Abstract

Sexual and reproductive health and rights (SRHR) are an essential component of universal health coverage (UHC). In determining which SRHR interventions to include in their UHC benefits package, countries are advised to evaluate each service based on robust and reliable data, including cost-effectiveness data. We conducted a scoping review of full economic evaluations of the essential SRHR interventions included in the comprehensive package presented by the Guttmacher-Lancet Commission on SRHR. Of the 462 economic evaluations that met the inclusion criteria, the quantity of publications varied across regions, countries, and the components of the SRHR package, with the majority of publications reporting on HIV/AIDS, reproductive cancer, as well as antenatal care, childbirth, and postnatal care. Systematic reviews are needed for these components in support of more conclusive findings and actionable recommendations for programmes and policy. Further evaluations for interventions included in the remaining components are needed to provide a stronger evidence base for decision-making. The economic evaluations reviewed for this article were inherently varied in their applied methodologies, SRHR interventions and comparators, cost and effectiveness data, and cost-effectiveness thresholds, among others. Despite these differences, the vast majority of publications reported the evaluated SRHR interventions to be cost-effective.

Keywords: sexual and reproductive health and rights, universal health coverage, health benefits package, economic evaluation, cost-effectiveness, lower- and middle-income countries, scoping review

Résumé

La santé et les droits sexuels et reproductifs sont un élément essentiel de la couverture santé universelle (CSU). Lorsque les pays déterminent quelles interventions de santé sexuelle et reproductive inclure dans leur panier de prestations de la CSU, on leur conseille d’évaluer chaque service sur la base de données robustes et dignes de foi, notamment sur le rapport coût-efficacité. Nous avons mené un examen de la portée des évaluations économiques des interventions essentielles de santé sexuelle et reproductive (SSR) incluses dans le panier global présenté par la Commission Guttmacher-Lancet sur la santé et les droits sexuels et reproductifs. Sur les 462 évaluations économiques qui réunissaient les critères d’inclusion, la quantité des publications différait selon les régions, les pays et les éléments du panier de SSR, la majorité des publications rendant compte du VIH/sida, des cancers des organes reproducteurs, ainsi que des soins prénatals, obstétriques et postnatals. Des analyses systématiques sont nécessaires pour ces éléments, à l’appui de résultats plus concluants et de recommandations pouvant être appliquées par les programmes et les politiques. D’autres évaluations des interventions incluses dans les éléments restants sont requises pour donner une base factuelle plus solide à la prise de décision. Les évaluations économiques étudiées pour cet article étaient en nature variées dans leurs méthodologies appliquées, les interventions de SSR et les comparateurs, les données sur le coût et l’efficacité, ainsi que les seuils des rapports coût-efficacité, entre autres facteurs. En dépit de ces différences, la grande majorité des publications ont indiqué que les interventions de SSR évaluées étaient d’un bon rapport coût-efficacité.

Resumen

La salud y los derechos sexuales y reproductivos (SDSR) son un componente esencial de la cobertura universal de salud (CUS). Se aconseja a los países que, para determinar qué intervenciones de SDSR incluir en su paquete de beneficios de CUS, evalúen cada servicio basándose en datos robustos y fidedignos, incluidos los datos de costo-eficacia. Realizamos una revisión de alcance de todas las evaluaciones económicas de las intervenciones de SDSR esenciales incluidas en el paquete integral presentado por la Comisión de Guttmacher-Lancet en SDSR. De las 462 evaluaciones económicas que reunieron los criterios de inclusión, la cantidad de publicaciones varió por región, país y los componentes del paquete de SDSR; la mayoría de las publicaciones informaron sobre VIH/SIDA, cáncer reproductivo, así como atención prenatal, parto y atención posnatal. Se necesitan revisiones sistemáticas de estos componentes para apoyar hallazgos más concluyentes y recomendaciones accionables para programas y políticas. Además, se necesitan más evaluaciones de las intervenciones incluidas en los demás componentes a fin de proporcionar una base de evidencia más convincente para la toma de decisiones. Las evaluaciones económicas revisadas para este artículo variaron inherentemente en sus metodologías aplicadas, intervenciones de SDSR y comparadores, datos de costos y eficacia, y umbrales de costo- eficacia, entre otros. A pesar de estas diferencias, la gran mayoría de las publicaciones informaron que las intervenciones de SDSR evaluadas son costo eficaces.

Introduction

Since the International Conference on Population and Development (ICPD) in 1994, the world has made considerable progress in reducing sexual and reproductive health (SRH)-related morbidities and mortalities. For instance, maternal mortality, child marriages, HIV infections, and AIDS-related deaths have declined considerably, while access to family planning (FP), antenatal care (ANC), skilled birth attendance, and human papilloma virus (HPV) vaccination have increased.1 Despite these successes, there has been limited progress on significant issues. There is limited access to safe abortion services in many countries and interventions addressing infertility and high prevalence of sexual and gender-based violence (SGBV), sexually transmitted infections (STIs), and cervical cancer need to be scaled up.1,2 Additionally, progress has been highly inequitable both among and within countries. Poor and near-poor people in low- and middle-income countries (LMICs) continue to be the most affected by substandard SRH services and outcomes.1,2

The UN high-level meeting on Universal Health Coverage (UHC) and the 25th anniversary of the ICPD in 2019 galvanised political will and public support for advancing the inextricably linked UHC and SRHR agendas. To accelerate progress on these targets, the Guttmacher-Lancet Commission on SRHR put forward a comprehensive package of essential SRHR interventions (hereinafter referred to as the SRHR package) and emphasised the importance of adopting a holistic view of SRHR and tackling hitherto neglected issues (Supplementary Table S1). The Commission clearly highlighted the potential for significant social and economic benefits that can be realised by countries that expand access to SRHR interventions for their populations,1 and a 2019 paper on universal access to SRHR within UHC reiterated these findings.3

In keeping with the concept of progressive universalism underpinning UHC, countries are encouraged to gradually implement the SRHR package by adopting a stepwise expansion of interventions included in their UHC health benefits packages (HBPs).1,3,4 In doing so, policymakers face the critical choice of deciding which services to expand first, and which criteria to use for ranking and prioritising interventions. The World Health Organization suggests starting with cost-effectiveness estimates, which is reflected in the fact that efficiency, including the prioritisation of cost-effective services, was defined as a key intermediate policy objective for UHC.5,6 Cost-effectiveness analysis (CEA) has become widespread and influential, offering a practical approach to the prioritisation problem, and forms part of the foundation of evidence-based and transparent HBP processes.7 Nevertheless, in making decisions about the inclusion of services, policymakers need to augment CEA with equitable access to SRHR services for those least able to access services, and with minimum standards for a rights-based UHC HBP.1,7,8

However, a comprehensive review on the cost-effectiveness of the interventions included in the SRHR package has not yet been conducted. With LMICs moving towards UHC, there is an opportunity for such a review to inform priority setting, the development of countries’ HBPs inclusive of prioritised SRHR interventions, and thus the expansion of service coverage. To address this gap, we conducted a scoping review, mapping what is known from the existing literature about the cost-effectiveness of the essential interventions that form part of the comprehensive approach to SRHR presented by the Commission. More specifically, we sought to summarise the relevant available SRHR cost-effectiveness evidence, identify current research gaps, and draw conclusions regarding the overall evidence base of this field.

Methods

Study design

This scoping review followed the Joanna Briggs Institute reviewer’s manual, the five-stage framework presented by Arksey and O’Malley and ensuing recommendations made by Khalil et al., and adheres to the PRISMA extension for scoping reviews for reporting purposes.9–12 The objectives, inclusion criteria and methods for this review were specified in a study protocol (available from the authors upon request). This form of synthesis is aimed at mapping key concepts, types of research and gaps in evidence within a defined area by systematically searching, selecting, and summarising existing knowledge.11,13 It is of particular use when a body of literature has not yet been comprehensively reviewed or exhibits a heterogeneity not immediately amenable to the narrow synthesis typical of a systematic review.11,13

Search strategy and selection criteria

To identify all published economic evaluations of interventions included in the SRHR package, we systematically and comprehensively searched Medline (via PubMed), Embase, and the CEVR GH CEA registry on 20 April 2020 (last updated on 16 August 2020). We used the PRESS 2015 Guideline Statement to guide the development of the search strategies, using combinations of the search terms illustrated in Supplementary Table S2.14 Google, Google Scholar, and websites of selected organisations and agencies were searched (Supplementary Table S3). The reference lists of reviews identified through database searching were screened for additional relevant studies and to identify any non-indexed published literature or grey literature. Publications were included if they were full-text studies written in English; published between 1994 and August 2020; conducted in the 67 LMICs included in the WHO SDG Health Price Tag model;15 reported full economic evaluations of interventions included in the SRHR package;1 and provided a measure that combines cost and health effect (incremental cost-effectiveness ratio (ICER) or benefit–cost ratio) compared with a clear alternative. We restricted the study scope to the 67 countries included in the WHO model since these jointly account for 95% of the population in LMICs and bear a disproportionately higher burden of poor SRH outcomes.1,15 Full economic evaluations form part of a group of methods that measure the efficiency of interventions in achieving desired outcomes and can be categorised as CEAs, cost-utility analyses (CUAs), and cost–benefit analyses (CBAs). While all three measure costs in monetary units, the main distinction between the evaluation designs relates to the choice of outcome measure. In CEAs, the effect is measured in natural units (e.g. life-years gained, number of safe deliveries, or HIV infections averted). CUAs measure consequences with a generic health outcome (such as quality-adjusted life years (QALYs) or disability-adjusted life years (DALYs)). Lastly, in CBAs, benefits are monetised and expressed as a monetary value.16 Selection criteria are listed in Supplementary Table S4.

The records retrieved through database searching were imported into the web-based systematic review software Rayyan and duplicates were removed. Using a title and abstract screening form developed a priori by the review team, two reviewers (AHK, MD) subsequently independently screened titles and abstracts to identify potentially relevant publications; titles for which an abstract was not available and records whose relevance was unclear were retained for full-text review. All full-text publications were assessed independently by the two reviewers to ensure correct inclusion. Disagreements between reviewers were resolved through discussion.

Data charting, collation, summarising, and reporting results

We adopted a descriptive-analytical approach to collate, summarise, and report the findings, which entailed applying a common analytical framework and recording standard data on each evaluation.10 We abstracted data onto a standardised charting tool using Microsoft Excel to capture key intervention and evaluation characteristics to inform the review objectives, including publication year, study design(s), outcome measure(s), setting, details of SRHR interventions compared, target population(s), cost-effectiveness threshold(s), and cost-effectiveness results. Two members of the review team pilot-tested the charting tool on four publications to ensure all relevant information was captured; data were then charted by one reviewer (AHK) and independently cross-checked by a second reviewer (MD), with discrepancies resolved through discussion. Since quality assessment does not form part of the scoping study remit,10 no such assessment was conducted. The information captured by the data charting process guided the data summarising process. Aligned specifically with the objectives of this review, we conducted a descriptive numerical analysis of the extent, nature, and distribution of the included publications, and mapped the review findings by a diagrammatic and tabular presentation, accompanied by a descriptive summary.

Results

Search and selection of publications

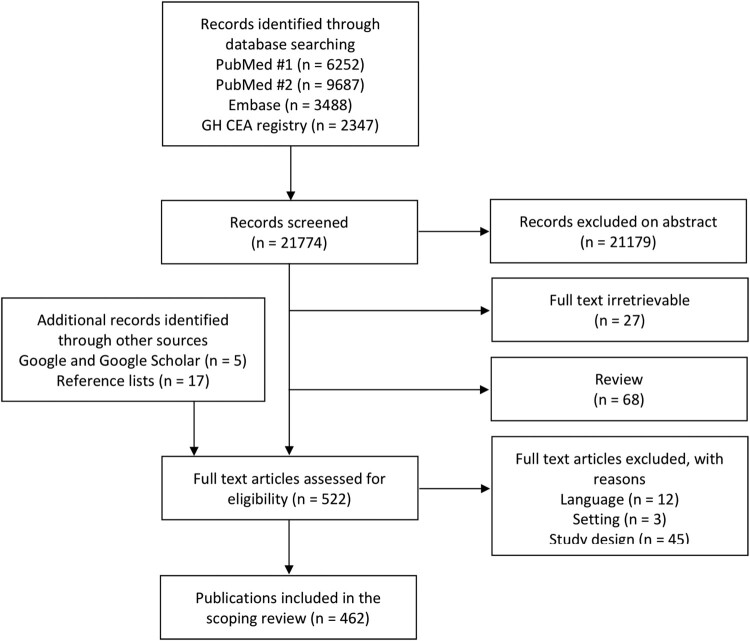

Electronic database searching yielded 21,774 potentially relevant citations. After a deduplication and relevance screening, 595 citations met the eligibility criteria based on title and abstract. An additional 17 publications were identified following a manual searching of the reference lists of the 68 identified reviews, with another five added using Google Search. Excluding the 27 citations without an obtainable full-text article, we reviewed 522 publications at the full-text review stage. In total, we included 462 publications in the scoping review. Figure 1 illustrates further details of the literature screening process.

Figure 1.

Flow diagram for selection of publications

Adapted from Tricco et al.12

General characteristics of the publications

Selected general characteristics of included publications are reported in Table 1; the full list of publications is provided in Supplementary Table S5. The number of publications reporting economic evaluations of SRHR interventions has steadily increased since 1994, with the majority (n = 348) published since 2011. Publications comprise almost exclusively articles from peer-reviewed journals (n = 459). There were differences in the number of publications for the WHO epidemiological regions spanning the 67 countries defined as study scope (Supplementary Table S6); the largest number of publications reported on evaluations conducted in the East and Southern African Region (n = 181), followed by the Western Pacific Region (n = 59), and the South-East Asia Region (n = 55). Sixty publications included evaluations conducted in multiple regions, and close to one fifth (n = 77) reported evaluations conducted for multiple countries.

Table 1.

General characteristics of included publications (n = 462)

| Number | Percentage | |

|---|---|---|

| Publication year | ||

| Up to 2000 | 9 | 2 |

| 2001–2010 | 105 | 23 |

| 2011–2020 | 348 | 75 |

| Publication type | ||

| Journal article | 459 | 99 |

| Grey literature report | 3 | 1 |

| Scope | ||

| Single-country analysis | 385 | 83 |

| Multi-country analysis | 77 | 17 |

| Multiple regions | 60 | 13 |

NB: For the year 2020, publications published until 20 August were included.

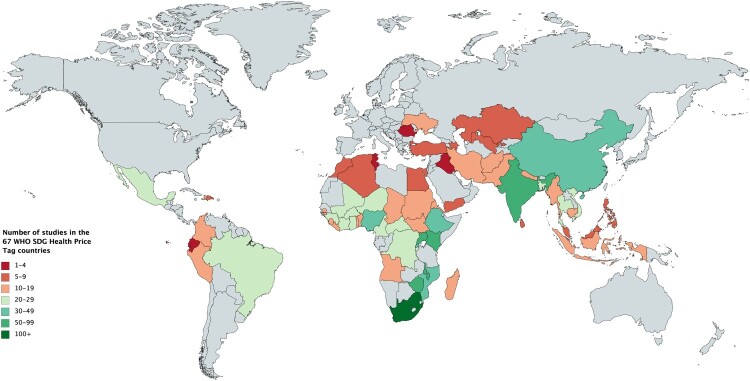

Disaggregating the multi-country analyses into the reported country-specific analyses resulted in 1445 separate evaluations. Figure 2 illustrates the breakdown of evaluations across countries; the number of evaluations for each country is listed in Supplementary Table S7. The geographical disaggregation indicates marked variation between countries, reaching from below five in Ecuador, Iraq, Romania, and Tunisia to above 100 reported evaluations for South Africa. Except for India and China, all countries for which more than 30 evaluations were reported are located in the WHO African region.

Figure 2.

Geographical distribution of the economic evaluations reported in the included publications

Abbreviations: SDG, sustainable development goal; WHO, World Health Organization.

Methodological characteristics of included publications

Of the 462 publications included in the scoping review, 377 provided results from economic evaluations using decision-analytic modelling (Markov models, decision trees, individual sampling models) (Table 2). The majority of publications (n = 199, 43%) reported CEAs, 181 (39%) CUAs using QALYs or DALYs as a measure of health gain, six CBAs (1%), and two extended CEAs (<1%). Seventy (15%) provided results of both CEAs and CUAs, one reported a CEA and CBA (<1%), and three provided CUAs and CBAs. A wide range of outcome measures were used to report the cost-effectiveness of the evaluated interventions, with many studies reporting more than one outcome within one evaluation (e.g. HIV infections averted, life-years gained, and QALYs). The most common single outcome measures were DALY, followed by QALY for CUAs and life-year saved, life-year gained, and HIV infection averted for CEAs (data not shown).

Table 2.

Methodological characteristics of included publications (n = 462)

| Number | Percentage | |

|---|---|---|

| Model versus single-based analysis | ||

| Model-based analysis | 377 | 82 |

| Single-based analysis | 85 | 18 |

| Type of economic evaluation | ||

| CEA | 199 | 43 |

| CUA | 181 | 39 |

| CBA | 6 | 1 |

| CEA and CUA | 70 | 15 |

| CEA and CBA | 1 | <1 |

| CUA and CBA | 3 | 1 |

| Extended CEA | 2 | <1 |

Abbreviatons: CBA, cost–benefit analysis; CEA, cost-effectiveness analysis; CUA, cost-utility analysis.

Overview of publications according to SRHR package components

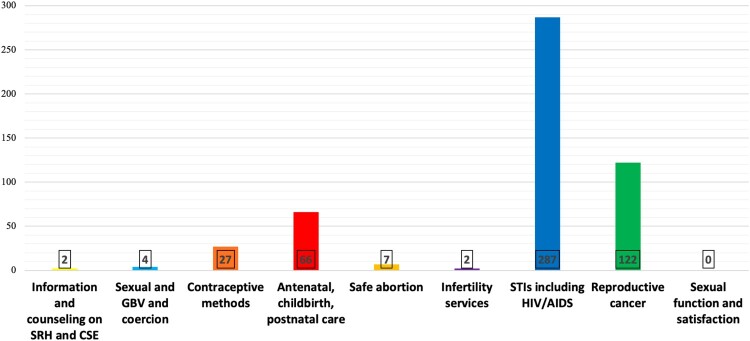

The majority of publications (n = 418) analysed the cost-effectiveness of interventions included in one component of the SRHR package, while the remaining 44 covered interventions of two or more components. Figure 3 illustrates the variations in the number of evaluations conducted for the nine components. The largest number of publications reported evaluations of interventions addressing STIs including HIV/AIDS (n = 287), followed by 122 covering reproductive cancer, 66 for ANC, childbirth and postnatal care (PNC), and 27 for contraceptive methods. An additional four presented analyses of SGBV and coercion and two each provided results for information and counselling on SRH and comprehensive sexuality education (CSE) and infertility services. None reported on sexual function and satisfaction.

Figure 3.

Number of evaluations included within the components of the SRHR package

Abbreviations: CSE, comprehensive sexuality education; SRH, sexual and reproductive health; STIs, sexually transmitted infections; GBV, gender-based violence. NB: Interventions falling into two or more components (e. g. STI testing in ANC, condoms for HIV prevention or modern contraceptives for post-abortion care) have been tagged against all components, thus explaining the higher overall number of economic evaluations in Figure 3 (n = 517) compared to the number of publications included in this scoping review (n = 462). Evaluations of both HIV/AIDS and other STIs were also tagged twice to illustrate the difference in the number of evaluations on HIV/AIDS interventions compared to other STIs.

Further variations were evident upon closer consideration of the evaluations falling within each component. For instance, reproductive cancer comprises 72 publications addressing cervical cancer, and STIs including HIV/AIDS contains 210 publications on HIV/AIDS interventions, 20 addressing HIV and other STIs and only 37 for STIs other than HIV.

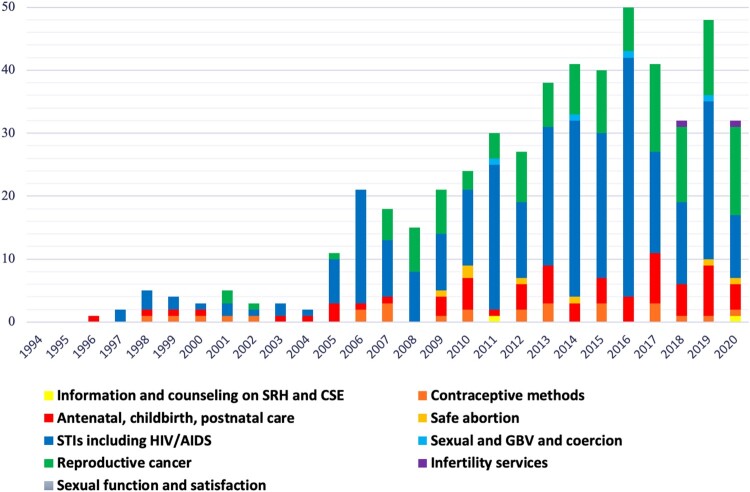

Figure 4 illustrates the annual number of economic evaluations per SRHR package component between 1994 and August 2020. In addition to the increase in the overall number of publications annually, there is a noticeable shift in focus between package components. Publications reporting results of evaluations for contraceptive methods and ANC, childbirth and PNC have been continuously published since 1996, though the annual absolute number of publications for these components has risen only moderately. In contrast, it is only in recent years that evaluations on information and counselling on SRH and CSE, safe abortion, SGBV and coercion, and reproductive cancer have been increasingly published, with the latter taking up a growing share of total publications. The number of publications addressing STIs including HIV/AIDS has been persistently high since 2010, with a peak in 2014–2016.

Figure 4.

Economic evaluations published annually between 1994 and 2000 according to SRHR package component

Abbreviations: CSE, comprehensive sexuality education; SRH, sexual and reproductive health; SRHR, sexual and reproductive health and rights; STIs, sexually transmitted infections; GBV, gender-based violence.

Evidence of cost-effectiveness

Conclusions about whether an intervention is cost-effective are based solely on the results presented by the authors. Given the volume of included publications, the interventions, comparators, costing methodologies, outcomes, and other evaluation characteristics were inherently heterogeneous. There is much controversy around appropriate cost-effectiveness thresholds, and while the majority of evaluations applied gross domestic product as recommended by WHO-CHOICE, this approach has been criticised for not representing the true opportunity cost when interventions are implemented at different scales.17–19 We, therefore, did not conduct a comprehensive synthesis of reported cost-effectiveness results and did not distinguish different levels of cost-effectiveness. The following overview is intended to give a broad indication of the potential cost-effectiveness of the interventions included in the SRHR package. A full list of interventions sorted according to package component and cost-effectiveness results is provided in Supplementary Table S8.

Information and counselling on SRH and CSE (n = 2)

School-based and internet-based sexuality education programmes for adolescents were cost-effective in both publications.

SGBV and coercion (n = 4)

Community mobilisation programmes and a joint economic and health intervention combining microfinance with gender and HIV training were cost-effective in preventing intimate partner violence and violence against female sex workers. Additionally, a parenting programme was cost-effective for preventing abuse of adolescents by their caregivers.

Contraceptive methods (n = 27)

FP with modern methods (e.g. condoms, injectables, implants, oral contraceptives, and vasectomy) was cost-effective across nearly all publications. The most favourable results were reported for countries with high unmet needs and for long-acting methods (e.g. vasectomy and implants).

ANC, childbirth, and PNC (n = 66)

Included publications evaluated a wide range of interventions, almost all of which were cost-effective. Evaluations suggested that participatory interventions with women’s groups, supplementation during pregnancy, reusable medical devices to diagnose pre-eclampsia, surgical obstetric fistula repair, antibiotic prophylaxis for reduced risk of pelvic infections after miscarriage surgery, and maternity waiting homes were cost-effective in preventing and treating maternal complications, while results varied for active management of third-stage labour with oxytocin; prenatal screening for Down’s syndrome was not cost-effective. For emergency obstetrics and neonatal care, emergency caesarean section for obstructed labour (including as part of humanitarian assistance), an ambulance-based referral system, and task-shifting to trained general practitioners were cost-effective. Moreover, mobile health (mHealth) initiatives and voucher schemes for free service utilisation and transport as demand-side interventions, and performance-based financing schemes and conditional cash transfers with strong quality improvement components as supply-side interventions, were cost-effective.

Safe abortion services and care (n = 7)

Safe abortion using dilation and curettage, manual vacuum aspiration (MVA), and vaginal misoprostol was cost-effective across all publications. The most cost-effective methods for first-trimester abortion were clinic-based MVA and medical abortion with misoprostol.

Infertility services (n = 2)

Evaluated infertility services were not cost-effective, including in-vitro fertilisation, intrauterine insemination, and a freeze-only strategy in in vitro fertilisation.

STIs, including HIV/AIDS, and RTIs (n = 287)

The preventive, diagnostic, and curative interventions for both Hepatitis B (HBV) and Hepatitis C (HCV) were overwhelmingly cost-effective across all publications. This included oral antiviral medicines for both forms of hepatitis, an adult community-based screening and treatment programme for HBV and scaling up of awareness-raising, prevention, and treatment as part of a national HCV elimination programme. For HIV prevention interventions, blood screening, condom expansion, harm reduction strategies, prevention of mother-to-child-transmission, social and behaviour change communication, and voluntary medical male circumcision (VMMC) were largely cost-effective, though results varied by setting. The cost-effectiveness of pre-exposure prophylaxis (PrEP) and structural interventions was inconclusive. Diagnosis and appropriate treatment of other STIs, including chlamydia trachomatis, herpes simplex virus-2, Neisseria gonorrhoeae, schistosomiasis, and syphilis, was cost-effective for reducing HIV transmission and disease progression. Furthermore, most HIV testing service modalities, expanding access to first-line antiretroviral therapy (ART) at all CD4+ T-cell counts, ART adherence interventions, and prophylaxis for opportunistic infections were cost-effective. The cost-effectiveness of viral load and CD4+ cell count monitoring was inconclusive. For syphilis, all evaluated interventions were cost-effective (single point-of care (POC) treponemal immunochromatographic strip testing, laboratory-based rapid plasma regain testing, dual POC testing detecting treponemal and nontreponemal antibodies, treatment of infected individuals with benzathine penicillin).

Reproductive cancers (n = 122)

HPV vaccination against infection with two and four different types of HPV (bivalent and quadrivalent vaccines) of pre-adolescent girls prior to sexual initiation to prevent cervical cancer was cost-effective in nearly all country settings analysed. Vaccinating adolescent boys was not cost-effective. Cervical cancer screening with visual inspection with acetic acid (VIA) and VIA followed by cytology one to three times per lifetime was cost-effective in countries within all WHO regions. Provider-collected HPV-DNA testing one to three times per lifetime was also cost-effective, while the cost-effectiveness of HPV self-collection was inconclusive. Only a few publications reporting on cervical cancer treatment were identified, suggesting lesion removal, radiotherapy, chemotherapy, and radical hysterectomy with pelvic lymph node dissection to be cost-effective. For early breast cancer detection, clinical breast examination was cost-effective in all settings, while the results for mammography screening varied greatly. Similarly, results for evaluated breast cancer chemotherapy regimens differed, rendering a statement on their cost-effectiveness impossible. Treatment with lumpectomy, radiotherapy, mastectomy, adjuvant oophorectomy, and tamoxifen were cost-effective. Regarding other forms of reproductive cancer, neoadjuvant chemotherapy in advanced ovarian patients was not cost-effective, while a population-based prostate cancer screening programme was suggested to be cost-effective.

Discussion

In this scoping review, we mapped publications reporting economic evaluations of interventions included within the nine components of the Guttmacher-Lancet package of essential SRHR interventions. The review identified 462 publications across all 67 LMICs included in the WHO SDG Health Price Tag Model.15 The findings highlighted large variations in the scope of the existing cost-effectiveness evidence for the package components, reaching from no single publication of interventions related to sexual function and satisfaction to 287 on interventions addressing STIs including HIV/AIDS. The review results further illustrated differences in the number of evaluations conducted by regions, with almost half conducted for the WHO African region, and by countries, ranging from three evaluations in Tunisia and Ecuador to >100 in South Africa. Additionally, the findings showed a growth trend in cost-effectiveness research over the past 15 years, along with changes in the SRHR components the evaluations focused on.

The reviewed evaluations were inherently heterogeneous with variations in applied methodologies, interventions and comparators, cost and effectiveness data, and cost-effectiveness thresholds, among others. Despite this heterogeneity, the overwhelming majority of publications reported the evaluated interventions to be cost-effective (Supplementary Tables S6 and S8), which is consistent with the results of earlier reports that most SRHR interventions are cost-effective and thus logical investments for countries moving towards UHC.1,3,20 However, the possibility of positive publication bias cannot be ruled out. Additionally, in accordance with scoping review methods, we did not perform a methodological quality appraisal of the included publications.9–11 It is, therefore, not possible to make conclusive statements on the evaluated interventions’ cost-effectiveness or determine whether particular evaluations provide robust or generalisable findings, even for the components with a comparatively large scope of evidence. It is critical for policymakers, programme planners, implementers, activists, and other SRHR stakeholders aiming to realise comprehensive SRHR in UHC to carefully assess the transferability of evaluation results to their contexts and, if required, to gather information and assumptions specific to their context prior to any decision-taking. Additionally, cost-effectiveness evidence should be part of a broader deliberative process to account for the unavoidable uncertainty surrounding model predictions and evidence used.7 Furthermore, systematic reviews including careful methodological quality assessments of included publications using, for instance, the CHEERS statement, are needed.21 This scoping review serves as a useful precursor, clearly identifying the components for which ensuing reviews can be assured of adequate numbers of relevant studies for inclusion. In addition to quantity-related gaps, systematic reviews could also identify evidence gaps in the cost-effectiveness literature related to low-quality research.

The evidence presented by the Guttmacher-Lancet Commission revealed the scope of the unfinished SRHR agenda. The Commission further noted that global health and development initiatives such as the movement towards UHC generally focus on particular areas of SRHR, namely contraception, maternal, and newborn health and HIV/AIDS, while neglecting safe abortion, STIs other than HIV, SGBV, infertility, and sexual satisfaction.1 A similar picture emerged in this scoping review. For interventions included within sexual function and satisfaction; information and counselling on SRH and evidence-based CSE; infertility services; SGBV and coercion; and safe abortion services, this review identified a paucity of cost-effectiveness evidence. With LMICs prioritising interventions for their UHC based on available evidence, including cost-effectiveness data, the negative implications of these evidence gaps can be large, leading to neglect and underfunding and disproportionate consideration given to SRHR areas with a larger evidence base.7 Addressing these gaps will require action between multiple sectors of countries’ governments (e.g. health, education, justice, and finance), development partners, researchers, advocates, and other SRHR stakeholders, and should be a priority for those working to realise comprehensive SRHR in UHC.

The evidence base was stronger for contraceptive methods (n = 27), though only a few publications evaluated individual contraceptive methods specifically, while the majority analysed contraception generally. To respect individuals’ dignity and choice, access to a mix of modern contraceptives is required for countries to reduce unmet need of FP, and further rigorous evaluations are needed for individual modern contraceptives.

Evidence gaps were considerably less pronounced for ANC, childbirth and PNC (n = 67), reproductive cancer (n = 123), and STIs including HIV/AIDS (n = 287). On the one hand, this is likely reflective of the development model that was encoded in the Millennium Development Goal (MDG) agenda, separating maternal health and HIV/AIDS from the comprehensive and transformative understanding of SRHR that came from the ICPD. The shift in discourse, along with the MDGs’ focus on quantifiable outcomes, encouraged vertical approaches to programming with narrower interventions and defined outcomes, which reshaped the funding, policies, and research and knowledge creation and dissemination of the field.22 The efforts made by LMICs to integrate relevant vertical programmes into HBPs when progressively realising UHC will likely necessitate additional cost-effectiveness research based on data collected outside of the context of vertical programmes. Given the disproportionate share of evaluations on HIV/AIDS-only interventions within the STIs including HIV/AIDS component, further CEAs analysing interventions addressing STIs other than HIV are additionally required to ensure that these are adequately represented in UHC HBPs and national health policies. Another striking factor in relation to reproductive cancer was that evaluations focused almost exclusively on cervical cancer prevention and screening and breast cancer treatment strategies; the cost-effectiveness evidence identified for curative and palliative cervical cancer strategies, preventive and diagnostic breast cancer interventions and approaches for all other forms of reproductive cancer was poor, requiring further investigation.

On the other hand, the shift towards, and disproportionate focus on, HIV/AIDS interventions (e.g. ART, PrEP, VMMC and HIV testing), cervical cancer vaccination, and chemotherapy for breast cancer coincide with the “medicalisation of global health”, a growing emphasis on developing and employing healthcare and biomedical and technical solutions for improving health that can be bought, distributed and evaluated quickly.23–25 This detracts attention from the social and political determinants of health which are not well-suited to quantifiable measurement,23–25 SRHR interventions that rely on approaches other than biomedical and technical solutions (e.g. CSE or SGBV), and SRH issues for which low-cost approaches are currently scarcely available in LMICs (e.g. infertility services).1 Additional exploratory research is needed to identify the reasons for the large variations in available cost-effectiveness evidence across SRHR package components. This will also provide further insight into whether both global political targets and the medicalisation of global health have contributed to the direction of the research.

Other noticeable evidence gaps were related to SRHR service delivery modalities alternative to traditional facility-based delivery. For example, only a few economic evaluations have been conducted on integrated SRH services. The SRHR community widely recognises that package components are linked to and interconnected with other components during individuals’ life course as they might need more than one service simultaneously,3 and integration has proven to be gender-responsive, because services are restructured to better meet individuals’ needs;26 there is thus a need for additional evaluations in this regard. Moreover, while COVID-19 has proven to be a massive disrupter of health systems and heavily affected SRHR service delivery, digital innovations such as telehealth services (e.g. virtual consultations and counselling to obtain prescriptions of medical abortion pills) and the use of mHealth initiatives are creating new opportunities for delivering SRH services and rights-based information that could lead to long-needed changes.27,28 While this review includes evaluations published before the COVID-19 pandemic, the few included publications evaluating mHealth interventions reported favourable cost-effectiveness results and more research is needed on innovative service delivery methods.

Lastly, the Guttmacher-Lancet report highlighted adolescents, people with disabilities, adults >50, displaced people, racial and ethnic minorities, and people of diverse sexual orientations, gender identities and expression, and sex characteristics as vulnerable population groups having heightened or neglected SRHR needs.1 Achieving equity in access on the UHC path and ensuring that their rights are protected and fulfilled will require focused efforts to reach these groups, which depends on the availability of data on how to address their SRHR needs. While the analytical framework applied to this scoping review, including the literature search terms (Supplementary Table S2), was intervention-based rather than population-based, it seems nevertheless important to mention that the review identified a scarcity of evaluations targeting most of these groups and a complete lack of evaluations for racial and ethnic minorities, people living with disabilities and adults >50. Regarding internally displaced and refugee populations, only one evaluation assessed the cost-effectiveness of emergency caesarean section as part of humanitarian assistance in a post-conflict setting. Furthermore, interventions targeting people of diverse sexual orientations, gender identities and expression, and sex characteristics were only reported in a few publications evaluating HIV services for key populations, and evaluations addressing SGBV and/or involving a gender-responsive programme component focused on women, girls, and the general heterosexual population. There thus seems to be a paucity of cost-effectiveness evidence at the nexus of interventions addressing SGBV and gender norms and their impact on people in LMICs who fall outside heteronormative relationship structures or gender identification.

Moreover, although adolescence lays the foundation for healthy and fulfilled SRH and lives,1 evaluations of interventions targeting adolescents were almost exclusively confined to preventing HIV and cervical cancer. For SRHR policies to improve the distribution of SRH in the population and promote the equalisation of SRH among individuals, attention needs to be focused on vulnerable and marginalised populations in future SRHR cost-effectiveness research. Since these populations vary based on country, it is critical for future research to be clear in identifying and defining populations, and, depending on data availability, use approaches that account for equity when conducting CEAs. Standard population-based CEA deprioritises interventions which are crucial for addressing the SRH-related needs and rights of vulnerable and marginalised populations who are neglected because of their smaller population. Equity-informative approaches to CEA include extended CEA, targeting specific groups, equity trade-off analysis, or equity impact analysis.29–31 Such approaches give policy- and decision-makers an improved understanding of the equity impacts and trade-offs of different interventions and can help attain specific equity objectives and reduce inequalities in health.30 Within our reviewed publications there were only two that used extended CEA (Supplementary Table S5), highlighting the need for future research to utilise CEA and other equity approaches.

Limitations

Despite attempts to be as systematic and comprehensive as possible in identifying published literature, relevant sources of information may have been omitted; searching other bibliographic databases and including articles in languages other than English may have yielded additional publications, and relevant evaluations might have been missed by not contacting authors of unavailable full texts. The extent to which such additional findings would alter the overall conclusions of this study is unclear. Additionally, although the 67 countries defined as study scope represent 95% of the total population living in LMICs,15 broadening the scope to all LMICs would have likely resulted in additional relevant publications. Moreover, 44 publications reported evaluations falling into multiple components of the SRHR package; instead of counting these for all components involved, these publications could have been tagged against the most relevant component, thus changing the total number of evaluations per component. Lastly, by limiting attention to the essential SRHR interventions included in the Guttmacher-Lancet Commission’s package, we excluded other SRHR interventions that may be both cost-effective and important for individuals’ SRH and wellbeing and the realisation of their rights.

Conclusion

This scoping review is based on the Guttmacher-Lancet Commission's vision for advancing comprehensive SRHR within UHC, building on a definition and a package of essential SRHR interventions to be provided for all people. The available evidence indicates that the majority of SRHR interventions can be delivered cost-effectively in LMICs, thus corroborating the findings of several SRHR stakeholders. However, large variations across regions and countries were visible, and there is limited evidence for the majority of the SRHR package components, important population groups, and innovative service delivery modalities. In support of more conclusive findings and actionable recommendations for SRHR and UHC programme planners and policymakers, it is important to conduct further rigorous economic evaluations to address these evidence gaps, as well as high-quality systematic reviews for the package components for which this scoping review identified a sufficiently large number of evaluations.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

All statements are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the views of the funders, their employers, or affiliated agencies and institutions. All authors had full access to the full data in the study and accept the responsibility to submit for publication.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Data availability statement

The authors confirm that the data supporting the findings of this study are available within the article and its supplementary materials.

References

- 1.Starrs A, Barker G, Basu A, et al. Accelerate progress – sexual and reproductive health and rights for all: report of the Guttmacher– Lancet commission. Lancet. 2018;391:2642–2692. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Every Woman Every Child . The global strategy for women’s, children’s, and adolescents’ health (2016-2030). New York; 2016. https://www.who.int/life-course/partners/global-strategy/ewec-globalstrategyreport-200915.pdf?ua=1.

- 3.UNFPA . Sexual and reproductive health and rights: an essential element of Universal Health Coverage. 2019.

- 4.World Health Organization . Together on the road to universal health coverage. Geneva: A Call to Action; 2017; https://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/handle/10665/258962/WHO-HIS-HGF-17.1-eng.pdf?sequence=1. [Google Scholar]

- 5.World Health Organization . Making fair choices on the path to universal health coverage. Final report of the WHO Consultative Group on Equity and Universal Health Coverage. Geneva; 2014 https://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/handle/10665/112671/9789241507158_eng.pdf?sequence=1.

- 6.World Health Organization . Health financing for universal coverage. Efficiency and universal coverage. 2020.

- 7.Glassman A, Giedion U, Smith P.. What’s in, what’s out: designing benefits for universal health coverage. Washington, DC: Center for Global Development; 2017. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Sen G, Govender V.. Sexual and reproductive health and rights in changing health systems. Glob Public Health. 2015;10:228–242. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Peters M, Godfrey C, McInerney P, et al. Chapter 11: scoping reviews (2020 version). In: Aromataris E, Munn Z, editors. Joanna Briggs Institute reviewer’s manual. JBI; 2020. https://reviewersmanual.joannabriggs.org/ [Google Scholar]

- 10.Arksey H, O’Malley L.. Scoping studies: towards a methodological framework. Int J Soc Res Methodol. 2005;8:19–32. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Khalil H, Peters M, Godfrey CM, et al. An evidence-based approach to scoping reviews. Worldviews Evidence-Based Nurs. 2016;13:118–123. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Tricco A, Lillie E, Zarin W, et al. PRISMA extension for Scoping Reviews (PRISMAScR): checklist and explanation. Ann Intern Med. 2018;169:467–473. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Colquhoun HL, Levac D, O’Brien KK, et al. Scoping reviews: time for clarity in definition, methods, and reporting. J Clin Epidemiol. 2014;67:1291–1294. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.McGowan J, Sampson M, Salzwedel D.. PRESS peer review of electronic search strategies: 2015 guideline statement. J Clin Epidemiol. 2016;75:40–46. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Stenberg K, Hanssen O, Edejer TT-T, et al. Financing transformative health systems towards achievement of the health Sustainable development goals: a model for projected resource needs in 67 low-income and middle-income countries. Lancet Glob Heal. 2017;5:e875–e887. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Drummond M, Sculpher M, Torrance G, et al. Methods for the economic evaluation of health care programmes. 3rd ed. Oxford: Oxford University Press Inc; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Shillcutt SD, Walker DG, Goodman CA, et al. Cost effectiveness in low- and middle-income countries: a review of the debates surrounding decision rules. Pharmacoeconomics. 2009;27:903–917. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Birch S, Gafni A.. Information created to evade reality (ICER): things we should not look to for answers. Pharmacoeconomics. 2006;24:1121–1131. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Evans DB, Lim SS, Adam T, et al. Evaluation of current strategies and future priorities for improving health in developing countries. Br Med J. 2005;331:1457–1461. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Watkins DA, Jamison DT, Mills T, et al. Universal Health Coverage and Essential Packages of Care. In: Jamison DT, Gelband H, Horton S et al., editors. Disease control priorities: improving health and reducing poverty, 3rd ed. Washington (DC): The International Bank for Reconstruction and Development/The World Bank; 2017. [PubMed]

- 21.Husereau D, Drummond M, Petrou S, et al. Consolidated health economic evaluation reporting standards (CHEERS) statement. Br Med J. 2013;346:f1049–f1049. DOI: 10.1136/bmj.f1049 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Yamin AE, Boulanger VM.. Embedding sexual and reproductive health and rights in a transformational development framework: lessons learned from the MDG targets and indicators. Reprod Health Matters. 2013;21:74–85. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Packard RM. A history of global health: interventions into the lives of other peoples. Baltimore (MD: ): Johns Hopkins University Press; 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Clark J. Medicalization of global health 1: has the global health agenda become too medicalized? Glob Health Action. 2014;7:23998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Clark J. Medicalization of global health 4: the universal health coverage campaign and the medicalization of global health. Glob Health Action. 2014;7:24004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Remme M, Siapka M, Vassall A, et al. The cost and cost-effectiveness of gender-responsive interventions for HIV: a systematic review. J Int AIDS Soc. 2014;17:19228. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Church K, Gassner J, Elliott M.. Exporting bad policy: an introduction to the special issue on the GGR’s impact. Sex Reprod Heal Matters. 2020;28:1–4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Cousins S. COVID-19 has “devastating” effect on women and girls. Lancet. 2020;396:301–302. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Verguet S, Kim JJ, Jamison DT.. Extended cost-effectiveness analysis for health policy assessment: A tutorial. Pharmacoeconomics. 2016;34:913–923. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Cookson R, Mirelman AJ, Griffin S, et al. Using cost-effectiveness analysis to address health equity concerns. Value Heal J Int Soc Pharmacoeconomics Outcomes Res. 2017;20:206–212. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Baeten S, Baltussen R, Uyl-de Groot C, et al. Incorporating equity–efficiency interactions in cost-effectiveness analysis – three approaches applied to breast cancer control. Value Heal. 2010;13:573–579. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

The authors confirm that the data supporting the findings of this study are available within the article and its supplementary materials.