Abstract

Introduction

Few US studies have examined the usefulness of participatory surveillance during the coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic for enhancing local health response efforts, particularly in rural settings. We report on the development and implementation of an internet-based COVID-19 participatory surveillance tool in rural Appalachia.

Methods

A regional collaboration among public health partners culminated in the design and implementation of the COVID-19 Self-Checker, a local online symptom tracker. The tool collected data on participant demographic characteristics and health history. County residents were then invited to take part in an automated daily electronic follow-up to monitor symptom progression, assess barriers to care and testing, and collect data on COVID-19 test results and symptom resolution.

Results

Nearly 6500 county residents visited and 1755 residents completed the COVID-19 Self-Checker from April 30 through June 9, 2020. Of the 579 residents who reported severe or mild COVID-19 symptoms, COVID-19 symptoms were primarily reported among women (n = 408, 70.5%), adults with preexisting health conditions (n = 246, 70.5%), adults aged 18-44 (n = 301, 52.0%), and users who reported not having a health care provider (n = 131, 22.6%). Initial findings showed underrepresentation of some racial/ethnic and non–English-speaking groups.

Practical Implications

This low-cost internet-based platform provided a flexible means to collect participatory surveillance data on local changes in COVID-19 symptoms and adapt to guidance. Data from this tool can be used to monitor the efficacy of public health response measures at the local level in rural Appalachia.

Keywords: COVID-19, participatory surveillance, internet data collection, longitudinal assessment, online data entry, symptom checker, digital epidemiology

Cases of a novel coronavirus were first reported in Wuhan, China, in December 2019. 1 Since then, countries worldwide have been responding to the novel severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) that is causing the coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic. Reported illnesses range from mild and asymptomatic to severe and/or life-threatening. 2 Community transmission of COVID-19 was first detected in the United States in February 2020. 3 People aged >65 and people who are medically vulnerable (ie, people who have a weakened immune system, have chronic health conditions, are obese, or are pregnant) are at increased risk of developing serious complications from COVID-19. 4 Because of long-standing inequities, Black people, indigenous people, and other people of color have been disproportionately affected by COVID-19. 5 African American people are at increased risk of severe illness that results in hospitalization and are more likely to receive ventilation treatment and, in severe cases, die of COVID-19 than their non-Hispanic White counterparts. 6,7 COVID-19 has also highlighted geographic disparities in infection rates, especially in rural areas of the South. People in southern states characterized by a high prevalence of comorbid conditions, poverty, and elderly populations have been hit the hardest by COVID-19 and have had more severe cases of COVID-19 than people in urban areas. 8,9

After stay-at-home orders were lifted starting in May 2020, one focus during the reopening phase was the expansion of state and local capacity for contact tracing and testing. However, the asymptomatic nature of COVID-19 among some people infected with SARS-CoV-2 and the long infectious period (ie, 14 d) limit the effectiveness of these 2 approaches. Another important challenge is recall bias during the process of constructing contact histories. Contact-tracing smartphone applications (apps) that use geolocation technology were launched in the early phase of the pandemic (March–June 2020) in Israel, 10 Singapore, 11,12 and Australia 13 to address these challenges. Yet, these apps assume a high-tech population and access to Wi-Fi or the internet. They have also been scrutinized because of privacy concerns and access barriers in low-income, rural, or elderly populations. 14

Participatory surveillance—the participation of the community in disease surveillance—holds promise in complementing existing health care–based surveillance systems for identifying people at risk for COVID-19 and enhancing an understanding of the contextual risk factors that can be used in local interventions to reduce inequalities in infection rates. Participatory surveillance is a novel, cost-effective, and scalable intervention strategy to engage the public in voluntarily and regularly reporting on health symptoms via the internet and provide health information or recommendations from local public health agencies. 15,16 An early example of this type of participatory surveillance network—Influenzanet—was launched in the Netherlands in 2003 17 to monitor influenza-like illness and has since expanded in Europe, followed by Flu Near You in 2011 for the United States 18 and several other countries. 19 In response to the COVID-19 pandemic, this participatory framework was adapted to now include COVID Near You in the United States. 20 Participatory surveillance systems in China, 21 the United Kingdom, the United States, 22 Germany, 23 Japan, 24 Brazil, 25 Australia, and Singapore 26 have demonstrated the feasibility of leveraging this type of data to slow the growth of the outbreak and provide close to real-time information to enhance decision making.

These participatory surveillance tools generate a more timely and accurate picture of disease activity than traditional syndromic surveillance systems, which rely on data from emergency department visits or laboratory-based results. 17,19,27 -29 Participatory surveillance systems may detect a signal change in infectious disease activity up to 5-7 days earlier than traditional syndromic surveillance systems. 17,28 However, few US studies have examined the usefulness of participatory surveillance efforts during the COVID-19 pandemic for aiding local health officials, and to our knowledge, none have focused on a rural underserved setting.

Rapidly detecting infectious disease outbreaks is an ongoing 21st-century challenge. New approaches that leverage digital connectivity to engage the public in actively providing health officials with near–real-time data to inform decision making are needed, particularly at the local level. 21 Surveillance is the cornerstone of the public health community’s evidence-based approach to the control and prevention of an infectious disease. 30 The COVID-19 pandemic has revealed a number of gaps in public health preparedness and capacity at the federal, state, and local levels. Digital health interventions provide a creative, low-cost solution for strengthening the current public health response to COVID-19, particularly as it pertains to enhancing syndromic surveillance efforts and reducing the strain on resources and public health staff members at the local level.

We report the results of the initial launch of an online COVID-19 Self-Checker tool in rural Appalachia, which is available at no cost and is hosted by the local health department. The COVID-19 Self-Checker tool allows residents to assess signs and symptoms of COVID-19 and receive timely and appropriate guidance to manage symptoms and individualized follow-up to connect residents to available care and testing resources. The results reported here are from a phase 1 proof-of-concept participatory surveillance study of an online data collection process in one county to test and then roll out to enhance regional monitoring.

Materials and Methods

Study Setting and Development of Participatory Surveillance Tool

The COVID-19 Self-Checker tool is an internet-based participatory surveillance system in North Carolina developed by the lead author (J.D.R.) in collaboration with county health officials at the Buncombe County Health and Human Services, Mountain Area Health Education Center, and local public health leaders. The release of the Self-Checker tool for community-wide launch occurred on April 30, 2020, in Buncombe County, North Carolina. To our knowledge, this is the first participatory surveillance system launched in the region and in the state. Buncombe County is located in the southern Appalachian mountains of western North Carolina. The population is approximately 261 191, making it the most populous county in western North Carolina. 31 Most of the population is White (89.4%) or African American (6.3%). Nearly 40% of the population has a bachelor’s degree, 87.5% have a household with a computer, and 12.5% of people aged <65 do not have health insurance. 31

Online Data Collection for Self-Checker Tool and Daily Check-in

The participatory surveillance system comprised an initial COVID-19 symptom checker and included an option for individual follow-up with county public health staff members. The Self-Checker tool provided a quick, confidential, easy-to-use assessment tool that was accessible online, using a smartphone or computer, or by telephone call from a nurse triage team to help residents determine if they had COVID-19 symptoms. Community residents could opt to receive a daily check-in either electronically (by email) or by telephone to be connected with local health care and testing resources. Non–English speakers could access the Self-Checker tool online in Spanish and Russian or by telephone in multiple languages using a provided hotline number. We modified guidance from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) using plain language at a fifth-grade reading level. For people who did not have internet access, we established a call line to help residents complete the Self-Checker tool or participate in daily check-ins.

After we developed the Self-Checker tool, the study team conducted iterative user testing on 10-15 volunteer participants in the community for 3 waves. The team took measures to recruit volunteers who were representative of hard-to-reach populations (eg, older adults, communities of color). Survey questions are available from the authors upon request.

We used Qualtrics XM software (Qualtrics) to collect and maintain data security and confidentiality of the participatory surveillance data. To further ensure compliance with the Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act, the county health department obtained a business associate agreement and a memorandum of understanding with North Carolina State University.

Surveillance Definitions

Participant completion of the Self-Checker tool involved a response to all required fields, and upon completion, each participant was assigned to 1 of 3 categories for follow-up: (1) seek care immediately (severe symptom group), (2) connect with a health care provider and get tested (mild symptom group), and (3) contact exposure group (no symptoms but self-report of exposure to a person who received a positive test result for SARS-CoV2; Box). We relied on CDC’s guidance on symptoms of COVID-19 3 to distinguish between the presence of possible mild or severe COVID-19 symptoms. Because we developed the Self-Checker tool, we were able to modify the symptom list as soon as CDC guidance changed. The case definition for the mild symptom group changed on May 26 with the addition of 4 new symptoms: fatigue, congestion and runny nose, nausea or vomiting, and diarrhea. 3

Box. Data collected from the COVID-19 Self-Checker tool and daily check-in questionnaires a .

| COVID-19 Self-Checker tool, Buncombe County, North Carolina, 2020 | ||

| ||

| Longitudinal Follow-up/Daily Check-in | ||

|

Seek Care Immediately/Referred to 911

Severe symptoms: gasping for air, severe and constant pain or pressure in the chest, feeling or acting confused, bluish lips/face, feeling very dizzy, words run together, seizures |

Stay Home/Connect With Health Care Provider and Testing

Mild symptoms: cough, shortness of breath, or ≥2 of the following: fever, chills, repeated shaking with chills, muscle pain, headache, sore throat, new loss of taste or smell, congestion and runny nose, diarrhea, nausea or vomiting, fatigue |

Contact With Positive Case/Self-Monitor

Answered yes to the following: “In the last 2 weeks, were you in close contact with someone who tested positive for COVID-19 or with someone believed to have had it by a health care provider?” |

Abbreviations: COVID-19, coronavirus disease 2019; SARS-CoV-2, severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2.

aThe COVID-19 Self-Checker tool is an internet-based participatory surveillance system that comprises an initial COVID-19 symptom checker and includes an option for individual follow-up with county public health staff members.

In addition to a consent clause built into the introduction of the online Self-Checker tool, we included a participant opt-in to obtain consent from each participant to allow us to use their data for research purposes. We obtained approval to use deidentified data collected for research purposes from the North Carolina State University Institutional Review Board. We excluded from final analyses the responses of participants who did not give consent for us to use their data for research purposes (n = 334). Excluded participants were typically aged 18-64 (n = 124, 37.1%) and did not have a health care provider (n = 77, 23.0%).

Statistical Analysis

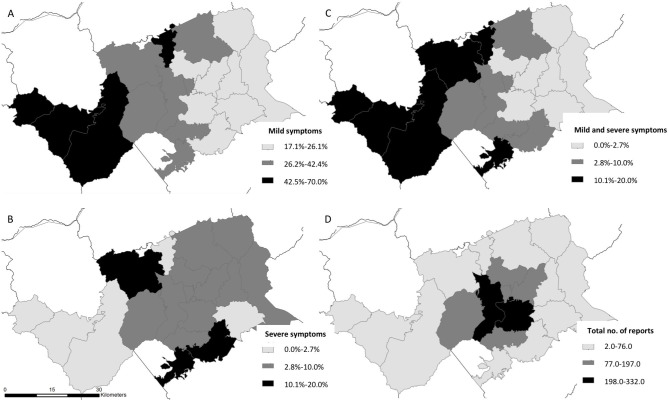

We included data collected from April 30 through June 9, 2020. We included only complete case data in the final analysis for respondents who opted into the daily check-in. We calculated the number and percentage for categorical variables. We compared between-group differences in categorical variables using the χ2 goodness-of-fit test or the Fisher exact test (sample size <10). We calculated continuous data (eg, age, time to complete) using mean (SD) and median (interquartile range [IQR]). We used cumulative distribution plots to examine the time to connect with a health care provider or time to obtain a test. We mapped the geographic distribution of residents with mild and severe COVID-19 symptoms by using ArcGIS version 10.8.1 (Esri). We mapped, by zip code level, the number of total Self-Checker reports, the proportion of participants with mild symptoms, the proportion of participants with severe symptoms, and the proportion of participants with COVID-19 symptoms (combined severe and mild symptom groups). We performed all statistical analyses using SAS version 9.4 (SAS Institute, Inc) and set the significance as a 2-tailed P < .05.

Results

From April 30 through June 9, 2020, the Self-Checker tool received a total of 6494 visits. Of these 6494 visits, 2090 (32.2%) county residents completed the Self-Checker tool and 4404 (67.8%) residents partially completed the tool; 237 (3.6%) residents did not consent to initial participation, and 176 (2.7%) were not county residents (this number may also include people who did not consent for their data to be used for research). The median time to complete the Self-Checker tool was 3.2 minutes.

Characteristics of Residents Who Completed the Self-Checker Tool

Of the 1755 residents who completed the Self-Checker tool, were county residents, and consented to the use of their data for research, 108 (6.2%) self-reported severe symptoms, 471 (26.8%) self-reported mild symptoms, and 1176 (67.0%) self-reported symptoms that did not meet the CDC case definition of COVID-19–like symptoms (Table 1). The median time from symptom onset to engaging with the Self-Checker tool was 3 days (IQR, 2-5 d), and 232 (11.0%) residents reported symptoms occurring from January through April, before the Self-Checker tool was available. Most residents who completed the Self-Checker tool were White, English-speaking, and female. Nearly half of the 579 residents who completed the Self-Checker tool who had mild or severe symptoms were medically vulnerable (n = 246, 42.5%), and 131 (22.6%) reported not having a health care provider. The community areas with the highest proportion of mild (42.5%-70.0%) and severe (10.0%-20.0%) symptoms occurred outside the more urban center of the county core, but the highest engagement with the tool (198-332 total reports) occurred within urban zip codes in the center of the county within city limits (Figure 1).

Table 1.

Characteristics of residents who completed the COVID-19 Self-Checker tool, Buncombe County, North Carolina, April 30–June 9, 2020 a

| Characteristic | Buncombe County Self-Checker tool results | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total (N = 1755) | Severe symptoms b (n = 108) | Mild symptoms c (n = 471) | No symptoms d (n = 1176) | |

| Age group, y | ||||

| 18-44 | 639 (36.4) | 56 (51.9) | 245 (52.0) | 338 (28.7) |

| 45-64 | 569 (32.4) | 42 (38.9) | 153 (32.5) | 374 (31.8) |

| ≥65 | 547 (31.2) | 10 (9.3) | 73 (15.5) | 464 (39.5) |

| Sex | ||||

| Female | 1132 (64.5) | 68 (63.0) | 340 (72.2) | 724 (61.6) |

| Male | 609 (34.7) | 38 (35.2) | 126 (26.8) | 445 (37.8) |

| Prefer to self-describe | 14 (0.8) | 2 (1.9) | 5 (1.1) | 6 (0.5) |

| Race/ethnicity | ||||

| White | 1636 (93.2) | 97 (89.8) | 433 (91.9) | 1106 (94.0) |

| Black/African American | 22 (1.3) | 3 (2.8) | 5 (1.1) | 14 (1.2) |

| Asian | 11 (0.6) | 2 (1.9) | 2 (0.4) | 7 (0.6) |

| Other e | 40 (2.3) | 3 (2.8) | 16 (3.4) | 21 (1.8) |

| Hispanic/Latinx | 46 (2.6) | 3 (2.8) | 15 (3.2) | 28 (2.4) |

| Medically vulnerable f | ||||

| Yes | 610 (40.1) | 58 (62.4) | 188 (48.1) | 364 (35.0) |

| No | 913 (59.9) | 35 (37.6) | 203 (51.9) | 675 (65.0) |

| Missing data (n = 232) | ||||

| Have a health care provider | ||||

| Yes | 1488 (85.6) | 82 (75.9) | 362 (77.5) | 1044 (89.7) |

| No | 251 (14.4) | 26 (24.1) | 105 (22.5) | 120 (10.3) |

| Missing data (n = 16) | ||||

| Language | ||||

| English | 1750 (99.7) | 108 (100.0) | 469 (99.6) | 1173 (99.7) |

| Spanish | 4 (0.2) | 0 | 2 (0.4) | 2 (0.2) |

| Russian | 1 (0.1) | 0 | 0 | 1 (0.1) |

| Contact with person who received a positive test result for SARS-CoV-2 | ||||

| Yes | 64 (5.0) | 7 (14.6) | 18 (6.5) | 39 (4.1) |

| No | 1207 (95.0) | 41 (85.4) | 258 (93.5) | 908 (95.9) |

| Missing data (n = 484) | ||||

| Contact g | ||||

| 1475 (93.6) | 88 (86.3) | 386 (91.3) | 1001 (95.2) | |

| Telephone call from nurse triage team | 101 (6.4) | 14 (13.7) h | 37 (8.7) h | 50 (4.8) |

| Missing data (n = 179) | ||||

Abbreviations: COVID-19, coronavirus disease 2019; SARS-CoV-2, severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2.

aThe COVID-19 Self-Checker tool is an internet-based participatory surveillance system that comprises an initial COVID-19 symptom checker and includes an option for individual follow-up with county public health staff members. All values in table are number (percentage) unless otherwise indicated.

bPeople who self-reported severe symptoms (gasping for air, severe and constant pain or pressure in the chest, feeling or acting confused, bluish lips/face, feeling very dizzy, words run together, seizures) were instructed to call 911.

cPeople who self-reported mild symptoms (cough, shortness of breath, or at least 2 of the following: fever, chills, repeated shaking with chills, muscle pain, headache, sore throat, new loss of taste or smell, congestion and runny nose, diarrhea, nausea or vomiting, fatigue) were instructed to call a physician or get testing.

dDoes not meet new Centers for Disease Control and Prevention definition of COVID-19–like symptoms (eg, only 1 of at least 2 required symptoms was reported).

eOther includes people who self-reported as multiracial, American Indian/Alaska Native, or Native Hawaiian/Other Pacific Islander.

fMedically vulnerable is defined as a response of yes to any of the following: asthma, HIV, heart disease with complications, a weakened immune system, very obese, chronic lung disease, diabetes, kidney or liver failure, currently pregnant.

gPeople who opted into the daily check-in who provided their preferred contact information.

hUsing the χ2 goodness-of-fit test, these values were significant at P < .001.

Figure 1.

Zip code–level map of residents who completed the COVID-19 Self-Checker tool, by proportion of residents self-reporting (A) mild symptoms, (B) severe symptoms, and (C) mild and severe symptoms and (D) the total number of Self-Checker users, Buncombe County, North Carolina, April 30–June 9, 2020. The Self-Checker is an internet-based participatory surveillance system that comprises an initial COVID-19 symptom checker and includes an option for individual follow-up with county public health staff members. Abbreviation: COVID-19, coronavirus disease 2019.

A higher proportion of adults aged 18-44 compared with adults aged 45-64 or ≥65 reported severe or mild symptoms. Participation in the Self-Checker tool was relatively equal across age groups for those whose symptoms did not meet the CDC definition of COVID-19–like symptoms, but the proportion of residents whose symptoms did not meet the CDC definition was higher among residents aged ≥65 (39.5%) than among residents aged 45-64 (31.8%) and residents aged 18-44 (28.7%). Sixty-four people reported being in contact with a person who had received a positive test result for SARS-CoV-2, of whom 7 (10.9%) reported severe symptoms (Table 1).

Preferred Method of Follow-up

Among the 1576 residents who answered the question on preferred method of follow-up, most (n = 1475, 93.6%) across symptom categories preferred a daily check-in by email. A higher proportion of residents who reported severe symptoms (13.7%) compared with mild symptoms (8.7%) preferred a telephone call from the nurse triage team (χ2 test = 14.1; P < .001; Table 1).

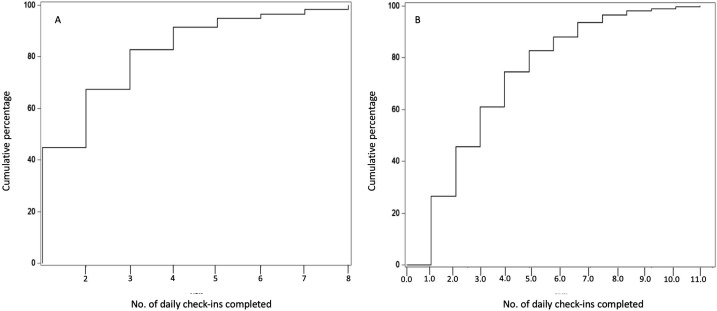

Daily Check-in

A total of 301 participants (54 with severe symptoms and 247 with mild symptoms) opted into the daily check-in and also consented to the use of their responses for research. Twenty-seven of 54 (50.0%) participants who were referred to 911 connected with their health care provider by day 2.2 of the check-in, as shown by the cumulative distribution plot for this group (Figure 2) and reported an average of 3.7 days before being tested for SARS-CoV-2 infection (Table 2). One hundred twenty-four of 247 (50.2%) users in the mild symptom group connected with their health care provider by day 2.3 of follow-up (Figure 2) and reported being tested for SARS-CoV-2 infection (Table 2).

Figure 2.

The cumulative distribution plots of the number of visits before a person undergoing follow-up for self-reported (A) severe or (B) mild COVID-19 symptoms connected with a health care provider, COVID-19 Self-Checker tool, Buncombe County, North Carolina, April 30–June 9, 2020. The COVID-19 Self-Checker tool is an internet-based participatory surveillance system that comprises an initial COVID-19 symptom checker and includes an option for individual follow-up with county public health staff members. Abbreviation: COVID-19, coronavirus disease 2019.

Table 2.

Daily follow-up for residents with severe or mild symptoms of COVID-19, self-reported in the COVID-19 Self-Checker tool, Buncombe County, North Carolina, April 30–June 9, 2020 a

| Characteristic | Severe symptoms (n = 54) |

Mild symptoms (n = 247) |

|---|---|---|

| No. of completed daily check-ins | ||

| Mean (SD) | 4.0 (3.7) | 3.3 (2.9) |

| Median (IQR) | 2 (1-6) | 2 (1-4) |

| No. of daily check-ins before connecting with health care provider | ||

| Mean (SD) | 2.2 (1.6) | 3.3 (2.3) |

| Median (IQR) | 2 (1-3) | 3 (1-5) |

| Barriers to care, % | ||

| Health care provider hours reduced during pandemic | 5.1 | 11.4 |

| Health care provider telephone was busy | 0 | 5.9 |

| Health care provider changed to telemedicine | 0 | 4.4 |

| Do not have health insurance | 23.1 | 0.5 |

| Other | 71.7 | 73.9 |

| Missing data | 0.1 | 3.9 |

| Able to get tested, % | ||

| Yes | 45.1 | 46.3 |

| No | 34.6 | 30.6 |

| Based on my symptoms, told I don’t need testing | 20.3 | 23.1 |

| No. of daily check-ins before reporting getting tested | ||

| Mean (SD) | 3.7 (3.3) | 4.1 (3.2) |

| Median (IQR) | 2.5 (1-5) | 3 (2-6) |

| Willingness to share test results, % | ||

| I do not need testing at this time | 0 | 0.3 |

| Yes, tested negative | 42.6 | 46.3 |

| Yes, tested positive | 0 | 0 |

| Waiting for results | 57.4 | 53.4 |

| Barriers to testing, % | ||

| I don’t have health insurance | 22.2 | 5.7 |

| I don’t know where to get a test | 20.4 | 13.7 |

| I don’t have a way to get to the test site | 3.7 | 3.2 |

| I can’t get to the test site when open | 7.4 | 2.0 |

| I don’t have childcare | 0 | 2.8 |

| Other | 40.7 | 43.3 |

| Missing data | 5.6 | 29.3 |

| Symptoms resolved and no longer need to receive follow-up, % b | 14.8 | 25.1 |

Abbreviations: COVID-19, coronavirus disease 2019; IQR, interquartile range; SD, standard deviation.

aData source: Self-reported responses collected during the daily check-in for residents in Buncombe County, North Carolina, April 30–June 9, 2020. The COVID-19 Self-Checker tool is an internet-based participatory surveillance system that comprises an initial COVID-19 symptom checker and includes an option for individual follow-up with county public health staff members. A total of 301 participants engaged in the daily check-in feature of the COVID-19 Self-Checker tool.

bAnswered yes to all 3 of the following questions: It has been at least 10 days since you first had signs and symptoms of COVID-19. It has been at least 3 full days (72 hours) since you had a fever. (Don’t select if you were taking medicine to lower your fever during that time.) It has been at least 3 full days (72 hours) since my symptoms have improved.

No participants refused to share their test results. About half of participants did not report their final test results, many of whom were still awaiting their results at the time of analysis. The most commonly reported barriers to testing were “I don’t have health insurance” and “I don’t know where to get a test.”

Eight of 54 (14.8%) participants in the severe symptom group and 62 of 247 (25.1%) participants in the mild symptom group continued receiving follow-up until their symptoms resolved and were instructed to discontinue self-isolation (Table 2).

Discussion

To our knowledge, this study is the first evaluation of a targeted participatory surveillance tool tracking the COVID-19 outbreak in a rural mountainous region in the southeastern United States. In the first 5 weeks after the tool was launched, more than 2000 residents in a rural, medically underserved county completed the tool. Preliminary results from this participatory syndromic surveillance tool found that a large proportion of residents who self-reported COVID-19 symptoms were medically vulnerable, working-age adults (aged 18-44), female, and without a health care provider. Our tool also provided a means for local health officials to understand how many people with COVID-19 symptoms were in contact with a health care provider, were tested, and frequently encountered barriers to accessing health care and testing resources.

Our finding that a higher proportion of residents with mild or severe symptoms were aged 18-44 as compared with 45-64 or ≥65 supports an emerging hypothesis that occupation is a risk factor for the growing number of COVID-19 infections among working-age people. 32 This group likely comprised essential or frontline workers, people required to report into work, and people who were employed in service industries with a high frequency of contact exposure with the general public. Initial results also revealed close to equal participation across all 3 age groups among people reporting symptoms that did not meet the CDC definition of COVID-19–like symptoms. Contrary to our findings, previous research demonstrated substantial underrepresentation of younger (aged <20) and older (aged >60) age groups in influenza participatory surveillance tools. 33,34

Similar to previous research, 34 we observed higher rates of participation and completion in the Self-Checker tool among women compared with men, with the exception of roughly equal participation among men and women who reported severe symptoms. Research has consistently found differences by sex in care-seeking behavior: women are more likely to engage in health care– or help-seeking behaviors than men for various health conditions, including chronic and mental health conditions. 35 -39

Our participatory surveillance tool shares similarities with the electronic screening system in Iran. 40 Participatory surveillance tools for infectious diseases should be leveraged at a larger scale to evaluate regional and state-level COVID-19 trends. 41 More research on the use of smartphone platforms to estimate the range and magnitude of COVID-19 in a community is needed. 42 Rural locations such as western North Carolina have less access to broadband internet connection than their urban counterparts and rely on smartphones for internet access. 43 This trend is especially common among younger adults, non-White people, and low-income people in the United States. 44

Strengths and Limitations

This study had several strengths. First, near–real-time data collection on voluntary symptom reporting was a key advantage of this tool compared with the 3-7–day lag time in the availability of traditional syndromic emergency department and laboratory testing data. We observed that residents typically reported symptoms to the Self-Checker tool before connecting with a health care provider in both the mild and severe symptom groups, and the tool may have further encouraged them to take their symptoms seriously and seek care sooner rather than waiting. Another benefit of this low-cost, scalable tool is that it capitalized on a common health care–seeking behavior: most sick people do not schedule an appointment with their health care provider on the same day of illness but are willing and likely to report illness on the same day they exhibit symptoms of illness. Furthermore, people do not seek medical care for various reasons, including cost, barriers to accessing care, risk perception, severity of symptoms, stigma, or fear of contracting the disease, all of which undermine the validity and reliability of traditional health care–based syndromic surveillance systems. 45,46

We were also able to collect important geographic and sociodemographic data on users to better contextualize changes in symptom patterns and risk factors among vulnerable subgroups (eg, adults aged ≥65, pregnant women, people with chronic health conditions, uninsured people). Results suggest that close to half of residents who completed the Self-Checker tool were medically vulnerable, and 1 in 4 participants did not have a primary health care provider. Preliminary results suggest that the tool is being used as a safety-net resource to help connect people who do not have a health care provider or health insurance to local community resources.

The tool is advantageous compared with other symptom checkers, such as CDC’s COVID-19 health bot, 41 COVID Near You, 19 and India’s Aarogya Setu, 47 in that it gives people the option to connect with local public health staff members and receive longitudinal follow-up during a 2-week period. Because mild COVID-19 symptoms can quickly progress to severe symptoms, continuous follow-up allows for the monitoring of changes in symptom severity.

Limitations

This study also had several limitations. First, for the initial phase of the launch, we observed underrepresentation of some racial/ethnic and non–English-speaking groups, which potentially limits the generalizability of our results. Although we worked closely with partners representing Black people, indigenous people, and people of color in our community, we had to expedite these efforts, potentially resulting in missed opportunities to enhance the tool’s reach to these groups. Second, our Self-Checker tool did not capture data on self-report of a user’s positive results during the initial reporting period. Although no residents reported an unwillingness to share test results, roughly half of all residents who reported getting tested for SARS-CoV-2 did not report their test results and were lost to follow-up. However, at the time, the average delay for receiving test results was 3-5 days, and several participants who engaged with the tool during the last week of follow-up were lost to follow-up because of the artificially imposed cut-point for this analysis.

Third, our results may be subject to recall bias, misinterpretation of survey questions, or wrong responses resulting in random or systematic error. However, studies have found that online surveys are a quick and cost-effective way to collect accurate community-level data. 47 -49 A recent study highlighted that lower-income communities were not represented in a national influenza surveillance system and called attention to the need for creative and intentional strategies to engage more diverse representation in these electronic surveillance systems to enhance detection monitoring among people at high risk of illness. 50 Finally, self-selection bias may have been a limitation in that our results only captured data on residents who opted to engage with the Self-Checker tool, and ensuring consistent and representative participation across all social strata was difficult, particularly among diverse racial/ethnic groups. Still, internet-based participatory surveillance shows promise in enhancing local and regional surveillance efforts. 51 -53

Conclusion

Our Self-Checker tool provided local public health officials with situational awareness about changes in COVID-19 symptom patterns, the geographic distribution of changes, and barriers to accessing care and testing resources. This low-cost internet-based platform with smartphone compatibility provides a flexible and scalable means to collect participatory surveillance data on local and regional changes in COVID-19 symptoms, nimbly adapt to changes in CDC guidance, and monitor the efficacy of public health response measures at the local level.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Otis Brown, PhD, for his wise and thoughtful mentorship during the inception and implementation of this tool, our community partners for their help in testing the tool and ensuring that health equity was built into the initial design of the tool, and our county manager and other county officials who championed this tool to the finish line.

Footnotes

Declaration of Conflicting Interests: The authors declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Funding: The authors disclosed receipt of the following financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article: This COVID-19 Working Group effort was supported by the National Science Foundation (NSF)–funded Social Science Extreme Events Research (SSEER) network and the CONVERGE facility at the Natural Hazards Center at the University of Colorado Boulder (NSF award 1841338). Any opinions, findings, and conclusions or recommendations expressed in this article are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the views of the NSF, SSEER, or CONVERGE.

ORCID iD

Jennifer D. Runkle, PhD, MSPH https://orcid.org/0000-0003-4611-1745

References

- 1. Yang J., Zheng Y., Gou X. et al. Prevalence of comorbidities and its effects in patients infected with SARS-CoV-2: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Int J Infect Dis. 2020;94:91-95. 10.1016/j.ijid.2020.03.017 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention . United States COVID-19 cases and deaths by state, reported to the CDC since January 21, 2020. Accessed December 23, 2020. https://covid.cdc.gov/covid-data-tracker/?deliveryName=USCDC_1377-DM37889#cases_casesper100klast7days

- 3. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention . COVID-19 (coronavirus disease): symptoms of coronavirus. Accessed December 23, 2020. https://www.cdc.gov/coronavirus/2019-ncov/symptoms-testing/symptoms.html

- 4. Chow N, Fleming-Dutra K, Gierke R, CDC COVID-19 Response Team . Preliminary estimates of the prevalence of selected underlying health conditions among patients with coronavirus disease 2019—United States, February 12–March 28, 2020. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2020;69(13):382-386. 10.15585/mmwr.mm6913e2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Galea S., Abdalla SM. COVID-19 pandemic, unemployment, and civil unrest: underlying deep racial and socioeconomic divides. JAMA. 2020;324(3):227-228. 10.1001/jama.2020.11132 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Gold JAW., Wong KK., Szablewski CM. et al. Characteristics and clinical outcomes of adult patients hospitalized with COVID-19—Georgia, March 2020. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2020;69(18):545-550. 10.15585/mmwr.mm6918e1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Price-Haywood EG., Burton J., Fort D., Seoane L. Hospitalization and mortality among Black patients and White patients with COVID-19. N Engl J Med. 2020;382(26):2534-2543. 10.1056/NEJMsa2011686 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. van Dorn A., Cooney RE., Sabin ML. COVID-19 exacerbating inequalities in the US. Lancet. 2020;395(10232):1243-1244. 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30893-X [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Cafer A., Rosenthal M. COVID-19 in the rural South: a perfect storm of disease, health access, and co-morbidity. APCRL Policy Briefs. 2020. Accessed December 23, 2020. https://egrove.olemiss.edu/apcrl_policybriefs/2

- 10. Amit M., Kimhi H., Bader T., Chen J., Glassberg E., Benov A. Mass-surveillance technologies to fight coronavirus spread: the case of Israel. Nat Med. 2020;26(8):1167-1169. 10.1038/s41591-020-0927-z [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Koh D. Singapore to launch TraceTogether token device for COVID-19 contact tracing. Mobile Health News. June 10, 2020. Accessed June 11, 2020. https://www.mobihealthnews.com/news/asia-pacific/singapore-launch-tracetogether-token-device-covid-19-contact-tracing

- 12. Ghaffary S. What the US can learn from other countries using phones to track COVID-19. Vox. April 22 2020. Accessed June 1, 2020. https://www.vox.com/recode/2020/4/18/21224178/covid-19-tech-tracking-phones-china-singapore-taiwan-korea-google-apple-contact-tracing-digital

- 13. Australian Government Department of Health . COVIDSafe app. Accessed December 23, 2020. https://www.health.gov.au/resources/apps-and-tools/covidsafe-app

- 14. Gray DM., Joseph JJ., Olayiwola JN. Strategies for digital care of vulnerable patients in a COVID-19 world—keeping in touch. JAMA Health Forum. 2020;1(6):e200734. 10.1001/jamahealthforum.2020.0734 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Wójcik OP., Brownstein JS., Chunara R., Johansson MA. Public health for the people: participatory infectious disease surveillance in the digital age. Emerg Themes Epidemiol. 2014;11:7. 10.1186/1742-7622-11-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Smolinski MS., Crawley AW., Olsen JM., Jayaraman T., Libel M. Participatory disease surveillance: engaging communities directly in reporting, monitoring, and responding to health threats. JMIR Public Health Surveill. 2017;3(4):e62. 10.2196/publichealth.7540 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Friesema IHM., Koppeschaar CE., Donker GA. et al. Internet-based monitoring of influenza-like illness in the general population: experience of five influenza seasons in the Netherlands. Vaccine. 2009;27(45):6353-6357. 10.1016/j.vaccine.2009.05.042 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Smolinski MS., Crawley AW., Olsen JM., Jayaraman T., Libel M. Participatory disease surveillance: engaging communities directly in reporting, monitoring, and responding to health threats. JMIR Public Health Surveill. 2017;3(4):e62. 10.2196/publichealth.7540 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Cantarelli P., Debin M., Turbelin C. et al. The representativeness of a European multi-center network for influenza-like-illness participatory surveillance. BMC Public Health. 2014;14(1):984. 10.1186/1471-2458-14-984 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Outbreaks Near Me . April 2020. Accessed October 23, 2020. https://covidnearyou.org/us/en-US/

- 21. Luo H., Lie Y., Prinzen FW. Surveillance of COVID-19 in the general population using an online questionnaire: report from 18,161 respondents in China. JMIR Public Health Surveill. 2020;6(2):e18576. 10.2196/18576 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Menni C., Valdes AM., Freidin MB. et al. Real-time tracking of self-reported symptoms to predict potential COVID-19. Nat Med. 2020;26(7):1037-1040. 10.1038/s41591-020-0916-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Mehl A., Bergey F., Cawley C., Gilsdorf A. Syndromic surveillance insights from a symptom assessment app before and during COVID-19 measures in Germany and the United Kingdom: results from repeated cross-sectional analyses. JMIR Mhealth Uhealth. 2020;8(10):e21364. 10.2196/21364 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Yamamoto K., Takahashi T., Urasaki M. et al. Health observation app for COVID-19 symptom tracking integrated with personal health records: proof of concept and practical use study. JMIR Mhealth Uhealth. 2020;8(7):e19902. 10.2196/19902 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Leal-Neto OB., Santos FAS., Lee JY., Albuquerque JO., Souza WV. Prioritizing COVID-19 tests based on participatory surveillance and spatial scanning. Int J Med Inform. 2020;143:104263. 10.1016/j.ijmedinf.2020.104263 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Goggin G. COVID-19 apps in Singapore and Australia: reimagining healthy nations with digital technology. Media Int Aust. 2020;177(1):61-75. 10.1177/1329878X20949770 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Lu FS., Hou S., Baltrusaitis K. et al. Accurate influenza monitoring and forecasting using novel internet data streams: a case study in the Boston metropolis. JMIR Public Health Surveill. 2018;4(1):e4. 10.2196/publichealth.8950 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Parrella A., Dalton CB., Pearce R., Litt JCB., Stocks N. ASPREN surveillance system for influenza-like illness: a comparison with FluTracking and the National Notifiable Diseases Surveillance System. Aust Fam Physician. 2009;38(11):932-936. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Paolotti D., Gioannini C., Colizza V., Vespignani A. Internet-based monitoring system for influenza-like illness: H1N1 surveillance in Italy. Presented at the 3rd International ICST Conference on Electronic Healthcare for the 21st century; December 13-15, 2010; Casablanca, Morocco.

- 30. World Health Organization . The World Health Report 2007—A Safer Future: Global Public Health Security in the 21st Century. World Health Organization; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 31. US Census . QuickFacts: Buncombe County, North Carolina. Population estimates July 1, 2019. Accessed October 23, 2020. https://www.census.gov/quickfacts/buncombecountynorthcarolina

- 32. Almagro M., Orane-Hutchinson A. The determinants of the differential exposure to COVID-19 in New York City and their evolution over time. June 22, 2020. Accessed December 23, 2020. 10.2139/ssrn.3573619 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 33. Eurostat . Information society statistics. Accessed December 23, 2020. https://ec.europa.eu/eurostat/statistics-explained/index.php/Archive:Information_society_statistics

- 34. Baltrusaitis K., Santillana M., Crawley AW., Chunara R., Smolinski M., Brownstein JS. Determinants of participants’ follow-up and characterization of representativeness in Flu Near You, a participatory disease surveillance system. JMIR Public Health Surveill. 2017;3(2):e18. 10.2196/publichealth.7304 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Mackenzie CS., Gekoski WL., Knox VJ. Age, gender, and the underutilization of mental health services: the influence of help-seeking attitudes. Aging Ment Health. 2006;10(6):574-582. 10.1080/13607860600641200 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Matheson FI., Smith KLW., Fazli GS., Moineddin R., Dunn JR., Glazier RH. Physical health and gender as risk factors for usage of services for mental illness. J Epidemiol Community Health. 2014;68(10):971-978. 10.1136/jech-2014-203844 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Verhaak PFM., Heijmans MJWM., Peters L., Rijken M. Chronic disease and mental disorder. Soc Sci Med. 2005;60(4):789-797. 10.1016/j.socscimed.2004.06.012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Nabalamba A., Millar WJ. Going to the doctor. Health Rep. 2007;18(1):23-35. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Thompson AE., Anisimowicz Y., Miedema B., Hogg W., Wodchis WP., Aubrey-Bassler K. The influence of gender and other patient characteristics on health care–seeking behaviour: a QUALICOPC study. BMC Fam Pract. 2016;17:38. 10.1186/s12875-016-0440-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Amir-Behghadami M., Gholizadeh M. Electronic screening through community engagement: a national strategic plan to find COVID-19 patients and reduce clinical intervention delays. Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol. 2020;41(12):1476-1478. 10.1017/ice.2020.188 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Garg S., Bhatnagar N., Gangadharan N. A case for participatory disease surveillance of the COVID-19 pandemic in India. JMIR Public Health Surveill. 2020;6(2):e18795. 10.2196/18795 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Thacker SB, Qualters JR, Lee LM, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention . Public health surveillance in the United States: evolution and challenges. MMWR Surveill Summ. 2012;61(3):3-9. https://www.cdc.gov/MMWR/preview/mmwrhtml/su6103a2.htm [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Perrin A. Digital gap between rural and nonrural America persists. Pew Research Center. May 31, 2019. Accessed June 19, 2020. https://www.pewresearch.org/fact-tank/2019/05/31/digital-gap-between-rural-and-nonrural-america-persists/

- 44. Pew Research Center . Internet/broadband fact sheet. June 12, 2019. Accessed June 21, 2020. https://www.pewresearch.org/internet/fact-sheet/internet-broadband/#smartphone-dependency-over-time

- 45. Redondo-Sendino A., Guallar-Castillón P., Banegas JR., Rodríguez-Artalejo F. Gender differences in the utilization of health-care services among the older adult population of Spain. BMC Public Health. 2006;6:155. 10.1186/1471-2458-6-155 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Uiters E., Devillé W., Foets M., Spreeuwenberg P., Groenewegen PP. Differences between immigrant and non-immigrant groups in the use of primary medical care; a systematic review. BMC Health Serv Res. 2009;9:76. 10.1186/1472-6963-9-76 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Krosnick J., Chang L. The American Association for Public Opinion Research (AAPOR) 56th Annual Conference. A comparison of the random digit dialing telephone survey methodology with internet survey methodology as implemented by Knowledge Networks and Harris Interactive. Presented at the American Association for Public Opinion Research 56th Annual Conference; May 17-20, 2001; Montreal, Quebec.

- 48. Breton C., Cutler F., Lachance S., Mierke-Zatwarnicki A. Telephone versus online survey modes for election studies: comparing Canadian public opinion and vote choice in the 2015 federal election. Can J Polit Sci. 2017;50(4):1005-1036. 10.1017/S0008423917000610 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Duffy B., Smith K., Terhanian G., Bremer J. Comparing data from online and face-to-face surveys. Int J Market Res. 2005;47(6):615-639. 10.1177/147078530504700602 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Scarpino SV., Scott JG., Eggo RM., Clements B., Dimitrov NB., Meyers LA. Socioeconomic bias in influenza surveillance. PLoS Comput Biol. 2020;16(7):e1007941. 10.1371/journal.pcbi.1007941 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Zhao YQ., Ma WJ., WJ Ma. A review on the advancement of internet-based public health surveillance program [in Chinese]. Zhonghua Liu Xing Bing Xue Za Zhi. 2017;38(2):272-276. 10.3760/cma.j.issn.0254-6450.2017.02.027 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Rohart F., Milinovich GJ., Avril SMR., Lê Cao K-A., Tong S., Hu W. Disease surveillance based on internet-based linear models: an Australian case study of previously unmodeled infection diseases. Sci Rep. 2016;6:38522. 10.1038/srep38522 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Perrotta D., Bella A., Rizzo C., Paolotti D. Participatory online surveillance as a supplementary tool to sentinel doctors for influenza-like illness surveillance in Italy. PLoS One. 2017;12(1):e0169801. 10.1371/journal.pone.0169801 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]