Key Points

Question

Does a surgeon’s sex influence the number and types of referrals received from physicians?

Findings

In this cross-sectional study of nearly 40 million referrals to surgeons, female surgeons received nonoperative referrals more often than male surgeons. Male physicians had a strong preference for referring patients to male surgeons; female physicians were less influenced by surgeon sex when making referral decisions, differences that were associated with physician choice rather than with differences in surgeon or patient characteristics.

Meaning

These results suggest that when referring patients to surgeons, male physicians may have biases toward same-sex referrals, thereby disadvantaging female surgeons.

Abstract

Importance

Studies have found that female surgeons have fewer opportunities to perform highly remunerated operations, a circumstance that contributes to the sex-based pay gap in surgery. Procedures performed by surgeons are, in part, determined by the referrals they receive. In the US and Canada, most practicing physicians who provide referrals are men. Whether there are sex-based differences in surgical referrals is unknown.

Objective

To examine whether physicians’ referrals to surgeons are influenced by the sex of the referring physician and/or surgeon.

Design, Setting, and Participants

This cross-sectional, population-based study used administrative databases to identify outpatient referrals to surgeons in Ontario, Canada, from January 1, 1997, to December 31, 2016, with follow-up to December 31, 2018. Data analysis was performed from April 7, 2019, to May 14, 2021.

Exposures

Referring physician sex.

Main Outcomes and Measures

This study compared the proportion of referrals (overall and those referrals that led to surgery) made by male and female physicians to male and female surgeons to assess associations between surgeon, referring physician, or patient characteristics and referral decisions. Discrete choice modeling was used to examine the extent to which sex differences in referrals were associated with physicians’ preferences for same-sex surgeons.

Results

A total of 39 710 784 referrals were made by 44 893 physicians (27 792 [61.9%] male) to 5660 surgeons (4389 [77.5%] male). Female patients made up a greater proportion of referrals to female surgeons than to male surgeons (76.8% vs 55.3%, P < .001). Male surgeons accounted for 77.5% of all surgeons but received 87.1% of referrals from male physicians and 79.3% of referrals from female physicians. Female surgeons less commonly received procedural referrals than male surgeons (25.4% vs 33.0%, P < .001). After adjusting for patient and referring physician characteristics, male physicians referred a greater proportion of patients to male surgeons than did female physicians; differences were greatest among referrals from other surgeons (rate ratio, 1.14; 95% CI, 1.13-1.16). Female physicians had a 1.6% (95% CI, 1.4%-1.9%) greater odds of same-sex referrals, whereas male physicians had a 32.0% (95% CI, 31.8%-32.2%) greater odds of same-sex referrals; differences did not attenuate over time.

Conclusions and Relevance

In this cross-sectional, population-based study, male physicians appeared to have referral preferences for male surgeons; this disparity is not narrowing over time or as more women enter surgery. Such preferences lead to lower volumes of and fewer operative referrals to female surgeons and are associated with sex-based inequities in medicine.

This cross-sectional study of physician referrals to surgeons examines whether the number and types of referrals are influenced by the sex of the referring physician.

Introduction

A pay gap between men and women in medicine is found in virtually every health care system where this has been measured1,2,3,4,5,6,7,8 and is largest for surgeons.4 A substantial proportion of salary disparities are unexplained by factors such as lifestyle and career choices.4,9,10,11,12 A previous study13 found differences in mean hourly remuneration for time spent operating between male and female surgeons in a fee-for-service system, suggesting that female surgeons do not have equal opportunity to perform the most lucrative surgical procedures. Another study14 similarly found that female surgeons have unequal access to expertise-building work, such as complex cases. Because surgeons depend on referrals from other clinicians, systematic bias in the referral process is potentially associated with case-mix differences for surgeons.

Despite the importance of the referral process for patient outcomes and specialist practice, factors that influence referral networks are not well studied. Ideally, referrals should reflect the skill, expertise, and quality of care delivered by the specialist, facilitating timely, geographically accessible care. However, several studies15,16 suggest that unrelated physician characteristics, including sex, are associated with the strength of ties and patient sharing in physician networks, indicating that the referral process may be biased. Homophily, the tendency for similar individuals to associate with each other, appears to be an important determinant of patient sharing. Because most practicing physicians are men,17 such homophily would systematically disadvantage women, resulting in reduced demand for female specialists.18

In the fee-for-service system in Ontario, Canada, referrals are unrestricted by contracts, insurance schemes, or employment. Physicians are free to refer patients to any specialist who accepts patients. Ontario is therefore an ideal setting to explore sex bias in referral networks. The objective of this study was to determine whether physicians’ referrals to surgeons are influenced by the sex of the referring physician.

Methods

Overview

We conducted a population-based, cross-sectional study of outpatient referrals to surgeons in Ontario, Canada, from January 1, 1997, to December 31, 2016, using linked administrative databases. Data were obtained from ICES, an independent, nonprofit institute that houses population-level administrative health data, which are deidentified before analysis. ICES is a prescribed entity under section 45 of Ontario’s Personal Health Information Protection Act. Section 45 authorizes ICES to collect personal health information, without consent, for the purpose of analysis or compiling statistical information with respect to the management, evaluation, or monitoring of; the allocation of resources to; or planning for all or part of the health system. Data analysis was performed from April 7, 2019, to May 14, 2021. The study aimed to compare characteristics of patients referred to male and female surgeons, compare the proportion of referrals made to male and female surgeons, examine whether referring physician and/or surgeon sex influence referral decisions, and quantify the degree to which physician choice drives referral disparities. This study was approved by the St Michael’s Hospital Research Ethics Board. This study followed the Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (STROBE) reporting guideline.19

Referrals

First visits to specialist physicians in Ontario typically require referrals. After consultation, surgeons submit claims for reimbursement to the Ontario Health Insurance Plan. Each consultation billing code includes identifiers for patient, surgeon, and referring physician. We used the Ontario Health Insurance Plan database to identify claims for outpatient consultations submitted by surgeons for the initial patient visit (eMethods in the Supplement); these claims were used as a proxy for referrals. We excluded inpatient consultations and those patients referred by emergency department physicians because these referrals were likely made to the surgeon on call rather than by choice of the referring physician.

Surgeons and Referring Physicians

We captured claims for consultations billed by surgeons practicing general surgery, neurosurgery, orthopedic surgery, plastic surgery, obstetrics-gynecology, ophthalmology, otolaryngology, urology, cardiac surgery, thoracic surgery, and vascular surgery (eMethods in the Supplement). We later excluded physicians practicing cardiac, thoracic, and vascular surgery because these specialties each had fewer than 15 female surgeons across the study period, limiting our ability to evaluate sex differences in referrals. For the remaining specialties, for each referral, we used the Corporate Provider Database to obtain surgeon specialty, age (continuous), sex (male or female), and years of experience (continuous) on the claim date.

We linked the referring physician identifier from consultation claims submitted by surgeons to the Corporate Provider Database to determine the referring physician’s age, sex, years of experience, and specialty (primary care, medical, surgical, or other specialties) (eMethods in the Supplement).

Patient Covariates

Covariates for inclusion were selected a priori based on a theoretical model. We determined patient age, sex, region of residence, income, marginalization, resource use, and comorbidity level at the time of the consultation. Health care services in Ontario are managed by regional health authorities (local health integration networks [LHINs]). We used patients’ LHINs to allocate patients to geographic regions. Income levels were approximated using median neighborhood income estimates (5 groups by income quintile). Degree of marginalization was determined using the Ontario Marginalization Index, a validated, census-based metric that combines measures of material deprivation, residential instability, ethnic concentration, and dependency (with 1 indicating least marginalized and 5 indicating most marginalized); this measure does not explicitly include race and ethnicity of individual patients because these data are not readily available within the datasets used.20 Resource use was classified using resource utilization bands of the Johns Hopkins Adjusted Clinical Group System, version 10.0 (Johns Hopkins University) (with 1 indicating nonuser and 6 indicating very high morbidity).21 Comorbidity status was ascertained using aggregated diagnosis groups of the Adjusted Clinical Group System (categorical, 0-5, 6-10, or >10) (eMethods in the Supplement). We defined procedural referrals as those leading to endoscopic or surgical procedures by the same surgeon within 2 years of consultation and operative referrals as the subset leading to surgery (eMethods in the Supplement). Patients were followed up from the date of consultation to the first procedure or up to 2 years after consultation (the last follow-up was December 31, 2018).

Statistical Analysis

We used descriptive statistics to compare surgeon, referring physician, and patient characteristics. We compared the proportion of procedural and operative referrals between male and female surgeons. We used standardized mean differences (SMDs) to compare groups (SMD >0.1 was considered meaningful). Temporal trends were evaluated using the Cochran-Armitage test.

To examine whether the sex of the referring physician influenced referral choices, we first examined unadjusted measures of homophily. Inbreeding homophily refers to the tendency of individuals to more closely associate with those who are like themselves (eg, male physicians preferring to refer to male surgeons and female physicians preferring female surgeons). To examine inbreeding homophily, we compared the proportion of referrals from male physicians that were made to male surgeons vs the population proportion of male surgeons. Inbreeding homophily was considered present when the proportion of referrals from male physicians to male surgeons was greater than the population proportion of male surgeons. We similarly examined the extent of inbreeding homophily among female physicians. Next, we considered how 3 factors influenced referral decisions: surgeon characteristics, patient characteristics, and physician preferences.

Surgeon Characteristics

We assumed male and female surgeons would exhibit differences in observed characteristics (eg, years of experience) and these characteristics could influence referral decisions (eg, both male and female physicians may prefer to refer to male surgeons who have greater mean experience). In addition, unobserved differences could also influence decisions. If female surgeons work fewer hours or see fewer patients, these factors could limit their referrals. However, these factors should equally affect referrals from male and female physicians. Relative homophily measures whether male and female physicians are equally influenced by observed and unobserved surgeon characteristics (eMethods in the Supplement)18: relative homophily = (proportion of referrals made by male physicians to male surgeons) – (proportion of referrals made by female physicians to male surgeons).

If both male and female physicians refer or overrefer to male surgeons to an equal degree, the relative homophily is 0; if male physicians refer a greater proportion of patients to male surgeons than do female physicians, the relative homophily is greater than 0. We examined the degree of relative homophily across all referrals and stratified by specialties of referring physicians. In a post hoc exploratory analysis, we limited the data set to only those referrals associated with a diagnostic code for a breast-related primary complaint and examined inbreeding and relative homophily within this subset.

Patient Characteristics

Patient characteristics could influence referral decisions. Older, more comorbid patients may preferentially be referred to more experienced surgeons, and patients may themselves have sex-based preferences. To measure relative homophily adjusted for patient factors, we constructed a referring physician-year–level negative binomial model with annual number of referrals to male surgeons as the outcome, the natural logarithm of total annual referrals as the offset, and referring physician– and patient-related characteristics as covariates (eMethods in the Supplement). We included a referring physician specialty × sex interaction. Adjusted absolute proportions of referrals to male surgeons were obtained using mean values of each covariate in the study population; marginal effects at the means approximate an adjusted measure of relative homophily.

Physician Preferences

To examine the extent to which physician preferences influenced referral decisions, we constructed a discrete choice model with case-control sampling.22,23,24 Discrete choice models estimate the probability that a decision maker will select a particular option among alternatives and quantify the influence of characteristics of choices on the probability of selection. Using this approach, we estimated the probability that, all else being equal, referring physicians would make same-sex referrals. For each referral, we identified the year in which the referral was made, the patient’s location (by LHIN), and the surgeon’s specialty. We matched the surgeon who received the referral (cases) 1:1 to a randomly sampled surgeon of the same specialty, who submitted claims in the same year, for patients residing in the same LHIN (controls). Controls represented surgeons who could have been chosen by referring physicians but were not. We then constructed a conditional logit discrete choice model25 to estimate the odds the chosen surgeon was of the same sex as the referring physician. After matching, covariates included were surgeon age, difference in age between referring physician and surgeon, surgeon sex, and surgeon experience; models were stratified by sex of the referring physician. Because the patient- and referring physician-level covariates did not vary within matched sets, these were not included.

In some specialties, male and female surgeons may have differing scopes of practice. We performed a sensitivity analysis excluding 1 specialty at a time from the discrete choice model to ensure that results were robust to latent occupational segregation within specialties. In addition, to examine whether there were temporal or generational differences (ie, decreasing magnitude of bias as more women entered medicine and surgery), we performed a sensitivity analysis of our discrete choice model using data from the most recent 5 years only.

All reported P values are 2-sided; P < .05 was considered statistically significant. Analyses were performed using R, version 3.3 (R Foundation for Statistical Computing), and Stata, version 13.1 (StataCorp).

Results

Surgeons and Referring Physicians

A total of 39 710 784 referrals were made by 44 893 physicians (27 792 [61.9%] male) to 5660 surgeons (4389 [77.5%] male) (eFigure 1 and eTables 1 and 2 in the Supplement)). Male surgeons were older than female surgeons (median age, 49 years; IQR, 41-59 years vs median age, 43 years; IQR, 37-49 years; SMD, 0.66) and had been in practice longer (median, 12.9 years; IQR, 7.7-19.6 years vs median, 9.3 years; IQR, 4.2-15.6 years; SMD, 0.42). Male referring physicians were older than female physicians (median age, 52 years; IQR, 44-60 years vs median, 46 years; IQR, 39-53 years; SMD, 0.57) and had been in practice longer (median, 16.2 years; IQR, 10.2-22.3 years vs median, 12.1; IQR, 6.6-18.9 years; SMD, 0.42). The percentage of female referring physicians increased from 24.2% in 1997 to 43.3% in 2016 (P < .001 for trend) (eFigure 2 in the Supplement).

Patients

The characteristics of the patients referred to male and female surgeons are presented in Table 1. Female surgeons were more often referred female patients than male surgeons (4 633 883 of 6 031 434 [76.8%] vs 18 618 046of 33 679 350 [55.3%]; SMD, 0.47). No meaningful differences were found in the comorbidity level of patients (SMD, 0.04).

Table 1. Characteristics of Patients Referred to Surgeons, Measured at the Time of Consultation (N = 39 710 784)a.

| Characteristic | Patients referred to male surgeons (n = 33 679 350 [84.8%]) | Patients referred to female surgeons (n = 6 031 434 [15.2%]) | Standardized mean difference |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age, y | |||

| ≤30 | 7 375 232 (21.9) | 1 748 078 (29.0) | 0.25 |

| 31-50 | 10 267 295 (30.5) | 2 135 986 (35.4) | |

| 51-70 | 10 695 091 (31.8) | 1 494 822 (24.8) | |

| >70 | 5 341 732 (15.9) | 652 548 (10.8) | |

| Sex | |||

| Male | 15 061 304 (44.7) | 1 397 551 (23.2) | 0.47 |

| Female | 18 618 046 (55.3) | 4 633 883 (76.8) | |

| Income level | |||

| Lowest fifth | 6 467 513 (19.3) | 1 175 453 (19.6) | 0.01 |

| Second fifth | 6 626 350 (19.7) | 1 166 835 (19.4) | |

| Third fifth | 6 684 758 (19.9) | 1 182 956 (19.7) | |

| Fourth fifth | 6 848 204 (20.4) | 1 232 068 (20.5) | |

| Highest fifth | 6 934 093 (20.7) | 1 253 098 (20.8) | |

| Marginalization, median (IQR) | 3.00 (2.50-3.75) | 3.00 (2.50-3.75) | 0.004 |

| Resource utilization band | |||

| Nonuser | 216 337 (0.6) | 68 144 (1.1) | 0.12 |

| Healthy user | 529 896 (1.6) | 90 532 (1.5) | |

| Low morbidity | 3 878 194 (11.5) | 713 408 (11.8) | |

| Moderate morbidity | 20 212 512 (60.0) | 3 469 134 (57.5) | |

| High morbidity | 7 154 969 (21.2) | 1 486 413 (24.6) | |

| Very high morbidity | 1 687 442 (5.0) | 203 803 (3.4) | |

| ADGs | |||

| 0-5 | 14 515 242 (43.1) | 2 655 560 (44.0) | 0.04 |

| 6-10 | 13 674 006 (40.6) | 2 477 861 (41.1) | |

| >10 | 5 490 102 (16.3) | 898 013 (14.9) | |

| Procedural referrals | 11 121 566 (33.0) | 1 532 000 (25.4) | 0.17 |

| General surgery | 3 786 481 (60.3) | 508 947 (53.9) | 0.13 |

| Neurosurgery | 94 706 (18.3) | 5512 (15.3) | 0.08 |

| Orthopedic surgery | 1 185 952 (18.7) | 59 639 (17.9) | 0.02 |

| Plastic surgery | 983 194 (38.7) | 170 900 (35.0) | 0.08 |

| Obstetrics-gynecology | 944 239 (23.7) | 419 513 (16.2) | 0.19 |

| Ophthalmology | 1 320 863 (25.8) | 187 101 (21.1) | 0.11 |

| Otolaryngology | 949 508 (18.1) | 136 257 (20.3) | 0.06 |

| Urology | 1 856 623 (51.0) | 44 131 (54.2) | 0.06 |

Abbreviation: ADGs, aggregated diagnosis groups.

Data are presented as number (percentage) of referred patients unless otherwise indicated.

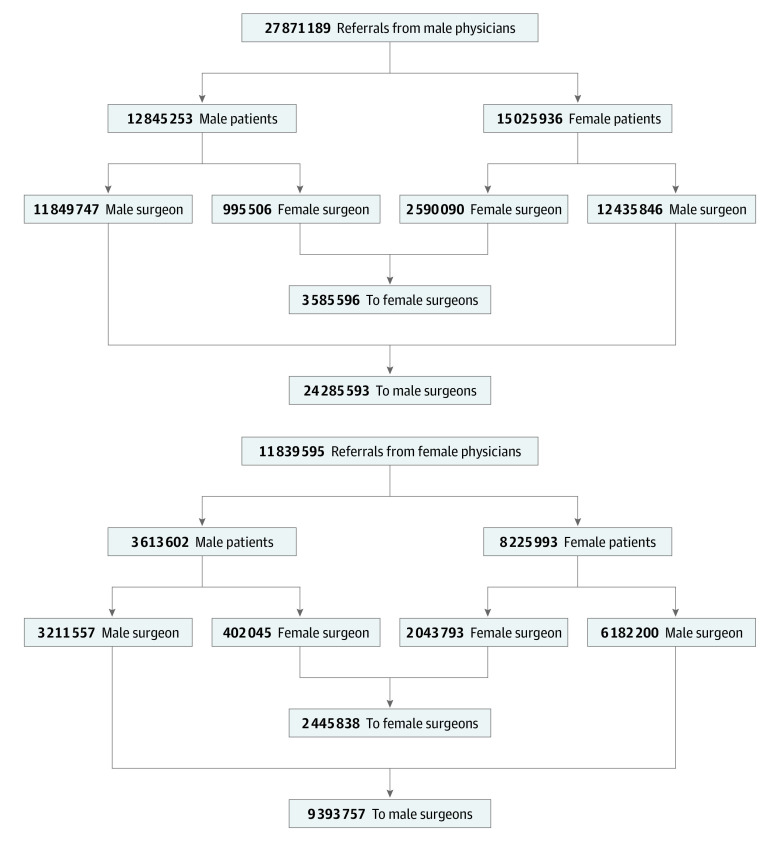

Distribution of Referrals

The distribution pattern of patient referrals is shown in Figure 1. Both male and female physicians referred most patients to male surgeons (87.1% of male physicians and 79.3% of female physicians; P < .001). Male patients were less likely to be referred to a female surgeon than were female patients (8.5% of male patients and 19.9% of female patients; P < .001); male patients seen by male physicians were less likely to be referred to a female surgeon than male patients seen by female physicians (7.7% of male patients seen by male physicians vs 11.1% of male patients seen by female physicians; P < .001).

Figure 1. Distribution of Referred Patients Seen by Male and Female Surgeons.

Overall, female surgeons received fewer procedural referrals than male surgeons (1 532 000 of 6 031 434 [25.4%] vs 11 121 566 of 33 679 350 [33.0%]; SMD, 0.17) (Table 1). The specialties with the largest differences in procedural referrals were obstetrics-gynecology (16.2% vs 23.7%; SMD, 0.19), general surgery (53.9% vs 60.3%; SMD, 0.13), and ophthalmology (21.1% vs 25.8%; SMD, 0.11). When referrals were stratified by specialty of the referring physician, the largest difference was seen among referrals sent by surgeons to surgeons, where 186 199 of 647 649 referrals (28.7%) sent to female surgeons vs 1 259 994 of 3 304 707 referrals (38.1%) sent to male surgeons were procedural (SMD, 0.20) (eTable 3 in the Supplement). When only operative referrals were considered, differences narrowed in general surgery (36.7% vs 41.2%; SMD, 0.09) but widened in urology (20.0% vs 30.9%; SMD, 0.25) (eTable 4 in the Supplement).

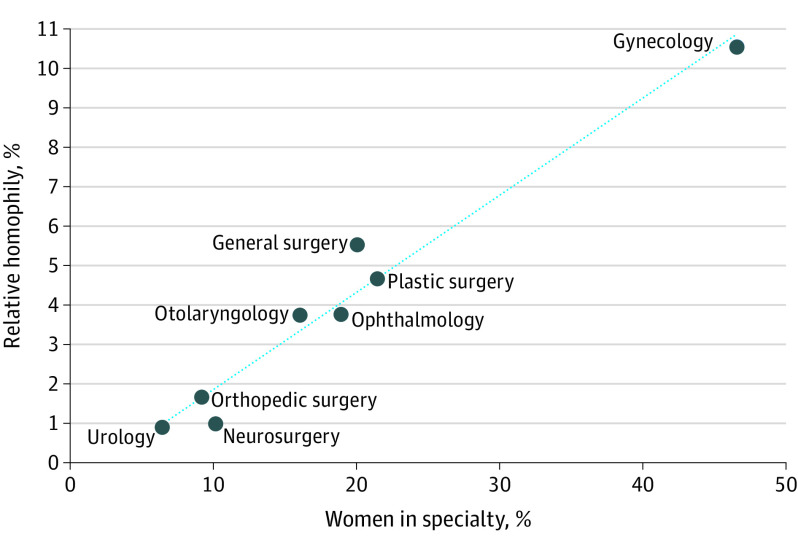

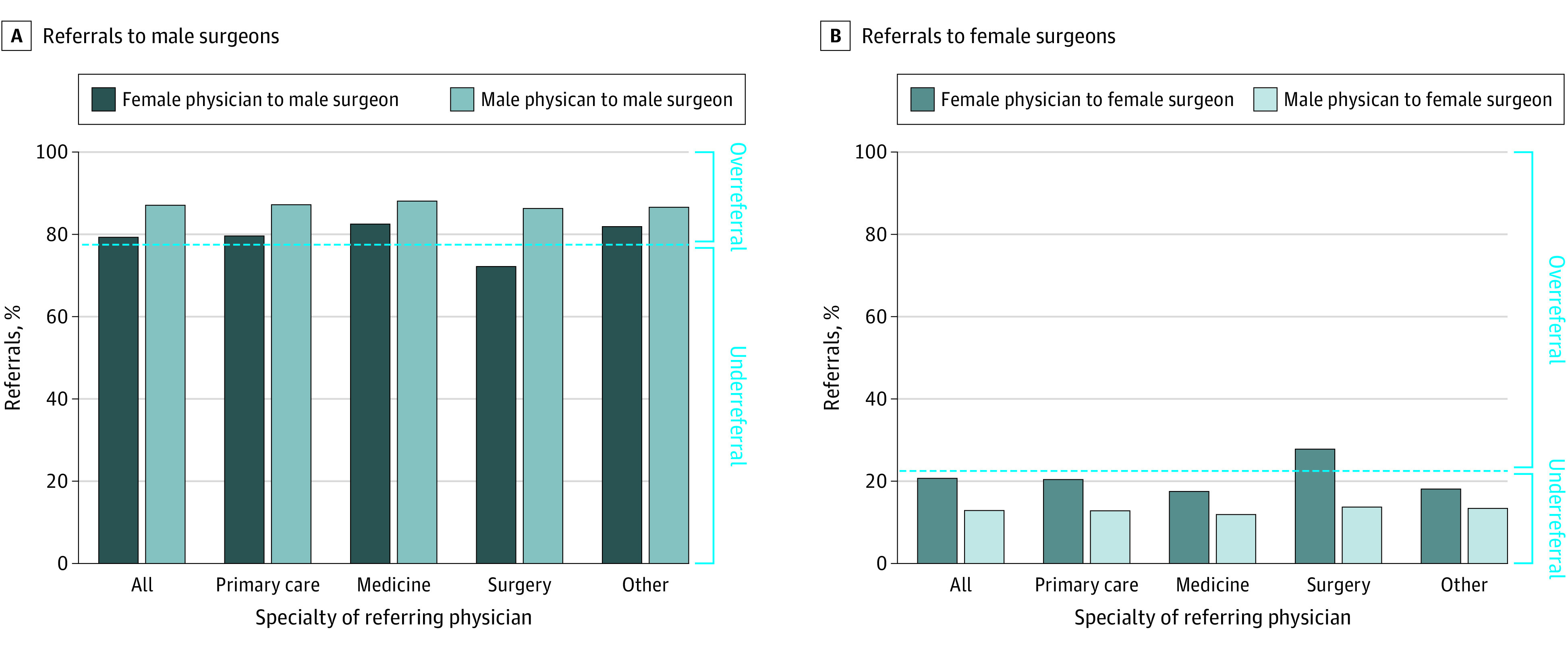

Referral Homophily

Male surgeons accounted for 77.5% of surgeons in the population. Both male and female physicians referred a greater proportion of their patients to male surgeons than the population proportion of male surgeons (Figure 2; eFigure 3 in the Supplement). Inbreeding homophily was seen among male physicians but not among female physicians. Relative homophily was also seen; the absolute difference in the proportion of referrals sent to male surgeons between male and female physicians was 7.8% (87.1% of referrals from male physicians vs 79.3% of referrals from female physicians). Relative homophily was greatest among referrals from surgical specialists (eTable 5 in the Supplement) and increased as the proportion of women in the surgical specialty increased (Figure 3).

Figure 2. Percentage of Referrals From Male and Female Physicians to Male Surgeons and Female Surgeons by Specialty Area of the Referring Physician.

Dashed line represents the percentage of male and female surgeons in the population (77.5% male surgeons and 22.5% female surgeons). Bars above the dashed line represent a greater percentage of referrals to male or female surgeons than their proportion in the population (ie, overreferral). Bars below the dashed line represent a lower percentage of referrals to male or female surgeons than their proportion in the population (ie, underreferral).

Figure 3. Association Between Relative Homophily and Percentage of Female Surgeons.

After adjustment for patient factors and referral year, the sex of the referring physician remained significantly associated with the fraction of referrals sent to male surgeons (eTable 6 in the Supplement). The strength of this association varied by specialty of the referring physician, with the largest difference seen among referrals from other surgeons (RR, 1.14; 95% CI, 1.13-1.16). The adjusted absolute difference (relative homophily) in the percentage of referrals sent to male surgeons by male and female surgeons was 10.5% (95% CI, 9.6%-11.5%) (Table 2).

Table 2. Unadjusted and Adjusted Proportions of Referrals to Male Surgeons at Mean Values of All Covariatesa.

| Specialist type | Referrals, % (95% CI) | |

|---|---|---|

| Unadjusted | Adjusted | |

| Primary care specialists | ||

| Male physicians | 86.4 (86.2-86.5) | 85.5 (85.4-85.6) |

| Female physicians | 78.6 (78.4-78.8) | 81.1 (80.9-81.3) |

| Difference | 7.8 (7.5-8.0) | 4.4 (4.1-4.7) |

| Medical specialists | ||

| Male physicians | 86.6 (86.2-87.0) | 84.5 (84.2-84.9) |

| Female physicians | 82.0 (81.3-82.7) | 82.1 (81.5-82.8) |

| Difference | 4.6 (3.9-5.4) | 2.4 (1.7-3.2) |

| Surgical specialists | ||

| Male physicians | 86.6 (86.2-86.9) | 85.4 (85.1-85.8) |

| Female physicians | 71.8 (70.9-72.8) | 74.9 (74.0-75.8) |

| Difference | 14.8 (13.7-16.8) | 10.5 (9.6-11.5) |

| Other specialists | ||

| Male physicians | 85.7 (85.2-86.1) | 84.8 (84.4-85.3) |

| Female physicians | 79.9 (79.3-80.4) | 81.4 (80.9-82.0) |

| Difference | 3.4 (2.8-4.1) | 3.4 (2.8-4.1) |

Estimates are from negative binomial regression of the annual number of referrals to male surgeons by referring physicians (offset is the total number of referrals), fit using generalized estimating equations to account for clustering by referring physician. Covariates included year of referral, age of referring physician, years of experience of referring physician, percentage of patients older than 50 years, percentage of male patients, percentage of patients with more than 10 aggregated diagnosis groups, percentage of patients with high or very high morbidity level, percentage of patients in the lowest 2 groups of income level, and mean patient marginalization. Unadjusted percentages were derived from the model with sex and specialty area of referring physician as independent variables. Adjusted percentages were derived from a model that incorporated all covariates at their mean values.

Post hoc exploratory analysis limited to only those referrals associated with diagnostic codes related to breast issues suggested inbreeding homophily among female physicians, whereby female surgeons accounted for 26.0% of surgeons seeing patients with breast issues but received 30.7% of referrals from female physicians. No meaningful inbreeding homophily was found among male physicians; male surgeons accounted for 74.0% of surgeons seeing patients with breast issues and received 75.1% of referrals from male physicians. Relative homophily among referrals for breast issues was 5.9%, similar to the relative homophily among all general surgery referrals (5.5%); however, this finding reflects referrals from female physicians to female surgeons.

Influence of Physician Choice

In discrete choice modeling, surgeon age and experience were minimally influential, whereas surgeon sex significantly influenced referral decisions (eTable 7 in the Supplement). Female physicians had 1.6% (95% CI, 1.4%-1.9%) greater odds of referring patients to same-sex surgeons. In contrast, male physicians had 32.0% (95% CI, 31.8%-32.2%) greater odds of referring patients to same-sex surgeons. In a sensitivity analysis that evaluated only the most recent 5 years of data to assess for whether the influence of physician choice was attenuating over time, results were similar; male physicians had 31.4% (95% CI, 31.0%-31.8%) greater odds of referring patients to same-sex surgeons, whereas female physicians had 5.1% (95% CI, 4.7%-5.4%) lower odds of referring patients to same-sex surgeons (eTable 8 in the Supplement). Results were unchanged in a sensitivity analysis that explored the effects of occupational segregation (eTable 9 in the Supplement).

Discussion

Our study, which evaluated nearly 40 million referrals, found that physicians exhibit preferences for male surgeons, and these preferences are strongest among male physicians. Although male surgeons accounted for 77.5% of all surgeons, they received 79.3% of referrals sent by female physicians but 87.1% of referrals sent by male physicians. Female surgeons were less likely to receive referrals and less often received procedural referrals. These disparities could not be explained by differences in patient characteristics or surgeon experience or availability. Rather, they appeared to be associated with physician choice; male physicians had 32.0% greater odds of choosing to refer to a surgeon of the same sex. This finding did not attenuate as more women entered medicine and surgery.

Few studies have investigated factors associated with specialist selection. When surveyed, physicians report the most important factors associated with specialist selection are skill26,27 and quality of care the patient is expected to receive.28 However, how physicians ascertain surgeon skill is unclear29 and possibly open to implicit bias. After adjustment for training and seniority, female surgeons receive fewer new-patient referrals than male surgeons.30 In a study31 of Medicare referrals, when patients of female surgeons had poor outcomes, referrals to female surgeons decreased. This phenomenon was not seen when patients of male surgeons had poor outcomes, suggesting the existence of sex-based differences in perceptions of surgeon skill and culpability for poor patient outcomes.

Our study not only provides evidence of bias but also challenges alternate explanations for observed disparities, for example, that disparities exist because female physicians have lower clinical volumes.32 Although this hypothesis could explain why the proportion of referrals seen by female surgeons was lower than the population proportion of female surgeons, it does not explain why male and female referring physicians differed in the fraction of referrals sent to female surgeons. In addition, it is often assumed that referral patterns reflect patient preferences; patients may prefer same-sex surgeons when undergoing sensitive examinations or diagnostic tests.33,34,35,36,37,38 However, after adjustment for patient sex, substantial differences in the fraction of patients referred to male surgeons by male and female physicians remained. If patient preferences for same-sex surgeons, particularly for sensitive examinations, were alone associated with referral decisions, we would expect that, among referrals for breast issues, there would be an overwhelming proportion of referrals from male physicians to female surgeons; however, this was not seen. Instead, we found that, among breast referrals, male physicians referred patients proportionally to the number of male surgeons. Differences also remained after adjustment for other patient characteristics, suggesting disparities cannot be entirely explained by differences in patient complexity. Finally, our data argue against the notion that sex-based disparities will automatically improve over time as more women enter medicine. The magnitude of overreferral to male surgeons attributable to physician choice remained stable in a sensitivity analysis using only data from the most contemporary subset of our study period. In addition, we found that relative homophily persisted after adjusting for year of referral and was largest in specialties with greater representation of female surgeons. In specialties with few female surgeons, choices of referring physicians are likely too constrained to exhibit sex differences18; as more women enter a specialty, referring physicians can exercise choice, allowing biases to manifest. This finding, that inequity in referrals increased as the proportion of women in a specialty increased, suggests that disparities may widen as more female trainees enter careers in surgery.

Using population-based data, our study systematically examined the contribution of surgeon characteristics, patient characteristics, and physician preferences on referral decisions. Because there are few constraints to referrals in Ontario, this study provides estimates of referral bias independent of extraneous factors.

Limitations

This study has limitations. Our analysis was limited to a single Canadian province; however, a previous study18 suggested similar degrees of bias can be expected in the US. We were unable to ascertain physician gender and relied on biological sex for our analysis; however, given the number of referrals analyzed in this study, we expect that this had little effect on our results. We used claims for consultations as a proxy for referrals and could not capture referrals refused by surgeons. It is possible that female surgeons refused more referrals than male surgeons, leading to the appearance of overreferral to male surgeons. However, such refusals would not explain our finding that male physicians sent a lower fraction of referrals to female surgeons than did female physicians. If male surgeons refuse more referrals, our study underestimates referral disparities. Finally, we did not account for single-entry or next available surgeon referral models; however, such models are rare in Ontario and unlikely to have had a major effect on our results.

Conclusions

This study found that, all else being equal, male physicians referred a greater proportion of patients to male surgeons than to female surgeons and female surgeons received greater fractions of nonoperative referrals. These differences have not attenuated over time and were greatest in surgical specialties with the highest representation of female surgeons, suggesting that disparities will persist, even widen, as more women enter the field of surgery. Differences in referral volume and type can have significant financial ramifications for female surgeons.13 These data, therefore, highlight the need for systematic, focused efforts to reduce the effect of bias on female surgeons, such as through education of physicians on the existence and impact of implicit biases and adoption of single-entry referral models with frequent auditing to ensure equitable case distribution.

eMethods. Supplementary Methods

eTable 1. Surgeon Characteristics

eTable 2. Referring Physician Characteristics

eTable 3. Number and Percentage of Referrals Sent to Male and Female Surgeons That Resulted in a Procedure Within 2 Years of Date of Consultation, by Specialty Area of Referring Physician

eTable 4. Number and Percentage of Referrals to Male and Female Surgeons That Resulted in Surgery Within 2 Years of Consultation, Excluding Endoscopic Procedures

eTable 5. Relative Homophily by Specialty of Surgeon and Referring Physician

eTable 6. Multivariable Analysis of the Association Between Sex of the Referring Physician and Rate of Referrals Made to Male Surgeons

eTable 7. Results of Stratified Conditional Logit Discrete Choice Model

eTable 8. Results of Sensitivity Analysis of Discrete Choice Models Limited to Most Recent 5 Years of Data

eTable 9. Sensitivity Analysis Excluding One Specialty at a Time From Discrete Choice Models to Ensure Results Robust to Latent Occupational Segregation Within Specialties

eFigure 1. Study Flow Diagram

eFigure 2. Percentage of Female Surgeons and Female Referring Physicians Across the Study Period (All Specialties)

eFigure 3. Proportion of Referrals From Male and Female Physicians to Male Surgeons and Female Surgeons, by Specialty Area of the Referring Physician and Specialty of Surgeon

References

- 1.Appleby J. Gender pay gap in England’s NHS: little progress since last year. BMJ. 2019;365:l2089. doi: 10.1136/bmj.l2089 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bayati M, Rashidian A, Sarikhani Y, Lohivash S. Income inequality among general practitioners in Iran: a decomposition approach. BMC Health Serv Res. 2019;19(1):620. doi: 10.1186/s12913-019-4473-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Dumontet M, Le Vaillant M, Franc C. What determines the income gap between French male and female GPs—the role of medical practices. BMC Fam Pract. 2012;13(1):94. doi: 10.1186/1471-2296-13-94 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Jena AB, Olenski AR, Blumenthal DM. Sex differences in physician salary in US public medical schools. JAMA Intern Med. 2016;176(9):1294-1304. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2016.3284 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Mainardi GM, Cassenote AJF, Guilloux AGA, Miotto BA, Scheffer MC. What explains wage differences between male and female Brazilian physicians? a cross-sectional nationwide study. BMJ Open. 2019;9(4):e023811. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2018-023811 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Miao Y, Li L, Bian Y. Gender differences in job quality and job satisfaction among doctors in rural western China. BMC Health Serv Res. 2017;17(1):848. doi: 10.1186/s12913-017-2786-y [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Rad EH, Ehsani-Chimeh E, Gharebehlagh MN, Kokabisaghi F, Rezaei S, Yaghoubi M. Higher income for male physicians: findings about salary differences between male and female Iranian physicians. Balkan Med J. 2019;36(3):162-168. doi: 10.4274/balkanmedj.galenos.2018.2018.1082 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Seabury SA, Chandra A, Jena AB. Trends in the earnings of male and female health care professionals in the United States, 1987 to 2010. JAMA Intern Med. 2013;173(18):1748-1750. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2013.8519 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Jagsi R, Griffith KA, Stewart A, Sambuco D, DeCastro R, Ubel PA. Gender differences in the salaries of physician researchers. JAMA. 2012;307(22):2410-2417. doi: 10.1001/jama.2012.6183 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ducharme J. The gender pay gap for doctors is getting worse. here’s what women make compared to men. Published 2019. Accessed October 31, 2019. https://time.com/5566602/doctor-pay-gap/

- 11.Glauser W. Why are women still earning less than men in medicine? Published 2018. Accessed October 31, 2019. https://www.cmaj.ca/content/190/21/E664 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 12.Izenberg D, Oriuwa C, Taylor M. . Why is there a gender wage gap in Canadian medicine? Published 2018. Accessed October 31, 2019. https://healthydebate.ca/2018/10/topic/gender-wage-gap-medicine

- 13.Dossa F, Simpson AN, Sutradhar R, et al. Sex-based disparities in the hourly earnings of surgeons in the fee-for-service system in Ontario, Canada. JAMA Surg. 2019;154(12):1134-1142. doi: 10.1001/jamasurg.2019.3769 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Zhang B, Westfal ML, Griggs CL, Hung YC, Chang DC, Kelleher CM. Practice patterns and work environments that influence gender inequality among academic surgeons. Am J Surg. 2020;220(1):69-75. doi: 10.1016/j.amjsurg.2019.10.029 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.DuGoff EH, Cho J, Si Y, Pollack CE. Geographic variations in physician relationships over time: implications for Care Coordination. Med Care Res Rev. 2018;75(5):586-611. doi: 10.1177/1077558717697016 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Landon BE, Keating NL, Barnett ML, et al. Variation in patient-sharing networks of physicians across the United States. JAMA. 2012;308(3):265-273. doi: 10.1001/jama.2012.7615 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Association of American Medical Colleges . 2018. Physician Specialty Data Report Executive Summary. Published 2018. Accessed October 31, 2019. https://www.aamc.org/system/files/2019-08/2018executivesummary.pdf

- 18.Zeltzer D. Gender homophily in referral networks: consequences for the Medicare physician earnings gap. Am Econ J Appl Econ. 2020;12(2):169-197. doi: 10.1257/app.20180201 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 19.von Elm E, Altman DG, Egger M, Pocock SJ, Gøtzsche PC, Vandenbroucke JP; STROBE Initiative . The Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (STROBE) statement: guidelines for reporting observational studies. Bull World Health Organ. 2007;85(11):867-872. doi: 10.2471/BLT.07.045120 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Matheson F, Dunn J, Smith K, Moineddin R, Glazier R. Ontario Marginalization Index: User Guide. Public Health Ontario; 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Weiner J. The Johns Hopkins ACG Case-Mix System Version 6.0 Release Notes. Johns Hopkins University Bloomberg School of Public Health, Health Services Research & Development Center; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Manski CF, Lerman SR. The estimation of choice probabilities from choice based samples. Econometrica. 1977;45(8):1977-1988. doi: 10.2307/1914121 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 23.McFadden DL. Econometric analysis of qualitative response models. In: Handbook of Econometrics. Vol 2. Elsevier; 1984:1395-1457. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Scott AJ, Wild C. Fitting logistic models under case-control or choice based sampling. J R Stat Soc Series B Stat Methodol. 1986;48(2):170-182. doi: 10.1111/j.2517-6161.1986.tb01400.x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 25.McFadden D. Conditional logit analysis of qualitative choice behavior. Front Econometrics. 1973:105-142. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kinchen KS, Cooper LA, Levine D, Wang NY, Powe NR. Referral of patients to specialists: factors affecting choice of specialist by primary care physicians. Ann Fam Med. 2004;2(3):245-252. doi: 10.1370/afm.68 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Javalgi R, Joseph WB, Gombeski WR Jr, Lester JA. How physicians make referrals. J Health Care Mark. 1993;13(2):6-17. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Ludke RL. An examination of the factors that influence patient referral decisions. Med Care. 1982;20(8):782-796. doi: 10.1097/00005650-198208000-00003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Choudhry NK, Liao JM, Detsky AS. Selecting a specialist: adding evidence to the clinical practice of making referrals. JAMA. 2014;312(18):1861-1862. doi: 10.1001/jama.2014.12963 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Chen YW, Westfal ML, Chang DC, Kelleher CM. Contribution of unequal new patient referrals to female surgeon under-employment. Am J Surg. 2021;222(4):746-750. doi: 10.1016/j.amjsurg.2021.02.028 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Sarsons H. Interpreting signals in the labor market: evidence from medical referrals (Job Market Paper). Harvard University working paper. Updated November 28, 2017. Accessed October 31, 2019. https://scholar.harvard.edu/sarsons/publications/interpreting-signals-evidence-medical-referrals

- 32.Mahr MA, Hayes SN, Shanafelt TD, Sloan JA, Erie JC. Gender differences in physician service provision using Medicare claims data. Mayo Clinic Proc. 2017;92(6):870-880. doi: 10.1016/j.mayocp.2017.02.017 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Groutz A, Amir H, Caspi R, Sharon E, Levy YA, Shimonov M. Do women prefer a female breast surgeon? Isr J Health Policy Res. 2016;5:35. doi: 10.1186/s13584-016-0094-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Amir H, Beri A, Yechiely R, Amir Levy Y, Shimonov M, Groutz A. Do urology male patients prefer same-gender urologist? Am J Mens Health. 2018;12(5):1379-1383. doi: 10.1177/1557988316650886 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Plunkett BA, Kohli P, Milad MP. The importance of physician gender in the selection of an obstetrician or a gynecologist. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2002;186(5):926-928. doi: 10.1067/mob.2002.123401 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Huis in’t Veld EA, Canales FL, Furnas HJ. The impact of a plastic surgeon’s gender on patient choice. Aesthet Surg J. 2016;37(4):466-471. doi: 10.1093/asj/sjw180 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Kerssens JJ, Bensing JM, Andela MG. Patient preference for genders of health professionals. Soc Sci Med. 1997;44(10):1531-1540. doi: 10.1016/s0277-9536(96)00272-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Cil TD, Easson AM. The role of gender in patient preference for breast surgical care—a comment on equality. Isr J Health Policy Res. 2018;7(1):37. doi: 10.1186/s13584-018-0231-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

eMethods. Supplementary Methods

eTable 1. Surgeon Characteristics

eTable 2. Referring Physician Characteristics

eTable 3. Number and Percentage of Referrals Sent to Male and Female Surgeons That Resulted in a Procedure Within 2 Years of Date of Consultation, by Specialty Area of Referring Physician

eTable 4. Number and Percentage of Referrals to Male and Female Surgeons That Resulted in Surgery Within 2 Years of Consultation, Excluding Endoscopic Procedures

eTable 5. Relative Homophily by Specialty of Surgeon and Referring Physician

eTable 6. Multivariable Analysis of the Association Between Sex of the Referring Physician and Rate of Referrals Made to Male Surgeons

eTable 7. Results of Stratified Conditional Logit Discrete Choice Model

eTable 8. Results of Sensitivity Analysis of Discrete Choice Models Limited to Most Recent 5 Years of Data

eTable 9. Sensitivity Analysis Excluding One Specialty at a Time From Discrete Choice Models to Ensure Results Robust to Latent Occupational Segregation Within Specialties

eFigure 1. Study Flow Diagram

eFigure 2. Percentage of Female Surgeons and Female Referring Physicians Across the Study Period (All Specialties)

eFigure 3. Proportion of Referrals From Male and Female Physicians to Male Surgeons and Female Surgeons, by Specialty Area of the Referring Physician and Specialty of Surgeon