Abstract

Nucleoid-associated proteins (NAPs) or histone-like proteins (HLPs) are DNA-binding proteins present in bacteria that play an important role in nucleoid architecture and gene regulation. NAPs affect bacterial nucleoid organization via DNA bending, bridging, or forming aggregates. EbfC is a nucleoid-associated protein identified first in Borrelia burgdorferi, belonging to YbaB/EbfC family of NAPs capable of binding and altering DNA conformation. YbaB, an ortholog of EbfC found in Escherichia coli and Haemophilus influenzae, also acts as a transcriptional regulator. YbaB has a novel tweezer-like structure and binds DNA as homodimers. The homologs of YbaB are found in almost all bacterial species, suggesting a conserved function, yet the physiological role of YbaB protein in many bacteria is not well understood. In this study, we characterized the YbaB/EbfC family DNA-binding protein in Caulobacter crescentus. C. crescentus has one YbaB/EbfC family gene annotated in the genome (YbaBCc) and it shares 41% sequence identity with YbaB/EbfC family NAPs. Computational modeling revealed tweezer-like structure of YbaBCc, a characteristic of YbaB/EbfC family of NAPs. N-terminal–CFP tagged YbaBCc localized with the nucleoid and is able to compact DNA. Unlike B. burgdorferi EbfC protein, YbaBCc protein is a non-specific DNA-binding protein in C. crescentus. Moreover, YbaBCc shields DNA against enzymatic degradation. Collectively, our findings reveal that YbaBCc is a small histone-like protein and may play a role in bacterial chromosome structuring and gene regulation in C. crescentus.

Keywords: DNA binding protein, Caulobacter crescentus, nucleoid associated protein, YbaB/EbfC family, gene regulation

Introduction

Similar to eukaryotic organisms, bacteria also pack their genetic material in a very small space. DNA-binding proteins known as nucleoid-associated proteins (NAPs) play a crucial role in nucleoid structuring and controlling gene expression. Although NAPs are referred to as histone-like proteins (HLPs), they are functionally very distinct from eukaryotic histones. Bacterial cells contain a wide variety of NAPs and their expression in the cell varies with growth phase of the culture. NAPs are small, basic proteins that can have the ability to bind to DNA, either as monomers, dimers, or tetramers or in complex with other DNA modulating proteins (Dorman, 2009; Dillon and Dorman, 2010). The DNA binding occurs either through direct physical interaction or indirectly via binding with other accessory proteins (Dorman, 2014).

Major NAPs involved in nucleoid structuring are HU, IHF, H-NS, Lrp, Fis, and Dps. HU is small, basic, non-sequence specific DNA-binding protein, well conserved in eubacteria (Kamashev and Rouviere-Yaniv, 2000; Bahloul et al., 2001). In dimorphic bacterium, Caulobacter crescentus, HU is a 20-kDa heterodimer consisting of HU1 and HU2 subunits (Le et al., 2013; Le and Laub, 2016). HU protein colocalizes with the nucleoid and has uniform distribution among swarmer and stalked cells but is highly clustered in predivisional cells (Lee et al., 2011). Recently, a new NAP, GapR, was discovered in C. crescentus (Ricci et al., 2016; Arias-Cartin et al., 2017; Taylor et al., 2017). GapR binds AT-rich regions of the nucleoid (Ricci et al., 2016) and absence of GapR leads to morphological and cell division defects (Arias-Cartin et al., 2017; Taylor et al., 2017).

A new family of NAPs, EbfC/YbaB, was first discovered in Borrelia (Babb et al., 2006). The structure of EbfC/YbaB homodimer has been described to have a tweezer-like conformation, with tweezer region ascribed to alpha-helical DNA-binding domain and giving spacer region the ability to fit around double-stranded DNA (Lim et al., 2002; Riley et al., 2009). EbfC protein binding facilitates DNA bending (Riley et al., 2009). In B. burgdorferi, EbfC displays sequence specific DNA binding and binds to a palindromic DNA sequence, 5′-GTnAC-3′, where “n” can be any nucleotide (Riley et al., 2009). However, the DNA binding sites EbfC/YbaB orthologs of E. coli and H. influenzae are not known and are believed to be distinct from that of B. burgdorferi EbfC (Cooley et al., 2009). While EbfC/YbaB is almost present in all eubacteria, its physiological role in most bacterial species remains largely unknown. Here, we characterized YbaBCc, the homolog of YbaB/EbfC family DNA-binding protein in C. crescentus. YbaBCc protein shares 41% sequence identity and has distinctive tweezer-like conformation of ‘YbaB/EbfC family proteins. Moreover, YbaBCc colocalizes with nucleoid and is able to compact DNA. YbaBCc is a non-sequence specific DNA-binding protein with nucleoid-associated function in C. crescentus.

Materials and Methods

Strains, Media, and Growth Conditions

C. crescentus strains were grown in peptone yeast extract (PYE) medium or M2G minimal medium at 30°C (Stove Poindexter’, 1964) and E. coli cells were grown in LB medium at 37°C. Xylose (0.3%), glucose (0.2%), or arabinose (0.2%) was added to the growth media as required. Plasmids and strains used in this study are detailed in Table 1. Details of strain construction are mentioned in Supplementary Text. All media were purchased from Hi-Media Laboratories (Mumbai, India) and antibiotics were obtained from Sigma (United States).

TABLE 1.

Strains and plasmids.

| Relevant genotype or description | Sources/References | |

| C. crescentus | ||

| CB15N | Synchronizable derivative of wild-type strain CB15 (NA 1000) | Evinger and Agabian, 1977 |

| CJW2141 | CB15N cc2570:pTC67 ftsI(Ts) | Costa et al., 2008 |

| RP42 | CB15N xylX:pXCFPN-5-ybabCc | This work |

| RP43 | CB15N/pPAL4 | This work |

| RP45 | CB15N cc2570:pTC67 ftsI(Ts) xylX:pXCFPN-5-ybabCc | This work |

| E. coli | ||

| DH5α | Φ80 ΔlacZΔM15Δ(lacZYA-argF)U169 deoR recA1 endA hsdR17 (rk-,mk +) phoA supE44 thi-1 gyrA96 relA1 | Laboratory strain collection |

| S17 | RP4-2, Tc:Mu, KM-Tn7 | Simon et al., 1983 |

| BL21 (DE3) pLysS | F– ompT hsdSB (rB–, mB–) gal dcm (DE3) pLysS(CamR) | Laboratory strain collection |

| MG1655 | K-12 F– λ– ilvG– rfb-50 rph-1 | Laboratory strain collection |

| RP40 | MG1655/pPAL1 | This work |

| RP41 | BL21 (DE3) pLysS/pPAL3 | This work |

| RP44 | BL21 (DE3) pLysS/pPAL5 | This work |

| RP46 | MG1655/pBAD18 | This work |

| Plasmids | ||

| pBAD18 | Kanr, DH5α containing empty pBAD18 | Guzman et al., 1995 |

| pXCFPN-5 | Tetr, vector used for generating N-terminal protein fusions encoded at the xylX locus | Thanbichler et al., 2007 |

| pET28b | Protein expression vector, Kanr | Laboratory strain collection |

| pJS14 | High copy number vector, pBR1MCS derivative, Cmr | Laboratory strain collection |

| pPAL1 | pBAD18 carrying ybabCc, Kanr | This work |

| pPAL2 | pXCFPN-5 carrying ybabCcfused to CFP | This work |

| pPAL3 | pET28b carrying ybabCcfused to 6X-His at N-terminus | This work |

| pPAL4 | pJS14 carrying ybabCc | This work |

| pPAL5 | pET28b carrying truncated ybabCcfused to 6X-His at N-terminus | This work |

Microscopy and Image Analysis

Expression from Pxyl promoter was obtained by addition of xylose to the growth media at an optical density OD600 0.2. For studying localization of YbaBCc, expression of CFP-fused YbaBCc was obtained from pXCFPN-5 vector in PBP3 temperature-sensitive mutant C. crescentus by addition of xylose (0.2%) at an optical density OD600 0.1 in PYE broth. Cultures were incubated at 30°C for 1 h and then shifted to 37°C and grown for 4.5 h. After this, cells were harvested and washed with M2 medium and processed for 4′, 6′-diamidino-2-phenylindole (DAPI) staining. Cell samples (5 μl) were imaged as described before (Dubey and Priyadarshini, 2018) using Nikon Eclipse Ti microscope (United States) equipped with Nikon DS-U3 camera. Images were processed with Adobe Photoshop CS6. Cell length, nucleoid length, and cell width were analyzed with Fiji (ImageJ) software (Schindelin et al., 2012) and Oufti software (Paintdakhi et al., 2015).

4′, 6′-diamidino-2-phenylindole Staining

For DNA compaction studies, YbaBCc was ectopically expressed in wild-type E. coli MG1655 cells, as described previously with necessary modifications (Ghosh et al., 2013; Oliveira Paiva et al., 2019). C. crescentus YbaBCc was cloned in pBAD18 and transformed into E. coli MG1655. E. coli cells containing YbaBCc and E. coli control strain carrying empty pBAD18 vector were grown overnight at 37°C in LB medium supplemented with 0.2% glucose and kanamycin. Overnight cells were washed twice with LB broth and secondary cultures were induced with 0.2% arabinose or glucose at OD600 0.1. The cells were allowed to grow for 6 h and harvested. Pellets were washed with 1X PBS, fixed in 70% ethanol for 2 min (10% ethanol used in case of colocalization studies with CFP) at room temperature and washed again with 1X PBS. DAPI (1 mg/ml) was added to the cells (1:1,000 dilution) and incubated in dark for 15 min at room temperature. After final wash with 1X PBS, cells were observed by microscopy. For DNA compaction studies, images were captured by Nikon Eclipse Ti 2 Confocal Microscope (AR1MP; United States). Images were processed with Adobe Photoshop CS6. Cell length, nucleoid length, and cell width were analyzed with Fiji (ImageJ) software (Schindelin et al., 2012).

Protein Purification

The coding regions of YbaBCc and YbaBCc (Tn) were amplified by PCR and inserted into pET28b(+) (Novagen) between SacI and BamHI sites. These recombinant vectors were used to express 6X His-tagged YbaBCc and YbaBCc (Tn) proteins in E. coli BL21 (DE3) pLysS cells. Recombinant protein expression was obtained by adding 10 μM IPTG to 0.4 OD600 bacterial culture for 5 h at 37°C in LB medium supplemented with kanamycin. Cells were harvested by centrifugation (10,000 rpm, 5 min, 4°C) and processed for protein purification as described previously with minor modifications (Dubey and Priyadarshini, 2018). The washed pellets were resuspended in the lysis buffer (50 mM Tris–HCl pH 7.5, 100 mM NaCl, 5% glycerol, 5 mM imidazole, 1 mM PMSF) and incubated with 1 mg/ml lysozyme for 45 min in shaker incubator at 37°C. Cells were lysed by sonication and the lysate was clarified by centrifugation (16,000 rpm, 20 min, 4°C). The supernatant was treated with DNaseI (New England Biolabs, United States) for 15 min at 4°C. Supernatant was incubated with Ni2+–NTA agarose beads (Qiagen, Germany) equilibrated in binding buffer (50 mM Tris–HCl pH 7.5, 100 mM NaCl, 5% glycerol and 10 mM imidazole) for 6 h at 4°C. The mixture was passed through a gravity-flow column and washed with wash buffer (50 mM Tris–HCl pH 7.5, 100 mM NaCl, 5% glycerol, and 20 mM imidazole). 6X His-tagged YbaBCc was eluted with elution buffer (50 mM Tris–HCl pH 7.5, 100 mM NaCl, 5% glycerol, and 300 mM imidazole) in multiple fractions. Eluted fractions were visualized on SDS–PAGE by Coomassie staining (Supplementary Figure 3). Protein containing fractions were pooled and given a buffer exchange for Storage buffer (50 mM Tris–HCl pH 7.5, 100 mM NaCl, 5% glycerol), using PD-10 Desalting column (Cytiva, United States). Finally, the protein fraction was concentrated using Amicon® Ultra-4 spin-columns (Millipore, United States). Dot blot and Western blot analysis were performed with 1:5,000 dilution anti-His-antibody (Invitrogen, United States; Supplementary Figure 3). Protein concentration was estimated by Bradford Method (Bradford, 1976).

Western Blot and Dot Blot Analysis

Western blots were performed as described (Dubey and Priyadarshini, 2018). Cell lysates were separated on SDS–PAGE gels and transferred to a polyvinylidene difluoride (PVDF) membrane using a semi-dry transfer apparatus (Bio-Rad, United States). Dot blot was performed as previously described (Bhat and Rao, 2020), with appropriate modifications. Concentrated and diluted purified YbaBCc was spotted onto nitrocellulose membrane and samples were allowed to completely air dry. Membranes were incubated with PBST blocking solution containing 5% non-fat milk at room temperature for 3 h. The membranes were then washed and subsequently incubated with 1:5,000 diluted anti-His antibody (Invitrogen, United States) overnight at 4°C. The next day, membranes were given four 10-min washes in PBST and incubated with horseradish peroxidase-conjugated anti-rabbit antibody (Invitrogen, United States) for 1–2 h at room temperature. Blots were washed with PBST and developed with the Bio-Rad Clarity and Clarity Max ECL Western Blotting Substrates according to the manufacturer’s protocols. 6X His-tagged (Supplementary Figures 3B,C, 4) fusion proteins were confirmed by western blotting for stability.

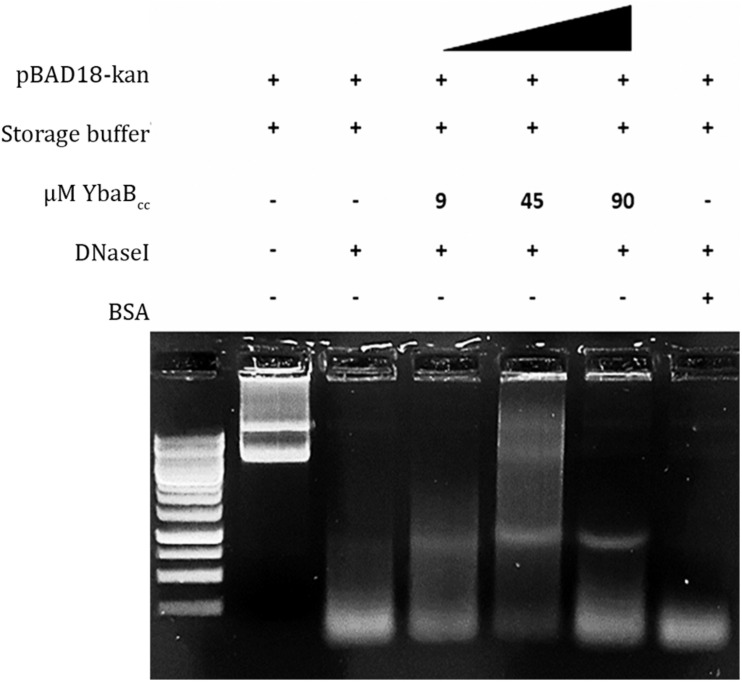

DNA Protection Assay

To investigate DNA binding and protection ability of YbaBCc against degradative action of DNases, pBAD18-kan vector was incubated with increasing YbaBCc protein concentrations (20 min, 25°C) in Storage Buffer. The experiments were performed as described earlier (Datta et al., 2019). In brief, enzyme treatment was given at 37°C for 1 min using 1 Unit of DNaseI (New England Biolabs, United States). The enzyme was inactivated by incubation at 75°C for 15 min followed by protein denaturation at 95°C for 20 min. Reactions were electrophoresed in 1% agarose gel containing ethidium bromide stain and DNA was visualized in a UV transilluminator.

Electrophoretic Mobility Shift Assay

EMSA was performed according to LightShift Chemiluminescent EMSA Kit Protocols, (Thermo Scientific, United States). In brief, oligonucleotides b-WT (124 bp) from Borrelia burgdorferi strain B31 (Riley et al., 2009) and cc-WT (200 bp of ybabCc gene) from C. crescentus (this work) were labeled at 3′ end with Biotin-11-UTP according to the manufacturer’s protocol (Biotin 3′ end DNA Labeling Kit, Thermo Scientific, United States). Labeled target probes were incubated with increasing concentrations of purified YbaBCc in a reaction containing binding buffer (LightShift Chemiluminescent EMSA Kit, Thermo Scientific) and 50% glycerol at 25°C for 30 min. The reactions were electrophoresed in 6% DNA retardation gel (Invitrogen, United States) in 0.5x TBE. Separated DNA products were then electroblotted onto a positively charged Nylon membrane (Thermo Fisher Scientific, United States) using a semi-dry transfer apparatus (Bio-Rad, United States). Cross-linking by UV was done at 120 mJ/cm2 for 1 min immediately after electroblotting. Detection of DNA and DNA-protein complexes was carried using Chemiluminescent Nucleic Acid Detection Module (Thermo Scientific, United States).

Building Computational Model of YbaBCc and Its Complex With DNA

The protein sequence of YbaBCc was retrieved from NCBI (accession id: YP_002515644.1) and was given as input to Robetta tool (Kim et al., 2004),1 where the comparative modeling approach was used to generate 1,000 sample models and obtained the top five models (Kim et al., 2004). The five models were analyzed to select one model using root mean square deviation as a selection measure. Additionally, the model’s confidence score was also taken into consideration for building the protein-DNA complex. The DNA sequence (5′-ATGTAACAGCTGAATGTAACAA-3′) was used to construct a double-stranded B-DNA and the 3D coordinates were obtained using the conformational parameters extracted from fiber-diffraction experimental studies.2 Subsequently, the protein and DNA were given as input to HADDOCK (van Zundert et al., 2016).

Protein-DNA Docking Studies

The parameters of protein-DNA docking were selected in the manner to perform a blind docking approach, where specific interaction site was not specified (Heté Nyi and van der Spoel, 2002; Teotia et al., 2019; Gondil et al., 2020). Additional parameters were set, such as force constant for center of mass contact restraints (1.0), force constant for surface contact restraints (1.0), radius of gyration (17.78), number of structures of rigid body docking (1,000), number of trials of rigid body minimization (5), sample 180 rotated solutions during rigid body EM (Yes), number of structures for semi-flexible refinement (200), sample 180 rotated solutions during semi-flexible SA (No), Perform final refinement (Yes), number of structures for the final refinement (200), number of structures to analyze (200), Fraction of Common Contacts (FCC) method of clustering method, RMSD cutoff for clustering (0.6), minimum cluster size (4), Non-bonded parameters (OPLX), include electrostatic during rigid body docking (Yes), Cutoff distance to define an hydrogen bind (2.5), cutoff distance to define a hydrophobic contact (3.9), Perform cross-docking (Yes), randomize starting orientations (Yes), perform initial rigid body minimization (Yes), allow translation in rigid body transformation (Yes). The top ranked protein-DNA complex from HADDOCK was analyzed using NUCPLOT (Luscombe et al., 1997).

Results

Protein–DNA Complex Indicates Preferential Binding of YbaBCc

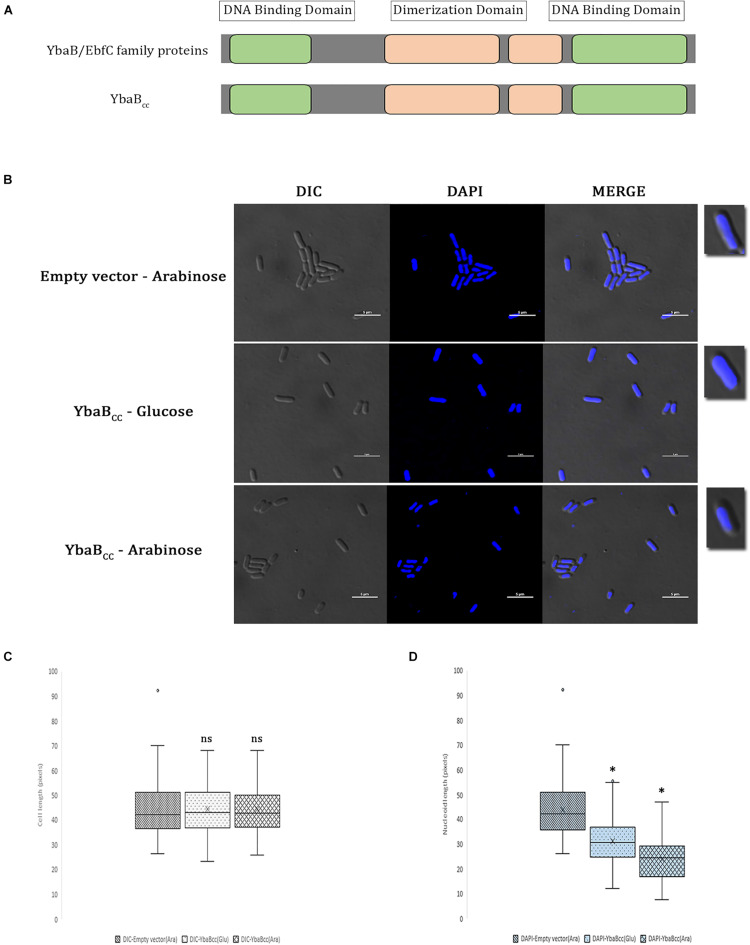

EbfC/YbaB homologs are ubiquitous in nearly all eubacterial genomes. C. crescentus genome CCNA_00269 is annotated as DNA-binding protein and BLAST analysis revealed 41% sequence identity and 62% similarity with EbfC/YbaB family NAPs. EbfC/YbaB family of proteins act as NAPs and have dimerization domains flanked on either side by DNA-binding domains (Babb et al., 2006; Riley et al., 2009). CCNA_00269 revealed similar domain arrangement (Figure 1A). Based on these results we annotated CCNA_00269 gene as ybabCc and characterized its DNA binding properties in this study. EbfC/YbaB family of NAPs colocalize with the nucleoid and probably play a role in structuring of the bacterial chromosome (Jutras et al., 2012; Wang et al., 2012). To investigate DNA compaction activity of YbaBCc protein, we introduced full-length YbaBCc on pBAD18 plasmid into E. coli. Ectopic expression of YbaBCc was induced by addition of arabinose and cells were subsequently stained with DAPI to label the nucleoid (Figure 1B). As evident from Figures 1B–D, only 51.3% of cell length is occupied by the nucleoid in arabinose-induced cells. In comparison, E. coli cells grown with glucose showed 68.4% of the cell length being occupied by nucleoid. Nucleoid compaction observed in presence of glucose could be due to leaky expression from high copy number pBAD18 plasmid (Dubey and Priyadarshini, 2018). In comparison, control RP46 cells carrying empty pBAD plasmid grown in presence of arabinose displayed almost 99% of the cell length being occupied by nucleoid. Our results suggest that YbaBCc protein is able to compact DNA.

FIGURE 1.

YbaBCc binds and compacts DNA in E. coli. (A) Schematic presentation of YbaBCc protein domain organization. YbaB/EbfC family proteins show similarity in domain structures with YbaBCc. There are two DNA-binding domains present at either terminus of YbaB/EbfC family proteins, which together form a unique tweezer-like structure in order to bind to the target DNA. (B) YbaBCc overexpression in E. coli cells. YbaBCc was expressed ectopically from pBAD promoter in RP40 cells. In wild-type E. coli, nucleoid occupies the entire cytoplasmic space, whereas a compacted nucleoid tends to be away from the cell periphery and more toward the center of the bacterial cell. The scale bar represents 5 μM. (C) Box and whisker plots of mean cell length. Whiskers represent minimum and maximum cell lengths observed in each strain (1 μM = 32 pixels). Cross (x) represents mean values and horizontal line across boxes represent the median values. Analysis was done using Fiji (ImageJ) software (n, number of cells analyzed = 99 per strain, per condition). (D) Box and whisker plots of mean nucleoid length. Whiskers represent minimum and maximum nucleoid lengths observed in each strain (1 μM = 32 pixels). Cross (x) represents mean values and horizontal line across boxes represent the median values. Analysis was done using Fiji (ImageJ) software (n, number of cells analyzed = 99 per strain, per condition). (C,D) Same cells were analyzed for measuring cell lengths and nucleoid lengths. YbaBCc protein bound nucleoid reduces in length as compared to the protein-free nucleoid in non-overexpressing conditions. Box and whisker plots (n = 99 per strain) were generated for statistical analysis with the whiskers including all data points within 1.5∗IQR. ns = non-significant. ∗p < 0.0001 by one-way ANOVA compared to the empty vector pBAD (ara) control.

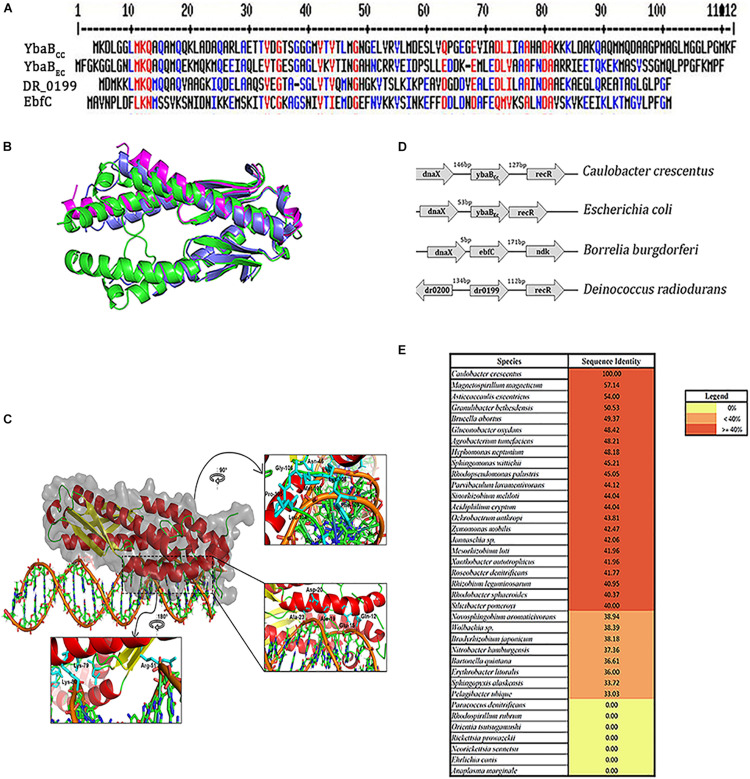

We further searched for YbaB homologs in other alpha-proteobacteria. YbaB homologs were found in most alpha-proteobacteria except, intracellular pathogens belonging to the family Rickettsiaceae (Figure 2E). Rhodospirillum rubrum and Paracoccus denitrificans genome were also devoid of YbaB homologs (Figure 2E). EbfC/YbaB family proteins function as homodimers having a unique “tweezer”-like structure (Lim et al., 2002; Cooley et al., 2009). We obtained a 3D model of YbaBCc protein using Robetta program (Kim et al., 2004). Robetta samples nearly 1,000 models obtained after superposing the partial threads and gives the user five highly ranked models for a given sequence (Kim et al., 2004). For YbaBCc protein sequence, we obtained five models that had a confidence score of 0.75. The confidence score is a qualitative indicator for the user to gauge the success of the modeling, where a confidence score of 0.7 and above for a model is considered as high-quality models that are akin to those obtained by low-resolution X-ray crystallography or NMR experiments (Song et al., 2013). Thus, the confidence score of 0.75 for YbaBCc-modeled structure indicates a high-quality model and Model 1 was taken as the candidate structure for all further experimental analysis. The 3D structure of YbaBCc was strikingly similar to crystalized YbaB/EbfC structures (Lim et al., 2002) showing characteristic tweezer-like conformation (Figure 2B). DNA-binding properties of Model 1 were probed further. The coordinates of Model 1 and DNA were given as input to HADDOCK and the resulting four top-ranked conformations showed that the protein has a preferential site of binding with the nucleic acid (Figure 2C). To explore further protein-DNA interactions were mapped using NUCPLOT, where for each conformation made both hydrogen and hydrophobic interactions were probed. YbaBCc protein models displayed both hydrogen bonds and hydrophobic interactions with DNA (Figure 2C). Further, mapping the electrostatic surface of the modeled YbaBCc protein showed a patch of positively charged surface (sequence range from Arg51 to Ile71, Supplementary Figure 2) that is most likely to interact with DNA. On mapping the electrostatic surface of the modeled YbaBCc protein, a patch of positively charged region (sequence range from Arg51 to Ile71, Supplementary Figure 1) was found giving an idea about where the probable binding site is present. Further, the top scoring protein-DNA complex, obtained from HADDOCK web server, was given as input to the NUCPLOT program. Cut-offs of 3 and 3.35 Å were used for hydrogen bond and other non-bonded interactions, respectively. The interaction network constructed predicted 24 residues interact with the DNA forming both hydrophobic as well as hydrogen bonds. The network predicted a single hydrogen bond formed between Lys79 residue and the 31st nucleotide whereas other residues formed other kinds of non-bonded interactions. Multiple sequence alignment (MSA) of YbaBCc was carried out using MultAlin software (Corpet, 1988), which generated the consensus residues (red color) also present in other YbaB/EbfC family proteins from Borrelia burgdorferi (EbfC), E. coli (YbaBEc), and Deinococcus radiodurans (DR_0199; Figure 2A). Gln-12 and Lys-80 residues are found to be crucial in DNA docking (Figure 2C) and are also common to all four YbaB/EbfC family proteins assessed by MSA (Figure 2A).

FIGURE 2.

YbaBcc is conserved across multiple bacterial species. (A) Multiple sequence alignment of YbaB/EbfC proteins from different bacterial species using MultAlin software (red—high consensus residues, blue—low consensus residues, at the given position). (B) Structural superposition of the modeled YbaBCc protein with structural homologs. The modeled protein (colored green and shown in cartoon representation) is a homodimer, as seen in the structural homologs from E. coli (PDB id: 1PUG) colored light blue. Another structural homolog from Haemophilus influenza (PDB id:1J8B) colored magenta is in monomeric form. Image made using PyMOL. (C) Protein-DNA docking model of YbaBCc (shown in cartoon and surface representation colored in secondary structure) is observed to bind to the DNA motif (5′-ATGTAACAGCTGAATGTAACAA-3′) as obtained from HADDOCK web server. The insets show the orientation of side chains of the interacting residues in stick representation (colored cyan). (D) Schematic representation of the ybaB/ebfC gene locus with adjacent genes in various bacteria. This arrangement of genes appears to be conserved in most bacteria that harbor YbaB/EbfC proteins. (E) YbaB homologs in alpha proteobacteria. Genomes displaying YbaB homologs with more than 40% sequence identity are labeled in red and proteins having identity below 40% are labeled in orange. Bacterial genomes with no YbaB homologs are labeled in yellow.

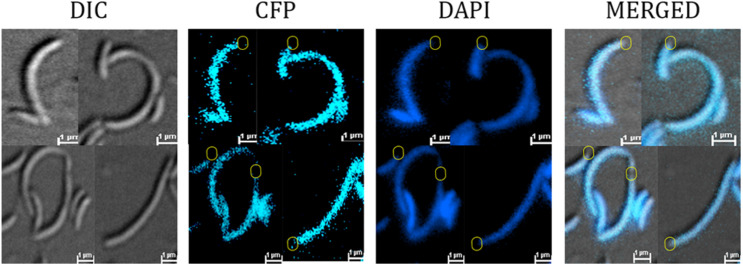

Localization of YbaBCc Protein

To determine the cellular localization of the YbaBCc in Caulobacter cells, YbaBCc was fused with CFP at the N-terminal and expressed from Pxyl promoter. RP42 cells showed CFP signal throughout the cell (Supplementary Figure 1). In C. crescentus cells the chromosome spreads from pole to pole making it difficult to differentiate between cytoplasmic and NAPs colocalization with DNA (Arias-Cartin et al., 2017). To probe whether YbaBCc protein colocalized with the nucleoid, the CFP-YbaBCc fusion protein was expressed in a temperature sensitive ftsI C. crescentus mutant, which forms filaments at the restrictive temperature. In this mutant, YbaBCc colocalized with the DAPI signal and was absent in few DNA-free regions (Figure 3), indicating that YbaBCc is a nucleoid associated protein.

FIGURE 3.

YbaBCc colocalizes with nucleoid in vivo. RP44 cells (CB15N cc2570:pTC67 ftsI(Ts) xylX:pXCFPN-5-ybabCc) were cultured at 30°C for 1 h and then shifted to the restrictive temperature (37°C) for 4.5 h in PYE medium, followed by DAPI staining and imaging on agarose-padded glass slides. Fluorescence imaging shows YbaBCc-CFP colocalizing with DAPI-stained nucleoid in a temperature-sensitive PBP3 mutant Caulobacter crescentus. DNA-free regions devoid of both DAPI and CFP signal are depicted in circles (yellow).

YbaBCc Interaction With DNA Is Not Sequence-Dependent

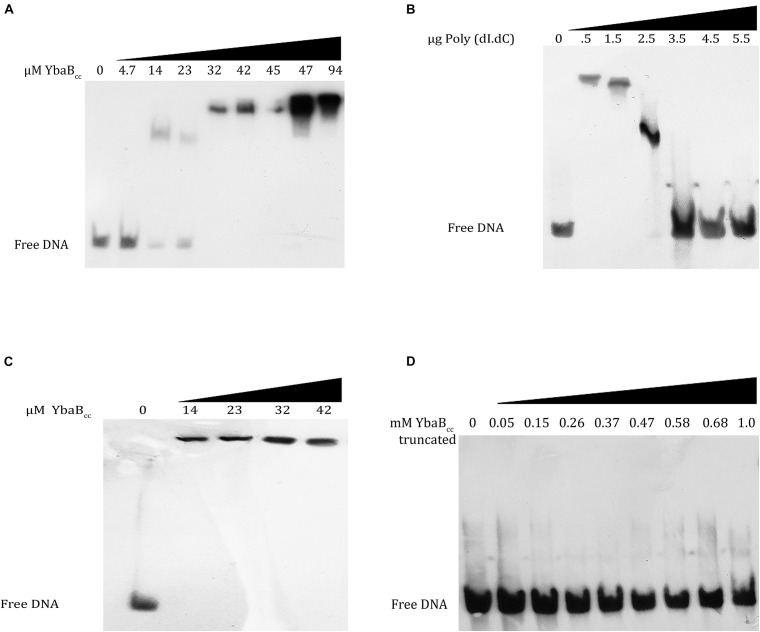

In order to probe the DNA-binding activity of C. crescentus YbaB, we purified YbaBCc protein, tagged with 6X His at the N-terminal. DNA binding of YbaBCc was first tested using biotin labeled DNA probe corresponding to operator sequences of erpAB in B. burgdorferi (b-WT; Riley et al., 2009). This DNA sequence was selected as EbfC protein from B. burgdorferi preferentially binds to sequences within this region. Oligonucleotide b-WT (124 bp) from Borrelia burgdorferi strain B31 (Riley et al., 2009) was incubated with increasing concentrations (0, 4.7, 14, 23, 32, 42, 45, 47, and 94 μM) of YbaBCc protein for electrophoretic mobility shift assay. YbaBCc protein bound to the duplex DNA probes and formed stable protein-DNA complexes (Figure 4A). EbfC preferentially binds to GTnAC sequence found in erpAB operator 2 region (Riley et al., 2009). To investigate the specificity of YbaBCc binding, we performed EMSA with increasing concentrations of poly (dI-dC) probe as a competitor for non-specific DNA-binding activities. As evident from Figure 4B, concentrations above 2.5 μg of poly (dI-dC) probes (∼60-fold higher or above) were able to abolish YbaBCc-DNA complexes, indicating the YbaBCc in C. crescentus might be a non-specific DNA-binding protein. To confirm non-specific DNA-binding activity of YbaBCc, a 200-bp DNA sequence (cc-WT) of ybabCc gene from C. crescentus was amplified and this biotin-labeled DNA duplex was used as probe in EMSA. Even very low concentrations (14 μM) of YbaBCc protein caused super shift of cc-WT sequence probe (Figure 4C). Taken together, our data suggests that YbaBCc interaction with DNA is not sequence dependent.

FIGURE 4.

YbaBCc binds to DNA in a sequence-independent manner in vitro. YbaBCc was incubated with 8 nM each of biotin-labeled probes. (A) b-WT (124 bp) from Borrelia burgdorferi strain B31 was incubated with increasing concentrations (0, 4.7, 14, 23, 32, 42, 45, 47, and 94 μM) of YbaBCc protein. (C) cc-WT (200 bp) Caulobacter probe was incubated with increasing concentrations (0, 14, 23, 32, and 42 μM) of YbaBCc protein. Reactions were electrophoresed on 6% DNA retardation gels and visualized by chemiluminescent detection. YbaBCc forms DNA–protein complexes with both probes (A–C) causing shifts of protein–DNA complexes. (B) Competitive binding was also studied by adding varied concentrations (0, 0.5, 1.5, 2.5, 3.5, 4.5, and 5.5 μg) of Poly (dI.dC) to YbaBCc (32 μM). The presence of free DNA with increasing Poly (dI.dC) indicates sequence independent DNA-binding activity of YbaBCc by exchange of b-WT (124 bp) from Borrelia burgdorferi strainB31 probe with Poly (dI.dC). (D) YbaBCc (Tn) protein (containing only N-terminal DNA-binding domain) was also tested for its ability to bind b-WT Borrelia probe. However, there was no shift observed even at very high protein concentrations rendering this truncated version of YbaBCc to be ineffective in DNA-binding suggesting that both DNA-binding domains are essential for YbaBCc protein to bind target DNA.

B. burgdorferi EbfC variants carrying mutations in α-helix 1 or 3 are defective in DNA binding (Riley et al., 2009). C. crescentus YbaBCc protein, DNA-binding domains are present at both the N- and C-terminus. To investigate if both DNA-binding domains are essential for YbaBCc DNA-binding activities, we created a truncated version—YbaBCc (Tn), deleted for C-terminal DNA-binding domain and consisting of 1–200 bp of ybabCc gene. YbaBCc (Tn) protein was purified and EMSA was performed using b-WT Borrelia oligonucleotide. YbaBCc (Tn) protein was unable to form stable protein-DNA complexes and no shift was observed (Figure 4D). These results suggest that C-terminal DNA-binding domain of YbaBCc is important for DNA-binding activity.

YbaBCc Protects DNA From Degradation

Most NAPs in bacteria are able to protect DNA from degradation. We investigated YbaBCc DNA protection activity by performing DNase I enzymatic degradation assay. Supercoiled pBAD18 plasmid was incubated with increasing YbaBCc protein concentrations and then treated with DNaseI enzyme (Figure 5). As seen in Figure 5, supercoiled plasmid DNA was protected from enzymatic degradation in presence of YbaBCc. In contrast, the control sample incubated with BSA was degraded upon treatment with DNaseI (Figure 5). Our results indicate that YbaBCc protein may protect DNA against damage and degradation.

FIGURE 5.

YbaBCc protects DNA from enzyme degradation. Different concentrations of YbaBCc protein were incubated with supercoiled pBAD18 plasmid DNA, followed by treatment with DNase I restriction enzyme. Control reactions were incubated with BSA in place of YbaBCc protein. YbaBCc prevents complete plasmid DNA degradation by the enzyme as opposed to the BSA control reaction, where DNase I is able to degrade the plasmid completely. Thus indicating that YbaBCc protein-bound plasmid DNA was protected by the degradative action of DNase I restriction enzyme and BSA could not protect the plasmid DNA from being degraded as it does not have DNA-binding activity.

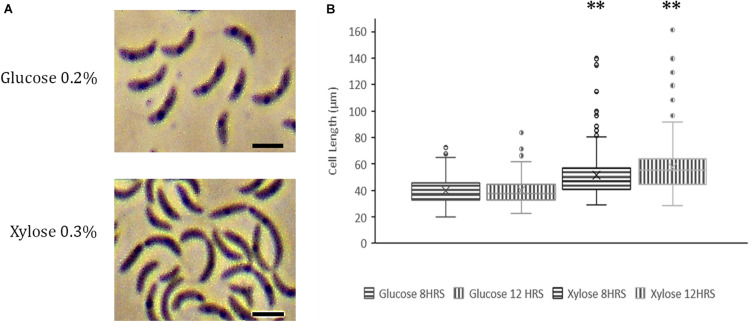

Overexpression of YbaBCc in Nutrient Limiting Conditions Leads to Morphological Aberrations

Abundance of NAPs is highly regulated and fluctuations in protein levels cause adverse effects on cells (Ali Azam et al., 1999). Constitutive overexpression of GapR at high levels is lethal for C. crescentus (Ricci et al., 2016). To investigate whether YbaBCc overexpression leads to abnormalities, we expressed YbaBCc from pJS14 plasmid under the control of xylose promoter. Over expression of YbaBCc caused morphological defects in Caulobacter cells grown in nutrient limiting conditions. Specifically, we observed filamentous cells and conjoined daughter cells with cell separation defects (Figure 6A). Cell length was increased by 44% compared to control cell grown in glucose (Figures 6A,B). It should be noted that overexpression of YbaBCc in cells growing in nutrient rich PYE medium displayed no growth and morphological defects (data not shown). Collectively, our data suggests that YbaBCc concentration in regulated in C. crescentus and probably plays a critical role in stress response.

FIGURE 6.

YbaBCc overexpression in wild-type C. crescentus. (A) Overexpression of YbaBcc leads to morphological defects in C. crescentus. Expression of YbABCc from plasmid pJS14 was induced by the addition of 0.3% xylose at an OD of 0.2 and cells were visualized at the indicated time points by Phase Contrast Microscopy (left panel). All images were taken at 100X magnification and optical zoom 1.5X (Scale bar: 2 μm). (B) Distribution of cell length in populations of YbaBCc overexpressing cells. Micrographs of the strains described in (A) were subjected to automated image analysis. Cell lengths were determined by Oufti Software. Box and whisker plots (n = ± 210 per time point and strain) were generated for statistical analysis of imaging data with the whiskers including all data points within 1.5∗IQR. Cross (x) represents mean values. ∗∗p < 0.0001 by one-way ANOVA compared to the glucose-induced control cells.

Discussion

Bacterial chromosomes are condensed and stabilized by the action of NAPs. NAPs are also involved in global gene expression by making alterations in DNA structure or by interactions with transcriptional machinery. In this study, we have characterized the DNA-binding properties of YbaBCc protein in C. crescentus. YbaBCc belongs to EbfC/YbaB class of DNA-binding proteins, first discovered in B. burgdorferi (Babb et al., 2006). EbfC homodimers have unique tweezer-like structure, where extending α-helices form the arms of the “tweezer” that bind DNA (Lim et al., 2002; Riley et al., 2009). B. burgdorferi EbfC protein is a sequence specific NAP and acts as a global regulator of gene expression. However, YbaBEc and YbaBHi do not preferentially bind B. burgdorferi palindromic DNA sequence (Cooley et al., 2009) EbfC homolog from D. radiodurans also acts as a non-specific DNA-binding protein (Wang et al., 2012). Our results indicate that YbaBCc might act as a non-specific DNA-binding protein. Differences in DNA binding are attributed to amino-acid differences in the putative DNA-binding domain (Cooley et al., 2009). C. crescentus YbaBCc exhibits characteristic tweezer-like conformation of EbfC/YbaB family of NAPs and probably functions as a homodimer. Both N and C-terminals of YbaBCc protein have DNA-binding domains and deletion of the C-terminus DNA-binding domain is sufficient to abolish DNA-duplex binding activity (Figure 4D).

Similar to B. burgdorferi and D. radiodurans, YbaBCc is associated with the nucleoid in C. crescentus (Jutras et al., 2012; Wang et al., 2012; Figure 3). Ectopic expression of YbaBCc in E. coli condensed the nucleoid suggesting involvement of YbaBCc in nucleoid organization and DNA structuring in cells. Collectively our data indicates that YbaBCc is a homolog of EbfC/YbaB and has histone-like activity in C. crescentus.

NAPs are involved in global gene expression by making alterations in DNA structure or by interactions with transcriptional machinery. HU is one of the most abundant NAP in bacteria involved in nucleoid structuring (Shindo et al., 1992; Ghosh and Grove, 2004; Nguyen et al., 2009; Oberto et al., 2009; Berger et al., 2010). Surprisingly, C. crescentus hu deletion mutants deletion mutants display no adverse effect on cell growth, fitness and chromosome architecture (Christen et al., 2011; Lee et al., 2011). Moreover, loss of other NAPs such as IHF and DPS has no fitness cost on C. crescentus indicating functional redundancy among NAPs (Christen et al., 2011). Thus, it is not surprising that YbaBCc is not essential for growth and viability of C. crescentus under standard laboratory conditions (Christen et al., 2011). While ebfC is an essential gene in B. burgdorferi (Riley et al., 2009; Jutras et al., 2012), deletion of efbC homolog from D. radiodurans does not affect cell viability (Wang et al., 2012). However, D. radiodurans dr0199 mutants have increased sensitivity to UV radiation and oxidative stress (Wang et al., 2012).

Role of NAPs in DNA protection is well established. HU from Thermotoga maritima and Helicobactor pylori shield DNA from endolytic cleavage by DNase I and hydroxyl radical-mediated damage (Mukherjee et al., 2008; Almarza et al., 2015). Lsr2 from Mycobacterium tuberculosis acts against reactive oxygen intermediates by directly binding to DNA and shielding the DNA from damage (Colangeli et al., 2009). EbfC homolog from D. radiodurans protects double-stranded DNA from digestion and damage from reactive oxygen species (Wang et al., 2012). Similarly, our results reveal that YbaBCc protects double-stranded DNA from enzymatic degradation, probably by direct protein-DNA binding (Figure 5). YbaBCc may play a crucial role in maintaining genomic integrity by restricting DNA damage in C. crescentus.

Most sequenced eubacterial genomes contain adjacent dnaX and ebfC genes (Flower and Mchenry, 1990; Flower and McHenry, 1991; Chen et al., 1993). In B. burgdorferi and E. coli, dnaX and ebfC are arranged in an operon and are co-transcribed together (Riley et al., 2009). C. crescentus genome also has dnaX gene adjacent to YbaBCc (Figure 2D). The dnaX gene encodes the tau and gamma subunits of DNA polymerase and YbaB is a NAP with ability to compact and protect DNA (Flower and McHenry, 1991; Chen et al., 1993). Transcriptional linkage of dnaX and ybaB/ebfC may allow bacterial cells to respond to DNA damage in a timely and regulated manner. Our preliminary experiments to detect transcriptional linkage between dnaX and YbaBCc did not yield positive results (data not shown). This could be due to low levels of transcripts, as the expression of these genes is growth phase-dependent, or dnaX and YbaBCc maybe transcribed independently in C. crescentus. EbfC levels are highest in exponential phase and rapidly decline in stationary phase in B. burgdorferi (Jutras et al., 2012). RecR protein plays crucial role in DNA recombination and repair is also located on the same locus (Figure 2D; Mahdi and Lloyd, 1989; Yeung’ et al., 1990). Similar to YbaBCc, RecR too is expendable for growth under normal laboratory conditions in C. crescentus (Christen et al., 2011). It is interesting to speculate that both YbaB and RecR may play a role in DNA repair and protection during stress conditions. YbaB homologs are present in most alpha proteobacteria, suggesting an important physiological role of this NAP. Further studies are necessary to elucidate the physiological role of YbaBCc in C. crescentus.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article/Supplementary Material, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author/s.

Author Contributions

RP and PP designed and conceptualized the study. PP and MM performed the experiments. SR and RY performed the bioinformatics analysis. All authors contributed toward the writing of the manuscript.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher’s Note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Acknowledgments

We thank Dr. Karthik Krishnan and the members of the RP lab for their helpful comments and suggestions.

Footnotes

Funding

PP was supported by UGC-NET-JRF and MM was supported by Inspire-Doctoral fellowship. RP lab was supported by CSIR-EMR grant and start-up funds from Shiv Nadar University. Authors also thank SNU for the use of DST-FIST funded Confocal Imaging facility. SR and RY acknowledge SASTRA Deemed to be University for the infrastructural support and research facilities.

Supplementary Material

The Supplementary Material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fmicb.2021.733344/full#supplementary-material

References

- Ali Azam T., Iwata A., Nishimura A., Ueda S., Ishihama A. (1999). Growth phase-dependent variation in protein composition of the Escherichia coli nucleoid. J. Bacteriol. 181 6361–6370. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Almarza O., Nunez D., Toledo H. (2015). The DNA-binding protein HU has a regulatory role in the acid stress response mechanism in Helicobacter pylori. Helicobacter 20 29–40. 10.1111/hel.12171 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arias-Cartin R., Dobihal G. S., Campos M., Surovtsev I. V., Parry B., Jacobs-Wagner C. (2017). Replication fork passage drives asymmetric dynamics of a critical nucleoid-associated protein in Caulobacter. EMBO J. 36 301–318. 10.15252/embj.201695513 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Babb K., Bykowski T., Riley S. P., Miller M. C., Demoll E., Stevenson B. (2006). Borrelia burgdorferi EbfC, a novel, chromosomally encoded protein, binds specific DNA sequences adjacent to erp loci on the spirochete’s resident cp32 prophages. J. Bacteriol. 188 4331–4339. 10.1128/JB.00005-06 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bahloul A., Boubrik F., Rouviere-Yaniv J. (2001). Roles of Escherichia coli histone-like protein HU in DNA replication: HU-beta suppresses the thermosensitivity of dnaA46ts. Biochimie 83 219–229. 10.1016/S0300-9084(01)01246-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berger M., Farcas A., Geertz M., Zhelyazkova P., Brix K., Travers A., et al. (2010). Coordination of genomic structure and transcription by the main bacterial nucleoid-associated protein HU. EMBO Rep. 11 59–64. 10.1038/embor.2009.232 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bhat A. I., Rao G. P. (2020). “Dot-blot hybridization technique,” in Characterization of Plant Viruses: Methods and Protocols, eds Bhat A. I., Rao G. P. (New York, NY: Springer US; ), 303–321. 10.1007/978-1-0716-0334-5_34 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Bradford M. M. (1976). A rapid and sensitive method for the quantitation of microgram quantities of protein utilizing the principle of protein-dye binding. Anal. Biochem. 72 248–254. 10.1016/0003-2697(76)90527-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen K.-S., Saxena P., Walker J. R. (1993). Expression of the Escherichia coli dnaX Gene. J. Bacteriol. 175 6663–6670. 10.1128/jb.175.20.6663-6670.1993 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Christen B., Abeliuk E., Collier J. M., Kalogeraki V. S., Passarelli B., Coller J. A., et al. (2011). The essential genome of a bacterium. Mol. Syst. Biol. 7:528. 10.1038/msb.2011.58 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Colangeli R., Haq A., Arcus V. L., Summers E., Magliozzo R. S., McBride A., et al. (2009). The multifunctional histone-like protein Lsr2 protects mycobacteria against reactive oxygen intermediates. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 106 4414–4418. 10.1073/pnas.0810126106 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cooley A. E., Riley S. P., Kral K., Miller M. C., DeMoll E., Fried M. G., et al. (2009). DNA-binding by Haemophilus influenzae and Escherichia coli YbaB, members of a widely-distributed bacterial protein family. BMC Microbiol. 9:137. 10.1186/1471-2180-9-137 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Corpet F. (1988). Multiple sequence alignment with hierarchical clustering. Nucleic Acids Res. 16 10881–10890. 10.1093/nar/16.22.10881 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Costa T., Priyadarshini R., Jacobs-Wagner C. (2008). Localization of PBP3 in Caulobacter crescentus is highly dynamic and largely relies on its functional transpeptidase domain. Mol. Microbiol. 70 634–651. 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2008.06432.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Datta C., Jha R. K., Ganguly S., Nagaraja V. (2019). NapA (Rv0430), a novel nucleoid-associated protein that regulates a virulence operon in Mycobacterium tuberculosis in a supercoiling-dependent manner. J. Mol. Biol. 431 1576–1591. 10.1016/j.jmb.2019.02.029 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dillon S. C., Dorman C. J. (2010). Bacterial nucleoid-associated proteins, nucleoid structure and gene expression. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 8 185–195. 10.1038/nrmicro2261 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dorman C. J. (2009). Nucleoid-associated proteins and bacterial physiology. Adv. Appl. Microbiol. 67 47–64. 10.1016/S0065-2164(08)01002-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dorman C. J. (2014). Function of nucleoid-associated proteins in chromosome structuring and transcriptional regulation. J. Mol. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 24 316–331. 10.1159/000368850 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dubey A., Priyadarshini R. (2018). Amidase activity is essential for medial localization of AmiC in Caulobacter crescentus. Curr. Genet. 64 661–675. 10.1007/s00294-017-0781-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Evinger M., Agabian N. (1977). Envelope-associated nucleoid from Caulobacter crescentus stalked and swarmer cells. J. Bacteriol. 132 294–301. 10.1128/jb.132.1.294-301.1977 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Flower A. M., Mchenry C. S. (1990). The y subunit of DNA polymerase III holoenzyme of Escherichia coli is produced by ribosomal frameshifting (DNA replication/dnaX/dnaZ/translation/LacZ fusions). Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 87 3713–3717. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Flower A. M., McHenry C. S. (1991). Transcriptional organization of the Escherichia coli dnaX gene. J. Mol. Biol. 220 649–658. 10.1016/0022-2836(91)90107-H [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ghosh S., Grove A. (2004). Histone-like protein HU from Deinococcus radiodurans binds preferentially to four-way DNA junctions. J. Mol. Biol. 337 561–571. 10.1016/j.jmb.2004.02.010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ghosh S., Indi S. S., Nagaraja V. (2013). Regulation of lipid biosynthesis, sliding motility, and biofilm formation by a membrane-anchored nucleoid-associated protein of Mycobacterium tuberculosis. J. Bacteriol. 195 1769–1778. 10.1128/JB.02081-12 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gondil V. S., Dube T., Panda J. J., Yennamalli R. M., Harjai K., Chhibber S. (2020). Comprehensive evaluation of chitosan nanoparticle based phage lysin delivery system; a novel approach to counter S. pneumoniae infections. Int. J. Pharm. 573:118850. 10.1016/j.ijpharm.2019.118850 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guzman L.-M., Belin D., Carson M. J., Beckwith J. (1995). Tight regulation, modulation, and high-level expression by vectors containing the arabinose PBAD promoter. J. Bacteriol. 177 4121–4130. 10.1128/jb.177.14.4121-4130.1995 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heté Nyi C., van der Spoel D. (2002). Efficient docking of peptides to proteins without prior knowledge of the binding site. Protein Sci. 11 1729–1737. 10.1110/ps.0202302 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jutras B. L., Bowman A., Brissette C. A., Adams C. A., Verma A., Chenail A. M., et al. (2012). EbfC (YbaB) is a new type of bacterial nucleoid-associated protein and a global regulator of gene expression in the Lyme disease spirochete. J. Bacteriol. 194 3395–3406. 10.1128/JB.00252-12 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kamashev D., Rouviere-Yaniv J. (2000). The histone-like protein HU binds specifically to DNA recombination and repair intermediates. EMBO J. 19 6527–6535. 10.1093/emboj/19.23.6527 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim D. E., Chivian D., Baker D. (2004). Protein structure prediction and analysis using the Robetta server. Nucleic Acids Res. 32 W526–W531. 10.1093/nar/gkh468 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Le T. B., Laub M. T. (2016). Transcription rate and transcript length drive formation of chromosomal interaction domain boundaries. EMBO J. 35 1582–1595. 10.15252/embj.201593561 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Le T. B. K., Imakaev M. V., Mirny L. A., Laub M. T. (2013). High-resolution mapping of the spatial organization of a bacterial chromosome. Science 342 731–734. 10.1126/science.1242059 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee S. F., Thompson M. A., Schwartz M. A., Shapiro L., Moerner W. E. (2011). Super-resolution imaging of the nucleoid-associated protein HU in Caulobacter crescentus. Biophys. J. 100 L31–L33. 10.1016/j.bpj.2011.02.022 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lim K., Tempczyk A., Parsons J. F., Bonander N., Toedt J., Kelman Z., et al. (2002). Structure note crystal structure of YbaB from Haemophilus influenzae (HI0442), a protein of unknown function coexpressed with the recombinational DNA repair protein RecR. Proteins 50 375–379. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luscombe N. M., Laskowski R. A., Thornton J. M. (1997). NUCPLOT: a program to generate schematic diagrams of protein-nucleic acid interactions. Nucleic Acids Res. 25 4940–4945. 10.1093/nar/25.24.4940 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mahdi A. A., Lloyd R. G. (1989). The recR locus of Escherichia coli K-12: molecular cloning, DNA sequencing and identification of the gene product: thI eRlcso shrci oiK1:mlclr lnn, DAsqecn n dniiaino h. Nucleic Acids Res. 17 6781–9794. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mukherjee A., Sokunbi A. O., Grove A. (2008). DNA protection by histone-like protein HU from the hyperthermophilic eubacterium Thermotoga maritima. Nucleic Acids Res. 36 3956–3968. 10.1093/nar/gkn348 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nguyen H. H., de la Tour C. B., Toueille M., Vannier F., Sommer S., Servant P. (2009). The essential histone-like protein HU plays a major role in Deinococcus radiodurans nucleoid compaction. Mol. Microbiol. 73 240–252. 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2009.06766.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oberto J., Nabti S., Jooste V., Mignot H., Rouviere-Yaniv J. (2009). The HU regulon is composed of genes responding to anaerobiosis, acid stress, high osmolarity and SOS induction. PLoS One 4:e4367. 10.1371/journal.pone.0004367 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oliveira Paiva A. M., Friggen A. H., Qin L., Douwes R., Dame R. T., Smits W. K. (2019). The bacterial chromatin protein HupA can remodel DNA and associates with the nucleoid in Clostridium difficile. J. Mol. Biol. 431 653–672. 10.1016/j.jmb.2019.01.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paintdakhi A., Parry B., Campos M., Irnov I., Elf J., Surovtsev I., et al. (2015). Oufti: an integrated software package for high-accuracy, high-throughput quantitative microscopy analysis. Mol. Microbiol. 99 767–777. 10.1111/mmi.13264 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ricci D. P., Melfi M. D., Lasker K., Dill D. L., McAdams H. H., Shapiro L. (2016). Cell cycle progression in Caulobacter requires a nucleoid-associated protein with high AT sequence recognition. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 113 E5952–E5961. 10.1073/pnas.1612579113 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Riley S. P., Bykowski T., Cooley A. E., Burns L. H., Babb K., Brissette C. A., et al. (2009). Borrelia burgdorferi EbfC defines a newly-identified, widespread family of bacterial DNA-binding proteins. Nucleic Acids Res. 37 1973–1983. 10.1093/nar/gkp027 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schindelin J., Arganda-Carreras I., Frise E., Kaynig V., Longair M., Pietzsch T., et al. (2012). Fiji: an open-source platform for biological-image analysis. Nat. Methods 9 676–682. 10.1038/nmeth.2019 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shindo H., Furubayashi A., Shimizu M., Miyake M., Imamoto F. (1992). Preferential binding of E.coli histone-like protein HU alpha to negatively supercoiled DNA. Nucleic Acids Res. 20 1553–1558. 10.1093/nar/20.7.1553 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Simon R., Priefer U., Pühler A. (1983). A broad host range mobilization system for in vivo genetic engineering: transposon mutagenesis in gram negative bacteria. Nat. Biotechnol. 1 784–791. 10.1038/nbt1183-784 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Song Y., DiMaio F., Wang R. Y.-R., Kim D., Miles C., Brunette T., et al. (2013). High-resolution comparative modeling with RosettaCM. Structure 21 1735–1742. 10.1016/j.str.2013.08.005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stove Poindexter’ J. (1964). Biological properties and classification of the Caulobacter group. Bacteriol. Rev. 28 231–295. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Taylor J. A., Panis G., Viollier P. H., Marczynski G. T. (2017). A novel nucleoid-associated protein coordinates chromosome replication and chromosome partition. Nucleic Acids Res. 45 8916–8929. 10.1093/nar/gkx596 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Teotia D., Gaid M., Saini S. S., Verma A., Yennamalli R. M., Khare S. P., et al. (2019). Cinnamate-CoA ligase is involved in biosynthesis of benzoate-derived biphenyl phytoalexin in Malus 3 domestica “Golden Delicious” cell cultures. Plant J. 100 1176–1192. 10.1111/tpj.14506 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thanbichler M., Iniesta A. A., Shapiro L. (2007). A comprehensive set of plasmids for vanillate-and xylose-inducible gene expression in Caulobacter crescentus. Nucleic Acids Res. 35:e137. 10.1093/nar/gkm818 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van Zundert G. C. P., Rodrigues J. P. G. L. M., Trellet M., Schmitz C., Kastritis P. L., Karaca E., et al. (2016). The HADDOCK2.2 web server: user-friendly integrative modeling of biomolecular complexes. J. Mol. Biol. 428 720–725. 10.1016/j.jmb.2015.09.014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang H., Wang F., Hua X., Ma T., Chen J., Xu X., et al. (2012). Genetic and biochemical characteristics of the histone-like protein DR0199 in Deinococcus radiodurans. Microbiology 158 (Pt 4) 936–943. 10.1099/mic.0.053702-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yeung’ T., Mullin D. A., Chen K.-S., Craig E. A., Bardwell J. C. A., Walker’ J. R. (1990). Sequence and expression of the Escherichia coli recR locus. J. Bacteriol. 172 6042–6047. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article/Supplementary Material, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author/s.