Abstract

Introduction

Stereotyping of nurses still occurs nowadays in Indonesia. Society and healthcare think nursing is a doctor helper service. The public image of a nurse as a doctor's helper is hard to erase. Thus, the nursing development in Indonesia needs to be explored in describing the stereotyping and the nursing conditions in the current situation.

Methods

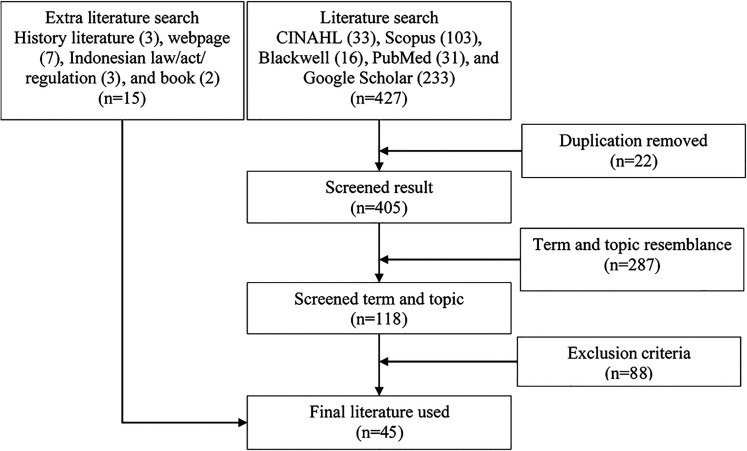

The study used a narrative review with 45 sources analyzed and extracted.

Results

Nursing education has been developed since colonialism. The first time the Netherland Indies built the hospital and they used Babu or a helper as a nurse. The result showed it had a negative impact, which showed as they started to train nurses. They trained male nurses to be Mantri nurses as hulpgeneesheeren (ancillary doctors). After independence, the project HOPE influenced the development of nursing in Indonesia. Indonesian nurses focused on technical aspects and added the nursing process to the education curricula in 1986. However, nurses’ practice culture did not change for a long time because of a lack of research and literature being evaluated during 1990–2010. Indonesia nursing started to increase the education, practice, and research afterward, with specifically the declaration of the Indonesian Nursing Act. It brought nurses into the professionalism of healthcare which the Indonesian government recognized. Then, nurses have faced new problems, including practice and education gaps.

Conclusion

The development of nurses will increase autonomy and dignity. Increasing education curricula, practice competency, and research impact will change the perspective of society with the support of recognition and education from the nursing organization. In addition, the nursing organization has an essential role in nursing development in each country.

Keywords: Delivery of health care, nursing education, professionalism, stereotyping

Background

In developed countries, they know that nurses have a crucial role in enhancing health service. It can be seen that nurses lead the patient care and are innovators and change agents (Anderson et al., 2018). The study in Asian countries, including Iran, Thailand, and the Philippines, showed nurses have autonomy for treating their patients, including being involved in decision-making and patient therapy. Their independence would positively impact the patient and nurse outcome (Labrague et al., 2019; Mousavi et al., 2019; Thepsiri et al., 2020). In contrast, the condition is quite different in Indonesia. Nurses working inwardly felt that they could not provide effective treatment due to several organizational structural and cultural factors (Mediani et al., 2017). The nurse expressed their feelings of powerless, lack of managerial support, and autonomy.

Indonesian nurses have subaltern positions to mimic colonialists’ demands. Nurses, as the name implies, assist doctors in treating patients and sick people. People believe that nurses serve physicians. Because of this picture, public-facing nurses are discredited. Nursing character formation affects the entire nursing profession. Nurses perceive that they are powerless and marginalized. The nurse's goal, in this case, is not to improve the health of patients, but to aid doctors (Sciortino, 1995). A nurse's job is to care for patients as dictated by a doctor's orders. As a result, these stereotypes persist. Eleven doctors, three nurses, and one pharmacist repeated various stereotypes. The nurse provided a patient history and followed the doctor's orders (Darmayani et al., 2020). In addition, patients ignore nurses’ lack of dignity and status. Thus, stereotyping reduces nurses’ autonomy (Juanamasta et al., 2018).

Probably, this phenomenon is still ongoing today. Nursing development will be impeded due to this stereotype. It is always challenging to change an internalized culture. It starts with nurses valuing and accepting their profession. Obviously, nurses hope the acknowledgment is more than talk. However, nursing education has only focused on creating nurses’ to perform well for practicing, which constructed their incapacity for facing public mediation. As a result, nurses cannot demonstrate their essential role in healthcare and the community (Arini & Juanamasta, 2020; Nuryani et al., 2020).

This stereotyping condition dictates the paradigm in which nurses are identified as connected to doctors. Thus, a doctor is allowed to control a nurse's activities with the patient. A nurse is a submissive extension of a doctor's arm. This condition is commonly seen in health services in hospitals. This could be one of the reasons why the doctor-nurse-patient collaboration system is not operating correctly.

Therefore, this article needs to explain and encourage nurses by describing nurses’ development from colonialism till nowadays. This article aimed to deeply explore nursing development in Indonesia from the perspective education, practice, and research. This would benefit readers about how long nurses have been developed, the problems nurses have faced, and what potentially occurred. Besides, nurses need to be aware of this challenge of nurses and the nursing organization and the strategy should be prepared.

Method

Design

The lack of resources and appraisal from the former study that explored nursing development in Indonesia was an excuse for using the narrative method. Moreover, the question's nature was broad and explorative rather than seeking to answer a specific question.

This study used the narrative review method by Ferrari (2015). The process includes defining the objectives and scope, literature search, discussion and summary of key concepts, and conclusion.

Search Strategy

CINAHL, Scopus, PubMed, Blackwell, Google Scholar, Sinta, Ministry of Research and Technology of Indonesia, Ministry of Health of Indonesia, and Lontar UI databases were used without limitations. The search strategy used several keywords in English and Bahasa. Keywords in English were “nurse,” “development,” and “Indonesia,” and then keywords in Bahasa were “perkembangan,” “keperawatan,” and “Indonesia.” We used a boolean search strategy using the operator AND.

Inclusion and Exclusion Criteria

This study's inclusion criteria were any research methods (review, quantitative and qualitative), published and unpublished articles, theses and dissertations, written in English or Indonesian, with full-text access. The exclusion criteria was the outcome of the study did not explain nursing related to education, practice, and research in Indonesia. The exclusion criteria of selection included letters to editors and commentaries.

Screening

All of the authors did the screening. First, the researcher screened by checking for the same article and topic resemblance. Then, the title was screened by using a minimum of one term of “nurse” or “development” or “Indonesia” or “nurse development Indonesia” or “perkembangan” or “perawat” or “perkembangan perawat Indonesia” The final screening was done using the exclusion criteria. There were 45 full-text articles out of 118 articles selected, which matched the inclusion criteria, including official webpage, dissertation, review, scholarly paper, book, report, law, and research articles.

Data Extraction and Analyzes

The selected literature came from broad and different types of sources. Thematic analysis was chosen because of its accessibility and flexibility (Braun & Clarke, 2012). A deductive approach was used to analyze. Data were retrieved from those articles to provide a clear understanding of nursing development in Indonesia from education, practice, and research perspectives. Then, the texts were re-read to ensure something extraneous to the critical concept was discarded. The remainder were re-assessed, and the findings were analyzed and interpreted, referring to the objective that demonstrated this study's significance (Ferrari, 2015).

Results

Nursing development in Indonesia was divided into three eras, including Colonialism, After Independence, and Nursing Act. Those times were chosen due to their significant impact on nursing education, practice, and research.

Colonialism

The development of Indonesian nursing could not be separated from the history of the nation's colonization by Britain, Netherlands, and Japan. In 1799, Binnen Hospital was established in Jakarta for the first time, but nurses only served the sick, specifically for Dutch staff and soldiers. Nursing in Indonesia grew over both periods of Britain colonialism. Under the command of Sir Thomas Stamford Bingley Raffles, health belonged to the whole human being, including the treatment of prisoners, focusing on the treatment of smallpox and mental health problems. During 1816–1942, Indonesia was re-located (or re-colonized) under the power of the Netherlands. The Netherlands started to build some hospitals, especially in Jakarta, such as Stadsverband Hospital (currently known as dr. Cipto Mangunkusomu National Central General Hospital at Salemba).

The Netherland Indies (NI) started to educate nurses due to the limitation of the number of nursing applicants, which realized 1900 (Zondervan, 2016). The NI provided three years of education for nurses with theory and practice. Then, they would become the Dutch-Indies-certified nurses if they could pass the diploma exam, and they were well-known as Mantri-nurse diploma 1st class (Sweet & Hawkins, 2014; Zondervan, 2016). Mantri nurse was taught laboratory and pharmacy work after practicing for two years and passing the exam to practice it. They were authorized to use their skills and knowledge as they saw fit, administering basic first aid for most common illnesses or operating a ward or outpatient clinic. Male nurses only did this. The common diseases could be diagnosed and treated in the outpatient department, while the more complex cases were referred (Sweet & Hawkins, 2014; Zondervan, 2016).

Nevertheless, some hospitals only trained the nurse for one year, which might be related to the demand of nurses and the limitation of European nurses (Sweet & Hawkins, 2014). In 1930, 866 Indonesian and 212 European nurses were recorded (Sweet & Hawkins, 2014).

They were trained to become a nurse through an apprenticeship education oriented to disease and its treatment. Since then, various paramedic specializations have been developed, including education to become a smallpox nurse, European-certified nurse, Dutch-Indies-certified nurse and paramedic, and malaria education, paramedic (Lestari, 2014a). During the period of 1942–1945, under the control of the Japanese, nursing was not considered (Budiono, 2016; Casman et al., 2020).

After Independence

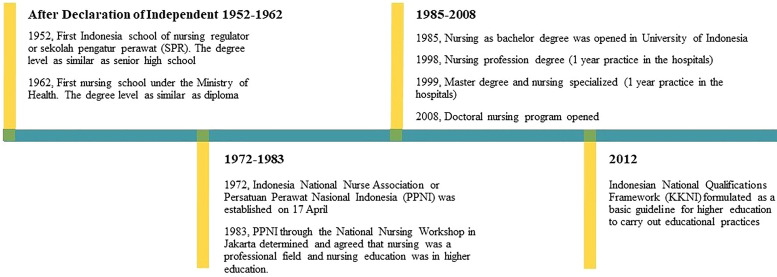

Indonesian nursing education started in the 1800s at a hospital in Batavia, known as the PGI (Persatuan Gereja-gereja di Indonesia or Indonesian Church Council) Cikini Hospital Jakarta. As shown in Figure 2, nursing education developed in 1952 after the independence of Indonesia. The School of Nursing Regulator or Sekolah Pengatur Perawat (SPR) was established at Tantja Rhinos Bandung Hospital (Currently known as Hasan Sadikin Central General Hospital), and SPR later changed its name into the School of Nursing Health or Sekolah Perawat Kesehatan (SPK). SPK was equivalent to Senior High School that took three years to graduate.

Figure 2.

Timeline of nursing education source: Casman et al. (2020); (Lestari, 2014a).

Figure 1.

Literature search diagram flow.

In 1960, Sukarno, the President of Indonesia, established cooperation with John F. Kennedy, the United States president (US). US and private sector businesses established an international health care organization called SS HOPE (Health Opportunities for People Everywhere), known as Project HOPE. SS HOPE trained local health care professionals and provided medical care to people in need around the globe. The first project HOPE was established in Indonesia to teach the latest skills and techniques in America to Indonesian doctors, nurses, and technicians (Studies, 2013). The voyage of project HOPE lasted for eight months throughout Indonesia, and thirty Indonesian nurses were included in it. Those nurses learned from the American nurses, and then they taught their fellow nurses on the island they were visiting about American procedures and techniques.

In 1962, the Academy of Nursing Education was established at the Centraal Burgerlijke Ziekenhuis or CBZ (as a replacement for Stadsverband Hospital and medical school of School Tal Opleiding Van Indische Artsen or Stovia) with the level of a degree similar to a diploma (Casman et al., 2020; Dinas Komunikasi, 2017; Lestari, 2014a, 2014b).

With the development of INNA in 1972, nurses realized the importance of belonging to professional organizations. Then, nursing was recognized as a profession with higher education in the early 1980s, which resulted in the development of nursing practice becoming better since then. The professional nurse is for those with a Diploma III Nursing background. This program produced general nurses with a sufficient and solid scientific foundation for professional nursing (Budiono, 2016; Casman et al., 2020; Lestari, 2014a, 2014b).

However, there was a lack of full-text source-related nursing education curricula before 1988. One study found a distinction between nurses who graduated from nursing school before 1988 and those who graduated in 1988 or later (Kuntjoro, 1996). Until 1988, the school's curricula emphasized practical nursing skills over the nursing process. The nursing process was first taught to first-year students in 1986. Nurses who graduated before 1988 had a limited understanding of the nursing process. Some supplemental training programs were run, but not all pre-1988 nurses were reached. However, many hospitals did not yet allow nurses to practice. Physicians were uncertain about nurses’ ability to practice independent nursing care, and many believed that they should make patient care decisions under a physician's order (Kuntjoro, 1996). In addition, Strength and Cagle (1999) found nursing education in Indonesia was more likely technical than in America.

Nursing education was well-developed during 1985–2008. The University of Indonesia opened a bachelor's degree of a nurse, profession of nurse, master's degree of a nurse, nurse specialist, and doctoral's degree of a nurse. Meanwhile, several studies found the shortage of qualified nurses in clinical practice, no central registration of nurses, no formal job description, no performance assessments, and curricula competency-based was needed (Hennessy et al., 2006b; Wanda, 2007). Moreover, there has been little published research conducted on nursing practice in Indonesia, although that which has been done has consistently shown that there are significant deficits in nurses’ clinical performance (Brown et al., 2013; Hennessy et al., 2006a; Shields & Hartati, 2003). Other studies also found this at the end of 2009 (Brown & Hamlin, 2011; Hamlin & Brown, 2011). Those studies found that nursing care was based on routine and ritual. There was very little evidence of the application of clinical judgment, as well as there was neither the means for identifying weaknesses in clinical practice nor any systematic method for improving clinical performance.

The routine and daily ritual nurses could not separate from the limitation of the literature, source, and information due to few media. Based on the literature, the online full-text information related to nursing was founded in the 1990s. In 1997, the University of Indonesia established the scientific nursing journal called “Jurnal Keperawatan Indonesia,” or Indonesia Nursing Journal, which helps share information (Indonesia, 2021). In the 2000s, the University of Airlangga and the University of Diponegoro established other journals in 2006 and 2007, and those are “Jurnal Ners” and “Nurse Media Journal of Nursing” (Airlangga & Association, 2021; Nursing, 2021). Technology information, like the internet, helps the research information to spread. In addition, Higher Education Act No.12 in the year 2012 required that research results be distributed by scientific publication (Indonesia, 2012). Those regulations have helped nursing research development shown by the Indonesia data of publications 1997–2012 were 337 publications and 2013–2020 were 2,945 publications (Innovation, 2021).

Nursing Act

Overlapping in gray areas for various types and levels of nurses and other health professions is often difficult to avoid in practice, especially in emergencies and limited personnel in remote areas. In the case of a problem arising, the sole responsibility is borne by the nurse. This is a severe issue that threatens the nursing profession. Another issue Larenggam (2013) found was practice violations, such as not having an RN certificate or legal letter to practice in the healthcare facilities. The researcher found an inappropriate governance system caused the problem.

INNA and the Indonesian Government resolved the problem with a clear legislation policy so that Nursing Act No.38 in 2014 was issued (Indonesia, 2014). This regulation helped nursing education, practice, and research. Other rules have been developed to support the Nursing Act (M. o. H. o. Indonesia, 2019). RNs must engage in nursing education for four years. Then, nurses have to take competency tests after finishing the nursing profession in two semesters or one year to receive a Nursing Certificate. Besides, an associate of a nurse or vocational nurse takes education for three years and then can take the examination (Indonesia, 2014; Suba & Scruth, 2015).

Nurse Specialist can be achieved in two-ways, from bachelor RNs or master graduates. They should take clinical residency for three semesters based on their specialty area. It is expected that the nursing specialist graduate will take a consultation, supervisor, and preceptorship role. Moreover, nurse specialist is fervently involved in developing the profession based on their expertise (Lestari, 2014b; Suba & Scruth, 2015).

INNA has been trying to improve the standard of nursing education in Indonesia by establishing the Association of Indonesian Nurses Education Center (AINEC) to guide bachelor and nurse professional institutions of higher education, which was formed in 2010 (Indonesia, 2011). Besides, the Association of Nurses Vocational Education Indonesia or Asosiasi Institusi Pendidikan Vokasi Keperawatan Indonesia (AIPViKI) for vocational education institutions was formed later in the year 2011 (Indonesia, 2019). Those organizations have prepared the national standard of curriculum and competency exam since 2013. Nurses can pass the test if their final score is above the national standard, and then the National Nursing Council will issue the certificate. The certificate will be valid for five years (Indonesia, 2014; Suba & Scruth, 2015). Candidates for international nurse practice in Indonesia must take an examination. A foreign citizen with nursing credentials can work in Indonesia for 5 years.

Current Nursing Condition

In the recapitulation of the Health Human Resources Development and Empowerment Agency in 2021, there are a total of 460,267 nurses in Indonesia (BPPSDMK, 2020), and the demographics can be seen in Table 1.

Table 1.

Nursing Demographics Data Source: (BPPSDMK, 2020).

| Category | Nurse |

|---|---|

| Number of the nurses in the province | |

| Top three | |

| East Java | 58,218 |

| West Java | 55,634 |

| Central Java | 53,710 |

| Bottom three | |

| North Maluku | 2,670 |

| Gorontalo | 2,590 |

| North Kalimantan | 2,310 |

| Nurse ratio per 100,000 population | |

| Top three | |

| Banten | 107.8 |

| West Java | 114.3 |

| Riau | 140.2 |

| Bottom three | |

| Maluku | 316.7 |

| North Kalimantan | 322.4 |

| West Papua | 368.3 |

| Nurses Working in Healthcare Facility | |

| Hospitals | 65.37% |

| Public health centers | 31.09% |

| Others: Disadvantaged, frontier, and outermost areas (Nusantara Sehat) | 3.54% |

| Education of nurses | |

| Specialist | 5.64% |

| Bachelor Degree with Ns. | 18.49% |

| Diploma III and Bachelor without Ns. | 68.39% |

| Nursing Assistant (SPK) | 4.88% |

| Not identified | 2.6% |

Competency tests are carried out three times a year, except in 2020, when it was only carried out twice due to the pandemic disaster at the beginning of the year (Aungsuroch et al., 2020). Based on a Ministry of Education and Culture report, the graduation rate for nurses in 2018 in the first period was 54.47%, the second period was 50.70%, and the third period was 63.23%. In 2019 it showed 50.90% first period, 53.03% second period, and 68.19% third period. In 2020 it showed second and third periods respectively 47.23% and 58.43% (M. o. E. a. C. o. Indonesia, 2021).

Discussion

The development of nursing in Indonesia adopted nursing practice from Europe, where the nursing profession was born because of humanitarian assistance, such as nuns. They focused on taking care of the patients based on charity. During the 18–20th century, there were many infectious diseases and plagues in Indonesia, and nurses were trained based on those diseases. However, the results showed that was not appropriate care. In the later 19th century, The Netherland Indies (NI) started to educate nurses and they were well-known Mantri-nurse. Mantri nurses were needed because of a lack of doctors and worked under European physicians. We assume, this development was recollected, which constructed the stereotyping of nurse as doctor helper. It has continued until nowadays.

After the independence of Indonesia, they was not a significant change for nursing in Indonesia. The revolution of nursing in Indonesia was initiated after the HOPE project came to Indonesia. One year after the project, the Department of Health refined nursing education into a one-year diploma, and INNA was established ten years afterward. Authors recognized that nursing from the European style into the US style was influenced by the project HOPE. Thus, there has been a collaboration between the countries in healthcare education since then.

Regarding the project HOPE, Indonesian nurses developed their education for three years which was equal to senior high school. Then, INNA struggled to increase the nurse education status to become higher education with three-year diploma which was well-developed until 2008 when the first education of Nursing Doctorate was established. However, the nursing development could not be clearly explored because of lack of full-text reported from 1950 to 1990. Besides, the Mantri nurse was still there because of the lack of doctors in the rural area. Then, there was no change in the nursing education curriculum. This condition emphasizes nurses as doctor helpers, because they technically used similar guidance as when the Mantri nurses were established.

After 1990, two studies found nursing education curricula in Indonesia focussed on technical aspects (Kuntjoro, 1996; Strength & Cagle, 1999), and the nursing process was added into the curricula in 1986. We consider nurses started to leave Mantri nurse identity after implementation of nursing process in education and practice. Nursing process pointed the identity to what nurses should do for taking care of patients.

However, the practice culture in Indonesia constrains a nurse to do ritual and routine daily care. Besides, other practical issues arose, including grey area practice, registration license, conflict with another healthcare profession, and low quality of nursing care (Brown et al., 2013; Larenggam, 2013). The need for competency-based curricula to increase nurses’ performance and quality of nursing care in practical areas changed nurse education curricula (Edwards, 2012; Wanda, 2007).

INNA and the government tried to solve the problems by establishing the Nursing Act. Nursing assignments, registration, practice license, and legality are clearly stated in the Nursing Law and its derivative regulations. In addition, AIPNI and AIPViKI control the standard of curriculum and the competency test to meet the minimum standard of the national nurses. New problems that emerged afterward were the ability of hospitals to implement these regulations, the discipline of nurses in implementing them, and the ability of INNA to collaborate with related health organizations and the government.

The most apparent problem is related to the distribution of the nursing practice, which is still concentrated as much as 59.41% in Central Java, West Java, East Java, Jakarta, North, and South Sumatra, South Sulawesi, Aceh, and Banten. The government tries to deploy health workers through the Nusantara Sehat program. The Nusantara Sehat program, through the placement of team-based health workers, was carried out based on the results of a study on the distribution of health workers to strengthen primary health services by increasing access and quality of essential health services. However, only 3.54% joined the program. It also requires an organizational role in deploying nursing personnel (BPPSDMK, 2020).

INNA needs to give direction to nurses, so they can fulfill the shortage of personnel in remote and rural areas, considering Indonesia is an archipelago country. In addition, the government needs to create a policy to give extra facilities or incentives to attract the nurse to work in rural and remote areas (Efendi et al., 2018), because the nurse prefers to work with those factors (Efendi et al., 2021). The preparation of nursing personnel from providing workplace information and monitoring practice certificates to protect nurses needs to be adequately considered. In addition, organizations need to strictly carry out nursing data collection every year to monitor the licensing of nursing practice to prevent problems in taking action.

Standardizing professional nurses with a minimum of a bachelor's degree with professional education in nursing is only 24.13% fulfilled (BPPSDMK, 2020). This shows the great challenge of nursing in developing the profession towards skilled nursing (BPPSDMK, 2020). The limitation level of education seems related to the nursing autonomy in clinical practice. It creates an opportunity for other healthcare providers to look down on nurses. Several studies found that nurses feel dissatisfied with their autonomy (Asmirajanti et al., 2019; Ibrahim, 2017; Trisyani & Windsor, 2019). Moreover, nurses have leadership barriers in the organization's structure and hierarchy, making them unable to speak up and become followers (Wardani & Ryan, 2019).

Another nursing education issue, the competency test result data, shows that the annual average failure rate is still above 40%. This problem caused nurses who do not pass to be unemployed or move to other or non-health jobs (Casman et al., 2020). The issue of competency testing is the responsibility of AIPNI, AIPViKI, and nursing education institutions, concerning whether the problems come from the curriculum or learning system. Besides, the competency problem has a critical impact on the gap of clinical practice, including performance, career ladder, and autonomy (Fauziah et al., 2020; Lumbantobing et al., 2019; Sandehang et al., 2019). Universities or colleges of nursing need to prepare specific methods of increasing their quality of graduates. Techniques such as question training, peer learning, deepening of the material, and other innovative online learning methods need to be done to improve the competence of nursing students and nurses (Bahari et al., 2021; Hariyati et al., 2019; Hutapea et al., 2021; Nelwati & Chong, 2019; Riantini et al., 2019).

Nursing research has increased with the development of nursing in Indonesia. Critical thoughts from educators and practitioners are increasingly emerging. The gap between theory and practice and curriculum and competency needs to be regularly evaluated (Lusmilasari et al., 2020). Then, hospitals can apply evidence-based practices to improve the quality of hospital services. The INNA also supports the implementation of research by providing research grants annually. In addition, other sources of research grants come from the Ministry of Education and Culture and Educational Institutions. Moreover, the obligation to publish publications for nurses is to support careers and research quality.

Implication for Practice

The nursing development in Indonesia brings to the nurse the shape of professional caring spirit from Europe, which was developed following the United States. Nurses should know about their history and why the stereotyping of doctor helpers arose. That would give a depth of understanding of nursing stereotype and then create a way to solve that which will impact autonomy. Besides, it might be related to the competency of nurses. The competency is related to nursing education and training. Nursing organizations and senior nurses should encourage their young nurses or student nurses to continuing professional education.

In addition, nursing organizations, specifically INNA, have a big responsibility for the legislation of the nursing profession to increase the visibility and recognition of the work by society. Nursing organizations across the world need to encourage, protect, and improve the public relations image of their job in their countries. This is an important message for nursing in Indonesia.

INNA needs to encourage its members, including facilitate, advocate, distribute, and develop them. Those are aimed to strengthen the nursing organization from the inside, which would increase their public image. This would refine the nursing image from a long time ago. Moreover, this would help nurses think about their profession, and what they want to do in the future, and whether they have intention to stay in the nursing profession or leave it. However, there has been no study in Indonesia related to nursing intention to stay or leave. Further study needs to explore the relationship between nursing organizations and nurses to stay with the profession.

Limitation

This study could not explain a broad topic, including education, practice, and research. A specific review might be needed to explore the urgent issues. Another limitation was deductive thematic analysis. The researchers analyzed this concept and idea, and other researchers might find different things when reviewing. Besides, the limitation of the full-text literature before the 1990s resulted in making a lot of assumptions.

Conclusion

This article wanted to emphasize how nursing has developed in Indonesia. Nursing started since colonization. The Mantri nurse was the pioneer of the stereotyping. Even though nursing practice developed after the HOPE project with the US nursing system, Mantri nurse still existed. Thus, the stereotype has grown over decades.

Meanwhile, nursing practice based on the task has changed into process-based nursing. It makes nurse have a different role with other healthcare professionals. Moreover, the development has increased rapidly after issuing of the Indonesia Nursing Act in 2014. The development practice and education could not be separate. Nursing education curricula developed from technical orientation without nursing process to be competency-based nursing process, and it is not limited to those curricula in the future.

Nursing research in Indonesia has developed well over time. However, it is still behind if compared with another country. Education and practice gap requires more attention, including standard, technique, knowledge, or system of education and training.

Besides, nursing organizations, specifically INNA, have essential roles in managing nurses and motivating student nurses. Nowadays, several issues that need to be clear are nursing autonomy related to stereotype and competency, workforce distribution, nursing license monitoring, and competency gap in education and practice. Thus, the development of nurses will increase independence and dignity. Increasing competence, critical thinking in practice, and caring for patients will change the perspective of society with the support of better public imaging from the nursing organizations.

Supplemental Material

Supplemental material, sj-docx-1-son-10.1177_23779608211051467 for Nursing Development in Indonesia: Colonialism, After Independence and Nursing act by I Gede Juanamasta and Abdulkareem S. Iblasi, Yupin Aungsuroch, Jintana Yunibhand in SAGE Open Nursing

Acknowledgments

None

Footnotes

Conflict of Interests: We declare that there is no conflict of interest

Ethical Statement: We declare that an ethical statement is not applicable as this manuscript does not involve human or animal research.

Author Contribution: I Gede Juanamasta (IGJ), Abdulkareem S. Iblasi (ASI), Yupin Aungsuroch (YA), and Jintana Yunibhand (JY) made substantial contributions to conception and design, or acquisition of data, or analysis and interpretation of data. IGJ, ASI, YA, and JY involved in drafting the manuscript or revising it critically for important intellectual content. IGJ, ASI, YA, and JY gave final approval of the version to be published. Each author has participated sufficiently in the work to take public responsibility for appropriate portions of the content.

Declaration of Conflicting Interests: The author(s) declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Funding: The authors received no financial support for the research, authorship and/or publication of this article.

ORCID iD: Abdulkareem S. Iblasi https://orcid.org/0000-0003-3360-1462

I Gede Juanamasta https://orcid.org/0000-0002-5445-7861

Supplemental material: Supplemental material for this article is available online.

References

- Airlangga F. O. N. U., Association I. N. N. (2021). Jurnal Ners. Pusat Pengembangan Jurnal dan Publikasi Ilmiah Universitas Airlangga. Retrieved 3 March from https://e-journal.unair.ac.id/JNERS/issue/archive.

- Anderson V. L., Johnston A. N. B., Massey D., Bamford-Wade A. (2018). Impact of MAGNET hospital designation on nursing culture: An integrative review. Contemporary Nurse, 54(4-5), 483–510. 10.1080/10376178.2018.1507677 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arini T., Juanamasta I. G. (2020). The role of hospital management to enhance nursing Job satisfaction. INDONESIAN NURSING JOURNAL OF EDUCATION AND CLINIC (INJEC), 5(1), 82–86. 10.24990/injec.v5i1.295 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Asmirajanti M., Hamid A. Y. S., Hariyati R. T. S. (2019). Nursing care activities based on documentation. Bmc Nursing, 18(S1), 32. 10.1186/s12912-019-0352-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aungsuroch Y., Juanamasta I. G., Gunawan J. (2020). Experiences of patients With coronavirus in the COVID-19 pandemic Era in Indonesia. Asian Journal for Public Opinion Research, 8(3), 16. 10.15206/ajpor.2020.8.3.377 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Bahari K., Talosig A. T., Pizarro J. B. (2021). Nursing technologies creativity as an expression of caring: A grounded theory study. Global Qualitative Nursing Research, 8, 2333393621997397. 10.1177/2333393621997397 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- BPPSDMK (2020). Data Tenaga Keperawatan yang didayagunakan di Fasilitas Pelayanan Kesehatan (Fasyankes) di Indonesia. Kementerian Kesehatan. Retrieved 13 July from http://bppsdmk.kemkes.go.id/info_sdmk/info/index?rumpun=103.

- Braun V., Clarke V. (2012). Thematic analysis. In APA handbook of research methods in psychology, Vol 2: Research designs: Quantitative, qualitative, neuropsychological, and biological. (pp. 57-71). American Psychological Association. 10.1037/13620-004. [DOI]

- Brown D., Hamlin L. (2011). Changing perioperative practice in an Indonesian hospital: Part II of II. Aorn Journal, 94(5), 488–497. 10.1016/j.aorn.2011.08.006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown D., Rickard G., Mustriwati K., Seiler J. (2013). International partnerships and the development of a sister hospital programme. International Nursing Review, 60(1), 45–51. 10.1111/j.1466-7657.2012.01032.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Budiono B. (2016). Konsep Ajar Keperawatan. Badan Pengembangan dan Pemberdayaan Sumber Daya Manusia Kesehatan. http://bppsdmk.kemkes.go.id/pusdiksdmk/wp-content/uploads/2017/08/Konsep-dasar-keperawatan-Komprehensif.pdf.

- Casman C., Ahadi Pradana A., Edianto E., Abdul Rahman L. O. (2020). Kaleidoskop menuju seperempat abad pendidikan keperawatan di Indonesia. Jurnal Endurance, 5(1), 115–125. 10.22216/jen.v5i1.4291 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Darmayani S., Findyartini A., Widiasih N., Soemantri D. (2020). Stereotypes among health professions in Indonesia: An explorative study. Korean Journal of Medical Education, 32(4), 329–341. 10.3946/kjme.2020.180 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dinas Komunikasi I. d. S. P. D. J. (2017). Centraal Burgerlijke Ziekenhuis (CBZ). Dinas Komunikasi, Informatika dan Statistik Pemprov DKI Jakarta. Retrieved 3 March from https://jakarta.go.id/artikel/konten/538/centraal-burgerlijke-ziekenhuis-cbz.

- Edwards J. E. (2012). The lived experience of Indonesian nursing faculty participating in a nursing education reform based on the 2009 World Health Organization Global Standards University of Texas ]. Tyler. http://hdl.handle.net/10950/102.

- Efendi F., Chen C.-M., Kurniati A., Nursalam N., Yusuf A. (2018). The situational analysis of nursing education And workforce in Indonesia. The Malaysian Journal of Nursing, 9(4), 10. https://ejournal.lucp.net/index.php/mjn/article/view/338. [Google Scholar]

- Efendi F., Oda H., Kurniati A., Hadjo S. S., Nadatien I., Ritonga I. L. (2021). Determinants of nursing students’ intention to migrate overseas to work and implications for sustainability: The case of Indonesian students. Nursing & Health Sciences, 23(1), 103–112. 10.1111/nhs.12757 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fauziah F., Purba J. M., Tumanggor R. D., Yuswardi Y., Wardani E. (2020). Factors affecting the implementation of career path and mentor method Among hospital based clinical nurses: A study in Indonesia. International Journal of Nursing Education, 12(4), 6. 10.37506/ijone.v12i4.11218 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ferrari R. (2015). Writing narrative style literature reviews. Medical Writing, 24(4), 230–235. 10.1179/2047480615z.000000000329 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hamlin L., Brown D. (2011). Changing perioperative practice in an Indonesian hospital: Part I of II. Aorn Journal, 94(4), 403–408. 10.1016/j.aorn.2011.05.012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hariyati R. T. S., Handiyani H., Utomo B., Rahmi S. F., Djadjuli H. (2019). Nurses’ perception and nursing satisfaction using “The corner competency system”. Enfermería Clínica, 29(Suppl 2), 659–664. 10.1016/j.enfcli.2019.04.101 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hennessy D., Hicks C., Hilan A., Kawonal Y. (2006a). A methodology for assessing the professional development needs of nurses and midwives in Indonesia: Paper 1 of 3. Human Resources For Health, 4(1), 8. 10.1186/1478-4491-4-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hennessy D., Hicks C., Hilan A., Kawonal Y. (2006b). The training and development needs of nurses in Indonesia: Paper 3 of 3. Human Resources For Health, 4(1), 10. 10.1186/1478-4491-4-10 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hutapea L. M. N., Balthip K., Chunuan S. (2021). Development and evaluation of a preparation model for the Indonesian nursing licensure examination: A participatory action research. Nurse Education Today, 106, 104952. 10.1016/j.nedt.2021.104952 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ibrahim K. (2017). The Use of Esthetics in Nursing Practice and Education in the 21st Century: The Context of Indonesia. The 2017 International Nursing Conference on Ethics, Esthetics, and Empirics in Nursing: Driving Forces for Better Health, Songkhla, Thailand. https://he02.tcithaijo.org/index.php/nur-psu/article/download/106582/84373/

- Indonesia A. I. P. N. (2011). Sejarah Perkembangan AIPNI. Asosiasi Institusi Pendidikan Ners Indonesia. Retrieved 21 February from http://aipni-ainec.com/id/article_view/201505010048/sejarah-perkembangan-aipni.html.

- Indonesia A. I. P. V. K. (2019). Kurikulum pendidikan D III Keperawatan Indonesia. Asosiasi Institusi Pendidikan Vokasi Keperawatan Indonesia. Retrieved 21 February from http://aipviki.org/berita-kurikulum-d3-keperawatan-update-2018.html.

- Indonesia F. o. N. U. (2021). Jurnal Keperawatan Indonesia. Univeritas Indonesia. Retrieved 3 March from http://jki.ui.ac.id/index.php/jki/issue/archive.

- Indonesia Higher Education Act no.12 (2012).

- Indonesia M. o. E. a. C. o. (2021). Data Statistik Uji Kompetensi Ners [Statistic Data of Ners Competency Exam]. Retrieved 21 February from http://ukners.kemdikbud.go.id/pages/statistik_lulus.

- Indonesia Minister of Health Regulation No. 26 (2019).

- Indonesia Nursing Act No. 38 (2014).

- Innovation N. A. f. R. a. (2021). GARUDA: Garba Rujukan Digital. Ministry of Research and Technology. Retrieved 3 March from https://garuda.ristekbrin.go.id/documents?select=title&q=perawat&pub=.

- Juanamasta I. G., Kusnanto K., Yuwono S. R. (2018). Improving Nurse Productivity Through Professionalism Self-Concept. Proceedings of the 9th International Nursing Conference - INC, Airlangga University, Surabaya. 10.5220/0008321401160120 [DOI]

- Kuntjoro T. (1996). Nurse performance and its determinant factors in public and private hospitals in Indonesia (Publication Number 9700528) University of Hawai'i at Manoa]. Honolulu.

- Labrague L. J., McEnroe-Petitte D. M., Tsaras K. (2019). Predictors and outcomes of nurse professional autonomy: A cross-sectional study. International Journal of Nursing Practice, 25(1), e12711. 10.1111/ijn.12711 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Larenggam D. N. (2013). Ketentuan hukum sebagai Acuan dalam pelaksanaan praktik perawat universitas hasanuddin]. Makassar. [Google Scholar]

- Lestari T. R. P. (2014a). An analysis On nursing profession In Indonesia. Kajian, 19(1), 18. 10.22212/kajian.v19i1.548 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Lestari T. R. P. (2014b). Pendidikan keperawatan: Upaya menghasilkan tenaga perawat berkualitas. Aspirasi, 5(1), 10. http://jurnal.dpr.go.id/index.php/aspirasi/article/view/452/349 [Google Scholar]

- Lumbantobing V., Yudianto K., Nani A. (2019). Self assessment of Gap competency By clinical nurses level III. Journal of Nursing Care and Biomoleculer, 4(1), 18–27. http://jnc.stikesmaharani.ac.id/index.php/JNC/article/view/135 [Google Scholar]

- Lusmilasari L., Aungsuroch Y., Widyawati W., Sukratul S., Gunawan J., Perdana M. (2020). Nursing research priorities in Indonesia as perceived by nurses. Belitung Nursing Journal, 6(2), 41–46. 10.33546/bnj.1055 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Mediani H. S., Duggan R., Chapman R., Hutton A., Shields L. (2017). An exploration of Indonesian nurses’ perceptions of barriers to paediatric pain management. Journal of Child Health Care, 21(3), 273–282. 10.1177/1367493517715146 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mousavi S. R., Amini K., Ramezani-badr F., Roohani M. (2019). Correlation of happiness and professional autonomy in Iranian nurses. Journal of Research in Nursing, 24(8), 622–632. 10.1177/1744987119877421 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nelwati A. K. L., Chong M. C. (2019). Factors influencing professional values among Indonesian undergraduate nursing students. Nurse Education in Practice, 41, 102648. 10.1016/j.nepr.2019.102648 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nursing D. o. (2021). Nurse Media journal of nursing. Universitas Diponegoro. Retrieved 3 March from https://ejournal.undip.ac.id/index.php/medianers/issue/archive. [Google Scholar]

- Nuryani S. A. N., Wati N. M. N., Juanamasta I. G. (2020). Nursing grand rounds (NGRS) regularly to encourage continuing professional development (CPD) achievement of nurses [original research]. Pakistan Journal of Medical and Health Sciences, 14(4), 3. https://pjmhsonline.com/2020/oct_dec/1616.pdf [Google Scholar]

- Riantini R. E., Tjhin V. U., Kusumastuti D. L. (2019, 7-9 Nov). Mobile Based Learning Development for Improving Quality of Nursing Education in Indonesia 2019 IEEE Conference on Sustainable Utilization and Development in Engineering and Technologies (CSUDET), Penang, Malaysia. 10.1109/CSUDET47057.2019.9214755 [DOI]

- Sandehang P. M., Hariyati R. T. S., Rachmawati I. N. (2019). Nurse career mapping: A qualitative case study of a new hospital. Bmc Nursing, 18(Suppl 1), 31. 10.1186/s12912-019-0353-z [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sciortino R. (1995). Health personnel caught between conflicting worlds: An example from Java. Antropologische Notities, 10. [Google Scholar]

- Shields L., Hartati L. E. (2003). Nursing and health care in Indonesia. Journal of Advanced Nursing, 44(2), 209–216. 10.1046/j.1365-2648.2003.02785.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Strength D., Cagle C. S. (1999). Indonesia: An assessment of the health state, health care delivery system, and nursing education. Journal of Cultural Diversity, 6(2), 6. https://search.proquest.com/docview/219360823/fulltextPDF/C5C8345131D04079PQ/1?accountid=15637. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Studies T. Y. R. o. I. (2013). (Hon. Mention) “Hope Springs Eternal?” Agenda and idealism in the symbolization of the S.S. Hope. Yale International Relations Association. Retrieved 2 March from http://yris.yira.org/essays/965.

- Suba S., Scruth E. A. (2015). A New Era of nursing in Indonesia and a vision for developing the role of the clinical nurse specialist. Clinical Nurse Specialist Cns, 29(5), 255–257. 10.1097/NUR.0000000000000146 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sweet H., Hawkins S. (2014). Colonial caring: A history of colonial and post-colonial nursing. Manchester University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Thepsiri J., Thungjaroenkul P., Nantsupawat A. (2020). Nursing shared governance as perceived by nursesin the private nursing department, maharaj nakorn chiang Mai hospital. Nursing Journal, 47(3), 327–338. https://he02.tci-thaijo.org/index.php/cmunursing/article/view/240449 [Google Scholar]

- Trisyani Y., Windsor C. (2019). Expanding knowledge and roles for authority and practice boundaries of emergency department nurses: A grounded theory study. International Journal of Qualitative Studies on Health and Well-Being, 14(1), 1563429. 10.1080/17482631.2018.1563429 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wanda D. (2007). An investigation of clinical assessment processes od student nurse in Jakarta, Indonesia Australian catholic university]. https://acuresearchbank.acu.edu.au/item/8v368/an-investigation-of-clinical-assessment-processes-of-student-nurses-in-jackarta-indonesia. ACU Research Bank. [Google Scholar]

- Wardani E., Ryan T. (2019). Barriers to nurse leadership in an Indonesian hospital setting. Journal of Nursing Management, 27(3), 671–678. 10.1111/jonm.12728 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zondervan S. (2016). Patients of The colonial state: The rise of a hospital system in the Netherlands indies, 1890-1940. Maastricht University. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplemental material, sj-docx-1-son-10.1177_23779608211051467 for Nursing Development in Indonesia: Colonialism, After Independence and Nursing act by I Gede Juanamasta and Abdulkareem S. Iblasi, Yupin Aungsuroch, Jintana Yunibhand in SAGE Open Nursing