Dark matter interpretations of the DAMA signals are excluded by COSINE-100 with the same NaI(Tl) target for various models.

Abstract

We present new constraints on dark matter interactions using 1.7 years of COSINE-100 data. The COSINE-100 experiment, consisting of 106 kg of tallium-doped sodium iodide [NaI(Tl)] target material, is aimed to test DAMA’s claim of dark matter observation using the same NaI(Tl) detectors. Improved event selection requirements, a more precise understanding of the detector background, and the use of a larger dataset considerably enhance the COSINE-100 sensitivity for dark matter detection. No signal consistent with the dark matter interaction is identified and rules out model-dependent dark matter interpretations of the DAMA signals in the specific context of standard halo model with the same NaI(Tl) target for various interaction hypotheses.

INTRODUCTION

Astronomical observations continue to indicate that the Universe is made mostly of nonluminous and invisible dark matter (1, 2). Several types of new fundamental particles have been proposed as candidates for the dark matter (3) such as weakly interacting massive particles (WIMPs) (4, 5), but no definitive signal has been seen despite concerted efforts by many collaborations (6). One exception is the much-debated claim by the DAMA collaboration of a statistically significant annual modulation in the event rate of their experiment (7–9) with a period and phase consistent with that expected from WIMP dark matter (10–12). This is controversial because if it is interpreted as a signature for WIMP interactions, it conflicts with other direct search experiments (13–15) that report null signals in the regions of parameter space that are allowed by the DAMA signals.

Several groups have been working to develop new experiments with the aim of reproducing or refuting DAMA’s results using the same NaI(Tl) medium (16–20). The COSINE-100 experiment is one of them and that is currently operating with 106 kg of low-background sodium iodide crystals at the Yangyang Underground Laboratory (21, 22). An analysis of the initial 59.5 days of COSINE-100 data showed that the annual modulation signal reported by DAMA is inconsistent with the explanation using SI interaction between WIMPs and sodium or iodine nuclei in the context of the standard halo model (SHM) (21). However, this first result left open interpretations using certain alternative dark matter models (23, 24), dark matter halo distributions (25), and detector responses (25, 26) that could allow room for consistency between DAMA and COSINE-100. Model-independent searches of an annual modulation signal using 1.7-years data were also reported but were still not sensitive enough to conclusively challenge the DAMA observation (22). Here, we present results from an analysis of 1.7 years of COSINE-100 data with improved event selection requirements and an energy threshold that has been reduced from 2 to 1 keVee, where keVee is electron-equivalent energy (27). We find an order-of-magnitude improvement in sensitivity, sufficient to strongly constrain these alternative scenarios, as well as to further strengthen the previously observed inconsistency with the WIMP-nucleon spin-independent interaction hypothesis (21).

RESULTS

Experiment

COSINE-100 is located at the Yangyang Underground Laboratory in South Korea with a 700-m rock overburden (21, 22). The experiment consists of eight low-background thallium-doped sodium iodide [NaI(Tl)] crystals arranged in a 4 × 2 array with a total target mass of 106 kg. The array is immersed in 2200 liters of liquid scintillator used to identify events induced by radioactive backgrounds inside or outside the crystals (28). The liquid scintillator is surrounded by copper, lead, and plastic scintillators to reduce the background contribution from external radiation as well as to tag and reject events associated with cosmic-ray muons (29). Each NaI(Tl) crystal is optically coupled to two photomultiplier tubes (PMTs) with the signals recorded as 8-μs waveforms. A trigger is generated when a signal corresponding to one or more photoelectrons occurs in each PMT within a 200-ns time window (30).

The analysis presented here uses 1.7 years of data, previously used for the first annual modulation search (22), and background modeling with 1-keVee energy threshold (31). The data were acquired between 21 October 2016 and 18 July 2018. Three of the eight crystals were observed to have high noise rates in the region of interest (ROI) and so were excluded from the analysis, resulting in an effective data exposure of 97.7 kg × year (21, 22).

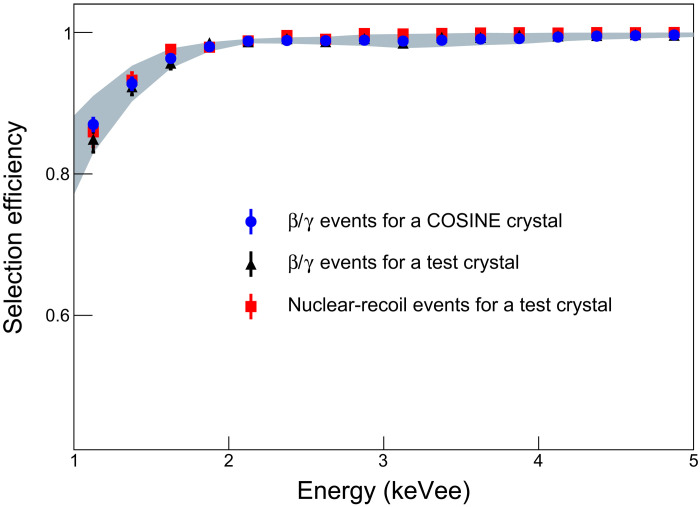

In the ROI, it was found that PMT noise causes most of the triggers. A multivariable boosted decision tree (BDT) (32) was used to characterize the pulse shapes to discriminate these PMT-induced noise events from radiation-induced scintillation events (21, 22). To improve the discrimination power, a likelihood score was introduced as an input training variable to the BDT, which rates how well the waveform matches either scintillation events or PMT-induced noise events. The likelihood score particularly enhances the removal of noise pulses and allows us to achieve a 1-keVee threshold (27). The BDT is trained with samples of scintillation-rich 60Co calibration data and PMT noise–dominant single-hit physics data. The multiple-hit events consist of hits in multiple crystals or liquid scintillator that cannot be caused by dark matter interactions. The event selection efficiencies for scintillation events are evaluated with the 60Co calibration dataset and cross-checked with the physics data, as well as nuclear recoil events. The efficiencies from the 60Co calibration data were found to be consistent with previously measured efficiencies for nuclear recoil events obtained using a monoenergetic 2.42-MeV neutron beam (33) as shown in Fig. 1. The efficiency differences and their uncertainties are included as a systematic uncertainty.

Fig. 1. Efficiencies for β/γ and nuclear-recoil events.

Blue dots show the efficiencies for β/γ events for a COSINE-100 crystal. Black and red dots are efficiencies of β/γ and nuclear recoil events, respectively, for a small-size test crystal. This test crystal was cut from the same ingot of the COSINE-100 crystal and used for the neutron beam measurement. All measurements are consistent within the systematic uncertainty of the efficiency shown in the gray band.

Background modeling

Events in the remaining dark matter search dataset predominantly originate from environmental γ and β radiations. Sources include radioactive contaminants internal to the crystals or on their surfaces, external detector components, and cosmogenic activation (31). To understand this, the background spectrum for each crystal is modeled using computer simulations based on the Geant4 toolkit (34).

Events are classified according to their energy: 1 to 70 keVee are low energy and 70 to 3000 keVee are high energy. The single-hit and multiple-hit data are separated in the background modeling of the NaI(Tl) crystals. To understand background spectra, Geant4-based simulation events are generated and recorded in a format that matches that of the COSINE-100 data acquisition system. Energy resolutions and selection efficiencies for each crystal are applied. The fraction of each background component is determined from a simultaneous fit to the four measured distributions. For the single-hit events, only 6 to 3000 keVee events are used to avoid a bias of the WIMP signal in the ROI. Details of the background modeling for the dataset are described elsewhere (31).

The background components are divided into four categories: internal contamination, surface contamination, external sources, and cosmogenic activation. The 238U, 232Th, 40K, and 210Pb contaminations in the crystal constitute the internal background. The 210Pb contaminations on the crystal surface and adjacent materials are the surface component. Backgrounds from 238U, 232Th, and 40K in the PMTs, liquid scintillator, and the shield materials constitute external sources. To estimate contributions from cosmogenic activation, we use a time-dependent analysis that takes into account the cosmic-ray exposure time on the ground and the cooling time in the underground laboratory of each crystal (35).

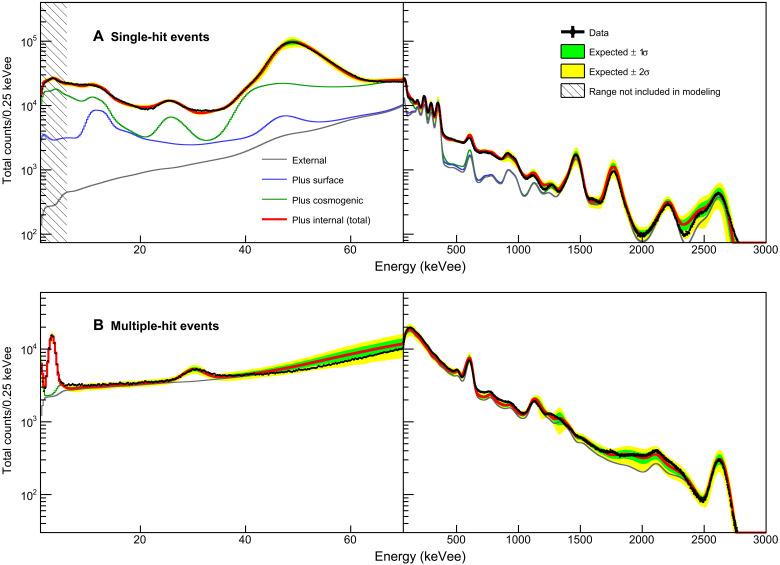

The most dominant background components in the ROI are generated by internal radionuclide contamination and by cosmogenic activation. This includes 210Pb and 40K internal contaminants and 210Pb surface contamination. The contribution to the ROI from cosmogenic activation is mostly due to 3H with some additional contributions from 113Sn and 109Cd. Background modeling was performed independently for each crystal, and Fig. 2 shows the accumulated result of the model fit to data and the systematic uncertainties.

Fig. 2. Energy spectra.

Single-hit (A) and multiple-hit (B) data presented here are summed energy spectra for the five crystals (black dots) and their background modeling (red solid line) with the 68 and 95% confidence intervals. The expected contributions to the background from internal radionuclide contaminations, the surface of the crystals and nearby materials, cosmogenic activation, and external backgrounds are indicated. The 1- to 6-keV region of the single-hit spectrum is masked because these events are not used for the background modeling.

Several sources of systematic uncertainties are identified and included in this analysis. The largest systematic uncertainties are those associated with the efficiencies, which include statistical errors in the efficiency determinations with the 60Co calibration and systematic errors derived from the independent cross-checks of the physics data and the nuclear recoil events. Uncertainties in the energy resolution and nonlinear responses of the NaI(Tl) crystals (36) affect the shapes of the background and signal spectra. The depth profiles of 210Pb on the surface of the NaI(Tl) crystals, studied with a 222Rn-contaminated crystal, are varied within their uncertainty (37). Variations in the levels and the positions of external uranium and thorium decay-chain contaminants are also taken into account. Effects of event rate variations and possible distortions in the shapes of spectra are considered in systematic uncertainties.

Dark matter interpretations

We consider various WIMP models to determine the possible contribution from WIMP interactions to the measured energy spectra using the simulated data. The DAMA/LIBRA-phase2 data (9) were found not to be compatible with the canonical model (11, 26), which is an isospin-conserving spin-independent interaction between WIMP and nucleus in the specific context of the standard WIMP galactic halo model and is the most commonly used interpretation of the direct detection of the WIMP dark matter (38). However, an isospin-violating interaction in which the WIMP-proton coupling is different from the WIMP-neutron coupling provides a good fit to the observed annual modulation signals from the DAMA/LIBRA-phase2 data (11, 26). To interpret the DAMA/LIBRA data and compare with the COSINE-100 data, we use the best-fit values of the effective coupling of WIMPs to neutrons and to protons (fn/fp) obtained for the simultaneous fit of DAMA/LIBRA-phase1 and DAMA/LIBRA-phase2 data described elsewhere (26). We also interpret the results of the COSINE-100 data in the canonical model for the comparison with the DAMA/LIBRA-phase1–only data.

We use the nuclear recoil quenching factor (QF) from recent measurements with monoenergetic neutron beams (33) (QF is the ratio of the scintillation light yield from sodium or iodine recoil relative to that for electron recoil for the same energy). In those measurements, neutron-tagging detectors at a fixed angle relative to the incoming neutron beam direction provide unambiguous knowledge of deposited energy. We obtained a strong energy dependence of the nuclear recoil QFs. Modelings of the QF measurements described in (26) are appropriated for this analysis (subsequently referred to as new QF). However, most studies interpreting the DAMA/LIBRA’s results have used substantial larger QF values that were reported by the DAMA group in 1996 (39) (subsequently referred to as DAMA QF), which were obtained by measuring the response of NaI(Tl) crystals to nuclear recoils induced by neutrons from a 252Cf source. The best description of the measured nuclear recoil spectra from the 252Cf source obtained 30 ± 1% and 9 ± 1% for the sodium and iodine QF values, respectively, assuming no energy dependence of the QF values. Those values obtained from the new measurements are approximately 13 and 5% for the sodium and iodine, respectively, at 20 keVnr, where keVnr is nuclear recoil energy (26). Efficient noise rejection and correct evaluation of trigger and selection efficiencies are essential for proper estimation of the QFs (33, 40, 41). Although the measurements of the DAMA QF values were required to check the efficiency evaluations and no energy-dependent QF assumption (40), the hypothesis of different QFs (25) in the NaI(Tl) crystals used by DAMA/LIBRA and COSINE-100 needs to be checked. Note that results from analysis of the previous 59.5 days of COSINE-100 data with a 2-keVee threshold were not sufficient to exclude all the DAMA/LIBRA 3σ regions when different QFs are used (26).

To search for evidence of a WIMP signal in the data, we use a Bayesian approach with a likelihood function based on Poisson probability. The likelihood fit is performed to the measured single-hit energy spectra between 1 and 15 keVee for each WIMP model for several masses. Each crystal is fitted with a crystal-specific background model and a crystal-correlated WIMP signal for the combined fit by multiplying the five crystals’ likelihoods. Means and uncertainties for background components, which are determined from the modeling (31), are used to set Gaussian priors for the background. The systematic uncertainties are included in the fit as nuisance parameters with Gaussian prior (see Materials and Methods).

A good fit to the DAMA/LIBRA-phase2 data was obtained with the isospin-violating interaction (11, 26). We simultaneously use the DAMA/LIBRA-phase1 and phase2 data to fit three parameters: the WIMP mass, the WIMP-proton cross section, and fn/fp. The best fits were obtained for two different values of fn/fp, favoring WIMP-sodium and WIMP-iodine interactions as fn/fp = −0.76 and −0.71, respectively. For the best-fit values of fn/fp, the 3σ allowed regions in the WIMP-mass and the WIMP-proton cross-sectional parameter spaces are obtained (26).

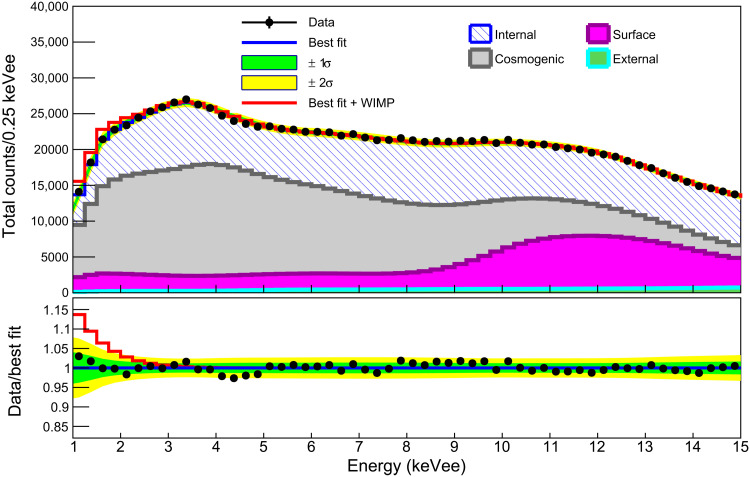

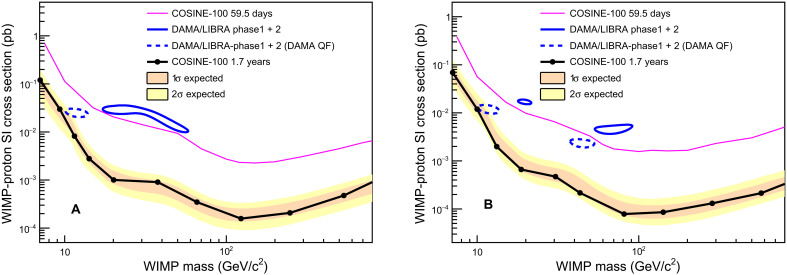

The COSINE-100 data are fitted to each of the different WIMP masses for each fn/fp value using only the new QF values. An example of a maximum likelihood fit for a 11.5 GeV/c2 WIMP and fn/fp = −0.76 WIMP signal is presented in Fig. 3. The summed event spectrum for the five crystals is shown together with the best-fit result. For comparison, the expected signal for a 11.5 GeV/c2 WIMP with a spin-independent WIMP-proton cross section of 2.5 × 10−2 picobarn (pb), the central value of the DAMA/LIBRA best fit using the DAMA QF values for the WIMP-sodium interaction, is shown by the red solid line. No excess of events that could be attributed to WIMP interactions is found for the considered WIMP signals. The posterior probabilities of signals are consistent with zero in all cases, and 90% confidence level limits are determined (see fig. S4). Figure 4 shows the 3σ contours of the DAMA/LIBRA data in the best-fit values of fn/fp using the new QF values and the DAMA QF values together with the 90% confidence level upper limits from the COSINE-100 data using the same fn/fp and the new QF values. The 90% confidence level limits from the 1.7-years COSINE-100 data show approximately one-order of magnitude better limits than those of our previous results using 59.5-days data and exclude the DAMA/LIBRA allowed 3σ regions for both of the two different QF values.

Fig. 3. Example fit results for a 11.5 GeV/c2 WIMP mass in the case of fn/fp=−0.76.

Presented here is the summed energy spectrum for the five crystals (black filled circles shown with 68% confidence level error bars) and the best fit (blue line) for which no WIMP signals are obtained. Fitted contributions to the background from internal radionuclide contaminations, the surface of the crystals and nearby materials, cosmogenic activation, and external backgrounds are indicated. The green (yellow) bands are the 68% (95%) confidence level intervals of the systematic uncertainty obtained from the likelihood fit. For presentation purposes, we indicate the signal shape (red line) assuming a WIMP-proton cross section of 2.5 × 10−2 pb corresponding to the DAMA best-fit value for the WIMP-sodium interaction using the DAMA QF values.

Fig. 4. Exclusion limits on the WIMP-proton spin-independent cross section for the isospin-violating interaction.

The 3σ allowed regions of the WIMP mass and the WIMP-proton cross section associated with the DAMA/LIBRA-phase1 + phase2 data (blue solid contours) using the new QF values in their best fit for (A) sodium scattering and (B) iodine scattering hypotheses are compared with the 90% confidence level exclusion limits from the COSINE-100 data (black solid line), together with the 68 and 95% probability bands for the expected 90% confidence level limit assuming the background-only hypothesis. The dashed blue contours show the allowed regions of the DAMA/LIBRA-phase1 + phase2 data using the DAMA QF values. For comparison, limits from the initial 59.5-day COSINE-100 data (21) are shown by the purple solid line. In each plot, we fix the effective coupling ratios to neutrons and protons fn/fp to the best-fit values of the DAMA data.

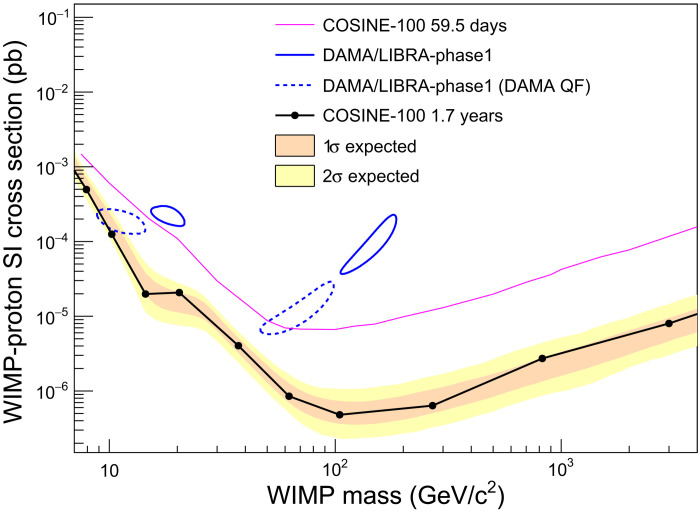

Although the DAMA/LIBRA-phase2 data do not fit with the canonical model, their phase1 data have been shown to be well fit with an isospin-conserving spin-independent WIMP-nucleon interaction (10, 26). The 90% confidence level upper limits from the COSINE-100 data for the canonical model are also obtained. Figure 5 shows the 3σ allowed regions that are associated with the DAMA/LIBRA-phase1 signal using the new QF values and the DAMA QF values, together with the 90% confidence level upper limits from the COSINE-100 data using the new QF values. These limits mostly exclude the DAMA/LIBRA allowed region although different QF values are considered for each experiment.

Fig. 5. Exclusion limits on the WIMP-nucleon spin-independent cross section of the isospin-conserving interaction.

The observed (filled circles with black solid line) 90% confidence level exclusion limits on the WIMP-nucleon spin-independent cross section from the COSINE-100 are shown together with the 68 and 95% probability bands for the expected 90% confidence level limit, assuming the background-only hypothesis. The limits are compared with a WIMP interpretation of the DAMA/LIBRA-phase1 3σ allowed region using the new QF (blue solid contours) and the DAMA QF (blue dashed contours) (10).

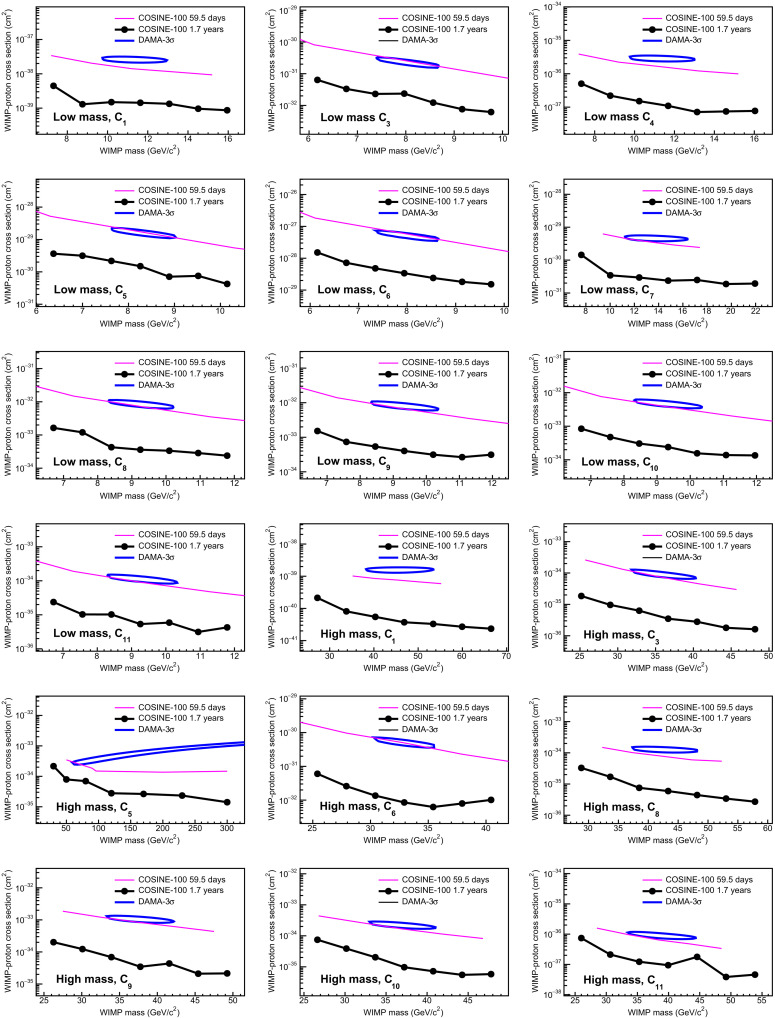

In addition, we have checked each operator in nonrelativistic effective field theory models where previous null results from the 59.5-day COSINE-100 data do not fully cover the 3σ regions of the DAMA/LIBRA data for a few operators (23). The 1.7-year data are now found to fully cover the 3σ allowed regions assuming same DAMA QF values as one can be seen in Fig. 6.

Fig. 6. Exclusion limits on the WIMP-proton cross section for the effective field theory operators.

DAMA/LIBRA 3σ allowed regions (blue contours) and COSINE-100 90% confidence level exclusion limits of previous analysis (pink solid lines) and this work (black dots and lines) on the WIMP-proton cross sections for the effective field theory operators using same DAMA QF values are presented. For each operator, fn/fp is fixed to the corresponding best-fit value of the DAMA/LIBRA data.

DISCUSSION

After the release of the initial 59.5-day COSINE-100 data with null observations using the same NaI(Tl) target material, a few possibilities were suggested that preserve the consistency between the DAMA/LIBRA and COSINE-100 results (23, 25, 26). The results of this analysis, with 1.7-year-accumulated COSINE-100 data and improved analysis technique with 1-keVee energy threshold, do not favor these suggested possibilities. A model-independent data analysis of the annual modulation with several-year COSINE-100 data is required for an unambiguous conclusion; nevertheless, these results provide strong constraints on the dark matter interpretation of the DAMA/LIBRA annual modulation signals with the same NaI(Tl) target materials.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Event selection

An event satisfying the trigger condition of coincident photoelectrons in both of the crystal’s readout PMTs within 200 ns is acquired with 500-MHz flash analog-to-digital converters and is recorded as an 8-μs-long waveform starting 2.4 μs before occurrence of the trigger (30). In the offline analysis, muon-induced events are rejected when the crystal hit event occurs within 30 ms after a muon candidate event in the muon detector (29, 42). In addition, we require that leading edges of the trigger pulses start later than 2.0 μs after the start of the recording, waveforms from the crystal contain more than two single photoelectrons, and the integral waveform area below the baseline does not exceed a limit. These criteria reject muon-induced phosphor events and electronic interference events. A multiple-hit event has accompanying crystal signals with more than four photoelectrons in an 8-μs time window or has a liquid scintillator signal above an 80-keVee threshold within 4 μs (28). A single-hit event is classified as one where the other detectors do not meet these criteria.

During the 1.7-year data-taking period, no significant environmental abnormality or unstable detector performance was observed. The high light yield of the six crystals, approximately 15 photoelectrons/keVee, allowed an analysis threshold of 2 keVee in the previous analysis. However, the other two crystals had lower light yields and required higher analysis thresholds of 4 and 8 keVee, respectively (17, 21). Because their direct impact on the WIMP search is not substantial, we do not include single-hit events from these two crystals in the WIMP search analysis, although they were used in the identification of multiple hits.

In the low-energy signal region below 10 keVee, PMT-induced noise events predominantly contribute to the single-hit physics data in two different ways. The first class has a fast decay time of less than 50 ns compared with a typical NaI(Tl) scintillation of about 250 ns. The second class, which occurs less often than the first, has different characteristics of slow rise and decay time, as characterized in (21, 23). Noise events of the second class are intermittently produced by certain PMTs. We have developed monitoring tools for data quality verification, including monitoring event rates of the second class of noise. If a crystal had an increased rate due to the second class of noise, then the relevant period of data was removed. One crystal detector had this class of noise for the whole period, but for the other five detectors, more than 95% of the recorded data could be used without the second-class noise-induced events.

A BDT was developed to separate scintillation signals from the first class of noise. The fast PMT-induced events with energies greater than 2 keVee were efficiently removed by the BDT, which is based on multiple parameters (21, 23): the balance of the deposited charge from two PMTs, the ratio of the leading-edge (0 to 50 ns) to trailing-edge (100 to 600 ns) charge, and the amplitude-weighted average time of the signal. However, using this BDT, the scintillation events with energies below 2 keVee were contaminated by an exponential increase in noise events.

We developed new parameters to characterize the PMT-induced noise events for efficient selection of the scintillation events below 2 keVee. Two likelihood parameters for an event are constructed by templates derived from data samples enriched alternatively in scintillation-signal events and noise-signal events. A 60Co source that produces low-energy electron signals through Compton scattering is used to generate the signal-enriched sample. Fast-decay events in the single-hit data sample are used as the noise-enriched sample.

The likelihood parameter of the event is calculated as

| (1) |

where Ti and Wi are the heights of the ith time bin in the reference template and event, respectively. Likelihood parameters for the scintillation signal events (lnℒs) and the PMT-induced noise events (lnℒn) are evaluated for each event. With these, we define a likelihood score as

| (2) |

where large pl for an event implies that the event is more closely matched to the scintillation signal than the PMT-induced noise events. The updated BDT is trained with the likelihood score. This provided good discrimination against PMT-induced noise events and enabled us to lower the threshold to 1 keVee (27). A BDT score, a single discriminating parameter created by combining the various selections for input parameters according to their corresponding importance, for the single-hit physics data near the energy threshold (1 to 1.25 keVee) is presented in fig. S1. With the established selection criteria, we reduced the PMT-induced noise contamination level to less than 0.5%.

Event selection efficiencies for the electron recoil events were evaluated with the 60Co calibration data. The efficiency is calculated by integrating the model distribution for the scintillation signals and the PMT-induced noise events shown in fig. S1. A specialized apparatus with a monoenergetic 2.42-MeV neutron beam was used to measure the selection efficiencies of the nuclear recoil events (33). This measurement was performed with a small-size test crystal that was cut from the same ingot as a crystal used for the COSINE-100 experiment. The efficiencies determined for the electron recoil events and the nuclear recoil events are consistent within the 5% level as shown in Fig. 1. Systematic uncertainties in the efficiency measurements account for deviations from different measurements and from the 60Co calibration data and the single-hit physics data.

Systematic uncertainties

In addition to the statistical uncertainties in the background and signal models, various sources of systematic uncertainties are taken into account. Errors in the selection efficiency, the energy resolution, the energy scale, and background modeling technique translate into uncertainties in the shapes of the signal and background probability density functions, as well as to rate changes. These quantities are allowed to vary within their uncertainties as nuisance parameters in the likelihood fit.

The most influential systematic uncertainty is the error associated with the efficiencies shown as the shaded region in Fig. 1. This is because the efficiency systematic uncertainty maximally covers the statistical uncertainties in the ROI. We include two types of systematic variations in the efficiency error. At first, we account maximum variations of the uncertainty across the width of the energy bin to provide ±1σ ranges as shown in fig. S2A. Relative uncertainties shown in fig. S2B are included as nuisance parameters of the background and signal in the likelihood function (see Eqs. 8 and 9). However, because of the dominant errors in the ROI, we consider maximum shape distortions that can mimic the WIMP signal as shown in fig. S2C. Its relative uncertainty is shown in fig. S2D and included as a nuisance parameter.

In the background model fit, background activities are constrained by Gaussian constraint terms added to the likelihood function as determined by measured activities and their uncertainties. The systematic uncertainties associated with the background modeling include the uncertainties of the activities estimated by the background model fit. In addition, different locations of external radioactive contaminations are taken into account by generating external contributions at different positions. Background contributions from 210Pb contamination on the surface of the NaI(Tl) crystals were studied with a small NaI(Tl) crystal exposed to 222Rn from a 226Ra source (37). Depth profiles from two exponential components were modeled to fit the 222Rn-contaminated crystal and matched to the test-setup data (31). Uncertainties in the measured depth profiles are propagated into systematic uncertainties. Here, we generate the background model associated with each systematic variation and account relative uncertainty to be added as the nuisance parameter.

The energy calibration is performed by tracking the positions of internal β and γ peaks from radioactive contaminations in the crystals, as well as with external sources (31). The nonlinear detector response of the NaI(Tl) crystals (36) in the low-energy region is modeled with an empirical function across all crystals (31). Subtle differences for each crystal from the general nonlinearity model of the NaI(Tl) crystals are evaluated to consider the systematic uncertainty on the energy scale. The energy resolution for each crystal is evaluated during the calibration process. In particular, tagged 0.8- (22Na) and 3.2-keVee (40K) x-ray lines in the multiple-hit data are used to determine the energy resolution for low-energy events. Statistical uncertainties associated with the number of tagged events are regarded as the resolution systematic. Figure 2 shows a comparison of the background model to the data together with ±1σ and ±2σ bands of the systematic uncertainties that are evaluated from the quadrature sum of each systematic component. The relative errors are used for the nuisance parameter of the background.

Expected WIMP signal

The differential nuclear recoil rate per unit target mass for elastic scattering between WIMPs of mass mχ and target nuclei of mass Μ is (10)

| (3) |

where ρχ is the local dark matter density, Enr is the nuclear recoil energy, σ(Μ, Enr) is the WIMP-nucleus cross section and f(v, t) is the time-dependent WIMP velocity distribution. The reduced mass μ is defined as mχΜ/(mχ + Μ) and the minimum WIMP velocity vmin is .

For the WIMP velocity distribution, we assume the SHM (43)

| (4) |

where Nesc is a normalization constant, vE is the Earth velocity relative to the WIMP dark matter, and σv is the velocity dispersion. The SHM parameterization is used with the local dark matter density ρχ = 0.3 GeV/cm3, vE = 232 km/s, , and the galactic escape velocity vesc = 544 km/s (44).

The effective field theory operators and nuclear form factors described in (45–48) are used to model the nuclear responses in the differential cross section. The generalized spin-independent response (47) is used for both the isospin-conserving and the isospin-violating spin-independent (SI) interactions. For isospin-violating SI interactions, the WIMP-nucleon coupling coefficient ratio, fn/fp, is fixed to the best-fit values for the DAMA/LIBRA data (26). These nuclear responses, including form factors, are implemented using the publicly available DMDD package (49) to evaluate the WIMP-nucleus cross section, σ(Μ, Enr) in Eq. 3 (raw signal spectra). We subsequently apply the QFs, energy resolution, and selection efficiency to obtain the expected nuclear recoil rate in electron-equivalent energy for the detector, dR/dEee. Figure S3 shows dR/dEnr (A) and dR/dEee (B) spectra for three different WIMP models assuming a WIMP-proton cross section equal to 1 pb.

In addition, the WIMP signals are generated in the context of the nonrelativistic effective theory of WIMP-nucleus scattering that has been tested using previous data without full coverage of the DAMA/LIBRA 3σ allowed regions (23). For simplicity, we assume that one of the effective operators allowed by Galilean invariance dominates in the effective Hamiltonian of a spin-half dark matter particle at a time. We use the best-fit neutron-over-proton coupling ratio of the DAMA/LIBRA-phase2 data assuming the DAMA QF reported in (12), for each operator. The DMDD package (49) is also used to generate signal spectra by the effective operators. A few operators are not evaluated because the DMDD package does not include form factors for these operators. Here, we assume the same DAMA QFs for the COSINE-100 data for a simple comparison.

Bayesian approach

A Bayesian approach is adopted to extract the WIMP signal from the COSINE-100 data. For each WIMP interaction model, a posterior probability density in terms of the WIMP-proton cross section σWIMP is obtained from the Bayes’ theorem using a marginalization of the likelihood function that includes the prior (38)

| (5) |

where P(σWIMP∣Μ) is a probability density function (PDF) and ℒ(Μ∣σWIMP, α, β) is the likelihood function. The prior π(σWIMP) has a constant and zero values for positive and negative σWIMP, respectively. The normalization constant N makes the integration of the posterior PDF to be unity and the Μ represents the measured data. The α and the β denote the nuisance parameters to control the effect by systematic uncertainties. Because the measurements are independent and follow Poisson probabilities, the likelihood function is built by a product of Poisson probabilities

| (6) |

where i and j denote the crystal number and the energy bin, respectively, and Mij is the number of observed events for crystal i in jth energy bin. The π(α, β) is a term for constraining nuisance parameters by systematic uncertainties.

The expected number of events, denoted as Eij(σ, α, β), is obtained as the sum of the number of events in the signal and background

| (7) |

where the number of background events Bij(α, β) and signal events Sij(σ, α) are generated from the simulated experiments through the background modeling and the WIMP signal discussed above, with effects by systematic uncertainties. The systematic uncertainty affecting the background model is included as a function of the nuisance parameter α and β, as

| (8) |

where is the number of background events obtained by modeling. The nuisance parameter αik controls the effect of the energy-dependent uncertainty, εijk, which is 1σ relative error for kth systematic uncertainty. Meanwhile, another nuisance parameter, βil, adjusts the activity for lth background component. Similar impact on the WIMP signal is considered by means of the expression

| (9) |

where Mi and Ti denote the mass and data exposure for crystal i and Rj is the expected rate of WIMP-proton interaction through an integration of dR/dEee in the jth energy bin. Each nuisance parameter is constrained with evaluated uncertainty assuming a Gaussian distribution

| (10) |

where δil is the uncertainty of activity for lth background component. The Markov Chain Monte Carlo (50, 51) via Metropolis-Hastings algorithm (52, 53) is used for the multivariable integration in posterior PDF. We developed our own Bayesian tool for this process. A comparison with a publicly available Bayesian analysis toolkit (54) was done for the initial 59.5-day COSINE-100 data, and both tools showed consistent results.

To avoid biasing the WIMP search, the fitter was tested with simulated event samples. Each piece of experimental data is prepared by Poisson random extraction from the modeled background spectrum (31), assuming a background-only hypothesis. Marginalization to obtain the posterior PDF for each simulation sample is performed to set the 90% confidence level exclusion limits as shown in fig. S4. The 1000 simulated experiments result in 68 and 95% bands of the expected limit presented in Figs. 4 and 5. The data fits are done in the same way as the simulated data. Figure S4 shows the posterior PDFs and their cumulative distribution functions (CDFs) of data for two different WIMP models. The CDF provides the 90% confidence level exclusion limit for each fit.

Acknowledgments

We thank the Korea Hydro and Nuclear Power (KHNP) Company for providing underground laboratory space at Yangyang.

Funding: This work is supported by the Institute for Basic Science (IBS) under project codes IBS-R016-A1 and NRF-2021R1A2C3010989, Republic of Korea; NSF grant nos. PHY-1913742 and DGE-1122492, WIPAC, the Wisconsin Alumni Research Foundation, USA; STFC grants ST/N000277/1 and ST/K001337/1, UK; grant no. 2017/02952-0 FAPESP, CAPES Finance Code 001, CNPq 131152/2020-3, Brazil.

Author contributions: The COSINE-100 detector was designed and constructed by the COSINE-100 collaboration. Operation, data processing, calibration, and detector simulation were performed by the COSINE-100 collaboration members. The main analysis was led by G.A. and Y.J.K, with strong guidance and review by the collaboration members. The paper was written by Y.J.K. and H.S.L. and edited by other members of the collaboration. All authors have participated in online shifts and approved the manuscript.

Competing interests: The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Data and materials availability: All data needed to evaluate the conclusion in the paper are present in the paper and/or the Supplementary Materials.

Supplementary Materials

This PDF file includes:

Figs. S1 to S4

REFERENCES AND NOTES

- 1.Clowe D., Bradač M., Gonzalez A. H., Markevitch M., Randall S. W., Jones C., Zaritsky D., A direct empirical proof of the existence of dark matter. Astrophys. J. 648, L109–L113 (2006). [Google Scholar]

- 2.Planck Collaboration, Ade P. A. R., Aghanim N., Arnaud M., Ashdown M., Aumont J., Baccigalupi C., Banday A. J., Barreiro R. B., Bartlett J. G., Bartolo N., Battaner E., Battye R., Benabed K., Benoit A., Benoit-Levy A., Bernard J.-P., Bersanelli M., Bielewicz P., Bock J. J., Bonaldi A., Bonavera L., Bond J. R., Borrill J., Bouchet F. R., Boulanger F., Bucher M., Burigana C., Butler R. C., Calabrese E., Cardoso J.-F., Catalano A., Challinor A., Chamballu A., Chary R.-R., Chiang H. C., Chluba J., Christensen P. R., Church S., Clements D. L., Colombi S., Colombo L. P. L., Combet C., Coulais A., Crill B. P., Curto A., Cuttaia F., Danese L., Davies R. D., Davis R. J., de Bernardis P., de Rosa A., de Zotti G., Delabrouille J., Desert F.-X., Di Valentino E., Dickinson C., Diego J. M., Dolag K., Dole H., Donzelli S., Dore O., Douspis M., Ducout A., Dunkley J., Dupac X., Efstathiou G., Elsner F., Ensslin T. A., Eriksen H. K., Farhang M., Fergusson J., Finelli F., Forni O., Frailis M., Fraisse A. A., Franceschi E., Frejsel A., Galeotta S., Galli S., Ganga K., Gauthier C., Gerbino M., Ghosh T., Giard M., Giraud-Heraud Y., Giusarma E., Gjerlow E., Gonzalez-Nuevo J., Gorski K. M., Gratton S., Gregorio A., Gruppuso A., Gudmundsson J. E., Hamann J., Hansen F. K., Hanson D., Harrison D. L., Helou G., Henrot-Versille S., Hernandez-Monteagudo C., Herranz D., Hildebrandt S. R., Hivon E., Hobson M., Holmes W. A., Hornstrup A., Hovest W., Huang Z., Huffenberger K. M., Hurier G., Jaffe A. H., Jaffe T. R., Jones W. C., Juvela M., Keihanen E., Keskitalo R., Kisner T. S., Kneissl R., Knoche J., Knox L., Kunz M., Kurki-Suonio H., Lagache G., Lahteenmaki A., Lamarre J.-M., Lasenby A., Lattanzi M., Lawrence C. R., Leahy J. P., Leonardi R., Lesgourgues J., Levrier F., Lewis A., Liguori M., Lilje P. B., Linden-Vornle M., Lopez-Caniego M., Lubin P. M., Macias-Perez J. F., Maggio G., Maino D., Mandolesi N., Mangilli A., Marchini A., Martin P. G., Martinelli M., Martinez-Gonzalez E., Masi S., Matarrese S., Mazzotta P., McGehee P., Meinhold P. R., Melchiorri A., Melin J.-B., Mendes L., Mennella A., Migliaccio M., Millea M., Mitra S., Miville-Deschenes M.-A., Moneti A., Montier L., Morgante G., Mortlock D., Moss A., Munshi D., Murphy J. A., Naselsky P., Nati F., Natoli P., Netterfield C. B., Norgaard-Nielsen H. U., Noviello F., Novikov D., Novikov I., Oxborrow C. A., Paci F., Pagano L., Pajot F., Paladini R., Paoletti D., Partridge B., Pasian F., Patanchon G., Pearson T. J., Perdereau O., Perotto L., Perrotta F., Pettorino V., Piacentini F., Piat M., Pierpaoli E., Pietrobon D., Plaszczynski S., Pointecouteau E., Polenta G., Popa L., Pratt G. W., Prezeau G., Prunet S., Puget J.-L., Rachen J. P., Reach W. T., Rebolo R., Reinecke M., Remazeilles M., Renault C., Renzi A., Ristorcelli I., Rocha G., Rosset C., Rossetti M., Roudier G., Rouille d’Orfeuil B., Rowan-Robinson M., Rubino-Martin J. A., Rusholme B., Said N., Salvatelli V., Salvati L., Sandri M., Santos D., Savelainen M., Savini G., Scott D., Seiffert M. D., Serra P., Shellard E. P. S., Spencer L. D., Spinelli M., Stolyarov V., Stompor R., Sudiwala R., Sunyaev R., Sutton D., Suur-Uski A.-S., Sygnet J.-F., Tauber J. A., Terenzi L., Toffolatti L., Tomasi M., Tristram M., Trombetti T., Tucci M., Tuovinen J., Turler M., Umana G., Valenziano L., Valiviita J., Van Tent B., Vielva P., Villa F., Wade L. A., Wandelt B. D., Wehus I. K., White M., White S. D. M., Wilkinson A., Yvon D., Zacchei A., Zonca A., Planck 2015 results. XIII. Cosmological parameters. Astron. Astrophys. 594, A13 (2016). [Google Scholar]

- 3.Baer H., Choi K.-Y., Kim J. E., Roszkowski L., Dark matter production in the early Universe: Beyond the thermal WIMP paradigm. Phys. Rep. 555, 1–60 (2015). [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lee B. W., Weinberg S., Cosmological lower bound on heavy-neutrino masses. Phys. Rev. Lett. 39, 165–168 (1977). [Google Scholar]

- 5.Goodman M. W., Witten E., Detectability of certain dark-matter candidates. Phys. Rev. D 31, 3059–3063 (1985). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.M. Battaglieri, A. Belloni, A. Chou, P. Cushman, B. Echenard, R. Essig, J. Estrada, J. L. Feng, B. Flaugher, P. J. Fox, P. Graham, C. Hall, R. Harnik, J. A. Hewett, J. Incandela, E. Izaguirre, D. M. Kinsey, M. Pyle, N. Roe, G. Rybka, P. Sikivie, T. M. P. Tait, N. Toro, R. Van De Water, N. Weiner, K. Zurek, E. Adelberger, A. Afanasev, D. Alexander, J. Alexander, V. C. Antochi, D. M. Asner, H. Baer, D. Banerjee, E. Baracchini, P. Barbeau, J. Barrow, N. Bastidon, J. Battat, S. Benson, A. Berlin, M. Bird, N. Blinov, K. K. Boddy, M. Bondi, W. M. Bonivento, M. Boulay, J. Boyce, M. Brodeur, L. Broussard, R. Budnik, P. Bunting, M. Caffee, S. S. Caiazza, S. Campbell, T. Cao, G. Carosi, M. Carpinelli, G. Cavoto, A. Celentano, J. H. Chang, S. Chattopadhyay, A. Chavarria, C.-Y. Chen, K. Clark, J. Clarke, O. Colegrove, J. Coleman, D. Cooke, R. Cooper, M. Crisler, P. Crivelli, F. D’Eramo, D. D’Urso, E. Dahl, W. Dawson, M. De Napoli, R. De Vita, P. De Niverville, S. Derenzo, A. D. Crescenzo, E. D. Marco, K. R. Dienes, M. Diwan, D. H. Dongwi, A. Drlica-Wagner, S. Ellis, A. C. Ezeribe, G. Farrar, F. Ferrer, E. Figueroa-Feliciano, A. Filippi, G. Fiorillo, B. Fornal, A. Freyberger, C. Frugiuele, C. Galbiati, I. Galon, S. Gardner, A. Geraci, G. Gerbier, M. Graham, E. Gschwendtner, C. Hearty, J. Heise, R. Henning, R. J. Hill, D. Hitlin, Y. Hochberg, J. Hogan, M. Holtrop, Z. Hong, T. Hossbach, T. B. Humensky, P. Ilten, K. Irwin, J. Jaros, R. Johnson, M. Jones, Y. Kahn, N. Kalantarians, M. Kaplinghat, R. Khatiwada, S. Knapen, M. Kohl, C. Kouvaris, J. Kozaczuk, G. Krnjaic, V. Kubarovsky, E. Kuflik, A. Kusenko, R. Lang, K. Leach, T. Lin, M. Lisanti, J. Liu, K. Liu, M. Liu, D. Loomba, J. Lykken, K. Mack, J. Mans, H. Maris, T. Markiewicz, L. Marsicano, C. J. Martoff, G. Mazzitelli, C. M. Cabe, Samuel D. Mc Dermott, A. M. Donald, B. M. Kinnon, D. Mei, T. Melia, G. A. Miller, K. Miuchi, Sahara Mohammed Prem Nazeer, O. Moreno, V. Morozov, F. Mouton, H. Mueller, A. Murphy, R. Neilson, T. Nelson, C. Neu, Y. Nosochkov, C. O’Hare, N. Oblath, J. Orrell, J. Ouellet, S. Pastore, S. Paul, M. Perelstein, A. Peter, N. Phan, N. Phinney, M. Pivovaroff, A. Pocar, M. Pospelov, J. Pradler, P. Privitera, S. Profumo, M. Raggi, S. Rajendran, N. Randazzo, T. Raubenheimer, C. Regenfus, A. Renshaw, A. Ritz, T. Rizzo, L. Rosenberg, A. Rubbia, B. Rybolt, T. Saab, B. R. Safdi, E. Santopinto, A. Scarff, M. Schneider, P. Schuster, G. Seidel, H. Sekiya, I. Seong, G. Simi, V. Sipala, T. Slatyer, O. Slone, P. F. Smith, J. Smolinsky, D. Snowden-Ifft, M. Solt, A. Sonnenschein, P. Sorensen, N. Spooner, B. Srivastava, I. Stancu, L. Strigari, J. Strube, A. O. Sushkov, M. Szydagis, P. Tanedo, D. Tanner, R. Tayloe, W. Terrano, J. Thaler, B. Thomas, B. Thorpe, T. Thorpe, J. Tiffenberg, N. Tran, M. Trovato, C. Tully, T. Tyson, T. Vachaspati, S. Vahsen, K. van Bibber, J. Vandenbroucke, A. Villano, T. Volansky, G. Wang, T. Ward, W. Wester, A. Whitbeck, D. A. Williams, M. Wing, L. Winslow, B. Wojtsekhowski, H.-B. Yu, S.-S. Yu, T.-T. Yu, X. Zhang, Y. Zhao, Y.-M. Zhong, US Cosmic Visions: New Ideas in Dark Matter 2017: Community Report, in U.S. Cosmic Visions: New Ideas in Dark Matter College Park, MD, USA, March 23–25, 2017. arXiv:1707.04591 [hep-ph] (14 July 2017).

- 7.Bernabei R., Belli P., Montecchia F., Di Nicolantonio W., Incicchitti A., Prosperi D., Bacci C., Dai C. J., Ding L. K., Kuang H. H., Ma J. M., Searching for wimps by the annual modulation signature. Phys. Let. B 424, 195–201 (1998). [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bernabei R., Belli P., Cappella F., Caracciolo V., Castellano S., Cerulli R., Dai C. J., d’Angelo A., d’Angelo S., Di Marco A., He H. L., Incicchitti A., Kuang H. H., Ma X. H., Montecchia F., Prosperi D., Sheng X. D., Wang R. G., Ye Z. P., Final model independent result of DAMA/LIBRA-phase1. Eur. Phys. J. C 73, 2648 (2013). [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bernabei R., Belli P., Bussolotti A., Cappella F., Caracciolo V., Cerulli R., Dai C.-J., d’Angelo A., Marco A. D., He H.-L., Incicchitti A., Ma X.-H., Mattei A., Merlo V., Montecchia F., Sheng X.-D., Ye Z.-P., First model independent results from DAMA/LIBRA-phase2. Nucl. Phys. At. Energy 19, 307–325 (2018). [Google Scholar]

- 10.Savage C., Gelmini G., Gondolo P., Freese K., Compatibility of DAMA/LIBRA dark matter detection with other searches. J. Cosmol. Astropart. Phys. 2009, 010 (2009). [Google Scholar]

- 11.Baum S., Freese K., Kelso C., Dark matter implications of DAMA/LIBRA-phase2 results. Phys. Lett. B 789, 262–269 (2019). [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kang S., Scopel S., Tomar G., Yoon J.-H., DAMA/LIBRA-phase2 in WIMP effective models. J. Cosmol. Astropart. Phys. 2018, 016 (2018). [Google Scholar]

- 13.Aprile E., Aalbers J., Agostini F., Alfonsi M., Amaro F. D., Anthony M., Arneodo F., Barrow P., Baudis L., Bauermeister B., Benabderrahmane M. L., Berger T., Breur P. A., Brown A., Brown E., Bruenner S., Bruno G., Budnik R., Bütikofer L., Calvén J., Cardoso J. M. R., Cervantes M., Cichon D., Coderre D., Colijn A. P., Conrad J., Cussonneau J. P., Decowski M. P., de Perio P., Di Gangi P., Di Giovanni A., Diglio S., Eurin G., Fei J., Ferella A. D., Fieguth A., Franco D., Fulgione W., Gallo Rosso A., Galloway M., Gao F., Garbini M., Geis C., Goetzke L. W., Greene Z., Grignon C., Hasterok C., Hogenbirk E., Itay R., Kaminsky B., Kessler G., Kish A., Landsman H., Lang R. F., Lellouch D., Levinson L., Lin Q., Lindemann S., Lindner M., Lopes J. A. M., Manfredini A., Maris I., Marrodán Undagoitia T., Masbou J., Massoli F. V., Masson D., Mayani D., Messina M., Micheneau K., Miguez B., Molinario A., Murra M., Naganoma J., Ni K., Oberlack U., Pakarha P., Pelssers B., Persiani R., Piastra F., Pienaar J., Pizzella V., Piro M.-C., Plante G., Priel N., Rauch L., Reichard S., Reuter C., Rizzo A., Rosendahl S., Rupp N., Dos Santos J. M. F., Sartorelli G., Scheibelhut M., Schindler S., Schreiner J., Schumann M., Scotto Lavina L., Selvi M., Shagin P., Silva M., Simgen H., Sivers M. V., Stein A., Thers D., Tiseni A., Trinchero G., Tunnell C., Wang H., Wei Y., Weinheimer C., Wulf J., Ye J., Zhang Y.; XENON Collaboration , Search for electronic recoil event rate modulation with 4 years of XENON100 data. Phys. Rev. Lett. 118, 101101 (2017). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Aprile E., Aalbers J., Agostini F., Alfonsi M., Althueser L., Amaro F. D., Anthony M., Arneodo F., Baudis L., Bauermeister B., Benabderrahmane M. L., Berger T., Breur P. A., Brown A., Brown A., Brown E., Bruenner S., Bruno G., Budnik R., Capelli C., Cardoso J. M. R., Cichon D., Coderre D., Colijn A. P., Conrad J., Cussonneau J. P., Decowski M. P., de Perio P., Di Gangi P., Di Giovanni A., Diglio S., Elykov A., Eurin G., Fei J., Ferella A. D., Fieguth A., Fulgione W., Gallo Rosso A., Galloway M., Gao F., Garbini M., Geis C., Grandi L., Greene Z., Qiu H., Hasterok C., Hogenbirk E., Howlett J., Itay R., Joerg F., Kaminsky B., Kazama S., Kish A., Koltman G., Landsman H., Lang R. F., Levinson L., Lin Q., Lindemann S., Lindner M., Lombardi F., Lopes J. A. M., Mahlstedt J., Manfredini A., Marrodán Undagoitia T., Masbou J., Masson D., Messina M., Micheneau K., Miller K., Molinario A., Morå K., Murra M., Naganoma J., Ni K., Oberlack U., Pelssers B., Piastra F., Pienaar J., Pizzella V., Plante G., Podviianiuk R., Priel N., Ramírez García D., Rauch L., Reichard S., Reuter C., Riedel B., Rizzo A., Rocchetti A., Rupp N., dos Santos J. M. F., Sartorelli G., Scheibelhut M., Schindler S., Schreiner J., Schulte D., Schumann M., Scotto Lavina L., Selvi M., Shagin P., Shockley E., Silva M., Simgen H., Thers D., Toschi F., Trinchero G., Tunnell C., Upole N., Vargas M., Wack O., Wang H., Wang Z., Wei Y., Weinheimer C., Wittweg C., Wulf J., Ye J., Zhang Y., Zhu T., Dark matter search results from a one ton-year exposure of XENON1T. Phys. Rev. Lett. 121, 111302 (2018). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Akerib D. S., Alsum S., Araújo H. M., Bai X., Balajthy J., Beltrame P., Bernard E. P., Bernstein A., Biesiadzinski T. P., Boulton E. M., Boxer B., Brás P., Burdin S., Byram D., Carmona-Benitez M. C., Chan C., Cutter J. E., Davison T. J. R., Druszkiewicz E., Fallon S. R., Fan A., Fiorucci S., Gaitskell R. J., Genovesi J., Ghag C., Gilchriese M. G. D., Gwilliam C., Hall C. R., Haselschwardt S. J., Hertel S. A., Hogan D. P., Horn M., Huang D. Q., Ignarra C. M., Jacobsen R. G., Ji W., Kamdin K., Kazkaz K., Khaitan D., Knoche R., Korolkova E. V., Kravitz S., Kudryavtsev V. A., Lenardo B. G., Lesko K. T., Liao J., Lin J., Lindote A., Lopes M. I., Manalaysay A., Mannino R. L., Marangou N., Marzioni M. F., McKinsey D. N., Mei D.-M., Moongweluwan M., Morad J. A., St.J. Murphy A., Nehrkorn C., Nelson H. N., Neves F., Oliver-Mallory K. C., Palladino K. J., Pease E. K., Rischbieter G. R. C., Rhyne C., Rossiter P., Shaw S., Shutt T. A., Silva C., Solmaz M., Solovov V. N., Sorensen P., Sumner T. J., Szydagis M., Taylor D. J., Taylor W. C., Tennyson B. P., Terman P. A., Tiedt D. R., To W. H., Tripathi M., Tvrznikova L., Utku U., Uvarov S., Velan V., Verbus J. R., Webb R. C., White J. T., Whitis T. J., Witherell M. S., Wolfs F. L. H., Woodward D., Xu J., Yazdani K., Zhang C., Search for annual and diurnal rate modulations in the LUX experiment. Phys. Rev. D 98, 062005 (2018). [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kim K. W., Kang W. G., Oh S. Y., Adhikari P., So J. H., Kim N. Y., Lee H. S., Choi S., Hahn I. S., Jeon E. J., Joo H. W., Kim B. H., Kim H. J., Kim Y. D., Kim Y. H., Lee J. K., Leonard D. S., Li J., Olsen S. L., Park H. S., Tests on NaI(Tl) crystals for WIMP search at the Yangyang Underground Laboratory. Astropart. Phys. 62, 249–257 (2015). [Google Scholar]

- 17.Adhikari G., Adhikari P., Barbosa de Souza E., Carlin N., Choi S., Choi W. Q., Djamal M., Ezeribe A. C., Ha C., Hahn I. S., Hubbard A. J. F., Jeon E. J., Jo J. H., Joo H. W., Kang W. G., Kang W., Kauer M., Kim B. H., Kim H., Kim H. J., Kim K. W., Kim M. C., Kim N. Y., Kim S. K., Kim Y. D., Kim Y. H., Kudryavtsev V. A., Lee H. S., Lee J., Lee J. Y., Lee M. H., Leonard D. S., Lim K. E., Lynch W. A., Maruyama R. H., Mouton F., Olsen S. L., Park H. K., Park H. S., Park J. S., Park K. S., Pettus W., Pierpoint Z. P., Prihtiadi H., Ra S., Rogers F. R., Rott C., Scarff A., Spooner N. J. C., Thompson W. G., Yang L., Yong S. H., Initial performance of the COSINE-100 experiment. Eur. Phys. J. C 78, 107 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Suerfu B., Wada M., Peloso W., Souza M., Calaprice F., Tower J., Ciampi G., Growth of ultra-high purity NaI(Tl) crystals for dark matter searches. Phys. Rev. Research 2, 013223 (2020). [Google Scholar]

- 19.Fushimi K., Kanemitsu Y., Hirata S., Chernyak D., Hazama R., Ikeda H., Imagawa K., Ishiura H., Ito H., Kisimoto T., Kozlov A., Takemoto Y., Yasuda K., Ejiri H., Hata K., Iida T., Inoue K., Koga M., Nakamura K., Orito R., Shima T., Umehara S., Yoshida S., Development of highly radiopure NaI(Tl) scintillator for PICOLON dark matter search project. Progress of Theoretical and Experimental Physic 2021, 043F01 (2021). [Google Scholar]

- 20.Amaré J., Cebrián S., Cintas D., Coarasa I., García E., Martínez M., Oliván M. A., Ortigoza Y., Ortiz de Solórzano A., Puimedón J., Salinas A., Sarsa M. L., Villar P., Annual modulation results from three-year exposure of ANAIS-112. Phys. Rev. D 103, 102005 (2021). [Google Scholar]

- 21.The COSINE-100 Collaboration , An experiment to search for dark-matter interactions using sodium iodide detectors. Nature 564, 83–86 (2018). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Adhikari G., Adhikari P., Barbosa de Souza E., Carlin N., Choi S., Djamal M., Ezeribe A. C., Ha C., Hahn I. S., Jeon E. J., Jo J. H., Joo H. W., Kang W. G., Kang W., Kauer M., Kim G. S., Kim H., Kim H. J., Kim K. W., Kim N. Y., Kim S. K., Kim Y. D., Kim Y. H., Ko Y. J., Kudryavtsev V. A., Lee H. S., Lee J., Lee J. Y., Lee M. H., Leonard D. S., Lynch W. A., Maruyama R. H., Mouton F., Olsen S. L., Park B. J., Park H. K., Park H. S., Park K. S., Pitta R. L. C., Prihtiadi H., Ra S. J., Rott C., Shin K. A., Scarff A., Spooner N. J. C., Thompson W. G., Yang L., Yu G. H., Search for a dark matter-induced annual modulation signal in NaI(Tl) with the COSINE-100 experiment. Phys. Rev. Lett. 123, 031302 (2019). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Adhikari G., Adhikari P., de Souza E. B., Carlin N., Choi S., Djamal M., Ezeribe A. C., Ha C., Hahn I. S., Jeon E. J., Jo J. H., Joo H. W., Kang W. G., Kang W., Kauer M., Kim G. S., Kim H., Kim H. J., Kim K. W., Kim N. Y., Kim S. K., Kim Y. D., Kim Y. H., Ko Y. J., Kudryavtsev V. A., Lee H. S., Lee J., Lee J. Y., Lee M. H., Leonard D. S., Lynch W. A., Maruyama R. H., Mouton F., Olsen S. L., Park B. J., Park H. K., Park H. S., Park K. S., Pitta R. L. C., Prihtiadi H., Ra S. J., Rott C., Shin K. A., Scarff A., Spooner N. J. C., Thompson W. G., Yang L., Yu G. H., Kang S., Scopel S., Tomar G., Yoon J.-H., COSINE-100 and DAMA/LIBRA-phase2 in WIMP effective models. J. Cosmol. Astropart. Phys. 2019, 048 (2019). [Google Scholar]

- 24.Zhitnitsky A., DAMA/LIBRA annual modulation and Axion Quark Nugget dark matter model. Phys. Rev. D 101, 083020 (2020). [Google Scholar]

- 25.Bernabei R., Belli P., Bussolotti A., Cappella F., Caracciolo V., Cerulli R., Dai C. J., d’Angelo A., di Marco A., Ferrari N., Incicchitti A., Ma X. H., Mattei A., Merlo V., Montecchia F., Sheng X. D., Ye Z. P., The DAMA project: Achievements, implications and perspectives. Prog. Part. Nucl. Phys. 114, 103810 (2020). [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ko Y. J., Kim K. W., Adhikari G., Adhikari P., Barbosa de Souza E., Carlin N., Choi J. J., Choi S., Djamal M., Ezeribe A. C., Ha C., Hahn I. S., Jeon E. J., Jo J. H., Kang W. G., Kauer M., Kim G. S., Kim H., Kim H. J., Kim N. Y., Kim S. K., Kim Y. D., Kim Y. H., Lee E. K., Lee H. S., Lee J., Lee J. Y., Lee M. H., Lee S. H., Leonard D. S., Lynch W. A., Manzato B. B., Maruyama R. H., Neal R. J., Olsen S. L., Park B. J., Park H. K., Park H. S., Park K. S., Pitta R. L. C., Prihtiadi H., Ra S. J., Rott C., Shin K. A., Scarff A., Spooner N. J. C., Thompson W. G., Yang L., Yu G. H., Comparison between DAMA/LIBRA and COSINE-100 in the light of quenching factors. J. Cosmol. Astropart. Phys. 2019, 008 (2019). [Google Scholar]

- 27.The COSINE-100 Collaboration , Lowering the energy threshold in COSINE-100 dark matter searches. Astropart. Phys. 130, 102581 (2021). [Google Scholar]

- 28.Adhikari G., Barbosa de Souza E., Carlin N., Choi J. J., Choi S., Djamal M., Ezeribe A. C., França L. E., Ha C., Hahn I. S., Jeon E. J., Jo J. H., Kang W. G., Kauer M., Kim H., Kim H. J., Kim K. W., Kim S. K., Kim Y. D., Kim Y. H., Ko Y. J., Lee E. K., Lee H. S., Lee J., Lee J. Y., Lee M. H., Lee S. H., Leonard D. S., Manzato B. B., Maruyama R. H., Neal R. J., Olsen S. L., Park B. J., Park H. K., Park H. S., Park K. S., Pitta R. L. C., Prihtiadi H., Ra S. J., Rott C., Shin K. A., Scarff A., Spooner N. J. C., Thompson W. G., Yang L., Yu G. H., The COSINE-100 liquid scintillator veto system. Nucl. Instrum. Meth. A 1006, 165431 (2021). [Google Scholar]

- 29.Prihtiadi H., Adhikari G., Adhikari P., Barbosa de Souza E., Carlin N., Choi S., Choi W. Q., Djamal M., Ezeribe A. C., Ha C., Hahn I. S., Hubbard A. J. F., Jeon E. J., Jo J. H., Joo H. W., Kang W., Kang W. G., Kauer M., Kim B. H., Kim H., Kim H. J., Kim K. W., Kim N. Y., Kim S. K., Kim Y. D., Kim Y. H., Kudryavtsev V. A., Lee H. S., Lee J., Lee J. Y., Lee M. H., Leonard D. S., Lim K. E., Lynch W. A., Maruyama R. H., Mouton F., Olsen S. L., Park H. K., Park H. S., Park J. S., Park K. S., Pettus W., Pierpoint Z. P., Ra S., Rogers F. R., Rott C., Scarff A., Spooner N. J. C., Thompson W. G., Yang L., Yong S. H., Muon detector for the COSINE-100 experiment. J. Instrum. 13, T02007 (2018). [Google Scholar]

- 30.Adhikari G., Adhikari P., Barbosa de Souza E., Carlin N., Choi S., Choi W., Djamal M., Ezeribe A. C., Ha C., Hahn I. S., Hubbard A. J. F., Jeon E. J., Jo J. H., Joo H. W., Kang W. G., Kang W. S., Kauer M., Kim H., Kim H. J., Kim K. W., Kim M. C., Kim N. Y., Kim S. K., Kim Y. D., Kim Y. H., Kudryavtsev V. A., Lee H. S., Lee J., Lee M. H., Lim K. E., Leonard D. S., Maruyama R. H., Mouton F., Na S., Olsen S. L., Park H. K., Park H. S., Park J. S., Park K. S., Pettus W., Prihtiadi H., Rott C., Scarff A., Spooner N. J. C., Thompson W. G., Yan L., The COSINE-100 data acquisition system. J. Instrum. 13, P09006 (2018). [Google Scholar]

- 31.Adhikari G., Barbosa de Souza E., Carlin N., Choi J. J., Choi S., Djamal M., Ezeribe A. C., França L. E., Ha C., Hahn I. S., Jeon E. J., Jo J. H., Joo H. W., Kang W. G., Kauer M., Kim H., Kim H. J., Kim K. W., Kim S. H., Kim S. K., Kim W. K., Kim Y. D., Kim Y. H., Ko Y. J., Lee E. K., Lee H., Lee H. S., Lee H. Y., Lee I. S., Lee J., Lee J. Y., Lee M. H., Lee S. H., Lee S. M., Leonard D. S., Lynch W. A., Manzato B. B., Maruyama R. H., Neal R. J., Olsen S. L., Park B. J., Park H. K., Park H. S., Park K. S., Pitta R. L. C., Prihtiadi H., Ra S. J., Rott C., Shin K. A., Scarff A., Spooner N. J. C., Thompson W. G., Yang L., Yu G. H.; COSINE-100 Collaboration , Background modeling for dark matter search with 1.7 years of COSINE-100 data. Eur. Phys. J. C 81, 837 (2021). [Google Scholar]

- 32.Friedman J. H., Greedy function approximation: A gradient boosting machine. Ann. Stat. 29, 1189–1232 (2001). [Google Scholar]

- 33.Joo H. W., Park H. S., Kim J. H., Lee J. Y., Kim S. K., Kim Y. D., Lee H. S., Kim S. H., Quenching factor measurement for NaI(Tl) scintillation crystal. Astropart. Phys. 108, 50–56 (2019). [Google Scholar]

- 34.Agostinelli S., Allison J., Amako K., Apostolakis J., Araujo H., Arce P., Asai M., Axen D., Banerjee S., Barrand G., Behner F., Bellagamba L., Boudreau J., Broglia L., Brunengo A., Burkhardt H., Chauvie S., Chuma J., Chytracek R., Cooperman G., Cosmo G., Degtyarenko P., Dell’Acqua A., Depaola G., Dietrich D., Enami R., Feliciello A., Ferguson C., Fesefeldt H., Folger G., Foppiano F., Forti A., Garelli S., Giani S., Giannitrapani R., Gibin D., Gómez Cadenas J. J., González I., Gracia Abril G., Greeniaus G., Greiner W., Grichine V., Grossheim A., Guatelli S., Gumplinger P., Hamatsu R., Hashimoto K., Hasui H., Heikkinen A., Howard A., Ivanchenko V., Johnson A., Jones F. W., Kallenbach J., Kanaya N., Kawabata M., Kawabata Y., Kawaguti M., Kelner S., Kent P., Kimura A., Kodama T., Kokoulin R., Kossov M., Kurashige H., Lamanna E., Lampén T., Lara V., Lefebure V., Lei F., Liendl M., Lockman W., Longo F., Magni S., Maire M., Medernach E., Minamimoto K., Mora de Freitas P., Morita Y., Murakami K., Nagamatu M., Nartallo R., Nieminen P., Nishimura T., Ohtsubo K., Okamura M., O’Neale S., Oohata Y., Paech K., Perl J., Pfeiffer A., Pia M. G., Ranjard F., Rybin A., Sadilov S., Di Salvo E., Santin G., Sasaki T., Savvas N., Sawada Y., Scherer S., Sei S., Sirotenko V., Smith D., Starkov N., Stoecker H., Sulkimo J., Takahata M., Tanaka S., Tcherniaev E., Safai Tehrani E., Tropeano M., Truscott P., Uno H., Urban L., Urban P., Verderi M., Walkden A., Wander W., Weber H., Wellisch J. P., Wenaus T., Williams D. C., Wright D., Yamada T., Yoshida H., Zschiesche D., GEANT4—A simulation toolkit. Nucl. Instrum. Meth. A 506, 250–303 (2003). [Google Scholar]

- 35.Barbosa de Souza E., Park B. J., Adhikari G., Adhikari P., Carlin N., Choi J. J., Choi S., Djamal M., Ezeribe A. C., Ha C., Hahn I. S., Jeon E. J., Jo J. H., Kang W. G., Kauer M., Kim G. S., Kim H., Kim H. J., Kim K. W., Kim N. Y., Kim S. K., Kim Y. D., Kim Y. H., Ko Y. J., Kudryavtsev V. A., Lee E. K., Lee H. S., Lee J., Lee J. Y., Lee M. H., Lee S. H., Leonard D. S., Lynch W. A., Manzato B. B., Maruyama R. H., Neal R. J., Olsen S. L., Park H. K., Park H. S., Park K. S., Pitta R. L. C., Prihtiadi H., Ra S. J., Rott C., Shin K. A., Scarff A., Spooner N. J. C., Thompson W. G., Yang L., Yu G. H.; COSINE-100 Collaboration , Study of cosmogenic radionuclides in the COSINE-100 NaI(Tl) detectors. Astropart. Phys. 115, 102390 (2020). [Google Scholar]

- 36.Swiderski L., Moszynski M., Czarnacki W., Szawlowski M., Szczesniak T., Pausch G., Plettner C., Roemer K., Schotanus P., Response of doped alkali iodides measured with gamma-ray absorption and Compton electrons. Nucl. Instrum. Meth. A 705, 42–46 (2013). [Google Scholar]

- 37.Yu G. H., Ha C., Jeon E. J., Kim K. W., Kim N. Y., Kim Y. D., Lee H. S., Park H. K., Rott C., Depth profile study of 210Pb in the surface of an NaI(Tl) crystal. Astropart. Phys. 126, 102518 (2021). [Google Scholar]

- 38.Particle Data Group Collaboration , Review of particle physics. Phys. Rev. D 98, 030001 (2018). [Google Scholar]

- 39.Bernabei R., Belli P., Landoni V., Montecchia F., Di W., Nicolantonio, Incicchitti A., Prosperi D., Bacci C., Dai C. J., Ding L. K., Kuang H. H., Ma J. M., Angelone M., Bastistoni P., Pillon M., New limits on WIMP search with large-mass low-radioactivity NaI(Tl) set-up at Gran Sasso. Phys. Lett. B 389, 757–766 (1996). [Google Scholar]

- 40.Collar J. I., Quenching and channeling of nuclear recoils in NaI(Tl): Implications for dark-matter searches. Phys. Rev. C 88, 035806 (2013). [Google Scholar]

- 41.Xu J., Shields E., Calaprice F., Westerdale S., Froborg F., Suerfu B., Alexander T., Aprahamian A., Back H. O., Casarella C., Fang X., Gupta Y. K., Ianni A., Lamere E., Lippincott W. H., Liu Q., Lyons S., Siegl K., Smith M., Tan W., Kolk B. V., Scintillation efficiency measurement of Na recoils in NaI(Tl) below the DAMA/LIBRA energy threshold. Phys. Rev. C 92, 015807 (2015). [Google Scholar]

- 42.Prihtiadi H., Adhikari G., Barbosa de Souza E., Carlin N., Choi J. J., Choi S., Djamal M., Ezeribe A. C., França L. E., Ha C., Hahn I. S., Jeon E. J., Jo J. H., Kang W. G., Kauer M., Kim H., Kim H. J., Kim K. W., Kim S. K., Kim Y. D., Kim Y. H., Ko Y. J., Lee E. K., Lee H. S., Lee J., Lee J. Y., Lee M. H., Lee S. H., Leonard D. S., Manzato B. B., Maruyama R. H., Neal R. J., Olsen S. L., Park B. J., Park H. K., Park H. S., Park K. S., Pitta R. L. C., Ra S. J., Rott C., Shin K. A., Scraff A., Spooner N. J. C., Thompson W. G., Yang L., Yu G. H., Measurement of the cosmic muon annual and diurnal flux variation with the COSINE-100 detector. J. Cosmol. Astropart. Phys. 2021, 013 (2021). [Google Scholar]

- 43.Freese K., Frieman J. A., Gould A., Signal modulation in cold-dark-matter detection. Phys. Rev. D 37, 3388–3405 (1988). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Smith M. C., Ruchti G. R., Helmi A., Wyse R. F. G., Fulbright J. P., Freeman K. C., Navarro J. F., Seabroke G. M., Steinmetz M., Williams M., Bienayme O., Binney J., Bland-Hawthorn J., Dehnen W., Gibson B. K., Gilmore G., Grebel E. K., Munari U., Parker Q. A., Scholz R. D., Siebert A., Watson F. G., Zwitter T., The RAVE survey: Constraining the local Galactic escape speed. Mon. Notices Royal Astron. Soc. 379, 755–772 (2007). [Google Scholar]

- 45.Gluscevic V., Gresham M. I., McDermott S. D., Peter A. H. G., Zurek K. M., Identifying the theory of dark matter with direct detection. J. Cosmol. Astropart. Phys. 2015, 057 (2015). [Google Scholar]

- 46.Anand N., Fitzpatrick A. L., Haxton W. C., Weakly interacting massive particle-nucleus elastic scattering response. Phys. Rev. C 89, 065501 (2014). [Google Scholar]

- 47.Fitzpatrick A. L., Haxton W., Katz E., Lubbers N., Xu Y., The effective field theory of dark matter direct detection. J. Cosmol. Astropart. Phys. 1302, 004 (2013). [Google Scholar]

- 48.Gresham M. I., Zurek K. M., Effect of nuclear response functions in dark matter direct detection. Phys. Rev. D 89, 123521 (2014). [Google Scholar]

- 49.V. Gluscevic, S. D. McDermott, dmdd: Dark matter direct detection, Astrophysics Source Code Library [ascl:1506.002] (2015).

- 50.W. Gilks, S. Richardson, D. Spiegelhalter, Markov Chain Monte Carlo in Practice (Chapman & Hall/CRC, 2006). [Google Scholar]

- 51.D. Gamerman, H. F. Lopes, Markov Chain Monte Carlo (Chapman & Hall/CRC, 2006). [Google Scholar]

- 52.Metropolis N., Rosenbluth A. W., Rosenbluth M. N., Teller A. H., Equation of state calculations by fast computing machines. J. Chem. Phys. 21, 1087–1092 (1953). [Google Scholar]

- 53.Hastings W. K., Monte Carlo sampling methods using Markov chains and their applications. Biometrika 57, 97–109 (1970). [Google Scholar]

- 54.Caldwell A., Kollar D., Kroninger K., BAT: The Bayesian analysis toolkit. Comput. Phys. Commun. 180, 2197–2209 (2009). [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Figs. S1 to S4