Abstract

Objectives:

To determine whether lower serum albumin in community-dwelling, older adults is associated with increased risk of hospitalization and death independent of pre-existing disease.

Design:

Prospective cohort study of participants in the fifth visit of the Atherosclerosis Risk in Communities (ARIC) study. Baseline data were collected from 2011 to 2013. Follow-up was available to December 31, 2017. Replication was performed in Geisinger, a health system in rural Pennsylvania.

Setting:

For ARIC, 4 United States communities: Washington County, Maryland; Forsyth County, North Carolina; Jackson, Mississippi; and suburbs of Minneapolis, Minnesota.

Participants:

4,947 community-dwelling men and women aged 66 to 90 years.

Exposure:

Serum albumin.

Main outcomes:

Incident all-cause hospitalization and death.

Results:

Among the 4,947 participants, mean age was 75.5 years (SD: 5.12) and mean baseline serum albumin concentration was 4.05 g/dL (SD: 0.30). Over a median follow-up period of 4.42 years (IQI: 4.16 – 5.05), 553 participants (11.2%) died and 2,457 participants (49.7%) were hospitalized at least once. The total number of hospitalizations was 5,725. In analyses adjusted for demographics and numerous clinical characteristics, including tobacco use, obesity, frailty, cardiovascular disease, kidney disease, diabetes c-reactive protein (CRP), cognitive status, alcohol use, medication use, respiratory disease, and systolic blood pressure, 1 g/dL lower baseline serum albumin concentration was associated with higher risk of both hospitalization (IRR:1.58; 95% CI:1.36–1.82; p < 0.001) and death (HR:1.67; 95% CI:1.24–2.24; p < 0.001). Associations were weaker with older age but not different by frailty status or level of high-sensitivity C-reactive protein. Associations between serum albumin, hospitalizations and death were also similar in a real-world cohort of primary care patients.

Conclusions:

Lower baseline serum albumin was significantly associated with increased risk of both all-cause hospitalization and death, independent of pre-existing disease. Older adults with low serum albumin should be considered a high-risk population and targeted for interventions to reduce the risk of adverse outcomes.

Keywords: Serum albumin, hospitalization, death, frailty, bromocresol purple

INTRODUCTION

In healthy individuals, albumin synthesis accounts for approximately one-fourth of total hepatic protein synthesis. However, in inflammatory states, capacity is diverted to synthesis of proteins involved in the inflammatory response, resulting in lower serum albumin. Prior studies have identified a graded, inverse association between lower serum albumin and increased risk of adverse health outcomes, including death, estimating that a standard deviation lower serum albumin concentration is associated with a 24–47% increase in the odds of death.1–5 However, some evidence suggests that the association between serum albumin and risk of death is different by the presence of inflammatory markers6 or that albumin may simply be a proxy for frailty.7 Moreover, the association between serum albumin and markers of more proximate markers of morbidity such as risk of all-cause hospitalization remains poorly characterized.

In this study, we measured serum albumin in 4,947 community-based adults aged 66 to 90 years and then characterized the association with risks of all-cause hospitalization and death. We evaluated whether the associations were modified by the presence of elevated high sensitivity c-reactive protein (hs-CRP, a commonly used clinical marker of inflammation), frailty, and other comorbidities. We replicated the association in Geisinger, a “real-world” integrated health system serving 45 counties across central and northeastern Pennsylvania.

METHODS

Study design

We conducted an analysis of data collected during the Atherosclerosis Risk in Communities (ARIC) study. Between 1987 and 1989, this prospective cohort study enrolled 15,792 community-dwelling men and women aged 45 to 64. The cohort was selected by probability sampling in four U.S. communities: Forsyth County, North Carolina; Jackson, Mississippi; the northwestern suburbs of Minneapolis, Minnesota; and Washington County, Maryland. A detailed description of study design has previously been published.8 Between 2011 and 2013, 6,538 cohort members, then aged 66 to 90, participated in a fifth study visit providing an opportunity to evaluate a contemporary cohort of older adults. Participants were subsequently contacted biannually to obtain follow-up information. The study protocol was approved by the institutional review board of each participating center and informed consent was obtained from participants at each study visit.

For replication, we evaluated patients in the Geisinger Health System, an electronic medical record linked cohort of patients receiving primary care in central and Northeastern Pennsylvania. Data included all inpatient and outpatient visit laboratory data, prescription records, billing codes, and vital signs. The out-migration rate is low, approximately 1% per year.9 For the purpose of temporally matching the ARIC cohort, we considered “baseline” as the earliest outpatient serum albumin laboratory measurement in 2011–2013. The analysis of this dataset was approved by the JHSPH institutional review board.

Study population

In total, 4,947 (75.7%) participants in the fifth ARIC study visit (hereinafter referred to as the “baseline visit”), were included in our analysis. Inclusion criteria were participation in the baseline visit (n=6,538), baseline measurement of serum albumin (n=6,441, 98.5%), and baseline measurement of the following covariates of interest: age, location and race, diabetes, heart failure, coronary heart disease, history of cancer at any site, history of stroke, frailty index, hypertension, sex, estimated glomerular filtration rate (eGFR), hs-CRP, smoking status, body mass index (BMI), urine albumin-to-creatinine ratio (ACR), cognitive status diagnosis, alcohol use, statin use in past 4 weeks, anticoagulant use in past 4 weeks, antianxiety medication use in past 4 weeks, systolic blood pressure, hypertension lowering medication in past 4 weeks, and emphysema or COPD. Covariate availability in the sample is provided in Supplemental Appendix 1. To allow for inference across racial and field center groups, participants were excluded from the analysis if fewer than 20 participants of their racial group were enrolled at a given field center (46, 0.7%). In total, 4,947 participants were included in the final study population.

In Geisinger, 189,794 individuals had available serum albumin at baseline (calendar years 2011–2013). Covariate laboratory values and vitals were taken as the closest outpatient measurement within a year prior to baseline. Individuals were excluded if missing covariate data for eGFR, BMI, or smoking status (N=22,480), or had serum albumin levels outside the range of 1.5–5 g/dL (N=1457), leaving a study population of 165,857 for analysis. Urine ACR which was available in 25,913 individuals and urine protein-to-creatinine ratio (PCR) was available in 3,442 additional individuals. Values of urine PCR were converted to ACR using a validated equation.10 A missing indicator was used for patients missing both ACR and PCR.

Ascertainment of outcomes

Number of hospitalizations was ascertained through self-report during semi-annual telephone follow-up and active surveillance of hospitals near ARIC field centers. Death was ascertained through linkage to the National Death Index.

In Geisinger, death and hospitalization were ascertained from the electronic medical record and the social security death index. Hospitalization was defined as inpatient stays lasting ≥1 day (from admission date to discharge date). Hospitalizations for <1 day were excluded because they likely reflect emergency department visits, observation visits, or elective procedures. There was no maximum length of stay imposed.

Measurement of serum albumin

The University of Minnesota Advanced Research and Diagnostic Laboratory measured albumin in serum from ARIC participants using a BCP assay, the Asahi Kasei Glycated Albumin Assay (Lucia® GA-L Assay, Asahi Kasei Pharma Corporation, Tokyo, Japan) and adapted to the Roche Mod P800 chemistry analyzer (Roche Diagnostics Corporation, Indianapolis, IN 46250). Lower and upper limits of detection were 1 g/dL and 16 g/dL, respectively. Coefficients of variation were 1.9% at a concentration of 4.48 g/dL and 4.0% at a concentration of 2.5 g/dL. Serum albumin was modeled continuously and by quartile. In addition, because previous studies found a serum albumin concentration of <3.5 g/dL of particular significance,1,11 we also analyzed serum albumin as a binary variable with a cut-point at this concentration.

In clinical practice, serum albumin is measured using either bromocresol green (BCG) or bromocresol purple (BCP) dye-binding methods.12 Prior research supports the use of BCP as the preferred reagent because, compared to more widely used BCG methods, BCP methods have smaller relative biases that vary less with albumin concentration.13,14 In a secondary analysis on a subset of participants (n=20), we verified that the Asahi Kasei BCP assay performed similarly to the more commonly used Roche BCP assay. Association between measurements obtained by the two assays was estimated using linear regression. Agreement was visualized using Bland-Altman analysis. Albumin from Geisinger’s electronic medical record reflects values from several different clinical laboratories but the Geisinger central lab uses the BCG assay.

Measurement of covariates

In ARIC, participants reported their date of birth, sex, race, current smoking status, current alcohol use, and history of heart failure, coronary artery disease, or stroke during structured interview with a trained interviewer. Initial report of history of heart failure, coronary artery disease and stroke were made during study visit 1 with subsequent events identified by physician adjudication. Body mass index (weight (kg))/(height (m))2 was calculated using measurements obtained during clinical examination by a trained examiner during visit 5. Frailty was defined according to Fried et al. using the following five components: (1) weight loss, (2) slowness, (3) exhaustion, (4) weakness, and (5) low physical activity.15 Participants were classified as “frail” if 3 or more of the components were present and “pre-frail” if 1 or 2 components were present, as done previously.16 Further covariate measurement information is provided in Supplemental Appendix 1.

For Geisinger, all demographic and clinical covariates were ascertained using electronic medical record data. Demographic variables included age, sex, and race. Body mass index (kg/m2) was based on the most proximal measurements that occurred on or before the baseline date within three year and analyzed as a continuous variable. Smoking status was defined by self-report that occurred on or before the baseline date. Baseline serum creatinine based on the most proximal measurements that occurred on or before the baseline date within one year, was converted to eGFR using the CKD Epidemiology Collaboration equation.17 All creatinine values were measured using isotope-dilution mass spectrometry traceable assays according to manufacturer specifications.18 Medical comorbidities, including coronary artery disease, stroke, heart failure, cancer, diabetes, and hypertension were defined using documentation of International Classification of Diseases, Ninth Revision (ICD-9) and ICD-10 codes.

Statistical analysis

Descriptive statistics were used to characterize the study population overall and to identify differences by serum albumin quartile. Differences in baseline characteristics by serum albumin quartile were tested using analysis of variance, Kruskal-Wallis and Pearson χ2 tests.

The distribution of serum albumin was assessed and confirmed to be approximately normal. Negative binomial regression models were used to examine the association between serum albumin and number of hospitalizations from baseline (2011–2013) until either the date of death registered by the National Death Index or administrative censoring (31 December 2016). Cox proportional hazards regression models were used to examine the association between serum albumin and mortality, again incorporating time from baseline (2011–2013) until censoring. Incidence rate ratios and hazard ratios were estimated per 1 g/dL difference in serum albumin and categorically by quartile.

To examine the independent associations of serum albumin with risk of hospitalization and death, we evaluated both unadjusted models and models adjusted for baseline covariates. Given the disparate distribution of race across field centers, race and field center were analyzed as a combined variable, race-center. The adjusted models included serum albumin, age, sex, race-center, body mass index, frailty index, smoking status, loge-transformed hs-CRP, hypertension, diabetes, eGFR, loge-transformed UACR, heart failure, coronary heart disease, history of stroke and cancer. We modeled serum albumin using both restricted cubic and linear splines, but the associations between albumin and the outcomes of interest were best modeled with a linear term. Effect modification was assessed by including a product term between albumin and the following variables: age, sex, smoking status, hs-CRP, diabetes status, and frailty index. Similar procedures were used in Geisinger, although hs-CRP and frailty status were not tested since those variables are not routinely collected in clinical practice. In a secondary analysis, the sensitivity of observed associations to selection bias caused by differential participation in the visit 5 exam was assessed using inverse probability of attrition weighting (IPAW).

Statistical tests were two-sided, significance was assessed at an α level of 0.05, and analyses were conducted using Stata version 15.1 (StataCorp, LLC, College Station, TX).

RESULTS

Baseline characteristics of the study population

Among 4,947 ARIC participants included in the analysis, mean age was 75.5 (standard deviation [SD]: 5.12) years, 2,188 (44.2%) participants were male, and 1,089 (22.0%) participants identified as Black (Table 1). Mean baseline serum albumin was 4.05 g/dL (SD 0.30). Compared to those with baseline serum albumin in the highest quartile, participants with albumin in the lower quartiles were more likely to be older, female, Black, and current cigarette smokers. They were also more likely to have higher BMI, higher hs-CRP, lower eGFR, and to have diabetes, heart failure, or a history of stroke. Participants who were frail and pre-frail had lower average albumin than those who were not frail (Figure S1).

Table 1.

Baseline characteristics of ARIC participants by quartile of serum albumin (N = 4947)

| Serum albumin (g/dL) | P-valuea | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Quartile 1 | Quartile 2 | Quartile 3 | Quartile 4 | |||||

| (2.03–3.87 g/dL) | (3.88–4.07 g/dL) | (4.08–4.25 g/dL) | (4.26–5.20 g/dL) | |||||

| n = 1,288 | n = 1,238 | n = 1,210 | n = 1,211 | |||||

| Age (years) - mean (SD) | 75.9 (5.2) | 75.8 (5.2) | 75.4 (5.2) | 75.0 (4.8) | < 0.001 | |||

| Sex - no. (%) | ||||||||

| Female | 803 (62.3%) | 683 (55.2%) | 668 (55.2%) | 605 (50.0%) | < 0.001 | |||

| Location and race - no. (%) | ||||||||

| Location | Race | |||||||

|

|

||||||||

| Forsyth County, NC | Black | 24 (1.9%) | 22 (1.8%) | 15 (1.2%) | 12 (1.0%) | < 0.001 | ||

| Forsyth County, NC | White | 216 (16.8%) | 235 (19.0%) | 280 (23.1%) | 281 (23.2%) | |||

| Jackson, MS | Black | 413 (32.1%) | 269 (21.7%) | 199 (16.4%) | 135 (11.1%) | |||

| Minneapolis, MN | White | 323 (25.1%) | 376 (30.4%) | 394 (32.6%) | 388 (32.0%) | |||

| Washington County, MD | White | 312 (24.2%) | 336 (27.1%) | 322 (26.6%) | 395 (32.6%) | |||

| Body mass index (kg/m2) - mean (SD) | 30.7 (7.0) | 28.9 (5.3) | 28.3 (5.1) | 27.2 (4.5) | < 0.001 | |||

| Frailty index - no. (%) | ||||||||

| Frail | 135 (10.5%) | 93 (7.5%) | 64 (5.3%) | 50 (4.1%) | < 0.001 | |||

| Prefrail | 701 (54.4%) | 604 (48.8%) | 550 (45.5%) | 528 (43.6%) | ||||

| Robust | 452 (35.1%) | 541 (43.7 %) | 596 (49.3%) | 633 (52.3%) | ||||

| Smoking status - no. (%) | ||||||||

| Current smoker | 92(7.1%) | 66 (5.3%) | 79 (6.5%) | 51 (4.2%) | 0.005 | |||

| Former smoker | 623 (48.4%) | 608 (49.1%) | 599 (49.5%) | 626 (51.7%) | ||||

| Never smoker | 481 (37.3%) | 508 (41.0%) | 457 (37.8%) | 472 (39.0%) | ||||

| Unknown | 92 (7.1%) | 56 (4.5%) | 75 (6.2%) | 62 (5.1%) | ||||

| hs-CRP (mg/L) - median (IQI) | 3.0 (1.4, 6.3) | 2.2 (1.1, 4.6) | 1.9 (0.9, 3.6) | 1.4 (0.7, 2.7) | < 0.001 | |||

| Hypertension - no. (%) | 995 (77.3%) | 924 (74.6%) | 894 (73.9%) | 905 (74.7%) | 0.22 | |||

| Diabetes - no (%) | 526 (40.8%) | 416 (33.6%) | 365 (30.2%) | 373 (30.8%) | < 0.001 | |||

| eGFR (mL/min per 1.73 m2) - mean (SD) | 67.5 (18.9) | 69.4 (17.4) | 69.4 (16.9) | 70.4 (15.8) | < 0.001 | |||

| UACR (mg/g) - median (IQI) | 10.7 (6.01 26.6) | 10.8 (6.1, 24.0) | 10.2 (6.45 21.4) | 10.8 (6.7, 22.2) | 0.50 | |||

| Heart failure - no. (%) | 273 (21.2%) | 199 (16.1%) | 161 (13.3%) | 163 (13.5%) | < 0.001 | |||

| Coronary heart disease - no. (%) | 229 (17.8%) | 200 (16.2%) | 195 (16.1%) | 221 (18.2%) | 0.37 | |||

| History of stroke - no. (%) | 76 (5.9%) | 43 (3.5%) | 35 (2.9%) | 37 (3.1%) | < 0.001 | |||

| History of cancer - no. (%) | 43 (3.3%) | 43 (3.5%) | 35 (2.9%) | 37 (3.1%) | 0.93 | |||

Analysis of variance for continuous variables with a normal distribution, Kruskal-Wallis test for continuous variables with a skewed distribution, χ2 test for categorical variables

hs-CRP, high-sensitivity C-reactive protein; eGFR, estimated glomerular filtration rate; UACR, urine albumin-to-creatinine ratio

In the replication cohort, mean age was 55.4 (SD 17.7) years, 70,325 (57.6%) participants were male, and 3,440 (2.1%) participants identified as Black (Table S1). Mean baseline serum albumin was 4.30 g/dL (SD 0.35). Compared to those with baseline serum albumin in the highest quartile, participants with serum albumin in the lower quartiles were more likely to be older, female, Black, and have been a previous smoker. They were more likely to have higher BMI, lower eGFR, and hypertension, diabetes, heart failure, coronary heart disease, history of stroke, or history of cancer.

Events during follow-up

In ARIC, during a median follow-up period of 4.42 years (interquartile interval (IQI):4.16–5.05), 2,457 participants were hospitalized at least once. Total number of hospitalizations was 5,725; median number per participant was 1 (IQI: 0–2). The overall incidence rate for hospitalization was 26.2 hospitalizations per 100 person-years. There were 553 (11.2%) participants who died during follow-up, and the overall incidence rate for death was 2.5 deaths per 100 person-years (Table 2).

Table 2.

Follow-up time and events by quartile of serum albumin in ARIC and Geisinger

| ARIC | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||

| Serum albumin (g/dL) | ||||

| Quartile 1 | Quartile 2 | Quartile 3 | Quartile 4 | |

| (2.03–3.87 g/dL) | (3.88–4.07 g/dL) | (4.08–4.25 g/dL) | (4.26–5.20 g/dL) | |

| Follow-up time | ||||

| Number of participants | 1288 | 1238 | 1210 | 1211 |

|

| ||||

| Follow-up time In person-years | 5,575 | 5,464 | 5,426 | 5,423 |

|

| ||||

| Hospitalizations | ||||

| Number of hospitalizations | 1,974 | 1,400 | 1,178 | 1,173 |

|

| ||||

| Incidence per 100 person-years | 35.4 | 25.6 | 21.7 | 21.6 |

|

| ||||

| Incidence rate ratio (95% CI) | 1.33 (1.17–1.51) | 1.09 (0.96–1.23) | 1.00 (0.88–1.14) | 1 |

|

| ||||

| Deaths | ||||

| Number of deaths | 187 | 167 | 109 | 90 |

|

| ||||

| Incidence per 100 person-years | 3.4 | 3.1 | 2.0 | 1.7 |

|

| ||||

| Hazard ratio (95% CI) | 1.49 (1.14–1.96) | 1.56 (1.19–2.04) | 1.17 (0.88–1.56) | 1 |

| Geisinger | ||||

|

| ||||

| Serum albumin (g/dL) | ||||

| Quartile 1 | Quartile 2 | Quartile 3 | Quartile 4 | |

| (1.5–4.1 g/dL) | (4.2–4.3 g/dL) | (4.4–4.5 g/dL) | (4.6–5.0 g/dL) | |

|

| ||||

| Follow-up time | ||||

| Number of participants | 45,604 | 40,593 | 41,468 | 38,192 |

|

| ||||

| Follow-up time In person-years | 271,474 | 268,849 | 278,070 | 255,946 |

|

| ||||

| Hospitalizations | ||||

| Number of hospitalizations | 69,918 | 39,996 | 33,631 | 24,094 |

|

| ||||

| Incidence per 100 person-years | 25.8 | 14.9 | 12.1 | 9.4 |

|

| ||||

| Incidence rate ratio (95% CI) | 1.78 (1.73–1.83) | 1.31 (1.27–1.35) | 1.15 (1.12–1.18) | 1 |

|

| ||||

| Deaths | ||||

| Number of deaths | 12,652 | 4,950 | 3,450 | 1,947 |

|

| ||||

| Incidence per 100 person-years | 4.7 | 1.8 | 1.2 | 0.8 |

|

| ||||

| Hazard ratio (95% CI) | 2.36 (2.25–2.48) | 1.33 (1.26–1.41) | 1.14 (1.08–1.20) | 1 |

Reported incidence rate ratios and hazard ratios are adjusted for all covariates of interest and compare serum albumin quartiles 1, 2, and 3 to quartile 4.

In the ARIC adjusted model, a 1 g/dL decrease in baseline serum albumin concentration was associated with an incidence rate ratio for hospitalization of 1.58 (95% CI: 1.36–1.82) and a hazard ratio for death of 1.67 (95% CI: 1.24–2.24). In the Geisinger adjusted model, a 1 g/dL decrease in baseline serum albumin concentration was associated with an incidence rate ratio for hospitalization of 1.94 (95% CI: 1.88–1.99) and a hazard ratio for death of 3.30 (95% CI: 3.20–3.40).

In Geisinger, median follow-up was 7.0 years (IQI 5.9–7.7), and 59,735 participants were hospitalized at least once. Total number of hospitalizations was 167,639. The incidence of hospitalization and death were slightly lower than that observed in the ARIC participants, at 15.4 hospitalizations per 100 person-years and 2.1 deaths per 100 person-years.

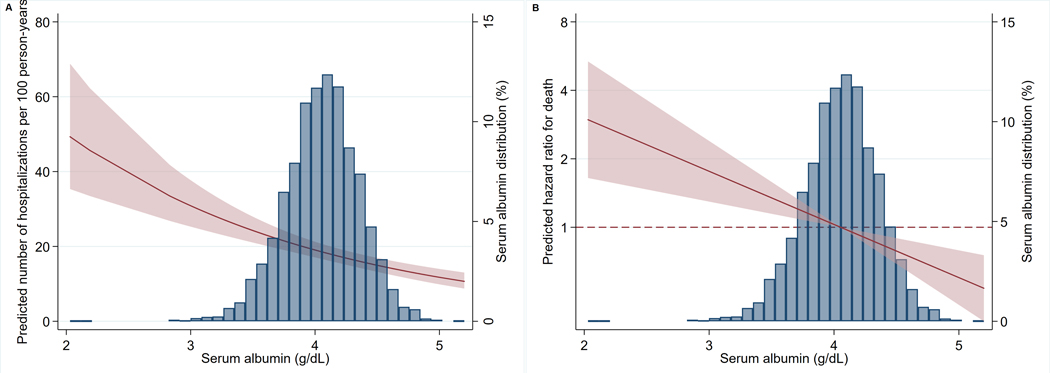

Associations between serum albumin and adverse events

Lower baseline serum albumin concentration was associated with higher risks of hospitalization and death in the ARIC cohort (Figure 1). Incidence rate ratios for hospitalization per 1 g/dL lower baseline serum albumin were 2.27 (95%CI: 1.96–2.62) in the unadjusted model and 1.58 (95%CI: 1.36–1.82) in the adjusted model. Hazard ratios for death were 2.69 (95%CI: 2.06–3.50) in the unadjusted model and 1.67 (95%CI 1.24– 2.24) in the adjusted model. In the adjusted model, compared to quartile 4 (serum albumin: 4.26–5.20g/dL), quartile 1 (serum albumin: 2.03–3.87g/dL) had higher risk of both hospitalization (IRR 1.33, 95%CI: 1.17–1.51) and death (HR 1.49; 95%CI: 1.14–1.96). Compared to quartile 4, quartile 2 (serum albumin: 3.88–4.07g/dL) had increased risk of death only (HR 1.56; 95%CI: 1.19–2.04) (Table 2). In the dichotomous analysis of serum albumin using 3.5 g/dL as the cutpoint, albumin <3.5 g/dL was associated with higher risk of both hospitalization (IRR: 1.64; 95%CI: 1.34–2.02; p<0.001) and death (HR 1.59; 95%CI 1.16–2.18; p=0.004). Survival curves can be found in the Supplementary Materials (Figure S2).

Figure 1. Predicted incidence rate for hospitalization and hazard ratio for death by serum albumin concentration (g/dL) with 95% confidence intervals (CI, shaded area).

Predicted incidence rates and hazard ratios were calculated from the fitted models. Predicted incidence rate for hospitalization (A) and hazard ratio for death (B) are displayed as a function of baseline serum albumin concentration. Models adjusted for age, sex, race-center, body mass index (BMI), frailty index, smoking status, loge-transformed high-sensitivity C-reactive protein (hs-CRP), hypertension, diabetes, glomerular filtration rate (GFR), loge-transformed urine albumin-to-creatinine ratio (UACR), heart failure, coronary heart disease, history of stroke and cancer. Predictions assume individuals are robust, non-smokers from the largest race and field center subgroup (whites living in the suburbs of Minneapolis, MN) with mean values for all remaining variables.

In Geisinger, associations were slightly stronger than in the ARIC study. The adjusted incidence rate ratio of hospitalization per 1 g/dL lower baseline serum albumin was 1.94 (95%CI: 1.88–1.99). The adjusted incidence rate ratio of death per 1 g/dL lower baseline serum albumin was 3.30 (95%CI: 3.20–3.40). In the adjusted model, compared to quartile 4 (serum albumin: 4.6–5.0 g/dL), quartile 1 (serum albumin: 1.5–4.1 g/dL) had higher risk of both hospitalization (IRR 1.78, 95%CI: 1.73–1.83) and death (HR 2.36; 95%CI: 2.25–2.48).

Associations of other characteristics with hospitalization and death in ARIC

High-sensitivity CRP was an independent risk factor for hospitalization (adjusted IRR 1.10, 95%CI: 1.06–1.15) and death (adjusted HR 1.13, 95%CI: 1.05–1.23) as was frailty (Table 3). Other laboratory variables that were consistently related with both outcomes included eGFR and urine ACR; the pulmonary markers self-reported COPD or emphysema and lower forced vital capacity and the cardiac markers were similarly consistent risk factors for both hospitalization and death.

Table 3.

Associations of other characteristics with hospitalization and death in ARIC

| Death | Hospitalization | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| HR 95%CI | p-value | IRR 95%CI | p-value | |||

| Serum albumin, per 1 g/dL lower | 1.67 (1.24–2.24) | 0.001 | 1.58 (1.36–1.82) | <0.001 | ||

| Age, per 1 year older | 1.05 (1.03–1.07) | <0.001 | 1.01 (1.00–1.02) | 0.191 | ||

| Female sex | 0.58 (0.46–0.73) | <0.001 | 0.76 (0.67–0.86) | <0.001 | ||

| Location and race | ||||||

| Location | Race | |||||

|

|

||||||

| Forsyth County, NC | Black | 0.92 (0.43–2.00) | 0.844 | 0.64 (0.44–0.92) | 0.016 | |

| Forsyth County, NC | White | 0.79 (0.60–1.03) | 0.080 | 0.80 (0.70–0.91) | 0.001 | |

| Jackson, MS | Black | 0.94 (0.71–1.24) | 0.642 | 0.83 (0.73–0.96) | 0.011 | |

| Minneapolis, MN | White | Ref | Ref | |||

| Washington County, MD | White | 0.95 (0.75–1.20) | 0.655 | 0.92 (0.82–1.03) | 0.159 | |

| Body mass index, per 1 kg/m2 higher | 0.95 (0.94–0.97) | <0.001 | 0.99 (0.99–1.00) | 0.117 | ||

| Frailty index | ||||||

| Frail | 1.57 (1.27–1.95) | <0.001 | 1.41 (1.28–1.55) | <0.001 | ||

| Prefrail | 2.56 (1.91–3.42) | <0.001 | 1.89 (1.59–2.23) | <0.001 | ||

| Robust | Ref | Ref | ||||

| Smoking status | ||||||

| Current smoker | 1.70 (1.20–2.42) | 0.003 | 1.16 (.95–1.40) | 0.143 | ||

| Former smoker | 1.19 (0.97–1.45) | 0.097 | 1.06 (0.96–1.17) | 0.225 | ||

| Never smoker | Ref | Ref | ||||

| Unknown | 1.69 (1.18–2.43) | 0.004 | 1.21 (1.00–1.46) | 0.46 | ||

| Current drinker (vs. never/former) | 0.99 (0.82–1.20) | 0.919 | 0.83 (0.75–0.91) | <0.001 | ||

| Log hs-CRP (mg/L), per 1 unit higher | 1.13 (1.05–1.23) | 0.002 | 1.10 (1.06–1.15) | <0.001 | ||

| Systolic BP, per 1 mm Hg higher | 1.00 (0.99–1.00) | 0.112 | 1.00 (1.00–1.00) | 0.984 | ||

| Diabetes | 1.28 (1.06–1.54) | 0.010 | 1.09 (0.99–1.20) | 0.079 | ||

| eGFR, per 1 mL/min per 1.73 m2 higher | 0.99 (0.99–0.99) | 0.028 | 0.99 (0.99–1.00) | <0.001 | ||

| Log UACR (mg/g), per 1 unit higher | 1.26 (1.18–1.34) | <0.001 | 1.17 (1.12–1.21) | <0.001 | ||

| Heart failure | 1.70 (1.37–2.10) | <0.001 | 1.45 (1.28–1.63) | <0.001 | ||

| Coronary heart disease | 1.10 (0.88–1.37) | 0.378 | 1.34 (1.19–1.51) | <0.001 | ||

| History of stroke | 0.79 (0.54–1.15) | 0.223 | 1.18 (0.96–1.45) | 0.109 | ||

| History of cancer | 2.20 (1.56–3.12) | <0.001 | 1.33 (1.05–1.68) | 0.020 | ||

| Emphysema or COPD | 1.63 (1.26–2.12) | <0.001 | 1.53 (1.29–1.81) | <0.001 | ||

| Forced volume capacity, per 1 unit higher | 0.77 (0.68–0.90) | <0.001 | 0.88 (0.81–0.95) | 0.001 | ||

| Cognitive status | ||||||

| Normal | Ref | Ref | ||||

| Unknown | 3.35 (0.82–13.68) | 0.092 | 2.21 (0.86–5.66) | 0.098 | ||

| Mild cognitive impairment | 1.36 (1.12–1.65) | 0.002 | 1.10 (0.99–1.22) | 0.077 | ||

| Dementia | 2.09 (1.55–2.83) | <0.001 | 1.11 (0.89–1.39) | 0.350 | ||

| Statin use | 0.86 (0.72–1.04) | 0.116 | 0.97 (0.88–1.06) | 0.474 | ||

| Anticoagulant use | 1.53 (1.20–1.96) | 0.001 | 1.16 (0.99–1.35) | 0.070 | ||

| Anti-anxiety medication use | 1.10 (0.79–1.52) | 0.572 | 1.27 (1.08–1.50) | 0.005 | ||

| Antihypertension medication use | 0.89 (0.70–1.15) | 0.377 | 1.18 (1.05–1.32) | 0.005 | ||

Differences in associations by demographic and clinical characteristics

In both cohorts, the magnitude of the associations between lower serum albumin and risks of hospitalization and death was lower for older age (p-values for interactions = 0.01 and 0.05, respectively) (Table 4). By contrast, there was no difference by level of hs-CRP or frailty status in ARIC. Other estimates of effect modification were inconsistent across studies: in ARIC, the magnitude of the association between serum albumin and hospitalization was greater in the presence of diabetes (p-value for interaction = 0.003); the presence of diabetes did not modify the association between albumin and death. In Geisinger, the association between albumin and hospitalization and albumin and death was weaker in the presence of diabetes (p<0.001).

Table 4.

Modification of associations between serum albumin and risks of hospitalization and death in ARIC and Geisinger

| ARIC | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| IRR for hospitalization (95% CI) Per 1 g/dL lower baseline serum albumin | p-value for interaction term | HR for death (95% CI) Per 1 g/dL lower baseline serum albumin | p-value for interaction term | ||

| Age | Population mean | 1.59 (1.36 – 1.85) | 1.81 (1.33 – 2.46) | ||

| Per 5 years older | 1.31 (1.06 – 1.60) | 0.005 | 0.80 (0.63 —1.02) | 0.104 | |

| Sex | Male | 1.34 (1.08 – 1.67) | 1.53 (1.04 – 2.25) | ||

| Female | 1.81 (1.48 – 2.20) | 0.039 | 1.83 (1.21 – 2.77) | 0.523 | |

| Smoking | Never smoker | 1.53 (1.20 – 1.94) | 1.51 (0.91 – 2.51) | ||

| Former smoker | 1.45 (1.18 – 1.77) | 0.727 | 1.47 (1.01 – 2.15) | 0.216 | |

| Current smoker | 2.40 (1.327 – 4.53) | 0.186 | 2.95 (1.14 – 7.60) | 0.929 | |

| hs-CRP | Population mean | 1.65 (1.22 – 2.24) | 1.58 (1.35 – 1.84) | ||

| Per 1 mg/L higher | 1.68 (1.22 – 2.31) | 0.575 | 1.61 (1.35 – 1.92) | 0.714 | |

| Diabetes | No diabetes | 1.40 (1.16 – 1.68) | 1.61 (1.10 – 2.35) | ||

| Diabetes | 1.94 (1.53 – 2.44) | 0.543 | 1.74 (1.13 – 2.65) | 0.784 | |

| Frailty | Robust | 1.64 (1.28 – 2.10) | 1.47 (0.82 – 2.65) | ||

| Prefrail | 1.59 (1.31 – 1.94) | 0.420 | 1.47 (1.22 – 2.52) | 0.836 | |

| Frail | 1.34 - (0.85 – 2.09) | 0.836 | 1.61 (0.83 – 3.13) | 0.615 | |

| Geisinger | |||||

| IRR for hospitalization (95% CI) Per 1 g/dL lower baseline serum albumin | p-value for interaction term | HR for death (95% CI) Per 1 g/dL lower baseline serum albumin | p-value for interaction term | ||

| Age | Population mean | 1.97 (1.91 – 2.02) | 4.66 (4.46 – 4.87) | ||

| Per 5 years older | 0.93 (0.92 – 0.93) | < 0.001 | 0.90 (0.90 — 0.91) | < 0.001 | |

| Sex | Male | 2.19 (2.10 – 2.28) | 3.29 (3.15 – 3.43) | ||

| Female | 1.77 (1.70–1.83) | < 0.001 | 3.31 (3.17 – 3.45) | 0.817 | |

| Smoking | Never smoker | 2.12 (2.04 – 2.21) | 3.35 (3.20 – 3.51) | ||

| Former smoker | 1.77 (1.69 – 1.85) | < 0.001 | 3.21 (3.06 – 3.36) | 0.167 | |

| Current smoker | 1.86 (1.75 – 1.97) | < 0.001 | 3.42 (2.18 – 3.68) | 0.651 | |

| Diabetes | No diabetes | 2.13 (2.06 – 2.20) | 3.60 (3.47 – 3.75) | ||

| Diabetes | 1.48 (1.40 – 1.56) | < 0.001 | 2.90 (2.76 – 3.04) | < 0.001 | |

Sensitivity of associations to selection bias

In ARIC, the associations between serum albumin and risk of hospitalization and death observed in the primary analysis were robust to sensitivity analysis using inverse probability of attrition weighting (IPAW). Adjusting for the likelihood of participation in visit 5 increased the strength of the association between albumin and death. In the primary analysis, the hazard ratio (HR) for death per 1 g/dL lower serum albumin was 1.67 (95%CI: 1.24– 2.24); in the sensitivity analysis, the HR was 1.98 (95%CI: 1.55– 2.54). Similar increases were seen when HR was calculated by quartile of serum albumin. The association between albumin and hospitalization was relatively unchanged by IPAW. Primary and sensitivity analyses were associated with incidence rate ratios (IRR) for hospitalization per 1 g/dL lower in serum albumin of 1.58 (95%CI: 1.36 −1.82) and 1.36 (95%CI 1.03– 1.79), respectively. IRR calculated by quartile of serum albumin were similarly unchanged (Table S2).

Validation of serum albumin assay

The coefficient of determination (R2) for linear regression of Roche BCP assay measurements on Asahi Kasei BCP assay measurements was 0.9455 (Figure S3). Estimated mean difference between assay measurements was 0.076 g/dL, with the Asahi Kasei assay slightly higher than the Roche assay and 95% of the differences between measurements falling within the following interval: −0.106 to +0.257 g/dL (Figure S4).

DISCUSSION

In this community-based cohort of older adults, lower concentrations of serum albumin at baseline were associated with increased risk of hospitalization and death over median follow-up time of 4.6 years. Relative to those with albumin in the highest quartile (≥4.25 g/dL), those with albumin in the lowest quartile (≤3.85 g/dL) had a 33% increased risk of hospitalization and a 49% increased risk of death during the follow-up period. Associations were similar in an external cohort of patients followed in primary care and consistent across markers of inflammation and frailty. Our findings suggest that it may be appropriate to target older adults with lower serum albumin for interventions designed to reduce the risk of hospitalization and/or death, such as enhanced nutritional support or more rigorous clinical monitoring.

Serum albumin has been linked to risk of all-cause and cardiovascular mortality,1,7,19 with studies in British men, middle-aged adults, and patients receiving maintenance dialysis.20–26 Our findings are consistent with these studies, finding increased risk of adverse outcomes in those with lower serum albumin. Serum albumin has been suggested as a marker for frailty and inflammation, and that inflammatory markers, including plasma interleukin-6 (IL-6), modify the association between serum albumin and risk of death.6,7 While we did observe a strong cross-sectional relationship between hs-CRP and albumin as well as frailty status and albumin, these risk factors did not modify the risk associated with low serum albumin. This suggests that albumin may be a good biomarker of mortality and hospitalization risk, even in a population of older adults with a high prevalence of frailty and inflammation.

There are several mechanisms by which serum albumin may confer risk of adverse outcomes. Albumin is a major determinant of oncotic pressure, and low albumin may increase blood viscosity and increase thrombotic risk, as is seen in nephrotic syndrome.27 Animal models also suggest that low albumin may blunt the capillary response to nitric oxide.28 Albumin contains thiol groups which can help scavenge reactive oxygen and nitrogen species, decreasing oxidative stress.29 However, it is also a known acute phase reactant, with decreased production in the setting of inflammation.30 We have expanded upon existing evidence by measuring serum albumin, using a validated BCP assay, in a population that is broadly representative of older adults living in the United States and replicating in a cohort of patients followed in routine clinical care. Prior studies in older adults have suggested that the association between lower serum albumin and increased risk of adverse health outcomes is confounded by pre-existing disease, with attenuation of association in patients with high CRP or frailty.1–6 However, we found that the association held even after rigorously controlling for numerous variables known to be associated with both serum albumin and risk of hospitalization and/or death.

In interpreting our results, it is important to note several study limitations. Because this is an observational study, the possibility of residual confounding remains and causality cannot be demonstrated. Nutritional status as assessed through calorie count or prealbumin level was not available. In addition, the covariates of interest were measured just once, increasing the risk of measurement error. Some covariates, including smoking history, were measured categorically when a continuous measurement, such as pack-years, might have been preferred. Still others were measured using a single indicator when a composite measure might have been preferable. Future research might benefit, for example, from use of a composite measure of inflammation that includes IL-6, tumor necrosis factor-α (TNF-α), and/or TNF-α receptors. Finally, our study population included only those individuals who survived to the fifth visit of the ARIC study and were willing and able to participate; however, we have demonstrated that the generalizability of the ARIC study population actually increases over time.31

However, this study also had numerous strengths. First, cohort participants were carefully phenotyped at a five-hour clinical exam and follow-up was excellent. Second, observed associations were robust to sensitivity analysis using inverse probability of attrition weighted analysis (IPAW), suggesting that they were not biased by differential participation in the fifth visit of the ARIC study. Third, since the absolute risk for hospitalization is high for people with low serum albumin (35.4/100 person-years for people with serum albumin 2.03–3.87 g/dL), incidence risk ratio is an appropriate measure for population with high risks. Finally, in a subset of participants, serum albumin was measured using two different assays and, to our knowledge, this is the first validation study comparing serum albumin measurements obtained using the Asahi Kasei and Roche bromocresol purple (BCP) assays. Our findings suggest that there is no clinically significant difference between measurements obtained by the two assays.

In conclusion, our study demonstrates that lower levels of circulating albumin were associated with increased risks of hospitalization and death in a cohort of older adults. Older adults with lower serum albumin, especially those with concentrations ≤3.85 g/dL, may benefit from preventative interventions to reduce the risk of adverse outcomes.

Supplementary Material

Supplementary Appendix 1. ARIC covariate availability and definitions

Supplementary Table S1. Baseline characteristics of Geisinger participants by quartile of serum albumin (N = 165,857)

Supplementary Table S2. Assessment of the influence of selection bias on observed associations using inverse probability of attrition weighting (IPAW)

Supplementary Figure S1. Distribution of serum albumin (g/dL) by frailty status

Supplementary Figure S2. Survival Curves. Proportion of participants still living by years of follow-up is shown by quartile of serum albumin (A) and using serum albumin concentration of 3.5 g/dL as a cut-point (B).

Supplementary Figure S3. Correlation of serum albumin measurements obtained by Asahi Kasei bromocresol purple (BCP) assay with measurements obtained by Roche BCP assay In this study, we measured serum albumin using the Asahi Kasei Glycated Albumin Assay, a BCP assay. In a secondary analysis on a subset of participants (n=20), we confirmed that the Asahi Kasei BCP assay performed similarly to the more commonly used Roche BCP assay. Association between measurements obtained by the two assays was estimated using linear regression. The coefficient of determination, R2, was 0.9455.

Supplementary Figure S4. Bland-Altman Plot visualizing agreement of serum albumin measurements obtained by Asahi Kasei bromocresol purple (BCP) assay with those obtained by Roche BCP assay

Key points

-

-

Lower serum albumin is associated with increased risk of adverse health outcomes

-

-

Relationships persist when controlling for many potential confounders

-

-

Associations are replicated in a real-world setting

Why does this paper matter?

This paper demonstrates that previously observed associations between lower serum albumin and increased risk of adverse health outcomes persist even after rigorously controlling for potential confounders, including pre-existing disease states and concomitant inflammation.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

Funding statement

The Atherosclerosis Risk in Communities study has been funded in whole or in part with federal funds from the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute; National Institutes of Health; and Department of Health and Human Services under the following contract numbers: HHSN268201700001I, HHSN268201700002I, HHSN268201700003I, HHSN268201700005I, HHSN268201700004I. The authors thank the staff and participants of the ARIC study for their important contributions.

This submission was made possible by the Johns Hopkins Institute for Clinical and Translational Research (ICTR), which is funded in part by grant TL1 TR001078 from the National Institute of Health (NIH) National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences (NCATS) and NIH Roadmap for Medical Research. Its contents are solely the responsibility of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official view of the Johns Hopkins ICTR, NCATS or NIH.

Reagents for the albumin assays were donated by Asahi Kasei Corporation. This work was supported by NIH/National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Disease (NIDDK) Grant R01DK089174 to Dr. Elizabeth Selvin. Dr. Selvin was also supported by K24DK106414. Dr. Grams was supported by K24HL155861.

Footnotes

Conflicts of Interest

We have no conflicts of interest to disclose.

REFERENCES

- 1.Phillips A, Shaper AG, Whincup PH. Association between serum albumin and mortality from cardiovascular disease, cancer, and other causes. Lancet. December 16 1989;2(8677):1434–1436. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Klonoff-Cohen H, Barrett-Connor EL, Edelstein SL. Albumin levels as a predictor of mortality in the healthy elderly. J Clin Epidemiol. March 1992;45(3):207–212. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Gillum RF, Makuc DM. Serum albumin, coronary heart disease, and death. Am Heart J. February 1992;123(2):507–513. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Corti MC, Guralnik JM, Salive ME, Sorkin JD. Serum albumin level and physical disability as predictors of mortality in older persons. JAMA. October 5 1994;272(13):1036–1042. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Weijenberg MP, Feskens EJ, Souverijn JH, Kromhout D. Serum albumin, coronary heart disease risk, and mortality in an elderly cohort. Epidemiology. January 1997;8(1):87–92. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Reuben DB, Ferrucci L, Wallace R, et al. The prognostic value of serum albumin in healthy older persons with low and high serum interleukin-6 (IL-6) levels. J Am Geriatr Soc. November 2000;48(11):1404–1407. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Grossman Y, Barbash IM, Fefer P, et al. Addition of albumin to Traditional Risk Score Improved Prediction of Mortality in Individuals Undergoing Transcatheter Aortic Valve Replacement. J Am Geriatr Soc. November 2017;65(11):2413–2417. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.The Atherosclerosis Risk in Communities (ARIC) Study: design and objectives. The ARIC investigators. Am J Epidemiol. April 1989;129(4):687–702. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Roy J, Shah NR, Wood GC, Townsend R, Hennessy S. Comparative effectiveness of angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors and angiotensin receptor blockers for hypertension on clinical end points: a cohort study. J Clin Hypertens (Greenwich). July 2012;14(7):407–414. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Sumida K, Nadkarni GN, Grams ME, et al. Conversion of Urine Protein-Creatinine Ratio or Urine Dipstick Protein to Urine Albumin-Creatinine Ratio for Use in Chronic Kidney Disease Screening and Prognosis : An Individual Participant-Based Meta-analysis. Ann Intern Med. September 15 2020;173(6):426–435. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Akirov A, Masri-Iraqi H, Atamna A, Shimon I. Low Albumin Levels Are Associated with Mortality Risk in Hospitalized Patients. Am J Med. December 2017;130(12):1465 e1411–1465 e1419. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Wells FE, Addison GM, Postlethwaite RJ. Albumin analysis in serum of haemodialysis patients: discrepancies between bromocresol purple, bromocresol green and electroimmunoassay. Ann Clin Biochem. May 1985;22 ( Pt 3):304–309. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Garcia Moreira V, Beridze Vaktangova N, Martinez Gago MD, Laborda Gonzalez B, Garcia Alonso S, Fernandez Rodriguez E. Overestimation of Albumin Measured by Bromocresol Green vs Bromocresol Purple Method: Influence of Acute-Phase Globulins. Lab Med. October 11 2018;49(4):355–361. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ueno T, Hirayama S, Sugihara M, Miida T. The bromocresol green assay, but not the modified bromocresol purple assay, overestimates the serum albumin concentration in nephrotic syndrome through reaction with alpha2-macroglobulin. Ann Clin Biochem. January 2016;53(Pt 1):97–105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Fried LP, Tangen CM, Walston J, et al. Frailty in older adults: evidence for a phenotype. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. March 2001;56(3):M146–156. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kucharska-Newton AM, Palta P, Burgard S, et al. Operationalizing Frailty in the Atherosclerosis Risk in Communities Study Cohort. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. July 28 2016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Levey AS, Stevens LA, Schmid CH, et al. A new equation to estimate glomerular filtration rate. Ann Intern Med. May 5 2009;150(9):604–612. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Chang AR, Chen Y, Still C, et al. Bariatric surgery is associated with improvement in kidney outcomes. Kidney Int. July 2016;90(1):164–171. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Djousse L, Rothman KJ, Cupples LA, Levy D, Ellison RC. Serum albumin and risk of myocardial infarction and all-cause mortality in the Framingham Offspring Study. Circulation. December 3 2002;106(23):2919–2924. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Goldwasser P, Mittman N, Antignani A, et al. Predictors of mortality in hemodialysis patients. J Am Soc Nephrol. March 1993;3(9):1613–1622. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Owen WF Jr., Lew NL, Liu Y, Lowrie EG, Lazarus JM. The urea reduction ratio and serum albumin concentration as predictors of mortality in patients undergoing hemodialysis. N Engl J Med. September 30 1993;329(14):1001–1006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lowrie EG, Huang WH, Lew NL. Death risk predictors among peritoneal dialysis and hemodialysis patients: a preliminary comparison. Am J Kidney Dis. July 1995;26(1):220–228. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Avram MM, Mittman N, Bonomini L, Chattopadhyay J, Fein P. Markers for survival in dialysis: a seven-year prospective study. Am J Kidney Dis. July 1995;26(1):209–219. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Soucie JM, McClellan WM. Early death in dialysis patients: risk factors and impact on incidence and mortality rates. J Am Soc Nephrol. October 1996;7(10):2169–2175. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Foley RN, Parfrey PS, Harnett JD, Kent GM, Murray DC, Barre PE. Hypoalbuminemia, cardiac morbidity, and mortality in end-stage renal disease. J Am Soc Nephrol. May 1996;7(5):728–736. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Leavey SF, Strawderman RL, Jones CA, Port FK, Held PJ. Simple nutritional indicators as independent predictors of mortality in hemodialysis patients. Am J Kidney Dis. June 1998;31(6):997–1006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Nicholson JP, Wolmarans MR, Park GR. The role of albumin in critical illness. Br J Anaesth. October 2000;85(4):599–610. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Keaney JF Jr., Simon DI, Stamler JS, et al. NO forms an adduct with serum albumin that has endothelium-derived relaxing factor-like properties. J Clin Invest. April 1993;91(4):1582–1589. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Quinlan GJ, Martin GS, Evans TW. Albumin: biochemical properties and therapeutic potential. Hepatology. June 2005;41(6):1211–1219. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Chien SC, Chen CY, Lin CF, Yeh HI. Critical appraisal of the role of serum albumin in cardiovascular disease. Biomark Res. 2017;5:31. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Zheng Z, Rebholz CM, Matsushita K, et al. Survival advantage of cohort participation attenuates over time: results from three long-standing community-based studies. Ann Epidemiol. May 2020;45:40–46 e44. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplementary Appendix 1. ARIC covariate availability and definitions

Supplementary Table S1. Baseline characteristics of Geisinger participants by quartile of serum albumin (N = 165,857)

Supplementary Table S2. Assessment of the influence of selection bias on observed associations using inverse probability of attrition weighting (IPAW)

Supplementary Figure S1. Distribution of serum albumin (g/dL) by frailty status

Supplementary Figure S2. Survival Curves. Proportion of participants still living by years of follow-up is shown by quartile of serum albumin (A) and using serum albumin concentration of 3.5 g/dL as a cut-point (B).

Supplementary Figure S3. Correlation of serum albumin measurements obtained by Asahi Kasei bromocresol purple (BCP) assay with measurements obtained by Roche BCP assay In this study, we measured serum albumin using the Asahi Kasei Glycated Albumin Assay, a BCP assay. In a secondary analysis on a subset of participants (n=20), we confirmed that the Asahi Kasei BCP assay performed similarly to the more commonly used Roche BCP assay. Association between measurements obtained by the two assays was estimated using linear regression. The coefficient of determination, R2, was 0.9455.

Supplementary Figure S4. Bland-Altman Plot visualizing agreement of serum albumin measurements obtained by Asahi Kasei bromocresol purple (BCP) assay with those obtained by Roche BCP assay