Abstract

Early right heart failure (RHF) occurs in up to 40% of patients following left ventricular assist device (LVAD) implantation and is associated with increased morbidity and mortality. The most recent report from the Mechanical Circulatory Support-Academic Research Consortium (MCS-ARC) working group subdivides early RHF into early acute RHF and early post-implant RHF. We sought to determine the effectiveness of right ventricular (RV) longitudinal strain (LS) in predicting RHF according to the new MCS-ARC definition. We retrospectively analyzed clinical and echocardiographic data of patients who underwent LVAD implantation between 2015–2018. RVLS in the 4-chamber (4ch), RV outflow tract (RVOT), and subcostal (SC) views were measured on pre-LVAD echocardiograms. 55 patients were included in this study. Six patients (11%) suffered early acute RHF, requiring concomitant RVAD implantation intraoperatively. 22 patients (40%) had post-implant RHF. RVLS was significantly reduced in patients who developed early acute and post-implant RHF. At a cutoff of −9.7%, 4ch RVLS had a sensitivity of 88.9% and a specificity of 77.8% for predicting RHF and area under the receiver operating characteristic curve of 0.86 (95% CI 0.76–0.97). Echocardiographic RV strain outperformed more invasive hemodynamic measures and clinical parameters in predicting RHF.

Keywords: RV strain, early right heart failure, LVAD

INTRODUCTION

Early right heart failure (RHF) occurs in 20–40% of patients following left ventricular assist device (LVAD) implantation and is associated with significantly increased peri-operative mortality and morbidity as well as prolonged hospitalization.1–5 The most recent report from the Mechanical Circulatory Support-Academic Research Consortium (MCS-ARC) subdivides early RHF into early acute RHF and early post-implant RHF.6 Early acute RHF (“acute RHF” in this manuscript) occurs intraoperatively, necessitating concomitant right ventricular assist device (RVAD) implantation, while early post implant RHF occurs up to 30 days post-LVAD implantation.

Early RHF is likely multifactorial and may occur via several proposed mechanisms including increased preload to an unsupported right ventricle (RV),7 septal wall bowing induced by the LVAD,8 and worsening of pre-existing tricuspid regurgitation.9 Current practice guidelines strongly recommend (class I recommendation) assessment of RV function as part of the patient selection process for durable LVAD.10 However despite the development of numerous risk scores, none of them have been successful in reliably predicting RHF, and pre-implant risk assessment of RHF remains an unsolved challenge.11–16

Pre-operative echocardiographic imaging is useful in assessing RV function but can be limited by complex RV geometry and load dependence.17 Traditional echocardiographic parameters including RV fractional area change (FAC) and tricuspid annular plane systolic excursion (TAPSE) have had poor sensitivity in predicting RHF.15 Two-dimensional strain imaging has recently emerged as a more accurate quantitative assessment of RV function.18 It measures the magnitude of myocardial deformation via frame-by-frame tracking of speckles, which are natural acoustic markers generated from interactions between the ultrasound and myocardial tissue.19 It is independent from the angle of insonation and less dependent on cardiac translational movements.19

In this study, we sought to determine the effectiveness of RV longitudinal strain (LS) in predicting acute and early post-implant RHF following LVAD implantation according to the new MCS-ARC definition and comprehensively compare RVLS to other previously proposed predictors of RHF. In addition, we examined both segmental and global strain and assessed the impact of measuring strain in different echocardiographic views to allow for better characterization and standardization of RV strain for clinical use.

METHODS

Study Population

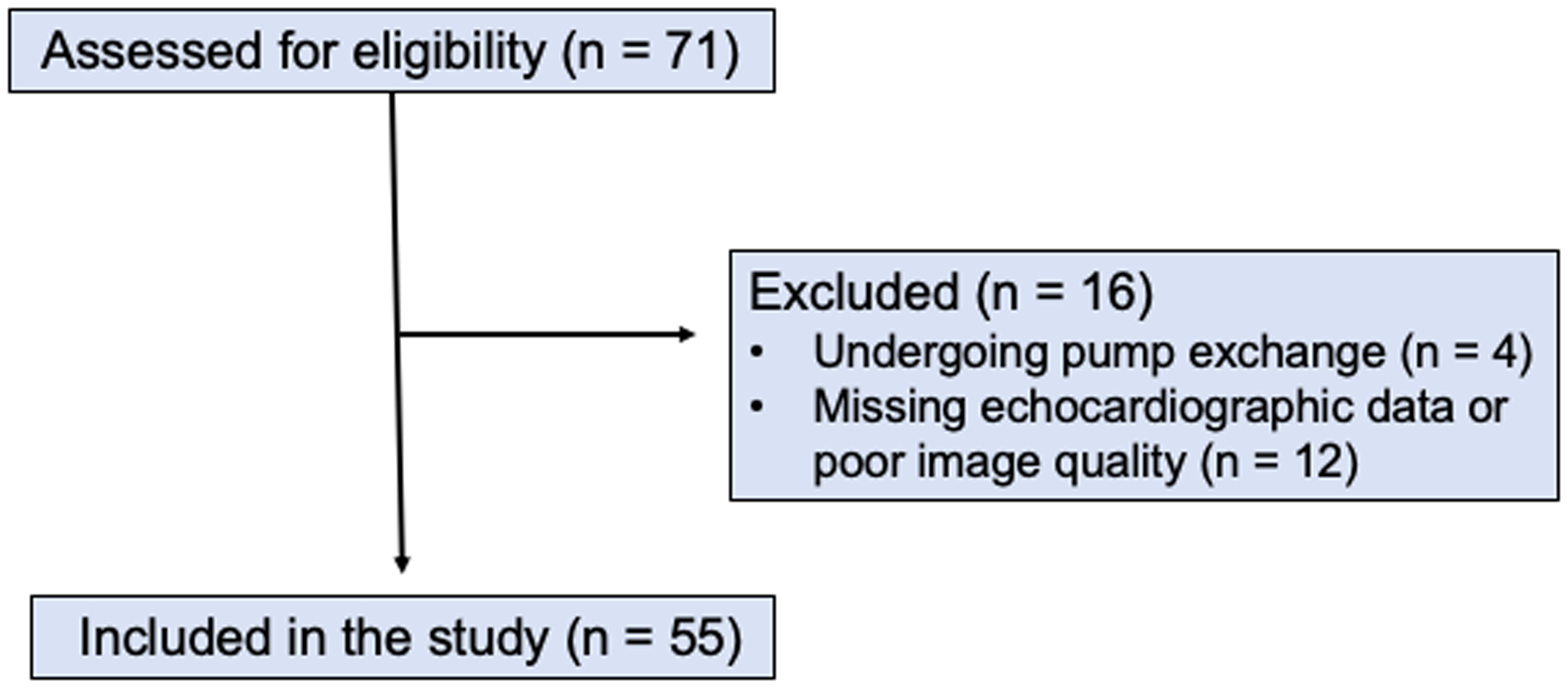

We retrospectively analyzed clinical, hemodynamic, and echocardiographic data of consecutive patients who underwent LVAD implantation between 2015–2018 at the Hospital of the University of Pennsylvania. These devices included the Abbott HeartMate 3 and the Medtronic HeartWare HVAD. Patients undergoing replacement of an existing LVAD and those without available or with poor quality pre-operative transthoracic echocardiograms were excluded (Figure 1). Patients who received the Abbott HeartMate II were also excluded from the study. The study was approved by the Institutional Review Board with waiver of consent for retrospective data review.

Figure 1 :

Consort flow diagram of patient inclusion in study

Endpoints

Acute RHF was defined in accordance to the newly updated MCS-ARC report as the need for implantation of a temporary or durable RVAD (including ECMO) concomitant with LVAD implantation (RVAD implanted prior to the patient leaving the operating room).6

Early post-implant RHF was defined as: need for implantation of a temporary or durable RVAD (including ECMO) within 30 days following LVAD implantation for any duration of time; or, failure to wean from inotropic or vasopressor support or inhaled nitric oxide within fourteen days following LVAD implantation or having to initiate this support within thirty days of implant for a duration of at least 14 days.6

Clinical and hemodynamic data

Clinical, laboratory, and hemodynamic parameters were collected on each patient including the pre-implant pulmonary artery pulsatility index (PAPi),20 the pre-implant RV stroke work index (RVSWI), and the RA pressure 48-hours post implant. The Michigan RV Risk score was calculated for each patient.13 The score assigns points based on 4 variables: a vasopressor requirement (4 points), aspartate aminotransferase ≥80 IU/l (2 points), bilirubin ≥2.0 mg/dl (2.5 points), and creatinine ≥2.3 mg/dl (3 points). The CRITT score was also calculated for each patient, which assigns points based on 5 variables: central venous pressure >15 mmHg (C), severe RV dysfunction on echocardiogram (R), preoperative intubation (I), severe tricuspid regurgitation (T), and tachycardia/heart rate >100 (T).21

Echocardiographic assessment

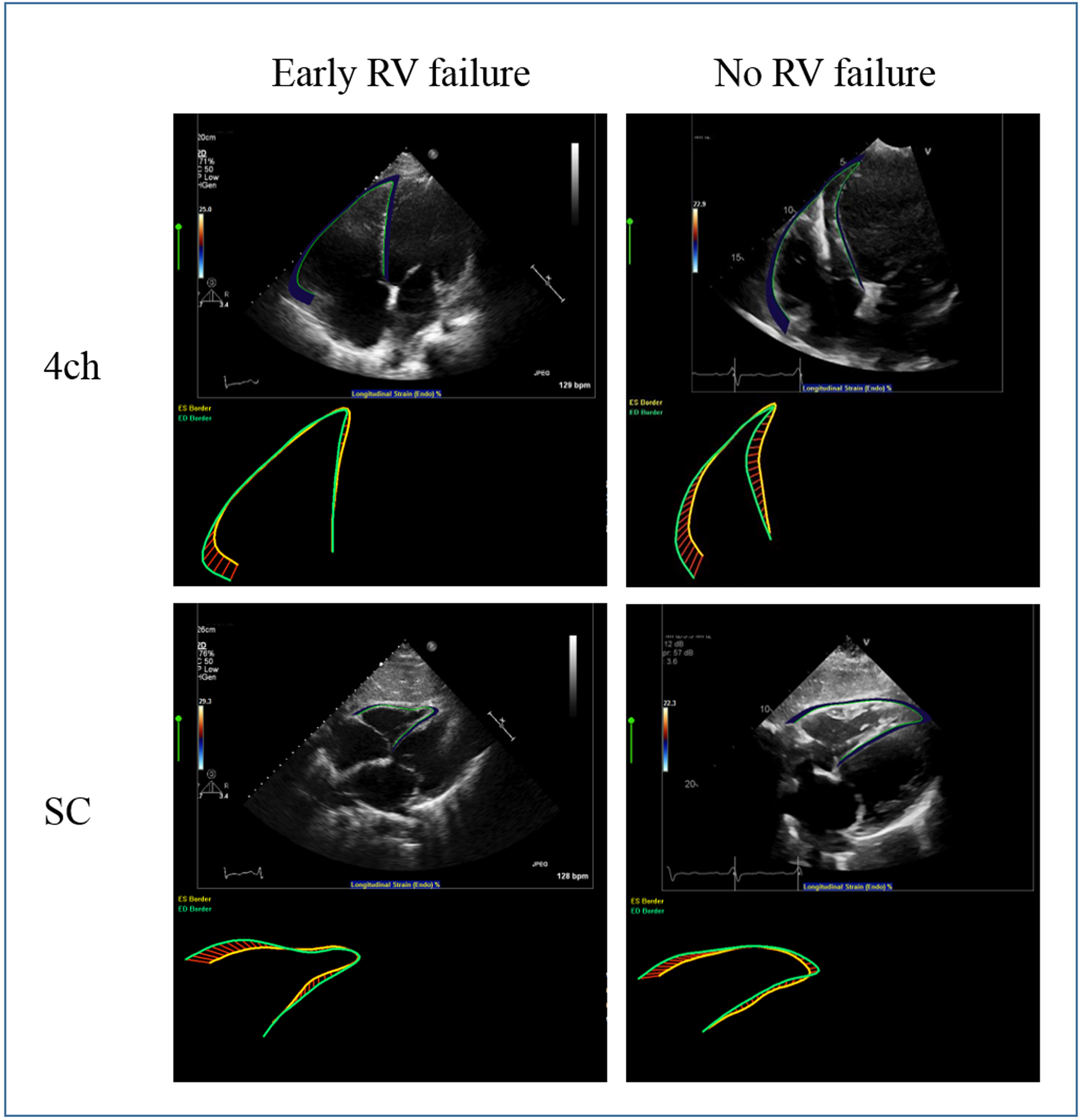

The echocardiograms were performed per clinical standards prior to LVAD implantation and were obtained using commercially available ultrasound systems (iE33, Philips Healthcare, Amsterdam, The Netherlands). Global longitudinal and segmental (septum and free wall) RV strain as well as fractional area change (FAC) in the 4-chamber (4ch), right ventricular out flow (RVOT), and subcostal (SC) views were measured by off-line analysis using the RV package of the 2-dimensional (2D) strain software (TomTec, Chicago, USA). The endocardial border of the RV was manually traced by an investigator blinded to the clinical status of the patient and strain curves were generated automatically (Figure 2). TAPSE was measured using 2D images, as previously described.22 Intra-observer (one month later by the same observer) and inter-observer variabilities (another observer) were obtained on a subgroup of 16 randomly selected patients in all three views and averaged across the views. For patients on mechanical circulatory support, all echocardiograms were performed with the patient on full support.

Figure 2:

RVGLS measured in the 4ch and SC views on a patient who developed post-LVAD early RHF (left) and a patient who did not develop post-LVAD early RHF (right).

Statistical analysis

All statistical analyses were performed using R (version 4.0.2). Values for continuous characteristics were presented as mean ± standard deviation for normally distributed variables or median [interquartile range] for non-normal distributions. Univariable comparison of parameters between patients with and without RHF were made using the chi-squared test, Fisher exact test, or the Kruskal-Willis test where appropriate. In Table II, patients with RHF were subdivided into those who developed acute RHF and those who developed early post-implant RHF. The Kruskal-Willis ANOVA, ANOVA, and Fisher exact test were used as appropriate for comparison of echocardiographic parameters in these tables. A p value of <0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Logistic regression analysis was performed to calculate odds ratios for developing RHF. The ROCR package was used for receiver operator curve (ROC) analysis to calculate area under the curve (AUC).23 The DeLong test was used to compare AUCs. The OptimalCutpoints package was used to determine the optimal cutoff point to maximize sensitivity and specificity in predicting RHF when applicable.24 The irr (Interrater Reliability and Agreement) package was used for calculation of correlation coefficients to assess intra-operator and inter-operator variability.25

RESULTS

Initially, 71 patients were screened for the study. Four patients were excluded due to undergoing pump exchange. 12 patients were excluded on the basis of missing echocardiographic data or poor image quality (Figure 1). A total of 55 patients were included in the final study, with a mean age of 56 ± 14 years. 21 patients (38%) had Abbott HeartMate3 devices and the remaining 34 patients (62%) had Medtronic HeartWare HVAD devices. The patients were predominantly male (84%) and suffered from non-ischemic cardiomyopathy (71%). The patient’s baseline characteristics are summarized in Table I. Six patients (11%) suffered acute RHF, requiring concomitant RVAD implantation intraoperatively. 22 patients (40%) had early post-implant RHF. Patients who developed RHF were more likely to have a pre-operative INTERMACS profile of 1, corresponding to critical cardiogenic shock. Two patients (7%) in the no RHF group required mechanical circulatory support pre-operatively compared to seven patients (25%) in the RHF group (p = 0.14). The two patients who did not develop RHF underwent intra-aortic balloon pump insertion as did five of the patients who did develop RHF. The remaining two patients who developed RHF required Impella 5.0 (Abiomed, Danvers, MA).

Table I:

Baseline patient characteristics by right heart failure status

| Characteristics | No RHF N = 27 |

RHF* N = 28 |

P value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age (yrs) | 59 [49–71] | 55 [46–64] | 0.52 |

| Male (%) | 22 (81) | 24 (86) | 0.95 |

| Body mass index | 32.0 [26.6–37.0] | 30.6 [26.6–34.7] | 0.47 |

| Hypertension (%) | 12 (44) | 18 (64) | 0.23 |

| Diabetes (%) | 11 (41) | 10 (36) | 0.92 |

| Ischemic etiology (%) | 7 (26) | 9 (32) | 0.77 |

| Bridge to transplant (%) | 9 (33) | 10 (36) | >0.99 |

| HeartMate 3 (%) | 12 (44) | 9 (32) | 0.41 |

| Pre-operative vasopressor (%) | 1 (4) | 3 (11) | 0.61 |

| Pre-operative MCS (%) | 2 (7) | 7 (25) | 0.14 |

| Aspartate aminotransferase (U/l) | 23 [17–32] | 25 [17–49] | 0.58 |

| Bilirubin (mg/dl) | 0.8 [0.6–1.3] | 1.1 [0.5–1.5] | 0.35 |

| Creatinine (mg/dl) | 1.15 [1.01–1.51] | 1.38 [1.20–1.91] | 0.41 |

| INTERMACS | <0.001 | ||

| INTERMACS 1 (%) | 0 (0) | 6 (21) | - |

| INTERMACS 2 (%) | 15 (56) | 20 (71) | - |

| INTERMACS 3 (%) | 12 (44) | 2 (7) | - |

| Bypass time (minutes) | 59 [39–75] | 63 [50–94] | 0.43 |

| Blood products administered (units) | 1 [1–4] | 2 [1–20] | 0.29 |

Values are median [interquartile range] or n/N (%).

Abbreviations: RHF, right heart failure; MCS, Mechanical Circulatory Support; INTERMACS, Interagency Registry for Mechanically Assisted Circulatory Support

RHF refers to the group of patients with both acute RHF and early post-implant RHF.

RV global longitudinal strain (GLS) was significantly reduced in patients who developed acute RHF and early post implant RHF compared to those who did not (Table II). 4ch and SC RVGLS were lower in those who developed either early post-implant or acute RHF compared to those who did not develop RHF (4ch p <0.0001, SC p = 0.004). FAC measured in the apical 4ch views was also significant with p = 0.03 when comparing acute and early post implant RHF to no RHF groups. However, when conducting pairwise comparisons between acute and early post implant RHF none of the echocardiographic parameters reached statistical significance (Supplemental Table I). Segmental analysis of free wall and septal strain suggests that free wall strain is more robust in detecting early RHF in both the 4ch and SC views. Intra-observer variability and inter-observer variability was 0.89 and 0.88, respectively.

Table II:

Echocardiographic parameters by right heart failure status

| Echocardiographic parameters | No RHF N = 27 |

Acute RHF N = 6 |

Post-implant RHF N = 22 |

P value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| LV ejection fraction (%)* | 15 [10–20] | 10 [10–14] | 10 [10–19] | 0.54 |

| MR (moderate to severe, %)* | 17 (63) | 2 (33) | 12 (55) | 0.47 |

| Qualitative RV dysfunction (%)* | 11 (41) | 5 (83) | 9 (41) | 0.40 |

| TR (moderate to severe, %)* | 6 (22) | 3 (50) | 7 (32) | 0.40 |

| Average GLS | −11.00 ± 3.5 | −6.41 ± 2.2 | −7.24 ± 2.8 | <0.0001 |

| RVOT GLS | −7.58 ± 2.2 | −6.35 ± 3.4 | −6.02 ± 3.2 | 0.15 |

| RVOT septal LS | −7.41 ± 4.0 | −5.07 ± 2.5 | −6.16 ± 4.8 | 0.39 |

| RVOT free wall LS | −5.64 ± 4.8 | −5.70 ± 5.1 | −4.74 ± 4.4 | 0.78 |

| 4ch GLS | −12.26 ± 4.0 | −5.81 ± 2.2 | −7.07 ± 3.9 | <0.0001 |

| 4ch septal LS | −7.48 ± 4.2 | −4.06 ± 4.2 | −2.99 ± 5.6 | 0.007 |

| 4ch free wall LS | −13.28 ± 4.7 | −6.26 ± 2.0 | −8.99 ± 3.9 | <0.001 |

| SC GLS | −14.23 ± 7.2 | −5.79 ± 3.2 | −7.71 ± 4.4 | 0.004 |

| SC septal LS | −9.00 ± 7.1 | −2.15 ± 6.4 | −4.48 ± 5.6 | 0.05 |

| SC free wall LS | −16.25 ± 8.2 | −5.75 ± 2.8 | −7.70 ± 6.8 | 0.002 |

| RVOT FAC | 14.52 ± 9.2 | 12.75 ± 9.1 | 11.96 ± 8.1 | 0.60 |

| 4ch FAC | 20.77 ± 8.4 | 12.66 ± 5.4 | 15.44 ± 7.7 | 0.03 |

| SC FAC | 25.55 ± 11.0 | 16.39 ± 11.6 | 17.32 ± 11.4 | 0.08 |

| TAPSE | 1.98 ± 0.6 | 1.23 ± 0.4 | 1.75 ± 0.5 | 0.05 |

Values are median [interquartile range], n/N (%), or mean ± SD.

Extracted from clinical echocardiography reports.

Abbreviations: FAC, fractional area change; 4ch, four-chamber; GLS, global longitudinal strain; LS, longitudinal strain; LV, left ventricular; MR, mitral regurgitation; RHF, right heart failure; RV, right ventricle; RVOT, right ventricular outflow tract; SC, subcostal; TAPSE, tricuspid annular plane systolic excursion; TR, tricuspid regurgitation

Patients who developed acute and early post-implant RHF were then combined and evaluated against those who did not develop RHF. Table III displays continuous odds ratios for developing RHF based on echocardiographic parameters. At a cutoff of −9.7%, RVGLS averaged over the three views was predictive of RHF with a sensitivity of 89.3% and a specificity of 66.7% with an AUC of 0.85 and an odds ratio (OR) of 1.60 (95% CI: 1.24–2.06). At the same cutoff, strain measured in the 4ch view had a sensitivity of 88.9% and a specificity of 77.8% with an AUC of 0.86 and an OR of 1.44 (95% CI 1.21–1.79).

Table III:

Predictors of acute and post-implant right heart failure

| Parameters | OR for RHF*† (95% CI) | P value |

|---|---|---|

| Average GLS | 1.60 (1.24–2.06) | <0.0001 |

| RVOT GLS | 1.22 (1.00–1.52) | 0.06 |

| RVOT septal LS | 1.09 (0.96–1.25) | 0.21 |

| RVOT free wall LS | 1.03 (0.92–1.17) | 0.58 |

| 4ch GLS | 1.44 (1.21–1.79) | <0.0001 |

| 4ch septal LS | 1.25 (1.08–1.49) | 0.03 |

| 4ch free wall LS | 1.33 (1.14–1.61) | 0.004 |

| SC GLS | 1.29 (1.11–1.58) | 0.004 |

| SC septal LS | 1.16 (1.03–1.36) | 0.03 |

| SC free wall LS | 1.23 (1.09–1.44) | 0.004 |

| RVOT FAC | 0.97 (0.90–1.03) | 0.31 |

| 4ch FAC | 0.91 (0.83–0.97) | 0.02 |

| SC FAC | 0.93 (0.85–0.99) | 0.04 |

| TAPSE | 0.37 (0.11–1.11) | 0.09 |

| Michigan RV Risk Score | 1.32 (0.98–1.78) | 0.07 |

| CRITT Score | 1.88 (0.98–3.62) | 0.06 |

Abbreviations: FAC, fractional area change; 4ch, four-chamber; GLS, global longitudinal strain; LS, longitudinal strain; OR, odds ratio; RHF, right heart failure; RV, right ventricular; RVOT, right ventricular outflow tract; SC, subcostal; TAPSE, tricuspid annular plane systolic excursion

RHF refers to the group of patients with both acute RHF and early post-implant RHF.

Odds ratios were continuous.

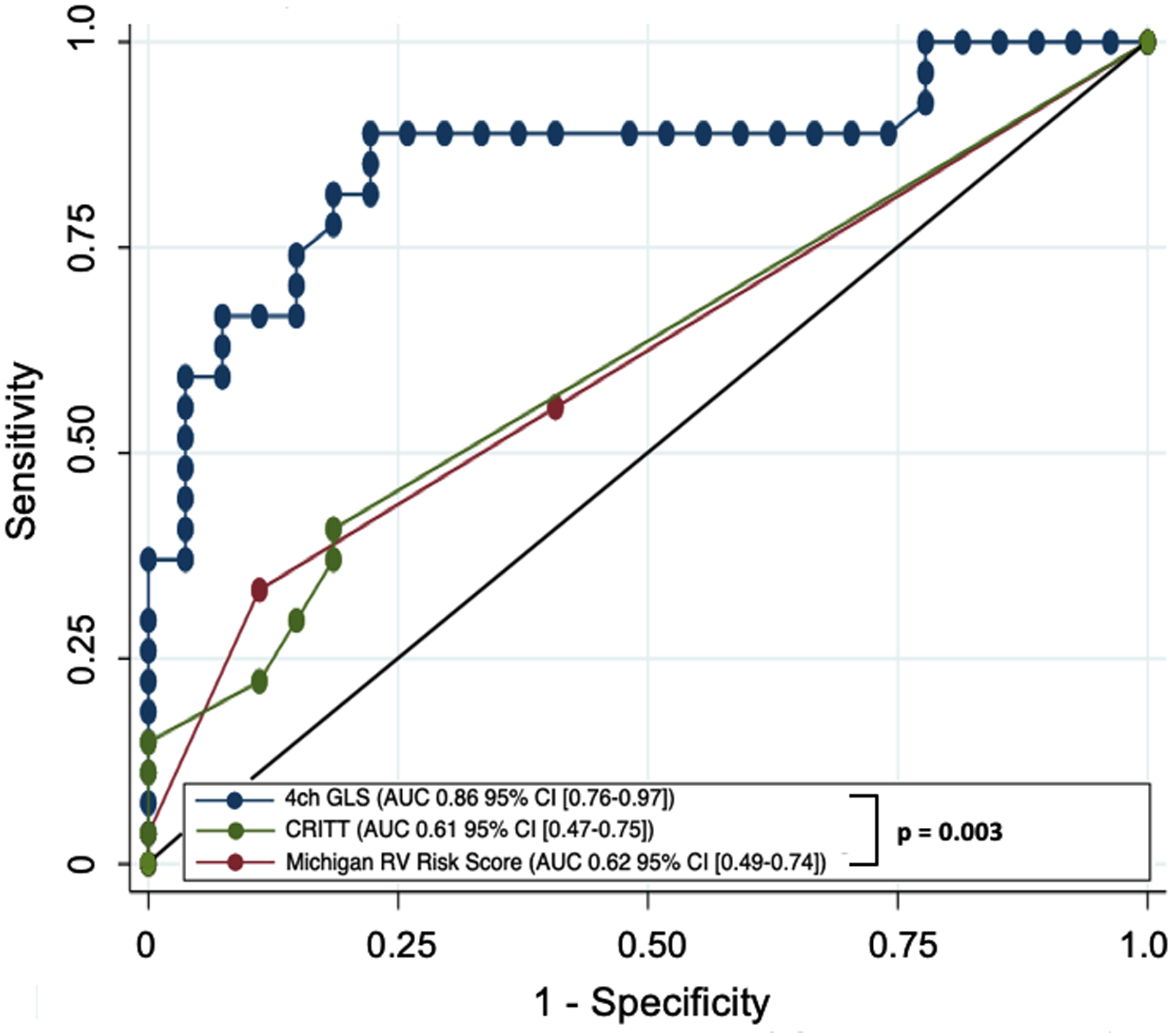

Previously studied metrics including the Michigan RV Risk Score, CRITT score, PAPi, and RVSWI were also evaluated (Tables IV and V). All patients in our cohort with a Michigan RV Risk Score greater than 4 developed RHF (n = 4). However, scores were overall low across all patients in the cohort. The CRITT score was also low on average in this cohort of patients, with only 1 patient with a score above 3. Figure 3 demonstrates the ROC curves for 4ch-RVGLS (AUC 0.86 [95% CI 0.76–0.97]) compared to the ROC curves generated by the Michigan RV Risk Score (AUC 0.62 [95% CI 0.49–0.74]) and the CRITT score (AUC 0.61 [95% CI 0.47–0.75]; p = 0.003). The PAPi and RVSWI were not significantly different between the two groups (p = 0.51, p = 0.47, respectively). Post implant hemodynamics were also not significantly different between the two groups (Supplemental Table II).

Table IV:

Risk score comparisons by right heart failure status

| Risk Score | No RHF N = 27 |

RHF* N = 28 |

P value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Michigan RV Risk Score | 0.14 | ||

| Michigan RV Risk Score ≤ 3 | 24 | 22 | - |

| Michigan RV Risk Score 4–5 | 3 | 2 | - |

| Michigan RV Risk Score ≥ 5.5 | 0 | 4 | - |

| CRITT Score | 0.14 | ||

| CRITT 0–1 | 24 | 18 | - |

| CRITT 2–3 | 3 | 9 | - |

| CRITT 4 | 0 | 1 | - |

RHF, right heart failure; RV, right ventricle

RHF refers to the group of patients with both acute RHF and early post-implant RHF.

Table V:

Hemodynamic parameters by right heart failure status

| Hemodynamic parameters | No RHF N = 27 |

RHF* N = 28 |

P value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Heart rate (beats/min) | 79 [71–97] | 86 [79–106] | 0.15 |

| Mean arterial pressure (mm Hg) | 75 [69–82] | 74 [72–80] | 0.56 |

| RA pressure (mm Hg) | 10 [7–12] | 12 [10–15] | 0.10 |

| Mean PA pressure (mm Hg) | 36 [31–44] | 36 [31–41] | 0.77 |

| Cardiac index (l/min/m2) | 2.00 [1.70–2.25] | 1.85 [1.68–2.22] | 0.51 |

| RV stroke work index (mm Hg ml/m2 beat) | 8.50 [5.97–11.75] | 7.31 [5.65–9.63] | 0.47 |

| Pulmonary artery pulsatility index | 2.89 [1.79–4.60] | 2.23 [1.52–3.53] | 0.51 |

| LVAD speed (rpm) | 5300 [2760–5500] | 2850 [2700–5325] | 0.16 |

Values are median [interquartile range].

Abbreviations: PA, pulmonary artery; RA, right atrium; RHF, right heart failure; RV, right ventricle; LVAD, left ventricular assist device

RHF refers to the group of patients with both acute RHF and early post-implant RHF.

Figure 3:

4ch RV strain,CRITT score, and Michigan RV Risk score Roc curves for predicting RHF

Finally, we performed multivariable logistic regression analysis using 4ch-RVGLS, adjusting for the INTERMACS profile and Michigan RV Risk Score and found that 4ch-RVGLS remained a significant predictor of RHF (OR 1.35 [95% CI: 1.10–1.66], p = 0.004). The overall AUC of the logistic regression model was 0.88. We also performed a separate multivariable logistic regression analysis combining 4ch-RVGLS, while adjusting for the INTERMACS profile and CRITT score. Similarly, in this analysis 4ch-RVGLS remained a significant predictor of RHF (OR 1.39 [95% CI: 1.11–1.72], p = 0.003). The overall AUC of the logistic regression model was 0.89.

DISCUSSION

Early RHF is a leading cause of mortality after LVAD implantation. Numerous risk scores have been developed over the last decade to quantify the risk of RHF in patients undergoing LVAD. However, none of these risk scores have been shown to reliably predict RHF in clinical practice and lack external validation. This is the first study to evaluate the role of RV strain in predicting post-LVAD implant RHF according to the new MCS-ARC definition. Our results showed that RVGLS was an important predictor of RHF in multiple views and outperformed all other risk scores and other echocardiographic and hemodynamic parameters examined in this study. It could not, however, distinguish between those patients who would go on to develop acute versus early post implant RHF, but this may have been limited by the small number of patients in our study who required concomitant RVAD and warrants further study with a larger sample size.

Echocardiography is noninvasive and can be easily obtained at the bedside in these oftentimes critically ill patients and is an important tool in the assessment of RV function pre-operatively. RVGLS appropriately identified patients with low RV reserve who then went on to develop RV failure in the post-operative period. Several prior studies have now demonstrated the ability of RV strain to predict RV failure in conjunction with other risk scores and measurements of RV function including RV ejection fraction, size, velocity of contraction, geometry, and intra-RV dyssynchrony.14,26 In our study we showed that RV longitudinal strain alone could discriminate those patients at high risk of RV failure as a standalone metric. Moreover, the largest prior study by Grant et al which included 117 patients found a peak strain cutoff of −9.6%; our study cutoff point was remarkably close at −9.7%.14 In a smaller prospective study of 68 patients, Kato et al. created an RHF prediction model using an absolute RV longitudinal strain <|14|% combined with pre-operative peak systolic velocity < 4.4cm/s, and a ratio of RV peak early trans-tricuspid filling velocities to early diastolic velocity of greater than 10.26 However, ours is the first study evaluating RV strain in patients with RHF using the newest definitions of acute RHF. We also showed that lower RVGLS was sensitive and specific for prediction of early RHF when measured in both the 4ch and SC views. This finding is of particular importance in a population of post-operative patients with often limited echocardiographic views. In addition, we compared global and segmental strain analysis and found that GLS analysis is superior to segmental analysis in predicting RHF with higher overall odds ratios and AUCs.

RV strain has become increasingly recognized as an effective measurement of RV function, capable of detecting subtle abnormalities in RV function despite preserved TAPSE and FAC.27 In patients with pulmonary hypertension, RV global systolic strain > −15% was associated with significantly higher mortality.28 In a recent prospective study of 618 patients hospitalized for acute decompensated heart failure, RV free wall longitudinal strain at a cutoff of ≥ −13.1% was an independent predictor of cardiac events.29 Decreased RV strain has also been associated with all-cause or cardiovascular mortality in a longitudinal study of patients with chronic heart failure with reduced ejection fraction who were followed for 36 ± 26 months. Both RVGLS and RV free wall LS were independently associated with increased mortality at a cutoff of −14.0% and −20.6%, respectively.30 In a study of patients with heart failure with preserved ejection fraction, individuals with worse symptoms and signs of heart failure had lower RVGLS (−14.4 vs −16.9, p < 0.001) compared to asymptomatic controls. Interestingly, pulmonary artery systolic pressure was not associated with symptoms of heart failure.31 At a cutoff of −9.7%, we used RVGLS to identify a population of patients with poor RV reserve who are at high risk of developing early RHF following LVAD implantation.

Traditional clinical and hemodynamic parameters are highly variable in the perioperative patient undergoing LVAD implantation. Hemodynamic parameters including RA pressure, cardiac index, mean pulmonary artery pressure, RVSWI, and PAPi did not reliably predict RHF in our cohort. The Michigan RV risk score and CRITT score were both very specific for RHF at higher values but were not sensitive in predicting RHF. Patients with a Michigan RV risk score higher than 4 and a CRITT score higher than 3 should certainly be considered for biventricular support, but these scores miss many patients who may also potentially benefit from planned RVAD.

This study has several limitations. It was a single-center study and was retrospectively performed. Compared to other similar studies our RV strain values were lower on average which corresponded to a higher rate of RHF. This likely reflects a sicker population who are being considered for LVAD therapy at our institution as demonstrated by the high proportion of patients with an INTERMACS profile of 1 or 2. In addition, due to the small size of the study, adjustments for multiple comparisons were not made, although 4ch GLS, 4ch free wall LS, and average GLS would maintain significance with even the most stringent adjustments. This study also did not include post-implant RV strain measurements, which should theoretically improve in patients who did not develop RHF. Finally, the study population was limited and the rates of death, development of late RHF, or the need for RVAD were too small to assess the role of 2D strain in predicting these outcomes. Further prospective studies with larger patient populations will be needed to validate and better characterize the ability of RV strain to predict acute, early, and late RHF.

CONCLUSIONS

Our study is the first to evaluate RV strain as a predictor of post-LVAD implant right ventricular failure according to the new MCS-ARC definition. RV strain outperformed more invasive hemodynamic measures and clinical predictors of RHF and may serve as a useful tool in risk stratifying patients for device selection. These findings will ultimately need to be further validated in prospective, multi-centered studies.

Supplementary Material

Footnotes

Conflict of Interest: None

DISCLOSURE STATEMENT

None of the authors has a financial relationship with a commercial entity that has an interest in the subject of the presented manuscript or other conflicts of interest to disclose.

REFERENCES

- 1.Dang NC, Topkara VK, Mercando M, Kay J, Kruger KH, Aboodi MS, Oz MC, Naka Y: Right heart failure after Left Ventricular Assist Device implantation in patients with chronic congestive heart failure. J Heart Lung Transplant 25: 1–6, 2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Patel ND, Weiss ES, Schaffer J, Ullrich SL, RIvard DC, Shah As, Russell SD, Conte JV: Right heart dysfunction after Left Ventricular Assist Device implantation: a comparison of the pulsatile HeartMate I and Axial-Flow HeartMate II devices. Ann Thorac Surg 86: 832–840, 2008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kormos RL, Teuteberg JJ, Pagani FD, Russell SD, John R, Miller LW, Massey T, Milano CA, Moazami N, Sundareswaran KS, Farrar DJ: Right ventricular failure in patients with the HeartMate II continuous-flow left ventricular assist device: incidence, risk factors, and effect on outcomes. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg 139: 1316–1324, 2010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Birati EY, Rame JE. Left ventricular assist device management and complications: Crit Care Clin 30: 607–27, 2014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Birati EY, Jessup M. Left Ventricular Assist Devices in the management of heart failure: Card Fail Rev 1: 25–30, 2015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kormos RL, Antonides CFJ, Goldstein DJ, Cowger JA, Starling RC, Kirklin JK, Rame JE, Rosenthal D, Mooney ML, Caliskan K, Messe SR, Teuteberg JJ, Mohacsi P, Slaughter MS, Potapov EV, Rao V, Schima H, Stehlik J, Joseph S, Koenig SC, Pagani FD. Updated Definitions of Adverse Events for Trials and Registries of Mechanical Circulatory Support: A consensus statement of the Mechanical Circulatory Support Academic Research Consortium J Heart Lung Transplant 39: 735–750, 2020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Farrar DJ, Compton PG, Hershon JJ, Fonger JD, Hill DJ: Right heart interaction with the mechanically assisted left heart. World J Surg 9: 89–102, 1985. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Moon M, Bolger A, DeAnda A,Komeda M, Daughtersll GT, Nikolic SD, Miller DC, Ingels NB: Septal function during left ventricular unloading. Circulation 95: 1320–1327, 1997. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Morgan JA, Paone G, Nemeh HW, Murthy R, Williams CT, Lanfear DE, Tita C, Brewer RJ: Impact of continuous-flow left ventricular assist device support on right ventricular function. J Heart Lung Transplant 32: 398–403, 2013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Peura JL, Colvin-Adams M, Francis GS, Grady KL, Hoffman TM, Jessup M, John R, Kiernan MS, Mitchell JE, O’Connell JB, Pagani FD, Petty M, Ravichandran P, Rogers JG, Semigran MJ, Toole JM. Recommendations for the use of mechanical circulatory support: device strategies and patient selection. Circulation 126: 2648–2667, 2012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ochiai Y, McCarthy PM, Smedira NG, Banbury MK, Navia JL, Feng J, Hsu AP, Yeager ML, Buda T, Hoercher KJ, Howard MW, Takagaki M, Doi K, Fukamachi K: Predictors of severe right ventricular failure after implantable left ventricular assist device insertion: analysis of 245 patients. Circulation 106: I198–202, 2002. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Schenk S, McCarthy PM, Blackstone EH, Feng J, Starling RC, Navia JL, Zhou L, Hoercher KJ, Smedira NG, Fukamachi K: Duration of inotropic support after left ventricular assist device implantation: Risk factors and impact on outcome. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg 131: 447–454, 2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Matthews J, Koelling TM, Pagani FD, Aaronson KD. The Right Ventricular Failure Risk Score: a [re-operative tool for assessing the risk of right ventricular failure in Left Ventricular Assist Device candidates. J Am Coll Cardiol 51: 2163–2172, 2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Grant A, Smedira NG, Starling RC, Marwick TH. Independent and incremental role of quantitative right ventricular evaluation for the prediction of right ventricular failure after Left Ventricular Assist Device implantation. J Am Coll Cardiol 60: 521–52, 2012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Raina A, Rammohan H, Gertz ZM, Rame EJ, Woo JY, Kirkpatrick JN: Postoperative right ventricular failure after Left Ventricular Assist Device placement is predicted by preoperative echocardiographic structural, hemodynamic, and functional Parameters. J Card Fail 19: 16–24, 2013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kiernan MS, French AL, DeNofrio D, Parmar YJ, Pham DT, Kapur NK, Pandian NG, Patel AR: Preoperative three-dimensional echocardiography to assess risk of right ventricular failure after Left Ventricular Assist Device surgery. J Card Fail 21: 189–197, 2015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Bleeker G, Steendijk P, Holman E, Yu CM, Breithardt OA, Kaandorp TA, Schalij MJ, van der Wall EE, Nihoyannopoulos P, Bax JJ. Assessing right ventricular function: the role of echocardiography and complementary technologies. Heart 92(suppl 1): i19, 2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Cameli M, Lisi M, Righini F, Solari M, Alvino F, Lisi M, D’Ascenzi F, Bernazzali S, Tsioulpas C, Sassi C, Dokollari A, Sani G, Maccherini M, Mondillo S. Speckle tracking echocardiography as a new technique to evaluate right ventricular function in patients with left ventricular assist device therapy. J Heart Lung Transplant 32: 424–430, 2013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Mondillo S, Galderisi M, Mele D, Cameli M, Lomoriello VS, Zaca V, Ballo P, D’Andrea A, Muraru D, Losi M, Agricola E, D’Errico A, Buralli S, Sciomer S, Nistri S, Badano L. Speckle-tracking echocardiography J Ultras Med 30: 71–83, 2011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kang G, Ha R, Banerjee D. Pulmonary artery pulsatility index predicts right ventricular failure after left ventricular assist device implantation. J Heart Lung Transplant 35: 67–73, 2016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Atluri P, Goldstone AB, Fairman AS, MacArthur JW, Shudo Y, Cohen JE, Acker AL, Hiesinger W, Howard JL, Acker MA, Woo YJ. Predicting right ventricular failure in the modern, continuous flow Left Ventricular Assist Device era. Ann Thorac Surg 96: 857–864, 2013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Mazurek JA, Vaidya A, Mathai SC, Roberts JD, Forfia PR: Follow-up tricuspid annular plane systolic excursion predicts survival in pulmonary arterial hypertension. Pulm Circ 7: 361–371, 2017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Sing T, Sander O, Beerenwinkel N, Lengauer T: ROCR: visualizing classifier performance in R. Bioinformatics 21: 3940–3941, 2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.López-Ratón M, Rodríguez-Álvarez M, Suárez C, Sampedro F: OptimalCutpoints: An R package for selecting optimal cutpoints in diagnostic tests. J Stat Softw 61: 1–36 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Gamer M, Lemon J, Singh P. Various Coefficients of Interrater Reliability and Agreement. http://cran.R-project.org/package=irr, 2019. Accessed January 10, 2021.

- 26.Kato TS, Jiang J, Schulze PC, Jorde U, Uriel N, Kitada S, Takayama H, Naka Y, Mancini D, Gillam L, Homma S, Farr M: Serial echocardiography using tissue doppler and speckle tracking imaging to monitor right ventricular failure before and after left ventricular assist device surgery. JACC Heart Fail 3: 216–222, 2013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Morris DA, Krisper M, Nakatani S, Kohncke C, Otsuji Y, Belyavskiy E, Radha Krishnan AK, Kropf M, Osmanoglou E, Boldt LH, Blaschke F, Edelmann F, Haverkamp W, Tschope C, Pieske-Kraigher E, Pieske B, Takeuchi M: Normal range and usefulness of right ventricular systolic strain to detect subtle right ventricular systolic abnormalities in patients with heart failure: a multicentre study. European Hear J - Cardiovasc Imaging 18: 212–223, 2017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Fine NM, Chen L, Bastiansen PM, Frantz RP, Pelilkka PA, Oh JK, Kane GC: Outcome prediction by quantitative right ventricular function assessment in 575 subjects evaluated for pulmonary hypertension. Circulation Cardiovasc Imaging 6: 711–721, 2013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Hamada-Harimura Y, Seo Y, Ishizu T, Nishi I, Machino-Ohtsuka T, Yamammoto M, Sugano A, Sato K, Sai S, Obara K, Yoshida I, Aonuma K: Incremental prognostic value of right ventricular strain in patients with acute decompensated heart failure. Circulation Cardiovasc Imaging 11: e007249, 2018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Vizzardi E, D’Aloia A, Caretta G, Bordonali T, Bonadei I, Rovetta R, Quinzani F, Bugatti S, Curnis A, Metra M: Long-term prognostic value of longitudinal strain of right ventricle in patients with moderate heart failure. Hellenic J Cardiol 55: 150–155, 2014. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Morris DA, Gailani M, Vaz Pérez A, Blaschke F, Dietz R, Haverkamp W, Ozcelik C: Right ventricular myocardial systolic and diastolic dysfunction in heart failure with normal left ventricular ejection fraction. J Am Soc Echocardiog 24:886–897, 2011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.