Abstract

Objective: To determine the effect of glucagon-like peptide-1 receptor agonist (GLP-1RA) on cases with type 2 diabetes mellitus (T2DM) in terms of insulin dosage and blood glucose (BG) control. Methods: A total of 180 patients with T2DM admitted to our hospital between March 2016 and March 2019 were selected and assigned to a GLP-1RA group (GLP-1 group, n=100) and a control group (control group, n=80). Patients in the GLP-1 group were treated with GLP-1RA combined with insulin, while those in the other group were treated with insulin alone. The following items of each patient were determined: Body weight, body mass index (BMI), waist circumference, blood pressure (BP), BG-related indexes, insulin dosage, insulin resistance index, cardiovascular function, serum lipid-related indexes, adverse reactions, total effective rate, and treatment satisfaction. Results: Compared with the control group, the GLP-1 group showed a decrease in weight, BMI, waist circumference, BP, BG-related indexes, and insulin resistance index, consumed less insulin dosage, and also showed a decline in cardiovascular function, serum lipid-related indexes (total cholesterol (TC), triacylglycerol (TG), and low density lipoprotein cholesterol (LDL-C)), an increase in high density lipoprotein cholesterol (HDL-C), less adverse reactions, and higher total effective rate and treatment satisfaction. Conclusion: GLP-1RA contributes to better BG control of patients with T2DM, and it reduces the insulin dosage required during operation for its stimulation to the production of insulin.

Keywords: GLP-1RA, type 2 diabetes mellitus, insulin, BMI

Introduction

Diabetes mellitus (TM) is a common malady [1]. It is estimated that more than 415 million adults are affected by TM worldwide. The prevalence rate of this disease is still on the rise, and the number of patients with the disease is expected to increase to 640 million in the next 20-30 years [2,3]. Type 2 diabetes mellitus (T2DM), a kind of TM, is related to atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease, which is the main risk factor for lesions of great vessels and micro-vessels, and is prone to cause kidney diseases and even increase mortality in severe cases [4,5]. For the purpose of reducing the risk of vascular complications caused by TM, it is necessary to control blood glucose (BG). However, the benefits of BG control to great vessels are uncertain, and the safety of regulating BG concentration raises people’s concern [6,7]. Here, we decided to investigate a regulator, glucagon-like peptide-1 receptor agonist (GLP-1RA).

GLP-1RA is a drug which is able to effectively change BG concentration [8]. This hypoglycemic agent, which acts on incretin hormone GLP-1, is widely used in the treatment of T2DM. GLP-1 is an endocrine cell-secreted intestinal hormone in the gastrointestinal tract. It stimulates insulin secretion and regulates appetite by affecting the appetite-regulating areas of the cerebral center after food intake. GLP-1RA can ameliorate BG by inhibiting the secretion of glucagon and stimulating the production of insulin by regulation on GLP-1 [9-11]. In addition, GLP-1RA can protect the kidney to a certain extent, because it can reduce the risk of cardiovascular diseases by regulating BG [12,13]. Therefore, for patients with cardiovascular or kidney diseases, it is a favorable choice to adopt GLP-1RA for treatment, and in fact, GLP-1RA is often adopted with oral therapy and basic insulin [14,15]. In the present study, we studied the effect of GLP-1RA on patients with T2DM by evaluating the insulin dosage and BG concentration of the patients.

Methods and materials

General materials

(1) General materials: A total of 180 patients with T2DM admitted to Haian Hospital Affiliated to Nantong University between March 2016 and March 2019 were selected and assigned to a GLP-1RA group (GLP-1 group, n=100) and a control group (control group, n=80). Patients in the GLP-1 group were treated with GLP-1RA combined with insulin, while those in the control group were treated with insulin alone. There was no notable difference between the two groups in the above general information (all P>0.05), so the two groups were comparable. This study was carried out with permission from the Ethics Committee of our hospital, and patients and their families voluntarily signed written informed consents after understanding the study.

(2) Inclusion and exclusion criteria: The inclusion criteria of the study: Patients meeting the diagnostic criteria for T2DM and meeting relevant treatment indications in the 2019 Guidance for Prevention and Treatment of Type II Diabetes Mellitus in China [16], patients with comparatively complete clinical data, patients whose fasting BG (FBG) was still higher than 7.0 mmol/L after 7 days of diet control and 2 hour postprandial BG (2hPG) was still higher than 11.1 mmol/L after the 7 days. The exclusion criteria of the study: Patients between 18 and 75 years old, patients without T2DM, patients during pregnancy, patients with other comorbid autoimmune diseases, patients with severe organic diseases, blood coagulation dysfunction, hepatic or kidney function obstacle, or malignant tumor, patients with mental disease or consciousness disorder, patients unwilling to cooperate with treatment, and those with relevant treatment contraindications.

Treatment methods

Each patient in the two groups received basic treatment after admission as follows: Each patient orally took metformin hydrochloride tablets (trade name: Glucophage, Sino-American Shanghai Squibb Pharmaceutical Co., Ltd., SFDA approval number: H20023370) at 1.0-1.5 g/d during meals.

Patients in the control group were treated with insulin aspart 30 as follows: Each patient was subcutaneously injected with 16U insulin aspart 30 (manufacturer: Novo Nordisk A/S; specification: 100 U/mL and 3 ml/piece; SFDA approval number: S20133006) at 10 min before breakfast and 8 U insulin aspart 30 at 10 min before supper. The specific dosage was adjusted according to the BG level of the patient. Each patient was treated for 6 consecutive months, and then the efficacy on the patient was evaluated.

Patients in the other group were treated with GLP-1RA based on the treatment to the control group. The administration plan and dosage of insulin aspart 30 for patients in the GLP-1 group were the same as those for patients in the control group. On this basis, each patient was subcutaneously injected with GLP-1RA, liraglutide (manufacturer: Novo Nordisk (China) Pharmaceutical Co., Ltd.; specification: 3 ml: 18 mg; SFDA approval number: J20110026) at an initial dose of 0.6 mg/d, once before sleep each day. The dosage was increased to 1.2 mg/d within 7-14 days based on the BG level of the patient. Each patient was also treated for 6 consecutive months, and then the efficacy on the patient was evaluated.

Detection indexes

(1) Body weight, body mass index (BMI), waist circumference, and blood pressure (BP): The changes of body weight, BMI, waist circumference, and BP of the two groups before treatment and after 6 months of treatment were compared.

(2) BG-related indexes: BG-related indexes of the two groups before treatment and after 6 months of treatment were evaluated and compared. BG-related indexes included FBG, 2hPG, and glycosylated hemoglobin (HbA1c).

(3) Insulin dosage and insulin resistance index (IRI): The IRI (Homa IR) of the two groups before and after 6 months of treatment was compared. The IRI (Homa IR) = FPG × FINS/22.5. A lower index indicated better situation of the patient. In addition, the average insulin dosage (FINS) used for each patient before treatment and after 3 months of treatment were calculated.

(4) Cardiovascular function: The cardiovascular function indicators such as left ventricular ejection fraction (LVEF) and diastolic rate of brachial artery blood vessel of the two groups before treatment and after 6 months of treatment were compared. Diastolic rate of brachial artery blood vessel = (maximum diastolic diameter of vessel-vessel diameter in basic state) × vessel diameter in basic state × 100%.

(5) Level of serum lipid-related indexes: The levels of serum lipid-related indexes of the two groups before therapy and after 6 months of treatment were analyzed and compared. The indexes included total cholesterol (TC), triacylglycerol (TG), low density lipoprotein cholesterol (LDL-C), and high density lipoprotein cholesterol (HDL-C).

(6) Adverse reactions: Adverse reactions including nausea, diarrhea, vomiting, abdominal pain, and hypoglycemia of the two groups were counted and compared.

(7) Total effective rate: The total effective rates of both groups were calculated. The criteria for evaluation of the rate were as follows: Markedly effective: FPG<7.1 mmol/L and 2hPPG<8.3 mmol/L or FPG and 2hPPG were reduced by more than 30% after treatment. Effective: The clinical symptoms were ameliorated and FPG<8.3 mmol/L and 2hPPG<10.0 mmol/L, or FPG and 2hPPG were reduced by more than 10%-29%; ineffective: No significant change was seen in symptoms and BG. Total effective rate = (the rate of markedly effective treatment + the rate of effective treatment).

(8) Satisfaction: When the patients were discharged from the hospital, the satisfaction degree of the patients was investigated using a self-made questionnaire, which used a score of 90-100 points for satisfaction, a score of 70-90 points for moderate satisfaction, and a score less than 70 points for dissatisfaction.

Statistical analyses

The data were analyzed comprehensively and statistically using SPSS19.0 (Asia Analytics Formerly SPSS, China). Enumeration data were analyzed using the X2 test, and measurement data were presented by the (X±S), and analyzed by the t test. P<0.05 indicates a notable difference.

Results

General materials

There was no significant difference between the two groups in general information including sex, age, smoking history, drinking history, hypertension history, and hyperlipidemia history (all P>0.05) (Table 1).

Table 1.

General information of the two groups

| Item | The GLP-1 group (n=100) | The control group (n=80) | t/X2 | P |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sex | 1.82 | 0.177 | ||

| Male | 53 (53.00) | 48 (60.00) | ||

| Female | 47 (47.00) | 32 (40.00) | ||

| Age (Y) | 53.75±4.49 | 54.13±4.78 | 0.55 | 0.584 |

| Course of disease (Y) | 8.21±3.56 | 8.45±3.74 | 0.44 | 0.661 |

| Smoking | 0.16 | 0.689 | ||

| Yes | 48 (48.00) | 36 (45.00) | ||

| No | 52 (52.00) | 44 (55.00) | ||

| Drinking | 0.36 | 0.549 | ||

| Yes | 71 (71.00) | 60 (75.00) | ||

| No | 29 (29.00) | 20 (25.00) | ||

| Hyperlipidemia | 0.64 | 0.424 | ||

| Yes | 89 (89.00) | 68 (85.00) | ||

| No | 11 (11.00) | 12 (15.00) | ||

| Hypertension | 0.12 | 0.733 | ||

| Yes | 82 (82.00) | 64 (80.00) | ||

| No | 18 (18.00) | 16 (20.00) |

Changes of body weight, BMI, waist circumference, and BP

Investigation on the changes of body weight, BMI, waist circumference, and BP of the two groups revealed that after treatment, both groups presented notable changes in these indexes, and these indexes of the GLP-1 group were all significantly lower than those of the control group (all P<0.05) (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Changes of body weight, BMI, waist circumference, as well as BP. A. Body weight: After treatment, both groups presented notable changes in body weight, and the body weight of the GLP-1 group was greatly lower than that of the control group (P<0.05). B. BMI: After treatment, both groups presented notable changes in BMI, and the BMI of the GLP-1 group was greatly lower than that of the control group (P<0.05). C. Waist circumference: After treatment, both groups presented notable changes in waist circumference, and the waist circumference of the GLP-1 group was greatly lower than that of the control group (P<0.05). D. Systolic blood pressure: After treatment, both groups presented notable changes in systolic blood pressure, and the pressure of the GLP-1 group was greatly lower than that of the control group (P<0.05). E. Diastolic blood pressure: After treatment, both groups presented notable changes in diastolic blood pressure, and the pressure of the GLP-1 group was greatly lower than that of the control group (P<0.05). Notes: * indicates P<0.05 vs. the situation before treatment; & indicates P<0.05 vs. the control group.

BG-related indexes

FBG, 2hPG, and HbA1c in the two groups were investigated, and it was found that after treatment, the levels of them in both groups chang ed significantly, and levels of them in the GLP-1 group were greatly lower than those in the control group (all P<0.05) (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Changes of BG-related indexes of the two groups. A. FBG: After treatment, the level of FBG in both groups changed significantly, and the level in the GLP-1 group was greatly lower than that in the control group (P<0.05). B. 2hPG: After treatment, the level of 2hPG in both groups changed greatly, and the level in the GLP-1 group was greatly lower than that in the control group (P<0.05). C. HbA1c: After treatment, level of HbA1c in both groups changed significantly, and the level in the GLP-1 group was greatly lower than that in the control group (P<0.05). Notes: * indicates P<0.05 vs. the situation before treatment; & indicates P<0.05 vs. the control group.

Insulin dosage and IRI

Homa IR and insulin dosage of the two group were investigated, and it was found that after treatment, the levels of Homa IR and insulin dosage of both groups changed significantly, while the level of Homa IR in the GLP-1 group was greatly lower than that in the control group (P<0.05), and the insulin dosage used for the GLP-1 group was also greatly less than that used for the control group (P<0.05) (Figure 3).

Figure 3.

Changes of Homa IR and insulin dosage of the two groups. A. Homa IR: After treatment, the level of Homa IR in both groups changed significantly, and the level in the GLP-1 group was greatly lower than that in the control group (P<0.05). B. Insulin dosage: After treatment, the insulin dosage used for both groups was changed significantly, and the insulin dosage used for the GLP-1 group was greatly less than that used for the control group (P<0.05). Notes: * indicates P<0.05 vs. the situation before treatment; & indicates P<0.05 vs. the control group.

Cardiovascular function

The LVEF and diastolic rate of brachial artery blood vessel of the two groups were evaluated, and it was found that after treatment, the LVEF and diastolic rate of brachial artery blood vessel of both group changed significantly, and the levels of the two in the GLP-1 group were greatly higher than those in the control group (both P<0.05) (Figure 4).

Figure 4.

Cardiovascular function of the two groups. A. LVEF: After treatment, LVEF of both groups changed significantly, and the LVEF level in the GLP-1 group was greatly higher than that in the control group (P<0.05). B. Diastolic rate of brachial artery blood vessel: After treatment, the diastolic rate of brachial artery blood vessel of both groups changed significantly, and the rate of the GLP-1 group was greatly higher than that of the control group (P<0.05). Notes: * indicates P<0.05 vs. the situation before treatment; & indicates P<0.05 vs. the control group.

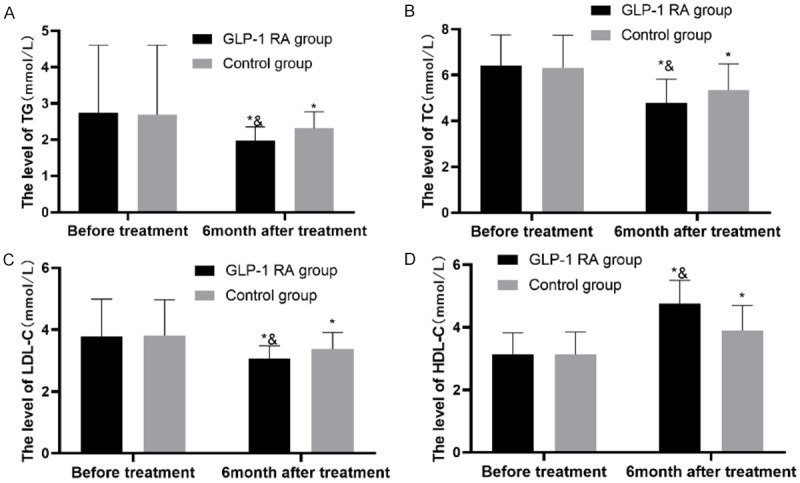

Levels of serum lipid-related indexes

TG, TC, LDL-C, and HDL-C in the two groups were quantified, and it was found that after treatment, the levels of them in the two groups changed significantly, and the levels of TG, TC, and LDL-C in the GLP-1 group were greatly lower than those in the control group, while the HDL-C level in the GLP-1 group was greatly higher than that in the control group (P<0.05) (Figure 5).

Figure 5.

Changes in serum lipid-related indexes of the two groups. A. TG: After treatment, the level of TG in both groups changed significantly, and the level in the GLP-1 group was greatly lower than that in the control group (P<0.05). B. TC: After treatment, the level of TC in both groups changed significantly, and the level in the GLP-1 group was greatly lower than that in the control group (P<0.05). C. LDL-C: After treatment, the level of LDL-C in both groups changed greatly, and the level in the GLP-1 group was greatly lower than that in the control group (P<0.05). D. HDL-C: After treatment, the level of HDL-C in both groups changed significantly, and the level in the GLP-1 group was greatly higher than that in the control group (P<0.05). Notes: * indicates P<0.05 vs. the situation before treatment; & indicates P<0.05 vs. the control group.

Evaluation of adverse reactions

According to investigation on the incidence of adverse reactions in the two groups, the incidence in the GLP-1 group was greatly lower than that in the control group (P<0.05) (Table 2).

Table 2.

Comparison of complication rate between the two groups

| Item | The GLP-1 group (n=100) | The control group (n=80) | X2 | P-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Nausea | 2 (2.00) | 4 (5.00) | - | - |

| Diarrhea | 1 (1.00) | 2 (2.50) | - | - |

| Vomiting | 0 (0.00) | 2 (2.50) | ||

| Abdominal pain | 1 (0.00) | 2 (2.50) | ||

| Hypoglycemia | 0 (0.00) | 4 (5.00) | - | - |

| Incidence of adverse reactions (%) | 4 (4.00) | 14 (17.50) | 9.00 | 0.003 |

Total effective rate

According to investigation on the total effective rate of the two groups, the rate of the GLP-1 group was greatly higher than that of the control group, implying that the GLP-1 group experienced better recovery than the control group (P<0.05) (Table 3).

Table 3.

Total effective rates of the two groups

| Item | The GLP-1 group (n=100) | The control group (n= 80) | X2 | P-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Markedly effective | 72 (72.00) | 36 (45.00) | - | - |

| Effective | 26 (26.00) | 34 (42.50) | - | - |

| Ineffective | 2 (2.00) | 10 (12.50) | - | - |

| Total effective rate (%) | 98 (98.00) | 70 (87.05) | 7.88 | 0.005 |

Treatment satisfaction

According to comparison of treatment satisfaction between the two groups, the GLP-1 group showed significantly higher satisfaction than the control group (P<0.05) (Table 4).

Table 4.

Satisfaction of the two groups

| Item | The GLP-1 group (n=100) | The control group (n=80) | X2 | P-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Satisfaction | 79 (79.00) | 42 (52.50) | - | - |

| Moderate satisfaction | 17 (16.00) | 24 (30.00) | - | - |

| Dissatisfaction | 4 (4.00) | 14 (17.50) | - | - |

| Satisfaction (%) | 96 (93.75) | 59 (81.94) | 10.43 | 0.001 |

Discussion

In order to achieve successful treatment of T2DM, it usually requires controlling of both BG and overweight and obesity, which increases the risk of cardiovascular diseases [17]. This study analyzed the influence of GLP-1 RA on insulin dosage and BG control of patients with T2DM, particularly focusing on a discussion about BG control and solution of cardiovascular problems.

In terms of solving cardiovascular problems, according to general data about body weight, waist circumference and BMI, patients enrolled in this study were basically obese. Obese is prone to induce cardiovascular problems. In addition, many of the patients suffered from hypertension and hyperlipidemia. Compared with the control group, the GLP-1 group performed better in the control of obesity, changes of serum lipid-related indexes, and recovery of cardiovascular function. Compared with normal individuals, patients with DM face higher risks of death and danger when suffering from cardiovascular disease [18]. Obesity, hypertension, and dyslipidemia are known risk factors of cardiovascular diseases, and patients with TM are more likely to develop cardiovascular disease than those without TM [19-21]. Moreover, patients with T2DM face a risk of death when suffering from cardiovascular disease [22]. Lipid abnormality is a crucial physiological mechanism in T2DM, which is closely related to the levels of serum lipid-related indexes such as TG and HDL-C. TG and HDL-C are closely linked in patients with T2DM. Increase in TG will trigger the catabolism of HDL. In addition, T2DM can easily induce low-grade chronic inflammation, and may affect the level of plasma lipid, and inflammation stimulates the secretion of TG in the liver, degrades HDL, and lowers its level [23]. Lipid abnormality in patients with T2DM is characterized by an increase in blood lipids such as TG and a decrease in HDL-C, which leads to an elevation in insulin resistance and in the levels of BG-related indexes [24]. GLP-1 can strongly stimulate insulin secretion, so GLP-1RA can be used to treat TM. In addition to the ability of treating TM, GLP-1RA has a good therapeutic effect on obesity by regulating the appetite of hypothalamus, and its regulation on LDL-C, TC, and HDL-C can ameliorate the content of blood lipids, so it can lower risks associated with cardiovascular and cerebrovascular diseases faced by patients [25,26]. The above can explain why the GLP-1 group performed better than the control group treated with insulin alone in terms of obesity, blood lipid, cardiovascular function, and other indexes. The results of this study were good evidences for the ability of GLP-1RA in solving a series of cardiovascular problems caused by obesity.

In term of BG control, BG control of the GLP-1 group was better than that of the control group. The levels of BG-related indexes in the GLP-1 group were superior to those in the control group. In addition, after 3 months of treatment, the insulin dosage used for the GLP-1 group was less, and after 6 months of treatment, the IRI of the GLP-1 group was lower. GLP-1 can suppress appetite and energy intake, and its function of promoting the secretion of insulin can effectively reduce insulin resistance. High IRI can not only easily lead to weigh gain of patients, but also easily make the glucose in blood hard to decompose by insulin because of the antagonistic effect on insulin, which will give rise to an increase in glucose content [27]. Therefore, GLP-1RA can lower the BG level by reducing insulin resistance. Moreover, GLP-1RA can also help control BG through other mechanisms. In addition to stimulating insulin secretion, GLP-1RA can also reduce BG by inhibiting glucagon level, and its inhibition on appetite can inhibit the increase of BG. Furthermore, GLP-1RA is relatively safe, because it brings about few adverse reactions such as hypoglycemia [28]. GLP-1RA can lower BG level by stimulating the production of insulin, so therapy with GLP-1RA requires much less insulin. The insulin aspart used in the control group can also lower BG, but if insulin aspart is used too much during treatment, hypoglycemia will easily occur, and insulin alone is not beneficial to the treatment of cardiovascular diseases [29]. Moreira et al. have found that adoption of GLP-1RA based on insulin is safe for patients, and can also lower the weight of patients and the frequency of hypoglycemia [30]. Similar to our study, one study by Yaribeygi et al. [31] has found that with a good antihyperglycaemic effect, GLP-1RA can promote insulin secretion while inhibiting glucagon secretion and can show down gastric emptying. As comparison of the two studies shows, GLP-1RA can control blood glucose by stimulating insulin production, so treatment combined with GLP-1RA can reduce the requirement of insulin. Such a combined treatment can not only achieve a better effect, stimulate patient’s own insulin secretion to return to normal, but also avoid negative effects of insulin therapy, so its safety can be guaranteed.

This study also has limitations. We have not analyzed the degree of cooperation of patients during surgery. Additionally, due to the limitations of various conditions, we have not studied the deeper molecular mechanism triggered by GLP-1RA. Therefore, we will understand the patient’s emotions and the degree of cooperation in order to better improve the treatment plan in future studies. In future studies, it is also necessary to determine the effect of GLP-1RA on inflammatory factors in other molecular mechanisms, so as to further understand the specific mechanism of GLP-1RA on diabetes mellitus and its safety to patients. To sum up, GLP-1RA contributes to better BG control of patients with T2DM, and it reduces the insulin dosage required during operation because of its stimulation to the production of insulin. In addition, GLP-1RA is safe, and can ameliorate obesity, so it is worthy of clinical promotion.

Disclosure of conflict of interest

None.

References

- 1.Akinci B. Dapagliflozin and cardiovascular outcomes in type 2 diabetes. N Engl J Med. 2019;380:1881. doi: 10.1056/NEJMc1902837. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.American Diabetes Association. 9. Cardiovascular disease and risk management: standards of medical care in diabetes-2018. Diabetes Care. 2018;41:S86–S104. doi: 10.2337/dc18-S009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.American Diabetes Association. 8. pharmacologic approaches to glycemic treatment: standards of medical care in diabetes-2018. Diabetes Care. 2018;41:S73–S85. doi: 10.2337/dc18-S008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.de Boer IH, Rue TC, Hall YN, Heagerty PJ, Weiss NS, Himmelfarb J. Temporal trends in the prevalence of diabetic kidney disease in the United States. JAMA. 2011;305:2532–2539. doi: 10.1001/jama.2011.861. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Wanner C, Lachin JM, Inzucchi SE, Fitchett D, Mattheus M, George J, Woerle HJ, Broedl UC, von Eynatten M, Zinman B EMPA-REG OUTCOME Investigators. Empagliflozin and progression of kidney disease in type 2 diabetes. N Engl J Med. 2016;375:323–334. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1515920. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Holman RR, Sourij H, Califf RM. Cardiovascular outcome trials of glucose-lowering drugs or strategies in type 2 diabetes. Lancet. 2014;383:2008–2017. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(14)60794-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Marso SP, Daniels GH, Brown-Frandsen K, Kristensen P, Mann JF, Nauck MA, Nissen SE, Pocock S, Poulter NR, Ravn LS, Steinberg WM, Stockner M, Zinman B, Bergenstal RM, Buse JB, Committee LS, Investigators LT. Liraglutide and cardiovascular outcomes in type 2 diabetes. N Engl J Med. 2016;375:311–322. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1603827. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Prasad-Reddy L, Isaacs D. A clinical review of GLP-1 receptor agonists: efficacy and safety in diabetes and beyond. Drugs Context. 2015;4:212283. doi: 10.7573/dic.212283. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Smits MM, Tonneijck L, Muskiet MH, Kramer MH, Cahen DL, van Raalte DH. Gastrointestinal actions of glucagon-like peptide-1-based therapies: glycaemic control beyond the pancreas. Diabetes Obes Metab. 2016;18:224–235. doi: 10.1111/dom.12593. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Tonneijck L, Smits MM, Muskiet MHA, Hoekstra T, Kramer MHH, Danser AHJ, Diamant M, Joles JA, van Raalte DH. Acute renal effects of the GLP-1 receptor agonist exenatide in overweight type 2 diabetes patients: a randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Diabetologia. 2016;59:1412–1421. doi: 10.1007/s00125-016-3938-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Iepsen EW, Have CT, Veedfald S, Madsbad S, Holst JJ, Grarup N, Pedersen O, Brandslund I, Holm JC, Hansen T, Signe S, Torekov SS. GLP-1 receptor agonist treatment in morbid obesity and type 2 diabetes due to pathogenic homozygous melanocortin-4 receptor mutation: a case report. Cell Rep Med. 2020;1:100006. doi: 10.1016/j.xcrm.2020.100006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Holman RR, Bethel MA, Mentz RJ, Thompson VP, Lokhnygina Y, Buse JB, Chan JC, Choi J, Gustavson SM, Iqbal N, Maggioni AP, Marso SP, Ohman P, Pagidipati NJ, Poulter N, Ramachandran A, Zinman B, Hernandez AF, Group ES. Effects of once-weekly exenatide on cardiovascular outcomes in type 2 diabetes. N Engl J Med. 2017;377:1228–1239. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1612917. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Tonneijck L, Muskiet MHA, Smits MM, Bjornstad P, Kramer MHH, Diamant M, Hoorn EJ, Joles JA, van Raalte DH. Effect of immediate and prolonged GLP-1 receptor agonist administration on uric acid and kidney clearance: Post-hoc analyses of four clinical trials. Diabetes Obes Metab. 2018;20:1235–1245. doi: 10.1111/dom.13223. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Introduction: standards of medical care in diabetes-2019. Diabetes Care. 2019;42:S1–S2. doi: 10.2337/dc19-Sint01. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Rose TN, Jacobs ML, Reid DJ, Bouwmeester CJ, Conley MP, Fatehi B, Matta TM, Barr JT. Real-world impact on monthly glucose-lowering medication cost, HbA1c, weight, and polytherapy after initiating a GLP-1 receptor agonist. J Am Pharm Assoc (2003) 2020;60:31–38.e1. doi: 10.1016/j.japh.2019.09.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Jia W, Weng J, Zhu D, Ji L, Lu J, Zhou Z, Zou D, Guo L, Ji Q, Chen L, Chen L, Dou J, Guo X, Kuang H, Li L, Li Q, Li X, Liu J, Ran X, Shi L, Song G, Xiao X, Yang L, Zhao Z Chinese Diabetes Society. Standards of medical care for type 2 diabetes in China 2019. Diabetes Metab Res Rev. 2019;35:e3158. doi: 10.1002/dmrr.3158. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Frias JP, Bastyr EJ 3rd, Vignati L, Tschop MH, Schmitt C, Owen K, Christensen RH, DiMarchi RD. The Sustained effects of a dual GIP/GLP-1 receptor agonist, NNC0090-2746, in patients with type 2 diabetes. Cell Metab. 2017;26:343–352.e2. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2017.07.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Del Olmo-Garcia MI, Merino-Torres JF. GLP-1 receptor agonists and cardiovascular disease in patients with type 2 diabetes. J Diabetes Res. 2018;2018:4020492. doi: 10.1155/2018/4020492. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kim CS, Ko SH, Kwon HS, Kim NH, Kim JH, Lim S, Choi SH, Song KH, Won JC, Kim DJ, Cha BY Taskforce Team of Diabetes Fact Sheet of the Korean Diabetes Association. Prevalence, awareness, and management of obesity in Korea: data from the Korea national health and nutrition examination survey (1998-2011) Diabetes Metab J. 2014;38:35–43. doi: 10.4093/dmj.2014.38.1.35. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ko SH, Kwon HS, Kim DJ, Kim JH, Kim NH, Kim CS, Song KH, Won JC, Lim S, Choi SH, Han K, Park YM, Cha BY Taskforce Team of Diabetes Fact Sheet of the Korean Diabetes Association. Higher prevalence and awareness, but lower control rate of hypertension in patients with diabetes than general population: the fifth korean national health and nutrition examination survey in 2011. Diabetes Metab J. 2014;38:51–57. doi: 10.4093/dmj.2014.38.1.51. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Roh E, Ko SH, Kwon HS, Kim NH, Kim JH, Kim CS, Song KH, Won JC, Kim DJ, Choi SH, Lim S, Cha BY Taskforce Team of Diabetes Fact Sheet of the Korean Diabetes Association. Prevalence and management of dyslipidemia in korea: korea national health and nutrition examination survey during 1998 to 2010. Diabetes Metab J. 2013;37:433–449. doi: 10.4093/dmj.2013.37.6.433. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Cha SA, Yun JS, Lim TS, Min K, Song KH, Yoo KD, Park YM, Ahn YB, Ko SH. Diabetic cardiovascular autonomic neuropathy predicts recurrent cardiovascular diseases in patients with type 2 diabetes. PLoS One. 2016;11:e0164807. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0164807. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kozakova M, Morizzo C, Goncalves I, Natali A, Nilsson J, Palombo C. Cardiovascular organ damage in type 2 diabetes mellitus: the role of lipids and inflammation. Cardiovasc Diabetol. 2019;18:61. doi: 10.1186/s12933-019-0865-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Sengsuk C, Sanguanwong S, Tangvarasittichai O, Tangvarasittichai S. Effect of cinnamon supplementation on glucose, lipids levels, glomerular filtration rate, and blood pressure of subjects with type 2 diabetes mellitus. Diabetol Int. 2016;7:124–132. doi: 10.1007/s13340-015-0218-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Holst JJ, Madsbad S. Mechanisms of surgical control of type 2 diabetes: GLP-1 is key factor. Surg Obes Relat Dis. 2016;12:1236–1242. doi: 10.1016/j.soard.2016.02.033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Castellana M, Cignarelli A, Brescia F, Perrini S, Natalicchio A, Laviola L, Giorgino F. Efficacy and safety of GLP-1 receptor agonists as add-on to SGLT2 inhibitors in type 2 diabetes mellitus: a meta-analysis. Sci Rep. 2019;9:19351. doi: 10.1038/s41598-019-55524-w. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Muller M, Hernandez MAG, Goossens GH, Reijnders D, Holst JJ, Jocken JWE, van Eijk H, Canfora EE, Blaak EE. Circulating but not faecal short-chain fatty acids are related to insulin sensitivity, lipolysis and GLP-1 concentrations in humans. Sci Rep. 2019;9:12515. doi: 10.1038/s41598-019-48775-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kalra S, Das AK, Sahay RK, Baruah MP, Tiwaskar M, Das S, Chatterjee S, Saboo B, Bantwal G, Bhattacharya S, Priya G, Chawla M, Brar K, Raza SA, Aamir AH, Shrestha D, Somasundaram N, Katulanda P, Afsana F, Selim S, Naseri MW, Latheef A, Sumanatilleke M. Consensus recommendations on GLP-1 RA use in the management of type 2 diabetes mellitus: south asian task force. Diabetes Ther. 2019;10:1645–1717. doi: 10.1007/s13300-019-0669-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Blumer I, Clement M. Type 2 diabetes, hypoglycemia, and basal insulins: ongoing challenges. Clin Ther. 2017;39:S1–11. doi: 10.1016/j.clinthera.2016.09.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Moreira RO, Cobas R, Lopes Assis Coelho RC. Combination of basal insulin and GLP-1 receptor agonist: is this the end of basal insulin alone in the treatment of type 2 diabetes? Diabetol Metab Syndr. 2018;10:26. doi: 10.1186/s13098-018-0327-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Yaribeygi H, Sathyapalan T, Sahebkar A. Molecular mechanisms by which GLP-1RA and DPP-4i induce insulin sensitivity. Life Sci. 2019;234:116776. doi: 10.1016/j.lfs.2019.116776. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]