Purpose:

This study provides a contemporary assessment of the treatment patterns, health care resource utilization (HRU) and costs among metastatic castration-sensitive prostate cancer (mCSPC) patients in the U.S.

Materials and Methods:

Adults with mCSPC were selected from Optum's de-identified Clinformatics® Data Mart Database (Commercial insurance/Medicare Advantage [COM/MA]; January 1, 2014–July 31, 2019) or Medicare Fee-for-Service (FFS; January 1, 2014–December 31, 2017). The index date was the first metastatic disease diagnosis date on/after the first prostate cancer diagnosis (without prior evidence of castration resistance). Patients were observed for 12 months pre-index (baseline) through their mCSPC period (from index until castration resistance or followup end). First-line (1L) mCSPC therapy was assessed during the mCSPC period; all-cause HRU and health plan-paid costs per-patient-per-year (PPPY) were measured during baseline and mCSPC periods.

Results:

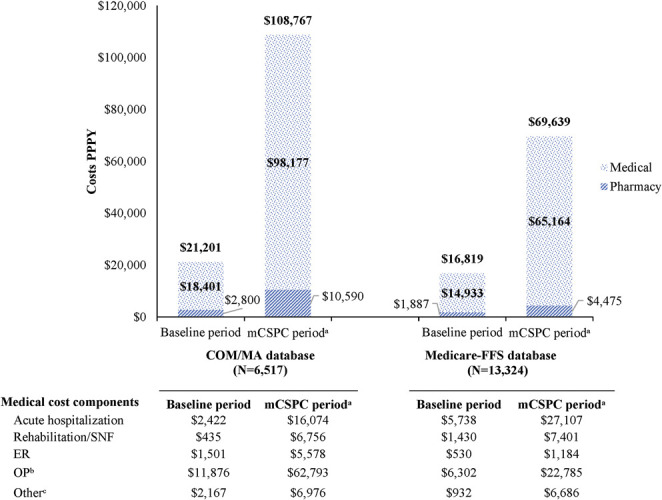

Among 6,517 COM/MA and 13,324 Medicare-FFS mCSPC patients over ∼10 months (median mCSPC period), 38% and 48% remained untreated/deferred treatment, and 45% and 46% received 1L androgen deprivation therapy (ADT) monotherapy, respectively. 1L abiraterone acetate and docetaxel were used among 7% and 6% of COM/MA and 1% and 2% of Medicare-FFS patients, respectively. HRU increased from baseline to mCSPC period, resulting in increased health plan-paid costs from $21,201 to $108,767 in COM/MA and from $16,819 to $69,639 PPPY in Medicare-FFS.

Conclusions:

This study highlights the limited use of newer therapies that improve survival in men with mCSPC in the U.S. HRU and costs increased substantially after onset of metastasis. Given the emergence of newer effective mCSPC therapies, further evaluation of future real-world mCSPC treatment patterns and outcomes is warranted.

Key Words: health care costs; prostatic neoplasms; neoplasm metastasis, castration; procedures and techniques utilization

Abbreviations and Acronyms

- 1L

first-line

- ADT

androgen deprivation therapy

- CCI

Charlson Comorbidity Index

- COM/MA

Commercial insurance/Medicare Advantage

- ER

emergency room

- HRU

health care resource utilization

- mCRPC

metastatic castration-resistant prostate cancer

- mCSPC

metastatic castration-sensitive prostate cancer

- Medicare-FFS

Medicare Fee-for-Service

- NCCN®

National Comprehensive Cancer Network®

- OP

outpatient

- PC

prostate cancer

- PPPY

per-patient-per-year

- SNF

skilled nursing facility

Patients with metastatic prostate cancer are typically initially responsive to surgical or medical (androgen deprivation therapy [ADT]) castration, characterized as metastatic castration-sensitive prostate cancer (mCSPC).1 Patients who develop metastases without being exposed to ADT are also considered as having mCSPC (primary progressive mCSPC).2 Patients who no longer respond to ADT in the mCSPC setting, typically after 18 to 24 months, are diagnosed with metastatic castration-resistant prostate cancer (mCRPC).2,3 Since mCSPC and mCRPC have vastly different prognoses (mCSPC being less advanced than mCRPC), appropriate early intervention is warranted in mCSPC patients to delay disease progression and increase overall survival.2,4–11 Clinical trials have shown that men with mCSPC can achieve a median overall survival of 34-81 months when treated appropriately with ADT with either androgen signaling inhibitors or docetaxel.6,7,9–11

In the last 5 years, randomized placebo-controlled clinical trials of novel agents for mCSPC have demonstrated superior survival benefits when used in combination with ADT versus ADT monotherapy.4–11 Notably, a meta-analysis of clinical trials showed a reduction in risk of death of 37% and 25% with ADT plus abiraterone acetate with prednisone/methylprednisolone and with ADT plus docetaxel versus ADT monotherapy, respectively.12 Similar evidence from more recent trials led to the approvals of apalutamide and enzalutamide for the treatment of mCSPC in 2019.4,5,13,14 Based on these practice-changing findings, the NCCN Clinical Practice Guidelines in Oncology (NCCN Guidelines®) added ADT with abiraterone acetate, docetaxel, apalutamide, or enzalutamide as category 1 (ie based upon high-level evidence, there is uniform National Comprehensive Cancer Network® [NCCN®] consensus that the intervention is appropriate) treatment options for mCSPC, in addition to ADT monotherapy (category 2A, ie based upon lower-level evidence, there is uniform NCCN consensus that the intervention is appropriate).15

In light of these recent additions to the mCSPC treatment options, there is a need to assess how the updated guideline recommendations have translated to real-world clinical practice in the United States. Therefore, the present study aimed to provide a comprehensive and contemporary (until mid-2019) assessment of the real-world treatment patterns, health care resource utilization (HRU), and associated costs of mCSPC patients using large U.S. administrative health claim databases.

Methods

Data Sources

Administrative health claims and laboratory test data from 2 large U.S. databases were used separately to identify insured patients with mCSPC: 1) Optum's de-identified Clinformatics® Data Mart Database (COM/MA; January 1, 2014–July 31, 2019), which include claims from commercial and Medicare Advantage plans for 13 million annual lives across all U.S. census regions; and 2) Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services-sourced Medicare Fee-for-Service (FFS) Research Identifiable Files 100% Sample (January 1, 2014–December 31, 2017), including institutional (Part A), non-institutional (Part B), and drug (Part D) claim types.

For both databases, patient data include demographics, date of death, and claims/costs for medical services and prescription drugs. Laboratory test results are available for ∼10% of patients. All data were de-identified and complied with the patient requirements of the Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act (HIPAA).

Study Design and Population

A retrospective observational cohort study was conducted. The index date was defined as the date of the first medical claim with a diagnosis for metastatic disease on or after the first observed prostate cancer (PC) diagnosis during the study period.

Sample Selection

This study used a comprehensive algorithm to identify patients with mCSPC using claims data and laboratory test results that was previously developed (supplementary information, https://www.jurology.com).16

Observation Period

The baseline period comprised the 12 months pre-index date. The mCSPC period spanned from the index date until the first observed evidence of castration resistance post-index (supplementary information, https://www.jurology.com), or, for mCSPC patients with no observed evidence of castration resistance, the earliest date among death or end of data availability/insurance coverage.

Study Measures and Statistical Analysis

Patient Characteristics

Patient demographics were assessed on the index date. Clinical characteristics included Quan Charlson Comorbidity Index (CCI),17 comorbidities, laboratory tests and results, and imaging tests during baseline, as well as presence of visceral metastases on the index date. Primary progressive mCSPC was defined as the presence of the first PC diagnosis >60 days pre-index date; de novo mCSPC as the first PC diagnosis within 60 days prior to or on the index date. The threshold of 60 days was selected in collaboration with clinical experts and was supported by sensitivity analyses using other periods.

Treatment Patterns

First-line (1L) therapy during the mCSPC period was assessed among COM/MA and Medicare-FFS patients separately. The 1L therapies for mCSPC were determined by review of evidence-based guidelines at the time the study was conducted18 and were further refined based on expert clinical opinion. These included ADT (ie bilateral orchiectomy or ADT medication), first-generation androgen signaling inhibitors, abiraterone acetate, and docetaxel. Apalutamide and enzalutamide were added to evidence-based guidelines as mCSPC treatments after the end of the study period (July 31, 2019) and were not considered as mCSPC therapy in the current study. The supplementary information (https://www.jurology.com) includes additional details regarding the definition of 1L therapy.

The proportion of patients receiving a 1L therapy for mCSPC, time from index date to start of 1L therapy, 1L therapy duration, and the 1L therapy received were reported. The proportion of patients who received ADT only during the entire mCSPC period was also reported. The type of 1L mCSPC therapy received was stratified by year of index date (2015–2017, 2018–2019) for the COM/MA database; data for 2018 onwards were not available in the Medicare-FFS database.

HRU and Health Plan-Paid Costs

All-cause HRU and health plan-paid costs were analyzed during both the baseline and mCSPC periods. HRU and costs were reported per-patient-per-year (PPPY) and included acute hospitalizations, rehabilitation/skilled nursing facility (SNF) stays, emergency room (ER) visits, outpatient (OP) services, other services, and pharmacy claims. Costs were adjusted to 2019 USD using the medical care component of the consumer price index.19

Statistical Analysis

Study measures were described using means, medians, standard deviations (SDs), and interquartile ranges (IQRs) for continuous variables, and frequencies and percentages for categorical variables.

Results

Patient Characteristics

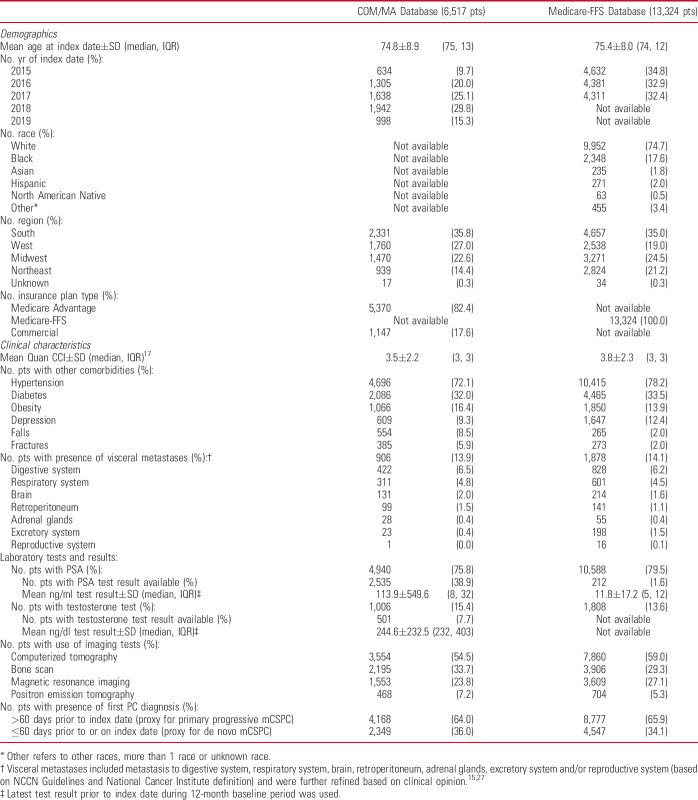

A total of 6,517 COM/MA and 13,324 Medicare-FFS patients with mCSPC were identified (supplementary figure 1, https://www.jurology.com). Mean±SD (median) age was 75±9 (75) years and 75±8 (74) years, respectively (table 1). The mean±SD (median) Quan-CCI was 3.5±2.2 (3) and 3.8±2.3 (3), respectively. The most common comorbidities were hypertension (COM/MA: 72%; Medicare-FFS: 78%) and diabetes (COM/MA: 32%; Medicare-FFS: 34%). Visceral metastases were present in 14% of patients from both databases. Most patients had primary progressive mCSPC (COM/MA: 64%; Medicare-FFS: 66%) vs de novo metastatic disease.

Table 1.

Demographic and clinical characteristics of patients with mCSPC evaluated during the 12-month baseline period

Treatment Patterns

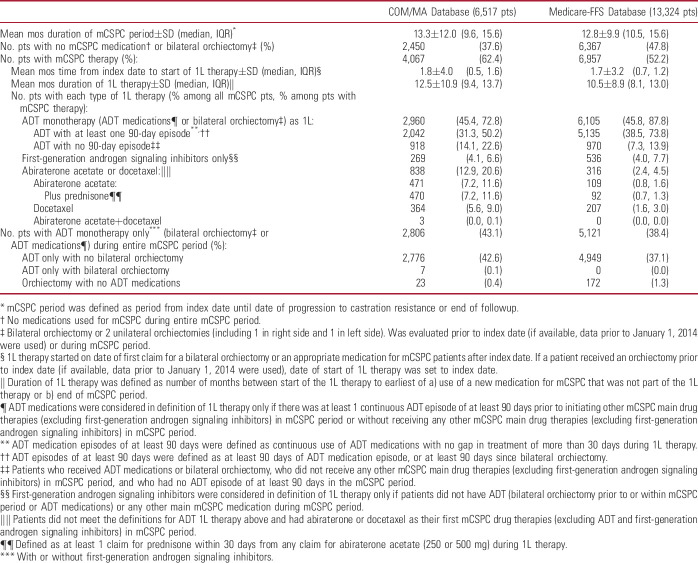

During a median mCSPC period of 9.6 months (COM/MA) and 10.5 months (Medicare-FFS), 62% and 52% of patients received a 1L mCSPC therapy, for a median duration of 9.4 and 8.1 months, respectively (table 2). Among all patients, 38% of COM/MA and 48% of Medicare-FFS patients remained untreated or deferred treatment, while 45% and 46%, respectively, were treated with 1L ADT monotherapy. Abiraterone acetate or docetaxel were used as 1L therapy in 13% (COM/MA) and 2% (Medicare-FFS) of patients. Approximately 43% and 38% of patients, respectively, only received ADT monotherapy (with or without first-generation androgen signaling inhibitors) during the entire mCSPC period despite the availability of other more potent therapies.

Table 2.

Therapy received in patients with mCSPC

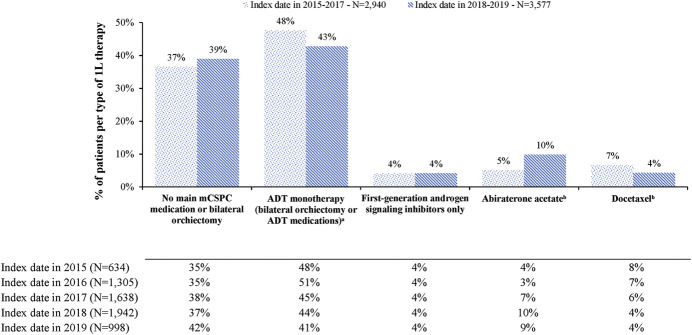

When stratified by year of index date, in the COM/MA database, treatment with 1L ADT monotherapy decreased numerically from 48% to 43% among patients diagnosed with mCSPC in 2015–2017 vs 2018–2019 (fig. 1). While the overall use of abiraterone or docetaxel remained similar in the 2 periods (12%–14%), the use of abiraterone acetate increased among patients diagnosed in 2018–2019 (10%) vs 2015–2017 (5%), whereas the use of docetaxel decreased in 2018–2019 (4%) compared with 2015–2017 (7%).

Figure 1.

1L therapy in patients with mCSPC by year of index date, COM/MA database. a, around 45% (2015–2017) and 41% (2018-2019) of patients received ADT monotherapy only (with or without first-generation androgen signaling inhibitors) during entire mCSPC period. b, with or without ADT. Concomitant use of prednisone or methylprednisolone was not imposed for considering limitations of real-world data.

HRU and Health Plan-Paid Costs

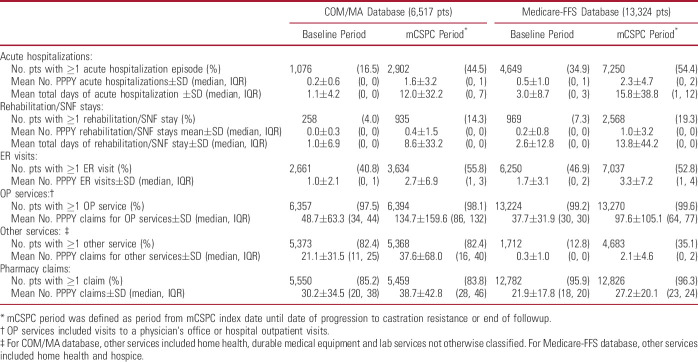

When evaluating the trends in HRU from the baseline to the mCSPC periods, the mean number of days of acute hospitalizations PPPY increased from 1.1 to 12.0 for COM/MA and from 3.0 to 15.8 for Medicare-FFS patients; the mean number of days of rehabilitation/SNF PPPY increased from 1.0 to 8.6 and from 2.6 to 13.8, respectively (table 3). The mean number of ER visits PPPY increased from 1.0 to 2.7 for COM/MA and from 1.7 to 3.3 for Medicare-FFS patients, and the mean number of OP service claims PPPY increased from 48.7 to 134.7 and from 37.7 to 97.6, respectively. The mean number of other service claims PPPY increased from 21.1 to 37.6 and from 0.3 to 2.1, respectively.

Table 3.

All-cause HRU in patients with mCSPC

Accordingly, mean all-cause medical health plan-paid costs PPPY increased from $18,401 in the baseline period to $98,177 in the mCSPC period (COM/MA) and from $14,933 to $65,164 (Medicare-FFS), mainly driven by an increase in OP costs from $11,876 to $62,793 and from $6,302 to $22,785, respectively, as well as an increase in acute hospitalization costs from $2,422 to $16,074 and from $5,738 to $27,107, respectively (fig. 2). Mean health plan-paid pharmacy costs PPPY increased from $2,800 in the baseline period to $10,590 in the mCSPC period (COM/MA) and from $1,887 to $4,475 (Medicare-FFS), leading to an increase in total all-cause health plan-paid costs PPPY from $21,201 in the baseline period to $108,767 in the mCSPC period for COM/MA patients and from $16,819 to $69,639, respectively in Medicare-FFS patients.

Figure 2.

Mean all-cause health plan-paid costs in 2019 U.S. dollars (USD) in patients with mCSPC (PPPY). a, mCSPC period was defined as period from index date until date of progression to castration resistance or end of followup. b, OP service was defined as either visit to physician's office or hospital outpatient visit. c, for COM/MA database, other services included home health, durable medical equipment and lab services not otherwise classified. For Medicare-FFS database, other services included home health and hospice.

Discussion

Using the largest retrospective cohort of men with mCSPC studied to date, this analysis of current treatment patterns of commercially insured, Medicare Advantage, and Medicare-FFS patients in the U.S. demonstrates that 38%–48% of men with mCSPC remained untreated or deferred treatment, 45%–46% of them received only ADT monotherapy as their 1L treatment, and 38%–43% only received ADT monotherapy during the entire mCSPC period. These findings are noteworthy given demonstrated superior efficacy of abiraterone acetate and docetaxel compared to ADT monotherapy (hazard ratios for death of 0.61–0.78)6–11 and inclusion of ADT with abiraterone acetate plus prednisone or ADT with docetaxel as category 1 treatment options preferred over ADT monotherapy as a category 2A treatment for mCSPC in the NCCN Guidelines.18 This underutilization of abiraterone and docetaxel occurred during a time when evidence supporting their use was strong, albeit largely limited to high-volume or high-risk patients,6,7,10 with the exception of 1 trial outside of the U.S.8,9 Moreover, the studies supporting the use of abiraterone were not published until July 2017,6,8 near the end of the study period for the Medicare-FFS database. Nonetheless, the continued underutilization of these agents even in the more recent time period in the COM/MA database highlights a mismatch between guideline recommendations and real-world practice. Although additional data (not shown here) revealed that ∼13%–16% of patients had only lymph node metastases at diagnosis (∼15%–18% among those who received ADT monotherapy), and that mean age and Quan CCI were slightly higher among COM/MA patients with treatment deferral/ADT monotherapy (∼1 year older than the overall population), potentially suggesting that they may be less fit for intensive treatment, these factors cannot completely explain the underutilization of abiraterone and docetaxel. In addition, similar findings were seen in a recent study of Medicare patients (2009–2018) with mCSPC, where 1L docetaxel was only used by 4.8% of treated patients and novel agents (abiraterone acetate, apalutamide, enzalutamide) by 4.5%.20 A prior study also assessed real-world mCSPC treatment patterns using commercial claims (2000–2013; ie before the introduction of abiraterone acetate and docetaxel for mCSPC) and reported consistent findings: 51% received guideline-recommended medical or surgical castration, and 31% received no castration or drug therapy, including corticosteroids, over a mean followup of ∼3 years.21

The current study revealed that a slight decrease in the use of 1L ADT monotherapy from 2015–2017 to 2018–2019 was offset by an increase in the use of abiraterone acetate. However, despite receiving U.S. Food and Drug Administration approval for mCSPC in February 2018,22 abiraterone acetate was used in only 10% of mCSPC patients in 2018–2019. In addition, while the use of docetaxel with ADT has been a standard of care for mCSPC since 2015,23 its use was observed in only 7% of patients in 2015–2017 and in even fewer patients (4%) in 2018–2019. Nevertheless, the overall use of abiraterone or docetaxel remained similar in the 2 periods. Whether the approval of the newer agents apalutamide and enzalutamide4,5 leads to changes in the management of mCSPC in the future remains to be determined.

In addition to treatment patterns, this study provides a comprehensive overview of the economic burden of mCSPC. All-cause HRU substantially increased with the onset of metastasis, leading to 4–5 times higher associated health plan-paid costs in the mCSPC period vs the baseline period. Further research is warranted to determine if the lack of exposure to more effective treatments contributed to the high HRU and medical costs observed. Although HRU and health care costs post-progression to mCRPC were not assessed in this study, 2 recent claims-based studies estimated a total cost of care ranging from $139,847–$182,156 PPPY among commercially insured (with Medicare Supplemental) patients with mCRPC.24,25 This is substantially higher than the $108,767 (COM/MA) and $69,639 (Medicare-FFS) of total health care costs observed in mCSPC patients in the current study. The impact of earlier treatment of mCSPC beyond ADT monotherapy on clinical and economic outcomes warrants further evaluation.

The results obtained in this study were consistent across the 2 databases and any differences observed may be due to variation in coverage policy, length of patient continuous enrollment, and study period.

As with all claims-based studies, coding inaccuracies may have led to case misidentification since analyses of claims data depend on correct diagnosis, procedure, and drug codes. For example, some patients may have been misclassified as untreated if orchiectomy was conducted before the beginning of the data stream; as orchiectomy is an uncommon form of ADT, the number of men affected by this is likely small. In addition, prescription claims do not necessarily indicate that the dispensed medication was taken as prescribed; therefore, reported treatment utilization may have been overestimated. Reasons for treatment discontinuation were also not available. The study period also predated the U.S. Food and Drug Administration approvals and inclusion of apalutamide and enzalutamide for mCSPC in the NCCN Guidelines.15,18 Lastly, the study included patients with Medicare-FFS, Medicare Advantage, and commercial insurance coverage, who may not be representative of the general U.S. population or patients without health insurance (with potentially worse outcomes and/or important unmet needs).26 Nonetheless, administrative claims data remain a valuable source of information, as they comprise a valid and large data pool and have the advantage of reflecting patient management in the real-world setting.

Conclusion

The findings of this retrospective U.S. real-world study highlight that the vast majority of mCSPC patients are not receiving agents that have recently shown superior treatment outcomes compared to ADT monotherapy. Despite level 1 evidence and updated NCCN recommendations,18 adoption of more efficacious therapies like abiraterone acetate and docetaxel remained low in this patient population. The substantial clinical and economic burden in patients with mCSPC highlights the importance of earlier and more effective treatment, although the impact of increased use of agents known to reduce progression on real-world clinical and economic outcomes has not been assessed. Given more recent data and an expanding pool of agents that improve outcomes relative to ADT monotherapy, whether treatment patterns change in the future requires further study.

Acknowledgments

Medical writing support was provided by a professional medical writer, Christine Tam, an employee of Analysis Group, Inc.

Footnotes

Declaration of funding: Financial support for this research was provided by Janssen Scientific Affairs, LLC. The study sponsor was involved in several aspects of the research, including the design and conduct of the study; collection, management, analysis and interpretation of the data; preparation, review and approval of the manuscript; and decision to submit the manuscript for publication.

Conflicts of interest: SJF and CJR have received consulting fees from Janssen Scientific Affairs, LLC. SJF is also a consultant to Astellas, Pfizer, Bayer, Sanofi, Myovant, Merck and AstraZeneca. DMD is an employee of Janssen Scientific Affairs, LLC and stockholder of Johnson & Johnson. XK was an employee of Janssen Scientific Affairs, LLC and stockholder of Johnson & Johnson when the study was conducted and the manuscript was developed. MHL, HR, FK and PL are employees of Analysis Group, Inc., a consulting company that has provided paid consulting services to Janssen Scientific Affairs, LLC. PF is an employee of Janssen Pharmaceuticals, Inc. and stockholder of Johnson & Johnson. AP, ZP and SK are employees of Avalere Health, a consulting company that has provided paid consulting services to Janssen Scientific Affairs, LLC.

Author contributions: SJF, XK, PF, DMD and CJR contributed to study conception and design, and data analysis and interpretation. CJR had full access to all the data in the study and takes responsibility for the integrity of the data and the accuracy of the data analysis. MHL, HR, FK and PL contributed to study conception and design, collection and assembly of data, and data analysis and interpretation. AP, ZP and SK contributed to study conception and design, collection and assembly of data, and data analysis and interpretation. All authors reviewed and approved the final content of this manuscript.

Institutional review board statement: All data were de-identified and complied with the patient requirements of the Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act (HIPAA). Therefore, review by an institutional review board was not required.

Informed consent statement: Patient consent was not required since all data were de-identified.

Previous presentation: Part of the material based on the COM/MA database in this manuscript was presented at the Academy of Managed Care Pharmacy (AMCP) Nexus 2019 held from October 29 to November 1, 2019 in National Harbor, Maryland and the American Society of Clinical Oncology (ASCO) Annual Meeting held virtually from May 29 to 31, 2020.

Contributor Information

Charles J. Ryan, Email: ryanc@umn.edu.

Xuehua Ke, Email: kexuehua@hotmail.com.

Hela Romdhani, Email: Hela.Romdhani@analysisgroup.com.

Frederic Kinkead, Email: Frederic.Kinkead@analysisgroup.com.

Patrick Lefebvre, Email: Patrick.Lefebvre@analysisgroup.com.

Allison Petrilla, Email: apetrilla@avalere.com.

Zul Pulungan, Email: zPulungan@avalere.com.

Seung Kim, Email: SKim@avalere.com.

Denise M. D'Andrea, Email: ddandre@its.jnj.com.

Peter Francis, Email: pfranci6@its.jnj.com.

Stephen J. Freedland, Email: Stephen.Freedland@cshs.org.

References

- 1.Cattrini C, Castro E, Lozano R, et al. : Current treatment options for metastatic hormone-sensitive prostate cancer. Cancers (Basel) 2019; 11: 1355. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Teo MY Rathkopf DE and Kantoff P: Treatment of advanced prostate cancer. Annu Rev Med 2019; 70: 479. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Rajaram P, Rivera A, Muthima K, et al. : Second-generation androgen receptor antagonists as hormonal therapeutics for three forms of prostate cancer. Molecules 2020; 25: 2448. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Armstrong AJ, Szmulewitz RZ, Petrylak DP, et al. : ARCHES: a randomized, phase III study of androgen deprivation therapy with enzalutamide or placebo in men with metastatic hormone-sensitive prostate cancer. J Clin Oncol 2019; 37: 2974. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Chi KN, Agarwal N, Bjartell A, et al. : Apalutamide for metastatic, castration-sensitive prostate cancer. N Engl J Med 2019; 381: 13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Fizazi K, Tran N, Fein L, et al. : Abiraterone plus prednisone in metastatic, castration-sensitive prostate cancer. N Engl J Med 2017; 377: 352. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Fizazi K, Tran N, Fein L, et al. : Abiraterone acetate plus prednisone in patients with newly diagnosed high-risk metastatic castration-sensitive prostate cancer (LATITUDE): final overall survival analysis of a randomised, double-blind, phase 3 trial. Lancet Oncol 2019; 20: 686. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.James ND, de Bono JS, Spears MR, et al. : Abiraterone for prostate cancer not previously treated with hormone therapy. N Engl J Med 2017; 377: 338. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.James ND, Sydes MR, Clarke NW, et al. : Addition of docetaxel, zoledronic acid, or both to first-line long-term hormone therapy in prostate cancer (STAMPEDE): survival results from an adaptive, multiarm, multistage, platform randomised controlled trial. Lancet 2016; 387: 1163. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kyriakopoulos CE, Chen YH, Carducci MA, et al. : Chemohormonal therapy in metastatic hormone-sensitive prostate cancer: long-term survival analysis of the randomized phase III E3805 CHAARTED trial. J Clin Oncol 2018; 36: 1080. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Sweeney CJ, Chen YH, Carducci M, et al. : Chemohormonal therapy in metastatic hormone-sensitive prostate cancer. N Engl J Med 2015; 373: 737. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Wallis CJD, Klaassen Z, Bhindi B, et al. : Comparison of abiraterone acetate and docetaxel with androgen deprivation therapy in high-risk and metastatic hormone-naive prostate cancer: a systematic review and Network meta-analysis. Eur Urol 2018; 73: 834. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA): FDA approves enzalutamide for metastatic castration-sensitive prostate cancer. U.S. Food and Drug Administration 2019. Available at https://www.fda.gov/drugs/resources-information-approved-drugs/fda-approves-enzalutamide-metastatic-castration-sensitive-prostate-cancer. Accessed July 31, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- 14.U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA): FDA approves apalutamide for metastatic castration-sensitive prostate cancer. U.S. Food and Drug Administration 2019. Available at https://www.fda.gov/drugs/resources-information-approved-drugs/fda-approves-apalutamide-metastatic-castration-sensitive-prostate-cancer. Accessed November 23, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- 15.National Comprehensive Cancer Network® (NCCN®): NCCN Clinical Practice Guidelines in Oncology—Prostate Cancer; National Comprehensive Cancer Network 2020. Referenced with permission from the NCCN clinical practice guidelines in Oncology (NCCN Guidelines®) for prostate cancer V.3.2020. © National comprehensive cancer Network, Inc. 2020. All rights reserved. Accessed November 23, 2020. To view the most recent and complete version of the guideline, go online to NCCN.org. NCCN makes no warranties of any kind whatsoever regarding their content, use or application and disclaims any responsibility for their application or use in any way. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Freedland S, Ke X, Lafeuille M, et al. : Identification of patients with metastatic castration-sensitive or metastatic castration-resistant prostate cancer using administrative health claims and laboratory data. Curr Med Res Opin 2021; 37: 609. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Quan H, Sundararajan V, Halfon P, et al. : Coding algorithms for defining comorbidities in ICD-9-CM and ICD-10 administrative data. Med Care 2005; 43: 1130. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.National Comprehensive Cancer Network® (NCCN®). NCCN Clinical Practice Guidelines in Oncology—Prostate Cancer. Referenced with permission from the NCCN Clinical Practice Guidelines in Oncology (NCCN Guidelines®) for Prostate Cancer V.2.2019; 2019. © National comprehensive cancer Network, Inc. 2020. All rights reserved. Accessed November 5, 2020. To view the most recent and complete version of the guideline, go online to NCCN.org. NCCN makes no warranties of any kind whatsoever regarding their content, use or application and disclaims any responsibility for their application or use in any way. [Google Scholar]

- 19.U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics: Measuring Price Change in the CPI: Medical Care. U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics 2019. Available at https://www.bls.gov/cpi/factsheets/medical-care.htm. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Freedland S, Agarwal N, Ramaswamy K, et al. : Real-world utilization of advanced therapies and racial disparity among patients with metastatic castration-sensitive prostate cancer (mCSPC): a Medicare database analysis. J Clin Oncol, suppl., 2021; 39: 5073. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Flaig TW, Potluri RC, Ng Y, et al. : Disease and treatment characteristics of men diagnosed with metastatic hormone-sensitive prostate cancer in real life: analysis from a commercial claims database. Clin Genitourin Cancer 2017; 15: 273.e271. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA): FDA approves abiraterone acetate in combination with prednisone for high-risk metastatic castration-sensitive prostate cancer. U.S. Food and Drug Administration 2018. Available at https://www.fda.gov/drugs/resources-information-approved-drugs/fda-approves-abiraterone-acetate-combination-prednisone-high-risk-metastatic-castration-sensitive#:∼:text=On%20February%207%2C%202018%2C%20the,sensitive%20prostate%20cancer%20(CSPC). Accessed July 29, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Belderbos BPS, de Wit R, Lolkema MPJ, et al. : Novel treatment options in the management of metastatic castration-naive prostate cancer; which treatment modality to choose? Ann Oncol 2019; 30: 1591. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Appukkuttan S, Tangirala K, Babajanyan S, et al. : A retrospective claims analysis of advanced prostate cancer costs and resource use. Pharmacoecon Open 2020; 4: 439. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Wu B, Li SS, Song J, et al. : Total cost of care for castration-resistant prostate cancer in a commercially insured population and a Medicare supplemental insured population. J Med Econ 2020; 23: 54. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Mahal BA, Aizer AA, Ziehr DR, et al. : The association between insurance status and prostate cancer outcomes: implications for the Affordable Care Act. Prostate Cancer Prostatic Dis 2014; 17: 273. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.National Cancer Institute (NCI): Visceral. National Cancer Insitute 2020. Available at https://www.cancer.gov/publications/dictionaries/cancer-terms/def/visceral. Accessed August 27, 2020. [Google Scholar]