Abstract

We study the effect of women’s public leadership in times of crisis. We use a regression discontinuity design in close mayoral races between male and female candidates to understand the impact of having a woman as a mayor during the COVID-19 pandemic in Brazil. Female leadership reduced deaths and hospitalizations per 100 thousand inhabitants while increasing enforcement of non-pharmaceutical interventions. These results are not due to measures taken before the pandemic or other observable mayoral characteristics such as education or political preferences. The effects are stronger in municipalities where Brazil’s far-right president, who publicly disavowed the importance of non-pharmaceutical interventions, had a higher vote share in the 2018 election. Overall, our findings provide credible evidence that female leaders outperformed male ones when dealing with a global policy issue. They also showcase that local leaders can counteract policies implemented by populist leaders at the national level.

Keywords: Gender, Politics, Health, COVID-19, Brazil

1. Introduction

It is well established in the literature that political leadership plays a crucial role in shaping social and economic outcomes (Jones and Olken, 2005, Yao and Zhang, 2015). During the COVID-19 pandemic, the response of leaders around the globe in dealing with the crisis varied remarkably (Piscopo, 2020). Moreover, this global health crisis has been particularly intense and persistent in developing countries such as Brazil, Mexico, and India, where national leaders dismissed the severity of the pandemic and failed to enforce measures to contain the spread of the virus. These trying times also brought to media’s attention the fact that countries under the leadership of women outperformed those led by men, as the results obtained by New Zealand, Germany, Taiwan and Bangladesh illustrate (Taub, 2020, Henley, 2020).

While several studies have documented that female empowerment improves social and economic outcomes, the role of female leadership in tackling global policy issues is not yet well understood (Hessami and da Fonseca, 2020). Moreover, to our knowledge, little is known about the role of women as policymakers in times of crisis. Despite the recent effort of numerous scholars, studies comparing COVID-19 responses in countries ruled by women and men have come to inconclusive results (e.g., Garikipati and Kambhampati, 2021, Piscopo, 2020). Using Brazil as a laboratory, this paper studies if municipalities led by women were less affected by the COVID-19 outbreak in 2020. In particular, we address and answer the following questions: Did municipalities governed by women have fewer deaths and hospitalizations due to COVID-19? Did female leaders respond differently to the crisis? If so, which policies they adopted that municipalities ruled by men did not? In which municipalities the importance of women as policymakers during a health crisis was magnified?

Identifying the effects of female leaders on policy outcomes is challenging because of municipality-specific factors that are related both to the presence of female leaders and the outcomes. To avoid biases caused by these factors, we implement a Regression Discontinuity (RD) design focusing on mixed-gender races. This method allows us to identify the effect of electing a female mayor on COVID-19 outcomes by comparing municipalities where a female candidate won against a male one by a narrow margin with the ones where the opposite occurred. To provide complementary evidence on our findings we estimate the effect of electing a female mayor using a dynamic local difference-in-difference approach using quarterly data and compare hospitalizations and deaths caused by Severe Acute Respiratory Infection (SARI) in municipalities with male and female mayors relatively to the figures before the COVID-19 outbreak.

We find that the presence of a female leader in Brazilian Municipalities had a negative, sizable, and significant impact on the number of COVID-19 deaths and hospitalizations per 100 thousand inhabitants. Our results show that electing a woman as a mayor causes a decrease from 46.9 to 51.0 COVID-19 hospitalizations per 100 thousand inhabitants, which represents 30.4 to 33.0 percent of the outcome average among the municipalities that elected a man. Similarly, we document a drop of 21.7 to 25.5 COVID-19 deaths per 100 thousand inhabitants decreases in municipalities that elected a woman, around 37.2 to 43.7 percent of the outcome average among the municipalities that elected a man. We also show that electing a female mayor causes a statistically significant in the number of non-pharmaceutical interventions (NPIs) enforced in the municipality in 2020. In particular, we show that female leaders are more likely to adopt mandatory use of face masks and forbid gatherings. In contrast, we do not find evidence that women increase investment in health care neither before nor after the pandemic outbreak. Finally, we show that these effects are stronger in municipalities where voters are more supportive of Brazilian President Jair Bolsonaro, who openly disavowed vaccines and NPIs during the pandemic. This finding exemplifies the role local leaders can play in counteracting bad policies implemented by populist leaders at the national level.

We perform a series of robustness checks. First, we document very similar point estimates using SARI deaths and hospitalizations as dependent variables, which are less likely to suffer from non-classical measurement error caused by strategic under reporting since they do not depend on a positive COVID-19 test for a diagnosis. Second, our point estimates are very similar using linear and quadratic RD polynomials and different bandwidths.1 Third, our estimates using a local difference-in-difference comparing changes in SARI outcomes before and after the pandemic outbreak in municipalities with males and females mayors provide qualitatively similar results.

Brazil is the ideal setting to understand the role of female leadership during the pandemic for several reasons. First, Brazil was severely hit by the first wave of COVID-19, with considerable variation in deaths and hospitalizations across municipalities (Souza et al., 2020). Second, Brazilian municipalities enjoy considerable autonomy to adopt policies. Finally, Brazil hosts many competitive local elections, providing statistical power to compare outcomes in mixed-gender close races, as previous works have successfully done.2

One possible concern is that mayors’ characteristics that are relevant for policymaking could be driving our results (Alesina et al., 2019). In particular, the fact that female mayors tend to be more educated in Brazilian municipalities could be an issue (Arvate et al., 2017). We show that, in fact, there is a small and non-robust unbalance in both years of education and ideological preferences between female and male leaders. In order to verify if these characteristics are driving our results, we show that our findings do not change after accounting for them in our regressions. This suggests that the difference we document is likely driven by differences in non-observable traits between female and male leaders. We discuss some possible mechanisms in the results section.

Our paper contributes to several strands of the literature. First, we add to the extensive research investigating the role of women as policymakers. Previous work documented how female leadership decreases corruption and improves policy and economic outcomes in developing countries, but does not affect these outcomes in developed nations.3 Closely related to our work, Brollo and Troiano (2016) document that female mayors lead to better prenatal care delivery and are less likely to engage in corruption, and Barbosa (2017) finds that electing a woman as a mayor does not affect educational outcomes.

To the best of our knowledge, the role of women as policymakers in critical times and the political factors that magnify their influence on policy outcomes are not well understood so far. We make three contributions to this literature. First, we provide evidence that electing a female mayor improved health outcomes during a pandemic, showing that female leaders fared better than male ones in dealing with a major global issue. Second, we shed light on the conditions under which female leaders make a difference by showing that they improved outcomes during the pandemic in a context where they had limited influence on health outcomes before the health crisis. Third, we show that the benefits of female leadership are stronger where voters are more aligned with a populist president that denies the severity of the crisis, showing that female empowerment at the local level can counteract bad policies at the national level.

Our findings directly contribute to recent studies analyzing how female leadership affects policies related to COVID-19 and the pandemic severity, which documented mixed results. Piscopo (2020), Aldrich and Lotito (2020) and Windsor et al. (2020) find that countries led by women had similar COVID-19 mortality than those led by men. Abras et al. (2021) document a negative association between COVID-19 outcomes and female leadership attributed to differences in health systems where women rule, not their leadership. In contrast, Garikipati and Kambhampati (2021) show that countries led by women had better results than those led by men and attributes such differences to earlier adoption to NPIs by female leaders. Using across state-level data from the US, Sergent and Stajkovic (2020) show that states led by women had fewer COVID-19 deaths and earlier stay-at-home-orders. We complement this literature by estimating the impacts of female leadership on COVID-19 epidemiological outcomes using within-country data and a method with high internal validity, thus providing credible evidence on how women outshone men as leaders during the pandemic.

Our findings are also related to the literature investigating the broad consequences of female political participation. Beaman et al. (2009) and Iyer et al. (2012) present evidence on the social consequences of political reforms that increased political representation of women in India. While the former finds a weakening in gender stereotypes, the latter finds a backlash in the form of an increase of violence against women. Evidence from the US context shows that extending the franchise to women increased per capita government spending and decreased infant and maternal mortality (Lott and Kenny, 1999, Miller, 2008, Bhalotra et al., 2020). We complement this literature by showing that the importance of women’s descriptive representation becomes especially relevant during a health crisis.

Finally, our paper adds to the literature investigating how attitudes of populist leaders such as Jair Bolsonaro (Brazil) and Donald Trump (United States) affect how citizens deal with the pandemic (Rafkin et al., 2021, Ajzenman et al., 2020, Mariani et al., 2020). By showing that female mayors decreased COVID-19 deaths and hospitalizations more intensively in municipalities where Bolsonaro had more support from voters, we emphasize the role local leaders with distinct policy preferences can play in countering bad policies at the national level.

The decrease in the mortality rates caused by the election of female mayors according to our most conservative estimates has a very large magnitude from a public policy perspective, as it corresponds to the average yearly homicide rate experienced by the municipalities in our sample between 2013 and 2016. If we extrapolate our more conservative estimates on the effect of female leadership on all Brazilian municipalities, one can quantify considerable economic benefits from increasing female representation. Back-of-the-envelope calculations suggest that, all else equal, if Brazil had half of its municipalities led by women, the COVID-19 death toll would have been 14.17% lower, saving around thousand lives. Hence, policies that increase female representation in politics, such as gender quotas on candidates’ lists, generate a double-dividend in moments of crisis: increasing welfare while promoting diversity.4

The paper proceeds as following: Section 2 describes the institutional setting. Section 3 present our data and research design. Section 4 presents our results and Section 5 concludes.

2. Background

In 2018, Brazil elected as president Jair Bolsonaro, a far-right politician. With an authoritarian leadership style, he has emphasized conservative family values and a strong economy during his administration (Barberia and Gómez, 2020). After the COVID-19 outbreak, Bolsonaro’s presidency was marked by the reckless way it dealt with the crisis. The Brazilian federal government refused to follow international recommendations for the adoption of NPIs, declined to establish social distancing measures and to promote the use of facial coverage (Ferigato et al., 2020). He repeatedly criticized governors and mayors for closing businesses, and proposed restricting social isolation measures to the elderly (The Economist, 2020b). He also attended large political gatherings (Marcelino and Slattery, 2020) and publicly undermined science several times during the pandemic, calling COVID-19 “just a sniffle” (The Economist, 2020a), advocating the use of unproven drugs such as Hydroxychloroquine (Londoño and Simões, 2020) and, more recently, doubting vaccines’ safety (Daniels, 2021).

Given the inadequate policy responses to the COVID-19 outbreak, Brazil has become one of the hot spots of the pandemic. By January of 2021, the country registered over thousand deaths by COVID-19, equivalent to more than 10% of global deaths in a country with less than 3% of the worldwide population (Castro et al., 2021). This is reflected in one the highest mortality rates on the planet, which becomes even more salient after controlling for its population’s gender and age composition (Hecksher, 2020). In response to the pressing needs of states and municipalities to enforce NPIs to control the severity of the pandemic, the Brazilian Federal Supreme Court, in April 2020, decided that the federal government could not unilaterally dismiss decisions adopted by local governments to fight the pandemic (Supremo Tribunal Federal, 2020). This provided local governments with both the legal autonomy and policy instruments to mitigate the spread of the disease, mostly through Brazil’s Unified Health System — Sistema Único de Saúde (SUS).

Since the 1988 Brazilian Constitution establishes free health care as a right, SUS targets free universal health coverage, which contrasts with the health systems of most developing countries (Bhalotra et al., 2019). The majority of the population rely on it for medical treatment, as only 28% of the Brazilians have private health insurance (IBGE, 2019). Mayors play an essential role in health policy, managing 20% of the SUS resources (Andrade and Lisboa, 2002). Municipalities usually administrate smaller public health units that complement the supply of services in larger state and federal hospitals. These small units are a relevant supplier of health services in Brazil, as more than 60% of the population use their services (Castro et al., 2019). Moreover, in line with the active role of mayors, health is usually a salient policy issue for voters during municipal elections (Boas et al., 2019).

3. Data and empirical strategy

3.1. Data

Epidemiological outcomes: Our main epidemiological outcomes come from the SIVEP-Gripe system, managed by Brazil’s Ministry of Health — Ministério da Saúde (MS). We combine information from this dataset with census population accounts from Brazil’s National Bureau of Statistics — Instituto Brasileiro de Geografia e Estatística (IBGE) — to compute the number of COVID-19 deaths and hospitalizations per 100 inhabitants at the municipality level, as it is standard in the epidemiology literature.

Policy outcomes: To construct our policy outcomes we use data from three distinct sources. First, we compute health care spending per capita by combining budgetary information from the SICONFI (Brazilian Public Sector Accounting and Tax Information System) managed by Brazil’s National Treasury (STN) with IBGE’s population accounts. Second, we compute the number of hospital beds and ICUs hospital beds per 100 thousand inhabitants combining data from MS’s National Register of Health Establishments (CNES) with IBGE’s population accounts. Finally, we use data that allows us to identify if mayors adopted NPIs during the year of 2020, such as restricting entry in the municipality, limits on social gatherings, closure of non-essential businesses, compulsory use of masks, and reduced public transportation services. This information was obtained through a partnership between the research team from de Souza Santos et al. (2021) and Brazil’s National Confederation of Municipalities. Between May and July, 2020, 72.3% of 5568 mayors and the Federal District’s government were surveyed via phone calls on local NPI policies related to the pandemic.5

Baseline characteristics: To complement our analysis we obtained data on baseline characteristics from several sources. First, we use information from IBGE’s MUNIC and MS’s CNES to compute a set of policy and communication-related control variables at the municipality level before the 2016 election. Second, we compute a series of socioeconomic and demographic controls at the municipality level using the IBGE’s census data. Third, using data about candidates’ characteristics and vote shares from Brazil’s Electoral Court, we compute mayor-level controls such as years of education, age and whether or not the candidate is a health sector worker. Finally, using Power and Rodrigues-Silveira (2019)’s party-level index from the 2016 election, we calculate the municipal ideological score.

Tables A1 and A2 in the appendix present the sources and describe our outcome and control variables respectively. Tables A3 and A4, in turn, present summary statistics for outcome and control variables divided into control and treatment municipalities.

3.2. Regression discontinuity

Identifying the impact of a policymaker’s gender on health outcomes and policy decisions is a challenging task. By simply comparing municipalities with mayors of different genders, we are likely to incur in endogeneity issues since our outcome variables might be correlated with variables that could also influence the mayor’s gender.

In order to measure the causal impact of having a female mayor on health outcomes and NPIs we rely on a sharp regression discontinuity (RD) strategy with the following specification:

| (1) |

where denotes a municipality and denotes a state. is the margin of victory of the winner female mayor candidate in the previous mixed-gender electoral race. is positive if the winner of the mixed-gender election was a female candidate and the second place was a male candidate, and negative if the opposite takes place. The independent variable is an indicator which takes value 1 if our running variable and zero otherwise. Finally, is a state fixed-effects term.6 We estimate our equation assuming that is a flexible polynomial on both sides of the threshold. Following Gelman and Imbens (2019) we estimate only first and second-degree polynomials for the optimal bandwidth calculated using the non-parametric procedure from Calonico et al. (2014). Our coefficient of interest measures the effect of having a female mayor on outcome .

We choose a specification with state fixed-effects as our main one for several reasons. First, since treatment and control municipalities have similar frequency across states, we can increase the efficiency of our estimates without biasing them when adding fixed-effects (Calonico et al., 2019). Second, as governors have autonomy to enforce NPIs, we compare municipalities subject to the same state-level regulation. Third, since Brazil is a large continental country, we decrease the chance of comparing municipalities where the first and second COVID-19 waves started before and after the end of 2020.

3.3. Validity of the RD design

In order to interpret as causal we must satisfy two conditions: (i) our treatment does not affect baseline covariates and (ii) there is no manipulation of the running variable near the threshold. The first is equivalent to saying that our sample must be balanced for treated and untreated units in pre-determined municipality-specific characteristics. In Fig. A1 we present the t-statistics and the standardized values of in Eq. (1) using our baseline covariates as dependent variables.7 We find that all our baseline characteristics are balanced. Detailed results are presented in Table A5 in the appendix.

We also show in Fig. A2 that does not present any bunching near the threshold. This is verified using a McCrary test which yields a -value of 0.30 and, therefore, fails to reject the null of no manipulation in our running variable.8

3.4. Local difference-in-differences

To provide additional evidence we estimate the effect of electing a female mayor on health outcomes using a dynamic local difference-in-difference approach using quarterly data.9 We compare SARI outcomes in municipalities with male or female mayors to the figures in the first quarter of 2020, the last quarter before the outbreak. Using SARI outcomes is important in order to rule out strategic under reporting, since they do not depend on a positive COVID-19 test for diagnosis. It also allow us to monitor the pattern of hospitalizations and infections over time, since these numbers are available for multiple years.

Our estimating sample comprises of municipalities near the discontinuity before and after the pandemic outbreak in the first quarter of 2020. The neighborhood near the cutoff is given by the optimal bandwidth obtained in our RD estimations, in order to assure that treatment and control groups are comparable. Formally, we estimate the following regression model:

| (2) |

where captures municipality fixed-effects and captures state-year-quarter fixed effects. To mirror our baseline RD specification in a dynamic setting, we control for , a year-quarter specific polynomial in the vote-share of female candidates with parameters that vary flexibly for each municipality.

4. Results

COVID-19 deaths and hospitalizations. The first and second columns of Panel A in Table 1 report the RD estimates on, respectively, the number of COVID-19 deaths and hospitalizations per 100 thousand inhabitants using a linear polynomial. Third and fourth columns report the estimates on SARI deaths and hospitalizations, respectively. Panel B repeats the structure of Panel A but using a quadratic polynomial.

Table 1.

Impact of female leadership on COVID-19 deaths and cases — RD estimates.

| COVID-19 deaths | COVID-19 hospitalizations | SARI deaths | SARI hospitalizations | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| per 100k pop. | per 100k pop. | per 100k pop. | per 100k pop. | |

| Panel A: Linear specification | ||||

| RD estimator | −25.526 | −46.9558 | −19.9059 | −48.0531 |

| Robust -value | 0.0014*** | 0.015** | 0.032** | 0.08* |

| Robust conf. int. | [−41.1545, −9.8975] | [−84.6665, −9.2452] | [−38.1193, −1.6925] | [−101.7278, 5.6216] |

| CCT-optimal BW | 9.054 | 8.478 | 9.4189 | 8.5657 |

| Eff. number obs. | 508 | 484 | 524 | 487 |

| Panel B: Quadratic specification | ||||

| RD estimator | −21.7457 | −51.0762 | −20.6654 | −58.6977 |

| Robust -value | 0.015** | 0.02** | 0.04** | 0.056* |

| Robust conf. int. | [−39.2945, −4.1969] | [−94.1926, −7.9597] | [−40.5064, −0.8243] | [−118.8668, 1.4713] |

| CCT-optimal BW | 15.81 | 15.6721 | 15.9106 | 16.7521 |

| Eff. number obs. | 792 | 786 | 797 | 816 |

Notes: This table reports our RD estimates of the effect of female mayors on the number of deaths and hospitalizations by COVID-19 and SARI per hundred thousand inhabitants in 2020 in Brazilian municipalities. Note that COVID-19 numbers are a subset of SARI numbers. Estimation proceeded over the 1222 municipalities in our mixed-gender elections sample. Panel A shows the results for a first-degree polynomial estimation. Panel B shows the results for a second-degree polynomial estimation. Optimal bandwidths following Calonico et al. (2014) were chosen to minimize the mean squared error of the local polynomial RD point estimator. Following that same work, we report robust-bias corrected -values and 95% CIs. All estimates account for state fixed-effects following Eq. (1). Coefficients significantly different from zero at 99% (***), 95% (**) and 90% (*) confidence level.

In the first column we show that municipalities that elected a female mayor experienced 25.52 fewer deaths per 100 thousand inhabitants, an impact that is significant at 1% confidence levels. This corresponds to 43.7 percent of the outcome average among municipalities that elected a male mayor, according to the values in Table A3. In the second column of Panel A, we find a significant difference of 46.95 fewer hospitalizations per 100 thousand inhabitants, which accounts for 30.4 percent of the outcome average among the control municipalities. In the third and fourth columns we estimate the difference in SARI deaths and hospitalizations and document a difference of 19.90 fewer deaths and 48.05 fewer hospitalizations per 100 thousand inhabitants. These differences account for 24.65 percent of the average SARI deaths and 18.47 percent of the average SARI hospitalizations among the control municipalities. In Panel B, we report similar results using a quadratic polynomial specification.

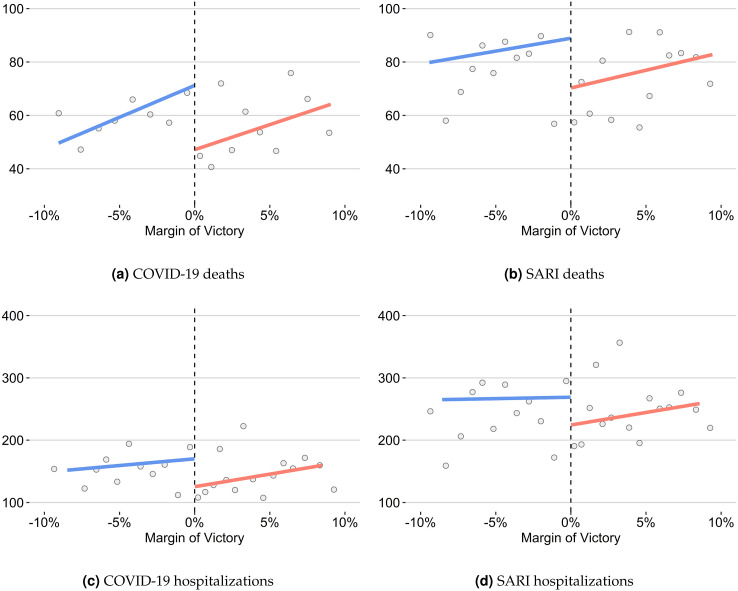

Fig. 1 shows graphically the effects described above. In subfigure (a) we present the RD plot for the impact of female mayors on COVID-19 deaths, displaying a negative difference between the linear fit lines in both sides of the threshold. The same pattern, displaying the point estimates found in Panel A of Table 1, can be seen in subfigures (b), (c) and (d) for, respectively, SARI deaths, COVID-19 hospitalizations and SARI hospitalizations per 100 thousand inhabitants. These effects are robust to different bandwidth lengths, including the CER and MSE optimal bandwidths from Calonico et al. (2014), as we show in Fig. A3 in Appendix.

Fig. 1.

Impact of female leadership on COVID-19 and SARI deaths and hospitalizations per 100,000 inhabitants in 2020.

Notes: This figure shows graphically the effect of female mayors on the number of deaths and hospitalizations by COVID-19 and SARI per hundred thousand inhabitants in 2020 in Brazilian municipalities. Note that COVID-19 numbers are a subset of SARI numbers. Subfigure (a) presents the RD plot for COVID-19 deaths. Subfigure (b) presents the RD plot for SARI deaths. Subfigure (c) presents the RD plot for COVID-19 hospitalizations. Subfigure (d) presents the RD plot for SARI hospitalizations. Plots were generated accordingly to Calonico et al. (2015). We use a linear specification and a uniform kernel. Following Calonico et al. (2014), the optimal bandwidths were chosen to minimize the mean squared error of the local polynomial RD point estimator. All estimates account for state fixed-effects following Eq. (1). For more details on these estimates see Table 1 Panel A.

To rule out the possibility that our results are caused by chance rather than an underlying causal relationship, we reproduce our estimates for different values of the threshold for the victory margin in Fig. A4 in Appendix. If the effect we estimate is indeed related to the presence of a female mayor, we expect to find a negative and significant coefficient only at the true threshold. This is exactly what the figures show: the largest and most precise coefficients are at 0%.

If we take the quotient between our treatment effects on COVID-19 hospitalization and deaths per 100 thousand inhabitants, they imply COVID-19 fatality rates of 50%, which overestimates the actual COVID-19 fatality rates by a considerable amount but are in line with the estimates of 40% documented by the medical literature (de Souza et al., 2021). Such high COVID-19 fatality rates are not surprising in the SIVEP-Gripe data for two reasons. First, our death numbers account for both hospitalized and non-hospitalized patients. Second, in contrast to death figures, our hospitalization numbers account only for patients with a positive COVID-19 test, which likely underestimates the actual case base because of asymptomatic cases and low testing rates in Brazil (Hasell et al., 2020).

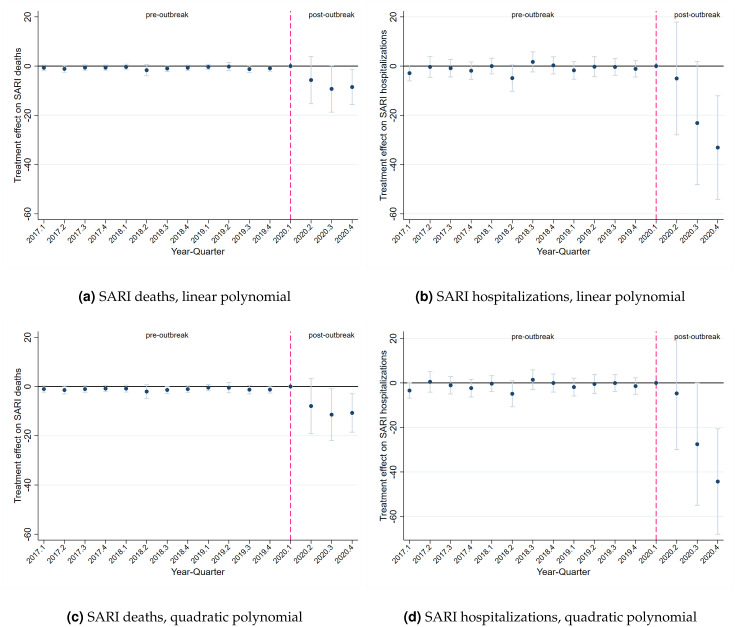

Local DID. To provide complementary evidence on the effect of female mayors on health outcomes during the pandemic, we also estimate local difference-in-differences regressions following Eq. (2). The results are presented in Fig. 2.10 It displays four graphs reporting the effects of electing a female mayor in the 2016 election over the year-quarters between 2017.1–2020.4 using the first quarter of 2020 as the reference period. Each specification uses the sample of the RD specification in the third and fourth columns of Table 1 that has the same outcome and polynomial specification. The results show that the election of a female mayor has no effect on SARI deaths and hospitalizations until the first quarter of 2020, suggesting that differences in health policies before the outbreak are unlikely explain our effects. After the outbreak the effects become negative and significant. More interestingly, they are monotonically increasing overtime, following the pattern of SARI outcomes after the outbreak as documented by previous papers (Ajzenman et al., 2020). This result also motivates the parallel trends hypothesis in our setting, suggesting that SARI outcomes of municipalities that elected male or female mayors in 2016 would evolve similarly in the absence of the pandemic.

Fig. 2.

Impact of female leadership on COVID-19 deaths and cases — Dynamic local DID estimates.

Notes: This figure displays four graphs reporting the effects of electing a female mayor in the 2016 election across the year-quarters between 2017.1–2020.4 and their 90% confidence interval. Treatment effects are estimated using quarterly data from 2017.1 to 2020.4. The local DID regression model has the form where captures municipality fixed-effects and captures state-year-quarter fixed effects. is an indicator variable equal to one when the municipality in state selected a woman as a mayor in 2016. To mirror our baseline RD specification in a dynamic setting, we control for , a year-quarter specific polynomial in the vote-share of female candidates with parameters that vary flexibly for municipalities that elected a man and a woman as a mayor in 2016. Treatment effects are normalized concerning the first quarter of 2020, the last quarter before the COVID-19 outbreak. Each local DID specification uses the sample of the RD baseline estimates with the same outcome and RD polynomial that is reported in Table 1. We cluster standard errors at the municipality level.

Policies. After documenting that municipalities led by women outperformed those led by men during the pandemic, we investigate which policy choices can explain this. Table 2 displays the effect of having a female mayor on health investments and NPIs. Panel A reports health investment-related outcomes, divided into pre and post-pandemic outbreak outcomes. First column displays the effect on the share of municipal spending dedicated to health issues between 2016 and 2019. Second and third columns show the effects on the change between Jan 2017 and Jan 2020 in the number of total and ICU hospital beds per 100 thousand inhabitants, respectively. Fourth column shows the same outcome as the first one, but for the year of 2020. Fifth and sixth columns show, respectively, estimates for the variation in total and ICU beds between February and December 2020. Results in Panel A show that the presence of a female leader is not associated with any changes in those outcomes, which suggests that they are unlikely to be driving our previous results.

Table 2.

Impact of female leadership on health investment and non-pharmaceutical interventions, RDD estimates.

|

Panel A: Health investment |

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pre-outbreak |

Post-outbreak |

|||||

| Health spending | Total hosp. beds | ICU hosp. beds | Health spending | Total hosp. beds | ICU hosp. beds | |

| (share of total spd.) | per 100k pop. | per 100k pop. | (share of total spd.) | per 100k pop. | per 100k pop. | |

| RD estimator | −0.005 | −9.992 | −0.372 | 0.004 | −3.212 | −0.084 |

| Robust -value | 0.678 | 0.281 | 0.235 | 0.749 | 0.519 | 0.89 |

| Robust conf. int. | [−0.0273, 0.0178] | [−28.1529, 8.168] | [−0.9858, 0.2418] | [−0.0207, 0.0288] | [−12.9813, 6.5565] | [−1.2766, 1.1078] |

| CCT-optimal BW | 15.95 | 19.075 | 8.094 | 22.881 | 12.062 | 11.66 |

| Eff. number obs. | 745 | 871 | 472 | 753 | 626 | 613 |

|

Panel B: Non-pharmaceutical interventions |

||||||

| Number of | Face covering | Gatherings | Cordon | Closure of | Public transport | |

| NPIs | required | prohibition | sanitaire | non-essentials | restriction | |

| RD estimator | 0.371 | 0.08 | 0.055 | 0.14 | −0.071 | 0.131 |

| Robust -value | 0.057* | 0.04** | 0.066* | 0.083* | 0.414 | 0.221 |

| Robust conf. int. | [−0.0109, 0.7538] | [0.0038, 0.1569] | [−0.0037, 0.1143] | [−0.0184, 0.298] | [−0.2396, 0.0986] | [−0.0783, 0.3395] |

| CCT-optimal BW | 10.254 | 15.671 | 9.479 | 12.224 | 10.053 | 10.784 |

| Eff. number obs. | 353 | 499 | 341 | 395 | 349 | 361 |

Notes: This table reports our RD estimates of the association between female mayors and several outcomes. The level of observation is the municipality. Panel A reports results on health investment-related outcomes. This panel is divided into pre and post pandemic outbreak outcomes. In the first column of Panel A, the outcome is the variation in the share of municipal spending dedicated to health issues between 2016 and 2019. In the second column, the outcome is the variation of total hospital beds per 100k inhabitants between Jan 2017 and Jan 2020; in the third column, the ICU hospital beds per 100k inhabitants variation between Jan 2017 and Jan 2020. The fourth column reports the estimate of the variation in the share of municipal spending dedicated to health issues between 2019 and 2020. Lastly, the fifth and sixth columns show estimates for the variation of hospital beds per 100k inhabitants between Feb 2020 and Dec 2020 — total beds and ICU beds, respectively. Panel B describes results for the main non-pharmaceutical interventions adopted by mayors until July 2020. The first column outcome is the total number of NPIs adopted. The remaining columns are dummies variables indicating whether a specific NPI was adopted. In any case, we are estimating a first-degree polynomial using a uniform kernel. Optimal bandwidths following Calonico et al. (2014) were chosen to minimize the mean squared error of the local polynomial RD point estimator. Following that same work, we report robust-bias corrected -values and 95% CIs. All estimates account for state fixed-effects following Eq. (1). Coefficients significantly different from zero at 99% (***), 95% (**) and 90% (*) confidence level.

Panel B of Table 2 presents RD estimates for NPIs. In the first column, we report our effects using the total number of interventions as the outcome. In the second through sixth columns, the outcomes are indicator variables for, respectively, enforcing facial covering, forbidding public gatherings, adopting cordons sanitaires, closing non-essential businesses, and reducing the frequency of public transportation. Results reported in this panel suggest that the enforcement of NPIs is the likely mechanism explaining the difference in deaths and hospitalizations documented in Table 1. In the first column we show that, on average, municipalities ruled by women adopted 0.371 more NPIs than those ruled by men. This effect is significant and represents an increase of around percent compared to the number of interventions adopted in the control group. In the second through fourth columns we document, respectively, that women are percentage points (p.p) more likely to adopt compulsory face-covering, 5.5 p.p. more likely to forbid agglomerations and p.p. more likely to establish cordons sanitaires in their municipalities. Results in the remaining columns, however, are not significant. These results are displayed graphically in Fig. A5. The effects of electing a female mayor on epidemiological outcomes and adoption of NPIs are consistent with recent evidence showing that such measures decrease the severity of the pandemic (Mitze et al., 2020, Lyu and Wehby, 2020).11

Mayor’s characteristics. While our RD design accounts for municipality-specific omitted variables, it does not control for mayors’ individual characteristics that are relevant for policymaking, such as age (Alesina et al., 2019), education (Besley et al., 2011) and ideology (Pettersson-Lidbom, 2008). To evaluate this, we test whether women that win close races against men are different in observable characteristics in Table A10. The results suggest a difference in the level of education which is not robust to a quadratic polynomial and a difference in party ideology that is. In order to better understand the mechanism behind our findings, we run our main specification accounting for these two covariates following Calonico et al. (2019). We show that our results are robust to controlling for education and ideology of the mayor in Tables A11 and A12, suggesting that our findings are driven by female mayors’ non-observable characteristics.

Under-reporting and measurement error. One concern is that strategic under-reporting of COVID-19 cases and deaths could be somehow driving our results. We believe it is unlikely that measurement error caused by strategic under-reporting of COVID-19 explains our results for two main reasons. First, as shown in Table 1, estimates using broad SARI outcomes, which do not depend on COVID-19 testing, are similar to those using COVID-19 outcomes. Second, there should be more intense under-reporting among women than men to rationalize our results, which seems unlikely given the evidence from several countries, including Brazil, suggesting that women are, on average, less corrupt than men (Brollo and Troiano, 2016, Afridi et al., 2017, Decarolis et al., 2021).

Potential explanations. As previously documented by Funk and Gathmann (2014), women tend to have stronger preferences over health care investments. However, it is unlikely that this explains our results because health investment per capita did not increase after electing a woman either before or after the COVID-19 outbreak. Olcaysoy Okten et al. (2020) documents that women adhere more to social distancing and hand-washing than men during the pandemic, suggesting more subtle preference features are likely to explain the choices of female leaders.

Croson and Gneezy (2009) surveys the evidence studying gender differences in preferences and conclude that women are usually more risk-averse and less overconfident than man. Higher risk-aversion may explain why women adopted more NPIs than men to mitigate death risks during the pandemic. The absence of policy and economic effects before the pandemic could be consistent with risk aversion if pre-pandemic health risks were low or budget constraints prevented increases in health care investment. Lower overconfidence and more weight to scientific advice among female leaders may also explain why they enforce more NPIs despite similar healthcare investments prior to the pandemic.

Woman leadership and support for President Bolsonaro. As a final step in our analysis, we investigate whether popular support to president Bolsonaro, who openly disavowed NPIs during the pandemic, influenced the effects of female leadership. More precisely, we compare the effect of electing a female mayor on our epidemiological and policy outcomes in municipalities above and below the median of the distribution of Bolsonaro’s vote share in the 2018 election.

On one hand, it is reasonable to expect that in places where Bolsonaro had stronger support, citizens tended to be more dismissive of the negative externalities of COVID-19 (Ajzenman et al., 2020). In this case, local leaders had an incentive to enforce NPIs in order to minimize the adverse effects of the pandemic, since the local population is less likely to voluntarily adopt these measures. On the other hand, a high vote share in Bolsonaro in 2018 can be understood by incumbents as a public signal of citizens’ preferences which, in turn, may lead mayors to align themselves with the president. Which incentive is stronger for female candidates is the empirical question we aim to answer in this section.

In Table 3 we provide evidence that the effect of female leadership is stronger in municipalities where the support for President Bolsonaro is higher.12 In Panel A we investigate the heterogeneous effect in municipalities where the population strongly supports Bolsonaro. Results in the first and second columns show that electing a woman caused, respectively, a decrease of 42.49 and 80.53 in COVID-19 deaths and hospitalizations per 100 thousand in this subset of municipalities. The results are similar for SARI outcomes. Finally, the estimate in the fifth column shows that women in these municipalities adopt 0.425 more NPIs than men on average. In Panel B we present the results of similar exercises for municipalities where President Bolsonaro enjoys lower support. We find that the difference in these outcomes is not statistically significant between municipalities ruled by women and men in this sample. Except for the numbers of NPIs, these results are robust to a local quadratic specification as shown in Table A13 in the appendix.

The findings above highlight that the role of female leaders is magnified when the population is susceptible to be misled by populist national leaders, such as the case of Bolsonaro and his voters. When faced with the decision between enforcing health measures against COVID-19 or trying to conquer the votes of local Bolsonaro supporters, our results suggest that female mayors were more likely to prioritize measures that can save lives.

Table 3.

Impact of female leadership according to President Bolsonaro support.

| COVID-19 deaths | COVID-19 hospitalizations | SARI deaths | SARI hospitalizations | Number of | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| per 100k pop. | per 100k pop. | per 100k pop. | per 100k pop. | NPIs | |

| Panel A: Above median | |||||

| RD estimator | −42.4906 | −80.5309 | −30.3938 | −96.7758 | 0.4259 |

| Robust -value | 0.0001*** | 0.014** | 0.019** | 0.034** | 0.08* |

| Robust conf. int. | [−67.019, −17.9622] | [−144.6325, −16.4292] | [−55.7461, −5.0416] | [−186.3234, −7.2281] | [−0.0533, 0.905] |

| CCT-optimal BW | 9.0354 | 8.739 | 11.4588 | 9.4088 | 10.5465 |

| Eff. number obs. | 236 | 227 | 267 | 240 | 210 |

| Panel B: Below median | |||||

| RD estimator | −10.2105 | −9.5123 | −23.0019 | −12.2503 | 0.2519 |

| Robust -value | 0.5765 | 0.2835 | 0.34 | 0.2424 | 0.3994 |

| Robust conf. int. | [−46.0458, 25.6247] | [−26.8966, 7.872] | [−70.2493, 24.2455] | [−32.7891, 8.2885] | [−0.334, 0.8378] |

| CCT-optimal BW | 8.1987 | 8.9333 | 10.2634 | 10.2952 | 7.9198 |

| Eff. number obs. | 256 | 271 | 306 | 306 | 123 |

Notes: This table reports our RD estimates of the effect of female mayors on few COVID-19 and SARI related outcomes accordingly to Jair Bolsonaro’s support across municipalities in the Brazilian 2018 presidential election’s second round. The four first columns show our primary outcomes: the number of hospitalizations and deaths by COVID-19 and SARI per hundred thousand inhabitants in 2020 — note that COVID-19 numbers are a subset of SARI numbers. The last column shows the estimate for the number of adopted non-pharmaceutical interventions in the municipality until July 2020. Panel A shows results for municipalities with Bolsonaro’s vote-share above (or equal) to Bolsonaro’s median municipal vote share. Panel B shows results for municipalities with Bolsonaro’s vote-share below Bolsonaro’s median municipal vote-share. In both cases, we estimate a first-degree polynomial using a uniform kernel. Optimal bandwidths following Calonico et al. (2014) were chosen to minimize the mean squared error of the local polynomial RD point estimator. Following that same work, we report robust-bias corrected -values and 95% CIs. All estimates account for state fixed-effects following Eq. (1). Coefficients significantly different from zero at 99% (***), 95% (**) and 90% (*) confidence level.

5. Conclusion

In this paper we showed that the election of female mayors caused a large, negative, and significant decrease in the number of deaths and hospitalizations from COVID-19 during the first wave of the pandemic in Brazil. We also presented evidence these effects are stronger in municipalities where Brazil’s far-right president, who publicly disavowed the importance of non-pharmaceutical interventions, had a higher vote share in the 2018 election. Finally, we presented suggestive evidence that enacting more NPIs is likely the mechanism explaining our results.

Given the local nature of our RD findings, drawing inference on female leaders in general in tackling global pandemic containment requires further empirical support. Nevertheless, our findings add evidence to the body of research that, in many different settings, finds positive effects of female leadership on policy outcomes. More specifically, we showed how, in our context, these leaders performed better than men during a severe crisis.

Our findings also raise some questions for future research. First, they open an avenue for future work investigating female leadership after controlling the health crisis. More specifically, it is interesting to study whether female leaders also outperformed men in accelerating vaccination programs and promoting economic recovery after the pandemic.

Second, they beg the question of whether we should expect female leadership to fare better also in the private sector. Even though there is suggestive evidence that perceived over-performance of female corporate leaders increased during the COVID-19 health crisis, the public and private sector incentives are arguably different. Therefore, there is room to investigate if such perceived performance translates into better outcomes in the private sector during a crisis. More specifically, future research could investigate whether companies led by women had higher profits and healthier employees than those led by men during these difficult times.

Acknowledgment

All authors approved the final version of the manuscript.

Footnotes

We thank the editor Tom Vogl and two anonymous referees for their valuable insights. We also thank Sergio Firpo, Jéssica Gagete-Miranda, Lucas Mariani, Lucas Novaes, Santiago Perez-Vincent, Vitor Possebom, Rodrigo Soares, Graziella Testa and participants at the Insper Applied Microeconomics Workshop, IPEA Ninsoc Workshop and the ERSA Public Economics Webinar Series for comments and suggestions.

Although the optimal bandwidth we obtain may be considered large, it is consistent with other papers using close election as an RD design in Brazil such as Brollo and Troiano (2016) and Arvate et al. (2021).

As state capitals and municipalities with more than 200 thousand inhabitants may hold runoff elections, we exclude them from our estimating sample to ensure that our running variable determines the gender of the mayor and use a sharp RD design.

Afridi et al. (2017) show that female mayors are less likely to be involved in corruption in India, and Decarolis et al. (2021) show that bureaucratic corruption is less intense among women in Italy and China. Chattopadhyay and Duflo (2004), Clots-Figueras, 2011, Clots-Figueras, 2012, Bhalotra and Clots-Figueras (2014), and Baskaran and Hessami (2018) show that female leadership improves policy outcomes in India. In contrast, Bagues and Campa (2021), Gago and Carozzi (2021), Casarico et al. (2021), and Ferreira and Gyourko (2014) show that female leadership has no impact on outcomes in Spain, Italy, and United States.

See Baltrunaite et al. (2019), Bhalotra et al. (2020), and Bagues and Campa (2021) for examples of policies that increase female representation in politics.

More information on the methodology is available on de Souza Santos et al. (2021).

The fixed-effect term is added following the recommended approach in Calonico et al. (2019).

Standardized coefficients are defined by , where is the standard deviation of each covariate in the graph within the optimal bandwidth range.

See McCrary (2008).

See Leuven et al. (2007), Colonnelli et al. (2020) and Daniele and Giommoni (2021) for similar strategies.

Coefficients and standard errors are reported in Table A14.

We provide several robustness checks in Appendix. In Table A9 we show that both the adoption of face covering and prohibition of social gatherings are robust to a specification with a local quadratic fit. Estimates are also robust to different bandwidth lengths (Fig. A6) and placebo checks present the expected pattern from a true causal relation (Fig. A7). We highlight that as bandwidth is reduced, variance increases, but point estimates remain similar.

We define high and low support as having, respectively, a vote share above or below the median.

Supplementary material related to this article can be found online at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jdeveco.2021.102761.

Appendix A. Supplementary data

The following is the Supplementary material related to this article.

Supplementary material.

Data availability

Data will be made available on request.

References

- Abras A., Fava A.C.P.e, Kuwahara M.Y. Women heads of state and Covid-19 policy responses. Fem. Econ. 2021;27(1–2):380–400. [Google Scholar]

- Afridi F., Iversen V., Sharan M.R. Women political leaders, corruption, and learning: Evidence from a large public program in India. Econom. Dev. Cult. Chang. 2017;66(1):1–30. [Google Scholar]

- Ajzenman N., Cavalcanti T., Da Mata D. 2020. More than words: Leaders’ speech and risky behavior during a pandemic. Available at SSRN 3582908. [Google Scholar]

- Aldrich A.S., Lotito N.J. Pandemic performance: Women leaders in the Covid-19 crisis. Politics Gend. 2020:1–9. [Google Scholar]

- Alesina A., Cassidy T., Troiano U. Old and young politicians. Economica. 2019;86(344):689–727. [Google Scholar]

- Andrade M.V., Lisboa M.B. In: Microeconomia e Sociedade no Brasil. Lisboa M.B., Menezes-Filho N.A., Kassouf A.L., editors. Contra Capa; Rio de Janeiro: 2002. A economia da Saúde no Brasil. [Google Scholar]

- Arvate P., Firpo S., Pieri R. Future electoral impacts of having a female mayor. Braz. Political Sci. Rev. 2017;11 [Google Scholar]

- Arvate P., Firpo S., Pieri R. Can women’s performance in elections determine the engagement of adolescent girls in politics? Eur. J. Political Econ. 2021 [Google Scholar]

- Bagues M., Campa P. Can gender quotas in candidate lists empower women? Evidence from a regression discontinuity design. J. Public Econ. 2021;194 [Google Scholar]

- Baltrunaite A., Casarico A., Profeta P., Savio G. Let the voters choose women. J. Public Econ. 2019;180 [Google Scholar]

- Barberia L.G., Gómez E.J. Political and institutional perils of Brazil’s COVID-19 crisis. Lancet. 2020;396(10248):367–-368. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)31681-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barbosa M.C. University of California; San Diego: 2017. The Impact of Mayor Leadership on Local Policy and Politics: Evidence from Close Elections in Brazil. [Google Scholar]

- Baskaran T., Hessami Z. Does the election of a female leader clear the way for more women in politics? Am. Econ. J. Econ. Policy. 2018;10(3):95–121. [Google Scholar]

- Beaman L., Chattopadhyay R., Duflo E., Pande R., Topalova P. Powerful women: Does exposure reduce bias? Q. J. Econ. 2009;124(4):1497–1540. [Google Scholar]

- Besley T., Montalvo J.G., Reynal-Querol M. Do educated leaders matter? Econ. J. 2011;121(554):F205–F227. [Google Scholar]

- Bhalotra, S., Clarke, D., Gomes, J.F., Venkataramani, A., 2020. Maternal Mortality and Women’s Political Participation. C.E.P.R. Discussion Papers 14339.

- Bhalotra S., Clots-Figueras I. Health and the political agency of women. Am. Econ. J. Econ. Policy. 2014;6(2):164–197. [Google Scholar]

- Bhalotra S., Rocha R., Soares R.R. School of International and Public Affairs, Columbia University; 2019. Does Universalization of Health Work? Evidence from Health Systems Restructuring and Expansion in Brazil: Center on Global Economic Governance Working Paper 72. [Google Scholar]

- Boas T.C., Hidalgo F.D., Melo M.A. Norms versus action: Why voters fail to sanction malfeasance in Brazil. Am. J. Political Sci. 2019;63(2):385–400. [Google Scholar]

- Brollo F., Troiano U. What happens when a woman wins an election? Evidence from close races in Brazil. J. Dev. Econ. 2016;122:28–45. [Google Scholar]

- Calonico S., Cattaneo M., Farrell M.H., Titiunik R. Regression discontinuity designs using covariates. Rev. Econ. Stat. 2019;101(3):442–451. [Google Scholar]

- Calonico S., Cattaneo M.D., Titiunik R. Robust nonparametric confidence intervals for regression-discontinuity designs. Econometrica. 2014;82(6):2295–2326. [Google Scholar]

- Calonico S., Cattaneo M.D., Titiunik R. Optimal data-driven regression discontinuity plots. J. Amer. Statist. Assoc. 2015;110(512):1753–1769. [Google Scholar]

- Casarico, A., Lattanzio, S., Profeta, P., 2021. Women and Local Public Finance. Working Paper.

- Castro M.C., Kim S., Barberia L., Ribeiro A.F., Gurzenda S., Ribeiro K.B., Abbott E., Blossom J., Rache B., Singer B.H. Spatiotemporal pattern of COVID-19 spread in Brazil. Science. 2021;372(6544):821–826. doi: 10.1126/science.abh1558. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Castro M.C., Massuda A., Almeida G., Menezes-Filho N.A., Andrade M.V., de Souza Noronha K.V.M., Rocha R., Macinko J., Hone T., Tasca R., Giovanella L., Malik A.M., Werneck H., Fachini L.A., Atun R. Brazil’s unified health system: The first 30 years and prospects for the future. Lancet. 2019;394(10195):345–356. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(19)31243-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chattopadhyay R., Duflo E. Women as policy makers: Evidence from a randomized policy experiment in India. Econometrica. 2004;72(5):1409–1443. [Google Scholar]

- Clots-Figueras I. Women in politics: Evidence from the Indian states. J. Public Econ. 2011;95(7–8):664–690. [Google Scholar]

- Clots-Figueras I. Are female leaders good for education? Evidence from India. Am. Econ. J. Appl. Econ. 2012;4(1):212–244. [Google Scholar]

- Colonnelli E., Prem M., Teso E. Patronage and selection in public sector organizations. Amer. Econ. Rev. 2020;110(10):3071–3099. [Google Scholar]

- Croson R., Gneezy U. Gender differences in preferences. J. Econ. Lit. 2009;47(2):448–474. [Google Scholar]

- Daniele, G., Giommoni, T., 2021. Corruption under austerity. CEPR Discussion Paper No. DP15891.

- Daniels J.P. Health experts slam Bolsonaro’s vaccine comments. Lancet. 2021;397(10272):361. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(21)00181-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Decarolis F., Fisman R., Pinotti P., Vannutelli S., Wang Y. Working Paper Series. National Bureau of Economic Research; 2021. Gender and Bureaucratic Corruption: Evidence from Two Countries. [Google Scholar]

- Ferigato S., Fernandez M., Amorim M., Ambrogi I., Fernandes L.M.M., Pacheco R. The Brazilian government’s mistakes in responding to the COVID-19 pandemic. Lancet. 2020;396(10263):1636. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)32164-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ferreira F., Gyourko J. Does gender matter for political leadership? The case of US mayors. J. Public Econ. 2014;112:24–39. [Google Scholar]

- Funk P., Gathmann C. Gender gaps in policy making: Evidence from direct democracy in Switzerland. Econ. Policy. 2014;30(81):141–181. [Google Scholar]

- Gago, A., Carozzi, F., 2021. Do Female Leaders Promote Gender-Sensitive Policies? Working Paper.

- Garikipati S., Kambhampati U. Leading the fight against the pandemic: Does gender really matter? Fem. Econ. 2021;27(1–2):401–418. [Google Scholar]

- Gelman A., Imbens G. Why high-order polynomials should not be used in regression discontinuity designs. J. Bus. Econom. Statist. 2019;37(3):447–456. [Google Scholar]

- Hasell J., Mathieu E., Beltekian D., Macdonald B., Giattino C., Ortiz-Ospina E., Roser M., Ritchie H. A cross-country database of COVID-19 testing. Sci. Data. 2020;7(1):345. doi: 10.1038/s41597-020-00688-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hecksher M. Instituto de Pesquisa Economica Aplicada; 2020. Mortalidade por Covid-19 e Queda do Emprego no Brasil e no Mundo: Nota Técnica do. [Google Scholar]

- Henley J. 2020. Female-led countries handled coronavirus better, study suggests. [Google Scholar]

- Hessami Z., da Fonseca M.L. Female political representation and substantive effects on policies: A literature review. Eur. J. Political Econ. 2020;63 [Google Scholar]

- IBGE . Instituto Brasileiro de Geografia e Estatística; 2019. Pesquisa nacional de saúde. informações sobre domicílios, acesso e utilização dos serviços de saúde: Technical report. [Google Scholar]

- Iyer L., Mani A., Mishra P., Topalova P. The power of political voice: Women’s political representation and crime in India. Am. Econ. J. Appl. Econ. 2012;4(4):165–193. [Google Scholar]

- Jones B.F., Olken B.A. Do leaders matter? National leadership and growth since world war II. Q. J. Econ. 2005;120(3):835–864. [Google Scholar]

- Leuven E., Lindahl M., Oosterbeek H., Webbink D. The effect of extra funding for disadvantaged pupils on achievement. Rev. Econ. Stat. 2007;89(4):721–736. [Google Scholar]

- Londoño E., Simões M. Brazil president embraces unproven ‘cure’ as pandemic surges. N.Y. Times. 2020 [Google Scholar]

- Lott J.R., Kenny L.W. Did women’s suffrage change the size and scope of government? J. Polit. Econ. 1999;107(6):1163–1198. [Google Scholar]

- Lyu W., Wehby G.L. Community use of face masks and COVID-19: Evidence from a natural experiment of state mandates in the US. Health Aff. 2020;39(8):1419–1425. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.2020.00818. PMID: 32543923. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marcelino U., Slattery G. 2020. Brazil’s Bolsonaro headlines anti-democratic rally amid alarm over handling of coronavirus. [Google Scholar]

- Mariani L.A., Gagete-Miranda J., Rettl P. Words can hurt: How political communication can change the pace of an epidemic. Covid Econ. Vetted Real-Time Pap. 2020;12:104–137. [Google Scholar]

- McCrary J. Manipulation of the running variable in the regression discontinuity design: A density test. J. Econometrics. 2008;142(2):698–714. [Google Scholar]

- Miller G. Women’s suffrage, political responsiveness, and child survival in American history. Q. J. Econ. 2008;123(3):1287–1327. doi: 10.1162/qjec.2008.123.3.1287. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mitze T., Kosfeld R., Rode J., Wälde K. Face masks considerably reduce COVID-19 cases in Germany. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 2020;117(51):32293–32301. doi: 10.1073/pnas.2015954117. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Olcaysoy Okten I., Gollwitzer A., Oettingen G. Gender differences in preventing the spread of coronavirus. Behav. Sci. Policy Assoc. 2020 [Google Scholar]

- Pettersson-Lidbom P. Do parties matter for economic outcomes? A regression-discontinuity approach. J. Eur. Econom. Assoc. 2008;6(5):1037–1056. [Google Scholar]

- Piscopo J.M. Women leaders and pandemic performance: A spurious correlation. Politics Gend. 2020:1–9. [Google Scholar]

- Power T.J., Rodrigues-Silveira R. Mapping ideological preferences in Brazilian elections, 1994–2018: A municipal-level study. Braz. Political Sci. Rev. 2019;13(1) [Google Scholar]

- Rafkin C., Shreekumar A., Vautrey P.-L. When guidance changes: Government stances and public beliefs. J. Public Econ. 2021;196 [Google Scholar]

- Sergent K., Stajkovic A.D. Women’s leadership is associated with fewer deaths during the COVID-19 crisis: Quantitative and qualitative analyses of United States governors. J. Appl. Psychol. 2020;105(8):771–783. doi: 10.1037/apl0000577. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Souza W.M.de, Buss L.F., da Silva Candido D., Carrera J.P., Li S., Zarebski A., Vincenti-Gonzalez M., Messina J., Sales F.C.d.S., Andrade P.d.S., Prete C.A., Nascimento V.H., Ghilardi F., Pereira R.H.M., Santos A.A.d.S., Abade L., Gutierrez B., Kraemer M.U.G., Aguiar R.S., Alexander N., Mayaud P., Brady O.J., Souza I.O.M.d., Gouveia N., Li G., Tami A., Oliveira S.B., Porto V.B.G., Ganem F., Almeida W.F., Fantinato F.F.S.T., Macario E.M., Oliveira W.K., Pybus O., Wu C.-H., Croda J., Sabino E.C., Faria N.R. Epidemiological and clinical characteristics of the early phase of the COVID-19 epidemic in Brazil. medRxiv. 2020 [Google Scholar]

- de Souza F.S.H., Hojo-Souza N.S., Batista B.D.d.O., da Silva C.M., Guidoni D.L. On the analysis of mortality risk factors for hospitalized COVID-19 patients: A data-driven study using the major Brazilian database. PLoS One. 2021;16(3):1–21. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0248580. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Souza Santos A.A., da Silva Candido D., de Souza W.M., Buss L., Li S.L., Pereira R.H., Wu C.-H., Sabino E.C., Faria N.R. Dataset on SARS-CoV-2 non-pharmaceutical interventions in Brazilian municipalities. Sci. Data. 2021;8(1):1–6. doi: 10.1038/s41597-021-00859-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Supremo Tribunal Federal . 2020. Medida Cautelar na Ação Direta de Inconstitucionalidade 6.341. Distrito Federal. [Google Scholar]

- Taub A. Why are women-led nations doing better with Covid-19? A new leadership style offers promise for a new era of global threats. N.Y. Times. 2020 [Google Scholar]

- The Economist . 2020. Brazil’s president fiddles as a pandemic looms. [Google Scholar]

- The Economist . 2020. Jair Bolsonaro isolates himself, in the wrong way. [Google Scholar]

- Windsor L.C., Yannitell Reinhardt G., Windsor A.J., Ostergard R., Allen S., Burns C., Giger J., Wood R. Gender in the time of COVID-19: Evaluating national leadership and COVID-19 fatalities. PLoS One. 2020;15(12) doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0244531. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yao Y., Zhang M. Subnational leaders and economic growth: Evidence from Chinese cities. J. Econ. Growth. 2015;20(4):405–436. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplementary material.

Data Availability Statement

Data will be made available on request.