471-2229-12-98. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Manchado-Rojo M, Weiss J, Egea-Cortines M. Validation of Aintegumenta as a gene to modify floral size in ornamental plants. Plant Biotechnol. J. 2014;12:1053–1065. doi: 10.1111/pbi.12212. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Klucher KM, Chow H, Reiser L, Fischer RL. The AINTEGUMENTA gene of Arabidopsis required for ovule and female gametophyte development is related to the floral homeotic gene APETALA2. Plant Cell. 1996;8:137–153. doi: 10.1105/tpc.8.2.137. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Baker SC, Robinson-Beers K, Villanueva JM, Gaiser JC, Gasser CS. Interactions among genes regulating ovule development in Arabidopsis thulium. Genetics. 1997;145(4):1109–1124. doi: 10.1093/genetics/145.4.1109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Gasser CS, Broadhvest J, Hauser BA. Genetic analysis of ovule development. Annu. Rev. Plant Biol. 1998;49:1–24. doi: 10.1146/annurev.arplant.49.1.1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Dong Y-H, et al. MDH1: An apple homeobox gene belonging to the BEL1 family. Plant Mol. Biol. 2000;42(4):623–633. doi: 10.1023/A:1006301224125. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Müller J, et al. In vitro interactions between barley TALE homeodomain proteins suggest a role for protein-protein associations in the regulation of Knox gene function: Interactions between barley TALE homeodomain proteins. Plant J. 2001;27:13–23. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-313x.2001.01064.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Bencivenga S, Simonini S, Benková E, Colombo L. The transcription factors BEL1 and SPL are required for cytokinin and auxin signaling during ovule development in Arabidopsis. Plant Cell. 2012;24:2886–2897. doi: 10.1105/tpc.112.100164. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Serrano-Cartagena J, Robles P, Ponce MR, Micol JL. Genetic analysis of leaf form mutants from the Arabidopsis information service collection. Mol. Gen. Genet. 1999;261:725–739. doi: 10.1007/s004380050016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Otsuga D, DeGuzman B, Prigge MJ, Drews GN, Clark SE. REVOLUTA regulates meristem initiation at lateral positions. Plant J. 2001;25:223–236. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-313x.2001.00959.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Emery JF, et al. Radial patterning of Arabidopsis shoots by class III HD-ZIP and KANADI genes. Curr. Biol. 2003;13:1768–1774. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2003.09.035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Waites R, Hudson A. Phantastica: A gene required for dorsoventrality of leaves in Antirrhinum majus. Development. 1995;121:2143–2154. doi: 10.1242/dev.121.7.2143. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 37.McConnell JR, Barton MK. Leaf polarity and meristem formation in Arabidopsis. Development. 1998;125:2935–2942. doi: 10.1242/dev.125.15.2935. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Kelley DR, Gasser CS. Ovule development: Genetic trends and evolutionary considerations. Sex. Plant Reprod. 2009;22:229–234. doi: 10.1007/s00497-009-0107-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Kelley DR, Skinner DJ, Gasser CS. Roles of polarity determinants in ovule development. Plant J. 2009;57:1054–1064. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-313X.2008.03752.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Eshed Y, Baum SF, Perea JV, Bowman JL. Establishment of polarity in lateral organs of plants. Curr. Biol. 2001;11:1251–1260. doi: 10.1016/S0960-9822(01)00392-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Kerstetter RA, Bollman K, Taylor RA, Bomblies K, Poethig RS. KANADI regulates organ polarity in Arabidopsis. Nature. 2001;411:706–709. doi: 10.1038/35079629. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Bowman JL, Eshed Y, Baum SF. Establishment of polarity in angiosperm lateral organs. Trends Genet. 2002;18:134–141. doi: 10.1016/S0168-9525(01)02601-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.McAbee JM, et al. ABERRANT TESTA SHAPE encodes a KANADI family member, linking polarity determination to separation and growth of Arabidopsis ovule integuments. Plant J. 2006;46:522–531. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-313X.2006.02717.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Leon-Kloosterziel KM, Keijzer CJ, Koornneef M. A seed shape mutant of Arabidopsis that is affected in integument development. Plant Cell. 1994;6:385–392. doi: 10.2307/3869758. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Arnault G, et al. Evidence for the extensive conservation of mechanisms of ovule integument development since the most recent common ancestor of living angiosperms. Front. Plant Sci. 2018;9:1352. doi: 10.3389/fpls.2018.01352. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Enugutti B, et al. Regulation of planar growth by the Arabidopsis AGC protein kinase UNICORN. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 2012;109:15060–15065. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1205089109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Yamada T, Hirayama Y, Imaichi R, Kato M. AINTEGUMENTA homolog expression in Gnetum (gymnosperms) and implications for the evolution of ovulate axes in seed plants: ANT homolog expression in gnetum. Evol. Dev. 2008;10:280–287. doi: 10.1111/j.1525-142X.2008.00237.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Nardmann J, Reisewitz P, Werr W. Discrete shoot and root stem cell-promoting WUS/WOX5 functions are an evolutionary innovation of angiosperms. Mol. Biol. Evol. 2009;26:1745–1755. doi: 10.1093/molbev/msp084. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Vasco A, et al. Challenging the paradigms of leaf evolution: Class III HD-Zips in ferns and lycophytes. New Phytol. 2016;212:745–758. doi: 10.1111/nph.14075. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Zumajo-Cardona C, Ambrose BA. Phylogenetic analyses of key developmental genes provide insight into the complex evolution of seeds. Mol. Phylogenet. Evol. 2020;147:106778. doi: 10.1016/j.ympev.2020.106778. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Wahl V, Brand LH, Guo Y-L, Schmid M. The FANTASTIC FOUR proteins influence shoot meristem size in Arabidopsis thaliana. BMC Plant Biol. 2010;10:285. doi: 10.1186/1471-2229-10-285. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Douglas AW, Stevenson DW, Little DP. Ovule development in Ginkgo biloba L., with emphasis on the collar and nucellus. Int. J. Plant Sci. 2007;168:1207–1236. doi: 10.1086/521693. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Youngstrom CE, Geadelmann LF, Irish EE, Cheng C-L. A fern WUSCHEL-RELATED HOMEOBOX gene functions in both gametophyte and sporophyte generations. BMC Plant Biol. 2019;19:416. doi: 10.1186/s12870-019-1991-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Nardmann J, Werr W. The invention of WUS-like stem cell-promoting functions in plants predates leptosporangiate ferns. Plant Mol. Biol. 2012;78:123–134. doi: 10.1007/s11103-011-9851-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Wu C-C, Li F-W, Kramer EM. Large-scale phylogenomic analysis suggests three ancient superclades of the WUSCHEL-RELATED HOMEOBOX transcription factor family in plants. PLoS ONE. 2019;14:e0223521. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0223521. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Bui LT, et al. A fern AINTEGUMENTA gene mirrors BABY BOOM in promoting apogamy in Ceratopteris richardii. Plant J. 2017;90:122–132. doi: 10.1111/tpj.13479. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Horst NA, et al. A single homeobox gene triggers phase transition, embryogenesis and asexual reproduction. Nat. Plants. 2016;2:15209. doi: 10.1038/nplants.2015.209. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Robinson-Beers K, Pruitt RE, Gasser CS. Ovule development in wild-type Arabidopsis and two femalesterile mutants. Plant Cell. 1992;4:1237–1249. doi: 10.2307/3869410. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Enugutti B, Kirchhelle C, Oelschner M, Ruiz RAT, Schliebner I, Leister D, Schneitz K. Schliebner, I., Leister, D., & Schneitz, K. Regulation of planar growth by the Arabidopsis AGC protein kinase UNICORN. PNAS. 2012;109:15060–15065. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1205089109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Zumajo-Cardona C, Vasco A, Ambrose BA. The evolution of the KANADI gene family and leaf development in lycophytes and ferns. Plants Basel Switz. 2019;8:E313. doi: 10.3390/plants8090313. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Zhang G-H, Xu Q, Zhu X-D, Qian Q, Xue H-W. SHALLOT-LIKE1 is a KANADI transcription factor that modulates rice leaf rolling by regulating leaf abaxial cell development. Plant Cell. 2009;21:719–735. doi: 10.1105/tpc.108.061457. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Candela H, Johnston R, Gerhold A, Foster T, Hake S. The milkweed pod1 gene encodes a KANADI protein that is required for abaxial/adaxial patterning in maize leaves. Plant Cell. 2008;20:2073–2087. doi: 10.1105/tpc.108.059709. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Floyd SK, Bowman JL. Distinct developmental mechanisms reflect the independent origins of leaves in vascular plants. Curr. Biol. 2006;16:1911–1917. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2006.07.067. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Riechmann JL, Ratcliffe OJ. A genomic perspective on plant transcription factors. Curr. Opin. Plant Biol. 2000;3:423–434. doi: 10.1016/S1369-5266(00)00107-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Figueiredo DD, Köhler C. Signalling events regulating seed coat development. Biochem. Soc. Trans. 2014;42:358–363. doi: 10.1042/BST20130221. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Jiao Y, et al. Ancestral polyploidy in seed plants and angiosperms. Nature. 2011;473:97–100. doi: 10.1038/nature09916. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Schneitz K, Hülskamp M, Pruitt RE. Wild-type ovule development in Arabidopsis thaliana: A light microscope study of cleared whole-mount tissue. Plant J. 1995;7:731–749. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-313X.1995.07050731.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Ambrose BA, et al. Molecular and genetic analyses of the silky1 gene reveal conservation in floral organ specification between eudicots and monocots. Mol. Cell. 2000;5:569–579. doi: 10.1016/S1097-2765(00)80450-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Bolger AM, Lohse M, Usadel B. Trimmomatic: A flexible trimmer for Illumina sequence data. Bioinformatics. 2014;30:2114–2120. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btu170. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Jackman SD, et al. ABySS 2.0: Resource-efficient assembly of large genomes using a Bloom filter. Genome Res. 2017;27:768–777. doi: 10.1101/gr.214346.116. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Haas BJ, et al. De novo transcript sequence reconstruction from RNA-seq using the trinity platform for reference generation and analysis. Nat. Protoc. 2013;8:1494–1512. doi: 10.1038/nprot.2013.084. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Buchfink B, Xie C, Huson DH. Fast and sensitive protein alignment using DIAMOND. Nat. Methods. 2015;12:59–60. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.3176. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Seppey M, Manni M, Zdobnov EM. BUSCO: Assessing genome assembly and annotation completeness. Methods Mol. Biol. Clifton N.J. 2019;1962:227–245. doi: 10.1007/978-1-4939-9173-0_14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Cheng H, Wang Y, Sun M-A. Comparison of gene expression profiles in nonmodel eukaryotic organisms with RNA-Seq. Methods Mol. Biol. Clifton N.J. 2018;1751:3–16. doi: 10.1007/978-1-4939-7710-9_1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Langmead B, Salzberg SL. Fast gapped-read alignment with Bowtie 2. Nat. Methods. 2012;9:357–359. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.1923. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Li B, Dewey CN. RSEM: Accurate transcript quantification from RNA-Seq data with or without a reference genome. BMC Bioinform. 2011;12:323. doi: 10.1186/1471-2105-12-323. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Katoh K, Standley DM. MAFFT: Iterative refinement and additional methods. In: Russell DJ, editor. Multiple Sequence Alignment Methods. Humana Press; 2014. pp. 131–146. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Stamatakis A. RAxML version 8: A tool for phylogenetic analysis and post-analysis of large phylogenies. Bioinformatics. 2014;30:1312–1313. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btu033. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

The data underlying this article are available in the GenBank Nucleotide Database with accessions provided in the methods and supplemental material. Additional data underlying this article is available upon request to the corresponding author.