Abstract

Objectives:

To quantify the rate of readmission from inpatient rehabilitation facilities (IRFs) to acute care hospitals (ACHs) during the first 30 days of rehabilitation stay. To measure variation in 30-day readmission rate across IRFs, and the extent that patient and facility characteristics contribute to this variation.

Design:

Retrospective analysis of an administrative database.

Setting and Participants:

Adult IRF discharges from 944 US IRFs captured in the Uniform Data System for Medical Rehabilitation database between October 1, 2015 and December 31, 2017.

Methods:

Multilevel logistic regression was used to calculate adjusted rates of readmission within 30 days of IRF admission and examine variation in IRF readmission rates, using patient and facility-level variables as predictors.

Results:

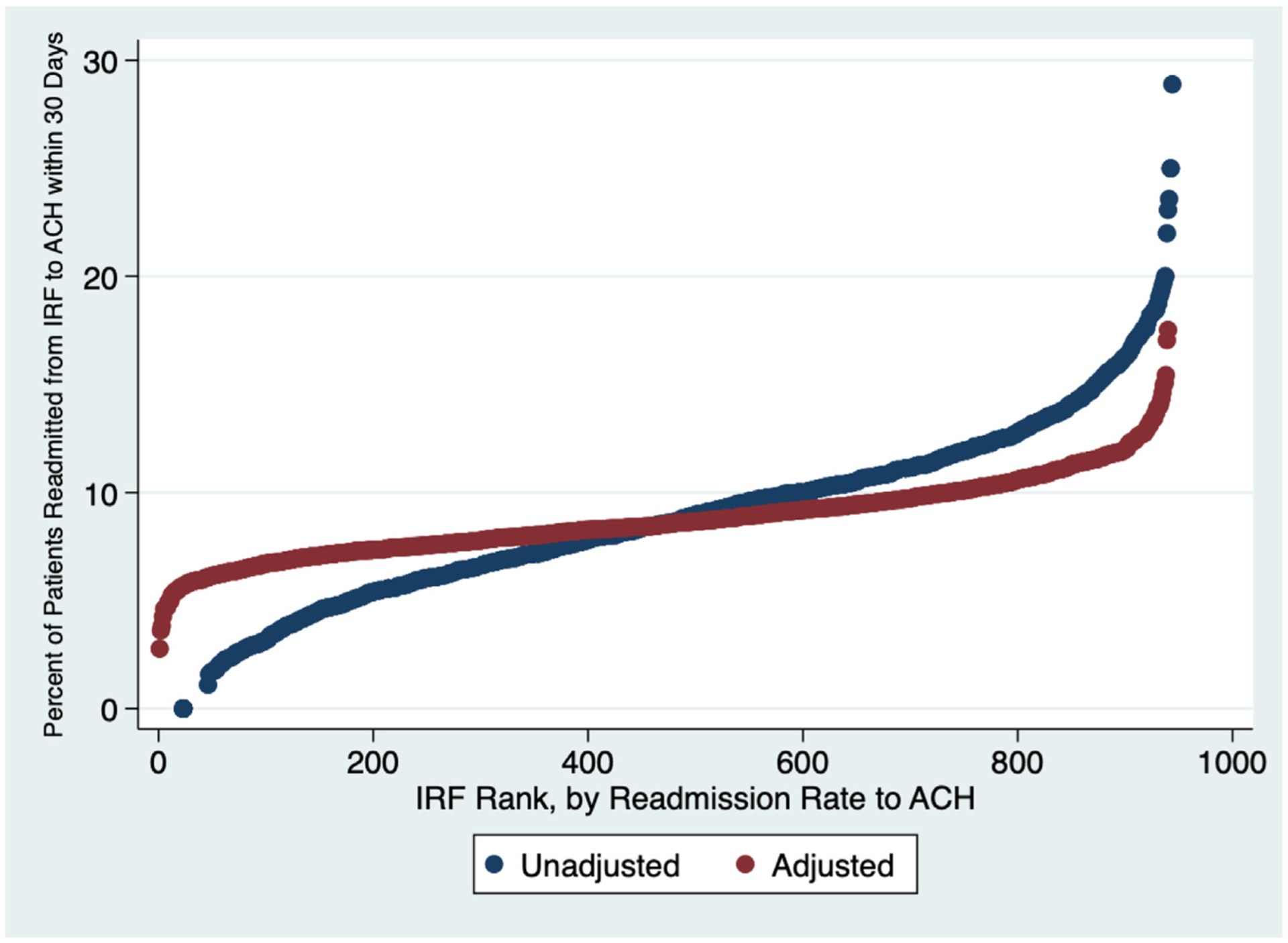

There were a total of 104,303 ACH readmissions out of a total of 1,102,785 IRFs discharges. The range of 30-day readmission rates to ACHs was 0.0%–28.9% (mean = 8.7%, standard deviation = 4.4%). The adjusted readmission rate variation narrowed to 2.8%–17.5% (mean = 8.7%, standard deviation = 1.8%). Twelve patient-level and 3 facility-level factors were significantly associated with 30-day readmission from IRF to ACH. A total of 82.4% of the variance in 30-day readmission rate was attributable to the model predictors.

Conclusions and Implications:

Fifteen patient and facility factors were significantly associated with 30-day readmission from IRF to ACH and explained the majority of readmission variance. Most of these factors are nonmodifiable from the IRF perspective. These findings highlight that adjusting for these factors is important when comparing readmission rates between IRFs.

Keywords: Post-acute care, patient readmission, hospital, rehabilitation

Inpatient rehabilitation facilities (IRFs) account for over 500,000 acute care hospital (ACH) discharge dispositions on an annual basis.1 Patients are required to meet a level of functional impairment and medical stability before they are approved for admission to an IRF.2,3 Despite this, medical complications commonly occur after discharge to IRF and approximately 10% of patients will require a readmission from the IRF to an ACH for further medical care within 30 days.4 These transfers of care can place patients at risk for service duplication, medical errors and adverse events.5,6 From the IRF perspective, readmissions to an ACH are an important quality metric because they disrupt a patient’s rehabilitation course and place the patient at risk of losing functional gains achieved during their IRF stay.

Apart from impacting the patient directly, readmissions also result in substantial financial cost to the health care system. According to the Nationwide Readmissions Database in 2016 each hospital readmission costs an estimated $14,400.7 The total financial impact of 30-day hospital readmissions in the United States in 2011 was $41.3 billion.8 Numerous policies aimed at curbing rising health care costs have targeted hospital readmissions as a key area for improving clinical care coordination and achieving potential savings. Beginning in 2013, Medicare began to impose penalties on hospitals for high rates of readmissions for certain highly prevalent diagnoses as part of the Hospital Readmissions Reduction Program. In 2017, these penalties imposed by Medicare cost hospitals more than $500 million.9 Motivated by the risk of payment reduction and the negative impact on reputation, hospitals have a strong incentive to reduce readmissions.

Among the strategies implemented toward the goal of readmission reduction, hospitals have attempted to increase patient education, multidisciplinary team care, and coordination of post-acute services.10 However, despite modest progress, readmission rates remain high. According to the 2019 US Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality statistical brief, all-cause 30-day readmissions only decreased from 14.2% in 2010 to 13.9% in 2016.7 Several studies have analyzed causes for these readmissions, and have concluded that a large percentage of readmissions are either unavoidable or caused by nonmodifiable patient and facility characteristics.11,12 However, no studies have provided a national assessment of readmission variability from IRFs across the wide spectrum of common rehabilitation impairment diagnoses.

Therefore, the purpose of this study was (1) to quantify readmissions from US IRFs to ACHs during the first 30 days of the rehabilitation admission across a wide array of common rehabilitation impairment diagnoses; (2) to measure the variation in readmission rates between IRFs; and (3) to quantify the extent that patient and facility characteristics account for this variation.

Methods

Study Design

This study was a retrospective review of administrative data.

Data Source

Data was obtained from the Uniform Data System for Medical Rehabilitation (UDSMR). The UDSMR database includes demographic and medical data, as well as information regarding facility characteristics, collected from the IRF-Patient Assessment Instrument (IRF-PAI) from IRFs in the United States.13 The UDSMR includes approximately 70% of US IRFs. The IRF-PAI is an assessment instrument required for Medicare payments that is widely used by IRF providers for quality measures.14

Facilities

All US IRFs within the UDSMR database with at least 60 total patient discharges between the period of October 1, 2015 and December 31, 2017 were included in this study. The minimum criteria of 60 discharges during the selected time period was chosen based on similar criteria in prior work15 and to exclude very low volume facilities.

Study Population

IRF discharges of adult patients age 18 years or older were included in this study. Sixteen diagnosis impairment groups (Table 1) were included in this study, as defined by the IRF-PAI manual.16 The only IRF-PAI impairment group not included in this study was the developmental disability impairment group because of small size (~0.001% of the cohort).

Table 1.

Study Population by Impairment Diagnosis and Discharge Status

| Impairment Diagnosis | Readmitted to ACHs from IRF within 30 d, n (% of Impairment Group) |

All Other Discharges from IRF, n (% of Impairment Group) |

Total (% of Total IRF Discharges) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Medically complex conditions | 1066 (13.6) | 6759 (86.4) | 7825 (0.7) |

| Pulmonary disorders | 2114 (12.9) | 14,250 (87.1) | 16,364 (1.5) |

| Cardiac disorders | 6412 (12.5) | 44,711 (87.5) | 51,123 (4.6) |

| Debility | 11,468 (11.9) | 84,950 (88.1) | 96,418 (8.7) |

| Brain dysfunction | 14,077 (11.4) | 109,828 (88.6) | 123,905 (11.2) |

| Amputation | 3917 (11.5) | 30,040 (88.5) | 33,957 (3.1) |

| Neurologic conditions | 16,494 (11.3) | 128,891 (88.7) | 145,385 (13.2) |

| Other disabling impairments | 1144 (11.0) | 9249 (89.0) | 10,393 (0.9) |

| Spinal cord dysfunction | 6692 (10.3) | 58,507 (89.7) | 65,199 (5.9) |

| Burns | 149 (9.7) | 1392 (90.3) | 1541 (0.1) |

| Stroke | 23,275 (9.0) | 236,207 (91.0) | 259,482 (23.5) |

| Congenital deformities | 33 (8.8) | 342 (91.2) | 375 (0.0003) |

| Major multiple trauma | 2612 (8.0) | 30,190 (92.0) | 32,802 (3.0) |

| Arthritis | 347 (7.4) | 4332 (92.6) | 4679 (0.4) |

| Pain syndromes | 297 (7.4) | 3712 (92.6) | 4009 (0.4) |

| Orthopedic conditions | 14,206 (5.7) | 235,122 (94.3) | 249,328 (22.6) |

| Total | 104,303 (9.5) | 998,482 (90.5) | 1,102,785 (100.0) |

Study Variables

Based on similar prior work, patient and facility characteristics available in the UDSMR database that were thought to have a potential effect on risk of readmission from IRF to ACH within the first 30 days of rehabilitation stay were included as study variables.15,17–19

Patient Characteristics

Patient characteristics included sex, age, duration of impairment (days between impairment onset and IRF admission), race/ethnicity (Caucasian, African American, Latino/Hispanic, Asian, or other, which included no race, multiracial, and other race), marital status (married, not married), living status (living alone, living with others), primary payer source (Medicare, Medicaid, commercial insurance, unreimbursed, worker’s compensation, or other), presence of dysphagia or pneumonia on admission, presence of other comorbidities (as measured by the Elixhauser Comorbidity Index20), weekend admission status (defined as admission to the IRF on a Friday, Saturday, or Sunday21), and admission cognitive and motor functional independence measure (FIM) scores.16 The FIM is a validated instrument that measures function using 18 items subcategorized into motor (13 items) and cognitive (5 items) domains.22 It was developed for tracking rehabilitation outcomes and was subsequently incorporated into the IRF-PAI for use in Medicare’s payment system for IRFs. Age, duration of impairment, Elixhauser Comorbidity Index, and motor and cognitive FIM were treated as quantitative variables. All other variables were treated as categorical variables.

Facility Characteristics

Facility type was defined as either freestanding or within an ACH. Similar to prior studies, geographic location was divided by Center for Medicare and Medicaid Services regions designation as follows: Eastern (regions I-IV), Central (regions V-VIII), and Western (regions IX and X).15 A facility was consider accredited by the Commission on Accreditation of Rehabilitation Facilities (CARF) if it received accreditation at any time over the study period. Facility size was defined by the number of operating beds. Other examined facility characteristics included mean admission cognitive and motor FIM (defined as mean admission score of all patients at a given IRF) and mean duration of impairment (defined as mean number of days from impairment onset to IRF admission at a given IRF).

Outcome Measures

The primary outcome was readmission from IRF to an ACH within 30 days of IRF admission. This outcome was compared with all other discharges from the IRF during the study period, including discharges to ACHs outside of the initial 30-day IRF stay and discharges to home or to other post-acute care facilities (such as skilled nursing facilities) at any time during the study period.

Statistical Analysis

Stata v 16.1 (Stata Statistical Software: Release 16; StataCorp LLC, College Station, TX, USA) was used to complete the statistical analyses. Patient and facility characteristics were compared between 30-day ACH readmissions and all other discharges using 2-sample t-tests for quantitative variables and χ2 tests for categorical variables. An adjusted multilevel logistic regression model was built to model rate of 30-day readmission from IRF to ACH. All patient and facility characteristics described above that were statistically significant model predictors of 30-day readmission to ACH were included in the final model. The relationships between patient and facility variables and the outcome of 30-day readmission were assessed graphically for potential nonlinear relationships, and quadratic and piece-wise treatment of variables was used when appropriate. The final model was then used to calculate adjusted rates of 30-day readmission to ACH for the study IRFs. IRF rank (by readmission rate) vs 30-day readmission rate was plotted for the raw (unadjusted) data and the modeled (adjusted) data. The variance of readmission rates was calculated for the unadjusted (v1) and adjusted (v2) distributions then the percent of variance attributed to the model variables was calculated as [1-(v2/v1)] × 100. For all statistical tests, a P value of less than .05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

A total of 1,102,785 discharges from 944 IRFs met inclusion criteria for this study. Data from 12 IRFs were not included due to the facilities having fewer than 60 discharges during the study period. Of the 16 impairment groups, stroke was most common (23.5%), followed by orthopedic conditions (22.6%), and neurologic conditions (13.2%, Table 1). A total of 104,303 (9.5%) of all discharges from the IRFs were readmissions to ACHs within 30 days. The highest 30-day readmission rates to ACHs occurred among the medically complex group (13.6%), whereas the lowest rates occurred among orthopedic conditions (5.7%).

Patients readmitted within 30 days were older, more likely to be male, have lower admission FIM cognitive and motor scores, have more comorbid medical conditions, and be admitted over the weekend compared with all other IRF discharges. Thirty-day readmissions had the following facility factors compared with all other discharges: larger facility, freestanding status, and less CARF accreditation (Table 2).

Table 2.

Patient and Facility Characteristics of Discharge Groups

| Readmitted to ACHs from IRF within 30 d | All Other Discharges from IRF | P Value | All Discharges from IRF | Missing Data, n (%) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Patient characteristics | |||||

| Age, mean y (SD) | 69.2 (14.5) | 68.7 (15.2) | <.001 | 68.8 (15.1) | 0 (0.0) |

| Male, n (%) | 56,608 (54.3) | 481,840 (48.3) | <.001 | 538,448 (48.8) | 207 (0.02) |

| Race/ethnicity, n (%) | <.001 | 33,854 (3.1) | |||

| Caucasian | 78,967 (77.9) | 761,337 (78.7) | 840,304 (78.6) | ||

| African American | 13,616 (13.4) | 121,341 (12.5) | 134,957 (12.6) | ||

| Latino/Hispanic | 5874 (5.8) | 56,120 (5.8) | 61,994 (5.8) | ||

| Asian | 1725 (1.7) | 18,175 (1.9) | 19,900 (1.9) | ||

| Other | 1138 (1.1) | 10,638 (1.1) | 11,776 (1.1) | ||

| Married, n (%) | 51,267 (50.6) | 459,576 (47.4) | <.001 | 510,843 (47.7) | 32,107 (2.9) |

| Living alone, n (%) | 24,958 (24.3) | 269,440 (27.3) | <.001 | 294,398 (27.0) | 14,189 (1.3) |

| Primary payer source, n (%) | <.001 | 24,041 (2.2) | |||

| Medicare | 76,755 (75.2) | 720,889 (73.8) | 797,644 (73.9) | ||

| Medicaid | 6271 (6.1) | 62,419 (6.4) | 68,690 (6.4) | ||

| Commercial | 15,379 (15.1) | 148,336 (15.2) | 163,715 (15.2) | ||

| Unreimbursed | 1099 (1.1) | 13,599 (1.4) | 14,698 (1.4) | ||

| Worker’s compensation | 530 (0.5) | 8613 (0.9) | 9143 (0.8) | ||

| Other | 2019 (2.0) | 22,835 (2.3) | 24,854 (2.3) | ||

| Duration of impairment, mean d (SD) | 14.1 (21.3) | 11.0 (20.8) | <.001 | 11.3 (20.9) | 22,982 (2.1) |

| FIM cognitive admission, mean (SD) | 20.3 (7.7) | 22.5 (7.1) | <.001 | 22.3 (7.2) | 0 (0.0) |

| FIM motor admission, mean (SD) | 30.4 (11.8) | 37.1 (12.6) | <.001 | 36.5 (12.7) | 0 (0.0) |

| Elixhauser comorbidity Index, mean (SD) | 7.8 (7.6) | 5.7 (7.1) | <.001 | 5.9 (7.2) | 0 (0.0) |

| Dysphagia, n (%) | 22,458 (21.5) | 162,160 (16.2) | <.001 | 184,618 (16.7) | 0 (0.0) |

| Pneumonia, n (%) | 12,264 (11.8) | 77,888 (7.8) | <.001 | 90,152 (8.2) | 0 (0.0) |

| Admitted Friday–Sunday, n (%) | 33,305 (31.9) | 314,182 (31.5) | .002 | 347,487 (31.5) | 0 (0.0) |

| IRF characteristics | |||||

| Operating beds, mean (SD) | 53 (37) | 50 (35) | <.001 | 51 (35) | 255 (0.02) |

| Facility type, n (%) | <.001 | 0 (0.0) | |||

| Freestanding | 55,857 (53.6) | 490,208 (49.1) | 546,065 (49.5) | ||

| Within ACH | 48,446 (46.4) | 508,274 (50.9) | 556,720 (50.5) | ||

| Facility region, n (%) | <.001 | 0 (0.0) | |||

| East | 51,626 (49.5) | 463,780 (46.4) | 515,406 (46.7) | ||

| Central | 40,985 (39.3) | 411,744 (41.2) | 452,729 (41.1) | ||

| West | 11,692 (11.2) | 122,958 (12.3) | 134,650 (12.2) | ||

| CARF accredited, n (%) | 33,032 (31.7) | 331,207 (33.2) | <.001 | 364,239 (33.0) | 0 (0.0) |

SD, standard deviation.

In the final multilevel logistic regression model, 12 patient-level and 3 facility-level factors were significantly associated with 30-day readmission from IRF to ACH. Odds of 30-day readmission rate to ACH was greater for patients who were male, married, had more comorbidities, and who were admitted on the weekend. Odds of 30-day readmission to ACH was greater for freestanding hospitals and lower facility mean admission motor FIM score (Table 3). The following were not included in the final logistic regression model, as they were not found to be statistically significant predictors: living status, primary payer, geographic region, CARF accreditation, and facility size.

Table 3.

Multilevel Logistic Regression Model Examining Patient and Facility Characteristics Associated with 30-Day Readmission to Acute Care Hospitals

| Odds Ratio | Standard Error | P Value | 95% Confidence Interval | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Patient characteristics | ||||

| Age | 0.99849 | 0.00027 | <.001 | 0.99796–0.99902 |

| Female | 0.87515 | 0.00640 | <.001 | 0.86270–0.88778 |

| Race/ethnicity* | ||||

| African American | 1.02137 | 0.01143 | .059 | 0.99922–1.04402 |

| Latino/Hispanic | 0.97522 | 0.01622 | .131 | 0.94395–1.00753 |

| Asian | 0.93097 | 0.02592 | .010 | 0.88153–0.98319 |

| Other | 0.98559 | 0.03369 | .671 | 0.92173–1.05388 |

| Elixhauser comorbidity index | 1.02454 | 0.00051 | <.001 | 1.02354–1.02554 |

| Married | 1.05348 | 0.00764 | <.001 | 1.03863–1.06856 |

| Dysphagia | 0.86300 | 0.00864 | <.001 | 0.84624–0.88009 |

| Pneumonia | 1.15869 | 0.01317 | <.001 | 1.13316–1.18480 |

| Days since impairment onset, ≤10 d | 1 (omitted due to collinearity) | |||

| Days since impairment onset, 10–190 d | 1.01779 | 0.00047 | <.001 | 1.01687–1.01872 |

| Days since impairment onset, 10–190 d, squared | 0.99987 | 4.12e–06 | <.001 | 0.99987–0.99988 |

| Days since impairment onset, ≥190 d | 1.00637 | 0.00093 | <.001 | 1.00455–1.00820 |

| Admission motor FIM | 0.95560 | 0.00037 | <.001 | 0.95487–0.95632 |

| Admission motor FIM, squared | 0.99986 | 0.00002 | <.001 | 0.99982–0.99991 |

| Admission cognitive FIM | 0.99619 | 0.00071 | <.001 | 0.99479–0.99759 |

| Admission cognitive FIM, squared | 1.00077 | 0.00006 | <.001 | 1.00065–1.00089 |

| Admitted Friday–Sunday | 1.03570 | 0.00776 | <.001 | 1.02060–1.05102 |

| Impairment group* | ||||

| Brain dysfunction | 1.37499 | 0.02753 | <.001 | 1.32208–1.43002 |

| Neurologic conditions | 1.37909 | 0.02889 | <.001 | 1.32362–1.43689 |

| Spinal cord dysfunction | 1.23158 | 0.02881 | <.001 | 1.17639–1.28937 |

| Amputation | 1.75687 | 0.04580 | <.001 | 1.66936–1.84898 |

| Arthritis | 1.12919 | 0.07256 | .059 | 0.99556–1.28076 |

| Pain syndromes | 1.23522 | 0.08796 | .003 | 1.07430–1.42023 |

| Orthopedic conditions | 0.87141 | 0.01776 | <.001 | 0.83730–0.90692 |

| Cardiac disorders | 2.04617 | 0.04859 | <.001 | 1.95312–2.14366 |

| Pulmonary disorders | 2.09954 | 0.06810 | <.001 | 1.97022–2.23735 |

| Burns | 1.12702 | 0.11266 | .232 | 0.92649–1.37095 |

| Congenital deformities | 0.72475 | 0.18602 | .210 | 0.43825–1.19857 |

| Other disabling impairments | 1.72285 | 0.07060 | <.001 | 1.58988–1.86693 |

| Major multiple trauma | 0.95384 | 0.02907 | .121 | 0.89854–1.01254 |

| Debility | 1.70522 | 0.03621 | <.001 | 1.63571–1.77769 |

| Medically complex conditions | 1.99545 | 0.09067 | <.001 | 1.82542–2.18131 |

| Facility characteristics | ||||

| Freestanding hospital | 1.14593 | 0.01528 | <.001 | 1.11637–1.17628 |

| Mean admission motor FIM | 0.98078 | 0.00163 | <.001 | 0.97759–0.98399 |

| Mean admission cognitive FIM | 1.00619 | 0.00273 | .023 | 1.00084–1.01156 |

| Mean days since impairment | 1.00199 | 0.00125 | .111 | 0.99954–1.00444 |

All variables were treated as linear predictors except admission motor FIM, admission cognitive FIM, which were treated as quadratic variables, and days since impairment onset, which was treated as a piece-wise variable with linear and quadratic components, based on fit.

Harrell C statistic for final model: 0.71.

For race, Caucasian was set as the reference group (odds ratio = 1). For impairment group, stroke was set as the reference group (odds ratio = 1).

Across the studied 944 IRF facilities, the range of 30-day readmission rates to ACHs was 0.0%–28.9% (mean = 8.7%, standard deviation = 4.4%). The adjusted readmission rate variation narrowed to 2.8%−17.5% (mean = 8.7%, standard deviation = 1.8%). This is depicted by the flattening of the curve in Figure 1. The model variables accounted for 82.4% of the variance in 30-day readmission rate of the unadjusted sample. Of the study IRFs, 55.0% (n = 519) had adjusted 30-day readmission rates with 95% confidence intervals crossing the mean readmission rate across facilities. A total of 22.0% (n = 208) fell below the mean and 23% (n = 217) were above the mean.

Fig. 1.

Distribution of unadjusted and adjusted 30-day readmission rates to ACHs from IRFs.

Discussion

This retrospective analysis is one of the largest to date examining readmission variation from IRFs to ACHs. It includes patients from a diverse group of rehabilitation impairment diagnoses across all regions of the United States and is not limited to a particular payer population. Thirty-day readmission rates to ACHs were found to vary greatly across the 944 IRFs (0.0%–28.9%). The adjusted readmission rate variation narrowed to 2.8%–17.5%. Ramey et al15 also observed a substantial decrease in readmission rate variation following adjustment for patient and facility characteristics in a smaller cohort of rehabilitation patients with the medically complex impairment diagnosis (from 0%–44.4% to 6.9%–21.9% following adjustment for 9 patient and facility factors). In our larger cohort of multiple IRF impairment diagnoses, significant patient and facility factors accounted for 82.4% of the observed variance in 30-day readmission rates. This is similar in magnitude to prior analyses of general readmissions to ACHs among Medicare patients, in which more than one-half of readmission variability has been attributed to patient and facility characteristics.18,19 It is important to understand the factors that contribute to need for ACH readmission because there are known risks of transfers-of-care (provider discontinuity, medication errors, loss of functional gains, etc).6 By understanding which factors are potentially modifiable, quality efforts can be formulated to reduce avoidable transfers and readmissions from IRFs.

In this study, a number of patient characteristics were found to impact risk of 30-day readmission from IRFs to ACHs. Most of these, such as impairment diagnosis, functional status on admission, duration of impairment, medical comorbidities, and demographic factors, are nonmodifiable factors from the standpoint of the IRF. This study agrees with multiple prior works that have shown association of worse mobility at IRF admission with increased risk of 30-day acute hospital readmission.23–25 Kumar et al found that in the Medicare stroke population greater duration of physical therapy received at the ACH prior to discharge correlated with lower rate of 30-day hospital readmission.26 These findings may reflect more than just correlation, as there is some data to suggest that early hospital-based mobility interventions in the ACH setting can reduce readmissions.27,28 Early hospital-based therapies may have a protective role against hospital readmission by optimizing predischarge mobility and functional status. Other significant modifiable factors in this study, such as day of admission, could also be a target for hospital quality improvement efforts. Echoing the findings of Shih et al,21 in this cohort weekend IRF admissions were at higher risk for 30-day readmission to ACH. A reasonable risk-reduction strategy could be to avoid weekend admissions for patient with other high-risk factors.

Among the examined facility factors, CARF accreditation, arguably the only modifiable facility factor examined in this study, was not found to be a statistically significant predictor of risk of 30-day readmission to ACH in the final model. Although CARF accreditation is not required, CARF is the industry gold standard and gaining certification requires display of strict quality standards and performance improvement processes by the institution.29 Although one might hypothesize that accreditation might reduce risk of 30-day readmission to ACH, this was not observed in this study cohort. The facility characteristics that did significantly influence risk for 30-day readmission (freestanding hospital status, mean facility admission motor and cognitive FIM, and mean duration of impairment on admission) are nonmodifiable from the standpoint of the IRF. Higher readmission rates observed for freestanding IRFs vs in-hospital IRFs may reflect the decreased access to resources such as diagnostic tests and specialized physicians at freestanding IRFs. The fact that these factors are largely outside the control of the IRF highlights the importance of correcting for these factors if 30-day readmission to ACH is used as a quality metric to compare IRF facilities.

Although this study specifically examined IRFs, it is important to note that in the United States skilled nursing facilities (SNFs) are an even more common discharge destination from ACHs.30 The 2 have a number of differences, which may influence readmission risk. While patients discharged to IRFs must be able to tolerate and benefit from 3 hours of rehabilitative therapy 5 days a week, this is not required for discharge to SNFs. From a staffing standpoint, IRFs are required to have 24-hour nursing availability and rehabilitation physician-led interdisciplinary treatment, with least ×3 weekly in-person physician visits. In contrast, SNFs are not necessarily required to have on-site nursing around the clock, and services are not necessarily supervised by a rehabilitation physician. Because of possible need for greater staffing and resources, patients who require more complex nursing care (such as patients with ulcers, dysphagia, or incontinence) or more frequent laboratory monitoring may be more likely to go from ACH to IRFs than SNFs.31 There is also some difference in patient age between IRFs and SNFs, reflecting the difference in common diagnoses; generally, more traumatic diagnoses are treated at IRF (such as spinal cord injury, traumatic brain injury, orthopedic trauma), which translates to a younger population than that seen at SNFs. An additional difference is that length of stay is generally shorter in IRFs than SNFs; per a Medicare Payment Advisory Commission (MedPAC) analysis, average length of stay for stroke was 15 vs 25 days at IRFs vs SNFs, and for hip/femur orthopedic procedures was 14 vs 32 days.31 This may be partly influenced by different reimbursement systems. While SNFs are paid by Medicare on a per day basis, IRFs receive a bundled “per discharge” payment based on the patient’s rehabilitation diagnosis and comorbidities.30 Furthermore, a patient copay begins at day 21 of SNF stay for Medicare patients. In terms of ACH readmission rates, unadjusted 30-day ACH readmission rates tend to be higher for SNFs than for IRFs (15.3% vs 11.1% for stroke, 11.3% vs 8.4% for hip and femur orthopedic procedures).31 Possible drivers of these higher readmission rates may be greater comorbidities in the SNF population,30 or decreased access to physicians and diagnostic testing (laboratories, imaging, etc) at SNFs compared with IRFs.

Understanding the risk factors for increased readmission rates from the IRF setting has critically important implications for performance measurement and quality benchmarking for IRF providers and health systems more broadly. Starting in 2016, 30-day hospital readmissions for the Medicare population began to be reported publicly on the IRF Compare website for all federally licensed IRFs.32 More recently, US News and World Report and Newsweek have proposed incorporating 30-day hospital readmissions rates from the IRF Compare site into its rankings methodologies to guide consumer decision-making.33,34 Furthermore, the MedPAC has highlighted 30-day readmissions for inclusion in a proposed value-based incentive program for providers across the post-acute care spectrum, including IRFs.35

Despite expected trends toward public reporting of performance metrics,36 such reporting efforts have proved controversial and underwhelming in the past.37–39 Standardized reporting methods and risk-adjustment of outcomes are consistently recommended as measures that can help increase provider acceptance and broad credibility to both consumers and providers in public reporting frameworks.40 Given the heterogeneity of IRF populations nationally, it will be crucial for IRF providers and consumers to understand the facility-based and patient-based risk factors that may contribute to readmissions as an outcome.

This study has a several limitations. One limitation is that this study only captures patients directly discharged from IRFs to ACHs within 30 days. It does not capture those who are discharged to the community, then readmitted to an ACH within 30 days of initial acute care discharge. This is another important population from the IRF standpoint that has been examined by previous investigators.17,41 In addition, this dataset does not distinguish between planned and unplanned ACH readmissions. Nor does it include detailed characteristics about the medical or rehabilitation treatments received by patients or examine readmission risk of individual medical comorbidities. On the other hand, medical comorbidities may not always correlate with functional status, which may be a stronger predictor of readmission risk. It also lacks some detailed information about the IRFs and ACHs (such as overall ACH size). Furthermore, while the UDSMR database captures the majority of US IRFs, it is not comprehensive, as participation in the UDSMR database is voluntary. Therefore, we are unable to know whether results from this subset of IRFs are fully generalizable to all US IRFs. Finally, because the UDSMR is a deidentified dataset, the analysis is unable to identify or correct for multiple readmissions of the same patient (an individual may be represented more than once in the dataset for separate readmission events). For this reason, descriptive statistics describe readmissions rather than patients in this analysis. Despite these limitations, this is one of the largest studies to-date examining variations in 30-day readmission to ACH from IRF among a diverse population from a geographic, medical, and payer standpoint. Therefore, it contributes to understanding the magnitude that patient and facility factors explain the observed variation across the US in readmissions from IRFs.

Conclusions and Implications

Large variation in rates of 30-day readmission to ACHs was observed in this nationwide sample of IRFs. Fifteen patient and facility factors were significantly associated with 30-day readmission from IRF to ACH and explained the majority of readmission variance. Most of these factors are nonmodifiable from the IRF perspective. This highlights that reporting of unadjusted readmission rates may be misleading, and that adjusting for these patient and facility factors is important when comparing readmission rates between facilities. Future research should continue to examine factors that contribute to variability across IRF facilities to guide quality improvement efforts and decrease potentially avoidable transfers-of-care.

Acknowledgments

The contents of this manuscript were developed under a grant from the National Institute on Disability, Independent Living, and Rehabilitation Research (NIDILRR grant numbers 90DPBU0001, 90DPTB0011, 90SI5021). NIDILRR is a Center within the Administration for Community Living (ACL), Department of Health and Human Services (HHS). The contents of this manuscript do not necessarily represent the policy of NIDILRR, ACL, HHS, and you should not assume endorsement by the Federal Government.

Footnotes

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- 1.Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality. A federal government website. Available at: https://www.hcup-us.ahrq.gov/reports/statbriefs/sb205-Hospital-Discharge-Postacute-Care.pdf. Accessed September 27, 2020.

- 2.Department of Health and Human Services. Inpatient Rehabilitation Therapy Services: Complying with Documentation Requirements. Available at: https://www.cms.gov/outreach-and-education/medicare-learning-network-mln/mlnproducts/downloads/inpatient_rehab_fact_sheet_icn905643.pdf. Accessed August 22, 2020.

- 3.Fu JB, Bianty JR, Wu J, et al. An analysis of inpatient rehabilitation approval among private insurance carriers at a cancer center. PMR 2016;8:635–639. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Shih SL, Zafonte R, Bates DW, et al. Functional status outperforms comorbidities as a predictor of 30-day acute care readmissions in the inpatient rehabilitation population. J Am Med Dir Assoc 2016;17:921–926. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Midlöv P, Bergkvist A, Bondesson A, et al. Medication errors when transferring elderly patients between primary health care and hospital care. Pharm World Sci 2005;27:116–120. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Halasyamani L, Kripalani S, Coleman E, et al. Transition of care for hospitalized elderly patientsddevelopment of a discharge checklist for hospitalists. J Hosp Med 2006;1:354–360. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality. A federal government website. Available at: https://www.hcup-us.ahrq.gov/reports/statbriefs/sb248-Hospital-Readmissions-2010-2016.jsp. Accessed September 27, 2020.

- 8.Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality. Statistical Brief #172. Available at: https://www.hcup-us.ahrq.gov/reports/statbriefs/sb172-Conditions-Read-missions-Payer.pdf. Accessed August 22, 2020.

- 9.Rau J New Round of Medicare Readmission Penalties Hits 2,583 Hospitals. Kaiser Health News. Available at: https://khn.org/news/hospital-readmission-penalties-medicare-2583-hospitals/. Accessed August 15, 2020.

- 10.Warchol SJ, Monestime JP, Mayer RW, Chien WW. Strategies to reduce hospital readmission rates in a non-Medicaid-expansion state. Perspect Health Inf Manag 2019;16:1a. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ali AM, Bottle A. The validity of all-cause 30-day readmission rate as a hospital performance metric after primary total hip and knee arthroplasty: A systematic review. J Arthroplasty 2019;34:1831–1836. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.van Walraven C, Jennings A, Forster AJ. A meta-analysis of hospital 30-day avoidable readmission rates. J Eval Clin Pract 2012;18:1211–1218. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.The Uniform Data System for Medical Rehabilitation. About Us. Available at: https://www.udsmr.org/about-us. Accessed July 16, 2020.

- 14.Center for Medicare & Medicaid Services. IRF-PAI and IRF-PAI Manual. Available at: https://www.cms.gov/Medicare/Quality-Initiatives-Patient-Assessment-Instruments/IRF-Quality-Reporting/IRF-PAI-and-IRF-PAI-Manual. Accessed July 16, 2020.

- 15.Ramey L, Goldstein R, Zafonte R, et al. Variation in 30-day readmission rates among medically complex patients at inpatient rehabilitation facilities and contributing factors. J Am Med Dir Assoc 2016;17:730–736. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Center for Medicare & Medicaid Services. The Inpatient Rehabilitation Facility-Patient Assessment Instrument (IRF-PAI) Training Manual. Available at: https://www.cms.gov/Medicare/Medicare-Fee-for-Service-Payment/InpatientRehabFacPPS/Downloads/IRFPAI-manual-2012.pdf. Accessed July 18, 2020.

- 17.Ottenbacher KJ, Karmarkar A, Graham JE, et al. Thirty-day hospital readmission following discharge from postacute rehabilitation in fee-for-service Medicare patients. JAMA 2014;311:604–614. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Singh S, Lin YL, Kuo YF, et al. Variation in the risk of readmission among hospitals: The relative contribution of patient, hospital and inpatient provider characteristics. J Gen Intern Med 2014;29:572–578. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Barnett ML, Hsu J, McWilliams JM. Patient characteristics and differences in hospital readmission rates. JAMA Intern Med 2015;175:1803–1812. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Elixhauser A, Steiner C, Harris DR, Coffey RM. Comorbidity measures for use with administrative data. Med Care 1998;36:8–27. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Shih SL, Flavin M, Goldstein R, et al. Weekend admission to inpatient rehabilitation facilities is associated with transfer to acute care in a nationwide sample of patients with stroke. Am J Phys Med Rehabil 2020;99:1–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Stineman MG, Shea JA, Jette A, et al. The Functional Independence Measure: Tests of scaling assumptions, structure, and reliability across 20 diverse impairment categories. Arch Phys Med Rehabil 1996;77:1101–1108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Fisher SR, Kuo YF, Sharma G, et al. Mobility after hospital discharge as a marker for 30-day readmission. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci 2013;68:805–810. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Slocum C, Gerrard P, Black-Schaffer R, et al. Functional status predicts acute care readmissions from inpatient rehabilitation in the stroke population. PLoS One 2015;10:e0142180. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Soley-Bori M, Soria-Saucedo R, Ryan CM, et al. Functional status and hospital readmissions using the medical expenditure panel survey. J Gen Intern Med 2015;30:965–972. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kumar A, Resnik L, Karmarkar A, et al. Use of hospital-based rehabilitation services and hospital readmission following ischemic Stroke in the United States. Arch Phys Med Rehabil 2019;100:1218–1225. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kim SJ, Lee JH, Han B, et al. Effects of hospital-based physical therapy on hospital discharge outcomes among hospitalized older adults with community-acquired pneumonia and declining physical function. Aging Dis 2015;6:174–179. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Azuh O, Gammon H, Burmeister C, et al. Benefits of early active mobility in the medical intensive care unit: A pilot study. Am J Med 2016;129:866–871.e1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.CARF International. Who We Are. Available at: http://www.carf.org/About/WhoWeAre/. Accessed August 7, 2020.

- 30.MedPAC. Report to the Congress: Medicare and the Health Care Delivery System. Chapter 7: Medicare’s post-acute care: Trends and ways to rationalize payments. Available at: http://medpac.gov/docs/default-source/reports/chapter-7-online-only-appendixes-medicare-s-post-acute-care-trends-and-ways-to-rationalize-payments-.pdf. Accessed February 14, 2021.

- 31.MedPAC. Report to the Congress: Medicare and the Health Care Delivery System. Chapter 6: Site-neutral payments for select conditions treated in inpatient rehabilitation facilities and skilled nursing facilities. Available at: http://www.medpac.gov/docs/default-source/reports/chapter-6-site-neutral-payments-for-select-conditions-treated-in-inpatient-rehabilitation-facilities.pdf. Accessed February 14, 2021.

- 32.Center for Medicare and Medicaid Services. About IRF Compare. Available at: https://www.medicare.gov/inpatientrehabilitationfacilitycompare/#about/theData. Accessed November 2, 2020.

- 33.US News and World Report. New Methodology for Ranking Rehabilitation Hospitals. Available at: https://health.usnews.com/health-news/blogs/second-opinion/articles/2020-01-28/new-methodology-for-ranking-rehabilitation-hospitals. Accessed November 2, 2020.

- 34.Newsweek. Best Physical Rehabilitation Centers. Available at: https://www.newsweek.com/americas-best-physical-rehabilitation-centers-2020. Accessed November 2, 2020.

- 35.Tabor L, Carter C. A value incentive program for post-acute care providers. Available at: http://medpac.gov/docs/default-source/default-document-library/pac-vip-sept-2019-final.pdf?sfvrsn=0. Accessed November 2, 2020.

- 36.Sharma K, Metzler I, Chen S, et al. Public reporting of healthcare data: a new frontier in quality improvement. Bull Am Coll Surg 2012;97:6–13. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Chassin MR. Achieving and sustaining improved quality: lessons from New York State and cardiac surgery. Health Aff (Millwood) 2002;21:40–51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Fung CH, Lim YW, Mattke S, et al. Systematic review: the evidence that publishing patient care performance data improves quality of care. Ann Intern Med 2008;148:111–123. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Jha AK, Orav EJ, Epstein AM. Public reporting of discharge planning and rates of readmissions. N Engl J Med 2009;361:2637–2645. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Rothberg MB, Benjamin EM, Lindenauer PK. Public reporting of hospital quality: recommendations to benefit patients and hospitals. J Hosp Med 2009; 4:541–545. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Middleton A, Graham JE, Lin YL, et al. Motor and cognitive functional status are associated with 30-day unplanned rehospitalization following post-acute care in Medicare fee-for-service beneficiaries. J Gen Intern Med 2016;31: 1427–1434. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]