Abstract

We examined the patterns of strain relatedness among pathogenic yeasts from within and among groups of women to determine whether there were significant associations between genotype and host condition or body site. A total of 80 yeast strains were isolated, identified, and genotyped from 49 female volunteers, who were placed in three groups: (i) 19 women with AIDS, (ii) 11 pregnant women without human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) infection, and (iii) 19 women who were neither pregnant nor infected with HIV. Seven yeast species were recovered, including 59 isolates of Candida albicans, 9 isolates of Candida parapsilosis, 5 isolates of Candida krusei, 3 isolates of Candida glabrata, 2 isolates of Saccharomyces cerevisiae, and 1 isolate each of Candida tropicalis and Candida lusitaniae. Seventy unique genotypes were identified by PCR fingerprinting with the M13 core sequence and by random amplified polymorphic DNA analysis. Of the nine shared genotypes, isolates from three different hosts were of one genotype and pairs of strains from different body sites of the same host shared each of the other eight genotypes. Genetic similarities among groups of strains were calculated and compared. We found no significant difference in the patterns of relatedness of strains from the three body sites (oral cavity, vagina, and rectum), regardless of host conditions. The yeast microflora of all three host groups had similar species and genotypic diversities. Furthermore, a single host can be colonized with multiple species or multiple genotypes of the same species at the same or different body sites, indicating dynamic processes of yeast colonization on women.

Opportunistic yeast pathogens are common residents of the mucosal surfaces of the human mouth, gastrointestinal tract, and genitourinary system (15). In recent years, the increases in the human population of infection with human immunodeficiency virus (HIV), organ transplantation, and chemotherapy have dramatically increased the incidence of candidiasis (4, 10, 16, 17, 20). The predominant causal agent of candidiasis is Candida albicans (4, 10, 16, 17, 20). It is often assumed that most cases of candidiasis originate from the commensal strain inhabiting the vaginal canal, oral cavity, or gastrointestinal tract prior to infection (7, 13, 18, 25, 31). However, only limited population genetic surveys support this concept (3, 6, 9, 17). In contrast, there is evidence of reduced genetic diversity among samples of C. albicans from the oral cavities of HIV-infected patients, suggesting the possibility that a commensal strain(s) is replaced by genetically more uniform strains before the inception of oral candidiasis in immunocompromised patients (1, 4, 22, 33, 34). Furthermore, an analysis of strains of C. albicans from various body sites of healthy women suggested that different body sites may select for certain genotypes (27). Other types of associations between genotypes and special host or ecological conditions have also been proposed (28).

Whether strains are replaced before the onset of candidiasis has significant implications for treatment and preventive strategies. For example, if candidiasis is caused by the host's original commensal strain(s), knowledge of the yeast microflora of high-risk patients prior to the manifestation of candidiasis (e.g., susceptibility to different antifungal drugs) could lead to improved strategies for prophylaxis and treatment. Conversely, if commensal strains are frequently replaced by certain genotypes, then identifying the routes of transmission of these potentially more virulent genotypes could lead to measures that limit their spread. These two hypotheses offer different predictions for populations of C. albicans. The “replacement hypothesis” predicts a significantly lower degree of genetic diversity and a higher degree of genetic similarity among strains associated with specific body sites and/or certain types of hosts. In contrast, the “persistent hypothesis” would predict that strains from these sources would display comparable levels of genetic diversity. Most previous studies either used limited types of samples (1, 12, 22, 23) or lacked appropriate controls for confounding factors such as sex, geographic origin, body site, or host condition (1, 3, 6, 9, 22, 23, 28, 33).

Advances in molecular biology in the last two decades have allowed the development of rapid molecular genotyping techniques for clinical and epidemiological analyses (3, 5, 6, 14, 21, 24, 28, 33). Among the current molecular techniques for the genotyping of yeast strains, PCR fingerprinting and random amplified polymorphic DNA (RAPD) analysis, are in wide use. Both genotyping methods have high discriminatory powers and reproducibilities; they require little starting material and are rapid and simple to perform (14).

The goal of this study was to use PCR fingerprinting and RAPD analysis to examine concurrently the roles of host condition and body site in the patterns of yeast genetic diversity among women from a single geographic area. Specifically, we were interested in the contributions of two commonly recognized factors associated with candidiasis in women: HIV infection status (4, 17) and pregnancy (15). We were particularly interested in determining whether isolates from a specific body site or host group might be genetically more similar to each other than to isolates from a different body site or host group.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Strain collection.

Female volunteers (ages 18 years and older) were recruited from among outpatients scheduled to undergo a pelvic examination as part of their routine care in the Obstetrics/Gynecology Clinic and the Adult Infectious Disease Clinic of the Duke University Medical Center. Three host groups were considered: women with AIDS and oral candidiasis (no one in this group was pregnant at the time of sampling; therefore, this group is called the HIV-positive and nonpregnant [HIV+, NP] group), women who were at least 3 months pregnant and who were not infected with HIV (HIV−, P group), and healthy individuals who were neither pregnant nor infected with HIV (HIV−, NP group). Swabs were taken from the vagina, rectum, and oral cavity of each volunteer and were cultured on Inhibitory Mold Agar (Difco, Detroit, Mich.) for yeast isolation. Morphologically distinct yeast colonies from each culture were transferred and stored on Sabouraud glucose agar slants for species identification and subsequent DNA fingerprinting. Yeast species were identified by the germ tube test and with API 20C identification kits (BioMerieux-Vitek). Growth at 45°C on Sabouraud glucose agar was used to distinguish between Candida albicans and Candida dubliniensis.

Strain typing.

Genomic DNA was isolated from each isolate by a previously described protocol (21) and was stored at −20°C. For PCR fingerprinting, the M13 phage core sequence (5′-GAGGGTGGCGGTTCT-3′) and the oligonucleotide 5′-AGTCAGCCAC-3′ (primer PA03; Operon Technologies) were used as single primers. Amplifications were performed in volumes of 25 μl containing 10 ng of genomic DNA, 10 mM Tris-HCl (pH 8.3), 50 mM KCl, 1.5 mM MgCl2, dATP, dCTP, dTTP, and dGTP each at a concentration of 0.2 mM, 3 mM magnesium acetate, 10 ng of primer, and 1.5 U of AmpliTaq DNA polymerase. For primer M13, the PCR was performed in a Perkin-Elmer thermal cycler (model 480) with an initial denaturation of 97°C for 3 min, followed by 40 cycles of 20 s at 93°C, 60 s at 50°C, and 20 s at 72°C and a final cycle of 5 min at 72°C. For primer PA03, the PCR was performed with an initial cycle of 97°C for 3 min, followed by 45 cycles of 60 s at 93°C, 60 s at 36°C, and 120 s at 72°C and a final cycle of 5 min at 72°C.

Amplification products were separated by electrophoresis in 1.5% agarose gels in 1× TAE (Tris-acetate-EDTA) buffer for 13 h at 2 V/cm. Amplification products were detected by staining with ethidium bromide (0.5 μg/ml) and were visualized under UV light. The electrophoretic bands were sized and scored manually. For all isolates, each DNA fragment was scored as present or absent. The intensities of the PCR fragments were not considered, as the PCR process was known to generate bands with variable intensities (14). A total of 129 strains were isolated and genotyped. However, in most instances, the majority of isolates from the same body site of each patient had identical PCR fingerprinting profiles with both primers. Therefore, only strains with a distinct genotype(s) from each body site for each patient were included in the analysis. A total of 80 isolates were compared.

Data analysis.

The yeast recovery rate was calculated for each body site of the three host groups. Statistical significance between different patient types for the same body sites and between different body sites of the same patient type were calculated on the basis of a two-by-two chi-square table test (8, 26). When the expected count of the lowest cell in the chi-square test was less than five, Fisher's exact test was applied (26).

For simple comparisons of the distribution of species and genotypes among host types and body sites, we used two measures of diversity. One was the species diversity, which is calculated as 1 − Σps2, where ps represents the frequency of a particular species (19). The species diversity ranges from a minimum of 0, when all isolates are of the same species, to a maximum of 1, when every isolate is a different species. The statistical significance of the difference in species diversities among samples was compared by Fisher's exact test (26). The other test of diversity was the genotypic diversity, which is calculated as 1/Σpg2, where pg represents the frequency of a unique genotype (29, 30). Genotypic diversity has a minimum value of 1 and a maximum value of N, where N is the sample size. The statistical significance of the difference in genotypic diversities among samples was compared by the t test (2).

Similarity coefficients based on the DNA fingerprinting patterns among all isolates were calculated as the ratio of matches over the total number of bands scored (26). The within- and between-group similarities were calculated as the arithmetic mean of all pairwise distances. Student's t test was used to compare genetic similarities between different groups of isolates (26). For each comparison, we analyzed two different data sets: one that included all isolates and the other that consisted only of C. albicans.

A phenogram showing the similarities of all yeast isolates was generated by the unweighted pair group method with arithmetic mean (UPGMA phenogram) on the basis of the pairwise similarity coefficient matrix (8). The statistical package PAUP4d64 (31) was used to calculate the similarity coefficients and to generate the UPGMA phenogram.

RESULTS

Rate of yeast recovery.

Yeasts were recovered from at least one of the three body sites of all 49 women (Table 1). The rate of yeast recovery differed somewhat among host groups and body sites (Table 2). For example, yeast recovery rates were higher from oral and rectal swabs (63% from both body sites) than from vaginal swabs (42%) for patients with AIDS. The recovery rate from vaginal swabs (73%) was highest for the group that included HIV-negative pregnant women. However, none of these differences were statistically significant either between host groups or between body sites within a host group at a P value of <0.05. The biggest difference in yeast recovery rate was from vaginal swabs between HIV-infected (42%) and HIV-free but pregnant women (73%). The chi-square value between this pairwise comparison was 2.311 (degrees of freedom = 1; P > 0.1).

TABLE 1.

Strains of yeasts isolated and analyzed

| Volunteer no. | HIV statusa | Pregnancy statusb | Body site | No. of strains analyzedc | Species | Strain designationd | Volunteer no. | HIV statusa | Pregnancy statusb | Body site | No. of strains analyzedc | Species | Strain designationd | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 01 | − | Y | Oral cavity | 1 | C. albicans | 01o−y | ||||||||

| 02 | + | N | Oral cavity | 1 | C. albicans | 02o+ne | ||||||||

| 03 | + | N | Vagina | 1 | C. albicans | 03v+n | ||||||||

| Rectum | 1 | C. albicans | 03r+n | |||||||||||

| 04 | − | N | Oral cavity | 1 | C. albicans | 04o−n | ||||||||

| Vagina | 1 | C. albicans | 04v−n | |||||||||||

| Rectum | 1 | C. albicans | 04r−n | |||||||||||

| 05 | − | N | Oral cavity | 1 | C. albicans | 05o−n | ||||||||

| Vagina | 1 | C. krusei | 05v−n1 | |||||||||||

| Vagina | 2 | C. krusei | 05v−n2 | |||||||||||

| Rectum | 1 | C. krusei | 05r−n | |||||||||||

| 06 | − | N | Oral cavity | 1 | C. albicans | 06o−n | ||||||||

| 07 | − | Y | Vagina | 1 | C. albicans | 07v−y1 | ||||||||

| Vagina | 2 | C. albicans | 07v−y2 | |||||||||||

| 08 | + | N | Oral cavity | 1 | C. albicans | 08o+n | ||||||||

| Vagina | 1 | C. albicans | 08v+n | |||||||||||

| 09 | + | N | Oral cavity | 1 | C. albicans | 09o+n | ||||||||

| 10 | + | N | Oral cavity | 1 | C. parapsilosis | 10o+n | ||||||||

| 11 | − | Y | Oral cavity | 1 | C. albicans | 11o+n | ||||||||

| 12 | + | N | Vagina | 1 | C. parapsilosis | 12v+n | ||||||||

| Rectum | 1 | C. albicans | 12r+n | |||||||||||

| 13 | − | Y | Rectum | 1 | C. parapsilosis | 13r−y | ||||||||

| 14 | − | N | Oral cavity | 1 | C. albicans | 14o−n | ||||||||

| Vagina | 1 | C. albicans | 14v−n | |||||||||||

| 15 | − | Y | Oral cavity | 1 | C. albicans | 15o−y | ||||||||

| Vagina | 1 | C. parapsilosis | 15v−y | |||||||||||

| Rectum | 1 | C. parapsilosis | 15r−y | |||||||||||

| 16 | − | N | Rectum | 1 | C. parapsilosis | 16r−n | ||||||||

| 17 | − | N | Oral cavity | 1 | C. albicans | 17o−n | ||||||||

| 18 | − | N | Oral cavity | 1 | C. albicans | 18o−n | ||||||||

| 19 | + | N | Oral cavity | 1 | C. albicans | 19o+n | ||||||||

| 20 | + | N | Rectum | 1 | C. albicans | 20r+n | ||||||||

| 21 | − | N | Vagina | 1 | C. albicans | 21v−n | ||||||||

| Rectum | 1 | C. albicans | 21r−n | |||||||||||

| 22 | − | N | Vagina | 1 | C. albicans | 22v−n | ||||||||

| 23 | − | Y | Oral cavity | 1 | C. albicans | 23o−y | ||||||||

| Vagina | 1 | C. albicans | 23v−n | |||||||||||

| Rectum | 1 | C. albicans | 23r−n | |||||||||||

| 24 | − | N | Vagina | 1 | C. albicans | 24v−n | ||||||||

| Rectum | 1 | C. albicans | 24r−n |

| 25 | − | N | Oral cavity | 1 | C. albicans | 25o−n |

| Vagina | 1 | C. tropicalis | 25v−n | |||

| 26 | − | Y | Vagina | 1 | C. parapsilosis | 26v−y |

| 27 | + | N | Rectum | 1 | C. albicans | 27r+n |

| 28 | + | N | Oral cavity | 1 | C. albicans | 28o+n |

| Rectum | 1 | C. albicans | 28r+n | |||

| 29 | + | N | Oral cavity | 1 | C. albicans | 29o+n |

| Vagina | 1 | C. albicans | 29v+n | |||

| Rectum | 1 | C. albicans | 29r+n | |||

| 30 | − | Y | Oral cavity | 1 | C. albicans | 30o−y |

| Vagina | 1 | C. glabrata | 30v−y | |||

| Rectum | 1 | C. glabrata | 30r−y | |||

| 31 | − | Y | Oral cavity | 1 | C. albicans | 31o−y |

| 32 | − | Y | Vagina | 1 | C. albicans | 32v−y |

| 33 | − | Y | Vagina | 1 | C. albicans | 33v−y |

| Rectum | 1 | C. albicans | 33r−y | |||

| 34 | − | N | Rectum | 1 | C. albicans | 34r−n |

| 35 | − | N | Rectum | 1 | C. krusei | 35r−n |

| 36 | − | N | Oral cavity | 1 | C. albicans | 36o−n |

| 37 | − | N | Rectum | 1 | S. cerevisiae | 37r−n |

| 38 | − | N | Vagina | 1 | C. albicans | 38v−n |

| 39 | + | N | Oral cavity | 1 | C. albicans | 39o+n |

| Rectum | 1 | C. albicans | 39r+n | |||

| 40 | + | N | Oral cavity | 1 | C. krusei | 40o+n |

| 41 | + | N | Vagina | 1 | C. albicans | 41v+n |

| Rectum | 1 | C. albicans | 41r+n1 | |||

| Rectum | 2 | C. glabrata | 41r+n2 | |||

| 42 | + | N | Vagina | 1 | C. albicans | 42v+n1 |

| Vagina | 2 | C. parapsilosis | 42v+n2 | |||

| Rectum | 1 | C. parapsilosis | 42r+n | |||

| 43 | − | N | Oral cavity | 1 | C. albicans | 43o−n |

| 44 | + | N | Oral cavity | 1 | C. albicans | 44o+n |

| 45 | + | N | Rectum | 1 | C. albicans | 45r+n |

| 46 | + | N | Oral cavity | 1 | C. albicans | 46o+n |

| 47 | + | N | Oral cavity | 1 | C. albicans | 47o+n |

| Vagina | 1 | C. albicans | 47v+n | |||

| Rectum | 1 | C. albicans | 47r+n | |||

| 48 | − | N | Oral cavity | 1 | C. albicans | 48o−n1 |

| Oral cavity | 2 | S. cerevisiae | 48o−n2 | |||

| 49 | − | N | Vagina | 1 | C. lusitaniae | 49v−n |

+, HIV carrier; −, HIV noncarrier.

Y, pregnant; N, not pregnant.

1, one strain was analyzed; 2, a second strain was analyzed.

The first two digits refer to the host number, the first letter following the two digits refers to the body site (o, oral; v, vaginal; and r, rectal), the plus or minus sign refers to HIV infection status, the next letter refers to pregnancy status (y, pregnant; n, not pregnant), and the last number, where applicable, is added when two isolates from the same body site were analyzed.

Underlined strains were associated with clinical manifestation of candidiasis.

TABLE 2.

Yeasts isolated from each body site from each group of women

| HIV status | Pregnancy status | No. of women | Species (no. of isolates)/yeast recovery rate (%) from the following body sitea:

|

||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Oral cavity | Vagina | Rectum | |||

| Positive | No | 19 | C. albicans (10), C. parapsilosis (1), C. krusei (1)/63 | C. albicans (6), C. parapsilosis (2)/42 | C. albicans (10), C. parapsilosis (1), C. glabrata (1)/63 |

| Negative | No | 19 | C. albicans (10), S. cerevisiae (1)/58 | C. albicans (6), C. tropicalis (1), C. lusitaniae (1), C. krusei (2)/53 | C. albicans (4), C. parapsilosis (1), S. cerevisiae (1), C. krusei (2)/42 |

| Negative | Yes | 11 | C. albicans (6)/55 | C. albicans (5), C. parapsilosis (2), C. glabrata (1)/73 | C. albicans (2), C. parapsilosis (2), C. glabrata (1)/45 |

None of the differences in yeast recovery rate was statistically significant between any two treatment groups, with all P values being >0.1.

Species distribution and species diversity.

Table 2 summarizes the number of isolates of each species isolated from each host group and body site. Species diversities for each group of women and body site are presented in Table 3. Overall, 73.8% of all isolates (n = 80) were C. albicans, 11.2% were Candida parapsilosis, 6.3% were Candida krusei, 3.7% were Candida glabrata, 2.5% were Saccharomyces cerevisiae, and 1.2% each were Candida tropicalis and Candida lusitaniae. At all three body sites, C. albicans was the most common yeast species (Table 2), and in all three host groups, oral swabs had lower species diversity than either vaginal or rectal swabs (Table 3). However, these differences were not statistically significant (by Fisher's exact test, P > 0.1).

TABLE 3.

Species and genotypic diversities among strains by host group and body site

| Host group | Body site | No. of samples | Species diversitya | Genotypic diversityb |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| HIV+, NP | Oral cavity | 12 | 0.292 | 12 |

| Vagina | 8 | 0.375 | 8 | |

| Rectum | 12 | 0.292 | 12 | |

| All combined | 32 | 0.323 | 24.381 | |

| HIV−, NP | Oral cavity | 11 | 0.165 | 11 |

| Vagina | 10 | 0.580 | 10 | |

| Rectum | 8 | 0.656 | 8 | |

| All combined | 29 | 0.497 | 20.512 | |

| HIV−, P | Oral cavity | 6 | 0 | 6 |

| Vagina | 8 | 0.531 | 8 | |

| Rectum | 5 | 0.640 | 5 | |

| All combined | 19 | 0.476 | 17.190 |

Species diversity is calculated as 1 − Σps2, where ps represents the frequency of a particular species (19). The species diversity ranges from a minimum of 0, when all isolates are of the same species, to a maximum of 1, when every isolate is a different species.

Markers and species identification.

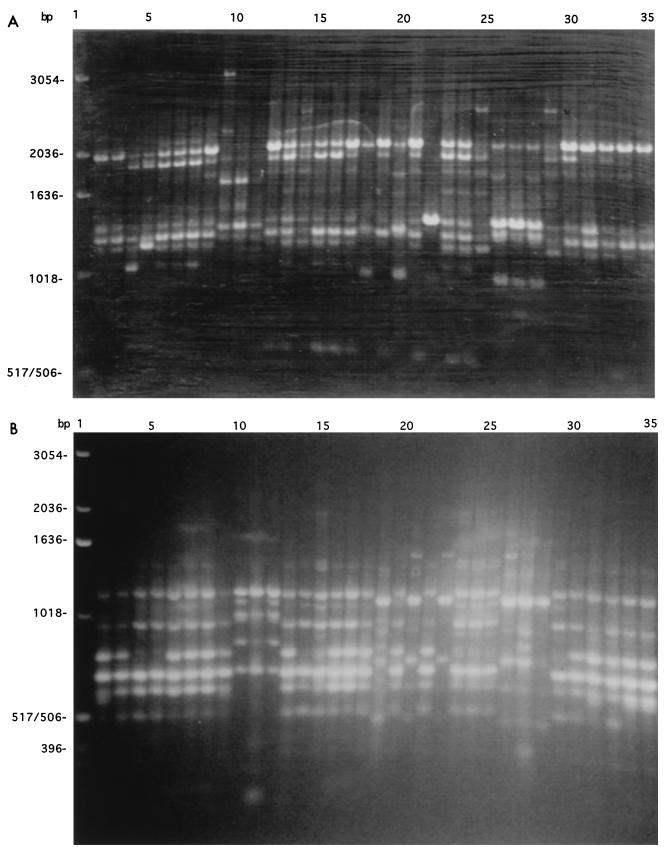

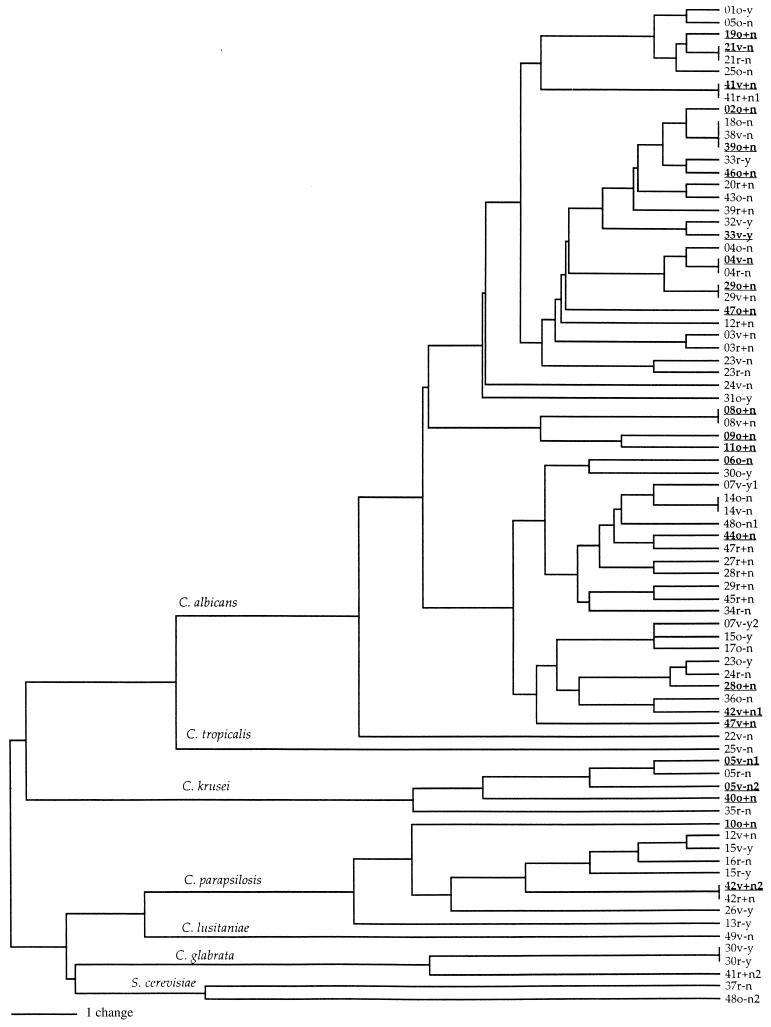

For the set of 80 isolates, a total of 51 polymorphic PCR fragments of different sizes were detected and scored; 29 fragments were generated with the primer M13 core sequence and 22 were generated with primer PA03. A representative picture of the PCR products from each of the primers is presented in Fig. 1. The genetic similarity among all isolates is presented in Fig. 2. This UPGMA phenogram of PCR fingerprints shows the grouping of isolates from each species identified on the basis of morphological and biochemical markers. All 59 isolates with germ tubes and biochemical profiles typical of that for C. albicans were clustered together on the phenogram (Fig. 2). Similarly, multiple isolates of each of four other species, C. parapsilosis, C. glabrata, S. cerevisiae, and C. krusei, grouped together.

FIG. 1.

Examples of electrophoretic separation of PCR fingerprints obtained by amplifying genomic DNA from 34 strains of yeasts isolated in this study by using the M13 core sequence (5′-GAGGGTGGCCGGTTCT-3′) (A) and PA03 (5′-AGTCAGCCAC-3′) as single primers. Lanes: 1, 1-kb ladder from GIBCO-BRL; 2 to 35, strains in the order listed in Table 1 (from 01o−y to 21r−n).

FIG. 2.

UPGMA phenogram of yeast strains calculated from the DNA fingerprinting patterns obtained with the primers M13 core sequence and PA03. Strain designations are described in Table 1 (footnote d). Species identifications are based on those obtained with API 20C kits and are shown on respective basal branches. Underlined strains were associated with clinical symptoms of candidiasis. There is no significant genetic clustering of strains on the basis of host type, disease symptom, or body site.

Genotypic diversity.

A total of 70 unique genotypes were found among the 80 isolates. One genotype was shared by three isolates, each from a different host (isolates 18o−n, 38v−n, and 39o+n in Table 1 and Fig. 2). Eight other genotypes were shared by two isolates each; each pair came from different body sites of the same host (Fig. 2). The genotypic diversity at each body site and for each group of women is presented in Table 3. None of the pairwise comparisons of genotypic diversities between samples was significant at a P value of <0.05, regardless of body site or host group.

Similarity of strains within a host.

Among the 49 volunteers, yeasts were isolated from all three body sites of 7 women (volunteers 04, 05, 15, 23, 29, 30, and 47), from two body sites of 12 women (volunteers 03, 08, 12, 14, 21, 24, 25, 28, 33, 39, 41, and 42), and from one body site of the remaining 30 women (Table 3).

For none of the seven women who harbored isolates at each site were the isolates at all three body sites of the same genotype (Tables 4 and 5; Fig. 2). The most closely related strains from the three different body sites of a single woman were those from volunteer 04; her three strains of C. albicans clustered together on the UPGMA phenogram. For six of these seven women (volunteers 04, 05, 15, 23, 30, and 47), vaginal and rectal isolates were more similar to each other than either was to the oral isolate (Table 5). The mouth and vagina of volunteer 29 were colonized with strains with identical genotypes, and these isolates differed from her rectal isolate (Table 5; Fig. 2). Of the 12 women colonized with isolates from two body sites, the pairs of isolates from 3 women (volunteers 08, 14, and 41) had identical genotypes; for the other nine women, the species were either different or were different genotypes of the same species (Table 4; Fig. 2).

TABLE 4.

Similarity between pairs of strains from different anatomical locations of the same individual

| Location | Host group | Volunteer no. | Strain pair | Similarity coefficient | Mean ± SD similarity coefficient |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Oral cavity-vagina | 0.77897 ± 0.18911 (0.92157 ± 0.11829)a | ||||

| HIV+, NP | 08 | 08o+n, 08v+n | 1.00000 | 0.94118 ± 0.10189 | |

| 29 | 29o+n, 29v+n | 1.00000 | |||

| 47 | 47o+n, 47v+n | 0.82353 | |||

| HIV−, NP | 04 | 04o−n, 04v−n | 0.98039 | 0.78824 ± 0.18571 | |

| 05 | 05o−n, 05v−n1 | 0.62745 | |||

| 05o−n, 05v−n2 | 0.64706 | ||||

| 14 | 14o−n, 14v−n | 1.00000 | |||

| 25 | 25o−n, 25v−n | 0.68628 | |||

| HIV−, P | 15 | 15o−y, 15v−y | 0.56863 | 0.60130 ± 0.11151 | |

| 23 | 23o−y, 23v−y | 0.72549 | |||

| 30 | 30o−y, 30v−y | 0.50979 | |||

| Oral cavity-rectum | 0.77777 ± 0.17998 (0.88561 ± 0.08171) | ||||

| HIV+, NP | 28 | 28o+n, 28r+n | 0.88235 | 0.89215 ± 0.05660 | |

| 29 | 29o+n, 29r+n | 0.82352 | |||

| 39 | 39o+n, 39r+n | 0.96078 | |||

| 47 | 47o+n, 47r+n | 0.90196 | |||

| HIV−, NP | 04 | 04o−n, 04r−n | 0.98039 | 0.82353 ± 0.22183 | |

| 05 | 05o−n, 05r−n | 0.66667 | |||

| HIV−, P | 15 | 15o−y, 15r−y | 0.50979 | 0.59476 ± 0.14718 | |

| 23 | 23o−y, 23r−y | 0.76471 | |||

| 30 | 30o−y, 30r−y | 0.50979 | |||

| Vagina-rectum | 0.88581 ± 0.15505 (0.95098 ± 0.05995) | ||||

| HIV+, NP | 03 | 03v+n, 03r+n | 0.98039 | 0.80392 ± 0.19411 | |

| 12 | 12v+n, 12r+n | 0.60784 | |||

| 29 | 29v+n, 29r+n | 0.82352 | |||

| 41 | 41v+n, 41r+n1 | 1.00000 | |||

| 41v+n, 41r+n2 | 0.56863 | ||||

| 42 | 42v+n1, 42r+n | 0.56863 | |||

| 42v+n2, 42r+n | 1.00000 | ||||

| 47 | 47v+n, 47r+n | 0.88235 | |||

| HIV−, NP | 04 | 04v−n, 04r−n | 1.00000 | 0.95098 ± 0.05783 | |

| 05 | 05v−n1, 05r−n | 0.96078 | |||

| 05v−n2, 05r−n | 0.94118 | ||||

| 21 | 21v−n, 21r−n | 1.00000 | |||

| 23 | 23v−n, 23r−n | 0.96078 | |||

| 24 | 24v−n, 24r−n | 0.84314 | |||

| HIV−, P | 15 | 15v−y, 15r−y | 0.94118 | 0.97386 ± 0.02995 | |

| 30 | 30v−y, 30r−y | 1.00000 | |||

| 33 | 33v−y, 33r−y | 0.98039 |

Values in parentheses are means ± standard deviation among strains of C. albicans only.

TABLE 5.

Similarity coefficients for sets of isolates from three anatomical locations of seven individuals

| Host groupa | Volunteer no. | Similarity coefficient for isolates from the following body sites:

|

||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Oral cavity-vagina | Oral cavity-rectum | Vagina-rectum | ||

| HIV+, NP | 29 | 1.00000 | 0.82352 | 0.82352 |

| 47 | 0.82352 | 0.90196 | 0.88235 | |

| HIV−, NP | 04 | 0.98039 | 0.98039 | 1.00000 |

| 05 | 0.62745, 0.64706 | 0.66667 | 0.96078, 0.94118 | |

| HIV−, P | 15 | 0.56863 | 0.50979 | 0.94118 |

| 23 | 0.72549 | 0.76471 | 0.96078 | |

| 30 | 0.50979 | 0.50979 | 1.00000 | |

Volunteers 05, 15, and 30 were colonized with two different species at the three body sites (Table 1). Even at the same body site of the same host, different species were isolated from volunteers 41 (rectal sample), 42 (vaginal sample), and 48 (oral sample) (Table 1).

Genetic similarity between isolates from the same or different anatomical locations of different host groups.

Table 6 summarizes the genetic similarity between isolates from the same or different anatomical locations of each of the three host groups. Two sample types were analyzed here; one included all the isolates and the other included only isolates of C. albicans. For all three groups of women, there is no evidence of greater similarity between strains from the same or different body sites at a P value of <0.05 (Table 6). These results do not support the hypothesis that women with HIV infection or pregnancy harbor isolates with higher genetic similarity. Isolates associated with clinical candidiasis were also dispersed throughout the phenogram (Fig. 2). However, there are two noteworthy features in Table 6. First, when all isolates were included in the analysis, oral isolates from all three host groups had a higher degree of genetic similarity to each other than strains from the other two body sites, but similar genetic similarities were observed among isolates from samples from all sites when only strains of C. albicans were analyzed. This was because a slightly higher percentage of oral strains were C. albicans. Second, the standard deviations for each estimate of genetic similarity were high, indicating a high degree of genetic heterogeneity of strains at each body site, as well as between body sites.

TABLE 6.

Similarity between pairs of strains from the same or different anatomical locations

| Host group | Sample type | Similarity coefficient for pairs of isolates from the following body sitesa:

|

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Oral cavity-oral cavity | Vagina-vagina | Rectum-rectum | Oral cavity-vagina | Oral cavity-rectum | Vagina-rectum | ||

| HIV+, NP | All isolates | 0.781 ± 0.465 | 0.713 ± 0.341 | 0.764 ± 0.485 | 0.749 ± 0.421 | 0.777 ± 0.479 | 0.724 ± 0.407 |

| C. albicans | 0.857 ± 0.377 | 0.814 ± 0.243 | 0.851 ± 0.321 | 0.843 ± 0.339 | 0.852 ± 0.337 | 0.846 ± 0.292 | |

| HIV−, NP | All isolates | 0.812 ± 0.519 | 0.705 ± 0.329 | 0.666 ± 0.233 | 0.741 ± 0.424 | 0.681 ± 0.305 | 0.723 ± 0.402 |

| C. albicans | 0.862 ± 0.329 | 0.842 ± 0.296 | 0.831 ± 0.224 | 0.857 ± 0.396 | 0.862 ± 0.349 | 0.850 ± 0.399 | |

| HIV−, P | All isolates | 0.824 ± 0.240 | 0.662 ± 0.312 | 0.631 ± 0.136 | 0.735 ± 0.441 | 0.623 ± 0.262 | 0.669 ± 0.355 |

| C. albicans | 0.824 ± 0.240 | 0.869 ± 0.375 | 0.922b | 0.858 ± 0.296 | 0.863 ± 0.246 | 0.902 ± 0.765 | |

Values are means ± standard deviations.

There was only one pair of isolates for this group, so there is no standard deviation.

DISCUSSION

This study compared opportunistic pathogenic yeasts recovered from three body sites for each of three groups of women. Similar yeast recovery rates were found for all three body locations of all three groups (Table 2). The yeast recovery rates were within the range of those of previous studies based on similar groups of hosts and body sites (15, 17). Also consistent with previous studies, the most common species was C. albicans, regardless of body site and host status (4, 15, 17, 20).

PCR fingerprinting with the M13 core sequence and PA03 provided a very effective method for assessing the genetic similarities of all isolates from all the yeast species recovered in this study. In a previous study, standard reference strains from different species of yeasts pathogenic for humans were found to be different in their PCR fingerprinting profiles when the M13 core sequence was used as a single primer (14). Here, multiple clinical and natural isolates from each of five species were clustered together. Therefore, unlike individual species-specific DNA probes for Southern analysis of strains of a single species (5, 21, 24), PCR fingerprinting and RAPD analysis allow the concurrent identification of species and analysis of similarity among strains both within and between species.

In an earlier study of genetic similarity between isolates of C. albicans from 17 anatomical locations of 52 healthy women, Soll et al. (27) found that certain clusters of isolates were vagina or oral cavity specific. Brawner and Cutler (1) also found that oral strains of C. albicans from immunocompromised individuals were twice as likely to be serotype B than oral strains from immunocompetent individuals. Furthermore, Schmid et al. (22) suggested that in the early manifestation of AIDS in 11 AIDS patients from Leicester, England, indigenous commensal yeasts were replaced by a genetically more homogeneous group of C. albicans strains. However, in the present study, there was no convincing evidence for associations between genotypes of pathogenic yeasts and body site, HIV status, or pregnancy. Why is there a difference in these findings?

One possibility is that all the samples in the other studies were obtained from different geographic areas and different hosts (1, 3, 6, 9, 22, 27, 28). The strains in geographically different samples may have different patterns of relatedness. Isolates in the study by Soll et al. (27) were from Iowa City, Iowa. Strains in the study by Brawner et al. (1) were from different hospitals across the United States. However, in a comparison of two samples of C. albicans strains from patients infected with HIV from two geographically distant areas (one from Durham, N.C., and the other from Vitória, Brazil), little evidence of genetic differentiation was found between these two samples (34).

Methods of analysis and the controls for confounding factors may also contribute to the disparity in these studies. We have presented an overall assessment for correlation between genotypic similarities of isolates and body sites of isolation or host conditions for women in a single geographic area. In the study by Soll et al. (27), small clusters of isolates were first identified on the basis of DNA fingerprinting by Southern hybridization of the moderately repetitive genomic sequence Ca3, and then these small clusters were compared with each other. While this method of analysis might uncover small clusters of potentially ecologically specific genotypes, such a generalization can be risky. Even when we applied a method of analysis similar to that of Soll et al. (27) by breaking the UPGMA phenogram into smaller clusters, we failed to find any statistically significant cluster that would suggest a potential ecological specialization for certain genotypic groups. All major clusters in Fig. 2 had multiple isolates from each body site or host group.

Host histories may also affect colonization and infection. For example, different hosts may have different patterns of behavior that could influence the patterns of transmission and dynamics of yeast microflora. Since C. albicans and other yeasts can be sexually transmitted (15, 23), sexual behavior and the yeast microflora of sexual partners could affect the genetic diversity of yeast isolates.

We must emphasize that the failure to find any significant association between genotypes and body sites, HIV status, or pregnancy does not exclude the possibility that some other samples or genetic markers might detect a significant association (as shown previously by others). Appropriate sampling strategies and analytical methods would be required to control for the effects of geographic heterogeneity, socioeconomic status, and other risk factors.

We successfully applied PCR fingerprinting to investigate the patterns of genetic similarity among strains of opportunistic pathogenic yeasts from three different body sites of each of three groups of women. All body sites and groups of women harbored similar yeast species and genotypic diversities. We found no significant evidence of an association between genotype and body site, HIV status, or pregnancy. These results are consistent with the persistence hypothesis and inconsistent with the replacement hypothesis. However, the persistence hypothesis does not imply a view of a static yeast microflora. On the contrary, the yeast microflora can be very dynamic. A single host could harbor multiple yeast species or multiple genotypes of the same species at the same or different body sites. Furthermore, microevolution of colonizing strains may occur in hosts with recurrent Candida vaginitis (11, 12). It is clear that there is much to learn about mechanisms that influence the basic processes of colonization and the maintenance of yeast microflora in humans.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank all the volunteers for contributing to the collection of strains in this study.

This research is supported by Public Health Service grant AI 28836 from the National Institutes of Health.

Footnotes

This is a contribution of the Duke University Mycology Research Unit.

REFERENCES

- 1.Brawner D L, Cutler J E. Oral Candida albicans isolates from nonhospitalized normal carriers, immunocompetent hospitalized patients, and immunocompromised patients with or without acquired immunodeficiency syndrome. J Clin Microbiol. 1989;27:1335–1341. doi: 10.1128/jcm.27.6.1335-1341.1989. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Chen R S, Boeger J M, McDonald B A. Genetic stability in a population of a plant pathogenic fungus over time. Mol Ecol. 1994;3:209–218. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Clemons K V, Feroze F, Holmberg K, Stevens D. Comparative analysis of genetic variability among Candida albicans isolates from different geographic locales by three genotypic methods. J Clin Microbiol. 1997;35:1332–1336. doi: 10.1128/jcm.35.6.1332-1336.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Coleman D C, Bennett D E, Sullivan D, Gallagher P J, Henman M C, Shanley D B, Russell R J. Oral Candida in HIV infection and AIDS: new perspectives/new approaches. Crit Rev Microbiol. 1993;19:61–82. doi: 10.3109/10408419309113523. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Corlotti A, Chaib F, Couble A, Bourgeois N, Blanchard V, Villard J. Rapid identification and fingerprinting of Candida krusei by PCR-based amplification of the species-specific repetitive polymorphic sequence CKRS-1. J Clin Microbiol. 1997;35:1337–1343. doi: 10.1128/jcm.35.6.1337-1343.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Diaz-Guerra T M, Martinez-Suarez J V, Laguna F, Rodriguez-Tudela J L. Comparison of four molecular typing methods for evaluating genetic diversity among Candida albicans isolates from human immunodeficiency virus-positive patients with oral candidiasis. J Clin Microbiol. 1997;35:856–861. doi: 10.1128/jcm.35.4.856-861.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Edman J, Sobel J D, Taylor M C. Zinc status in women with recurrent vulvovaginal candidiasis. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1986;155:1082–1085. doi: 10.1016/0002-9378(86)90355-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hartl D L, Clark A G. Principles of population genetics. Sunderland, Mass: Sinauer Associates; 1989. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hellstein J, Vawter-Hunart H, Fotos P, Schmid J, Soll D A. Genetic similarity and phenotypic diversity of commensal and pathogenic strains of Candida albicans isolated from oral cavity. J Clin Microbiol. 1993;31:3190–3199. doi: 10.1128/jcm.31.12.3190-3199.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Klein R S, Harris C A, Butkus Small C, Moll B, Lesser M, Friedland G H. Oral candidiasis in high risk patients as the initial manifestation of the acquired immunodeficiency syndrome. N Engl J Med. 1984;311:354–358. doi: 10.1056/NEJM198408093110602. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lockhart S W, Fritch J J, Meier A S, Schröppel K, Srikantha T, Galask R, Soll D R. Colonizing populations of Candida albicans are clonal in origin but undergo microevolution through C1 fragment reorganization as demonstrated by DNA fingerprinting and C1 sequencing. J Clin Microbiol. 1995;33:1501–1509. doi: 10.1128/jcm.33.6.1501-1509.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lockhart S W, Reed B D, Pierson C L, Soll D R. Most frequent scenario for recurrent Candida vaginitis is strain maintenance with “substrain shuffling”: demonstration by sequential DNA fingerprinting with probes Ca3, C1, and CARE2. J Clin Microbiol. 1996;34:767–777. doi: 10.1128/jcm.34.4.767-777.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Mathur S, Goust J M, Horger III E O, Fudenberg H H. Cell-mediated immune deficiency and heightened humoral immune response in chronic vaginal candidiasis. J Clin Lab Immunol. 1978;1:129–134. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Meyer W, Latouche G N, Daniel H-M, Thanos M, Mitchell T G, Yarrow D, Schönian G, Sorrell T C. Identification of pathogenic yeasts of the imperfect genus Candida by polymerase chain reaction fingerprinting. Electrophoresis. 1997;18:1548–1559. doi: 10.1002/elps.1150180911. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Odds F C. Candida and candidosis: a review and bibliography. 2nd ed. Toronto, Ontario, Canada: Bailliere Tindall; 1988. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Odds F C, Schmid J, Soll D R. Epidemiology of Candida infections in AIDS. In: Vanden Bossche H, Mackenzie D W R, Cauwenbergh G, Van Cutsem J, Drouhet E, Dupont B, editors. Mycoses in AIDS patients. New York, N.Y: Plenum Press; 1990. pp. 67–74. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Pfaller M A. Epidemiology of candidiasis. J Hosp Infect (Suppl) 1995;30:329–338. doi: 10.1016/0195-6701(95)90036-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Romero-Piffiguer M D, Vucovich P R, Riera C M. Secretory IgA and secretory component in women affected by recidivant vaginal candidiasis. Mycopathologia. 1985;91:165–170. doi: 10.1007/BF00446295. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Rosenzweig M L. Species diversity in space and time. New York, N.Y: Cambridge University Press; 1995. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Samaranayake L P, Holmstrup P. Oral candidiasis and human immunodeficiency virus infection. J Oral Pathol Med. 1989;18:554–564. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0714.1989.tb01552.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Scherer S, Stevens D A. A Candida albicans dispersed, repeated gene family and its epidemiological applications. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1988;85:1452–1456. doi: 10.1073/pnas.85.5.1452. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Schmid J, Odds F C, Wiselka M J, Nicholson K G, Soll D R. Genetic similarity and maintenance of Candida albicans strains from a group of AIDS patients, demonstrated by DNA fingerprinting. J Clin Microbiol. 1992;30:935–941. doi: 10.1128/jcm.30.4.935-941.1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Schmid J, Rotman M, Reed B, Pierson C L, Soll D R. Genetic similarity of Candida albicans strains from vaginitis patients and their sexual partner. J Clin Microbiol. 1993;31:39–46. doi: 10.1128/jcm.31.1.39-46.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Schmid J, Voss E, Soll D R. Computer-assisted methods for assessing strain relatedness in Candida albicans by fingerprinting with the moderately repetitive sequence Ca3. J Clin Microbiol. 1990;28:1236–1243. doi: 10.1128/jcm.28.6.1236-1243.1990. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Sobel J D. Epidemiology and pathogenesis of recurrent vulvovaginal candidiasis. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1985;152:924–935. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9378(85)80003-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Sokal R R, Rohlf F J. Biometry. 2nd ed. New York, N.Y: W. H. Freeman & Co.; 1981. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Soll D R, Galask R, Schmid J, Hanna C, Mac K, Morrow B. Genetic dissimilarity of commensal strains of Candida spp. carried in different anatomical locations of the same healthy women. J Clin Microbiol. 1991;29:1702–1710. doi: 10.1128/jcm.29.8.1702-1710.1991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Stevens D A, Odds F C, Scherer S. Application of DNA typing methods to Candida albicans epidemiology and correlations with phenotype. Rev Infect Dis. 1990;12:258–266. doi: 10.1093/clinids/12.2.258. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Stoddart J A. A genotypic diversity measure. J Hered. 1983;74:489–490. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Stoddart J A, Taylor J F. Genotypic diversity: estimation and prediction in samples. Genetics. 1988;118:705–711. doi: 10.1093/genetics/118.4.705. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Swofford D L. PAUP4d64: phylogenetic analysis using parsimony (test version). Washington, D.C: Smithsonian Institution of Natural History; 1998. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Witkins S S, Hirsch J, Ledger W J. A macrophage defect in women with recurrent Candida vaginitis and its reversal by prostaglandin inhibitors. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1986;155:790–795. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9378(86)80022-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Xu J, Mitchell T G, Vilgalys R. PCR-RFLP analyses reveal both extensive clonality and local genetic differentiation in Candida albicans. Mol Ecol. 1999;8:59–73. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-294x.1999.00523.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Xu J, Vilgalys R, Mitchell T G. Lack of genetic differentiation between two geographic samples of Candida albicans isolated from patients infected with human immunodeficiency virus. J Bacteriol. 1999;181:1369–1373. doi: 10.1128/jb.181.4.1369-1373.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]