Abstract

Small-cell lung cancer (SCLC) is a devastating subtype of lung cancer with few therapeutic options. Despite the advent of immunotherapy, platinum-based chemotherapy is still the irreplaceable first-line therapy for SCLCs. However, drug resistance will invariably occur in most patients and the outcomes are heterogeneous. Therefore, clinically feasible classification strategies and potential therapeutic targets for overcoming chemotherapy resistance are urgently needed. N6-methyladenosine (m6A) is a novel epigenetic decisive factor that is involved in tumor progression and drug resistance. However, almost nothing is known about m6A modification in SCLC. Here, we assessed 200 SCLC samples from patients who underwent chemotherapy from three different cohorts, including a validation cohort containing 71 cases with qPCR data and an independent cohort containing 79 cases with immunohistochemistry data (quantified as H-score). We systematically characterized the predictive landscape of m6A regulators in SCLC patients following with chemotherapy. Using the LASSO Cox model, we built a seven-regulator-based (ZCCHC4, IGF2BP3, ALKBH5, YTHDF3, METTL5, G3BP1, and RBMX) chemotherapy benefit predictive classifier (m6A score) and subsequently validated the classifier in two other cohorts. Time-dependent ROC and C-index analyses showed that the m6A score to possessed superior predictive power for chemotherapy benefit in comparison with other clinicopathological parameters. A multicohort multivariate analysis revealed that the m6A score is an independent factor that affects survival benefit across multiple cohorts. Our in vitro experimental results revealed that three regulators—ZCCHC4, G3BP1, and RBMX—may serve as promising novel therapeutic targets for overcoming chemoresistance in SCLCs. Our results, for the first time, demonstrate the predictive significance of m6A regulators for chemotherapy benefit, as well as their potential as therapeutic targets for overcoming chemotherapy resistance in SCLC patients. The m6A score was found to be a reliable prognostic tool that may help guide chemotherapy decisions for patients with SCLC.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1186/s13045-021-01173-4.

Keywords: Small-cell lung cancer, m6A regulators, Epigenetic modification, Chemotherapy resistance, Individualized medicine

To the editor

Lung cancer remains the leading cause of cancer-associated mortality [1, 2], while small-cell lung cancer (SCLC) comprises approximately 15% of these cases [3]. SCLC is characterized by poor prognosis with a 5-year survival rate of less than 7% [4]. Despite the advent of immunotherapies, the prognosis for SCLCs remains grim [5]. Chemotherapy is still the irreplaceable first-line therapy [6]. However, drug resistance occurs in most patients [4]. N6-methyladenosine (m6A) is a new epigenetic decisive factor that is related to chemotherapy resistance [7], via a mechanism that involves several regulators [8]. Although multiple epigenetic modifications have been tightly linked to drug resistance in SCLC [9], the role of the m6A modification in SCLC remains elusive.

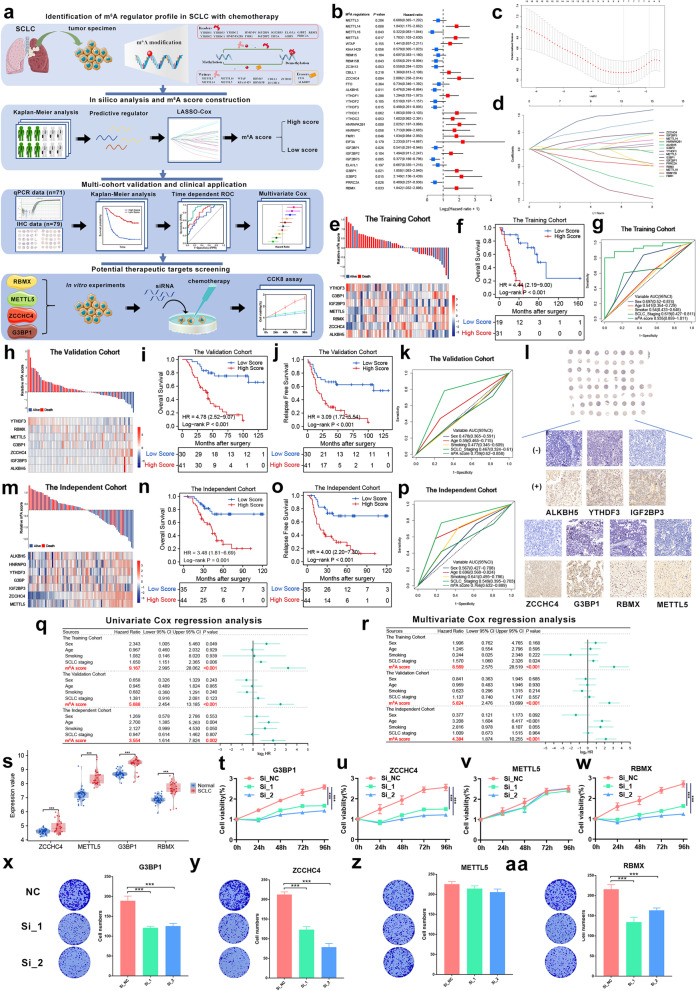

The workflow is displayed in Fig. 1a. In total, 30 regulators were assessed (Additional file 1: Table S1). We determined the survival benefit predictive values of these regulators in patients who underwent adjuvant chemotherapy (ACT). Half of the regulators (15/30) exhibited significant clinical relevance (Fig. 1b, Additional file 2: Fig. S1, Additional file 1: Table S2), indicating that m6A modification may contribute to chemotherapy efficacy. We hypothesized that an m6A regulator-based signature might predict the benefit of ACT. We obtained data for 200 SCLC samples from three cohorts of patients who underwent ACT to construct the m6A score (Additional file 1: Table S3). Considering the collinearity of the data (Additional file 2: Fig. S2), the LASSO Cox model was selected. Seven regulators (ZCCHC4, IGF2BP3, ALKBH5, YTHDF3, METTL5, G3BP1, and RBMX) were identified (Fig. 1c, d) and used to generate m6A scores (Fig. 1e, Additional file 3). Patients with high m6A scores had significantly worse overall survival (OS) (Fig. 1f, P < 0.001). The m6A score showed excellent performance across different years (Additional file 2: Fig. S3a) and better accuracy than other clinicopathological parameters for predicting the OS benefit (Fig. 1g, Additional file 2: Fig. S3b).

Fig. 1.

Identification of m6A regulators as predictive biomarkers and potential therapeutic targets in small-cell lung cancer with chemotherapy. a The work flow of this study. Thirty m6A regulators were selected from several recently published studies. The predictive regulators were filtered out through Kaplan–Meier curve analysis. The m6A score was constructed using the LASSO Cox regression model and the training cohort. The m6A score was validated in two different cohorts with qPCR data and immunohistochemistry data. Finally, the therapeutic potential of several regulators was explored through in vitro experiments. b A forest plot of the optimum cutoff survival analysis of the m6A regulators in SCLC patients from the training cohort who underwent chemotherapy. c The LASSO model was selected to determine the partial likelihood deviance of different numbers of variables, and 100-fold cross-validation was chosen. d Distribution of the LASSO coefficients of 15 significant regulators. e Distribution of the seven regulators comprising the m6A score, the corresponding m6A score, and survival status in the training cohort. f Survival curve of OS for patients from the training cohort. g Time-dependent ROC curves comparing the prognostic accuracy of the m6A score with other clinicopathological parameters at 5 years in the training cohort. h Distribution of the seven regulators comprising the m6A score, the corresponding m6A score, and survival status in the validation cohort with qPCR data. i Survival curve of OS for patients from the validation cohort. j Survival curve of RFS for patients from the validation cohort. k Time-dependent ROC curves comparing the prognostic accuracy of the m6A score with other clinicopathological parameters at 5 years in the validation cohort. l Representative immunohistochemistry images of the seven regulators comprising the m6A score from the tissue microarray; (+) high expression, (−) low expression (40 ×). m Distribution of the seven regulators comprising the m6A score, the corresponding m6A score, and survival status in the independent cohort. n Survival curve of OS for patients from the independent cohort. o Survival curve of RFS for patients from the independent cohort. p Time-dependent ROC curves comparing the prognostic accuracy of the m6A score with other clinicopathological parameters at 5 years in the independent cohort. q Univariate Cox regression analysis of clinicopathological factors and the m6A score for OS in patients across multiple cohorts. r Multivariate Cox regression analysis of clinicopathological factors and the m6A score for OS in patients across multiple cohorts. s Distribution of the four selected regulators in normal lung and SCLC tissues from GSE40275. t, x Knocking down the expression of G3BP1 significantly increased the sensitivity of SCLC cells to cisplatin. u, y Knocking down the expression of ZCCH4 significantly increased the sensitivity of SCLC cells to cisplatin. v, z Knocking down the expression of METTL5 had no effect on the sensitivity of SCLC cells to cisplatin. w, aa Knocking down the expression of RBMX significantly increased the sensitivity of SCLC cells to cisplatin

A set of 70 surgical specimens from patients who underwent ACT (qPCR data) was selected as a validation cohort (Fig. 1h, Additional file 1: Table S4). Similarly, high-score patients had shorter OS (Fig. 1i, P < 0.001) and relapse-free survival (RFS) (Fig. 1j, P < 0.001). The m6A score also performed well at different follow-up times (Additional file 2: Fig. S4a, b) and had an AUC (0.739) and C-index (0.833) that were higher than those of other parameters (Fig. 1k, Additional file 2: Fig. S4c). The m6A score also showed superiority for predicting the RFS benefit (Additional file 2: Fig. S4d, e). Furthermore, the m6A score was also calculated based on the H-scores in an independent cohort containing immunohistochemistry data (n = 79) (Fig. 1l, m). Low-score patients exhibited longer OS (Fig. 1n, P = 0.001) and RFS (Fig. 1o, P < 0.001). The AUCs for OS and RFS (Additional file 2: Fig. S5a, b) indicated that the protein level-based classifier is also a stable predictor. The m6A score also achieved a high AUC of 0.766 (Fig. 1p) and a C-index of 0.756 (Additional file 2: Fig. S5c). The advantage of the m6A score was also confirmed in predicting the RFS (Additional file 2: Fig. S5d, e). Additionally, the m6A score was the only stable and independent factor affecting survival across multiple cohorts (Fig. 1q, r, Additional file 2: Fig. S6, P < 0.001). As far as we know, the m6A score is the first molecular model using a large cohort of SCLCs who underwent chemotherapy. Large-scale analyses of SCLC samples are extremely rare because of the difficulties associated with obtaining tumor specimens within standard clinical settings.

Given that four of the regulators—ZCCHC4, METTL5, G3BP1, and RBMX—that comprised the m6A score were risk factors (coefficient > 0), we investigated their therapeutic potential for overcoming chemotherapy resistance. All four of these regulators were dramatically up-regulated in the SCLC samples (Fig. 1s). In vitro experiments found that knocking down the expression of ZCCHC4, G3BP1, or RBMX significantly increased the sensitivity of SCLC cells to chemotherapeutic drugs. In contrast, down-regulation of METTL5 had no notable influence on drug sensitivity (Fig. 1t–w, x–aa, Additional file 2: Fig. S7). These results suggest that m6A regulators are promising novel therapeutic targets for overcoming chemoresistance.

For the first time, we found that m6A regulators can predict chemotherapy benefit, potentially minimizing the risk of chemotherapy resistance in SCLCs. The m6A score is a reliable prognostic tool for guiding chemotherapy options. Patients with low m6A scores are more likely to benefit from ACT. In contrast, patients with high m6A scores would likely be better served by utilizing other treatment regimens or participating in clinical trials with new strategies, rather than enduring the toxic side effects of chemotherapy that might provide no therapeutic benefit. This in vitro study also indicated that therapeutic interventions targeting m6A regulators may provide patients with enhanced and durable responses.

Supplementary Information

Additional file 1. Supplementary Tables.

Additional file 2. Supplementary Figures.

Additional file 3. Supplementary materials and methods.

Acknowledgements

All authors would like to thank the specimen donors used in this study and research groups for the training cohort and GSE40275. All authors would also like to thank CapitalBio Technology for their kind help.

Abbreviations

- SCLC

Small-cell lung cancer

- m6A

N6-Methyladenosine

- ACT

Adjuvant chemotherapy

- LASSO

Least absolute shrinkage and selection operator

- OS

Overall survival

- AUC

Area under the curve

- RFS

Relapse-free survival

Authors’ contributions

JH, NS, and YZ supervised the project, and designed and led out the experiments of this study. ZZ, CZ and PW conducted the experiments and data analysis. ZZ and CZ prepared all figures and tables. ZZ and CZ drafted the manuscript. ZYY, YL, GZ, QZ, LW, and QX collected clinical samples. All authors reviewed and approved the final manuscript.

Funding

This work was supported by the CAMS Innovation Fund for Medical Sciences (2017-I2M-1-005), the Fundamental Research Funds for the Central Universities (3332018070), and the National Key Basic Research Development Plan (2018YFC1312105).

Availability of data and materials

All data that support the findings of this study are available to researchers on reasonable request.

Declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

This study was approved by the Ethics Committee of the Cancer Hospital of the Chinese Academy of Medical Sciences. Due to retrospective nature of this study, the requirement for informed consent was waived. This work was conducted in compliance with the Declaration of Helsinki.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Zhihui Zhang, Chaoqi Zhang, Zhaoyang Yang and Guochao Zhang contributed equally to this work

Contributor Information

Yi Zhang, Email: yizhang@zzu.edu.cn.

Nan Sun, Email: sunnan@vip.126.com.

Jie He, Email: prof.jiehe@gmail.com.

References

- 1.Sung H, Ferlay J, Siegel RL, Laversanne M, Soerjomataram I, Jemal A, et al. Global Cancer Statistics 2020: GLOBOCAN estimates of incidence and mortality Worldwide for 36 cancers in 185 countries. CA Cancer J Clin. 2021;71:209–249. doi: 10.3322/caac.21660. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Majeed U, Manochakian R, Zhao Y, Lou Y. Targeted therapy in advanced non-small cell lung cancer: current advances and future trends. J Hematol Oncol. 2021;14:108. doi: 10.1186/s13045-021-01121-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Owen DH, Giffin MJ, Bailis JM, Smit MD, Carbone DP, He K. DLL3: an emerging target in small cell lung cancer. J Hematol Oncol. 2019;12:61. doi: 10.1186/s13045-019-0745-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Rudin CM, Brambilla E, Faivre-Finn C, Sage J. Small-cell lung cancer. Nat Rev Dis Primers. 2021;7:3. doi: 10.1038/s41572-020-00235-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Iams WT, Porter J, Horn L. Immunotherapeutic approaches for small-cell lung cancer. Nat Rev Clin Oncol. 2020;17:300–312. doi: 10.1038/s41571-019-0316-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Yang S, Zhang Z, Wang Q. Emerging therapies for small cell lung cancer. J Hematol Oncol. 2019;12:47. doi: 10.1186/s13045-019-0736-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Huang H, Weng H, Chen J. m(6)A modification in coding and non-coding RNAs: roles and therapeutic implications in cancer. Cancer Cell. 2020;37:270–288. doi: 10.1016/j.ccell.2020.02.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Zhao Y, Shi Y, Shen H, Xie W. m(6)A-binding proteins: the emerging crucial performers in epigenetics. J Hematol Oncol. 2020;13:35. doi: 10.1186/s13045-020-00872-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Khan P, Siddiqui JA, Maurya SK, Lakshmanan I, Jain M, Ganti AK, et al. Epigenetic landscape of small cell lung cancer: small image of a giant recalcitrant disease. Semin Cancer Biol. 2020 doi: 10.1016/j.semcancer.2020.11.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Additional file 1. Supplementary Tables.

Additional file 2. Supplementary Figures.

Additional file 3. Supplementary materials and methods.

Data Availability Statement

All data that support the findings of this study are available to researchers on reasonable request.