Abstract

Background:

In a health insurance system based on managed competition, such as in the Netherlands, it is important that all citizens can make well-informed decisions on which policy fits their needs and preferences best. However, partly due to the large variety of health insurance policies, there are indications that a significant group of citizens do not make rational decisions when choosing a policy.

Objective:

This study aimed to provide more insight into (1) how important it is for citizens in the Netherlands to choose a health insurance policy and (2) how easy it is for them to comprehend the information they receive.

Methods:

Data were collected by sending a survey to members of the Nivel Dutch Health Care Consumer Panel in February 2017. The response rate was 44% (N = 659).

Key Results:

Our results indicate that citizens in the Netherlands acknowledge the importance of choosing a health insurance policy, but they also point out that it is difficult to comprehend health insurance information.

Conclusion:

Our findings suggest that a section of the citizens do not have the appropriate skills to decide which insurance policy best fits their needs and preferences. Having better insight into their level of health insurance literacy is an important step in the process of evaluating the extent to which citizens can fulfill their role in the health insurance system. Our results suggest that it is important to better tailor information on health insurances to the specific needs and skills of the individual. By doing this, citizens will be better supported in making well-informed decisions regarding health insurance policies, which should have a positive effect on the functioning of the Dutch health insurance system. [HLRP: Health Literacy Research and Practice. 2021;5(4):e287–e294.]

Plain Language Summary:

The number of health insurance policy options to choose from is extensive in the Netherlands. This study explored to what extent citizens in the Netherlands find it important to choose a health insurance policy, and to what extent they comprehend the information they receive. The data were collected in 2017 using the Nivel Dutch Health Care Consumer Panel.

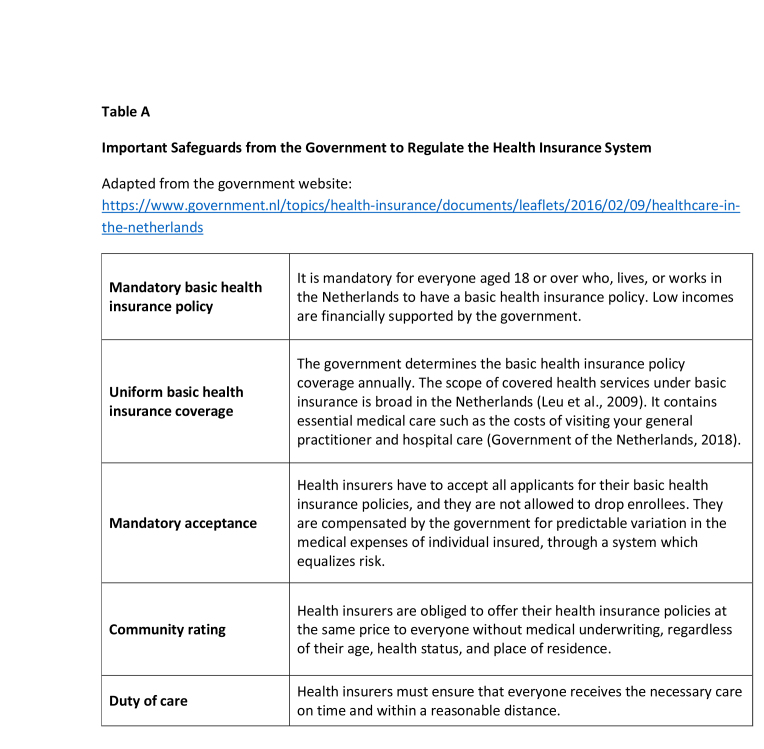

Several countries have a health insurance system based on managed competition (Cabiedes & Guillén, 2001; Mossialos et al., 2016; Shmueli et al., 2015) in which various private health insurers offer insurance policies to citizens. The idea behind managed competition is that health insurers compete for the enrollment of citizens, which should stimulate them to provide good quality of care for a competitive price (Authority for Consumers & Markets, 2016). In 2006, managed competition was introduced in the Dutch health insurance system (Enthoven & van de Ven, 2007). The government remains responsible for the preconditions regarding accessibility, quality, and affordability of health care in the Netherlands. Therefore, several safeguards are set by the government in to regulate the health insurance system. For example, it is mandatory for all citizens in the Netherlands to have a basic insurance policy, the government determines the basic insurance policy coverage, and health insurers accept all applicants for their basic insurance policies. Table A contains an overview of the most important safeguards applied by the government to regulate the health insurance system.

Table A.

Important Safeguards from the Government to Regulate the Health Insurance System

Adapted from the government website: https://www.government.nl/topics/health-insurance/documents/leaflets/2016/02/09/healthcare-in-the-netherlands

| Mandatory basic health insurance policy | It is mandatory for everyone aged 18 or over who, lives, or works in the Netherlands to have a basic health insurance policy. Low incomes are financially supported by the government. |

| Uniform basic health insurance coverage | The government determines the basic health insurance policy coverage annually. The scope of covered health services under basic insurance is broad in the Netherlands (Leu et al., 2009). It contains essential medical care such as the costs of visiting your general practitioner and hospital care (Government of the Netherlands, 2018). |

| Mandatory acceptance | Health insurers have to accept all applicants for their basic health insurance policies, and they are not allowed to drop enrollees. They are compensated by the government for predictable variation in the medical expenses of individual insured, through a system which equalizes risk. |

| Community rating | Health insurers are obliged to offer their health insurance policies at the same price to everyone without medical underwriting, regardless of their age, health status, and place of residence. |

| Duty of care | Health insurers must ensure that everyone receives the necessary care on time and within a reasonable distance. |

The possibility for citizens to choose a suitable insurance policy every year is an essential part of the functioning of the Dutch health insurance system (De Jong & Brabers, 2019). The system is based on the idea that citizens switch from an insurer if they are dissatisfied or if another insurer has a better offer (Boonen & Laske-Aldershof, 2016; Laske-Aldershof et al., 2004). Consequently, they are supposed to ask themselves, critically, whether their current insurer still fulfills their needs and preferences, or if they want to switch insurers. To fulfill this role, citizens must be able to make a well-informed decision every year as to which health insurance policy suits them best. There are three main considerations to be made by citizens when choosing a suitable health insurance policy: (1) the type of basic health insurance policy, (2) the possibility of opting for a voluntary deductible, and (3) the possibility of taking out a supplementary health insurance policy.

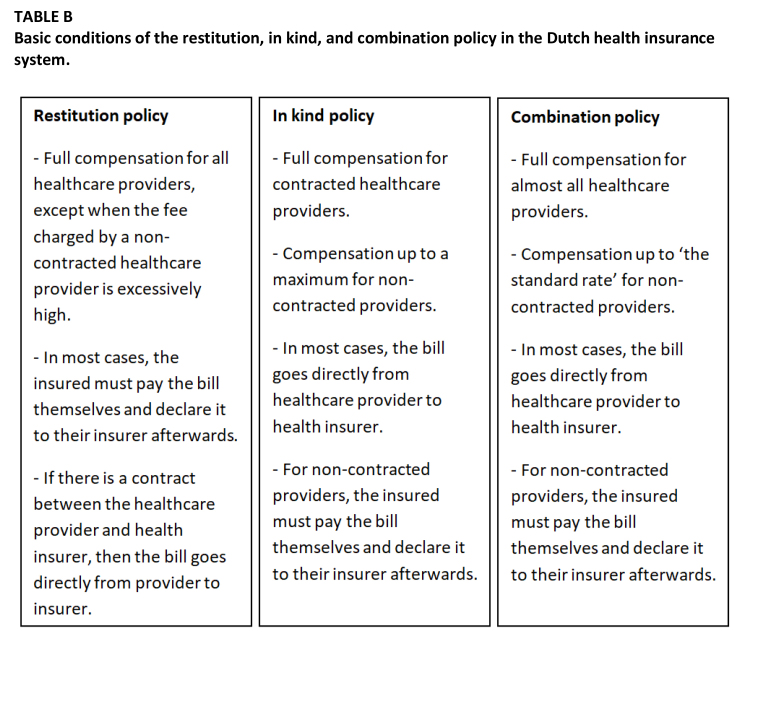

First, when choosing the type of basic health insurance policy, citizens in the Netherlands can choose between a non-contracted care policy (restitution policy), a contracted care policy (in-kind policy), or a combination of the two (combination policy). Table B presents the basic conditions of the different policy types. The premium differs between these three types; the restitution policy is often more expensive. In 2018, citizens in the Netherlands could choose between 55 basic health insurance policies (20 restitution, 31 in kind, and 4 combination policies) offered by 24 different insurance companies (Dutch Healthcare Authority, 2018). Ultimately, 75% chose an in-kind policy, 19% a restitution policy, and 5% a combination policy (Dutch Healthcare Authority, 2018).

Table B.

Basic conditions of the restitution, in kind, and combination policy in the Dutch health insurance system.

Restitution policy

|

In kind policy

|

Combination policy

|

The second consideration concerns the deductible, which is the amount that citizens must pay out-of-pocket before an insurer reimburses the costs. On top of the compulsory deductible set by the government (€385, approximately $447, in the period 2016–2020), citizens can opt for a voluntary deductible varying of €100 (approximately $116), €200 (approximately $232), €300 (approximately $348), €400 (approximately $464), or €500 (approximately $580) per year. When choosing a voluntary deductible, citizens then receive a reduction on the premium. Choosing a voluntary deductible can be beneficial for citizens if they expect to make little use of health care in the upcoming year. In 2018, 13% of all citizens in the Netherlands chose a voluntary deductible. Most of them opted for the maximum voluntary deductible of €500 (Dutch Healthcare Authority, 2018).

Third, in addition to the mandatory basic health insurance policy, citizens can choose to take out a supplementary health insurance policy from any health insurer. Supplementary insurance policies provide coverage for additional health care services such as dental care and physiotherapy (Government of the Netherlands, 2018). In comparison to the basic health insurance system, the supplementary insurance system is not regulated by the government. As a result, no safeguards have been set up in this system. Insurers are free to determine the premium and coverage of their supplementary insurance policies, and insurers do not have to accept all applicants for their policies. In 2018, there were 222 supplementary insurance policies to choose from, of which the extent of the coverage can be distinguished into roughly 5 types (Zuidhof et al., 2019). A majority (84%) of all citizens in the Netherlands chose to take out a supplementary insurance policy (Dutch Healthcare Authority, 2018).

Altogether, the number of health insurance policy options to choose from is extensive in the Netherlands. The Dutch Healthcare Authority calculated that almost 6,000 different combinations were possible in 2015 (Dutch Healthcare Authority, 2015). Citizens are supposed to choose annually which type of basic insurance policy they want to have, whether to opt for a voluntary deductible and whether to take out a supplementary insurance policy for the coming year. All these choices make it complicated for citizens to choose an insurance policy that best fits their needs and preferences.

In recent years, the main strategy for supporting citizens in choosing a suitable health insurance policy is to provide more information about the different types of policies available. However, the mere provision of information about health insurance policies does not lead to citizens being better informed (De Jong et al., 2017; Peters et al., 2013). Furthermore, a significant group of citizens in the Netherlands do not fully understand either the role of health insurers or the detailed structure of health insurance policies (Hoefman et al., 2015; Maarse & Jeurissen, 2019). There are indications that a significant group of citizens do not make rational decisions when choosing an insurance policy (Rice, 2013) resulting in a policy that does not best suit their situation (van Winssen et al., 2016). This can ultimately lead to citizens facing inadequate policy coverage and unexpected costs.

To make well-informed decisions concerning health insurance policies, citizens need certain skills to comprehend and use health insurance information. These skills are called health insurance literacy and are referred to as “‘the extent to which insured can make informed purchase and use decisions regarding health insurance” (Kim et al., 2013, p. 3). We focus, in this study, on how citizens in the Netherlands perceive choosing a health insurance policy. More specifically, our research questions are (1) How important is it for citizens in the Netherlands to choose an insurance policy?; and (2) How easy is it for citizens in the Netherlands to comprehend the information they receive about choosing a health insurance policy? We examine whether the questions differ according to sociodemographic characteristics of sex, age, and level of education.

Method

Panel

We sent a survey to members of Nivel's (Netherlands Institute for Health Services Research) Dutch Health Care Consumer Panel (DHCCP) in February 2017 (Brabers et al., 2015) to get insight into how important citizens found choosing a health insurance policy, and how comprehensible they found the process. The DHCCP is a so-called access panel (Brabers et al., 2015), which consisted at the time of this study approximately 12,000 people who have agreed to answer questions related to health on a regular basis. The background characteristics of these people, such as their age, level of education, self-reported general health, and health literacy level, are known. There is no possibility of people signing up for the DHCCP on their own initiative.

Data were analyzed anonymously, and processed according to the Consumer Panel privacy policy, which complies with the General Data Protection Regulation. According to Dutch legislation, neither obtaining informed consent nor approval by a medical ethics committee is obligatory for carrying out research in the panel (Central Committee on Research Involving Human Subjects, 2019). Participation in the panel is voluntary. Panel members are not forced to participate in surveys, and they can stop their membership of the panel at any time without mention any reason for stopping.

Survey

For this study, 1,500 members of the DHCCP were approached online or on paper (mixed mode) according to their preferences. The sample was representative of the Dutch population age 18 years and older with regards to sex and age. Panel members were free to answer the questions. They did not have to fill out all the questions within the survey; they could skip a question if they could not or did not want to answer that specific question. The results described in this study are based on the answers from 659 respondents (response rate 44%). The questions in this study were part of Nivel's annual monitoring of switching health insurer. This monitor examines, among other things, the number of citizens who switched insurers and their reasons for switching. In this study, we examined how important and easy it is for citizens to choose a health insurance policy. A multidisciplinary research team including experts in the Dutch health care system and J. D. de Jong and A.E.M. Brabers developed the survey. The draft survey was also commented on by the program committee of the Dutch Health Care Consumer Panel, consisting of representatives of different actors in the health care sector, including the Dutch Ministry of Health, Welfare and Sport, the Dutch Consumers Association, and the umbrella organization of health insurers in The Netherlands, Zorgverzekeraars Nederland.

Measurement

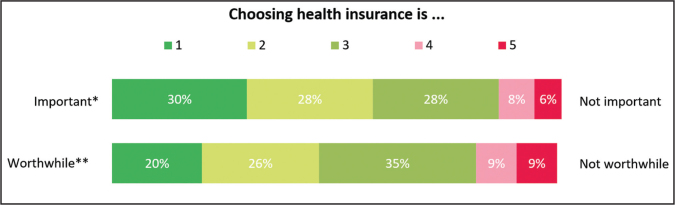

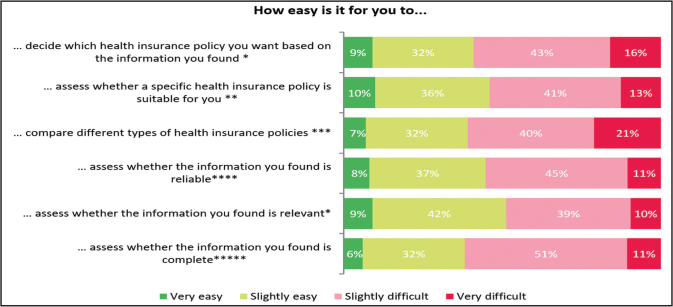

The main outcome measures in this study were to what extent citizens indicated that it was important and easy for them to choose a health insurance policy. Two statements focused on importance. These were choosing a health insurance policy is (1) important/not important and (2) worthwhile/not worthwhile. Answers to these two statements included a scale from 1 to 5, in which score 1 was important/ worthwhile, and score 5 was not important/not worthwhile (Figure 1). Six statements focused on the ease of choosing a policy. These were how easy was it for you to (1) decide which health insurance policy you want based on the information you found; (2) assess whether a specific health insurance policy is suitable for you; (3) compare different types of health insurance policies; (4) assess whether the information you found is reliable; (5) assess whether the information you found is relevant; and (6) assess whether the information you found is complete (Figure 2). These six statements consisted of four categories: very easy, slightly easy, slightly difficult, and very difficult.

Figure 1.

The extent to which the respondents insured in the Netherlands consider it important and worthwhile to choose a health insurance policy in 2017. *n = 570; **n = 552.

Figure 2.

The perception among the respondents of their skills in comprehending health insurance information in 2017. *n = 589; **n = 593; ***n = 587; ****n = 600; *****n = 594.

To get a better understanding of how important and easy it is for different groups of citizens to choose a health insurance policy, we included the following sociodemographic characteristics: sex (1 = male, 2 = female); age, divided into three categories (1 = 18–39 years, 2 = 40–64 years, 3 = 65 years and older), and; level of education, divided into three categories (low = none, primary school or pre-vocational education; intermediate = secondary or vocational education, and; high = professional higher or university).

Statistical Analyses

Descriptive analyses were performed to examine the composition of the respondents. We then performed descriptive statistics to get insight into how important and easy it is for the respondents to choose a health insurance policy. Differences between groups of respondents (sex, age, level of education) were tested using one-way ANOVA's and Tukey post-hoc tests.

Results

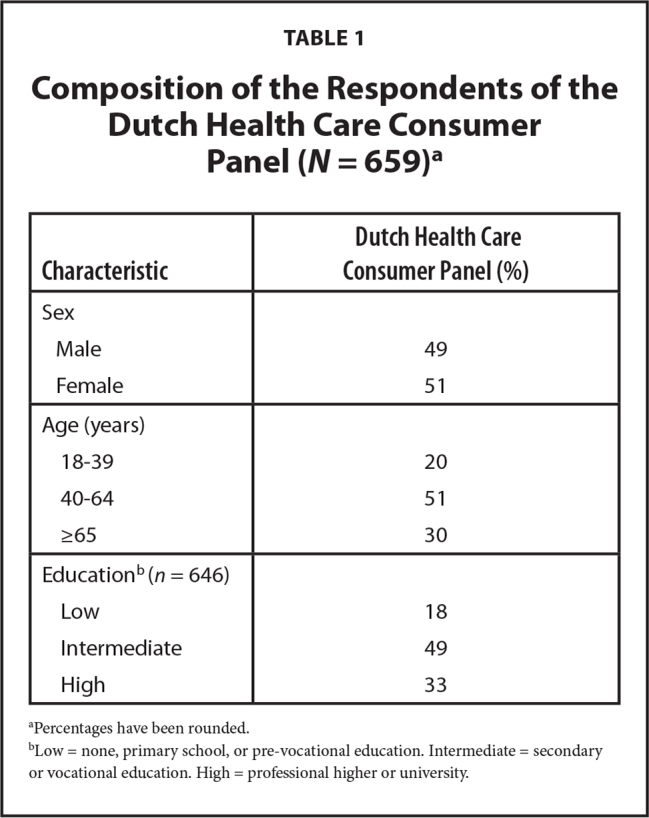

Table 1 shows the composition of the members of the DHCCP who responded to the survey. The average age of the respondents was 57 years, and the male to female ratio was 49/51. Approximately, one-fifth of the respondents had a low level of education (18%). The average age of the general population in the Netherlands in 2017 was respectively 42 years; the male to female ratio was 50/50; and approximately 3 of 10 had a low level of education (32%) (Central Bureau for Statistics, 2017).

Table 1.

Composition of the Respondents of the Dutch Health Care Consumer Panel (N = 659)a

| Characteristic | Dutch Health Care Consumer Panel (%) |

|---|---|

|

| |

| Sex | |

| Male | 49 |

| Female | 51 |

|

| |

| Age (years) | |

| 18–39 | 20 |

| 40–64 | 51 |

| ≥65 | 30 |

|

| |

| Educationb (n = 646) | |

| Low | 18 |

| Intermediate | 49 |

| High | 33 |

Percentages have been rounded.

Low = none, primary school, or pre-vocational education. Intermediate = secondary or vocational education. High = professional higher or university.

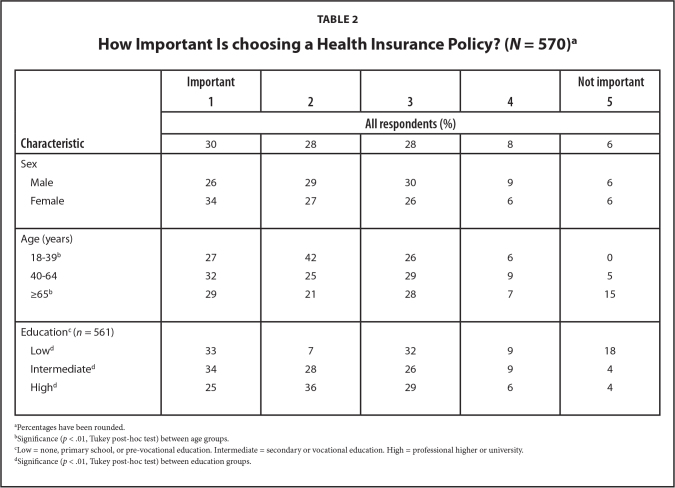

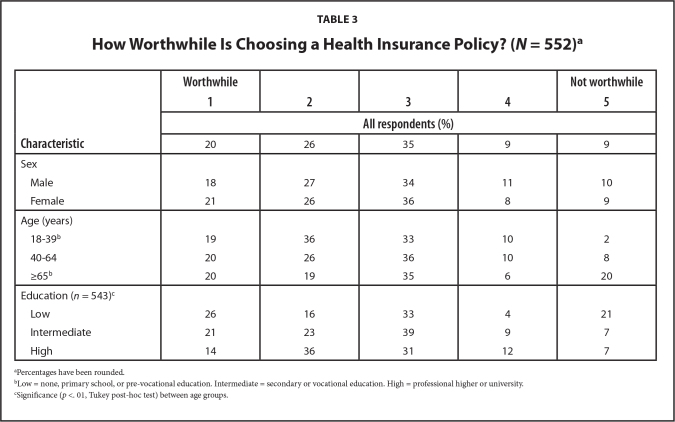

Figure 1 shows that 58% of the respondents indicated that choosing a health insurance policy is important (score 1 and 2), and 46% indicated that choosing an insurance policy is worthwhile. Table 2 and Table 3 show that the age and level of education of the respondents are associated with these opinions (p < .01, ANOVA). Younger (age 18–39 years) respondents indicated, to a greater extent (p < .01, Tukey post-hoc test), that choosing an insurance policy is important (69%) and worthwhile (55%), than older (age 65 years and older) respondents (50% and 39%, respectively). Furthermore, respondents with an intermediate or high level of education indicated to a greater extent (p < .01, Tukey post-hoc test) that choosing an insurance policy is important (62% and 61%, respectively, compared to respondents with a low level of education (40%).

Table 2.

How Important Is choosing a Health Insurance Policy? (N = 570)a

| Characteristic | Important 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | Not important 5 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||||

| All respondents (%) | |||||

|

| |||||

| 30 | 28 | 28 | 8 | 6 | |

|

| |||||

| Sex | |||||

| Male | 26 | 29 | 30 | 9 | 6 |

| Female | 34 | 27 | 26 | 6 | 6 |

|

| |||||

| Age (years) | |||||

| 18–39b | 27 | 42 | 26 | 6 | 0 |

| 40–64 | 32 | 25 | 29 | 9 | 5 |

| ≥65b | 29 | 21 | 28 | 7 | 15 |

|

| |||||

| Educationc (n = 561) | |||||

| Lowd | 33 | 7 | 32 | 9 | 18 |

| Intermediated | 34 | 28 | 26 | 9 | 4 |

| Highd | 25 | 36 | 29 | 6 | 4 |

Percentages have been rounded.

Significance (p < .01, Tukey post-hoc test) between age groups.

Low = none, primary school, or pre-vocational education. Intermediate = secondary or vocational education. High = professional higher or university.

Significance (p < .01, Tukey post-hoc test) between education groups.

Table 3.

How Worthwhile Is Choosing a Health Insurance Policy? (N = 552)a

| Characteristic | Worthwhile 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | Not worthwhile 5 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||||

| All respondents (%) | |||||

|

| |||||

| 20 | 26 | 35 | 9 | 9 | |

|

| |||||

| Sex | |||||

| Male | 18 | 27 | 34 | 11 | 10 |

| Female | 21 | 26 | 36 | 8 | 9 |

|

| |||||

| Age (years) | |||||

| 18–39b | 19 | 36 | 33 | 10 | 2 |

| 40–64 | 20 | 26 | 36 | 10 | 8 |

| ≥65b | 20 | 19 | 35 | 6 | 20 |

|

| |||||

| Education (n = 543)c | |||||

| Low | 26 | 16 | 33 | 4 | 21 |

| Intermediate | 21 | 23 | 39 | 9 | 7 |

| High | 14 | 36 | 31 | 12 | 7 |

Percentages have been rounded.

Low = none, primary school, or pre-vocational education. Intermediate = secondary or vocational education. High = professional higher or university.

Significance (p <. 01, Tukey post-hoc test) between age groups.

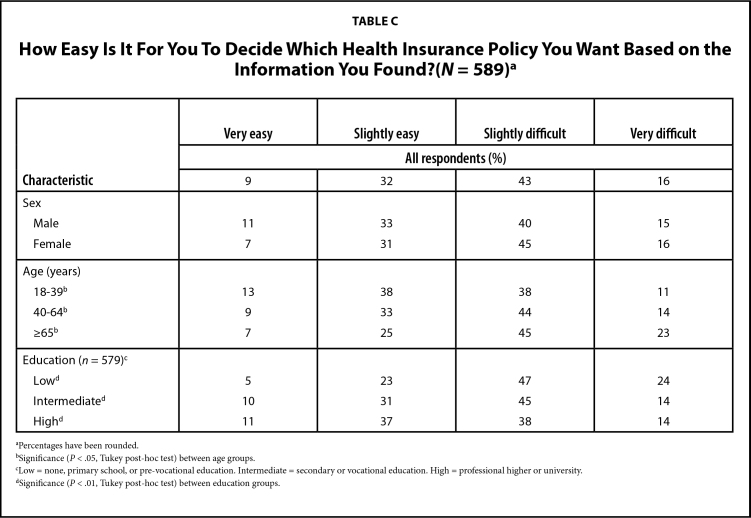

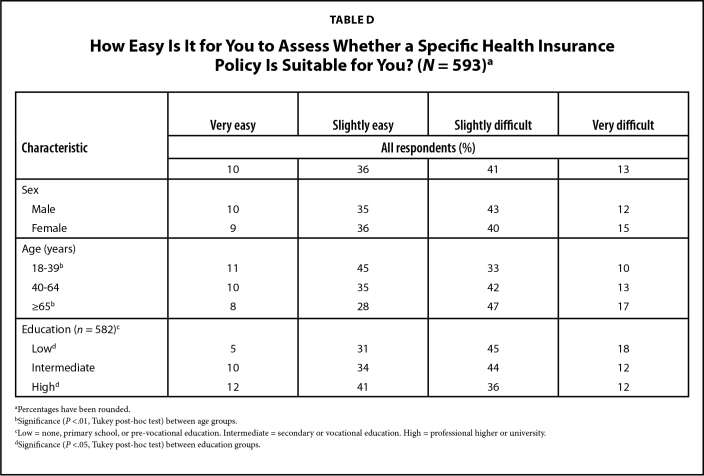

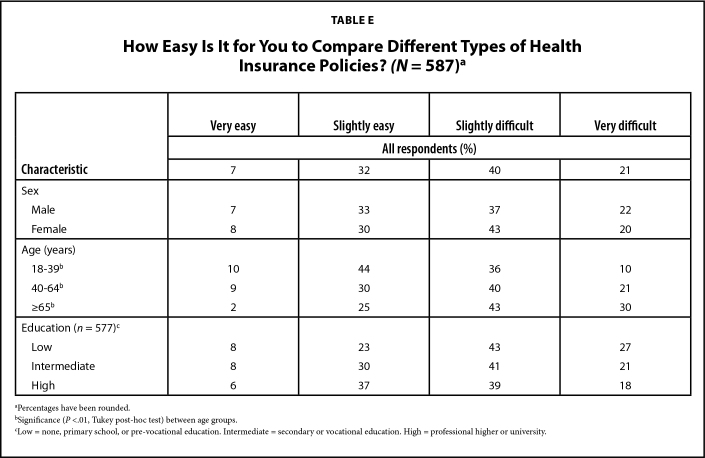

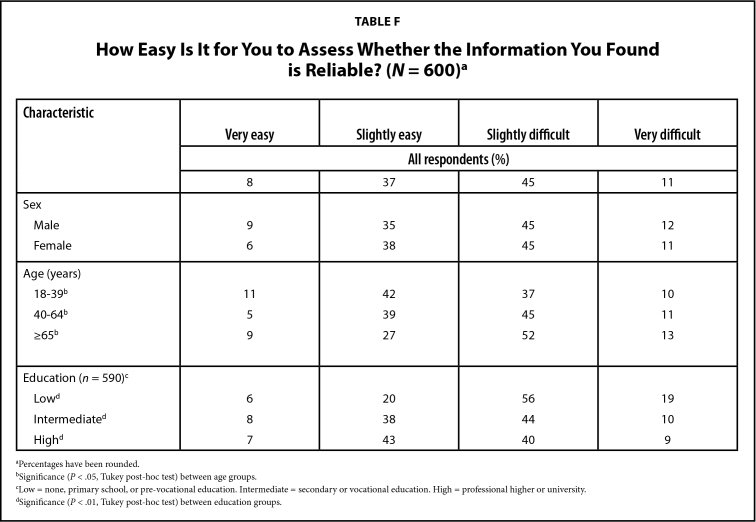

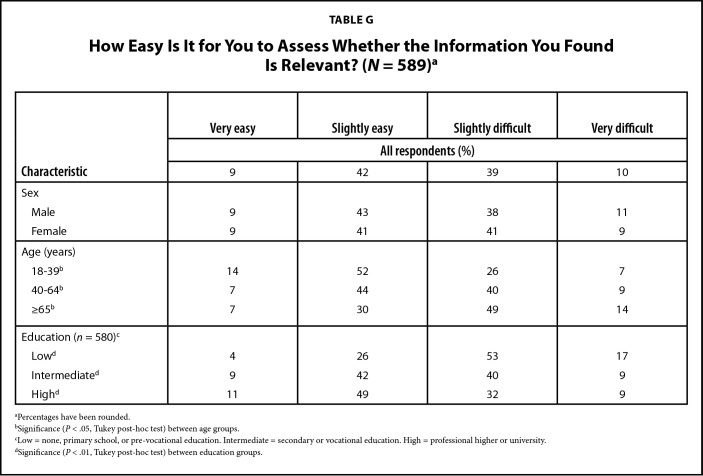

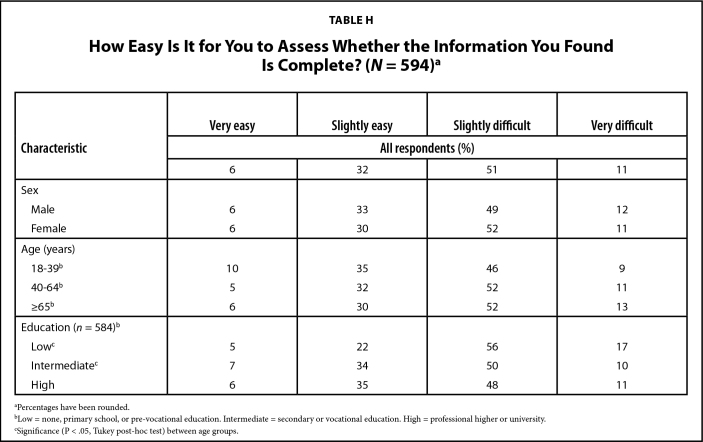

Furthermore, the respondents pointed out that it is diffcult to comprehend health insurance information. Figure 2 shows that a significant group of the respondents indicated that it was slightly or very difficult to decide which health insurance policy they wanted (59%), to assess whether a specific insurance policy was suitable for them (54%), and to compare different types of health insurance policies (61%). Approximately one-half found it slightly or very difficult to assess information on reliability (56%), relevance (49%), and completeness (62%).

The age and the level of education of the respondents are also associated with how these statements about comprehending health insurance information are assessed. In general, the younger and more highly educated respondents indicated, to a greater extent, that they comprehend information about health insurances compared to the older and lower educated respondents (p < .05, ANOVA). For example, young respondents (age 18-39 years) and respondents with a high level of education indicated, to a greater extent, that it is slightly or very easy (65% and 53%, respectively) to assess whether a specific health insurance policy is suitable for them as compared to older respondents (age 65 years and older) and respondents with a low level of education (both 36%). For each statement about comprehending health insurance information, the differences between specific groups of age and level of education can be found in Tables C–H.

Table C.

How easy Is It For You To Decide Which Health Insurance Policy You Want Based on the Information You Found?(N = 589)a

| Characteristic | Very easy | Slightly easy | Slightly difficult | Very difficult |

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||

| All respondents (%) | ||||

|

| ||||

| 9 | 32 | 43 | 16 | |

|

| ||||

| Sex | ||||

| Male | 11 | 33 | 40 | 15 |

| Female | 7 | 31 | 45 | 16 |

|

| ||||

| Age (years) | ||||

| 18–39b | 13 | 38 | 38 | 11 |

| 40–64b | 9 | 33 | 44 | 14 |

| ≥65b | 7 | 25 | 45 | 23 |

|

| ||||

| Education (n = 579)c | ||||

| Lowd | 5 | 23 | 47 | 24 |

| Intermediated | 10 | 31 | 45 | 14 |

| Highd | 11 | 37 | 38 | 14 |

Percentages have been rounded.

Significance (P < .05, Tukey post-hoc test) between age groups.

Low = none, primary school, or pre-vocational education. Intermediate = secondary or vocational education. High = professional higher or university.

Significance (P < .01, Tukey post-hoc test) between education groups.

Table D.

How easy Is It for You to Assess Whether a Specific Health Insurance Policy Is Suitable for You? (N = 593)a

| Characteristic | Very easy | Slightly easy | Slightly difficult | Very difficult |

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||

| All respondents (%) | ||||

|

|

||||

| 10 | 36 | 41 | 13 | |

|

| ||||

| Sex | ||||

| Male | 10 | 35 | 43 | 12 |

| Female | 9 | 36 | 40 | 15 |

|

| ||||

| Age (years) | ||||

| 18–39b | 11 | 45 | 33 | 10 |

| 40–64 | 10 | 35 | 42 | 13 |

| ≥65b | 8 | 28 | 47 | 17 |

|

| ||||

| Education (n = 582)c | ||||

| Lowd | 5 | 31 | 45 | 18 |

| Intermediate | 10 | 34 | 44 | 12 |

| Highd | 12 | 41 | 36 | 12 |

Percentages have been rounded.

Significance (P <.01, Tukey post-hoc test) between age groups.

Low = none, primary school, or pre-vocational education. Intermediate = secondary or vocational education. High = professional higher or university.

Significance (P <.05, Tukey post-hoc test) between education groups.

Table E.

How easy Is It for You to Compare Different Types of Health Insurance Policies? (N = 587)a

| Characteristic | Very easy | Slightly easy | Slightly difficult | Very difficult |

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||

| All respondents (%) | ||||

|

| ||||

| 7 | 32 | 40 | 21 | |

|

| ||||

| Sex | ||||

| Male | 7 | 33 | 37 | 22 |

| Female | 8 | 30 | 43 | 20 |

|

| ||||

| Age (years) | ||||

| 18–39b | 10 | 44 | 36 | 10 |

| 40–64b | 9 | 30 | 40 | 21 |

| ≥65b | 2 | 25 | 43 | 30 |

|

| ||||

| Education (n = 577)c | ||||

| Low | 8 | 23 | 43 | 27 |

| Intermediate | 8 | 30 | 41 | 21 |

| High | 6 | 37 | 39 | 18 |

Percentages have been rounded.

Significance (P <.01, Tukey post-hoc test) between age groups.

Low = none, primary school, or pre-vocational education. Intermediate = secondary or vocational education. High = professional higher or university.

Table F.

How easy Is It for You to Assess Whether the Information You Found is Reliable? (N = 600)a

| Characteristic | Very easy | Slightly easy | Slightly difficult | Very difficult |

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||

| All respondents (%) | ||||

|

| ||||

| 8 | 37 | 45 | 11 | |

|

| ||||

| Sex | ||||

| Male | 9 | 35 | 45 | 12 |

| Female | 6 | 38 | 45 | 11 |

|

| ||||

| Age (years) | ||||

| 18–39b | 11 | 42 | 37 | 10 |

| 40–64b | 5 | 39 | 45 | 11 |

| ≥65b | 9 | 27 | 52 | 13 |

|

| ||||

| Education (n = 590)c | ||||

| Lowd | 6 | 20 | 56 | 19 |

| Intermediated | 8 | 38 | 44 | 10 |

| Highd | 7 | 43 | 40 | 9 |

Percentages have been rounded.

Significance (P < .05, Tukey post-hoc test) between age groups.

Low = none, primary school, or pre-vocational education. Intermediate = secondary or vocational education. High = professional higher or university.

Significance (P < .01, Tukey post-hoc test) between education groups.

Table G.

How easy Is It for You to Assess Whether the Information You Found Is Relevant? (N = 589)a

| Characteristic | Very easy | Slightly easy | Slightly difficult | Very difficult |

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||

| All respondents (%) | ||||

|

| ||||

| 9 | 42 | 39 | 10 | |

|

| ||||

| Sex | ||||

| Male | 9 | 43 | 38 | 11 |

| Female | 9 | 41 | 41 | 9 |

|

| ||||

| Age (years) | ||||

| 18–39b | 14 | 52 | 26 | 7 |

| 40–64b | 7 | 44 | 40 | 9 |

| ≥65b | 7 | 30 | 49 | 14 |

|

| ||||

| Education (n = 580)c | ||||

| Lowd | 4 | 26 | 53 | 17 |

| Intermediated | 9 | 42 | 40 | 9 |

| Highd | 11 | 49 | 32 | 9 |

Percentages have been rounded.

Significance (P < .05, Tukey post-hoc test) between age groups.

Low = none, primary school, or pre-vocational education. Intermediate = secondary or vocational education. High = professional higher or university.

Significance (P < .01, Tukey post-hoc test) between education groups.

Table H.

How easy Is It for You to Assess Whether the Information You Found Is Complete? (N = 594)a

| Characteristic | Very easy | Slightly easy | Slightly difficult | Very difficult |

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||

| All respondents (%) | ||||

|

| ||||

| 6 | 32 | 51 | 11 | |

|

| ||||

| Sex | ||||

| Male | 6 | 33 | 49 | 12 |

| Female | 6 | 30 | 52 | 11 |

|

| ||||

| Age (years) | ||||

| 18–39b | 10 | 35 | 46 | 9 |

| 40–64b | 5 | 32 | 52 | 11 |

| ≥65b | 6 | 30 | 52 | 13 |

|

| ||||

| Education (n = 584)b | ||||

| Lowc | 5 | 22 | 56 | 17 |

| Intermediatec | 7 | 34 | 50 | 10 |

| High | 6 | 35 | 48 | 11 |

Percentages have been rounded.

Low = none, primary school, or pre-vocational education. Intermediate = secondary or vocational education. High = professional higher or university.

Significance (P < .05, Tukey post-hoc test) between age groups.

Discussion

Many of the respondents acknowledged that it is important to choose a health insurance policy. To do this properly, they have to inform themselves about the different aspects of health insurance policies. However, many respondents also pointed out that they find it difficult to assess information on different types of health insurance policies. Based on the information they received, they do not seem to have appropriate skills to decide which policy fits their needs and preferences best. These results are in line with the results of the Health Care Monitor 2019 (van der Grient & Keuchenius, 2019), conducted by the Authority for Consumers & Markets (2016). The report concluded that people insured in the Netherlands have a need to know which health care services they are insured for, but also indicated that it is difficult to find out what the different health insurance policies cover.

Our results show that the older respondents and those with lower education less often indicated that choosing an insurance policy is important than the younger respondents and those with higher education. Furthermore, they also indicated more often that they did not comprehend the information they received about choosing an insurance policy. We see a similar pattern in health literacy research, which focuses on the ability of people to make sound decisions concerning health in daily life (Kickbusch & Maag, 2008). In several European countries, limited health literacy is more common in older people with less education (Sørensen et al., 2015). This indicates that there are specific vulnerable groups when it comes to making good health decisions. Our findings suggest that there are also specific vulnerable groups—in this case older people and citizens with lower education, when choosing a health insurance policy.

In addition to a lack of skills among a section of citizens when it comes to deciding which insurance policy fits their needs and preferences best, a lack of motivation can also be a reason why citizens do not inform themselves about the different aspects of health insurance policies. Other research confirms that people who are insured can be overwhelmed by the number of choices in health insurance policy (Lako et al., 2011). This idea is supported by the theory of “decision avoidance” described by Anderson (2003, p. 139) as “a tendency to avoid making a choice by postponing it or by seeking an easy way out that involves no action or no change.” However, our results indicated that citizens in the Netherlands acknowledge that it is important to choose a health insurance policy. It seems, therefore, questionable to what extent a lack of motivation among citizens is associated with their willingness to inform themselves about the different aspects of health insurance policies.

Study Limitations

A limitation of our study is that the respondents were relatively older and with higher education than the general population in the Netherlands. The perception of the importance and comprehensibility among the respondents may therefore slightly differ from the perception of all citizens in the Netherlands. Furthermore, we are aware that this study focuses on respondents' own perceptions. It does not objectively measure whether the information about health insurance policies is comprehensible. An advantage of using such a subjective measure is that it provides insight into relevant problems that citizens face when choosing an insurance policy. A drawback is that it does not measure how citizens actually make choices regarding a policy, and whether these are suitable for their situation. From previous research, we know that people with low skills often overestimate themselves in performing different tasks, and people with high skills underestimate themselves—The Dunning-Kruger Effect (Kruger & Dunning, 1999).

Conclusions

In a well-functioning health insurance system based on managed competition, insurers are stimulated to offer citizens a good quality of care for a competitive price. To maintain competition among insurers, it is important that all citizens can make well-informed decisions on which insurance policy fits their needs and preferences best. There are several ways to accommodate citizens with this task. One possible way is to make the health care system less complex by simplifying the variety of health insurance policy options or by reducing the number of policies. Another possibility is to better tailor the information provision about health insurance policies to the skills of the citizens. This study focused on the second strategy to better tailor the information provision. Our results suggest that a section of the citizens in the Netherlands do not seem to have the appropriate skills to make well-informed decisions on which insurance policy fits their needs and preferences best. More specific attention is needed to support the group of citizens who struggle with this task. We recommend other countries with a health insurance system based on managed competition pay attention to the extent to which citizens can fulfill their role in the health insurance system. It is a challenge to provide information on health insurance policies in such a way that everyone can comprehend them.

In the Netherlands, a greater understanding of the health insurance literacy among citizens is needed to gain more insight into the skills of citizens in choosing a suitable health insurance policy. It is an important step in the process evaluating the extent to which citizens can fulfill their role in the health insurance system. Our results suggest that it is important to better tailor information on health insurances to the specific needs and skills of the individual. In this way, citizens could be better supported in making well-informed decisions regarding health insurance policies, which should have a positive effect on the functioning of the health insurance system in the Netherlands.

Key Points

Many citizens in the Netherlands acknowledge the importance of, and difficulty in, choosing a health insurance policy.

Insight into the level of health insurance literacy among citizens in the Netherlands is an important step in the process evaluating the extent to which citizens can fulfill their role in the health insurance system.

Better support for citizens in making well-informed decisions regarding health insurance policies should have a positive effect on the functioning of the health insurance system in the Netherlands.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank all Dutch Health Care Consumer Panel members for completing the survey.

References

- Anderson , C. J. ( 2003. ). The psychology of doing nothing: Forms of decision avoidance result from reason and emotion . Psychological Bulletin , 129 ( 1 ), 139 – 167 . 10.1037/0033-2909.129.1.139 PMID: [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Authority for Consumers & Markets . ( 2016. ). Competition in the Dutch health insurance market 2016 . https://www.acm.nl/sites/default/files/old_publication/publicaties/16129_competition-in-the-dutch-health-insurance-market.pdf [Google Scholar]

- Boonen , L. H. H. M. , Laske-Aldershof , T. , & Schut , F. T. ( 2016. ). Switching health insurers: The role of price, quality and consumer information search . The European Journal of Health Economics , 17 , 339 – 353 . 10.1007/s10198-015-0681-1 PMID: [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brabers , A. E. , Reitsma-van Rooijen , M. , & De Jong , J. D. ( 2015. ). Consumentenpanel Gezondheidszorg Basisrapport [Basic rapport of the Dutch Health Care Consumer Panel, including English summary] . https://www.nivel.nl/sites/default/files/bestanden/Basisrapport-Consumentenpanel-2015.pdf [Google Scholar]

- Cabiedes , L. , & Guillén , A . ( 2001. ). Adopting and adapting managed competition: Health care reform in Southern Europe . Social Science & Medicine , 52 ( 8 ), 1205 – 1217 . 10.1016/S0277-9536(00)00240-9 PMID: [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Central Bureau for Statistics . ( 2017. ). Statline open data . https://opendata.cbs.nl/#/CBS/nl/ [Google Scholar]

- Central Committee on Research Involving Human Subjects . ( 2019. ). Your research: Is it subject to the WMO or not? https://english.ccmo.nl/investigators/legal-framework-for-medical-scientific-research/your-research-is-it-subject-to-the-wmo-or-not

- De Jong J. D. , & Brabers A. E. M . ( 2019. ). Switching health insurer in the Netherlands: Price competition but lacking competition on quality . Eurohealth (London) , 25 ( 4 ), 22 – 25 [Google Scholar]

- De Jong J. D. , van Esch T. E. M. , & Brabers A. E. M. ( 2017. ). De zorgverzekeringsmarkt: gedrag, kennis en solidariteit [The health insurance market: behavior, knowledge, and solidarity] . https://www.nivel.nl/sites/default/files/bestanden/Kennissynthese_De_zorgverzekeringsmarkt_gedrag_kennis_solidariteit.pdf [Google Scholar]

- Dutch Healthcare Authority . ( 2015. ). Marktscan van de Zorgverzekeringsmarkt [Market scan of the health insurance market] . https://puc.overheid.nl/nza/doc/PUC_3341_22/1/ [Google Scholar]

- Dutch Healthcare Authority . ( 2018. ). Monitor Zorgverzekeringen [Monitor health insurance policies] . https://puc.overheid.nl/nza/doc/PUC_254666_22/1/ [Google Scholar]

- Enthoven , A. C. , & van de Ven , W. P. ( 2007. ). Going Dutch—Managed-competition health insurance in the Netherlands . The New England Journal of Medicine , 357 ( 24 ), 2421 – 2423 . 10.1056/NEJMp078199 PMID: [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Government of the Netherlands . ( 2018. ). Healthcare in the Netherlands 2018 . https://www.government.nl/topics/health-insurance/documents/leaflets/2016/02/09/healthcare-in-the-netherlands [Google Scholar]

- Hoefman , R. , Brabers , A. , & De Jong , J. D. ( 2015. ). Vertrouwen in zorgverzekeraars hangt samen met opvatting over taken zorgverzekeraars [Trust in health insurers is associated with views on health insurers' duties] . https://www.nivel.nl/sites/default/files/bestanden/Factsheet-Vertrouwen-in-zorgverzekeraars.pdf

- Kickbusch , I. , & Maag , D . ( 2008. ). Health literacy . International Encyclopedia of Public Health; . http://www.ilonakickbusch.com/kickbuschwAssets/docs/kickbusch-maag.pdf [Google Scholar]

- Kim , J. , Braun , B. , & Williams , A. D. ( 2013. ). Understanding health insurance literacy: A literature review . Family and Consumer Sciences Research Journal , 42 ( 1 ), 3 – 13 . 10.1111/fcsr.12034 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kruger , J. , & Dunning , D . ( 1999. ). Unskilled and unaware of it: How difficulties in recognizing one's own incompetence lead to inflated self-assessments . Journal of Personality and Social Psychology , 77 ( 6 ), 1121 – 1134 . 10.1037/0022-3514.77.6.1121 PMID: [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lako , C. J. , Rosenau , P. , & Daw , C . ( 2011. ). Switching health insurance plans: Results from a health survey . Health Care Analysis , 19 ( 4 ), 312 – 328 . 10.1007/s10728-010-0154-8 PMID: [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Laske-Aldershof , T. , Schut , E. , Beck , K. , Gress , S. , Shmueli , A. , & Van de Voorde , C. ( 2004. ). Consumer mobility in social health insurance markets: A five-country comparison . Applied Health Economics and Health Policy , 3 ( 4 ), 229 – 241 . 10.2165/00148365-200403040-00006 PMID: [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leu , R. , Rutten , F. , Brouwer , W. , Matter , P. , & Rütschi , C . ( 2009. ). The Swiss and Dutch health insurance systems: Universal coverage and regulated competitive insurance markets . https://www.commonwealthfund.org/publications/fund-reports/2009/jan/swiss-and-dutch-health-insurance-systems-universal-coverage-and [Google Scholar]

- Maarse , H. , & Jeurissen , P. ( 2019. ). Low institutional trust in health insurers in Dutch health care . Health Policy (Amsterdam) , 123 ( 3 ), 288 – 292 . 10.1016/j.health-pol.2018.12.008 PMID: [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mossialos , E. , Djordjevic , A. , Osborn , R. , & Sarnak , D . ( 2016. ). 2015 International profiles of health care systems . The Commonwealth Fund; . https://www.commonwealthfund.org/sites/default/files/documents/___media_files_publications_fund_report_2016_jan_1857_mossialos_intl_profiles_2015_v7.pdf [Google Scholar]

- Peters , E. , Klein , W. , Kaufman , A. , Meilleur , L. , & Dixon , A. ( 2013. ). More is not always better: intuitions about effective public policy can lead to unintended consequences . Social Issues and Policy Review , 7 ( 1 ), 114 – 148 . 10.1111/j.1751-2409.2012.01045.x PMID: [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rice , T . ( 2013. ). The behavioral economics of health and health care . Annual Review of Public Health , 34 , 431 – 447 . 10.1146/annurev-publhealth-031912-114353 PMID: [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shmueli , A. , Stam , P. , Wasem , J. , & Trottmann , M. ( 2015. ). Managed care in four managed competition OECD health systems . Health Policy (Amsterdam) , 119 ( 7 ), 860 – 873 . 10.1016/j.health-pol.2015.02.013 PMID: [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sørensen , K. , Pelikan , J. M. , Röthlin , F. , Ganahl , K. , Slonska , Z. , Doyle , G. , Fullam , J. , Kondilis , B. , Agrafiotis , D. , Uiters , E. , Falcon , M. , Mensing , M. , Tchamov , K. , van den Broucke S. , Brand H. , & the HLS-EU Consortium . ( 2015. ). Health literacy in Europe: Comparative results of the European health literacy survey (HLS-EU) . European Journal of Public Health , 25 ( 6 ), 1053 – 1058 . 10.1093/eurpub/ckv043 PMID: [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van der Grient , R. , & Keuchenius , C . ( 2019. ). Health care monitor 2019: Study into switching behaviour with regard to health insurances . https://www.acm.nl/sites/default/files/documents/2019-05/zorg-monitor-2019.pdf [Google Scholar]

- van Winssen , K. P. M. , van Kleef , R. C. , & van de Ven , W. P. M. M. ( 2016. ). The demand for health insurance and behavioural economics . The European Journal of Health Economics , 17 ( 6 ), 653 – 657 . 10.1007/s10198-016-0776-3 PMID: [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zuidhof , P. , Kraal , E. , & Nijhof , E . ( 2019. ). Onderzoek aanvullende verzekeringen Zorgweb [Research supplementary insurance policies Zorgweb] . https://www.zorgweb.nl/assets/onderzoek-aanvullende-verzekering-voor-vws-2019.pdf [Google Scholar]