Abstract

This study aimed to assess the association of severe malaria infection with the ABO blood groups among acute febrile patients at the General Hospital of Rungu, in the Democratic Republic of the Congo. This cross-sectional study was conducted between August and October 2018. Plasmodium falciparum-infected individuals were categorized as severe malaria and uncomplicated malaria. A total of 400 febrile patients were enrolled. The majority (n = 251; 62.8%) was positive P. falciparum in microscopy test, of whom 180 (71.7%) had uncomplicated malaria and 71 (28.3%) severe malaria; 32.3%, 18.3%, 2.8%, and 46.6% were found to be blood group of A, B, AB, and O, respectively. In the multivariate analysis using the logistic regression models, severe malaria was high among patients with A blood group compared to those with O blood group (45.8% vs. 13.7%; adjusted odds ratio: 5.3 [95% confidence interval: 2.7–10.5]; P < 0.001). This survey demonstrates that patients with A blood group had a high susceptibility to severe malaria compared to those with O blood group.

Keywords: ABO blood group, Democratic Republic of the Congo, malaria, Plasmodium falciparum

INTRODUCTION

Malaria continues to claim the lives of more than 435,000 people each year, largely in Africa.[1] Several studies report associations between different infectious diseases and the distribution of the ABO blood groups.[2] Furthermore, a growing body of evidence suggests a correlation between the clinical severity of malaria and the ABO blood group of the patient.[2,3,4,5,6,7,8,9] It is known that the sequestration of parasitized red blood cells (RBCs) in the microcirculation is at the root of neurological complications, respiratory failure, multi-organ failure, and death.[10,11,12,13] This sequestration is generally explained by the mechanism of cytoadherence of parasitized RBCs to endothelial cells, the formation of occlusive intravascular aggregates, the low deformability of parasitized RBCs, and the resetting phenomenon.

There is increasing evidence that parasitized RBCs form rosettes more readily with RBCs of non-O (A, B, or AB) groups than with cells of blood group O. Indeed, the resetting capacity varies among different blood groups;[7] lowest rosette formation is observed in blood O blood group individuals. Several studies have shown that PfEMP1-specific antibodies are less prone to bind to the surface-exposed PfEMP1 and less able to disrupt rosettes when parasites are grown in Group A versus Group O RBC since the tighter rosettes formed in blood group A RBC hinder recognition.[7,14] Thus, rosette formation gives the parasite an advantage by blocking the pRBC from antibody-binding and subsequent clearance by host phagocytic cells and increased phagocytosis of parasitized O as compared to A RBC has been demonstrated.[7,15]

Understanding the effect of the ABO blood group on the clinical manifestations of Plasmodium falciparum infection can not only contribute to the understanding of the pathogenesis and clinical morbidity of malaria but also to the anticipation of malaria management interventions in Africa where this parasitosis is endemic. Although basic research is trying to establish the link between the ABO blood group and the complication of malaria, there is still insufficient evidence from the epidemiological research. Thus, we hypothesized that the prevalence or odds of severe malaria of P. falciparum would be higher in the individuals of blood Groups A, B, and AB than in those of blood Group O.

We herein report on a study assessing the association between severe malaria and the ABO blood groups among acute febrile patients who sought medical attention at General Hospital of Rungu, in the Democratic Republic of the Congo (DRC).

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Ethical consideration

The ethical clearance for this study was granted by the Ethics Committee of the Kisangani's University. All participants gave their written informed consent to participate in this study. For minors (newborn, infant, and adolescent), written consent was signed by a parent or guardian as recommended by ethics committees. This study was conducted to treat. Indeed, malaria positive cases were treated with antimalarial drugs based on the current national treatment guidelines of DRC.[16]

Study design and study setting

A cross-sectional hospital-based study was carried out between August and October 2018 at the General Hospital of Rungu, Rungu, in the DRC. Rungu is located 65 kilometers from Isiro, the chief town of the province of Haut-Uélé. General Hospital of Rungu serves a population of 114,929 inhabitants, with an attendance of about 6285 patients per year. Note that, Rungu is characterized by equatorial epidemiological facies of malaria with a high transmission all year long.

Study population

All the participants were orally explained about the study aims and were recruited upon obtaining informed consent from study participants or their parent or guardian. The inclusion criteria were: (i) To be outpatients or inpatients who sought medical attention at the Rungu's General Hospital, (ii) to have a fever on admission or during the period of hospitalization, and to be naive to anti-malarial drugs. All individuals who were not febrile, who took antimalarial drugs within 2 weeks before the blood test, and who refused to participate in the study were excluded. A sample size calculated at 95% confidence level and 5% confidence interval (CI) was estimated at 384 individuals.[17]

Data collection and laboratory procedure

The investigators (physicians or nurses) were trained about how to collect sample and explanation was given before the data collection. The investigators recorded on a survey form the patients' sex as either male or female based on their observation and the patients' age in years or months for children <1year.

Capillary blood was collected by finger pricking using 70% alcohol and sterile disposable lancet. Thick and thin films were prepared on the same slide. Thin films were fixed with methanol. The blood films were stained with 10% Giemsa for 10 min. Finally, the films were examined under an oil immersion microscope objective (×100). Thick blood film was used to determine the parasite densities while thin blood films were used for species differentiation (confirm Plasmodium species) if doubtful on thick films. The asexual parasite density (asp/μl) was estimated using the formula = Asexual parasites counted/200 white blood cells counted × 40.[16] Furthermore, 4 ml of venous blood specimens were taken from each participant in K3-EDTA tubes for the hematological examinations. Sysmex XP-300™ Automated Hematology Analyzer (Sysmex Corporation, Chuo-ku, Japon) was used to determine complete blood count. The blood group of the study participants was determined by direct slide method, using agglutinating A and B monoclonal Eryclone® antisera together with the manufacturer's procedures.

Severe malaria was operationally defined as the following criteria: to have a fever with a temperature above 39° Celsius associated with a P. falciparum positive microscopy; to have an asexual parasite density above 10,000 asp/μl of blood; and to have hemoglobin level <7 g/dL.[18] On the other hand, any febrile patient with Plasmodium positive microscopy without our operational criteria for severe malaria was considered to have uncomplicated malaria.

Data analysis

All the data were entered into an Excel spreadsheet and analyzed using IBM® SPSS® Statistics 20 software (IBM, SPSS Inc., Armonk, New York, USA). After computing descriptive statistics, Pearson's Chi-square test was used for the comparison of the frequencies, whereas Fisher's exact test was used when there was a theoretical proportion <5. The analysis of variance was used for the comparison of means of asexual parasite density. The Wilson score bounds were used for calculating the 95% CI. Finally, multivariate logistic regression analysis was used to assess the strength of association of ABO blood group antigens and other independent factors with severe malaria and to control possible confounders. P < 0.05 was considered as statistically significant.

RESULTS

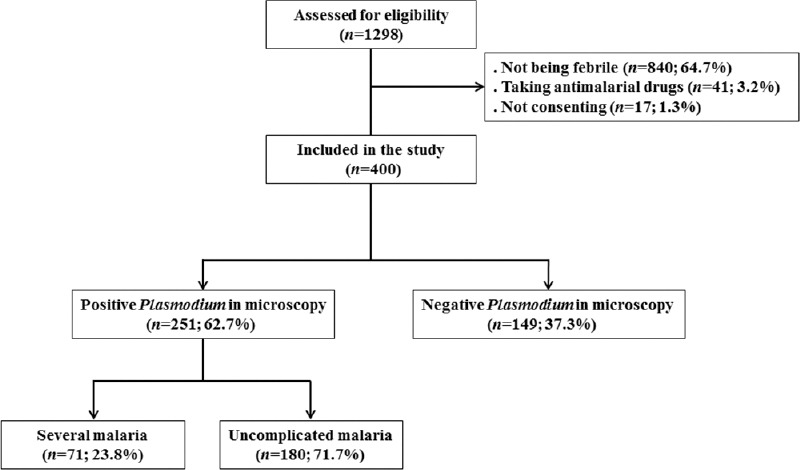

A total of 1298 participants were screened for eligibility. Among them, 400 (30.8%) febrile patients were enrolled and 898 (69.2%) were ineligible on basis of consent (n = 17; 1.3%), taking antimalarial drugs within 2 weeks before blood test (n = 41; 3.2%), and temperature assessing (n = 840; 64.7%).

Overall, 251 (62.7%) participants were positive P. falciparum in the microscopy test. Among them, 126 (50.2%) were female; majority (n = 154; 61.4%) had <5 years; more than four-fifth (n = 213; 84.9%) declared use the insecticide-treated mosquito nets; and the predominant blood group was O (n = 117; 46.6%) followed by A (n = 81; 32.3%), B (n = 46; 18.3%) and AB (n = 7; 2.8%). Finally, 180 (71.7% (95% CI: 67.1–75.9]) patients were diagnosed having uncomplicated malaria, whereas 71 (28.3% (95% CI: 24.1–32.9]) were diagnosed having severe malaria [Figure 1].

Figure 1.

Flow chart showing the recruitment of patients and the microscopy test and clinical outcome malaria evaluations

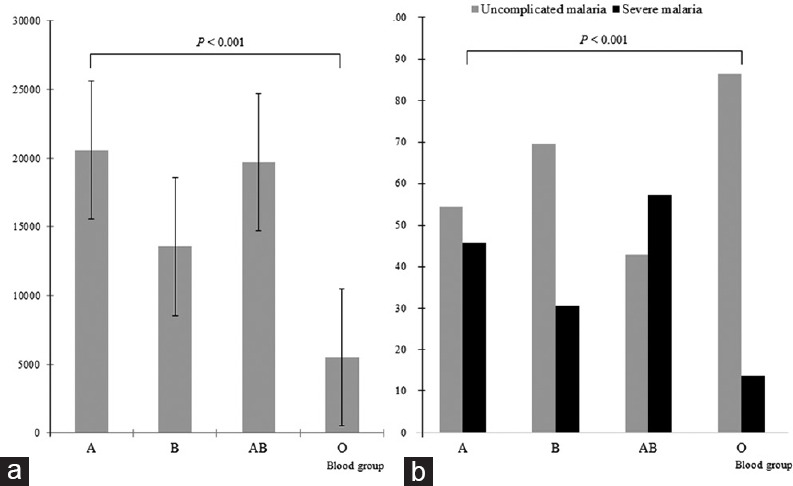

As shown in Figure 2, the mean of asexual parasite density was significantly high in patients with non-O blood group (A blood group: 20,592 [standard deviation (SD): 5,789]; B blood group: 13,563 [SD: 6,584]; AB blood group: 19,696 [SD: 6,048]) while it was relatively low in patients with O blood group (5,506 [SD: 4,915]; P < 0.001) [Figure 2a]. Furthermore, the rate of severe malaria was low among patients with O blood group (13.7%) while it was high in patients with A (45.8%), B (30.4%), and AB (57.1%) blood groups (P < 0.001) [Figure 2b].

Figure 2.

Comparison of the asexual parasite density means according ABO blood group (a) and comparison of severe malaria rate with ABO blood group (b). The error bars represent the standard deviation of the asexual parasite density means

In the multivariate analysis using the logistic regression models,[Table 1] severe malaria was high among patients with A blood group compared to those with O blood group (45.8% vs. 13.7%; adjusted odds ratio [OR]: 5.3 [95% CI: 2.7–10.5]; P < 0.001). Moreover, severe malaria was also high among patients aged <5 years (adjusted OR: 27.1 [95% CI: 7.3–100.6]; P < 0.001) and those who not used insecticide-treated mosquito nets (adjusted OR: 27.1 [95% CI: 7.3-100.6]).

Table 1.

Bivariate and multivariate regression analysis of factors associated with severe malaria among 251 febrile patients with positive Plasmodium falciparum in microscopy test

| Characteristics | Total (n=251) | Malaria characteristic | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||||||

| Uncomplicated (n=180), n (%) | Severe (n=71), n (%) | cOR (95% CI) | P* | aOR (95% CI) | P** | ||

| Sex | |||||||

| Male | 125 | 88 (70.4) | 37 (29.6) | 0.9 (0.5-1.5) | 0.645 | NS | NS |

| Female | 126 | 92 (73.0) | 34 (27.0) | Reference | NS | NS | |

| Age (years) | |||||||

| 0-5 | 154 | 90 (58.4) | 64 (41.6) | 29.5 (8.2-102.1) | <0.001 | 27.1 (7.3-100.6) | <0.001 |

| 6-15 | 26 | 22 (84.6) | 4 (15.4) | 5.7 (1.0-10.5) | 6.3 (0.8-35.4) | 0.057 | |

| >15 | 71 | 68 (95.8) | 3 (4.2) | Reference | Reference | - | |

| Use of insecticide-treated mosquito nets | |||||||

| No | 38 | 19 (50.0) | 19 (50.0) | Reference | 0.002 | Reference | - |

| Yes | 213 | 161 (75.6) | 52 (24.4) | 0.3 (0.1-0.7) | 0.3 (0.1-0.6) | 0.002 | |

| Blood group | |||||||

| A | 81 | 44 (54.2) | 37 (45.8) | 3.3 (1.8-5.8) | <0.001 | 5.3 (2.7-10.5) | <0.001 |

| B | 46 | 32 (69.6) | 14 (30.4) | 1.1 (0.6-2.3) | 2.8 (0.9-4.3) | 0.075 | |

| AB | 7 | 3 (42.9) | 4 (57.1) | 3.5 (0.8-16.2) | 3.4 (0.7-21.2) | 0.199 | |

| O | 117 | 101 (86.3) | 16 (13.7) | Reference | Reference | - | |

| Rhesus | |||||||

| Positive | 250 | 179 (71.6) | 71 (28.4) | NA | 0.529 | NS | NS |

| Negative | 1 | 1 (100.0) | 0 | NA | NS | NS | |

*P calculated using pearson’s Chi-square test or Fisher’s exact test, **P calculated using logistic regression analysis. aOR: Adjusted odds ratio, cOR: Crude odds ratio, CI: Confidence interval, NA: Not applicable, NS: Not significant

DISCUSSION

Malaria is an important public health concern due to its associated high mortality and morbidity in the many parts of the world. It is, therefore, important to identify the factors which contribute to the susceptibility of hosts. Herein, we have assessed the association of ABO blood group antigens with severe malaria in an equatorial facies of malaria context of Central Africa with a high transmission all year long. Our findings showed that ABO blood group was associated with severe malaria; severe malaria significantly increased among febrile patients having A blood group, whereas it decreased among febrile patients of O blood group. Furthermore, a higher rate of blood Group O was observed in uncomplicated cases, an indication of its possible protective property against severity as indicated in previous reports.[3,6,7,8]

Several mechanisms relate to these associations, including an affinity for Anopheles species, shared ABO antigens with P. falciparum, impairment of merozoite penetration of RBCs, as well as cytoadherence, endothelial activation, and resetting.[19,20] The phenomenon of resetting is the most documented.[6,7,8] While blood type A delays clearance of parasitized RBCs (pRBCs) by promoting resetting and cytoadherence, blood group O increases clearance of pRBC by reducing resetting and cytoadherence.[12,13]

Although in our series, Group A increased the rate of severe malaria as reported in sub-Saharan Africa,[2,3,21,22] other studies have rather demonstrated the involvement of Group B in severe malaria.[23] Blood group AB has also been reported to be associated with severity of malaria.[24] By contrast, the absence of association between ABO system and malaria infection was also observed in other populations.[25] Our findings should clarify the national policy on malaria management by including ABO blood group as a decision criterion. Thus, febrile children under 5 years of group A, with positive microscopy P. falciparum should be considered potentially susceptible to severe malaria, de facto, they will need close monitoring to reduce the risk of malarial mortality.

As scientific studies on population genetics have established a relationship between sickle cell disease and malaria, other large-scale studies are important to highlight the link between the ABO group and malaria.[4] This is because the Group O has been found to be the most common blood group in sub-Saharan African and malaria would certainly play a role in selective pressure.[25]

There are however limitations in our study. This study was conducted exclusively at the General Hospital of Rungu, including successively any febrile patient. This study design is limited because of the selection bias. Our operational definition of severe malaria may lead to possible classification bias. Finally, several RBCs polymorphisms, including those linked to glucose-6-phosphate dehydrogenase, pyruvate kinase, complement receptor-1, and hemoglobinopathies (sickle cells disease, thalassemia, etc.), have a role in the clinical outcome of malaria but were not included for the analysis in the present study.[20]

CONCLUSION

This field study demonstrates that patients with A blood group had a high susceptibility to severe malaria compared to those with O blood group. Further in-depth studies are required to establish the role of ABO blood groups in P. falciparum malaria.

Ethical clearance

The ethical clearance for this study was granted by the Ethics Committee of the Kisangani's University.

Financial support and sponsorship

Nil.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

Acknowledgments

The authors are grateful to the patients for their willingness to participate to the study. We also thank the medical specialists and generalists working in the Departments of Internal Medicine and paediatrics of the General Hospital of Rungu. Finally, our thanks go to Eric Dradre for his technical support during data collection.

REFERENCES

- 1.World Health Organization. Getting the Global Malaria Response Back on Track. [Last accessed on 2020 Jul 20]. Available from: https://www.who.int/malaria/ publications/world-malaria-report-2018/wmr2018-dg-foreword-eng. pdf?ua=1 .

- 2.Amoako N, Asante KP, Adjei G, Awandare GA, Bimi L, Owusu-Agyei S. Associations between red cell polymorphisms and Plasmodium falciparum infection in the middle belt of Ghana. PLoS One. 2014;9:e112868. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0112868. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Nasr A, Saleh AM, Eltoum M, Abushouk A, Hamza A, Aljada A, et al. Antibody responses to P.falciparum Apical Membrane Antigen 1(AMA-1) in relation to haemoglobin S (HbS), HbC, G6PD and ABO blood groups among Fulani and Masaleit living in Western Sudan. Acta Trop. 2018;182:115–23. doi: 10.1016/j.actatropica.2018.02.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ahmed JS, Guyah B, Sang' D, Webale MK, Mufyongo NS, Munde E, et al. Influence of blood group, Glucose-6-phosphate dehydrogenase and Haemoglobin genotype on Falciparum malaria in children in Vihiga highland of Western Kenya. BMC Infect Dis. 2020;20:487. doi: 10.1186/s12879-020-05216-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Loscertales MP, Brabin BJ. ABO phenotypes and malaria related outcomes in mothers and babies in The Gambia: A role for histo-blood groups in placental malaria? Malar J. 2006;5:72. doi: 10.1186/1475-2875-5-72. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Rowe JA, Handel IG, Thera MA, Deans AM, Lyke KE, Koné A, et al. Blood group O protects against severe Plasmodium falciparum malaria through the mechanism of reduced rosetting. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2007;104:17471–6. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0705390104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Moll K, Palmkvist M, Ch'ng J, Kiwuwa MS, Wahlgren M. Evasion of Immunity to Plasmodium falciparum: Rosettes of blood group a impair recognition of PfEMP1. PLoS One. 2015;10:e0145120. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0145120. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Degarege A, Gebrezgi MT, Ibanez G, Wahlgren M, Madhivanan P. Effect of the ABO blood group on susceptibility to severe malaria: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Blood Rev. 2019;33:53–62. doi: 10.1016/j.blre.2018.07.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Migot-Nabias F, Mombo LE, Luty AJ, Dubois B, Nabias R, Bisseye C, et al. Human genetic factors related to susceptibility to mild malaria in Gabon. Genes Immun. 2000;1:435–41. doi: 10.1038/sj.gene.6363703. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Moxon CA, Grau GE, Craig AG. Malaria: Modification of the red blood cell and consequences in the human host. Br J Haematol. 2011;154:670–9. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2141.2011.08755.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Band G, Rockett KA, Spencer CC, Kwiatkowski DP, editors. A novel locus of resistance to severe malaria in a region of ancient balancing selection. Malaria Genomic Epidemiology Network Nature. 2015;526:253–7. doi: 10.1038/nature15390. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Wahlgren M, Goel S, Akhouri RR. Variant surface antigens of Plasmodium falciparum and their roles in severe malaria. Nat Rev Microbiol. 2017;15:479–91. doi: 10.1038/nrmicro.2017.47. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.McQuaid F, Rowe JA. Rosetting revisited: A critical look at the evidence for host erythrocyte receptors in Plasmodium falciparum rosetting. Parasitology. 2020;147:1–11. doi: 10.1017/S0031182019001288. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Quintana MD, Ch'ng JH, Moll K, Zandian A, Nilsson P, Idris ZM, et al. Antibodies in children with malaria to PfEMP1, RIFIN and SURFIN expressed at the Plasmodium falciparum parasitized red blood cell surface. Sci Rep. 2018;8:3262. doi: 10.1038/s41598-018-21026-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Wolofsky KT, Ayi K, Branch DR, Hult AK, Olsson ML, Liles WC, et al. ABO blood groups influence macrophage-mediated phagocytosis of Plasmodium falciparum – Infected erythrocytes. PLoS Pathog. 2012;8:e1002942. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1002942. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.République Démocratique du Congo, Programme National de Lutte Contre le Paludisme (PNLP), “Projet de Politique Nationale de Lutte Contre le Paludisme; ”. 2014. [Last accessed on 2019 Jan 17]. Available from: https://www.medbox. org/projet-de-politique-nationale-de-lutte-contre-le-paludisme/ download.pdf .

- 17.Hajian-Tilaki K. Sample size estimation in epidemiologic studies. Caspian J Intern Med. 2011;2:289–98. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.World Health Organization (WHO) World Malaria Report 2018. 2019. [Last accessed on 2019 Jan 17]. Available from: https://www.who.int/malaria/publications/ world-malaria-report-2018/en/

- 19.Loscertales MP, Owens S, O'Donnell J, Bunn J, Bosch-Capblanch X, Brabin BJ. ABO blood group phenotypes and Plasmodium falciparum malaria: Unlocking a pivotal mechanism. Adv Parasitol. 2007;65:1–50. doi: 10.1016/S0065-308X(07)65001-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kuesap J, Na-Bangchang K. The Effect of ABO Blood Groups, hemoglobinopathy, and heme oxygenase-1 polymorphisms on malaria susceptibility and severity. Korean J Parasitol. 2018;56:167–73. doi: 10.3347/kjp.2018.56.2.167. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Zerihun T, Degarege A, Erko B. Association of ABO blood group and Plasmodium falciparum malaria in Dore Bafeno Area, Southern Ethiopia. Asian Pac J Trop Biomed. 2011;1:289–94. doi: 10.1016/S2221-1691(11)60045-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Panda AK, Panda SK, Sahu AN, Tripathy R, Ravindran B, Das BK, et al. Association of ABO blood group with severe falciparum malaria in adults: Case control study and metaanalysis. Malar J. 2011;10:309. doi: 10.1186/1475-2875-10-309. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Tekeste Z, Petros B. The ABO blood group and Plasmodium falciparum malaria in Awash, Metehara and Ziway areas, Ethiopia. Malar J. 2010;9:280. doi: 10.1186/1475-2875-9-280. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Montoya F, Restrepo M, Montoya AE, Rojas W. Blood groups and malaria. Rev Inst Med Trop. 1994;36:33–8. doi: 10.1590/s0036-46651994000100006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Boateng LA, Campbell AD, Davenport RD, Osei-Akoto A, Hugan S, Asamoah A, et al. Red blood cell alloimmunization and minor red blood cell antigen phenotypes in transfused Ghanaian patients with sickle cell disease. Transfusion. 2019;59:2016–22. doi: 10.1111/trf.15197. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]