Abstract

Ultraviolet photoacoustic microscopy (UV-PAM) has been investigated to provide label-free and registration-free volumetric histological images for whole organs, offering new insights into complex biological organs. However, because of the high UV absorption of lipids and pigments in tissue, UV-PAM suffers from low image contrast and shallow image depth, hindering its capability for revealing various microstructures in organs. To improve the UV-PAM imaging contrast and imaging depth, here we propose to implement a state-of-the-art optical clearing technique, CUBIC (clear, unobstructed brain/body imaging cocktails and computational analysis), to wash out the lipids and pigments from tissues. Our results show that the UV-PAM imaging contrast and quality can be significantly improved after tissue clearing. With the cleared tissue, multilayers of cell nuclei can also be extracted from time-resolved PA signals. Tissue clearing-enhanced UV-PAM can provide fine details for organ imaging.

Keywords: Photoacoustic microscopy, Label-free imaging, Tissue clearing, Volumetric imaging

1. Introduction

Three-dimensional (3D) imaging of whole organs with high spatial resolution reveals microstructures of biological tissues, which is essential to understand the structures and functions of both healthy and diseased organs [1], [2], [3], [4]. Recently, microtomy-assisted photoacoustic microscopy (mPAM) with ultraviolet (UV) excitation has been developed to generate label-free 3D histological images of whole organs, offering a new way to apply histopathological interpretation from organelle to organ levels [5]. In mPAM, PA signals are induced by the thermal-elastic expansion of intrinsic chromophores which absorb part of the photon energy of incoming laser pulses [6]. Since DNA/RNA in cell nuclei have a high absorption coefficient on the UV range (e.g., 266 nm) [7], UV-PAM provides histological images by highlighting cell nuclei for whole-organ imaging without any staining. While in most fluorescence-based optical microscopies, time-consuming pre-staining for whole organs is generally required, which could cause non-uniform staining and eventually affect the image quality [8]. Moreover, with mPAM, an accurate 3D image of a whole organ can be reconstructed by stacking all 2D images without image registration, eliminating the undesired image distortion due to registration error [5].

Despite the 3D imaging capability of mPAM has been demonstrated for several organs, the contrast of cell nuclei is relatively low, especially in the organs with a high concentration of lipids and pigments (such as in the kidney) [5], which hinders mPAM to reliably reveal cell morphological information in different organs. As cell morphology is one of the most important indicators for disease diagnosis [9], [10] (e.g., cancer grading), the performance of mPAM should be further improved to broaden its application in life science studies. As lipids and pigments have a relatively high absorption coefficient at UV range (266 nm) [7], their generated PA signals are comparable to those generated from cell nuclei, thus leading to a significant background in UV-PAM cellular imaging. Besides, lipids can cause significant light scattering because of the refractive index mismatch [11]. Both optical absorption and light scattering limit the imaging depth of UV-PAM [12]. As a result, more sectioning slices are required to obtain a 3D image of the whole organ. Hence, lipids and pigments can be considered as barriers to UV-PAM for whole-organ imaging.

Similar to UV-PAM, the imaging depth of optical fluorescence microscopy is also hindered by optical absorption and scattering of lipids and pigments. To increase the imaging depth, a series of tissue clearing methods have been developed to achieve high tissue transparency by removing lipids and pigments, and homogenizing refractive indices (RIs), which enable optical fluorescence microscopy (e.g., light-sheet microscopy and multi-photon microscopy) to provide volumetric images of whole organs [11], [13], [14], [15]. These tissue clearing methods are also possible to improve cellular imaging contrast and imaging depth of UV-PAM, which, however, has not yet been studied. A recent demonstration with tissue expansion technique has achieved relatively transparent tissue slices, proving hyper resolution and improving imaging depth [16]. However, lipids and pigments cannot be removed by the tissue expansion hydrogel, especially for whole organs. Here, we investigate the potential of using CUBIC (clear, unobstructed brain/body imaging cocktails and computational analysis) as a tissue clearing method for UV-PAM, which has been proved as an efficient optical clearing method for optical microscopy [11]. To evaluate the effectiveness of CUBIC for UV-PAM, we have imaged and compared biological tissues with and without CUBIC treatment. The experimental results show that most lipids and pigments are washed out from the tissues treated with CUBIC. Subsequently, the UV-PAM image contrast is significantly improved and, the imaging depth is increased. Both qualitative and quantitative analyses have been applied to validate the effectiveness of tissue clearing-enhanced UV-PAM for organ imaging.

2. Materials and methods

2.1. Protocols of CUBIC

The protocols of CUBIC performed in this paper followed the advanced CUBIC protocol in Ref. [11] with minor adjustments. The proposed protocol consists of five buffers, (1) 3.7% paraformaldehyde (PFA) in deionized water solution, (2) 3.7% PFA in phosphate buffered saline (PBS) solution, (3) PBS solution, (4) PBS/0.01% (wt/vol) in sodium azide solution, and (5) ½-PBS-diluted glycerol, and two clearing reagents, (i) ScaleCUBIC-1 and (ii) ScaleCUBIC-2. ScaleCUBIC-1 is made of 20% cocktail of urea (25% wt/vol), quadrol (25% wt/vol), Triton-X-100 (20% wt/vol), and deionized water (30% wt/vol). ScaleCUBIC-2 is made of urea (25% wt/vol), sucrose (50% wt/vol), triethanolamine (10% wt/vol), and deionized water (15% wt/vol).

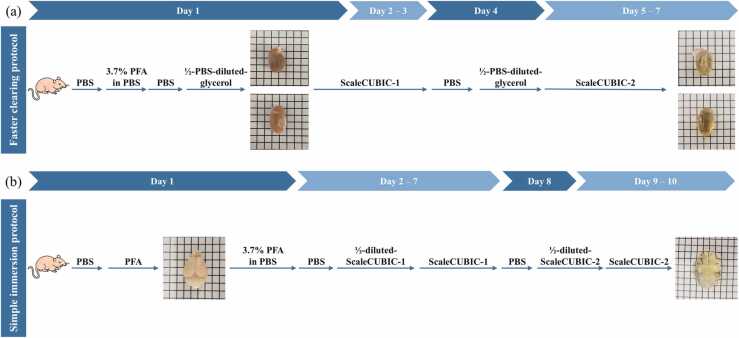

Two tissue clearing protocols, which are fast clearing and simple immersion protocols [11], were performed in this work based on the target organs. All mice were anesthetized by injecting a mixed ketamine (10%) and xylazine (2%) solution before clearing procedures. All the protocols are approved by the Animal Ethics Committee at The Hong Kong University of Science and Technology.

2.1.1. Fast clearing protocol for kidneys and hearts

As shown in Fig. 1(a), an anesthetized mouse was first perfused with buffers in the sequence of 20 ml of cold (~ 0 °C) PBS, 150 ml of cold (~ 0 °C) 3.7% PFA in PBS, 20 ml of cold (~ 0 °C) PBS, and 20 ml of ½-water-diluted ScaleCUBIC-1. Mouse heart and kidney were then harvested and immersed in ScaleCUBIC-1 for three days. Replacement of old ScaleCUBIC-1 with fresh one was performed on the second day of the immersion. Subsequently, the organs were washed three times with PBS with a two-hour interval, and further immersed with ½-PBS-diluted glycerol for six hours. Finally, the treated organs were immersed with fresh ScaleCUBIC-2 for three days before imaging.

Fig. 1.

Two protocols of CUBIC. (a) Fast clearing protocol for mouse kidneys and hearts. (b) Simple immersion protocol for mouse brains.

2.1.2. Simple immersion protocol for brains

As shown in Fig. 1(b), an anesthetized mouse was first perfused with 10 ml of PBS solution and 25 ml of cold (~ 0 °C) PFA solution at 10 ml/min. The mouse brain was then harvested, fixed in PFA solution for 24 h, and washed with PBS/0.01% (wt/vol) sodium azide twice with a two-hour interval. Subsequently, the washed mouse brain was pretreated with ½-water-diluted ScaleCUBIC-1, and was further immersed in fresh ScaleCUBIC-1 for six days. To remove residual ScaleCUBIC-1, the mouse brain was washed with PBS solution three times (after two hours, overnight, and another two hours). Finally, the sample was immersed in ½-water-diluted ScaleCUBIC-2 for six hours, followed by two days immersion in ScaleCUBIC-2.

2.2. Sample preparation for UV-PAM imaging

In this paper, we focus on investigating the effectiveness of applying the tissue clear method (CUBIC) for UV-PAM imaging. For idea demonstration, we used tissue slices instead of whole organs for imaging. Tissue slices were sectioned at the middle of the organs to show the clearing effectiveness.

The validation involves two stages: thin slice clearing and intact organ clearing. For thin slice clearing, a 400-μm-thick kidney slice sectioned from a formalin-fixed kidney was first imaged by our UV-PAM system to obtain an ordinary UV-PAM image (i.e., without clearing). The kidney slice was then processed following the fast-clearing protocol described in Section 2.1. After being cleared, the same kidney slice was imaged again to obtain an optically cleared UV-PAM image. Lastly, the image contrasts of the UV-PAM images before and after clearing of the same kidney slice were compared. For intact organ clearing, the whole mouse kidney, heart, and brain were cleared following the CUBIC protocols, and then sectioned into slices with a thickness of ~ 400 µm. The tissue slices were imaged by our UV-PAM system to evaluate whether the image quality is enhanced by tissue clearing. To quantify the image quality, contrast-to-noise ratio (CNR) is used as a metric for comparison, which is defined as

where and are the amplitude of PA signals generated from cell nuclei and their surrounding background (lipids and pigments), respectively. is the standard deviation of noise in the background.

2.3. UV-PAM system

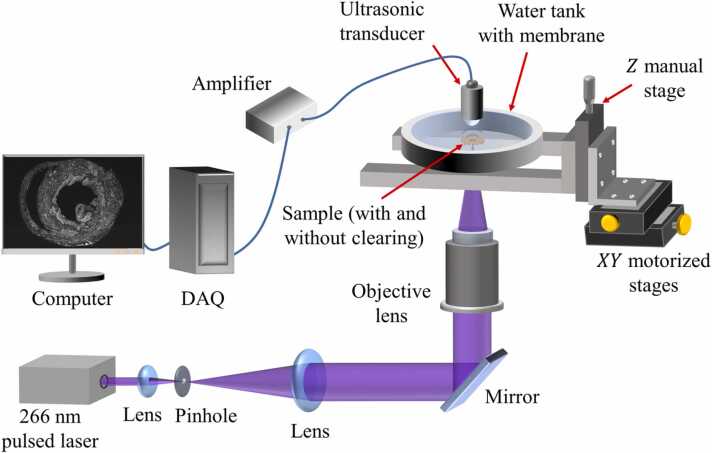

The schematic of the UV-PAM system is shown in Fig. 2. A nanosecond UV pulsed laser (266 nm wavelength, WEDGE HF 266 nm, Bright Solutions Srl., operating at 16 kHz) is first expanded by a pair of plano-convex lenses (LA-4600-UV and LA4663-UV, Thorlabs Inc.) and spatially filtered by a pinhole (50 µm in diameter, #59–257, Edmund Optics Inc.). The beam is then reflected upward by a mirror and focused on a specimen (with and without clearing) by an objective lens (LMU-5X-NUV, numerical aperture (NA) = 0.12, Thorlabs Inc.) to excite PA signals. The specimen is placed on a quartz coverslip, then the specimen and coverslip are sandwiched in the water tank with two membranes. The water tank is filled with water for acoustic wave propagation so that the excited PA waves can be detected by an ultrasonic transducer (V324-SU, 50 MHz central frequency, 6 mm focal length, Olympus DNT Inc.). The ultrasonic signals are then amplified by amplifiers (56 dB, two ZFL-500LN-BNC+, Mini-circuit Inc) and digitized by a data acquisition card (ATS9350, Alazar Technologies Inc.). Two motorized stages (L-509.10SD00, PI (Physik Instrumente) Singapore LLP) translate the sample in the - and -axis for raster scanning.

Fig. 2.

Schematic of the UV-PAM system. DAQ, data acquisition card.

3. Results

3.1. Organs before and after clearing

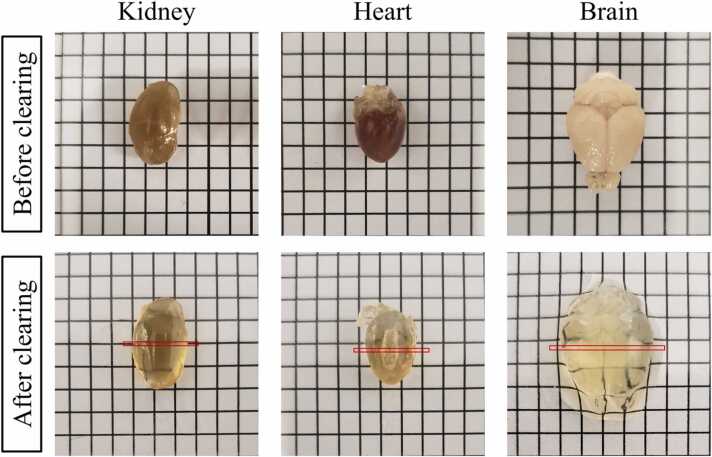

Fig. 3 shows the comparison of organs (kidney, heart, and brain) before and after clearing. As expected, organs are much more transparent after clearing because of the removal of lipids and pigments. The red marked regions on the cleared organs are the approximate regions where the sample slices are sectioned at for UV-PAM imaging.

Fig. 3.

Mouse kidney, heart, and brain before and after clearing.

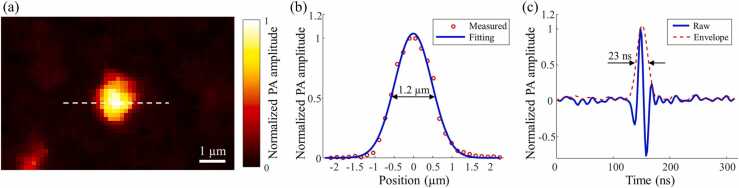

3.2. System resolution measurement

Gold nanoparticles (200 nm in diameter) were imaged by the UV-PAM system to measure the spatial resolution. A UV-PAM image of a gold nanoparticle is shown in Fig. 4(a), and the red circles in Fig. 4(b) are the data along the white dotted line in Fig. 4(a). The measured data are then fitted by a Gaussian function, shown as the blue solid line in Fig. 4(b). Subsequently, the full width at half maximum (FWHM) of the fitted Gaussian function was calculated to estimate the lateral resolution. The experimental lateral resolution is ~ 1.2 µm, which is close to the theoretical resolution, with an effective NA of ~ 0.12.

Fig. 4.

Resolution measurement of the UV-PAM system. (a) A UV-PAM image of a gold nanoparticle. (b) and (c) Plots showing the lateral resolution and axial resolution measurements, respectively.

Axial resolution was measured by the extracted envelope of the A-line PA signal, which was generated from the center of the gold nanoparticle. The result is shown in Fig. 4(c) and the FWHM of the envelope is ~ 23 ns. Thus, the axial resolution was calculated to be ~ 34 µm, assuming the speed of sound equals ~ 1480 m/s.

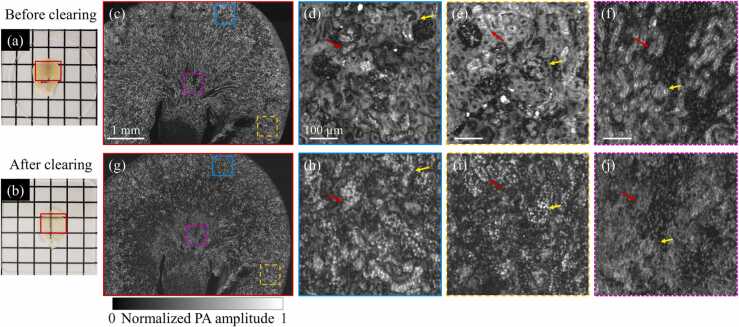

3.3. UV-PAM imaging of a mouse kidney slice without and with tissue clearing

To identify the effect of clearing-enhanced UV-PAM, images of a mouse kidney slice before and after tissue clearing were obtained for comparison. A formalin-fixed kidney slice (Fig. 5(a)) is first imaged by the UV-PAM system, as shown in Fig. 5(c). Fig. 5(d)–(f) show the zoomed-in images of the corresponding regions marked in Fig. 5(c). However, these zoomed-in images show a relatively low image contrast, causing indistinguishable cell nuclei in most regions. The low image contrast can be attributed to the high surrounding background signals generated from lipids and pigments. Contrast-to-noise ratios (CNRs) of Fig. 5(d)–(f) (slices without clearing) are calculated as 8.0, 4.2, and 6.2, respectively, under a pulse energy of 5 nJ.

Fig. 5.

A comparison of a mouse kidney slice without and with tissue clearing. (a) and (b) Photographs of a kidney slice before and after clearing, respectively. (c) A UV-PAM image of a kidney slice before clearing. (d)–(f) Zoomed-in images of the corresponding regions marked in (c), with scale bars: 100 µm. (g) A UV-PAM image of the same kidney slice after clearing. (h)–(j) Zoomed-in images of the corresponding regions marked in (g).

The same fixed kidney slice was then treated following the clearing steps of the fast-clearing protocol present in Section 2.1. As shown in Fig. 5(b), the slice becomes transparent after clearing, which indicates most lipids and pigments are removed from the slice. Subsequently, the cleared slice was imaged again by the UV-PAM system, as shown in Fig. 5(g). For comparison, the regions corresponding to Fig. 5(d)–(f) are zoomed in and shown in Fig. 5(h)–(j), respectively. Most individual cell nuclei can be resolved in the cleared slice. The cell nuclei on the regions marked by the red and yellow arrays in Fig. 5(h)–(j) can be clearly identified after clearing, while they cannot be distinguished from the surrounding tissue before clearing (Fig. 5(d)–(f)). The CNRs of the corresponding cleared regions are 41.4, 35.3, and 26.0, respectively, under a pulse energy of 6.25 nJ. For a fair comparison, the CNR enhancement after tissue clearing are 4.1, 6.7, and 3.4 times, respectively, after pulse energy normalization. The qualitative and quantitative results indicate that tissue clearing can significantly improve cellular imaging contrast of UV-PAM for tissue imaging, allowing previously indistinguishable cell nuclei (before clearing) to be visualized (after clearing).

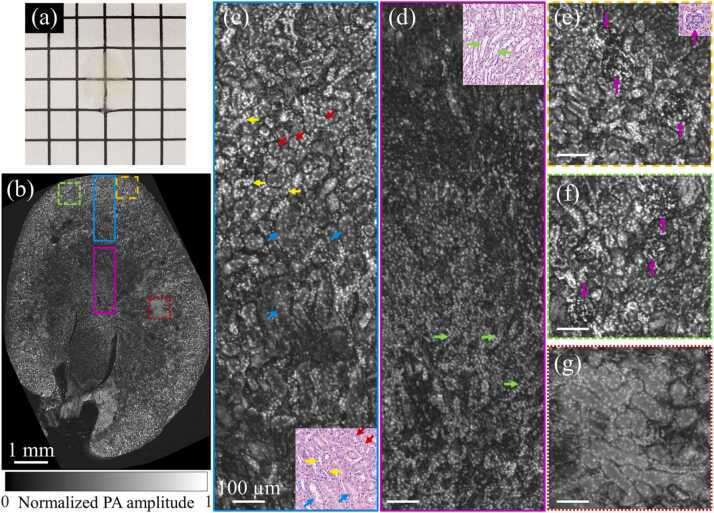

To validate the performance of clearing-enhanced UV-PAM for whole kidney imaging, a slice at the middle of an intact and cleared kidney (shown in Fig. 3) was sectioned and imaged, which also followed the steps of the fast-clearing protocol. From a macroscopic level, the cleared kidney slice was almost totally optical transparent (Fig. 6(a)). To analyze the results microscopically, a UV-PAM image of the slice is obtained (Fig. 6(b)) and zoomed-in images are shown in Fig. 6(c)–(g). Remarkably, we can see that from the cortex to the medulla of the kidney (Fig. 6(c) and (d)), individual cell nuclei can be resolved and identified from the connective tissue. The distribution of cell nuclei in the loops of Henle (red arrows), distal convoluted tubules (yellow arrows), and proximal convoluted tubules (blue arrows) can be clearly observed in Fig. 6(c). The distribution of the cell nuclei in renal medullas (green arrows) in Fig. 6(d) shows a striped shape, which is consistent with the histological stained image [17]. In Fig. 6(e) and (f), the structure of glomeruli (purple arrows) can be clearly identified. Moreover, all these arrows marked structures on UV-PAM images can be found on the hematoxylin and eosin (H&E) stained images of a kidney slice, indicating that our tissue clearing-enhanced UV-PAM can provide histological images that are similar to regular histology staining results.

Fig. 6.

UV-PAM imaging of kidney slice sectioned from a cleared kidney. (a) A photograph of a kidney slice. (b) A UV-PAM image of the kidney slice. (c)–(g) Zoomed-in images of the corresponding marked regions in (b), with scale bars: 100 µm. A kidney slice is stained by H&E and shown at the corner of (c)–(e) for comparison.

Although Fig. 6(g) shows a region with relatively low image contrast mainly because of the residual lipids in tissue, the cell nuclei can still be distinguished from the connective tissue in tubules. The CNRs for Fig. 6(c)–(g) are 46.9, 38.3, 50.9, 51.7, and 31.7, respectively, under a pulse energy of 6.25 nJ. Compared with the kidney slice shown in Fig. 5(c) (without clearing), the average CNR enhancement by tissue clearing reaches 5.7 times after pulse energy normalization. With the high CNRs, clearing-enhanced UV-PAM allows high-contrast cellular imaging for biological organs.

The results in this section validate that tissue clearing can significantly improve the UV-PAM image contrast for kidneys. Individual cell nuclei can be observed throughout the slice, and the microstructures of the kidney can be clearly revealed.

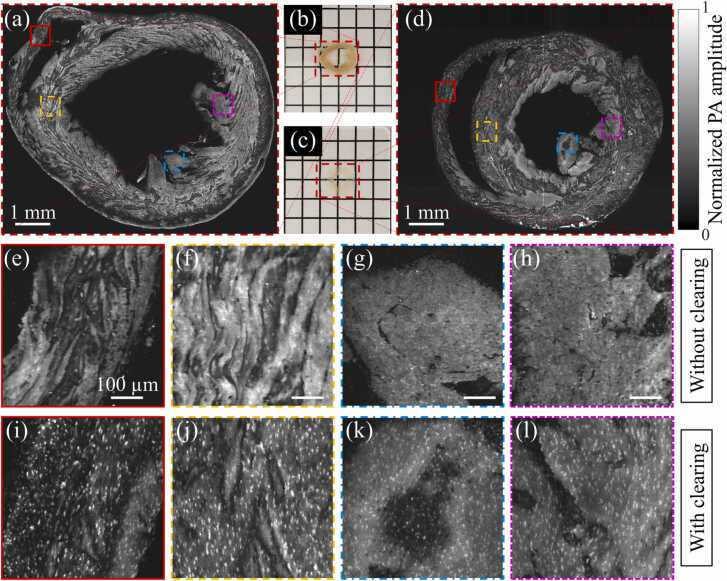

3.4. UV-PAM imaging of a mouse heart slice without and with tissue clearing

To further study the performance of clearing-enhanced UV-PAM imaging for other organs, mouse heart slices without and with clearing (Fig. 7(b) and (c)) are imaged for comparison. The slice without clearing was cut from a formalin-fixed mouse heart, while the slice with clearing was sectioned from the intact and cleared mouse heart (shown in Fig. 3). Their UV-PAM images are shown in Fig. 7(a) and (d), and four regions are zoomed in (Fig. 7(e)–(l)) for comparison. Similar to the kidney tissue without clearing, the cell nuclei are difficult to be visualized in the heart slice without clearing (Fig. 7(e)–(h)) because of the strong background generated from lipids and pigments. The CNRs for Fig. 7(e)–(h) are 10.1, 14.9, 10.9, and 12.3, respectively, under a pulse energy of 5 nJ. On the contrary, more distinct cell nuclei can be resolved in the heart slice with clearing (Fig. 7(i)–(l)), even in the inner regions (Fig. 7(k) and (l)) where contain more residual lipid and pigments. The CNRs for Fig. 7(i)–(l) are 65.0, 60.7, 43.7, and 48.7, respectively, under a pulse energy of 6.25 nJ, indicating that high image quality can be obtained by the clearing-enhanced UV-PAM. After similar pulse energy normalization, the CNR enhancement by tissue clearing are 5.1, 3.3, 3.2, and 3.2 times, respectively, showing great promise of the proposed clearing method.

Fig. 7.

A comparison of a mouse heart slice without and with tissue clearing. (a) and (b) A UV-PAM image and photograph of a formalin-fixed mouse heart slice without clearing, respectively. (c) and (d) A photograph and UV-PAM image of a heart slice sectioned from a cleared heart, respectively. (e)–(h) Zoomed-in images of the corresponding marked regions in (a), with scale bars: 100 µm. (i)–(l) Zoom-in images of the corresponding marked regions in (d).

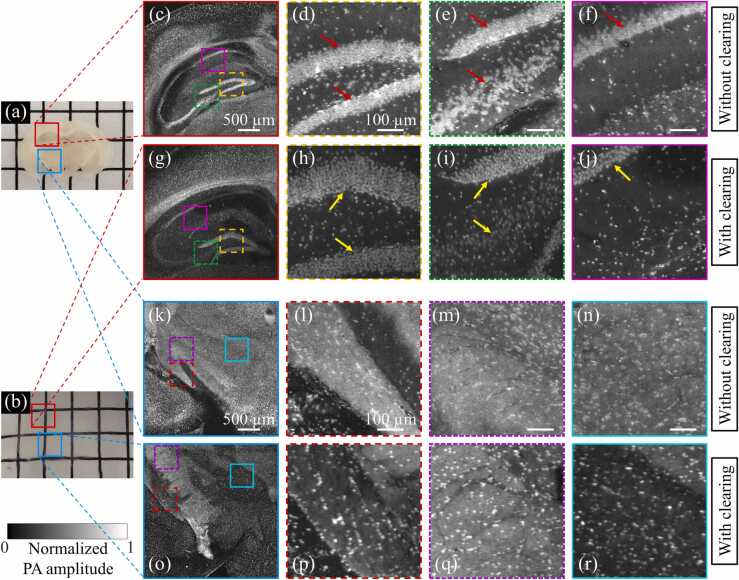

3.5. UV-PAM imaging of a mouse brain slice without and with tissue clearing

Revealing 3D histological information of a whole mouse brain is important due to the clinically translatable insights into human neurological diseases [18]. Although a previous study demonstrated the performance of UV-PAM imaging for a whole formalin-fixed mouse brain [5], the image quality can be further improved with our proposed tissue clearing. Photographs of mouse brain slices without and with tissue clearing are shown in Fig. 8(a) and (b), respectively. The slice without clearing was cut from a formalin-fixed mouse brain, while the slice with clearing was sectioned from the intact and cleared mouse brain (shown in Fig. 3). We can observe that the slice with clearing is close to complete optically transparent because of the lipid removal. Fig. 8(c) shows a UV-PAM image of the hippocampus region of the slice without clearing, where the cell nuclei are dense. Zoomed-in images of the corresponding marked regions in Fig. 8(c) are shown in Fig. 8(d)–(f). Because of the high density of cell nuclei, individual cell nuclei in the hippocampus (red arrows) cannot be resolved. While in the image of the mouse brain slice with clearing (Fig. 8(g)) and its zoomed-in images (Fig. 8(h)–(j)) show distinguishable single cell nucleus in the hippocampus (yellow arrows). Apart from the image contrast improvement, tissue expansion (~ 120%) after clearing would be another reason for the visualization of individual cell nuclei in the hippocampus region [19]. Therefore, super resolution was simultaneously achieved, resolving high-density cell nuclei. The concept of using tissue expansion to achieve super resolution in UV-PAM was also reported recently [16], which is consistent with our results.

Fig. 8.

A comparison of a mouse brain slice without and with tissue clearing. (a) A slice sectioned from a formalin-fixed mouse brain without clearing. (b) A slice sectioned from an intact and cleared mouse brain. (c) and (k) UV-PAM images of the corresponding marked regions in (a). (d)–(f) and (l)–(n) Zoomed-in images of corresponding marked regions in (c) and (k), respectively, with scale bars: 100 µm. (g) and (o) UV-PAM images of the corresponding marked regions in (b). (h)–(j) and (p)–(r) Zoomed-in images of corresponding marked regions in (g) and (o), respectively.

Fig. 8(k) shows a UV-PAM image of the blue-marked region of the mouse brain slice without clearing (Fig. 8(a)), which has a large amount of lipids. Similar region in the cleared slice is also imaged for comparison, as shown in Fig. 8(o). We can see that the image of the mouse brain slice with clearing has clearer background than the one without clearing. The zoomed-in images of the corresponding marked regions in Fig. 8(k) and (o) are shown in Fig. 8(l)–(n) and Fig. 8(p)–(r), respectively. Although some of the cell nuclei in the slice without clearing (Fig. 8(l)–(n)) can be identified from the strong lipid background, the image contrast is relatively low. While in the images of the cleared slice (Fig. 8(p)–(r)), cell nuclei are more clearly observed. The CNRs in Fig. 8(l)–(n) under 7.4 nJ pulse energy are 22.2, 18.8, and 21.1, respectively, while the CNRs in Fig. 8(p)–(r) under 10.6 nJ are 94.1, 69.5 and 78.7, respectively. Similarly, for fair comparison, we have normalized the pulse energy. The resulting CNR enhancement by tissue clearing are 3.0, 2.6, and 2.6 times, respectively. The UV-PAM images for slices with clearing have much higher CNR than those without clearing. We can conclude that lipid removal in the mouse brain can remarkably improve the UV-PAM image quality.

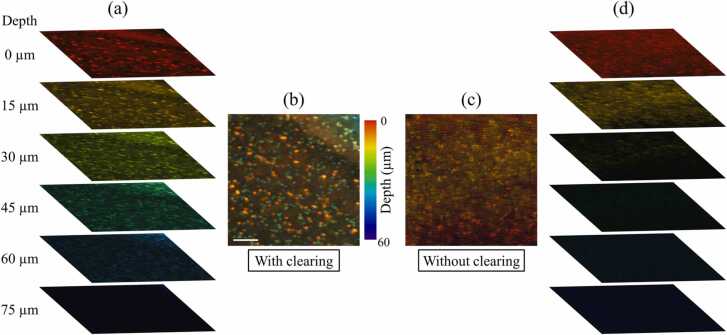

Since most of the lipids are removed in the cleared organs, the imaging depth of UV-PAM is expected to be increased. To validate our hypothesis, we have extracted six different depths with an interval of 15 µm (about half of the axial resolution) from the depth-resolved PA signals of the cleared region (Fig. 8(r)), which is shown in Fig. 9(a). Although the imaging depth could also be limited by the depth-of-focus of the Gaussian beam, an imaging depth of ~ 60 µm is obtained based on the observation of differently distributed cell nuclei (Fig. 9(a)). To reveal the depth information of cell nuclei, we also provided the depth-encoded image of these six image stacks, as shown in Fig. 9(b). For comparison, image stacks of a similar region without clearing (Fig. 8(n)) are also extracted, as shown in Fig. 9(c) and (d). However, only the top three image stacks show sufficient PA signals, indicating that the imaging depth is ~ 30 µm, which is much shallower than that of the cleared slices. By comparing the depth-encoded images (Fig. 9(b) and (c)), multilayers of cell nuclei can be observed with high image contrast in the cleared mouse brain slice. Therefore, clearing-enhanced UV-PAM imaging not only improves the image contrast but also increases the imaging depth.

Fig. 9.

Depth-resolved image comparison of the mouse brain slice with and without clearing. (a) and (b) Image stacks and depth-encoded image of the mouse brain slice with clearing, respectively. Scale bar: 100 µm. (c) and (d) Depth-encoded image and image stacks of the mouse brain slice without clearing, respectively.

4. Discussion

In this paper, we have demonstrated the effectiveness of applying CUBIC into UV-PAM. In fact, more tissue optical clearing methods, including TDE [20], FDISCO [21], and FRUIT [22], have also been tested (Supplementary Fig. 1). However, the organs after TDE and FDISCO treatment are hard, which would cause high attenuation to the PA signals propagating out from organs. Organs with FRUIT clearing show low transparency when compared with CUBIC. Based on our current investigation, we found that CUBIC performs the best in tissue clearing-enhanced UV-PAM. Although remarkable imaging results were shown in this paper, the optical clearing effect of CUBIC might be further optimized for UV-PAM imaging. New tissue clearing methods specific for UV-PAM imaging can also be explored.

Currently, the demonstrated clearing-enhanced UV-PAM images are for tissue slices only. In future work, it is possible to integrate a vibratome sectioning machine for whole-organ imaging. Although the imaging depth is shown to be ~60 µm which is limited by the depth-of-focus of the Gaussian-shaped UV excitation beam and the detection sensitivity of the ultrasonic transducer, the UV light can penetrate deeper into the cleared tissue as expected (> 200 µm, as shown in Supplementary Fig. 2) due to the high transparency. Therefore, multiple layers of cell nuclei can be extracted by scanning the samples along the -axis [23]. With the higher penetration depth of UV light in cleared tissues, less sectioning is required to obtain a whole-organ 3D image, thus, improving the overall imaging speed. To perform whole-organ imaging, a reflection-mode UV-PAM can be implemented by using a ring-shaped ultrasonic transducer [5] or opto-ultrasonic combiner [24], [25]. Besides, as a non-contact PA imaging technique, UV photoacoustic remote sensing (UV-PARS) which directly detects initial PA pressure in tissue by recording the reflectance changes of an additional interrogation beam [26], [27], can be also explored for whole-organ imaging with tissue clearing to make the system more flexible. Although the imaging depth can be improved by tissue clearing, the current axial resolution of the UV-PAM system is not sufficient to resolve every cell nucleus along the depth. To provide high-resolution 3D images of whole organs, the axial resolution of the UV-PAM system could be further improved by dual-view excitation [28], Grüneisen relaxation [29], [30], or PARS [31]. With these further improvements, a clearing-enhanced UV-PAM system can provide fine cellular information with intrinsic absorption contrast for whole-organ imaging, being a promising tool to better understand the structures and functions of both healthy and disease organs.

5. Conclusion

To conclude, the proposed clearing-enhanced UV-PAM system has significantly improved the imaging contrast for different biological organs. Especially in the organs that contain a high concentration of lipids and pigments (such as kidney and heart), previously indistinguishable cell nuclei are revealed with high image contrast after clearing. Besides, the super resolution caused by organ expansion after clearing allows the identification of individual cell nuclei in dense regions. In addition to the imaging contrast improvement, the imaging depth also increased because of less optical absorption and scattering by lipids and pigments. To the best of our knowledge, it is the first time to demonstrate the tissue clearing effects in UV-PAM. Clearing-enhanced UV-PAM can reveal fine details of microstructures for organ imaging.

Funding

Research Grants Council of the Hong Kong Special Administrative Region (16208620); Hong Kong Innovation and Technology Commission (ITS/036/19).

Disclosures

T. T. W. W. and V. T. C. T. have a financial interest in PhoMedics Limited, which, however, did not support this work. The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Declaration of Competing Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Biographies

Xiufeng Li is currently a Ph.D. candidate in Bioengineering at The Hong Kong University of Science and Technology (HKUST). He received his B.S. in Physics from South China University of Technology and M.S. in Bioengineering from HKUST. His research interests are in the design and development of practical photoacoustic imaging systems for clinical and pre-clinical applications.

Jack C.K. Kot is currently an M.Phil. student in Bioengineering at The Hong Kong University of Science and Technology(HKUST). He received his B.S. in Chemical and Biomolecular Engineering from HKUST. His research interests are multiplexed virtual staining and tissue optical clearing.

Victor T.C. Tsang obtained his B.Sc in Chemistry in 2019 and M.Phil. in Bioengineering in 2021 in HKUST. He is currently a Ph.D. student in the Department of Chemical and Biological Engineering at HKUST, majoring in bioengineering under the support of Hong Kong Ph.D. Fellowship scheme. His research interests are mainly on developing safe contrast agents for different imaging modalities.

Bingxin Huang obtained her B.Sc in Biomedical Engineering in 2020 at Xi’an Jiaotong University. She is currently an M.Phil. student, majoring in Bioengineering, under the Department of Chemical and Biological Engineering at HKUST. Her research interests are mainly on smartphone-based translational biomedical imaging techniques.

Ye Tian is a Ph.D. student at the Hong Kong University of Science & Technology (HKUST) under the supervision of Prof. Yoonseob KIM. He received his bachelor’s and master’s degrees from Taiyuan University of Technology (2018) and HKUST (2020), respectively. His current research interests focus on crystalline porous organic polymers (Covalent organic frameworks) design, synthesis, and applications for energy related materials.

Ivy H.M. Wong received her B.Eng. degree in Chemical and Biomolecular Engineering at HKUST in 2019. She is currently a Ph.D. candidate in Bioengineering at HKUST. She has received a Research Studentship 2021/2022 and the award of Butterfield-Croucher Studentship from the Croucher Foundation as the best candidate in the category of Medical and Biological Sciences for 2021/2022. Her research focuses on developing imaging modalities for intraoperative clinical applications.

Lei Kang received his bachelor’s degree in Mechanical Engineering from Chongqing University. He received his master’s degree in Bioengineering at Hong Kong University of Science and Technology. He is currently a Ph.D. candidate in Bioengineering at Hong Kong University of Science and Technology. His research areas center on applying deep learning algorithms in different medical imaging modalities.

Terence T.W. Wong received his B.Eng. and M.Phil. degrees both from the University of Hong Kong in 2011 and 2013, respectively, under the supervision of Prof. Kevin K. M. Tsia. He studied in Biomedical Engineering at Washington University in St. Louis (WUSTL) and Medical Engineering at California Institute of Technology (Caltech), under the tutelage of Prof. Lihong V. Wang (member of National Academy of Engineering) for his Ph.D. degree. He is now an Assistant Professor at the Hong Kong University of Science and Technology (HKUST) under the Department of Chemical and Biological Engineering (CBE). His research focuses on developing optical and photoacoustic devices to enable label-free and high-speed histology-like imaging, three-dimensional whole-organ imaging, and low-cost deep tissue imaging. He is an author or co-author of over 40 publications in peer-reviewed journals, conference papers, and book chapters.

Footnotes

Supplementary data associated with this article can be found in the online version at doi:10.1016/j.pacs.2021.100313.

Appendix A. Supplementary material

Supplementary material

.

References

- 1.Murray E., Cho J.H., Goodwin D., Ku T., Swaney J., Kim S.Y., Choi H., Park Y.G., Park J.Y., Hubbert A., McCue M., Vassallo S., Bakh N., Frosch M.P., Wedeen V.J., Seung H.S., Chung K. Simple, scalable proteomic imaging for high-dimensional profiling of intact systems. Cell. 2015;163(6):1500–1514. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2015.11.025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Chung K., Wallace J., Kim S.Y., Kalyanasundaram S., Andalman A.S., Davidson T.J., Mirzabekov J.J., Zalocusky K.A., Mattis J., Denisin A.K., Pak S., Bernstein H., Ramakrishnan C., Grosenick L., Gradinaru V., Deisseroth K. Structural and molecular interrogation of intact biological systems. Nature. 2013;497(7449):332–337. doi: 10.1038/nature12107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kubota S.I., Takahashi K., Nishida J., Morishita Y., Ehata S., Tainaka K., Miyazono K., Ueda H.R. Whole-body profiling of cancer metastasis with single-cell resolution. Cell Rep. 2017;20(1):236–250. doi: 10.1016/j.celrep.2017.06.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Tanaka N., Kanatani S., Tomer R., Sahlgren C., Kronqvist P., Kaczynska D., Louhivuori L., Kis L., Lindh C., Mitura P., Stepulak A., Corvigno S., Hartman J., Micke P., Mezheyeuski A., Strell C., Carlson J.W., Fernández Moro C., Dahlstrand H., Östman A., Matsumoto K., Wiklund P., Oya M., Miyakawa A., Deisseroth K., Uhlén P. Whole-tissue biopsy phenotyping of three-dimensional tumours reveals patterns of cancer heterogeneity. Nat. Biomed. Eng. 2017;1(10):796–806. doi: 10.1038/s41551-017-0139-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Wong T.T.W., Zhang R., Zhang C., Hsu H.C., Maslov K.I., Wang L., Shi J., Chen R., Shung K.K., Zhou Q., Wang L.V. Label-free automated three-dimensional imaging of whole organs by microtomy-assisted photoacoustic microscopy. Nat. Commun. 2017;8(1):1386. doi: 10.1038/s41467-017-01649-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Wang L.V., Hu S. Photoacoustic tomography: in vivo imaging from organelles to organs. Science. 2012;335(6075):1458–1462. doi: 10.1126/science.1216210. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Yao J., Wang L.V. Photoacoustic microscopy. Laser Photonics Rev. 2012;7(5):1–36. doi: 10.1002/lpor.201200060. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Yun D.H., Park Y.G., Cho J.H., Kamentsky L., Evans N.B., Albanese A., Xie K., Swaney J., Sohn C.H., Tian Y., Zhang Q., Drummond G., Guan W., DiNapoli N., Choi H., Jung H.Y., Ruelas L., Feng G., Chung K. Ultrafast immunostaining of organ-scale tissues for scalable proteomic phenotyping. bioRxiv. 2019 [Google Scholar]

- 9.Zink D., Fischer A.H., Nickerson J.A. Nuclear structure in cancer cells. Nat. Rev. Cancer. 2004;4(9):677–687. doi: 10.1038/nrc1430. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Fischer E.G. Nuclear morphology and the biology of cancer cells. Acta Cytol. 2020;64(6):511–519. doi: 10.1159/000508780. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Susaki E.A., Tainaka K., Perrin D., Yukinaga H., Kuno A., Ueda H.R. Advanced CUBIC protocols for whole-brain and whole-body clearing and imaging. Nat. Protoc. 2015;10(11):1709–1727. doi: 10.1038/nprot.2015.085. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Richardson D.S., Lichtman J.W. Clarifying tissue clearing. Cell. 2015;162(2):246–257. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2015.06.067. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ertürk A., Becker K., Jährling N., Mauch C.P., Hojer C.D., Egen J.G., Hellal F., Bradke F., Sheng M., Dodt H.U. Three-dimensional imaging of solvent-cleared organs using 3DISCO. Nat. Protoc. 2012;7(11):1983–1995. doi: 10.1038/nprot.2012.119. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hama H., Kurokawa H., Kawano H., Ando R., Shimogori T., Noda H., Fukami K., Sakaue-Sawano A., Miyawaki A. Scale: a chemical approach for fluorescence imaging and reconstruction of transparent mouse brain. Nat. Neurosci. 2011;14(11):1481–1488. doi: 10.1038/nn.2928. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Tainaka K., Kubota S.I., Suyama T.Q., Susaki E.A., Perrin D., Ukai-Tadenuma M., Ukai H., Ueda H.R. Whole-body imaging with single-cell resolution by tissue decolorization. Cell. 2014;159(4):911–924. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2014.10.034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kim H., Baik J.W., Jeon S., Kim J.Y., Kim C. PAExM: label-free hyper-resolution photoacoustic expansion microscopy. Opt. Lett. 2020;45(24):6755–6758. doi: 10.1364/OL.404041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.McBride J.M. The Kidney. Springer New York; New York, NY: 2016. Embryology, anatomy, and histology of the kidney; pp. 1–18. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hafezparast M., Ahmad-Annuar A., Wood N.W., Tabrizi S.J., Fisher E.M. Mouse models for neurological disease. Lancet Neurol. 2002;1(4):215–224. doi: 10.1016/s1474-4422(02)00100-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Parra-Damas A., Saura C.A. Tissue clearing and expansion methods for imaging brain pathology in neurodegeneration: from circuits to synapses and beyond. Front. Neurosci. 2020;14 doi: 10.3389/fnins.2020.00914. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Aoyagi Y., Kawakami R., Osanai H., Hibi T., Nemoto T. A rapid optical clearing protocol using 2,2′-thiodiethanol for microscopic observation of fixed mouse brain. PLoS One. 2015;10(1) doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0116280. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Pan C., Cai R., Quacquarelli F.P., Ghasemigharagoz A., Lourbopoulos A., Matryba P., Plesnila N., Dichgans M., Hellal F., Ertürk A. Shrinkage-mediated imaging of entire organs and organisms using uDISCO. Nat. Methods. 2016;13(10):859–867. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.3964. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hou B., Zhang D., Zhao S., Wei M., Yang Z., Wang S., Wang J., Zhang X., Liu B., Fan L., Li Y., Qiu Z., Zhang C., Jiang T. Scalable and dii-compatible optical clearance of the mammalian brain. Front. Neuroanat. 2015;9:1–11. doi: 10.3389/fnana.2015.00019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Bell K., Abbasi S., Dinakaran D., Taher M., Bigras G., van Landeghem F., Mackey J.R., Haji Reza P. Reflection-mode virtual histology using photoacoustic remote sensing microscopy. Sci. Rep. 2020;10(1):1–13. doi: 10.1038/s41598-020-76155-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Baik J.W., Kim H., Son M., Choi J., Kim K.G., Baek J.H., Park Y.H., An J., Choi H.Y., Ryu S.Y., Kim J.Y., Byun K., Kim C. Intraoperative label‐free photoacoustic histopathology of clinical specimens. Laser Photonics Rev. 2021;2100124 [Google Scholar]

- 25.Chen J., Zhang Y., He L., Liang Y., Wang L. Wide-field polygon-scanning photoacoustic microscopy of oxygen saturation at 1-MHz A-line rate. Photoacoustics. 2020;20 doi: 10.1016/j.pacs.2020.100195. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Haven N.J.M., Bell K.L., Kedarisetti P., Lewis J.D., Zemp R.J. Ultraviolet photoacoustic remote sensing microscopy. Opt. Lett. 2019;44(14):3586–3589. doi: 10.1364/OL.44.003586. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Haven N.J.M., Kedarisetti P., Restall B.S., Zemp R.J. Reflective objective-based ultraviolet photoacoustic remote sensing virtual histopathology. Opt. Lett. 2020;45(2):535. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Cai D., Wong T.T.W., Zhu L., Shi J., Chen S.-L., Wang L.V. Dual-view photoacoustic microscopy for quantitative cell nuclear imaging. Opt. Lett. 2018;43(20):4875–4878. doi: 10.1364/OL.43.004875. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Wang L., Zhang C., Wang L.V. Grueneisen relaxation photoacoustic microscopy. Phys. Rev. Lett. 2014;113(17) doi: 10.1103/PhysRevLett.113.174301. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Liu X., Wong T.T.W., Shi J., Ma J., Yang Q., Wang L.V. Label-free cell nuclear imaging by Grüneisen relaxation photoacoustic microscopy. Opt. Lett. 2018;43(4):947–950. doi: 10.1364/OL.43.000947. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Abbasi S., Le M., Sonier B., Dinakaran D., Bigras G., Bell K., Mackey J.R., Haji Reza P. All-optical reflection-mode microscopic histology of unstained human tissues. Sci. Rep. 2019;9(1):13392. doi: 10.1038/s41598-019-49849-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplementary material