Abstract

Background

Right ventricular (RV) dysfunction in sepsis and septic shock has been infrequently studied and has uncertain prognostic significance.

Research Question

Does RV function impact mortality in sepsis and septic shock?

Study Design and Methods

We reviewed the published literature from January 1999 to April 2020 for studies evaluating adult patients with sepsis and septic shock. Study definition of RV dysfunction was used to classify patients. The primary outcome was all-cause mortality divided into short-term mortality (ICU stay, hospital stay, or mortality ≤30 days) and long-term mortality (>30 days). Effect estimates from the individual studies were extracted and combined, using the random-effects, generic inverse variance method of DerSimonian and Laird.

Results

Ten studies, 1,373 patients, were included; RV dysfunction was noted in 477 (34.7%). RV dysfunction was variably classified as decreased RV systolic motion, high RV/left ventricular ratio and decreased RV ejection fraction. Septic shock, ARDS, and mechanical ventilation were noted in 82.0%, 27.5%, and 78.4% of the population, respectively. Patients with RV dysfunction had lower rates of mechanical ventilation (71.9% vs 81.9%; P < .001), higher rates of acute hemodialysis (38.1% vs 22.4%; P = .04), but comparable rates of septic shock and ARDS. Studies showed moderate (I2 = 58%) and low (I2 = 49%) heterogeneity for short-term and long-term mortality, respectively. RV dysfunction was associated with higher short-term (pooled OR, 2.42; 95%CI, 1.52-3.85; P = .0002) (10 studies) and long-term (pooled OR, 2.26; 95%CI, 1.29-3.95; P = .004) (4 studies) mortality.

Interpretation

In this meta-analysis of observational studies, RV dysfunction was associated with higher short-term and long-term mortality in sepsis and septic shock.

Key Words: critical care echocardiography, right ventricular dysfunction, sepsis, septic cardiomyopathy, septic shock

Abbreviations: ASE, American Society of Echocardiography; LV, left ventricular; RV, right ventricular

Sepsis, defined as a life-threatening organ dysfunction caused by a dysregulated host response to infection, is associated with high morbidity and mortality in contemporary ICUs in the United States and worldwide.1 Although we have seen a decrease in mortality from sepsis and septic shock in recent times, the in-hospital mortality remains as high as 20% to 30%.2,3 Sepsis is a multisystem disease process associated with renal, neurological, immunological, hepatic, and respiratory dysfunction and failure.4 In recent times, there has been an increasing emphasis on the cardiovascular outcomes of sepsis and septic shock.5,6 Cardiovascular dysfunction in sepsis may manifest as refractory vasodilatory shock, myocardial injury, atrial arrhythmias, and septic cardiomyopathy.7, 8, 9, 10 Left ventricular (LV) systolic and diastolic dysfunction have been extensively studied previously in patients with sepsis and septic shock.11, 12, 13, 14, 15, 16

However, limited data are available on right ventricular (RV) dysfunction in patients with sepsis and septic shock.12,15,17,18 RV dysfunction in sepsis is multifactorial and can be due to direct myocardial depression or increase in RV afterload due to hypoxemia, hypercapnia, and from application of mechanical ventilation in acute respiratory failure.19 Prior data from our center and others have demonstrated varying magnitudes of the association of RV failure with short- and long-term outcomes in sepsis and septic shock.17,20,21 Furthermore, the definitions of RV dysfunction in this population have employed varying criteria, using transthoracic echocardiography, transesophageal echocardiography and pulmonary artery catheterization.14,22 In light of these results, we sought to systematically review the available evidence regarding the impact of RV dysfunction on short- and long-term mortality in patients with sepsis and septic shock. We also sought to describe the acuity and presentation of these patients in contemporary sepsis literature. Our primary hypothesis was that RV dysfunction would be associated with higher mortality in sepsis.

Materials and Methods

Data Sources and Search Strategies

A comprehensive search of several databases from January 1, 1999 to April 2, 2020 was conducted. The databases included Ovid MEDLINE(R) and Epub Ahead of Print, In-Process & Other Non-Indexed Citations, and Daily, Ovid EMBASE, Ovid Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials, Ovid Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews, and Scopus. The search strategy was designed and conducted by an experienced librarian with input from the study's principal investigator (S. V.). Controlled vocabulary supplemented with key words was used to search for studies of RV dysfunction in adult patients with sepsis. The detailed strategy listing all search terms used and how they are combined is shown in e–Table 1. The resultant abstracts were screened by two independent reviewers (A. S., R. K. V.). All references of included studies were evaluated for additional studies. Study inclusion was based on the consensus of the two reviewers. A third independent reviewer (S. V.) served as the referee in case of disagreement between the first two reviewers. The search strategy and reporting were performed using STROBE guidelines.23 This review has been submitted to PROSPERO and is currently under review.

Inclusion and Exclusion Criteria

Studies in adult (≥18 years) patients with sepsis and septic shock as defined by Sepsis-1, Sepsis-2 or Sepsis-3 criteria were included.24, 25, 26 Patients with concomitant ARDS were included; however, those receiving extracorporeal membrane oxygenation support for cardiac or respiratory reasons were excluded because this technology provides ventricular support and may mitigate the effects of RV dysfunction. Studies evaluating RV function using either transthoracic or transesophageal echocardiography and pulmonary artery catheterization were included.17 The primary outcome was all-cause mortality divided into short-term mortality (ICU stay, hospital stay, or mortality ≤ 30 days) and long-term mortality (1-12 months). Literature from human studies and of case-control, cohort, case series, and randomized trial study designs were included. In studies reporting outcomes in unselected critically ill or shock patients, only studies for which a 2×2 table could be constructed between RV function and mortality were included. Abstracts presented at professional societal meetings were excluded because they are subject to a higher risk of bias because of a lack of rigorous peer review. Studies designed as case reports, systematic or narrative reviews, pediatric or animal studies, and studies without relevant outcomes were excluded. If multiple studies were published by the same group of authors over the same study duration, the most comprehensive study with relevant outcomes was included. Data abstracted included study year, population, location, type of study, baseline characteristics, ICU-related characteristics, illness severity, echocardiographic data, and clinical outcomes.

Statistical Analysis

The baseline characteristics of the patient cohorts, including rates of septic shock, ARDS, and mechanical ventilation, were compared using χ2 tests. Heterogeneity among the studies was estimated using the I2 statistic as described by Higgins et al.27 I2 values of <50%, 50%-75%, and >75% are deemed to have low, moderate, and high heterogeneity, respectively. The pooled ORs and 95%CIs were calculated using a generic inverse method of DerSimonian and Laird.28 Given the possibility of between-study variance, we used a random-effect model rather than a fixed-effect model. Publication bias was estimated by visual inspection of funnel plots for asymmetry and the Egger test.29 Study results were considered statistically significant when the CI range did not include unity, and P < .05. Statistical analysis was performed using Comprehensive Meta-analysis version 3 software (Biostat Inc) and Review Manager (RevMan) 5.4.1 software from the Cochrane Collaboration.

Results

The search strategy identified 267 titles, of which 10 studies, representing 1,373 patients, met the inclusion criteria (Fig 1, Table 1).6,17,18,20,21,30, 31, 32, 33, 34 All studies except the study by Geri et al21 were single center in nature, and all studies except those by Furian et al30 and Tongyoo et al34 were from the United States or Europe. Six studies20,21,30, 31, 32, 33 were prospectively designed, and four studies6,17,18,34 were retrospective in nature. The quality of the studies was assessed using the New-Castle Ottawa Scale (e-Table 2). All except one study31 were published between 2011 and 2019. Variable echocardiographic and pulmonary artery catheterization-derived criteria were used to define RV dysfunction, which could be broadly classified as decreased RV systolic motion (tissue Doppler or M-mode), RV/LV ratio (end-diastolic diameter, end-diastolic area, visual estimate), and decreased RV ejection fraction (<40%, <20%) (Table 1). Most studies excluded patients with acute LV failure, active or recent acute coronary syndrome, malignancy, pregnancy, and cardiomyopathy. All studies assessed short-term mortality, and four studies assessed long-term mortality. The average age of the overall cohort varied between 51 and 65 years, and approximately 33% to 75% were males, in the studies that reported this information (Table 2). Respiratory sepsis remained the predominant source, whereas abdominal and other sources occurred less frequently (Table 2). Comorbidities were inconsistently reported across studies. History of coronary artery disease, chronic heart failure, and COPD were seen in 14.3% (102/712), 5.3% (27/506), and 20.0% (170/852), respectively.

Figure 1.

Literature search strategy using Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) flow diagram.

Table 1.

Study Characteristics

| Author/Year | Country | Inclusion Criteria | Exclusion Criteria | Timing of HD Measurement | RVD Criteria | Mortality |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cirulis et al,18 2018 | United States | Severe sepsis/septic shock with TTE < 48 h | VAD | 48 h | RV/LV EDD > 0.9 | 30 d |

| Furian et al,30 2012 | Brazil | Severe sepsis or septic shock | Age > 80 y, HF, liver failure, BM failure, IE, immunosuppression/deficiency, cancer | 24 h | RV-S’ < 12 cm/s | In-hospital |

| Geri et al,21 2019 | France | Post-hoc analysis of Hemosepsis and HemoPred with CCE in resuscitation | Prior HF | 12 h | RV/LV EDA > 0.8 | 7 d |

| Mokart et al,31 2007 | France | Septic shock | HF, VHD, COPD, CKD, CNS disorders | Q1d | RVEDD > 30 mm + septal dyskinesia (PSAX/PLAX), RV > LV visual (A4C/SC) + PASP > 45 mm Hg | ICU |

| Orde et al,32 2014 | United States | Severe sepsis or septic shock | SVT, pregnancy, ACHD, VHD, poor TTE images, CMP, prosthetic valve | 24 h | ASE criteriaa | 30 d 6 mo |

| Papanikolaou et al,33 2014 | Greece | Severe sepsis and septic shock with IMV and PAC (both ≥ 3 d) | Pregnancy, CAD, HF, VHD, inotropes, CMP, CKD, PH, meningitis, cerebral abscess, ICH, poor TTE images | 1-3 d | RVEF < 40% | 28 d |

| Pulido et al,20 2012 | United States | Severe sepsis and septic shock with TTE < 24 h | Pregnancy, ACHD, VHD, prosthetic valve, CAD without TTE < 6 m | 24 h | RV S’ < 15 cm/s, RV/LV size, WMA, expert opinion | 30 d 1 y |

| Tongyoo et al,34 2011 | Thailand | Septic shock with HD instability and PAC placement | … | 24 h | RAP > 12 mm Hg, mean PAP > 30 mm Hg, PVR > 250 dyn-s/cm5, PCWP < 18 mm Hg | In-hospital |

| Vallabhajosyula,17 2017 | United States | Severe sepsis and septic shock with TTE < 72 h | HF, cor pulmonale, PH, VHD, ACHD, PFO, CMP, recent ACS | 72 h | ASE criteriaa | In-hospital, 1 y |

| Winkelhorst et al,6 2020 | Netherlands | Severe sepsis and septic shock with PAC < 24 h | Pregnancy, ACHD, metastatic cancer, ACS < 1 wk, severe sepsis duration > 24 h, malfunctioning PAC | 24 h | RVEF < 20% | ICU 1 y |

A4C = apical 4-chamber view; ACHD = adult congenital heart disease; ACS = acute coronary syndrome; ASE = American Society of Echocardiography; BM = bone marrow; CAD = coronary artery disease; CCE = critical care echocardiography; CKD = chronic kidney disease; CMP = cardiomyopathy; EDA = end-diastolic area; EDD = end-diastolic diameter; EF = ejection fraction; HD = hemodynamic; HF = heart failure; ICH = intracranial hemorrhage; IE = infective endocarditis; IMV = invasive mechanical ventilation; LV = left ventricular; PAC = pulmonary artery catheterization; PAP = pulmonary artery pressure; PCWP = pulmonary capillary wedge pressure; PASP = pulmonary artery systolic pressure; PFO = patent foramen ovale; PH = pulmonary hypertension; PLAX = parasternal long-axis view; PSAX = parasternal short-axis view; PVR = pulmonary vascular resistance; RAP = right atrial pressure; RV = right ventricular; RVD = right ventricular dysfunction; RVEDD = right ventricular end-diastolic diameter; RVEF = right ventricular ejection fraction; SC = sub-costal view; SVT = supraventricular tachycardia; TTE = transthoracic echocardiogram; VAD = ventricular assist device; VHD = valvular heart disease; WMA = wall motion abnormalities.

ASE criteria for the diagnosis of RV dysfunction: semiquantitative size and function, TAPSE < 16 mm, RV S’ < 0.15 cm/s and RV FAC < 35%.

Table 2.

Baseline Characteristics of Patients

| Author/Year | Patients, No. |

Age (y), Mean (SD) or Median (IQR) |

Male Sex, No. (%) |

Source of Sepsis Respiratory, No. (%) Abdominal, No. (%) Other, No. (%) |

Septic Shock, No. (%) |

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total | RVD | No RVD | Total | RVD | No RVD | Total | RVD | No RVD | |||

| Cirulis et al,18 2018 | 146 | 81 | 65 | … | 67 (45.8) | 77 (52.7) … 36 (24.6) |

42 (51.9) … 19 (23.5) |

35 (53.9) … 17 (26.2) |

72 (49.3) | 42 (51.9) | 30 (46.2) |

| Furian et al,30 2012 | 45 | 14 | 31 | 51 (18) | 15 (33.3) | 11 (24.4) 15 (33.3) … |

... ... ... |

... ... ... |

32 (71.1) | ... | ... |

| Geri et al,21 2019 | 360 | 81 | 279 | 64 (55-74) | 233 (64.7) | 169 (46.9) 109 (30.3) 33 (9.2) |

48 (59.3) 13 (16.1) 14 (17.3) |

121 (43.4) 96 (34.4) 19 (6.8) |

360 (100) | 81 (100) | 279 (100) |

| Mokart et al, 31 2007 | 45 | 17 | 28 | 56 (50-68) | 32 (71.1) | 28 (62.2) 8 (17.7) 14 (31.1) |

... ... ... |

... ... ... |

45 (100) | ... | ... |

| Orde et al, 32 2014 | 60 | 43 | 17 | 62 (15) | 30 (50) | ... | ... | ... | 60 (100) | ... | ... |

| Papanikolaou et al, 33 2014 | 42 | 33 | 9 | ... | 26 (61.9) | 16 (38.1) 5 (11.9) 3 (7.1) |

... ... ... |

... ... ... |

30 (71.4) | ... | ... |

| Pulido et al, 20 2012 | 71 | 33 | 38 | 65 (15) | 53 (74.7) | ... | ... | ... | 64 (90.1) | 30 (90.9) | 34 (89.5) |

| Tongyoo et al, 34 2011 | 118 | 21 | 97 | 58 (18.5) | 70 (59.3) | ... | ... | ... | 85 (72.0) | 15 (71.4) | 70 (72.2) |

| Vallabhajosyula,17 2017 | 388 | 214 | 174 | ... | 198 (51) | 81 (20.9) 13 (3.3) 126 (32.5) |

54 (25.2) 5 (2.3) 83 (38.7) |

27 (15.5) 8 (4.6) 43 (24.7) |

281 (72.4) | 162 (75.7) | 119 (68.4) |

| Winkelhorst et al, 6 2019 | 98 | 21 | 77 | ... | 50 (51) | 46 (46.9) 22 (22.5) 6 (6.1) |

11 (52.4) 4 (19.1) 1 (4.8) |

35 (45.5) 18 (23.3) 5 (15.6) |

87 (88.8) | 21 (100) | 66 (85.7) |

IQR = interquartile range; RVD = right ventricular dysfunction.

RV dysfunction was present in 477 (34.7%) of the included patients (Tables 2, 3, e-Table 3). Septic shock was seen in 82.0% (1,126/1,373) of the overall population, with comparable rates in patients with (351/451 [77.8%]) or without RV dysfunction (598/730 [81.9%]); P = .10. Five studies reported the prevalence of concomitant ARDS at 211/768 (27.5%) in the overall population, with comparable rates between the cohorts with (99/349 [28.4%]) or without RV dysfunction (98/374 [26.2%]); P = .56 (Table 3). Mechanical ventilation was used in 78.4% (1,076/1,373) of the overall cohort, with significantly lower rates in the RV dysfunction group (71.9% [348/484] vs 81.9% [605/739]; P < .001) (Table 3). Use of hemodialysis for concomitant acute kidney injury was reported in three studies—overall cohort, 30.3% (79/261), with higher rates in the RV dysfunction cohort (38.1% vs 22.4%; P = .04).

Table 3.

Cardiopulmonary Characteristics of Patients

| Author/Year | ARDS, No. (%) |

Mechanical Ventilation, No. (%) |

Lowest Pao2/Fio2 ratio Mean (SD) or Median (IQR) |

LVEF (%) Mean (SD) or Median (IQR) |

||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total | RVD | No RVD | Total | RVD | No RVD | Total | RVD | No RVD | Total | RVD | No RVD | |

| Cirulis et al,18 2018 | 44 (30.1) | 23 (28.4) | 21 (32.3) | 94 (64.4) | 45 (55.6) | 49 (75.4) | ... | ... | ... | ... | 58 (16) | 58 (13.5) |

| Furian et al,30 2012 | 9 (20) | ... | ... | 39 (86.7) | ... | ... | ... | ... | ... | 57 (13) | ... | ... |

| Geri et al,21 2019 | ... | ... | ... | 360 (100) | 81 (100) | 279 (100) | 184 (113-262) | 153 (105-231) | ... | 54 (40-64) | 57 (46-64) | ... |

| Mokart et al,31 2007 | ... | ... | ... | 45 (100) | ... | ... | ... | ... | ... | ... | ... | |

| Orde et al,32 2014 | ... | ... | ... | 39 (65) | ... | ... | 195 (128-290) | ... | ... | 57 (16) | ... | ... |

| Papanikolaou et al, 33 2014 | ... | ... | ... | 42 (100) | 33 (100) | 9 (100) | ... | ... | ... | ... | ... | ... |

| Pulido et al,20 2012 | 12 (16.9) | 6 (18.2) | 6 (15.8) | 55 (77.5) | 27 (81.8) | 28 (73.7) | ... | 178 (106-267) | 208 | ... | ... | ... |

| Tongyoo et al,35 2011 | 26 (22.0) | 4 (19.1) | 22 (22.7) | 104 (88.1) | 17 (81) | 87 (89.7) | ... | 172.8 (95.1) | 263 (174.9) | ... | ... | ... |

| Vallabhajosyula,17 2017 | 115 (29.6) | 66 (30.8) | 49 (28.2) | 213 (54.9) | 125 (58.4) | 88 (50.6) | ... | 197 (111-288) | ... | ... | 60 (55-65) | |

| Winkelhorst et al,6 2020 | ... | ... | ... | 85 (86.7) | 20 (95.2) | 65 (84.4) | ... | ... | ... | ... | ... | ... |

IQR = interquartile range; LVEF = left ventricular ejection fraction; RVD = right ventricular dysfunction.

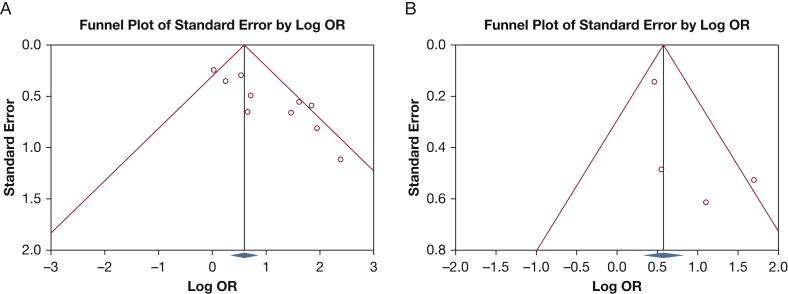

In the pooled analysis, although the funnel plot was suggestive of a publication bias in favor of positive studies regarding short-term mortality (P < .001), no significant publication bias was found in meta-analyses evaluating long-term mortality (P = .22) (Fig 2). Studies evaluating short-term and long-term mortality had moderate (I2 = 58%) and low (I2 = 49%) heterogeneity, respectively. In the pooled meta-analysis of 10 studies, RV dysfunction was associated with higher short-term mortality (OR, 2.42; 95%CI, 1.52-3.85; P = .0002) (Fig 3). In the pooled meta-analysis of four studies evaluating long-term mortality, RV dysfunction was associated with higher long-term mortality (OR, 2.26; 95% CI, 1.29-3.95; P = .004) (Fig 3). Individually removing and re-adding large studies, such as Cirulis et al,18 Geri et al,21 Pulido et al,20 and Vallabhajosyula et al,17 and studies that were outliers on the funnel plot did not influence the overall risk ratios.

Figure 2.

Duval and Tweedie Trim and Fill Method funnel plot analysis of publication bias. A, Short-term mortality; B, long-term mortality.

Figure 3.

A, Short-term and B, long-term mortality in sepsis and septic shock with and without right ventricular dysfunction.

Discussion

In this large meta-analysis of 1,373 patients with sepsis and septic shock, RV dysfunction was noted in nearly 35% of the population. Patients with and without RV dysfunction had comparable rates of septic shock and ARDS, but lower rates of invasive mechanical ventilation. RV dysfunction was associated with more than twice the risk of short-term and long-term mortality in sepsis and septic shock.

Measuring and Defining RV Function in Sepsis

Dysfunction of the RV and pulmonary circulation have been poorly evaluated, understood, and managed in patients with sepsis, ARDS, and other critical illnesses.8,17,19,35 This is partially because of the lack of well-defined criteria to distinguish normal from abnormal function for the right-sided circulation. As noted in this study, varying cutoffs of invasive and noninvasive hemodynamic parameters were used to evaluate RV function. This may be attributable to the practical challenges of imaging in critically ill patients.14,16,22,36 Although the American Society of Echocardiography (ASE) has developed strongly validated cutoffs for ventricular dysfunction, prior data have shown that they have limited applicability in patients with septic shock.37,38 Possibly the ASE criteria for RV dysfunction,39 although well established, may need to be validated further in critically ill patients. Prior work from our group has shown that semiquantitative size and function remain the chief parameter for quantifying RV function in sepsis and septic shock, and importantly, use of these visually estimated parameters did not influence the correlation of RV function with in-hospital mortality.17 Furthermore, sepsis and septic shock, and the therapies used to treat these conditions, are primarily vascular pathology, and therefore, the RV parameters have to be contextualized to the loading conditions.2,7,35,40,41 Incorporation of vasoactive medication dosing, mechanical ventilation parameters, and presence of concomitant ARDS are important considerations in evaluating RV function in sepsis.8,19,42

RV Dysfunction and Mortality

This study demonstrates that RV function has a strong correlation with both short- and long-term mortality, in comparison with the lack of association noted in prior smaller studies.21 These differences may be partially explained by the heterogeneity of the included population, timing of echocardiography, and variation in ventilator parameters in this population.12,14,22 Although the RV failure in this population may represent a preload- or afterload-induced failure secondary to fluid loading and ARDS, prior studies have demonstrated an independent impact of RV failure on in-hospital mortality.8,17,21,43 Pulido et al20 demonstrated similar mechanical ventilation, positive end-expiratory pressure, hypoxemia, acidosis, and vasoactive medications rates between patients with and without normal RV function in sepsis and septic shock. As demonstrated by Geri et al,21 possibly RV dysfunction may represent a distinct clinical phenotype that behaves dissimilarly to those with predominant LV dysfunction in sepsis. Landesberg et al11,12 have demonstrated a strong correlation of LV diastolic dysfunction with RV function, which may explain the prognostic effect of cardiac biomarkers in this population. Prior studies have demonstrated the prognostic utility of cardiac biomarkers in sepsis and septic shock,10,44,45 and these natriuretic peptides correlate closely with RV function in patients with pulmonary hypertension, which may allude to their role in sepsis. Furthermore, RV failure may be associated with venacaval congestion and false-positive pulse pressure variability, which may influence fluid loading in septic patients and therefore influence outcomes in this population.8,18,21,46 Finally, patients with RV dysfunction are noted to have lower cardiac output and greater requirements for vasoactive medications, all of which might contribute to higher rates of acute kidney injury.2,3,17,35,40,41 These data are consistent with prior work from our group in an all-comer population, in which presence of RV dysfunction was noted to portend poor short- and long-term prognosis.47 Although limited in number, our meta-analysis demonstrated the cohort with RV dysfunction to have higher rates of dialysis use for acute kidney injury, suggesting a cardiorenal vs a prerenal cause in this population.35 Finally, our study notes lower mechanical ventilation use in the cohort with RV dysfunction. The surprising lower rates in mechanical ventilation rates and comparable ARDS rates in the RV dysfunction cohort suggest potential heterogeneity of inclusion, and we need careful assessment and standardization in future studies.

Limitations

This study has important limitations. The selection of patients with varying definitions and severity of sepsis and septic shock can cause significant heterogeneity in the assessment of clinical outcomes. RV dysfunction criteria differed among studies reviewed, including modalities used. Possibly RV dysfunction as defined by echocardiography might represent early compensation, whereas decreased flow/cardiac output as measured by pulmonary artery catheterization may represent an advanced stage of RV failure.48 Prospective RV function evaluation including strain imaging will be more informative in this population with sepsis or septic shock; however, this will remain technically challenging in the ICU. The mechanisms of RV dysfunction are heterogeneous and can be due to increases in preload and afterload or direct myocardial toxicity in sepsis, and therefore, further study of the causal mechanisms are needed in this population. Our study consisted primarily of observational studies that carry their individual limitations. This meta-analysis was a summative meta-analysis of published literature, and therefore detailed baseline data, specifically an evaluation of timing of RV dysfunction, timing of echocardiography, and mechanical ventilation settings were not uniformly reported across studies. Chronic lung disease, which is a known confounder of RV function, was noted in nearly 20% of the population. Future studies should evaluate acute and chronic RV dysfunction separately in an attempt to better understand the RV hemodynamics during sepsis.8,17,48 Finally, only four of the 10 studies evaluated long-term survival.

Interpretation

In this meta-analysis of 1,373 patients with sepsis and septic shock, the presence of RV dysfunction was associated with higher short-term and long-term mortality. Given the heterogeneity of timing of RV assessment, definition of sepsis, variable inclusion/exclusion criteria, carefully designed prospective trials evaluating the physiology, hemodynamics, and outcomes of this critically ill population are warranted to prevent and improve the management of RV failure.

Take-home Point.

RV dysfunction in sepsis and septic shock is associated with higher short-term and long-term mortality. Further mechanistic and preventative studies are needed to improve clinical outcomes in this critically ill population.

Acknowledgments

Author contributions: Study design, literature review, data analysis, statistical analysis: S. V., A. S., R. V., W. C., P. R. S.; Data management, data analysis, drafting manuscript: S. V., A. S., R. V., W. C., P. R. S.; Access to data: S. V., A. S., R. V., W. C., P. R. S., H. M. D., H. S., R. P. F., H. R. C., G. C. K., J. K. O.; Manuscript revision, intellectual revisions, mentorship: H. M. D., H. S., R. P. F., H. R. C., G. C. K., J. K. O.; Final approval: S. V., A. S., R. V., W. C., P. R. S., H. M. D., H. S., R. P. F., H. R. C., G. C. K., J. K. O. S. V. takes responsibility for the content of the manuscript including the data and the analysis.

Financial/nonfinancial disclosures: None declared.

Role of sponsors: The sponsor had no role in the design of the study, the collection and analysis of the data, or the preparation of the manuscript.

Other contributions: We thank Larry J. Prokop, MLS, from the Mayo Clinic Libraries for his assistance with the literature search.

Additional information: The e-Tables can be found in the Supplemental Materials section of the online article.

Footnotes

FUNDING/SUPPORT: S. V. is supported by the Clinical and Translational Science Award (CTSA) Grant Number UL1 TR000135 from the National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences (NCATS), a component of the National Institutes of Health (NIH). Its contents are solely the responsibility of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official view of NIH.

Supplementary Data

References

- 1.Cuthbertson B.H., Elders A., Hall S., et al. Mortality and quality of life in the five years after severe sepsis. Crit Care. 2013;17(2):R70. doi: 10.1186/cc12616. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kotecha A.A., Vallabhajosyula S., Apala D.R., Frazee E., Iyer V.N. Clinical outcomes of weight-based norepinephrine dosing in underweight and morbidly obese patients: a propensity-matched analysis. J Intensive Care Med. 2020;35(6):554–561. doi: 10.1177/0885066618768180. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Vallabhajosyula S., Jentzer J.C., Geske J.B., et al. New-onset heart failure and mortality in hospital survivors of sepsis-related left ventricular dysfunction. Shock. 2018;49(2):144–149. doi: 10.1097/SHK.0000000000000952. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Rhodes A., Evans L.E., Alhazzani W., et al. Surviving Sepsis Campaign: international guidelines for management of sepsis and septic shock: 2016. Crit Care Med. 2017;45(3):486–552. doi: 10.1097/CCM.0000000000002255. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Beesley S.J., Weber G., Sarge T., et al. Septic cardiomyopathy. Crit Care Med. 2018;46(4):625–634. doi: 10.1097/CCM.0000000000002851. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Winkelhorst J.C., Bootsma I.T., Koetsier P.M., de Lange F., Boerma E.C. Right ventricular function and long-term outcome in sepsis: a retrospective cohort study. Shock. 2020;53(5):537–543. doi: 10.1097/SHK.0000000000001413. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Jentzer J.C., Vallabhajosyula S., Khanna A.K., Chawla L.S., Busse L.W., Kashani K.B. Management of refractory vasodilatory shock. Chest. 2018;154(2):416–426. doi: 10.1016/j.chest.2017.12.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Vallabhajosyula S., Geske J.B., Kumar M., Kashyap R., Kashani K., Jentzer J.C. Doppler-defined pulmonary hypertension in sepsis and septic shock. J Crit Care. 2019;50:201–206. doi: 10.1016/j.jcrc.2018.12.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Vallabhajosyula S., Jentzer J.C. Global longitudinal strain using speckle-tracking echocardiography in sepsis. J Intensive Care Med. 2019;34(4):352. doi: 10.1177/0885066618799636. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Vallabhajosyula S., Sakhuja A., Geske J.B., et al. Role of admission troponin-T and serial troponin-T testing in predicting outcomes in severe sepsis and septic shock. J Am Heart Assoc. 2017;6(9) doi: 10.1161/JAHA.117.005930. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Landesberg G., Gilon D., Meroz Y., et al. Diastolic dysfunction and mortality in severe sepsis and septic shock. Eur Heart J. 2012;33(7):895–903. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehr351. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Landesberg G., Jaffe A.S., Gilon D., et al. Troponin elevation in severe sepsis and septic shock: the role of left ventricular diastolic dysfunction and right ventricular dilatation. Crit Care Med. 2014;42(4):790–800. doi: 10.1097/CCM.0000000000000107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Sanfilippo F., Corredor C., Fletcher N., et al. Diastolic dysfunction and mortality in septic patients: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Intensive Care Med. 2015;41(6):1004–1013. doi: 10.1007/s00134-015-3748-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Vallabhajosyula S., Ahmed A.M., Sundaragiri P.R. Role of echocardiography in sepsis and septic shock. Ann Transl Med. 2020;8(5):150. doi: 10.21037/atm.2020.01.116. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Vallabhajosyula S., Gillespie S.M., Barbara D.W., Anavekar N.S., Pulido J.N. Impact of new-onset left ventricular dysfunction on outcomes in mechanically ventilated patients with severe sepsis and septic shock. J Intensive Care Med. 2018;33(12):680–686. doi: 10.1177/0885066616684774. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Vallabhajosyula S., Rayes H.A., Sakhuja A., Murad M.H., Geske J.B., Jentzer J.C. Global longitudinal strain using speckle-tracking echocardiography as a mortality predictor in sepsis: a systematic review. J Intensive Care Med. 2019;34(2):87–93. doi: 10.1177/0885066618761750. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Vallabhajosyula S., Kumar M., Pandompatam G., et al. Prognostic impact of isolated right ventricular dysfunction in sepsis and septic shock: an 8-year historical cohort study. Ann Intensive Care. 2017;7(1):94. doi: 10.1186/s13613-017-0319-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Cirulis M.M., Huston J.H., Sardar P., et al. Right-to-left ventricular end diastolic diameter ratio in severe sepsis and septic shock. J Crit Care. 2018;48:307–310. doi: 10.1016/j.jcrc.2018.09.025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Mekontso Dessap A., Boissier F., Charron C., et al. Acute cor pulmonale during protective ventilation for acute respiratory distress syndrome: prevalence, predictors, and clinical impact. Intensive Care Med. 2016;42(5):862–870. doi: 10.1007/s00134-015-4141-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Pulido J.N., Afessa B., Masaki M., et al. Clinical spectrum, frequency, and significance of myocardial dysfunction in severe sepsis and septic shock. Mayo Clin Proc. 2012;87(7):620–628. doi: 10.1016/j.mayocp.2012.01.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Geri G., Vignon P., Aubry A., et al. Cardiovascular clusters in septic shock combining clinical and echocardiographic parameters: a post hoc analysis. Intensive Care Med. 2019;45(5):657–667. doi: 10.1007/s00134-019-05596-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Vallabhajosyula S., Pruthi S., Shah S., Wiley B.M., Mankad S.V., Jentzer J.C. Basic and advanced echocardiographic evaluation of myocardial dysfunction in sepsis and septic shock. Anaesth Intensive Care. 2018;46(1):13–24. doi: 10.1177/0310057X1804600104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Vandenbroucke J.P., von Elm E., Altman D.G., et al. Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (STROBE): explanation and elaboration. PLoS Med. 2007;4(10):e297. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.0040297. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Levy M.M., Fink M.P., Marshall J.C., et al. 2001 SCCM/ESICM/ACCP/ATS/SIS international sepsis definitions conference. Crit Care Med. 2003;31(4):1250–1256. doi: 10.1097/01.CCM.0000050454.01978.3B. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Singer M., Deutschman C.S., Seymour C.W., et al. The Third International Consensus Definitions for Sepsis and Septic Shock (Sepsis-3) JAMA. 2016;315(8):801–810. doi: 10.1001/jama.2016.0287. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Bone R.C., Balk R.A., Cerra F.B., et al. Definitions for sepsis and organ failure and guidelines for the use of innovative therapies in sepsis. The ACCP/SCCM Consensus Conference Committee. American College of Chest Physicians/Society of Critical Care Medicine. Chest. 1992;101(6):1644–1655. doi: 10.1378/chest.101.6.1644. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Higgins J.P., Thompson S.G., Deeks J.J., Altman D.G. Measuring inconsistency in meta-analyses. BMJ. 2003;327(7414):557–560. doi: 10.1136/bmj.327.7414.557. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.DerSimonian R., Laird N. Meta-analysis in clinical trials. Control Clin Trials. 1986;7(3):177–188. doi: 10.1016/0197-2456(86)90046-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Easterbrook P.J., Gopalan R., Berlin J., Matthews D.R. Publication bias in clinical research. Lancet. 1991;337(8746):867–872. doi: 10.1016/0140-6736(91)90201-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Furian T., Aguiar C., Prado K., et al. Ventricular dysfunction and dilation in severe sepsis and septic shock: relation to endothelial function and mortality. J Crit Care. 2012;27(3) doi: 10.1016/j.jcrc.2011.06.017. 319.e9-15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Mokart D., Sannini A., Brun J.-P., et al. N-terminal pro-brain natriuretic peptide as an early prognostic factor in cancer patients developing septic shock. Crit Care. 2007;11(2):R37. doi: 10.1186/cc5721. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Orde S.R., Pulido J.N., Masaki M., et al. Outcome prediction in sepsis: speckle tracking echocardiography based assessment of myocardial function. Crit Care. 2014;18(4):R149. doi: 10.1186/cc13987. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Papanikolaou J., Makris D., Mpaka M., Palli E., Zygoulis P., Zakynthinos E. New insights into the mechanisms involved in B-type natriuretic peptide elevation and its prognostic value in septic patients. Crit Care. 2014;18(3):R94. doi: 10.1186/cc13864. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Tongyoo S., Permpikul C., Lertsawangwong S., et al. Right ventricular dysfunction in septic shock. J Med Assoc Thai. 2011;94(Suppl 1):S188–S195. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Kotecha A., Vallabhajosyula S., Coville H.H., Kashani K. Cardiorenal syndrome in sepsis: A narrative review. J Crit Care. 2018;43:122–127. doi: 10.1016/j.jcrc.2017.08.044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Orde S., Huang S.J., McLean A.S. Speckle tracking echocardiography in the critically ill: enticing research with minimal clinical practicality or the answer to non-invasive cardiac assessment? Anaesth Intensive Care. 2016;44(5):542–551. doi: 10.1177/0310057X1604400518. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Lanspa M.J., Gutsche A.R., Wilson E.L., et al. Application of a simplified definition of diastolic function in severe sepsis and septic shock. Crit Care. 2016;20(1):243. doi: 10.1186/s13054-016-1421-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Sevilla Berrios R.A., O’Horo J.C., Velagapudi V., Pulido J.N. Correlation of left ventricular systolic dysfunction determined by low ejection fraction and 30-day mortality in patients with severe sepsis and septic shock: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Crit Care. 2014;29(4):495–499. doi: 10.1016/j.jcrc.2014.03.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Rudski L.G., Lai W.W., Afilalo J., et al. Guidelines for the echocardiographic assessment of the right heart in adults: a report from the American Society of Echocardiography endorsed by the European Association of Echocardiography, a registered branch of the European Society of Cardiology, and the Canadian Society of Echocardiography. J Am Soc Echocardiogr. 2010;23(7):685–713. doi: 10.1016/j.echo.2010.05.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Vallabhajosyula S., Sakhuja A., Geske J.B., et al. Clinical profile and outcomes of acute cardiorenal syndrome type-5 in sepsis: an eight-year cohort study. PLoS One. 2018;13(1) doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0190965. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Vallabhajosyula S., Jentzer J.C., Kotecha A.A., et al. Development and performance of a novel vasopressor-driven mortality prediction model in septic shock. Ann Intensive Care. 2018;8(1):112. doi: 10.1186/s13613-018-0459-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Vieillard-Baron A., Charron C., Chergui K., Peyrouset O., Jardin F. Bedside echocardiographic evaluation of hemodynamics in sepsis: is a qualitative evaluation sufficient? Intensive Care Med. 2006;32(10):1547–1552. doi: 10.1007/s00134-006-0274-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Boissier F., Katsahian S., Razazi K., et al. Prevalence and prognosis of cor pulmonale during protective ventilation for acute respiratory distress syndrome. Intensive Care Med. 2013;39(10):1725–1733. doi: 10.1007/s00134-013-2941-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Pandompatam G., Kashani K., Vallabhajosyula S. The role of natriuretic peptides in the management, outcomes and prognosis of sepsis and septic shock. Rev Bras Ter Intensiva. 2019;31(3):368–378. doi: 10.5935/0103-507X.20190060. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Vallabhajosyula S., Wang Z., Murad M.H., et al. Natriuretic peptides to predict short-term mortality in patients with sepsis: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Mayo Clin Proc Innov Qual Outcomes. 2020;4(1):50–64. doi: 10.1016/j.mayocpiqo.2019.10.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Mahjoub Y., Pila C., Friggeri A., et al. Assessing fluid responsiveness in critically ill patients: false-positive pulse pressure variation is detected by Doppler echocardiographic evaluation of the right ventricle. Crit Care Med. 2009;37(9):2570–2575. doi: 10.1097/CCM.0b013e3181a380a3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Padang R., Chandrashekar N., Indrabhinduwat M., et al. Aetiology and outcomes of severe right ventricular dysfunction. Eur Heart J. 2020;41(12):1273–1282. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehaa037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Dugar S.P., Vallabhajosyula S. Right ventricle in sepsis: clinical and research priority. Heart. 2020;106(21):1629–1630. doi: 10.1136/heartjnl-2020-317381. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.