Abstract

Support from caregivers is an important element of mental health recovery. However, the mechanisms by which social support influences the recovery of persons with depressive, anxiety, or bipolar disorders are less understood. In this study, we describe the social support mechanisms that influence mental health recovery. A cross-sectional qualitative study was undertaken in Québec (Canada) with 15 persons in recovery and 15 caregivers—those having played the most significant role in their recovery. A deductive thematic analysis allowed for the identification and description of different mechanisms through a triangulation of perspectives from different actors. Regarding classic social support functions, several of the support mechanisms for mental health recovery were identified (emotional support, companionship, instrumental support, and validation). However, informational support was not mentioned. New mechanisms were also identified: presence, communication, and influence. Social support mechanisms evoke a model containing a hierarchy as well as links among them.

Keywords: personal recovery, social support, caregivers, critical realism, mechanisms, depression, anxiety, qualitative, deductive thematic analysis, Québec, Canada

Introduction

One in four people will be directly affected by a mental health disorder in her or his lifetime (Steel et al., 2014). Indirectly, each of us will potentially be affected by a mental health disorder through the experiences of a parent, spouse, friend, or colleague who has been affected and is working toward recovery (Santé Canada, 2002). Given the extent of this issue, we explored the ways in which caregivers may influence recovery from a mental disorder.

Recovery has become a prominent concept in the scientific literature and policies on mental health (Slade et al., 2008, 2012). Personal recovery refers to a “deeply personal, unique process of changing one’s attitudes, values, feelings, goals, skills, and/or roles [. . .] a way of living a satisfying, hopeful, and contributing life even with limitations caused by illness” (Anthony, 1993, p. 527). Personal recovery is distinct from clinical recovery, which aims for a reduction of psychiatric symptoms and functional improvement (Piat et al., 2011; Slade et al., 2008).

Several studies have identified factors that positively or negatively influence personal recovery by drawing directly from the narratives of persons in recovery (e.g., Llewellyn-Beardsley et al., 2019). However, authors highlighted how the interpersonal and social dimensions of recovery remain understudied (Mezzina et al., 2006; Schön et al., 2009; Wyder & Bland, 2014). Although often conceptualized as an individual or personal process, recovery is inherently a social process in which interpersonal relationships play a critical role (Mezzina et al., 2006; Rose, 2014; Schön et al., 2009; Wyder & Bland, 2014).

Interpersonal Relationships, Social Support and Recovery

The interpersonal aspect of recovery recurs throughout the scientific literature, with numerous studies identifying a dimension corresponding to relationships with others (e.g., Mancini et al., 2005; Mizock et al., 2014; Sullivan, 1994). In their literature review, Leamy and colleagues (2011) developed the CHIME model, which describes five recovery processes contributing to personal recovery: connectedness, hope, identity, meaning in life and empowerment. Central to our subject, connectedness refers to interpersonal relationships and support from caregivers, peers, and professionals.

Abundant mental health research focused on the concept of social support to document the influence of interpersonal relationships (Caron & Guay, 2005; Chernomas et al., 2008). Social support is a multidimensional concept whose operationalization underwent significant changes over time (Barrera, 2000; Haber et al., 2007). Early work tended to operationalize the influence of caregivers through a structural dimension of social support, that is, the person’s network. Since then, the idea has grown in complexity to include different dimensions, including social support functions (see Table 1), the source of support (friend, parent, spouse, etc.), reciprocity (direction of support: unidirectional or bidirectional), and the valence of support (positive or negative). More recently, there is a call to explore the influence of social support in a variety of areas, including mental health recovery (Chronister et al., 2015; Henderson, 2011).

Table 1.

Descriptions of Classic Social Support Functions.

| Function | Definition |

|---|---|

| Companionship support | “the availability of persons with whom one can participate in social and leisure activities such as trips and parties, cultural activities (e.g., going to movies or museums), or recreational activities such as sporting events or hiking.” (Wills & Shinar, 2000, p. 88) |

| Emotional support | “the availability of one or more persons who can listen sympathetically when an individual is having problems and can provide indications of caring and acceptance.” (Wills & Shinar, 2000, p. 88) |

| Validation | “based on the concept that social relationships can provide information about the appropriateness or normativeness of behavior.” (Wills & Shinar, 2000, p. 88) |

| Instrumental support | “practical help when necessary, such as assisting with transportation, helping with household chores and childcare and providing tangible aid such as bringing tools or lending money.” (Wills & Shinar, 2000, p. 88) |

| Informational support | “providing knowledge that is useful for solving problems, such as providing information about community resources and services or providing advice and guidance about alternative courses of action.” (Wills & Shinar, 2000, p. 88) |

Studies on the Influence of Social Support on Recovery

Social support is an important aspect of mental health recovery (e.g., Leamy et al., 2011; Mancini et al., 2005). The statistical link between social support and recovery is well established (e.g., Chou & Chronister, 2012; Corrigan & Phelan, 2004). However, the mechanisms underlying this link are not clearly established (Gleason & Iida, 2015; Henderson, 2011; Thoits, 2011). Although the term “mechanism” is often used in the cited literature, none of these authors defined it. Using a critical realist paradigm, we define a mechanism as a middle-range theory that explains how processes have an effect on recovery in a given context (Astbury & Leeuw, 2010; Fernee et al., 2019; Pawson & Tilley, 1997). Here, a mechanism is a model for relational processes that explain recovery in a given context and under given circumstances.

Furthermore, despite consensus around the important role they play, few studies specifically analyzed the influence that caregivers 1 have on recovery. Even articles that did so were often part of a project that addressed the full range of factors contributing to recovery (e.g., Aldersey & Whitley, 2015), limiting the depth of the analyses conducted. Three exceptions are presented below.

First, as part of an international study, Topor and colleagues (2006) interviewed 12 people with a mental health disorder regarding their recovery and the role that others (caregivers or professionals) played in that process. Caregivers were recognized as “standing alongside” the person in recovery; they remained present and made sure he or she was not alone. Also, caregivers provided support, such as monitoring for symptoms or engaging in advocacy with the mental health care team. Finally, over the course of the recovery process, existing relationships became increasingly reciprocal while new relationships were formed with others.

Second, based on the perspectives of 15 people in recovery, Henderson (2011) described a three-step process for recovery supported by both internal and external factors. The external factors corresponded with positive or negative social support. Positive support included acceptance, trust and commitment to a reciprocal relationship. Negative social support was non-reciprocal: a one-way relationship where caregivers adopted an “I know what is best for you” attitude (p. 6).

Third, based on six focus groups with persons that had serious mental illness, Chronister and colleagues (2015) identified six domains of support and a posteriori attributed social support functions to each of them: (a) supportive conditions (emotional), (b) day-to-day living (tangible), (c) illness management (instrumental), (d) resources and information (instrumental), (e) guidance and advice (informational), and (f) community participation support (instrumental).

Finally, some literature considers the role that families play in recovery. In their literature review on the role of families in recovery, Reupert and colleagues (2015) highlighted how familial relationships can contribute either positively or negatively to recovery. The authors synthesized the roles that families occupy, including emotional support, practical support, and offering feedback. For their part, Aldersey and Whitley (2015) re-analyzed data from a larger project on recovery to determine the role that families play. According to interviews with 54 people in recovery, families facilitated recovery by offering moral support, practical support, and providing motivation. Families could also impede recovery by acting as a stressor, displaying stigma, lacking understanding, and forcing hospitalizations.

Limitations of Prior Research

Taken together, this literature review shows that caregivers can have both a positive or negative influence on recovery. Caregivers can take on many different roles, which are often named a posteriori based on social support functions. These studies present certain limitations. First, the use of an inductive and exploratory logic limits the accumulation and comparison of research findings. In contrast, drawing from existing research and theories from the outset allows for a systematic investigation of the mechanisms and dimensions of social support, which can then be further developed in the context of recovery. Second, the studies generally consider the perspective of only one group of stakeholders (people in recovery). Social support is fundamentally interactive in nature (Gottlieb & Bergen, 2010) and should be uncovered using multiple perspectives (Aldersey & Whitley, 2015; Jacob et al., 2017). Finally, research on recovery has focused on severe mental illness even though anxiety, depressive, and bipolar disorders are the most common disorders seen in mental health services, accounting for nearly 60% of clients (Benigeri, 2007).

Study Aim

To address these limitations, we aim to analyze the influence of social support and its different dimensions on the recovery of persons with depressive, anxiety or bipolar disorders. More specifically, we draw from previous research to identify the social support mechanisms specific to mental health recovery, while allowing for the emergence of new mechanisms. The “classic” social support functions (see Table 1) form the basis of our modeling of social support mechanisms. Other aspects of social support will also be addressed, including the source (parent, spouse, friend, etc.), the reciprocity and both its positive and negative aspects. In this study we used triangulation, by considering the perspectives of both persons in recovery and their caregivers through individual interviews with members of each group. This study brings together two rich fields of scientific literature (social support and recovery), while also identifying concrete ways to improve the support offered to persons in recovery and their caregivers.

The research question for this article is: what mechanisms explain the influence of caregiver support on the recovery of persons with depressive, anxiety or bipolar disorders? Its specific objectives are as follows:

(a) Describe how classic social support functions translate as mechanisms in mental health recovery;

(b) Identify new mechanisms through which the relationship to a caregiver influences recovery;

(c) Describe how the social support mechanisms positively or negatively influence recovery.

Method

This article is part of a larger project aimed at describing and comparing the role of caregivers and professionals in the recovery of people with depressive, anxiety or bipolar disorders. To that end, semi-structured interviews were conducted with persons in recovery and their most significant caregiver and professional. This article focuses on support from caregivers.

Paradigm

This qualitative project uses a critical realist paradigm (Emmel et al., 2018; Groff, 2010; Maxwell, 2012). Ontologically, critical realism claims that a “real world” exists. However, it also assumes that this appreciation of the “real” happens through a person’s sensory, cognitive, emotional, language and cultural processes. Methodologically, this paradigm influenced the development of the research question, interviews and the data analysis (Best et al., 2016; Maxwell, 2012; Patton, 2014). For instance, the realist interview considers that the data are not just constructs, but also evidence of a real phenomenon. The formulation of questions is guided by theory. In addition, the relationship between the interviewer and the interviewee is more proximal, interactive, and aimed at learning and sense making (Manzano, 2016; Maxwell, 2012). Situating the research in the real world, the realist approach emphasizes the comparison and triangulation of sources as well as types of data (Clark, 2008; Maxwell, 2012). Finally, the realist approach is characterized by its explanatory goals and its reliance on theoretical support (Clark, 2008; Groff, 2010). As such, we find the concept of the “mechanism,” as previously defined, at the heart of realist explanations (Astbury & Leeuw, 2010; Emmel et al., 2018).

Recruiting Participants

The persons in recovery (n = 15) and their caregivers (n = 15) were recruited through theory-focused sampling and chain sampling (Patton, 2014). Beginning with persons in recovery, posters were used with two community organizations (Montréal, Québec, Canada). The province of Québec has a public and universal health system that includes mental health care, which is also supplemented by community organizations and private practitioners. Interested persons could call the first author (François Lauzier-Jobin). During this brief phone conversation, inclusion criteria were confirmed: (a) being 18 years of age or older; (b) speaking French; (c) having been diagnosed with depression or anxiety, at least 12 months prior to the interview (self-reported) 2 ; (d) considering themselves to be in recovery (self-reported); (e) being able to answer the interview questions; (f) not having severe symptoms, as measured by the Patient Health Questionnaire (PHQ-9) and the Generalized Anxiety Disorder (GAD-7) 3 ; and (g) being able and willing to identify their two most significant helpers (a caregiver and a professional) who could be interviewed.

The caregiver is the most significant carer in their informal support network, such as a spouse, family member, friend, colleague or neighbor. The inclusion criteria for caregivers were as follows: (a) identified by the person in recovery as having made a significant contribution to their recovery; (b) 18 years of age or older; (c) speaking French; and (d) able and willing to answer the interview questions.

This research project was reviewed and approved by the research ethics committee at Université du Québec à Montréal (certificate number: FSH-2015-032). Participants were offered $30 in compensation. Before obtaining written consent, the interviewer discussed the purpose of the project, the nature of the expected participation and the ethical issues involved.

Data Collection and Analysis

Semi-structured interviews with the person in recovery and their caregiver were conducted separately. The interviews took place at a time and location of the interviewees choosing within a 100 km radius of Montréal (Québec, Canada) including at their home, their workplace, or the university’s offices. The interviews conducted and analyze in French (by the first author, François Lauzier-Jobin), lasted approximately 90 minutes. All quotations were translated by a professional and revised by the authors to ensure their accuracy. An interview guide provided detailed instructions for each interview and included both primary and follow-up questions (see Supplemental File). These questions covered the person’s recovery, their relationship, and positive and negative social support. For example, for the person in recovery: “How did [name of caregiver] help with your recovery? Can you give me an example that illustrates the role this person had?” For the caregiver: “What was your role in [person’s name]’s recovery?” The same subjects were included in each interview, but information was kept confidential from one interview to the other.

Each interview was recorded and transcribed (verbatim) by a research assistant. The transcriptions were revised and imported into qualitative analysis software (NVivo10 from QSR International). The data were analyzed using thematic analysis based on Braun and Clarke (2006) and others (Miles et al., 2014; Paillé & Mucchielli, 2012; Saldaña, 2009; Zhang & Wildemuth, 2009). Deductive logic was used with the codes (themes and categories) developed based on prior research before the coding process began (Braun & Clarke, 2006). The codes were then reviewed and refined to make room for emergent results. Particular attention was given to the links between mechanisms. These were identified and listed throughout the analysis. For example, when a participant mentioned “She was present, very listening” a link between Presence and Communication was noted. The direction of the arrow represents instances where a participant naming one mechanism led to a second. Finally, citations were drawn from the transcripts to illustrate these links and a figure illustrating the articulation between the mechanisms was produced.

Results

A total of 30 individual interviews were conducted. Most participants were women for both persons in recovery (10 women, 5 men) and caregivers (9 women, 6 men). The persons in recovery had an average age of 54.4 years (SD = 12.4) and reported having mainly a bipolar (8), depressive (6), or anxiety (5) disorder. Caregivers were friends (6), spouses (5), or caregiver (two sisters, a father and a daughter).

The interviews allowed for the identification and description of different mechanisms that influence recovery: (1) presence; (2) companionship; (3) emotional support; (4) communication; (5) validation; (6) instrumental support; and (7) influence. All of these mechanisms were mentioned by both stakeholders, although some were raised more often by the persons in recovery (communication) or by caregivers (validation and instrumental support). Together, these mechanisms correspond to the social support that caregivers provide to a person in recovery. Defined in Table 2, these mechanisms are then individually described, including their operation, their effects, and important contextual variables. Although presented separately, several mechanisms can occur simultaneously.

Table 2.

Social Support Mechanisms That Emerged From the Analysis.

| Mechanism | Emergent Definition |

|---|---|

| Presence | Feeling a tie with another person. The act of being there, being present. Being accessible and available. |

| Companionship | Doing activities together. Typical, “normal” activities, unrelated to mental health issues, often as distractions. |

| Emotional support | Feeling and sharing emotions; demonstrating affection, love, intimacy. Paying attention, showing interest and consideration, demonstrating the person’s importance. |

| Communication | Speaking, listening and discussing. Involves a welcoming attitude, openness, acceptance and non-judgment. Feeling understood. |

| Validation | Informing them whether their behavior is appropriate or normal. Encouragement, reinforcement, reflection of reality. |

| Instrumental support | Acting directly on the issue or its consequences: tangible support accomplishing day-to-day tasks, specific support with their mental health issues. |

| Influence | Implicit or explicit power that takes many forms: making decisions, encouraging the adoption of behaviors thought to be beneficial, modeling. |

Generally, these mechanisms had a positive effect on recovery, although they can manifest negatively. Furthermore, each individual mechanism can occur unilaterally or reciprocally between the parties. Not only the caregiver helps the person in recovery, the latter can also support their caregiver. This aspect of reciprocity was present in nearly all of the relationships and is included in each of the mechanisms below. Many of the caregivers insisted on the fact that their relationship was reciprocal and went “both sides” (caregiver). 4

Presence

The presence of their caregiver was often the first aspect that persons in recovery mentioned: “[. . .] she’s there. She’s there for me” (person in recovery).” The mere presence of a caregiver contributes to recovery. The mechanism of presence also involves continuity in the relationship and the quality of being “consistent” (caregiver). Caregivers remained present even when the person was experiencing difficulties. Presence was perceived as even more significant when the persons have gone through challenges or difficult times together. In these cases, the caregiver continued to be present “despite” these challenges.

For some of the persons in recovery, the presence of a loved one could even become their “raison d’être” (caregiver)—a reason to continue living and fighting. This element seemed particularly important for those who experienced suicidal ideation: “She kept me alive” (person in recovery); “I don’t think she would have worked as hard for herself if I hadn’t been there” (caregiver).

Personal recovery is a process that can stretch over a long time. This can be challenging for caregivers and some of them had to take a step back, which contributed to a feeling of isolation for the person in recovery. Others even considered abandoning the relationship altogether, but ultimately decided to stay. As one caregiver describes:

Especially when they hit their lowest point, what can you do. That’s really it. That’s when the person who’s there for the person who’s ill can really get discouraged. I’ve been tempted at those times to just drop it, to leave. It’s hard, it’s very, very hard. (caregiver)

Companionship

In addition to being present, participants often spoke companionship, doing activities together, especially things that are fun and distracting:

I think I’m one of the people around him who’s pretty healthy, who would jar him out of his constant refrain of “oh, you know, things aren’t going well for me.” [. . .] Because he’d come over to our place and it was like, alright, we’re making a good dinner, we’ll have a glass of wine [. . .] Simply to not always just be talking about negative things. (caregiver)

These activities were described as positive, typical, normal, and unrelated to mental health issues. They vary significantly, depending on the individual’s interests, whether it is going for a walk around town, being in nature or going for “outings.”

Emotional Support

Emotional support was primarily expressed by sharing emotions and by showing consideration for the person in recovery that he or she is important and by showing concern. That consideration must also be communicated to the person: “worrying about me, but so that I know about it” (person in recovery). For couples, the emotional dimension was expressed as intimacy, affection and sexuality: “I cuddle up, we cuddle together. We caress each other. I try to show him my love” (caregiver).

The experience of caregivers was sometimes very difficult on an emotional level. Many mentioned feeling helpless, discouraged or distraught. Some caregivers were afraid of losing themselves in their efforts to help: “[. . .] at certain times, it can become a little overwhelming. [. . .] you don’t want to sink down into it as well. . . You’re looking into the abyss and you’re right on the edge!” (caregiver).

Communication

The mechanism of communication takes several different forms: verbal expression, listening, discussion, and the understanding it brings. Many participants expressed how speaking and listening were important aspects of support from caregivers. In these cases, listening was most appreciated when it came from a place that is welcoming, open, accepting, and free of judgment:

[This caregiver] is a person with an amazing quality of welcoming you without judgment. She accepts you as you are. Even if she doesn’t believe what you’re saying, she takes the time to listen to you. And just the fact of listening is already a huge help. (person in recovery)

Some participants associated communication more with conversation and dialogue. It was more reciprocal and involved a discussion covering several subjects that flowed in both directions: “With [my caregiver], there are times when I’m the one who talks more, and there are times when she talks more. So it’s a dialogue” (person in recovery).

Communication and the related understanding were important elements in social support from caregivers. On the other hand, persons in recovery stated that a lack of understanding and communication could impede recovery:

And [with this caregiver], often what I find difficult is that he doesn’t talk enough. [. . .] He talks to me, but it’s not often. With him, it’s more with his attitude, it’s not really verbal. So, sometimes I’d find that irritating, because I’d want him to talk more then, you know? (person in recovery)

Validation

With the validation mechanism, caregivers signaled the level of appropriateness or normality of behavior. Caregivers could support the persons by focusing on their efforts to recover:

[. . .] she recognized it and she shared it too. She has often said so. To friends, to family. “Hey, he’s working hard. I see him, he’s doing his reading, he’s meeting with groups, he’s doing his homework at home.” (person in recovery)

Caregivers could also encourage the persons in their efforts. In these cases, encouragement acted as positive reinforcement: “For every little accomplishment she has, I congratulate her all the time” (caregiver).

Finally, caregivers sometimes allowed themselves to show a reflection of reality, to point out deviations from the norm and to confront or downplay the person about problematic behaviors:

A little problem can be a big deal for her [. . .] she can inflate simple things. Well. Sometimes, I sometimes have the impression that, yeah, she’s making too big a deal of something. So then I step in to downplay it and try to get things back to normal a bit. (caregiver)

Instrumental Support

Instrumental support from a caregiver seemed to take place on two levels. First, there was tangible support to accomplish everyday tasks. Second, caregivers offered support specific to the person’s problem, namely, concerning mental health interventions.

Tangible support included frequent daily tasks such as cooking or cleaning: “cooking, washing, dusting, sweeping, making beds, [. . .] It’s really everyday life” (caregiver). Help was particularly important when the person was going through difficult periods: “It’s certain that, if I see she’s having a more difficult day, I’ll take more responsibility” (caregiver). This help also seemed particularly important for couples that had children at home. Persons in recovery shared how their spouses took “responsibility for everyday tasks [. . .] whether that’s cleaning, making food, the fridge, the laundry” (caregiver).

The persons in recovery received professional help for their mental health disorder. Although not responsible for therapeutic interventions, caregivers could still help by supporting the professional intervention in different ways. They could show an interest in the interventions, question and listen to the persons in recovery and even contribute to tasks between therapy sessions (such as homework):

[. . .] I’m not embarrassed to ask her for help with the homework we sometimes have, to try and clarify it, to see how she understands it so she can communicate that to me and so I can try to better understand all this. (person in recovery)

[. . .] But when she goes to her course there, she’ll talk more about it with me, since it’s more about working on yourself. Because, yeah, sometimes I need to work on myself too. We all need to work on ourselves. (caregiver)

Conversely, the persons in recovery highlighted how damaging it could be to feel like their loved ones did not support their professional care. This lack of support often focused on medication:

When I got out of the hospital and everything, my brother wouldn’t stop saying, “oh, those pills are nothing but placebos you know, I don’t know what you were even doing there, I don’t understand. But, oh well, it’s your choice.” But I could see that it wasn’t at all like he believed. Y’know, he didn’t think I really needed help, all of that. But I needed it; I was suicidal. I needed it, but he couldn’t see the seriousness of what I was living. (person in recovery)

For their part, caregivers expressed their feeling of being left to their own devices in their role as caregivers. Despite efforts to find support, caregivers felt like they lacked specific resources to support them in their role:

There’s no easy way to face this issue or to know what to do. There’s no instruction manual for all this. [. . .] you’re sort of just left on your own. For anyone that lacks the tools to manage that, it’s . . . It’s problematic [. . .]. (caregiver)

Influence

When asked, most caregivers recognized that they had some power or influence over the person in recovery. This influence could take many forms. For example, some caregivers would try to influence the person in recovery through discussion. This type of influence can be similar to the validation mechanism:

[. . .] if I see that he has an idea that’s starting to get out of control. Well, I know that I have the ability to influence him. For sure. “Look, if we take this and we put it back into context, think about it a bit.” “Yeah, yeah.” He’s open to that. (caregiver)

Furthermore, caregivers could exert influence by encouraging the person they are helping to adopt behaviors and habits that they believe are beneficial, such as physical activity and a healthy diet:

Often, I’m the one to call her and force her a bit [. . .] sometimes she doesn’t want to go out. I ask her: “Have you gone out today?” She says, “No.” “OK, well, come on, we’re going for a walk.” “Ah well, I’ll call you back in five minutes, I’ll think about it.” “Don’t think too hard there, because we’re going for a walk.” You know, I push her. (caregiver)

Some caregivers highlighted how they would try to influence the person to “enjoy life” (caregiver) and to take advantage of the “good things in life” (caregiver). Finally, caregivers could influence the person through their own actions, as a model. As one caregiver explains:

But I think that, for example, I definitely have influence. I have an aspect where, I’m an engineer, so I’m very Cartesian, factual and focused on action. So, because she sees me doing things, naturally I have an influence on her, because sometimes she’ll say “OK, I’m coming along with you,” or we’ll change the way we do things because she’ll see me doing something and it’s something that she’ll adopt as a behaviour or as an activity she wants to do. (caregiver)

Linkages Between the Mechanisms

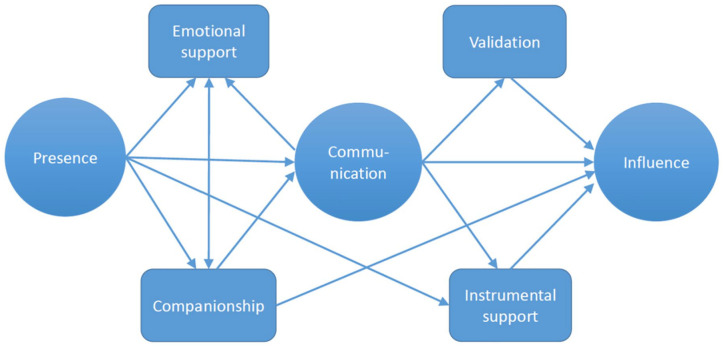

Social support mechanisms can be activated independently or simultaneously. One of the advantages of our methodology is that it enabled us to connect these mechanisms based on their co-occurrences. In Figure 1, the arrows represent links between the different mechanisms, as identified by respondents.

Figure 1.

Schematization of the links between social support mechanisms.

It should be noted that a certain hierarchy among the mechanisms emerged, as shown by the shapes in the model. The three central or “primary” mechanisms were presence, communication, and influence. It is hard, if not impossible, to imagine a support interaction that would operate without at least one of these. The four “secondary” mechanisms were closer to the classic social support functions (companionship, emotional support, validation, and instrumental support). The secondary mechanisms were less linked with each other and seemed to follow from, or depend on, the primary mechanisms.

In discussions with the participants, presence was normally the first mechanism mentioned, often accompanied by a reference to another support function provided by the caregiver: “I knew that if I needed physical, emotional, sentimental support right away, whatever, well, the phone was right there” (person in recovery).

Companionship involved doing things with the person. These activities had a social function allowing people to be together. As such, there was a strong link to presence. Social activities also became opportunities to talk and to listen to each other (communication): “Last week, we went for dinner at a restaurant and we talked about all kinds of things, including his son” (caregiver).

Several participants highlighted the central role that communication played in recovery. Presence and companionship allowed for the activation of the communication mechanism. For its part, communication allowed the person to share their emotions and vent: “[. . .] it’s important to talk. But you also need to give him a chance to blow off steam” (caregiver). Furthermore, communication allowed for the activation of validation, influence and instrumental support. These links were most often identified by the caregivers.

Finally, influence manifested more subtly in the other mechanisms: encouraging the person to take a walk with you (companionship), make food for someone who is not eating well (instrumental support), giving advice (communication) or confronting the person about their problematic behaviors (validation):

[. . .] whether we like it or not, at some point, we have influence. Even if we want to leave them the choice. Well, at some point, I think that there is a certain choice that we make for ourselves that will influence the other in the right direction. Like encouraging their activities, encouraging certain orientations, to make decisions, but to make it rationalized. [To be] an advisor that can give some advice on certain aspects of a decision that she could make. (caregiver)

Concerning the link between influence and validation, even if they were intertwined, the decision was made to separate them, because influence is more than just validation and since influence manifests in the other mechanisms.

Discussion

Both the testimonials of persons in recovery and empirical research showed that social support by caregivers is an essential aspect of mental health recovery. To further develop our understanding of this subject, we conducted interviews with persons in recovery and their most significant caregiver to elaborate on the mechanisms at the heart of this support. Our analyses showed how, in the specific case of mental health recovery, certain classic social support functions operate as mechanisms. At the same time, we allowed for new mechanisms to emerge. An emphasis was placed on the notion of mechanism in line with critical realism, which considers that science (Clark, 2008; Groff, 2010) and qualitative research (Maxwell, 2012) should have an explanatory aim.

Our analysis identified several mechanisms that correspond to the classic social support functions, reinforcing their relevance and the importance of support in mental health recovery. Among these, companionship, emotional support, validation, and instrumental support remain important aspects of the support provided by caregivers, both from the perspective of the persons in recovery and their caregivers. On the other hand, our findings did not identify the presence of informational support: “providing knowledge that is useful for solving problems” (Wills & Shinar, 2000, p. 88). Berkman and colleagues (2000) noted that it can be hard to distinguish informational support from emotional support and validation.

Although the term “instrumental support” has been retained since it is the most used, we remain dissatisfied with it. We prefer “problem-focused support,” which could also include informational and intervention support. As such, one addition from our study is the inclusion of intervention support within instrumental support. Caregivers can contribute to recovery by supporting the therapeutic interventions of professionals (e.g., helping with therapeutic exercises) or hinder it by working against them (e.g., expressing doubts about prescribed medication). This finding offers a potential explanation for the relationship between social support and professional interventions. Social support has an influence on the use of mental health services (Albert et al., 1998; Klauer, 2005; Kogstad et al., 2013), commitment to treatment (for a review see DiMatteo, 2004) and the effects of psychotherapy (for a review see Roehrle & Strouse, 2008). Our study illustrates some of the processes by which this support operates: showing an interest in the interventions, asking questions, listening and even helping with the tasks to be completed between sessions with the therapist.

Furthermore, our analyses allowed for the addition of three new mechanisms typically not included in classic social support functions. First, we confirmed the inclusion of presence as a social support mechanism for recovery. This mechanism was initially suggested by Topor and colleagues (2006), who highlighted the importance of having caregivers present with persons (“standing alongside”) and of not leaving them on their own. We found that presence was often the first aspect identified by respondents.

Second, numerous participants identified the importance of communication in their recovery. The importance of communication (speaking, listening, dialogue and understanding) is consistent with prior research on mental health. For example, Pennebaker (1995) and Niederhoffer and Pennebaker (2009) found that simply speaking has benefits for mental health (see also Ware et al., 2004 for a similar finding with mental health interventions). Speaking and listening are also included in the literature on social support (e.g., Lee et al., 2019), peer support (e.g., MacLellan et al., 2015; Mancini, 2019) and professional interventions (e.g., Gilburt et al., 2008). As such, it would seem essential for this element to be included among the mechanisms of social support.

Third, we suggest a final mechanism: influence. For authors working on these concepts, power and influence are ubiquitous in human activity (Grose et al., 2014; Prilleltensky, 2008). This focus on power is a distinguishing feature of critical realism and highlights its link with critical theory (Patton, 2014). While difficult to define, power can be analyzed on different levels: individual, interpersonal and structural (Grose et al., 2014). In our study, the influence mechanism corresponded to an interpersonal level of power. Social influence is a mechanism that links the quality of interpersonal relationships to health (Kawachi & Berkman, 2001; Thoits, 2011), usually through the promotion of healthy behaviors (e.g., Houle et al., 2017). However, several authors have noted that it remains understudied, especially in psychology (Grose et al., 2014; Prilleltensky, 2008; Thoits, 2011). Most caregivers we interviewed recognized that they exercise power or influence over the person they are helping. Further, our findings show that this influence can take many forms: it can operate explicitly through a discussion, through the promotion of healthy behaviors or by acting as a model. However, our results did not find any differences regarding the access to different resources or unequal relationships: two traditionally important dimensions in the study of interpersonal power (Prilleltensky, 2008; Thoits, 2011). Influence would seem to be a central aspect of the experience of care and it deserves to be systematically included in future analyses.

Our study also treats the concepts of “negative” social support and “reciprocity” as fully distinct. This is contrary to Henderson (2011), who implied that relationships are negative because they are not reciprocal. Our findings show that each mechanism can have a positive or negative impact on recovery. “Negative” social support does not appear as a mechanism on its own, but rather as a dimension (valence) of each mechanism. Specifically, depending on the way in which it is activated, each of the mechanisms can have a positive or negative effect on recovery.

Practical Implications

The identification of social support mechanisms contributes to the development of interventions based on theory (Kawachi & Berkman, 2001; Thoits, 2011). The focus on mechanisms in social support enables us to identify, reinforce, develop, and improve the processes responsible for recovery.

Our findings also highlight the difficulties caregivers sometimes face in their role. The role of caregivers is emotionally challenging, to the point where persons often express their own need for support. Paradoxically, although the presence of a caregiver supports recovery, several participants discussed how they had considered abandoning that role at one time or another. It seems critical to listen to their needs to support them in this crucial role. Unfortunately, despite the importance of caregivers, their need for support is often neglected (Yesufu-Udechuku et al., 2015). Prior research has shown the positive effects of different interventions with caregivers, both for them and for the person in recovery (Chien & Norman, 2009; Lobban et al., 2013; Macleod et al., 2011; Yesufu-Udechuku et al., 2015). Guided by these results, interventions could offer different ways of helping based on the seven mechanisms. In addition to developing necessary skills to support the person in recovery, these interventions could emphasize the importance of self-care for the caregivers themselves and getting the help they need. Participation in group interventions could increase caregivers’ understanding of the disorders, improve their adaptation strategies, reduce their stress, and lessen their burden (Chien & Norman, 2009; Macleod et al., 2011).

Given the critical importance of social support for recovery (e.g., Leamy et al., 2011), it is essential that it be properly discussed with the person in recovery (Hogan et al., 2002). In an individual intervention, the first step would be to evaluate the social support available to the person in recovery, through interviews, clinical observations, and standardized tools or, preferably, through a combination of these (Bertolino et al., 2009; Caron & Guay, 2005; Cohen et al., 2000; Dulmus & Nisbet, 2013; Milne, 1999; Rashid et al., 2017). More specifically, evaluation can serve to clarify not only the current state of support, but also the desired situation. The gap between the actual and the desired situation can be used to formulate the problem and establish intervention goals. Subsequently, it is possible to work on social support through individual interventions, whether by working on the person’s perceptions and expectations or working on social skills training. The professional can go even further by integrating caregivers in the treatment or by supporting them through different recognized approaches such as couples therapy, family therapy, support for caregivers or peer support (Hogan et al., 2002; Milne, 1999; Morin & St-Onge, 2019; Perese & Wolf, 2005).

Finally, beyond interventions, this study demonstrates the importance of considering the perspectives of both stakeholder groups: persons in recovery and their caregivers. Social support is an interactive process (e.g., Gottlieb & Bergen, 2010) and it is important that we go beyond methodological individualism and study it according to the perspectives of different actors (Aldersey & Whitley, 2015; Jacob et al., 2017). Caregivers provide important and relevant information that should be integrated in research, evaluations, and implementation of services. Alas, the authors of a recent review (strategies for engaging patients and families in collaborative care programs) noted how rare it is for families to be engaged even in these types of programs (Menear et al., 2020). One possible solution is the use of trialogues, which bring together persons in recovery, their caregivers, and professionals for discussion seminars on mental health issues (Amering et al., 2012). Although their effects have never been systematically studied, trialogues have the potential to reduce the isolation of different actors, favor knowledge acquisition, creating a shared vocabulary, and provide a sense of empowerment for all participants, including caregivers (Amering et al., 2012).

Strengths and Limitations

One strength of our study is the way in which it simultaneously considers the perspectives of both persons in recovery and their caregivers. We believe that this triangulation of perspectives increases the validity of the findings, especially in a context where the perspective of caregivers generally receives less attention (Jacob et al., 2017).

In addition, our study draws explicitly on the literature on social support to document the role of caregivers in recovery. This allowed for the use of a deductive qualitative approach to analyze the presence of mechanisms and the links between them. For example, having asked each of the caregivers about it, we can affirm that nearly all participants recognize that support includes an aspect of power and influence. Building on prior research also facilitates theoretical generalizations (Patton, 2014; Smith, 2018).

In terms of limitations, this study would have benefited from developing a more detailed context of the participants’ lives: socioeconomic status, age of caregivers, size of their network, and so on. These contextual elements would have helped to better interpret certain aspects of participants’ experiences, as well as placing the support mechanisms in a fuller context. This is an important limitation of our study especially from a critical realist stance. This limitation may be due to an initial emphasis on relationship dimensions that limited the study of some individual characteristics. Nevertheless, we recommend that future studies include these dimensions. Another important dimension to include in further studies is the caregivers’ experience of their own mental health concerns. Nonetheless, without prompting, a third of the caregivers stated that they have or have had such an experience.

Another limit involves the use of self-reported diagnoses, with all its potential bias. Diagnoses are self-reported to be consistent with the philosophy of the recovery approach and of the two community organizations. A recovery approach puts less emphasis on a person’s diagnosis than a more traditional approach would. It would be worthwhile to expand future research to include other disorders or to propose an analysis differentiated by diagnosis as they may present specific issues.

Finally, the caregiver interviewed was the person who had most contributed to the recovery process. It is likely that this method of recruitment affected the results, particularly for negative aspects of social support, which may have been underestimated.

Conclusion

In this study, we described social support mechanisms specific to mental health recovery. Its findings empirically showed how most classic social support functions are applicable to mental health recovery, in addition to proposing new mechanisms: presence, communication, and influence. The results demonstrate both the breadth of the role played by caregivers in recovery and their own need for support while exercising this critical but demanding role.

Supplemental Material

Supplemental material, sj-pdf-1-qhr-10.1177_10497323211039828 for Caregiver Support in Mental Health Recovery: A Critical Realist Qualitative Research by François Lauzier-Jobin and Janie Houle in Qualitative Health Research

Author Biographies

Francois Lauzier-Jobin is a PhD Student in community psychology at Université du Québec à Montréal and works at Université de Sherbrooke.

Janie Houle is a professor of community psychology at Université du Québec à Montréal and chairholder of the Chaire de recherche sur la réduction des inégalités sociales de santé.

Although imperfect, the term “caregiver” was chosen to designate the person who has made the biggest contribution to recovery. This term was chosen over “family member,” “family caregiver,” or “carer.”

Diagnoses are self-reported to be consistent with the philosophy of the recovery approach and of the two community organizations. The study was originally intended to include only these two diagnostic groups, but the comorbidity with bipolar disorder led us to change the focus of the research during recruitment to adequately reflect our sample characteristics. Criteria (c) and (f) are reported as they occurred. Hence the disparity between our sample and our inclusion criteria.

Measuring the severity of depressive symptoms, the PHQ-9 includes nine items scored from 0 to 3 for a total score between 0 and 27, with a 20 or higher indicating severe symptoms. Measuring the severity of symptoms for anxiety, GAD-7 includes seven items scored from 0 to 3 for a total score between 0 and 21, with a 15 or higher indicating severe symptoms.

Note: All of the citations included from the interviews have been translated from the original French by a professional translator.

Footnotes

Declaration of Conflicting Interests: The authors declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Funding: The author(s) disclosed receipt of the following financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article: This research was made possible by the financial support to the first author (FLJ) by the “Fonds de recherche sur la société et la culture” and UQAM’s grant “Fondation de J.-A. De Sève”.

ORCID iD: François Lauzier-Jobin  https://orcid.org/0000-0003-0031-4678

https://orcid.org/0000-0003-0031-4678

Supplemental Material: Supplemental Material for this article is available online at journals.sagepub.com/home/qhr. Please enter the article’s DOI, located at the top right-hand corner of this article in the search bar, and click on the file folder icon to view.

References

- Albert M., Becker T., McCrone P., Thornicroft G. (1998). Social networks and mental health service utilisation—A literature review. International Journal of Social Psychiatry, 44(4), 248–266. 10.1177/002076409804400402 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aldersey H. M., Whitley R. (2015). Family influence in recovery from severe mental illness. Community Mental Health Journal, 51(4), 467–476. 10.1007/s10597-014-9783-y [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Amering M., Mikus M., Steffen S. (2012). Recovery in Austria: Mental health trialogue. International Review of Psychiatry, 24(1), 11–18. 10.3109/09540261.2012.655713 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Anthony W. A. (1993). Recovery from mental illness: The guiding vision of the mental health service system in the 1990s. Psychosocial Rehabilitation Journal, 16(4), 11–23. 10.1037/h0095655 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Astbury B., Leeuw F. L. (2010). Unpacking black boxes: Mechanisms and theory building in evaluation. American Journal of Evaluation, 31(3), 363–381. 10.1177/1098214010371972 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Barrera M., Jr. (2000). Social support research in community psychology. In Rappaport J., Seidman E. (Eds.), Handbook of community psychology (pp. 215–245). Kluwer Academic Publishers. https://www.springer.com/gp/book/9780306461606 [Google Scholar]

- Benigeri M. (2007). L’utilisation des services de santé mentale par les Montréalais en 2004-2005 [The use of mental health services by Montrealers in 2004-2005]. Montréal: Agence de la santé et des services sociaux de Montréal. http://collections.banq.qc.ca/ark:/52327/bs36687 [Google Scholar]

- Berkman L. F., Glass T., Brissette I., Seeman T. E. (2000). From social integration to health: Durkheim in the new millennium. Social Science & Medicine, 51(6), 843–857. 10.1016/S0277-9536(00)00065-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bertolino B., Kiener M., Patterson R. (2009). The therapist’s notebook on strengths and solution-based therapies: Homework, handouts, and activities. Routledge. 10.4324/9780203877609 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Best P., Gil-Rodriguez E., Manktelow R., Taylor B. J. (2016). Seeking help from everyone and no-one: Conceptualizing the online help-seeking process among adolescent males. Qualitative Health Research, 26(8), 1067–1077. 10.1177/1049732316648128 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Braun V., Clarke V. (2006). Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qualitative Research in Psychology, 3(2), 77–101. 10.1191/1478088706qp063oa [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Caron J., Guay S. (2005). Soutien social et santé mentale: concept, mesures, recherches récentes et implications pour les cliniciens [Social support and mental health: Concept, measures, recent research and implications for clinicians]. Santé mentale au Québec, 30(2), 15–41. 10.7202/012137ar [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chernomas W. M., Clarke D. E., Marchinko S. (2008). Relationship-based support for women living with serious mental illness. Issues in Mental Health Nursing, 29(5), 437–453. 10.1080/01612840801981108 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chien W.-T., Norman I. (2009). The effectiveness and active ingredients of mutual support groups for family caregivers of people with psychotic disorders: A literature review. International Journal of Nursing Studies, 46(12), 1604–1623. 10.1016/j.ijnurstu.2009.04.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chou C.-C., Chronister J. A. (2012). Social tie characteristics and psychiatric rehabilitation outcomes among adults with serious mental illness. Rehabilitation Counseling Bulletin, 55(2), 92–102. 10.1177/0034355211413139 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Chronister J., Chou C.-C., Kwan K.-L. K., Lawton M., Silver K. (2015). The meaning of social support for persons with serious mental illness. Rehabilitation Psychology, 60(3), 232–245. 10.1037/rep0000038 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clark A. (2008). Critical realism. In Given L. M. (Ed.), The SAGE encyclopedia of qualitative research methods (pp. 168–170). SAGE. https://us.sagepub.com/en-us/nam/the-sage-encyclopedia-of-qualitative-research-methods/book229805 [Google Scholar]

- Cohen S., Gottlieb B. H., Underwood L. G. (2000). Social relationships and health. In Cohen S., Underwood L. G., Gottlieb B. H. (Eds.), Social support measurement and intervention: A guide for health and social scientists (pp. 3–25). Oxford University Press. 10.1093/med:psych/9780195126709.003.0001 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Corrigan P. W., Phelan S. M. (2004). Social support and recovery in people with serious mental illnesses. Community Mental Health Journal, 40(6), 513–523. 10.1007/s10597-004-6125-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DiMatteo M. R. (2004). Social support and patient adherence to medical treatment: A meta-analysis. Health Psychology, 23(2), 207–218. 10.1037/0278-6133.23.2.207 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dulmus C. N., Nisbet B. C. (2013). Person-centered recovery planner for adults with serious mental illness. John Wiley. https://www.wiley.com/en-us/Person+Centered+Recovery+Planner+for+Adults+with+Serious+Mental+Illness-p-9781118653357 [Google Scholar]

- Emmel N., Greenhalgh J., Manzano A., Monaghan M., Dalkin S. (Eds.). (2018). Doing realist research. SAGE. https://uk.sagepub.com/en-gb/eur/doing-realist-research/book252047 [Google Scholar]

- Fernee C. R., Mesel T., Andersen A. J., Gabrielsen L. E. (2019). Therapy the natural way: A realist exploration of the wilderness therapy treatment process in adolescent mental health care in Norway. Qualitative Health Research, 29(9), 1358–1377. 10.1177/1049732318816301 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gilburt H., Rose D., Slade M. (2008). The importance of relationships in mental health care: A qualitative study of service users’ experiences of psychiatric hospital admission in the UK. BMC Health Services Research, 8(1), Article 92. 10.1186/1472-6963-8-92 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gleason M. E. J., Iida M. (2015). Social support. In Mikulincer M., Shaver P. R., Simpson J. A., Dovidio J. F. (Eds.), APA handbooks in psychology®. APA handbook of personality and social psychology: Vol. 3. Interpersonal relations (pp. 351–370). American Psychological Association. 10.1037/14344-013 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Gottlieb B. H., Bergen A. E. (2010). Social support concepts and measures. Journal of Psychosomatic Research, 69(5), 511–520. 10.1016/j.jpsychores.2009.10.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Groff R. (2010). Critical realism. In Jackson II R. L., Hogg M. A. (Eds.), Encyclopedia of identity (pp. 153–155). SAGE. https://sk.sagepub.com/reference/identity [Google Scholar]

- Grose R., Dutt A., Grabe S. (2014). Power, overview. In Teo T. (Ed.), Encyclopedia of critical psychology (pp. 1474–1479). Springer. 10.1007/978-1-4614-5583-7_632 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Haber M. G., Cohen J. L., Lucas T., Baltes B. B. (2007). The relationship between self-reported received and perceived social support: A meta-analytic review. American Journal of Community Psychology, 39(1–2), 133–144. 10.1007/s10464-007-9100-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Henderson A. R. (2011). A substantive theory of recovery from the effects of severe persistent mental illness. International Journal of Social Psychiatry, 57(6), 564–573. 10.1177/0020764010374417 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hogan B. E., Linden W., Najarian B. (2002). Social support interventions: Do they work? Clinical Psychology Review, 22(3), 381–440. 10.1016/S0272-7358(01)00102-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Houle J., Meunier S., Coulombe S., Mercerat C., Gaboury I., Tremblay G., de Montigny F., Cloutier L., Roy B., Auger N., Lavoie B. (2017). Peer positive social control and men’s health-promoting behaviors. American Journal of Men’s Health, 11(5), 1569–1579. 10.1177/1557988317711605 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jacob S., Munro I., Taylor B. J., Griffiths D. (2017). Mental health recovery: A review of the peer-reviewed published literature. Collegian, 24(1), 53–61. 10.1016/j.colegn.2015.08.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kawachi I., Berkman L. F. (2001). Social ties and mental health. Journal of Urban Health, 78(3), 458–467. 10.1093/jurban/78.3.458 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klauer T. (2005). Psychotherapie und soziale unterstützung [Psychotherapy and social support]. Psychotherapeut, 50(6), 425–436. 10.1007/s00278-005-0451-0 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kogstad R. E., Mönness E., Sörensen T. (2013). Social networks for mental health clients: Resources and solution. Community Mental Health Journal, 49(1), 95–100. 10.1007/s10597-012-9491-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leamy M., Bird V., Le Boutillier C., Williams J., Slade M. (2011). Conceptual framework for personal recovery in mental health: Systematic review and narrative synthesis. The British Journal of Psychiatry, 199(6), 445–452. 10.1192/bjp.bp.110.083733 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee D. S., Orvell A., Briskin J., Shrapnell T., Gelman S. A., Ayduk O., Ybarra O., Kross E. (2019). When chatting about negative experiences helps-and when it hurts: Distinguishing adaptive versus maladaptive social support in computer-mediated communication. Emotion, 20(3), 368–375. 10.1037/emo0000555 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Llewellyn-Beardsley J., Rennick-Egglestone S., Callard F., Crawford P., Farkas M., Hui A., Manley D., McGranahan R., Pollock K., Ramsay A., Sælør K. T., Wright N., Slade M. (2019). Characteristics of mental health recovery narratives: Systematic review and narrative synthesis. PLOS ONE, 14(3), Article e0214678. 10.1371/journal.pone.0214678 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lobban F., Postlethwaite A., Glentworth D., Pinfold V., Wainwright L., Dunn G., Clancy A., Haddock G. (2013). A systematic review of randomised controlled trials of interventions reporting outcomes for relatives of people with psychosis. Clinical Psychology Review, 33(3), 372–382. 10.1016/j.cpr.2012.12.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MacLellan J., Surey J., Abubakar I., Stagg H. R. (2015). Peer support workers in health: A qualitative metasynthesis of their experiences. PLOS ONE, 10(10), Article e0141122. 10.1371/journal.pone.0141122 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Macleod S. H., Elliott L., Brown R. (2011). What support can community mental health nurses deliver to carers of people diagnosed with schizophrenia? Findings from a review of the literature. International Journal of Nursing Studies, 48(1), 100–120. 10.1016/j.ijnurstu.2010.09.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mancini M. A. (2019). Strategic storytelling: An exploration of the professional practices of mental health peer providers. Qualitative Health Research, 29(9), 1266–1276. 10.1177/1049732318821689 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mancini M. A., Hardiman E. R., Lawson H. A. (2005). Making sense of it all: Consumer providers’ theories about factors facilitating and impeding recovery from psychiatric disabilities. Psychiatric Rehabilitation Journal, 29(1), 48–55. 10.2975/29.2005.48.55 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Manzano A. (2016). The craft of interviewing in realist evaluation. Evaluation, 22(3), 342–360. 10.1177/1356389016638615 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Maxwell J. A. (2012). A realist approach for qualitative research. SAGE. https://us.sagepub.com/en-us/nam/node/46930/print [Google Scholar]

- Menear M., Dugas M., Careau E., Chouinard M.-C., Dogba M. J., Gagnon M.-P., Gervais M., Gilbert M., Houle J., Kates N., Knowles S., Martin N., Nease D. E., Zomahoun H. T. V., Jr., Légaré F. (2020). Strategies for engaging patients and families in collaborative care programs for depression and anxiety disorders: A systematic review. Journal of Affective Disorders, 263, 528–539. 10.1016/j.jad.2019.11.008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mezzina R., Davidson L., Borg M., Marin I., Topor A., Sells D. (2006). The social nature of recovery: Discussion and implications for practice. American Journal of Psychiatric Rehabilitation, 9(1), 63–80. 10.1080/15487760500339436 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Miles M. B., Huberman A. M., Saldaña J. (2014). Qualitative data analysis: A methods sourcebook. SAGE. https://us.sagepub.com/en-us/nam/qualitative-data-analysis/book246128 [Google Scholar]

- Milne D. L. (1999). Social therapy: A guide to social support interventions for mental health practitioners. John Wiley. https://www.wiley.com/en-us/Social+Therapy%3A+A+Guide+to+Social+Support+Interventions+for+Mental+Health+Practitioners-p-9780471987277 [Google Scholar]

- Mizock L., Russinova Z., Shani R. (2014). New roads paved on losses: Photovoice perspectives about recovery from mental illness. Qualitative Health Research, 24(11), 1481–1491. 10.1177/1049732314548686 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morin M.-H., St-Onge M. (2019). L’intervention familiale dans la pratique du travail social en santé mentale [Family intervention in mental health social work practice]. In Bergeron-Leclerc C., Morin M.-H., Dallaire B., Cormier C. (Eds.), La pratique du travail social en santé mentale: apprendre, comprendre, s’engager (pp. 161–186). Presses de l’Université du Québec. https://www.puq.ca/catalogue/livres/pratique-travail-social-sante-mentale-3166.html [Google Scholar]

- Niederhoffer K. G., Pennebaker J. W. (2009). Sharing one’s story: On the benefits of writing or talking about emotional experience. In Lopez S. J., Snyder C. R. (Eds.), Oxford library of psychology. Oxford handbook of positive psychology (2nd ed., pp. 621–632). Oxford University Press. https://www.oxfordhandbooks.com/view/10.1093/oxfordhb/9780195187243.001.0001/oxfordhb-9780195187243 [Google Scholar]

- Paillé P., Mucchielli A. (2012). L’analyse qualitative en sciences humaines et sociales [Qualitative analysis in the humanities and social sciences] (3rd ed.). Armand Colin. https://www.cairn.info/l-analyse-qualitative-en-sciences-humaines–9782200249045.htm [Google Scholar]

- Patton M. Q. (2014). Qualitative research & evaluation methods: Integrating theory and practice. SAGE. https://us.sagepub.com/en-us/nam/qualitative-research-evaluation-methods/book232962 [Google Scholar]

- Pawson R., Tilley N. (1997). Realistic evaluation. SAGE. https://uk.sagepub.com/en-gb/eur/realistic-evaluation/book205276 [Google Scholar]

- Pennebaker J. W. (1995). Emotion, disclosure, and health: An overview. In Pennebaker J. W. (Ed.), Emotion, disclosure, & health (pp. 3–10). American Psychological Association. 10.1037/10182-015 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Perese E. F., Wolf M. (2005). Combating loneliness among persons with severe mental illness: Social network interventions’ characteristics, effectiveness, and applicability. Issues in Mental Health Nursing, 26(6), 591–609. 10.1080/01612840590959425 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Piat M., Sabetti J., Fleury M.-J., Boyer R., Lesage A. (2011). “Who believes most in me and in my recovery”: The importance of families for persons with serious mental illness living in structured community housing. Journal of Social Work in Disability & Rehabilitation, 10(1), 49–65. 10.1080/1536710X.2011.546310 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prilleltensky I. (2008). The role of power in wellness, oppression, and liberation: The promise of psychopolitical validity. Journal of Community Psychology, 36(2), 116–136. 10.1002/jcop.20225 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Rashid T., Howes R. N., Louden R. (2017). Positive psychotherapy: A wellbeing approach to recovery. In Slade M., Oades L., Jarden A. (Eds.), Wellbeing, recovery and mental health (pp. 111–132). Cambridge University Press. 10.1017/9781316339275.011 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Reupert A., Maybery D., Cox M., Scott Stokes E. (2015). Place of family in recovery models for those with a mental illness. International Journal of Mental Health Nursing, 24(6), 495–506. 10.1111/inm.12146 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roehrle B., Strouse J. (2008). Influence of social support on success of therapeutic interventions: A meta-analytic review. Psychotherapy: Theory, Research, Practice, Training, 45(4), 464–476. 10.1037/a0014333 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rose D. (2014). The mainstreaming of recovery. Journal of Mental Health, 23(5), 217–218. 10.3109/09638237.2014.928406 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saldaña J. (2009). The coding manual for qualitative researchers. SAGE. https://uk.sagepub.com/en-gb/eur/the-coding-manual-for-qualitative-researchers/book243616 [Google Scholar]

- Santé Canada. (2002). Profil national des personnes soignantes au Canada–2002 [National profile of caregivers in Canada–2002]. https://www.canada.ca/fr/sante-canada/services/systeme-soins-sante/rapports-publications/soins-domicile-continus/profil-national-personnes-soignantes-canada-2002-rapport-final.html

- Schön U.-K., Denhov A., Topor A. (2009). Social relationships as a decisive factor in recovering from severe mental illness. The International Journal of Social Psychiatry, 55(4), 336–347. 10.1177/0020764008093686 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Slade M., Amering M., Oades L. (2008). Recovery: An international perspective. Epidemiology and Psychiatric Sciences, 17(2), 128–137. 10.1017/s1121189x00002827 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Slade M., Leamy M., Bacon F., Janosik M., Le Boutillier C., Williams J., Bird V. (2012). International differences in understanding recovery: Systematic review. Epidemiology and Psychiatric Sciences, 21(4), 353–364. 10.1017/S2045796012000133 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith B. (2018). Generalizability in qualitative research: Misunderstandings, opportunities and recommendations for the sport and exercise sciences. Qualitative Research in Sport, Exercise and Health, 10(1), 137–149. 10.1080/2159676X.2017.1393221 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Steel Z., Marnane C., Iranpour C., Chey T., Jackson J. W., Patel V., Silove D. (2014). The global prevalence of common mental disorders: A systematic review and meta-analysis 1980–2013. International Journal of Epidemiology, 43(2), 476–493. 10.1093/ije/dyu038 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sullivan W. P. (1994). A long and winding road: The process of recovery from severe mental illness. Innovations and Research, 3(3), 19–27. [Google Scholar]

- Thoits P. A. (2011). Mechanisms linking social ties and support to physical and mental health. Journal of Health and Social Behavior, 52(2), 145–161. 10.1177/0022146510395592 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Topor A., Borg M., Mezzina R., Sells D., Marin I., Davidson L. (2006). Others: The role of family, friends, and professionals in the recovery process. American Journal of Psychiatric Rehabilitation, 9(1), 17–37. 10.1080/15487760500339410 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ware N. C., Tugenberg T., Dickey B. (2004). Practitioner relationships and quality of care for low-income persons with serious mental illness. Psychiatric Services, 55(5), 555–559. 10.1176/appi.ps.55.5.555 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wills T. A., Shinar O. (2000). Measuring perceived and received social support. In Cohen S., Underwood L. G., Gottlieb B. H. (Eds.), Social support measurement and intervention: A guide for health and social scientists (pp. 86–135). Oxford University Press. 10.1093/med:psych/9780195126709.003.0004 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Wyder M., Bland R. (2014). The recovery framework as a way of understanding families’ responses to mental illness: Balancing different needs and recovery journeys. Australian Social Work, 67(2), 179–196. 10.1080/0312407X.2013.875580 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Yesufu-Udechuku A., Harrison B., Mayo-Wilson E., Young N., Woodhams P., Shiers D., Kuipers E., Kendall T. (2015). Interventions to improve the experience of caring for people with severe mental illness: Systematic review and meta-analysis. The British Journal of Psychiatry, 206(4), 268–274. 10.1192/bjp.bp.114.147561 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang Y., Wildemuth B. M. (2009). Qualitative analysis of content. In Wildemuth B. (Ed.), Applications of social research methods to questions in information and library science (pp. 308–319). Libraries Unlimited. https://www.ischool.utexas.edu/~yanz/Content_analysis.pdf [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplemental material, sj-pdf-1-qhr-10.1177_10497323211039828 for Caregiver Support in Mental Health Recovery: A Critical Realist Qualitative Research by François Lauzier-Jobin and Janie Houle in Qualitative Health Research