Abstract

The U.S government has historically responded to human, natural and economic disruptions that threaten food insecurity by modifying federally-funded public food programs. The authors conducted a scoping review to identify and summarize available evidence on the efforts of a 20-year period to modify food benefit programs in response to emergencies; describe how food benefit programs interact to support vulnerable populations; identify key facilitators and barriers to effective implementation and impact; and assess relevance of evidence to COVID-19 pandemic. Scoping reviews address broad research questions aimed at mapping key concepts and available evidence in a defined area, and include academic and gray literature and reports from governments and NGOs. This review followed the PRISMA Extension for Scoping Reviews and included a three-stage search strategy. Studies were independently screened for eligibility by two researchers with multiple rounds of review. A content based charting method was used to summarize evidence. More than 2289 documents were identified and screened. After review, 44 documents were analyzed. Only 18% of documents reported program or policy impact data. Additionally, review of 149 policy records from State by State FNS Disaster Assistance Data from Oct 2016–Dec 2020 assessed 96 state specific food policy responses to 72 distinct events. Analysis revealed 53 distinct packages of food policy modifications used in response to crises. This scoping review demonstrates that few studies document the impact on food insecurity of food benefit modifications in response to crises. Most documents present output level details about costs and total number of individuals served. Many documents describe food policy response to crises without providing evaluation of response. Analysis points to SNAP and Child Nutrition Programs as most commonly modified food benefit programs in the wake of U.S. crises. The review concludes with a number of considerations for continued response to the ongoing COVID-19 crisis.

Keywords: Scoping review, Food policy, Emergency response, SNAP, COVID-19

Highlights

-

•

Few studies document food security impact of food benefit modifications in response to crises.

-

•

Instead, most studies document food policy modifications, their economic costs, and reach.

-

•

SNAP and Child Nutrition Programs are most commonly modified food benefits in wake of U.S. crises.

-

•

Large scale complex crisis that threaten food security require multipronged food policy response.

-

•

There is more the federal government can do to limit COVID-19's impact on food insecurity and hunger.

1. Introduction

1.1. Rationale

Food insecurity has been recognized as a persistent problem in the US at least since the 1980s, and the COVID-19 epidemic and its economic consequences have pushed millions of additional children and young people in the U.S. into food insecurity, jeopardizing their well-being and health now and in the future. Recent research suggests that as many as 50.4 million Americans (15.6%) will be food insecure in 2020, with 17 million of them children (23.1% of the U.S. child population) (Feeding America (2021) Th, 2021). Strong evidence documents the long term adverse physical health, mental health, and social consequences of food insecurity in the first 2 decades of life (American Psychological As, 2012; Drennen et al., 2019; Food Research & Action Ce, 2017). Thus, new federal, state, and city resources allocated to reducing food insecurity resulting from the COVID-19 epidemic and its economic consequences provide an opportunity for the United States to test innovative approaches to food policy and learn how the nation can make progress towards the elusive goal of creating and enacting the public policies necessary to end food insecurity and hunger among U.S. children.

Local, state, and national governments in the United States have long worked in tandem to modify federally-funded public food programs such as the Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program (SNAP), Special Supplemental Program for Women, Infants, and Children (WIC), and Child Nutrition Programs in response to human, natural and economic disruptions, including in response to COVID-19. They have changed eligibility criteria, increased funding for benefits, expanded outreach and education, facilitated enrollment and re-certification, and applied new technologies such as Electronic Benefit Transfer (EBT) and online enrollment for SNAP and WIC.

A related set of innovations in both food assistance and health care have tested new approaches to reaching vulnerable but often excluded populations such as children living in poverty, recent immigrants, and the families of the newly unemployed. These innovations, which also seek to promote local economic development, have taken place at the federal, state, and local levels and often involve complex interactions among the different levels of government to assure effective implementation, monitoring and funding of these initiatives. Although a robust body of evidence on these initiatives exists, they have not been systematically summarized and assessed for their relevance to the current pandemic, nor organized to be useful for policymakers and advocates.

This study employs a scoping review methodology to integrate established evidence-based practices with “practice-based evidence” (Ammerman et al., 2014) on the varying circumstances of past emergencies that have threatened food security and the food policies and programs implemented in response. This is an understudied topic, the authors were unable to find similar studies with a specific focus on US food policy response to domestic crises. This study takes a broad and exploratory scope and maps key concepts and gaps in evidence related to this particular niche of food policy. By systematically searching, selecting, and synthesizing data from academic and gray literature, public policy reports, and news media accounts of implementation and impact, among others, this study aims to advance food policy response to the COVID-19 pandemic by presenting a rigorous policy-relevant analysis of the evidence of the effects of expanding public benefits in response to emergencies that threatened to increase food insecurity in hunger during the period 2000 to 2020.

Table 1 provides a comprehensive list of all acronyms throughout this text.

Table 1.

List of acronyms used in text.

| Acronym | Meaning |

|---|---|

| $USD | U.S. Dollars |

| ABAWD | Able Bodied Adults Without Dependents |

| ARRA | American Recovery and Reinvestment Act of 2009 |

| BBCE | Broad-based categorical eligibility |

| CACFP | Child and Adult Care Food Program |

| COVID-19 | Severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2/novel coronavirus disease 2019 |

| D-SNAP | Disaster Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program |

| EBT | Electronic Benefit Transfer |

| FNS | USDA Food and Nutrition Service |

| NAP | Nutrition Assistance Program |

| NSLP | National School Lunch Program |

| P-EBT | Pandemic Electronic Benefit Transfer |

| SBP | School Breakfast Program |

| SFSP | Summer Food Service Program |

| SNAP | Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program |

| SSO | Seamless Summer Option |

| TANF | Temporary Assistance for Needy Families |

| USDA | United States Department of Agriculture |

| WIC | Special Supplemental Nutrition Program for Women, Infants, and Children |

2. Study objectives

This synthesis provides timely and relevant evidence to policy makers and food policy advocates poised to support COVID-19 related emergency programs to reduce food insecurity in children and youth. Specifically, the objectives of this review are to:

-

1)

Identify and summarize available academic and gray literature and reports from government and non-profit organizations on the efforts over a 20-year period to modify food benefit programs such as SNAP, WIC, Child Nutrition Programs, and Nutrition Incentive Programs, in responses to emergencies that have threatened to increase food insecurity and hunger.

-

2)

Describe the ways in which food benefit programs interact, work in tandem, and can add maximum value to support vulnerable populations during natural disasters, emergencies, and public health and economic crises.

-

3)

Identify key facilitators and obstacles to effective implementation and impact of these programs and their distinct characteristics across federal, state, and local levels.

-

4)

Assess the relevance of this evidence to the current period of the COVID-19 pandemic and the economic upheaval it has triggered to assess the extent to which this evidence can contribute to achieving food policy goals for the COVID-19 era and beyond.

3. Methods

The methods for this study follow, to the extent possible, PRISMA-ScR Reporting Guidelines for scoping reviews suggested by Tricco et al. (Tricco et al., 2018a)

3.1. Eligibility criteria

A succinct set of inclusion and exclusion criteria was developed in an effort to identify and summarize all aspects of the wide, complex, and heterogenous body of literature relevant to this study. Records were included in the final study only if all inclusion criteria were met. Table 2 details inclusion and exclusion criteria for the scoping review.

Table 2.

Scoping review study inclusion and exclusion criteria.

| The following types of sources were included: |

|---|

|

| Literature sources were excluded if they: |

|

The focus of this scoping review includes documentation of evidence for the period between 2000 and 2020. Technology plays a significant role in current methods for applying to, recertifying, and accessing food benefit programs. Further, food benefit programs have been updated in scope and design throughout their history. Excluding documents released earlier than 2000 allowed the authors to focus on insights most relevant to the current structure and operational modalities of these programs and to maximize learning most relevant to the COVID-19 crisis.

3.2. Information sources and search

A number of academic and public information sources were systematically searched. A brief description of each source is provided in Table 3.

Table 3.

Information sources for scoping review.

| Academic literature: |

|---|

|

| Gray Literature: |

|

| Broad search for other documents and media: |

|

Consultation with the (removed for double blinding) Librarian informed the overall search strategy for this project, including the targeting of specific databases within the (removed for double blinding) Library system, as well as for accessing gray literature through public channels. A multi-step search strategy was utilized, incorporating each of the described sources.

The first step was an initial limited search of Google Scholar, followed by an analysis of the text words contained in the title and abstract of retrieved papers and of the index terms used to describe them. This analysis resulted in a list of search terms, which were then reviewed by the research team and the (removed for double blinding) Librarian to maximize search returns using appropriate search language and coding. Then, a second more systematic search using identified keywords and index terms was undertaken across JSTOR, OneSearch, GreyLit.org, and Google (to capture news and media documents). The full electronic systematic search strategy for this stage is presented in Table 4. The USDA Food and Nutrition Service web site was reviewed for relevant links and research documents, and these were bookmarked for close reading. Finally, the reference list of reports and articles identified for inclusion in the review was searched for additional studies that had not yet been identified. Documents discovered via multiple searches were included only upon the primary search and disregarded thereafter.

Table 4.

Full electronic search strategy, including search terms and limits.

| Terms: |

|

| Limits for each search: |

|

| Additional limits any searches using the term “emergency response”: |

|

3.3. Selection of sources of evidence and data charting process

All documents for inclusion were reviewed by at least two reviewers. Documents were screened first by title and abstract. If documents included relevant themes in title and abstract, both reviewers then independently reviewed the full text. Disagreements were resolved in discussion with a third, senior researcher, who listened to arguments for or against inclusion by each reviewer and made a final decision. Evidence was selected according to the inclusion and exclusion criteria.

Sources were charted by a single researcher using Airtable (https://airtable.com), an electronic cloud based, hybrid spreadsheet-database software. Within each resource, data were extracted according to the following details: author information, title, source, year of publication, relevant event, food policy response, and implementation modifications. Where available, researchers also collected evidence about policy impact and challenges/barriers to successful implementation. In addition to the charting process, researchers documented evidence related to study objectives, identified key text and synthesized findings under cross cutting themes in response to the study's guiding questions. Specifically, researchers categorized modifications to food benefit based on intended policy impact, documented the extent to which reports detailed evidence of human level policy impact (e.g. improvements in food security or food access and reduction in hunger), examples of interaction between food benefit and safety net programs during periods of crisis, key facilitators and obstacles to effective policy and program implementation, and utility of lessons learned from past crises in application to the current public health and economic crisis triggered by the COVID-19 pandemic. Key facilitators and barriers to implementation were charted if the original documents explicitly referred to them in this way.

Once a first pass at charting was complete, researchers used Airtable functionality to review the sources filtering by crisis/event and then filtering by program response and finally filtering by impact. Using multiple stages of filtering the data in this way allowed the authors to check for gaps in documentation of evidence or gaps in coding, first on a record by record and then on a holistic basis. Once these gaps were identified, authors then ran additional focused searches of the databases described using new search terms (included in Table 4 full search terms list) the products of which were then added into the data chart and included in the study.

State by State Disaster Assistance Data was not included in this charting process, because of its format, but instead analyzed separately in Airtable. Researchers calculated descriptive statistics this data set, which is provided in section 4.0.

4. Results

4.1. Selection of sources of evidence

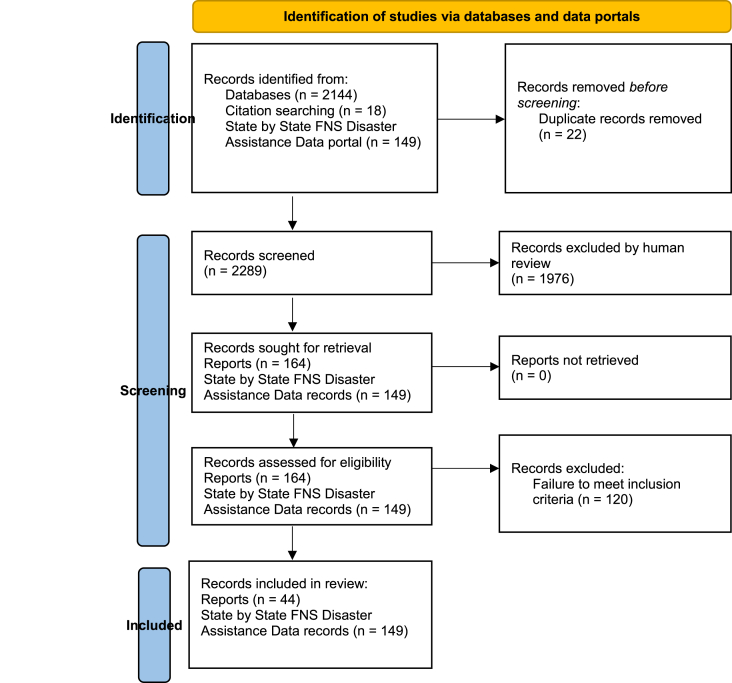

More than 2289 records were identified using the databases and search terms described. Each of these was screened using an abstract and title review, resulting in 164 documents. Full text review resulted in the exclusion of 120 additional documents, leaving 44 total documents for inclusion in this review (Fig. 1.)

Fig. 1.

Flow diagram for the scoping review process adapted from PRISMA-ScR guidelines (Tricco et al., 2018b).

Additionally, the USDA Food and Nutrition Service (FNS) web site features detailed State by State FNS Disaster Assistance data, with individual state entries dating back as far as October 2016 (Food and Nutrition S, 2021a). Review of State by State FNS Disaster Assistance Data from October 2016–December 2020 (time limited due to available data on USDA website, data prior to 2016 not available at time of search) assessed 149 records detailing 96 state/territory specific food policy responses to 72 distinct “disaster” or crisis events.

4.2. Summary of individual sources of evidence

4.2.1. Evidence in the literature documenting specific crises and associated food policy response

A brief summary of each included document is provided in Appendix A.

Of the 44 original documents charted for this review, more than half (n = 23) referred to modifications to SNAP and nearly as many (n = 21) referred to disaster specific implementation of the Disaster Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program (D-SNAP) and USDA Commodity Food Disaster Distribution programs. A smaller number of sources referred to modifications to Child Nutrition Programs such as National School Lunch Program (NSLP), School Breakfast Program (SBP), and Child and Adult Care Food Program (CACFP) (n = 7) and WIC (n = 5.) Documents referring to other programs such as nutrition incentive efforts (i.e. Double Up Food Bucks) and other relief programs such as Temporary Assistance for Needy Families (TANF) and Nutrition Assistance Program (NAP) for U.S. Territories were mentioned infrequently. Notably, only a handful of documents (n = 8) reported program or policy output or outcome level impact data.

Charted documentation of all sources of evidence detailing specific crises and associated food policy response is provided in Appendix B.

4.2.2. Policy packages: state by state FNS Disaster Assistance Data (october 2016–December 2020)

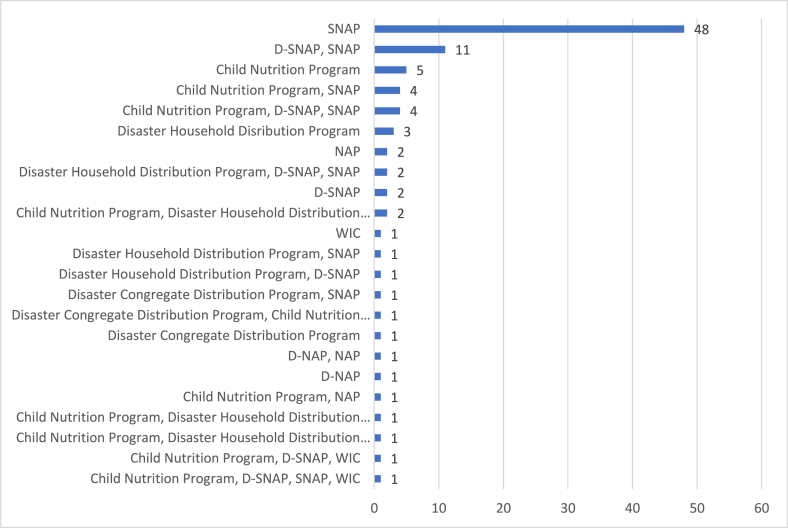

Among the 149 records detailing 96 state/territory responses detailed in FNS 2016–2020 State by State data, the authors identified 23 different examples of the ways in which policy makers employ distinct activation of various food assistance programs. Some examples operate individually while others work in tandem to promote food security and prevent hunger among affected populations. Among these, the most commonly implemented disaster assistance response was modification of SNAP as a stand-alone program followed by modifications of SNAP and D-SNAP together, modifications of Child Nutrition Programs as a stand-alone response, modifications to SNAP and Child Nutrition Programs together, with modifications to SNAP, D-SNAP, and Child Nutrition programs together rounding out the top five (Fig. 2).

Fig. 2.

Most frequently used “packages” of FNS disaster assistance programs between 2016 and 2020 (Food and Nutrition S, 2021b).

A closer look at the specific modifications implemented within each program revealed 53 distinct packages of food policy modifications. The most commonly utilized modifications to food programs were quantified, with the most often implemented being:

-

1.

SNAP waivers for timely reporting of individual requests for replacement of lost food due to disaster;

-

2.

SNAP automatic replacement of benefits due to lost food for individuals residing in disaster affected areas;

-

3.

D-SNAP implementation;

-

4.

Child Nutrition Programs waivers of meal pattern requirements for NSLP/SBP and SSO and SFSP;

-

5.

SNAP waivers to enable purchase of hot food with EBT benefits.

The authors noted that a limited number of documents (n = 11) provided data on reach and total $USD spend of food policy response while many others provided incomplete evidence. For example, documentation of food policy response to Hurricane Harvey (Texas, 2017) included 6 programmatic elements (D-SNAP, SNAP automatic supplements, SNAP mass replacement, SNAP waiver for hot food, SNAP waiver for timely reporting, and SNAP certification extension) (Food and Nutrition S, 2021b) but data on total $USD spend and total number of individuals reached is only available for 3 of the 6 programs included in the overall response (Texas Department of Healt, 2017). In another example of incomplete data of this kind, documentation of Hurricanes Katrina and Rita (2005) details $USD spend for most programs, but does not account for number of individuals reached by any program (Congressional Research Se, 2006). The authors thus determined that it was not possible to draw conclusions for the purposes of this study and decided that this line of investigation was outside the scope of this review, another illustration of the limited evidence on the impact of efforts to modify food benefit programs in response to crises.

4.2.3. Key facilitators and obstacles to implementation

Documents were coded to identify facilitators and obstacles to program implementation. A list of codes generated for each category is provided in Table 5.

Table 5.

Limiting and supporting factors in food benefit program implementation crisis response.

| Facilitators | Obstacles |

|---|---|

| Federal support for administrative costs | Increased administrative costs at expanded scale |

| Insufficient State budget to accommodate increased cost of scale of benefit programs | |

| “Single stop” model allowing individuals to register for multiple assistance programs at once | Insufficient in-person registration sites |

| Expedited application interview processes | Time required when implementation requires the creation of new channels for benefit distribution |

| Categorical eligibility | |

| Use of existing benefit distribution channels for crisis specific benefits or benefit increases (e.g. use of EBT systems) | |

| Coordination across city and state agencies | Lack of coordination and state by state differences in implementation policies |

| Appointment of a disaster response coordinator or crisis czar | |

| Direct prioritization of food security | During geographically centered crisis (e.g. hurricanes, wildfires, terrorist attacks) food benefit programs may become “lost in the shuffle” of economically focused policies such as those that address housing and job displacement |

4.3. Synthesis of results: determining impact of food benefit programs

Based on comprehensive analysis of all resources included in this scoping review, the authors categorized modifications to food benefit programs in response to crises into distinct groups based on intended impact of these modifications in Table 6.

Table 6.

Categories of modifications to food benefit programs.

| Intended Impact | Examples of Modifications |

|---|---|

| Increase eligibility and enrollment | Waivers of SNAP work requirements and asset limits, categorical eligibility for SNAP, categorical eligibility for Child Nutrition Programs |

| Increase benefits for participants | Increasing SNAP benefit amount per enrolled household, providing full reimbursement for all Child Nutrition Program meals at the “free” rate |

| Decrease administrative burden on administering agency and clients | Extension on re-certification periods, waivers for SNAP periodic reporting requirements, extension of claim periods, activation of SSO and SFSP options during periods which NSLP normally runs |

| Facilitate access to food | SNAP waivers that allow hot food purchase, SNAP waivers on timely reporting of food loss, waivers on Child Nutrition Program meal pattern requirements, early issuance for SNAP clients in anticipation of weather crisis, SNAP automatic supplement |

From the limited human level impact data available on food policy response to past crises, a few key lessons are discernible:

-

•

High levels of engagement in food benefit programs among eligible populations during periods of non-crisis can be protective during periods of active crisis and its aftermath. Findings from one study compare the impact of varying degrees of state level SNAP participation prior to the 2008 Recession on Recession era program participation. In a case study of Oregon, which had high levels of SNAP participation among eligible residents prior to the crisis, SNAP participants had longer period of participation and a reduced likelihood of losing benefits due to administrative issues during and after the recession compared to states (such as Florida) which had low levels of pre-Recession program participation (Edwards et al., 1080).

-

•

Increasing maximum SNAP benefit to households can increase program participation, increase household resource for food purchases, and decrease food insecurity among very low-income households. Recession era modifications increased the maximum SNAP benefit for households by 13.6%, which further increased incentive to enroll in the program, resulting in a 3% increase in program participation by low income households. SNAP benefits received by the typical (median) participating household increased by 16%, thus increasing household resource for food purchases by 5.4% (Economic Research Se, 2011a) resulting in reductions in food insecurity (Center on Budget and Poli, 2015a). Food insecurity was expected to rise in 2008–2009 as a result of the Recession, but instead it fell during that period among very low food secure households by 2%, a result largely attributed to the benefit increase and increased enrollment in the program (Center on Budget and Poli, 2015b; Economic Research Se, 2011b).

-

•

Broad-Based Categorical Eligibility (BBCE) for SNAP at the state level can increase the pool of eligible households and promote program enrollment during economic downturn. USDA encouraged state adoption of Broad-Based Categorical Eligibility for SNAP enrollment during the Great Recession and by 2011 37 states had adopted it, leading to increased SNAP eligibility and enrollment by 1.0 million individuals (Center on Budget and Poli, 2015c; Ganong & Liebman, 2013a, 2013b).

-

•

SNAP waivers for Able Bodied Adults Without Dependents (ABAWD) are an effective mechanism for increasing program enrollment by expanding the eligible pool of applicants and providing a greater incentive for households to apply. SNAP waivers on time limits for work requirements for ABAWD during the Great Recession expanded the eligible pool of SNAP applicants and provided a greater incentive for people to apply given longer duration of benefit receipt. It is estimated that this waiver increased SNAP enrollment by 1.9 million individuals (Ganong & Liebman, 2013a, 2013b).

-

•

Policy modifications such as the SNAP Expanded Disaster Evacuee Policy and flexibilities to the Child Nutrition Program that enable multiple school districts to operate out of the same location but claim meals separately are effective mechanisms for serving misplaced individuals immediately after a crisis. These modifications adeptly address immediate need for food and help to lower administrative burden for clients during times of crisis (Department of Agricu, 2017; Food and Nutrition S, 2005; Food Research & Action Ce, 2018).

5. Discussion

5.1. Limitations of available evidence on impact of food program modifications in response to crises

Of the documents captured for this scoping review, few sources report evaluation findings or on the overall impact of efforts to modify food programs in response to emergencies. Impact might be described as the impact of the program on limiting or alleviating food insecurity and hunger, or on improving food access, among affected populations during periods of crisis. Literature documenting impact of food policy response to major crises appears to be limited to two major events of the last 20 years: The Great Recession and Hurricane Katrina. The paucity of human level impact data referring to improvements in food insecurity, reductions in hunger, or improvement in food access is problematic on multiple levels. First, a lack of impact data means that policy makers looking to learn from prior implementations of policy response must rely on the limited data on program reach and $USD benefits distribution to determine whether program modifications were effective. While it is helpful to understand how many people were served by a given policy response, and the dollar amount of benefits distributed, these metrics do not convey the impact of these benefits on individual food security and hunger in the short or long term, and they do not offer a framework for understanding how individuals would have fared if given policies had not been implemented in the first place. Second, a lack of impact data ultimately leaves legislators with less decision-making power, forcing them to rely on previous patterns of policy implementation to inform future policy response – to rely on doing things a certain way because that is the way they have always been done, rather than learning from past successes and where programs have fallen short of meeting the needs of Americans during crises.

An initial intention of this study was to evaluate the effectiveness of past food policy response to crises, and to compare the degree to which these programs were impactful at alleviating hunger and food insecurity. However, this aim was not achieved due to limitations in available data. The question of impact remains an open one and limits the extent to which this evidence can contribute to achieving food policy goals for the COVID-19 era. The recommendations presented in this study are grounded in available evidence, but the authors would have liked to make more of them if the literature had supported it.

In seeking to contextualize our findings among a broader literature about domestic food policy response to crises, the authors did not find similar studies to which they could compare or contrast their findings. A lack of contextual data for this study limits the way in which its conclusions can be positioned in a broader narrative regarding food policy response to crises. Conversely, this study fills a notable gap in the literature, and provides a basis for future studies of this kind.

Finally, inclusion criteria for this study excluded documents published prior to 2000. Though the authors believe this limitation is justified because it supports timely and relevant policy recommendations for the COVID-19 era, it is possible that broadening this scope may have revealed additional documents that could contribute to this study's conclusions.

5.2. Interactions among food benefit programs maximize support to vulnerable populations

From the limited documentation of impact of food benefit programs in response to crises, the authors conclude that achieving measurable impact of these programs requires a multi-pronged food policy response that both enhances the utility (e.g. increasing benefit amounts) and reach (e.g. expanding the pool of eligible individuals) of standing safety net programs while also activating additional emergency specific programs to ensure that both long term and short-term food needs are addressed. Significant impact in alleviating hunger and food insecurity during a crisis is achieved when the policies activated address food issues as well as economic stimulus and recovery. SNAP, for example, creates an economic stimulus of $1.50 for every $1.00 of food benefits spent during a weak economy (Economic Research Se, 2019). Because of the way in which food access and long-term food security is inextricably linked to an individual's stable conditions such as housing and income, food policy responses that also promote economic stimulus are particularly salient (Economic Research Se, 2011c).

Among the most frequently activated programs, SNAP, Child Nutrition Programming, and D-SNAP top the list of policies activated in stand-alone response or in tandem. Our analysis and the data presented in Fig. 2 indicate that policy makers perceive these programs or combination of programs to be the most likely to have an efficient and beneficial response for their constituencies. Given that SNAP and Child Nutrition Programs are well-established in most States, with active distribution channels and high participation, activating these programs makes use of these built in facilitators and eases increased operational burden for state and local benefits administrators and agencies.

5.3. Facilitators to effective implementation of food policy response to crises

Specific food program modifications have historically aided scaling and helped to streamline operations of these programs during periods of crisis. Table 6 categorizes modifications according to their intended impact. This review of past food policy response indicates that a multi-pronged approach that pulls from various categories of modification type, and which both amplifies benefits for current participants while also expanding the eligible pool of individuals, may be important for promoting total response effectiveness. The authors note that the response to less widespread crises tends to rely on a single type of modification to a single program (i.e., SNAP waivers for timely reporting of individual requests for replacement of lost food due to disaster), but that modifications that increase benefit amounts or decrease administrative burden are used in tandem less frequently. Based on evidence of impact from large crises such as Hurricane Katrina and the Great Recession in which modifications that increase benefit amounts or decrease administrative burden have been shown to be effective at increasing program impact, the authors recommend that policymakers more often activate responses that utilize numerous categories of food policy response to crises in order to increase effectiveness of overall food policy response.

5.4. Challenges in implementing food policy response to crises

Detailed accounts of the challenges to implementing food policy in response to crises is also limited to documentation of a handful of well-recognized major events such as the September 11, 2001 Terrorist Attacks, the Great Recession, and Hurricane Katrina. Challenges cited in implementing food policy response during these crises lend themselves to a number of lessons applicable for future response:

-

•

Administrative costs should be covered in full by federal support in order to maximize state level implementation and program effectiveness. Though ARRA included nearly $300 million over two years to support states in meeting administrative demands related to increased caseloads of food benefit programs, several states were required to cut back on staff (rather than scale up to meet demand) due to budget constraints (PolicyLab and The Children's, 2010). Likewise, state level response to Hurricane Katrina was hobbled by the standard SNAP requirement that states cover 50% of administrative costs (Congressional Research Se, 2005a). Both instances illustrate how limited administrative budget restrictions can hinder program impact.

-

•

Effective food policy response requires direct and assertive prioritization of food related outcomes. Reports documenting the September 11 policy response largely describe measures to addressing housing and job displacement, and a key challenge cited for September 11 food policy response is the multi-pronged nature of the September 11 disaster; food security was an issue, but policy makers did not make reducing it a priority (Issuelab, 2003).

-

•

State level implementation of federal food policy response to multi-state crisis mean that households impacted to the same degree in different states might receive different levels of support. As such, equity issues were raised following analysis of multi-state response to Hurricane Katrina. As many as 15 years later, the model for state level implementation persists, with little conversation on how to ensure equitable response across state lines (Congressional Research Se, 2005b).

6. Conclusions

Evidence identified and summarized in this scoping review is relevant to the current period of the COVID-19 pandemic and the economic upheaval it has triggered, which threatens food security for millions of America's children and young people. USDA FNS has responded to the COVID-19 pandemic with extensive modifications and waivers to SNAP, Child Nutrition Programs, WIC, and USDA Commodity Foods Distribution programs. While some child focused waivers are new, with no precedent, such as P-EBT and expansion of SNAP online purchasing to support social distances, many in use are consistent with the pattern of flexibility adoption observed in response to previous crises of the last 20 years.

The authors found no evidence of similar studies with a specific focus on what can be learned from past domestic food policy response to crises in the US. Among the past crises and associated food policy response captured in this scoping review, the Great Recession and food policy response present within the American Recovery and Reinvestment Act may the most applicable to the present pandemic given the national scope and protracted nature of the crisis. Notable learnings from food policy response to the Great Recession indicate that there may be further steps the federal government can take in its COVID-19 response to minimize the pandemic's impact on national rates of food insecurity and hunger. Among these, the absorption of food benefit program full administrative costs to facilitate state agency implementation is paramount. Further, as states have a high level of decision-making power in flexibilities for food benefit programs, federal guidance to states should emphasize and encourage approaches that maximize equity for vulnerable populations at risk for hunger and food insecurity residing in different geographies. Finally, given that evidence from this review suggests that significant impact in alleviating hunger and food insecurity during a crisis is achieved when the policies activated in combination address food issues as well as economic stimulus and recovery, policy makers should continue to bolster and expand SNAP, WIC, and P-EBT programs that both provide food and address the economic distress many Americans continue to experience.

A key question as the pandemic persists is the impact on national experiences of hunger and food insecurity resulting from the protracted economic impact, and the way that these deficiencies will persist even when the public health crisis is over and the economy is on the mend. The extensive flexibilities applied to food benefit programs during COVID-19 highlight the bureaucratic complexities involved in typical operation of safety net programs, and the number of individuals who very nearly qualify for these programs but are excluded from receipt of benefits by asset limits, work requirements, and other means tests. The current growing crisis in food insecurity exacerbates pre-existing inequities and highlights long-standing problems in the nation's food system (Bleich and Willett, 2020; Chan and Taylor, 2020; Perry et al., 2021). A key question looking forward is what flexibilities could be extended indefinitely (for example, permanent increases to SNAP benefit amounts, permanent expansion of college student eligibility for SNAP, or permanent establishment of a national school lunch program that provides free school meals for all), becoming permanent fixtures of food benefit programs, to help widen the social safety net and promote a higher standard of food security among vulnerable populations.

Author statement

Katherine Tomaino Fraser: Project administration, Investigation, Data curation, Visualization, Formal analysis, Writing - Original Draft. Sarah Shapiro: Investigation, Data curation, Visualization. Craig Willingham: Project administration. Emilio Tavarez: Resources, Writing - Review and Editing. Joel Berg: Conceptualization, Writing - Review and Editing, Funding acquisition. Nicholas Freudenberg: Conceptualization, Methodology, Writing - Review and Editing, Supervision, Funding acquisition.

Declaration of competing interest

None.

Acknowledgements

This review was funded in partnership by the WT Grant Foundation and the Spencer Foundation. The funders had no involvement in the conduct of the research or the preparation of the article for publication.

The authors acknowledge the contributions of a number of CUNY based research assistants: Morgan Ames, Yvette Ng, Ivonne Quiroz, Kit Sathong, Emma Lingshan Sun, and the CUNY SPH Librarian Emily Pagano.

References

- American Psychological Association Household food insecurities: Threats to children's well-being. 2012. https://www.apa.org/pi/ses/resources/indicator/2012/06/household-food-insecurities Retrieved from. Accessed.

- Ammerman A., Smith T.W., Calancie L. Practice-based evidence in public health: Improving reach, relevance, and results. Annual Review of Public Health. 2014;35:47–63. doi: 10.1146/annurev-publhealth-032013-182458. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bleich S and Willett W. Food Insecurity, Inequality and COVID-19. Harvard T.H. Chan School of Public Health. Presented jointly with The World from PRX & WGBH on June 30, 2020. Retrieved from: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=E_w54kZ0MC4. Accessed September 24, 2021..

- Center on Budget and Policy Priorities SNAP benefit boost in 2009 recovery act provided economic stimulus and reduced hardship. 2015. https://www.cbpp.org/research/food-assistance/snap-benefit-boost-in-2009-recovery-act-provided-economic-stimulus-and Retrieved from. Accessed.

- Center on Budget and Policy Priorities SNAP benefit boost in 2009 recovery act provided economic stimulus and reduced hardship. 2015. https://www.cbpp.org/research/food-assistance/snap-benefit-boost-in-2009-recovery-act-provided-economic-stimulus-and Retrieved from. Accessed.

- Center on Budget and Policy Priorities SNAP benefit boost in 2009 recovery act provided economic stimulus and reduced hardship. 2015. https://www.cbpp.org/research/food-assistance/snap-benefit-boost-in-2009-recovery-act-provided-economic-stimulus-and Retrieved from. Accessed.

- Chan O and Taylor J. COVID-19 Lays Bare Vulnerabilities in U.S. Food Security. April 20, 2020. The Century Foundation. Retrieved from: https://tcf.org/content/commentary/covid-19-lays-bare-vulnerabilities-u-s-food-security/?agreed=1. Accessed on September 24, 2021..

- Congressional Research Service CRS report for Congress federal food assistance in disasters: Hurricanes Katrina and Rita. 2005. https://www.everycrsreport.com/files/20050923_RL33102_5ef201adf6e231aeee3ef25840f313d56549be0c.pdf Retrieved from. Accessed.

- Congressional Research Service CRS report for Congress federal food assistance in disasters: Hurricanes Katrina and Rita. 2005. https://www.everycrsreport.com/files/20050923_RL33102_5ef201adf6e231aeee3ef25840f313d56549be0c.pdf Retrieved from. Accessed.

- Congressional Research Service CRS report for congress: Federal food assistance in disasters: Hurricanes Katrina and Rita. 2006. https://nationalaglawcenter.org/wp-content/uploads/assets/crs/RL33102.pdf Retrieved from. Accessed.

- Drennen C.R., et al. Food insecurity, health, and development in children under age four years. Pediatrics. 2019;144(4) doi: 10.1542/peds.2019-0824. Article e20190824. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Edwards M., Heflin C., Mueser P., Porter S., and Weber B. The Great Recession and SNAP caseloads: A tale of two states. Journal of Poverty, 20, 261-277. 10.1080/10875549.2015.1094770. [DOI]

- Feeding America The impact of coronavirus on food insecurity. 2021. https://www.feedingamerica.org/research/coronavirus-hunger-research Retrieved from. Accessed.

- Food Research & Action Center The impact of poverty, food insecurity, and poor nutrition on health and well being. 2017. https://frac.org/wp-content/uploads/hunger-health-impact-poverty-food-insecurity-health-well-being.pdf Retrieved from. Accessed.

- Food Research & Action Center An advocate's guide to the disaster supplemental nutrition assistance program (D-SNAP) 2018. https://frac.org/wp-content/uploads/d-snap-advocates-guide-1.pdf Retrieved from. Accessed.

- Ganong P., Liebman J.B. Explaining trends in SNAP enrollment. 2013. http://citeseerx.ist.psu.edu/viewdoc/download?doi=10.1.1.385.3700&rep=rep1&type=pdf Retrieved from. Accessed.

- Ganong P., Liebman J.B. Explaining trends in SNAP enrollment. 2013. http://citeseerx.ist.psu.edu/viewdoc/download?doi=10.1.1.385.3700&rep=rep1&type=pdf Retrieved from. Accessed.

- Issuelab Responding to the 9/11 terrorist attacks: Lessons from relief and recovery in New York City. 2003. https://www.issuelab.org/resources/7639/7639.pdf Retrieved from. Accessed.

- Perry B.L., Aronson B., Pescosolido B.A. Pandemic precarity: COVID-19 is exposing and exacerbating inequalities in the American Heartland. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2021;118(8) doi: 10.1073/pnas.2020685118. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- PolicyLab, The Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia The effect of the recession on child well-being. 2010. https://policylab.chop.edu/report/effect-recession-child-well-being Retrieved from. Accessed.

- Texas Department of Health and Human Services Hurricane Harvey disaster SNAP. 2017. https://www.hhs.texas.gov/sites/default/files/documents/laws-regulations/reports-presentations/senate-hhs-hearing-dsnap-presentation.pdf Retrieved from. Accessed.

- Tricco A.C., et al. PRISMA extension for scoping reviews (PRISMA-ScR): Checklist and explanation. Annals of Internal Medicine. 2018;169(7):467–473. doi: 10.7326/M18-0850. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tricco A.C., et al. PRISMA extension for scoping reviews (PRISMA-ScR): Checklist and explanation. Annals of Internal Medicine. 2018;169(7):467–473. doi: 10.7326/M18-0850. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- USDA Department of Agriculture An epic disaster required unprecedented response. 2017. https://www.usda.gov/media/blog/2012/05/16/epic-disaster-required-unprecedented-response Retrieved from. Accessed.

- USDA Economic Research Service Food security improved following the 2009 ARRA increase in SNAP benefits. 2011. https://www.ers.usda.gov/publications/pub-details/?pubid=44839 Retrieved from. Accessed.

- USDA Economic Research Service Food security improved following the 2009 ARRA increase in SNAP benefits. 2011. https://www.ers.usda.gov/publications/pub-details/?pubid=44839 Retrieved from. Accessed.

- USDA Economic Research Service Food security improved following the 2009 ARRA increase in SNAP benefits. 2011. https://www.ers.usda.gov/publications/pub-details/?pubid=44839 Retrieved from. Accessed.

- USDA Economic Research Service Quantifying the impact of SNAP benefits on the U.S. economy and jobs. 2019. https://www.ers.usda.gov/amber-waves/2019/july/quantifying-the-impact-of-snap-benefits-on-the-us-economy-and-jobs Retrieved from. Accessed.

- USDA Food and Nutrition Service Expanded disaster evacuee policy. 2005. https://www.fns.usda.gov/snap/dsnap/expanded-disaster-evacuee-policy Retrieved from. Accessed.

- USDA Food and Nutrition Service State by state FNS disaster assistance. 2021. https://www.fns.usda.gov/disaster/state-by-state Retrieved from. Accessed.

- USDA Food and Nutrition Service State by state FNS disaster assistance. 2021. https://www.fns.usda.gov/disaster/state-by-state Retrieved from. Accessed.