Abstract

Objective

US-based descriptions of severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) infection have focused on patients with severe disease. Our objective was to describe characteristics of a predominantly outpatient population tested for SARS-CoV-2 in an area receiving comprehensive testing.

Methods

We extracted data on demographic characteristics and clinical data for all patients (91% outpatient) tested for SARS-CoV-2 at University of Utah Health clinics in Salt Lake County, Utah, from March 10 through April 24, 2020. We manually extracted data on symptoms and exposures from a subset of patients, and we calculated the adjusted odds of receiving a positive test result by demographic characteristics and clinical risk factors.

Results

Of 17 662 people tested, 1006 (5.7%) received a positive test result for SARS-CoV-2. Hispanic/Latinx people were twice as likely as non-Hispanic White people to receive a positive test result (adjusted odds ratio [aOR] = 2.0; 95% CI, 1.3-3.1), although the severity at presentation did not explain this discrepancy. Young people aged 0-19 years had the lowest rates of receiving a positive test result for SARS-CoV-2 (<4 cases per 10 000 population), and adults aged 70-79 and 40-49 had the highest rates of hospitalization per 100 000 population among people who received a positive test result (16 and 11, respectively).

Conclusions

We found disparities by race/ethnicity and age in access to testing and in receiving a positive test result among outpatients tested for SARS-CoV-2. Further research and public health outreach on addressing racial/ethnic and age disparities will be needed to effectively combat the coronavirus disease 2019 pandemic in the United States.

Keywords: SARS-CoV-2, COVID-19, health disparities, outpatient, comprehensive testing

Since its emergence in late 2019, coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19), which is caused by infection with severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2), has resulted in more than 18 million cases and 690 000 deaths. 1 As of August 4, 2020, the United States has been the epicenter of the COVID-19 pandemic, with 26% of global cases. 2 Although most case- and disease-course descriptions have originated outside the United States, 3 -5 emerging data suggest that patterns of COVID-19 may differ in the United States compared with other highly affected countries, such as China and Italy. Most US-based clinical or epidemiological descriptions of COVID-19 have been among hospitalized and intensive care unit (ICU) patients because of limited testing capacity in much of the United States. 6 -11 This bias in study population potentially masks differences between people who are hospitalized and people who are not hospitalized with SARS-CoV-2 infection. Furthermore, because of the locations of outbreaks, most US-based studies have focused on highly urban, densely populated areas. 10 -13

Widespread lack of SARS-CoV-2 testing capacity in the United States has led to delays in case detection and isolation, substantial underreporting of cases (particularly among people with mild and moderate symptoms), and gross underestimates of the true number of fatalities. 13 -18 In contrast, Utah has maintained high per-capita testing rates (administering 188 tests per 100 000 people per day) and a stable proportion of positive tests throughout the study period (approximately 5.5% of all tests were positive from March 12 through April 24, 2020). 19 As such, testing in Utah has not been restricted to the most critical patients, and most SARS-CoV-2 tests are administered in outpatient settings to community-dwelling people.

The objective of this study was to compare demographic characteristics of patients who received positive and negative test results for SARS-CoV-2 in a population with higher testing rates than among previously published cohorts. 6 -11 We present the clinical, epidemiological, and demographic characteristics of the cohort of all people (hospitalized and community-dwelling) tested for SARS-CoV-2 infection at University of Utah Health (UHealth) from March 10 through April 24, 2020. UHealth primarily serves Salt Lake County, Utah, a diverse, medium-density, medium-sized metropolitan area of slightly more than 1 million people. Because of the expanded testing capacity for SARS-CoV-2 in Utah, these data provide an alternate picture of the full spectrum of SARS-CoV-2 epidemiology relative to studies of hospitalized patients.

Methods

All patients tested for SARS-CoV-2 in the UHealth system during the study period were eligible for this cohort study. We developed an electronic, near–real-time registry by extracting electronic medical records from all patients tested for SARS-CoV-2 at UHealth from March 10 through April 24, 2020, for a total sample size of 20 088, constituting approximately 20% of all tests conducted in Utah during that time. During this time frame, test eligibility required at least 1 of the following symptoms: cough, fever, shortness of breath, or a high risk of exposure given recent travel or contact with a person who tested positive for SARS-CoV-2. We built the registry from the hospital operations dashboards, which contain data on demographic characteristics and test results for all patients tested for SARS-CoV-2. We linked these data with additional data using the Enterprise Data Warehouse at UHealth. The Enterprise Data Warehouse aggregates data from the health system’s disparate data collection systems in support of operations and research. We extracted data on demographic characteristics, International Classification of Diseases (ICD) billing codes, and vital signs from the Enterprise Data Warehouse to create the data set for this study. In addition to collecting UHealth data, we extracted county-level 20 and state-level 19 data from public dashboards for comparison.

For a subset of patients tested during March 10-31, 2020, we manually extracted symptom data from the clinical text of patients’ medical records from 24 hours before and 24 hours after SARS-CoV-2 testing. A total of 7113 of the 20 088 tests were performed from March 10 through March 31, 2020. We selected medical records to include at least 20% of patients tested on each day, for a total of 1821 patients. We chose symptoms based on previous literature. 21,22

UHealth clinicians and staff members collected demographic and clinical characteristics from all patients at intake for primary care or hospital visits and via questionnaire for mobile testing facilities. Variables included age, sex, race/ethnicity, comorbidities (via billing codes), pulse rate, respiratory rate, SpO2, body temperature, and the department that ordered SARS-CoV-2 testing. Ordering departments were acute care, emergency department (ED), ICU, mobile testing facility, outpatient clinic, telemedicine, external department, inpatient rehabilitation, and labor and delivery/maternal–newborn. Because of small sample sizes, we combined external, inpatient rehabilitation, and labor and delivery/maternal–newborn categories into a single “other” category. We created a single variable for race/ethnicity as non-Hispanic White, Hispanic/Latino, Asian, Black or African American, Native Hawaiian or other Pacific Islander, American Indian/Alaska Native, “other” race, unknown race, or chose not to disclose. For this single race/ethnicity variable, we defined Hispanic/Latino as people reporting their ethnicity as Hispanic/Latino and their race as White, other, or unknown. We analyzed people of Hispanic/Latino ethnicity as a distinct category because they are the largest racial/ethnic minority group in Salt Lake County and compose 19% of the population. 23 Although we were unable to determine if people were hospitalized because of their SARS-CoV-2 infection, we approximated SARS-CoV-2–related hospitalization by recording all-cause hospitalization within 14 days of SARS-CoV-2 testing. Epidemiologic risk factors collected from the subset of manually reviewed medical records included history of travel, exposure to a SARS-CoV-2–positive person, health care worker status, and smoking status. We collected data on the following symptoms: cough, fever, shortness of breath, myalgia, headache, lethargy, nasal congestion, sore throat, diarrhea, and nausea/vomiting; we also noted duration of symptoms at presentation. In analysis, we assumed symptoms/risk factors not mentioned in patient medical records were absent.

For each demographic variable—age, sex, and race/ethnicity—we used logistic regression to calculate the odds of receiving a positive test result for SARS-CoV-2 in the full data set. We calculated both unadjusted odds ratios (ORs) and adjusted ORs (aORs) (adjusted by cough, fever, shortness of breath, and contact with a person who tested positive for SARS-CoV-2) to control for confounding. To compare our data with the underlying racial/ethnic and age distribution of Salt Lake County, we extracted county data on population race/ethnicity and age from the US Census Bureau. 23,24 We also compared the number of tests administered by UHealth with the number of tests conducted statewide during the same period. 19 The University of Utah Institutional Review Board reviewed this study and determined it to be exempt.

Of 20 088 people tested for SARS-CoV-2 from March 10 through April 24, 2020, we excluded people who were missing data on age, sex, or race/ethnicity and people who chose not to disclose their race (n = 2426, 12.1%), leaving 17 662 people in the study cohort. This number constituted 20% of all SARS-CoV-2 tests conducted in Utah during the study period. 19

Results

Characteristics of Total Cohort

Of 17 662 people in the study cohort, 1006 (5.7%) received a positive test result for SARS-CoV-2. Testing occurred at multiple types of facilities: 16 143 (91.4%) tested in outpatient clinics, 951 (5.4%) in the ED, 206 (1.2%) in acute care facilities, 169 (1.0%) at mobile testing facilities, and 98 (0.6%) at the ICU (Table 1). The facility type that ordered SARS-CoV-2 tests was not indicative of the test result. For example, approximately 90% and 5% of tests were ordered from outpatient clinics and the ED, respectively, both for patients who received a positive test result and for patients who received a negative test result for SARS-CoV-2.

Table 1.

Characteristics of people tested for SARS-CoV-2 and odds of testing positive for SARS-CoV-2, among people tested in the UHealth system from March 10 through April 24, 2020, in Salt Lake City, Utah (n = 17 662)a

| Characteristics | SARS-CoV-2 positive (n = 1006) a |

SARS-CoV-2 negative (n = 16 656) a |

Unadjusted OR (95% CI) | Adjusted

b

OR (95% CI) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age, median (IQR), y | 38.2 (27.4-51.0) | 39.6 (28.2-54.2) | — | — |

| Age group, y | ||||

| 0-9 | 19 (1.9) | 551 (3.3) | 0.5 (0.3-0.8) | 0.5 (0.1-2.4) |

| 10-19 | 60 (6.0) | 908 (5.5) | 1.0 (0.7-1.3) | 0.8 (0.3-2.1) |

| 20-29 | 229 (22.8) | 3335 (20.0) | 1.0 [Reference] | 1.0 [Reference] |

| 30-39 | 236 (23.5) | 3630 (21.8) | 0.9 (0.8-1.1) | 0.8 (0.4-1.3) |

| 40-49 | 192 (19.1) | 3030 (18.2) | 0.9 (0.8-1.1) | 0.6 (0.4-1.1) |

| 50-59 | 153 (15.2) | 2314 (13.9) | 1.0 (0.8-1.2) | 1.0 (0.6-1.7) |

| 60-69 | 76 (7.6) | 1756 (10.5) | 0.6 (0.5-0.8) | 0.4 (0.1-0.9) |

| 70-79 | 31 (3.1) | 891 (5.3) | 0.5 (0.3-0.7) | 1.6 (0.8-3.3) |

| ≥80 | 10 (1.0) | 241 (1.4) | 0.6 (0.3-1.2) | 0.8 (0.2-3.3) |

| Sex | ||||

| Female | 461 (45.8) | 9445 (56.7) | 1.0 [Reference] | 1.0 [Reference] |

| Male | 545 (54.2) | 7211 (43.3) | 1.5 (1.4-1.8) | 1.3 (0.9-1.9) |

| Race/ethnicity | ||||

| Non-Hispanic White | 486 (48.3) | 12 657 (76.0) | 1.0 [Reference] | 1.0 [Reference] |

| Hispanic/Latino | 400 (39.8) | 2399 (14.4) | 4.3 (3.8-5.0) | 2.0 (1.3-3.1) |

| Combined c | 120 (11.9) | 1600 (9.6) | 2.0 (1.6-2.4) | 0.6 (0.3-1.4) |

| Black/African American | 30 (3.0) | 328 (2.0) | NC | NC |

| Asian | 30 (30.0) | 415 (2.5) | ||

| American Indian/Alaska Native | 6 (0.6) | 146 (0.9) | ||

| Native Hawaiian/other Pacific Islander | 10 (1.0) | 213 (1.3) | ||

| Other | 44 (4.4) | 498 (3.0) | ||

| Comorbidities | ||||

| Any | 131 (13.0) | 3358 (20.2) | NC | NC |

| Fluid/electrolyte disorders | 7 (0.7) | 218 (1.3) | ||

| Renal failure | 8 (0.8) | 169 (1.0) | ||

| Alcohol abuse | 5 (0.5) | 206 (1.2) | ||

| Chronic blood loss anemia | 5 (0.5) | 160 (1.0) | ||

| Chronic pulmonary disease | 10 (1.0) | 215 (1.3) | ||

| Depression | 5 (0.5) | 61 (0.4) | ||

| Hypertensive renal disease without renal failure | 14 (1.4) | 395 (2.4) | ||

| Hypertension, uncomplicated | 108 (10.7) | 2779 (16.7) | ||

| Obesity | 11 (1.1) | 339 (2.0) | ||

| Other | 12 (1.2) | 595 (3.6) | ||

| Pulse rate (beats per minute) | ||||

| Median (IQR) | 87 (78-99) | 85 (75-96) | NC | NC |

| Missing data | 117 (11.6) | 1919 (11.5) | ||

| Respiratory rate (breaths per minute) | ||||

| Median (IQR) | 18 (16-20) | 18 (16-20) | NC | NC |

| Missing data | 892 (88.7) | 14 428 (86.6) | ||

| SpO2 (%) | ||||

| Median (IQR) | 96 (94-97) | 96 (95-98) | NC | NC |

| Missing data | 111 (11.0) | 1900 (11.4) | ||

| Body temperature | ||||

| Median (IQR), °C | 37.1 (36.7-37.6) | 37 (36.6-37.3) | NC | NC |

| Missing data | 594 (59.0) | 9524 (57.2) | ||

| Facility that ordered SARS-CoV-2 test | ||||

| Acute care | 6 (0.6) | 200 (1.2) | NC | NC |

| Emergency department | 54 (5.4) | 879 (5.3) | ||

| Intensive care unit | 6 (0.6) | 92 (0.6) | ||

| Mobile testing facility | 32 (3.2) | 137 (0.8) | ||

| Outpatient clinics | 897 (89.2) | 15 246 (91.5) | ||

| Telemedicine | 0 | 23 (0.1) | ||

| Other d | 11 (1.1) | 79 (0.5) | ||

| 14-day all-cause hospitalization | 57 (5.7) | 928 (5.6) | NC | NC |

Abbreviations: IQR, interquartile range; NC, not calculated; OR, odds ratio; SARS-CoV-2, severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2; SpO2, oxygen saturation; UHealth, University of Utah Health.

aAll values are number (percentage) except where indicated.

bAdjusted for cough, fever, shortness of breath, and known contact with a person who has received a positive test result for SARS-CoV-2.

cBecause of a lack of model convergence due to small cell counts, the following race/ethnicity variables were combined for OR calculations: Black/African American, Asian, American Indian/Alaska Native, Native Hawaiian/other Pacific Islander, and “other.”

dOther facility includes external, inpatient rehabilitation, and labor and delivery/maternal–newborn.

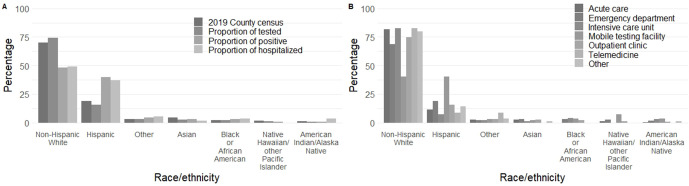

Race/Ethnicity

Of people tested for SARS-CoV-2 at UHealth compared with people tested in Salt Lake County, a higher proportion of people tested were non-Hispanic White (74% vs 70%) and a lower proportion were Hispanic/Latino (16% vs 19%) (Figure 1A). Hispanic/Latino people composed 40% and 37% of the positive SARS-CoV-2 tests and subsequent 14-day hospitalizations, respectively, in our UHealth data. Non-Hispanic White people composed 48% and 49% of the positive SARS-CoV-2 tests and subsequent 14-day hospitalizations, respectively, in our UHealth data. Hispanic/Latino people had twice the odds of receiving a positive test result for SARS-CoV-2 as compared with non-Hispanic White people (aOR = 2.0; 95% CI, 1.3-3.1), after adjusting for cough, fever, shortness of breath, and known contact with a person who tested positive for SARS-CoV-2 (Table 1). Hispanic/Latino people were overrepresented in mobile testing facilities (40% of testing at mobile testing facilities) and underrepresented in testing at other facilities, especially the ICU (7%). Non-Hispanic White people were underrepresented in mobile testing facilities (40% of testing at mobile testing facilities) and overrepresented in most other facilities, especially the ICU (83%) (Figure 1B). Median SpO2 values ranged from 96 to 97, and median pulse rate ranged from 84 to 87 beats per minute across all racial/ethnic groups.

Figure 1.

Racial/ethnic distribution of people who tested positive and were hospitalized for SARS-CoV-2, by department ordering the test, from March 10 through April 24, 2020, University of Utah Health, Salt Lake City, Utah. (A) The percentage of people by each race from the 2019 census estimates for Salt Lake County, 23 the proportion of people tested by race/ethnicity, the proportion of people who tested positive by race/ethnicity, and the proportion of people who were hospitalized within 14 days of a positive test result by race/ethnicity. (B) The proportion of tests ordered from each hospital department by race/ethnicity. Proportion of hospitalized is among people who received a positive test result for SARS-CoV-2. Abbreviation: SARS-CoV-2, severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2.

Age

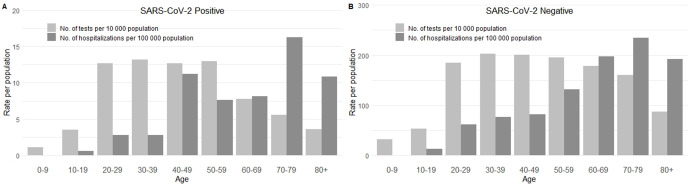

Children aged 0-9 years and 10-19 years had the lowest rates of SARS-CoV-2 testing and 14-day hospitalizations among people who received a positive or negative test result for SARS-CoV-2 in the UHealth system (Figure 2). Only 1 person aged 0-9 years and 4 people aged 10-19 years per 10 000 population received a positive test result for SARS-CoV-2 in Salt Lake County, and no one aged 0-9 years and only 0.6 people aged 9-19 years per 100 000 population were hospitalized within 14 days of receiving a positive SARS-CoV-2 test result. Similarly, 32 people aged 0-9 years and 53 people aged 9-19 years per 10 000 population received a negative test result for SARS-CoV-2, and 0.6 people aged 0-9 years and 12 people aged 10-19 years per 100 000 population were hospitalized within 14 days of receiving a negative SARS-CoV-2 test result (Figure 2B). In contrast, adults aged 30-39 and 40-49 had some of the highest rates of SARS-CoV-2 testing and 14-day hospitalization; 13 adults aged 30-39 and 13 adults aged 40-49 per 10 000 population received a positive test result for SARS-CoV-2, and 13 adults aged 30-39 and 11 adults aged 40-49 per 100 000 population were hospitalized within 14 days of receiving a positive test result for SARS-CoV-2 (Figure 2A). Similarly, 203 adults aged 30-39 and 200 adults aged 40-49 per 10 000 population received a negative test result for SARS-CoV-2, and 77 adults aged 30-39 and 82 adults aged 40-49 per 100 000 population were hospitalized within 14 days of receiving a negative test result for SARS-CoV-2 (Figure 2B). However, once adjusted for cough, fever, shortness of breath, and known contact with a person who received a positive test result for SARS-CoV-2, we found no significant trend by age in odds of receiving a positive test result for SARS-CoV-2 (Table 1).

Figure 2.

Age distribution of people who were tested and hospitalized for SARS-CoV-2 from March 10 through April 24, 2020, at University of Utah Health, Salt Lake City, Utah, by people who had (A) a positive test result or (B) a negative test result for SARS-CoV-2. Abbreviation: SARS-CoV-2, severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2.

Sex

A higher proportion of people who received a positive test result vs a negative test result for SARS-CoV-2 were males (54.2% vs 43.3%). However, after adjusting for cough, fever, shortness of breath, and known contact with a person who tested positive for SARS-CoV-2, males did not have significantly higher odds than females of receiving a positive test result for SARS-CoV-2 (aOR = 1.3; 95% CI, 0.9-1.9) (Table 1).

Characteristics of Subset of Manually Reviewed Medical Records

Among 1821 manually reviewed medical records, 123 (6.8%) people received a positive test result for SARS-CoV-2 from March 10 through March 31, 2020 (Table 2). This percentage was slightly higher than the percentage of people who received a positive test result for SARS-CoV-2 among all people tested (5.7%).

Table 2.

Symptoms and behaviors of people tested for SARS-CoV-2 in the UHealth system in a subset of manually reviewed medical records (n = 1821) from March 10 through March 31, 2020, in Salt Lake City, Utaha

| Symptom or behavior | SARS-CoV-2 positive (n = 123) | SARS-CoV-2 negative (n = 1698) |

|---|---|---|

| Symptom | ||

| Cough | 109 (88.6) | 1520 (89.5) |

| Fever | 92 (74.8) | 1095 (64.5) |

| Shortness of breath | 63 (51.2) | 1110 (65.4) |

| Myalgia | 55 (44.7) | 526 (31.0) |

| Headache | 49 (39.8) | 428 (25.2) |

| Lethargy | 40 (32.5) | 461 (27.1) |

| Nasal congestion | 43 (35.0) | 516 (30.4) |

| Sore throat | 40 (32.5) | 545 (32.1) |

| Diarrhea | 16 (13.0) | 175 (10.3) |

| Nausea/vomit | 10 (8.1) | 151 (8.9) |

| Duration of symptoms at presentation, d, median (IQR) | 4 (3-7) | 4 (2-7) |

| Behaviors | ||

| Previous exposure | 69 (56.1) | 477 (28.1) |

| Travel | 55 (44.7) | 420 (24.7) |

| Health care worker | 11 (8.9) | 196 (11.5) |

| Smoking status | ||

| Never | 72 (58.5) | 768 (45.2) |

| Former | 5 (4.1) | 153 (9.0) |

| Current | 4 (3.3) | 169 (10.0) |

| Missing data | 42 (34.1) | 608 (35.8) |

Abbreviations: IQR, interquartile range; SARS-CoV-2, severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2; UHealth, University of Utah Health.

aAll values are number (percentage) unless otherwise indicated.

Clinical Symptoms

People who received positive or negative test results for SARS-CoV-2 had similar vital signs and rates of cough (88.6%) but varied in presentation of other symptoms (Table 2). Compared with people who received a negative test result for SARS-CoV-2, people who received a positive test result for SARS-CoV-2 were more likely to report fever, myalgia, headache, lethargy, nasal congestion, and diarrhea but less likely to report shortness of breath. The median duration between symptom onset and presentation for testing was 4 days among people who received a positive test result and people who received a negative test result for SARS-CoV-2.

Epidemiological Risk Factors

Compared with people who received a negative test result for SARS-CoV-2, a higher proportion of people who received a positive test result for SARS-CoV-2 had previous exposure to a person who tested positive for SARS-CoV-2 (56.1% vs 28.1%) or a history of travel (44.7% vs 24.7%) and were never smokers (58.5% vs 45.2%), and a lower proportion were health care workers (8.9% vs 11.5%), former smokers (4.1% vs 9.0%), or current smokers (3.2% vs 10.0%) (Table 2).

Discussion

The availability of SARS-CoV-2 testing in Utah resulted in a higher proportion of the outpatient, community-dwelling population to be tested, which extends the literature that was previously limited to hospitalized patients. These data provide insight into the epidemiological and clinical characteristics of COVID-19 across a broad range of disease severity and highlight disparities in the COVID-19 response. Although the data presented in our study represent only 20% of people tested in Utah during a specified time frame, 19 the racial/ethnic distribution of our data is similar to the racial/ethnic distribution of the Salt Lake County population. 23 However, important discrepancies exist.

We found that people who identified as non-White had elevated odds of receiving a positive test result compared with non-Hispanic White people. In particular, people who identified as Hispanic/Latino had twice the odds of receiving a positive test result for SARS-CoV-2 than people who identified as non-Hispanic White. All other non-White racial/ethnic groups also had elevated odds of receiving a positive test result for SARS-CoV-2, although this association was no longer significant after adjusting for confounders.

Several factors likely contributed to the disparities in the SARS-CoV-2 positivity rate. 25 Hispanic/Latino households in Salt Lake County make an average of $56 498 per year compared with $82 026 among non-Hispanic White households, 26 making Hispanic/Latino workers less financially able to stay home without pay. National data, a reasonable proxy for Salt Lake County, show that lower incomes also translate into more crowded households, especially among urban Hispanic/Latino families, which facilitates viral transmission. 27,28 In addition, Hispanic/Latino workers are more likely than non-Hispanic/Latino workers to work in service occupations 29 that require working in close proximity with other people and, therefore, have increased exposure risk. About half of all maids/housekeepers, 37% of cooks, 33% of barbers, and 29% of dishwashers are Hispanic/Latino. 29 This increased exposure through employment is compounded by lower rates of sick leave among Hispanic/Latino workers than among non-Hispanic White workers, 30 which increases their likelihood of working while symptomatic and increasing exposure to coworkers and family members. Finally, public health personnel may be less able to conduct contact tracing in racial/ethnic minority communities than in non–racial/ethnic minority communities because of a lack of trust in government entities stemming from historical and current political situations. 31 -35

Racial/ethnic disparities in SARS-CoV-2 positivity and subsequent hospitalization do not appear to be the result of delaying care seeking until symptoms are critical. Using oxygen saturation and pulse at presentation as a proxy for disease severity, we found no differences by race or ethnicity. However, a higher proportion of people tested at mobile testing facilities compared with other testing facilities received a positive test result, and Hispanic/Latino people were overrepresented at mobile testing facilities. Mobile testing facilities are selected weekly by officials at UHealth and the Utah Department of Health’s Office of Health Disparities to target underserved transmission hotspots. In this sense, mobile testing facilities appear to be partially fulfilling their mission to provide testing to people who may not otherwise have access to established clinics and may provide a strategy to address disparities in SARS-CoV-2 positivity. However, mobile testing facilities largely provide drive-up testing and consequently do not engage people without personal vehicles, although they do serve people for whom cost may be a concern. (As of October 2020, only 38% of people tested at mobile testing facilities presented proof of health insurance [unpublished data, UHealth COVID-19 internal dashboard, 2020].) Therefore, even with expanded mobile testing facilities, underserved populations will likely remain underserved.

In addition to differences by race/ethnicity, we also identified differences by age. Although previous studies 6 -11 that focused on severe or critical patients tended to include older patients, we examined testing patterns during the full life course. We found testing rates were high for young- and middle-aged adults (>100 tests per 10 000 people aged 20-59), and adults aged 40-49 had high rates of hospitalization within 14 days of receiving a positive test result, second only to hospitalization rates among adults aged 70-79. This finding is consistent with the findings of Myers et al, 6 who found that hospitalized and ICU-admitted patients in California tended to be middle-aged. Long-term care facilities in Utah swiftly implemented transmission precautions such as banning visitors and closing common areas early in the epidemic; by mid-May, only 9 facilities had active outbreaks. 36 However, the proportion of COVID-19 deaths that occur in nursing homes in Utah is consistent with the rest of the nation. 37

Salt Lake County has a young population: 15% of people in the county are aged 0-9 years, 15% are aged 10-19 years, and 16% are aged 20-29 years, 24 but children were tested at the lowest rates of all age groups in our study (Figure 2). Previous studies showed that children are more likely than adults to have asymptomatic SARS-CoV-2 infection. 21 Testing criteria during the study period rendered asymptomatic people ineligible for testing and, therefore, ineligible for our study. Furthermore, the main children’s hospital in Salt Lake County is not in the UHealth system, and records from that hospital were not captured in our data. As was found in similar studies, 8 we found that hospitalization rates were lowest among young people aged 0-19 years. However, pediatric hospitalizations would likely have occurred outside the UHealth system; therefore, data on these hospitalizations would not have been captured in our study, even if the initial SARS-CoV-2 testing did occur at UHealth. As such, our findings about SARS-CoV-2 among children should be interpreted with caution.

This study offers an important contribution to existing COVID-19 literature, which has primarily focused on hospitalized patients. In contrast to previous work, more than 90% of people included in our study were tested in outpatient or community settings. Because asymptomatic infections were unlikely to be included in our data, our findings should not be generalized to asymptomatic cases. However, because our primary goal was to simply describe the epidemiology of our tested population, this work still provides an important extension of the literature.

Limitations

Our study had several limitations. First, our data were limited to people who were referred to and/or sought testing at a UHealth facility and met testing criteria, contributing to selection bias. This limitation was especially true for children, because the main children’s hospital in Salt Lake County is not part of the UHealth system. Second, although the racial/ethnic distribution of our tested population was similar to that of Salt Lake County, it is possible that data on other important factors were not collected or representative in our sample. For example, household income and health insurance status likely played an important role in test seeking, but these data were not available and, therefore, were not analyzed in our study. Finally, testing criteria operating during this study period ensured that few asymptomatic infections were captured in our data.

Conclusions

Further work to understand the demographic and epidemiological characteristics of asymptomatic infections is vital to understanding and controlling SARS-CoV-2. By highlighting critical gaps in testing, particularly among Hispanic/Latino communities, where SARS-CoV-2 may be spreading more rapidly than in non-Hispanic/Latino communities because of increased exposure and comparatively reduced testing, this study takes a critical first step toward reversing these health disparities. Our findings, based largely on people who received testing as outpatients, highlight potential gaps in control of SARS-CoV-2 infection related to age, race, and ethnicity.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank the following people from the University of Utah School of Medicine for their assistance with manual medical record review and data extraction: Margaret Bale, MPH; Jordan B. Peacock, BS; Ben Berger, BA; Alyssa Brown, BS; Sara Mann, BS; William West, BS; and Valerie Martin, BS.

Footnotes

Authors’ Note: Daniel Leung and Lindsay Keegan contributed equally to the article.

Declaration of Conflicting Interests: The authors declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Funding: The authors disclosed receipt of the following financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article: This work was supported by the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases (R01 AI135114 to D.T.L.) and the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute (K08 HL13650 to R.U.S.) of the National Institutes of Health; and the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (5U01CK000555-02 to M.H.S. and 5U01CK000538-03 to M.H.S. and L.T.K.).

ORCID iD

Sharia M. Ahmed, PhD https://orcid.org/0000-0002-4060-5712

References

- 1. World Health Organization . Coronavirus disease (COVID-19) situation report—197. August 2020. Accessed August 6, 2020. https://www.who.int/docs/default-source/coronaviruse/situation-reports/20200804-covid-19-sitrep-197.pdf?sfvrsn=94f7a01d_2

- 2. Dong E., Du H., Gardner L. An interactive web-based dashboard to track COVID-19 in real time. Lancet Infect Dis. 2020;20(5):533-534. 10.1016/S1473-3099(20)30120-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Young BE., Ong SWX., Kalimuddin S. et al. Epidemiologic features and clinical course of patients infected with SARS-CoV-2 in Singapore. JAMA. 2020;323(15):1488-1494. 10.1001/jama.2020.3204 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Wu Z., McGoogan JM. Characteristics of and important lessons from the coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) outbreak in China: summary of a report of 72 314 cases from the Chinese Center for Disease Control and Prevention. JAMA. 2020;323(13):1239-1242. 10.1001/jama.2020.2648 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Riccardo F., Ajelli M., Andrianou XD. et al. Epidemiological characteristics of COVID-19 cases in Italy and estimates of the reproductive numbers one month into the epidemic. medRxiv. Published online April 11, 2020. 10.1101/2020.04.08.20056861 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Myers LC., Parodi SM., Escobar GJ., Liu VX. Characteristics of hospitalized adults with COVID-19 in an integrated health care system in California. JAMA. 2020;323(21):2195-2198. 10.1001/jama.2020.7202 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Arentz M., Yim E., Klaff L. et al. Characteristics and outcomes of 21 critically ill patients with COVID-19 in Washington State. JAMA. 2020;323(16):1612-1614. 10.1001/jama.2020.4326 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Garg S., Kim L., Whitaker M. et al. Hospitalization rates and characteristics of patients hospitalized with laboratory-confirmed coronavirus disease 2019—COVID-NET, 14 states, March 1-30, 2020. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2020;69(15):458-464. 10.15585/mmwr.mm6915e3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Gold JAW., Wong KK., Szablewski CM. et al. Characteristics and clinical outcomes of adult patients hospitalized with COVID-19—Georgia, March 2020. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2020;69(18):545-550. 10.15585/mmwr.mm6918e1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Bhatraju PK., Ghassemieh BJ., Nichols M. et al. COVID-19 in critically ill patients in the Seattle region—case series. N Engl J Med. 2020;382(21):2012-2022. 10.1056/NEJMoa2004500 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Vahidy FS., Nicolas JC., Meeks JR. et al. Racial and ethnic disparities in SARS-CoV-2 pandemic: analysis of a COVID-19 observational registry for a diverse U.S. metropolitan population. BMJ Open. 2020;10(8):e039849. 10.1136/bmjopen-2020-039849 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. The Atlantic . The COVID Tracking Project. Accessed May 1, 2020. https://covidtracking.com

- 13. Bialek S., Bowen V., Chow N, . Geographic differences in COVID-19 cases, deaths, and incidence—United States, February 12–April 7, 2020. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2020;69(15):465-471. 10.15585/mmwr.mm6915e4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Padula WV. Why only test symptomatic patients? Consider random screening for COVID-19. Appl Health Econ Health Policy. 2020;18(3):333-334. 10.1007/s40258-020-00579-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Li R., Pei S., Chen B. et al. Substantial undocumented infection facilitates the rapid dissemination of novel coronavirus (SARS-CoV-2). Science. 2020;368(6490):489-493. 10.1126/science.abb3221 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Chow EJ., Schwartz NG., Tobolowsky FA. et al. Symptom screening at illness onset of health care personnel with SARS-CoV-2 infection in King County, Washington. JAMA. 2020;323(20):2087-2089. 10.1001/jama.2020.6637 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Sharfstein JM., Becker SJ., Mello MM. Diagnostic testing for the novel coronavirus. JAMA. 2020;323(15):1437-1438. 10.1001/jama.2020.3864 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Baggett TP., Keyes H., Sporn N., Gaeta JM. Prevalence of SARS-CoV-2 infection in residents of a large homeless shelter in Boston. JAMA. 2020;323(21):2191-2192. 10.1001/jama.2020.6887 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Utah Department of Health . COVID-19 surveillance. Accessed May 1, 2020. https://coronavirus.utah.gov/case-counts

- 20. Salt Lake County Health Department . COVID-19 data dashboard: total tested. Accessed May 1, 2020. https://slco.org/health/COVID-19/data

- 21. Bialek S., Gierke R., Hughes M. et al. Coronavirus disease 2019 in children—United States, February 12–April 2, 2020. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2020;69(14):422-426. 10.15585/mmwr.mm6914e4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Huang C., Wang Y., Li X. et al. Clinical features of patients infected with 2019 novel coronavirus in Wuhan, China. Lancet. 2020;395(10223):497-506. 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30183-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. US Census Bureau . QuickFacts: Salt Lake County, Utah: population estimates, July 1, 2019 (V2019). Accessed May 1, 2020. https://www.census.gov/quickfacts/fact/table/saltlakecountyutah,UT/PST045219

- 24. US Census Bureau . 2018 American Community Survey 1-year estimates subject tables. Accessed July 25, 2020. https://data.census.gov/cedsci/table?q=age salt lake county&g=0500000US49035&tid=ACSST1Y2018.S0101&t=Age and Sex&vintage=2018&layer=VT_2018_050_00_PY_D1&cid=S0101_C01_001E&hidePreview=false

- 25. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention . Coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19): health equity considerations and racial and ethnic minority groups. 2020. Accessed May 1, 2020. https://www.cdc.gov/coronavirus/2019-ncov/community/health-equity/race-ethnicity.html?CDC_AA_refVal=https%3A%2F%2Fwww.cdc.gov%2Fcoronavirus%2F2019-ncov%2Fneed-extra-precautions%2Fracial-ethnic-minorities.html

- 26. Salt Lake County Health Department . 2020 demographics: summary data for county: Salt Lake. 2020. Accessed May 1, 2020. http://www.healthysaltlake.org/index.php?module=DemographicData&controller=index&action=index

- 27. National Hispanic Council on Aging . Housing. 2020. Accessed May 1, 2020. https://www.nhcoa.org/our-focus/housing

- 28. Burr JA., Mutchler JE., Gerst K. Patterns of residential crowding among Hispanics in later life: immigration, assimilation, and housing market factors. J Gerontol B Psychol Sci Soc Sci. 2010;65B(6):772-782. 10.1093/geronb/gbq069 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. US Bureau of Labor Statistics . Household data annual averages: 11. Employed persons by detailed occupation, sex, race, and Hispanic or Latino ethnicity. Accessed May 1, 2020. https://www.bls.gov/cps/cpsaat11.htm

- 30. US Bureau of Labor Statistics . Labor force characteristics by race and ethnicity, 2018. October 2019. Accessed May 1, 2020. https://www.bls.gov/opub/reports/race-and-ethnicity/2018/home.htm

- 31. Munier N., Albarracin J., Boeckelman K. Determinants of rural Latino trust in the federal government. Hisp J Behav Sci. 2015;37(3):420-438. 10.1177/0739986315586564 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Armstrong K., Ravenell KL., McMurphy S., Putt M. Racial/ethnic differences in physician distrust in the United States. Am J Public Health. 2007;97(7):1283-1289. 10.2105/AJPH.2005.080762 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Shoff C., Yang T-C. Untangling the associations among distrust, race, and neighborhood social environment: a social disorganization perspective. Soc Sci Med. 2012;74(9):1342-1352. 10.1016/j.socscimed.2012.01.012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Thiede M. Information and access to health care: is there a role for trust? Soc Sci Med. 2005;61(7):1452-1462. 10.1016/j.socscimed.2004.11.076 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Stepanikova I., Mollborn S., Cook KS., Thom DH., Kramer RM. Patients’ race, ethnicity, language, and trust in a physician. J Health Soc Behav. 2006;47(4):390-405. 10.1177/002214650604700406 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Carlisle N. Utah nursing homes keep having coronavirus outbreaks. Industry groups warn it will get worse. Salt Lake Tribune. July 14, 2020. Accessed October 5, 2020. https://www.sltrib.com/news/2020/07/14/utah-nursing-homes-keep

- 37. 43% of U.S. coronavirus deaths are linked to nursing homes . The New York Times. June 27, 2020. Accessed October 5, 2020. https://web.archive.org/web/20200701035724/https://www.nytimes.com/interactive/2020/us/coronavirus-nursing-homes.html