Abstract

Determination of the G and P serotypes of group A bovine rotaviruses from 149 samples of feces or intestinal contents collected from calves showing clinical signs of neonatal diarrhea was performed by a nested reverse transcription-PCR typing assay. The G6 serotype was the most prevalent, accounting for viruses in 55.7% of the samples; viruses of the G10 and G8 serotypes were found in 34.9 and 4.7% of the samples, respectively. The virus in one sample (0.7%) was not classified due to concomitant infection with G6 and G8 strains, whereas viruses in six samples (4.0%) could not be characterized with any of the three G serotype-specific primers selected for the present study. When examined for their P-serotype specificities, viruses in 55 and 42.3% of the samples were characterized as P[11] and P[5], respectively, no P[1] serotype was identified, and viruses in 2.7% of the samples could not be classified due to multiple reactivity with both P[5]- and P[11]-specific primers. Various combinations of G and P serotypes were observed, the most frequent being G6,P[5] (38.3%), G10,P[11] (31.5%), and G6,P[11] (15.4%). The results of the present study, while contributing to a better understanding of the epidemiology of bovine rotaviruses in Italy, address the relevance of serotype specificity with regard to the constancy of the quality of bovine rotavirus vaccines under different field conditions.

Group A bovine rotaviruses (BRVs) are among the enteropathogenic agents more commonly associated with neonatal diarrhea in calves (19). Recent investigations have addressed the relevance of serotype classification of field isolates as a critical marker for any epidemiological survey (1, 15). The specificities of virus strains have been defined by the independent neutralizing activities of antibodies to outer capsid proteins VP7 and VP4, which characterize the G and P serotypes, respectively (4). So far, serological assays, such as virus neutralization assays or enzyme-linked immunosorbent assays (ELISAs) with monoclonal antibodies, have been widely used for the classification of the G and P serotypes of BRV strains (10, 16, 18). Nevertheless, large-scale application of these methods is hampered by technical difficulties, including the availability of a complete panel of antibodies and some intrinsic limits of the methods themselves (21, 24).

Molecular methods such as methods that use specific probes (13, 17) or type-specific PCR primers (8, 14) and restriction endonuclease analysis (1, 6, 11) have been shown to be a solution to the disadvantages encountered by serological methods and, in recent years, have largely been used in epidemiological studies carried out worldwide.

Field surveys have demonstrated that, so far, G6 and G10 are the most prevalent G serotypes among calf strains worldwide, whereas G8 is the least common serotype worldwide (1, 17, 18). According to the available evidence, P[5] and P[11] represent the most common P serotypes occurring in cattle; conversely, P[1] strains have very rarely been detected in the field (1, 17).

Only limited data are available on the epidemiology of BRV strains in Italy, and even more restricted observations have been reported regarding the serotype specificities of field isolates in Italy.

The aim of the present study is to provide supporting information on the prevalence of G and P serotypes and G- and P-serotype combinations in the field. This is the first report on G- and P-serotype characterization by PCR technology of group A BRVs from infected calves in Italy.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Viruses.

The well-characterized cell culture-adapted BRV strains NCDV (G6,P[1]), UK (G6,P[5]), B223 (G10,P[11]), and 678 (G8,P[5]) (3) were used to confirm the specificity of the reverse transcription-PCR (RT-PCR) typing assay.

Viruses were pretreated with 10 μg of acetylated trypsin (type V-S from bovine pancreas; Sigma) per ml at 37°C for 60 min. Viruses were propagated on the African monkey kidney cell line MA 104 in minimal essential medium (Gibco) in the presence of 1 μg of trypsin per ml and were incubated at 37°C for up to 5 days.

Virus-infected cell cultures were submitted to three cycles of freezing-thawing, and cell debris was removed by centrifugation at 3,000 × g for 5 min; fluid containing each harvested virus was stored at −80°C until needed.

Field samples.

A total of 402 samples of feces or intestinal contents were collected between 1994 and 1998 as part of a routine analysis of field specimens that originated from ill or dead calves with severe diarrhea. The animals were less than 3 weeks of age, and most of them were 5 to 12 days old. The calves were present on dairy and beef farms located in 14 provinces in northern Italy. The herds had never been vaccinated against rotavirus infection.

Detection of group A BRVs was carried out by an immunoenzymatic assay (ELISA) of the sandwich type previously developed for routine diagnostic purposes (2) with a 10% suspension of the suspected materials prepared in double-distilled water.

RNA extraction.

Rotavirus double-stranded RNA (dsRNA) was extracted from virus-infected cell culture fluids and from supernatants of the 149 rotavirus-positive field samples with a commercial RNeasy mini kit (Qiagen, Hilden, Germany) by the manufacturer's recommended procedures. Five rotavirus-negative field samples were included to monitor cross contamination. Briefly, 700 μl of each sample was added to 700 μl of a lysis buffer, followed by the addition of 2 volumes of 70% ethanol. Each mixture was applied to a RNeasy mini spin column. Purified RNA was then eluted in 60 μl of RNase-free water, precipitated in 3 M sodium acetate (pH 5.2) to a final concentration of 0.3 M, and placed in 2.5 volumes of ice-cold ethanol. The extracted dsRNA was stored at −80°C until needed.

Primers.

The specificities of the selected primers used in the present study for the G- and P-typing assays have been evaluated previously (8, 14).

Two distinct pairs of generic primers were used in the RT-PCR to amplify full-length copies of the rotavirus VP7 gene spanning 1,062 bp (Table 1) and a region of 856 bp within the VP4 gene (Table 2), respectively.

TABLE 1.

Oligonucleotide primers used to amplify the full-length VP7 gene and for the G-typing PCR

TABLE 2.

Oligonucleotide primers used to amplify a part of the VP4 gene and for the P-typing PCR

The upstream generic primer on the VP7 gene and three specific G-typing primers (Table 1) were used in a second round of PCR amplification for the characterization of the G6, G8, and G10 serotypes. Similarly, the upstream generic primer on the VP4 gene and three specific P-typing primers (Table 2) were used in a second amplification for the characterization of the P[1], P[5], and P[11] serotypes.

RT-PCR of full-length VP7 and partial-length VP4 genes.

Single RNA preparations were centrifuged at 12,000 × g for 10 min at 4°C, and the pellets were washed with 70% ethanol. The ethanol was removed, and the pellets were dissolved in 60 μl of RNase-free water and used as templates for RT-PCR amplification. Both reactions were performed in a single tube with the Access RT-PCR system (Promega, Madison, Wis.). A total of 30 μl of genomic dsRNA was transferred to a 0.6-ml Eppendorf tube with 1 μl (50pmol) of each of the generic G or P primers, covered with a drop of nuclease-free mineral oil to prevent condensation and evaporation, denatured at 97°C for 5 min, and immediately chilled on ice. The denatured dsRNA was then added to the reaction mixture, consisting of 10 μl of the 5× reaction buffer, 1 μl of a deoxynucleoside triphosphate (dNTP) mixture (each dNTP at a concentration of 10 mM), 2 μl of MgSO4 (25 mM), 1 μl of reverse transcriptase from avian myeloblastosis virus (5 U/μl), 1 μl of DNA polymerase (5 U/μl) from Thermus flavus, and 3 μl of dimethyl sulfoxide in a final volume of 50 μl, and the reaction mixture was overlaid with 80 μl of mineral oil (Sigma). Each sample was preincubated in a thermal cycler (model 480; Perkin-Elmer Europe B.V., Monza, Italy) at 48°C for 45 min. The first round of amplification of full-length VP7 consisted of 39 cycles of 1 min at 94°C, 2 min at 46°C, and 3 min at 68°C, followed by a final incubation at 68°C for 10 min. A similar RT-PCR was performed to amplify partial-length VP4, with the exception that the annealing temperature was set at 48°C.

Determination of G serotype.

RT-PCR products were submitted to a second round of amplification by a modification of a previously described method (8). An aliquot of 2 μl of undiluted or diluted (1:100) DNA products was added to a reaction mixture consisting of 6 μl of MgCl2 (25 mM), 2 μl of each dNTP (10 mM), 10 μl of PCR buffer II (100 mM Tris-HCl [pH 8.3], 500 mM KCl), 0.5 μl of AmpliTaq Gold DNA polymerase (5 U/μl; Perkin-Elmer Europe B.V.), 1 μl (50 pmol) of VP7 upstream primer, 1 μl (50 pmol) of each primer specific for the G6, G8, and G10 serotypes, and RNase-free water to a final volume of 100 μl. Each sample was overlaid with 80 μl of mineral oil and was preincubated at 94°C for 10 min to allow activation of the AmpliTaq Gold. The second round of amplification consisted of 25 cycles of 1 min at 94°C, 2 min at 54°C, and 1 min at 72°C, followed by a final incubation at 72°C for 10 min.

Determination of P serotype.

The P-typing assay was performed by adopting the same protocol followed for the characterization of G serotype but with 1 μl (50 pmol) of VP4 upstream primer and 1 μl (50 pmol) of each of P[1] serotype-, P[5] serotype-, and P[11] serotype-specific primers and by modification of the annealing temperature, which was set at 52°C.

Analysis and detection of products.

PCR products were analyzed on a 1.5% agarose gel containing ethidium bromide (0.5 μg/ml) in Tris-borate-EDTA buffer.

RESULTS

In this study, 149 of 402 field samples collected from animals involved in outbreaks of neonatal calf diarrhea in dairy and beef herds in northern Italy between 1994 and 1998 were found to be positive for group A BRVs by a specific ELISA developed for routine diagnostic purposes (2). Further characterization of the G and P serotypes of the rotavirus-positive samples was carried out by a nested RT-PCR typing assay.

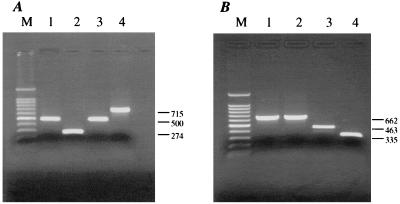

The test was validated each time by comparing the results obtained from serotyping of field samples with the well-characterized G- and P-serotype specificity of each of the prototype BRV strains listed in Materials and Methods. Amplified DNA fragments from G6, G8, and G10 reference strains resulted in the expected bands of 500, 274, and 715 bp, respectively (Fig. 1A). Amplified DNA fragments associated with P[1], P[5], and P[11] virus strains showed the expected sizes of 463, 662, and 335 bp, respectively (Fig. 1B).

FIG. 1.

PCR typing of four representative bovine rotavirus strains. Lanes: M, 100-bp marker with highlighted 500-bp segment; 1, UK (G6,P[5]); 2, 678 (G8,P[5]); 3, NCDV (G6,P[1]); 4, B223 (G10,P[11]). (A) G-typing assay. (B) P-typing assay. Sizes (in base pairs) of the characteristic amplified products are indicated at the right.

Accordingly, the G and P serotypes of the 149 field samples were defined on the basis of the different migration patterns of the PCR products, as reported in Table 3.

TABLE 3.

Relative frequencies of various combinations of the G and P serotypes observed in BRV field isolates in Italy

| Serotype | No. (%) of isolates

|

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| P[1] | P[5] | P[11] | P[5] + P[11] | Total | |

| G6 | 0 (0) | 57 (38.3) | 23 (15.4) | 3 (2.0) | 83 (55.7) |

| G8 | 0 (0) | 2 (1.3) | 5 (3.4) | 0 (0) | 7 (4.7) |

| G10 | 0 (0) | 4 (2.7) | 47 (31.5) | 1 (0.7) | 52 (34.9) |

| G6 + G8 | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 1 (0.7) | 0 (0) | 1 (0.7) |

| G positive (untypeable) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 6 (4.0) | 0 (0) | 6 (4.0) |

| Total | 0 (0) | 63 (42.3) | 82 (55) | 4 (2.7) | 149 (100) |

The G types were identified in 95.3% of the rotavirus-positive field samples, the P types were identified in 97.3% of the samples, and both G and P types were identified in 92.6% of the samples. G-typing analysis revealed that 55.7% (83 of 149) of the isolates were G6, 34.9% (52 of 149) were G10, and 4.7% (7 of 149) were G8. The G type was not determined for seven samples (4.7%). The concomitant presence of both G6 and G8 was detected in one field isolate (0.7%). Following a successful RT-PCR, six samples (4.0%) failed to hybridize with any of the three G type-specific primers used.

P typing indicated that 55% (82 of 149) of the isolates were P[11] and that 42.3% (63 of 149) were P[5]. No field sample was found to contain an isolate of the P[1] type. As a consequence of dual reactivity with the P[5]- and P[11]-specific primers, the univocal determination of P-serotype specificity was not possible for four samples (2.7%).

The various combinations of G and P types found in the present study are reported in Table 3. The G6,P[5] combination was predominant (38.3%) over the G10,P[11] (31.5%), G6,P[11] (15.4%), G8,P[11] (3.4%), G10,P[5] (2.7%), and G8,P[5] (1.3%) combinations. No segregation of any G type with P[1] type was recorded.

Given the serotypic diversity of the rotavirus strains found among cattle, it seemed that it would be interesting to investigate the serotype compositions of the three BRV vaccines currently available in Italy. With the exception of the well-characterized composition of the NCDV-Lincoln strain (G6,P[1]) present in one of them, the identities of the BRV components of the other two vaccines were not known when this study was initiated. The RT-PCR typing assay described earlier was then performed to identify the vaccine strains, the first directly from the master seed vaccine virus and the second from a batch of finished product. The test materials were provided directly from the manufacturers of the two products; additional primers specific for G1 (7) and G5 (8) serotypes were included in the assay. The BRV vaccine strains were characterized as G6,P[5] and G5,P[1], respectively.

DISCUSSION

The serotype specificities of field isolates and, consequently, the availability of reliable diagnostic tools have, nowadays, become of primary relevance to the development of appropriate systems of epidemiological surveillance and control of BRV infection.

In this context, the limitations of existing serological assays are well recognized, while molecular techniques, such as PCR assays, have become widely accepted as the assay of choice for the fast and complete characterization of field isolates (12, 23). PCR assays are particularly useful for specimens in which degradation of the outer virion capsid has occurred or when, as in the case of P serotyping, the serological assays are hampered by the lack of a complete panel of monoclonal antibodies (9).

As further proof of these points, in the present study, PCR was used to amplify the BRV VP7 gene and a part of the VP4 gene directly from the feces or intestinal contents of infected calves and to identify specific serotypes of the BRV strains. The simplified procedure of RNA extraction and the use of a second amplification, which allowed the simultaneous detection of different serotypes, resulted in increased sensitivity and in the rapid characterization of the isolates in a large number of field samples.

Although the availability of more epidemiological data would have been beneficial in the attempt to establish a correlation between the predominance of individual G and P serotypes with the geographical, temporal, and clinical occurrence of rotavirus infection, the accuracy of the molecular study performed represents a substantial contribution in this respect.

Previous reports have shown that a large majority of strains are of the G6 and G10 serotypes and the P[5] and P[11] serotypes (1, 17, 20). The results obtained in the present study support the evidence that a relatively restricted number of BRV serotypes is prevalent in the field and that G6 and G10 are predominant among the cattle population in Italy as well. As already demonstrated by similar epidemiological surveys, G8 viruses represent the third most common G serotype among field isolates (1, 17, 18).

Interestingly, P[11] viruses were more frequently detected than P[5] viruses compared to the frequency with which they were detected in other studies (1, 17, 20). Such a serotype diversity could contribute to a definition of the geographical differences in the distribution of BRV strains in the field.

The G- and P-serotype combinations most commonly found in the present study were G6,P[5] and G10,P[11]. The frequency of G10,P[11] (31.5%) was relatively higher with respect to values reported from similar studies (1, 15, 20).

Evidence for the independent segregation of the VP7 and VP4 genes, which has been widely reported in literature (1, 20, 22), delineates the magnitude of the occurrence, in nature, of genetic reassortment among BRV strains characterized by different G and P serotypes. The data presented here show a preferential segregation of G6 with the P[5] serotype and of G10 with the P[11] serotype, accounting for 71 and 92% of G6 and G10 strains, respectively.

In the present study, the accuracies of the G- and P-typing analyses performed also resulted in a very limited number of untyped strains. This number is extremely low compared to the number obtained in similar surveys (10, 17). With the exclusion of those field samples showing multiple reactivity against G- or P-specific primers, only six virus strains could not be typed with the G-specific primers selected. Analogous findings have been explained by sequence variations, which commonly occur in RNA viruses, or by the emergence of novel serotypes (13, 17). No further reactivity became evident after additional primers specific for the G5 serotype were included in the assay; conversely, preliminary data obtained from the sequence analysis of VP7 genes from the six untyped strains allowed the classification of at least two of these strains as being of the G6 serotype (data not shown). The failure to hybridize with the G serotype-specific primers might be due to sequence variations in the pairing region.

The key advantage of serotype classification and definition of the antigenic diversity of BRVs is the possibility of assessing the specificity of vaccine virus protection and monitoring the field use of vaccines. Marked antigenic differences between field viruses and those strains of viruses used for vaccine production raise important questions concerning the implications of such variations for BRV control. It is widely recognized that, under field conditions, the efficacies of vaccines against BRV correlate with the induction of high levels of virus-neutralizing antibodies which neutralize, via the colostrum or milk of vaccinated cows, field viruses in passively immunized newborn calves. A maximal homotypic response is raised only against the serotypes present in the vaccine, while lower levels of virus-neutralizing antibodies are induced against different G and P serotypes. In this respect, the higher the degree of homology of the G and P serotypes of a vaccine strain(s) with those of field viruses, the higher the likelihood that the efficacy of the vaccine in the field will be predicted. Conversely, the protective effect of heterotypic immunity cannot be anticipated from the vaccine serotype composition, since the levels of preexisting antibody against a particular serotype have a practical impact on such a phenomenon. Consequently, the identities of G and P serotypes should be provided in order to assess the consistency and the quality of BRV vaccines.

On the basis of the serotypes covered by the three vaccines used in Italy, whereas G6,P[5] and G6,P[1] vaccine strains can be expected to have satisfactory efficacies, the success of field application of the G5,P[1] vaccine strain is highly questionable.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank D. Snodgrass, Edinburgh, United Kingdom, and G. Gerna, Pavia, Italy, for providing the laboratory strains used in the present study.

REFERENCES

- 1.Chang K O, Parwani A V, Saif L J. The characterization of VP7 (G type) and VP4 (P type) genes of bovine group A rotaviruses from field samples using RT-PCR and RFLP analysis. Arch Virol. 1996;141:1727–1739. doi: 10.1007/BF01718295. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Cordioli P, Lavazza A. Comparison between ELISA test and immunoelectronmicroscopic methods for the detection of rota and coronavirus in faeces of calves. Atti Soc Ital Buiatria. 1992;XXIV:521–526. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Estes M K. Rotaviruses and their replication. In: Fields B N, Knipe D M, Howley P M, editors. Fields virology. 3rd ed. Philadelphia, Pa: Lippincott-Raven Publishers; 1996. pp. 1625–1655. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Estes M K, Cohen J. Rotavirus gene structure and function. Microbiol Rev. 1989;53:410–449. doi: 10.1128/mr.53.4.410-449.1989. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Glass R I, Keith J, Nakagomi O, Nakagomi T, Askaa J, Kapikian A Z, Chanock R M, Flores J. Nucleotide sequence of the structural glycoprotein VP7 gene of Nebraska calf diarrhea virus rotavirus: comparison with homologous genes from four strains of human and animal rotaviruses. Virology. 1985;141:292–298. doi: 10.1016/0042-6822(85)90260-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Gouvea V, Ramirez C, Li B, Santos N, Saif L, Clark H F, Hoshino Y. Restriction endonuclease analysis of the VP7 genes of human and animal rotaviruses. J Clin Microbiol. 1993;31:917–923. doi: 10.1128/jcm.31.4.917-923.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Gouvea V, Glass R I, Woods P, Taniguchi K, Clark H F, Forrester B, Fang Z. Polymerase chain reaction amplification and typing of rotavirus nucleic acid from stool specimens. J Clin Microbiol. 1990;28:276–282. doi: 10.1128/jcm.28.2.276-282.1990. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Gouvea V, Santos N, Timenetsky M do C. Identification of bovine and porcine rotavirus G types by PCR. J Clin Microbiol. 1994;32:1338–1340. doi: 10.1128/jcm.32.5.1338-1340.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Heath R, Birch C, Gust I. Antigenic analysis of rotavirus isolates using monoclonal antibodies specific for human serotypes 1, 2, 3 and 4, and SA11. J Gen Virol. 1986;67:2455–2466. doi: 10.1099/0022-1317-67-11-2455. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hussein A H, Cornaglia E, Saber M S, El-Azhary Y. Prevalence of serotypes G6 and G10 group A rotaviruses in dairy calves in Quebec. Can J Vet Res. 1995;59:235–237. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hussein H A, Frost E H, Deslandes S, Talbot B, Elazhary Y. Restriction endonucleases whose sites are predictable from the amino acid sequence offer an improved strategy for typing bovine rotaviruses. Mol Cell Probes. 1997;11:355–361. doi: 10.1006/mcpr.1997.0128. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hussein H A, Frost E, Talbot B, Shalaby M, Cornaglia E, El-Azhary Y. Comparison of polymerase chain reaction and monoclonal antibodies for G-typing of group A bovine rotavirus directly from fecal material. Vet Microbiol. 1996;51:11–17. doi: 10.1016/0378-1135(95)00202-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hussein H A, Parwani A V, Rosen B I, Lucchelli A, Saif L J. Detection of rotavirus serotypes G1, G2, G3, and G11 in feces of diarrheic calves by using polymerase chain reaction-derived cDNA probes. J Clin Microbiol. 1993;31:2491–2496. doi: 10.1128/jcm.31.9.2491-2496.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Isegawa Y, Nakagomi O, Nakagomi T, Ishida S, Uesugi S, Ueda S. Determination of bovine rotavirus G and P serotypes by polymerase chain reaction. Mol Cell Probes. 1993;7:277–284. doi: 10.1006/mcpr.1993.1041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ishizaki H, Sakai T, Shirahata T, Taniguchi K, Urasawa T, Urasawa S, Goto H. The distribution of G and P types within isolates of bovine rotavirus in Japan. Vet Microbiol. 1996;48:367–372. doi: 10.1016/0378-1135(95)00168-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Matsuda Y, Nakagomi O, Offit P A. Presence of three P types (VP4 serotypes) and two G types (VP7 serotypes) among bovine rotavirus strains. Arch Virol. 1990;115:199–207. doi: 10.1007/BF01310530. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Parwani A V, Hussein H A, Rosen B I, Lucchelli A, Navarro L, Saif L J. Characterization of field strains of group A bovine rotaviruses by using polymerase chain reaction-generated G and P type-specific cDNA probes. J Clin Microbiol. 1993;31:2010–2015. doi: 10.1128/jcm.31.8.2010-2015.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Snodgrass D R, Fitzgerald T, Campbell I, Scott F M M, Browning G F, Miller D L, Herring A J, Greenberg H B. Rotavirus serotypes 6 and 10 predominate in cattle. J Clin Microbiol. 1990;28:504–507. doi: 10.1128/jcm.28.3.504-507.1990. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Snodgrass D R, Terzolo H R, Sherwood D, Campbell I, Menzies J D, Synge B A. Aetiology of diarrhoea in young calves. Vet Rec. 1986;12:31–34. doi: 10.1136/vr.119.2.31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Suzuki Y, Sanekata T, Sato M, Tajima K, Matsuda Y, Nakagomi O. Relative frequencies of G (VP7) and P (VP4) serotypes determined by polymerase chain reaction assays among Japanese bovine rotaviruses isolated in cell culture. J Clin Microbiol. 1993;31:3046–3049. doi: 10.1128/jcm.31.11.3046-3049.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Taniguchi K, Urasawa T, Morita Y, Greenberg H B, Urasawa S. Direct serotyping of human rotavirus in stools by an enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay using serotype 1-, 2-, 3-, and 4-specific monoclonal antibodies to VP7. J Infect Dis. 1987;155:1159–1166. doi: 10.1093/infdis/155.6.1159. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Taniguchi K, Urasawa T, Urasawa S. Independent segregation of the VP4 and the VP7 genes in bovine rotaviruses as confirmed by VP4 sequence analysis of G8 and G10 bovine rotavirus strains. J Gen Virol. 1993;74:1215–1221. doi: 10.1099/0022-1317-74-6-1215. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Taniguchi K, Wakasugi F, Pongsuwanna Y, Urasawa T, Ukae S, Chiba S, Urasawa S. Identification of human and bovine rotavirus serotypes by polymerase chain reaction. Epidemiol Infect. 1992;109:303–312. doi: 10.1017/s0950268800050263. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Urasawa S, Urasawa T, Taniguchi K, Wakasugi F, Kobayashi N, Chiba S, Sakurada N, Morita M, Morita O, Tokieda M, Kawamoto H, Minekawa Y, Ohseto M. Survey of human rotavirus serotypes in different locales in Japan by enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay with monoclonal antibodies. J Infect Dis. 1989;160:44–51. doi: 10.1093/infdis/160.1.44. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]