Abstract

Background

As a core component of harm-reduction strategies to address the opioid crisis, several countries have instituted publicly funded programs to distribute naloxone for lay administration in the community. The effectiveness in reducing mortality from opioid overdose has been demonstrated in multiple systematic reviews. However, the economic impact of community naloxone distribution programs is not fully understood.

Objectives

Our objective was to conduct a review of economic evaluations of community distribution of naloxone, assessing for quality and applicability to diverse contexts and settings.

Data Sources

The search strategy was performed on MEDLINE, Embase, and EconLit databases.

Study Eligibility Criteria and Interventions

Search criteria were developed based on two themes: (1) papers involving naloxone or narcan and (2) any form of economic evaluation. A focused search of the grey literature was also conducted. Studies exploring the intervention of community distribution of naloxone were selected.

Study Appraisal and Synthesis Methods

Data extraction was done using the British Medical Journal guidelines for economic submissions, assigning quality levels based on the impact of the missing or unclear components on the strength of the conclusions.

Results

A total of nine articles matched our inclusion criteria: one cost-effectiveness analysis, eight cost-utility analyses, and one cost-benefit analysis. Overall, the quality of the studies was good (six of high quality, two of moderate quality, and one of low quality). All studies concluded that community distribution of naloxone was cost effective, with an incremental cost-utility ratio range of $US111–58,738 (year 2020 values) per quality-adjusted life-year gained.

Limitations

Our search strategy was developed iteratively, rather than following an a priori design. Additionally, our search was limited to English terms.

Conclusions and Implications of Key Findings

Based on this review, community distribution of naloxone is a worthwhile investment and should be considered by other countries dealing with the opioid epidemic.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1007/s41669-021-00309-z.

Key Points for Decision Makers

| All studies reviewed concluded that community distribution of naloxone was cost effective, based on the willingness-to-pay threshold considered; all but one fell under the standard threshold of $US50,000 (year 2020 values). |

| The cost effectiveness of community distribution of naloxone increases with greater bystander willingness to intervene and/or higher rates of opioid overdose in the community. |

| The findings from this review demonstrate that, in many settings, most notably high-income countries, community distribution of naloxone for lay administration is a worthwhile investment that can and should be implemented. |

Introduction

The World Health Organization estimates that approximately 115,000 people died of opioid overdose globally in 2017 [1]. Common opioids include morphine, hydromorphone, oxycodone, heroin, and fentanyl [2]. Opioids are used medically for pain relief and anesthesia but can be highly addictive. Opioid overdose can lead to acute respiratory and nervous system depression, leading to death [3]. Several countries, particularly within Europe and North America, are facing an opioid crisis, experiencing steep increases in opioid-related deaths. In the USA, the number of deaths due to opioid overdose increased by 120% between 2010 and 2018 [1]. Moreover, the coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic has exacerbated the opioid crisis. In Canada, the number of opioid-related overdose deaths increased by over 50% from April to June 2020, in comparison with January to March 2020 or April to June 2019 [4]. In the USA, the highest number of overdose deaths ever recorded in a 12-month time frame occurred during the COVID-19 pandemic, with some jurisdictions seeing an increase of up to 98% [5].

In response to this crisis, many affected countries have recognized the importance of not only prevention and treatment but also harm reduction. As part of a harm-reduction strategy, several countries are now distributing naloxone kits to laypeople throughout the community via local pharmacies, community organizations, and public health organizations [6]. Naloxone is a drug used to temporarily reverse an overdose. It can be delivered intramuscularly, either via syringe or auto-injector, or intranasally [7]. Naloxone can often be found in emergency rooms and carried by emergency medical services (EMS). Yet, providing additional naloxone kits to the community enables people to intervene if they see someone experiencing an opioid overdose, allowing more time for the patient to receive definitive treatment at a hospital. Community distribution can take many forms, including free and easy access to naloxone kits via pharmacies or active distribution to high-risk populations through outreach programs [6]. The first take-home naloxone programs began in the 1990s in select communities, as part of grassroots initiatives, in the USA, Italy, Germany, and the UK [8]. Programs remained small and confined to specific localities until after 2010. Currently, publicly funded take-home naloxone programs and widespread distribution of naloxone kits exist in Canada, Australia, Italy, the UK, Ukraine, Estonia, Norway, Sweden, and Denmark as well as in some states in the USA [1, 8]. Some jurisdictions provide naloxone to anyone who requests a kit, and others provide free kits only to those at risk of experiencing or witnessing an overdose [1, 8].

Community distribution of naloxone has repeatedly been shown to be an effective tool in reducing opioid harms [9, 10]. A systematic review of cohort studies found that laypeople can be adequately trained to properly administer naloxone and that bystanders will intervene in suspected overdoses to provide naloxone and call EMS for transport to hospital for definitive medical treatment [9]. Also, a systematic review of observational studies found that community distribution of naloxone kits was consistently associated with decreased mortality from opioid overdose [10].

Nevertheless, effectiveness alone is often insufficient to justify publicly funding an intervention or drug in a public healthcare system. Governments want to know that an intervention is not only effective but also worthwhile in comparison with the costs of that intervention and often in comparison with other alternative interventions in which they could invest. It is crucial to explicitly consider the relative consequences of the alternatives to take-home naloxone and compare them with their relative costs. Although multiple systematic reviews, each including over a dozen studies, have established that naloxone is effective in reducing opioid-related mortality, the economic value of these programs is not as clearly established [11–13]. The Canadian Agency for Drugs and Technologies in Health (CADTH) performed a review and appraisal of community distribution of naloxone in 2014 but did not identify any economic evaluations at that time [11]. CADTH updated the review in 2019 but only included one cost-effectiveness study because of their specification that the comparator must be EMS or hospital administration of naloxone [12]. Mueller et al. [13] similarly conducted a review of community distribution of naloxone in 2015, including the cost effectiveness of such an initiative. This review had broader inclusion criteria than the CADTH review but still only identified two studies. Both Mueller et al. [13] and Chao and Loshak [12] focused mainly on effectiveness but concluded that community distribution of naloxone was cost effective based on the limited studies included in their reviews. Most recently, Beaulieu et al. [14] performed a systematic review of model-based cost-effectiveness studies for a variety of interventions to address opioid use disorder, one of which was distribution of naloxone to laypeople. They concluded that community distribution of naloxone was cost effective. However, as highlighted by the authors, the exclusion of trial-based studies leaves room for expansion. Trial-based cost-effectiveness studies are useful in verifying in real-world contexts the assumptions made in models. Additionally, our review updates the search of the literature by about a year and conducts a more thorough critical appraisal [14].

This paper synthesizes results from economic evaluations (cost-effectiveness analysis [CEA], cost-utility analysis [CUA], or cost-benefit analysis [CBA]) to determine whether community distribution of naloxone for lay administration is cost effective. The studies are summarized and critically appraised to assess quality. Given the broader range of types of economic evaluations, specifics of the intervention, and choice of comparators, the results of the studies are not aggregated. The applicability of findings to multiple settings and contexts is discussed. Particular attention is given to the factors that most impact on cost effectiveness.

Methods

Search Strategy

The search strategy was performed in the OVID MEDLINE, OVID Embase, and EconLit databases on 10 August 2020 using search criteria detailed in Appendix A in the electronic supplementary material (ESM). Search criteria were based on two themes: (1) papers involving naloxone or Narcan and (2) any form of economic evaluation. Search criteria were first developed for the MEDLINE search and then adapted for use in other databases. A targeted grey literature search was conducted by searching for the term “naloxone” on the websites of governmental agencies devoted to evaluations of drugs and prominent mental health organizations within the USA, as well as those of the USA’s Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development comparator countries. The search strategy was developed in collaboration with a McMaster University health sciences librarian.

Inclusion and Exclusion Criteria

Inclusion criteria required articles to contain an economic evaluation inclusive to CEA, CUA, or CBA and to include community distribution of naloxone as a component of assessment. These three types of analysis primarily differ in the way that the outcome is measured. CEAs are measured in health units such as life-years gained, CUAs are measured in health-related preferences such as quality-adjusted life-years (QALYs), and CBAs are measured in monetary units. We also included both targeted distribution to at-risk groups within the community and expanded distribution to all laypeople. Both trial- and model-based analyses were included. Conversely, articles were excluded if (1) economic evaluation was not performed (e.g., cost listings without economic evaluation), (2) the primary intervention being studied was in-hospital or EMS naloxone distribution, or (3) the primary intervention being studied was a non-naloxone drug for the treatment of opioid use disorder or alcohol use disorder (e.g., buprenorphine–naloxone, naltrexone, and nalmefene). Systematic reviews were excluded from data extraction but were used to identify any further articles that met inclusion criteria.

Review of Articles

Two investigators, N.C. and R.T., independently appraised titles and abstracts for relevance and inclusion and exclusion criteria satisfaction. Disagreements were discussed and resolved by consensus of three investigators. Identified systematic reviews were assessed by one reviewer, J.K., to further identify relevant articles, but none were found.

Data Extraction and Critical Appraisal

Data extraction and quality assessment were conducted by two investigators. Data extraction sheets, included in Appendix B in the ESM, were developed following the British Medical Journal (BMJ) guidelines for submissions of economic evaluations to ensure study quality and to assess the risk of bias [15]. This tool was chosen for its ability to assess both trial- and model-based economic evaluations and its comprehensive list of assessment items [16]. Drummond et al. [17] created an updated tool in 2015; however as it was deemed to be comparable, we used the previous version. Extraction focused on identifying the research question, economic importance, intervention, comparator, primary outcome, form of economic evaluation, model details (currency, inflation, and discounting), sensitivity analysis, outcome of economic evaluation, and results (incremental cost-effectiveness ratio [ICER], incremental cost-utility ratio [ICUR], and/or incremental cost-benefit ratio [ICBR]). For comparability purposes, all costs were converted to $US, year 2020 values, using annual average inflation and conversion rates, rounded to the nearest dollar, using exchange and inflation rates from the International Monetary Fund [18, 19]. Adjustments were not made for purchasing power parity (PPP) because all but one study were conducted in high-income countries with fairly similar PPP. The level of quality was subjectively assigned, based both on the number of missing or unclear elements as identified by the BMJ guidelines and the impact of those missing elements on the strength of the conclusions. Generally, studies missing four or fewer elements were considered high quality, studies missing five to seven elements were considered moderate quality, and those missing eight or more elements were considered low quality. However, studies were also moved up or down categories according to the importance of the missing elements.

Results

Summary of Identified Studies

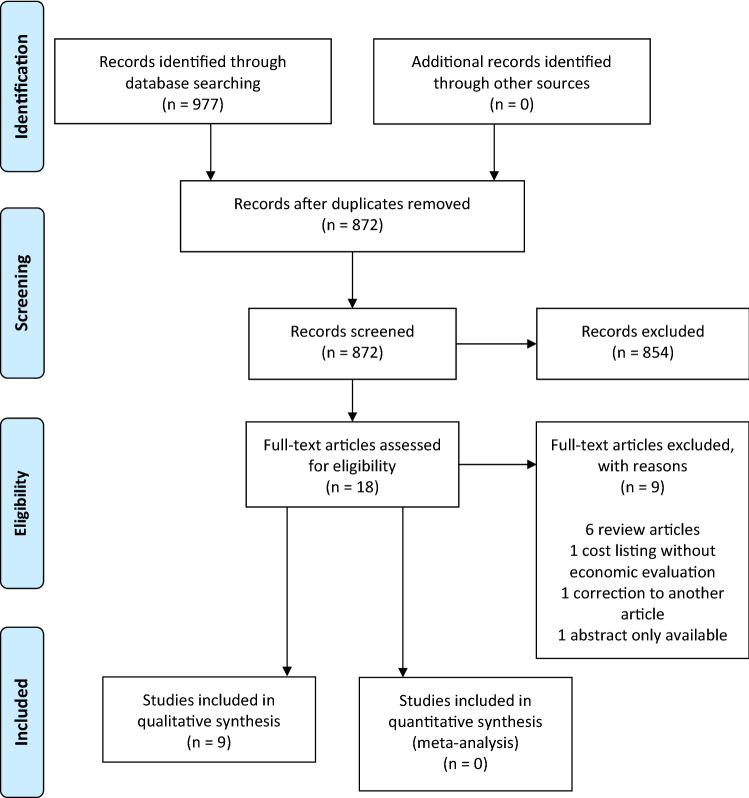

The search strategy identified a total of 977 articles to review across the three databases (see the PRISMA [Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses] diagram in Fig. 1). No additional studies were found through the grey literature search. Of the 977 articles, 959 were excluded because they failed to meet the inclusion criteria or met the exclusion criteria, leaving 18 studies for full-text review. Six narrative reviews were identified and excluded because they did not present or assess economic evaluations or considerations. One article was excluded because it provided a cost listing for a take-home naloxone program without an economic evaluation. One article was excluded because it was a minor correction to another article already included and the correction did not change the findings of the original article. One article was excluded because it was an abstract from a conference presentation of a separate study for which no further information could be found, even after contacting the corresponding author. A total of nine studies were included in the review. Appendix C in the ESM provides a list of all articles that were assessed in the full-text review, with an explanation for their exclusion.

Fig. 1.

PRISMA (Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses) diagram [31] outlining the review of articles from the database search. In total, 197 articles were returned from MEDLINE, 780 from Embase, and none from EconLit

The included studies consisted of one CEA, eight CUAs, and one CBA (ten analyses from nine studies—one study conducted both a CBA and a CEA). Studies covered a variety of settings, including the USA (n = 5), Canada (n = 1), Russia (n = 1), Scotland (n = 1), and the UK (n = 1), where five were focused at the national level and four on specific cities. Articles were published from 2013 to 2020, and all declared funding except for two, which had no conflicts of interest to disclose. All studies included community distribution of naloxone for lay administration as a component of their intervention, though some articles differed on specific populations targeted. Seven studies looked at users or hypothetical users, one study looked at non-users, and one study looked at counties with at least five opioid overdose deaths each year. Eight studies used the comparator of no distribution, with one using an additional comparator of pre-exposure prophylaxis, and one study comparing a combination of distribution to laypeople, police and fire, and EMS. All studies used a Markov and/or decision-analytic model, apart from one study that was trial based. Five studies used a societal perspective, three studies used a healthcare perspective, and one study used both a societal and a healthcare perspective. Six studies used a lifetime time horizon, one study used a 20-year time horizon, and two studies did not specify a time horizon. After analysis, all studies found positive benefits related to health, where community distribution of naloxone either prevented or reduced the number of overdose-related deaths. Results were rated as worthwhile on the basis of each article’s willingness-to-pay (WTP) threshold. If no WTP threshold was stated, we used a conservative WTP threshold of $US50,000.

Table 1 provides a summary of the results from the data extraction.

Table 1.

| Study | Study details | Effects | ICBR/ICUR/ICER | Cost conversion and inflation ($US, years 2020 values) | Sensitivity analysis | Conclusion | Quality | Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Townsend et al. [20] |

Setting: USA Population: Hypothetical individuals with OUD who entered the model at 35 years Intervention: Community distribution of naloxone to community, fire/policy, and EMS Comparator: Eight strategies that encompass all combinations of low and high distribution to laypeople, police and fire, and EMS Model: decision-analytic Time horizon of cost: Lifetime |

Intervention reduced overdose deaths | ICUR: $US12,880–15,950/QALY | ICUR: 13,568–16,907/QALY |

Considered: - Price of naloxone - Rates of distribution - Percentage of people who intervene in overdose - Hypothetical moral hazard Rate of distribution made the largest impact; did not change conclusion |

Naloxone distribution is a good investment and worthwhile, assuming < $US2200 per kit | High |

Did not report: - Justification for form of economic evaluation - Quantities of resources |

| Langham et al. [21] |

Setting: UK Population: Adults (≥ 22 years) at risk of heroin overdose Intervention: Community distribution of naloxone for lay administration Comparator: No distribution Model: Markov model with an integrated decision tree Time horizon of cost: Lifetime (default value set to 64 years) |

Intervention increased overdoses by 2.7%, reduced overdose deaths by 6.6%, and increased lifetime QALYs by 0.164 |

ICUR: £899.00/QALY | ICUR: 1312/QALY |

Considered: - Price of naloxone - Additional societal costs - Rates of distribution - Witness to overdose No substantive impact; did not change conclusion |

Naloxone distribution is worthwhile, assuming a $US20,000 WTP threshold | High |

Did not report: - Rationale for comparison intervention - Justification for form of economic evaluation - Quantities of resources - Justification for variables chosen for sensitivity analysis |

| Cipriano and Zaric [22] |

Setting: Toronto, Canada Population: high-school students Intervention: community distribution of naloxone in Toronto District School Board high schools Comparator: other treatment and harm-reduction plans in Toronto (status quo) Model: decision-analytic model Time horizon of cost: Lifetime |

Intervention reduced overdose deaths by 40% | ICUR: < CAN$50,000/QALY if 2.7 overdoses/year | ICUR: < 36,525/QALY if 2.7 overdoses/year |

Considered: - No. of overdoses per year - Intensity of substance use disorder - Mortality rate Number of overdoses per year had the largest impact |

Naloxone distribution is worthwhile, assuming the frequency of overdose is more than 2.7 overdoses per year | High |

Did not report: - Details of statistical test - Justification for form of economic evaluation - Rationale for comparison intervention |

| Uyei et al. [23] |

Setting: Connecticut, USA Population: HIV-negative people who inject drugs and were not on PrEP Intervention: Community distribution of naloxone for lay administration Comparator: No additional intervention, naloxone distribution plus linkage to addiction treatment, naloxone distribution plus PrEP, naloxone distribution plus linkage to addiction treatment and PrEP Model: Decision-analytic Markov Time horizon of cost: 20 years |

Intervention reduced overdose deaths by 6% but increased HIV deaths | ICUR: $US323/QALY | ICUR: 352/QALY |

Considered: - Price of naloxone - Survival rates - Percentage of people who intervene in overdose No substantial impact; did not change conclusion |

Naloxone distribution is worthwhile, recommend funding | High |

Did not report: - Justification for form of economic evaluation - Quantities of resources |

| Coffin and Sullivan [24] |

Setting: USA Population: Hypothetical 21-year-old novice US heroin users and more experienced users Intervention: Community distribution of naloxone for lay administration to those at high risk of opioid overdose Comparator: No distribution Model: Integrated Markov and decision analytic Time horizon of cost: Lifetime |

Intervention prevented 6.5% of overdose deaths | ICUR: $US14,000/QALY | ICUR: 15,784/QALY |

Considered: - Price of naloxone - Rate of bystander response - Justice system rates Bystander response rate made largest impact on ICER; did not change conclusion |

Naloxone distribution is worthwhile; recommend funding | High |

Did not report: - Study viewpoints - Rationale for comparison intervention - Justification for form of economic evaluation - Quantities of resources - Justification of discount rate |

| Coffin and Sullivan [25] |

Setting: Russia Population: Heroin users, starting at the age of 18 years Intervention: Community distribution of naloxone for lay administration to those at high risk of opioid overdose Comparator: No distribution Model: Integrated Markov and decision analytic Time horizon of cost: Lifetime |

Intervention reduced overdose deaths by 13.4% in the first 5 years and 7.6% over a lifetime | ICUR: $US94/QALY | ICUR: 112/QALY |

Considered: - Price of naloxone - Rate of bystander response - Justice system rates Bystander response rate made largest impact on ICER; did not change conclusion |

Naloxone distribution is worthwhile; recommend funding | High |

Did not report: - Study viewpoints - Rationale for comparison intervention - Justification for form of economic evaluation - Quantities of resources |

| Acharya et al. [26] |

Setting: USA Population: high-risk prescription opioid users Intervention: naloxone distribution to all high-risk prescription opioid users either one time or biannually Comparator: baseline naloxone distribution strategy based on existing naloxone dispensing rates Model: Markov model with monthly cycle length and attached decision tree Time horizon of cost: Lifetime |

Intervention modestly reduced overdose deaths | ICUR: $US56,699–76,929/QALY |

ICUR: 58,400–79,237/ QALY |

Considered: - Price of naloxone - Naloxone effectiveness - Proportion of overdoses witnessed - Probability of EMS intervention - Overdose survival rates Naloxone effectiveness and proportion of overdoses witnessed had the largest impact on biannual distribution; did not change conclusion |

Naloxone distribution is worthwhile, assuming a $US100,000 WTP threshold | Moderate |

Did not report: - Study viewpoints - Rationale for comparison intervention - Justification for form of economic evaluation, - Quantities of resources |

| Bird et al. [27] |

Setting: Scotland Population: Those at highest risk of opioid-related death, who might be expected to benefit the most from the national naloxone program Intervention: Community distribution of naloxone to individuals at risk of opioid overdose, following prison release Comparator: Same group, prior to intervention Model: NA Time horizon of cost: NA |

Intervention prevented 42 overdose deaths (3.5% decrease) | ICUR: £560–16,900/QALY |

ICUR: 769–23,209/ QALY |

Considered: - Averted overdose numbers No substantive impact; did not change conclusion |

Naloxone distribution is worthwhile; recommend continued funding | Moderate |

Did not report: - Economic importance of the research question - Justification for form of economic evaluation - Price adjustment for inflation or currency conversion - Time horizon of costs and benefits - Justification of the discount rate - Incremental analysis - Approach to sensitivity analysis - Justification for variables chosen for sensitivity analysis |

| Naumann et al. [28] |

Setting: North Carolina, USA Population: Counties with at least five opioid overdose deaths each year in the period immediately preceding implementation Intervention: Community distribution of naloxone for lay administration Comparator: No distribution Model: Trial based Time horizon of cost: NA |

Intervention prevented 352 overdoses over 3 years |

ICBR: $US2742 benefit/ dollar spent ICER: $US1605/death avoided |

ICBR: 2769 benefit/ dollar spent ICER: 1621/death avoided |

Considered: - Price of naloxone No substantive impact; did not change conclusion |

Naloxone is cost effective; recommend funding | Low |

Did not report: - Justification of comparison intervention - Justification for form of economic evaluation - Details of synthesis of estimates - Price adjustment for inflation or currency conversion - Model details - Time horizon of costs and benefits - Discount rate - Approach to sensitivity analysis |

EMS emergency medical services, ICBR incremental cost-benefit ratio , ICER incremental cost-effectiveness ratio , ICUR incremental cost-utility ratio , NA not available, OUD opioid use disorder, PrEP pre-exposure prophylaxis, QALY quality-adjusted life-year, WTP willingness to pay

Cost-Utility Analyses

The study conducted in the USA by Townsend et al. [20] observed that community distribution of naloxone was only worthwhile at a WTP threshold of $US50,000 (year 2017 values; $US53,000 in 2020) and if the kits cost less than $US2200 (year 2017 values; $US2332 in 2020) and was the most worthwhile when community distribution was combined with high EMS distribution and low police officer and firefighter distribution; returning an ICUR of $US12,880–15,950 (year 2017 values; $US13,568–16,907 in 2020) per QALY gained. Further, 5% more overdose deaths were prevented with high EMS distribution and low police officer and firefighter distribution compared with overdose death rates with low distribution in all three groups [20]. Both deterministic and probabilistic sensitivity analyses were performed, which considered ranges for the price of naloxone, the percentage of people who intervened in overdose, a hypothetical moral hazard, and the rates of distribution [20]. Although the rate of distribution had the largest impact, community distribution still proved worthwhile throughout the range considered [20]. Therefore, none of the evaluated variables changed the conclusion [20]. This study did not report justification for the form of economic evaluation or the quantities of resources separately reported from their unit cost. This study was classified as high quality.

The study by Langham et al. [21] was set in the UK and found that, although the intervention increased overdoses by 2.7%, it reduced overdose death by 6.6% and increased lifetime QALYs by 0.164, with an ICUR of £899 (year 2016 values; $US1312 in 2020) per QALY gained. They determined naloxone distribution to be worthwhile, assuming a WTP threshold of £20,000 (year 2016 values; $US29,189 in 2020) [21]. In their probabilistic sensitivity analysis, they considered ranges for the price of naloxone, additional societal costs, rates of distribution, and witness to overdose [21]. However, none of the variables had a substantive impact so did not change the conclusion [21]. This study clearly reported all elements, with the exception of the rationale for the comparison intervention, justification for the form of economic evaluation, the quantities of resources or unit cost, or justification for the variables in the sensitivity analysis. Overall, this study was classified as high quality.

In the Canadian study by Cipriano and Zaric [22], community distribution of naloxone was considered worthwhile at a WTP threshold of CAN$50,000 (year 2018 values; $US36,525 in 2020) per QALY gained. This school-based naloxone distribution program was found to be worthwhile in the probabilistic sensitivity analysis, which considered the number of overdoses per year and the effectiveness of the program at reducing mortality [22]. The scenarios considered ranged from 15 to 97% program effectiveness. In the worst-case scenario of 15% effectiveness, the program would be worthwhile with an ICUR >CAN$50,000 (year 2018 values; $US36,525 in 2020) per QALY gained at a minimum overdose rate of 2.7 per year; in the best-case scenario of 97% effectiveness, the program would be worthwhile with an ICUR of > CAN$50,000 (year 2018 values; $US36,525 in 2020) per QALY gained at a minimum overdose rate of 0.4 per year [22]. This study was classified as high quality, with only the details of statistical test and confidence intervals for scholastic data, justification for the form of economic evaluation, and the rationale for the comparator not reported.

Uyei et al. [23] based their study in the USA and ran their model for 20 years, concluding that the intervention reduced overdose deaths by 6% but increased HIV deaths. Considering a WTP threshold of $US100,000 (year 2015 values; $US109,216 in 2020), they concluded that naloxone distribution was worthwhile with an ICUR of $US323 (year 2015 values; $US352 in 2020) per QALY gained and recommended that the program be funded [23]. Their one-way sensitivity analysis considered ranges for the price of naloxone, survival rates, and the percentage of people who intervene in overdose [23]. No variables had a substantial impact or changed the conclusion [23]. This study was determined to be high quality, missing a justification for the form of economic evaluation and quantities of resources reported separately from their unit costs.

In the USA, Coffin and Sullivan [24] found that the intervention prevented 6.5% of overdose deaths, with an ICUR of $US14,000 (year 2012 values; $US15,784 in 2020) per QALY gained. All in all, naloxone distribution was worthwhile at a WTP threshold of $US50,000 (year 2012 values; $US56,500 in 2020), with funding being recommended [24]. Both deterministic and probabilistic sensitivity analyses were performed, which considered ranges for the price of naloxone, rates of bystander response, and justice system rates [24]. In the deterministic sensitivity analysis, bystander response rate made the largest impact on the ICUR but was not important enough to alter the conclusion [24]. This study was found to be of high quality, with elements of study viewpoints and justification, rationale for comparator, justification of form of economic evaluation, quantities of resources reported separately from unit costs, and justification of discount rate not included.

The Russian study by Coffin and Sullivan [25] built off their previous research by using the same model and variables in the sensitivity analysis. They found that the intervention reduced overdose deaths by 13.4% in the first 5 years and by 7.6% over a lifetime, with an ICUR of $US94 (year 2010 values; $US112 in 2020) per QALY gained. Again, they found that naloxone distribution was worthwhile at a WTP threshold of $US1500 (year 2010 values; $US1785 in 2020) and recommended funding the program [25]. In the deterministic sensitivity analysis, bystander response rate again made the largest impact on the ICUR, but the impact was not substantial enough to change the conclusion [25]. This study was found to be of high quality, only missing elements of study viewpoints and justification, rationale for choosing comparator, justification of form of economic evaluation, and quantities of resources reported separately from unit costs.

Results of the study by Acharya et al. [26], set in the USA, showed that intervention modestly reduced overdose deaths, with an ICUR of $US56,699–76,929 (year 2018 values; $US58,400–79,237 in 2020) per QALY gained. Thus, naloxone distribution was worthwhile, assuming a WTP threshold of $US100,000 (year 2018 values; $US103,083 in 2020) [26]. Both deterministic and probabilistic sensitivity analyses were performed, which considered the price of naloxone, naloxone effectiveness, the proportion of overdoses witnessed, the probability of EMS intervention, overdose risk based on the specific opioid, and overdose survival rates [26]. In the deterministic sensitivity analysis, naloxone effectiveness and the proportion of overdoses witnessed had the largest impact on biannual distribution but did not have a large enough impact to change the conclusion [26]. This study quality was assessed as moderate because of the lack of clear reporting of the viewpoints of the analysis, the rationale for choosing the alternative program or intervention, the justification of the form of economic evaluation, the quantities of resources, and price data.

The Scottish study by Bird et al. [27] resulted in a 3.5% decrease in overdose deaths and had an ICUR of £560–16,900 (year 2015 values; $US769–23,209 in 2020) per QALY gained. No WTP threshold was specified, but naloxone distribution was deemed worthwhile upon conclusion, with continued funding recommended [27]. This study performed a one-way sensitivity analysis on averted overdose numbers [27]. This study did not report the economic importance of the research question, justification for the form of economic evaluation, details of currency price adjustment for inflation or currency conversion, time horizon of costs and benefits, justification of the discount rate, incremental analysis, the approach to sensitivity analysis, or justification of variables chosen for sensitivity analysis. These missing elements resulted in a quality rating of moderate.

Cost-Benefit and Cost-Effectiveness Study

In their study set in the USA, Naumann et al. [28] deemed community distribution of naloxone to be a good investment. They found that, over the course of 3 years, 352 overdose deaths were prevented, leading to an ICBR of $US1:$US2742 (year 2019 values; $US1:$US2769 in 2020). This study based the one-way sensitivity analysis solely on the price of naloxone [28]. They also performed a CEA and deemed community distribution of naloxone to be cost effective [28]. The ICER was $US1605 (year 2019 values; $US1621 in 2020) per death avoided from opioid overdose [28]. No WTP threshold was specified; however, the conclusion of cost effectiveness was stated. This study was found to be of low quality as the rationale for choosing the comparison intervention, justification for the form of economic evaluation, details of currency price adjustments for inflation or currency conversion, the choice of model used and its key parameters, the time horizon of costs and benefits, a discount rate, an explanation for not discounting costs, or the approach to sensitivity analysis were not clearly reported.

Discussion

We conducted a systematic review of economic analyses of community distribution of naloxone to better understand the economic impact of these programs. In total, nine articles met the inclusion criteria, including one CEA, eight CUAs, and one CBA. All economic evaluations identified by this review concluded that community distribution of naloxone was a worthwhile investment across all settings and populations considering the set WTP threshold within each study and taking into account sensitivity analyses. CUAs, in particular, found that ICUR estimates all fell below a $US50,000 WTP threshold, with one exception being Acharya et al. [26], with an ICUR of $US58,400–79,237 (year 2020 values).

Application of Findings

Quality ranged widely across the studies, as assessed by the BMJ guidelines for submission of economic evaluations: six were deemed to be of high quality, two of moderate quality, and one of low quality. Many articles were missing key information necessary to understand the assumptions behind their models or analysis of trials. ICURs also ranged widely across all analyses. This may have been because of the differing parameter estimates considered in each study. In addition, one major outlier did not satisfy the standard $US50,000 WTP threshold. Acharya et al. [26] was the only study to take a solely healthcare perspective in their analysis, as well as a particular focus on naloxone distribution to high-risk prescription opioid users as opposed to the general public, which may explain their higher ICUR compared with the other studies. Nevertheless, all studies did conclude that community distribution of naloxone was cost effective according to their specified WTP threshold. This consistency in results across studies with varying contexts and methodologies presents strong evidence towards concluding that community naloxone distribution is a cost-effective approach to overdose prevention and the opioid crisis. Importantly, the most recent study [26] and the study that was based on a trial [27] re-affirmed previous findings that community distribution of naloxone for lay administration was cost effective in reducing deaths due to opioid overdose.

The majority of studies were from the USA, with single studies from Canada, Russia, Scotland, and the UK also included. Populations across and within these settings differed greatly in many factors: demographics, healthcare accessibility, drug use behavior, and cultural contexts. Although all studies indicated that community naloxone distribution was cost effective, a more representative sample of global programs or a more comprehensive localized set of data can increase external validity. In particular, the applicability of these findings to low-income settings is less certain given their different contexts and cost-effectiveness thresholds [29]. However, the conclusion that naloxone distribution is a worthwhile investment is consistent across all studies, considering different settings, countries, and variables in sensitivity analyses. This speaks to the likelihood that these results are robust and will hold up across contexts not yet explored.

Several studies utilized modelling to run economic evaluations. Although reliable region-specific sources of data contributed to building the models of the need for, use of, and impact of naloxone distribution, such models do not always catch the contextual and environmental nuances of a given environment. A greater proportion of primary data collection and evaluation of implemented programs will strengthen the quality of data used and potential conclusions. Nevertheless, results of this review are strengthened by the inclusion of a trial-based study, showcasing the applicability and success of the community naloxone programs in the real-world setting.

One of the most important limitations was the differences in variables considered for sensitivity analysis between each study. This affected the comparability of the studies that considered more specific variables. For this reason, we focused on a subset of the most important variables when considering sensitivity analysis conclusions. For example, Naumann et al. [28] considered only the price of naloxone within the sensitivity analysis. Yet, in the studies that considered a greater number of variables, the factors that made the largest impact on the ICUR were the rates of opioid overdose, the willingness of bystanders to intervene in witnessed overdoses, and the percentage of the target population that could be reached with the intervention. Thus, in considering whether or not to implement a program for community distribution of naloxone, these factors should be assessed. If the rate of opioid overdose is low and/or bystanders are not willing to intervene, the program will likely become less cost effective.

Another area of recurrent concern for many of the included studies was the choice of comparator. All but two studies used no intervention as the comparator. Further, half of the studies did not explicitly justify the choice of comparator. Many settings that may be considering implementing or funding community distribution of naloxone may already have some harm-reduction programs in place. In this case, the funding body may wish to know specifically whether adding naloxone distribution to their current program would be cost effective. Only Uyei et al. [23] evaluated community naloxone distribution compared with syringe-exchange programs. This study also incorporated addiction treatment and the availability of pre-exposure prophylaxis for HIV into their analysis [23]. Thus, this study represents a significant contribution to our understanding of how varying components of a harm-reduction strategy may work together and which are most cost effective.

Strengths and Limitations

In comparison with previous reviews, this review includes the latest findings and has the broadest inclusion criteria. In fact, a review by CADTH in 2014 did not identify any studies on this topic, which demonstrated the need for further research [11]. Further, the most recent systematic review of the topic excluded trial-based studies and did not include the most recent economic analysis. In contrast, we were able to include nine studies, as more research on this area has been done in recent years, to provide a greater understanding of the economic impact of community distribution of naloxone in a variety of contexts. The broad inclusion criteria has meant that direct comparison of studies was more difficult and a meta-analysis was not possible. Nevertheless, the fact that all studies concluded that community distribution of naloxone was economically worthwhile is notable. This allows readers to consider which of these studies would be most applicable and adaptable to their contexts.

In assessing our review using the AMSTAR 2 tool [30], which is included in Appendix D in the ESM, one noticeable difference is that we did not use an a priori design. Instead, our review protocol, including our search strategy, was developed iteratively. However, our final search strategy was reviewed with a health sciences librarian. Additionally, the search was limited to English terms, which may have missed other studies, particularly within the grey literature.

Future Directions

This review demonstrates that a need remains for further economic evaluations of community distribution of naloxone programs across broader populations and contexts. Future evaluations can be improved by choosing a more context-relevant comparator and by expanding the variables considered in the sensitivity analyses. In particular, both programs that targeted groups at risk of experiencing or witnessing an overdose and programs that distributed naloxone to any interested layperson were included in this review, where one of the studies compared those two distribution strategies. Thus, this review demonstrates the importance of incremental analysis of varying strategies in future evaluations to best inform policy and program decisions.

Additionally, several studies discussed briefly the costs and outcomes that may be relevant from a societal perspective, but none included those relevant costs and outcomes within their analysis in a fulsome way. For example, Townsend et al. [20] intended to take a societal perspective but did not include justice-related costs and outcomes. The analysis of each study followed a similar pattern, with the exception of Coffin and Sullivan [25], who included all relevant costs and outcomes. The inclusion of more productivity and justice system considerations would be informative. Further, the low availability of economic evaluations of community naloxone distribution programs indicates the importance of including an economic evaluation and an overall evaluation process as a component of all naloxone distribution programs from the planning and implementation stages. To have high-quality measures to serve as control and comparators from pre- and post-implementation stages, an economic evaluation could be incorporated in the implementation of naloxone programs. An increased sample size of evaluations of community naloxone distribution programs would aid in gathering a robust base of data across contexts and inform future implementation of programs. Lastly, all studies were from high- or middle-income countries, so results are not generalizable to low-income countries, where healthcare systems are not financially stable. Further research into naloxone availability and distribution across assorted settings is recommended.

Conclusion

In sum, all studies found community distribution of naloxone to be cost effective. Findings from this review can help inform and advocate for further implementation of naloxone distribution programs in areas where opioid overdose is a prominent concern. Though safe injection sites and EMS are often equipped with naloxone, people who use opioids may prefer to use drugs in isolation or among other users. The findings of this review are relevant to policy makers who implement guidelines and programs for overdose response. The findings from this review demonstrate that, in many settings, most notably high-income areas, community distribution of naloxone for lay administration is likely a worthwhile investment that can and should be implemented by communities across the globe. Based on these findings, countries that are currently providing publicly funded take-home naloxone programs should continue to do so and perhaps explore how those programs may be expanded. Countries and jurisdictions that are not yet funding community distribution of naloxone should consider similar programs based on an assessment of their rate of opioid overdose, willingness of bystanders to intervene in an overdose, and ability to reach the target population. However, implementation in high-income countries, regardless of these variables, is heavily supported through these results. The consistency of economically efficient conclusions across all studies should motivate the implementation of community naloxone programs.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Declarations

Funding

No sources of funding were used to conduct this study or prepare this manuscript.

Conflict of Interest

Nelda Cherrier, Joanne Kearon, Robin Tetreault, Sophiya Garasia, and G. Emmanuel Guindon have no conflicts of interest that are directly relevant to the content of this article.

Ethics approval

Not applicable.

Consent to participate

Not applicable.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Availability of data and material

The data supporting the findings of this study are available within the article or its supplementary materials.

Code availability

Not applicable.

Author contributions

N.C., J.K., and R.T. equally participated in the conceptualization of this project, the literature search and data extraction, and the writing and editing of the manuscript. S.G. and G.E.G. guided the process and contributed to the editing of the manuscript.

References

- 1.World Health Organization. Opioid Overdose. 2020. https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/opioid-overdose. Accessed 9 Mar 2021.

- 2.Belzak L, Halverson J. The opioid crisis in Canada: a national perspective. Health Promot Chronic Dis Prev Can. 2018;38:224–233. doi: 10.24095/hpcdp.38.6.02. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.White JM, Irvine RJ. Mechanisms of fatal opioid overdose. Addiction (Abingdon, England). 1999;94(7):961–972. doi: 10.1046/j.1360-0443.1999.9479612.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Government of Canada. Opioid- and stimulant-related harms in Canada. 2020. https://health-infobase.canada.ca/substance-related-harms/opioids-stimulants/. Accessed 9 Mar 2021.

- 5.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Overdose deaths accelerating during COVID-19. 2020. https://www.cdc.gov/media/releases/2020/p1218-overdose-deaths-covid-19.html. Accessed 9 Mar 2021.

- 6.Pant S, Severn M. Funding and management of naloxone programs in Canada. Canadian Agency for Drugs and Technologies in Health. 2018. https://www.cadth.ca/funding-and-management-naloxone-programs-canada-0. Accessed 8 Sept 2020.

- 7.Kaserer T, Lantero A, Schmidhammer H, Spetea M, Schuster D. μ Opioid receptor: novel antagonists and structural modeling. Sci Rep. 2016 doi: 10.1038/srep21548. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.European Monitoring Centre for Drugs and Drug Addiction. Take-home naloxone. 2020. https://www.emcdda.europa.eu/publications/topic-overviews/take-home-naloxone_en. Accessed 9 Mar 2021.

- 9.Clark AK, Wilder CM, Winstanley EL. A systematic review of community opioid overdose prevention and naloxone distribution programs. J Addict Med. 2014;8(3):153–163. doi: 10.1097/adm.0000000000000034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.McDonald R, Strang J. Are take-home naloxone programmes effective? Systematic review utilizing application of the Bradford Hill criteria. Addiction (Abingdon, England). 2016;111(7):1177–1187. doi: 10.1111/add.13326. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Canadian Agency for Drugs and Technologies in Health. Administration of naloxone in a home or community setting: a review of the clinical effectiveness, cost-effectiveness, and guidelines. 2014. https://www.cadth.ca/administration-naloxone-home-or-community-setting-review-clinical-effectiveness-cost-effectiveness. Accessed 8 Sept 2020. [PubMed]

- 12.Chao Y, Loshak H. Administration of naloxone in a home or community setting: a review of the clinical effectiveness, cost-effectiveness, and guidelines. Canadian Agency for Drugs and Technologies in Health. 2019. https://www.cadth.ca/administration-naloxone-home-or-community-setting-review-clinical-effectiveness-cost-effectiveness-1. Accessed 8 Sept 2020. [PubMed]

- 13.Mueller SR, Walley AY, Calcaterra SL, Glanz JM, Binswanger IA. A review of opioid overdose prevention and naloxone prescribing: implications for translating community programming into clinical practice. Subst Abuse . 2015 doi: 10.1080/08897077.2015.1010032. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Beaulieu E, DiGennaro C, Stringfellow E, Connolly A, Hamilton A, Hyder A, Cerdá M, Keyes KM, Jalali MS. Economic evaluation in opioid modeling: systematic review. Value Health. 2020 doi: 10.1016/j.jval.2020.07.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Drummond MF, Jefferson TO. Guidelines for authors and peer reviewers of economic submissions to the BMJ. The BMJ Economic Evaluation Working Party. BMJ (Clin Res Ed). 1996;313(7052):275–283. doi: 10.1136/bmj.313.7052.275. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Walker DG, Wilson RF, Sharma R, Bridges J, Niessen L, Bass EB, Frick K. Best practices for conducting economic evaluations in health care: a systematic review of quality assessment tools. Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality; 2012. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Drummond MF, Sculpher MJ, Claxton K, Stoddart GL, Torrance GW. Methods for the economic evaluation of healthcare programmes. 4. Oxford: Oxford University Press; 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 18.International Monetary Fund. Exchange rates incl. Effective Ex. Rates—IMF Data. 2021. https://data.imf.org/regular.aspx?key=61545850. Accessed 16 July 2021.

- 19.International Monetary Fund. World Economic Outlook Database. 2021 https://www.imf.org/en/Publications/WEO/weo-database/2021/April/weo-report?c=111,&s=PCPI,PCPIPCH,PCPIE,PCPIEPCH,&sy=2010&ey=2021&ssm=0&scsm=1&scc=0&ssd=1&ssc=0&sic=0&sort=country&ds=.&br=1. Accessed 16 July 2021.

- 20.Townsend T, Blostein F, Doan T, Madson-Olson S, Galecki P, Hutton DW. Cost-effectiveness analysis of alternative naloxone distribution strategies: first responder and lay distribution in the United States. Int J Drug Policy. 2020;75:102536. doi: 10.1016/j.drugpo.2019.07.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Langham S, Wright A, Kenworthy J, Grieve R, Dunlop WCN. Cost-effectiveness of take-home naloxone for the prevention of overdose fatalities among heroin users in the United Kingdom. Value Health. 2018;21(4):407–415. doi: 10.1016/j.jval.2017.07.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Cipriano LE, Zaric GS. Cost-effectiveness of naloxone kits in secondary schools. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2018;192:352–361. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2018.08.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Uyei J, Fiellin DA, Buchelli M, Rodriguez-Santana R, Braithwaite RS. Effects of naloxone distribution alone or in combination with addiction treatment with or without pre-exposure prophylaxis for HIV prevention in people who inject drugs: a cost-effectiveness modelling study. Lancet Public Health. 2017;2(3):e133–e140. doi: 10.1016/S2468-2667(17)30006-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Coffin PO, Sullivan SD. Cost-effectiveness of distributing naloxone to heroin users for lay overdose reversal. Ann Intern Med. 2013;158(1):1–9. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-158-1-201301010-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Coffin PO, Sullivan SD. Cost-effectiveness of distributing naloxone to heroin users for lay overdose reversal in Russian cities. J Med Econ. 2013;16(8):1051–1063. doi: 10.3111/13696998.2013.811080. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Acharya M, Chopra D, Hayes CJ, Teeter B, Martin BC. Cost-effectiveness of intranasal naloxone distribution to high-risk prescription opioid users. Value Health. 2020 doi: 10.1016/j.jval.2019.12.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Bird SM, McAuley A, Perry S, Hunter C. Effectiveness of Scotland’s national naloxone programme for reducing opioid-related deaths: a before (2006–10) versus after (2011–13) comparison. Addiction. 2016;111(5):883–891. doi: 10.1111/add.13265. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Naumann RB, Durrance CP, Ranapurwala SI, Austin AE, Proescholdbell S, Childs R, Marshall SW, Kansagra S, Shanahan ME. Impact of a community-based naloxone distribution program on opioid overdose death rates. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2019;204:107536. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2019.06.038. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Woods B, Revill P, Sculpher M, Claxton K. Country-level cost-effectiveness thresholds: initial estimates and the need for further research. Value Health. 2016 doi: 10.1016/j.jval.2016.02.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Shea BJ, Reeves BC, Wells G, Thuku M, Hamel C, Moran J, Moher D, Tugwell P, Welch V, Kristjansson E, Henry DA. AMSTAR 2: a critical appraisal tool for systematic reviews that include randomised or non-randomised studies of healthcare interventions, or both. BMJ (Clin Res Ed) 2017;358:j4008. doi: 10.1136/bmj.j4008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Moher D, Liberati A, Tetzlaff J, Altman DG, The PRISMA Group Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: the PRISMA statement. PLoS Med. 2009;339:2535. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.1000097. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.