Abstract

Herein, a method for synthesizing and utilizing DNA dendrons to deliver biomolecules to living cells is reported. Inspired by high-density nucleic acid nanostructures, such as spherical nucleic acids, we hypothesized that small clusters of nucleic acids, in the form of DNA dendrons, could be conjugated to biomolecules and facilitate their cellular uptake. We show that DNA dendrons are internalized by 90% of dendritic cells after just 1 h of treatment, with a >20-fold increase in DNA delivery per cell compared with their linear counterparts. This effect is due to the interaction of the DNA dendrons with scavenger receptor-A on cell surfaces, which results in their rapid endocytosis. Moreover, when conjugated to peptides at a single attachment site, dendrons enhance the cellular delivery and activity of both the model ovalbumin 1 peptide and the therapeutically relevant thymosin alpha 1 peptide. These findings show that high-density, multivalent DNA ligands play a significant role in dictating cellular uptake of biomolecules and consequently will expand the scope of deliverable biomolecules to cells. Indeed, DNA dendrons are poised to become agents for the cellular delivery of many molecular and nanoscale materials.

Deoxyribonucleic acids (DNA), peptides, and proteins are attractive candidates for the development of novel diagnostic probes1 and therapeutics2 because of their chemical, structural, and functional properties. Nevertheless, their uses in this capacity and translation clinically are still greatly limited by their low cellular uptake, arising from their hydrophilicity, charge, and rapid degradation.3-5 Methods have been developed to circumvent these shortcomings and promote uptake, such as the use of lipoplexes,6 cell-penetrating peptides,7,8 and nanoparticle complexes.9-12 While these methods are effective in increasing cellular uptake, they can be cytotoxic and unstable, limiting their applicability in vivo.10,13-15

Spherical nucleic acids (SNAs), nanoparticles with a dense shell of radially oriented oligonucleotides, are a promising class of nanostructures that interact with living matter in markedly different ways from linear strands. Through engagement with type-A scavenger receptors, SNAs exhibit rapid cellular uptake in over 60 different cell types,16 a property stemming from the dense arrangement of oligonucleotides. Furthermore, the DNA shell sterically inhibits degradative proteins, resulting in superior SNA stability in vivo.17,18 The properties arising from the DNA shell are independent of the nanoparticle core employed and translatable across different classes of oligonucleotides. Indeed, gold nanoparticles, polymer vesicles, liposomes, and most recently proteins19-22 have been used as cores functionalized with immunostimulatory DNA, antisense DNA, RNA, and small-interfering RNA.23-25

While SNAs have been utilized as a platform for various probes and therapeutics, in some respects their three-dimensional architectures impose unnecessary limitations by requiring dense isotropic functionalization in order to access these advantageous properties. As a result, small molecules, DNA/RNA, peptides, and small proteins, which have a limited number of conjugation sites, lack reliable and biocompatible methods for cellular delivery. We hypothesized that a structure consisting of one portion of an SNA would be able to engage scavenger receptors in much the same way as the full SNA architecture. To test this hypothesis, we synthesized DNA dendrons, molecularly well-defined clusters of DNA radiating from a single branching point, and functionalized them with nucleic acid and peptide cargo to explore their cell uptake properties.

DNA dendrons have been previously synthesized through two approaches: hybridization-mediated assembly26-32 and solid-phase covalent methods.31,33 Hybridization-based approaches depend on non-covalent interactions, making them susceptible to degradation in biological environments through dehybridization and structural rearrangement.26 In contrast, solid-phase DNA synthesis using phosphoramidite chemistry enables the synthesis of defined, covalently linked structures.33 However, the current state-of-the-art covalent syntheses of DNA dendrons typically exhibit low yields, which are exacerbated by multiple required purification steps. We identified the causes of low yields to be intermolecular steric hindrance, intramolecular steric and electrostatic hindrance, and solid-support–DNA steric hindrance. By systematically addressing these issues, we synthesized DNA dendrons with size, length, and generation control at greater than 10% yield postpurification, an over 20-fold increase compared with previous attempts31 at controlled dendron synthesis. A more in-depth discussion can be found in the Supporting Information (Table S1 and discussion).

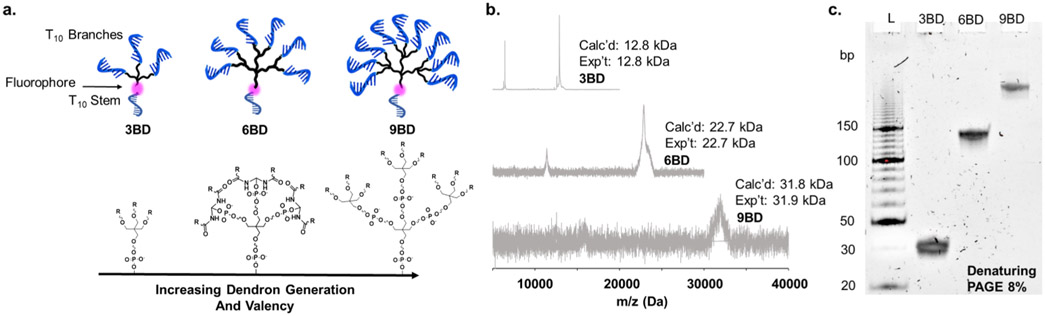

DNA dendrons were synthesized containing either three (3BD), six (6BD), or nine (9BD) branches (Figure 1a). A fluorophore was incorporated between the branched region and the stem to be used as a fluorescent label in in vitro and in vivo studies (vide infra). All of the dendrons were characterized by matrix-assisted laser desorption/ionization time-of-flight mass spectrometry (MALDI-TOF) and denaturing polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (PAGE) to confirm their masses and purities (Figure 1b,c). MALDI-TOF revealed expected mass increments of approximately 10 kDa with increasing dendron valency. Denaturing PAGE showed a single band for each purified dendron and an expected decrease in electrophoretic mobility with increasing branch number. Moreover, through this work, nonstandard phosphoramidites containing functional groups for bioconjugation, such as primary amines, can be introduced on both the stem and branch positions without a decrease in yield.

Figure 1.

DNA dendron design and characterization. (a) DNA dendrons consist of a 10-base oligodeoxynucleotide stem, a branching region producing three, six, or nine total branches, and a 10-base oligonucleotide on each branch. The number of branches can be tuned by changing the branching unit and dendron generation. (b, c) Dendron synthesis and purification were confirmed by MALDI-TOF and denaturing PAGE.

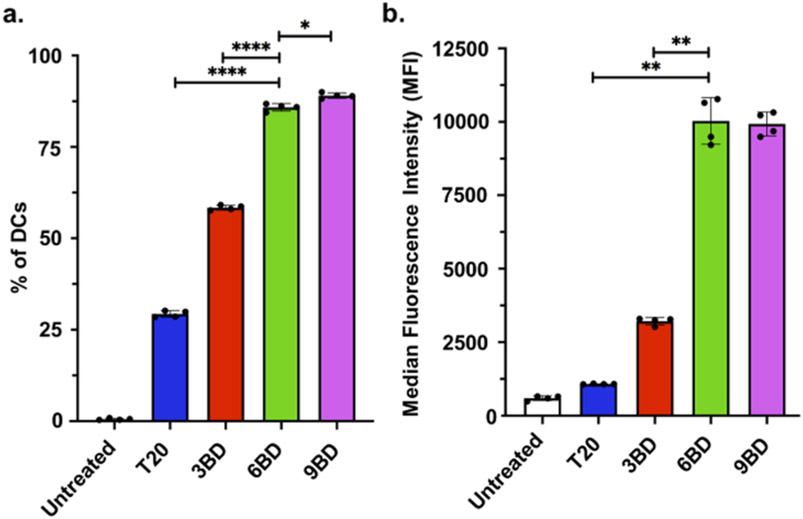

We hypothesized that increasing the DNA dendron valency would lead to higher uptake by cells, facilitated by the increased interaction of the dense DNA branches with scavenger receptor-A on cell surfaces. To test this hypothesis, murine bone-marrow-derived dendritic cells (BMDCs) were treated with 50 nM fluorophore-labeled linear T20 strands or a 3BD, 6BD, or 9BD dendron for 1 h in serum-containing media. Cellular uptake was assessed by measuring the fluorescence frequency and intensity of treated cells via flow cytometry. We observed that the T20 linear strand is taken up by just 29% of DCs (Figure 2a). This amount significantly rises with increasing DNA dendron valency, as 3BD is taken up by approximately 60% of cells and 6BD and 9BD are taken up by about 90% of cells (Figure 2a). To determine the relative amount of DNA taken up per cell, we analyzed the median fluorescence intensity (MFI) of the fluorophore signal in cells positive for DNA. Valency dependence is even more pronounced by this metric. A cluster of three DNA strands (3BD) resulted in a greater than 5-fold increase in MFI compared with the T20 linear control. Moreover, an almost 20-fold increase in MFI was measured for cells treated with 6BD and 9BD compared with the T20 strand (Figure 2b). These experiments show not only that DNA dendrons are taken up by a greater percentage of cells but also that more DNA dendrons are taken up per cell compared with their linear counterparts. Furthermore, this observation indicates that six DNA branches is the minimum valency required to achieve highly efficient (>90%) cellular uptake. Crucially, we observed that the DNA dendrons are not cytotoxic (Figure S1) and that the efficient uptake is a result of the dendron architecture and not solely due to the increase in DNA content (Figure S2). These conclusions were further validated in another cell line, C166 endothelial cells (Figure S3). We confirmed that the dendrons are taken up through scavenger receptor-A-mediated endocytosis, following the same uptake mechanism as for SNAs (Figure S4). Moreover, we observed that DNA dendrons are significantly more resistant to serum nucleases compared with their linear counterparts because their dense DNA clusters sterically prevent enzymatic degradation (Figure S5). Together these findings demonstrate that DNA dendrons exhibit the superior cellular uptake and resistance to nuclease degradation required for therapeutic applications.

Figure 2.

Ex vivo DNA dendron uptake in murine bone-marrow-derived dendritic cells (DCs) compared with a linear control. (a) Frequencies of DNA-positive cells among the DC population show that higher-valency DNA dendrons (6BD and 9BD) are endocytosed by a greater percentage of the population compared with low-valency dendrons (3BD) and the linear control (T20). (b) Median fluorescence intensities (MFIs) of DNA-positive cells indicate not only that DNA dendrons are taken up by more cells but also that more are taken up per cell compared with their linear counterparts. For clarity, only relevant significances against 6BD and 9BD are shown. *, p < 0.05; **, p < 0.01; ****, p < 0.0001.

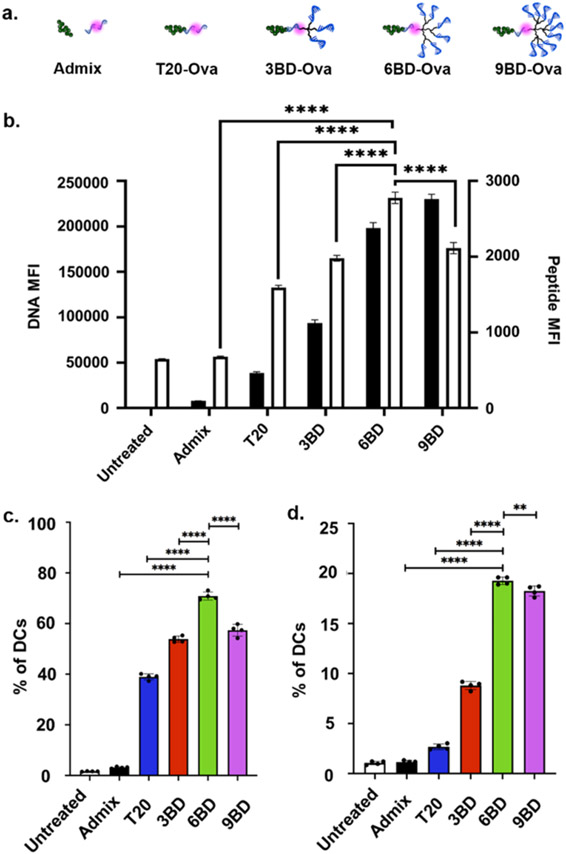

Having established that DNA dendrons are efficiently taken up by cells, we hypothesized that conjugating DNA dendrons to functional biomolecules would induce rapid and effective cellular delivery of those biomolecular cargoes. Specifically, peptides have the potential to be powerful therapeutics because of their vast range of structural and functional properties; however, since they are small amino acid chains with varied charge, dense surface functionalization is difficult and can lead to a loss of peptide function.34 As a result, they are typically delivered as unmodified therapeutics, leaving them prone to rapid degradation and limited cellular uptake.35 The ovalbumin 1 peptide (Ova257–264, designated herein as Ova) was chosen as a model system because it is well-characterized and its cellular processing can be readily measured with commercially available reagents.36 We used a fluorophore-tagged Ova peptide and conjugated it to the dendron through a cysteine residue at the N-terminus via a disulfide exchange reaction utilizing a pyridyl disulfide-containing cross-linker. DNA–Ova conjugates were synthesized with the T20, 3BD, 6BD, and 9BD strands, purified by denaturing PAGE, and characterized by MALDI-TOF (Figures 3a and S6). MALDI-TOF revealed expected mass increases of ~1.5 kDa between DNA and DNA–Ova conjugates, accounting for the added mass of the conjugated Ova peptide.

Figure 3.

Dendron-mediated delivery of Ova. (a) Depiction of DNA–Ova conjugates. (b) The individual MFIs for both the DNA (black) and peptide (white) show significantly greater uptake of both 6BD and 9BD compared with other structures, as determined by flow cytometry. (c) 6BD delivers both DNA and peptide to a greater percentage of cells compared with low-valency dendrons and the admix solution, as determined by flow cytometry, measuring double-positive signals. (d) Measurement of the fluorescence signal of an antibody that recognizes Ova–MHC binding using flow cytometry shows that 6BD and 9BD enable more efficient Ova peptide processing compared with lower-valency conjugates and admix. For clarity, not all significances are shown. **, p < 0.01; ****, p < 0.0001.

We hypothesized that increasing the DNA dendron valency would improve the cellular delivery of the DNA-conjugated Ova peptide, facilitated by the DNA dendron. Thus, we compared the signals of DNA and peptide for a simple mixture (DNA and peptide mixed but not conjugated, termed admix) and the T20, 3BD, 6BD, and 9BD conjugates. By measuring the MFI of cells treated with each sample at a concentration of 50 nM, we determined the extent of uptake of the DNA and peptide per cell. By this metric, we observed that the 6BD and 9BD conjugates are superior to the admix and T20 conjugate, with ~30-fold increases in MFI for both DNA and peptide compared with admix (Figure 3b). Furthermore, assessing cells containing double-positive signals for both DNA and peptide revealed that only 3% of cells treated with the admix solution contained both (Figure 3c). In contrast, with the T20 conjugate, both peptide and DNA are delivered to 38% of the cells, demonstrating the importance of covalent coupling of the two agents to improve codelivery. Importantly, with the use of any of the dendron conjugates, this double-positive signal increases to greater than 50%; indeed, the 6BD conjugate delivers both peptide and DNA to over 70% of the cells (Figure 3c). Crucially, peptide conjugation does not impact the mechanism by which dendrons enter cells (Figure S7). On the basis of literature precedent,37-41 the observed differences in uptake between 6BD–Ova and 9BD–Ova at this time point are likely due to differences in the sizes of the conjugates, which have been shown to play an important role in DC processing of antigens. Overall, these results are a powerful demonstration of the potential of DNA dendrons to deliver biomolecular conjugates to cells.

To investigate whether DNA dendron conjugation affected the cellular processing of the peptide, we measured the frequency at which the Ova peptide binds to a receptor, the major histocompatibility complex (MHC). The MHC is responsible for recognizing immunogenic peptides and, on the basis of those peptide sequences, teaching other immune cells what to target.36 We quantified the percentage of cells that have the Ova peptide bound to MHC using a commercially available antibody and observed that increasing the valency of dendron conjugates significantly increased Ova–MHC complexation. While cells treated with the T20 conjugate have a 2-fold increase in MHC-bound Ova compared with admix, those treated with higher-valency 6BD and 9BD conjugates yield a 15-fold increase in MHC-bound Ova, ultimately displaying the Ova peptide on ca. 20% of the DC population (Figure 3d). This enhancement is due to the dendrons’ ability to induce rapid uptake while simultaneously preventing extracellular peptide degradation. Importantly, these findings validate that dendron conjugation does not impede the cellular processing of the peptide. The Ova peptide requires trafficking to the endoplasmic reticulum in order to be properly processed by the cell, which was confirmed by confocal microscopy (Figure S8). This observation is attributed to the metastability of the disulfide bond connecting the peptide to the dendron, since reducing conditions intracellularly lead to dendron cleavage and release of the peptide for MHC binding. From these results, we conclude that the 6BD and 9BD dendrons are capable of carrying biomolecules, which have been extremely difficult to deliver in the past, into cells and that dendron-delivered peptides are taken up and recognized by the cell for subsequent processing. Furthermore, these DNA dendron–peptide conjugates provide a novel route to develop powerful peptide-based vaccines, as demonstrated by their enhanced uptake and function compared with admix solutions, a common clinical vaccine formulation.42,43

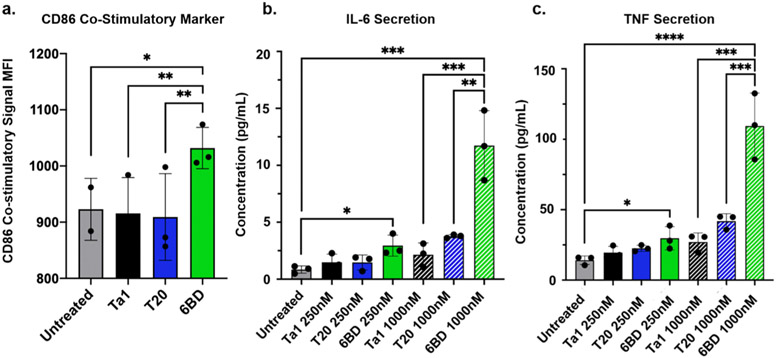

The Ova peptide, however, is a model system. To determine whether comparable improvements in uptake and function are observed when a clinically relevant peptide is delivered, we investigated how dendron-mediated delivery of the thymosin alpha 1 peptide (Ta1) impacts cellular response. Ta1 is a peptide that is naturally produced by the thymus gland and is essential for an active immune response by functioning as an adjuvant and binding to toll-like receptor-9.44 It is clinically used to treat hepatitis, cancer, HIV-AIDS, and COVID-19 because of its vast self-regulating immune cell activation.45-52 Its ability to activate immune cells for cytokine production and stem cell differentiation without causing cytokine storms has led to its widespread use to treat immunocompromised patients.45-54 We assessed whether the dendron can be used to deliver Ta1 more effectively and efficiently such that a more potent downstream therapeutic response is observed compared with unmodified Ta1 peptide, the current clinical formulation. As 6BD conjugates were most effective for the delivery of the model peptide, Ova, we selected this dendron for use in all future studies. Compared with Ta1 on its own and a T20–Ta1 conjugate, DCs treated with the 6BD–Ta1 conjugate expressed significantly higher levels of the costimulatory marker CD86, a result of immune cell activation (Figure 4a). Furthermore, by measuring downstream cytokine secretion, we studied the impact of Ta1 delivery on additional immune cell signaling. We found that the 6BD–Ta1 conjugate significantly outcompeted both the unmodified Ta1 peptide and the T20–Ta1 conjugate at various concentrations in inducing secretion of interleukin 6 (IL-6) and tumor necrosis factor α (TNF-α) (Figure 4b,c), cytokines that are important for widespread immune activation.55,56 Ultimately, this shows that the 6BD dendron is capable of delivering functional, therapeutically relevant peptides more efficiently and effectively than current clinical formulations, resulting in a stronger downstream cellular response. Supported by in vivo pharma-cokinetic and biodistribution studies (Figures S9 and S10), these dendrons hold potential for future clinical applications.

Figure 4.

DNA-dendron-mediated delivery of the clinically relevant peptide Ta1. (a) Enhanced immune cell activation, as evidenced by CD86 costimulatory marker expression, for cells treated with 6BD-Ta1. (b, c) Enhanced downstream effects are observed when Ta1 is delivered as a dendron conjugate, as evidenced by increased secretion of the cytokines interleukin-6 and tumor necrosis factor. Both cytokines are indicative of widespread immune activation. *, p < 0.05; **, p < 0.01; ***, p < 0.001; ****, p < 0.0001.

In conclusion, we have developed a general approach to deliver functional biomolecules into cells utilizing molecularly defined DNA dendrons. Their ease of synthesis and functionalization points to their potential for use as cellular delivery agents for a variety of materials (i.e., small molecules, DNA/RNA, peptides, and proteins). Indeed, DNA dendrons provide a simple, effective, and biocompatible approach to deliver various diagnostic and therapeutic materials to living systems that were previously difficult, if not impossible, to deliver to cells. Therefore, DNA dendrons are poised to have a significant impact on the development of next-generation diagnostic tools, vaccines, and therapeutics.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This material is based upon work supported by the Air Force Office of Scientific Research (Award FA9550-17-1-0348) and the Air Force Research Laboratory (Award FA8650-15-2-5518). The U.S. Government is authorized to reproduce and distribute reprints for Governmental purposes notwithstanding any copyright notation thereon. M.H.T. gratefully acknowledges support from Cancer Nanotechnology Training Grant T32CA186897. K.E.B. gratefully acknowledges support from a Banting Fellowship from the Government of Canada. M.E. was partially supported by the Dr. John N. Nicholson Fellowship. This work made use of the IMSERC MS facility at Northwestern University, which has received support from the Soft and Hybrid Nanotechnology Experimental (SHyNE) Resource (NSF ECCS-2025633), the State of Illinois, and the International Institute for Nanotechnology (IIN). Peptide Synthesis was performed at the Peptide Synthesis Core Facility of the Simpson Querrey Institute at Northwestern University, with special thanks to Dr. Mark Karver, which has current support from the Soft and Hybrid Nanotechnology Experimental (SHyNE) Resource (NSF ECCS-2025633). Some figures were created with BioRender.

Footnotes

The authors declare no competing financial interest.

Supporting Information

The Supporting Information is available free of charge at https://pubs.acs.org/doi/10.1021/jacs.1c07240.

Procedures for DNA syntheses, peptide conjugation, and cell studies; all of the DNA sequences used; and experiments that investigate the interaction of DNA dendrons with cellular environments (PDF)

Contributor Information

Max E. Distler, Department of Chemistry and International Institute for Nanotechnology, Northwestern University, Evanston, Illinois 60208, United States.

Michelle H. Teplensky, Department of Chemistry and International Institute for Nanotechnology, Northwestern University, Evanston, Illinois 60208, United States.

Katherine E. Bujold, Department of Chemistry and International Institute for Nanotechnology, Northwestern University, Evanston, Illinois 60208, United States; Present Address: Department of Chemistry & Chemical Biology, McMaster University, 1280 Main Street West, Hamilton, Ontario L8S 4M1, Canada.

Caroline D. Kusmierz, Department of Chemistry and International Institute for Nanotechnology, Northwestern University, Evanston, Illinois 60208, United States.

Michael Evangelopoulos, Department of Biomedical Engineering and International Institute for Nanotechnology, Northwestern University, Evanston, Illinois 60208, United States.

Chad A. Mirkin, Department of Chemistry, Department of Biomedical Engineering, and International Institute for Nanotechnology, Northwestern University, Evanston, Illinois 60208, United States.

REFERENCES

- (1).Alladin-Mustan BS; Liu Y; Li Y; de Almeida DRQ; Yuzik J; Mendes CF; Gibbs JM Reverse transcription lesion-induced DNA amplification: An instrument-free isothermal method to detect RNA. Anal. Chim. Acta 2021, 1149, 238130–238141. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (2).Ding F; Mou Q; Ma Y; Pan G; Guo Y; Tong G; Choi CHJ; Zhu X; Zhang C A Crosslinked Nucleic Acid Nanogel for Effective siRNA Delivery and Antitumor Therapy. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed 2018, 57, 3064–3068. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (3).Acar H; Ting JM; Srivastava S; LaBelle JL; Tirrell MV Molecular engineering solutions for therapeutic peptide delivery. Chem. Soc. Rev 2017, 46, 6553–6569. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (4).Fu A; Tang R; Hardie J; Farkas ME; Rotello VM Promises and Pitfalls of Intracellular Delivery of Proteins. Bioconjugate Chem. 2014, 25, 1602–1608. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (5).Patil SD; Rhodes DG; Burgess DJ DNA-based therapeutics and DNA delivery systems: A comprehensive review. AAPS J. 2005, 7, E61–E77. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (6).Pal Singh P; Vithalapuram V; Metre S; Kodipyaka R Lipoplex-based therapeutics for effective oligonucleotide delivery: a compendious review. J. Liposome Res 2020, 30, 313–335. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (7).Stewart KM; Horton KL; Kelley SO Cell-penetrating peptides as delivery vehicles for biology and medicine. Org. Biomol. Chem 2008, 6, 2242–2255. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (8).Yousif LF; Stewart KM; Horton KL; Kelley SO Mitochondria-Penetrating Peptides: Sequence Effects and Model Cargo Transport. ChemBioChem 2009, 10, 2081–2088. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (9).Xu ZP; Zeng QH; Lu GQ; Yu AB Inorganic nanoparticles as carriers for efficient cellular delivery. Chem. Eng. Sci 2006, 61, 1027–1040. [Google Scholar]

- (10).McMillan J; Batrakova E; Gendelman HE Cell delivery of therapeutic nanoparticles. Prog. Mol. Biol. Transl. Sci 2011, 104, 563–601. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (11).Wang D; Lu X; Jia F; Tan X; Sun X; Cao X; Wai F; Zhang C; Zhang K Precision Tuning of DNA- and Poly(ethylene glycol)-Based Nanoparticles via Coassembly for Effective Antisense Gene Regulation. Chem. Mater 2017, 29, 9882–9886. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (12).Kohata A; Hashim PK; Okuro K; Aida T Transferrin-Appended Nanocaplet for Transcellular siRNA Delivery into Deep Tissues. J. Am. Chem. Soc 2019, 141, 2862–2866. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (13).Dass CR Cytotoxicity issues pertinent to lipoplex-mediated gene therapy in-vivo. J. Pharm. Pharmacol 2010, 54, 593–601. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (14).Khazanov E; Simberg D; Barenholz Y Lipoplexes prepared from cationic liposomes and mammalian DNA induce CpG-independent, direct cytotoxic effects in cell cultures and in mice. J. Gene Med 2006, 8, 998–1007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (15).Kristensen M; Birch D; Mørck Nielsen H Applications and Challenges for Use of Cell-Penetrating Peptides as Delivery Vectors for Peptide and Protein Cargos. Int. J. Mol. Sci 2016, 17, 185–202. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (16).Choi CH; Hao L; Narayan SP; Auyeung E; Mirkin CA Mechanism for the endocytosis of spherical nucleic acid nanoparticle conjugates. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A 2013, 110, 7625–7630. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (17).Seferos DS; Prigodich AE; Giljohann DA; Patel PC; Mirkin CA Polyvalent DNA Nanoparticle Conjugates Stabilize Nucleic Acids. Nano Lett. 2009, 9, 308–311. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (18).Kusmierz CD; Bujold KE; Callmann CE; Mirkin CA Defining the Design Parameters for in Vivo Enzyme Delivery Through Protein Spherical Nucleic Acids. ACS Cent. Sci 2020, 6, 815–822. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (19).Kapadia CH; Melamed JR; Day ES Spherical Nucleic Acid Nanoparticles: Therapeutic Potential. BioDrugs 2018, 32, 297–309. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (20).Banga RJ; Chernyak N; Narayan SP; Nguyen ST; Mirkin CA Liposomal spherical nucleic acids. J. Am. Chem. Soc 2014, 136, 9866–9869. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (21).Banga RJ; Meckes B; Narayan SP; Sprangers AJ; Nguyen ST; Mirkin CA Cross-Linked Micellar Spherical Nucleic Acids from Thermoresponsive Templates. J. Am. Chem. Soc 2017, 139, 4278–4281. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (22).Brodin JD; Sprangers AJ; McMillan JR; Mirkin CA DNA-Mediated Cellular Delivery of Functional Enzymes. J. Am. Chem. Soc 2015, 137, 14838–14841. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (23).Jensen SA; Day ES; Ko CH; Hurley LA; Luciano JP; Kouri FM; Merkel TJ; Luthi AJ; Patel PC; Cutler JI; Daniel WL; Scott AW; Rotz MW; Meade TJ; Giljohann DA; Mirkin CA; Stegh AH Spherical Nucleic Acid Nanoparticle Conjugates as an RNAi-Based Therapy for Glioblastoma. Sci. Transl. Med 2013, 5, 209ra152. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (24).Yamankurt G; Stawicki RJ; Posadas DM; Nguyen JQ; Carthew RW; Mirkin CA The effector mechanism of siRNA spherical nucleic acids. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A 2020, 117, 1312–1320. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (25).Radovic-Moreno AF; Chernyak N; Mader CC; Nallagatla S; Kang RS; Hao L; Walker DA; Halo TL; Merkel TJ; Rische CH; Anantatmula S; Burkhart M; Mirkin CA; Gryaznov SM Immunomodulatory spherical nucleic acids. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A 2015, 112, 3892–3897. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (26).Li Y; Tseng YD; Kwon SY; d’Espaux L; Bunch JS; McEuen PL; Luo D Controlled assembly of dendrimer-like DNA. Nat. Mater 2004, 3, 38–42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (27).Evanko D Hybridization chain reaction. Nat. Methods 2004, 1, 186–187. [Google Scholar]

- (28).Qu Y; Yang J; Zhan P; Liu S; Zhang K; Jiang Q; Li C; Ding B Self-Assembled DNA Dendrimer Nanoparticle for Efficient Delivery of Immunostimulatory CpG Motifs. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2017, 9, 20324–20329. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (29).Zhao Y; Hu S; Wang H; Yu K; Guan Y; Liu X; Li N; Liu F DNA Dendrimer-Streptavidin Nanocomplex: an Efficient Signal Amplifier for Construction of Biosensing Platforms. Anal. Chem 2017, 89, 6907–6914. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (30).Li Y; Tseng YD; Kwon SY; D’Espaux L; Bunch JS; McEuen PL; Luo D Controlled assembly of dendrimer-like DNA. Nat. Mater 2004, 3, 38–42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (31).Shchepinov MS; Udalova IA; Bridgman AJ; Southern EM Oligonucleotide dendrimers: synthesis and use as polylabelled DNA probes. Nucleic Acids Res. 1997, 25, 4447–4454. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (32).Meng H-M; Zhang X; Lv Y; Zhao Z; Wang N-N; Fu T; Fan H; Liang H; Qiu L; Zhu G; Tan W DNA Dendrimer: An Efficient Nanocarrier of Functional Nucleic Acids for Intracellular Molecular Sensing. ACS Nano 2014, 8, 6171–6181. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (33).Caruthers MH The Chemical Synthesis of DNA/RNA: Our Gift to Science. J. Biol. Chem 2013, 288, 1420–1427. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (34).Veronese FM Peptide and protein PEGylation: a review of problems and solutions. Biomaterials 2001, 22, 405–417. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (35).Bruno BJ; Miller GD; Lim CS Basics and recent advances in peptide and protein drug delivery. Ther. Delivery 2013, 4, 1443–1467. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (36).Kukutsch NA; Roßner S; Austyn JM; Schuler G; Lutz MB Formation and Kinetics of MHC Class I-Ovalbumin Peptide Complexes on Immature and Mature Murine Dendritic Cells. J. Invest. Dermatol 2000, 115, 449–453. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (37).Falo LD; Kovacsovics-Bankowski M; Thompson K; Rock KL Targeting antigen into the phagocytic pathway in vivo induces protective tumour immunity. Nat. Med 1995, 1, 649–653. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (38).Fifis T; Gamvrellis A; Crimeen-Irwin B; Pietersz GA; Li J; Mottram PL; McKenzie IFC; Plebanski M Size-Dependent Immunogenicity: Therapeutic and Protective Properties of Nano-Vaccines against Tumors. J. Immunol 2004, 173, 3148. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (39).Kovacsovics-Bankowski M; Clark K; Benacerraf B; Rock KL Efficient major histocompatibility complex class I presentation of exogenous antigen upon phagocytosis by macrophages. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A 1993, 90, 4942–4946. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (40).Reddy ST; Rehor A; Schmoekel HG; Hubbell JA; Swartz MA In vivo targeting of dendritic cells in lymph nodes with poly(propylene sulfide) nanoparticles. J. Controlled Release 2006, 112, 26–34. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (41).Tran KK; Shen H The role of phagosomal pH on the size-dependent efficiency of cross-presentation by dendritic cells. Biomaterials 2009, 30, 1356–1362. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (42).Wang S; Qin L; Yamankurt G; Skakuj K; Huang Z; Chen P-C; Dominguez D; Lee A; Zhang B; Mirkin CA Rational vaccinology with spherical nucleic acids. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A 2019, 116, 10473–10481. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (43).Radovic-Moreno AF; Chernyak N; Mader CC; Nallagatla S; Kang RS; Hao L; Walker DA; Halo TL; Merkel TJ; Rische CH; Anantatmula S; Burkhart M; Mirkin CA; Gryaznov SM Immunomodulatory spherical nucleic acids. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A 2015, 112, 3892–3897. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (44).Tuthill CW; King RS Thymosin Apha 1—A Peptide Immune Modulator with a Broad Range of Clinical Applications. J. Clin. Exp. Pharmacol 2013, 3, 1000133. [Google Scholar]

- (45).Wu X; Jia J; You H Thymosin alpha-1 treatment in chronic hepatitis B. Expert Opin. Biol. Ther 2015, 15, 129–132. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (46).Li J; Liu CH; Wang FS Thymosin alpha 1: Biological activities, applications and genetic engineering production. Peptides 2010, 31, 2151–2158. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (47).Sherman KE Thymosin α 1 for treatment of hepatitis C virus: promise and proof. Ann. N. Y. Acad. Sci 2010, 1194, 136–140. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (48).Chadwick D; Pido-Lopez J; Pires A; Imami N; Gotch F; Villacian JS; Ravindran S; Paton NI A pilot study of the safety and efficacy of thymosin alpha 1 in augmenting immune reconstitution in HIV-infected patients with low CD4 counts taking highly active antiretroviral therapy. Clin. Exp. Immunol 2003, 134, 477–481. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (49).Matteucci C; Grelli S; Balestrieri E; Minutolo A; Argaw-Denboba A; Macchi B; Sinibaldi-Vallebona P; Perno CF; Mastino A; Garaci E Thymosin alpha 1 and HIV-1: recent advances and future perspectives. Future Microbiol. 2017, 12, 141–155. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (50).Costantini C; Bellet MM; Pariano M; Renga G; Stincardini C; Goldstein AL; Garaci E; Romani L A Reappraisal of Thymosin Alpha1 in Cancer Therapy. Front. Oncol 2019, 9, 873. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (51).Wu M; Ji J-J; Zhong L; Shao Z-Y; Xie Q-F; Liu Z-Y; Wang C-L; Su L; Feng Y-W; Liu Z-F; Yao Y-M Thymosin α1 therapy in critically ill patients with COVID-19: A multicenter retrospective cohort study. Int. Immunopharmacol 2020, 88, 106873–106873. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (52).Liu Y; Pan Y; Hu Z; Wu M; Wang C; Feng Z; Mao C; Tan Y; Liu Y; Chen L; Li M; Wang G; Yuan Z; Diao B; Wu Y; Chen Y Thymosin Alpha 1 Reduces the Mortality of Severe Coronavirus Disease 2019 by Restoration of Lymphocytopenia and Reversion of Exhausted T Cells. Clin. Infect. Dis 2020, 71, 2150–2157. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (53).Ancell CD; Phipps J; Young L Thymosin alpha-1. Am. J. Health-Syst. Pharm 2001, 58, 879–885. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (54).King R; Tuthill C Immune Modulation with Thymosin Alpha 1 Treatment. Vitam. Horm 2016, 102, 151–178. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (55).Hirano T; Kishimoto T Interleukin-6. In Peptide Growth Factors and Their Receptors I; Sporn MB, Roberts AB, Eds.; Springer: Berlin, 1990; pp 633–665. [Google Scholar]

- (56).Chu W-M Tumor necrosis factor. Cancer Lett. 2013, 328, 222–225. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.