Abstract

A commercial disc diffusion test has been evaluated as a screening method for the detection of Candida species with decreased susceptibility to fluconazole. A total of 1,407 Candida strains of different species were tested, and the results were compared with the MIC results. The recently published National Committee for Clinical Laboratory Standards breakpoint criteria have been used. Isolates were classified as susceptible if the MIC for the isolates was ≤8 μg/ml, susceptible-dose dependent (S-DD) if the MIC was 16 to 32 μg/ml, and resistant if the MIC was ≥64 μg/ml. All 77 resistant strains and 121 of 122 S-DD strains had fluconazole zone diameters of ≤21 mm, and most of the strains (91%) had zone diameters of ≤15 mm. It was not possible to distinguish between resistant and S-DD strains by the disc test. Among a total of 1,208 strains found to be susceptible by the microdilution method, 49 (4.1%) yielded fluconazole zone sizes of ≤21 mm and would have been misclassified as resistant or S-DD strains on the basis of the disc test. For the majority (86%) of these 49 strains the fluconazole MIC was 8 μg/ml. The fluconazole disc test is recommended as a simple and reliable screening test for the detection of Candida strains with decreased susceptibility to fluconazole. Fluconazole MICs should be determined for strains found to be resistant by the disc test. The reason for confirmatory testing is twofold: to determine if isolates are resistant or S-DD, since the disc test does not make this distinction, and to identify fluconazole-susceptible strains that are found to be falsely resistant by the fluconazole disc test.

The increased importance of yeasts as a cause of serious infections in hospitalized patients has been documented in several studies (3, 5, 7). In some hospitals in the United States the incidence of nosocomial fungemia is now 10 to 15% among all positive blood cultures (6, 17). This has resulted in an increased use of systemic antifungal agents, especially fluconazole. Despite this increased use and the introduction of standardized susceptibility test methods, routine antifungal susceptibility testing is still not recommended (2). The two main reasons for this are that most Candida spp. have a predictable susceptibility pattern and that the recommended susceptibility test method (11) is quite labor-intensive and therefore not suitable for nonspecialized laboratories with a high daily workload. With increased fluconazole usage, the occurrence of resistant Candida strains will, however, probably increase, and a simple screening test for the detection of such strains would therefore be useful (2).

We have previously reported that fluconazole-resistant Candida albicans strains could be detected by a commercial agar diffusion test (16), and this method has been used since 1991 at the Mycological Laboratory of the National Institute of Public Health (NIPH), Oslo, Norway, in parallel with MIC determinations. The aim of this study was to evaluate the usefulness of this method for fluconazole susceptibility testing of a larger number of C. albicans and other Candida species.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Candida strains.

NIPH receives clinical yeast isolates from all the Norwegian microbiological laboratories for identification and susceptibility testing. From 1994 the identification and susceptibility data for all strains have been entered into a database. In addition, the results for 470 strains received between 1991 and 1994 (mostly isolates from blood culture and pus specimens) have been entered into this database retrospectively. All Candida strains with a fluconazole susceptibility test result in this database until March 1999 have been included in the study. Of the 1,407 strains, 770 (55%) were recovered from blood, 27 were recovered from central venous catheters, 65 were recovered from the respiratory tract, 50 were recovered from urine, and 81 were recovered from other sources. The remaining 414 specimens were pus specimens and included specimens of pus from the abdomen, abscesses, wound and drain secretions, etc. The species were as follows: C. albicans (992; 70.5%), Candida glabrata (142; 10%), Candida tropicalis (105; 7.5%), Candida parapsilosis (76; 5.4%), Candida krusei (42; 3%), Candida norvegensis (16; 1.1%), Candida kefyr (11; 0.8%), Candida guilliermondii (10; 0.7%), and other Candida species (13; 0.9%).

Identification methods.

Identification to the species level was based on a conventional scheme that included determination of germ tube production, microscopic morphology on cornmeal agar, carbohydrate fermentation and assimilation, and urease production (15). The identification was occasionally supported by the use of a commercial system (ATB 32 C; bioMérieux, Marcy l'Etoile, France).

Susceptibility testing.

An agar dilution method was used from 1991 until the end of 1993, and a broth microdilution method was used from 1994 until 1999.

(i) Agar dilution.

An agar dilution method recommended by Pfizer Central Research (Pfizer Central Research, Sandwich, United Kingdom) was used for 393 strains tested before 1994 (16). The majority of these strains (81%) were C. albicans. The agar dilution method has been found to give results comparable to those provided by the reference broth dilution method proposed by the National Committee for Clinical Laboratory Standards (NCCLS) Subcommittee on Antifungal Susceptibility Testing (16).

(ii) Colorimetric broth microdilution method.

A colorimetric broth microdilution method based on NCCLS recommendations (11) was used for 1,014 strains tested in 1994 and later. Testing was performed with twofold drug dilutions in RPMI 1640 medium (Sigma Chemical Co., St. Louis, Mo.) buffered to pH 7.0 with 0.165 M morpholinepropanesulfonic acid (MOPS) buffer (Sigma). The antimycotic stock solutions were diluted according to the recommendations of NCCLS (11). The inoculum was prepared by a spectrophotometric method to give a concentration of 0.5 × 103 to 2.5 × 103 cells per ml in RPMI 1640 medium. Yeast inocula (100 μl) were added to each well of microdilution trays containing 100 μl of antimycotic solution. An oxidation-reduction indicator (Alamar Blue; Alamar Biosciences, Inc., Sacramento, Calif.) was added to each well at the time of inoculation (25 μl of Alamar Blue per well). Final concentrations of fluconazole were 0.125 to 64 μg/ml. The trays were incubated in air at 35°C and were read after 48 h. Growth is indicated by a change in color from dark blue to red. The MIC was defined as the lowest concentration of the antimycotic agent that prevented the development of a red color (12). A quality control C. albicans strain (strain ATCC 90028) was included with each plate used for MIC testing.

(iii) Agar diffusion.

A commercial agar diffusion test from Rosco Laboratory (A/S Rosco, Taastrup, Denmark) was used (14). The inoculum was standardized by using a spectrophotometer to give a concentration of approximately 5 × 105 CFU/ml. A plate containing buffered yeast nitrogen agar with glucose and asparagine was flooded with yeast suspension. Excess fluid was immediately removed with a pipette. The plate was dried for 15 min, and fluconazole disc tablets (with a 15-μg diffusible amount of fluconazole) was placed on the agar surface. The plate was incubated at 35°C, and the zone diameters were measured after 44 to 48 h of incubation. The zones were measured up to where the colonies reached a normal size. A faint growth closer to the disc was disregarded.

(iv) MIC breakpoints.

The recently published NCCLS breakpoint criteria (11, 13) have been used. Isolates were classified as susceptible if the MIC for the isolate was ≤8 μg/ml, susceptible-dose dependent (S-DD) if the MIC was 16 to 32 μg/ml, and resistant if the MIC was ≥64 μg/ml.

RESULTS

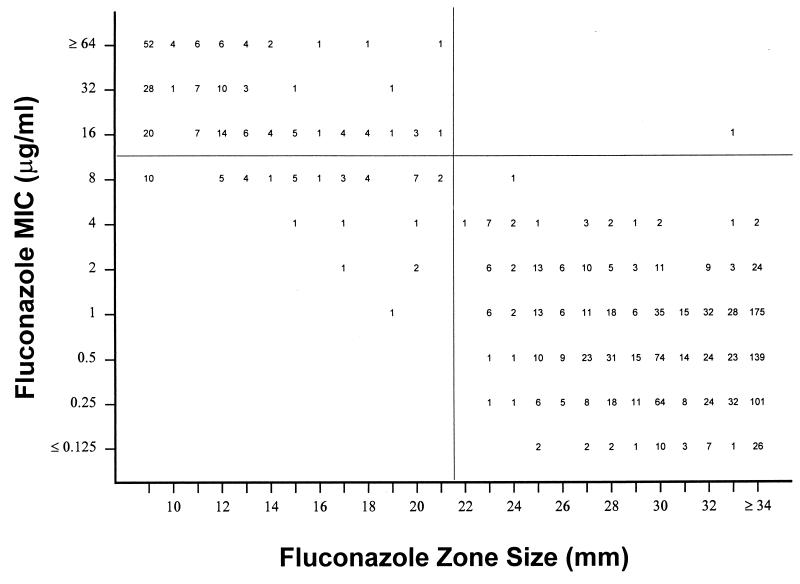

Figure 1 is a scattergram that compares the fluconazole zone diameters with the fluconazole MICs. Of the 77 resistant strains, 74 (96%) had zone diameters of ≤15 mm and the 3 remaining strains had zone diameters between 16 and 21 mm. Of the 122 S-DD strains, 105 (86%) had zone diameters of ≤15 mm, 16 (13%) had zone diameters between 16 and 21 mm, and one strain had a zone diameter of >21 mm (Fig. 1). It was therefore not possible to distinguish between resistant and S-DD strains.

FIG. 1.

Scattergram comparing fluconazole MICs and zone diameters obtained with 15-μg fluconazole discs. Test strains included 1,407 Norwegian clinical Candida isolates.

Among a total of 1,208 strains found to be susceptible by the microdilution method, 49 (4.1%) yielded fluconazole zone sizes of ≤21 mm and would have been misclassified as resistant or S-DD strains on the basis of the disc test. This was, however, mainly a problem with strains for which the fluconazole MIC was 8 μg/ml, as 42 of 43 such strains had zone diameters of ≤21 mm (Fig. 1).

Most of the 199 resistant or S-DD strains belonged to three Candida species, C. glabrata (95 of 142 strains), C. krusei (42 of 42 strains), and C. norvegensis (16 of 16 strains), all of which are known to have decreased susceptibility to fluconazole (Table 1). The remaining 46 resistant or S-DD strains belonged to species usually regarded as fluconazole susceptible (Table 1).

TABLE 1.

Susceptibility test results for the most frequent Candida species and comparison of 48-h MICs with 48-h disc diffusion susceptibility test results

| Species | Disc diffusion test zone diam (mm) | No. of strains for which MIC (μg/ml) is:

|

||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0.125 | 0.25 | 0.5 | 1 | 2 | 4 | 8 | 16 | 32 | ≥64 | Total | ||

| C. albicans | 0–15 | 2 | 7 | 10 | 9 | 28 | ||||||

| 16–21 | 2 | 3 | 1 | 6 | ||||||||

| ≥22 | 48 | 264 | 331 | 256 | 50 | 8 | 1 | 958 | ||||

| C. glabrata | 0–15 | 19 | 42 | 16 | 26 | 103 | ||||||

| 16–21 | 11 | 9 | 1 | 1 | 22 | |||||||

| ≥22 | 2 | 2 | 3 | 6 | 4 | 17 | ||||||

| C. tropicalis | 0–15 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 4 | |||||||

| 16–21 | 3 | 1 | 3 | 7 | ||||||||

| ≥22 | 1 | 2 | 9 | 45 | 28 | 8 | 1 | 94 | ||||

| C. parapsilosis | 0–15 | 1 | 1 | 2 | ||||||||

| 16–21 | 1 | 1 | 2 | |||||||||

| ≥22 | 1 | 4 | 19 | 42 | 6 | 72 | ||||||

| C. krusei | 0–15 | 3 | 13 | 25 | 41 | |||||||

| 16–21 | 1 | 1 | ||||||||||

| C. norvegensis | 0–15 | 5 | 11 | 16 | ||||||||

| C. guilliermondii | 0–15 | 2 | 3 | 1 | 6 | |||||||

| 16–21 | 1 | 1 | ||||||||||

| ≥22 | 2 | 1 | 3 | |||||||||

| Other species | 0–15 | 5 | 1 | 6 | ||||||||

| 16–21 | 1 | 1 | 2 | |||||||||

| ≥22 | 2 | 9 | 3 | 1 | 1 | 16 | ||||||

| All strains | 0–15 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 25 | 56 | 50 | 74 | 206 |

| 16–21 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 3 | 2 | 17 | 14 | 1 | 3 | 41 | |

| ≥22 | 54 | 279 | 364 | 347 | 92 | 22 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1,160 | |

The MIC for the quality control strain included with each microdilution plate was within the recommended MIC limits (0.25 to 1.0 μg/ml) given by NCCLS (11) in approximately 98% of the tests. The microdilution test was repeated on the few occasions that the MIC was outside this range.

DISCUSSION

The development of a standardized antifungal susceptibility test method by NCCLS has been important, and the in vitro results of the MIC determinations have been shown to correlate quite well with clinical outcome (13). The broth dilution fungal MIC methods are, however, complex and labor-intensive. This makes it difficult for the routine clinical microbiology laboratory to perform antifungal susceptibility testing. We have therefore previously evaluated a commercial agar diffusion test for use as a screening test in nonspecialized laboratories (16). In the previous study that included 224 C. albicans strains, it was concluded that this test seemed to be an appropriate method for the detection of strains with decreased susceptibilities to fluconazole. On the basis of these encouraging results it was considered important to evaluate the test with a larger number of strains including different Candida species.

The results of the present study show that the agar diffusion test detected all 77 resistant strains (MICs, ≥64 μg/ml) and 121 of 122 S-DD strains (MICs, 16 or 32 μg/ml). Only one S-DD strain with a zone diameter of 33 mm was not detected (Fig. 1). It was, however, not possible by the disc method to distinguish between resistant and S-DD strains since the majority of strains in both these categories have zone diameters in the range of 9 to 15 mm.

The fluconazole disc test read after 48 h of incubation is therefore a sensitive method for the detection of resistant and S-DD Candida strains. However, among a total of 1,208 susceptible strains, 49 (4.1%) had fluconazole zone diameters of ≤21 mm and would therefore have been classified as resistant by the disc test. This is probably not a serious problem because for 86% of these strains the fluconazole MIC was only 1 dilution step below the S-DD breakpoint of 16 μg/ml. Since the results of MIC tests may vary by at least ±1 dilution step, it might be an advantage that a screening test for fluconazole-resistant or -S-DD Candida strains also detects strains for which the MIC is 8 μg/ml.

When the disc diffusion test is used as a screening test for the detection of fluconazole-resistant Candida strains, it is important that the performance of the test be controlled by the use of suitable quality control strains. Since 1998 the manufacturer has recommended the use of one fluconazole-susceptible strain (C. albicans ATCC 64658) and one fluconazole-resistant strain (C. albicans ATCC 64550) as quality control strains (14).

The ability of the agar diffusion test to detect resistant Candida strains has also been investigated in other studies. In our first study with 224 C. albicans strains, colleagues and I found that all 12 strains for which the MIC was ≥12.5 μg/ml were detected by the disc test (16). Barry and Brown (1) evaluated a fluconazole disc test using 250 Candida strains belonging to five species. When the disc test result read at 48 h was compared to the result obtained by the NCCLS method, they found that 3 of 47 resistant strains and 7 of 42 S-DD strains were not detected by the disc test. Nine of the 161 susceptible strains were classified as resistant by the disc test, and for 8 of these strains the MIC was 8 μg/ml. May et al. (10) detected all 138 resistant and all except 1 of the 58 S-DD Candida strains by the disc test. Of the 78 susceptible strains, 12 strains for which the MIC was 8 μg/ml and 1 strain for which the MIC was 4 μg/ml were classified as resistant. In a smaller study with 40 Candida isolates (9) MICs were ≥16 μg/ml for 14 strains, and 11 (79%) of these were detected by the disc test. A recent study by Cantón et al. (4) with 143 Candida isolates from blood cultures evaluated the same commercial disc method that colleagues and I have used in our two studies. In their study, however, the results of the disc test were read after 24 h and not 48 h, as in our studies. They found that all seven resistant strains and four of seven S-DD strains had zone diameters of <22 mm. Of the 129 susceptible strains, 19 strains (15%) had zone diameters of <22 mm and were classified as resistant by the disc test. Their results differ from those of the other studies in that the MICs for 17 of the 19 misclassified strains were low (MICs, <8 μg/ml). It is possible that the shorter incubation time used by Cantón et al. (4) might explain the differences. In my experience, the zone diameters are often difficult to read after 24 h due to poor growth, and this is the reason why 48 h of incubation has been used routinely at NIPH. May et al. (10) used an inoculum (equivalent to a McFarland no. 2 standard) much higher than that recommended by the manufacturer of the disc test used in the present study and found no significant difference between zone diameters measured at 24 and 48 h (10). It would be a great advantage if the disc test could be read after 24 h of incubation.

Although the disc test methods used in these different studies vary somewhat, it is apparent that the method should be well suited as a screening test for fluconazole-resistant and -S-DD Candida strains. Resistant strains have nearly always been detected. The only exception was three strains in one study (1) and possibly one or two strains in the study by Kirkpatrick et al. (9). Most S-DD strains are also detected. Susceptible strains, especially strains for which the MIC is 8 μg/ml, might, however, be reported as resistant by the disc test.

The results obtained by the fluconazole disc test are quite comparable to the results obtained by the much used oxacillin disc screening test for detection of penicillin-resistant pneumococci (8). It is probable that the fluconazole disc test could be used in a manner similar to that in which the oxacillin disc test is used. Clinically significant Candida isolates should be tested by a fluconazole disc test. The majority of Candida strains are susceptible to fluconazole and will have a zone diameter above the selected breakpoint (>21 mm in the present study), and these strains could safely be reported as susceptible. Fluconazole MICs should be determined for strains with zone diameters below the selected breakpoint (≤21 mm in the present study). The reason for confirmatory testing is twofold: to determine if isolates are resistant or S-DD, since the fluconazole disc test does not make this distinction, and to identify fluconazole-susceptible strains that are found to be falsely resistant by the disc test.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

Excellent technical assistance was provided by Kari Nilsen and Ingrid Grønli.

REFERENCES

- 1.Barry A L, Brown S D. Fluconazole disk diffusion procedure for determining susceptibility of Candida species. J Clin Microbiol. 1996;34:2154–2157. doi: 10.1128/jcm.34.9.2154-2157.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bille J. When should Candida isolates be tested for susceptibility to azole antifungal agents? Eur J Clin Microbiol Infect Dis. 1997;16:281–282. doi: 10.1007/BF01695631. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bruun B, Westh H, Stenderup J. Fungemia: an increasing problem in a Danish university hospital 1989 to 1994. J Clin Microbiol Infect. 1995;1:124–126. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-0691.1995.tb00456.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Cantón E, Pemán J, Carrillo-Muñoz A, Orero A, Ubeda P, Viudes A, Gobernado M. Fluconazole susceptibilities of bloodstream Candida sp. isolates as determined by National Committee for Clinical Laboratory Standards method M27-A and two other methods. J Clin Microbiol. 1999;37:2197–2200. doi: 10.1128/jcm.37.7.2197-2200.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Chakrabarti A, Ghosh A, Batra R, Kaushal A, Roy P, Singh H. Antifungal susceptibility pattern of non-albicans Candida species & distribution of species isolated from candidaemia cases over a 5 year period. Indian J Med Res. 1996;104:171–176. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Cockerill F R, Hughes J G, Vetter E A, Mueller R A, Weaver A L, Ilstrup D M, Rosenblatt J E, Wilson W R. Analysis of 281,797 consecutive blood cultures performed over an eight-year period: trends in microorganisms isolated and the value of anaerobic culture of blood. Clin Infect Dis. 1997;24:403–418. doi: 10.1093/clinids/24.3.403. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hung C C, Chen Y C, Chang S C, Luh K T, Hsieh W C. Nosocomial candidemia in a university hospital in Taiwan. J Formos Med Assoc. 1996;95:19–28. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Jette L P, Sinave C. Use of an oxacillin disk screening test for detection of penicillin- and ceftriaxone-resistant pneumococci. J Clin Microbiol. 1999;37:1178–1181. doi: 10.1128/jcm.37.4.1178-1181.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kirkpatrick W R, Turner T M, Fothergill A W, McCarthy D I, Redding S W, Rinaldi M G, Patterson T F. Fluconazole disk diffusion susceptibility testing of Candida species. J Clin Microbiol. 1998;36:3429–3432. doi: 10.1128/jcm.36.11.3429-3432.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.May J L, King A, Warren C A. Fluconazole disc diffusion testing for the routine laboratory. J Antimicrob Chemother. 1997;40:511–516. doi: 10.1093/jac/40.4.511. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.National Committee for Clinical Laboratory Standards. Reference method for broth dilution antifungal susceptibility testing of yeasts; approved standard. NCCLS document M27-A. Wayne, Pa: National Committee for Clinical Laboratory Standards; 1997. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Pfaller M A, Barry A L. Evaluation of a novel colorimetric broth microdilution method for antifungal susceptibility testing of yeast isolates. J Clin Microbiol. 1994;32:1992–1996. doi: 10.1128/jcm.32.8.1992-1996.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Rex J H, Pfaller M A, Galgiani J N, Bartlett M S, Espinel-Ingroff A, Ghannoum M A, Lancaster M, Odds F C, Rinaldi M G, Walsh T J, Barry A L. Development of interpretive breakpoints for antifungal susceptibility testing: conceptual framework and analysis of in vitro-in vivo correlation data for fluconazole, itraconazole, and Candida infections. Clin Infect Dis. 1997;24:235–247. doi: 10.1093/clinids/24.2.235. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Rosco. Neo-Sensitabs, susceptibility testing. Taastrup, Denmark: A/S Rosco; 1998. pp. 18.0–18.3. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Sandven P. Laboratory identification and sensitivity testing of yeast isolates. Acta Odontol Scand. 1990;48:27–36. doi: 10.3109/00016359009012731. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Sandven P, Bjorneklett A, Maeland A. Susceptibilities of Norwegian Candida albicans strains to fluconazole: emergence of resistance. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1993;37:2443–2448. doi: 10.1128/aac.37.11.2443. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Wenzel R P. Nosocomial candidemia: risk factors and attributable mortality. Clin Infect Dis. 1995;20:1531–1534. doi: 10.1093/clinids/20.6.1531. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]