Abstract

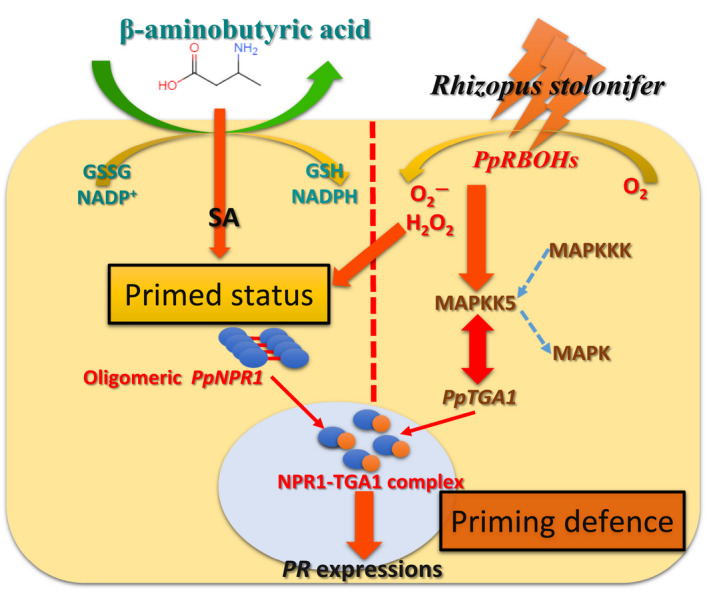

The priming of defence responses in pathogen‐challenged model plants undergoes a preparation phase and an expression phase for defence function. However, the priming response in postharvest fruits has not been elucidated. Here, we found that 50 mM β‐aminobutyric acid (BABA) treatment could induce two distinct pathways linked with TGA1‐related systemic acquired resistance (SAR), resulting in the alleviation of Rhizopus rot in postharvest peach fruit. The first priming phase was elicited by BABA alone, leading to the enhanced transcription of redox‐regulated genes and posttranslational modification of PpTGA1. The second phase was activated by an H2O2 burst via up‐regulation of PpRBOH genes and stimulation of the MAPK cascade on pathogen invasion, resulting in a robust defence. In the MAPK cascade, PpMAPKK5 was identified as a shortcut interacting protein of PpTGA1 and increased the DNA binding activity of PpTGA1 for the activation of salicylic acid (SA)‐responsive PR genes. The overexpression of PpMAPKK5 in Arabidopsis caused the constitutive transcription of SA‐dependent PR genes and as a result conferred resistance against the fungus Rhizopus stolonifer. Hence, we suggest that the BABA‐induced priming defence in peaches is activated by redox homeostasis with an elicitor‐induced reductive signalling and a pathogen‐stimulated H2O2 burst, which is accompanied by the possible phosphorylation of PpTGA1 by PpMAPKK5 for signal amplification.

Keywords: MAPKK, peach, priming resistance, redox, Rhizopus stolonifer, TGA1, β‐aminobutyric acid

BABA elicitation regulates the redox homeostasis and shortcut interaction of TGA1 and MAPKK5 for a SAR‐related priming defence in postharvest peaches.

Abbreviations

- 6PGDH

6‐phosphaogluconate dehydrogenase

- AbA

aureobasidin A

- APX

ascorbate peroxidase

- AsA‐GSH

ascorbic acid‐glutathione

- BA2H

benzoic acid 2‐hydroxylase

- BABA

β‐aminobutyric acid

- BLAST

basic local alignment search tool

- BTH

benzothiadiazole

- CAT

catalase

- Co‐IP

coimmunopreicipitation

- CRISPR

clustered regularly interspaced short palindromic repeats

- DDO

double dropout medium

- DHAR

dehydroascorbate reductase

- DLR

dual‐luciferase reporter

- dpi

days postinoculation

- dscDNA

double‐stranded cDNA

- ET

ethylene

- ETI

effector‐triggered immunity

- G6PDH

glucose‐6‐phosphate dehydrogenase

- GR

glutathione reductase

- GST

glutathione

- H2O2

hydrogen peroxide

- His

histidine

- ISR

induced systemic resistance

- iTOL

interactive tree of life

- JA

jasmonic acid

- MAPK

mitogen‐activated protein kinase

- MDHAR

monodehydroascorbate reductase

- MEGA

Molecular Evolutionary Genetics Analysis

- MS

Murashige and Skoog

- NADPH

reduced coenzyme II

- NCBI

National Center for Biotechnology Information

- NJ

neighbour‐joining

- NPR1

nonexpressor of pathogenesis‐related genes 1

- PAMPs/MAMPs

pathogen‐ or microbe‐associated molecular patterns

- PBS

phosphate‐buffered saline

- PDA

potato dextrose agar

- PGLS

6‐phosphogluconolactonase

- PGPR

plant‐growth‐promoting rhizobacteria

- POD

peroxidase

- PPP

pentose phosphate pathway

- PR

pathogenesis‐related gene

- PRRs

pattern‐recognition receptors

- PTI

pattern‐triggered immunity

- QDO

quadruple dropout medium

- qPCR

quantitative PCR

- RBOH

respiratory burst oxidase homologue

- ROS

reactive oxygen species

- SA

salicylic acid

- SAR

systemic acquired resistance

- SD/−Leu−Trp

synthetic dropout medium lacking leucine and tryptophan

- SD/−Leu−Trp−His

synthetic dropout medium lacking leucine, tryptophan, and histidine

- SD/−Leu−Trp−His−Ade

synthetic dropout medium lacking leucine, tryptophan, histidine, and adenine

- SMART

simple modular architecture research tool

- SOD

superoxide

- TAL

transaldolase

- TBtools

toolkit for biologists

- TDO

triple dropout medium

- TFs

transcription factors

- TKT

transketolase

- WT

wild‐type

- XTT

3′‐[1‐(phenylamino‐carbonyl)‐3,4‐tetrazolium]‐bis(4‐methoxy‐6‐nitro) benzenesulfonic acid hydrate

- X‐α‐gal

X‐α‐d‐galactosidase

- Y1H

yeast one‐hybrid

- Y2H

yeast two‐hybrid

1. INTRODUCTION

To effectively defend against invading pathogenic microorganisms, plants have evolved intricate mechanisms that have given rise to multilayered and tightly controlled signalling networks of constitutive and induced resistance (Glazebrook, 2005). The first layer, referred to as pathogen‐associated molecular pattern‐triggered immunity (PTI), is performed by the specific recognition of plasma membrane‐localized pattern recognition receptors (PRRs) by pathogen‐associated molecular patterns (PAMPs)/microbe‐associated molecular patterns (MAMPs) and is characterized by an oxidative burst, rapid MAPK activation, callose deposition, stomatal closure, and PTI‐responsive gene transcription within minutes of PAMP/MAMP perception (Gust et al., 2007; Zipfel & Robatzek, 2010). Plants have also evolved a second level of innate immunity, called effector‐triggered immunity (ETI), which depends on the specific recognition of pathogen effectors by host resistance (R) proteins, leading to hypersensitive cell death at the site of pathogen infection to confine the spread of pathogens (Coll et al., 2011). Salicylic acid (SA)‐dependent systemic acquired resistance (SAR) also confers long‐lasting resistance to a wide spectrum of pathogen challenges (Vallad & Goodman, 2004). SA signalling is related to the proper activation of the majority of SA‐inducible genes during PTI, and the transcription of SA response marker genes in R protein‐mediated ETI can be partly regulated in an SA‐dependent manner (Glazebrook, 2005; Tsuda et al., 2013). SAR is usually accompanied by SA‐dependent defence responses via an NPR1‐dependent mechanism and results in resistance predominantly against biotrophic pathogens (Dong, 2004; Ton et al., 2002). Another defence system, induced systemic resistance (ISR), can be triggered by the colonization of plant roots by plant growth‐promoting rhizobacteria (PGPR) and can be regulated by jasmonic acid (JA) and ethylene (ET) signalling pathways (Pieterse et al., 2000; Verhagen et al., 2004). Over the decades, priming has been documented as a universal feature of the plant immune response that confers SAR/ISR against pathogenic threats (Conrath et al., 2006). For example, SA and its analogue benzothiadiazole (BTH) can prime Arabidopsis for potentiated transcription of SA‐responsive PR genes (Kohler et al., 2002). A mutation‐based experiment indicated a crucial role of NPR1 in the SA‐signalling priming defence (Canet et al., 2010). ISR induced by the PGPR Pseudomonas fluorescens WCS374 was determined to prime JA‐ and/or ET‐regulated defence genes in Arabidopsis against further pathogen attack (Pozo et al., 2008). β‐aminobutyric acid (BABA), a nonproteinogenic amino acid, exerts inducible effects by priming a SAR defence with SA‐signalling PR gene transcription and/or SA‐independent callose deposition at infected sites (Cohen et al., 2016). In our previous studies, after treatment with a suitable concentration of BABA (ranging from 10 to 50 mM), fruits, such as peach (Prunus persica), strawberry (Fragaria × ananassa), and table grape (Vitis vinifera), were found to enter a special physiological condition, referred to as the primed state, that enabled them to remain dormant under low disease pressure but respond in a more rapid and robust manner to a considerably higher grade of stimulus than nonprimed fruits (Li et al., 2020c, 2021; Wang et al., 2016, 2019, 2021). Nevertheless, the identity of the key regulatory node underlying BABA‐induced priming resistance remains unclear.

Rhizopus stolonifer is a necrotrophic fungal pathogen, and Rhizopus soft rot caused by the pathogen on the succulent tissues of vegetables, fruits, and ornamentals usually occurs during the postharvest period. After harvest, R. stolonifer is omnipresent as a saprophyte and sometimes as a plant parasite (Kwon & Lee, 2006). Specifically, Rhizopus rot is one of the dominant postharvest mould diseases in peach, resulting in great loss after harvest (Baggio et al., 2017). Previously, we revealed that protection of peach fruit by BABA against the invasion of the fungal pathogen R. stolonifer was accompanied by the transcript accumulation of nuclear‐translocated TGA1, a key redox‐controlled factor of SAR, which is essential for the activation of priming resistance in postharvest peach fruit (Li et al., 2020b). The MAPK signalling cascade, a highly conserved eukaryotic pathway featuring a distinct cascade of three successive phosphorylation events, is involved in the phosphorylation of certain specific transcription factors (TFs) and eventually converts external stimulations into intracellular responses. The MAPK cascade serves as the convergence point of multiple signalling transduction pathways (Jonak et al., 2002; Mutalik & Venkatesh, 2006; Sugiura et al., 1999). Nevertheless, whether or not the regulatory role of the MAPK cascade is intertwined with TGA1 in the BABA‐induced priming response remains unknown. In a preliminary trial, a novel group C MAPK kinase of PpMAPKK5 was identified as a PpTGA1 binding partner that was positively involved in induced resistance against R. stolonifer in peaches. Herein, we elucidated the role of BABA in inducing SAR‐related priming resistance in peach fruit and provided a broad picture of the switch between the primed state and activation of the priming defence.

2. RESULTS

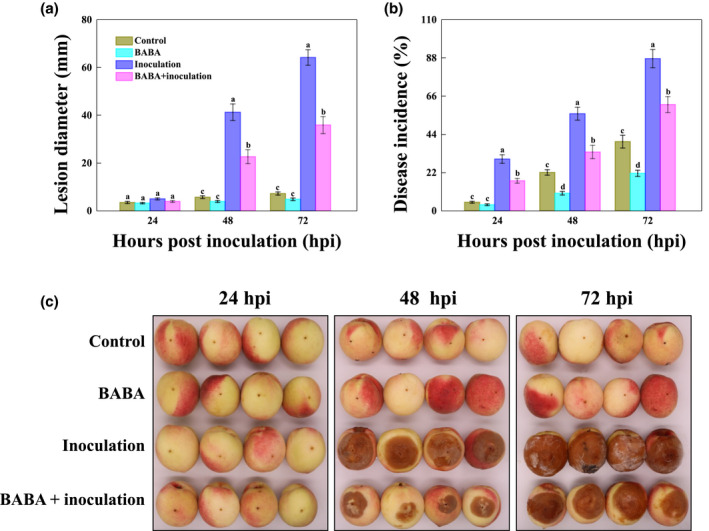

2.1. Inhibitory effect of BABA elicitation against R. stolonifer infection in peaches

Peaches are susceptible to Rhizopus soft rot caused by the fungus R. stolonifer, as depicted in Figure 1a,b. Pretreatment with 50 mM BABA resulted in significant suppression of disease severity in peaches, and the lesion diameter and disease occurrence were 28.28% and 26.44%, respectively, lower than those of peaches inoculated with R. stolonifer alone at 72 hr postinoculation (hpi). Notably, treatment with 50 mM BABA clearly retarded the occurrence of brown‐rot decay and/or black‐and‐white hyphae on the surface of fruit pericarps, especially at 48 and 72 hpi (Figure 1c).

FIGURE 1.

BABA elicitation retarded disease development in peaches inoculated with the fungal pathogen Rhizopus stolonifer. (a) Lesion diameter, (b) disease incidence, and (c) visual appearance measured at 24 hr intervals after inoculation of peach fruit with R. stolonifer. Peaches were dot‐inoculated with double‐deionized water (purple bars) or 50 mM BABA (pink bars) before inoculation with R. stolonifer. Lesion diameter and disease incidence were recorded as the mean ± SE. Different lowercase letters above the bar indicate a significant (p < 0.05) difference among BABA‐treated, R. stolonifer‐inoculated, and control peaches. Representative peaches were photographed and compared at 24, 48, and 72 hr postinoculation (hpi) of storage at 20°C

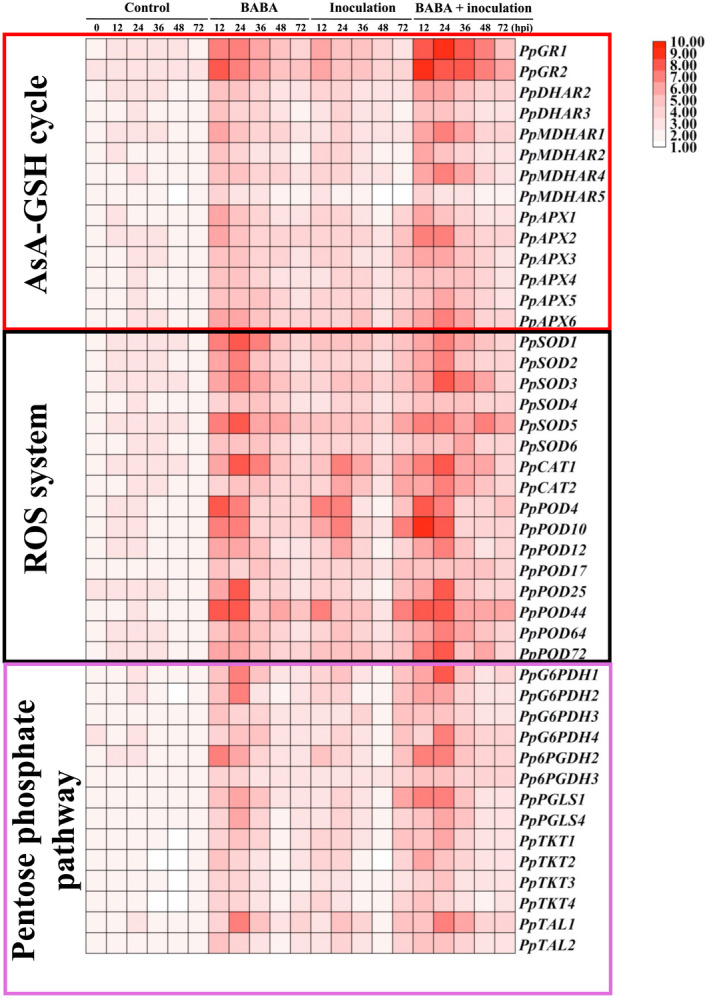

2.2. Effect of BABA elicitation on the regulation of redox status in peaches

As shown in Figure 2, higher transcript levels of genes encoding key enzymes related to the ascorbate‐glutathione (AsA‐GSH) cycle (GR, DHAR, MDHAR, and APX), reactive oxygen species (ROS) system (SOD, CAT, and POD), and pentose phosphate pathway (PPP; G6PDH, 6PGDH, PGLS, TKT, and TAL) in sole R. stolonifer‐inoculated or BABA‐treated peaches could be observed compared with those in the controls. In all BABA‐pretreated samples, transcript levels of these genes involved in the AsA‐GSH cycle, ROS system, and PPP generally peaked at approximately 12–24 hpi, followed by gradual decrease. The involvement of the potentiated transcription of critical genes in the AsA‐GSH cycle, ROS system, and PPP in BABA‐pretreated peaches with subsequent pathogen inoculation was in agreement with our previous observations of their activities (Li et al., 2020b). As a consequence, BABA stimulated the redox potential of the fruit cells towards a highly reductive condition on their perception of pathogen invasion.

FIGURE 2.

Transcript levels of key enzymes associated with the ascorbic acid‐glutathione (AsA‐GSH) cycle, reactive oxygen species (ROS) system, and pentose phosphate pathway in peaches after inoculation with Rhizopus stolonifer at 12 hr intervals. mRNA transcripts were profiled by quantitative reverse transcription PCR and visualized with a heatmap, in which peach TEF2 was used as an internal standard. Data represent means from six measurements

2.3. Effect of BABA elicitation on H2O2 burst and SA‐dependent defence response in peaches

The BABA‐elicited SAR of peach fruit against R. stolonifer was observed along with an oxidative burst, as demonstrated by the potentiation of NADPH oxidase activity, the transcription of PpRBOHs and the accumulation of H2O2 content (Figure 3a–c). Moreover, BABA‐mediated protection of peaches against R. stolonifer activated the transcription of Pp MAPKKK5s and Pp MAPKK5 (Figure 3c). The effect of BABA on the mRNA transcripts of SA biosynthesis genes (PAL, ICS, CM, BA2H, and IPL), NPR1 (a master regulator of SAR), and SA‐responsive genes, such as PpPR1s, PpPR2s, and PpPR5s, of peaches infected by R. stolonifer is presented in Figure 3d. All of the SA biosynthesis genes began to show transcript accumulation as soon as BABA treatment was applied, and their expression was highly induced following inoculation with R. stolonifer. In addition, BABA‐primed SAR responses against R. stolonifer invasion were observed by analysing the transcription of the PpNPR1 and SA‐responsive PpPR1, PpPR2, and PpPR5 genes, and the observed kinetics and intensity were similar to those of the transcript profile of Pp MAPKKK5s/Pp MAPKK5 (Figure 3c,d).

FIGURE 3.

Changes in NADPH oxidase activity, H2O2 content and transcript levels of PpMAPKKK5s/PpMAPKK5, salicylic acid (SA) biosynthesis, and SA‐responsive genes in peaches after inoculation with Rhizopus stolonifer at 12 hr intervals. NADPH oxidase activity (a) and H2O2 content (b) were recorded as the mean ± SE. Asterisks indicate significant (p = 0.05 level) differences among BABA‐treated, R. stolonifer‐inoculated, and untreated peaches. mRNA expression levels, including PpMAPKKK5s/PpMAPKK5 (c) and SA biosynthesis and SA‐responsive genes (d), were profiled using quantitative reverse transcription PCR and visualized with heatmap. Peach TEF2 was used as an internal standard. Data represent means from six measurements

2.4. Screening for PpTGA1‐interacting proteins from peach fruit

As shown in Figure S1, after double selection on TDO plates supplemented with 10 or 20 mM 3‐AT, a total of 205 single colonies were selected. The library plasmids were transformed into Escherichia coli DH5α for colony PCR, sequencing, and searching with BlastN (nucleotide BLAST), where 89 single colonies were amplified and 61 positive colonies were successfully sequenced. A total of 53 different coding sequences from BLAST alignments were eventually obtained. Further verification showed that only 34 positive colonies were present on double verification plates (TDO + 10/20 mM 3‐AT). Notably, one colony (no. 158) was homologous with P. persica mitogen‐activated protein kinase kinase 5 (MAPKK5, LOC18781583).

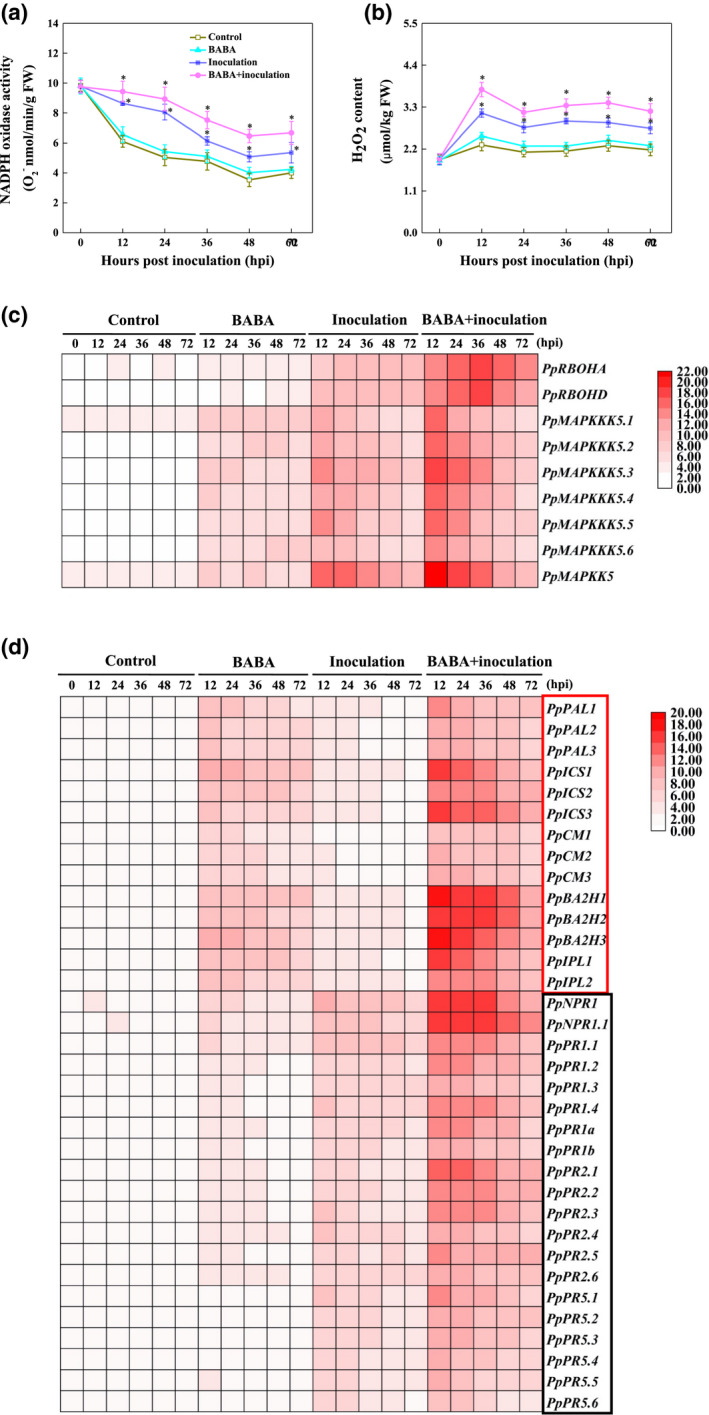

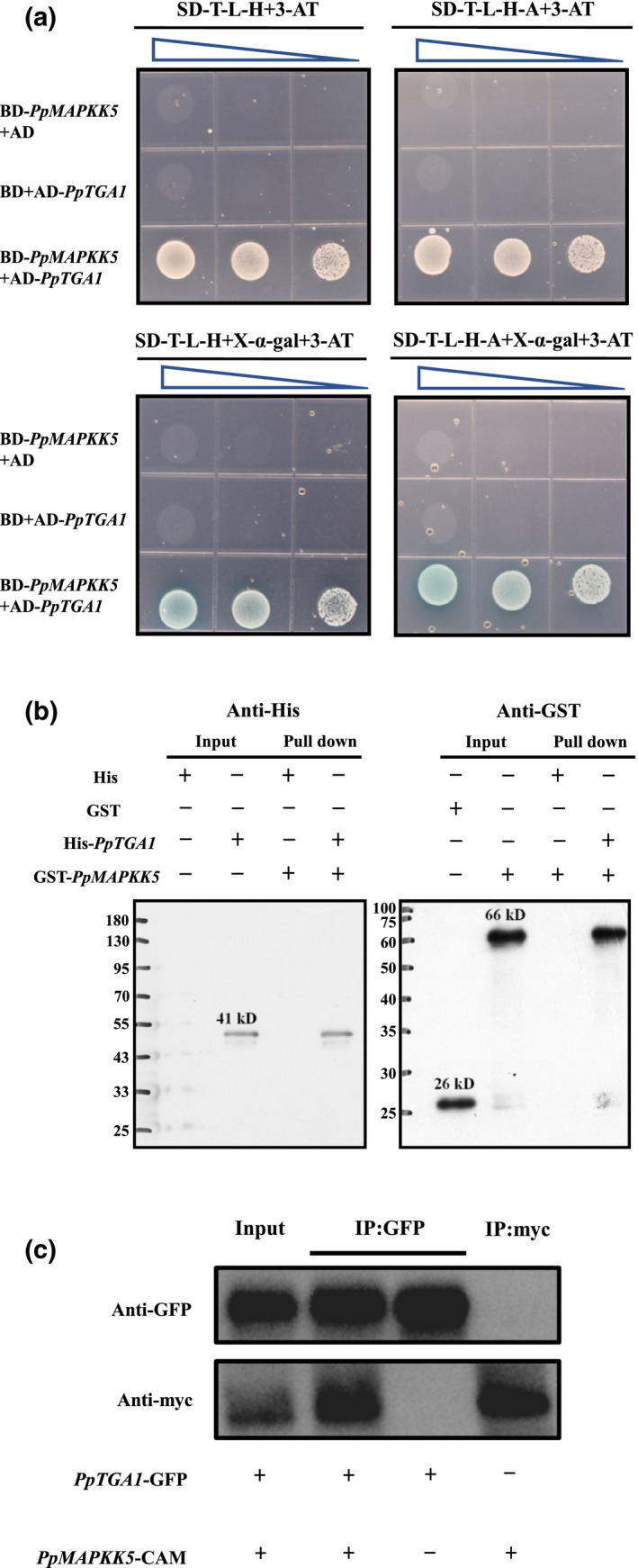

2.5. Confirmation of the PpTGA1/PpMAPKK5 interaction in vivo and in vitro

In the yeast two‐hybrid (Y2H) system, the interaction between PpTGA1 and PpMAPKK5 stimulated the reporter genes HIS3, ADE2, and MEL1, as competent yeast AH109 cotransfected with BD‐PpMAPKK5 and AD‐PpTGA1 vectors presented colony clusters on synthetic dropout plates (SD/−Trp/−Leu/−His + 4 mM 3‐AT and SD/−Trp/−Leu/−His/−Ade + 4 mM 3‐AT) within 4–6 days, and these colonies turned blue on X‐α‐gal plates. In contrast, cells cotransformated with expected negative pairs (BD‐PpMAPKK5 + the empty pGADT7 vector and AD‐PpTGA1 + the empty pGBKT7 vector) barely grew on the TDO/QDO plates (Figure 4a). The western blot results from a His pull‐down assay indicated that a specific binding band could not be detected in the absence of PpTGA1, revealing that PpTGA1 interacted with PpMAPKK5 in vitro (Figure 4b). The coimmunoprecipitation (Co‐IP) assay confirmed the interaction between PpTGA1 and PpMAPKK5 in living plant cells (Figure 4c). PpTGA1 possesses five high‐stringency phosphorylatible residues (Table S1). The amino acid motifs, including the kinase binding site group (Kin_bind), phosphoserine/threonine binding group (pST_bind), and basophilic serine/threonine kinase group (Baso_ST_kin), are located in the transcription factor TGA‐like domain (IPR code IPR025422) of PpTGA1 but do not theoretically cover the basic leucine zipper domain (IPR code IPR004827; Figure S2).

FIGURE 4.

Confirmation of the interaction between PpTGA1 and PpMAPKK5. (a) Yeasts cultured on TDO (SD–T–L−H plate) or QDO (SD–T–L–H–A plate) with or without X‐α‐gal and 4 mM 3‐AT. The triangles above Petri dishes indicate the amount of yeast cells determined by spectrophotometry at an optical density of 600 nm with 10‐fold serial dilutions (from optical density of 1 to 0.01). (b) His‐PpTGA1 recombinant protein preimmobilized on Ni‐sepharose 6 Fast Flow and further incubated with GST‐fused‐PpMAPKK5 at 4°C for at least 8 h. The incubated resins were pelleted for immunoblot analysis with anti‐His or anti‐GST antibody. (c) Co‐immunoprecipitation assay substantiated the PpTGA1 and PpMAPKK5 interaction in tobacco (Nicotiana tabacum)

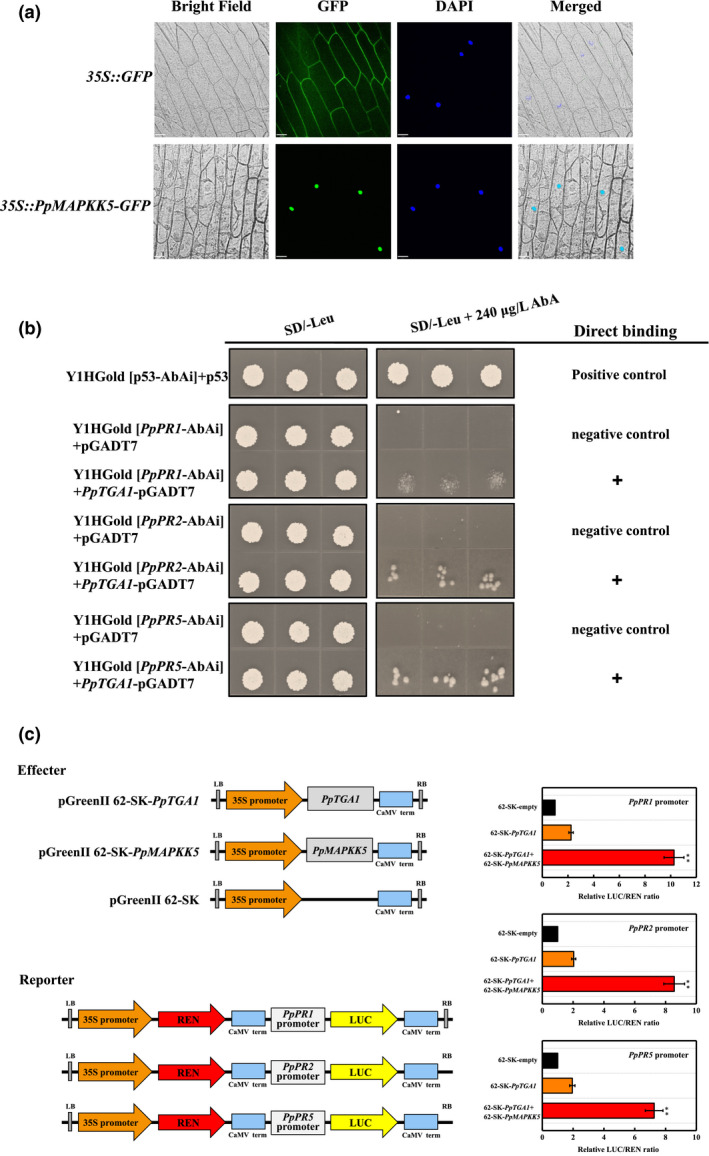

2.6. Nucleus‐localized PpMAPKK5 acts cooperatively with PpTGA1 to activate the PR gene transcription

As presented in Figure 5a, the control construct harbouring the 35S::GFP cassette exhibited expression in both the cytoplasm and nucleus of stained onion peels; in contrast, the 35S::PpMAPKK5‐GFP construct exhibited fusion protein expression that was observed exclusively in the nucleus, as highlighted by 4′,6‐diamidino‐2‐phenylindole (DAPI) staining. The binding of PpTGA1 to the PpPR1, PpPR2, and PpPR5 promoters in a yeast one‐hybrid (Y1H) assay led to slight activation of the AbA reporter gene (Figure 5b). Moreover, when the PpPR1, PpPR2, or PpPR5 Pro‐LUC reporter construct was coinfiltrated with PpMAPKK5 and PpTGA1, the LUC/REN ratios were intensely induced and were much higher than those observed with PpTGA1 alone (Figure 5c). These results indicate that PpMAPKK5 could apparently enhance the transactivation of PpTGA1 to the target PR genes.

FIGURE 5.

Nucleus‐localized PpMAPKK5 acts synergistically with PpTGA1 to activate the expression of PpPR promoters. (a) Transient expression of the fusion protein (35S::PpMAPKK5‐GFP) and positive control (35S::GFP) in onion peels was mediated by Agrobacterium tumefaciens infiltration. Green fluorescent protein (GFP) signals were captured using laser‐scanning microscopy (Zeiss), and the white bar represents 70 μm in the horizontal direction. (b) Direct binding of PpTGA1 to PpPR1/PpPR2/PpPR5 promoters was determined according to the ability of Y1H Gold [PpPR1/PpPR2/PpPR5‐AbAi] + PpTGA1‐pGADT7 to grow on SD/−Leu in the presence of 240 μg/L AbA. (c) Dual‐luciferase reporter assay for the transactivation of PpTGA1 and PpMAPKK5 to the PpPR1, PpPR2, and PpPR5 promoters. Activation is indicated by the ratio of LUC:REN; the empty plasmid combined with the promoter of PpPR1, PpPR2 or PpPR5 was set to 1 for the calibration of the ratio. Data represent the mean ± SE of nine independent repeats. ** indicates significant difference between samples (p = 0.01)

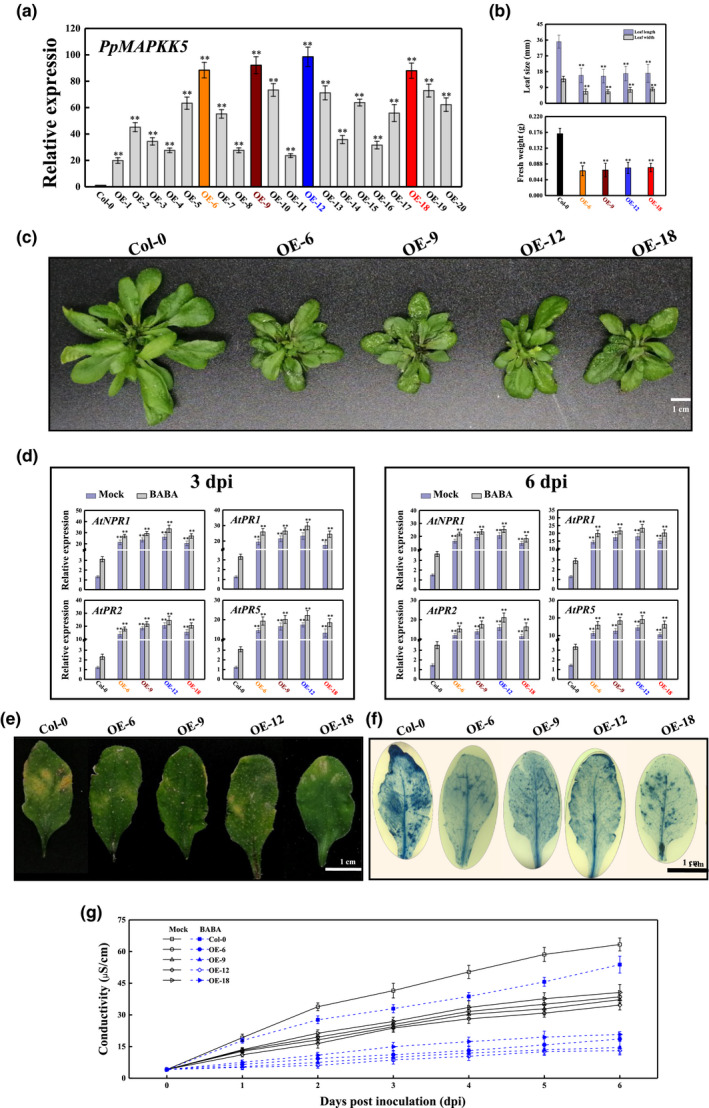

2.7. Heterologous expression of PpMAPKK5 elevates the resistance level to R. stolonifer and relieves cell death in Arabidopsis

PpMAPKK5 from Prunus persica is an orthologous gene of Arabidopsis thaliana AtMAPKK5; both cluster in group C (Figure S3). In this study, quantitative reverse transcription PCR (RT‐qPCR) analysis indicated that the PpMAPKK5 transcript profile was markedly higher in A. thaliana PpMAPKK5‐overexpressing lines, especially in OE‐6, OE‐9, OE‐12, and OE‐18, compared with that in A. thaliana Col‐0 wild‐type (Figure 6a). Unexpectedly, the heterologous expression of Pp MAPKK5 retarded the growth of transgenic Arabidopsis, with the growth parameters in terms of dwarf leaves, leaf sizes, and biomasses being smaller than those of wild‐type (WT) plants (Figure 6b,c). The mRNA levels of AtNPR1 and AtPRs increased in the four PpMAPKK5‐overexpressing lines (OE‐6, OE‐9, OE‐12, and OE‐18) at 3 and 6 days postinoculation (dpi) compared with those in WTs. There was an apparent accumulation of At NPR1 and At PR transcripts after treating PpMAPKK5‐overexpressing lines with BABA (Figure 6d). R. stolonifer‐infected leaves were imaged after staining with lactophenol‐trypan blue for the determination of pathogen growth and cell death‐related activity. At 6 dpi, approximately half of the cells in WTs were blue‐stained; in contrast, lesions and necrotic areas were significantly reduced in all transgenic lines (Figure 6e,f). The cell electrolyte leakage of R. stolonifer‐infected transgenic leaves was obviously lower than that of WTs regardless of whether the WTs or overexpressing lines (OEs) were previously treated with BABA (Figure 6g). These results confirm that the overexpression of PpMAPKK5 could contribute to the alleviation of cell damage and disease development.

FIGURE 6.

PpMAPKK5 overexpression potentiates the expression of PRs and enhances Arabidopsis resistance to Rhizopus stolonifer. (a) PpMAPKK5 transcription in 4‐week‐old wild‐type (WT) and transgenic plants. Transcription was normalized against the value of the reference gene AtActin2 and recorded as the mean ± SE. (b, c) The overexpression of PpMAPKK5 hindered Arabidopsis growth, as indicated by the smaller leaf length and lower biomass in OE6, OE9, OE12, and OE18 as compared with those of WT plants (bar = 1 cm). (d) Quantitative reverse transcription PCR reflects the transcription of NPR1 and PRs in WTs and OEs infected by R. stolonifer at 3 and 6 days postinoculation (dpi) with or without BABA treatment. **, significant (p < 0.01) difference between the WTs and OEs. (e) The disease symptoms of WT and PpMAPKK5‐overexpressing Arabidopsis at 6 dpi. (f) Arabidopsis leaves of WTs and OEs were stained with trypan blue to reveal necrotic areas. (g) Electrolyte leakage levels of Arabidopsis leaves from WTs and OEs

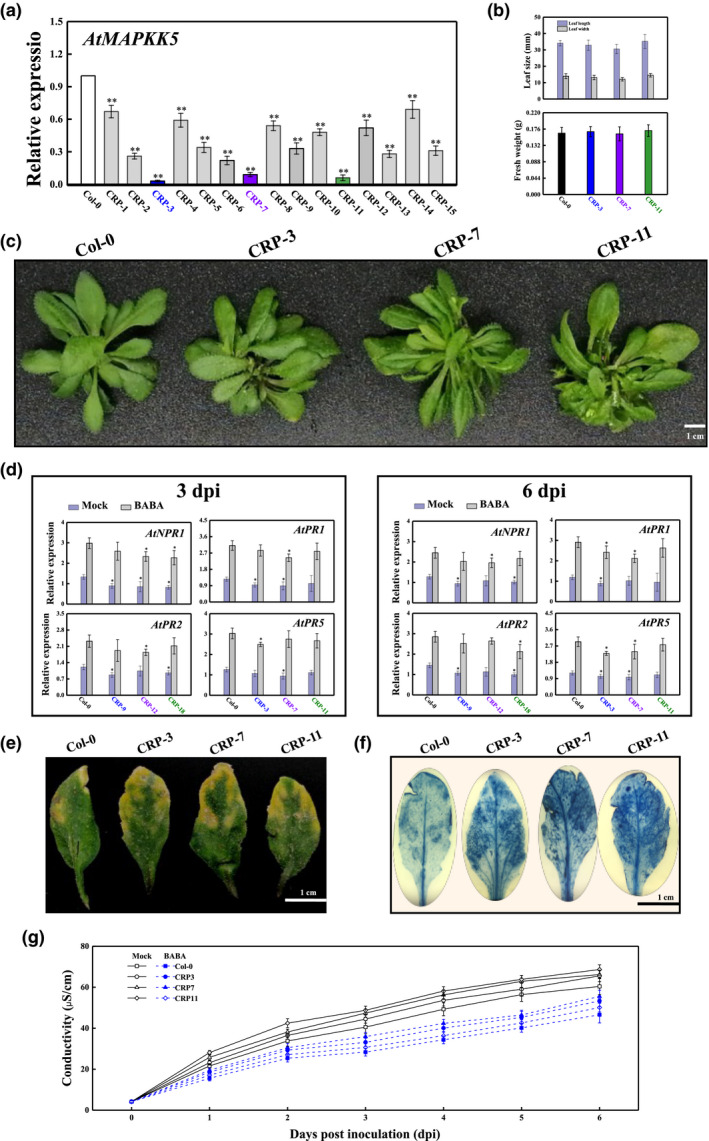

2.8. AtMAPKK5 loss‐of‐function mutants showed decreased resistance to fungal pathogen

MAPKK5‐knockout lines generated by the CRISPR/Cas9 system were collected to examine the role of MAPKK5 during fungal pathogen invasion. As presented in Figure 7a, the expression profile of AtMAPKK5 in the knockout lines, including CRP‐3, CRP‐7, and CRP‐11, drastically decreased by more than 91% compared with those in WTs. Conversely, CRP‐3, CRP‐7, and CRP‐11 exhibited few alterations in growth phenotype, including leaf length, width, and biomass (Figure 7b,c). The CRISPR/Cas9‐mediated MAPKK5 knockout plants had similar expression patterns of a battery of PR genes, all of which slightly declined at 3 and 6 dpi (Figure 7d). Surprisingly, all knockout lines positively responded to BABA soil drench treatment, but the expression products of the NPR1 and PR genes in these lines showed little significant difference from those of WT Col‐0 (Figure 7d). Consistent with these observations, the disease symptoms and staining levels of the dot‐inoculated knockout plants were slightly stronger than those of WT leaves (Figure 7e,f). As expected, the cell electrolyte leakage from knockout plants was also higher than that from WT plants, and plants treated with BABA were no exception (Figure 7g).

FIGURE 7.

CRISPR/Cas9‐mediated MAPKK5 knockout lines showed slightly decreased resistance to the fungal pathogen Rhizopus stolonifer. (a) AtMAPKK5 transcription in 4‐week‐old wild‐type (WT) and knockout lines. (b, c) MAPKK5 knockout did not change the speed of growth of Arabidopsis. (d) Transcription of NPR1 and PRs in WTs and knockout plants (CRP3, CRP7, and CRP11) after inoculation with R. stolonifer at 3 and 6 days postinoculation (dpi). (e) Disease symptoms of WTs and knockout plants at 6 dpi. (f) Necrotic areas in WTs and knockout plants were assessed by trypan blue staining at 6 dpi. (g) Electrolyte leakage levels of WTs and knockout plants infected with R. stolonifer at 6 dpi

3. DISCUSSION

Priming has an advantage over direct defence because of the balance of defence expression and its allocated metabolic costs (Buswell et al., 2018); however, there are only a few hypotheses regarding the underlying molecular mechanism. One hypothesis is that early elicitation by specific chemicals can prime and increase the accumulation of intracellular genes/proteins employed in the biosynthesis of various small signal molecules, including SA. Next, infection under high abiotic pressure stimulates latent signalling regulators, thus amplifying signal transduction cascades and providing augmented expression of host defence (Conrath et al., 2006; Mateo et al., 2006; Pastor et al., 2013). In this study, treatment of peaches with BABA alone significantly up‐regulated a number of genes related to the ROS enzymatic scavenging system, the PPP for the NADPH supply, and the AsA‐GSH cycle for the production of GSH and AsA during 72 hr of incubation (Figure 2). Moreover, BABA alone primed peaches to accumulate a higher SA level due to the induced transcription of a set of SA biosynthesis‐related genes. In contrast, artificial fungal inoculation alone did not up‐regulate the genes involved in redox regulation simultaneously, but the H2O2 burst was observed in the peaches challenged with R. stolonifer alone (Figure 3). Thus, it is probable that there are two distinct pathways associated with BABA‐ or pathogen‐induced defence in harvested peach fruit. Specifically, BABA elicitation alone elevated the reductive status and possibly activated some critical redox‐responsive regulators, while R. stolonifer infection only stimulated the ROS burst and defensive response. Such contrasting responses are reconciled by the redox homeostasis in an SA‐dependent priming SAR in the BABA‐treated and subsequently R. stolonifer‐infected peaches, by which the generation of reductive substances primed the plant defence and an ROS burst magnified this defensive response. These data were also consistent with the finding of Tada et al. (2008), who highlighted the importance of redox homeostasis in priming expression in plants.

The modified intercellular redox conditions trigger the accumulation of a few pivotal regulators in their active conformation, which trains the plant innate immune system in a primed state (González‐Bosch, 2018). NADPH oxidases, a kind of plasma membrane‐bound RBOH protein, employ specific activity for the movement of NADPH‐released electrons to oxygen and the generation of superoxide anions, which are subsequently dismutated to H2O2 by SOD (Kadota et al., 2015; Marino et al., 2012). AtRBOHD‐ or AtRBOHF‐derived H2O2 accumulation has been determined to be a critical component of defence against biotic stress in Arabidopsis (Morales et al., 2016; Yao et al., 2017). Our work also provided evidence that an H2O2 burst could be closely connected with the enhanced transcript levels of PpRBOHA and PpRBOHD (the peach orthologous genes of AtRBOHF and AtRBOHD, respectively) and the potentiated activities of NADPH oxidases (Figures 3 and S4). However, the up‐regulation of PpRBOH gene expression and the corresponding H2O2 burst occurred in only R. stolonifer‐inoculated peaches, indicating a possible function of ROS in PTI or ETI. The BABA‐primed peaches exhibited high PpRBOHA and PpRBOHD expression levels and H2O2 peaks during the first 12 hr of incubation on infection with R. stolonifer, accompanied by enhanced resistance against the development of disease symptoms (Figures 1 and 3). Therefore, these results suggest that an RBOH‐dependent ROS burst orchestrates fruit adaptation in the priming phase to augment the defensive response. On the other hand, MAPK cascades, known as the three‐kinase pathway of MAPKKK‐MAPKK‐MAPK, are critical signalling components that can amplify and transduce various signals produced by receptor‐like modules into a suitable intracellular response for combating stress or for development/reproduction requirements in eukaryotic plants (Gouda et al., 2020). Herein, we demonstrated that a set of PpMAPKKK5 and PpMAPKK5 genes were up‐regulated in BABA‐treated peaches (Figure 3c). Moreover, the induction of the PpMAPKKK5/PpMAPKK5 genes in peaches elicited with BABA and subsequently inoculated with R. stolonifer was stronger than that observed after sole R. stolonifer challenge or BABA induction. Furthermore, this enhancement of PpMAPKKK5/PpMAPKK5 genes by the combined treatment was consistent with the change in PpRBOH expression levels and H2O2 generation, indicating a direct connection between PpMAPK activation and PpRBOH expression for defence function. Similarly, PAMP‐responsive MAPKs, including Solanum lycopersicum MAPK1/2 (Zhou et al., 2014), Nicotiana benthamiana MAPKKs (Adachi et al., 2016; Lee & Back, 2016), N. benthamiana WIPK and SIPK (Sharma et al., 2003; Zhang et al., 2012), Oryza sativa MAPK3/6 (Gupta et al., 2019), and MAPK3/4/6 of Arabidopsis (Beckers et al., 2009; Colcombet & Hirt, 2008; Liu et al., 2020), also acted as downstream sensors of early ROS/H2O2 rapid generation during signalling immune responses. Therefore, the RBOH‐dependent H2O2 burst associated with pathogen recognition in primed peaches can be manifested as a hypersensitive messenger in response to disease stress that stimulates the MAPK cascade for the enhancement of signalling immunity.

A conserved MAPK cascade is composed of a three‐linear signalling module, where the final downstream kinases of MAPKs have been proposed to phosphorylate targeted functional proteins and therefore transduce endogenous hormonal signals, promote gene transcription, and transfer metabolic flow towards defensive responses (Kishi‐Kaboshi et al., 2010; Meng & Zhang, 2013). Interestingly, an interaction between MAPKKK1 and targeted WRKY53 provided a clue that MAPKKKs or MAPKKs can be released from redundant MAPK cascades for direct modification of downstream TFs (Miao et al., 2007). TGAs, representing a subclass of the basic leucine zipper (bZIP) TF family, contribute to interaction with NPR1 and form NPR1–TGA transcriptional complexes to activate downstream PR genes (Després et al., 2003; Zhang et al., 1999). Several bZIP TFs, including AtVIP1 from Arabidopsis and MaBZIP93 and MaBZIP74 from Musa acuminata, could act as the substrates of MAPKs and require phosphorylation modification for their regulatory functions (Djamei et al., 2007; Liang et al., 2020; Wu et al., 2019). The interaction between PpMAPKK5 and its probable substrate PpTGA1 could be observed not only in yeast cells but also in tobacco tissues (Figures 4 and S1). Meanwhile, the His pull‐down results confirmed the formation of the PpMAPKK5‐PpTGA1 complex in vitro (Figure 4). PpTGA1, containing several phosphorylation motifs, including Kin_bind, pST_bind, and Baso_ST_kin, could be the target of pathogen‐responsive MAPKK5 (Figure S2 and Table S1). These data suggested that PpMAPKK5 interacts with PpTGA1 through probable phosphorylation modification. In particular, neither PpMAPKKKs nor PpMAPKs interacted with PpTGA1 in the Y2H library screen (Figure S1). Thus, we deduced that the direct signalling of PpMAPKK5 to PpTGA1 could bypass the normal MAPK cascade for possible posttranslational phosphorylation. In the Y1H system and DLR assay, PpTGA1 was identified as a DNA‐binding protein that served as a transcriptional activator of PpPR genes; moreover, PpMAPKK5 could confer an increased transactivation capacity to PpTGA1 (Figure 5). Additionally, PpMAPKK5 was stably located in the nucleus, which was in accordance with the nuclear localization of PpTGA1 after redox‐dependent translocation as described previously (Li et al., 2020b). The same nuclear localization shared by PpMAPKK5 and its downstream target PpTGA1 implied that the interaction occurred predominantly in nuclei and strengthened NPR1–TGA1 transactivation. As a result, PpMAPKK5 can be recognized as a candidate signalling enzyme that mediates the TGA1‐dependent priming defence in peach fruit. The overexpression of PpMAPKK5 in transgenic Arabidopsis caused constitutive transcription of SA‐responsive PR genes and lowered their sensitivity to R. stolonifer, whereas Arabidopsis MAPKK5 loss‐of‐function mutants displayed compromised expression of PR genes (Figures 6 and 7). The results further support the conclusion that the SAR defence in peach fruit could result from PpMAPKK5 activation at least in part. However, BABA elicitation dramatically induced PR gene expression in the MAPKK5 knockout lines (Figure 7d), which raises the question of whether BABA stimulates the SAR reaction by another branched defence pathway.

Based on the molecular and genetic trials conducted in the present study, we suggest that the typical BABA‐mediated priming resistance of peach fruit involves the primed intracellular redox homeostasis associated with intracellular signal transudation and subsequent amplification of the signalling events to activate a more rapid and stronger defence on pathogen invasion (Figure 8). This priming of host–pathogen interaction processes can be attributed to a TGA1‐dependent SAR reaction, in which the direct interaction of PpTGA1 and PpMAPKK5 may increase the DNA‐binding activity of PpTGA1 for PR gene transcription. A few publications and this study have provided possible molecular mechanisms involved in the priming defence in horticultural crops, but the translation of defence priming to practical use will be a crucial issue for future research.

FIGURE 8.

A simplified model of redox homeostasis and shortcut interaction between TGA1 and MAPKK5 involved in BABA‐induced priming defence in postharvest peach fruit

4. EXPERIMENTAL PROCEDURES

4.1. Plant and pathogen materials

P. persica ‘Baifeng’ peaches were procured and hand‐picked from a standard peach orchard located in Tongnan District, Chongqing City in China. These peaches were transferred to our laboratory under chilled conditions and were individually distributed on an experimental console at 20°C until used for BABA treatment and pathogen inoculation.

The Columbia‐0 (Col‐0) ecotype of A. thaliana was the genetic background for the transgenic and mutant plants presented in our current work. Col‐0 WT seeds were surface‐sterilized with sodium hypochlorite and cold‐stratified for approximately 3 days at 4°C before being sown in soil and cultured in an illumination incubator (SPT‐P500B, Darth Carter Co.) under a long‐day (LD) photoperiod (60%–70% RH, 2500–3000 lx, 22°C under 14 h/10 h light/dark cycles) for more than 4 weeks. In addition to Arabidopsis, tobacco (Nicotiana tabacum) employed for Agrobacterium tumefaciens‐mediated transient transformation was cultivated in an illumination incubator with the same LD conditions for 5–9 weeks in accordance with our previously described methodology (Li et al., 2020a).

R. stolonifer was isolated and identified according to our recent works (Li et al., 2020a). The R. stolonifer mycelia were incubated on potato dextrose agar (PDA) for 3–4 days (26°C) and rinsed thoroughly with sterile water with 0.5% (vol/vol) Tween 80 for the preparation of R. stolonifer spore suspensions, which were diluted to 105 spores/ml (for the inoculation treatment of peach fruit) and 2 × 105 spores/ml (for the detection of pathogen resistance in transgenic and mutant Arabidopsis) using a Neubauer chamber.

4.2. BABA treatment and spore inoculation

Intact peaches with identical size and maturity without visible mechanical damage were surface‐sterilized with 75% (vol/vol) alcohol, air‐dried for more than 3 h at 20°C, and further partitioned into four groups of 360 peaches each. Two uniform holes were punched per peach by perforating 3 mm deep and 3 mm wide wounds around the centre of each peach at two symmetrical sites with a sterile, dissecting needle. The specific concentration of BABA (50 mM, purity of ≥99%; Sigma Co.) was chosen on the basis of our previous studies, which demonstrated that 50 mM BABA could effectively elicit a priming defence in peaches (Li et al., 2020a). The wounds of each group were injected with distilled water (control), the BABA solution (BABA elicitation), the spore suspensions of R. stolonifer (R. stolonifer inoculation), or BABA followed by R. stolonifer inoculation (BABA + inoculation; Li et al., 2020a, 2020b). After treatment, all peaches were arrayed on an experimental console for approximately 6 h, sealed in polyethylene boxes (60 μm thickness), and placed in incubators for 72 h at 20 ± 1°C with 80%–90% RH. Finally, 30–50 g tissue from the uninfected sarcocarp (2–3 mm in length away from the infected area) of 60 peaches in each group was sampled with a sterile scalpel before incubation (0 h) and at 12 h intervals during 72 h of incubation at 20°C. Fruit pulps sampled from each individual were then frozen in liquid N2 and stored at −80°C until further analysis. Each treatment comprised three replicates with a completely randomized design and the entire experiment was executed twice with similar results.

4.3. Evaluation of disease development

The peach was recorded as diseased when the width of the inoculated area exceeded 3 mm. The disease incidence was calculated by determining the proportion of decaying peaches. Disease development, including the lesion diameter and disease incidence, in each triplicate sample was observed sequentially for 72 h at 24 h intervals.

4.4. Measurement of NADPH oxidase activity

Plasma membrane vesicles were isolated from peaches with two‐phase partitioning according to a previously described method (Morré & Morré, 2000). The NADPH‐dependent O2 −‐generating activity in membrane vesicles was measured by the reduction of XTT by O2 − (adapted from Sagi & Fluhr, 2001; Zhang et al., 2009). NADPH oxidase activity was expressed as O2 − nmol/min/g fresh weight (FW).

4.5. Determination of H2O2 content

The titanium (IV) method described previously by Patterson et al. (1984) was conducted for measurement of endogenous H2O2 content, which was presented as μmol/kg FW.

4.6. RNA isolation and RT‐qPCR

Total RNA was isolated using the RNAprep Pure Kit for plants (Tiangen) from powdered frozen tissues (5 g) and single‐stranded cDNA was synthesized by aliquots (1 μg) of RNA using a PrimeScript RT Reagent Kit (Takara). Quantitative PCR (qPCR) was performed with SYBR Green in triplicate on a 7500 FAST Real‐Time PCR system (Applied Biosystems). Gene‐specific primer pairs (listed in Table S2) were designed using Primer3 software available in the NCBI database with expected amplicon lengths between 90 and 150 bp to minimize the impact of the RNA and ensure optimal polymerization efficiency. The qPCR mixture and the thermal cycling parameters were prepared and set according to our previous study (Li et al., 2021). The gene expression levels were calculated using the 2−ΔΔ C t method (Livak & Schmittgen, 2001). For normalization of the qPCR results, peach TEF2 (adapted from Tong et al., 2009) or Arabidopsis Actin2 genes were used as internal standards.

4.7. Construction and evaluation of peach fruit cDNA library

Total RNA from BABA‐pretreated plus R. stolonifer‐inoculated pulp at 12 hpi was extracted using the TRIzol method (Invitrogen). One microgram of total RNA was reverse‐transcribed to dscDNA with a SMART cDNA Library Construction Kit (Clontech). dscDNA was purified using VAHTS DNA Clean Beads (Vazyme) and further recombined into the linearized pGADT7 vector, and the recombinant product was transformed into E. coli DH5α electroporation‐competent cells to generate the Y2H library. The constructed cDNA library was subjected to a plating assay to determine the optimal titre (cfu/ml, Gao et al., 2015). For confirmation of the cDNA inserts, the 24 randomly picked cDNA clones were subjected to colony PCR (initial denaturation at 95°C for 3 min; followed by 25 cycles of 95°C for 15 s, 55°C for 15 s and 72°C for 1 min; and then extension for 5 min at 72°C). Further electrophoresis‐based detection revealed that most of the inserts appeared as a single band and ranged from 0.1 to 1.5 kb in size (Figure S5).

4.8. Bait plasmid construction and the determination of its self‐activation activity

The synthesized PpTGA1 was cloned into the BamHI‐SmaI sites of the yeast expression vector pGBKT7 to form the bait plasmid (pGBKT7‐PpTGA1). The competent cells of Saccharomyces cerevisiae AH109 were transformed with pGBKT7‐PpTGA1 using the lithium acetate method, and the transformants were plated on SD/−Trp medium. Single colonies were selected and confirmed using Matchmaker Insert Check PCR Mix 2 (Takara). The autotranscriptional activation of the positive pGBKT7‐PpTGA1 colonies was tested on SD/−Trp/−His (double dropout, DDO), SD/−Trp/−His/−Ade (triple dropout, TDO), and TDO + X‐α‐gal plates with or without the serial addition of 3‐amino‐1,2,4‐triazole (3‐AT) at 29°C.

4.9. Screening of the cDNAs for PpTGA1

The bait strain harbouring pGBKT7‐PpTGA1‐2 was transformed with 25 μg library plasmid in a yeast‐mating procedure. The cotransformants were plated on SD/−Trp/−Leu/−His plates containing 10 or 20 mM 3‐AT and incubated at 29°C for 5–9 days (Figure S1). All single colonies were then transferred twice to new TDO (SD/−Trp/−Leu/−His plate) supplemented with 10 or 20 mM 3‐AT for double selection. The pGADT7‐cDNA plasmids encoding the interacting proteins of PpTGA1 were extracted from shake‐cultured (in SD/−Trp/−Leu/−His liquid medium, 29°C/225 rpm) colonies through a yeast plasmid isolation kit (Omega), transformed into E. coli DH5α cells and further subjected to colony PCR, DNA sequencing, and BLAST analysis before verification on synthetic dropout plates.

4.10. Y2H assay

Y2H analysis was further performed by employing the Matchmaker GAL4‐based Y2H system (Clontech) to examine the interaction between the identified PpMAPKK5 and PpTGA1. The coding regions of PpMAPKK5 and PpTGA1 were fused to the pGBKT7 and pGADT7 vectors to construct the bait (BD‐PpMAPKK5) and prey (AD‐PpTGA1) expression vectors, respectively. The two constructs were inserted into S. cerevisiae AH109 cells and then plated on synthetic dropout media with the addition of X‐α‐gal (40 mg/L) as previously described (Wang et al., 2021).

4.11. Pull‐down assay

The synthesized PpMAPKK5 or PpTGA1 was cloned into the pGEX‐4T‐1 or pET‐28a vector to produce the corresponding glutathione S‐transferase (GST)‐ or His‐tagged proteins, respectively. Then, the two fusion proteins were expressed in E. coli BL21 (DE3) and protein expression was induced with 0.1 mM isopropyl β‐d‐galactopyranoside (IPTG) for 16 h at 20°C. Bacteria expressing the GST fusion protein (PpMAPKK5) were lysed through sonication and purified with glutathione agarose (Thermo Fisher Scientific) based on the instructions. For the pull‐down assay, the recombinant His‐PpTGA1 was immobilized with Ni‐Sepharose beads (Ni‐Sepharose 6 Fast Flow; GE Healthcare) for 2 h at 4°C. Subsequently, the recombinant GST‐PpMAPKK5 or GST was incubated with prewashed beads for more than 8 h at 4°C before being washed with ice‐cold phosphate‐buffered saline (PBS). After boiling in 2 × Laemmli buffer, 6 μl of the pulled‐down proteins was examined by western blotting using anti‐GST antibodies (TransGen Biotech Co., Ltd), and His +recombinant GST‐PpMAPKK5 served as the negative control.

4.12. Co‐IP assay

A Co‐IP assay was performed as previously described (Wang et al., 2021). The full‐length coding sequences of PpMAPKK5 and PpTGA1 were introduced into pCAMBIA35s‐4 × myc and pBinGFP2, respectively. The recombinant proteins (PpMAPKK5‐CAM harbouring myc‐label and PpTGA1‐GFP harbouring GFP‐label) were transformed into Agrobacterium tumefaciens GV3101 and infiltrated into 8‐week‐old tobacco leaves. The infected leaves were cultivated for an additional 48 h under LD conditions. The isolated leaf proteins were either exposed directly to 12% SDS‐PAGE for western immunoblotting analysis or immunoprecipitated overnight with horseradish peroxidase (HRP) anti‐GFP antibody (1:2,000; Invitrogen) or HRP anti‐myc antibody (1:2,000; Invitrogen). The immune complexes were collected using protein A/G‐agarose (PA/G, Santa Cruz Biotechnology) and washed eight times with commercial wash buffer. For immunoblotting, the isolated proteins or pellets were suspended in 1 × SDS‐PAGE loading buffer, separated on SDS‐polyacrylamide gels and transferred to nitrocellulose membranes. The membranes were immunoblotted with anti‐GFP antibody or anti‐myc antibody and visualized using the ECL‐Plus western blotting system (GE‐Healthcare).

4.13. Subcellular localization of PpMAPKK5

PCR‐amplified PpMAPKK5 was inserted into the binary expression vector pCAMBIA1301‐35S‐GFP at the 5′‐terminus of the green fluorescent protein (GFP) driven by the 35S promoter of cauliflower mosaic virus (CaMV). The fusion protein vector of 35S::PpMAPKK5‐GFP and the empty vector of 35S::GFP were introduced into A. tumefaciens EHA105 and further transformed into onion bulb epidermis cells as described previously (Li et al., 2021). After 3 days of cultivation on Murashige & Skoog (MS) medium in the dark (26°C), onion bulbs were stained with 20 μg/ml DAPI nuclear dye (Sigma). The fluorescence signals of the stained onion peels were visualized by fluorescence microscopy (LSM 510; Zeiss) with excitation wavelengths at 488 nm for the GFP signal and 405 nm for the DAPI fluorescence at 3 h after staining. Herein, 35S::GFP served as the positive control.

4.14. Y1H assay

The Y1H assay was conducted using the Matchmaker gold Y1H system (Clontech). Three copies of the TGACG‐motif cis‐acting elements and their adjacent nucleotides (approximately 50 bp) were synthesized on the basis of the promoter fragments of PpPRs (Data S1) and ligated into the pAbAi vector. Then, PpPR1‐AbAi, PpPR2‐AbAi, PpPR5‐AbAi, and p53‐AbAi were linearized by BbsI and transformed into the Y1H Gold strain. The construction of recombinant PpTGA1‐pGADT7, determination of the minimal inhibitory concentration (MIC) of AbA and detection of direct binding among PpTGA1, PpPR1, PpPR2, and PpPR5 were performed according to our previous study (Wang et al., 2021).

4.15. Dual‐luciferase reporter assay

Transactivation of the PpPR1, PpPR2, and PpPR5 promoters by PpTGA1 and PpMAPKK5 was determined according to a dual‐luciferase system, in which the coding sequence fragments of PpTGA1 and PpMAPKK5 in BABA plus R. stolonifer‐inoculated peaches were introduced into the pGreenII 62‐SK vector to serve as effectors (pGreenII 62‐SK‐PpTGA1/PpMAPKK5), and the PpPR1, PpPR2, and PpPR5 promoters were inserted into the pGreenII 0800‐LUC vector to construct reporters (pGreenII 0800‐LUC‐PpPR1/PpPR2/PpPR5). The effectors and reporters were then transformed into A. tumefaciens GV3101. The GV3101 cells harbouring effectors were mixed in equal proportions and further blended with each reporter and infiltrated into 5‐ to 9‐week‐old tobacco plants (abaxial leaf surfaces). The binding activities of PpTGA1 and PpMAPKK5 to the PpPR promoters were measured as described by Shan et al. (2016) and reported as the LUC:REN ratio. At least nine independent repeats were performed for each pair.

4.16. Transgenic Arabidopsis overexpressing P. persica MAPKK5

The entire coding region (1062 bp) of PpMAPKK5 amplified from peach cDNA was fused downstream of the enhanced CaMV 35S promoter in the plant overexpression vector pCAMBIA 1305.1 to obtain the heterologous overexpression plasmid 35S::PpMAPKK5. Arabidopsis plants were immersed in A. tumefaciens GV3101 cells harbouring the 35S::PpMAPKK5 construct with the floral dip method (Clough & Bent, 1998). The T1 seeds were harvested and sterilized in 2% sodium hypochlorite for approximately 10 min before stratification at 4°C (3 days) and further germinated on half‐strength MS medium (½MS; Murashige & Skoog, 1962) supplemented with kanamycin (Kan, 50 mg/L) for approximately 7 days. The Kan‐resistant seedlings were then sown in 11‐cm germination pots containing a prepared soil mixture of vermiculite and perlite in a 2:1 ratio and placed in a chamber under LD conditions. Homozygous transgenic plants in the T3 generation were prepared for follow‐up experiments.

4.17. Generation of MAPKK5 knockout mutants using the CRISPR‐Cas9 system

The specific guide RNA (sgRNA) cassettes on the strand of targeted AtMAPKK5 were chosen according to GC abundance and sequences corresponding to the protospacer adjacent motif (PAM) sites (set as ‘NGG’), and their off‐target effects were confirmed using the web server CRISPR‐P (http://crispr.hzau.edu.cn/CRISPR2/). The annealed sgRNA cassettes were ligated into the BsaI‐digested M2CRISPR binary vector to generate the CRISPR/Cas9 vector of U26 promoter‐driven T1 sgRNA and U29 promoter‐driven T2 sgRNA (the vector construction diagram is shown in Figure S6). Details regarding the primers used for the generation of MAPKK5 loss‐of‐function mutants are listed in Table S2. The CRISPR/Cas9 construct was transformed into Arabidopsis using A. tumefaciens‐mediated transformation. Then, T1 generation transformants were selected on MS medium with hygromycin phosphtotransferase (HYG, 50 mg/L). Genomic DNA was isolated from 4‐week‐old knockout lines, followed by PCR amplification with KOD FX (Toyobo Co. Ltd) using the gene‐specific primers listed in Table S2 to detect mutational events. After the verification of homozygous mutants, T3 mutant seedlings were harvested.

4.18. Inoculation of Arabidopsis with R. stolonifer after drenching the plants with BABA

After soil drench treatment with 30 μg/mL BABA according to the previous method of Zimmerli et al. (2001), 4‐week‐old soil‐grown T3 transgenic and WT Arabidopsis Col‐0 plants were dot‐inoculated with 10‐μl droplets of R. stolonifer conidial suspensions (2 × 105 conidia/ml) at fixed and symmetrical positions on leaf midveins as described by Xiao and Chye (2011). Then, detached leaves were prepared for the detection of resistance‐related gene transcription at 3‐day intervals and leaves at 6 dpi were prepared for morphological observations.

4.19. Trypan blue staining

Pathogen‐infected Arabidopsis leaves at 6 dpi were immersed in boiling trypan blue staining solution as described previously by Cai et al. (2020) and further soaked in chloral hydrate solution (1.25 g/ml) for approximately 1.5 days and photographed using binocular stereomicroscopy (EZ4D; Leica).

4.20. Electrolyte leakage measurement

Leaf discs (8 mm diameter) of R. stolonifer‐infiltrated leaves from WTs, OEs, and knockout plants were washed twice with 50 ml double‐deionized water and then floated on double‐deionized water as described by Mackey et al. (2002). The water conductivity was measured by a conductivity meter (MIK‐TDS210‐B).

4.21. Data analysis

All data were separated with t test and one‐way analysis of variance (Tukey's test) using the SPSS package program for Windows v. 13.0 (SPSS Inc.); values were shown as the mean ± SE of the six replicates from two independent experiments. Different letters and asterisks indicate significant differences between treatments at p = 0.05 or 0.01.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

The authors declare that there is no conflict of interest.

Supporting information

FIGURE S1 Yeast two‐hybrid screening of the PpTGA1 protein. (a) The expression abundance of PpTGA1 potentiated under treatment of peaches with BABA following R. stolonifer inoculation within 72 hr postinoculation. (b) Self‐activation detection of the bait plasmid pGBKT7‐PpTGA1 and the truncated plasmid pGBKT7‐PpTGA1‐1/pGBKT7‐PpTGA1‐2 on synthetic dropout plates (SD/−Trp/−His and SD/−Trp/−His/−Ade) with or without X‐α‐gal and 3‐AT. Given the strong self‐activation of the recombinant pGBKT7‐PpTGA1 and the DNA‐binding domains observed in PpTGA1, we developed two truncation schemes for PpTGA1. Although the truncated plasmid pGBKT7‐PpTGA1‐1 similarly presented self‐activation, the self‐activation activity of pGBKT7‐PpTGA1‐2 was inhibited by the addition of 10 mM 3‐AT and completely repressed by 20 mM 3‐AT. (c) Yeast containing the bait plasmid (pGBKT7‐PpTGA1‐2) and prey library were screened on TDO supplied with 10 or 20 mM 3‐AT. (d) Verification of the positive interacting proteins of PpTGA1 on synthetic dropout plates

FIGURE S2 Motif scan graphical analysis of PpTGA1 was conducted using SCANSITE 4.0 (https://scansite4.mit.edu)

FIGURE S3 Phylogenetic and sequence alignment of PpMAPKK5 with AtMAPKKs, SlMAPKKs, NtMAPKKs, and OsMAPKKs. (a) Four groups of MAPKKs are shown in the phylogenetic tree. PpMAPKK5 is highlighted in red and classified into group C. The protein sequences of 10 MAPKKs from Arabidopsis thaliana, seven from Solanum lycopersicum, six from Nicotiana tabacum, seven from Oryza sativa, and PpMAPKK5 were aligned using ClustalW, and the phylogenetic tree was generated with MEGA 5.0 (neighbour‐joining method; 1,000 bootstraps) and visualized using iTOL. (b) Sequence alignment among these group C MAPKKs was conducted using DNAMAN v. 6.0, and the identical amino acids are shaded in dark blue

FIGURE S4 Phylogenetic analysis of PpRBOHs and AtRBOHD/AtRBOHF, in which PpRBOHD and PpRBOHA showed similar clustering with AtRBOHD and AtRBOHF, respectively

FIGURE S5 Identification of the inserted dscDNA size of the reading frame. Twenty‐four clones were randomly selected from LB plates and amplified by colony PCR. The PCR product was analysed by 1.2% agarose gel electrophoresis to determine the recombination frequency and fragment size. Lanes 1–24, inserted dscDNA; M, DNA ladder (DL500; Vazyme)

FIGURE S6 Schematic diagram of the CRISPR‐AtMAPKK5 vector

FIGURE S7 Agarose gel electrophoresis of total RNA and dscDNA and the plating assay of the constructed cDNA library. M, DNA ladder (DL500; Vazyme). (a) Agarose gel electrophoresis (AGE) presented three discrete ribosomal RNA bands (28/18S and 5S) with little nonspecific degradation, which verified the integrity and quality of the total RNA isolated from Prunus persica. (b) The dscDNA fragments ranged in size from 0.1 to 2.0 kb on a 1.2% agarose gel. (c) The plating assay of the constructed cDNA library performed in 10‐fold serial dilutions from 10−1 to 10−4 reflected that the optimal dilution factor was 100 times. Based on the colony number on 100 µg/ml ampicillin selection plates, the cDNA library titre was calculated as 5.08 × 106 cfu/ml, and the quantity of this Y2H library was approximately 1.25 × 107 cfu

FIGURE S8 PpTGA1 contains a BRLZ domain (basic‐leucine zipper domain, possessing DNA‐binding transcription factor activity) and a DOG1 domain (transcription factor TGA‐like domain, possessing sequence‐specific DNA‐binding activity), which was analysed with SMART (http://smart.embl‐heidelberg.de)

FIGURE S9 His‐ and GST‐tagged proteins were detected by gel image analysis

TABLE S1 The motif sites of PpTGA1 predicted by SCANSITE 4.0

TABLE S2 Sequences of the primers used in the study

DATA S1 Three tandem copies of the AS‐1 element (TGACG) are present in the promoter regions of PpPR1, PpPR2, and PpPR5, and the AS‐1 elements are indicated in the black box in red. Restriction sites are underlined

DATA S2 Truncation scheme of PpTGA1 for further yeast two‐hybrid screening

DATA S3 The promoter regions of PpPR1, PpPR2, and PpPR5. The AS‐1 element (TGACG) is marked in red and boxed, and the translation start sites are underlined with a yellow box

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

The research was funded by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (nos. 31671913 and 31672209), the Natural Science Foundation of Ningbo City (no. 2018A610224), and the Funds for Innovative Research Groups of University in Chongqing City (CXQT21036). We thank Yunxia Liao, Si Chen, and Dongzhi Wu for sample preparation in the past 5 years. We also especially thank Prof. Wei Deng (Chongqing University), Dr. Zhongqi Fan (Fujian A&F University) and Dr. Leigang Zhang (JAAS) for their helpful advice or scientific editing.

Li, C. , Wang, K. , Huang, Y. , Lei, C. , Cao, S. , Qiu, L. , et al (2021) Activation of the BABA‐induced priming defence through redox homeostasis and the modules of TGA1 and MAPKK5 in postharvest peach fruit. Molecular Plant Pathology, 22, 1624–1640. 10.1111/mpp.13134

DATA AVAILABILITY STATEMENT

The data that supports the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

REFERENCES

- Adachi, H. , Ishihama, N. , Nakano, T. , Yoshioka, M. & Yoshioka, H. (2016) Nicotiana benthamiana MAPK‐WRKY pathway confers resistance to a necrotrophic pathogen Botrytis cinerea . Plant Signaling & Behavior, 11, e1183085. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baggio, J. , Hau, B. & Amorim, L. (2017) Spatiotemporal analyses of Rhizopus rot progress in peach fruit inoculated with Rhizopus stolonifer . Plant Pathology, 66, 1452–1462. [Google Scholar]

- Beckers, G.J.M. , Jaskiewicz, M. , Liu, Y. , Underwood, W.R. , He, S.Y. , Zhang, S.Q. et al. (2009) Mitogen‐activated protein kinases 3 and 6 are required for full priming of stress responses in Arabidopsis thaliana . The Plant Cell, 21, 944–953. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buswell, W. , Schwarzenbacher, R.E. , Luna, E. , Sellwood, M. , Chen, B. , Flors, V. et al. (2018) Chemical priming of immunity without costs to plant growth. New Phytologist, 218, 1205–1216. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cai, J.H. , Chen, T. , Wang, Y. , Qin, G.Z. & Tian, S.P. (2020) SlREM1 triggers cell death by activating an oxidative burst and other regulators. Plant Physiology, 183, 717–732. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Canet, J.V. , Dobón, A. , Roig, A. & Tornero, P. (2010) Structure–function analysis of npr1 alleles in Arabidopsis reveals a role for its paralogs in the perception of salicylic acid. Plant, Cell & Environment, 33, 1911–1922. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clough, S.J. & Bent, A.F. (1998) Floral dip: a simplified method for Agrobacterium‐mediated transformation of Arabidopsis thaliana . The Plant Journal, 16, 735–743. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cohen, Y. , Vaknin, M. & Mauch‐Mani, B. (2016) BABA‐induced resistance: milestones along a 55‐year journey. Phytoparasitica, 44, 513–538. [Google Scholar]

- Colcombet, J. & Hirt, H. (2008) Arabidopsis MAPKs: a complex signalling network involved in multiple biological processes. Biochemical Journal, 413, 217–226. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coll, N.S. , Epple, P. & Dangl, J.L. (2011) Programmed cell death in the plant immune system. Cell Death and Differentiation, 18, 1247–1256. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Conrath, U. , Beckers, G.J.M. , Flors, V. , García‐Agustín, P. , Jakab, G. , Mauch, F. et al. (2006) Priming: getting ready for battle. Molecular Plant‐Microbe Interactions, 19, 1062–1071. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Després, C. , Chubak, C. , Rochon, A. , Clark, R. , Bethune, T. , Desveaux, D. et al. (2003) The Arabidopsis NPR1 disease resistance protein is a novel cofactor that confers redox regulation of DNA binding activity to the basic domain/leucine zipper transcription factor TGA1. The Plant Cell, 15, 2181–2191. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Djamei, A. , Pitzschke, A. , Nakagami, H. , Rajh, I. & Hirt, H. (2007) Trojan horse strategy in Agrobacterium transformation: abusing MAPK defense signaling. Science, 318, 453–456. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dong, X.N. (2004) NPR1, all things considered. Current Opinion in Plant Biology, 7, 547–552. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gao, J.X. , Jing, J. , Yu, C.J. & Chen, J. (2015) Construction of a high‐quality yeast two‐hybrid library and its application in identification of interacting proteins with Brn1 in Curvularia lunata . Plant Pathology Journal, 31, 108–114. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Glazebrook, J. (2005) Contrasting mechanisms of defense against biotrophic and necrotrophic pathogens. Annual Review of Phytopathology, 43, 205–227. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- González‐Bosch, C. (2018) Priming plant resistance by activation of redox‐sensitive genes. Free Radical Biology & Medicine, 122, 171–180. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gouda, M.H.B. , Zhang, C.J. , Wang, J.H. , Peng, S.J. , Chen, Y.R. , Luo, H.B. et al. (2020) ROS and MAPK cascades in the post‐harvest senescence of horticultural products. Journal of Proteomics & Bioinformatics, 13, 1–7. [Google Scholar]

- Gupta, R. , Min, C.W. , Kim, Y.J. & Kim, S.T. (2019) Identification of Msp1‐induced signaling components in rice leaves by integrated proteomic and phosphoproteomic analysis. International Journal of Molecular Sciences, 20, 4135–4151. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gust, A.A. , Biswas, R. , Lenz, H.D. , Rauhut, T. , Ranf, S. , Kemmerling, B. et al. (2007) Bacteria‐derived peptidoglycans constitute pathogen‐associated molecular patterns triggering innate immunity in Arabidopsis . Journal of Biological Chemistry, 282, 32338–32348. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jonak, C. , Okresz, L. , Bogre, L. & Hirt, H. (2002) Complexity, cross talk and integration of plant MAP kinase signaling. Current Opinion in Plant Biology, 5, 415–424. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kadota, Y. , Shirasu, K. & Zipfel, C. (2015) Regulation of the NADPH oxidase RBOHD during plant immunity. Plant and Cell Physiology, 56, 1472–1480. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kishi‐Kaboshi, M. , Okada, K. , Kurimoto, L. , Murakami, S. , Umezawa, T. , Shibuya, N. et al. (2010) A rice fungal MAMP responsive MAPK cascade regulates metabolic flow to antimicrobial metabolite synthesis. The Plant Journal, 63, 599–612. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kohler, A. , Schwindling, S. & Conrath, U. (2002) Benzothiadiazole‐induced priming for potentiated responses to pathogen infection, wounding, and infiltration of water into leaves requires the NPR1/NIM1 gene in Arabidopsis . Plant Physiology, 128, 1046–1056. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kwon, J.H. & Lee, C.J. (2006) Rhizopus soft rot on pear (Pyrus serotina) caused by Rhizopus stolonifer in Korea. Mycobiology, 34, 151–153. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee, H.Y. & Back, K. (2016) Mitogen‐activated protein kinase pathways are required for melatonin‐mediated defense responses in plants. Journal of Pineal Research, 60, 327–335. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li, C. , Cao, S. , Wang, K. , Lei, C. , Ji, N. , Xu, F. et al. (2021) Heat shock protein HSP24 is involved in the BABA‐induced resistance to fungal pathogen in postharvest grapes underlying an NPR1‐dependent manner. Frontiers in Plant Science, 12, 646147. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li, C. , Wang, J. , Ji, N. , Lei, C. , Zhou, D. , Zheng, Y. et al. (2020a) PpHOS1, a RING E3 ubiquitin ligase, interacts with PpWRKY22 in the BABA‐induced priming defense of peach fruit against Rhizopus stolonifer . Postharvest Biology and Technology, 159, 111029–111037. [Google Scholar]

- Li, C.H. , Wang, K.T. & Zheng, Y.H. (2020b) Redox status regulates subcelluar localization of PpTGA1 associated with a BABA‐induced priming defence against Rhizopus rot in peach fruit. Molecular Biology Reports, 47, 6657–6668. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li, C.H. , Wang, K.T. , Lei, C.Y. & Zheng, Y.H. (2020c) Translocation of PpNPR1 is required for β‐aminobutyric acid‐triggered resistance against Rhizopus stolonifer in peach fruit. Scientia Horticulturae, 272, 1–10. [Google Scholar]

- Liang, S.‐M. , Chen, S.‐C. , Liu, Z.‐L. , Shan, W. , Chen, J.‐Y. , Lu, W.‐J. et al. (2020) MabZIP74 interacts with MaMAPK11‐3 to regulate the transcription of MaACO1/4 during banana fruit ripening. Postharvest Biology and Technology, 169, 111293–111302. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, Y. , Yan, J. , Qin, Q. , Zhang, J. , Chen, Y. , Zhao, L. et al. (2020) Type 1 protein phosphatases (TOPPs) contribute to the plant defense response in Arabidopsis. Journal of Integrative Plant Biology, 62, 360–377. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Livak, K.J. & Schmittgen, T.D. (2001) Analysis of relative gene expression data using real‐time quantitative PCR and the 2−ΔΔ C t method. Methods, 25, 402–408. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mackey, D. , Holt, B.F. III , Wiig, A. & Dangl, J.L. (2002) RIN4 interacts with Pseudomonas syringae type III effector molecules and is required for RPM1‐mediated resistance in Arabidopsis . Cell, 108, 743–754. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marino, D. , Dunand, C. , Puppo, A. & Pauly, N. (2012) A burst of plant NADPH oxidases. Trends in Plant Science, 17, 9–15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mateo, A. , Funck, D. , Mühlenbock, P. , Kular, B. , Mullineaux, P.M. & Karpinski, S. (2006) Controlled levels of salicylic acid are required for optimal photosynthesis and redox homeostasis. Journal of Experimental Botany, 57, 1795–1807. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meng, X. & Zhang, S. (2013) MAPK cascades in plant disease resistance signaling. Annual Review of Phytopathology, 51, 245–266. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miao, Y. , Laun, T.M. , Smykowski, A. & Zentgraf, U. (2007) Arabidopsis MEKK1 can take a short cut: it can directly interact with senescence‐related WRKY53 transcription factor on the protein level and can bind to its promoter. Plant Molecular Biology, 65, 63–76. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morales, J. , Kadota, Y. , Zipfel, C. , Molina, A. & Torres, M.A. (2016) The Arabidopsis NADPH oxidases RbohD and RbohF display differential expression patterns and contributions during plant immunity. Journal of Experimental Botany, 67, 1663–1676. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morré, D.J. & Morré, D.M. (2000) Applications of aqueous two‐phase partition to isolation of membranes from plants: a periodic NADH oxidase activity as a marker for right side‐out plasma membrane vesicles. Journal of Chromatography B: Biomedical Sciences and Applications, 743, 369–376. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murashige, T. & Skoog, F. (1962) A revised medium for rapid growth and bioassays with tobacco tissue cultures. Physiologia Plantarum, 15, 473–497. [Google Scholar]

- Mutalik, V.K. & Venkatesh, K.V. (2006) Effect of the MAPK cascade structure, nuclear translocation and regulation of transcription factors on gene expression. Biosystems, 85, 144–157. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pastor, V. , Luna, E. , Ton, J. , Cerezo, M. , García‐Agustín, P. & Flors, V. (2013) Fine tuning of reactive oxygen species homeostasis regulates primed immune responses in Arabidopsis . Molecular Plant‐Microbe Interactions, 26, 1334–1344. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Patterson, B.D. , MacRae, E.A. & Ferguson, I.B. (1984) Estimation of hydrogen peroxide in plant extracts using titanium. Analytical Biochemistry, 139, 487–492. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pieterse, C.M.J. , Van Pelt, J.A. , Ton, J. , Parchmann, S. , Mueller, M.J. , Buchala, A.J. et al. (2000) Rhizobacteria‐mediated induced systemic resistance (ISR) in Arabidopsis requires sensitivity to jasmonate and ethylene but is not accompanied by an increase in their production. Physiological and Molecular Plant Pathology, 57, 123–134. [Google Scholar]

- Pozo, M.J. , van der Ent, S. , van Loon, L.C. & Pieterse, C.M. (2008) Transcription factor MYC2 is involved in priming for enhanced defense during rhizobacteria‐induced systemic resistance in Arabidopsis thaliana . New Phytologist, 180, 511–523. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sagi, M. & Fluhr, R. (2001) Superoxide production by plant homologues of the gp91(phox) NADPH oxidase. Modulation of activity by calcium and by tobacco mosaic virus infection. Plant Physiology, 126, 1281–1290. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shan, W. , Chen, J.Y. , Kuang, J.F. & Lu, W.J. (2016) Banana fruit NAC transcription factor MaNAC5 cooperates with MaWRKYs to enhance the expression of pathogenesis‐related genes against Colletotrichum musae . Molecular Plant Pathology, 17, 330–338. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sharma, P.C. , Ito, A. , Shimizu, T. , Terauchi, R. , Kamoun, S. & Saitoh, H. (2003) Virus‐induced silencing of WIPK and SIPK genes reduces resistance to a bacterial pathogen, but has no effect on the INF1‐induced hypersensitive response (HR) in Nicotiana benthamiana . Molecular Genetics and Genomics, 269, 583–591. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sugiura, R. , Toda, T. , Dhut, S. , Shuntoh, H. , Kuno, T. & Kuno, T. (1999) The MAPK kinase Pek1 acts as a phosphorylation‐dependent molecular switch. Nature, 399, 479–483. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tada, Y. , Spoel, S.H. , Pajerowska‐Mukhtar, K. , Mou, Z. , Song, J. , Wang, C. et al. (2008) Plant immunity requires conformational charges of NPR1 via S‐nitrosylation and thioredoxins. Science, 321, 952–956. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ton, J. , van Pelt, J.A. , van Loon, L.C. & Pieterse, C.M.J. (2002) Differential effectiveness of salicylate‐dependent and jasmonate/ethylene‐dependent induced resistance in Arabidopsis . Molecular Plant‐Microbe Interactions, 15, 27–34. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tong, Z.G. , Gao, Z.H. , Wang, F. , Zhou, J. & Zhang, Z. (2009) Selection of reliable reference genes for gene expression studies in peach using real‐time PCR. BMC Molecular Biology, 10, 71. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tsuda, K. , Mine, A. , Bethke, G. , Igarashi, D. , Botanga, C.J. , Tsuda, Y. et al. (2013) Dual regulation of gene expression mediated by extended MAPK activation and salicylic acid contributes to robust innate immunity in Arabidopsis thaliana . PLoS Genetics, 9, e1004015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vallad, G.E. & Goodman, R.M. (2004) Systemic acquired resistance and induced systemic resistance in conventional agriculture. Crop Science, 44, 1920–1934. [Google Scholar]

- Verhagen, B.W.M. , Glazebrook, J. , Zhu, T. , Chang, H.S. , van Loon, L.C. & Pieterse, C.M.J. (2004) The transcriptome of rhizobacteria‐induced systemic resistance in Arabidopsis. Molecular Plant‐Microbe Interactions, 17, 895–908. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang, K.T. , Li, C.H. , Lei, C.Y. , Zou, Y.Y. , Li, Y.J. & Zheng, Y.H. (2021) Dual function of VvWRKY18 transcription factor in the β‐aminobutyric acid‐activated priming defense in grapes. Physiologia Plantarum, 172, 1477–1492. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang, K.T. , Liao, Y.X. , Xiong, Q. , Kan, J.Q. , Cao, S.F. & Zheng, Y.H. (2016) Induction of direct or priming resistance against Botrytis cinerea in strawberries by β‐aminobutyric acid and their effects on sucrose metabolism. Journal of Agricultural and Food Chemistry, 4, 5855–5865. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang, K. , Wu, D. , Bo, Z. , Chen, S.I. , Wang, Z. , Zheng, Y. et al. (2019) Regulation of redox status contributes to priming defense against Botrytis cinerea in grape berries treated with β‐aminobutyric acid. Scientia Horticulturae, 244, 352–364. [Google Scholar]

- Wu, C. , Shan, W. , Liang, S. , Zhu, L. , Guo, Y. , Chen, J. et al. (2019) MaMPK2 enhances MabZIP93‐mediated transcriptional activation of cell wall modifying genes during banana fruit ripening. Plant Molecular Biology, 101, 113–127. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xiao, S. & Chye, M.L. (2011) Overexpression of Arabidopsis ACBP3 enhances NPR1‐dependent plant resistance to Pseudomonas syringe pv. tomato DC3000. Plant Physiology, 156, 2069–2081. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yao, Y. , He, R.J. , Xie, Q.L. , Zhao, X.H. , Deng, X.M. , He, J.B. et al. (2017) ETHYLENE RESPONSE FACTOR 74 (ERF74) plays an essential role in controlling a respiratory burst oxidase homolog D (RbohD)‐dependent mechanism in response to different stresses in Arabidopsis . New Phytologist, 213, 1667–1681. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, H. , Li, D. , Wang, M. , Liu, J. , Teng, W. , Cheng, B. et al. (2012) The Nicotiana benthamiana mitogen‐activated protein kinase cascade and WRKY transcription factor participate in Nep1 (Mo)‐triggered plant responses. Molecular Plant‐Microbe Interactions, 25, 1639–1653. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, Y. , Fan, W. , Kinkema, M. , Li, X. & Dong, X. (1999). Interaction of NPR1 with basic leucine zipper protein transcription factors that bind sequences required for salicylic acid induction of the PR‐1 gene. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences USA, 96, 6523–6528. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, Y.Y. , Zhu, H.Y. , Zhang, Q. , Li, M.Y. , Yan, M. , Wang, R. et al. (2009) Phospholipase Dα1 and phosphatidic acid regulate NADPH oxidase activity and production of reactive oxygen species in ABA‐mediated stomatal closure in Arabidopsis . The Plant Cell, 21, 2357–2377. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhou, J. , Xia, X.J. , Zhou, Y.H. , Shi, K. , Chen, Z. & Yu, J.Q. (2014) RBOH1‐dependent H2O2 production and subsequent activation of MPK1/2 play an important role in acclimation‐induced cross‐tolerance in tomato. Journal of Experimental Botany, 65, 595–607. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zimmerli, L. , Métraux, J.P. & Mauch‐Mani, B. (2001) β‐aminobutyric acid‐induced protection of Arabidopsis against the necrotrophic fungus Botrytis cinerea . Plant Physiology, 126, 517–523. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zipfel, C. & Robatzek, S. (2010) Pathogen‐associated molecular pattern‐triggered immunity: veni, vidi…? Plant Physiology, 154, 551–554. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

FIGURE S1 Yeast two‐hybrid screening of the PpTGA1 protein. (a) The expression abundance of PpTGA1 potentiated under treatment of peaches with BABA following R. stolonifer inoculation within 72 hr postinoculation. (b) Self‐activation detection of the bait plasmid pGBKT7‐PpTGA1 and the truncated plasmid pGBKT7‐PpTGA1‐1/pGBKT7‐PpTGA1‐2 on synthetic dropout plates (SD/−Trp/−His and SD/−Trp/−His/−Ade) with or without X‐α‐gal and 3‐AT. Given the strong self‐activation of the recombinant pGBKT7‐PpTGA1 and the DNA‐binding domains observed in PpTGA1, we developed two truncation schemes for PpTGA1. Although the truncated plasmid pGBKT7‐PpTGA1‐1 similarly presented self‐activation, the self‐activation activity of pGBKT7‐PpTGA1‐2 was inhibited by the addition of 10 mM 3‐AT and completely repressed by 20 mM 3‐AT. (c) Yeast containing the bait plasmid (pGBKT7‐PpTGA1‐2) and prey library were screened on TDO supplied with 10 or 20 mM 3‐AT. (d) Verification of the positive interacting proteins of PpTGA1 on synthetic dropout plates

FIGURE S2 Motif scan graphical analysis of PpTGA1 was conducted using SCANSITE 4.0 (https://scansite4.mit.edu)

FIGURE S3 Phylogenetic and sequence alignment of PpMAPKK5 with AtMAPKKs, SlMAPKKs, NtMAPKKs, and OsMAPKKs. (a) Four groups of MAPKKs are shown in the phylogenetic tree. PpMAPKK5 is highlighted in red and classified into group C. The protein sequences of 10 MAPKKs from Arabidopsis thaliana, seven from Solanum lycopersicum, six from Nicotiana tabacum, seven from Oryza sativa, and PpMAPKK5 were aligned using ClustalW, and the phylogenetic tree was generated with MEGA 5.0 (neighbour‐joining method; 1,000 bootstraps) and visualized using iTOL. (b) Sequence alignment among these group C MAPKKs was conducted using DNAMAN v. 6.0, and the identical amino acids are shaded in dark blue

FIGURE S4 Phylogenetic analysis of PpRBOHs and AtRBOHD/AtRBOHF, in which PpRBOHD and PpRBOHA showed similar clustering with AtRBOHD and AtRBOHF, respectively

FIGURE S5 Identification of the inserted dscDNA size of the reading frame. Twenty‐four clones were randomly selected from LB plates and amplified by colony PCR. The PCR product was analysed by 1.2% agarose gel electrophoresis to determine the recombination frequency and fragment size. Lanes 1–24, inserted dscDNA; M, DNA ladder (DL500; Vazyme)

FIGURE S6 Schematic diagram of the CRISPR‐AtMAPKK5 vector

FIGURE S7 Agarose gel electrophoresis of total RNA and dscDNA and the plating assay of the constructed cDNA library. M, DNA ladder (DL500; Vazyme). (a) Agarose gel electrophoresis (AGE) presented three discrete ribosomal RNA bands (28/18S and 5S) with little nonspecific degradation, which verified the integrity and quality of the total RNA isolated from Prunus persica. (b) The dscDNA fragments ranged in size from 0.1 to 2.0 kb on a 1.2% agarose gel. (c) The plating assay of the constructed cDNA library performed in 10‐fold serial dilutions from 10−1 to 10−4 reflected that the optimal dilution factor was 100 times. Based on the colony number on 100 µg/ml ampicillin selection plates, the cDNA library titre was calculated as 5.08 × 106 cfu/ml, and the quantity of this Y2H library was approximately 1.25 × 107 cfu

FIGURE S8 PpTGA1 contains a BRLZ domain (basic‐leucine zipper domain, possessing DNA‐binding transcription factor activity) and a DOG1 domain (transcription factor TGA‐like domain, possessing sequence‐specific DNA‐binding activity), which was analysed with SMART (http://smart.embl‐heidelberg.de)

FIGURE S9 His‐ and GST‐tagged proteins were detected by gel image analysis

TABLE S1 The motif sites of PpTGA1 predicted by SCANSITE 4.0

TABLE S2 Sequences of the primers used in the study

DATA S1 Three tandem copies of the AS‐1 element (TGACG) are present in the promoter regions of PpPR1, PpPR2, and PpPR5, and the AS‐1 elements are indicated in the black box in red. Restriction sites are underlined

DATA S2 Truncation scheme of PpTGA1 for further yeast two‐hybrid screening

DATA S3 The promoter regions of PpPR1, PpPR2, and PpPR5. The AS‐1 element (TGACG) is marked in red and boxed, and the translation start sites are underlined with a yellow box

Data Availability Statement

The data that supports the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.