Abstract

Objective: To innvestigate the rehabilitation effects of repetitive transcranial magnetic stimulation (rTMS) combined with cognitive training on cognitive impairment in patients with traumatic brain injury (TBI) by using multimodal magnetic resonance imaging. Methods: Clinical data of 166 patients with cognitive impairment after TBI were retrospectively analyzed. The patients were assigned into an observation group and a control group according to different treatment methods, with 83 cases in each group. The observation group was given rTMS + cognitive training, and the control group was given cognitive training only. The changes in GCS score, the Cho/Cr, Cho/NAA and NAA/Cr ratios examined by MRSI, the score of cognitive impairment, the grading of cognitive impairment, and the changes in modified Barthel index were observed and compared between the two groups. Results: The GCS score, and the ratios of Cho/Cr, Cho/NAA and NAA/Cr after treatment were better than those before treatment in both groups and were lower in the observation group compared with the control group (all P<0.05). The score and grading of cognitive impairment as well as modified Barthel index after treatment were all significantly better in the observation group than in the control group (all P<0.05). Conclusion: rTMS can improve the rehabilitation effect on cognitive impairment in patients after TBI and is recommended for clinical use.

Keywords: Cognitive impairment after traumatic brain injury, multimodal magnetic resonance imaging, cognitive training, rehabilitation effect

Introduction

In recent years, with the development of social industrialization, injuries and deaths caused by traffic and infrastructure have been increasing year by year, among which traumatic brain injury (TBI) is the leading cause of deaths caused by traumatic injury [1-4]. TBI refers to organic damage on brain tissues caused by external force on the head, mostly from accidents, showing poor prognosis and a very high mortality rate (close to 30%) [5-7]. TBI is clinically difficult to treat and has various complications, posing a serious impact on the quality of life in patients as well as an economic and medical burden to the family and the society [8,9].

With the rapid progress of critical care medicine, emergency medicine and nursing medicine, the current rescue rate of patients after TBI has effectively increased, but those with craniocerebral injury can have varying degrees of cognitive impairment [10]. Study has shown that the incidence of TBI-related cognitive dysfunction is as high as 42.8% [11]. Therefore, the treatment to improve cognitive dysfunction is of great significance for the quality of life of patients after TBI. Repeated transcranial magnetic stimulation (rTMS) can continuously stimulate the cerebral cortex to inhibit or activate neuronal cells, thereby reorganizing the neural network after brain injury and improving cognitive dysfunction in patients after TBI [12]. Nowadays, the assessment of cognitive dysfunction in patients after TBI is mostly subjective, which is susceptible to personality, speech function and cognitive function, etc., leading to a reduced accuracy of the assessment [13]. Magnetic resonance spectrum imaging (MRSI) can non-invasively determine biochemical and metabolic indicators in the brain, such as the ratios of metabolites in the frontal lobe, temporal lobe and corpus callosum. The dynamically changes of the ratios are of great significance for the diagnosis and treatment of TBI, because they objectively reflect the changes in nerve tissues during the treatment and accurately evaluate the clinical treatment effects of rTMS combined with cognitive training on cognitive impairment [14]. Therefore, this study investigated the rehabilitation effect of rTMS combined with cognitive training on cognitive impairment by using multimodal magnetic resonance imaging, hoping to improve the diagnosis and treatment of cognitive dysfunction in patients after TBI.

Materials and methods

General data

Clinical data of 166 patients with cognitive impairment after craniocerebral injury admitted to the Department of Neurorehabilitation, Neurosurgery and ICU of our hospital from January 2018 to January 2020 were retrospectively analyzed. The patients were grouped into observation group and control group according to different treatment methods. Patients were eligible if they had a history of trauma; were diagnosed with brain injury by imaging with cognitive dysfunction; were aged 20-70 years old; were educated in junior high school or above; had stable breathing and circulation; had no history of cardiovascular diseases. Patients were excluded if they had a history of mental illness, head surgery, epilepsy or meningitis; were unable to complete the survey due to hearing or speech barriers; had cognitive impairment before the injury. The two groups of patients and their families signed an informed consent form. This study was approved by the ethics committee of our hospital (approval number: Medical Ethics Review [2020] No. 12 (01)).

Methods

Both groups received treatments including, firstly, conventional protection of nerve tissues using 0.1 g/tablet mecobalamin (Eisai Pharmaceutical Co., Ltd., China), one tablet each time, twice a day; secondly, strengthening of nerve cell nutrition with 0.2 g/tablet citicoline (Shandong Lukang Chenxin Pharmaceutical Co., Ltd., China), one tablet each time, three times a day; thirdly, improvement of brain metabolism, anti-inflammation and enteral nutrition support with the use of 500 mL/bottle enteral nutritional suspension from Nutricia Pharmaceutical Co., Ltd., Wuxi, China (the dosage was according to the patients weight); lastly, conscious-promoted rehabilitation with the use of 5 mL/piece Xingnaojing (Jimin Kexin Shanhe Pharmaceutical Co., Ltd., Wuxi, China), 2 mL each time, twice a day.

The rehabilitation methods were as follows. The control group received cognitive training for three months. The training included, first, concentration improvement through visual tracking training; second, memory improvement by image method, third, space and visual perception training through various map operations; Last, other trainings such as judgment and reasoning, business plan, income and expenditure. Patients in the observation group were treated also with rTMS in addition to the cognitive training. An rTMS therapy instrument (Tonica, Denmark) was used to stimulate the healthy prefrontal area, with an “8” shape stimulation circle coil, a stimulation intensity of 80% resting motion threshold and a low frequency of 1 Hz. The stimulation included a total of 75 sequences and 750 pulses, with a sequence interval of 2 seconds. Each treatment was 15 minutes, and the treatment was performed once per day, 5 days a week for three months.

Outcome measures

The evaluation of relevant indicators was carried out after three months of treatment.

There were two sets of main outcome measures. The Glasgow Coma Scale (GCS) was evaluated in the both groups before and after treatment [15]. GCS includes eye-opening response, language response and limb movement, with a total score of 15 points. Higher score indicated deeper coma. The changes in the ratios of Cho/Cr, Cho/NAA and NAA/Cr were examined by MRSI. Increase in Cho/Cr, NAA/CR and NAA/Cr indicated brain injury.

There were three secondary outcome measures. Mini-mental state examination (MMSE) scale was used to access the cognitive impairment of the two groups of patients. Higher score indicated severer cognitive impairment. Cognitive impairment grading scale included three degrees (mild, moderate and severe). Changes in modified Barthel index were also compared. Higher score indicated better quality of life [16-18]. Favorable rate of cognitive impairment treatment = cases of (no symptom + mild degree + moderate degree)/number of cases in the group *100%.

Statistical analysis

All data were analyzed using SPSS22.0 statistical analysis software. Figures were plotted using GraphPad Prism 7 and Adobe AI. Measurement data were expressed as mean ± standard deviation (mean ± sd) and compared between groups using independent sample t test. Count data were expressed as percentage (n, %) and compared between groups using chi-square test. A difference of P<0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

Comparison of baseline data between the two groups

There were no significant differences in age, gender, hypertension, diabetes, cause of injury or GCS score between the two groups (all P>0.05), so the two groups were comparable. See Table 1 for details.

Table 1.

Comparison of baseline data between the two groups (n, mean ± sd)

| Group | Sex (male/female) | Age (year) | GCS score (point) | Cause of injury (n) | Hypertension (n) | Diabetes (n) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||||||

| Car accident | Fall injury | Concussion injury | ||||||

| Observation group (n=83) | 48/35 | 57.8±3.8 | 13.50±2.12 | 49 | 31 | 3 | 9 | 6 |

| Control group (n=83) | 45/38 | 58.0±3.9 | 13.34±1.93 | 52 | 27 | 4 | 7 | 3 |

| t/χ2 | 0.098 | 0.335 | 0.643 | 0.384 | 0.069 | 0.470 | ||

| P | 0.754 | 0.738 | 0.521 | 0.825 | 0.793 | 0.493 | ||

Comparison of the ratio of metabolites in frontal white matter between the two groups

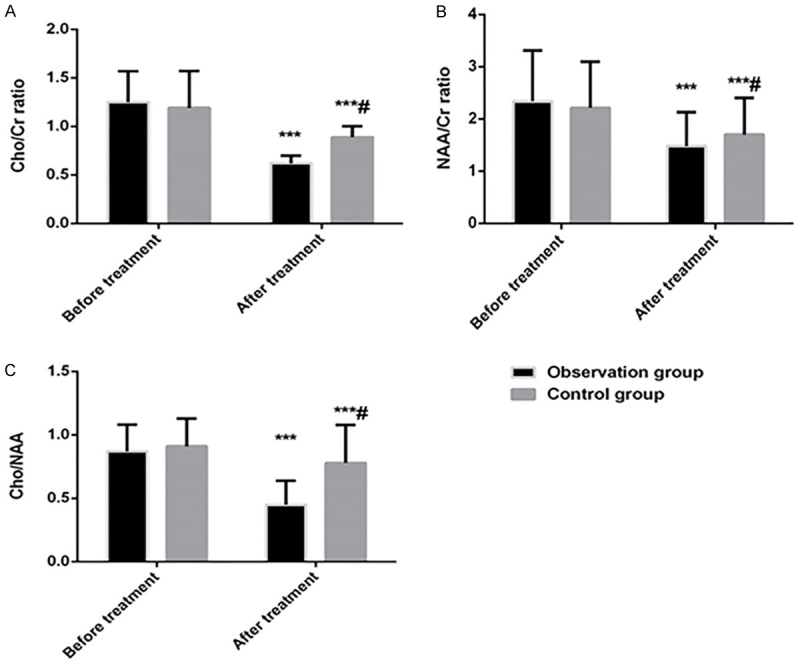

Before treatment, there was no statistical difference in the ratio of metabolites in frontal white matter (Cho/Cr, Cho/NAA and NAA/Cr) between the two groups (P=0.273, P=0.368 and P=0.379, respectively). After treatment, the ratios were decreased significantly in both groups compared with those before treatment (all P<0.001), and the results were better in the observation group than in the control group (all P<0.05). See Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Comparison of the ratio of metabolites in frontal white matter between the two groups. A: Comparison of Cho/Cr ratio between two groups before and after treatment; B: Comparison of NAA/Cr ratio between the two groups before and after treatment; C: Comparison of the ratio of Cho/NAA between the two groups before and after treatment. Compared with before treatment, ***P<0.001; compared with observation group, #P<0.05.

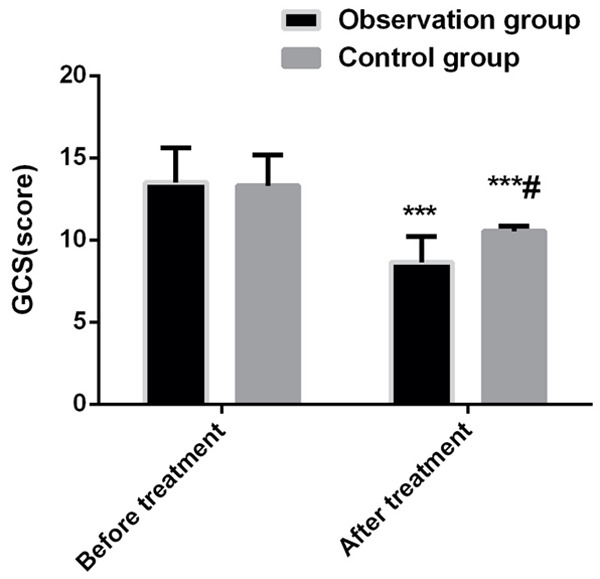

Comparison of GCS scores between two groups before and after treatment

In terms of GCS, there was no significant difference between the two groups of patients before treatment (P>0.05). After treatment, the GCS scores in both groups were significantly lower than those before treatment (both P<0.001), and the decrease was more significant in the observation group than in the control group (P<0.05). See Figure 2.

Figure 2.

Comparison of GCS scores between two groups before and after treatment. Compared with before treatment, ***P<0.001; compared with observation group, #P<0.05.

Comparison of cognitive function between the two groups before and after treatment

In terms of cognitive function, there was no significant difference between the two groups of patients before treatment (P>0.05). After treatment, the MMSE scores in both groups were significantly higher than those before treatment (both P<0.001), and the increase was more significant in the observation group than in the control group (P<0.001). In addition, the grading results of cognitive impairment were better in the observation group than those in the control group (P<0.05). See Tables 2 and 3.

Table 2.

Comparison of MMSE scores between the two groups before and after treatment (mean ± sd)

| Before treatment | Before treatment (point) | After treatment (point) | t | P |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Observation group (n=83) | 18.57±4.67 | 24.78±2.34 | 10.831 | <0.001 |

| Control group (n=83) | 18.21±4.53 | 20.45±2.11 | 4.084 | <0.001 |

| t | 0.504 | 12.520 | - | - |

| P | 0.615 | <0.001 | - | - |

Note: MMSE: mini-mental state examination.

Table 3.

Grading of cognitive impairment after treatment in the two groups (n, %)

| Group | Cognitive impairment (n) | Favorable rate | χ2 | P | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||||||

| No symptom | Mild | Moderate | Severe | ||||

| Observation group (n=83) | 10 | 41 | 29 | 3 | 80/83 (96.40%) | 4.691 | 0.030 |

| Control group (n=83) | 8 | 32 | 31 | 12 | 71/83 (85.54%) | ||

Comparison of activities of daily living between the two groups before and after treatment

In terms of activities of daily living, the scores of Barthel index between the two groups were not statistically different before treatment (P>0.05). After treatment, the scores of Barthel index were significantly higher in both groups than those before treatment (both P<0.001), and the score was higher in the observation group than in the control group (P<0.001). See Table 4.

Table 4.

Comparison of activities of daily living between the two groups (mean ± sd)

| Before treatment | Before treatment (point) | After treatment (point) | t | P |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Observation group (n=83) | 27.45±2.56 | 36.62±3.01 | 21.142 | <0.001 |

| Control group (n=83) | 28.33±3.41 | 31.43±2.89 | 6.318 | <0.001 |

| t | 1.880 | 11.331 | - | - |

| P | 0.062 | <0.001 | - | - |

Discussion

As a global clinical disease, TBI is difficult to treat and may lead to many complications and poor quality of life and bring economic and medical burdens to patients’ families and the society [19,20]. At present, functional recovery in the later stage is the main treatment expectation, which mainly includes two parts, motor function and cognitive function. Recovering cognitive function is the difficulty and focus of rehabilitation, and patient’s cognitive ability can also affect the recovery of motor ability to a certain extent [21,22].

The cause of TBI-related cognitive dysfunction is excitatory amino acids binding to their corresponding receptors which causes intracellular calcium overload and nerve cell death [23,24]. In addition, neuronal cell edema and energy metabolism disorders caused by traumatic stress can aggravate the cognitive dysfunction in patients [25,26].

The results of this study showed that after rTMS, the GCS score as well as the score and grading of cognitive impairment of the observation group were better than those of the control group, which preliminarily showed that transcranial magnetic stimulation can improve the clinical treatment effect in patients after TBI. The possible reason is that continuous stimulation at the same frequency and intensity by rTMS gives uninterrupted excitement or inhibition on neuronal cells, which helps to reorganize the neural network after brain injury, thereby improving clinical symptoms. Our results are consistent with previous studies on repetitive transcranial stimulation, which showed that stimulating neuronal cells improved the recovery of the patient’s mental function, thereby increasing GCS score and cognitive function-related scores [27,28].

A previous study preliminarily confirmed that TBI-related cognitive dysfunction was associated with protein energy metabolism, which manifested as changes in material metabolism, presenting increasing choline/creatine and N-Acetate aspartate/creatine in MRSI [29]. The results of our study also showed that the material metabolism indexes of the two groups of patients decreased after treatment, and the decreases were more significant in the observation group than in the control group. It is indicated that rTMS combined with cognitive training can improve the clinical treatment effect on cognitive dysfunction. The possible reason is that rTMS enhances cerebral cortex blood flow and tissue energy metabolism, reduces cell apoptosis and improves synaptic transmission. Scholars have also confirmed that rTMS can improve neuronal tissue metabolism through continuous stimulation, thereby improving cognitive dysfunction in patients with TBI [30].

Barthel index is the main indicator for evaluating the recovery of TBI-related cognitive dysfunction. The results of this study showed that the activities of daily living in the observation group were better than those of the control group, possibly because the combination of rTMS and cognitive training improves cognitive function and communication, which is helpful for the recovery of limb motor function. This finding is the same as the results of previous research that rTMS could improve the patient’s motor function [31].

However, there are still some limitations in this study. First, this is a single-center study with small sample size, so a multi-center large sample study is needed to further confirm the treatment effect of rTMS for TBI-related cognitive impairment. Second, the correlation between the degree of TBI and the effect of rTMS treatment is yet to be elucidated. Third, objective serological indicators should be detected for the accurate evaluation of the treatment effect of rTMS.

The innovation of this study is that we connected the recovery of cognitive dysfunction with the recovery of limb function during the rehabilitation of patients after TBI. Meanwhile, MRSI is used to assess the recovery of the neurological function, thereby accurately evaluating the clinical rehabilitation effect.

In conclusion, rTMS can improve the energy metabolism of neuronal cells in patients after TBI, thereby enhancing the recovery effect on cognitive impairment, and thus, rTMS may be used as clinical adjuvant treatment.

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by the Youth Science Foundation Projects of National Nature Science Foundation of China for the Molecular mechanism of high-frequency rTMS in reduction cortical neurons apoptosis by activating the Wnt/Ca2+/PKC Signaling Pathway via NRF1 transcriptional regulation in Alzheimer’s disease (82002388).

Disclosure of conflict of interest

None.

References

- 1.Kramer N, Lebowitz D, Walsh M, Ganti L. Rapid sequence intubation in traumatic brain-injured adults. Cureus. 2018;10:e2530. doi: 10.7759/cureus.2530. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Robba C, Galimberti S, Graziano F, Wiegers EJA, Lingsma HF, Iaquaniello C, Stocchetti N, Menon D, Citerio G. Tracheostomy practice and timing in traumatic brain-injured patients: a CENTER-TBI study. Intensive Care Med. 2020;46:983–994. doi: 10.1007/s00134-020-05935-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Zhang Y, Sun X, Zhai X, Zhang H, Zhang X. Effects of growth hormone on acetylcholine and dopamine pathways in traumatic brain injured rats. Minerva Med. 2020;111:186–189. doi: 10.23736/S0026-4806.19.06071-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Galimberti S, Robba C, Graziano F, Citerio G. Tracheostomy in traumatic brain injured: solving the conundrum of the immortal time bias. Intensive Care Med. 2020;46:1288–1289. doi: 10.1007/s00134-020-06016-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Griffin AD, Turtzo LC, Parikh GY, Tolpygo A, Lodato Z, Moses AD, Nair G, Perl DP, Edwards NA, Dardzinski BJ, Armstrong RC, Ray-Chaudhury A, Mitra PP, Latour LL. Traumatic microbleeds suggest vascular injury and predict disability in traumatic brain injury. Brain. 2019;142:3550–3564. doi: 10.1093/brain/awz290. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Shi K, Zhang J, Dong JF, Shi FD. Dissemination of brain inflammation in traumatic brain injury. Cell Mol Immunol. 2019;16:523–530. doi: 10.1038/s41423-019-0213-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Suarez-Pierre A, Crawford TC, Zhou X, Lui C, Fraser CD 3rd, Etchill E, Sharma K, Higgins RS, Whitman GJ, Kilic A, Choi CW. Impact of Traumatically brain-injured donors on outcomes after heart transplantation. J Surg Res. 2019;240:40–47. doi: 10.1016/j.jss.2019.02.049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lakschmi R, Miller HE, Hameed BJ, Pauldhas D, Curran AL, Mccarter RJ, Sharples PM. Psychological status at 1, 6 and 12 months in children with severe/moderate and mild traumatic brain injury (TBI) and non-injured controls: relationship to injury severity, healthrelated quality of life (HRQL), socio-economic status and family burden. Dev Med Child Neurol. 2009:10–11. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Veenith TV, Carter EL, Geeraerts T, Grossac J, Newcombe VF, Outtrim J, Gee GS, Lupson V, Smith R, Aigbirhio FI, Fryer TD, Hong YT, Menon DK, Coles JP. Pathophysiologic mechanisms of cerebral ischemia and diffusion hypoxia in traumatic brain injury. JAMA Neurol. 2016;73:542–550. doi: 10.1001/jamaneurol.2016.0091. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lee HY, Jung KI, Yoo WK, Ohn SH. Global synchronization index as an indicator for tracking cognitive function changes in a traumatic brain injury patient: a case report. Ann Rehabil Med. 2019;43:106–110. doi: 10.5535/arm.2019.43.1.106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hoane MR. Assessment of cognitive function following magnesium therapy in the traumatically injured brain. Magnes Res. 2007;20:229–236. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lu X, Bao X, Li J, Zhang G, Guan J, Gao Y, Wu P, Zhu Z, Huo X, Wang R. High-frequency repetitive transcranial magnetic stimulation for treating moderate traumatic brain injury in rats: a pilot study. Exp Ther Med. 2017;13:2247–2254. doi: 10.3892/etm.2017.4283. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Cavinato M, Iaia V, Piccione F. Repeated sessions of sub-threshold 20-Hz rTMS. Potential cumulative effects in a brain-injured patient. Clin Neurophysiol. 2012;123:1893–1895. doi: 10.1016/j.clinph.2012.02.066. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Topgaard D. Diffusion tensor distribution imaging. NMR Biomed. 2019;32:e4066. doi: 10.1002/nbm.4066. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kebapçı A, Dikeç G, Topçu S. Interobserver reliability of glasgow coma scale scores for intensive care unit patients. Crit Care Nurse. 2020;40:e18–e26. doi: 10.4037/ccn2020200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Zulfiqar AA, Thomasset de Longuemarre A. Codex and MMSE: what to choose? Geriatr Psychol Neuropsychiatr Vieil. 2019;17:279–289. doi: 10.1684/pnv.2019.0811. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Marceaux J, Bain K, Fullen C. C-33 abnormal MoCA scores in a clinic-referred sample. Arch Clin Neuropsych. 2019;34:1062. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Bernaola-Sagardui I. Validation of the barthel index in the spanish population. Enferm Clin (Engl Ed) 2018;28:210–211. doi: 10.1016/j.enfcli.2017.12.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Dulf D, Coman MA, Tadevosyan A, Chikhladze N, Cebanu S, Peek-Asa C. A 3-Country assessment of traumatic brain injury practices and capacity. World Neurosurg. 2021;146:e517–e526. doi: 10.1016/j.wneu.2020.10.115. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Nichols E, Vos T. The burden of dementia and dementia due to down syndrome, Parkinson’s disease, stroke, TBI, and HIV: an analysis for the Global Burden of Disease study 2019. Alzheimer’s Dementia. 2020:16. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Yokobori S, Yokota H. Targeted temperature management in traumatic brain injury. J Intensive Care. 2016;4:28. doi: 10.1186/s40560-016-0137-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Roozenbeek B, Maas AI, Menon DK. Changing patterns in the epidemiology of traumatic brain injury. Nat Rev Neurol. 2013;9:231–236. doi: 10.1038/nrneurol.2013.22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Oberholzer M, Müri RM. Neurorehabilitation of traumatic brain injury (TBI): a clinical review. Med Sci (Basel) 2019;7:47. doi: 10.3390/medsci7030047. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ignowski E, Winter AN, Duval N, Fleming H, Wallace T, Manning E, Koza L, Huber K, Serkova NJ, Linseman DA. The cysteine-rich whey protein supplement, Immunocal®, preserves brain glutathione and improves cognitive, motor, and histopathological indices of traumatic brain injury in a mouse model of controlled cortical impact. Free Radic Biol Med. 2018;124:328–341. doi: 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2018.06.026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Jullienne A, Obenaus A, Ichkova A, Savona-Baron C, Pearce WJ, Badaut J. Chronic cerebrovascular dysfunction after traumatic brain injury. J Neurosci Res. 2016;94:609–622. doi: 10.1002/jnr.23732. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Song H, Yuan S, Zhang Z, Zhang J, Zhang P, Cao J, Li H, Li X, Shen H, Wang Z, Chen G. Sodium/hydrogen exchanger 1 participates in early brain injury after subarachnoid hemorrhage both in vivo and in vitro via promoting neuronal apoptosis. Cell Transplant. 2019;28:985–1001. doi: 10.1177/0963689719834873. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Machii K, Cohen D, Ramos-Estebanez C, Pascual-Leone A. Safety of rTMS to non-motor cortical areas in healthy participants and patients. Clin Neurophysiol. 2006;117:455–471. doi: 10.1016/j.clinph.2005.10.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Zhang S, Dai W, Zhang R. Early intensive insulin therapy for type 2 diabetes in hippocampal NAA/Cr and Cho/Cr. Diabetes-Metab Res. 2015:18. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Dufor T, Grehl S, Tang AD, Doulazmi M, Traoré M, Debray N, Dubacq C, Deng ZD, Mariani J, Lohof AM, Sherrard RM. Neural circuit repair by low-intensity magnetic stimulation requires cellular magnetoreceptors and specific stimulation patterns. Sci Adv. 2019;5:eaav9847. doi: 10.1126/sciadv.aav9847. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Banerjee J, Sorrell ME, Celnik PA, Pelled G. Immediate effects of repetitive magnetic stimulation on single cortical pyramidal neurons. PLoS One. 2017;12:e0170528. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0170528. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Yu P, Wang Y, Yuan J, Chen J, Lei Y, Han Z, Liu D, Zhao Y, Wang P, Luo F. Observation for the effect of rTMS combined with magnetic stimulation at Neiguan (PC6) and Sanyinjiao (SP6) points on limb function after stroke: a study protocol. Medicine (Baltimore) 2020;99:e22207. doi: 10.1097/MD.0000000000022207. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]