Why was the EPIPAGE-2 cohort set up?

Prematurity has shown an upward trend since 1990, accounting for about 10% of births worldwide, representing almost 15 million babies born every year before 37 weeks’ gestation.1,2 In France, the preterm birth rate was 7.4% in 2010, with about 60 000 babies born preterm every year.3

The burden of preterm birth is substantial: it remains a major cause of child mortality during both the neonatal period and childhood before the age of 5 years.4 Among survivors, the frequency of prematurity-related health problems and developmental deficiencies is substantial, in the short and in the long term after birth.2,5 With prematurity and survival rates both increasing, these ‘individuals born preterm’ represent a growing share of the population, displaying specific health care and support needs.

Population-based cohort studies are the methodology of reference for assessing the longitudinal evolution of these fragile infants. Several European and international cohorts have been conducted since the late 1990s, mainly focusing on children born extremely preterm, between 22 and 26 weeks’ gestation.6–9 Only a few studies included infants born very (27–31 weeks) or moderately (32–34 weeks) preterm, although they are more numerous and with a greater impact on public health indicators.10,11

The first EPIPAGE (Etude Épidémiologique sur les Petits Âges Gestationnels) cohort study was launched in 1997 in nine French regions, including births occurring at 22–32 weeks’ gestation, with follow-up steps until age 8 years.12 The cohort provided estimates of mortality, morbidity and disability and health care needs and greatly contributed to changing practices in the neonatal period and after hospital discharge.13,14

Medical practices and the organization of care vary widely across countries and have markedly evolved over the past two decades.15–17 The prognosis of very preterm infants has changed accordingly, raising new questions and requiring new assessments.17 We therefore set up the EPIPAGE-2 cohort, a new longitudinal study of preterm infants, with the following objectives: to provide actualized estimates of short- and long-term outcomes for extremely, very and moderately preterm babies and their families; to study changes in practices at both individual and organizational levels and their impact on child health and development; and to explore aetiologies of preterm birth and identify early predictors of adverse outcomes.17

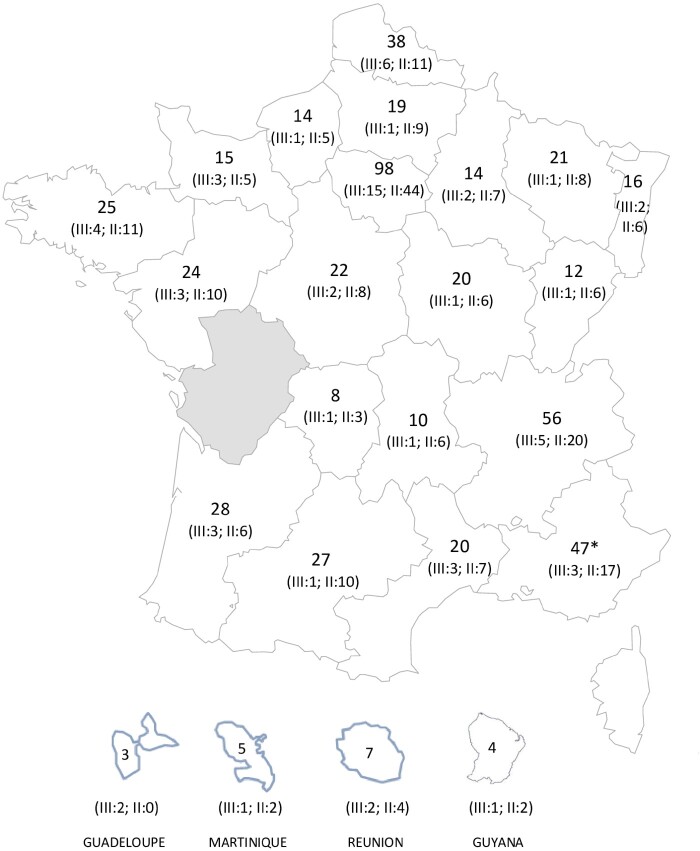

EPIPAGE-2 is a population-based cohort study, set up in 2011 in 25 regions in France (21 of the 22 metropolitan regions and four overseas regions). Only one region (Poitou-Charentes), accounting for 2.2% of all births in France in 2011, did not participate because of organizational issues. All maternity units and neonatology departments participated in the recruitment (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Number of maternity units in the French regions involved in the EPIPAGE-2 cohort study. III, type III maternity unit; II, type II maternity unit. *Including maternity units from Corsica

The establishment of the cohort required a close collaboration between the EPOPé research team [National Institute of Health and Medical Research (Inserm U1153), Université de Paris] on the one hand, and a national group of participants from 555 French maternity units, 281 neonatology departments and 39 perinatal networks and parent associations, on the other hand. At a national level, a steering committee, including epidemiologists, paediatricians and obstetricians, was in charge of designing the scientific project and the overall study organization. In each region, a coordinating committee was responsible for implementing the study at the regional level. Local clinical teams from maternity and neonatal units were involved in inclusions and data collection, with the help of regional coordinators.

The study relies on several sources of funding, including support from the French National Institute of Public Health Research (IRESP TGIR 2009–01 programme)/Institute of Public Health and its partners [the French Health Ministry, the National Institute of Health and Medical Research (INSERM), the National Institute of Cancer, the National Solidarity Fund for Autonomy (CNSA)], the National Research Agency through the French EQUIPEX program of investments for the future (grant no. ANR-11-EQPX-0038) and the PremUp Foundation. Additional funding was obtained from the Fondation pour la Recherche Medicale (SPF 20160936356) and Fondation de France (00050329 and R18202KK [Grand Prix]).

As required by French law and regulations, recruitment and follow-ups were approved by the national data protection authority (Commission Nationale de l’Informatique et des Libertés, CNIL DR-2011–089, DR-2012–246, DR-2013–406, DR-2016–290) and by the appropriate ethics committees, i.e. the advisory committee on the treatment of personal health data for research purposes (Comité Consultatif sur le Traitement de l'Information en matière de Recherche, CCTIRS, reference nos. 10–626, 12–109 and 16–263) and the committee for the protection of people participating in biomedical research (Comité de Protection des Personnes, CPP, reference nos. 2011-A00159-32 and 2016-A0033-48).

Who is in the EPIPAGE-2 cohort?

Recruitment took place in all maternity units of the 25 participating regions during an 8-month period for extremely preterm births (22–26 weeks) and during a 6-month period for very preterm births (27–31 weeks) (Figure 1). A sample of moderately preterm births (32–34 weeks) was recruited during a 5-week period. Further details can be found in the study protocol.17

Eligibility was based on gestational age at birth. Participation in the study was proposed to the parents of all eligible children after they received appropriate information, in the maternity or neonatal unit. During recruitment, regional coordinators visited all maternity units to ensure the identification of all eligible children. Only families who orally agreed to participate were included. The only exclusion criterion was refusal to participate.

During the recruitment period, 8400 births were eligible, including terminations of pregnancy, stillbirths and live births, among whom 7804 (93%) were enrolled in the study. Refusal rate at baseline was 7% (n = 596). With ethics committee approval, a small number of basic perinatal data were collected from birth certificates for all eligible births, in order to characterize non-participants. Neonates whose parents refused participation were more frequently born at 32–34 weeks’ gestation and to younger mothers of lower socioeconomic position (SEP) (Table 1).

Table 1.

Comparison of participants and non-participants at recruitment and at follow-up invitation

| No. of events/No. in group %a |

|||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Recruitment (N = 8400) |

Invitation to follow-up among survivors at discharge (N = 4467) |

||||||||||

| Participants n = 7804 | Refusals n = 596 | P-value | Participants n = 4312 | Refusals n = 155 | P-value | ||||||

| Maternal characteristics | |||||||||||

| Age, years | |||||||||||

| <20 | 269/7781 | 2.9 | 47/596 | 8.4 | <0.001 | 138/4312 | 2.5 | 10/155 | 7.8 | 0.009 | |

| 20-35 | 6103/7781 | 79.4 | 435/596 | 71.6 | 3424/4312 | 80.3 | 118/155 | 74.8 | |||

| >35 | 1409/7781 | 17.7 | 114/596 | 20.0 | 750/4312 | 17.2 | 27/155 | 17.4 | |||

| Parents’ socioeconomic positionb | |||||||||||

| Manager | 1386/6965 | 21.6 | 35/447 | 8.6 | <0.001 | 909/4090 | 23.2 | 14/133 | 11.0 | <0.001 | |

| Professional | 1393/6965 | 21.1 | 62/447 | 12.8 | 873/4090 | 22.1 | 11/133 | 11.5 | |||

| Intermediatec | 1850/6965 | 26.8 | 93/447 | 23.1 | 1118/4090 | 27.3 | 35/133 | 30.1 | |||

| Sales and services worker | 1004/6965 | 14.0 | 69/447 | 12.5 | 583/4090 | 13.8 | 24/133 | 18.7 | |||

| Manual worker | 934/6965 | 12.1 | 87/447 | 18.3 | 482/4090 | 10.9 | 32/133 | 17.1 | |||

| Unknown | 398/6965 | 4.4 | 101/447 | 24.7 | 125/4090 | 2.7 | 17/133 | 11.6 | |||

| Smoking during pregnancy, yes | 1534/7457 | 20.3 | 113/552 | 23.8 | ns | 896/4166 | 20.4 | 38/147 | 26.8 | ns | |

| Obstetric characteristics | |||||||||||

| No previous pregnancy | 2748/7787 | 36.3 | 203/590 | 33.4 | ns | 1561/4303 | 37.1 | 52/155 | 40.8 | ns | |

| Multiple pregnancy | 1987/7804 | 30.5 | 109/596 | 16.5 | <0.001 | 1451/4312 | 35.7 | 51/155 | 31.5 | ns | |

| Neonatal characteristics Gestational age at birth, weeks | |||||||||||

| 22-26 | 3045/7804 | 18.4 | 215/596 | 13.8 | <0.001 | 529/4312 | 4.4 | 22/155 | 4.1 | <0.001 | |

| 27-31 | 3510/7804 | 28.7 | 235/596 | 20.4 | 2648/4312 | 29.6 | 75/155 | 19.1 | |||

| 32-34 | 1249/7804 | 52.9 | 146/596 | 65.8 | 1135/4312 | 66.0 | 58/155 | 76.8 | |||

ns, non significant.

Weighted percentages.

Defined as the highest occupational status between current (or former) occupations of the mother and the father, or mother only if living alone, and based on the Classification of Professions and Socioprofessional Categories, developed by the French National Institute of Statistics and Economic Studies.

Intermediate socioeconomic position includes employees from administration and public service, self-employed and students.

The follow-up was proposed to all families of children discharged alive from hospital (i.e. 4467 children). The families of 155 children (3%) had agreed to participate at baseline but secondarily refused to take part in the follow-up. Thus, 4312 children were eligible for the follow-up. Families who refused the follow-up had a similar profile to that described for the initial refusals in terms of maternal age, SEP and gestational age at birth (Table 1). All children whose parents agreed to participate in the follow-up were invited at each follow-up step, whether they had participated in the previous follow-up or not, unless parents asked to stop their participation in the study.

How often have they been followed up?

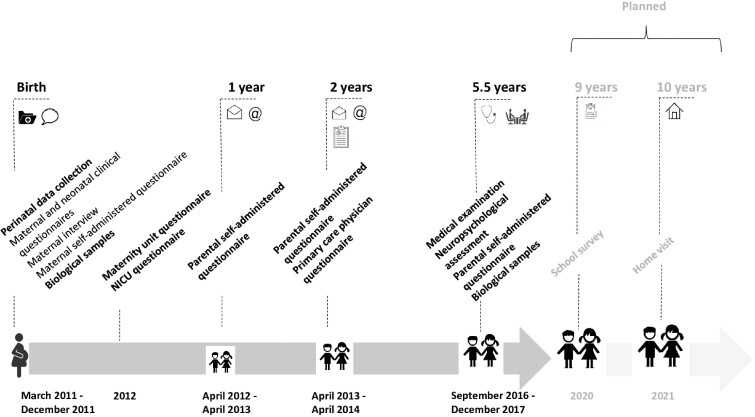

From 2011 to 2017, evaluation at baseline and three follow-up steps were performed at 1 and 2 years’ corrected age and at 5.5 years (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Assessments and data collection. NICU, neonatal intensive care unit

Assessment schedule

At birth and during the neonatal period, maternal and neonatal data were extracted from medical records. Moreover, we interviewed mothers in the neonatal units during the infant’s hospitalization and mothers completed a self-administered questionnaire just before the baby’s discharge.

At each follow-up step, parents completed self-administered questionnaires. Additionally, at 2 years’ corrected age, the child’s referring physician completed a standardized questionnaire. At 5.5 years, children had a clinical examination by a physician and a cognitive assessment by a neuropsychologist, both performed in one of 110 dedicated examination centres in all participating regions. All professionals were specifically trained to ensure homogeneity in data collection.

Follow-up perspectives

To better understand the specific educational difficulties encountered by very preterm children, a school survey will be performed in September 2020, when most children will be in the 4th year of primary school. The survey will comprise tests in French and arithmetic and a few questions for children about their well-being at school. A questionnaire will be completed by the teacher on the child’s behaviour and position in the class.

Finally, children will be directly interviewed for the first time at 10.5 years of age (2021–22), at home. This step of follow-up will allow for assessing development and health status and collecting biological samples

What is attrition like?

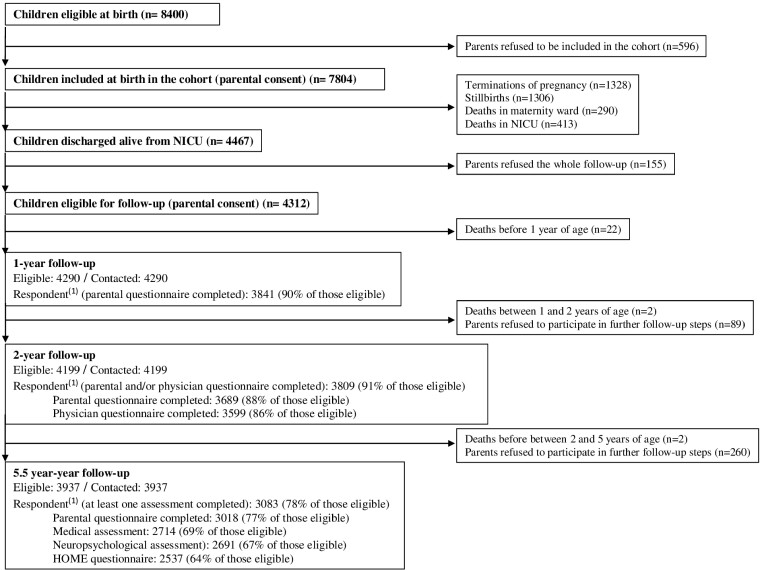

Overall, the families extensively collaborated in the study, with a participation rate of 93% (7804 children) at baseline. A total of 26 children died between their discharge from hospital and the 5.5-year follow-up. The families of 504 children (11%) decided to stop their participation in follow-up: 155 (3%) before 1 year, 89 (2%) between 1 and 2 years and 260 (6%) at 5.5 years. At 5.5 years, 3937 (86%) children discharged alive from neonatal units remained in the cohort (Figure 3).

Figure 3.

Participation from birth to 5.5 years in the EPIPAGE-2 cohort. (1) Respondent: includes complete and incomplete questionnaires. No completed questionnaire whatever the follow-up step: 117/4286 (3%). NICU, neonatal intensive care unit

The parents’ response rates were 90% and 91% at 1 and 2 years, respectively. At 5.5 years, at least one assessment was performed for 3083 (78%) children (Figure 3). A total of 117 (3%) children, still alive, were never assessed whatever the follow-up step, despite parents never declining participation in the study.

Mothers of children who did not participate at 5.5 years were younger, had lower educational level and SEP and were more frequently single than those who did participate; however, the two groups did not differ in children’s characteristics (Table 2).

Table 2.

Comparison of respondents and non-respondents at 5.5 years among the 4286 eligible children

| No. of events/No. in group %a |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Respondent at 5.5 years |

Non-respondent at 5.5 years |

||||

| n = 3083 | n = 1203 | P-value | |||

| Gestational age, weeks | |||||

| 24-26 | 379/3083 | 4.5 | 143/1203 | 4.0 | 0.0003 |

| 27-31 | 1934/3083 | 31.1 | 701/1203 | 26.2 | |

| 32-34 | 770/3083 | 64.4 | 359/1203 | 69.8 | |

| Maternal characteristics at birth | |||||

| Maternal age at birth, years | |||||

| <20 | 67/3083 | 1.4 | 70/1203 | 5.0 | <0 .001 |

| 20-35 | 2476/3083 | 80.8 | 929/1203 | 79.4 | |

| >35 | 540/3083 | 17.8 | 204/1203 | 15.6 | |

| Mother born in France | 2506/3074 | 84.4 | 822/1175 | 72.2 | <0 .001 |

| Mother living with a partner | 2725/2925 | 94.1 | 977/1130 | 85.8 | <0 .001 |

| Parents’ socioeconomic positionb | |||||

| Manager | 750/2959 | 26.4 | 157/1108 | 15.8 | <0 .001 |

| Professional | 704/2959 | 24.8 | 168/1108 | 15.9 | |

| Intermediatec | 766/2959 | 25.4 | 349/1108 | 32.3 | |

| Sales and services worker | 370/2959 | 12.0 | 207/1108 | 17.5 | |

| Manual worker | 315/2959 | 9.6 | 157/1108 | 13.3 | |

| Unknown | 54/2959 | 1.7 | 70/1108 | 5.1 | |

| Maternal level of education | |||||

| Lower secondary | 845/2982 | 26.9 | 472/1070 | 42.2 | <0 .001 |

| Upper secondary | 616/2982 | 20.5 | 258/1070 | 24.4 | |

| Post-secondary, not tertiary | 629/2982 | 21.6 | 158/1070 | 14.5 | |

| Bachelor degree or more | 892/2982 | 31.0 | 182/1070 | 18.9 | |

| Multiple pregnancy | 1079/3083 | 37.4 | 366/1203 | 32.0 | 0.001 |

| Children characteristics | |||||

| Male | 1638/3083 | 54.9 | 621/1203 | 49.5 | 0.02 |

| Small-for-gestational aged | 1069/3082 | 34.1 | 407/1203 | 33.5 | ns |

| Severe neonatal morbiditiese | 376/2936 | 7.0 | 140/1130 | 5.9 | ns |

| Cerebral palsy at 2 years | 104/2848 | 2.4 | 33/750 | 2.0 | ns |

ns: non significant.

Weighted percentages.

Defined as the highest occupational status between current (or former) occupations of the mother and the father, or mother only if living alone, and based on the Classification of Professions and Socioprofessional Categories, developed by the French National Institute of Statistics and Economic Studies.

Intermediate socioeconomic position includes employees from administration and public service, self-employed and students.

Defined as birthweight less than the 10th percentile for gestational age and sex based on French intrauterine growth curves (Ego 2016).

Defined as severe bronchopulmonary dysplasia or necrotizing enterocolitis stage 2–3 or severe retinopathy of prematurity stage >3 or any of the following severe cerebral abnormalities on cranial ultrasonography: intraventricular haemorrhage grade III or IV or cystic periventricular leukomalacia.

What has been measured?

Overall, almost 5 000 variables have been collected from baseline to 5.5-year follow-up. All questionnaires are available at [https://pandora-epipage2.inserm.fr/public/index.php]. Table 3 summarizes the main types of data collected on maternal health, antenatal management, parental sociodemographic characteristics and family lifestyle. Table 4 presents the data collected on child’s health, development and health care use.18–20 The standardized scales used in the EPIPAGE-2 questionnaires are presented in Table 5.21–32

Table 3.

Data collected on maternal health, antenatal management, family’s sociodemographic characteristics and lifestyle

| Birth | 1 year | 2 years | 5.5 years | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Maternal health | ||||

| Medical history |

|

– | – | – |

| Obstetric history |

|

– | – | – |

| Pregnancy complications |

|

– | – | – |

| Post-partum depression |

|

- | - | - |

| Post-partum anxiety |

|

– | – | – |

| Global self-rated health | – |

|

|

|

| Mental self-rated health | – |

|

|

|

| Physical self-rated health | – |

|

|

|

| Antenatal management | ||||

| Diagnosis and medical management |

|

– | – | – |

| Ultrasonography and blood tests |

|

– | – | – |

| Treatments and medications |

|

– | – | – |

| Hospitalizations during pregnancy |

|

– | – | – |

| Indications for medical interventions |

|

– | – | – |

| Delivery and post-partum |

|

– | – | – |

| Parental sociodemographic characteristics | ||||

| Familial status |

|

|

|

|

| Occupational status |

|

|

|

|

| Educational level |

|

|

|

|

| Country of birth/nationality |

|

|

||

| Family’s lifestyle, living conditions and living standards | ||||

| Household composition |

|

|

|

|

| Monthly household income |

|

|

||

| Social security coverage |

|

|

||

| Type of housing |

|

|

|

|

| Language spoken at home |

|

|

|

The table specifies whether the information was collected from medical records ( ), mother’s interview (

), mother’s interview ( ), parental self-administered questionnaire (

), parental self-administered questionnaire ( ) or not collected at this follow-up (-).

) or not collected at this follow-up (-).

Table 4.

Data collected on child’s health, development, health care use

| Birth | 1 year | 2 years | 5.5 years | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gestational agea |

|

– | – | – |

| Sex |

|

– | – | – |

| Health and growth | ||||

| Apgar score |

|

– | – | – |

| Anthropometric measures |

|

|

|

|

| Blood pressure |

|

– | – |

|

| Cardiovascular diseases |

|

– |

|

|

| Respiratory diseases |

|

|

|

|

| Neurological diseases |

|

|

|

|

| Gastrointestinal diseases |

|

|

|

|

| Hearing/vision |

|

|

|

|

| Hospitalizations |

|

|

|

|

| Sleep | – |

|

|

|

| Breastfeeding |

|

|

– | – |

| Eating behaviour | – |

|

|

|

| Development and behaviour | ||||

| Global development (ASQ) | – | – |

|

– |

| Language skills (IFDC, WPPSI IV) | – | – |

|

|

| Full-scale Intelligence Quotient (WPPSI IV) | – | – | – |

|

| Executive functions (NEPSY 2) | – | – | – |

|

| Behaviour and autism spectrum disorders | – | – |

|

|

| SDQ | – | – | – |

|

| M-CHAT | – | – |

|

– |

| SCQ | – | – | – |

|

| Motor skills | – |

|

|

– |

| M-ABC2 | – | – | – |

|

| Cerebral palsyb | – | – |

|

|

| Health care usec |

|

|

|

|

| Medications |

|

|

|

|

| Vaccinations |

|

|

|

– |

| Quality of life (PedsQL™) | – | – | – |

|

| Child care and school attendance | – |

|

|

|

The table specifies whether the information was collected from medical records ( ), parental self-administered questionnaire (

), parental self-administered questionnaire ( ), medical questionnaire (

), medical questionnaire ( ), medical examination (

), medical examination ( ), neuropsychological assessment (

), neuropsychological assessment ( ) or not collected at this follow-up (-).

) or not collected at this follow-up (-).

ASQ, Ages and Stages Questionnaire; IFDC, French Communicative Development Inventories (inventaires français du développement communicative, adapted from the MacArthur CDI—communicative development inventories); M-ABC2, Movement Assessment Battery for Children, 2nd edition; M-CHAT, Modified Checklist for Autism in Toddlers18; NEPSY 2, Developmental NEuroPSYchological Assessment, 2nd edition; PedsQL™, Pediatric Quality of life Inventory; SCQ, Social Communication Questionnaire; SDQ, Strengths and Difficulties Questionnaire; WPPSI-IV, Wechsler Preschool and Primary Scale of Intelligence, Fourth Edition.

Gestational age was estimated by obstetric teams, as part of routine care, based on the best obstetric estimate combining last menstrual period and early ultrasonography assessment.

Diagnosed according to the diagnostic criteria proposed by the Surveillance of Cerebral Palsy in Europe (SCPE) network.19 Functional abilities were investigated by using the Gross Motor Function Classification System (GMFCS)0.20

Including hospital admission.

Table 5.

Standardized scales used in the EPIPAGE-2 questionnaires

| Sweeps | Completeness | Validation in French | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Maternal health | |||

| Center for Epidemiologic Studies Depression Scale (CES-D)21 | Birth | Full version | Yes |

| State-Trait Anxiety Inventory for adults (STAI)22 | Birth | Full version | Yes |

| 36-items Short-Form Survey (SF-36)23 | Birth | Partial | Yes |

| 1 year | Partial/12 items | Yes | |

| 2 years | Partial/6 items | Yes | |

| 5.5 years | Partial/11 items | Yes | |

| Child’s health | |||

| Ages and Stages Questionnaire (ASQ)24 | 2 years | Full version | Yes |

| MacArthur-Bates Communication Development Inventories (CDI)25 | 2 years | Full version | Yes |

| Modified Checklist for Autism in Toddlers (M-CHAT)26 | 2 years | Full version | Yes |

| Wechsler Preschool and Primary Scale of Intelligence, 4th edition (WPPSI-IV) | 5.5 years | Full version | Yes |

| NEuroPSYchological assessment, 2nd edition (NEPSY 2)27 | 5.5 years | 8 subtestsa | Yes |

| Strengths and Difficulties Questionnaire (SDQ)28 | 5.5 years | Full version | Yes |

| Social Communication Questionnaire (SCQ)29 | 5.5 years | Full version | Yes |

| Movement Assessment Battery for Children, 2nd edition (MABC-2)30 | 5.5 years | Full version | Yes |

| Children's Eating Behaviour Questionnaire (CEBQ)31 | 5.5 years | Partial/19 items | No |

| Pediatric Quality of Life Inventory32 | 5.5 years | Partial/23 items | Yes |

| Home Observation for Measurement of the Environment (HOME) inventory-Short Form | 5.5 years | Partial/23 items | Yes |

Inhibition, statue, phonological processing, speed naming, comprehension of instructions, effect recognition, theory of mind, visuomotor precision.

Unit policies and practices

Another part of the EPIPAGE-2 study focused on the policies and practices of maternity and neonatal units. In 2012, questionnaires were sent to the medical teams of maternity and neonatal units to collect data on their structural characteristics, organization, and policies and practices related to medical interventions and decision-making processes. In total, 98% and 90% of type III and II maternity units and 100% and 98% of type III and II neonatal units, respectively, completed the questionnaire.

Linkage to routine data sources

Linkage with the national health insurance fund reimbursement register (SNIIRAM) at the individual level is ongoing for families who did not express opposition. It will provide information on prescribed medications since birth and visits to medical and other health care professionals, as well as hospital admissions and their causes. Similar data will be retrieved for the mother during pregnancy. Notably, the linkage will allow for passive follow-up of the children lost to follow-up as long as their parents have not explicitly asked to withdraw from the study.

Additional projects

The EPIPAGE-2 cohort has also allowed for setting up nine associated projects and two randomized controlled trials (Table 6). Benefiting from the cohort infrastructure, these projects were designed to test very specific associations or interventions in various areas. Accordingly, additional clinical and imaging data as well as biological samples have been collected (Table 6).

Table 6.

Additional projects nested in the EPIPAGE-2 cohort

| Projects | Objectives/number of included children | Funding | Age at material/data collection | Collected material/data |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| CHORHIST |

Histological chorioamnionitis and subsequent health outcomes N = 1406 |

EQUIPEX—ANR-11-EQPX-0038 | Birth | Histological data on placentas |

| EPIPPAIN 2 |

Painful procedures in NICU and subsequent neurodevelopment N = 562 |

Fondation CNP and Regional Hospital Clinical Research Program (PHRC), 2011 | Birth | Data on painful procedures in level-III neonatal care units |

| OLIMPE |

Early mother-infant interactions and attachment and subsequent development N = 167 |

Fondation de France, 2011 |

Birth, 6 months |

Data on mother-infant attachment |

| ETHICS |

Antenatal and postnatal decision-making processes regarding extremely preterm infants N = 419 |

Fondation de France, 2010 | Birth | Data on limitations of care |

| EPIRMEX |

Cerebral lesions detected by magnetic resonance imaging and development N = 313 |

National Hospital Clinical Research Program (PHRC) 2011 | Birth | Data from magnetic resonance imaging (n = 298) |

| EPINUTRI |

Neonatal nutrient intake and child development N = 325 |

National Hospital Clinical Research Program (PHRC) 2013 | Birth | Data on infant’s polyunsaturated fatty acids and iron intake |

|

1 year 3 years |

Data on child’s diet | |||

| EPIFLORE |

Intestinal microbiota and diseases of early childhood, childhood and adolescence N = 729 |

ANR 2013 | Birth | Infant stools (n = 720) |

| 3 years | Child stools (n = 212) | |||

| BIOPAG |

Biological markers and short- and long-term complications in children N = 163 |

EQUIPEX—ANR-11-EQPX-0038 | Birth |

Maternal blood (DNA, n = 148; RNA, n = 147) Cord blood (DNA, n = 163; RNA, n = 150) |

| EPIPAGE-2 | EQUIPEX—ANR-11-EQPX-0038 | 5.5 years | Saliva (n = 1335) | |

| EPIVAREC |

Influence of early nutritional practices in neonatology on children’s ‘metabolic’ status at 5.5 years and its link with growth trajectories N = 401 |

Nestlé | 5.5 years |

Child’s urine (n = 175) Data on body composition, pulse wave velocity, presence of micro-albuminuria ActiGraph-collected data |

| EPILANG |

Randomized controlled trial of a speech-language guidance program N = 52 |

ANR-13-APPR-0007 and National Hospital Clinical Research Program (PHRC) 2013 |

2 years 5.5 years |

Language score of the Developmental Neuropsychological Assessment (NEPSY) |

| EPIREMED |

Randomized controlled trial of cognitive training on visuospatial processing N = 170 |

National Hospital Clinical Research Program (PHRC) 2015 |

5 years 7 years |

Primary index scores of the Wechsler Preschool and Primary Scale of Intelligence (WPPSI IV) |

What has it found?

More than 50 articles based on EPIPAGE-2 data were published up to November 2020, including in collaboration with other cohorts. Details and updates of scientific publications can be found on the EPIPAGE-2 website [https://epipage2.inserm.fr/index.php/en/related-research/scientific-publications]. Some key results are summarized below.

Short- and mid-term health outcomes

Along with providing up-to-date estimates of health outcomes of preterm children, we have shown substantial improvements in both survival and survival without severe morbidity at discharge for newborns born at 25–31 weeks in 2011 compared with 1997.33 There was also an increased use of evidence-based practices known to be beneficial for the newborn (antenatal corticosteroids, surfactant etc.).33 These findings were confirmed at 2 years’ corrected age, with a significant increase in survival without severe or moderate neuromotor or sensory disabilities in 2011 compared with 1997.34 However, a high number of very and moderately preterm children remained at risk of developmental delay at 2 years of age, which underlines the need for formal developmental evaluations.34 The use of standardized parental assessments [Ages and Stages Questionnaire (ASQ), communicative development inventories (CDI)] was considered a valuable screening approach to allow referral of children to a professional if they might benefit from early interventions.34,35 However, this screening strategy will have to be validated with outcomes and specific needs at later stages.

Extreme prematurity (22–26 weeks)

Survival of extremely preterm children in France was lower than in several other developed countries because of less active antenatal and postnatal care.33,36–39 Moreover, infants born in type III hospitals with higher intensity of perinatal care showed improved survival at 2 years’ corrected age, with no increase in sensorimotor morbidity.40 Accordingly, French practices were reassessed and new recommendations were issued in 2020 by French medical associations.

Obstetric determinants of preterm children’s prognosis

Another major contribution of the EPIPAGE-2 cohort study has been to further study antenatal and obstetric predictors of child outcomes. We developed a new clinically relevant classification of causes of preterm birth,41 which was used to more accurately describe preterm newborns’ and children’s prognosis.42–44 Other studies have focused on specific pregnancy complications, their management and related health outcomes.45,46

Evaluation of medical interventions, unit policies and organization of care

EPIPAGE-2 gave us the opportunity to evaluate a large variety of non-consensual or controversial medical interventions and practices in a real-life setting. We have shown that tocolysis administration after preterm premature rupture of membranes (PPROM), although frequently used, was not associated with improved outcomes.47 In addition, planned cesarean section was not associated with improved neonatal and 2-year outcomes for preterm twins or preterm cephalic or breech singletons born after preterm labour or PPROM.48–50 The comparison of antenatal and postnatal assessments of fetal growth restriction revealed discordances for 14% of very preterm infants, birthweight being more relevant for identifying infants with increased risk.51

For infants born before 29 weeks, we showed that echocardiography screening before Day 3 of life was associated with lower in-hospital mortality,52 that treating isolated hypotension was associated with improved short-term outcomes53 and that early extubation was not associated with an increased risk of intraventricular haemorrhage.54

A slow progression of enteral feeding and a less favourable direct-breastfeeding unit policy, as well as some specific microbiota patterns, were associated with the development of necrotizing enterocolitis.55 There were large variations in breastfeeding at discharge, regardless of individual factors, which were partly explained by unit policies, suggesting that improvements in unit policies could result in increasing breastfeeding rates.56,57

Neurodevelopmental care implementation is advocated by parent associations. We investigated its dissemination in French neonatal intensive care units (NICUs), showing the essential role of unit policies and the beneficial impact of structured programmes, such as the Newborn Individualized Developmental Care and Assessment Program (NIDCAP), on this dissemination.58,59

We also explored the regionalization of care, showing lower NICU volume associated with lower survival, with no difference in disabilities at 2 years.60

Collaborations

Besides being a very federative project for French clinicians and researchers, the large array of clinical data and biological material collected in the EPIPAGE-2 cohort has led to a number of national and international collaborations.

At the national level, EPIPAGE-2 is closely associated with the ELFE birth cohort [https://www.elfe-france.fr/], whose 18 000 children born at term or near term in France in 2011 serve as a comparison group for some research questions, owing to the collection of similar data.61 These two cohorts led to the creation of the RE-CO-NAI research platform, which provides researchers with a database for 22 500 children.

EPIPAGE-2 is part of three projects conducted within the European Union’s Seventh Framework and Horizon 2020 research and innovation programmes: EPICE (Effective Perinatal Intensive Care in Europe, [https://www.epiceproject.eu],62 SHIPS (Screening to Improve Health in Preterm Infants in Europe), and RECAP-preterm (Research on European Children and Adults born Preterm, [https://recap-preterm.eu/]). International comparisons of practices and outcomes were also initiated.63

The variability of practices and health outcomes described in EPIPAGE-2 has led to setting up multidisciplinary working groups, gathering stakeholders from the French perinatal community and parent associations, aiming at fostering strategies at the national level regarding the perinatal management of extremely preterm babies or the dissemination of neurodevelopmental care. Findings were also used to update French guidelines for clinical practice.64,65

What are the main strengths and weaknesses?

Strengths include the large size of the cohort, the population-based design at a national level and the prospective enrolment and longitudinal follow-up of infants born preterm. To the best of our knowledge, there is no comparable study covering a broad spectrum of preterm infants from the limits of viability to moderate prematurity. This multidisciplinary project offers an extensive variety of data, enriched by the use of standardized definitions and measures and the collection of biological samples, imaging data and parents’ perceptions of their children’s care and development. The use of standardized tools at the national level to assess development at 5.5 years contributes to harmonizing practices and increasing the quality of evaluations in everyday practice. Moreover, individual-level outcomes and unity policies can be studied simultaneously, in a public health approach.

However, because of its observational nature, establishing causation is sometimes difficult, which is mitigated by the use of adapted statistical methods. Refusal at baseline and attrition over time can lead to selection bias, although families have demonstrated their commitment to collaborating with us. We found a social bias in participation, at baseline and over the years, leading to an under-representation of children from families with disadvantaged socioeconomic positions, as commonly described in other cohorts.61 This will hopefully be mitigated by passive data collection through linkage with data from the national health insurance fund reimbursement register. Unfortunately, only few data were collected about fathers and their health. Our sample size is sometimes a limitation to studying rare diseases, which reinforces the need to pool data with other cohort studies. Finally, the costs and organizational challenges are a major obstacle to the cohort’s sustainability, although following these families until adulthood would be of invaluable interest.

Can I get hold of the data? Where can I find out more?

EPIPAGE-2 was conceived as a research platform to serve the national and international scientific community, with an open data access policy under conditions that ensure data security and confidentiality. To date, data have been requested for 117 projects from 17 different French research institutes or universities and two international projects. Our longitudinal dataset has great potential for collaborations and other secondary analyses. We therefore welcome proposals for data access. The data are accessible to all research teams, French or foreign. The study protocol and the data access procedure can be found on the EPIPAGE-2 website [https://epipage2.inserm.fr/index.php/en/related-research/access-to-epipage-2-data]. Questionnaires and data catalogues are available on the Pandora platform [https://pandora-epipage2.inserm.fr/public/]. All requests are evaluated by the EPIPAGE-2 Data Access Committee and approved on the basis of scientific quality. A contract is signed for each data sharing. Data are usually transferred to French teams within 1 month of the proposal submission. This time frame may be longer for international teams due to the need to establish data-sharing agreements. A specific procedure for ELFE—EPIPAGE-2 joint projects is described at [https://epipage2.inserm.fr/index.php/en/related-research/access-to-epipage-2-data]. Further enquiries should be submitted to Prof. Ancel, contact e-mail: [accesdonnees.epipage@inserm.fr].

Key Features

Etude Epidémiologique sur les Petits Ages Gestationnels-2 (EPIPAGE-2) is a population-based birth cohort of extremely, very and moderately preterm infants, aiming at estimating short- and long-term outcomes and their association with individual characteristics and unit practices.

Preterm births (terminations of pregnancy, stillbirths and live births) from 22 + 0 to 34 + 6 weeks’ gestation, and occurring in all maternity units of 25/26 regions in France in 2011, were eligible. A total of 7804 newborns were included at baseline (participation rate 93%), and 4312 were eligible for follow-up.

From 2011 to 2017, three follow-up steps have been performed: at 1-year corrected age (parental self-administered questionnaire, participation 90%) and 2-year corrected age (parental self-administered questionnaire, 88%, medical questionnaire, 86%). At 5.5 years, 3032 children were still followed; the evaluation consisted of a parental questionnaire (77%), a standardized medical examination (68%) and a neuropsychological assessment (67%).

Detailed information was collected on maternal sociodemographic characteristics, living conditions, health and pregnancy management and complications. Regarding the child, the main domains assessed were health, health care use, nutrition and growth, gross and fine motor skills, cognitive functions, language, behaviour, quality of life and school attendance. Additional data on policies and practices of maternity and neonatal units were also collected.

Proposals for collaborations and secondary analyses are welcomed. Data access procedures can be found on the EPIPAGE-2 website [https://epipage2.inserm.fr/index.php/en/related-research/access-to-epipage-2-data].

Funding

The French National Institute of Public Health Research (IRESP TGIR 2009–01 programme)/Institute of Public Health and its partners [the French Health Ministry, the National Institute of Health and Medical Research (INSERM), the National Institute of Cancer, the National Solidarity Fund for Autonomy (CNSA)], the National Research Agency through the French EQUIPEX programme of investments for the future (grant no. ANR-11-EQPX-0038) and the PremUp Foundation. Additional funding was obtained from the Fondation pour la Recherche Medicale (SPF 20160936356) and Fondation de France [00050329 and R18202KK (Grand Prix)].

Acknowledgements

We are grateful to the participating children and their families, all maternity and neonatal units in France and all national and regional collaborators who made EPIPAGE 2 possible. The authors thank Laura Smales for editorial assistance and acknowledge the collaborators of the EPIPAGE-2 Study Group: Alsace: D Astruc, P Kuhn, B Langer, J Matis, C Ramousset; Aquitaine: X Hernandorena, P Chabanier, L Joly-Pedespan, M Rebola, M J Costedoat, A Leguen, C Martin; Auvergne: B Lecomte, D Lemery, F Vendittelli, E Rochette; Basse-Normandie: G Beucher, M Dreyfus, B Guillois, Y Toure, D Rots; Bourgogne: A Burguet, S Couvreur, J B Gouyon, P Sagot, N Colas, A Franzin; Bretagne: J Sizun, A Beuchée, P Pladys, F Rouget, R P Dupuy, D Soupre, F Charlot, S Roudaut; Centre: A Favreau, E Saliba, L Reboul, E Aoustin; Champagne-Ardenne: N Bednarek, P Morville, V Verrière; Franche-Comté: G Thiriez, C Balamou, C Ratajczak; Haute-Normandie: L Marpeau, S Marret, C Barbier, N Mestre; Ile-de-France: G Kayem, X Durrmeyer, M Granier, A Lapillonne, M Ayoubi, O Baud, B Carbonne, L Foix L’Hélias, F Goffinet, P H Jarreau, D Mitanchez, P Boileau, C Duffaut, E Lorthe, L Cornu, R Moras, D Salomon, S Medjahed, K Ahmed; Languedoc-Roussillon: P Boulot, G Cambonie, H Daudé, A Badessi, N Tsaoussis, M Poujol; Limousin: A Bédu, F Mons, C Bahans; Lorraine: M H Binet, J Fresson, J M Hascoët, A Milton, O Morel, R Vieux, L Hilpert; Midi-Pyrénées: C Alberge, C Arnaud, C Vayssière, M Baron; Nord-Pas-de-Calais: M L Charkaluk, V Pierrat, D Subtil, P Truffert, S Akowanou, D Roche, M Thibaut; PACA et Corse: C D’Ercole, C Gire, U Simeoni, A Bongain, M Deschamps, M Zahed; Pays de Loire: B Branger, J C Rozé, N Winer, G Gascoin, L Sentilhes, V Rouger, C Dupont, H Martin; Picardie: J Gondry, G Krim, B Baby, I Popov; Rhône-Alpes: M Debeir, O Claris, J C Picaud, S Rubio-Gurung, C Cans, A Ego, T Debillon, H Patural, A Rannaud; Guadeloupe: E Janky, A Poulichet, J M Rosenthal, E Coliné, C Cabrera; Guyane: A Favre, N Joly, A Stouvenel; Martinique: S Châlons, J Pignol, P L Laurence, V Lochelongue; La Réunion: P Y Robillard, S Samperiz, D Ramful. Inserm UMR 1153: P Y Ancel, H Asadullah, V Benhammou, B Blondel, M Bonet, A Brinis, M L Charkaluk, A Coquelin, V Delormel, M Durox, S Esmiol, M Fériaud, L Foix-L’Hélias, F Goffinet, M Kaminski, G Kayem, K Khemache, B Khoshnood, C Lebeaux, E Lorthe, L Marchand-Martin, L Onestas, V Pierrat, M Quere, J Rousseau, A Rtimi, M J Saurel-Cubizolles, D Tran, D Sylla, L Vasante-Annamale, J Zeitlin.

Conflict of interest

None declared.

Contributor Information

the EPIPAGE-2 Study group:

D Astruc, P Kuhn, B Langer, J Matis, C Ramousset, X Hernandorena, P Chabanier, L Joly-Pedespan, M Rebola, M J Costedoat, A Leguen, C Martin, B Lecomte, D Lemery, F Vendittelli, E Rochette, G Beucher, M Dreyfus, B Guillois, Y Toure, D Rots, A Burguet, S Couvreur, J B Gouyon, P Sagot, N Colas, A Franzin, J Sizun, A Beuchée, P Pladys, F Rouget, R P Dupuy, D Soupre, F Charlot, S Roudaut, A Favreau, E Saliba, L Reboul, E Aoustin, N Bednarek, P Morville, V Verrière, G Thiriez, C Balamou, C Ratajczak, L Marpeau, S Marret, C Barbier, N Mestre, G Kayem, X Durrmeyer, M Granier, A Lapillonne, M Ayoubi, O Baud, B Carbonne, L Foix L’Hélias, F Goffinet, P H Jarreau, D Mitanchez, P Boileau, C Duffaut, E Lorthe, L Cornu, R Moras, D Salomon, S Medjahed, K Ahmed, P Boulot, G Cambonie, H Daudé, A Badessi, N Tsaoussis, M Poujol, A Bédu, F Mons, C Bahans, M H Binet, J Fresson, J M Hascoët, A Milton, O Morel, R Vieux, L Hilpert, C Alberge, C Arnaud, C Vayssière, M Baron, M L Charkaluk, V Pierrat, D Subtil, P Truffert, S Akowanou, D Roche, M Thibaut, C D’Ercole, C Gire, U Simeoni, A Bongain, M Deschamps, M Zahed, B Branger, J C Rozé, N Winer, G Gascoin, L Sentilhes, V Rouger, C Dupont, H Martin, J Gondry, G Krim, B Baby, I Popov, M Debeir, O Claris, J C Picaud, S Rubio-Gurung, C Cans, A Ego, T Debillon, H Patural, A Rannaud, E Janky, A Poulichet, J M Rosenthal, E Coliné, C Cabrera, A Favre, N Joly, A Stouvenel, S Châlons, J Pignol, P L Laurence, V Lochelongue, P Y Robillard, S Samperiz, D Ramful, P Y Ancel, H Asadullah, V Benhammou, B Blondel, M Bonet, A Brinis, M L Charkaluk, A Coquelin, V Delormel, M Durox, S Esmiol, M Fériaud, L Foix-L’Hélias, F Goffinet, M Kaminski, G Kayem, K Khemache, B Khoshnood, C Lebeaux, E Lorthe, L Marchand-Martin, L Onestas, V Pierrat, M Quere, J Rousseau, A Rtimi, M J Saurel-Cubizolles, D Tran, D Sylla, L Vasante-Annamale, and J Zeitlin

References

- 1. Blencowe H, Cousens S, Oestergaard MZ. et al. National, regional, and worldwide estimates of preterm birth rates in the year 2010 with time trends since 1990 for selected countries: a systematic analysis and implications. Lancet 2012;379:2162–72. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Chawanpaiboon S, Vogel JP, Moller A-B. et al. Global, regional, and national estimates of levels of preterm birth in 2014: a systematic review and modelling analysis. Lancet Glob Health 2018;7:e37–46. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Blondel B, Lelong N, Kermarrec M, Goffinet F; National Coordination Group of the National Perinatal Surveys. Trends in perinatal health in France from 1995 to 2010. Results from the French National Perinatal Surveys. J Gynécologie Obstétrique Biol Reprod 2012;41:e1–15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Liu L, Oza S, Hogan D. et al. Global, regional, and national causes of child mortality in 2000–13, with projections to inform post-2015 priorities: an updated systematic analysis. Lancet 2015;385:430–40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Saigal S, Doyle LW.. An overview of mortality and sequelae of preterm birth from infancy to adulthood. Lancet 2008;371:261–69. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Costeloe K, Hennessy E, Gibson AT, Marlow N, Wilkinson AR ; Group for the EpicS. The EPICure study: outcomes to discharge from hospital for infants born at the threshold of viability. Pediatrics 2000;106:659–71. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. EXPRESS GroupFellman V, Hellström-Westas L. et al. One-year survival of extremely preterm infants after active perinatal care in Sweden. JAMA 2009;301:2225–33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Vanhaesebrouck P, Allegaert K, Bottu J. et al. The EPIBEL study: outcomes to discharge from hospital for extremely preterm infants in Belgium. Pediatrics 2004;114:663–75. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Marlow N, Bennett C, Draper ES, Hennessy EM, Morgan AS, Costeloe KL.. Perinatal outcomes for extremely preterm babies in relation to place of birth in England: the EPICure 2 study. Arch Dis Child Fetal Neonatal Ed 2014;99:F181–88. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Kramer MS, Demissie K, Yang H, Platt RW, Sauvé R, Liston R.. The contribution of mild and moderate preterm birth to infant mortality. Fetal and Infant Health Study Group of the Canadian Perinatal Surveillance System. JAMA 2000;284:843–49. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Cheong JLY, Doyle LW.. Increasing rates of prematurity and epidemiology of late preterm birth. J Paediatr Child Health 2012;48:784–88. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Larroque B. EPIPAGE: epidemiologic study of very premature infants. Protocol of the survey.] Arch Pediatr Organe off Soc Francaise Pediatr 2000;7:339s–42s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Larroque B, Ancel P-Y, Marret S. et al. Neurodevelopmental disabilities and special care of 5-year-old children born before 33 weeks of gestation (the EPIPAGE study): a longitudinal cohort study. Lancet 2008;371:813–20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Larroque B, Ancel P-Y, Marchand-Martin L. et al. Special care and school difficulties in 8-year-old very preterm children: the Epipage cohort study. PloS One 2011;6:e21361. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Torchin H, Ancel P-Y. [Epidemiology and risk factors of preterm birth]. J Gynecol Obstet Biol Reprod (Paris) 2016 Dec;45:1213–30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Draper ES, Manktelow BN, Cuttini M. et al. Variability in very preterm stillbirth and in-hospital mortality across Europe. Pediatrics 2017;139:e20161990. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Ancel P-Y, Goffinet F; EPIPAGE 2 Writing Group. EPIPAGE 2: a preterm birth cohort in France in 2011. BMC Pediatr 2014;14:97.. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Robins DL, Fein D, Barton ML, Green JA.. The modified checklist for Autism in Toddlers: an initial study investigating the early detection of autism and pervasive developmental disorders. J Autism Dev Disord 2001;31:131–44. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Cans C. Surveillance of cerebral palsy in Europe: a collaboration of cerebral palsy surveys and registers. Dev Med Child Neurol 2000;42:816–24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Ghassabian A, Sundaram R, Bell E, Bello SC, Kus C, Yeung E.. Gross motor milestones and subsequent development. Pediatrics 2016;138:e20154372. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Radloff LS. The CES-D scale: a self-report depression scale for research in the general population. Appl Psychol Meas 1977;1:385–40 [Google Scholar]

- 22. Spielberger CD. State-Trait Anxiety Inventory. In: The Corsini Encyclopedia of Psychology. Atlanta, GA: American Cancer Society, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 23. Jenkinson C, Coulter A, Wright L.. Short form 36 (SF36) health survey questionnaire: normative data for adults of working age. BMJ 1993;306:1437–40. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Flamant C, Branger B, Nguyen The Tich S. et al. Parent-completed developmental screening in premature children: a valid tool for follow-up programs. PLoS One 2011;6:e20004.. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Kern S, Langue J, Zesiger P, Bovet Boone F.. Adaptations françaises des versions courtes des inventaires du développement communicatif de MacArthur-Bates [French adaptations of short versions of MacArthur-Bates communicative inventories]. Approche Neuropsychol Apprentiss Chez Enfant 2010;107/108;217–28 [Google Scholar]

- 26. Chlebowski C, Robins DL, Barton ML, Fein D.. Large-scale use of the modified checklist for autism in low-risk toddlers. Pediatrics 2013;131:e1121–27. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Korkman M, Kemp SL, Kirk U, Lepoutre D. . Éditions du Centre de psychologie appliquée (Paris) [NEPSY-II]. Montreuil, France: ECPA, Pearson, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 28. Goodman R, Scott S.. Comparing the Strengths and Difficulties Questionnaire and the Child Behavior Checklist: is small beautiful? J Abnorm Child Psychol 1999;27:17–24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Chandler S, Charman T, Baird G. et al. Validation of the social communication questionnaire in a population cohort of children with autism spectrum disorders. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry 2007;46:1324–32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Smits-Engelsman BC, Fiers MJ, Henderson SE, Henderson L.. Interrater reliability of the Movement Assessment Battery for Children. Phys Ther 2008;88:286–94. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Musher-Eizenman DR, de Lauzon-Guillain B, Holub SC, Leporc E, Charles MA.. Child and parent characteristics related to parental feeding practices. A cross-cultural examination in the US and France. Appetite 2009;52:89–95. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Varni JW, Seid M, Kurtin PS.. PedsQL 4.0: reliability and validity of the Pediatric Quality of Life Inventory version 4.0 generic core scales in healthy and patient populations. Med Care 2001;39:800–12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Ancel P-Y, Goffinet FEPIPAGE-2 Writing Group, et al. Survival and morbidity of preterm children born at 22 through 34 weeks’ gestation in France in 2011: results of the EPIPAGE-2 cohort study. JAMA Pediatr 2015;169:230–38. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Pierrat V, Marchand-Martin L, Arnaud C. et al. Neurodevelopmental outcome at 2 years for preterm children born at 22 to 34 weeks’ gestation in France in 2011: EPIPAGE-2 cohort study. BMJ 2017 16;358:j3448. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Charkaluk M-L, Rousseau J, Benhammou V. et al. Association of language skills with other developmental domains in extremely, very, and moderately preterm children: EPIPAGE 2 cohort study. J Pediatr 2019;208:114–20.e5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Perlbarg J, Ancel PY, Khoshnood B. et al. Delivery room management of extremely preterm infants: the EPIPAGE-2 study. Arch Dis Child Fetal Neonatal Ed 2016;101:F384–90. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Diguisto C, Goffinet F, Lorthe E. et al. Providing active antenatal care depends on the place of birth for extremely preterm births: the EPIPAGE 2 cohort study. Arch Dis Child Fetal Neonatal Ed 2017;102:F476–82. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Diguisto C, Foix L'Helias L, Morgan AS. et al. Neonatal outcomes in extremely preterm newborns admitted to intensive care after no active antenatal management: a population-based cohort study. J Pediatr 2018;203:150–55. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Durrmeyer X, Scholer-Lascourrèges C, Boujenah L. et al. ; the EPIPAGE-2 Extreme Prematurity Writing Group. Delivery room deaths of extremely preterm babies: an observational study. Arch Dis Child Fetal Neonatal Ed 2017;102:F98–103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Morgan AS, Foix L’Helias L, Diguisto C. et al. Intensity of perinatal care, extreme prematurity and sensorimotor outcome at 2 years corrected age: evidence from the EPIPAGE-2 cohort study. BMC Med 2018;16:227. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Delorme P, Goffinet F, Ancel P-Y. et al. Cause of Preterm Birth as a Prognostic Factor for Mortality. Obstet Gynecol 2016;127:40–48. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Torchin H, Ancel P-Y, Goffinet F. et al. Placental complications and bronchopulmonary dysplasia: EPIPAGE-2 cohort study. Pediatrics 2016;137:e20152163.. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Torchin H, Lorthe E, Goffinet F. et al. Histologic chorioamnionitis and bronchopulmonary dysplasia in preterm infants: the epidemiologic study on low gestational ages 2 cohort. J Pediatr 2017;187:98–104.e3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Chevallier M, Debillon T, Pierrat V. et al. Leading causes of preterm delivery as risk factors for intraventricular hemorrhage in very preterm infants: results of the EPIPAGE 2 cohort study. Am J Obstet Gynecol 2017;216:518.e1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Lorthe E, Torchin H, Delorme P. et al. Preterm premature rupture of membranes at 22–25 weeks’ gestation: perinatal and 2-year outcomes within a national population-based study (EPIPAGE-2. ). Am J Obstet Gynecol 2018;219:298.e1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Monier I, Ancel P-Y, Ego A. et al. ; EPIPAGE 2 Study Group. Gestational age at diagnosis of early-onset fetal growth restriction and impact on management and survival: a population-based cohort study. BJOG 2017;124:1899–906. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Lorthe E, Goffinet F, Marret S. et al. Tocolysis after preterm premature rupture of membranes and neonatal outcome: a propensity-score analysis. Am J Obstet Gynecol 2017;217:212.e1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Lorthe E, Sentilhes L, Quere M. et al. Planned delivery route of preterm breech singletons, and neonatal and 2-year outcomes: a population-based cohort study. BJOG 2019;126:73–82. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Sentilhes L, Lorthe E, Marchand-Martin L. et al.,; for the Etude Epidémiologique sur les Petits Ages Gestationnels (EPIPAGE) 2 Obstetric Writing Group. Planned Mode of Delivery of Preterm Twins and Neonatal and 2-Year Outcomes. Obstet Gynecol 2019;133:71–80. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Gaudineau A, Lorthe E, Quere M. et al. Planned delivery route and outcomes of cephalic singletons born spontaneously at 24-31 weeks’ gestation: The EPIPAGE-2 cohort study. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand 2020;99:1682–90. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Monier I, Ancel P-Y, Ego A. et al. Fetal and neonatal outcomes of preterm infants born before 32 weeks of gestation according to antenatal vs postnatal assessments of restricted growth. Am J Obstet Gynecol 2017;216:516.e1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Rozé J-C, Cambonie G, Marchand-Martin L. et al. Association Between Early Screening for Patent Ductus Arteriosus and In-Hospital Mortality Among Extremely Preterm Infants. JAMA 2015;313:2441–48. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Durrmeyer X, Marchand-Martin L, Porcher R. et al. Abstention or intervention for isolated hypotension in the first 3 days of life in extremely preterm infants: association with short-term outcomes in the EPIPAGE 2 cohort study. Arch Dis Child Fetal Neonatal Ed 2017;102:490–96. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Chevallier M, Ancel P-Y, Torchin H. et al. Early extubation is not associated with severe intraventricular hemorrhage in preterm infants born before 29 weeks of gestation. Results of an EPIPAGE-2 cohort study. PLoS One 2019;14:e0214232.. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Rozé J-C, Ancel P-Y, Lepage P. et al. Nutritional strategies and gut microbiota composition as risk factors for necrotizing enterocolitis in very-preterm infants. Am J Clin Nutr 2017;106:821–30. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Mitha A, Piedvache A, Glorieux I. et al. Unit policies and breast milk feeding at discharge of very preterm infants: The EPIPAGE-2 cohort study. Paediatr Perinat Epidemiol 2019;33:59–69. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Mitha A, Piedvache A, Khoshnood B. et al. The impact of neonatal unit policies on breast milk feeding at discharge of moderate preterm infants: the EPIPAGE-2 cohort study. Matern Child Nutr 2019;15:e12875.. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Pierrat V, Coquelin A, Cuttini M. et al. Translating Neurodevelopmental Care Policies Into Practice: The Experience of Neonatal ICUs in France—The EPIPAGE-2 Cohort Study. Pediatr Crit Care Med 2016;17:957–67. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59. Pierrat V, Marchand-Martin L, Durrmeyer X. et al. Perceived maternal information on premature infant’s pain during hospitalization: the French EPIPAGE-2 national cohort study. Pediatr Res 2020;87:153–62. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60. Desplanches T, Blondel B, Morgan AS. et al. Volume of neonatal care and survival without disability at 2 years in very preterm infants: results of a French National Cohort Study. J Pediatr 2019;213:22–29.e4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61. Charles MA, Thierry X, Lanoe J-L. et al. Cohort Profile: The French National cohort of children ELFE: birth to 5 years. Int J Epidemiol 2020;49:368–69j. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62. Zeitlin J, Maier RF, Cuttini M. et al. Cohort Profile: Effective Perinatal Intensive Care in Europe (EPICE) very preterm birth cohort. Int J Epidemiol 2020;49:372–86. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63. Wang D, Yasseen AS, Marchand-Martin L. et al. A population-based comparison of preterm neonatal deaths (22–34 gestational weeks) in France and Ontario: a cohort study. CMAJ Open 2019;7:E159–66. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64. Sentilhes L, Sénat M-V, Ancel P-Y. et al. Prevention of spontaneous preterm birth: guidelines for clinical practice from the French College of Gynaecologists and Obstetricians (CNGOF). Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol 2017;210:217–24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65. Schmitz T, Sentilhes L, Lorthe E. et al. Preterm premature rupture of the membranes: guidelines for clinical practice from the French College of Gynaecologists and Obstetricians (CNGOF). Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol 2019;236:1–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]