Abstract

Objectives

People detained in correctional facilities are at high risk for infection with severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2, the virus that causes coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19). We described the epidemiology of the COVID-19 outbreak in a large urban jail system, including signs and symptoms at time of testing and risk factors for hospitalization.

Methods

This retrospective observational cohort study included all patients aged ≥18 years who were tested for COVID-19 during March 11–April 28, 2020, while in custody in the New York City jail system (N = 978). We described demographic characteristics and signs and symptoms at the time of testing and performed Cox regression analysis to identify factors associated with hospitalization among those with a positive test result.

Results

Of 978 people tested for COVID-19, 568 received a positive test result. Among symptomatic patients, the most common symptoms among those who received a positive test result were cough (n = 293 of 510, 57%) and objective fever (n = 288 of 510, 56%). Of 257 asymptomatic patients who were tested, 58 (23%) received a positive test result. Forty-five (8%) people who received a positive test result were hospitalized for COVID-19. Older age (aged ≥55 vs 18-34) (adjusted hazard ratio [aHR] = 13.41; 95% CI, 3.80-47.33) and diabetes mellitus (aHR = 1.99; 95% CI, 1.00-3.95) were significantly associated with hospitalization.

Conclusions

A substantial proportion of people tested in New York City jails received a positive test result for COVID-19, including a large proportion of people tested while asymptomatic. During periods of ongoing transmission, asymptomatic screening should complement symptom-driven COVID-19 testing in correctional facilities. Older patients and people with diabetes mellitus should be closely monitored after COVID-19 diagnosis because of their increased risk for hospitalization.

Keywords: COVID-19, SARS-CoV-2, jail, incarcerated, correctional facilities/prisons

Correctional facilities are at risk for rapid spread of severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2), the virus that causes coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19). Transmission of SARS-CoV-2 in the New York City jail system began in early March 2020, during a time of high community incidence and when characteristics of COVID-19—including prolonged incubation periods, 1 presymptomatic transmission, 2 and asymptomatic infections 3 —were poorly understood. COVID-19 infection has been identified in most surveyed US correctional facilities. 4

People detained in jail have a disproportionate risk of COVID-19 5 and may augment infection rates in the communities to which they return after release from jail. 6 Jail systems in the United States, which are primarily remand facilities, have rapid turnover of detained people. 7 In 2019, New York City jails had >34 000 admissions, with a median (interquartile range [IQR]) length of stay of 20 (4-92) days. Incarcerated populations are aging 8 and have a high prevalence of chronic medical conditions, 9 mental illness, and substance use disorder, 10 which may increase their risk for poor outcomes from COVID-19.

NYC Health + Hospitals/Correctional Health Services (CHS) provides health care and discharge planning services to people detained in New York City jails. The jail system had an average daily population of approximately 5400 in February 2020 (internal report, New York City Department of Correction, June 2020). In 1992, New York City built a 98-bed communicable disease unit in the jail system with negative-pressure single cells as part of coordinated tuberculosis control efforts. 11 This unit could house patients requiring isolation for COVID-19, but its capacity was rapidly exceeded within the first 2 weeks of the presentation of the virus. CHS detected the first COVID-19 case among patients in jail on March 14, 2020. In cooperation with the New York City Department of Correction, the CHS response adhered to evolving public health guidance for COVID-19 management in correctional facilities. 12

Telephone lines in all housing areas allowed for patients to report symptoms directly to medical staff members (passive screening), and CHS teams performed in-person surveys of patients on housing units to screen for symptoms and fever (active screening). Symptoms that prompted testing evolved on the basis of updated public health agency case definitions. Symptoms initially included fever, cough, shortness of breath, and sore throat but expanded as understanding of COVID-19 improved. Symptomatic people were tested and isolated pending results. Patients with confirmed COVID-19 were separately housed together as a group (isolated as a cohort), and patients aged ≥55 and patients with comorbidities were monitored closely. People exposed to COVID-19 were quarantined and observed for development of symptoms, which, in turn, prompted isolation and testing. Quarantine of asymptomatic exposed people took place in their housing units. The entire unit was under quarantine together and monitored closely for 14 days past known exposure. All patients were provided with personal protective equipment and handwashing facilities and advised to maintain social distancing. Outdoor activity was allowed in small groups with appropriate social distancing. CHS staff members provided active screening for symptoms among quarantined groups. In addition, opt-out mass testing of asymptomatic people was performed twice for patients housed in jail infirmaries during this period, who were housed together based on comorbidities that made them vulnerable to severe COVID-19 should they contract SARS-CoV-2.

This study describes the COVID-19 epidemic in the New York City jail system from mid-March through April 2020, including demographic characteristics and signs and symptoms of people tested for COVID-19 while in jail custody and risk factors associated with COVID-19 hospitalization. Based on early reports of frequency of signs and symptoms associated with COVID-19, 13 we hypothesized that signs and symptoms would be neither sensitive nor specific for SARS-CoV-2 infection and that a substantial proportion of patients could be diagnosed with COVID-19 while asymptomatic. 3 In addition, based on national surveillance data, 14 we hypothesized that older people and people with underlying health conditions would have an increased likelihood of hospitalization. Our findings about the prevalence of COVID-19 in the New York City jail system may inform the health care response to COVID-19 in other jail systems.

Methods

Sample

We performed a retrospective observational cohort study of patients aged ≥18 (as of March 11, 2020) in custody in a New York City jail facility or hospital units housing patients from the jail system and tested for COVID-19 during March 11–April 28, 2020. Driven by concern for asymptomatic infection, 2 rounds of asymptomatic testing were performed as then-available testing capacity allowed, focusing on patients in the jail infirmary during the weeks of March 18 and April 6, respectively. The latter effort focused on patients with higher-level nursing needs. Patients with a positive reverse-transcription polymerase chain reaction (RT-PCR) qualitative test result by nasopharyngeal collection for SARS-CoV-2 were deemed to have COVID-19.

Outcomes of Interest

We defined our main outcome of interest, COVID-19 hospitalization, as a hospital admission for COVID-19–like illness with a recent or subsequent positive COVID-19 test result. We included only outcomes that occurred during incarceration. We considered all patients who were released from jail within 14 days of their test order date and not hospitalized before release as not hospitalized. We captured data on outcomes through May 13, 2020. We collected structured data on COVID-19–like signs and symptoms on presentation for testing from templated encounters guiding clinicians to ask about the most common COVID-19–like symptoms, including objective fever (defined as temperature ≥100 °F), cough, shortness of breath, sore throat, nausea, vomiting, diarrhea, fatigue, and malaise. Review of free-text notes from these encounters captured additional symptoms of myalgias, headache, chills, rhinorrhea, anosmia, ageusia, chest pain, and abdominal pain. Asymptomatic testing was performed during the weeks of March 18 and April 6 in the jail infirmaries. For patients who received a positive test result while asymptomatic, we reviewed the medical record for development of COVID-19–like symptoms occurring within 14 days of a positive test result.

Data Sources and Definitions

We extracted demographic, clinical, laboratory, and hospitalization data from electronic medical records. To facilitate comparison with community epidemiology, we used age categories in our analysis roughly based on categories used in an early report on COVID-19 hospitalization. 15 We classified homelessness status based on residence reported at admission to jail or by self-report at ≥1 CHS clinical encounter. CHS designates mental illness diagnosis based on identified psychiatric diagnoses and/or identified need for services or treatment. We determined serious mental illness status based on Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fifth Edition 16 diagnoses in the categories of schizophrenia spectrum and other psychotic disorders, bipolar and related disorders, depressive disorders, and posttraumatic stress disorder. We classified comorbidities based on International Classification of Diseases, Tenth Revision, Clinical Modification 17 and International Classification of Diseases, Ninth Revision, Clinical Modification 18 codes. We defined exposure to the jail infirmary based on being housed in the infirmary at any time from the date of COVID-19 testing to 14 days before testing.

Statistical Analysis

We described demographic and incarceration characteristics, selected comorbid conditions, signs and symptoms at time of COVID-19 testing, and COVID-19 test outcomes using counts, percentages, and summary statistics (eg, median, IQR). We assessed for bias in our testing cohorts by comparing age and sex of the cohort with the overall jail population at the time (unpublished data, CHS, March–May 2020) using Pearson χ2 and Mann-Whitney U tests. We used Cox regression to evaluate patient-level predictors of COVID-19–related hospitalization. We included variables associated with the outcome in univariate analysis (P < .10) in the final multivariable model, which we assessed using goodness-of-fit criteria. We calculated crude hazard ratios (HRs) and adjusted hazard ratios (aHRs) and 95% CIs. The proportional hazards assumption for the model was tested and met. We calculated the person-time (in days) from test date to hospitalization date with censoring for custodial release or end of follow-up. We considered a 2-sided P < .05 to be significant in multivariable analysis. We performed a sensitivity regression analysis by excluding the cohort of patients diagnosed with COVID-19 while asymptomatic. We performed statistical analyses using SAS Enterprise Guide version 7.15 (SAS Institute, Inc).

The study protocol was reviewed and approved by the Biomedical Research Alliance of New York Institutional Review Board.

Results

Of 6311 people detained in jail during March 11–April 28, 2020, we collected nasopharyngeal swabs for 978 (15%), of whom 568 (58%) received a positive test result (Table 1). Of 257 people who were asymptomatic at the time of testing, 58 (23%) received a positive test result. The turnaround time for test results was a median (IQR) of 2 (1-3) days. The median age (IQR) was 36 (28-48) years in the symptomatic testing cohort and 46 (32-58) years in the asymptomatic testing cohort. By comparison, the overall jail population at this time had a median (IQR) age of 33 (27-43) years and 94% were male. The testing cohort was significantly older and had a lower proportion of male patients than the overall jail population (P < .001) (data not shown). Of 510 symptomatic people who were diagnosed with COVID-19, the most frequently reported symptoms were cough (n = 293, 57%) and objective fever (n = 288, 56%).

Table 1.

Demographic characteristics and symptoms of the COVID-19 testing cohort, New York City jail system, March–April 2020

| Demographic characteristics | Symptomatic | Asymptomatic a | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Positive, b no. (%) (n = 510) | Negative, c no. (%) (n = 211) | Total, no. (%) (n = 721) | Positive, b no. (%) (n = 58) | Negative, c no. (%) (n = 199) | Total, no. (%) (n = 257) | |

| Age, y d | ||||||

| 18-34 | 221 (43) | 112 (53) | 333 (46) | 18 (31) | 58 (29) | 76 (30) |

| 35-44 | 114 (22) | 58 (27) | 172 (24) | 12 (21) | 30 (15) | 42 (16) |

| 45-54 | 91 (18) | 27 (13) | 118 (16) | 10 (17) | 38 (19) | 48 (19) |

| ≥55 | 84 (16) | 14 (7) | 98 (14) | 18 (31) | 73 (37) | 91 (35) |

| Median age (IQR), y | 37 (28-51) | 33 (26-41) | 36 (28-48) | 43 (30-57) | 48 (32-59) | 46 (32-58) |

| Sex | ||||||

| Male | 463 (91) | 195 (92) | 658 (91) | 49 (84) | 173 (87) | 222 (86) |

| Race/ethnicity e | ||||||

| Hispanic | 199 (39) | 70 (33) | 269 (37) | 17 (29) | 62 (31) | 79 (31) |

| Non-Hispanic Black | 237 (46) | 114 (54) | 351 (49) | 26 (45) | 116 (58) | 142 (55) |

| Non-Hispanic White | 40 (8) | 12 (6) | 52 (7) | 10 (17) | 16 (8) | 26 (10) |

| Non-Hispanic Asian, Pacific Islander, other, or unknown | 34 (7) | 15 (7) | 49 (7) | 5 (9) | 5 (3) | 10 (4) |

| Length of stay before testing, median (IQR), d | 129 (46-312) | 91 (28-238) | 117 (41-294) | 160.5 (55-323) | 96 (38-231) | 108 (41-243) |

| Homeless f | 163 (32) | 80 (38) | 243 (34) | 24 (41) | 87 (44) | 111 (43) |

| Diagnoses | ||||||

| Mental illness g | 306 (60) | 134 (64) | 440 (61) | 35 (60) | 123 (62) | 158 (61) |

| Serious mental illness h | 96 (19) | 47 (22) | 143 (20) | 16 (28) | 28 (14) | 44 (17) |

| Opioid use disorder i | 72 (14) | 32 (15) | 104 (14) | 9 (16) | 21 (11) | 30 (12) |

| Signs and symptoms at time of testing j , k | ||||||

| Cough | 293 (57) | 137 (65) | 430 (60) | |||

| Objective fever l | 288 (56) | 68 (32) | 356 (49) | |||

| Sore throat | 139 (27) | 71 (34) | 210 (29) | |||

| Shortness of breath | 108 (21) | 71 (34) | 179 (25) | |||

| Myalgias | 87 (17) | 36 (17) | 123 (17) | |||

| Malaise | 74 (15) | 28 (13) | 102 (14) | |||

| Headache | 82 (16) | 17 (8) | 99 (14) | |||

| Fatigue | 65 (13) | 19 (9) | 84 (12) | |||

| Chills | 59 (12) | 17 (8) | 76 (11) | |||

Abbreviations: COVID-19, coronavirus disease 2019; IQR, interquartile range.

aAsymptomatic testing was performed during the weeks of March 18, 2020, and April 6, 2020, in the jail infirmary.

bFor people with multiple positive results, data from the first positive testing event were used. Forty-seven patients had a positive test result for COVID-19 at a hospital while in jail custody.

cFor people with multiple negative test results, data from the first symptom-driven testing event, if one took place, were included (some may have only had asymptomatic testing). Four patients had a negative test result for COVID-19 at a hospital while in jail custody.

dAge as of March 11, 2020.

eEight patients were missing data on race/ethnicity. They were categorized as non-Hispanic Asian, Pacific Islander, other, or unknown.

fHomelessness was based on residence reported at admission to jail or by self-report of homelessness or shelter use at ≥1 Correctional Health Services clinical encounter.

gThe New York City jail designation of mental illness is based on identified psychiatric diagnoses and/or identified need for services or treatment.

hDeterminations of severe mental illness are made by mental health clinicians based on Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, 5th edition diagnoses in the categories of schizophrenia spectrum and other psychotic disorders, bipolar and related disorders, depressive disorders, and posttraumatic stress disorder. 17

i International Classification of Diseases, 10th Revision, Clinical Modification diagnoses of opioid-related disorders (F11.x) or International Classification of Diseases, 9th Revision, Clinical Modification diagnoses of opioid non-dependent abuse and dependence (304.0x, 305.5x). 18,19

jOther symptoms including rhinorrhea, nausea/vomiting, diarrhea, anosmia, chest pain, and abdominal pain were reported in <10% of patients at the time of testing.

kThree patients who had a positive test result for COVID-19 were missing data on symptoms in the medical record and were not included in the total symptoms count.

lObjective fever was defined as temperature ≥100 °F.

COVID-19 Hospitalizations

Of 568 patients who received a positive test result for COVID-19, 45 (8%) were hospitalized (Table 2), 3 (7%) of whom were asymptomatic at diagnosis. Among all patients who tested positive for COVID-19, the median (IQR) follow-up time per person was 34 (13-43) days and the total follow-up time was 16 590 person-days. One hundred four patients who had a positive test result for COVID-19 were not hospitalized and were released from jail within 14 days of their test. The median (IQR) time from diagnosis to hospitalization was 1 (1-5) day. From date of hospitalization, 8 (18%) patients were admitted to the intensive care unit at a median (IQR) time of 3 (1-4) days, and 3 (7%) patients died while in custody at a median (IQR) time of 10 (8-17) days. No deaths occurred in the jail facilities.

Table 2.

Characteristics of COVID-19 patients associated with hospitalization, New York City jail system, March–April 2020

| Characteristics | Hospitalized, no. (%) (n = 45) | Not hospitalized, a no. (%) (n = 523) | Univariate Cox HR (95% CI) | P value b | Multivariable adjusted HR c (95% CI) |

P value b |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age, y | ||||||

| 18-34 | 3 (7) | 236 (45) | 1.00 [Reference] | 1.00 [Reference] | ||

| 35-44 | 7 (16) | 119 (23) | 4.70 (1.21-18.16) | .03 | 4.06 (1.04-15.93) | .045 |

| 45-54 | 9 (20) | 92 (18) | 7.51 (2.03-27.76) | .003 | 5.07 (1.33-19.25) | .02 |

| ≥55 | 26 (58) | 76 (15) | 23.53 (7.71-77.84) | <.001 | 13.41 (3.80-47.33) | <.001 |

| Sex | ||||||

| Male | 42 (93) | 470 (90) | 1.49 (0.46-4.81) | .50 | ||

| Female | 3 (7) | 53 (10) | 1.00 [Reference] | |||

| Race/ethnicity | ||||||

| Hispanic | 20 (44) | 196 (37) | 1.37 (0.72-2.58) | .34 | ||

| Non-Hispanic Black | 18 (40) | 245 (47) | 1.00 [Reference] | |||

| Non-Hispanic White, Asian, Pacific Islander, other, or unknown | 7 (16) | 82 (16) | 1.14 (0.48-2.72) | .77 | ||

| Body mass index, kg/m2 | ||||||

| <25 | 8 (18) | 172 (33) | 1.00 [Reference] | 1.00 [Reference] | ||

| ≥25 | 37 (82) | 351 (67) | 2.12 (0.99-4.55) | .05 | 1.48 (0.67-3.26) | .34 |

| Exposure to the jail infirmary | ||||||

| Yes | 15 (33) | 64 (12) | 3.32 (1.78-6.17) | <.001 | 0.99 (0.90-1.07) | .72 |

| No | 30 (67) | 459 (88) | 1.00 [Reference] | 1.00 [Reference] | ||

| Smoking status | ||||||

| Current smoker | 15 (33) | 258 (49) | 0.55 (0.30-1.02) | .06 | 1.03 (0.95-1.12) | .46 |

| Not a current smoker | 30 (67) | 265 (51) | 1.00 [Reference] | 1.00 [Reference] | ||

| Diagnoses d | ||||||

| Serious mental illness e | 10 (22) | 102 (20) | 1.16 (0.58-2.35) | .67 | ||

| Alcohol use disorder f | 6 (13) | 91 (17) | 0.73 (0.31-1.72) | .47 | ||

| Opioid use disorder g | 6 (13) | 75 (14) | 0.92 (0.39-2.17) | .84 | ||

| HIV h | 2 (4) | 15 (3) | 1.49 (0.36-6.17) | .58 | ||

| Hepatitis C h | 0 | 17 (3) | 0 | .98 | ||

| Diabetes h | 15 (33) | 42 (8) | 4.92 (2.64-9.14) | <.001 | 1.99 (1.00-3.95) | .048 |

| Hypertension h | 21 (47) | 75 (14) | 4.47 (2.49-8.03) | <.001 | 0.93 (0.85-1.00) | .07 |

| Chronic kidney disease g | 1 (2) | 3 (1) | NA | |||

| Asthma g | 2 (4) | 28 (5) | 0.78 (0.19-3.21) | .73 | ||

| Pulmonary disease h | 4 (9) | 9 (2) | 4.43 (1.59-12.38) | .02 | 0.97 (0.85-1.12) | .72 |

| Cardiovascular disease h | 12 (27) | 35 (7) | 4.20 (2.17-8.14) | <.001 | 0.99 (0.89-1.10) | .84 |

| Cancer (active or recent) h | 0 | 8 (2) | NA | |||

Abbreviations: COVID-19, coronavirus disease 2019; HR, hazard ratio; ICD-9-CM, International Classification of Diseases, 9th Revision, Clinical Modification; ICD-10-CM, International Classification of Diseases, 10th Revision, Clinical Modification; NA, not applicable.

aNot hospitalized includes 104 patients released within 14 days of test order date.

bCox regression analysis, with P < .05 considered significant.

cThe final multivariable model included age category, body mass index category, exposure to the jail infirmary, current smoking status, diabetes, hypertension, pulmonary disease, and cardiovascular disease.

dThe reference categories for all diagnosis variables are not having the diagnosis.

eSerious mental illness determinations are made by mental health clinicians based on Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, 5th edition diagnoses in the categories of schizophrenia spectrum and other psychotic disorders, bipolar and related disorders, depressive disorders, and posttraumatic stress disorder. 16

fICD-10-CM diagnoses of alcohol-related disorders (F10.x) or ICD-9-CM diagnoses of alcohol non-dependent abuse and dependence (303.x, 305.0x). 17,18

gICD-10-CM diagnoses of opioid-related disorders (F11.x) or ICD-9-CM diagnoses of opioid non-dependent abuse and dependence (304.0x, 305.5x). 17,18

hICD-10-CM diagnoses of HIV (B20, Z21); hepatitis C (B18.2, B19.2x, Z22.52 + detectable hepatitis C viral load within last 2 years); diabetes mellitus (E08.x-E13.x); hypertension (I10.x, I11.0, I11.9, I12.0, I12.x, I13.0, I13.1, I13.2, I15.0, 15.2, I15.8, I15.9); chronic kidney disease (N18.1-18.4); asthma (J45.x + required management with inhaled corticosteroids); pulmonary disease, not including asthma (J41.x-46.x, J80.x-94.x, J96.x); cardiovascular disease, not including hypertension (I10.x-I79.x); and cancer (C00.x-D48.x excluding D3A and other codes for basal cell carcinoma, benign tumors). 17

In univariate analysis, older age (age ≥35 vs 18-34), body mass index, current smoking, diabetes mellitus, hypertension, cardiovascular disease, exposure to the jail infirmary, and pulmonary disease (excluding asthma) were significantly associated with increased risk of hospitalization (at P < .10) (Table 2). However, in multivariable analysis, only older age (age ≥35 vs 18-34) (≥55: aHR = 13.41; 95% CI, 3.80-47.33; 45-54: aHR = 5.07; 95% CI, 1.33-19.25; 35-44: aHR = 4.06; 95% CI, 1.04-15.93) and diabetes mellitus (aHR = 1.99; 95% CI, 1.00-3.95) remained significant. In our sensitivity analysis that excluded patients who were diagnosed while asymptomatic, only older age (age ≥55 vs 18-34) (aHR = 12.92; 95% CI, 3.62-46.15) was significantly associated with hospitalization (P < .001).

Outcomes of Asymptomatic Testing

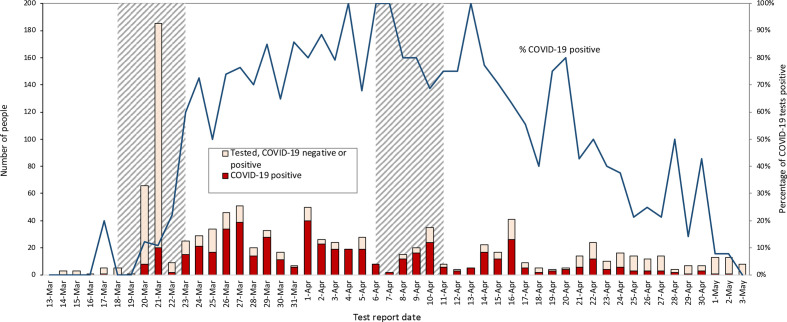

Testing of 234 asymptomatic people during the week of March 18 identified 13 (6%) patients with COVID-19, of whom 1 (8%) remained asymptomatic for at least 14 days after the first positive test result (Table 3, Figure 1). A second round of testing of 35 asymptomatic patients with higher-level nursing needs during the week of April 6 identified 23 (66%) patients with COVID-19, of whom 14 (61%) remained asymptomatic. Twenty-three people who were not tested (8% of those eligible) either declined testing or were transferred from the facility before testing could be offered.

Table 3.

Outcomes of asymptomatic COVID-19 testing for the weeks of March 18 and April 6, 2020, at New York City jails

| Characteristic | Testing week | |

|---|---|---|

| March 18, 2020 | April 6, 2020 a | |

| Eligible for testing, no. | 247 | 45 |

| Tested, no. (%) | 234 (95) | 35 (78) |

| Tested positive, no. (column %) | 13 (6) | 23 (66) |

| Developed subsequent COVID-19–like symptoms b among those who tested positive, no. (column %) c | 7 (54) | 7 (30) |

| Remained asymptomatic d among those tested positive, no. (column %) c | 1 (8) | 14 (61) |

| Released from custody after testing positive, e no. (column %) c | 5 (39) | 2 (9) |

Abbreviation: COVID-19, coronavirus disease 2019.

aThe housing areas tested on the second round of testing (starting April 6, 2020) were areas with higher-level nursing needs, a subset of the housing areas from the first round of testing (starting March 18, 2020). Those who had received a negative test result in the first round of testing were retested in the second round.

bCOVID-19–like symptoms were defined as any of objective fever, cough, shortness of breath, sore throat, nausea/vomiting, diarrhea, and/or anosmia that occur within 14 days of the positive test result.

cDenominator is total positive COVID-19 tests.

dFor at least 14 days after positive COVID-19 test.

eWithin 14 days after positive COVID-19 test.

Figure 1.

People in jail custody who were tested for COVID-19 and received a positive test result, by date of jail facility test report, New York City jails, March 13–May 3, 2020. Excludes people who were tested at a hospital. Incarcerated people who received a negative test result and are reported as such on one date and who subsequently received a positive test result at a later date are reported again as positive on that date. The shaded date ranges were when asymptomatic COVID-19 screening sweeps occurred in jail infirmary housing areas. Test dates refer to the date when the test result was reported from the laboratory. Abbreviation: COVID-19, coronavirus disease 2019.

Discussion

People who are incarcerated in the United States have had a higher rate of SARS-CoV-2 infection and COVID-19–related death than the general population. 5,19 The period of our epidemic mirrored the timing of the epidemic in the New York City community. 20 The testing cohort in our study included a high proportion of patients at elevated risk of contracting COVID-19. 21,22 Signs and symptoms at testing were neither sensitive nor specific for COVID-19, and many patients had a positive test result while asymptomatic.

Our data highlight some limitations of symptom-driven testing. Most patients in our cohort requiring hospitalization were diagnosed while symptomatic close to the day of hospitalization, demonstrating that symptom-based testing may miss early progression of disease (eg, silent hypoxia). Although patients access health care in our jail system at no personal cost, presentation for care may be delayed or avoided if patients in jail are hesitant to report symptoms because of apprehension of being triaged to medical isolation units. 23 Symptom-driven testing alone will also miss asymptomatic COVID-19, which could account for an estimated 40%-45% of infections. 24

The New York City jail infirmaries routinely house elderly patients and patients with substantial comorbidities to provide more intensive medical care relative to care provided to patients in the general jail housing areas. We suspended infirmary admissions well in advance of any identified transmission in the jails to protect these patients from COVID-19. We recognized the possibility of transmission of asymptomatic infection and focused our resources on performing asymptomatic surveillance testing on the medically vulnerable infirmary population as then-strained testing capacity allowed. A significant proportion of asymptomatic people who were tested received a positive test result for COVID-19, with a dramatic increase in test positivity, increasing from 6% to 66% of asymptomatic patients in the span of a few weeks. This finding suggests a high rate of asymptomatic infection and rapid transmission between the 2 rounds of testing despite efforts to insulate this patient cohort and closely survey for symptoms. Some patients may not have reported earlier mild symptoms, and some asymptomatic patients who received a positive test result may have been in the convalescent phase of infection with residual nonviable viral nucleic acid. Although it is unclear what proportion of all people with asymptomatic COVID-19 were infectious at the time of testing, 14 (39%) asymptomatic infirmary patients who tested positive were diagnosed during their presymptomatic phase and were likely contagious. 2 Regardless of symptom status, all people who tested positive were presumed to be infectious and isolated. These data highlight the importance of properly timed and targeted asymptomatic surveillance testing to complement symptom-driven testing, 25 such as universal jail admission testing and asymptomatic testing in facilities with a new case of COVID-19, both currently used by CHS. Given the rapidity of viral spread, targeted and frequent testing of hotspots guided by local epidemiology is likely to be more beneficial than simple mass testing.

Outcomes of large-scale asymptomatic testing events by RT-PCR assay from other correctional systems found that symptom-based testing alone would underestimate COVID-19 prevalence, 26 but the optimal timing of asymptomatic testing in correctional settings requires further study. One pitfall of large-scale asymptomatic testing by RT-PCR is the ability to detect noninfectious viral nucleic acid from convalescent infection, which can persist long after the onset of symptoms. 2 Unnecessary isolation of noninfectious patients and quarantining of contacts may be associated with risks, such as disrupting higher-intensity mental health services, which rely on a therapeutic milieu that cannot be re-created in isolation housing. Other harms may mirror those associated with solitary confinement, 27,28 as is reportedly used in lieu of medical isolation in some systems, although not in New York City.

In this cohort, risk factors associated with COVID-19 hospitalization were older age and diabetes mellitus, which were among the conditions 29 that triggered CHS to provide closer clinical monitoring. Our findings are consistent with national data on risk factors for COVID-19 hospitalization. 14 In our sensitivity analysis, which excluded patients diagnosed while asymptomatic, diabetes mellitus was not a significant risk factor. That diabetes mellitus was no longer a risk factor in this model may be because the cohort that was symptomatic at diagnosis was biased toward a higher proportion of severe COVID-19 disease regardless of diabetes mellitus status, whereas mass asymptomatic testing diagnosed more mild cases. In a cohort with more severe disease at diagnosis, the additional risk from diabetes mellitus may be difficult to detect with a small sample size. Although elevated body mass index was associated with COVID-19 hospitalization in a large British community-based observational cohort study (N = 334 329), 30 we did not observe this association in our cohort based on our multivariable model. That body mass index was not a significant risk factor for hospitalization in our cohort could be due to our small sample size with limited statistical power. In addition, impaired glucose metabolism, which was a significant risk factor in our cohort, may be part of the underlying mechanism in the association between body mass index and severe COVID-19 illness. 30 In the United States, the population aged ≥55 in correctional settings has grown substantially. 8 These demographic trends likely exacerbate the risk of COVID-19 morbidity and mortality in correctional settings. We support grouping older patients with comorbidities in the jail infirmary because facilities for the general jail population do not allow us to provide them the appropriate level of general medical care and monitoring of people in isolation with COVID-19. However, we recognize that this grouping may also risk SARS-CoV-2 transmission. This concern, along with our study findings, supports our efforts at advocating for reducing the population in jails and prisons, with a focus on elderly patients, incarcerated during the COVID-19 epidemic.

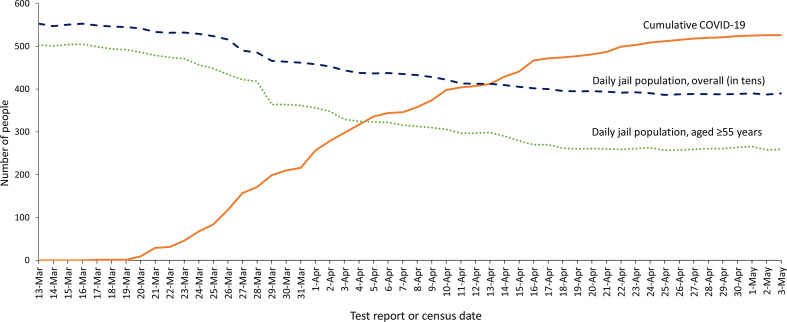

Since May 13, 2020, few new cases of COVID-19 have been identified in the New York City jail system, despite ongoing universal testing upon admission to the jail system and hospitals and before transfers to the jail infirmaries. Factors that may have contributed to the eventual decline in COVID-19 incidence in New York City jails include infection control interventions undertaken by CHS and the New York City Department of Correction, a concurrent decrease in New York City community transmission, 20 and some degree of population-level immunity in the jail system. New York City coordinated a large reduction of the jail population at risk for developing severe COVID-19 (Figure 2), which enabled improved social distancing among the remaining jail population and likely reduced the number of COVID-19 hospitalizations and deaths.

Figure 2.

Jail population, overall and aged ≥55 years, and cumulative number of people in jail custody who were tested and received a positive test result for COVID-19, by date of jail facility test report, New York City, March 13–May 3, 2020. Excludes people who were tested at a hospital. The cumulative count includes incarcerated people who received a positive test result for COVID-19 by date of report, regardless of custodial status. Test dates refer to the date when the test result was reported from the laboratory. Abbreviation: COVID-19, coronavirus disease 2019.

Limitations

These findings had several limitations. First, data on COVID-19–related hospitalizations, intensive care unit admissions, and mortality were censored for people released from jail before the study end date. However, the median (IQR) duration of follow-up per person with a positive test result for COVID-19 was 34 (13-43) days. Second, the reported distribution of symptoms may underestimate the true prevalence of anosmia and ageusia, which were not initially widely recognized as features of COVID-19 at the height of the outbreak in New York City jails. Third, these data likely underestimate COVID-19 risk associated with older age and diabetes mellitus because New York City made concerted efforts to release incarcerated people at risk for severe outcomes from COVID-19, 29 which led to a decline in the average daily jail census of approximately 1600 people. Fourth, our testing cohort likely underestimates the true incidence of COVID-19 infection, because many asymptomatic patients likely did not present for testing, and symptoms may have been underreported by others wanting to avoid medical isolation. 23

Fifth, although some data suggest more widespread transmission in open dormitory-based settings than in cell housing settings, 26 we could not determine the relative risk of transmission in various types of housing units because patients were frequently transferred between housing units before and during the early stages of the epidemic. As such, we could not confirm where transmission events occurred. Sixth, our study was subject to potential bias. The median age of our asymptomatic and symptomatic testing cohorts was higher than that of our overall jail population at the time. This difference was likely the result of mass asymptomatic testing among our elderly population in the jail infirmaries, and symptomatic COVID-19 being more likely to occur among older age cohorts than among younger age cohorts. 31 Although this testing strategy may have biased our cohort toward a higher frequency of comorbidities associated with older age, our data represent outcomes of people at highest risk for COVID-19 in our jail system. Finally, our results may not be generalizable to other correctional facilities because of different COVID-19 epidemiology and resources available (eg, testing capacity) at local correctional health services. However, these results may be applicable to facilities that have ongoing SARS-CoV-2 transmission.

Conclusions

This study highlights the importance of targeted asymptomatic testing for COVID-19 in correctional facilities tailored to local epidemiology to supplement symptom-based testing, particularly when transmission is ongoing. Isolation and quarantine protocols should include plans for close monitoring of older COVID-19 patients and those with comorbid conditions. Furthermore, RT-PCR testing provides data only for a moment in time, and testing of asymptomatic people may detect convalescent rather than active infection after a period of widespread transmission. Further study should help define optimal frequency and appropriate timing of testing implementation in the context of jail and community epidemiology.

Acknowledgments

CHS acknowledges the unwavering commitment of essential workers of the New York City jail system, including the dedicated staff members of CHS and the New York City Department of Correction, with special thanks to Commissioner Cynthia Brann, Chief of Department Hazel Jennings, and Chief of Staff Brenda Cooke.

Footnotes

Data Sharing Statement: CHS has made much of the source data from this study available through public reporting, accessible at: https://www1.nyc.gov/site/boc/covid-19-updates.page

Declaration of Conflicting Interests: The authors declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Funding: The authors received no financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

References

- 1. Lauer SA., Grantz KH., Bi Q. et al. The incubation period of coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) from publicly reported confirmed cases: estimation and application. Ann Intern Med. 2020;172(9):577-582. 10.7326/M20-0504 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. He X., Lau EHY., Wu P. et al. Temporal dynamics in viral shedding and transmissibility of COVID-19. Nat Med. 2020;26(5):672-675. 10.1038/s41591-020-0869-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Mizumoto K., Kagaya K., Zarebski A., Chowell G. Estimating the asymptomatic proportion of coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) cases on board the Diamond Princess cruise ship, Yokohama, Japan, 2020. Euro Surveill. 2020;25(10):2000180. 10.2807/1560-7917.ES.2020.25.10.2000180 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Wallace M., Hagan L., Curran KG. et al. COVID-19 in correctional and detention facilities—United States, February–April 2020. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2020;69(19):587-590. 10.15585/mmwr.mm6919e1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Jiménez MC., Cowger TL., Simon LE., Behn M., Cassarino N., Bassett MT. Epidemiology of COVID-19 among incarcerated individuals and staff in Massachusetts jails and prisons. JAMA Netw Open. 2020;3(8):e2018851. 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2020.18851 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Reinhart E., Chen DL. Incarceration and its disseminations: COVID-19 pandemic lessons from Chicago’s Cook County jail. Health Aff (Millwood). 2020;39(8):1412-1418. 10.1377/hlthaff.2020.00652 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Zeng Z. Jail Inmates in 2018. US Department of Justice, Bureau of Justice Statistics, Office of Justice Programs; March 31, 2020. Accessed September 1, 2020. https://www.bjs.gov/index.cfm?ty=pbdetail&iid=6826

- 8. Williams BA., Goodwin JS., Baillargeon J., Ahalt C., Walter LC. Addressing the aging crisis in U.S. criminal justice health care. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2012;60(6):1150-1156. 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2012.03962.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Wilper AP., Woolhandler S., Boyd JW. et al. The health and health care of US prisoners: results of a nationwide survey. Am J Public Health. 2009;99(4):666-672. 10.2105/AJPH.2008.144279 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Fazel S., Yoon IA., Hayes AJ. Substance use disorders in prisoners: an updated systematic review and meta-regression analysis in recently incarcerated men and women. Addiction. 2017;112(10):1725-1739. 10.1111/add.13877 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Frieden TR., Fujiwara PI., Washko RM., Hamburg MA. Tuberculosis in New York City—turning the tide. N Engl J Med. 1995;333(4):229-233. 10.1056/NEJM199507273330406 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention . Interim guidance on management of coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) in correctional and detention facilities. 2020. Accessed September 1, 2020. https://www.cdc.gov/coronavirus/2019-ncov/community/correction-detention/guidance-correctional-detention.html

- 13. Guan W-J., Ni Z-Y., Hu Y. et al. Clinical characteristics of coronavirus disease 2019 in China. N Engl J Med. 2020;382(18):1708-1720. 10.1056/NEJMoa2002032 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Stokes EK., Zambrano LD., Anderson KN. et al. Coronavirus disease 2019 case surveillance—United States, January 22–May 30, 2020. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2020;69(24):759-765. 10.15585/mmwr.mm6924e2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. CDC COVID-19 Response Team . Severe outcomes among patients with coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19)—United States, February 12–March 16, 2020. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2020;69(12):343-346. 10.15585/mmwr.mm6912e2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. American Psychiatric Association . Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders. 5th ed. American Psychiatric Association; 2020. 10.1176/appi.books.9780890425596 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 17. National Center for Health Statistics . International Classification of Diseases, 10th Revision, Clinical Modification (ICD-10-CM). 2020. Accessed September 2, 2020. https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/icd/icd10cm.htm [PubMed]

- 18. National Center for Health Statistics . International Classification of Diseases, 9th Revision, Clinical Modification (ICD-9-CM). 2015. Accessed September 2, 2020. https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/icd/icd9cm.htm

- 19. Saloner B., Parish K., Ward JA., DiLaura G., Dolovich S. COVID-19 cases and deaths in federal and state prisons. JAMA. 2020;324(6):602-603. 10.1001/jama.2020.12528 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. NYC Health . COVID-19: data. 2020. Accessed September 1, 2020. https://www1.nyc.gov/site/doh/covid/covid-19-data.page

- 21. Webb Hooper M., Nápoles AM., Pérez-Stable EJ. COVID-19 and racial/ethnic disparities. JAMA. 2020;323(24):2466-2467. 10.1001/jama.2020.8598 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Mosites E., Parker EM., Clarke KEN. et al. Assessment of SARS-CoV-2 infection prevalence in homeless shelters—four U.S. cities, March 27–April 15, 2020. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2020;69(17):521-522. 10.15585/mmwr.mm6917e1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Wurcel AG., Dauria E., Zaller N. et al. Spotlight on jails: COVID-19 mitigation policies needed now. Clin Infect Dis. 2020;71(15):891-892. 10.1093/cid/ciaa346 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Oran DP., Topol EJ. Prevalence of asymptomatic SARS-CoV-2 infection: a narrative review. Ann Intern Med. 2020;173(5):362-367. 10.7326/M20-3012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Njuguna H., Wallace M., Simonson S. et al. Serial laboratory testing for SARS-CoV-2 infection among incarcerated and detained persons in a correctional and detention facility—Louisiana, April–May 2020. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2020;69(26):836-840. 10.15585/mmwr.mm6926e2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Hagan LM., Williams SP., Spaulding AC. et al. Mass testing for SARS-CoV-2 in 16 prisons and jails—six jurisdictions, United States, April–May 2020. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2020;69(33):1139-1143. 10.15585/mmwr.mm6933a3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Reiter K., Ventura J., Lovell D. et al. Psychological distress in solitary confinement: symptoms, severity, and prevalence in the United States, 2017-2018. Am J Public Health. 2020;110(S1):S56-S62. 10.2105/AJPH.2019.305375 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Kaba F., Lewis A., Glowa-Kollisch S. et al. Solitary confinement and risk of self-harm among jail inmates. Am J Public Health. 2014;104(3):442-447. 10.2105/AJPH.2013.301742 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention . COVID-19: people at increased risk. Accessed September 1, 2020. https://www.cdc.gov/coronavirus/2019-ncov/need-extra-precautions/index.html

- 30. Hamer M., Gale CR., Kivimäki M., Batty GD. Overweight, obesity, and risk of hospitalization for COVID-19: a community-based cohort study of adults in the United Kingdom. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2020;117(35):21011-21013. 10.1073/pnas.2011086117 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Davies NG., Klepac P., Liu Y. et al. Age-dependent effects in the transmission and control of COVID-19 epidemics. Nat Med. 2020;26(8):1205-1211. 10.1038/s41591-020-0962-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]