Abstract

While a considerable number of employees across the globe are being forced to work from home due to the COVID-19 crisis, it is a guessing game as to how they are experiencing this current surge in telework. Therefore, we examined employee perceptions of telework on various life and career aspects, distinguishing between typical and extended telework during the COVID-19 crisis. To this end, we conducted a state-of-the-art web survey among Flemish employees. Notwithstanding this exceptional time of sudden, obligatory and high-intensity telework, our respondents mainly attribute positive characteristics to telework, such as increased efficiency and a lower risk of burnout. The results also suggest that the overwhelming majority of the surveyed employees believe that telework (85%) and digital conferencing (81%) are here to stay. In contrast, some fear that telework diminishes their promotion opportunities and weakens ties with their colleagues and employer.

Keywords: COVID-19, Telework, Videoconferencing, Career

Introduction

In the popular media, there have been many references to the potentially disruptive medium- and long-term impacts of the COVID-19 crisis on the careers of citizens from Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD) countries [e.g. 1–5]. In this respect, there is the fear that an economic crisis, as a consequence of the current health crisis, will serve as an intermediary factor [6–9]. It is expected that this economic crisis will have predominantly negative effects, such as declining economic growth, disintegrating supply chains and deteriorating employment prospects [9–14]. Nonetheless, opportunities may also arise. For instance, the upcoming crisis could allow for the emergence of a greener economy or promote a boost in online communication and its supporting technologies [15–18]. Along with flourishing online communication (technologies), some have also suggested that COVID-19 could be the basis for a breakthrough in telework [19, 20].

Telework is not a recent phenomenon: half a century ago employees already performed telework [21]. Because of inventions like the world wide web and increasingly powerful and affordable personal computers, a breakthrough in telework was forecasted, but it failed to materialise [22, 23]. In 2009, only 7.5% of employees in the EU-27 occasionally performed telework [24]. In the next 10 years, this proportion slowly increased to a mere 11% in 2019 [24]. After the COVID-19 outbreak, a considerable number of employees across the globe were forced to work from home. In the European Union, this proportion amounted to almost two fifths [25]. A slightly higher proportion was even witnessed in Belgium with more than half of the employees working from home [25]. According to popular media, increased telework is here to stay, even when COVID-19 would be under control.

However, it is unclear whether this belief in a structural breakthrough in telework exists only in the minds of journalists because of the limited or asymmetrical information they have access to, or whether it is shared by a wider proportion of the working population. In response to this, we investigate, in the current study, (i) to what extent the COVID-19 crisis has impacted employees’ personal views on telework and digital meetings (RQ3a) and (ii) whether these perceptions vary by sociodemographic or job characteristics (RQ3b). In addition, it is unclear at present (i) to what extent the broader population relates the current, sudden and obligatory increase in high-intensity telework because of COVID-19 to (un)beneficial outcomes in various life and career outcomes (RQ2a) and (ii) whether these perceptions vary by sociodemographic or job characteristics, too (RQ2b). To better interpret the answers to RQ2a and RQ2b, we also surveyed the participants on how they perceived the impact of telework in general (not in COVID-19 times) on other career aspects (RQ1a). The answers to these questions serve as our baseline for the interpretation of the findings related to RQ2a. Finally, we investigated, once again, whether these perceptions in non-COVID-19 times varied by sociodemographic or job characteristics (RQ1b).

Research question 1a (RQ1a): How do employees perceive the impact of telework, in general, on other career aspects?

Research question 1b (RQ1b): Are these perceptions heterogeneous by sociodemographic and job characteristics?

Research question 2a (RQ2a): How do employees perceive the impact of extended telework during the COVID-19 crisis on various life and career aspects?

Research question 2b (RQ2b): Are these perceptions heterogeneous by sociodemographic and job characteristics?

Research question 3a (RQ3a): To what extent has the COVID-19 crisis impacted employees’ personal views on telework and digital meetings?

Research question 3b (RQ3b): Are these perceptions heterogeneous by sociodemographic and job characteristics?

The contribution of the answers to the aforementioned research questions to both science and society is evident. From a societal viewpoint, policymakers, at the time, required immediate insights on how the working population was experiencing changes in their work situation. The first wave of mandatory telework in Belgium started on 18 March 2020 (until 3 May 2020), while our analyses were based on data collected between 25 March 2020 and 31 March 2020. A public report with preliminary findings of our survey was disclosed in April of that year. From a scientific point of view, the relevance of our research is threefold. First, the epidemic crisis has made researchers raise questions on how the COVID-19 telework policies affect employee attitudes, behaviours and productivity (amongst others) [26]. We wanted to add to this discussion by surveying changes of extended telework on personal views and life and career outcomes. Second, there is unanimity among researchers that telework in the COVID-19 context systematically differs from telework in normal times so that the existing knowledge on telework cannot be blindly adopted in the current context [27–29]. More specifically, it is characterised by compulsory, high-intensity telecommuting that has known a very abrupt onset [27]. Therefore, more research is needed on this epidemic-induced form of telework (see [28]). Third, by taking into account a broad set of items to construct our baseline in the context of RQ1a (see Main items) and a broad set of personal and job characteristics regarding RQ1b (see Survey construction), we can make a relevant contribution to the existing literature on telework. More concretely, we add to the relationship between burnout and telework and the variability of outcomes related to telework by the respondents’ migration background. Sardeshmukh, Sharma, and Golden [30], for example, noted that burnout research has often focused on traditional workers, but that studies have been slow to extend their interest to teleworkers. Van Steenbergen, van der Ven, Peeters, and Taris [31] state that few studies have examined the relationship between new ways of working and more distal employee outcomes such as burnout. Our study helps with enriching the research on this topic by disclosing the perceptions of employees on burnout prevention through telework. The link between telework and migration background is relevant as well since respondents with a migration background have a higher chance of being confronted with discrimination [32, 33] and their experiences with telework might be different because this working environment is characterised by less physical and personal interaction [34].

The epidemic-induced telework has nourished the interest of many researchers. A considerable number of papers have appeared on the topic of telework in the COVID-19 context, including non-empirical [e.g. 26] and empirical works based on both qualitative [e.g. 35,36] and quantitative methods [e.g. 27–29, 37–48]. Empirical papers that employ quantitative research in the context of telework and COVID-19 can differ substantially. First, some researchers were able to collect data immediately after telework became mandatory, while others were not [e.g. 47]. The timing of data collection is important as employees’ attitudes towards telework (in COVID-19 times) can differ over time: employees need time to adapt to the situation [27, 28]. Second, some studies focus on a specific target group like the educational sector instead of maintaining a broad focus concerning the target group [e.g. 41]. Third, some studies focus on a specific subtopic, for example, gender differences [e.g. 38,39, 44] or health implications [42]. For our research, we decided to collect data (i) immediately after telework became obliged, (ii) on a broad range of topics (iii) from a variety of different employees, to acquire an overall picture of this new concept of epidemic-induced telework. The ability to assess heterogeneity in the findings, thanks to a broad set of personal and job characteristics, discerns our research from other quantitative researches on telework in the COVID-19 context. Most studies only look at differences based on a small selection of variables and/or a limited number of sociodemographic characteristics (e.g. gender and age), which the researchers themselves often raise as a limitation in their work [37, 40]. For example, differences in experiences and attitudes of the epidemic-induced telework based on migration background or current health situation (i.e. recently or currently infected by COVID-19) is relevant and, as far as we know, not taken into account in other studies that focus on telework and COVID-19.

To summarize, by answering the aforementioned research questions, we not only contribute to the scientific literature on the (expected) socioeconomic consequences of the COVID-19 crisis [e.g. 6, 8, 49,50] but also to the scientific literature on telework and, more specifically, (i) the evaluation of telework by employees and (ii) the (objective and perceived) career consequences of telework [e.g. 23, 30, 51–54]. We present data on these issues gathered from a panel of Flemish employees, representative with respect to age, gender and education level. The next chapter provides more detail on the data.

Data

Main items

We analysed the responses of a sample of Flemish employees (see Sampling) as part of a broader COVID-19-related survey (for analysis of the other parts of this survey, we refer the reader to Lippens and colleagues [50]. In the context of the present study, three sets of items were submitted to the respondents; a complete list of item labels and statements can be found in Appendix A.

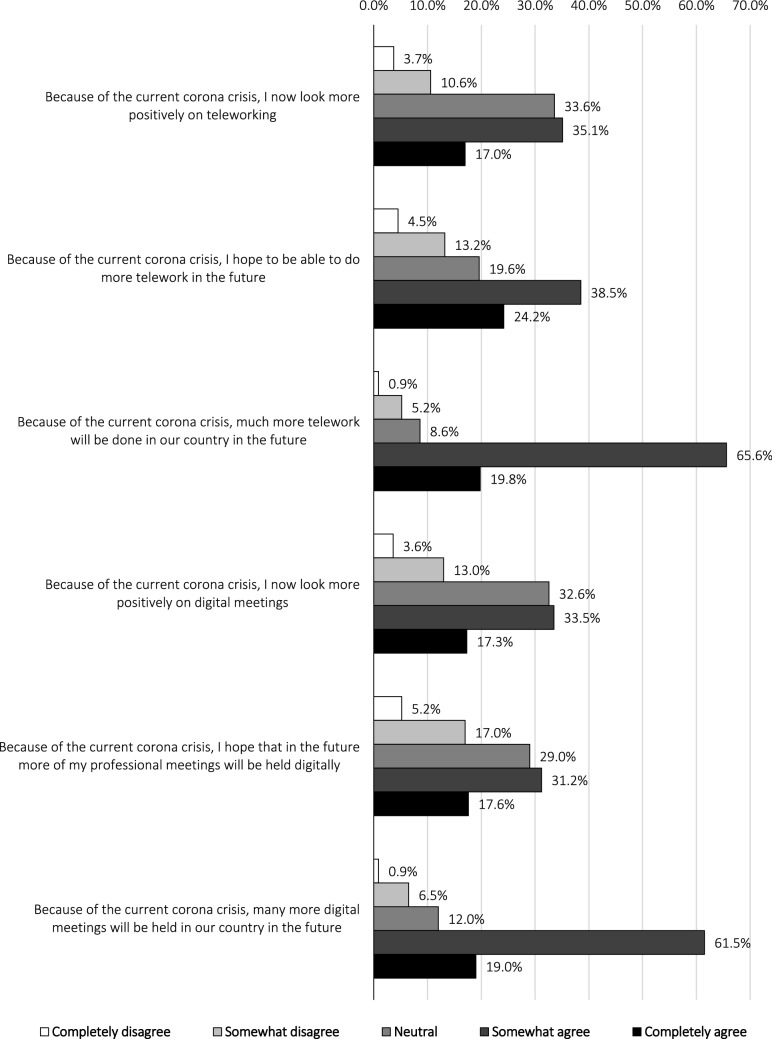

First, for RQ1a and RQ1b, all respondents (i.e. both active employees with the ability to telework (see Sampling) and employees who were temporarily unemployed at the time of data collection with the ability to telework (see Sampling) were asked to evaluate telework and its associated (perceived) career consequences in general, independent of how the COVID-19 crisis affected their current telework arrangements. Each of the ten items concerning general career consequences of telework featured in our survey was derived from meta-analyses or reviews on the consequences of telework [23, 53, 54]. More concretely, the items related to the following, frequently occurring themes in the telework literature: social isolation (item ‘my relationship with my colleagues’); professional isolation (‘my chances of promotion’ and ‘my professional development’); performance (‘my efficiency in performing tasks’ and ‘my concentration during work’); work–life balance (‘my work–life balance’); organisational attitudes (‘my overall satisfaction with my job’ and ‘my feeling of connectedness with my employer’); and other consequences of telework related to well-being (‘minimising my work-related stress’ and ‘minimising my chances of burnout’). This resulted in a combined list of both proximal outcomes (work–life balance and relationship with colleagues) and distal outcomes of telework (the remaining items), in line with the framework of Gajendran and Harrison [23]. The panel members were asked to evaluate these items on a five-point Likert scale, ranging from ‘a certainly negative effect’ (1) to ‘a certainly positive effect’ (5).

Second, relating to RQ2a and RQ2b, active employees (i.e. not temporarily unemployed), who were confronted with extended telework due to the COVID-19 crisis at the moment of the survey, were asked to evaluate statements regarding this situation of extended telework on a five-point Likert scale, ranging from ‘completely disagree’ (1) to ‘completely agree’ (5). We started by querying the respondents about their general satisfaction with the extended telework arrangement. Then, we surveyed them regarding the potential negative side effects due to extended telework because of the COVID-19 crisis: (i) family or professional conflicts, (ii) disturbances by roommates, and (iii) difficulties in combining different means of communication. As extended telework blurs the boundaries between work and family roles [23, 53], we would expect more conflicts and disturbances involving housemates, especially among those employees who are inexperienced teleworkers. According to Gajendran and Harrison [23], the beneficial impact of telework on work–family conflict and role stress largely depends on the learning curve associated with telecommuting, with more experienced teleworkers associating it with having an increased beneficial impact. Next, guidance from the employer––a critical condition for successful telework [52]––and the ease with which employees convinced their employer to offer telework arrangements in this exceptional situation of sudden and high-intensity telework were evaluated. Finally, we included items on task efficiency, commitment, work–life balance, relationship with colleagues, stress management, burnout prevention and work concentration.

A third and final set of items included for answering RQ3a and RQ3b dealt with the extent to which the COVID-19 crisis had changed the respondents’ views on telework and digital conferencing, and whether they believed that the level of telework and digital conferencing would be permanently increased as a result of this crisis. Our entire study sample (see Sampling) was asked whether (i) their personal view on telework had become more positive as a consequence of the current crisis, (ii) whether they hoped to perform more telework in the future, and (iii) whether they believed telework would increase in prevalence in the future. The respondents also received similar questions about digital meetings. Said items were evaluated on a five-point Likert scale, ranging from ‘completely disagree’ (1) to ‘completely agree’ (5).

Survey construction

The overall survey construction was grounded in the seminal surveying handbooks of Bethlehem and Biffignandi [55], Fowler [56] and Tourangeau, Conrad, and Couper [57]. The following paragraphs illustrate the important decisions we made to optimise the reliability and validity of the instrument. See Lippens and colleagues [50] for a more thorough discussion of these concerns and the institutional setting surrounding the survey.

First, non-differentiation (participants responding randomly, simply out of fatigue [55]) was counteracted by presenting a limited number of items at a time and using comprehensible wording (e.g. no double-barrelled constructions [58, 59]). In addition, following the advice of Weijters, Cabooter, and Schillewaert [60], the items were scored using fully-labelled five-point Likert scales. To stimulate high-quality responses, we deliberately excluded the option ‘I do not know’ from the scales [55].

Second, next to conscientious item development, the data quality and survey completion rates were enhanced by introducing raffle prizes and displaying a progress indicator, respectively [57, 61].

Third, adhering to the standards of first-rate surveying practices, the measuring instrument underwent pilot testing amongst 55 respondents. Throughout the pilot testing, the respondents were structurally questioned on (i) the clarity of expectations, (ii) the wording and (iii) topics that had potentially been neglected. Any issues detected during this pilot test were promptly resolved before sending out the survey.

Last, upon completing the data collection, data cleaning and sensitivity analyses were executed to further augment the quality of the response sets. The results remained robust after performing said analyses. Specifically, inattentive participants who failed to correctly answer a ‘trap’ question were not included in our basic sample (see Sampling). Also, those participants with very short completion times (i.e. within 5% of the shortest survey duration) were removed from the final panel in the robustness analyses.

To answer RQ1b, RQ2b and RQ3b, we also used all of the data from the part of the broader survey that addressed the sociodemographic and job characteristics of the respondents. This enabled us to assess the heterogeneity concerning the respondents’ gender, age, migration background, education level, relationship status, number of resident children and other (extended) family members, province, degree of urbanisation of their residence, and health status (before the COVID-19 crisis, overall current status and having been infected by COVID-19), as well as their type of employment contract, the part-time (versus full-time) nature of this contract, their tenure (with the current employer and in the current job), their level of job satisfaction, four key characteristics relating to the design of their job (i.e. autonomy, dependency on others, interaction outside of the organisation and feedback from others), and their sector of employment in detail.

Sampling

Ideally, the representativeness of our study sample would have been established using probability sampling, where all participants completed the survey—the latter being a condition that is often neglected [55–57]. However, practical constraints, such as the requirement for sampling through national registers, after ethical approval and follow-up by the registry office in cases of the non-response of participants, made us conclude that probability sampling was neither feasible nor desirable. Given the surging rates of telework and temporary unemployment, the scientific community and policymakers required immediate insights into how the working population was experiencing changes in their work situations.

The data collection of our study, which was based on web surveying, had several advantages. Compared to other methods (such as physical and telephonic interviews), web surveying allows data to be collected from a large sample. Here, 14,005 individuals filled in the survey. Finally, in our case, the sampling was presumably not hampered by a common limitation of web surveys––namely, an under-coverage of the studied population—through the exclusion of individuals not connected to the internet, in the sense that the teleworkers in our survey, by default, had internet access.

However, a substantial threat to the representativeness of our sample—as with nearly all web surveys—was self-selection (i.e. respondents themselves choosing whether they answer a call to participate or not). More concretely, self-selection is a peril to the representativeness of a sample when respondents differ systematically from non-responders in terms of the surveyed variables. To mitigate this threat, we applied a post-stratification strategy, as recommended by Bethlehem and Biffignandi [55] and Tourangeau and colleagues [57]. That is, we wanted our sample to be representative by (i) gender, (ii) age and (iii) education level based on the population of Flemish employees under the age of 65 years. Specifically, we aimed for the representativeness of this population using eight cells (‘strata’), combining two levels of each of the auxiliary variables: males versus females; tertiary education versus no tertiary education; and being at least 50 years old or being younger. Therefore, we identified the stratum, in the total sample of 14,005 respondents, that was most underrepresented when compared to the 2019 population averages for Flemish employees under 65 years, which was female workers without tertiary education aged 50 years or older. All complete responses (with correct answers to our ‘trap’ question; see above) from this stratum were included in the basic sample for this stratum. For the other seven strata, respondents were randomly drawn based on their proportions in the population. Applying this post-stratification resulted in a basic sample of 3821 individuals. In such a post-stratification strategy, the total number of complete responses used for the analyses depends on the number of responses in the most underrepresented stratum. Although this post-stratification has the disadvantage of only using a subset of the original sample, it allowed us to perform our analyses on a sample that is representative by gender, age and educational level.

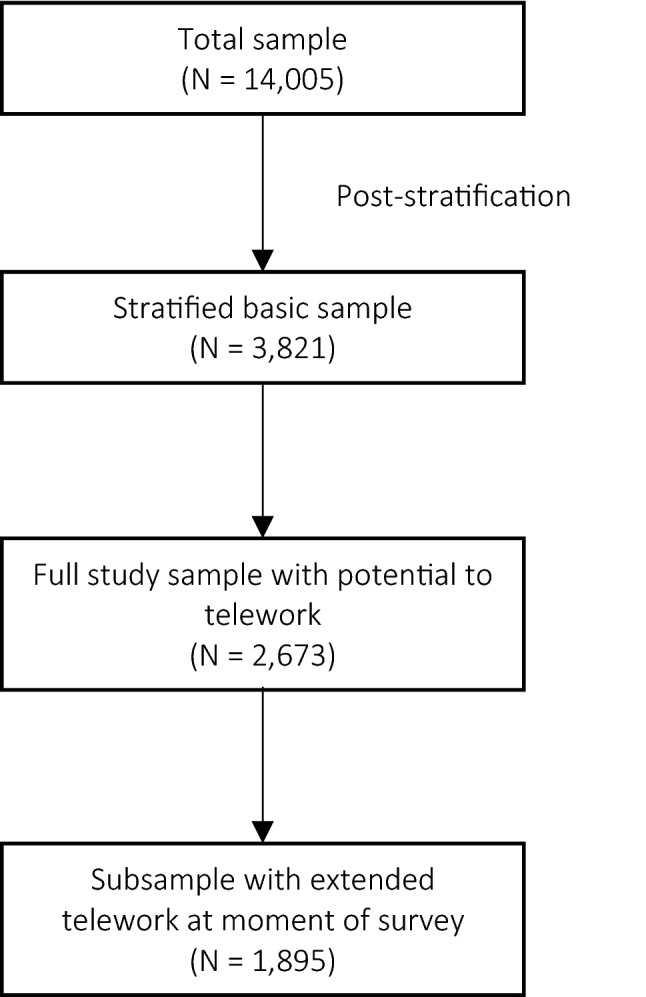

From this basic sample, we eventually excluded respondents whose jobs did not allow for telework. More concretely, respondents who indicated that less than 10% of their work could potentially be done via telework were removed from the panel, which resulted in a study sample of 2,673 participants. Moreover, the items related to RQ2a and RQ2b (see Main items) were only submitted to individuals experiencing extended telework due to the COVID-19 crisis at the moment of the survey. This subsample comprised 1895 individuals. Figure 1 summarises the sampling framework.

Fig. 1.

Study sample and subsample

Summary statistics

Table 1 contains the summary statistics concerning the personal and job characteristics of our study sample, and our subsample of individuals with extended telework resulting from the COVID-19 crisis. The scales we used are referred to in the notes of Table 1. Unsurprisingly, in the subsample of individuals who experienced extended telework certain personal characteristics are represented more compared to the full study sample (e.g. highly educated individuals are represented more as they are presumably more likely to telecommute; see [51]). The same applies to the representation of certain sectors (e.g. the educational sector is represented more, while logistics and transport and technology, for example, are sectors that are represented less compared to the full study sample).

Table 1.

Summary statistics

| Full study sample (N = 2673) |

Subsample: Temporarily extended telework (N = 1895) |

|

|---|---|---|

| Female | 0.510 (–) | 0.516 (–) |

| Age | 41.127 (10.665) | 41.059 (10.576) |

| Migration background | 0.026 (–) | 0.028 (–) |

| Tertiary education | 0.573 (–) | 0.654 (–) |

| Single | 0.192 (–) | 0.183 (–) |

| In a relationship but not cohabiting | 0.070 (–) | 0.068 (–) |

| In a relationship and cohabiting | 0.738 (–) | 0.750 (–) |

| Number of resident children | 0.923 (1.054) | 0.945 (1.058) |

| Resident parents | 0.067 (–) | 0.062 (–) |

| Resident family members (other than parents) | 0.035 (–) | 0.032 (–) |

| Resident others (not family) | 0.022 (–) | 0.021 (–) |

| Province of Antwerp | 0.273 (–) | 0.274 (–) |

| Province of West Flanders | 0.168 (–) | 0.146 (–) |

| Province of East Flanders | 0.318 (–) | 0.325 (–) |

| Province of Limburg | 0.065 (–) | 0.061 (–) |

| Province of Flemish Brabant | 0.175 (–) | 0.193 (–) |

| Living in the countryside or rural area | 0.364 (–) | 0.372 (–) |

| Living in the centre of a village | 0.255 (–) | 0.240 (–) |

| Living in the suburbs of a city | 0.224 (–) | 0.227 (–) |

| Living in the centre of a city | 0.157 (–) | 0.161 (–) |

| Health before the COVID-19 crisis (scale) | 4.138 (0.758) | 4.147 (0.761) |

| Current health (scale) | 3.943 (0.843) | 3.976 (0.823) |

| Never been infected by COVID-19 (definitely or likely) | 0.721 (–) | 0.732 (–) |

| Uncertain about having been infected by COVID-19 | 0.207 (–) | 0.195 (–) |

| Infected by COVID-19 at the moment (definitely or likely) | 0.038 (–) | 0.038 (–) |

| Infected by COVID-19 in the recent past (definitely or likely) | 0.034 (–) | 0.035 (–) |

| Employed on a temporary contract in the private sector | 0.027 (–) | 0.020 (–) |

| Employed on a permanent contract in the private sector | 0.779 (–) | 0.744 (–) |

| Employed on a regular contract in the public sector | 0.086 (–) | 0.103 (–) |

| Employed on a permanent appointment in the public sector | 0.108 (–) | 0.133 (–) |

| Part-time contract | 0.150 (–) | 0.144 (–) |

| Tenure with current employer (scale) | 2.847 (1.427) | 2.878 (1.418) |

| Tenure in current job (scale) | 2.304 (1.255) | 2.284 (1.234) |

| Satisfied with job (scale) | 4.001 (0.906) | 4.031 (0.899) |

| Autonomous in job (scale) | 4.043 (1.011) | 4.125 (0.949) |

| Dependent on others in job (scale) | 3.159 (1.084) | 3.136 (1.067) |

| Interaction outside of the organisation in job (scale) | 3.632 (1.325) | 3.576 (1.331) |

| Feedback from others in job (scale) | 3.113 (1.147) | 3.147 (1.114) |

| Sector: purchasing | 0.015 (–) | 0.015 (–) |

| Sector: administration | 0.086 (–) | 0.073 (–) |

| Sector: construction | 0.028 (–) | 0.022 (–) |

| Sector: communication | 0.022 (–) | 0.028 (–) |

| Sector: creative | 0.009 (–) | 0.006 (–) |

| Sector: provision of services | 0.077 (–) | 0.080 (–) |

| Sector: financial | 0.069 (–) | 0.084 (–) |

| Sector: health | 0.037 (–) | 0.026 (–) |

| Sector: catering and tourism | 0.019 (–) | 0.004 (–) |

| Sector: human resources | 0.061 (–) | 0.068 (–) |

| Sector: ICT | 0.102 (–) | 0.129 (–) |

| Sector: legal | 0.019 (–) | 0.024 (–) |

| Sector: agriculture and horticulture | 0.001 (–) | 0.001 (–) |

| Sector: logistics and transport | 0.055 (–) | 0.047 (–) |

| Sector: management | 0.056 (–) | 0.060 (–) |

| Sector: marketing | 0.024 (–) | 0.025 (–) |

| Sector: maintenance | 0.005 (–) | 0.003 (–) |

| Sector: education | 0.048 (–) | 0.063 (–) |

| Sector: research and development | 0.031 (–) | 0.037 (–) |

| Sector: government | 0.056 (–) | 0.069 (–) |

| Sector: production | 0.023 (–) | 0.019 (–) |

| Sector: technology | 0.031 (–) | 0.024 (–) |

| Sector: sales | 0.085 (–) | 0.058 (–) |

| Sector: other | 0.040 (–) | 0.035 (–) |

| Temporarily unemployed | 0.145 (–) | 0.000 (–) |

| % of work potentially done via telework | 61.175 (28.073) | 67.836 (24.907) |

| Temporarily extended telework | 0.709 (–) | 1.000 (–) |

No standard deviations are presented for binary variables. The levels (and values) for the health scales are: very bad (1); somewhat bad (2); neither bad nor good (3); somewhat good (4); and very good (5). The levels for the tenure scales are: less than 2 years (1); between 2 and 5 years (2); between 6 and 10 years (3); between 11 and 20 years (4); and more than 20 years (5). The levels for the job scales are: completely disagree (1); somewhat disagree (2); neutral (3); somewhat agree (4); and completely agree (5). The operationalisation of these variables is based on [62, 88–91]

Results

General findings

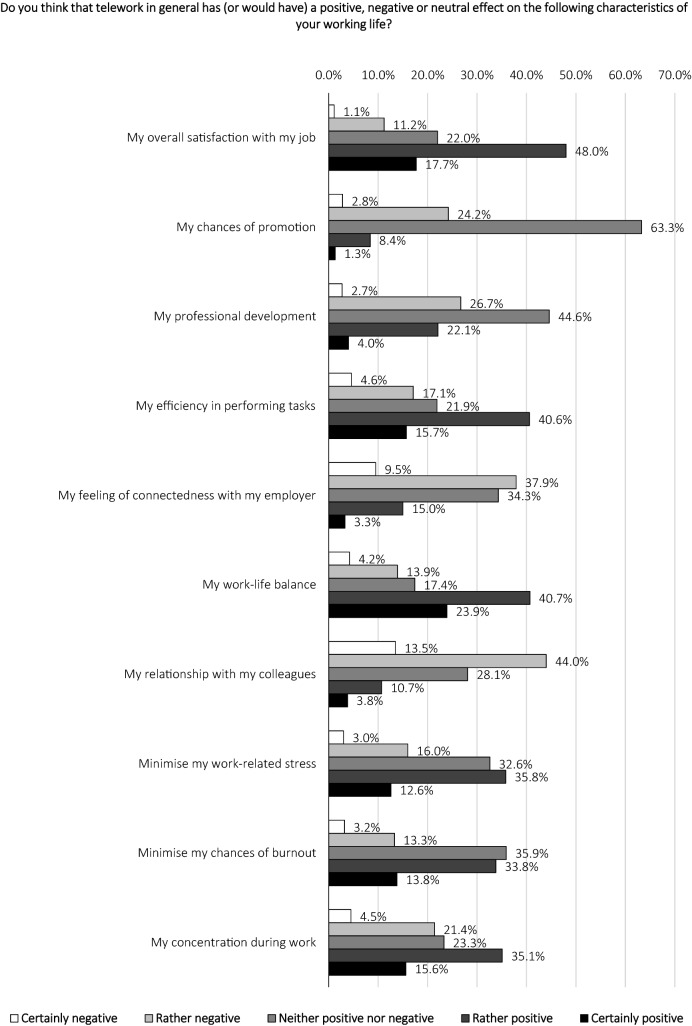

Perceived impact of telework in general on various career aspects

Figure 2 provides an overview of the panel’s responses to the survey items relating to RQ1a. As can be seen in this figure, most panel members believe that telework has a strong positive effect in general. Almost two-thirds (65.7%) indicate that their overall satisfaction with their job increases with telework. Similarly, 64.6% think that telework improves their work–life balance, whilst about half of the respondents believe that telework helps to minimise both work-related stress (48.4%) and the chance of burnout (47.6%). The effects of telework on performance are also positively evaluated, with about half of the respondents asserting that telework (i) improves their efficiency in performing tasks (56.3%) and (ii) increases their work concentration (50.7%). These positive effects of telework on job satisfaction, work–life balance, role stress, burnout and performance are in line with the findings of previous studies [23, 53, 54].

Fig. 2.

Perceived impact of telework in general on various career aspects: answers given (N = 2673)

Even though telework is mostly thought of positively, there are some downsides in the context of career development, future prospects and the social aspects of not working in a regular office. Most notably, about a quarter of the panel members believe that telework decreases their chance of promotion (27.0%) and hampers their professional development (29.4%). Additionally, more than half of the respondents think that telework harms their relationships with their colleagues (57.5%), while the sense of connectedness with their employer is lowered according to about half (47.4%) of the panel members. Again, these findings are in line with previous research. Charalampous and colleagues [53] noted that an increase in telework can isolate employees, both socially and professionally. In addition, Redman and colleagues [54] found that telework can reduce the support employees receive from their employer in their personal and professional development. This is also reminiscent of the relationship that Moens and colleagues [62] previously established between temporary contracts and loneliness at work.

Table 2 summarises the results of our descriptive analyses and linear regression analyses. Here, the responses are classified according to the personal and job characteristics surveyed, which will be discussed in subchapter “Heterogeneity in the findings” (in light of RQ1b). We performed linear regression analyses in which the standard errors were corrected for heteroscedasticity (White correction). Ordered logistic models and dummy specifications for the continuous explanatory variables included in the regression models lead to the same insights. A complete overview of the numerical regression results for the first item (i.e. perceived positive impact of telework on overall job satisfaction) is exemplified in Table 5 in Appendix B.

Table 2.

Perceived impact of telework in general on various career aspects: regression results (full study sample; N = 2673)

| Aspect | % perceiving positive impact on aspect | Significantly more pronounced if … | Significantly less pronounced if … |

|---|---|---|---|

| Overall job satisfaction | 65.7% | Province of East Flanders; better current health; longer tenure with current employer; more satisfied with job; sector is human resources or agriculture and horticulture; temporarily unemployed; higher % of work potentially done via telework; temporarily extended telework | Living in the centre of a city; better health before COVID-19 crisis |

| Promotion opportunities | 9.7% | Uncertain about having been infected by COVID-19; more satisfied with job; more autonomous in job; more feedback from others in job; sector is agriculture and horticulture; higher % of work potentially done via telework | Tertiary education; province of West Flanders; province of East Flanders; sector is communication, management or marketing |

| Professional development | 26.1% | Better current health; uncertain about having been infected by COVID-19; more satisfied with job; sector is agriculture and horticulture; higher % of work potentially done via telework | Tertiary education; better health before COVID-19 crisis; sector is communication; temporarily extended telework |

| Task efficiency | 56.3% | Female; better current health; uncertain about having been infected by COVID-19; longer tenure with current employer; sector is human resources, agriculture and horticulture or marketing; temporarily unemployed; higher % of work potentially done via telework | Tertiary education; better health before COVID-19 crisis; part-time contract |

| Commitment to employer | 18.4% | Migration background; better current health; sector is agriculture and horticulture; higher % of work potentially done via telework | Tertiary education; better health before COVID-19 crisis |

| Work–life balance | 64.6% | In a relationship and cohabiting; province of East Flanders; better current health; uncertain about having been infected by COVID-19 or infected by COVID-19 for the moment; sector is agriculture and horticulture; temporarily unemployed; higher % of work potentially done via telework; temporarily extended telework | Living in the centre of a city; more dependent on others in job; more feedback from others in job |

| Relationship with colleagues | 14.4% | Female; migration background; higher number of resident children; better current health; uncertain about having been infected by COVID-19; sector is maintenance; higher % of work potentially done via telework | Tertiary education; better health before COVID-19 crisis; longer tenure with current employer; more satisfied with job; temporarily extended telework |

| Stress management | 48.4% | Better current health; temporarily unemployed; higher % of work potentially done via telework | Higher number of resident children; better health before COVID-19 crisis; more dependent on others in job; more feedback from others in job; sector is education |

| Burnout prevention | 47.6% | Better current health; temporarily unemployed; higher % of work potentially done via telework | Better health before COVID-19 crisis; more dependent on others in job; more feedback from others in job |

| Work concentration | 50.7% | Female; higher age; better current health; uncertain about having been infected by COVID-19; more interaction outside organisation in job; temporarily unemployed; higher % of work potentially done via telework | Living in the centre of a city; better health before COVID-19 crisis; part-time contract; more feedback from others in job |

The proportion ‘perceiving positive impact’ corresponds to the sum of those who indicated ‘certainly positive effect’ and ‘rather positive effect’ to the related survey item (see Appendix A). The relationship to the personal and job characteristics was analysed by means of a linear regression analysis with heteroscedasticity-robust standard errors (in which all characteristics mentioned in Table 1 were included). The significance level was set as p < 0.05

Table 5.

Perceived positive impact of telework on overall job satisfaction: full regression estimates

| Linear regression analysis | Ordered logistic regression analysis | |

|---|---|---|

| Female | 0.058 (0.040) | 0.115 (0.086) |

| Age | − 0.002 (0.002) | − 0.006 (0.005) |

| Migration background | − 0.080 (0.125) | − 0.120 (0.275) |

| Tertiary education | − 0.047 (0.039) | − 0.102 (0.082) |

| Single (reference) | ||

| In a relationship but not cohabiting | 0.072 (0.079) | 0.153 (0.171) |

| In a relationship and cohabiting | 0.007 (0.051) | − 0.016 (0.106) |

| Number of resident children | 0.010 (0.018) | 0.027 (0.039) |

| Resident parents | − 0.140 (0.096) | − 0.300 (0.208) |

| Resident family members (other than parents) | 0.095 (0.106) | 0.128 (0.228) |

| Resident others (not family) | 0.125 (0.119) | 0.224 (0.236) |

| Province of Antwerp (reference) | ||

| Province of West Flanders | − 0.018 (0.055) | − 0.022 (0.113) |

| Province of East Flanders | 0.098** (0.045) | 0.233** (0.096) |

| Province of Limburg | 0.044 (0.076) | 0.133 (0.160) |

| Province of Flemish Brabant | 0.076 (0.054) | 0.182 (0.115) |

| Living in the countryside or rural area (reference) | ||

| Living in the centre of a village | − 0.020 (0.045) | − 0.048 (0.096) |

| Living in the suburbs of a city | − 0.020 (0.047) | − 0.051 (0.100) |

| Living in the centre of a city | − 0.121** (0.057) | − 0.234** (0.118) |

| Health before the COVID-19 crisis (scale) | − 0.068** (0.034) | − 0.157** (0.074) |

| Current health (scale) | 0.090*** (0.032) | 0.203*** (0.067) |

| Never been infected by COVID-19 (definitely or likely) (reference) | ||

| Uncertain about having been infected by COVID-19 | 0.084* (0.043) | 0.167* (0.091) |

| Infected by COVID-19 at the moment (definitely or likely) | 0.081 (0.105) | 0.224 (0.233) |

| Infected by COVID-19 in the recent past (definitely or likely) | 0.148 (0.095) | 0.309 (0.214) |

| Employed on a temporary contract in the private sector (reference) | ||

| Employed on a permanent contract in the private sector | − 0.069 (0.111) | − 0.175 (0.239) |

| Employed on a regular contract in the public sector | − 0.048 (0.127) | − 0.120 (0.274) |

| Employed on a permanent appointment in the public sector | − 0.080 (0.127) | − 0.212 (0.273) |

| Part-time contract | − 0.022 (0.051) | − 0.056 (0.108) |

| Tenure with current employer (scale) | 0.043** (0.020) | 0.096** (0.042) |

| Tenure in current job (scale) | − 0.038* (0.021) | − 0.081* (0.045) |

| Satisfied with job (scale) | 0.101*** (0.025) | 0.227*** (0.054) |

| Autonomous in job (scale) | 0.003 (0.019) | 0.008 (0.041) |

| Dependent on others in job (scale) | − 0.024 (0.017) | − 0.046 (0.037) |

| Interaction outside of the organisation in job (scale) | 0.018 (0.015) | 0.040 (0.032) |

| Feedback from others in job (scale) | − 0.015 (0.017) | − 0.028 (0.038) |

| Sector: purchasing | − 0.101 (0.165) | − 0.154 (0.339) |

| Sector: administration | 0.017 (0.098) | 0.079 (0.202) |

| Sector: construction | 0.143 (0.129) | 0.428 (0.263) |

| Sector: communication | − 0.117 (0.155) | − 0.155 (0.342) |

| Sector: creative | 0.109 (0.199) | 0.298 (0.414) |

| Sector: provision of services | 0.029 (0.099) | 0.129 (0.208) |

| Sector: financial | 0.065 (0.102) | 0.225 (0.221) |

| Sector: health | − 0.088 (0.129) | 0.011 (0.264) |

| Sector: catering and tourism | − 0.201 (0.155) | − 0.276 (0.295) |

| Sector: human Resources | 0.237** (0.102) | 0.592*** (0.223) |

| Sector: ICT | 0.004 (0.099) | 0.095 (0.213) |

| Sector: legal | − 0.076 (0.166) | 0.045 (0.356) |

| Sector: agriculture and horticulture | 0.386*** (0.117) | 0.740*** (0.237) |

| Sector: logistics and transport | 0.147 (0.110) | 0.417* (0.230) |

| Sector: management | 0.047 (0.108) | 0.183 (0.228) |

| Sector: marketing | 0.188 (0.134) | 0.433 (0.303) |

| Sector: maintenance | 0.090 (0.179) | 0.237 (0.344) |

| Sector: education | − 0.044 (0.127) | − 0.001 (0.271) |

| Sector: research and development | 0.027 (0.130) | 0.190 (0.274) |

| Sector: government | 0.191 (0.117) | 0.467* (0.258) |

| Sector: production | 0.178 (0.138) | 0.483* (0.283) |

| Sector: technology | 0.182 (0.126) | 0.471* (0.268) |

| Sector: sales | 0.048 (0.100) | 0.192 (0.212) |

| Sector: other (reference) | ||

| Temporarily unemployed | 0.199*** (0.068) | 0.422*** (0.136) |

| % of work potentially done via telework | 0.006*** (0.001) | 0.014*** (0.002) |

| Temporarily extended telework | 0.184*** (0.057) | 0.384*** (0.115) |

| N | 2673 | 2673 |

| R2 (adjusted)/McFadden R2 | 0.087 (0.066) | 0.037 |

The presented statistics are coefficient estimates and standard errors in parentheses based on a regression analysis with heteroscedasticity-robust standard errors. Intercepts and cut-off values are not presented. The significance levels cannot be given an absolute interpretation due to potential multiple testing problems (false positives)

* (**) ((***)) indicates significance at the 10% (5%) ((1%)) level

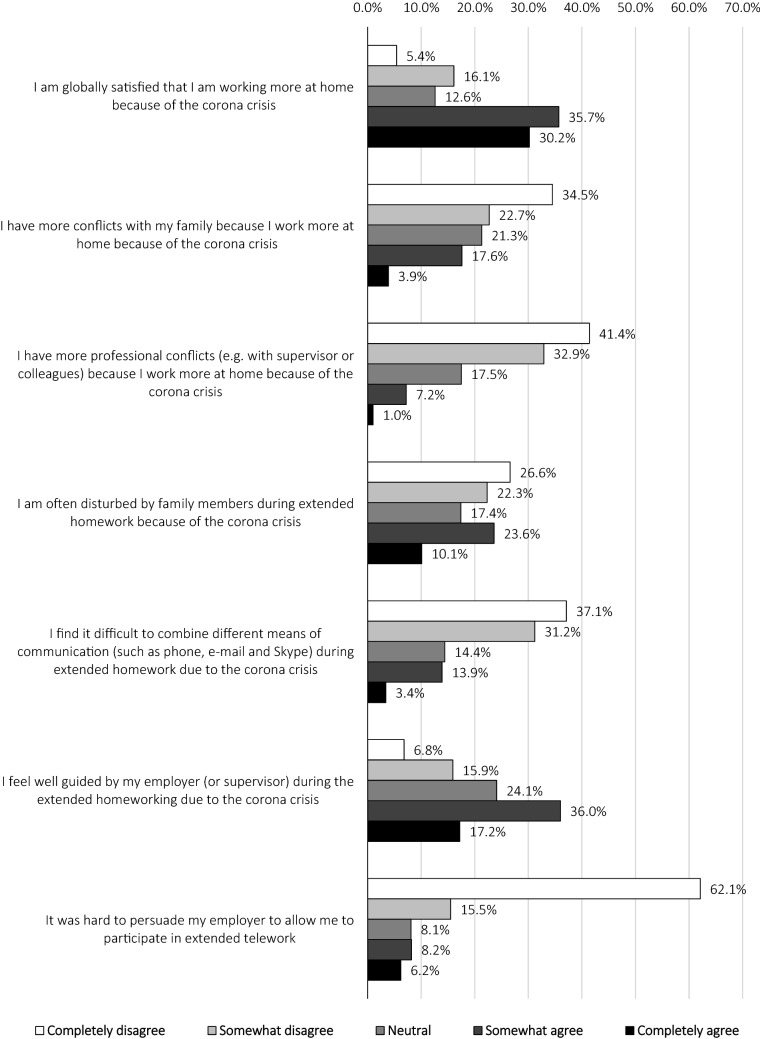

Perceived impact of extended telework during the COVID-19 crisis on various life and career aspects

Figure 3 illustrates that a large majority of our subsample with extended telework is satisfied with the increase in telework (65.9%). This result is not surprising, given three complementary observations. First, notwithstanding the sudden onset of the COVID-19 crisis that forced employers to rapidly transition to telework without being able to prepare, more than half of the subsample feels well guided by their employer (53.2%), which is a critical condition for successful telework [52]. Second, the idea that the extended telework is beneficial for stress and burnout prevention, and on-the-job concentration holds for almost half of the employees with extended telework (45.7% reportedly experience less work-related stress, 44.7% note that they can concentrate better on their work and 42.7% believe the extended telework decreases their chances of burnout in the near future). In addition, more than half (55.7%) feel that extended telework has a positive effect on their work–life balance. Third, only a small share of the respondents with extended telework (17.3%) experience significant difficulties in combining different means of communication while performing telework.

Fig. 3.

Perceived impact of extended telework during the COVID-19 crisis on various life and career aspects: answers given (N = 1895)

Beyond the professional benefits, the negative effects of extended telework on non-career-related aspects are rather limited. About half of the employees with extended telework (57.2%) do not encounter additional conflicts with their family members as a result of the telework arrangements, nor are they more often disturbed by their family members (48.9%). However, the idea of reduced social interaction with their colleagues and employer are materialised, with almost two-thirds reporting a weaker bond with their colleagues (64.0%) and more than half feeling less connected with their employer (56.0%).

In line with our results, Bolisani and colleagues [37] found that the obstacles and negative factors of smart working were, on the whole, perceived as less significant than the benefits in their online survey of smart workers in Italy during the COVID-19 pandemic. In addition, Syrek and colleagues [28] also found an increase in job satisfaction due to the extended telework in a Dutch sample. Furthermore, the research of Bolisani and colleagues [37] underlines the difficulty to maintain work contacts. Moreover, Carillo and colleagues [27] mention the lack of contacts and informal relationships with colleagues as well as the lack of feedback from managers as major obstacles to telework adjustments in France. In contrast to our findings, Syrek and colleagues [28] observed initial declines in work–non-work balance during the crisis’ onset (March and April 2020) but observe a recovery of this balance after one month (as of May 2020).

An overview of the results of our descriptive analyses and linear regression analyses can be found in Table 3. The responses are again classified according to the personal and job characteristics surveyed, which will be discussed in subchapter “Heterogeneity in the findings” (in light of RQ2b). The survey items are analysed by analogy with those discussed in the previous subsection.

Table 3.

Perceived impact of extended telework during the COVID-19 crisis on various life and career aspects: regression results (subsample with extended telework at moment of survey; N = 1895)

| Aspect | % perceiving impact on aspect | Significantly more pronounced if … | Significantly less pronounced if … |

|---|---|---|---|

| Happy with extended telework | 65.9% | Better current health; part-time contract; sector is creative or health; higher % of work potentially done via telework | Higher number of resident children; living in the centre of a village or living in the centre of a city; better health before COVID-19 crisis; more satisfied with job; more autonomous in job, more dependent on others in job; more interaction outside organisation in job; more feedback from others in job |

| More family conflicts related to extended telework | 21.5% | Higher number of resident children; better health before COVID-19 crisis; more dependent on others in job | Higher age; province of Limburg; better current health; uncertain about having been infected by COVID-19; higher % of work potentially done via telework |

| More professional conflicts related to extended telework | 8.2% | Resident family members (other than parents); resident others (no family); better health before COVID-19 crisis; more dependent on others in job; sector is catering and tourism | Migration background; resident parents; better current health; more satisfied with job; more feedback from others in job; higher % of work potentially done via telework |

| Often disturbed by roommates during extended telework | 33.7% | In a relationship and cohabiting; higher number of resident children; more dependent on others in job | Higher age; better current health; sector is agriculture and horticulture; higher % of work potentially done via telework |

| Difficult to combine different means of communication during extended telework | 17.3% | Higher number of resident children; province of West Flanders; longer tenure in current job; more dependent on others in job | In a relationship and cohabiting; resident parents; better current health; longer tenure with current employer; more autonomous in job; more feedback from others in job; sector is ICT, research and development or sales; higher % of work potentially done via telework |

| Well guided by my employer during extended telework | 53.2% | Tertiary education; living in the centre of a village; better current health; more satisfied with job; more feedback from others in job; sector is agriculture and horticulture; higher % of work potentially done via telework | Sector is creative |

| Difficult to convince employer to introduce extended telework | 14.4% | Province of West Flanders; infected by COVID-19 for the moment (probably); sector is maintenance | Higher age; migration background; tertiary education; more satisfied with job; more autonomous in job; more feedback from others in job |

| Higher task efficiency related to extended telework | 45.2% | Higher age; province of East Flanders; better current health; higher % of work potentially done via telework | Better health before COVID-19 crisis; more feedback from others in job; sector is education |

| Higher commitment to employer related to extended telework | 10.8% | Higher age; migration background; better current health; higher % of work potentially done via telework | Living in the centre of a village; better health before COVID-19 crisis |

| Better work–life balance related to extended telework | 55.7% | Province of Limburg; better current health; uncertain about having been infected by COVID-19, infected by COVID-19 for the moment (probably); infected by COVID-19 in the recent past (probably); sector is human resources; higher % of work potentially done via telework | Higher number of resident children; living in the centre of a city; better health before COVID-19 crisis; more autonomous in job; more feedback from others in job |

| Better relationship with colleagues related to extended telework | 10.2% | Higher age; province of East Flanders; better current health; higher % of work potentially done via telework | Better health before COVID-19 crisis; more satisfied with job |

| Better stress management related to extended telework | 45.7% | Better current health; uncertain about having been infected by COVID-19, infected by COVID-19 for the moment (probably) or infected by COVID-19 in the recent past (probably); higher % of work potentially done via telework | Higher number of resident children; better health before COVID-19 crisis; more dependent on others in job; more feedback from others in job |

| Better burnout prevention related to extended telework | 42.7% | Higher age; better current health; infected by COVID-19 for the moment (probably) or infected by COVID-19 in the recent past (probably); higher % of work potentially done via telework | Higher number of resident children; better health before COVID-19 crisis; more feedback from others in job |

| Higher work concentration related to extended telework | 44.7% | Higher age; better current health; infected by COVID-19 for the moment (probably); employed in public sector; higher % of work potentially done via telework | Higher number of resident children; better health before COVID-19 crisis; more dependent on others in job; more feedback from others in job; sector is education |

The proportion ‘perceiving impact’ corresponds to the sum of those who indicated ‘completely agree’ and ‘somewhat agree’ to the related survey item (see Appendix A). The relationship to the personal and job characteristics was analysed by means of a linear regression analysis with heteroscedasticity-robust standard errors (in which all characteristics mentioned in Table 1 were included). The significance level was set as p < 0.05

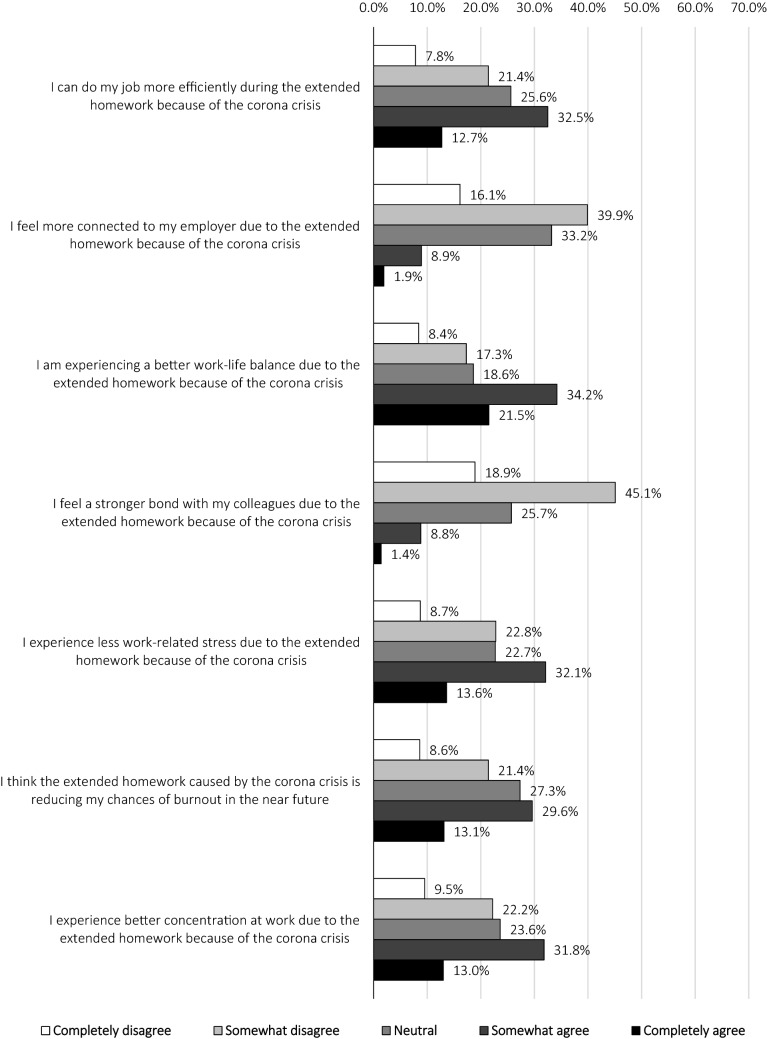

Perceived impact of the COVID-19 crisis on self-view of telework and digital meetings

Figure 4 illustrates how the positive beliefs and experiences about increased telework extend to the correspondents’ beliefs about the future of telework and digital meetings. About half of the panel members foster a more positive outlook on telework (52.0%) and organising digital meetings (50.8%) due to the COVID-19 crisis. These feelings translate into an increased desire to pursue more telework (62.7%) and to have more digital meetings (48.8%). The majority of the respondents believe that both telework (85.3%) and digital meetings (80.5%) will also occur more often in the future. In line with our findings, Diab-Bahman and Al-Enzi [40] find that the majority in their sample of Kuwaiti employees hope for changes to the conventional working conditions post-crisis, too.

Fig. 4.

Perceived impact of the COVID-19 crisis on self-view of telework and digital meetings: answers given (N = 2673)

Table 4 summarises the results of our descriptive analyses and linear regression analyses. Once more, the responses are classified according to the personal and job characteristics surveyed, which will be discussed in subchapter “Heterogeneity in the findings” (in light of RQ3b). The survey items are analysed by analogy with those discussed in the two previous subsections.

Table 4.

Perceived impact of the COVID-19 crisis on self-view of telework and digital meetings: regression results (full study sample; N = 2673)

| View | % perceiving impact | Significantly more pronounced if … | Significantly less pronounced if … |

|---|---|---|---|

| More positive self-view of telework | 52.0% | Female; in a relationship but not cohabiting; better current health; infected by COVID-19 for the moment (probably); temporarily unemployed; higher % of work potentially done via telework | Tertiary education; more autonomous in job; sector is ICT or legal |

| Hope for more telework in the future | 62.7% | Female; in a relationship but not cohabiting or in a relationship and cohabiting; uncertain about having been infected by COVID-19; sector is creative, agriculture and horticulture or marketing; temporarily unemployed; higher % of work potentially done via telework; temporarily extended telework | Tertiary education; living in the centre of a city; more satisfied with job; more autonomous in job; more feedback from others in job |

| Believe in overall more telework in country in future | 85.3% | Resident family members (other than parents); better health for the moment; employed on permanent appointment in public sector; part-time contract; more feedback from others in job; temporarily extended telework | |

| More positive self-view on digital meetings | 50.8% | Better current health; sector is agriculture and horticulture; higher % of work potentially done via telework | |

| Hope for more digital meetings in the future | 48.8% | Higher number of resident children; province of Limburg; sector is human resources, agriculture and horticulture, management, marketing, education or sales; higher % of work potentially done via telework | |

| Believe in overall more digital meetings in the country in future | 80.5% | Tertiary education; resident family members (other than parents); part-time contract; more feedback from others in job | Longer tenure in current job |

The proportion ‘perceiving impact’ corresponds to the sum of those who indicated ‘completely agree’ and ‘somewhat agree’ to the related survey item (see Appendix A). The relationship to the personal and job characteristics was analysed by means of a linear regression analysis with heteroscedasticity-robust standard errors (in which all characteristics mentioned in Table 1 were included). The significance level was set as p < 0.05

Heterogeneity in the findings

Differences in the findings by gender

When it comes to telework in general (not in COVID-19 times), women are more positive regarding task efficiency, work concentration and relationships with colleagues. In this respect, our findings corroborate a growing body of evidence on telecommuting, such as the systematic review of Charalampous and colleagues [53] and the meta-analysis of Gajendran and Harrison [23]. That is, women reportedly experience a smaller negative effect of telework on potential work–family conflicts and a greater increase in job performance compared to men. An underlying explanation might be found in traditional gender roles, which presumably give women more care responsibilities than men. Telework can be a way to facilitate this combination.

While women are more positive about certain aspects of telework in general, they are not significantly more positive about aspects of extended telework in COVID-19 times. Again, traditional gender roles might provide an explanation: it could be more difficult for women to combine care responsibilities with job-related responsibilities due to school and childcare closures in COVID-19 times [63].

Thus, when not faced with an epidemic, the women in our sample are more often advocates of telework. They even become more fond of telework (in normal times) due to the COVID-19 crisis and indicate the strongest desire to perform more telework in the (post-crisis) future. In line with the findings of Nguyen and Armoogum [44] and Wong and colleagues [48], increased opportunities for telework are perceived by Flemish women as a solution to pre-existing burdens. Before the health crisis, Flanders already saw an increase in telework—a tendency especially outspoken among women [64]. The obligatory telework during lockdown could have further stimulated this particular tendency. Whereas studies across the world indicate women’s mixed experiences with telework during the pandemic [36, 38, 39, 42, 45], cross-country variations on (traditional) gender roles—regarding the division of labour—could underly these differences in telework experience, and consequently, women’s post-crisis outlook on telework [65].

Differences in the findings by the number of resident children

The answers to the questions on epidemic-induced telework (as opposed to telework in general) substantially vary by the number of resident children: respondents with children are less satisfied with the extended telework. This is not surprising as, during the COVID-19 crisis, telework often has to be combined with taking care of children (due to the closure of schools and daycare facilities), which is a challenging combination that does not occur in regular telework situations [63]. Unsurprisingly, they experience more family conflicts, are more often disturbed by roommates and find it more difficult to combine different means of communication during the extended telework. Moreover, they less often report an improved work–life balance, stress management, burnout prevention and work concentration. Our findings are in line with the findings of Nguyen and Armoogum [44], who state that females living with at least two children are less likely to have a good perception of homeworking in the COVID-19 context.

Differences in the findings by age

What telework in general (not in COVID-19 times) is concerned, older respondents more often agree that it has a positive effect on their concentration. This might relate to the study of Aguilera and colleagues [51], who found that telework is often associated with a quieter and less stressful work environment, which older respondents may benefit more from when it comes to focusing on tasks.

More numerous, however, are the age differences in the items related to extended telework during the COVID-19 epidemic. Older employees report that they can work more efficiently, have higher levels of concentration, have a higher commitment and have better burnout prevention thanks to the extended telework, amongst other things. In addition, older employees reportedly experience significantly fewer conflicts with family members due to the extended telework and are less often disturbed by them. Previous research has shown that older participants might be less accustomed to telework [66]. Our results, however, show that their experiences with telework are evaluated very positively. This might be related to the fact that older people are at higher risk from COVID-19 [67], and, thus, are more appreciative of the possibility of working from home. In general, several studies show that the level of fear of disease or concern about the COVID-19 virus plays a role in the evaluation of telework [44, 46].

While older employees are more outspoken on the benefits of telework in our sample, Raišiene and colleagues [45] find the opposite. In their study, older generations of employees in Lithuania tend to emphasize the disadvantages of telework, while younger employees tend to emphasize the advantages rather than the disadvantages of telework. Again, cultural differences might help in explaining these opposed findings. The authors state that Lithuanian companies have not enabled their employees to telework at the same rate as companies in other European countries have since 2005 [45]. Possibly, older employees (who thus belong to a generation that did not grow up with digital technologies) originating from a country where telework is less familiar might be more sceptical towards this new way of working. Another explanation could be the limited sample size in the study of Raišiene and colleagues [45], especially in comparison with our sample.

Differences in the findings by education level

Respondents who attained a tertiary level of education are less positive when it comes to the effects of telework in general on promotion opportunities, professional development, task efficiency, commitment and relationships with colleagues. This is surprising because highly skilled and autonomous workers are the most likely group of workers to telecommute [51]. An explanation for this finding might be that these workers, being the most likely to telecommute, might already have been accustomed to the benefits of telework. Being more familiar with and being more accustomed to the benefits of telework, can also help in explaining why employees with a tertiary level of education more often state (i) to be well guided by their employer during extended telework in COVID-19 times, (ii) not perceiving difficulties to convince their employer to introduce extended telework because of the pandemic, (iii) not having a more positive self-view on telework because of the COVID-19 crisis and (iv) not hoping to telework more often in the future.

In line with our results on professional isolation, Raišiene and colleagues [45] also find evidence of concerns about missing important information and doubts regarding manager’s evaluation amongst higher educated employees. However, they do observe that higher educated employees experience a higher self-confidence and satisfaction with the opportunity to make independent decisions thanks to the extended telework, while lower educated employees face a lower involvement and organizational commitment due to the extended telework. The authors interpret these results in terms of the nature of the work performed by higher educated employees compared to lower educated employees, which can help in explaining the difference with our findings (as we take into account task characteristics like autonomy, interaction and dependency, while Raišiene and colleagues [45] do not).

Differences in the findings by migration background

Interestingly, the respondents with a migration background in our panel report stronger positive effects of both telework in general as well as the extended telework than employees without a migration background. More precisely, they report a stronger positive impact of telework in general on their relationships with their colleagues and a higher commitment towards their employer. The latter also applies to extended telework. Moreover, they experience fewer professional conflicts and also found it less difficult to convince their employer to allow them to telecommute during the COVID-19 crisis.

Although these findings might equally relate to a selection problem, in the sense that a selective subset of persons with a migration background might have selected themselves for our sample, we put forward two potential explanations why employees with a migration background might fare better than others on these aspects. A first explanation is based on discrimination research that shows that, in jobs where interaction with colleagues and customers is prominent, ethnic minorities are more likely to be discriminated against in the selection process [68–73]. Under the assumption that telework, by definition, reduces physical, personal interaction [34], the negative effects of the perceived discrimination may be reduced. A second explanation lies in the claim that ethnic salience—the extent to which one’s personally identifying characteristics and affiliations underscore one’s ethnicity (e.g. skin tone)—also contributes to increased discriminatory behaviour in a professional work context [74–77]. Working from home could make one's personal characteristics less conspicuous due to the barrier created by remoteness. Direct colleagues, for example, literally see each other less frequently (i.e. they have less face-to-face interaction [78, 79]). In these instances, ethnic cues are less noticeable and, potentially, diminish the negative repercussions of discriminatory behaviour.

Differences in the findings by health status

Employees that were uncertain about being infected by COVID-19 and employees that suspect or know they had been infected by COVID-19 at the moment of the data collection are more positive on the effect of extended telework on stress management, burnout prevention, work concentration and work–life balance (compared to employees that were (rather) sure they were not infected). An explanation could be that extended telework provides these employees with more peace of mind which could have a positive effect on their stress, burnout, concentration and work–life balance. In addition, employees that worry about their health might be more appreciative of the possibility of working from home.

Differences in the findings by job characteristics

Respondents who strongly depend on others in their job, as well as those who receive a lot of feedback, share the positive views of telework in general on work–life balance, stress management and burnout prevention less often. When one’s job is highly dependent on others, coordination problems with colleagues due to telework likely occur more frequently. Such coordination problems can cause enhanced negative consequences for telework [52]. In turn, respondents who receive a lot of feedback, which is considered an important aspect of job satisfaction and job performance [80, 81], might fear receiving less feedback when performing telework. In this respect, previous research has indeed shown that reduced face-to-face interaction restricts the possibility of giving immediate feedback or praise [30, 82]. This is exemplified by the findings of Carillo and colleagues [27], who identified that feedback (from the manager and the organisation at large) is one of the major obstacles in transitioning to extended telework in COVID-19 times.

Similar to general telework in normal times, those respondents who are more dependent on others in their jobs encounter more negative consequences from extended telework due to the COVID-19 crisis. In particular, during this period of extended telework, they report more conflicts with colleagues and family, are more disturbed by roommates, and have a harder time combining the different means of communication available to them. This is in line with the study of Carillo and colleagues [27] where work interdependence was found to negatively influence telework adjustment and the study of Chong and colleagues [83] where the authors found that daily COVID-19 task setbacks are positively related to next-day work withdrawal behaviour, especially for teleworkers who have higher task interdependence with their colleagues.

Lower general satisfaction with extended telework also applies to respondents who are used to receiving a lot of feedback, as well as those who are used to a lot of interaction outside their organisation and those experiencing high levels of job autonomy. The latter has also previously been reported (in non-COVID-19 times) by Baltes, Briggs, Huff, Wright, and Neuman [84] and Allen and Shockley [52], who found that managers and professionals who experience a greater degree of autonomy in their jobs benefitted to a lesser extent from flexible work arrangements in terms of work–life balance because telework potentially did not greatly alter their job characteristics. More detail on the differences based on job characteristics in the results concerning extended telework can be found in Table 3.

Finally, respondents who experience a high level of autonomy less often report an increasingly positive view on telework in COVID-19 times and have less of a desire to telework more in the future. The latter is also the case for respondents who receive a lot of feedback on their job. As illustrated above, the fear of a reduction in feedback might be related to this.

Differences in the findings by sector

Due to the large and diverse sample, our survey also allows for an initial exploration of differences in perception across sectors.1 First, workers active in education are less likely to experience the (potential) advantages of the suddenly extended telework. More concretely, compared to other sectors, workers in education report fewer gains in efficiency and concentration. These results can be explained by the numerous challenges educators face in terms of online learning and student assessments [85]. Second, we find that, in some sectors, workers experience more problems in combining different means of communication (the average across the total sample equals 17.3%). In particular, workers active in ICT, research and development and sales attest to this. One explanation for this result might be that workers from these sectors already spent a substantial amount of time organising electronic communication and, hence, have an increased risk of communication overload due to extended telework [e.g. 86]. In any case, our finding that approximately one in six Flemish workers experiences trouble in combining different sources of communication highlights the value of proper education on digital communication—even more so in the already digitally savvy sectors such as ICT, research and development and sales.

In general, the data suggest that many workers across sectors are won over by digital meetings. Indeed, 50.8% of the respondents in our sample hopes to have more digital meetings in the future. However, we find substantial heterogeneity across sectors in the impact of COVID-19 on perceptions regarding telework and digital meetings. We find that these hopes are even more common in sectors like human resources, management, marketing, education and sales. In contrast, we find that, again, workers from the ICT sector were less likely to report a positive impact of COVID-19 on their views regarding telework. These results implicate that, in the general workforce, there could be a willingness for further explorations of hybrid forms of tele- and on-site work. For policymakers, we believe this heterogeneity in perceptions creates opportunities to guide the implementation of post-crisis telework through sector-specific agreements. This could be especially interesting in the Belgian (Flemish) context given Belgium’s rich collective bargaining structure [e.g. 87].

Conclusion

This article has provided insights into how a carefully composed sample of Flemish employees have experienced telework, both in general and in its extensive form due to the COVID-19 crisis, and how the COVID-19 crisis has affected their outlook on the future of telework and digital conferencing. In addition, we investigated how telework experiences and corresponding future outlooks are heterogeneous by personal and job characteristics. Thereby, we have not only contributed to the brand new scientific literature on the (expected) socioeconomic consequences of the COVID-19 crisis, but also to the overall scientific literature on telework.

The perceived effects of the extended telework on specific facets of the respondents’ personal and professional lives are largely in line with the findings of previous studies. For example, many positive characteristics (e.g. increased efficiency and better work–life balance) have been attributed to telework, while, at the same time, potentially negative impacts on promotion opportunities and work relationships were underlined. To the satisfaction of two-thirds of the respondents, Flemish workers anticipate that the COVID-19 crisis will make telework and digital conferencing much more common in the future in Belgium.

We found several associations between telework and other aspects of personal and professional life that, to the best of our knowledge, have not previously been documented in the scientific literature. First, our study zoomed in on the perceptions of employees on burnout prevention facilitated by telework. About half of the respondents indicated that telework helps them to lower the chance of burnout. This finding is especially true for older workers but to a lesser extent for those workers with a higher number of resident children. Second, we found that the respondents with a migration background report stronger positive effects of telework in that they have better relationships with colleagues and a higher commitment to their employer than employees without a migration background. Moreover, respondents with a migration background attribute fewer professional conflicts to the increased telework due to the COVID-19 crisis. As discussed, this finding appears to be consistent with previous empirical research on ethnic labour market discrimination. Because of the (extended) telework, there is less physical contact and hence less opportunity for interethnic conflict to arise or discriminatory behaviour from colleagues, customers or employers to become apparent. We recommend that future studies, using different research designs, examine whether these associations are robust and reveal objective, causal mechanisms.

Because similar studies in other countries sometimes reveal opposing results [e.g. 36, 45], another interesting direction for future research includes cross-country comparative research that takes cultural differences into account when it comes to the evaluation of epidemic-induced telework. The differences amongst cultures concerning traditional gender norms might play a role in how women versus men experience extended telework in times of a pandemic. Finally, experiences with extended telework might differ between countries where telework was already relatively common before the COVID-19 crisis (e.g. Belgium) and countries where the frequency of telework is at a low ebb.

Appendix A

Survey items concerning outcome variables

Perceived impact of telework in general on various career aspects

The following statements are about your general view of telework (and therefore not specifically about the extended telework you may currently be experiencing). Do you think that telework in general has (or would have) a positive, negative or neutral effect on the following characteristics of your working life? Scale: certainly negative effect (1); rather negative effect (2); neither positive nor negative effect (3); rather positive effect (4); certainly positive effect (5).

(Overall job satisfaction) My overall satisfaction with my job.

(Promotion opportunities) My chances of promotion.

(Professional development) My professional development.

(Task efficiency) My efficiency in performing tasks.

(Commitment to employer) My feeling of connectedness with my employer.

(Work–life balance) My work–life balance.

(Relationship with colleagues) My relationship with my colleagues.

(Stress management) Minimise my work-related stress.

(Burnout prevention) Minimise my chances of burnout.

(Work concentration) My concentration during work.

Perceived impact of extended telework during the COVID-19 crisis on various life and career aspects

The following statements are about your experience with extended telework due to the current COVID-19 crisis. Please indicate to what extent you agree with the statements on a scale from ‘completely disagree’ (1) to ‘completely agree’ (5).

(Happy with extended telework) I am globally satisfied that I am working more at home because of the corona crisis.

(More family conflicts related to extended telework) I have more conflicts with my family because I work more at home because of the corona crisis.

(More professional conflicts related to extended telework) I have more professional conflicts (e.g. with supervisor or colleagues) because I work more at home because of the corona crisis.

(Often disturbed by roommates during extended telework) I am often disturbed by family members during extended homework because of the corona crisis.

(Difficult to combine different means of communication during extended telework) I find it difficult to combine different means of communication (such as phone, e-mail and Skype) during extended homework due to the corona crisis.

(Well guided by my employer during extended telework) I feel well guided by my employer (or supervisor) during the extended homeworking due to the corona crisis.

(Difficult to convince employer to introduce extended telework) It was hard to persuade my employer to allow me to participate in extended telework.

(Higher task efficiency related to extended telework) I can do my job more efficiently during the extended homework because of the corona crisis.

(Higher commitment to employer related to extended telework) I feel more connected to my employer due to the extended homework because of the corona crisis.

(Better work–life balance related to extended telework) I am experiencing a better work–life balance due to the extended homework because of the corona crisis.

(Better relationship with colleagues related to extended telework) I feel a stronger bond with my colleagues due to the extended homework because of the corona crisis.

(Better stress management related to extended telework) I experience less work-related stress due to the extended homework because of the corona crisis.

(Better burnout prevention related to extended telework) I think the extended homework caused by the corona crisis is reducing my chances of burnout in the near future.

(Higher work concentration related to extended telework) I experience better concentration at work due to the extended homework because of the corona crisis.

Perceived impact of the COVID-19 crisis on self-view of telework and digital meetings

The following statements deal with the extent to which (i) the current corona crisis has changed your view of telework and digital conferencing and (ii) you think that telework and digital conferencing in general in our country will be boosted by the current corona crisis. Please indicate the extent to which you agree with the statements, on a scale from ‘completely disagree’ (1) to ‘completely agree’ (5).

(More positive self-view of telework) Because of the current corona crisis, I now look more positively on telework.

(Hope for more telework in the future) Because of the current corona crisis, I hope to be able to do more telework in the future.

(Believe in overall more telework in country in future) Because of the current corona crisis, much more telework will be done in our country in the future.

(More positive self-view on digital meetings) Because of the current corona crisis, I now look more positively on digital meetings.

(Hope for more digital meetings in the future) Because of the current corona crisis, I hope that in the future more of my professional meetings will be held digitally.

(Believe in overall more digital meetings in the country in future) Because of the current corona crisis, many more digital meetings will be held in our country in the future.

Appendix B

Additional tables

See Table 5

Footnotes

We, however, advise caution when interpreting sector differences for ‘creative’, ‘agriculture and horticulture’ and ‘maintenance’ because these levels of the sector-variable cover fairly modest shares of the sample—which is not surprising given the many distinct sectors that make up the Flemish labour market.

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Hinchliffe, E.: 14% of women considered quitting their jobs because of the coronavirus pandemic. Fortune. https://fortune.com/2020/04/23/coronavirus-women-should-i-quit-my-job-covid-19-childcare/ (2020). Accessed 27 April 2020

- 2.Kelly, J.: How the coronavirus outbreak will change careers and lives for the foreseeable future. Forbes. https://www.forbes.com/sites/jackkelly/2020/04/09/the-aftermath-of-covid-19-will-cause-alarming-changes-to-our-careers-and-lives/ (2020). Accessed 27 April 2020

- 3.Makortoff, K.: Workers without degrees hardest hit by Covid-19 crisis – study. The Guardian. http://www.theguardian.com/business/2020/apr/20/uk-workers-without-degrees-face-deeper-job-insecurity-amid-coronavirus-pandemic (2020). Accessed 27 April 2020