Purpura fulminans (PF) is a rare cause of septic shock characterized by the association of a sudden and extensive purpuric rash together with an acute circulatory failure [1] leading to high rates of intensive care unit (ICU) mortality [1, 2] and long-term sequelae [3]. Clinical presentation of patients with PF differs from that of patients with meningitis since PF patients are commonly admitted to the ICU for hemodynamic impairment exposing them to early death from refractory circulatory failure, as opposed to patients with meningitis who are usually admitted to the ICU for neurological impairment. Among adult patients, Neisseria meningitidis and Streptococcus pneumoniae are the most commonly involved microorganisms accounting for more than 80% of PF [1] and meningitis [4]. While clinical features and outcomes widely differ between adult patients with pneumococcal and meningococcal meningitis [4], it remains unclear whether pneumococcal (pPF) and meningococcal (mPF) PF exhibit different clinical phenotypes and outcomes, although pPF was previously shown to predominantly occur in asplenic patients [5] and carries a higher risk of limb amputation [1]. We therefore compared the clinical, biological presentations and outcome of adult patients with pPF and mPF.

We performed an ancillary analysis of a 17-year multicenter retrospective study conducted in 55 centers in France, which included all consecutive patients (≥ 18 years) admitted to the ICU for an infectious PF (2000–2016) [1]. Patients with non-microbiologically documented PF or a bacterial documentation other than Neisseria meningitidis and Streptococcus pneumoniae were excluded.

During the study period, 195 patients with mPF and 67 with pPF were included. As compared to patients with mPF, those with pPF were older and had higher ICU severity scores. Chronic alcoholism and asplenia were more frequent in pPF, while the proportion of patients without previous comorbid conditions was lower. The time elapsed between disease onset and ICU admission was longer and purpura was less often noticed before ICU admission in pPF than in mPF. pPF patients also had lower platelet counts, higher serum urea and creatinine levels, and more frequent bacteremia. pPF patients needed more frequent invasive mechanical ventilation support, renal replacement therapy, plasma and platelets transfusions and had higher durations of invasive mechanical ventilation and vasopressor support. ICU mortality and rate of limb amputation were higher in patients with pPF (Table 1).

Table 1.

Comparison between meningococcal (n = 195) and pneumococcal (n = 67) purpura fulminans

| Meningococcal purpura fulminans n = 195 | Pneumococcal purpura fulminans n = 67 | p value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Patient’s characteristics and ICU scores | |||

| Male gender | 97 (50) | 37 (55) | 0.527 |

| Age, years | 24 [19–45] | 49 [38–60] | < 0.001 |

| SAPS II | 50 [35–66] | 63 [58–72] | < 0.001 |

| SOFA | 11 [8–14] | 14 [11–15] | < 0.001 |

| Main comorbidities | |||

| Chronic alcoholism | 5 (2) | 9 (13) | 0.002 |

| Diabetes mellitus | 3 (2) | 4 (6) | 0.073 |

| Asplenia or hyposplenia | 3 (2) | 34 (51) | < 0.001 |

| Malignant hemopathy | 1 (1) | 2 (3) | 0.162 |

| Chronic respiratory disease | 18 (23) | 14 (28) | 0.625 |

| Immunocompromised status | 5 (3) | 4 (6) | 0.241 |

| No coexisting comorbid conditions | 164 (84) | 22 (33) | < 0.001 |

| Clinical features upon ICU admission | |||

| Days between disease onset and ICU admission, days | 4 [4–5] | 5 [4–6] | 0.003 |

| Headache | 99 (51) | 26 (39) | 0.121 |

| Myalgia | 48 (25) | 12 (18) | 0.338 |

| Digestive signs | 124 (64) | 41 (61) | 0.839 |

| Coma Glasgow score | 15 [13–15] | 15 [13–15] | 0.751 |

| Temperature, °C | 38.5 [37–40] | 38.5 [37–39] | 0.802 |

| Neck stiffness | 52 (27) | 6 (9) | 0.004 |

| Purpuric rash before ICU admission | 168 (86) | 38 (57) | < 0.001 |

| β-Lactam antibiotic therapy before ICU admission | 157 (81) | 46 (69) | 0.067 |

| β-Lactam antibiotic therapy at ICU admission | 195 (100) | 67 (100) | – |

| Biological data upon ICU admission | |||

| Leukocytes count, 103 mm−3 | 10,700 [4000–20,800] | 10,655 [2500–19,750] | 0.717 |

| Platelets count, 103 mm−3 | 61,000 [28,500–100,000] | 33,000 [19,000–49,500] | < 0.001 |

| C-reactive protein, g/L | 148 [90–247] | 179 [141–289] | 0.095 |

| Procalcitonin, ng/mL | 48 [14–100] | 102 [55–164] | 0.087 |

| Troponin, mg/L | 1 [0.10–12] | 0.25 [0.13–11] | 0.697 |

| Creatine kinase, IU/L | 300 [110–852] | 812 [365–3460] | 0.016 |

| Serum urea, mmol/L | 9 [7–11] | 13 [11–15] | < 0.001 |

| Serum creatinine, μmoL/L | 190 [136–250] | 240 [184–310] | < 0.001 |

| Prothrombin time, % | 33 [22–44] | 29 [15–38] | 0.227 |

| Factor V, % | 23 [10–49] | 21 [9–29] | 0.246 |

| Arterial lactate, mmol/L | 7.40 [5–11] | 8 [6–11] | 0.798 |

| Fibrinogen, g/L | 1.70 [0.6–3] | 1.16 [0.5–2] | 0.122 |

| Microbiological data at ICU admission | |||

| Bacteremia | 99 (51) | 56 (84 | < 0.001 |

| Lumbar puncture performed | 125 (64) | 29 (43) | 0.004 |

| Positive cerebro-spinal fluid culture | 72/125 (58) | 11/29 (38) | 0.080 |

| Outcome in the ICU | |||

| Lowest LVEF, % | 33 [20–45] | 30 [25–50] | 0.870 |

| Inotropic agent | 91 (64) | 35 (61) | 0.894 |

| Platelets transfusion | 57 (29) | 46 (69) | < 0.001 |

| Plasma transfusion | 67 (34) | 44 (66) | < 0.001 |

| Steroids for septic shock or meningitis | 116 (60) | 45 (67) | 0.333 |

| Activated protein C | 33 (17) | 9 (13) | 0.632 |

| Invasive mechanical ventilation | 152 (78) | 65 (97) | 0.001 |

| Duration of tracheal intubation, days | 4 [2–9] | 10 [3–28] | < 0.001 |

| Duration of vasopressors, days | 3 [2–5] | 5 [3–8] | < 0.001 |

| Renal replacement therapy | 69 (36) | 45 (67) | < 0.001 |

| Veno-arterial ECMO | 7 (4) | 6 (9) | 0.104 |

| Limb amputation | 19 (10) | 21 (31) | < 0.001 |

| Limb amputation among ICU survivors | 18/125 (14) | 19/32 (59) | < 0.001 |

| Death in ICU | 70 (36) | 35 (52) | 0.027 |

| Duration of ICU stay, days | 5 [2–11] | 14 [3–35] | < 0.001 |

| Duration of hospital stay, days | 12 [2–23] | 23 [3–78] | 0.003 |

Continuous variables are reported as median [Interquartile range] and compared between groups using the Student t-test. Categorical variables are reported as numbers (percentages) and compared using χ2 test. A p value < 0.05 was considered significant

ICU intensive care unit; IMV Invasive Mechanical Ventilation, ECMO Extracorporeal membrane oxygenation, LVEF Left ventricular ejection fraction, SAPSII Simplified Acute Physiology Score, SOFA Sequential Organ Failure Assessment

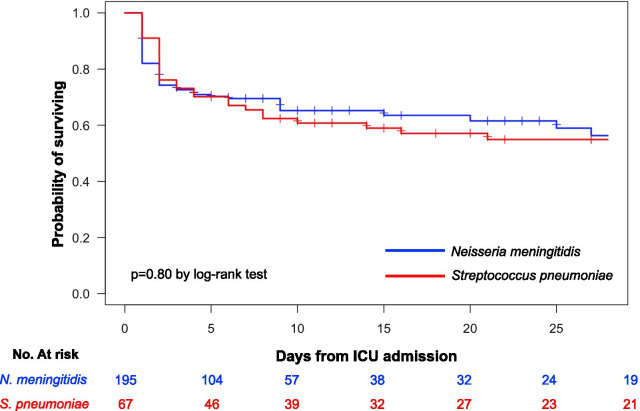

The Kaplan–Meier survival analysis did not show significant difference between pPF and mPF patients (p = 0.80 by the log-rank test, Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

Kaplan–Meier survival estimates during the 30 days following ICU admission of patients with pneumococcal (red curve) and meningococcal (blue curve) purpura fulminans

By multiple logistic regression adjusting on age, SOFA score, administration of β-lactam antibiotic therapy before ICU admission, platelet counts and arterial lactate levels, pPF was not associated with ICU mortality (adjusted Odds Ratio = 1.15 95% CI 0.45–2.89, p = 0.77).

As already reported in adults patients with bacterial meningitis [4], this study confirms that significant differences exist between mPF and pPF, regarding both the clinical presentation at ICU admission and outcomes. Patients with pPF showed a different clinical phenotype, with less frequent purpura possibly leading to less frequent antibiotic treatment, more comorbidities with a more severe presentation at ICU admission, resulting in a higher rate of organ failures during ICU stay. Whether this more severe presentation should be ascribed to the level of virulence of the causative pathogen or to host-related characteristics is unsettled.

Our study has several limitations including its retrospective design and its long recruitment period with a high number of centers implying ICU procedures being inevitably heterogeneous. Nevertheless, the clinical presentation as well as the course in the ICU of patients with PF seem to differ according to the causative bacterium. This clinical observation should encourage researchers to better study the pathophysiology of pPF in order to develop targeted innovative therapies as being done for mPF [6].

Acknowledgements

We thank the members of the HOPEFUL Study group (to be searchable through their individual PubMed records). Laurent Argaud (Lyon), François Barbier (Orléans), Amélie Bazire (Brest), Gaëtan Béduneau (Rouen), Frédéric Bellec (Montauban), Pascal Beuret (Roanne), Pascal Blanc (Pontoise), Cédric Bruel (Saint-Joseph), Christian Brun-Buisson (Mondor, AP-HP), Gwenhaël Colin (La Roche-sur-Yon), Delphine Colling (Roubaix), Alexandre Conia (Chartres), Rémi Coudroy (Poitiers), Martin Cour (Lyon), Damien Contou (Henri Mondor – AP-HP and Argenteuil), Fabrice Daviaud (Corbeil-Essonnes), Vincent Das (Montreuil), Jean Dellamonica (Nice), Nadège Demars (Antoine Beclère, AP-HP), Stephan Ehrmann (Tours), Arnaud Galbois (Quincy sous Sénart), Elodie Gelisse (Reims), Julien Grouille (Blois), Laurent Guérin (Ambroise Paré – AP-HP), Emmanuel Guérot (HEGP, AP-HP), Samir Jaber (Montpellier), Caroline Jannière (Créteil), Sébastien Jochmans (Melun), Mathieu Jozwiak (Kremlin Bicêtre, AP-HP), Pierre Kalfon (Chartres), Antoine Kimmoun (Nancy), Alexandre Lautrette (Clermont Ferrand), Jérémie Lemarié (Nancy), Charlène Le Moal (Le Mans), Christophe Lenclud (Mantes La Jolie), Nicolas Lerolle (Angers), Olivier Leroy (Tourcoing), Antoine Marchalot (Dieppe), Bruno Mégarbane (Lariboisière, AP-HP), Armand Mekontso Dessap (Mondor, AP-HP), Etienne de Montmollin (Saint-Denis), Frédéric Pène (Cochin, AP-HP), Claire Pichereau (Poissy), Gaëtan Plantefève (Argenteuil), Sébastien Préau (Lille), Gabriel Preda (Saint-Antoine, AP-HP), Nicolas de Prost (Henri Mondor, AP-HP), Jean-Pierre Quenot (Dijon), Sylvie Ricome (Aulnay-sous-Bois), Damien Roux (Louis Mourier, AP-HP), Bertrand Sauneuf (Cherbourg), Matthieu Schmidt (Pitié Salpétrière, AP-HP), Guillaume Schnell (Le Havre), Romain Sonneville (Bichat, AP-HP), Jean-Marc Tadié (Rennes), Yacine Tandjaoui (Avicenne, AP-HP), Martial Tchir (Villeneuve Saint Georges), Nicolas Terzi (Grenoble), Xavier Valette (Caen), Lara Zafrani (Saint-Louis, AP-HP), Benjamin Zuber (Versailles).

Abbreviations

- ICU

Intensive care unit

- mPF

Meningococcal purpura fulminans

- pPF

Pneumococcal purpura fulminans

- SOFA

Sequential Organ Failure Assessment

Authors' contributions

DC and NDP are responsible for the conception and design. All the authors were responsible for analysis and interpretation of data. All authors read, critically reviewed and approved the final manuscript. DC takes responsibility for the paper as a whole. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Funding

No funding.

Availability of data and materials

The dataset used and analyzed for the current study is available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

This study was conducted in accordance with the amended Declaration of Helsinki and was approved by the Institutional Review Board (CE 2016–01) of the French Intensive Care Society in March, 2016.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Contributor Information

Damien Contou, Email: damien.contou@ch-argenteuil.fr.

the HOPEFUL Study group, Email: damien.contou@gmail.com.

the HOPEFUL Study group:

Laurent Argaud, François Barbier, Amélie Bazire, Gaëtan Béduneau, Frédéric Bellec, Pascal Beuret, Pascal Blanc, Cédric Bruel, Christian Brun-Buisson, Gwenhaël Colin, Delphine Colling, Alexandre Conia, Rémi Coudroy, Martin Cour, Damien Contou, Fabrice Daviaud, Vincent Das, Jean Dellamonica, Nadège Demars, Stephan Ehrmann, Arnaud Galbois, Elodie Gelisse, Julien Grouille, Laurent Guérin, Emmanuel Guérot, Samir Jaber, Caroline Jannière, Sébastien Jochmans, Mathieu Jozwiak, Pierre Kalfon, Antoine Kimmoun, Alexandre Lautrette, Jérémie Lemarié, Charlène Le Moal, Christophe Lenclud, Nicolas Lerolle, Olivier Leroy, Antoine Marchalot, Bruno Mégarbane, Armand Mekontso Dessap, Etienne de Montmollin, Frédéric Pène, Claire Pichereau, Gaëtan Plantefève, Sébastien Préau, Gabriel Preda, Nicolas de Prost, Jean-Pierre Quenot, Sylvie Ricome, Damien Roux, Bertrand Sauneuf, Matthieu Schmidt, Guillaume Schnell, Romain Sonneville, Jean-Marc Tadié, Yacine Tandjaoui, Martial Tchir, Nicolas Terzi, Xavier Valette, Lara Zafrani, and Benjamin Zuber

References

- 1.Contou D, Sonneville R, Canoui-Poitrine F, Colin G, Coudroy R, Pène F, et al. Clinical spectrum and short-term outcome of adult patients with purpura fulminans: a French multicenter retrospective cohort study. Intensive Care Med. 2018;44:1502–1511. doi: 10.1007/s00134-018-5341-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Contou D, Mekontso Dessap A, de Prost N. Extracorporeal membrane oxygenation in adult patients with purpura fulminans. Crit Care Med. 2019;47:e1039–e1040. doi: 10.1097/CCM.0000000000003996. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Contou D, Canoui-Poitrine F, Coudroy R, Préau S, Cour M, Barbier F, et al. Long-term quality of life in adult patients surviving purpura fulminans: an exposed-unexposed multicenter cohort study. Clin Infect Dis. 2018;6:66. doi: 10.1093/cid/ciy901. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.van de Beek D, de Gans J, Spanjaard L, Weisfelt M, Reitsma JB, Vermeulen M. Clinical features and prognostic factors in adults with bacterial meningitis. N Engl J Med. 2004;351:1849–59. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa040845. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Contou D, Coudroy R, Colin G, Tadié J-M, Cour M, Sonneville R, et al. Pneumococcal purpura fulminans in asplenic or hyposplenic patients: a French multicenter exposed-unexposed retrospective cohort study. Crit Care. 2020;24:68. doi: 10.1186/s13054-020-2769-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Denis K, Le Bris M, Le Guennec L, Barnier J-P, Faure C, Gouge A, et al. Targeting Type IV pili as an antivirulence strategy against invasive meningococcal disease. Nat Microbiol. 2019;4:972–984. doi: 10.1038/s41564-019-0395-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

The dataset used and analyzed for the current study is available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.